Sparta Praha are the current champions of the Czech First League after manager Brian Priske delivered success in his first season with the club, giving them the first league title since 2014. In his second season in charge, Sparta are just one point behind Slavia Praha, and are in a third consecutive cup final. Their recent success even stems from Europe, where they dropped out of the UEFA Europa League at the round of 16 stages to favour Liverpool.

Sparta Praha have scored 14 goals from set pieces this season so far, and have clearly shown signs of a team who pays attention to the set play preparation with their corner routines. However, although they have scored many set plays, their dominance suggests they could be performing to an even higher standard. From 225 corner kicks, only 3% have resulted in goals, indicating that there is room for improvement in one aspect or another.

In this tactical analysis, we will examine the tactics behind Sparta Praha’s corner kicks, with an in-depth analysis of how they have used screens to be dangerous from corners. This set-piece analysis will also examine the details behind why their structure has allowed them to sustain pressure from corner kicks and the potential areas for improvement to increase their 3% conversion rate.

Attacking Structure

One thing that immediately stands out when you lay your eyes on Sparta Praha’s set plays is their dominance in the penalty area after the initial duel. Loose balls and the second phase of corners are eaten up by Sparta, allowing them to sustain pressure on their opponents through long-range shots and crosses back into the penalty area while the defensive side is still recovering from the initial delivery.

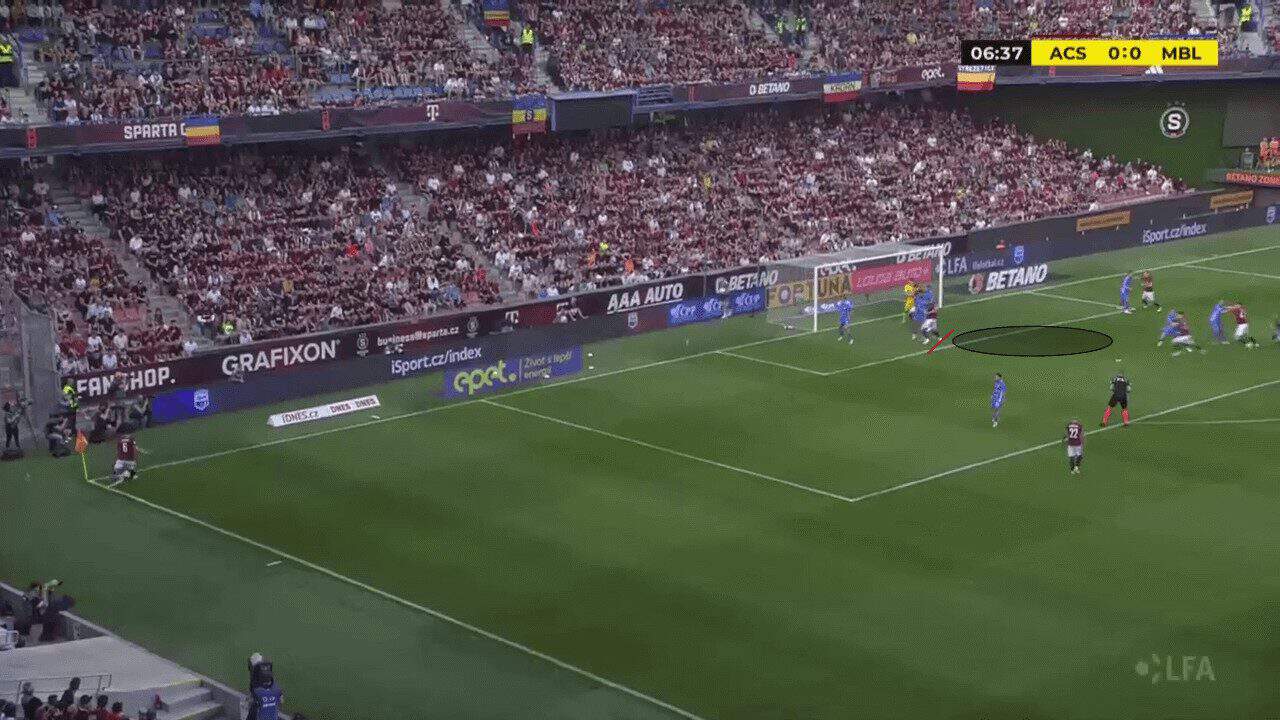

This is only possible because of Sparta’s bravery and ambition in their high and aggressive starting positions of the entire outfield unit. In recent games, the setup has looked like in the example below. Two players attempt to create space around the six-yard line, whilst two attackers attempt to arrive in the space created. We then see one attacker arriving at the back post, which enables him to attack rebounds/flicks whilst also being to able to revive attacks if the cross is overhit by heading the ball back across. One attacker is used to prevent the goalkeeper from claiming the ball, while there are three players located around the box.

We will go into more depth on this later, but Sparta’s chances come during the second phase rather than from the work that is done around the penalty spot. With one player blocking the goalie, one on the far side of the penalty area, and three players around the box, Sparta have five players encompassing the defending side, whose primary responsibility is to keep the ball alive rather than attacking the ball and scoring.

The goalkeeper being blocked means that there is little threat of the opposition initiating quick counter-attacks, which allows them to throw all 10 outfield players within 25 yards of the goal. One other common way in which teams are able to start counter-attacks is through a volleyed clearance at the near post, but with the Czech champions opting for more floated crossing techniques, the likelihood of a cross being severely underhit is minimised. As a result, there is no direct threat of a counter being sprung.

With that in mind, Sparta are able to use six players to attack the penalty area, which gives them the chance to have real estate in many different parts of the penalty area. Consequently, there is a high chance that no matter where a loose ball lands after the initial aerial duel, it will likely be in close proximity to a Sparta attacker, who is able to keep the attack alive and help sustain pressure on the opposition.

Using Screens to Create Space for Crosses

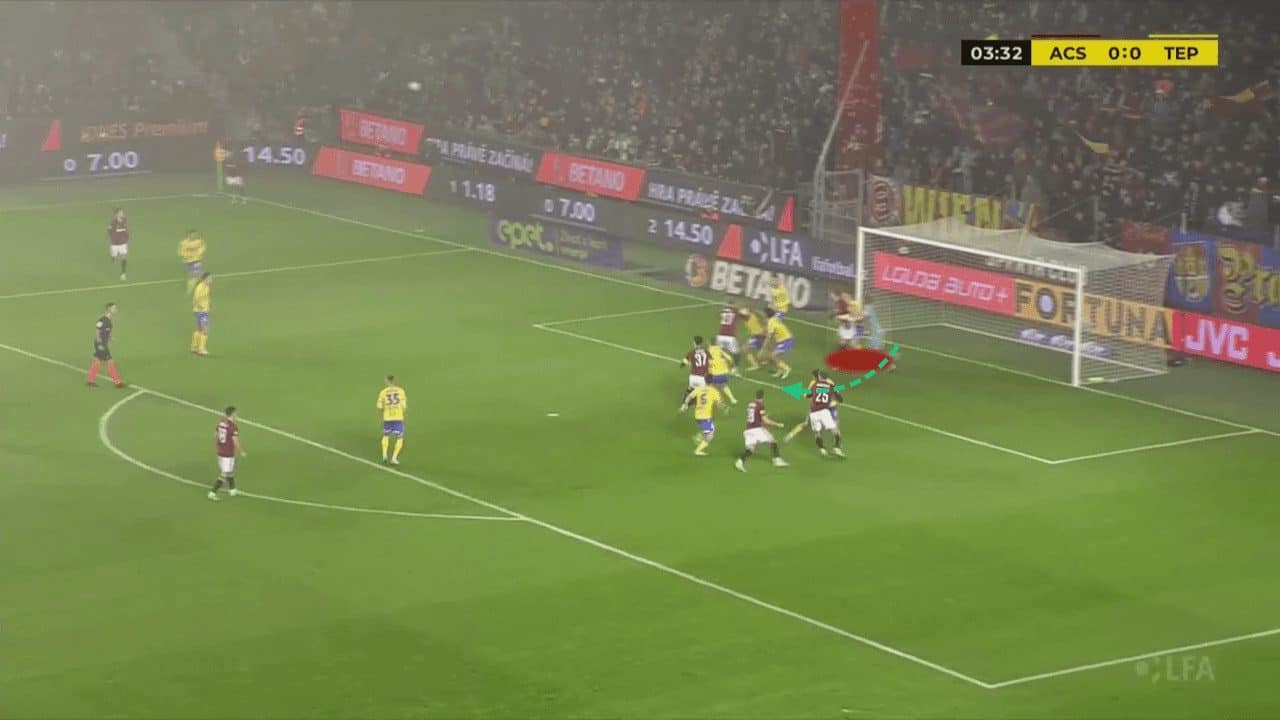

As mentioned earlier, the direct success which has been achieved by Sparta, has come from their ability to immobilise zonal defenders, allowing the ball easy access to the six-yard line. The image below shows how a screen on the zonal defender means that the six-yard box is left open, where all that is left is for an attacker from deep to arrive in the space to receive the golden opportunity. With the deep attackers having so much space to attack and the advantage of their body facing the goal, at least one attacker should be able to take advantage of the space, although this has not always been the case.

One alternate method that Sparta have used to create the space around the six-yard box, has been through the use of a decoy corner taker. In the image below, an inswinging and outswinging delivery is possible before the corner is taken, with two players lining up to take it. The opposition zonal unit must drop deeper to prevent the inswinger from being able to exploit the space, which is usually left open when facing an outswinging delivery. As they drop deep, it creates space around the near side of the six-yard box, which would usually have been protected by zonal defenders, and so through the simple addition of a decoy, space further from the goal is more easily accessible.

One issue that has come up when watching Sparta Praha’s corners has been the unnecessary usage of blocks on goalkeepers when the delivery is aimed towards the near edge of the six-yard box. The setup of a corner kick should always depend on the available space that is going to be targeted. When the delivery is going to be flatter and towards someone closer to the ball than the front post is, it is highly unlikely that the goalkeeper will have the time and opportunity to step out and claim the cross. This could suggest a lack of clarity within the squad about which routine is used and where the ball is headed.

The block on the goalkeeper probably doesn’t change his or anyone’s approach, making it almost irrelevant. The only benefit is the ability of the attacker to block the goalkeeper’s view and be closer to the goal for loose balls and rebounds. However, suppose the highlighted defender steps up after the cross. In that case, the attacker will be left offside, meaning his role has no value, and that body could be used anywhere else to cause problems for other defenders.

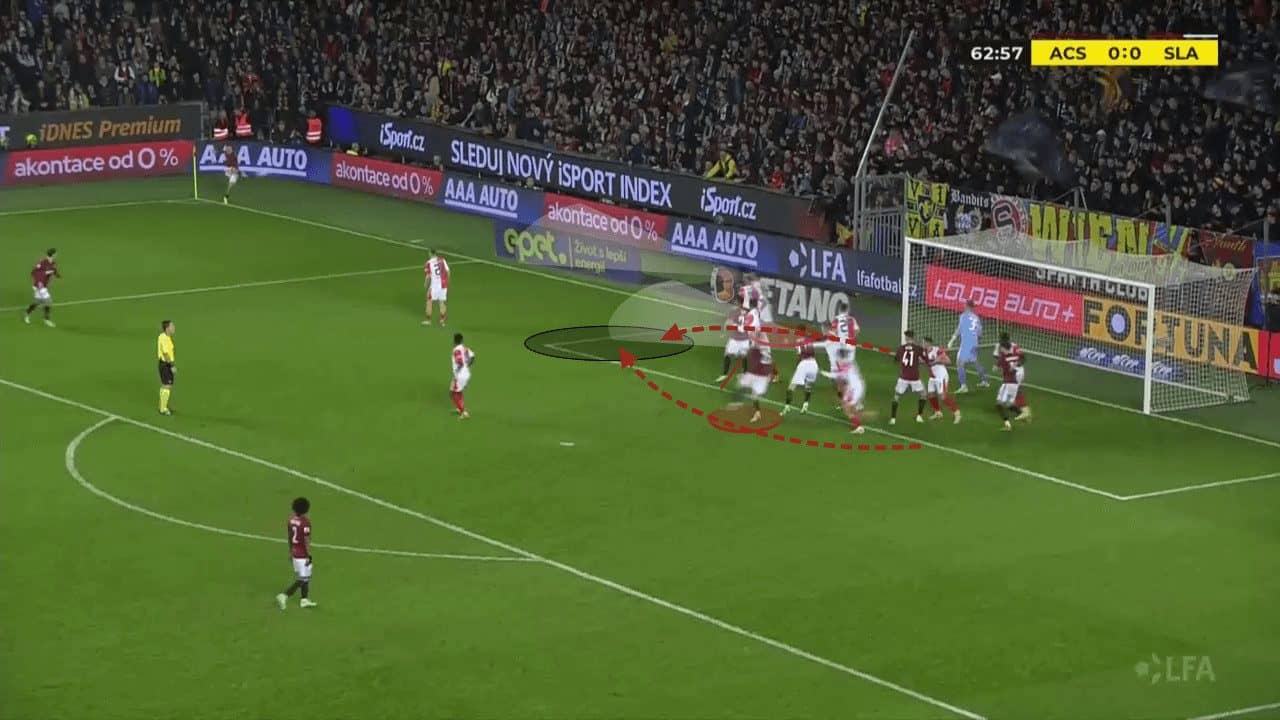

One other issue has been through the early and predictable attempts to set screens on the goalkeeper. As opposition sides come to expect this action to occur, defenders can spot the attempts earlier and put out fires quicker. In the example below, the defender has enough time between the screen being set and the ball being delivered to shift the opponent out of the goalkeeper’s path, allowing him to easily claim the ball.

In the Premier League, Arsenal have consistently used Ben White to set screens on goalkeepers to deliver the ball into the six-yard box like Sparta aim to do. However, once the screen began to become predictable, White made sure to change his movements prior to the corner being taken in order to be able to block the keeper as the cross comes in. Just like players attempt to do around the penalty spot when attacking corners, the player blocking the keeper needs to create the separation in order to be able to effectively set the screen. This could be possible by starting in the goalkeeper’s blindside, where he can arrive setting the screen just as the cross is taken, not giving the defender any time to shift him out of the way.

Struggles With Creating Separation Consistently

The consistent theme in this article has been around the issues with separation. Sparta Praha consistently provide the ball easy access into high-value areas through setting screens on zonal defenders, but they have failed to provide their players with the same luxuries. This means that when there is a space that can be attacked, the attacking players are unable to lose their markers and have to compete in 50/50 aerial duels. Of course, this depends on the individual’s aerial prowess, and in a couple of instances has led to goals, but if this problem could be fixed, Sparta’s efficiency from corners could skyrocket.

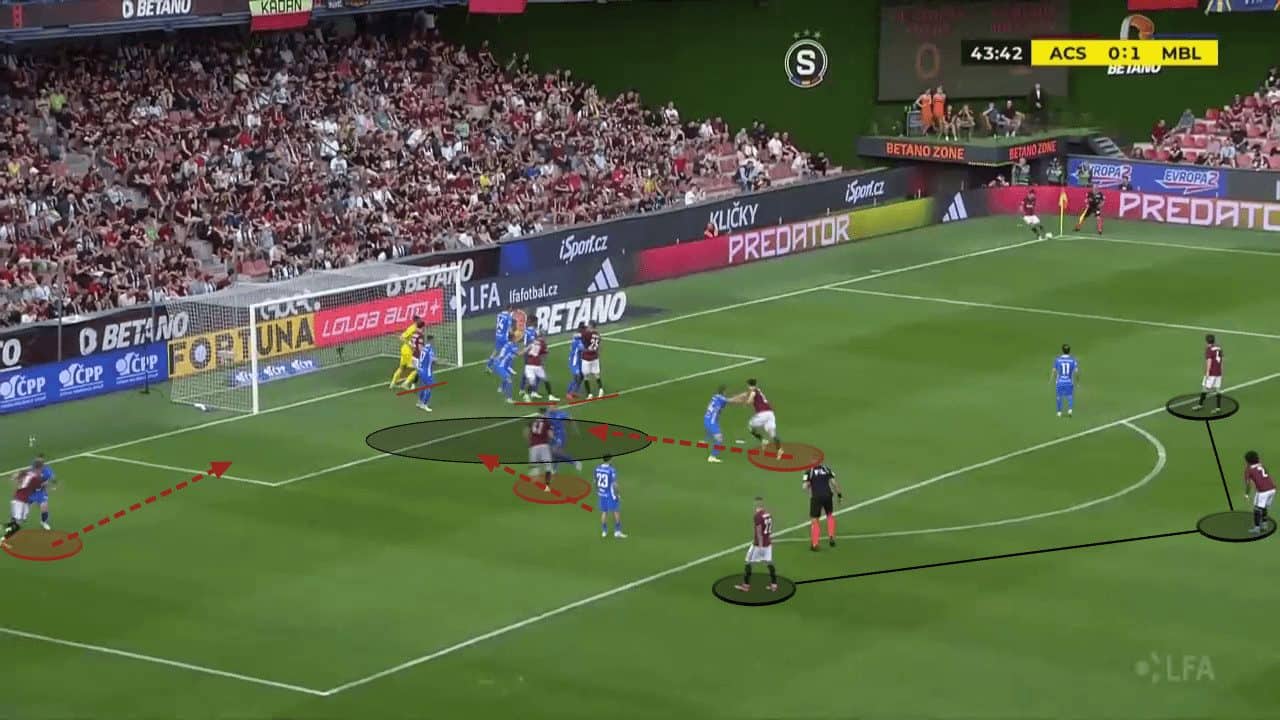

In the image below, we can see five attackers, all with individual 1v1 battles. In each instance, the defender is already in close proximity, meaning that they can get physical to prevent attackers from building up any momentum. Attackers have no advantages with their speed and have to rely on their sharp movements to create separation from their markers, which is tough to do when the box is so congested, and attackers might unintentionally be blocking each other’s paths to the goal.

One way in which attackers can gain the advantage in 1v1 duels is by using a deeper starting position. When the ball is going straight to a defender who is static, attackers moving from a deeper position are able to use the momentum they’ve created to generate additional power in the jump for the header, giving them the advantage in the aerial duel. On the odd occasion, this has happened for Sparta and been successful, highlighting the need for this move to be added to their set-piece tool kit.

While the vertical runs have been easier to track for defending players, Sparta have been able to create separation through horizontal movements made across the six-yard box. The simple tweak of moving players into the defender’s blindside has been effective in giving individual attackers the separation they need to arrive in space unmarked.

Timing issues have been consistently inconsistent throughout the season. In the instances where goals were scored, it is clear to see the attacker arriving in space at the same time as the ball does. However, in a lot of corner kicks, the runs were made too early, leading to situations like the one pictured below. The attackers would arrive in the box while the ball was still coming, which meant they had to backtrack in order to make contact with the ball, as their momentum carried them past where the ball was going. Ideally, the attacker arrives in space at a quick pace, which enables him to generate more power on the headed effort. However, when that run is mistimed, the players are forced to backtrack, and the headed effort of a player who is reversing, moving away from the goal, is much weaker than if the player was moving towards the goal.

Summary

This tactical analysis has detailed the positive aspects of Sparta Praha’s set play design and highlighted some areas that could be improved. Their use of screens has carved open big gaps in the opposition’s defences, and they have been able to control the second phase of most corner kicks.

However, the infrequent ability to create separation for attackers arriving in space has meant that players are always focused on battling defenders to make the first contact rather than being able to focus on the execution of their headed efforts. The issues with timings have also meant that attackers rarely are able to attack the ball with speed, meaning that many attacking efforts aren’t as threatening as they could potentially have been.

These slight improvements to Sparta Praha’s corner kick routines could be the difference between retaining the league title or just missing out, as Sparta trail rivals Slavia Praha by a single point, going into the final stretch of the season.

Comments