Strasbourg have enjoyed a positive season so far in Ligue 1 under Julien Stéphan, who replaced Thierry Laurey as the club’s manager back in May. Following his March departure from Rennes, a club he’d guided to the UEFA Champions League with a third-place finish in 2019/20 — a stint during which he managed the likes of teenaged Eduardo Camavinga, who’s since joined Real Madrid, and emerging Brazil star Raphinha, who’s since become EPL side Leeds United’s key man, Stéphan was linked with plenty of jobs including the at-the-time-vacant Celtic position. However, we’ve since seen the promising 41-year-old remain in France, joining Les Courers.

I previewed Stéphan at Strasbourg for Total Football Analysis back in July, when I analysed what Strasbourg fans could expect from their new coach. While some of my theorisations have not materialised (I imagined that Stéphan’s Strasbourg side would not play so many long balls, for example, though I did state he likes to give his side the option of doing so and Ludovic Ajorque would likely be a good option for this, which has definitely been the case but to a greater extent than I’d anticipated, admittedly), some of it has proven accurate, including the three-centre-back system that creates a 3-1 / 3-2 shape in build-up, the recruitment of new centre-backs, who turned out to be Gerzino Nyamsi from Rennes and Lucas Perrin from Marseille, and the increased importance of Sanjin Prcić who can play the holding midfield role well for Stéphan and play lots of switches — an important element of the 41-year-old’s strategy and tactics. For an even more complete analysis of Stéphan at Strasbourg, I do think it’d be worth recapping that analysis from July, if possible, before moving on to this one as it could paint an even clearer picture of Stéphan and this Strasbourg side.

The ex-Rennes man’s time at Strasbourg has been positive because although Strasbourg have finished in the bottom half of the table in each of the last four seasons since earning promotion from Ligue 2 in 2016/17 (15th — 2017/18, 11th — 2018/19, 11th — 2019/20, 15th — 2020/21), they currently occupy a far more impressive sixth place position on the table — a spot that has them contending for European qualification. This would be a great achievement for a side that was playing in France’s third tier, Championnat National 1, in 2015/16.

Additionally, “on fire” Strasbourg are currently Ligue 1’s second-highest scoring side, trailing just PSG, with 34 goals from their 17 games so far this term. This is two more goals than they managed to score two seasons ago despite having played 10 fewer games, while this is also just 15 fewer goals than they managed to score from 21 more games last term, so the starkest difference in Strasbourg’s performances between this season and previous ones, for me, is their increased potency in front of goal.

So, how have Stéphan and Strasbourg achieved this attacking improvement? This tactical analysis will be a team scout report with a specific focus on Strasbourg’s attack, aiming to highlight how Stéphan’s time at Stade de la Meinau has played out thus far, in terms of the implementation of his tactical ideas. I hope to show how the key elements of this team’s strategy and tactics, as well as explain why these tactical elements are prominent for Les Courers. The stats and data in this analysis are collected from Wyscout unless stated otherwise.

Build-up and ball progression

As mentioned at the beginning of this tactical analysis, switching play is a key part of Strasbourg’s strategy and tactics under Stéphan and I’ll go on to discuss that and explain why this is the case later in this piece. However, I’ll begin by looking at Strasbourg’s build-up play, to look at how this team begins their attacks and explain what about their build-up is most significant to their impressive attack.

Strasbourg have played the 13th-most passes of the 20 Ligue 1 sides this season (385.88 per 90), but they’ve played the sixth-most progressive passes (65.65 per 90) with a ‘progressive pass’ defined by Wyscout as a pass where: ‘the distance between the starting point and the next touch is: 1. at least 30 meters closer to the opponent’s goal if the starting and finishing points are within a team’s own half 2. at least 15 meters closer to the opponent’s goal if the starting and finishing points are in different halves or 3. at least 10 meters closer to the opponent’s goal if the starting and finishing points are in the opponent’s half. Strasbourg’s structure in build-up and tendencies both on and off the ball during this phase help them to create so many progressive pass attempts, move upfield and ultimately get into goalscoring positions more regularly than they would otherwise be able to.

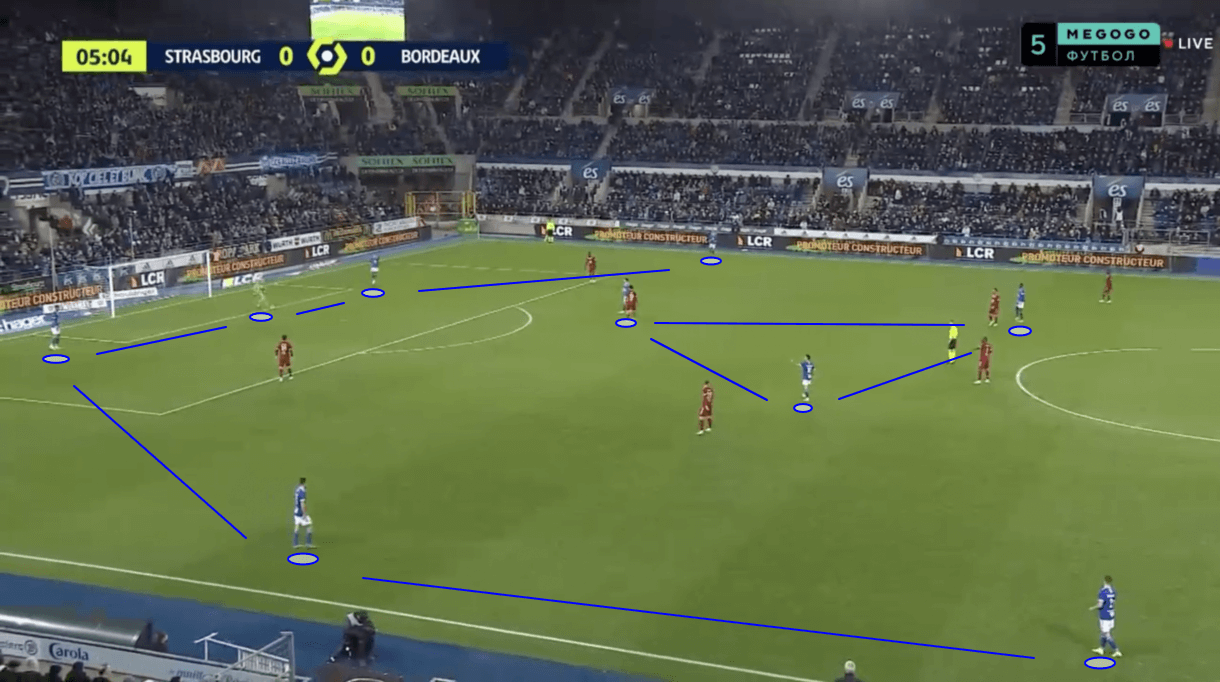

Strasbourg have primarily played with a 3-5-2 shape this season, and in the build-up phase it typically appears as we see it in figure 1. Two of the centre-backs (usually the central centre-back and left centre-back) split either side of the goalkeeper while remaining central, with the right centre-back pushing wider into more of a typical right-back position. The right wing-back sits higher, while the left wing-back sits deeper, corresponding with the right centre-back on the opposite wing. As play moves on into the ball progression phase, however, the left wing-back typically advances to correspond with the opposite wing-back, providing the offensive width for their side. Additionally, as play moves on from the very beginning of the build-up, the right centre-back returns to the centre, providing extra central protection for his side behind midfield.

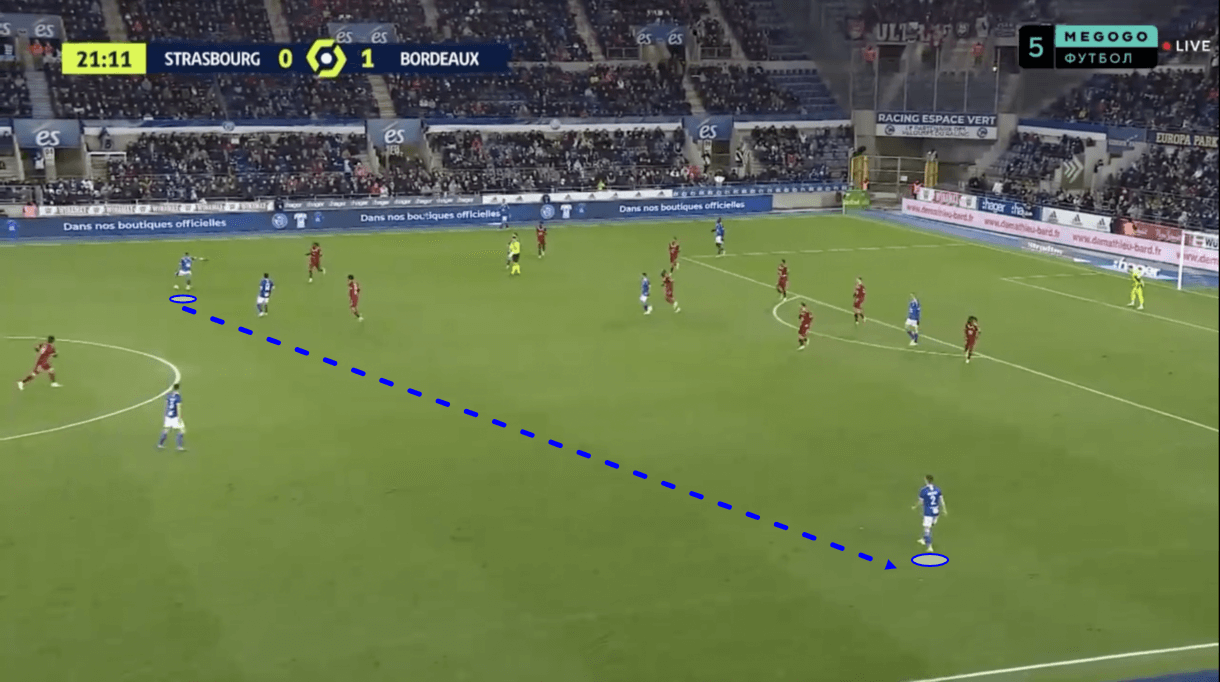

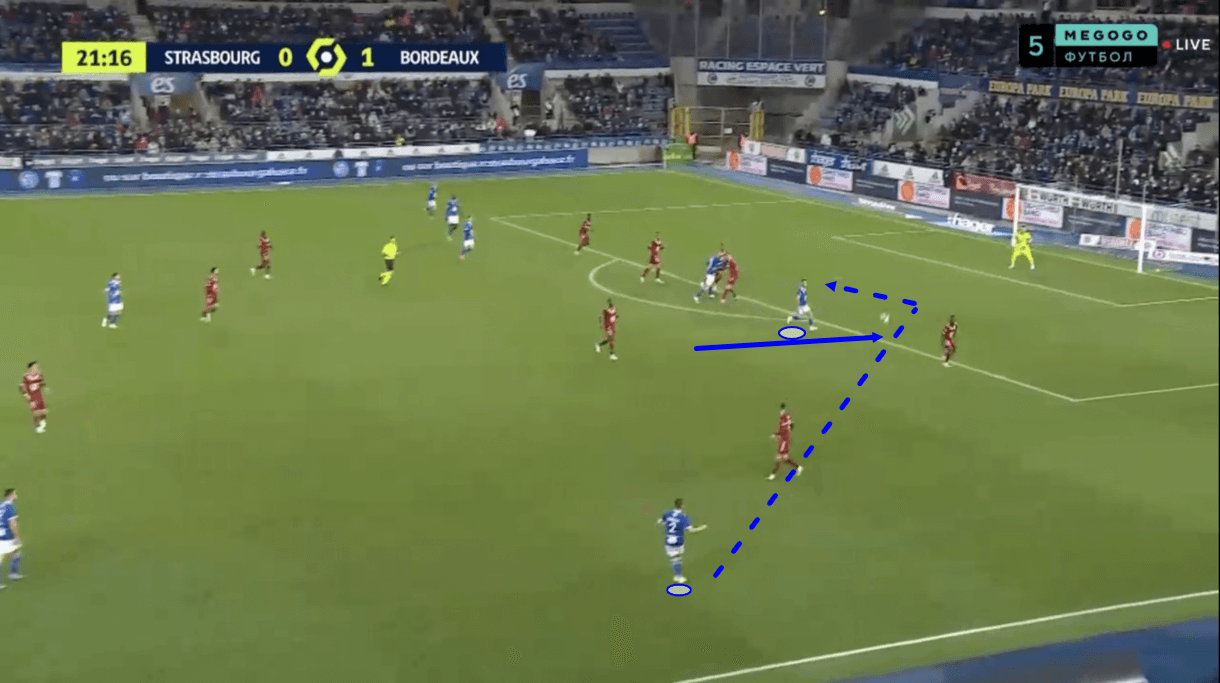

In figure 1, we see Strasbourg’s three-man midfield in their typical 1-2 structure, with Prcić operating at the base. However, we also see their opponents, Bordeaux, overloading Les Courers centrally by dropping the centre-forward in their 4-3-3 shape deep to mark the Bosnian. In one way or another, it’s very common for Strasbourg’s holding midfielder to be marked tightly in build-up as we see above to prevent him from receiving the ball and thus stifle Strasbourg’s progression. However, as mentioned, Strasbourg tend to find plenty of opportunities for progression despite that. To achieve this, it’s key for their midfielders to rotate positionally.

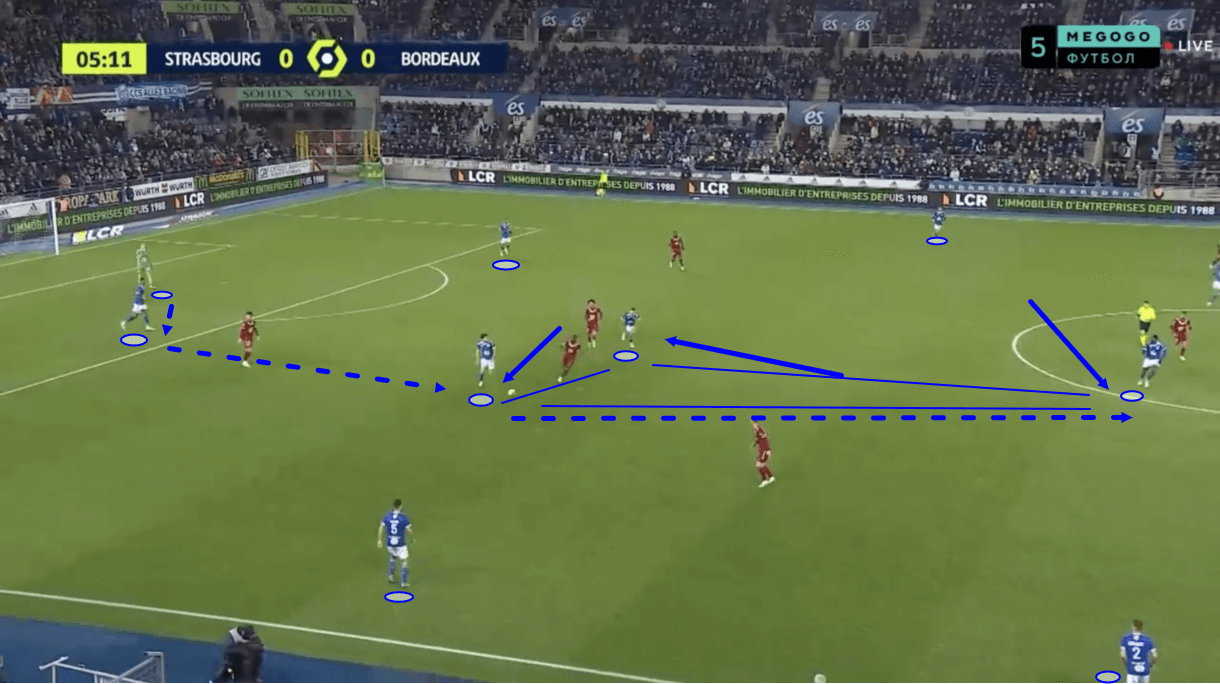

We see an example of how they did this to achieve ball progression on this particular occasion in figure 2. One of the two ‘8s’, Adrien Thomasson, dropped deep to form a double-pivot alongside Prcić when the ball was played into the Bosnian’s feet from a central defender behind him. This player dropping deep created a short passing option for Prcić, which the holding midfielder took, performing a one-two with Thomasson before carrying the ball across to the right holding midfield position.

This is where we find the scene from figure 2, where thanks to this bit of movement and quick link-up play, Prcić is facing forward and able to consider a progressive pass. At this point, we see that the holding midfielder has his two options on the right-wing (the wide centre-back and the wing-back) as well as a central option in the form of Jean-Ricner Bellegarde, the other ‘8’ and one of the best dribblers in this team along with midfield partner Thomasson, who remained high and becomes something of a ‘10’ at this point after his central midfield partner dropped to form a double-pivot.

With two of Bordeaux’s central diamond pulled high, following the double-pivot and one moving wider to retain access to the right centre-back and block the passing lane to the wing-back, Bellegarde is left 1v1 with the remaining Bordeaux midfielder, and we can see him running into space that Prcić can easily target with a progressive through ball from his position, effectively sending Bellegarde off into space. This passage of play highlights the importance of off-the-ball movement in achieving ball progression. In figure 1, we saw Bordeaux in a much more favourable position, with a central overload. However, thanks to Thomasson and Bellegarde’s movement, the link-up play between Thomasson and Prcić, and Prcić’s subsequent carry into this right central midfield zone, Strasbourg succeeded in ripping Bordeaux’s defensive structure open and creating an opportunity for central progression.

Positional rotations in central positions as we saw in figure 2 are very important to Stéphan’s strategy and tactics at Strasbourg. This team display some of the clearest and most effective off-the-ball movement in possession phases of any Ligue 1 side this season, which is why an example like the one above is so valuable for analysing their performance. This kind of play is a staple of their game and exactly what Stéphan wants to see from his side — using intelligent off-the-ball movement and short link-up play to force the opposition into worse positions in order to achieve progression. It sounds and looks very simple from this example because they’re doing this to a very high level, which is a testament to Stéphan’s coaching quality.

In my Stéphan at Strasbourg preview, I predicted that should he opt for Prcić in the holding midfield position, which I believed was a good fit due to the Bosnian’s on-the-ball quality, a base of three defenders playing behind him in possession would be likely as Stéphan may not want to risk playing the 2-1-2 structure (or 3-2 structure with Prcić as part of the ‘3’) he’d sometimes used at Rennes in this instance due to Prcić’s off-the-ball deficiencies and the weakness it would leave for Strasbourg in transition. This has been the case and I believe it’s successfully helped in getting the best out of the Bosnia and Herzegovina international, whose on-the-ball quality has a lot of benefits for Stéphan’s team.

Figure 3 shows an example of Strasbourg’s 3-1 shape in the ball progression phase. This is a very normal sight during this phase of play in Strasbourg games. Prcić can receive with his back to goal but thanks to his prior scanning and technical quality, is able to play a one-touch pass to a free man on the right wing quickly and effectively. Prcić, as well as Thomasson, play a lot of passes under pressure in this Strasbourg side. They rank in the top-four for ‘passes under pressure’ among Strasbourg players, along with Ajorque and Habib Diallo, though the other two are strikers which changes the dynamic.

For Prcić and Thomasson (the latter being an advanced ‘8’ at times, and a deeper midfielder at other times, as we’ve seen), though, this highlights the importance of technical passing quality and the diligence and intelligence to scan regularly to ensure they have as much information as possible about their surroundings, especially as they receive plenty of passes facing their own goal, as was the case in figure 3 — a common pressing trigger.

Thanks to their quality and Strasbourg’s possession structure, the two midfielders typically fare well in this system when receiving under pressure, hence why their teammates place so much trust in them to receive and play under pressure a lot. However, the base of three centre-backs behind them, whether it’s a 3-1 or 3-2 structure at the time, provides some extra padding compared to a 2-1 or 2-2 structure. As neither man is the perfect well-rounded holding midfielder who can perform the desired role in possession as well as offering a high-level defensive output, this structure helps add another layer of protection behind midfield to help in transition, should the under-pressure players get dispossessed.

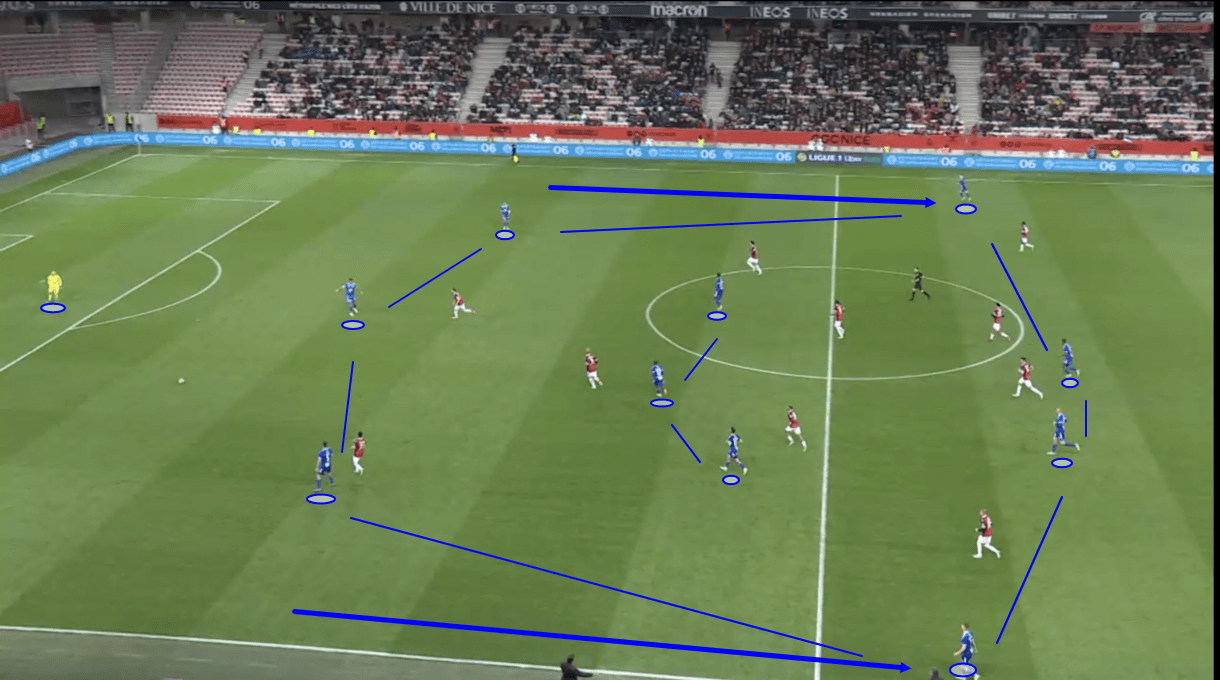

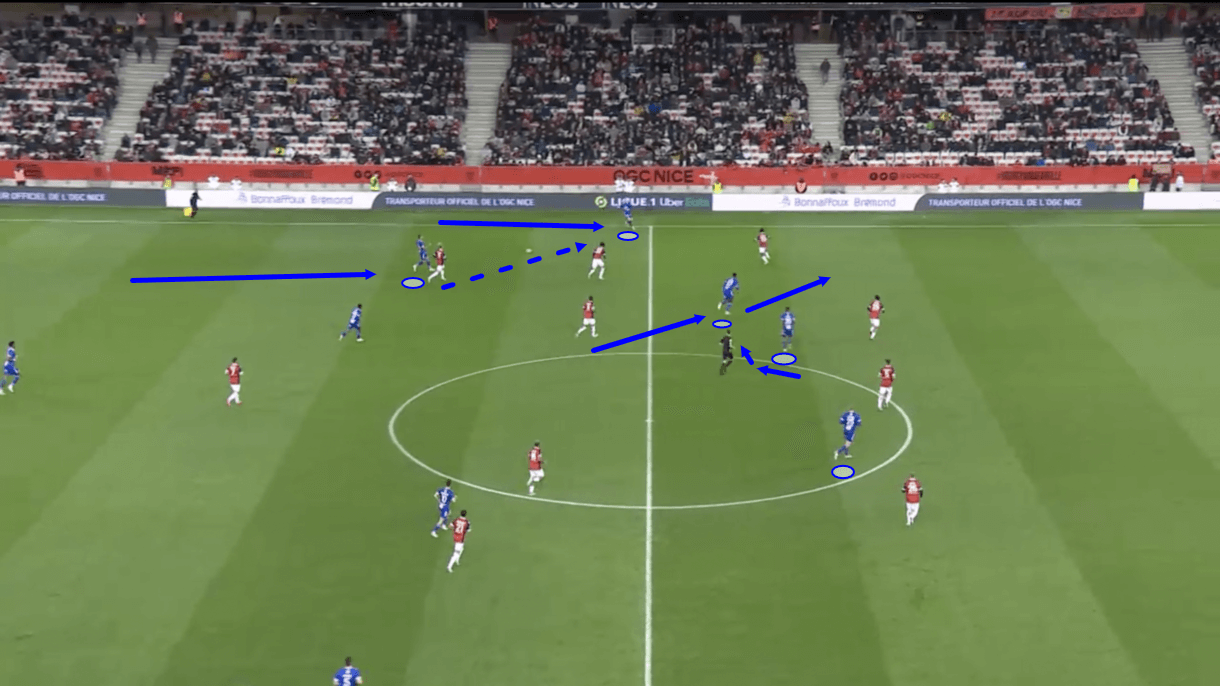

As well as providing some extra protection in transition to defence or other defensive phases, Strasbourg’s three-centre-back system has benefits in possession, one of which is evident in figures 4-5. During the progression phase and chance creation phase, it’s very common to see Strasbourg overload one side of the pitch, getting lots of bodies close to one another, as we see in figure 4, which shows Strasbourg in the progression phase. By doing this, Strasbourg can create opportunities to play through the opposition’s structure on this side of the pitch via some good link-up play between the closely positioned players that can create effective passing angles, good movement from advanced players to target holes in the opposition’s defensive structure, and incisive passing to ultimately target those holes.

To try and avoid this happening, Strasbourg’s opponents will probably commit more men to this side of the pitch to guard against the overload occurring in the first place, as was the case in figure 4, and this then leads to the space opening up on the opposite side of the pitch for Strasbourg to exploit. Again, this was the case in figure 4 above. Here, after overloading the left central midfield zone deep, Strasbourg create an opportunity to play the ball across to the right centre-back who has a lot of space in front of him to exploit due to the opposition committing lots of bodies to the other side of the pitch to prevent the overload. Although Strasbourg initially must play what in and of itself seems like a ‘negative’ backwards pass, this pass from the midfielder to the right centre-back adds a lot of threat because the centre-back can then carry it into the space in front of him and progress into a far more dangerous position.

This requires intelligence and good spatial awareness from the midfielder, as well as bravery and good technical quality from the right centre-back. Stéphan places a lot of responsibility and trust in his midfielders and centre-backs in possession, though, and is happy for them to be placed in these types of situations. On this occasion, as was the case on many occasions this season, the trust was rewarded.

As play moves on into figure 5, we see that the right centre-back carried the ball forward into space before releasing to the right wing-back. With one of Strasbourg’s ‘8s’ advancing in support along with the two centre-forwards moving over to the right from the left in support, this helps Strasbourg to quickly break through the opposition on this previously underloaded wing as the opposition try to reorganise themselves defensively. This passage of play highlights the benefit of Strasbourg’s three centre-backs in possession — they can provide an option deep in the half-space which can be very useful in helping Strasbourg to progress to the final third after having overloaded one side previously. This can be a different option to the big switch to the opposite wing for different game scenarios but the result can be just as devastating for the opposition, as the above example demonstrates.

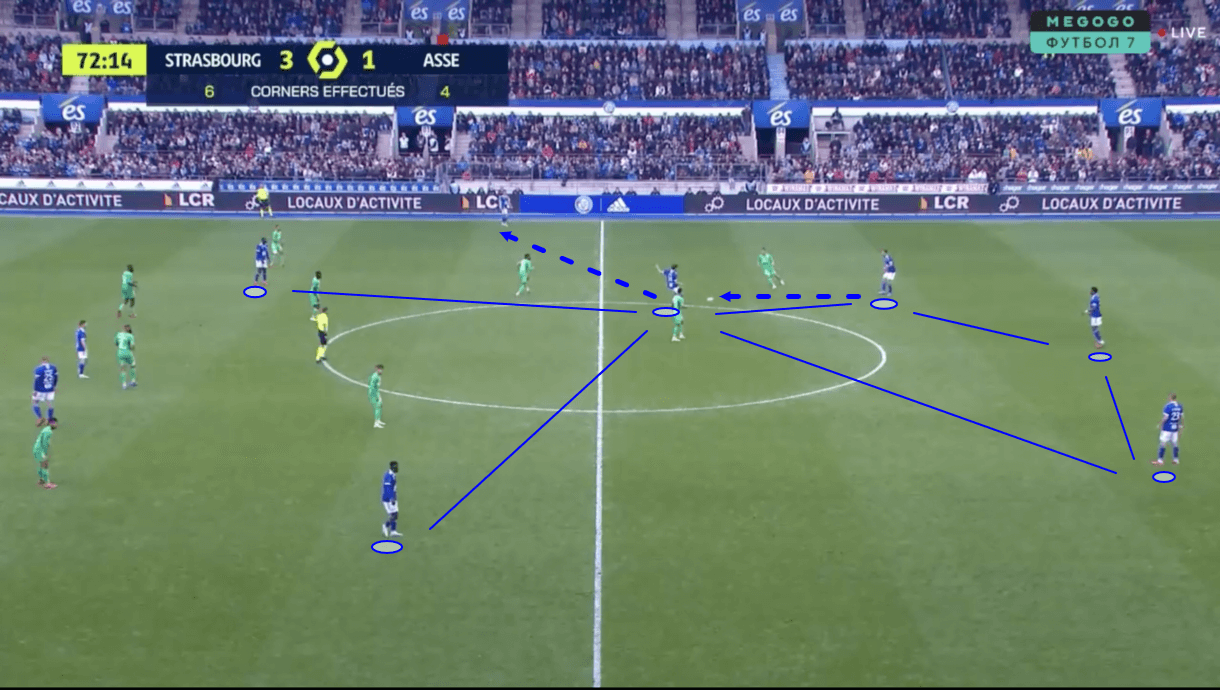

Figure 6 shows a good overview of Strasbourg’s shape in the build-up/ball progression phases. It’s worth noting how high and wide the wing-backs are in this example while looking briefly at their role. They always need to position themselves very high and very wide. As mentioned earlier, sometimes the left wing-back will be positioned deeper at the very beginning of attacks, but Strasbourg generally aim to set up the structure we see in figure 6, with both wing-backs high and wide, essentially forming a 3-3-4 shape. This positioning is important because these players are required to be available for big switches of play from an overloaded wing in the progression and chance creation phases. By being so high and wide, they position themselves well to exploit space on an underloaded wing.

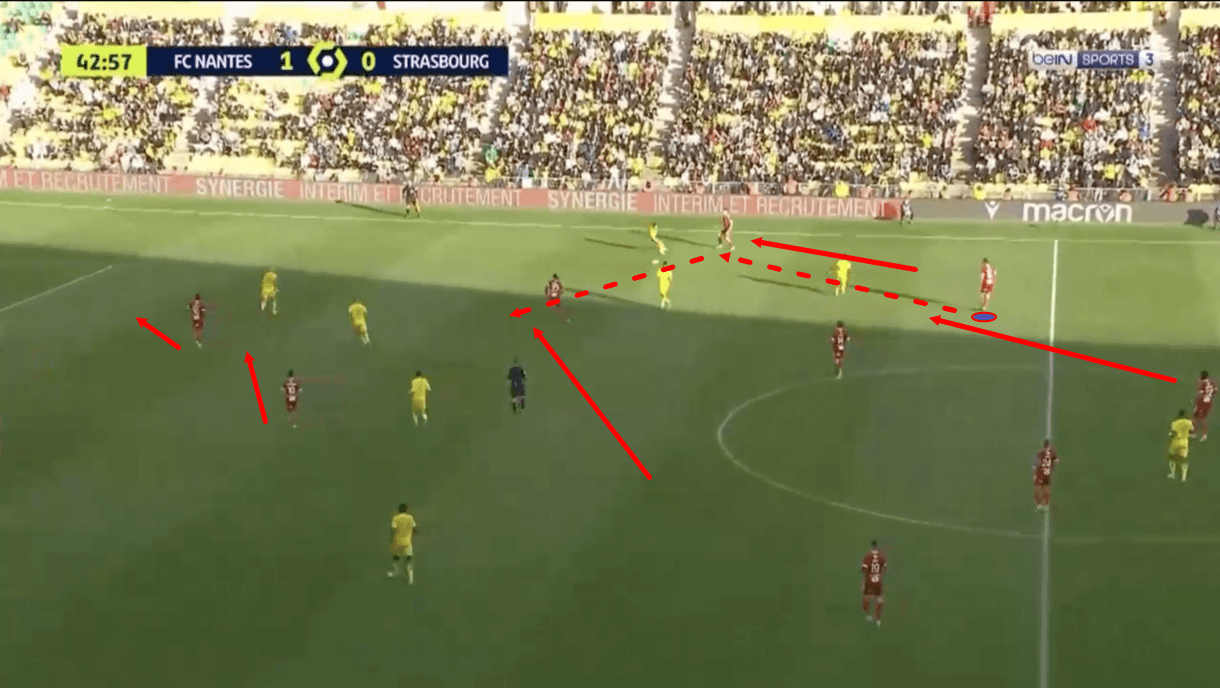

Our last point for this section is on Strasbourg’s long-balls. Les Coureurs have played more long passes (46.34 per 90) than any other Ligue 1 side this season, which is consistent with their performances from previous seasons but somewhat inconsistent with Stéphan’s previous teams. Nevertheless, some of these long balls inevitably come from goal-kicks. They generally try to play out via short passes from the back first and foremost but aren’t averse to immediately going long. Strasbourg typically set up as we see them in figure 7 when playing long balls from goal-kicks. They aim for one of their centre-forwards who’ll drop slightly deeper, with the other centre-forward running off them in behind to collect a knock-on. Meanwhile, the central midfielders will shift over to provide support to the striker as well, along with the near wing-back. Should the ball be knocked back into midfield, Strasbourg position themselves well to capitalise on it and keep possession by winning the second ball.

Ajorque and Diallo are both strong forwards in the air, so either one can act as the target for this long ball. Kevin Gameiro, however, is not as good in the air so will generally play as the forward running off in behind for a knock-on in this scenario, rather than the one contesting the aerial duel.

Chance creation

To reiterate, only star-studded PSG (36) have scored more Ligue 1 goals than Strasbourg (34) this season, which is particularly impressive when you consider that Les Coureurs weren’t a particularly high-scoring side in previous seasons. For example, they ended last season as Ligue 1’s 12th-highest scorers and they were the 11th-highest scorers in France’s top-flight the season before that. Les Coureurs also currently have the seventh-highest xG in Ligue 1 (25.14) which indicates they’re creating enough to be performing better in front of goal than in previous seasons.

The obvious thing to mention at this point is their significant xG overperformance. Strasbourg are overperforming their xG by more than any other Ligue 1 team — and by a significant margin. Why is this? I think a large reason for this is Strasbourg’s large portion of headed goals. Headers are naturally assigned a lower xG value than regular shots, but eight of Les Coureurs’ 34 goals (23.5%) have come via headers this season (the second-most headed goals of any Ligue 1 side), with some of them getting assigned a very low (below 0.1) xG. Some low xG long shots from Diallo and Bellegarde have also played a part in this overperformance but long shots have been something of an exception to the rule for Les Coureurs this term, with Stéphan’s side taking shots from the joint-third closest distance to goal (16.2m) on average, compared with other Ligue 1 sides this term.

In Ajorque, who’s scored four headed goals, Strasbourg have a centre-forward who’s very dangerous in the air and while I wouldn’t expect such overperformance to continue, it’s played a major part in the Alsace-based club’s impressive start to the campaign. Stéphan has done a great job of setting up high-quality headed opportunities for Ajorque and other attackers. In order to take advantage of this aerial danger, Strasbourg tend to make a lot of crosses. They’ve made the second-most crosses (15.65) of any Ligue 1 team this season, with the fifth-most accuracy (35%).

Both of their wing-backs play a key role in their attack by providing width high and wide on each flank at all times to get onto the receiving end of switches. After receiving a switch, these players generally have lots of time to set up a cross, which in turn sets up a goalscoring opportunity for the attackers in the box if all goes to plan. Overloading one wind to switch and exploit an underloaded wing has been a key part of Stéphan’s tactics at Strasbourg thus far and it was also a key part of his tactics at Rennes before this. This season, Les Coureurs have made 301 switches, per FBRef, which is the second-most of any Ligue 1 side, highlighting how prominent this style of pass is in their game.

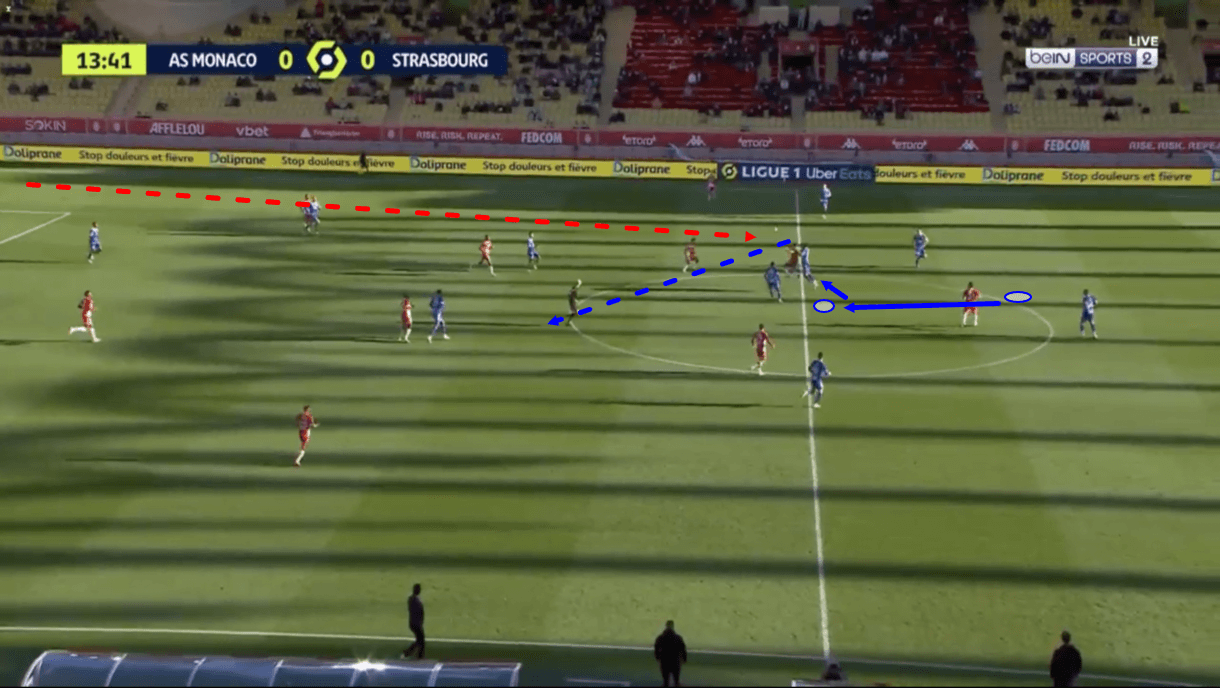

Figure 8 shows an example of an occasion when Strasbourg overloaded the left wing, threatening to play through the opposition on this side and thus dragging their defensive shape over to that wing, before switching to find the right wing-back in lots of space. It’s a very important part of Prcić’s game to get into enough space to pull off these switches, and thanks to his spatial awareness and technical quality, he tends to do so without issue, making him a key player for Stéphan in all possession phases.

In this particular example, as play moves on into figure 9, we see the cross come in from right wing-back Frédéric Guilbert, who’d enjoyed plenty of time to set himself and pick his target. We also see that the opposition’s defensive shape has started to shift over to this wing in reaction to the switch to try and close down Guilbert and this highlights another big positive of Strasbourg’s switches in the final third — they can successfully stretch and open up the opposition’s defensive shape in central areas due to player’s moving out of their compact positions to close down the ball-carrier in reaction to the switch.

On this occasion, we see a lot of space has opened in the very centre of the pitch following this switch, and that space could be exploited, but some space has also opened up in the channel between the opposition’s left-back and left centre-back, which right central midfielder Thomasson can be seen targeting with his run into the box.

Having enjoyed lots of time and space following the switch, Guilbert picked out Thomasson with his cross, setting him up for a headed goalscoring opportunity that he took, drawing Strasbourg level with Bordeaux. Switching to an underloaded wing from an overloaded wing is a crucial part of Strasbourg’s game in the progression and chance creation phases, and this passage of play shows exactly why that’s the case as it highlights the direct benefit of finding the high and wide wing-back in lots of space on the underloaded wing, as well as the indirect benefit of this action, which is that it draws the opposition out to this side, stretching the opposition’s defensive shape and creating more space centrally for the wing-back and his teammates off the ball to exploit with either a pass or a cross, with an example of the latter seen above.

Strasbourg’s wing-backs sometimes carry the ball forward to cross from a more advanced position in a situation like this, but as was the case above, it’s also common to see them cross from deep and they’re happy to do so. The attackers’ movement is also key, with figure 9 providing an example of Thomasson targeting the blind side of the full-back in front of him with his run into the box. It’s been common to see Strasbourg’s attackers make intelligent runs like this, which helps them to enjoy good headed opportunities.

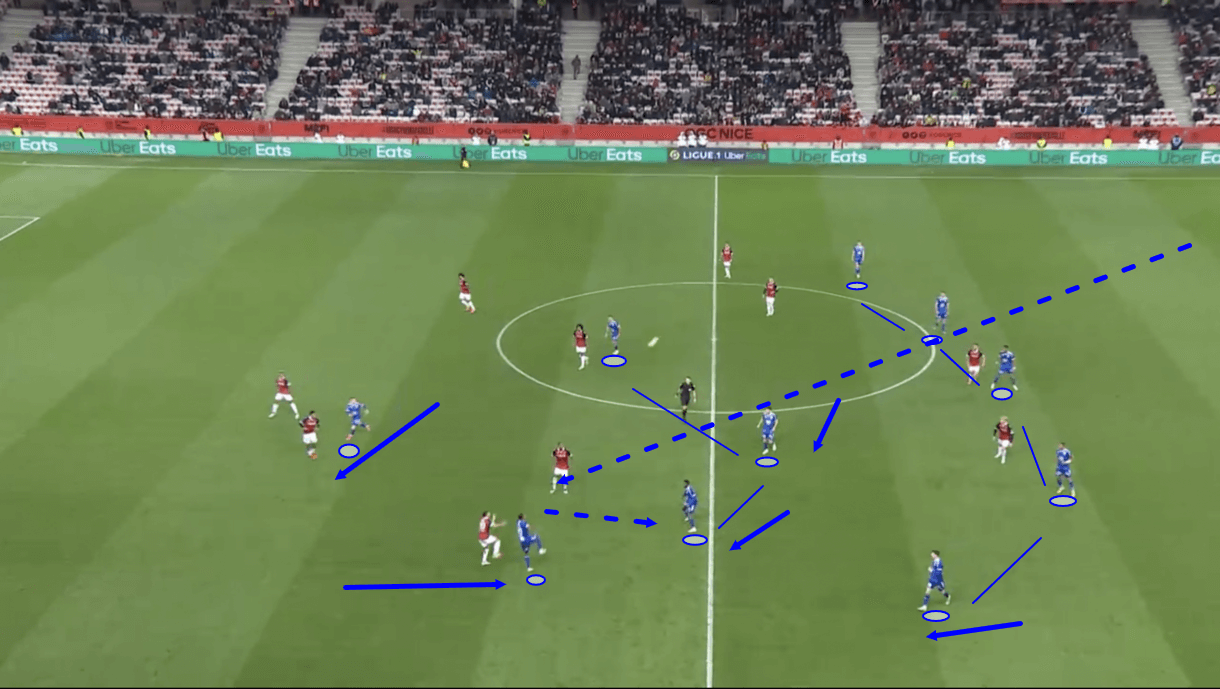

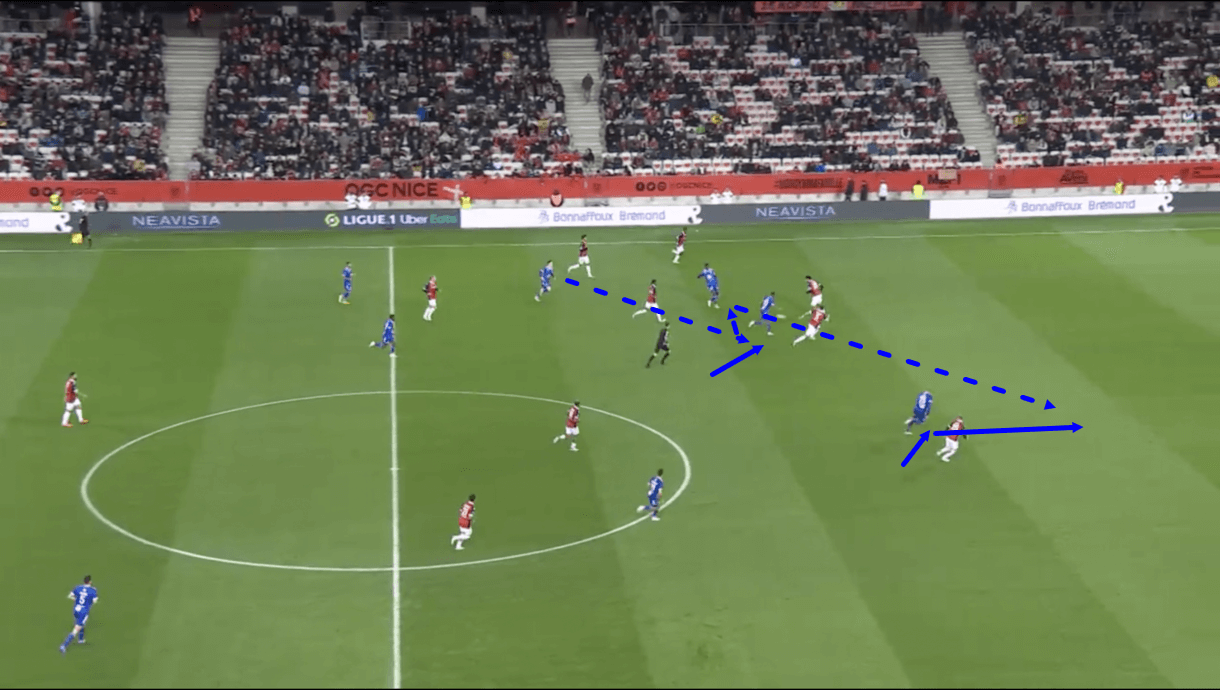

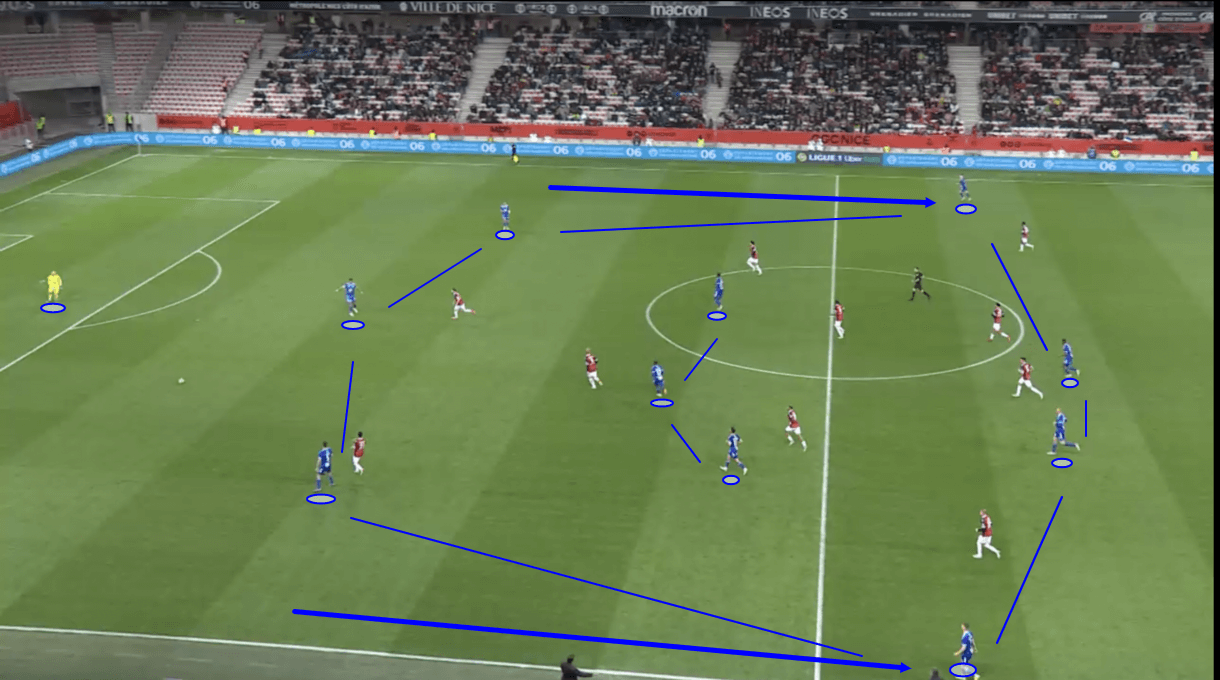

Of course, in order to enjoy the good opportunities to switch play by exposing an underloaded wing, the opposition need to be drawn to one side of the pitch first and Strasbourg need to pose a legitimate threat on the overloaded wing too, which they have this term. Figures 10-11 analyse a passage of play from Les Coureurs’ most recent Ligue 1 clash with Nice in which they scored a goal resulting from a passage of play where they successfully played through Nice’s defensive shape on the overloaded side. This highlights another purpose of this overload and how dangerous it can be in and of itself. Off-the-ball movement, incisive line-breaking passing and quick, crisp, intelligent link-up play are key for Strasbourg when looking to play through the opposition’s defensive structure as we see in figure 10.

Just before this image, the left centre-back carried the ball forward and found the left wing-back out wide. While the opposition shifted over towards their right-wing and their right-back was drawn out to the ball-carrier, Bellegarde made his way forward from Strasbourg’s left central midfield position to exploit the space opening between the opposition’s right-back and right centre-back. This highlights an important part of the ‘8s’ role in Stéphan’s system — just as they have freedom to drop deep to form a double-pivot alongside Prcić, they have freedom to join the front two and overload the opposition’s backline by forming a front-five alongside the two strikers and two wing-backs. As Bellegarde pushed forward, Strasbourg’s left centre-forward, Diallo, demonstrated some good movement by moving over to look for a pass to feet.

In figure 11, we join the play after Strasbourg’s wing-back found Diallo with a pass to feet, with the left centre-forward acting as a wall to send the ball into Bellegarde right beside him but facing towards goal, rather than away from it like Diallo. By this point, the opposition’s right centre-back has been drawn to the left by Diallo and Bellegarde’s movement and link-up play, which essentially breaks the link between the right centre-back and right-back, creating space for Diallo’s strike partner and Strasbourg’s top goalscorer this season, Ajorque, to target with his run, which he does as we see above.

From here, Bellegarde sends a through ball into Ajorque’s path which has opened wide thanks to the movement from his teammates that dragged the opposition out of position. As play moves on from here, we see Ajorque finish the ball to take the lead for his side in the 21st minute.

This highlights how off-the-ball movement, quick, crisp link-up play, and incisive final balls, like the through ball from Bellegarde here, combine to help Strasbourg play through the opposition’s defensive structure and create high-quality goalscoring opportunities. Strasbourg often employ tactics like this successfully on the overloaded wing in the final third, which is why the opposition must commit bodies to protect the overloaded side heavily. In turn, this then leads to space opening on the opposite wing for Strasbourg to switch to, which highlights the conundrum that Stéphan wants his team to create for their opponents. They’ve done this very successfully this season, leading to their high scoring campaign.

Defence

Defensive phases are very important for a team’s ability to put the ball in the opposition’s net and not just to keep the ball out of their own net, so while this article focuses on answering the question: ‘why are Strasbourg Ligue 1’s second-highest scoring side right now?’ I don’t think simply looking at what they do with the ball tells the whole story so we’ll spend some time looking at how Strasbourg’s performance in defensive phases influences their attacking play.

Stéphan generally likes his teams to press aggressively and Strasbourg’s PPDA this term is 11.63 (the eighth-lowest in France’s top-flight and lower than last season’s PPDA of 14.65). As per FBRef, they’ve also made 570 pressures in the attacking third (seventh-most) and 54 tackles in the attacking third (second-most). So, Strasbourg are certainly more aggressive than they are passive this season. However, per FBRef, Strasbourg have interestingly made the fewest defensive actions leading to a shot (five) of any team in France’s top-flight this season, which suggests that they could be doing a better job of creating dangerous counter-attacking opportunities as a result of their high tackles and pressures.

This is a definite potential area of improvement for Les Coureurs, as many that immediately after regaining possession is one of your best chances to score because you can exploit the opposition’s disorganisation in transition. If they aren’t taking advantage of this, then that’s a major area to potentially make some gains in the future, especially since they’re making so many pressures and tackles in the attacking third.

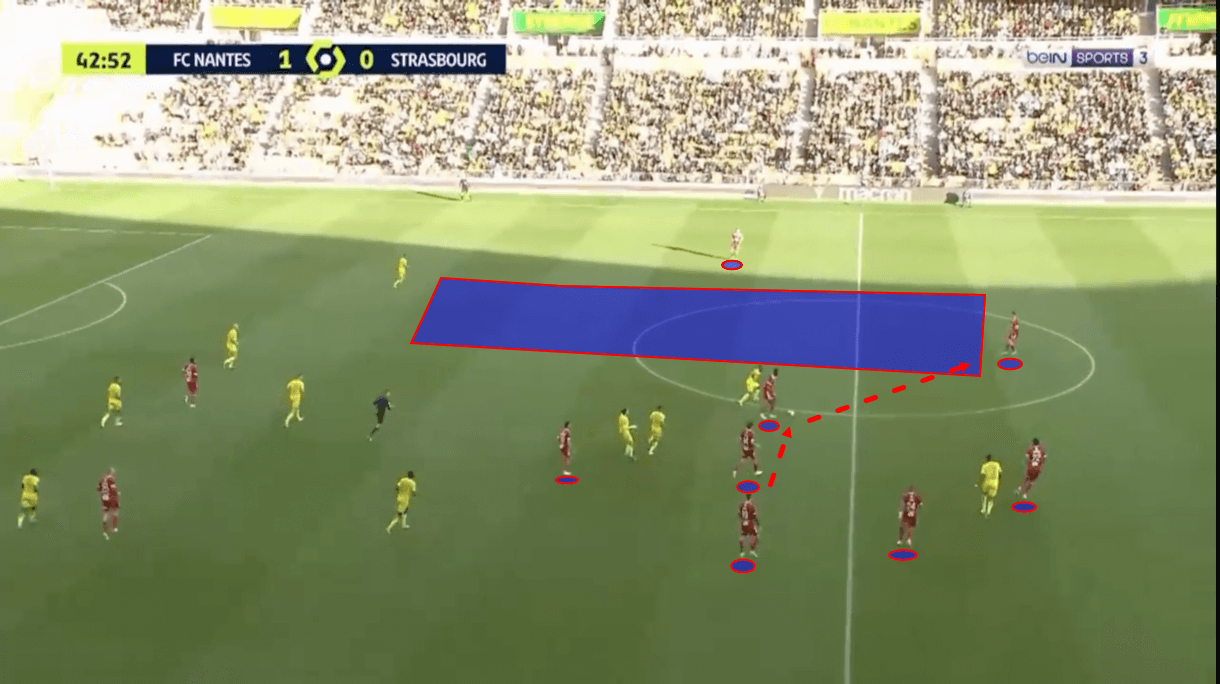

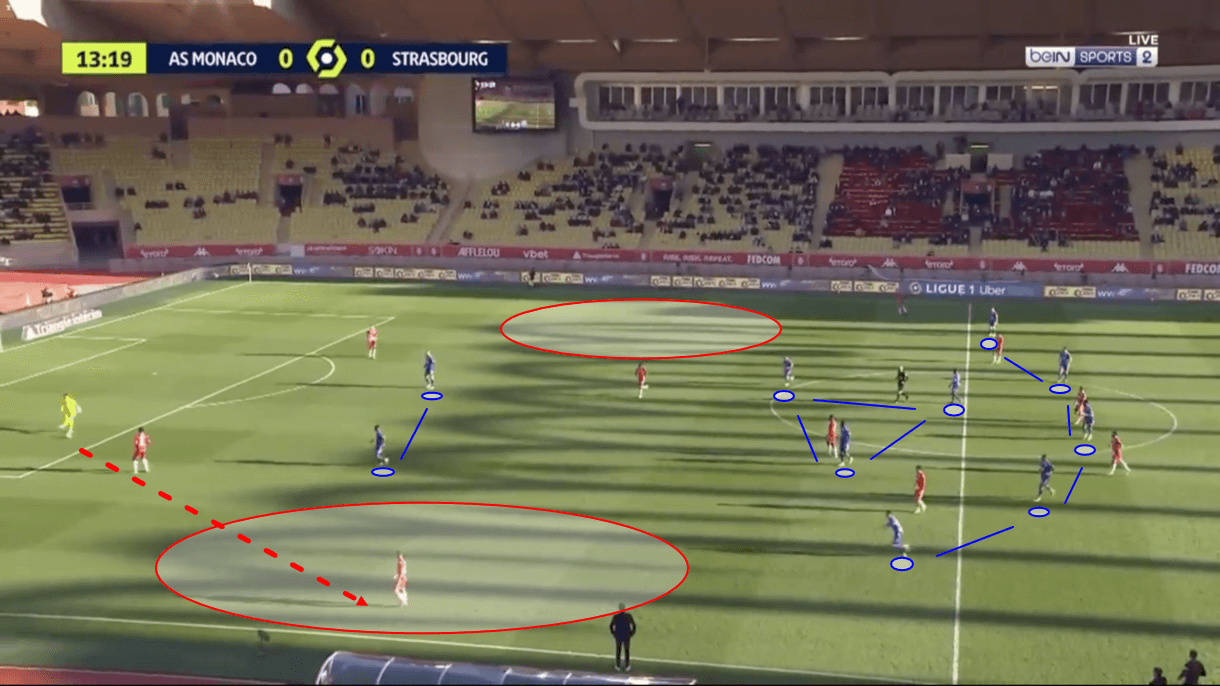

In their 3-5-2 / 5-3-2 system, Strasbourg primarily look to protect space in the centre and in deeper areas of the pitch. As a result, they’re usually happy enough to allow the opposition space to play out wide where the full-backs typically roam. These areas are marked clearly on figure 12 above. Deep and wide is typically regarded as the least threatening place for the opposition to be in possession of the ball, so if Strasbourg are making the decision to give up some territory anywhere in favour of packing the more threatening central and advanced areas, it may make some sense why they tend to choose this area.

When the ball is played into this position, as was the case in figure 12, Strasbourg’s wing-back will make some movement towards the receiver to close them down while the rest of Strasbourg’s back-five shifts over, resulting in something of a 4-4-2 formation with a very narrow midfield being formed. This can help to congest the centre and close down space around the ball carrier.

However, this has some weaknesses too. Firstly, Strasbourg’s ball-near wing-back has a lot of space to close down which can give the receiver time to come up with a plan to get past him either individually or via some link-up play, and secondly, Strasbourg’s narrow shape, especially in midfield, leaves them vulnerable to switches of play.

On the positive side of things, however, they congest the space around the wide ball-carrier very well, can use the sideline as an extra defender to cause the ball-carrier problems, and if they manage to close down the man on the ball enough to prevent the switch from being a viable option, they can really increase their pressure on the ball-carrier a lot while marking near passing options to force a turnover.

This remains consistent when Strasbourg are defending in their own third. They prioritise protecting the centre and the deeper areas first, being willing to leave space open deeper on the wing, while they continue operating with a centrally narrow 5-3-2 / 4-4-2 (depending on whether or not the wing-back is pressing aggressively at the time).

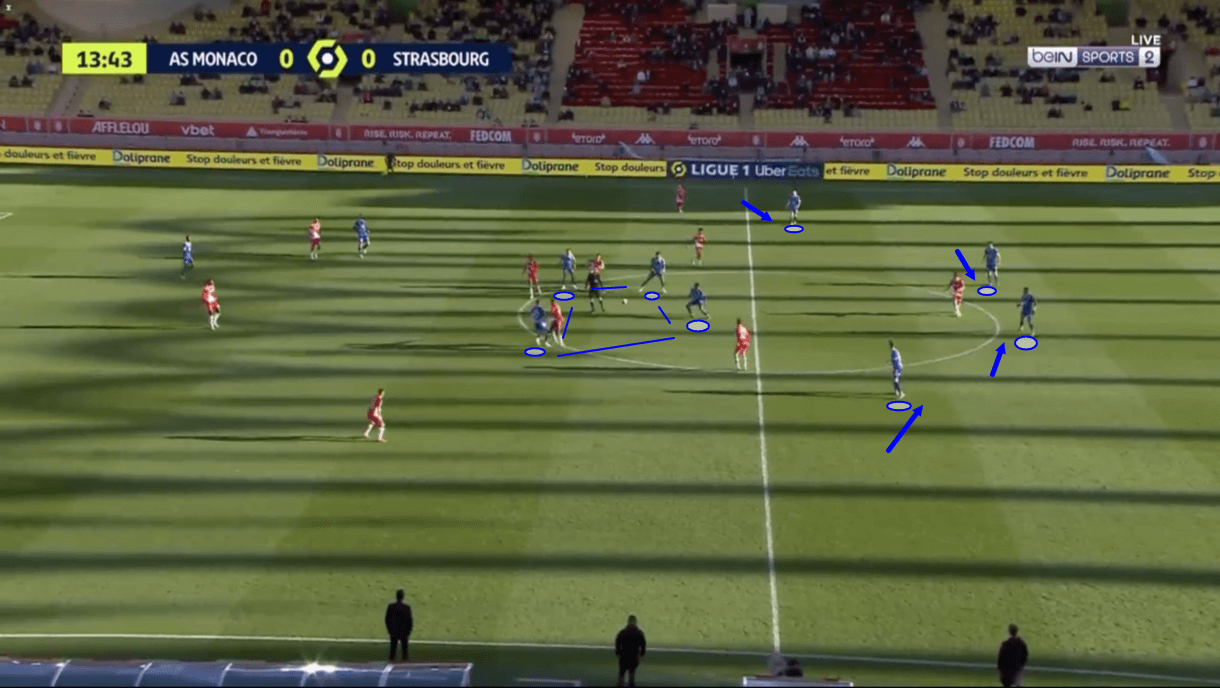

If the opposition are forced long, they must send the ball into an advanced position where, as we saw in figure 12, Strasbourg typically have a lot of bodies positioned. We see an example from this game versus Monaco of when Les Monégasques did attempt to go long in figure 13. Strasbourg don’t have a great aerial threat in midfield, so one of their centre-backs generally has license to step out and contest the aerial duel when necessary, as Nyamsi — Strasbourg’s most aerially-proficient centre-back — did in the image above.

As this passage of play progresses into figure 14, we see the benefit of Strasbourg’s congested central area within the context of aerial duels. After Nyamsi knocked the ball down into central midfield, where Strasbourg have packed a lot of bodies, they can win the second-ball and regain possession around the halfway line. This is common for them and highlights 1. The benefit of Nyamsi’s aerial quality and 2. The benefit of their tight central midfield.

Additionally, it’s worth noting how when Nyamsi advanced to congest the aerial duel, the rest of the back-five quickly contracted to form a tight back-four behind the midfield in case possession was lost. As a result, Strasbourg were left with a solid safety net behind the midfield to protect against the possible transition. After regaining possession here, Strasbourg could kickstart a counter-attack. Counter-attacking opportunities from central midfield like this one are why this bit of defensive action can be a positive for Strasbourg in terms of their offensive play. Again, though, they haven’t been great at quickly turning defensive actions into shots this term.

Conclusion

To conclude this tactical analysis piece, I feel Strasbourg’s high goalscoring term so far can be attributed to the solid in-possession structure that Stéphan has set up for them, the players’ intelligent off-the-ball movement and central rotations, their application of quick passages of link-up play to break the opposition down, their tendency to exploit underloaded wings via switches and their ability to take advantage of heading really effectively — especially Ajorque’s heading.

They still have plenty of potential areas of improvement, including their ability to create shots from defensive actions and counter-attack that way, but Strasbourg are evidently enjoying an excellent campaign and I hope this piece shines a light on why this team’s work is rightly getting rewarded at the moment.

Comments