FC Südtirol are quite possibly the most interesting case study of a side that have gone against the grain of modern football, adopting principles that many have shunned over the past half a decade — a throwback to a simpler and more cultural time in Italian Calcio.

The 2021/22 campaign saw Südtirol complete the greatest achievement in the club’s history by getting promoted to Serie B for the first time ever.

In the 2013/14 season, the intriguing club from the German-speaking indigenous region of South Tyrol in Italy were just a playoff final against Pro Vercelli from reaching the second tier but were unfortunately defeated. Supporters’ dreams were crushed, and the fans would be forced to wait eight whole years before these dreams would be realised.

But the wait was worth it. On the final matchday last season, Südtirol won Serie C under former boss Ivan Javorčić, earning promotion to the second division for the first time in history.

Stability was now of vital importance. However, things didn’t start very well. Javorčić stood down and moved to Serie A-relegated side Venezia, who were back down in Serie B. The board turned to a man who had guided Cosenza to safety last season in the same league, hoping he would work his magic in Bolzano.

Thankfully, Pierpaolo Bisoli has done more than enough to keep them up. There is now a chance that Südtirol could make the step up to Italy’s top flight, currently sitting fourth in Serie B, playing a style which is closer to the infamous Italian Catenaccio approach than any other team in the country — or in Europe for that matter.

In this tactical analysis piece for the TFA Magazine, we take a look at the incredibly effective tactics that Bisoli is using at the Drusus Stadium which could see the minnows from South Tyrol reach a feat nobody thought possible at the beginning of the campaign.

Not everyone’s cup of tea

Full disclosure before we begin the analysis, Südtirol’s style of play is not the easiest on the eye. For the Pep Guardiola and Marcelo Bielsa lovers and purists, Bisoli’s tactical set-up may not be your cup of tea.

However, there is almost a refreshing aura of the team’s style in an age where everyone wants to play ‘the right way’. Many coaches want to be seen as being progressive, too afraid to hit a long ball in fear of their style being labelled ugly and unpleasant, and adamant about controlling games with the ball than without.

But there is something of an invigorating feeling watching a manager completely unphased about obliging with the norm, keeping in line with a cultural style which dominated the country for the guts of six decades. Some may call this anti-football but there are no rules about what constitutes good and bad football. Styles are subjective and ultimately, coaches will be judged on their ability to win games. As José Mourinho once famously said: “There are many poets in football, but poets don’t win many titles.”

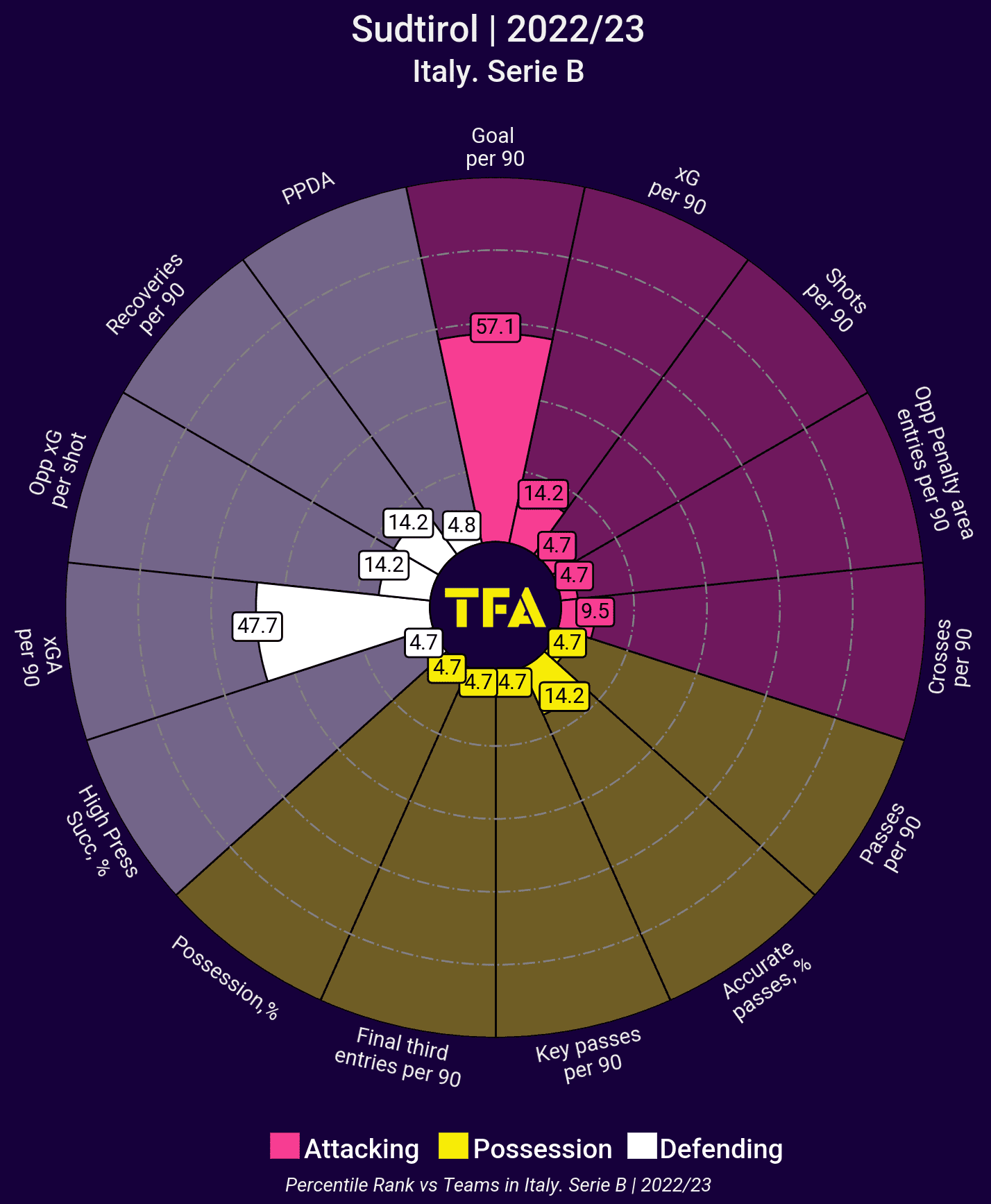

With that being said, let’s take a look at Südtirol’s pizza chart from this season under Bisoli to see exactly what we’re getting ourselves into.

At first glance, without any context, one would be forgiven for believing that Südtirol were down at the foot of the league. Instead, the Biancorossi are comfortably sitting in fourth as of writing, six points above fifth-place Pisa and five points behind second-placed Genoa.

They are one of the lowest-ranked teams in every single metric apart from one — the one that matters the most in football, which is goals.

Last season, under Javorčić, the Italian minnows averaged 53% of the ball per game. This season, the number has fallen to 38%. Of course, the difference in quality between Serie C and Serie B would cause the percentage to drop, but the fall is too significant to be attributed to this alone.

There has been a clear shift in styles under Bisoli compared to his predecessor and this has enhanced the team’s ability to compete in a much tougher league.

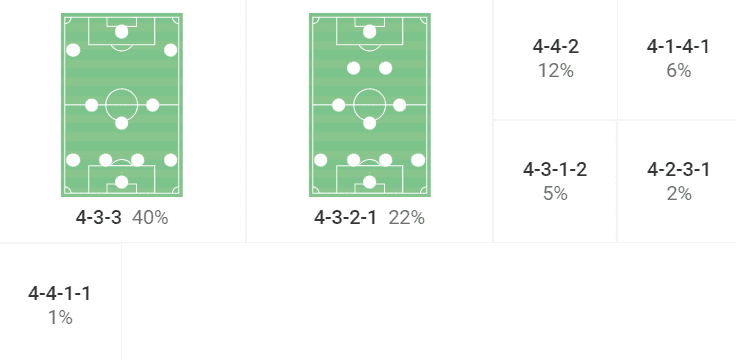

There has also been a change in formation from last season too. Javorčić preferred to use the 4-3-3 in games, allowing Südtirol to control matches with the ball.

Upon arrival in South Tyrol, Bisoli changed this. Despite using a 3-5-2 for the most part during his stint with Cosenza in the 2021/22 campaign, the experienced coach went with a 4-4-2 once Südtirol made the leap up to the second tier.

Bisoli clearly believed that the 4-4-2 got the best out of the players at his disposal and, well, it’s hard to argue with him considering how well the side have done this season.

But there’s no point dwindling on formations and shapes for too much longer. Formations are merely a starting reference for players to understand their base positions on the field and do not dictate the principles that a team uses in and out of possession. There’s a big difference between a 4-4-2 used by Sir Alex Ferguson, Arsène Wenger and Bisoli. So let’s deep-dive into why Südtirol’s 4-4-2 has been so effective this season.

Ceding possession

Bisoli is fine with allowing the opposition to have the ball. In fact, he almost encourages it as his team averages the lowest share of possession in Serie B by far. Perugia are second with 44% to Südtirol’s 38%.

This is very reminiscent of another quote from the Special One from perhaps the most historic win of his entire managerial tenure (and that’s saying something!):

“We didn’t want the ball because when Barcelona press and win the ball back, we lose our position – I never want to lose position on the pitch so I didn’t want us to have the ball, we gave it away.”

And yes, comparing Südtirol’s style to a game when Inter were defending a lead against possibly the best team in the world while playing with ten men for most of the match may seem futile, but Bisoli’s approach is highly reminiscent of that brilliant night in Barcelona.

Südtirol are more than happy to allow their opponents to have possession of the ball and to come after them with waves and waves of attacks. They look to control games by controlling the space rather than the share of the ball.

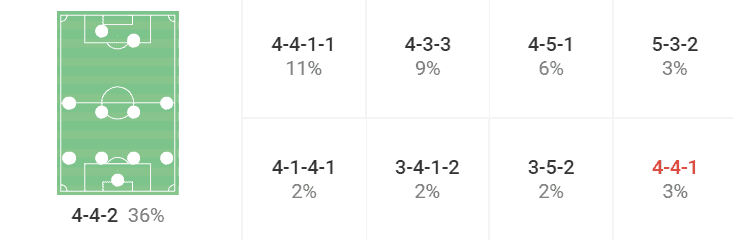

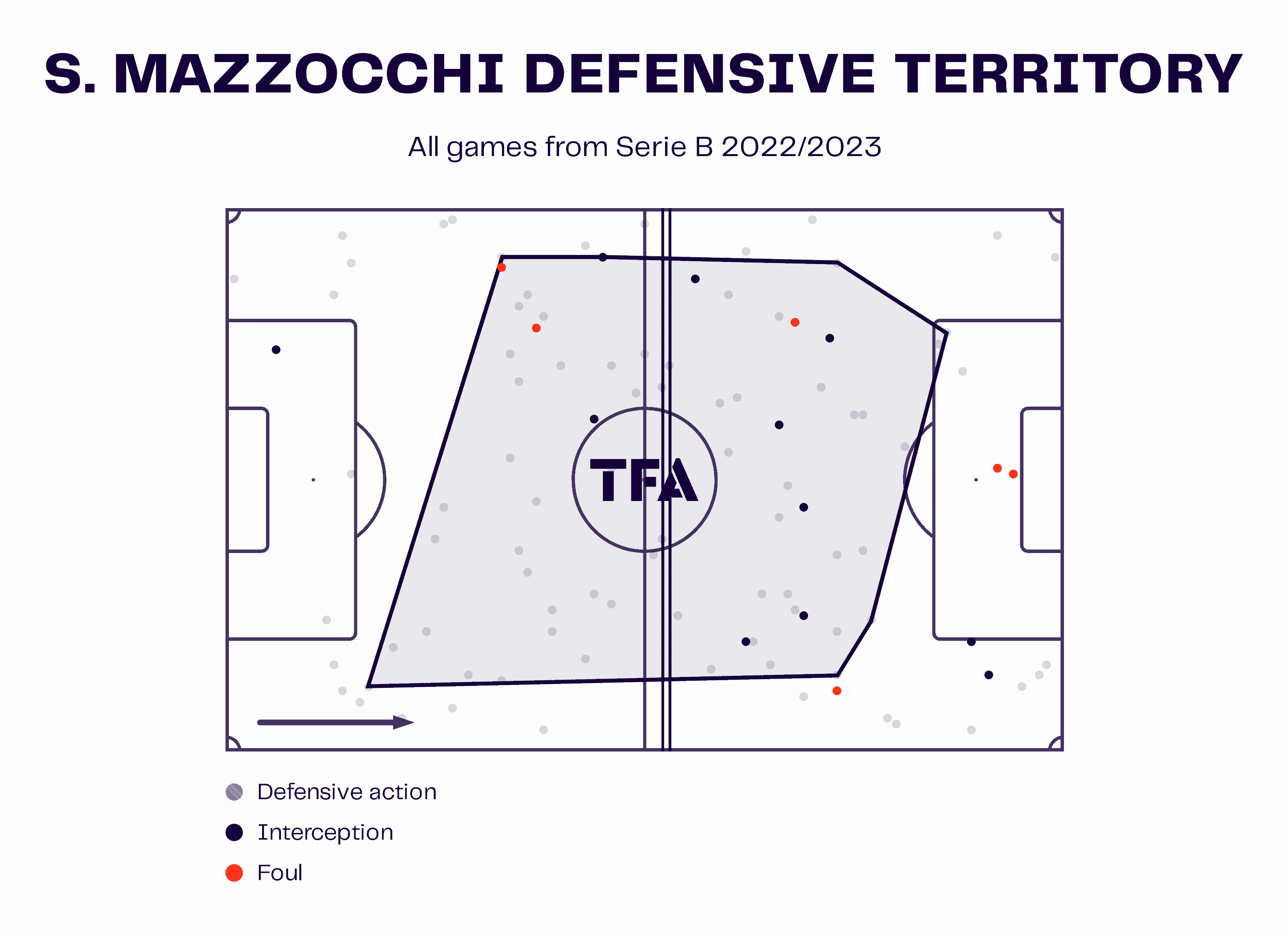

This is evident from Südtirol’s defensive territory map this season. The team’s average defensive line height is closer to their own box than the halfway line.

Südtirol don’t engage high up the pitch, preferring to drop back into their defensive shape to close the distance from the backline to the goalkeeper which discourages opponents from playing over the top. The attacking side must play through Südtirol’s 4-4-2 low block which is much easier said than done.

Here, we can see centre-forward Simone Mazzocchi’s average defensive line height which is the area where he begins to engage in pressing the ball-holder. Mazzocchi’s line of engagement is practically at the halfway line.

The first line have no interest in applying any pressure inside the opposition’s half, meaning teams can build out from the back unscathed, although this becomes redundant. Teams play out from the back to entice their opponents to press high up the pitch, leaving gaps in behind the defensive line to be attacked. Against Südtirol, this space is never available.

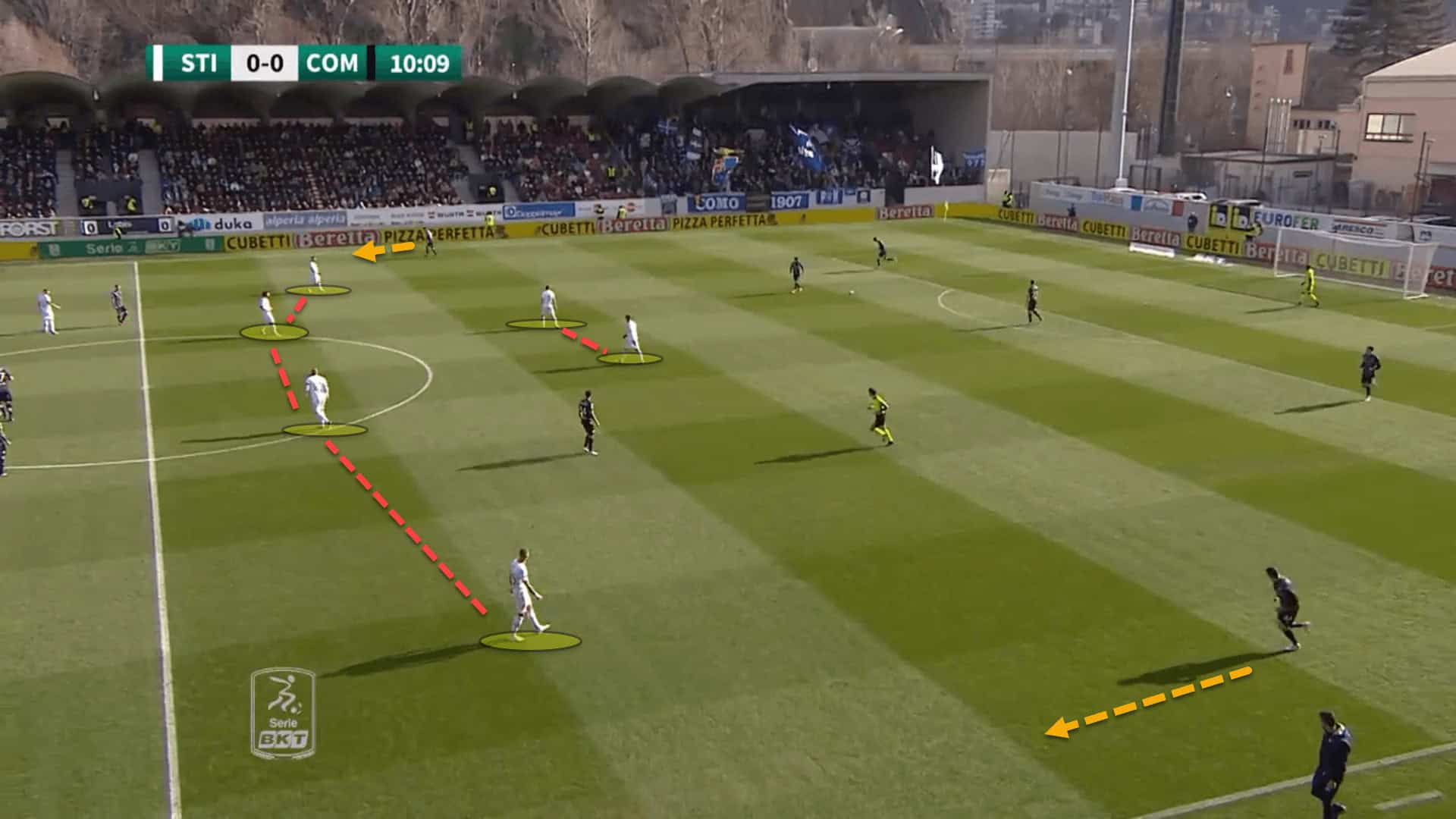

In this example, visitors Como didn’t even need to properly set themselves up to build out from the back. There was no point. Südtirol had no interest in engaging with them in the final third to win the ball close to the goal. Instead, the Como players just began advancing under no pressure, setting up in a positional attacking structure well inside the opposition’s half.

Even when the team in possession reach the halfway line, Südtirol don’t press the centre-backs. Bisoli wants his two strikers up top to sit on the opposition’s deepest midfielders, particularly when playing against a double-pivot.

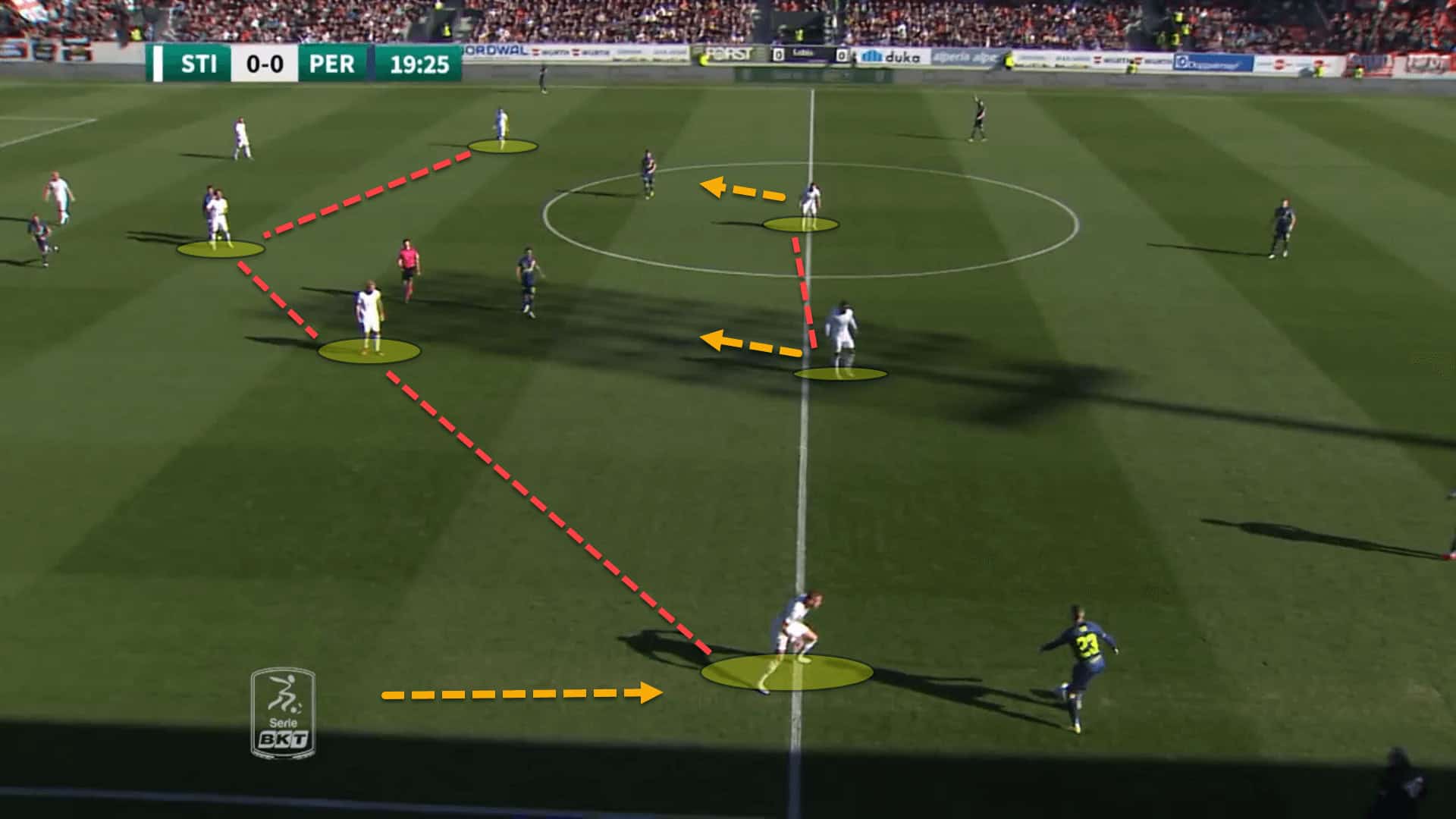

Here, Südtirol are sitting in their typical 4-4-2 low block. The right-winger has jumped forward to press Perugia’s left wingback, but the three centre-backs are free to receive under no pressure at all.

The Biancorossi’s two centre-forwards are screening their opponent’s double-pivot, blocking the passing lane into the duo by standing in front of the passing lane. Everton manager Sean Dyche labels this as being ‘north side’ of your opponent, whereas being ‘south side’ would involve sitting behind your man.

Once the ball is with the backline, outside of the defensive block, there is no danger and so this is an optimal position for Südtirol when defending.

There is a little more leeway for pressing the centre-backs when the opponent is playing with a single pivot.

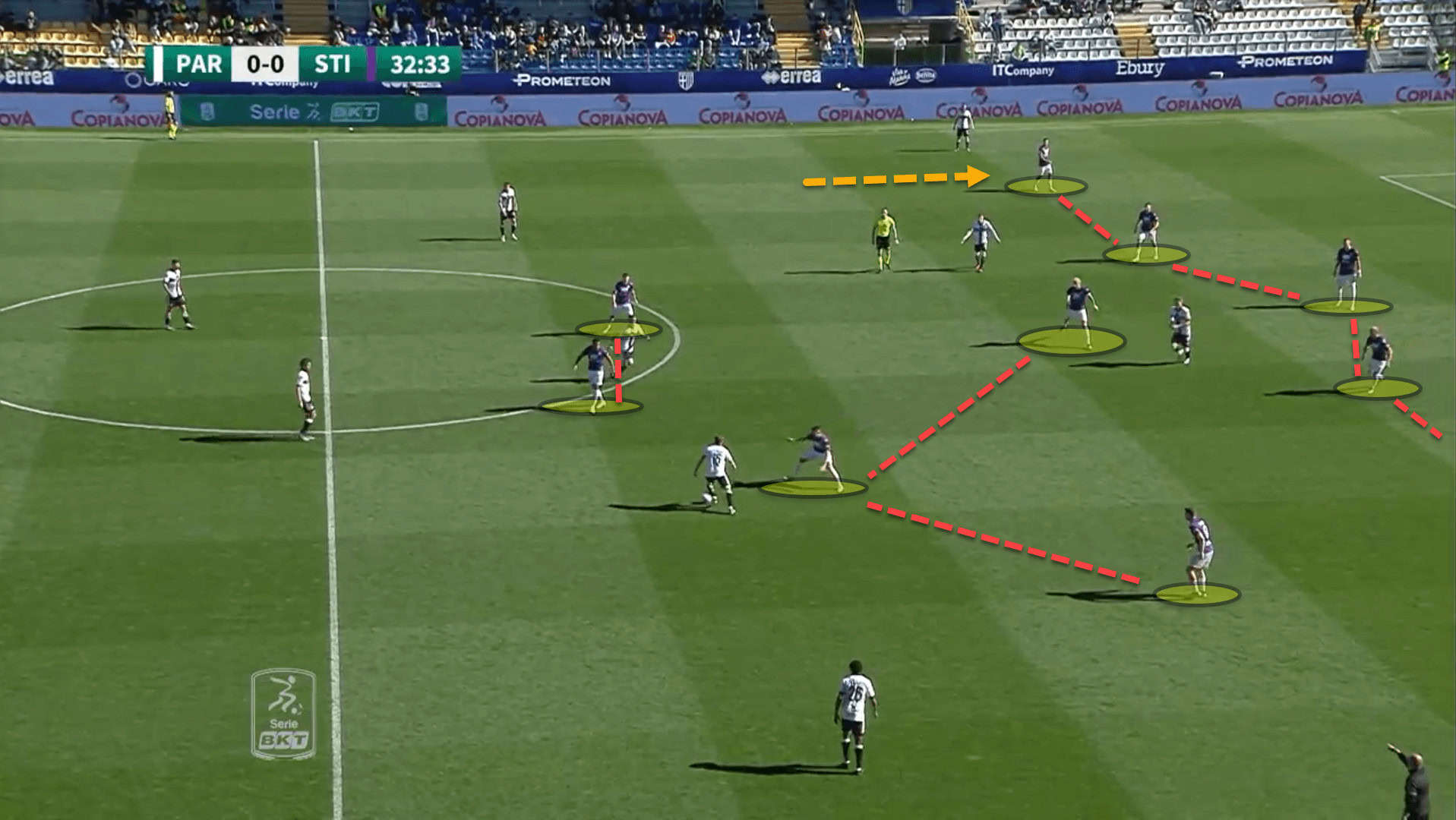

This a prime example of Südtirol’s set-up when the attacking side is playing with three men in midfield with one sitting at the base, whether it be a 4-3-3 or a 3-1-4-2 for instance.

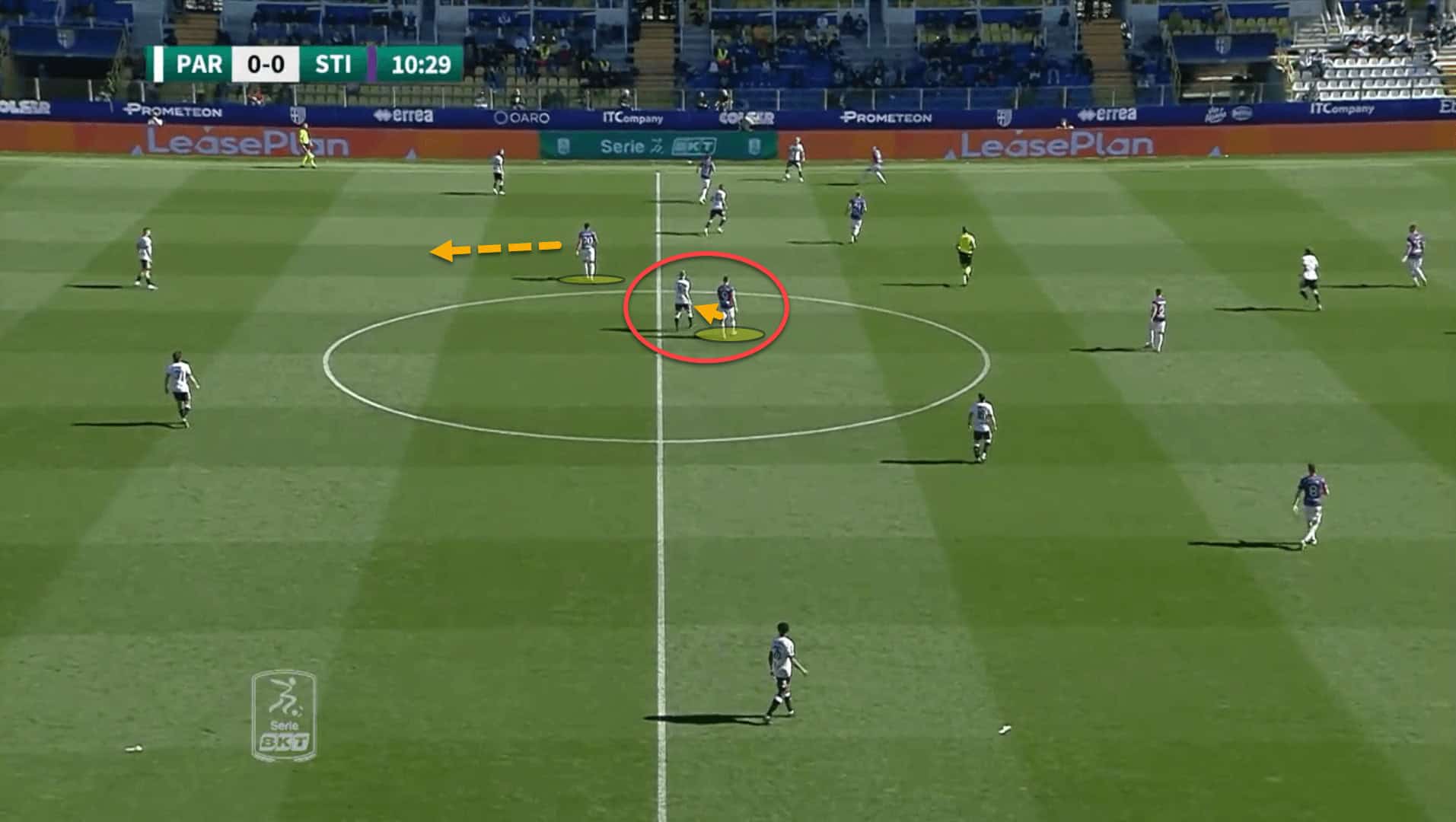

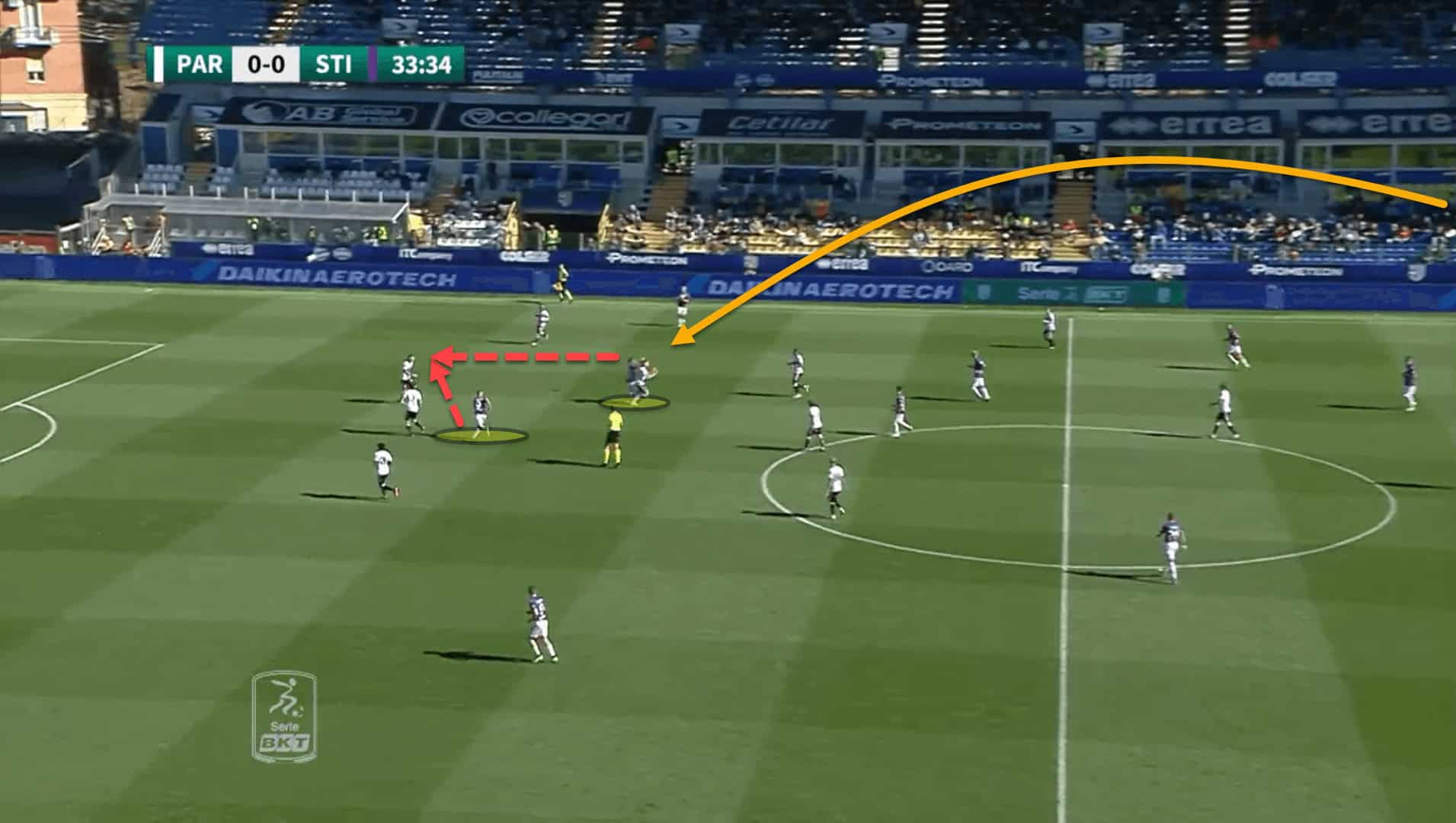

Parma’s formation is a 4-3-3, using a single pivot to receive in front of the centre-backs. In these cases, Bisoli instructs one striker to sit on the ‘6’ while the other positions himself a little further forward, ready to press the centre-backs.

When the attacking side progress further up the pitch and look to reach the final third, Südtirol’s shape moves from a 4-4-2 into a 5-3-2. This is done by having the furthest winger from play drop back, particularly if the opponent’s wingback/fullback advances. The reason Bisoli does this is so that Südtirol can be protected if the offensive side switches the play over in this direction as the Serie C champions can stretch the block horizontally.

The block still maintains its compactness between the lines, but it doesn’t need to be as narrow anymore since the winger has provided an extra man at the back.

For instance, here, Südtirol are still defending very compactly between the lines to ensure that Parma cannot reach their attacking players between the backline and midfield. However, the right winger has dropped back into the defence, causing the shape to switch from a 4-4-2 to a 5-3-2.

Because of this, the Biancorossi can defend the width of the pitch. If Parma switch the play to the far flank, the right winger will be there to cut it out.

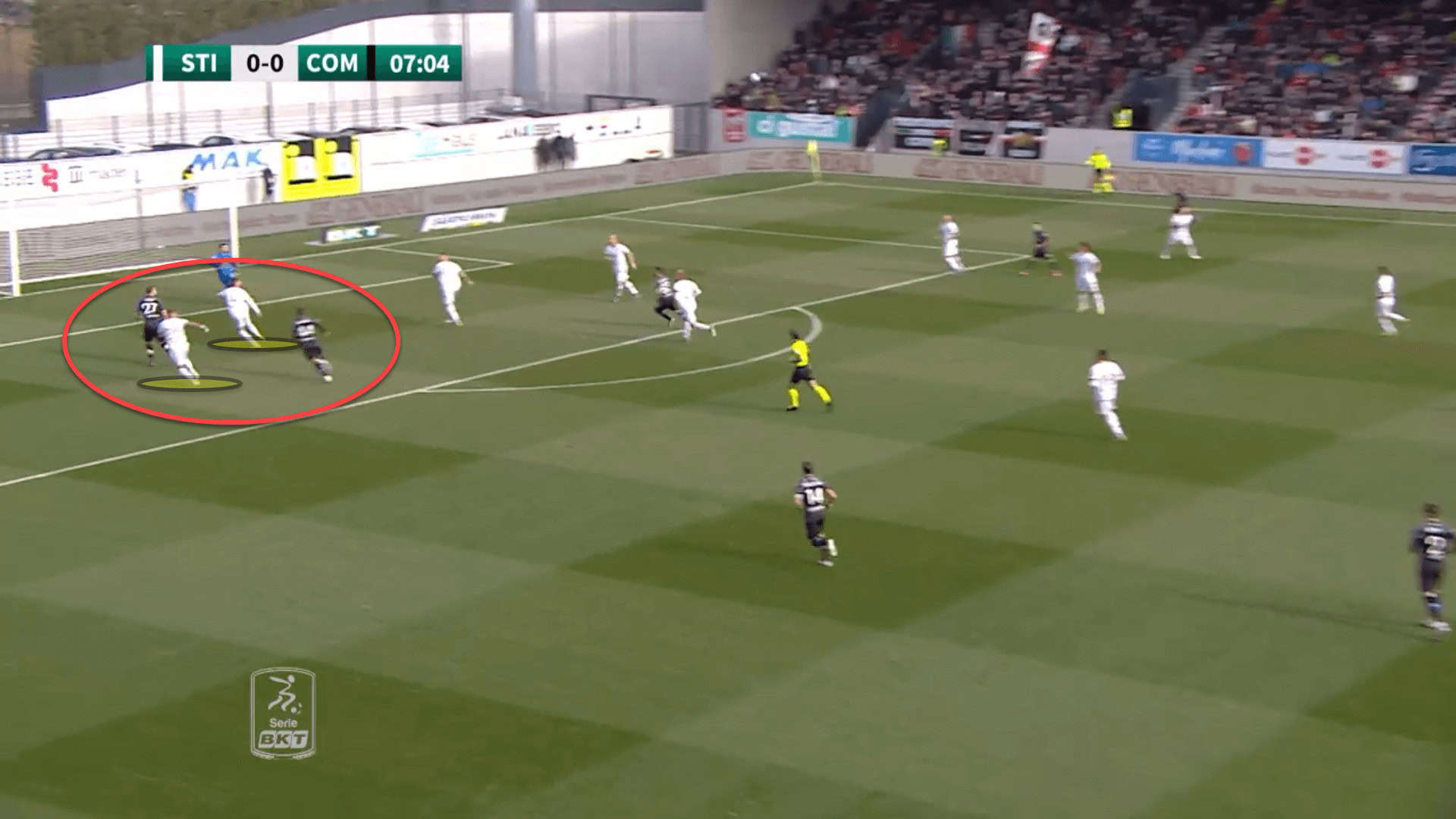

This is also really helpful when defending the back-post. Having this extra man in the defensive line means that the fullback cannot get doubled up on at the back stick.

Here, a cross has come in from Como, but the right-winger is alongside the left-back to create a 2v2 situation inside the penalty area, allowing Südtirol to deal with the danger and head it out for a corner.

Südtirol’s defensive set-up isn’t innovative, but it doesn’t need to be. It’s effective and that’s all that matters. Bisoli’s side are incredibly passive too, registering the highest Passes allowed Per Defensive Action (PPDA) in the league at 15.11 and the lowest challenge intensity at 5; the latter measures how many defensive actions a team makes per minute of opposition possession.

Essentially, Südtirol allow their opponents to play lots of passes and don’t really do anything about it because most of the passes are not in dangerous areas of the pitch.

And this defensive setup has worked wonders too. So far this season, Südtirol have conceded 0.89 goals per 90 and 28 goals overall, which is the fourth-best defensive record in Serie B for the fourth-placed team. Coincidentally, or perhaps not, only Frosinone, Genoa and Bari have conceded fewer, all of whom are sitting above Südtirol. On top of this, 21% of their goals conceded have been outside the area.

It may not be pretty, but Südtirol are incredibly dogged out of possession and this approach has meant Bisoli’s men are sitting pretty near the top, scoring more than they give away.

An ode to Charles Reep

For those who don’t know Charles Reep, he has been labelled as the first-ever statistician in football and is quite possibly the most notorious man in English football history that you may not have heard of.

For many, Reep is the father of the long ball, having discovered through intense statistical research that most goals were scored from three passes or fewer and that roughly just under 80% of all goals were scored from three passes or less. His research also concluded that 1% of all goals were scored from six or more passes. Reep argued that, in theory, the quicker the passes and the fewer the passes, the higher the probability of scoring was.

This has been highly criticised since, particularly by Jonathan Wilson, author of ‘Inverting the Pyramid’ and so his findings were certainly contentious. Nevertheless, these findings, whether accurate or not, shaped the way football in England was played for decades.

While Italian football was not directly affected by the work of Reep, Südtirol do feel like somewhat of an ode to Charles. Reep would be very proud of the club from Bolzano.

This season, Südtirol have averaged 2.8 passes per possession which is the lowest in Serie B. Bisoli’s side have also averaged 49.27 long balls per 90 which is the fourth-highest in Serie B. Considering the team average just about 38% possession per game, this is quite astonishing. In fact, 19% of Südtirol’s passes this season have been long passes which is roughly one in five.

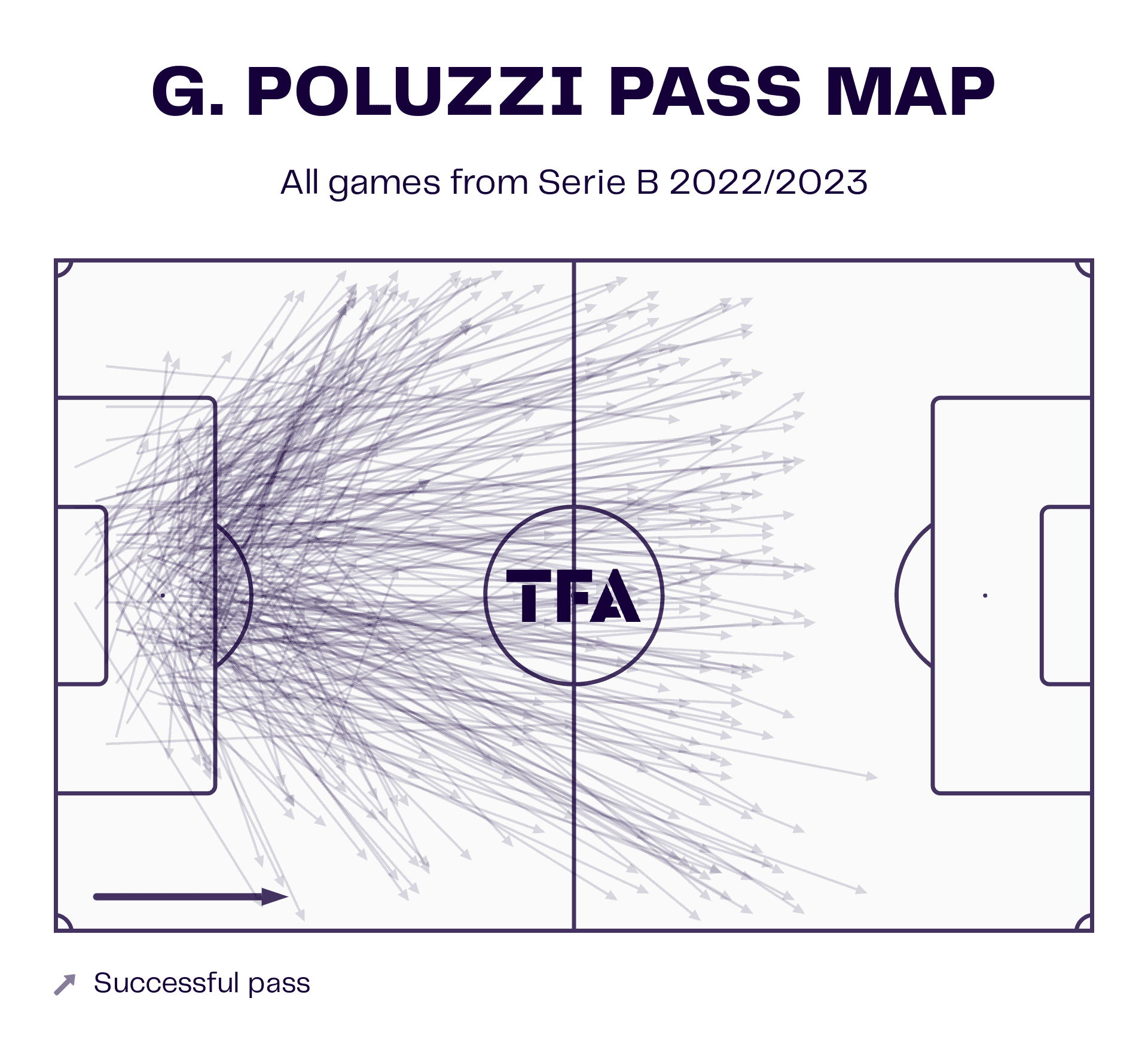

There is no playing out from the back in Bisoli’s system. The goalkeeper is tasked with pumping it long to the forward line.

From goalkeeper Giacomo Poluzzi’s pass map this season, it is evident what the instructions from the sideline are. The vast majority of Poluzzi’s passes are either switches of play to the fullbacks or long passes up the pitch, predominantly past the halfway line.

When the keeper pumps it up the pitch, the rest of the team squeezes together and pushes up to try and sustain possession in the opposition’s half.

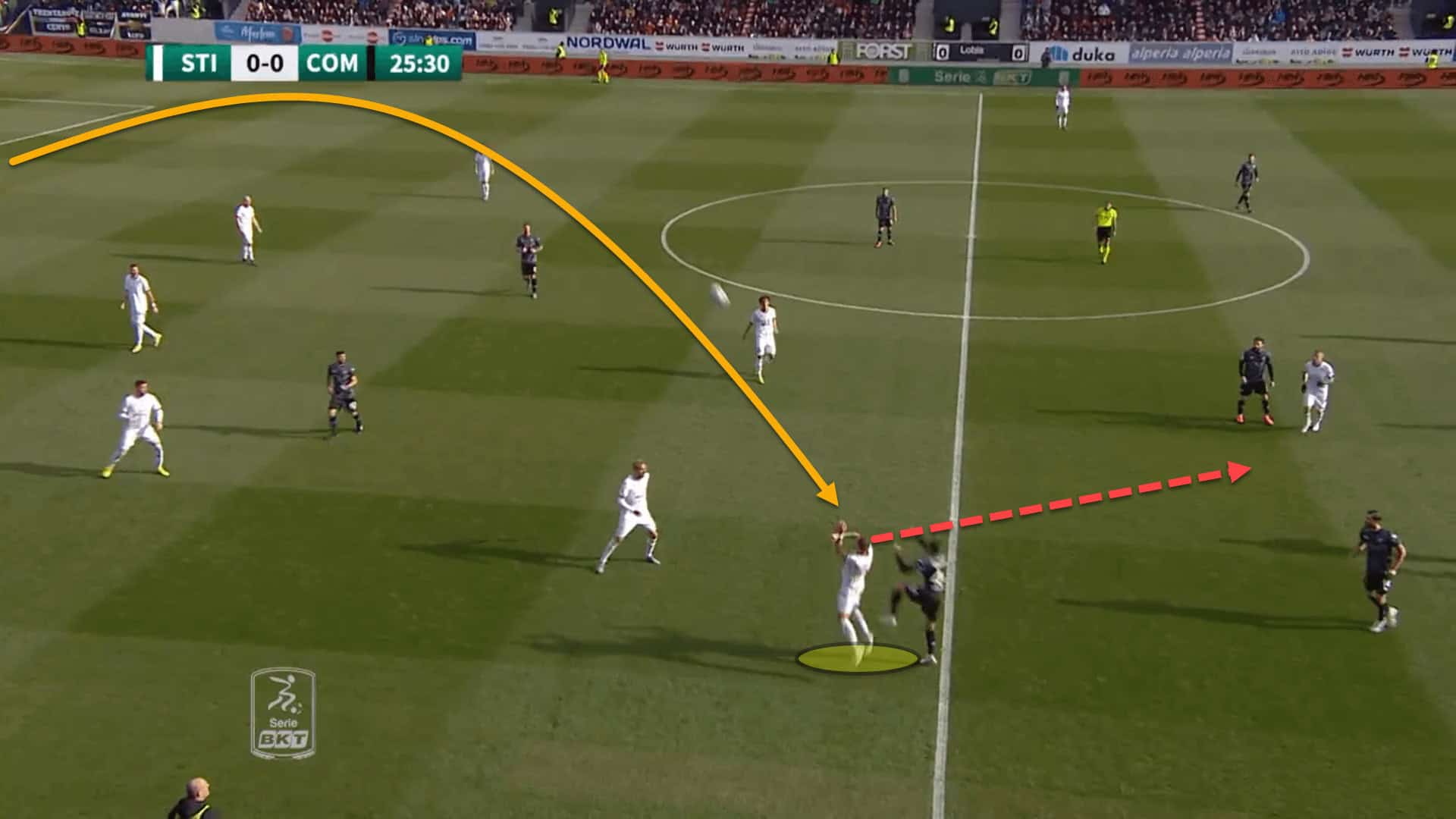

The targets from these long balls from goal-kicks are usually the wingers who back into the opposition’s fullback/wingback, hence why so many of Poluzzi’s passes are high and wide. The reason they do this is that centre-backs are normally excellent in the air, as is a prerequisite for being a central defender.

Here, the long ball from the keeper has been aimed toward Südtirol’s right winger, forcing the Como wingback to engage in an aerial duel where he isn’t as comfortable. The winger wins the header and the Biancorossi were able to start their attack inside the opposition’s half.

Nevertheless, when Südtirol have possession around the backline, the aim is to play to the centre-forwards who run off one another in a typical strike partnership manner — one challenges for the ball while the other runs in behind, attacking the depth and anticipating the flick-on.

There is no dilly-dallying at the back. Bisoli wants his defenders to get the ball out of their feet and aim for the strikers who can try and create a chance high up the pitch using flick-ons which is such a simplistic method of attacking but can be effective when properly trained and once the centre-forwards have an understanding with each other.

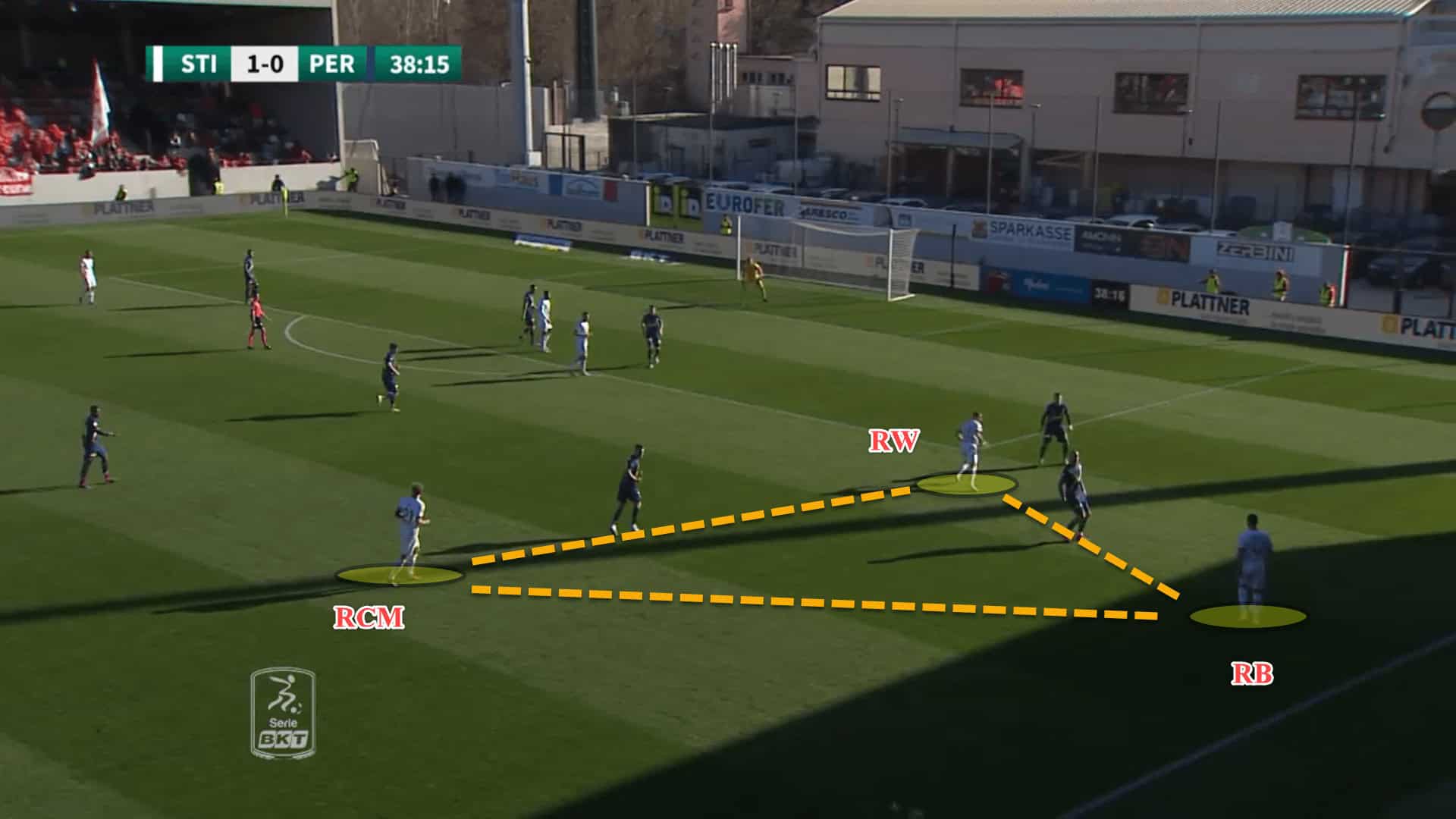

However, there are times when attacking the box as quickly as possible with long balls may not be a viable solution and so Südtirol must try and work an opportunity inside the penalty area. They do so by creating triangles out wide with the fullback, winger and nearest central midfielder. One stays wide, one pushes into the halfspace while the other sits at the base of the triangle to offer a deeper passing option if they need to play backwards.

In this case, the fullback is wide on the right flank, the winger is inside in the halfspace while the nearest central midfielder is sitting at the base of the triangle. The order of their positioning is not fixed once the triangle remains intact.

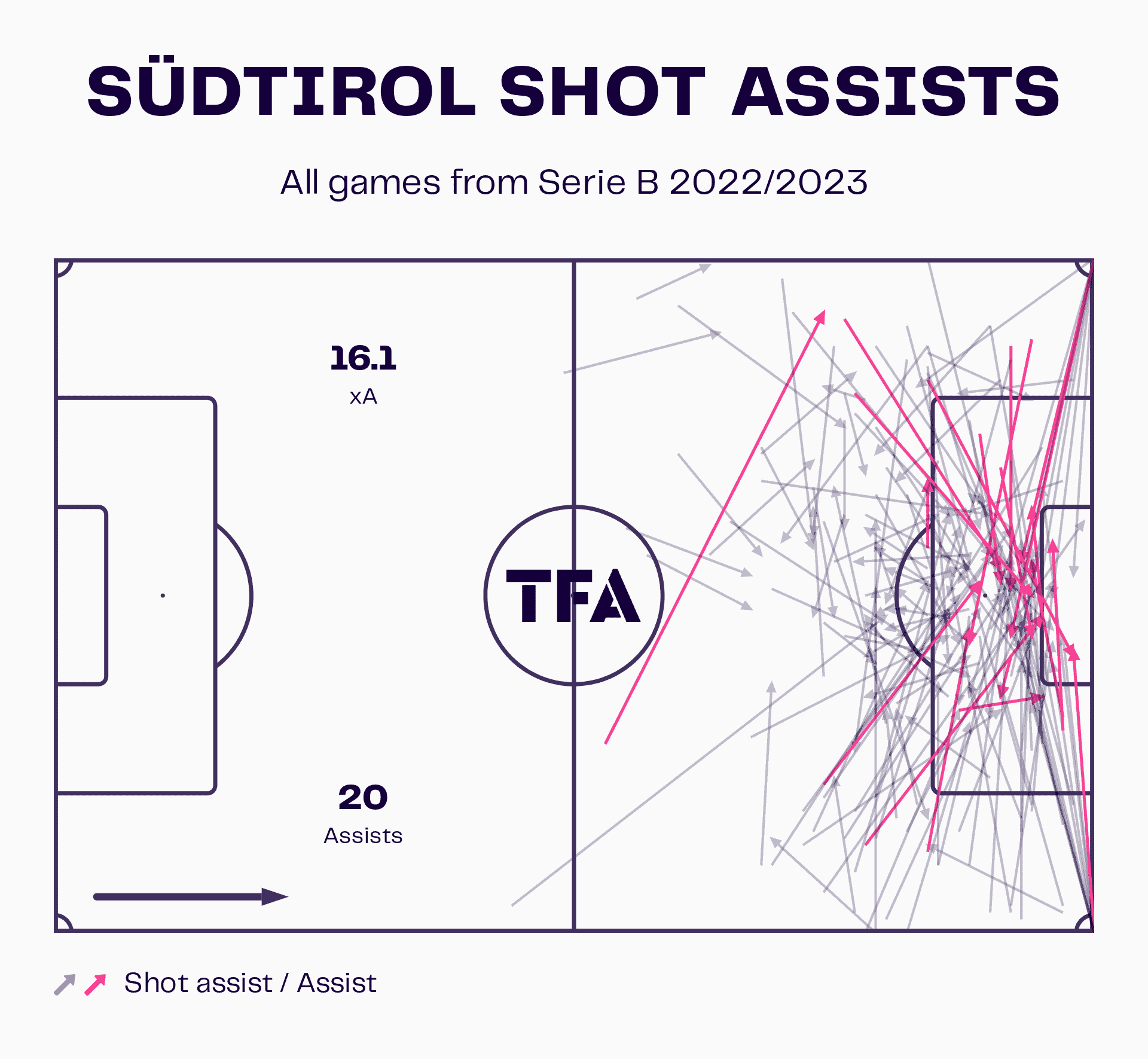

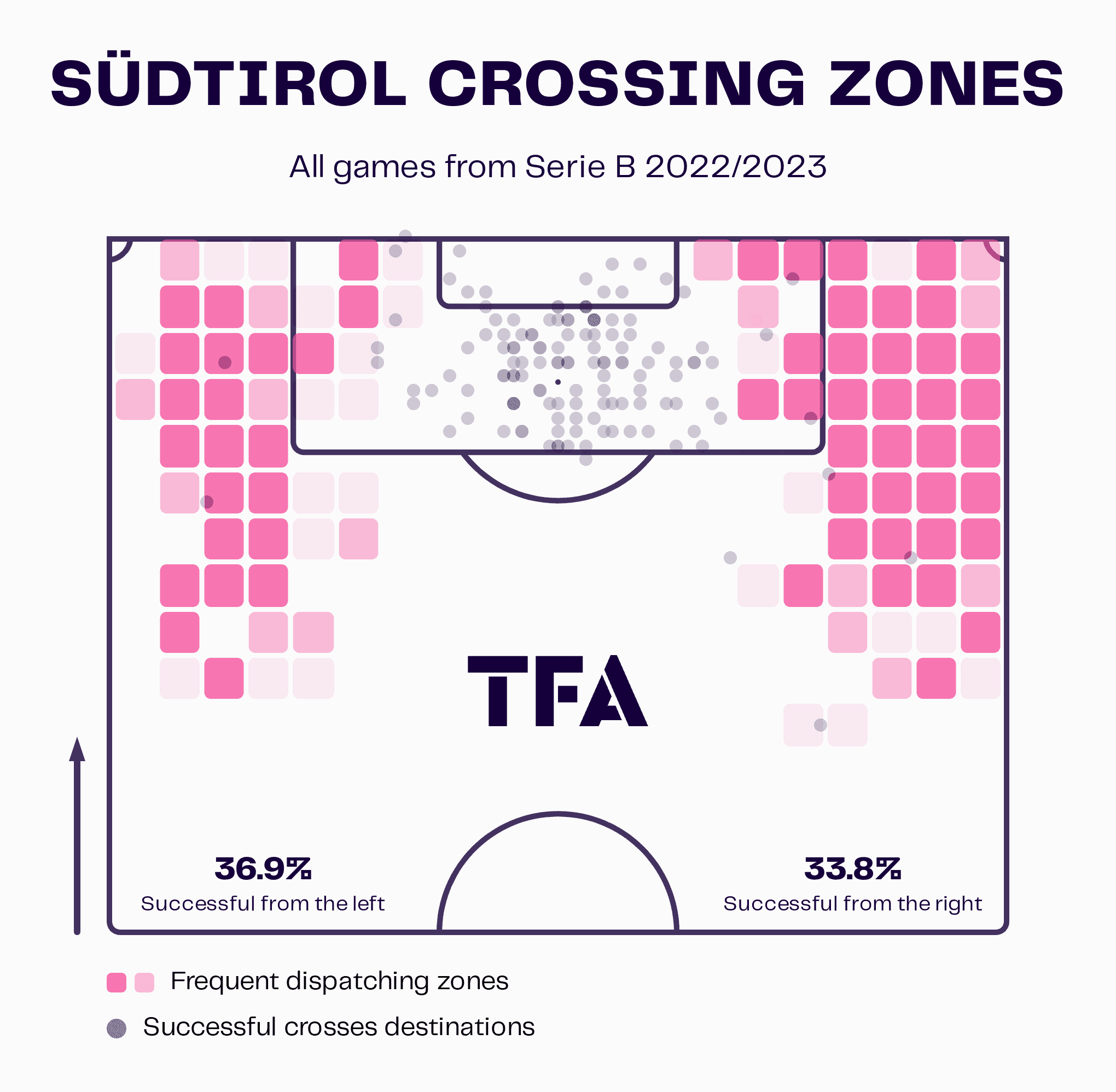

Crossing is a big part of Südtirol’s style. Whether the crosses are from near the touchline or the byline, it doesn’t really matter.

As can be seen from Südtirol’s shot assists map this season, so many chances are created from the wide areas, whether it be from corner kicks or crosses from open play.

What’s also evident is that the side are outperforming their expected assists of 16.1, meaning the team have been converting quite a lot of their chances, even if the delivery hasn’t always been spot on.

A higher volume of crosses are played from Südtirol’s right-hand side, but they are actually more impactful from the left with a higher success rate on the latter flank. Perhaps Bisoli may lean more heavily on the left flank for the remainder of the campaign. But right now, no side have scored goals from headers than Südtirol in Serie B with 11.

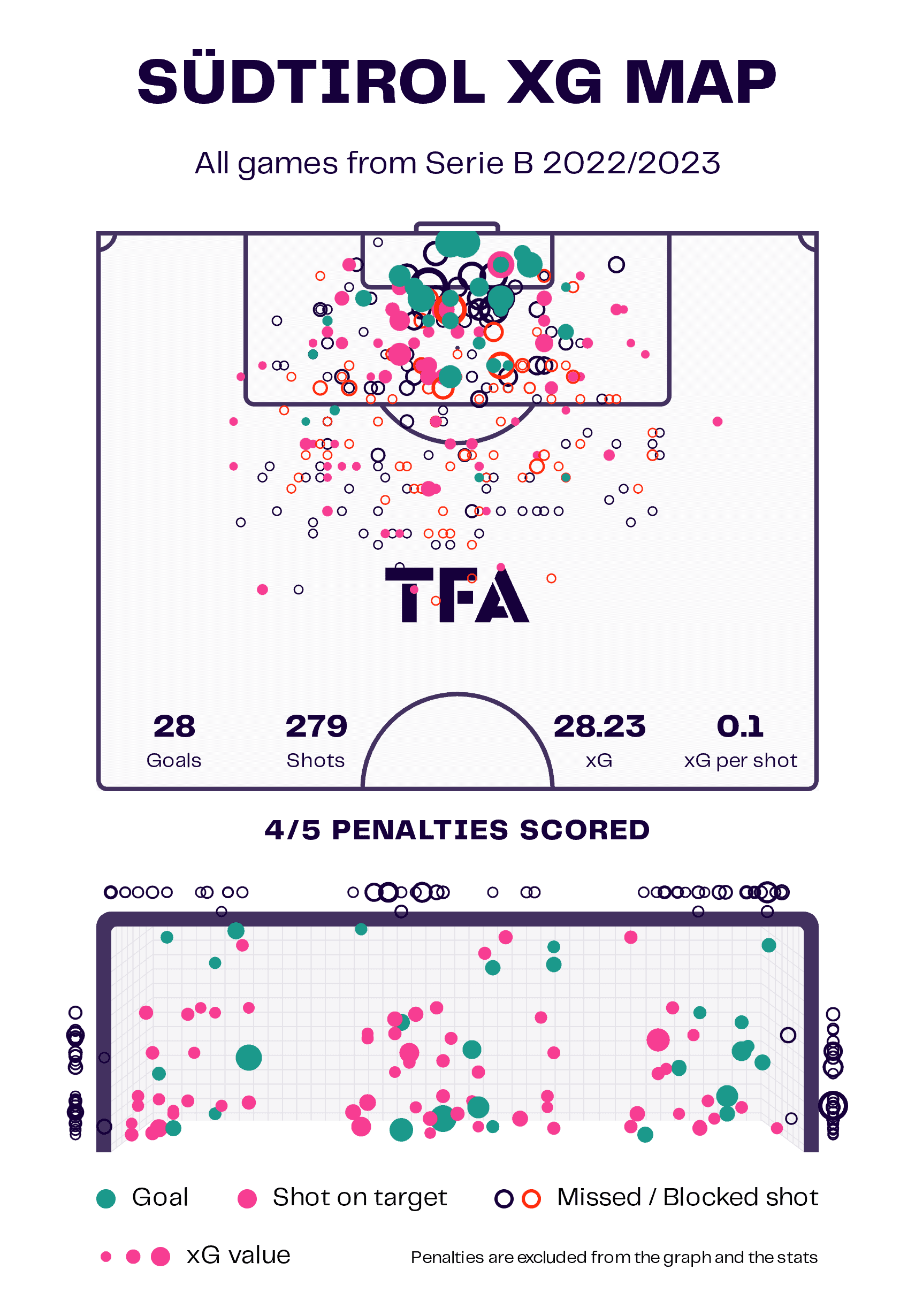

Scoring the chances hasn’t been a problem for Südtirol either. The Biancorossi have registered a non-penalty xG of 28.23 this season in Serie B, scoring 28 times.

Bisoli’s men are the tenth-lowest (or tenth-highest) scorers in the league as of writing which isn’t ideal. However, the team’s excellent defensive record has meant that this hasn’t really been a problem, although if the backline begin to leak goals, this will certainly be a glaring issue.

Let’s go back to the wide triangles for a moment. The deepest player in the triangle is not only there to offer a deeper passing option if possession needs to be recycled. Their role is also to immediately step up to counterpress in case the ball is turned over.

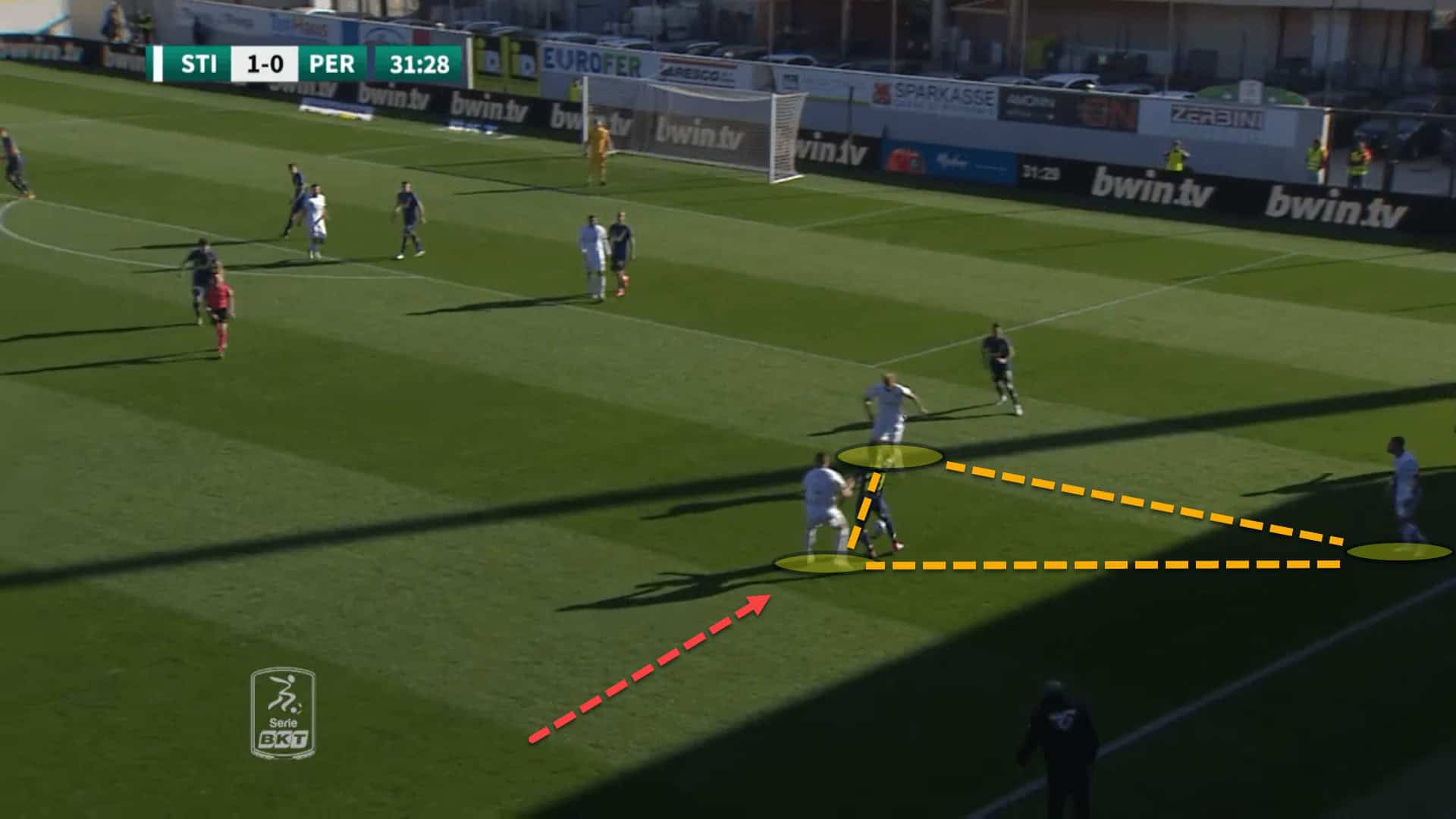

Here, the right-back was the deepest player in the triangle. Once Perugia regained possession, he instantly stepped forward instead of dropping back to his own goal and applied pressure to the ball-receiver from behind.

This triangle offers some defensive security during defensive transitions high up the pitch to stop counterattacks at their source which is why Bisoli is so adamant that his players keep this mini-structure stable when going forward on the flanks.

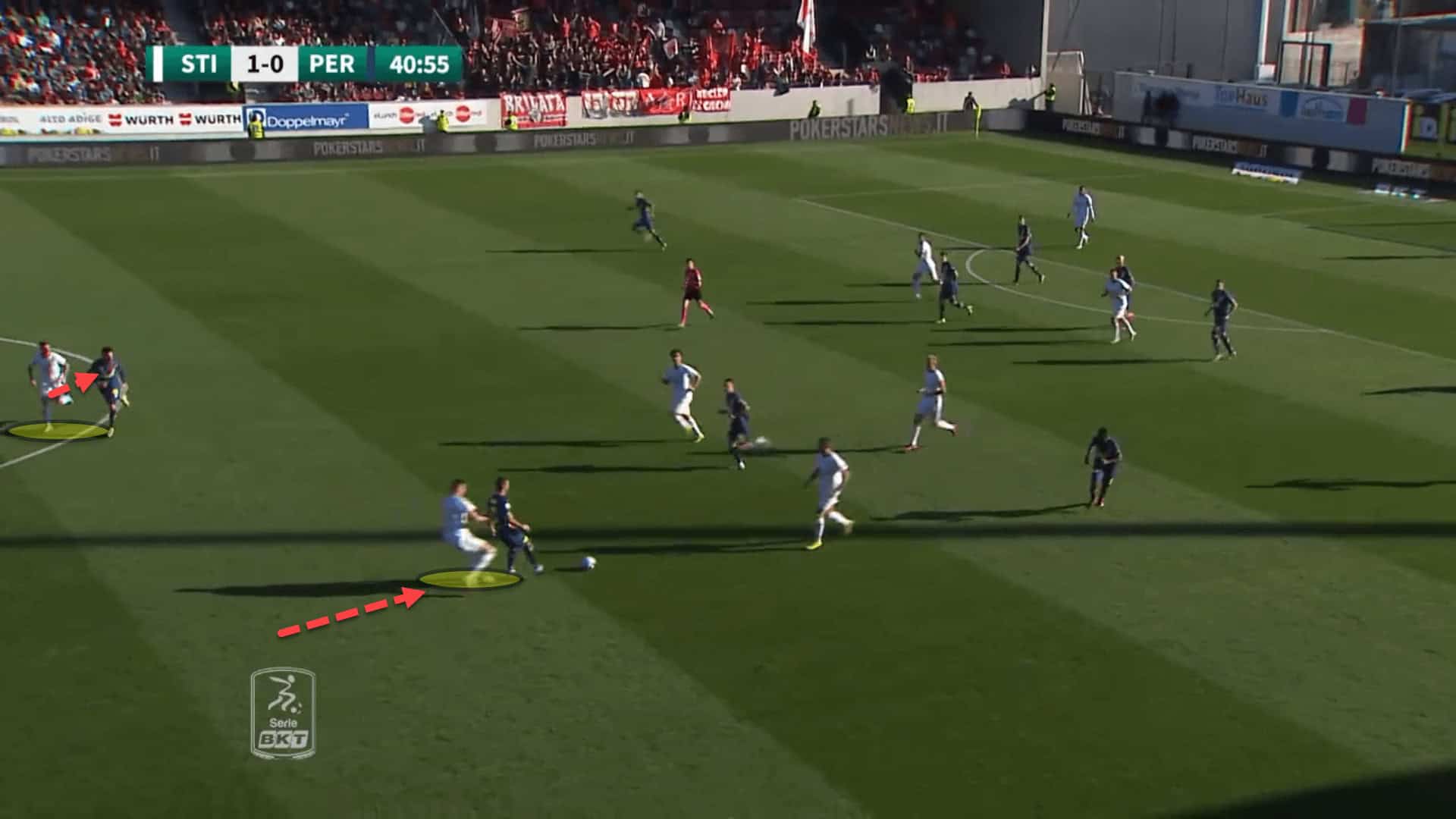

While many may have the impression by now that Südtirol are quite a conservative side, which they are, the head coach is still keen for his players to try and nullify counterattacks as far away from their own goal as possible. Behind the wide triangle, the centre-backs also step up and get tight to the opposition’s centre-forwards to stop them from turning and driving forward instead of running back to their own penalty area.

Here, the right centre-back has jumped forward to the opposition’s striker to prevent the counterattack, being aggressive in his duel to either win the ball or stop the break by fouling his man.

There is an air of old-school, Catenaccio Calcio about Südtirol under Pierpaolo Bisoli but it’s masked behind a fog of modern principles such as having a solid rest defence structure and counterpressing, as this team scout report has hopefully showed.

Conclusion

Modern Catenaccio is perhaps the best way to describe Südtirol’s style of play this season. Bisoli believes in having a solid defence first and foremost. As a result, attacks are few and far between, but when they arise, Südtirol can take their chances.

The Biancorossi are a perfect example of pragmatism at its very peak — a team with limited resources and finite technical quality capable of punching well above their means by playing a style of play that suits the players at the manager’s disposal.

They currently have the oldest squad in Serie B and so don’t possess a lot of speed, hence why the block is positioned so low down the pitch and why they rely on crosses instead of rapid attacks in behind. But it’s working.

The style suits the players and Bisoli is doing a tremendous job playing in a manner that many wouldn’t dare to try in the age of ‘perfect football’.

Playing in Serie A has been nothing but an impossible dream throughout the club’s history but right now, this dream is becoming more and more real. Nothing is impossible in this beautiful sport.

Comments