In last month’s Total Football Analysis Magazine, Domagoj Kostanjsak wrote a brilliant analysis entitled, Tactical Theory: Space occupation & creation. If you haven’t read it yet, I certainly recommend you do so as it’s the inspiration for this article.

Kostanjsak’s tactical analysis develops some of the most important concepts at the meta-level. It’s a must-read for any football coach or tactics fan. If you read that article, you’ll find that much of the game comes down to the concepts of space and time. Often it’s the teams that are better at creating and occupying space that win matches, be it from an attacking or defensive standpoint. Spatial orientation has a direct relationship to time on the ball, which gives the team on the ball more options in attack.

For possession dominant teams, creating time and space to conduct attacks is often countered by defensively compact opponents. In order to create more time and space on the ball, teams look to create superiorities across the pitch.

This article looks at both the theoretical concepts and practical applications of superiorities. Working through the superiorities, this tactical analysis will frame them within a concrete situation with training activities to help players understand what superiorities are and how to construct them in the flow of the match. When building sessions, it’s important to begin with the end in mind. Rather than drawing up sessions at random, we, as coaches, want to identify the most important principles within our styles of play and our team’s tactics for upcoming matches, then design the session with those ideas and intentions in mind. We want to develop smarter players who are capable of assessing the game, offer a proactive approach and are mentally alert as they seek solutions to the game’s problems. An awareness of superiorities through the ecological dynamics and constraints presented in our sessions can achieve those ends.

What are superiorities?

Depending on your influence, you’ll either argue there are four or five superiorities in football. In this article, we will assume the four superiorities put forth by Professor Francisco Seirul·lo: 1) numerical (“there are more of us”), 2) qualitative (“we are better”), 3) socio-affective (“we understand each other better”) and 4) positional (“we are better positioned”). The quotations are included because they offer the clearest means of communicating superiorities to our players, especially in the youth game.

Professor Seirul·lo speaks of two types of spaces, the first of which is an intervention space, which is the space where a player carries out an action against an opponent, and a space phase, which is how the space away from the ball is occupied by teammates. Therefore, when we speak of superiorities, we are addressing how a team creates advantages within the space phase.

The match tactics players learn come through preferential simulation situations, which is a way of constructing exercises through global tasks within open play. These actions are perfectly carried out within a group, be it small-sided or a larger scale, with constraints within the exercise to produce the desired learning experience.

As we build through the four superiorities, I will present them within the attacking phases of play. We’ll start off with the one that’s most easily understood, even by young children, numerical superiority.

Numerical superiorities – “There are more of us”

In a recent 2v2 game my 5-year-old son and I played against his two older cousins. My audacious kid, who is very confident in his ability on the ball, was growing frustrated that he kept losing the ball when he attacked his two cousins in 1v2 scenarios.

I asked him, “How many of them did you dribble into?”

“Two,” he said.

“So there were more of them than you, ” I asked him.

“Yes,” he said.

“Do you think it’s easier to beat both of them or just one?” I asked.

“One.”

“Why?”

That’s when the light bulb turned on: “because it’s easier to beat one person than two,” he said.

From that moment on, he engaged 1v1, numerical equality and released the ball when 1v2.

Simple, right?

It is, and, as I said, numerical superiority is the easiest to understand. Even a 5-year-old can see that having equal or greater numbers than the opponents is preferable to playing numbers down. More importantly, he can understand it epistemologically by synthesizing his experience. That knowledge then forms his understanding of the game, shaping his approach and the way he processes sensory data.

Moving these ideas into the team concept, we can see a clear application for establishing numerical superiorities in the way we initiate our attacks. As we build-out of the back, the objective is to use a numerical superiority deep in our end of the pitch to draw the opposition, inviting them to press and become unbalanced. As their defensive structure deteriorates, gaps for progression appear on both the horizontal and vertical axis.

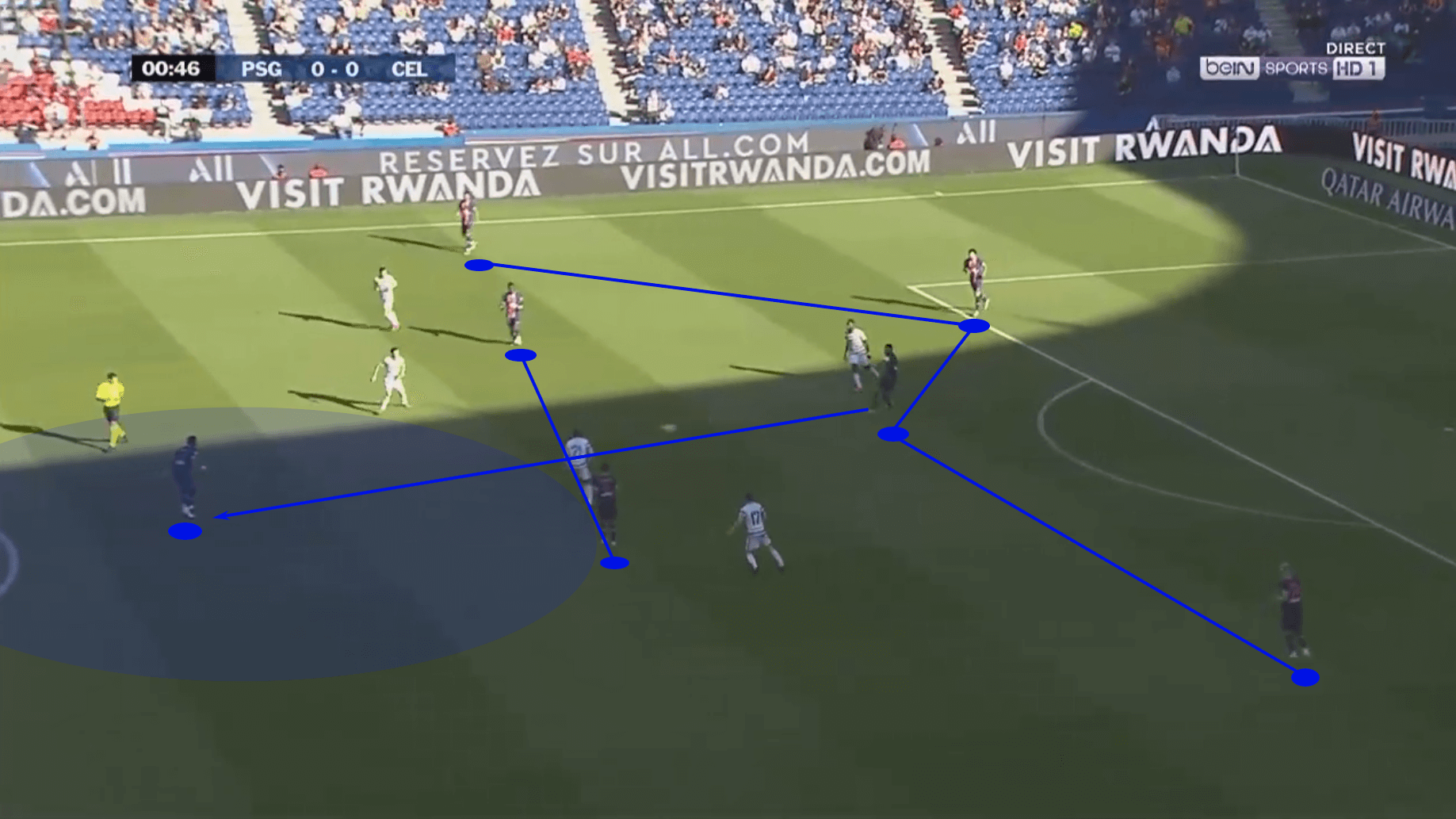

Taking an example from PSG, we find seven players in front of a line of four opponents. In total, PSG has seven players engaged in the build-out with Neymar situating himself between the lines. Meanwhile, their opponent has five players in the same area.

One of the reasons for a numerical overload is drawing as many of the opponents as possible, but another reason, which is far more simple, is simply for the sake of securing possession. Numerical overloads should lead to fewer losses and more effective defensive transitions as players have less distance to cover and they can effectively close more passing lanes within a shorter time.

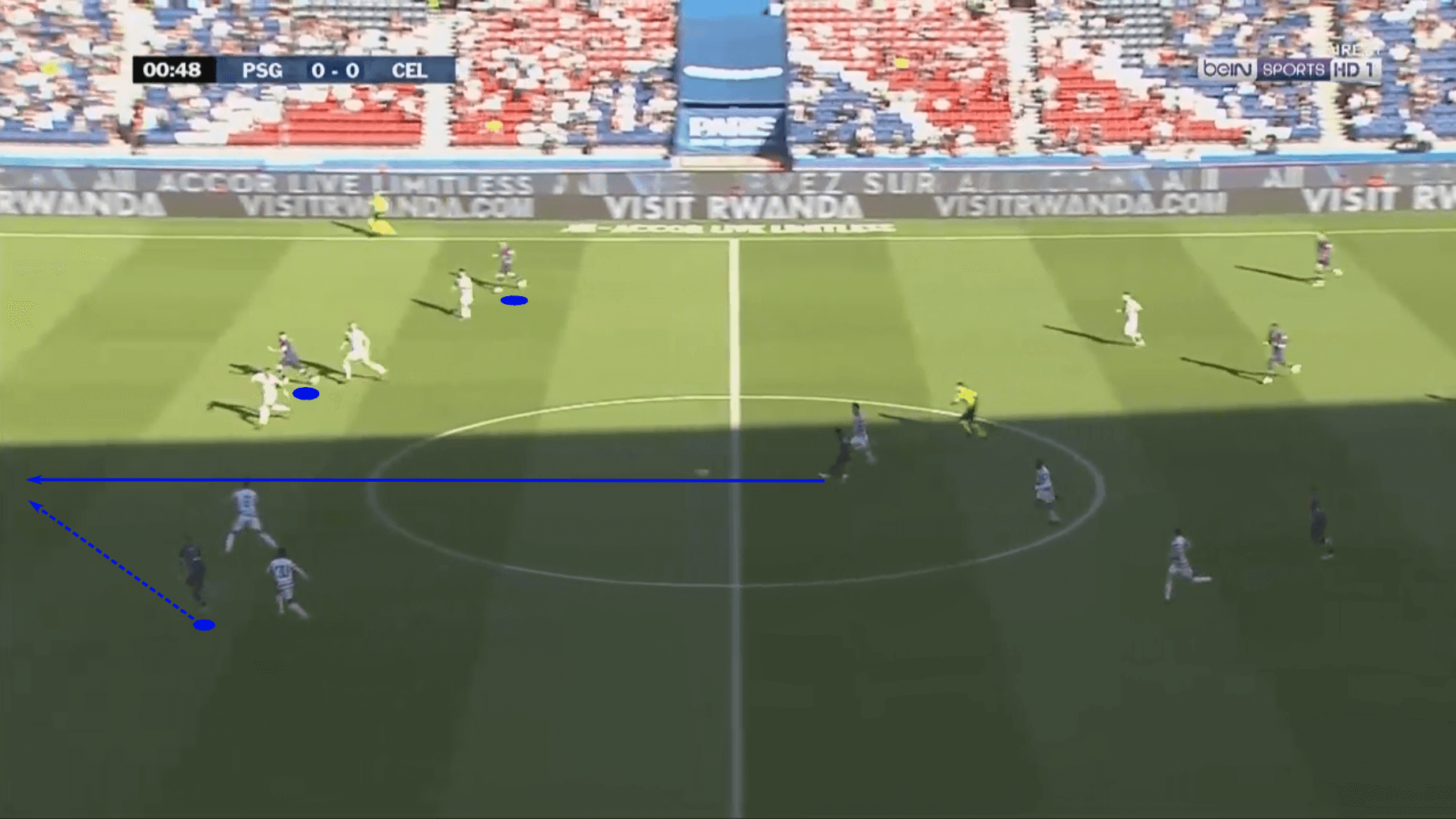

In the PSG example, once they unbalanced their opponent, it was time to transition from “preparing to attack the opponents” to “attacking the opponents.” The ball is played into Neymar, who takes it on the half-turn. PSG occupies the line of five defenders with three forwards, but you can see two of the three are offset to the right, leaving a large gap right through the middle for Kylian Mbappé to sprint into, leading to a PSG goal. The numerical overload unbalanced the opponent along the vertical axis, allowing PSG to conduct a direct attack through Neymar’s positioning between the lines.

If you studied those first two pictures closely, you likely noticed that there were additional superiorities in play, such as a qualitative superiority for Mbappé over his defenders, a socio-affective superiority between Mbappé and Neymar and even a positional superiority in that Mbappé was in full flight before the centre back took his first stride (as well as Neymar’s positioning between the lines).

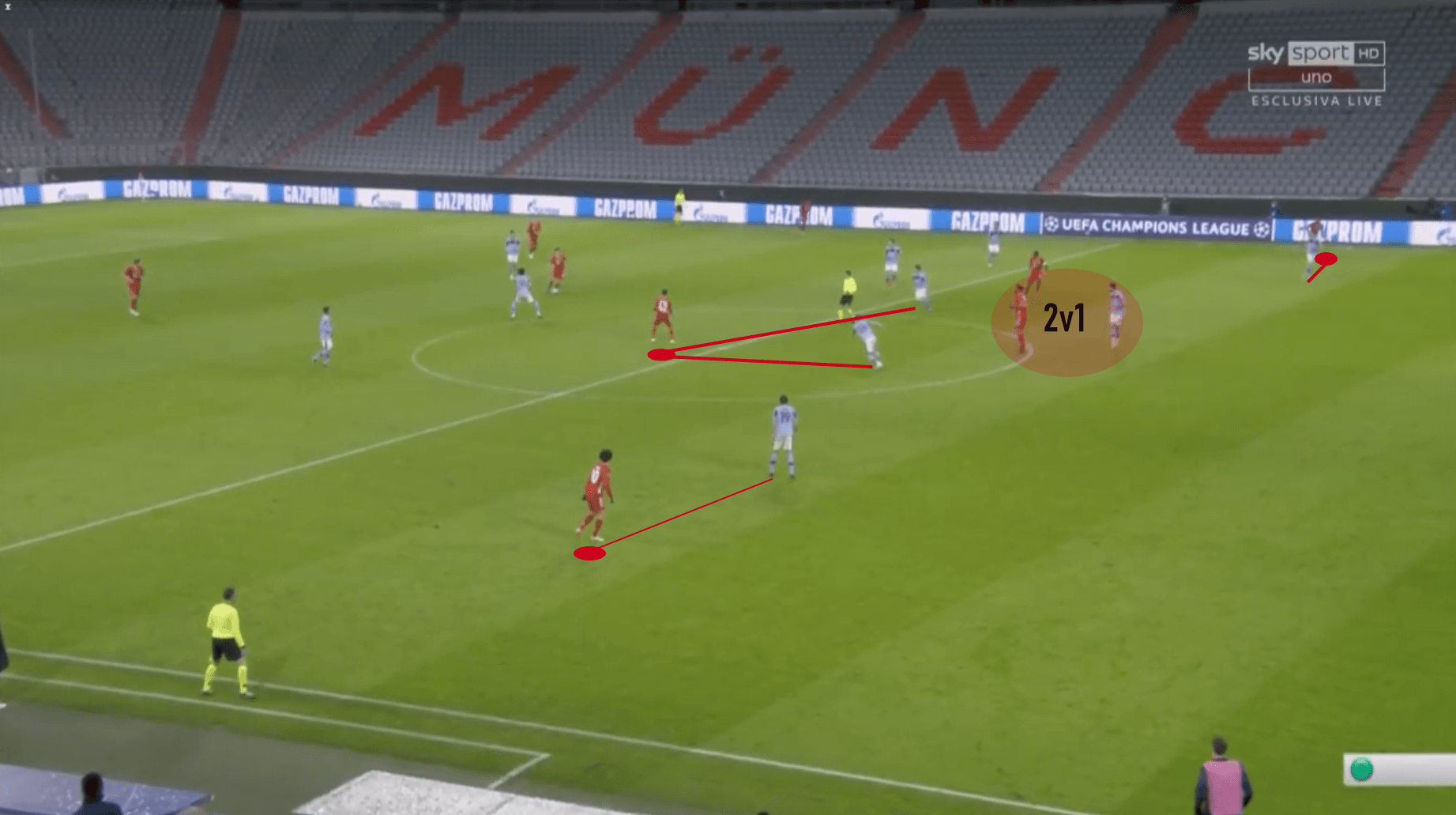

Multiple superiorities can be in place at the same time, though in different respects. The next example comes from Bayern Munich as they connect the lines. Again, look closely and you’ll find multiple superiorities in place.

Continuing with numerical superiorities, we find Bayern up against Lazio’s middle block. Though the Italians are reasonably compact, they leave too much space in the middle of the pitch. It’s a mistake two players quickly recognize and look to rectify. However, as both commit to the open player, a 2v1 emerges against their right centreback.

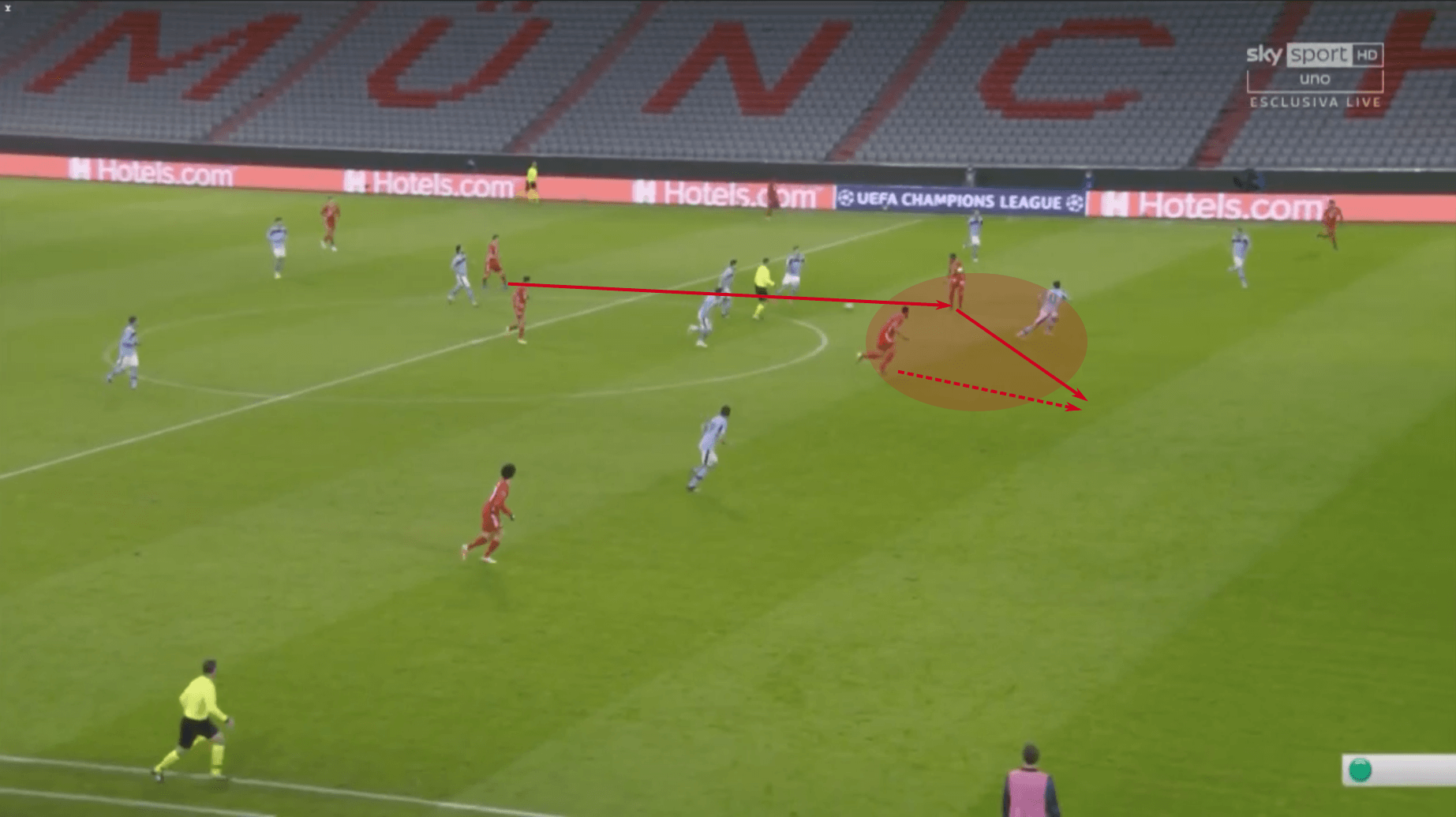

The red lines from the first image of the sequence indicate player occupations. The two wide forwards occupy the two outside-backs while the central midfielder has commanded the attention of two Lazio players. Through his positioning, he’s pulled out one of the two centre-backs, giving Bayern Munich a 2v1 in a far more dangerous area.

Bayern is quick to pounce on the mistake, playing into their numeric superiority and using the 2v1 to play Eric Maxim Choupo-Moting through to goal.

Knowing that even young children can understand numerical equality, superiorities and deficiencies, this is a concept that we can teach players of all ages. Identifying and exploiting numerical superiorities is one of the quickest ways for a player to improve. Let’s move on to the practical application.

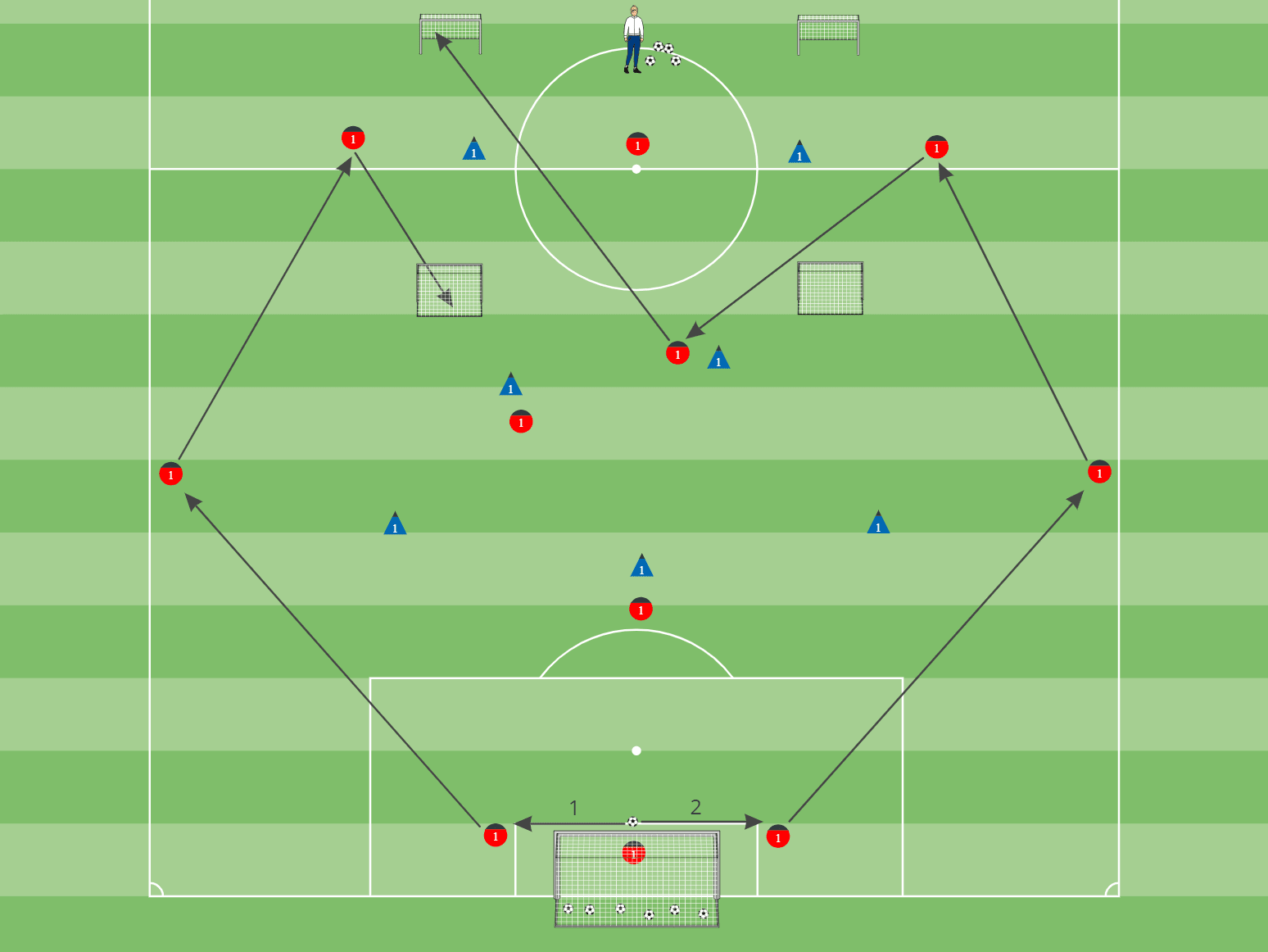

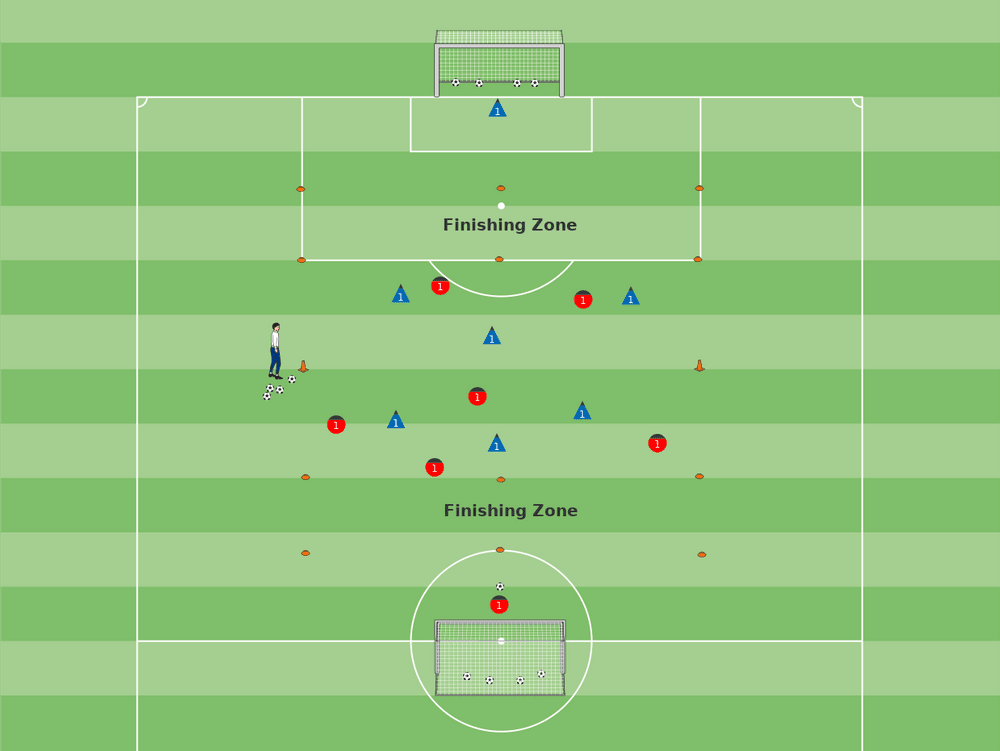

Exercise 1 – Generating numerical superiorities

Organization

– Half field exercise. Give an additional ten meters for the endzone.

– 8v5 in the main playing area with 3v2 in the endzone.

– When possible, feature goalkeepers in regulation-sized goals.

– Two mini-goals 10 meters from midfield on either side. The two goals in the defensive half are for the first game, whereas the two goals in the attacking half are for the progression.

Gameplay

The eight attackers (in red) must build-out of the back from a goal kick against five opposition defenders (in blue). In order for red to score, they must first play into any of the three target players on the other side of midfield. Only the three target players can score in the mini-goals. Meanwhile, blue tries to win possession and score in the full-sized goal. As a progression, reds play into the targets, who set into midfield, before the advancing red play into the mini-goals in the attacking half. Look for and praise the recognition and establishment of numerical superiorities. If the ball goes out of play, restart play from the keeper. Play four sets lasting 5 minutes with a two-minute recovery.

Coaching points

– Correct body orientation to connect actions

– Expansive attacking shape with safe, deep options available

– Overload in one area of the pitch to unbalance the opposition

– Once opponents are unbalanced, find outlets and play out of press

– Forwards must work to find passing lanes that allow them to receive, then set

-Up and back pattern in the first exercise, up, back and through in the second

Qualitative superiorities – “We are better”

In theory, qualitative superiorities are easily understood as well. If one player, or a group of players, is consistently getting the better of another, the former has clear qualitative superiority.

The reason this can be tricky is that players, especially those with low self-awareness often overestimate their ability. At higher levels of play, concrete proof through data analysis is a nice way to help the players understand the quality they bring to the pitch. At lower levels of the game where data is not readily available, a simple set of statistics or a more psychological approach through a vote of confidence can help players grasp where they stand in relation to the opponent.

For many teams, the simplest form of qualitative superiority to seek is in 1v1 situations. If my one can consistently beat yours on the dribble, my player can then run at the second defender to disorganize your defence.

For possession dominant teams, especially at the highest levels of play or for lower-level teams that enjoy a significant percent of their possession inside the opposition’s half, there’s often a need to look beyond simple 1v1 qualitative superiorities, looking instead at small group advantages.

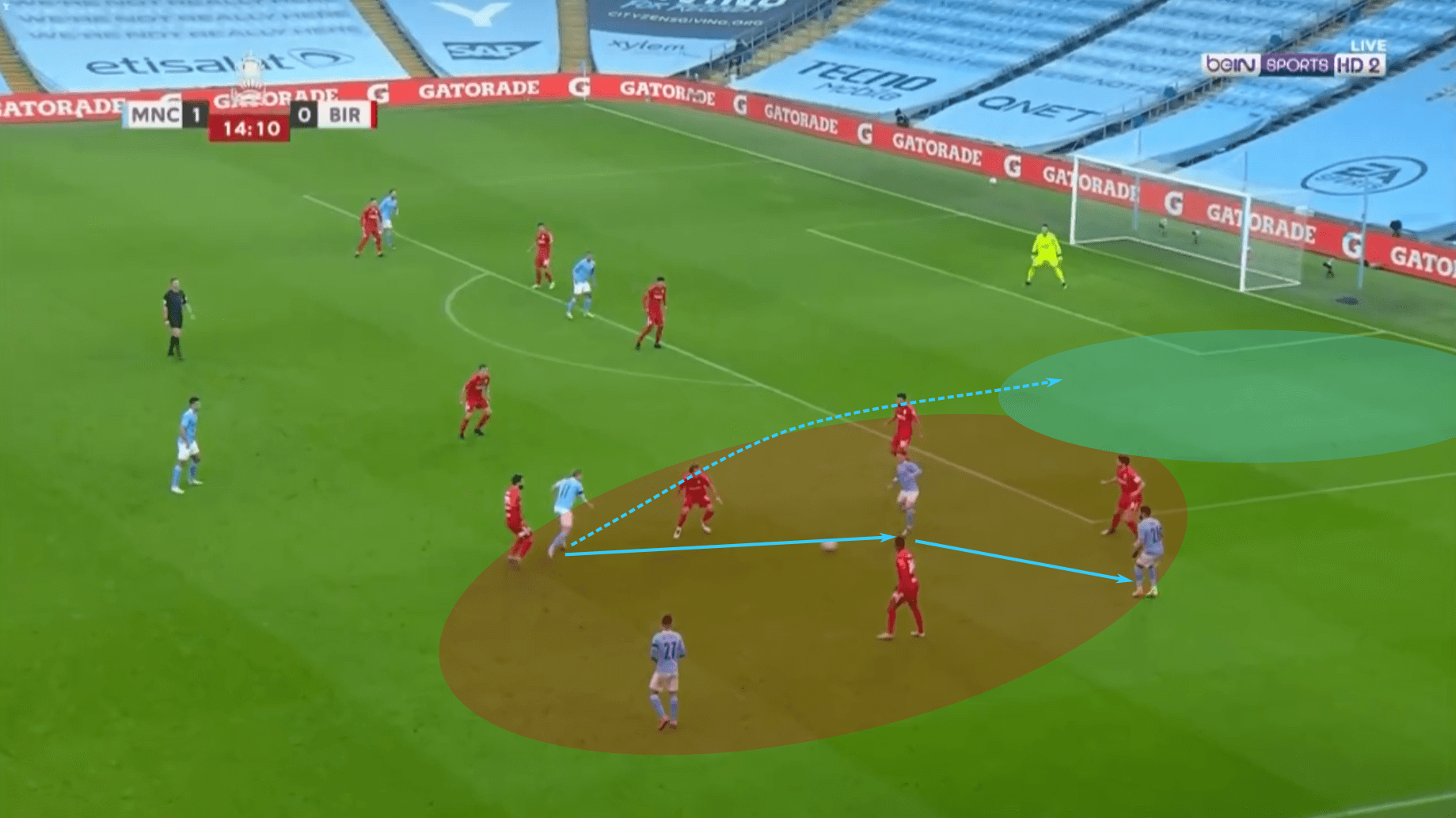

In the numerical superiority section, we looked at examples of teams building out of the back and connecting their lines. For our qualitative superiority, we’ll look at the final pass, and there’s perhaps no better team for this example than Manchester City.

Not only do City enjoy extreme possession percentages, but they also spend much of the game in the opposition’s half of the pitch against a low block. In order to access more dangerous areas of the pitch to generate scoring opportunities, they often look to break the low block through wide overloads with qualitative superiorities. They may not always enjoy a numerical advantage, but it’s rare that an opponent can match Manchester City’s creatives.

In this example, City is 4v5 in the red oval. They’ve overloaded near the ball in the right-wing and half-space, committing some of their most talented and creative players in that part of the pitch. Once the overload is complete, Kevin De Bruyne initiates the attack on the opposition. The simple sequence of passes puts a ball on the foot of İlkay Gündoğan. As the two passes are played, De Bruyne makes his run into the right half-space of the box.

A fantastic trivela puts the ball in the interior of the half-space and Kevin De Bruyne plays a negative cross into the box. Moments later, Bernardo Silva has his goal, extending the City lead.

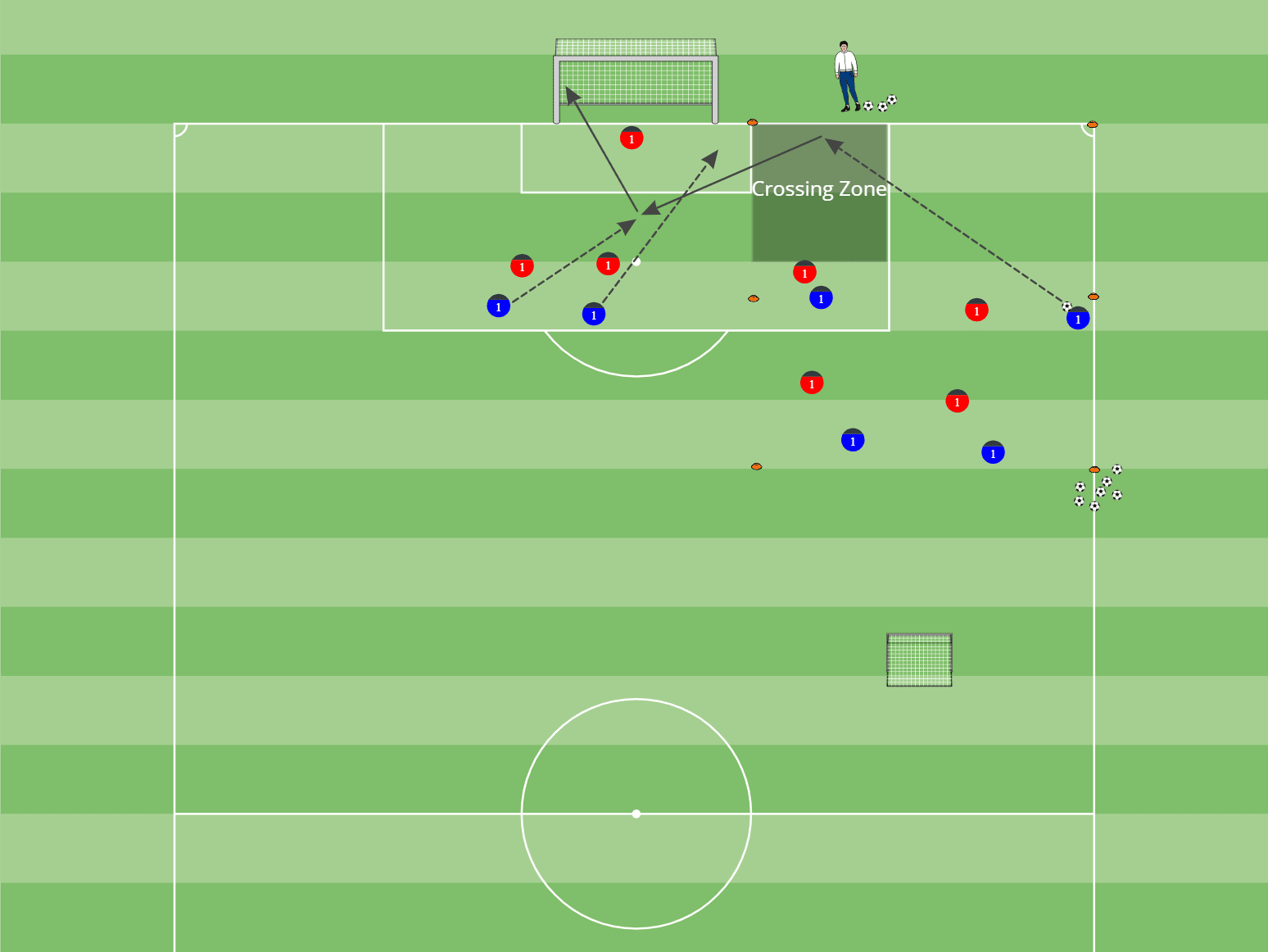

Exercise 2 – Generating qualitative superiorities

Organization

– Field measures 30x width of wing and half-space, plus the central channel for the players attacking crosses.

– Two teams of four in the main playing area, 2v2 in the box. Add an additional defender to the main playing area if numerical equality is too easy.

– When possible, feature goalkeepers in regulation-sized goals. Set out a mini-goal for the defending team to score.

– If you want to prioritize sending the final ball from a specific zone, mark one out, direct the players to send crosses from that zone or create a bonus structure for playing from the crossing zone.

Gameplay

Initially, allow the players to play freely, allowing them to cross into the box whenever they wish. When results suffer, ask how they can improve their crossing success. Let that serve as a transition into targeting a specific crossing, or delivery, zone. Once the players are sending higher quality crosses, remove the crossing zone rule/reward. Test a number of different crossing locations. Play four sets of 5 minutes.

Coaching points

– Limited touches and quick combinations in the main playing area

– Runs need to attack space or pull a defender away from the area you want to attack

– Forwards awaiting crosses must coordinate runs. 1st runner must have a plan.

– Timing of the runs. Don’t go too soon. Often, late runs are best.

– Develop an understanding of where crosses should go based on crossing location and the number of runners available.

Socio-Affective superiorities – “We understand each other better”

Have you ever coached or played with two guys who just seem to know what the other was thinking at all times? Maybe you were one of those people who had a buddy you could play off of at any time. That’s an example of a socio-affective superiority. At the younger age groups and especially within the academies of professional clubs, a club’s culture and style of play should produce players who view the game in a very similar manner. The longer teams or specific players are together, the greater the socio-affective advantage they’ll enjoy.

Barcelona’s La Masia Academy and Ajax’s De Toekomst are the two best-known examples of a club importing a vision of the game onto its youth players and carrying out that style at the highest level. Barcelona’s Golden Generation is the prime example of a team-wide socio-affective superiority, which seemed unfair given they already enjoyed qualitative advantages over most, if not all of the football world.

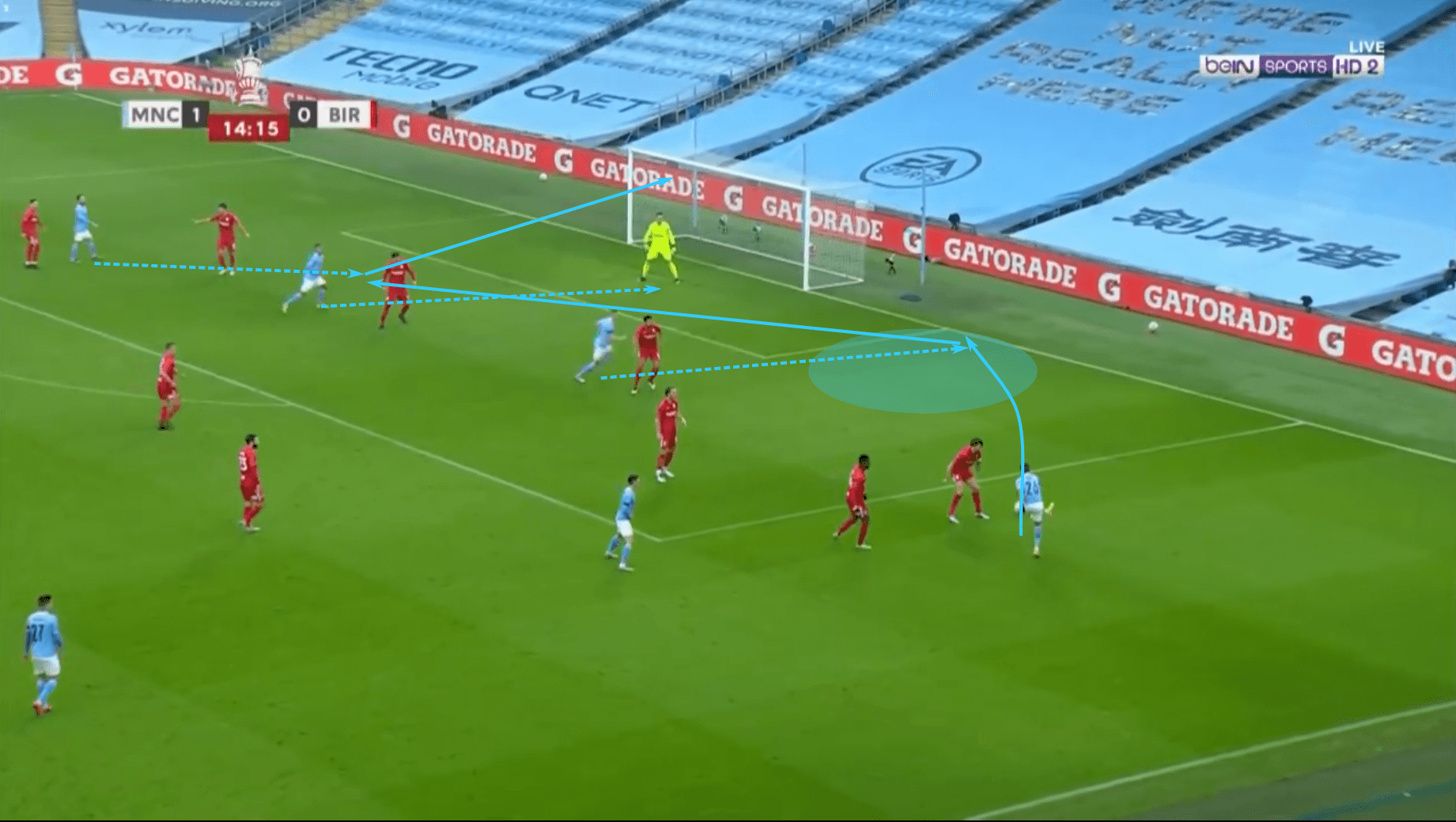

But socio-affective superiorities are still generated easily enough amongst players from various footballing cultures. For our example, we’ll move a couple of hours west of Barcelona to their eternal rivals, Real Madrid. Though the initial Galacticos didn’t enjoy the level of success many expected, the Cristiano Ronaldo era of Galactico’s managed to end Barcelona’s reign at the top of Europe and the famed BBC, Bale, Benzema and Cristiano, offer an excellent example of a socio-affective superiority.

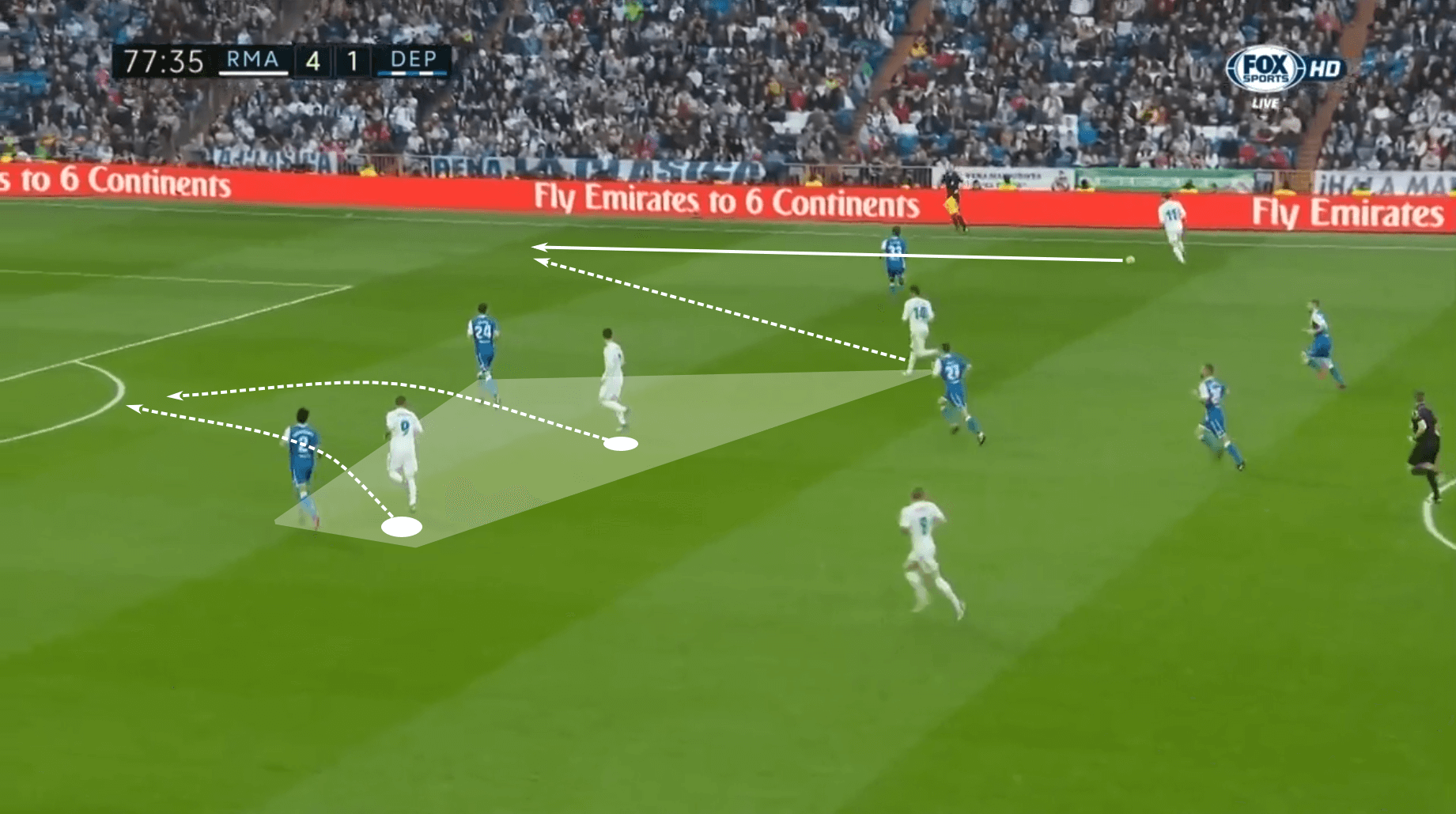

We could use a number of examples from the BBC years, but one area that really stood out was the way they attacked the box. In our first image, we see Gareth Bale, often the wide playmaker of the bunch, in the wing while Ronaldo and Karim Benzema are positioned more centrally. As Bale picks up the ball, a momentary delay freezes the defender, creating a larger pocket of space for Casemiro to run into. In the shaded section of the drawing, Real Madrid enjoys a 3v2 advantage.

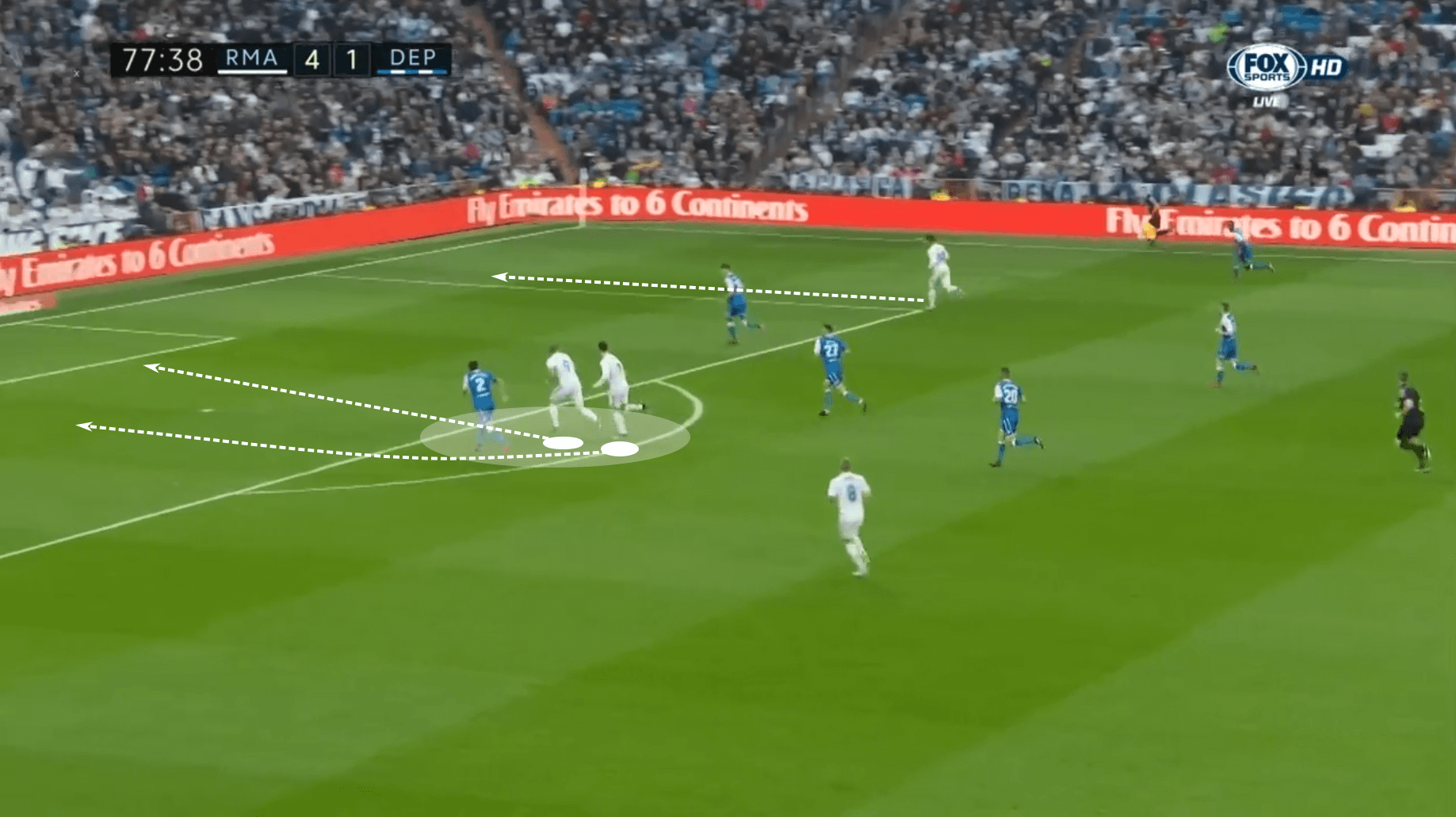

As Casemiro runs onto the ball, the left-centre back is forced into the left half-space to prevent the Brazilian from moving closer to goal. That leaves Ronaldo and Benzema 2v1 at the top of the box. Notice how close the two forwards are.

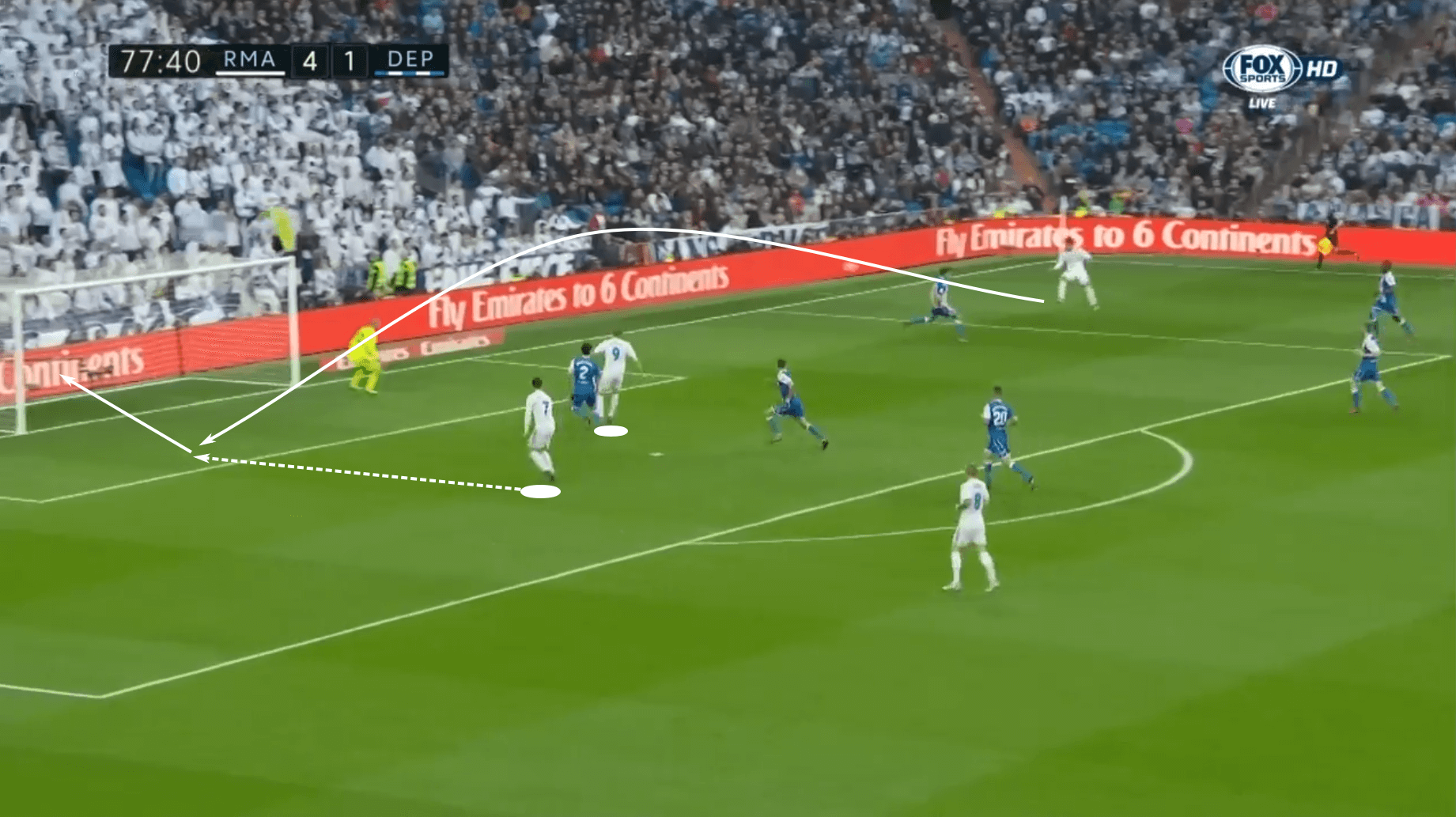

Finally, as the cross is sent, we see Benzema enter the box first, making a hard run to the near post. His run attracts the attention of the remaining defender, allowing Ronaldo to make his run to the back post.

However, notice that Ronaldo lingers behind Benzema. While Benzema’s run is designed to drag the defender to the near post, Ronaldo’s run requires more finesse. He allows Casemiro to put the ball in the air before determining his path to goal. This is to ensure that he doesn’t overrun the cross. Running at the latest possible moment allowed him to meet the cross for a fairly simple finish. The understanding he and Benzema showed on the play is a perfect example of a socio-affective superiority. Because they understood where each other would go, they were able to create a high percentage goal-scoring opportunity for Cristiano.

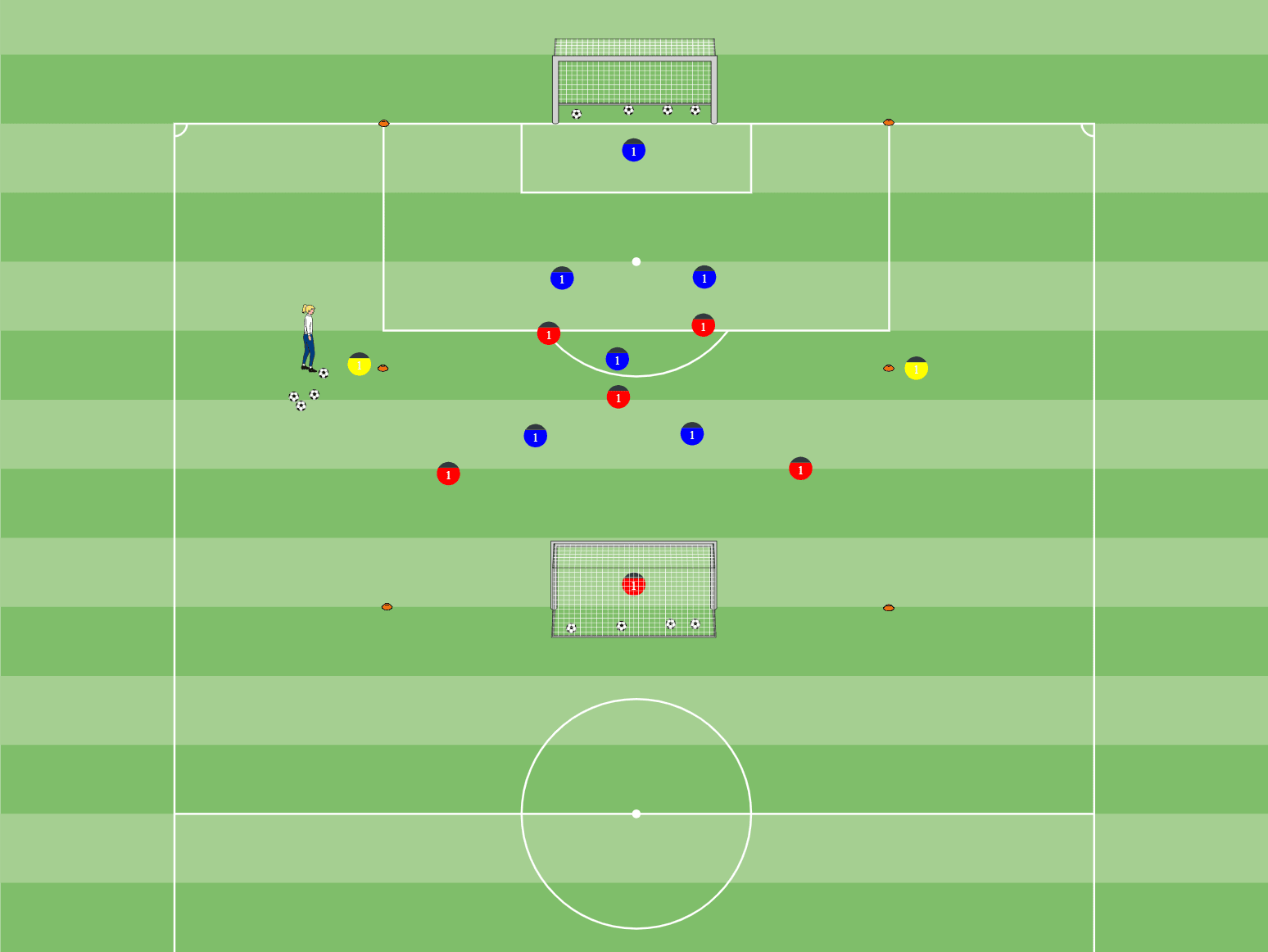

Exercise 3 – Generating socio-affective superiorities

Organization

– Field measures 44v50.

– Two teams of five plus a goalkeeper with one wide neutral/joker on each touchline.

– When possible, feature goalkeepers in regulation-sized goals, as seen on the left-sided pitch. If this is not an option, replace the regulation-sized goals with mini-goals.

Gameplay

Competitive small-sided game with lots of shooting opportunities, especially from crosses. Begin with free play, then factor in bonus points for goals from crosses, headed goals, goals from negative crosses, etc. Whatever you’d like to emphasise, add a bonus point so the players are encouraged to attempt it. Higher bonus points ensure players must prioritise specific deliveries to get ahead or catch up. Defenders can take the ball off of neutrals/jokers to force them to play at a high tempo. Play four games lasting five minutes each.

Coaching points

– Correct body orientation to connect actions

– Have at least two players up top and work on coordinating runs

– Discuss bio-mechanics to predict the trajectory and endpoint of the cross

– Timing of the runs into the box is key

Positional superiorities – “We are better positioned”

Our final superiority is positional. The simple description of “we are better positioned” gives the basic idea, but the superiority is one of the easiest to alter, making it the most volatile and context-dependent of the bunch. One misstep by a defender can sacrifice a position of strong technical balance within their 1v1, just as one poorly timed run can ruin an attacking team’s ability to play beyond the opposition’s lines.

Since we already have examples from the four attacking phases, this section will take a different approach. To highlight positional superiorities, we’ll view them through defensive structure leading to counterattacks, followed by an open possession near midfield against a low block.

Since possession dominant teams must often find a way to solve the problems presented by middle and low blocks, we want to look at alternative modes of confrontation. For many possession dominant teams, attacking transitions are few and far between, but, if well-executed, they can provide the necessary boost to unlock the opposition.

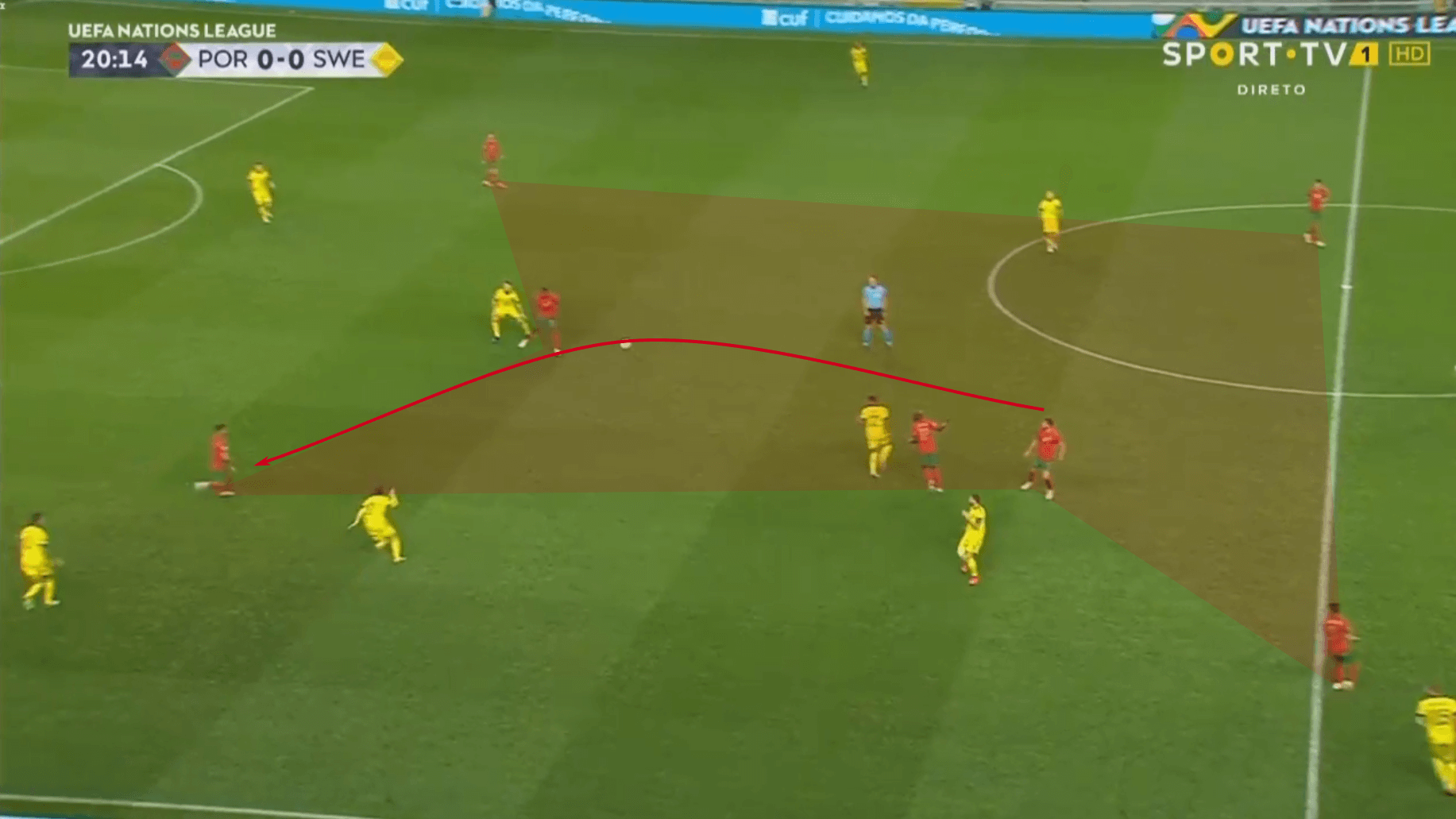

In the UEFA Nations League match between Portugal and Sweden, the host found it difficult to break down Sweden’s compact defensive shape. However, when the Swedes were in possession in the 21st minute, they tried to play out of Portugal’s high press through Alexander Isak. However, Rúben Dias, won the header and Portugal claimed the second ball.

Looking closer at the image, Portugal occupied the central channel and left half-space while Sweden had finally entered their more expansive attacking shape. Though Sweden’s more expansive structure was short-lived, Portugal’s compact shape allowed them to win the first and second balls and quickly transition into their counter-attack. Portugal was “better positioned” to defend than Sweden was to attack given the specifics of the delivery. Being better positioned to defend immediately put them in a scenario where they were better positioned to attack. So, therefore, Portugal had positional superiority relative to the pass Sweden opted to play and within a more general context, forcing Sweden to play into a position of Portuguese strength.

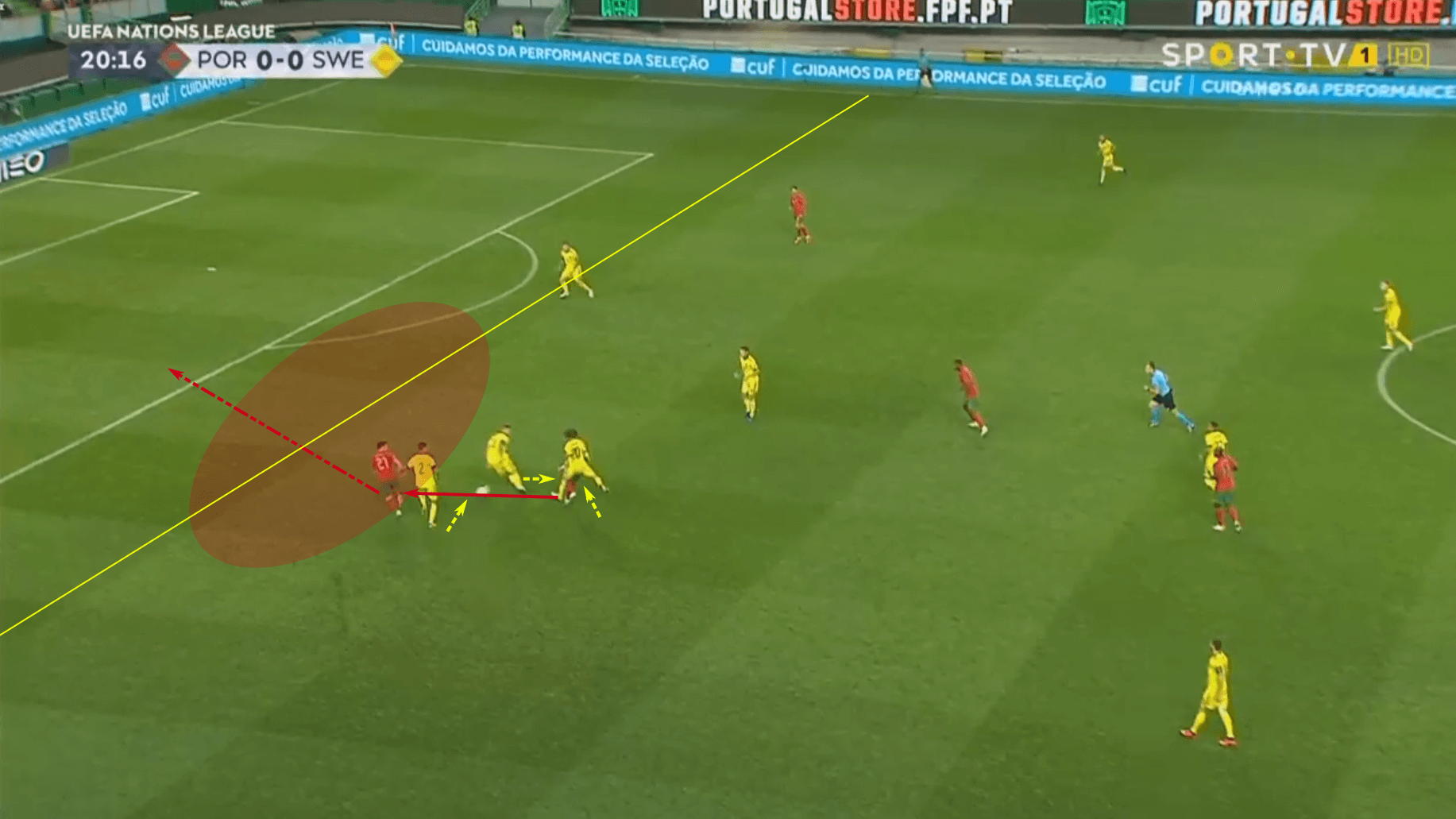

Now, moving to the counterattack itself, Portugal is on the ball in a 2v3 situation. Though Sweden are numerically superior, Portugal still have positional superiority. The arrows on the pitch indicate the direction in which each player’s momentum is taking him. While the Swedish players are either moving towards the ball or the middle of the pitch, the momentum of the Portuguese players is directed towards goal. Further, the far-sided Swedish defender is five metres behind his teammates, creating a space for Diogo Jota to run into. The ball is slotted into that space and he breaks into the box.

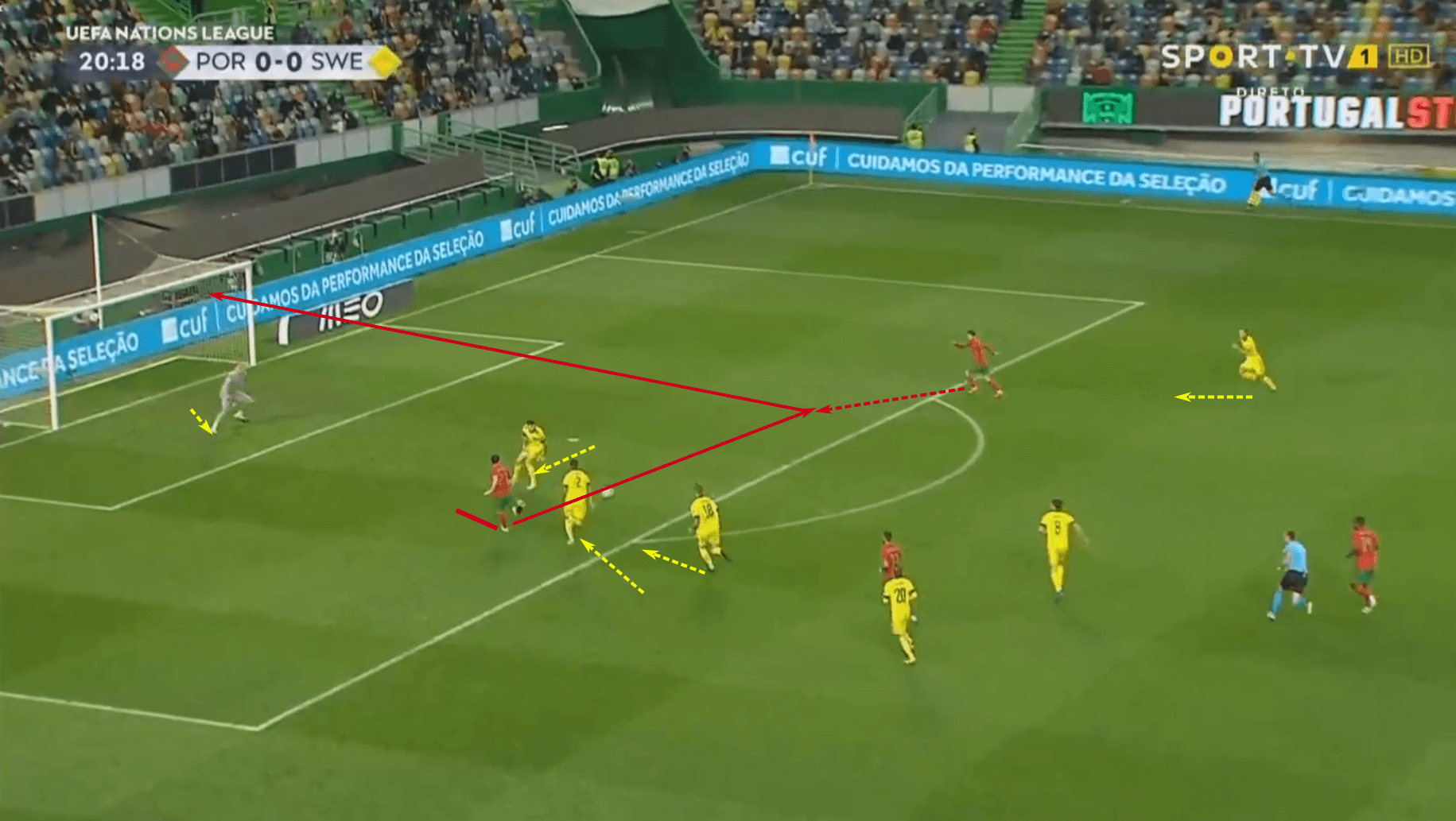

Once Jota enters a shooting position, the far-sided defender arrives on the scene to close down any further dribble. That prompts Jota to play square to João Félix, who produces the finish. Again, looking at the image, the momentum of the Swedish players is directed towards the ball. On the far side of the pitch, we have one defender closing the gap between himself and João Félix, but he’s so far behind the play that his movement is inconsequential. The Swedish defenders are unbalanced towards the intervention space, producing Félix’s positional superiority to Jota’s right.

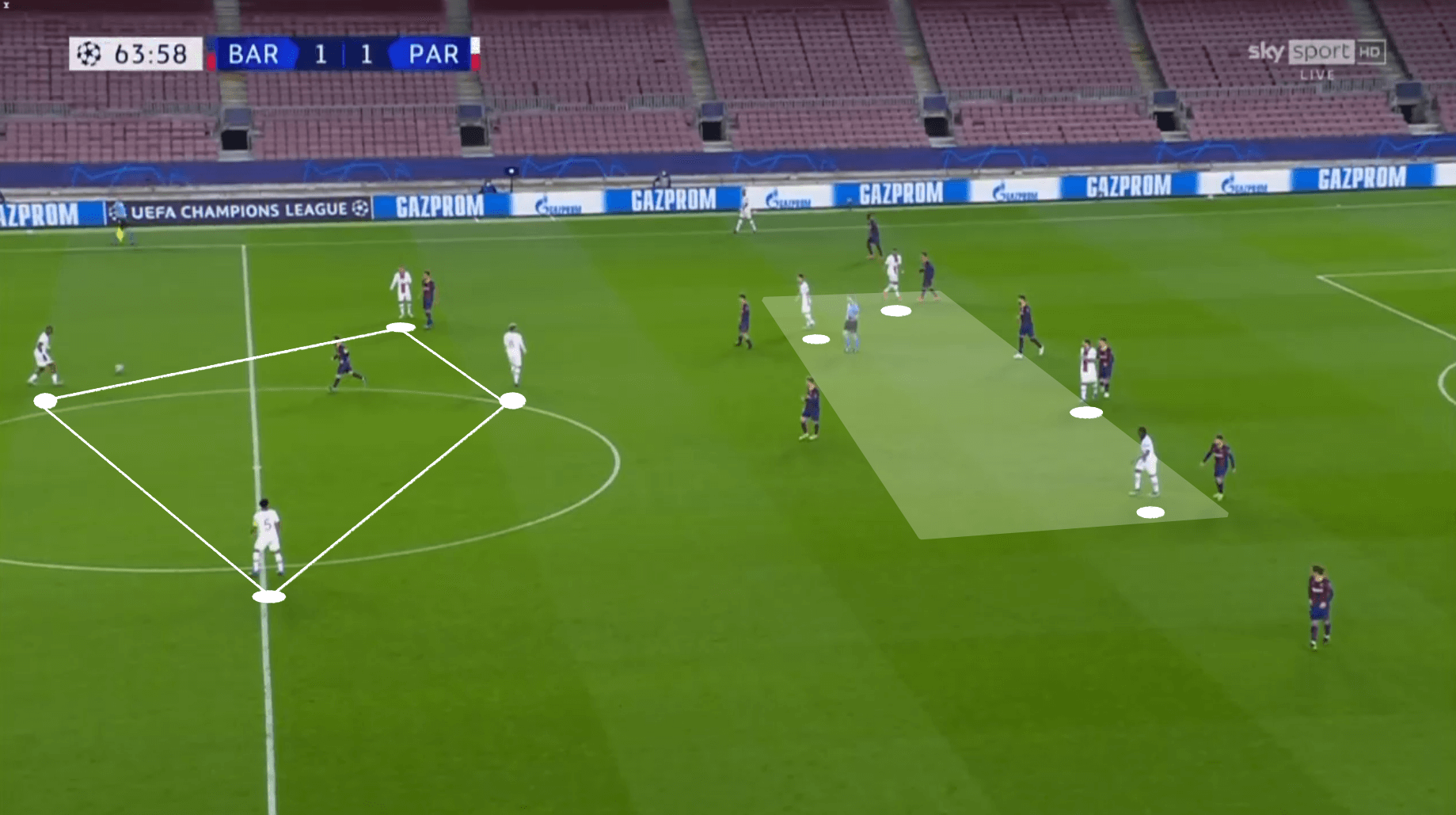

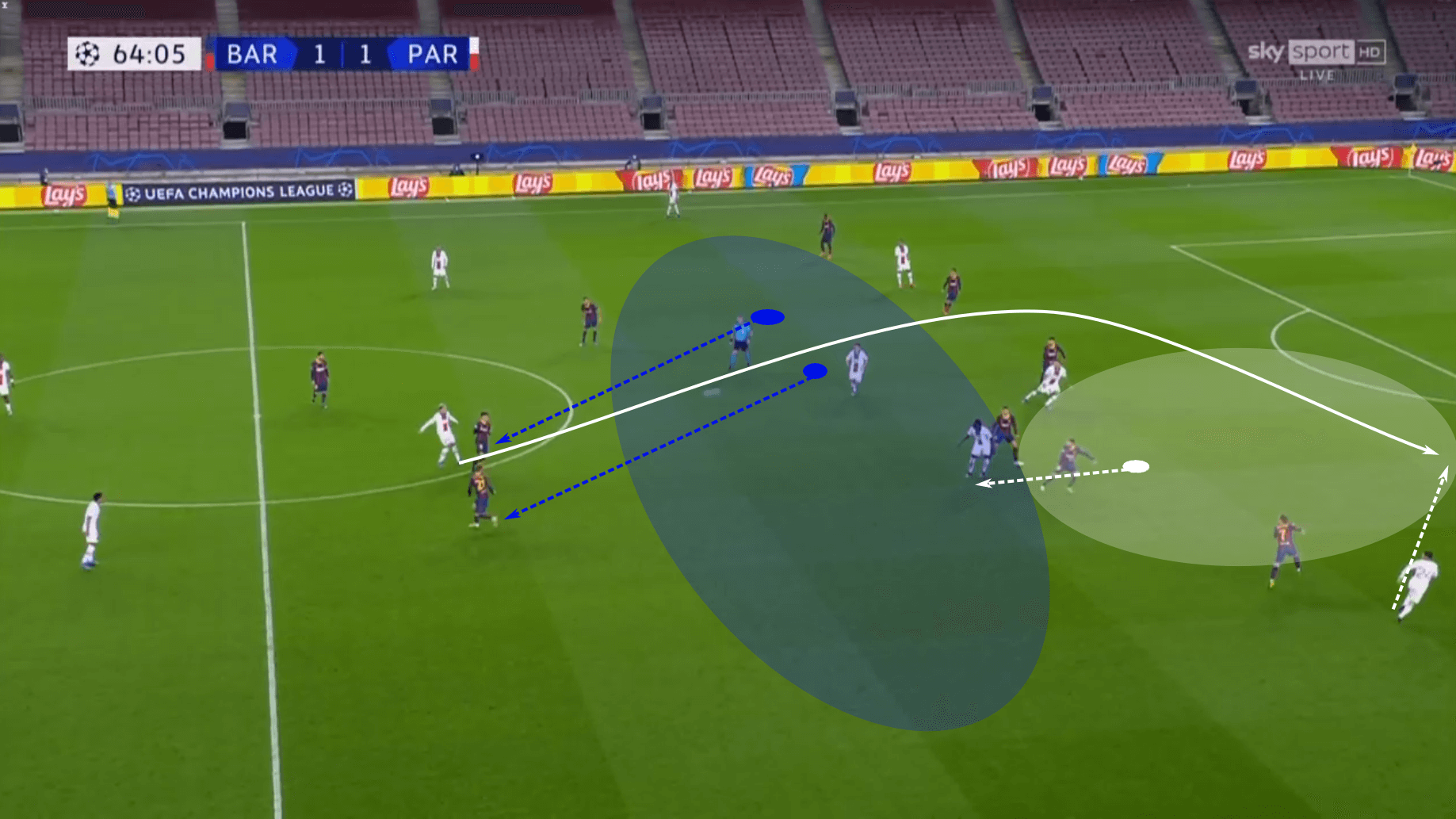

The final scenario we’ll address is generating positional superiorities against the low block. For this example, we’ll look at the first leg of the Barcelona vs PSG Champions League tie. PSG was in the midst of an open possession, prompting Barcelona to drop numbers behind the ball. PSG pinned the opposition deep but was unable to find success penetrating the low block. Rather than attempting a low percentage play through the defence or a shot from 30 plus meters, PSG recycled play to midfield.

The Parisians enjoyed a 4v2 near midfield, allowing them to keep the ball with ease. Barcelona was settled in a 6-2-2, meaning PSG was better suited to show patience and manipulate their opponent’s defensive structure before looking for the final pass. Note the high central overload of PSG players. They’re 4v4 against the Barcelona backline.

As PSG moved the ball among the four players at midfield, those two players making up Barcelona’s midfield stepped higher up the pitch to help pressure the opposition. As they pushed higher, the gap between the lines widened. Notice that two PSG players have moved into the gap between the lines, leading to a gap in Barcelona’s left half-space. Once that space opens up, PSG is queued to make the run into the space the defenders vacated and play the ball over the top. Recycling play and showing patience in possession drew Barcelona higher up the pitch, which created gaps in their defence. Rather than attacking Barcelona by altering their width, PSG attacked them on the Y (vertical) axis. Targeting specific players, drawing them higher up the pitch, lead to gaps along the backline that PSG could attack.

One coaching point to remember is to coach the runners in their movements to goal. Ensure 1) they make the run, 2) they run to the correct spaces, 3) the run itself creates separation from the defender and 4) timing the arrival to perfection.

Exercise 4 – Generating positional superiorities

Organization

– Field measures 44v60. 44×8 Finishing Zones 10 meters from each goal.

– Two teams of six plus the goalkeepers.

– When possible, feature goalkeepers in regulation-sized goals.

Gameplay

The objective is to pass a teammate into the finishing zone. Free play at first, with just one exception. Require players to shoot from the Finishing Zone. Next, require Finishing Zone entry from a pass only. No dribbling into the Finishing Zone. Play four games lasting five minutes each.

Coaching points

– Correct body orientation to connect actions

– Integrate changes in tempo to keep the opposition off balance

– Timing runs behind the backline, coordinating them with a teammate’s ability to play forward

– Create the space you want to attack by dragging and disconnecting the defence.

– Composure and urgency with the finishes

Conclusion

As we wrap up, one important note is to remember that all superiorities are in relation to the opposition. Numerical superiorities are more stable because they are objective, but the other three measure the advantages of one player or group against the advantages of the opposition. Even here, positional superiorities are highly dependent upon context, one socio-affective relationship may be better in one situation but worse against another set of opponents and a qualitative advantage can be impacted by fatigue or the mental state of the player.

We want our players to assess the game and generate superiorities, but we also need to emphasize that superiorities are highly volatile. One of the underlying principles of training superiorities is to teach players to constantly assess their most common individual matchup, their most common small group engagements, and to have an understanding of the team’s strengths and weaknesses as the match progresses. Football is a wonderfully dynamic game with constant changes in momentum and initiatives. Teaching players to see the smaller battles within the greater game is how we direct their focus on the events in which they can exert greater control. Possession dominant teams often find their players over stimulated by the number of data points they have to process. Taking a superiorities-based approach to training, we can help our players see beyond the chaos and focus more intently on the advantages available to them.

Comments