The subject of goal kicks is one that saw its popularity peak in 2019 when a rule change meant that players from the in possession team could now move inside the box before the ball had been played. With this rule change came multiple ideas and strategies around how to now progress the ball with more depth to your possession as well as having more of the pitch to use, and so as with anything in football, we saw teams have varying success with multiple different strategies. Only two years on from this rule change, interest or focus in this area seems to have reduced again, and I for one haven’t seen many analyses of goal kicks and how they can be used.

Despite this, there are still multiple teams using very interesting concepts from goal kick situations, and with this being an area of set pieces very closely intertwined with open play, I decided to investigate the most interesting concepts displayed by teams around the world. This tactical analysis will examine and break down those key concepts from goal kicks, giving examples of structures, principles, and variations that can be used from goal kicks to progress play- be that vertically, dynamically, or in a more patient, shorter manner.

Drawing the opposition higher

One of the main advantages of goal kicks is that they take place so deep on the pitch, and so in terms of short progression play, if the opposition want to press you tightly and cover options, they have to commit their own players high up the pitch. As a result, a common tactic from goal kicks is to lure the opposition higher to then go over them.

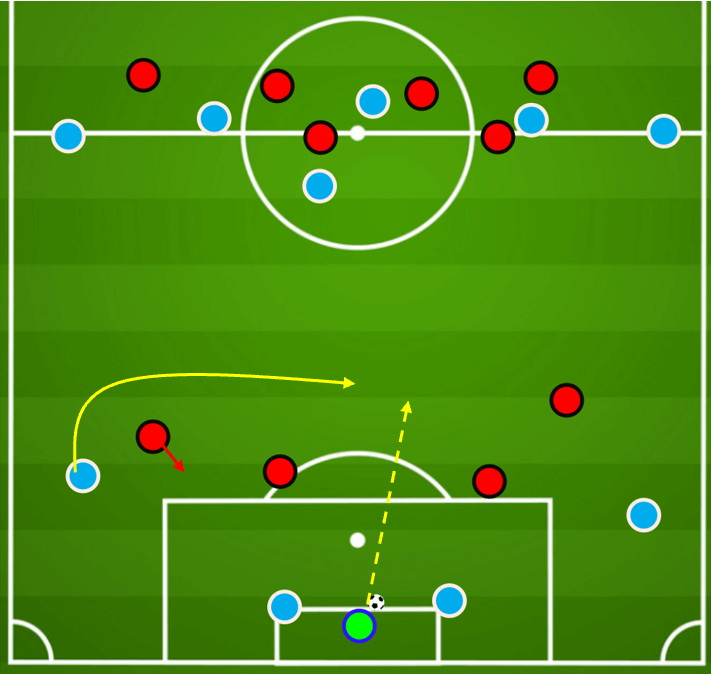

As in open play, playing directly into a congested space is poor for ball progression, as you have no space to receive the ball after the direct pass often. Therefore, the key aspect of direct play is finding a way to support that direct pass, but this has to be balanced with drawing the opposition deep enough. We can see an example below of a typical tactic used from goal kicks, where two central midfielders are committed very deep to draw the opposition midfielders high.

The aim behind dropping midfielders so deep is to then decrease the overall vertical compactness of the opposition, and so players now have to arrive into this space created and then create angles to receive the ball again.

How you support the ball obviously depends on the angle and distance from the receiver, with the most favourable angle being one that allows you to play forward immediately. Naturally, if players just stood behind the receiver, they would be marked (especially in the centre), and so dynamic movements into an area of support are usually the most effective method of progression.

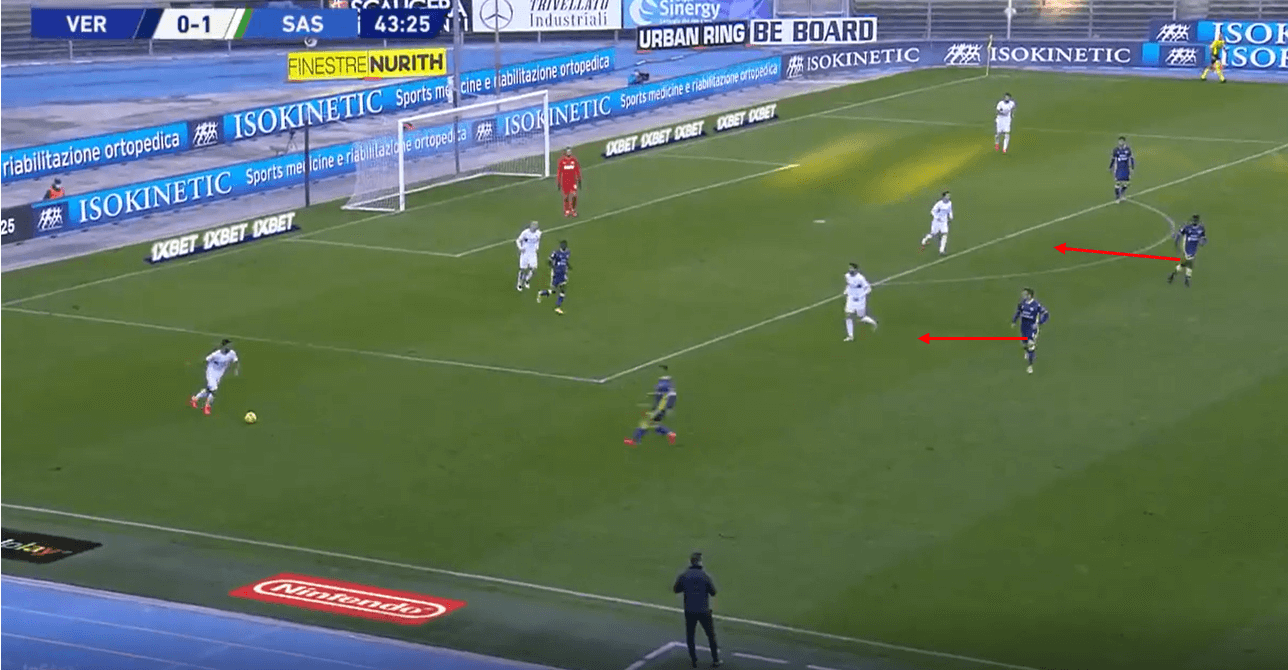

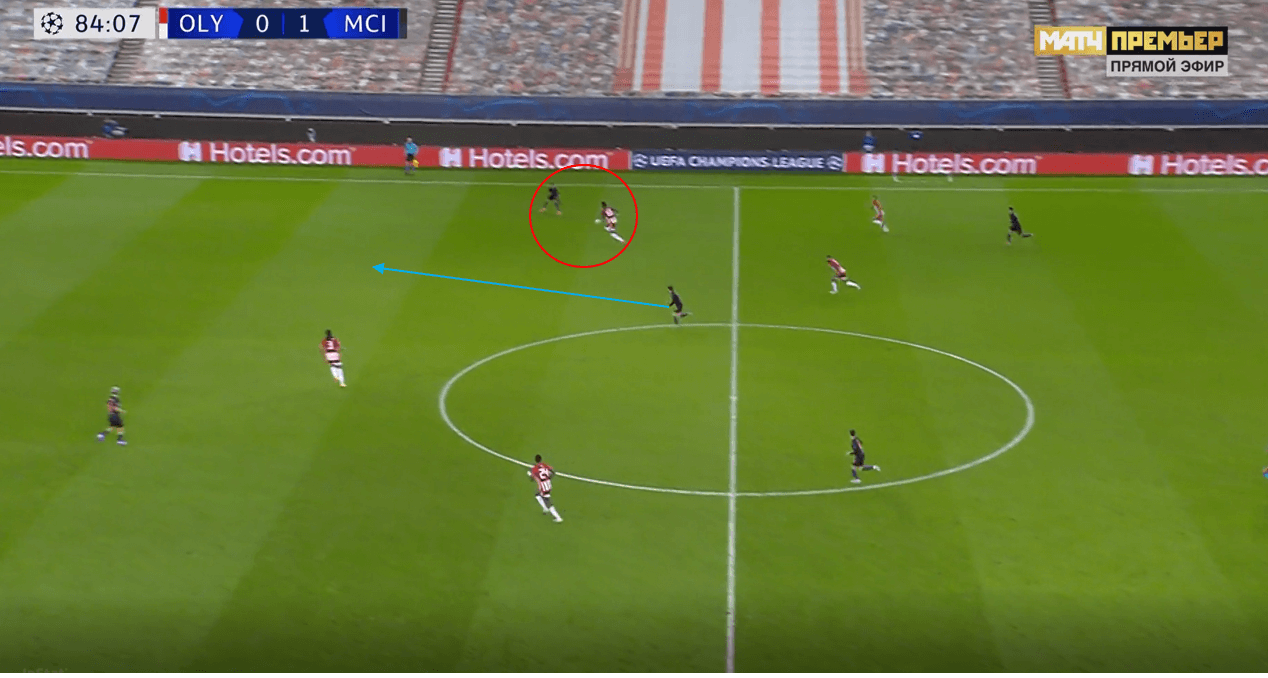

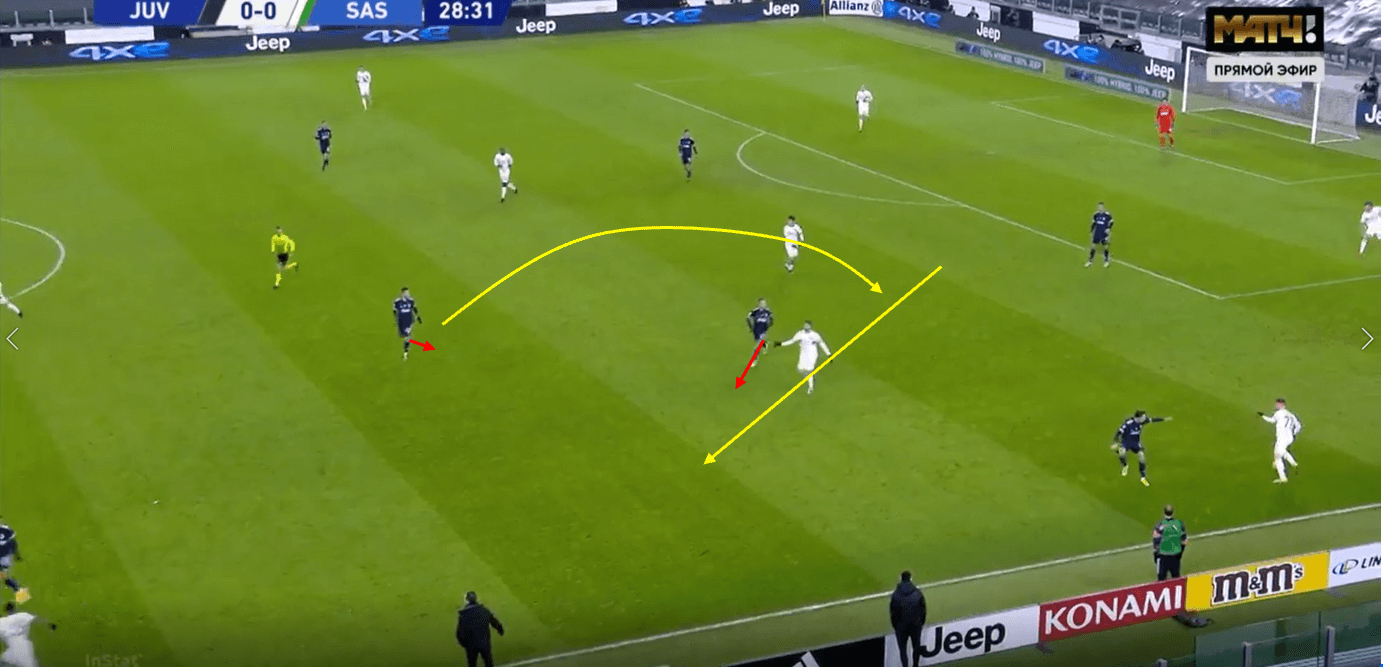

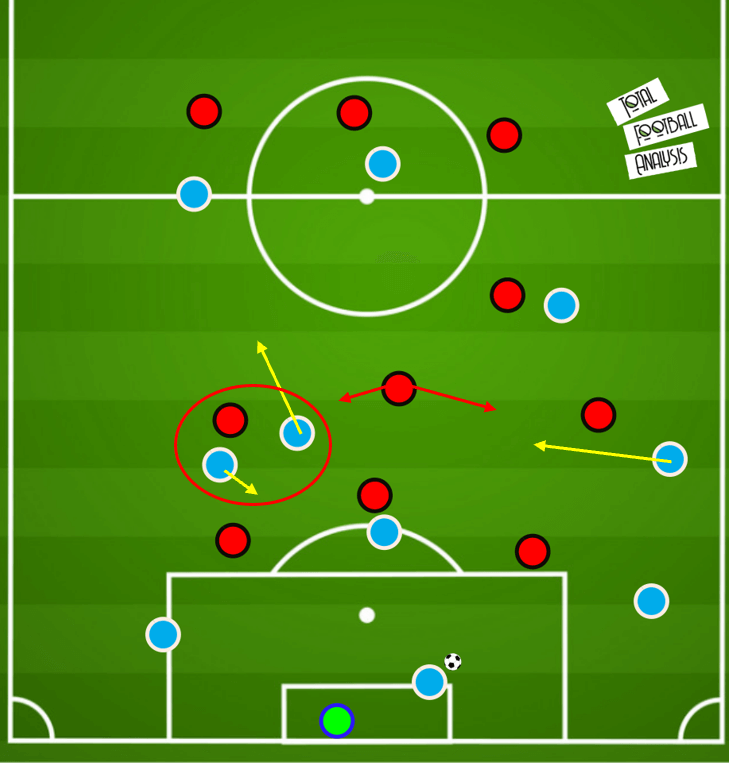

We can see an example of this here, where the defending team acts in a fairly man-oriented fashion in a 442 shape against the in possession teams 4-3-3. The defending team’s midfielders move high to press and are overloaded despite this, but their movement high naturally creates space behind. If one of the possession teams players was to just stay higher to provide support directly behind, they would ruin the space created and help the defending team’s vertical compactness, as they would likely be marked. As a result, a well-used pattern is a wide player moving inwards to receive the pass, which is especially useful if your wingers are inverted. Full-backs don’t want to follow players centrally and they also have to react to this kind of third man run which can be difficult. If you can play to the furthest player and provide vertical support, you still need height in your team to penetrate, and that then comes from the far winger moving behind. Simple up, back, through movements like this are used and attempted by teams at the highest level from goal kicks.

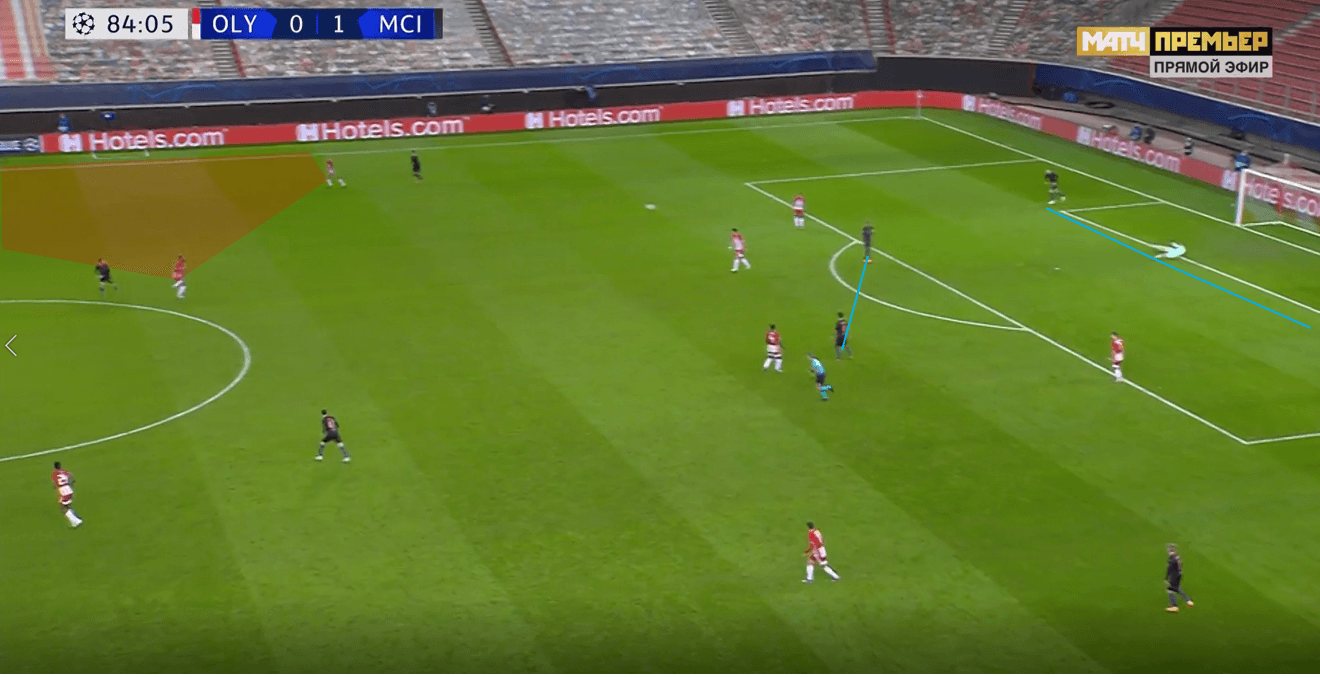

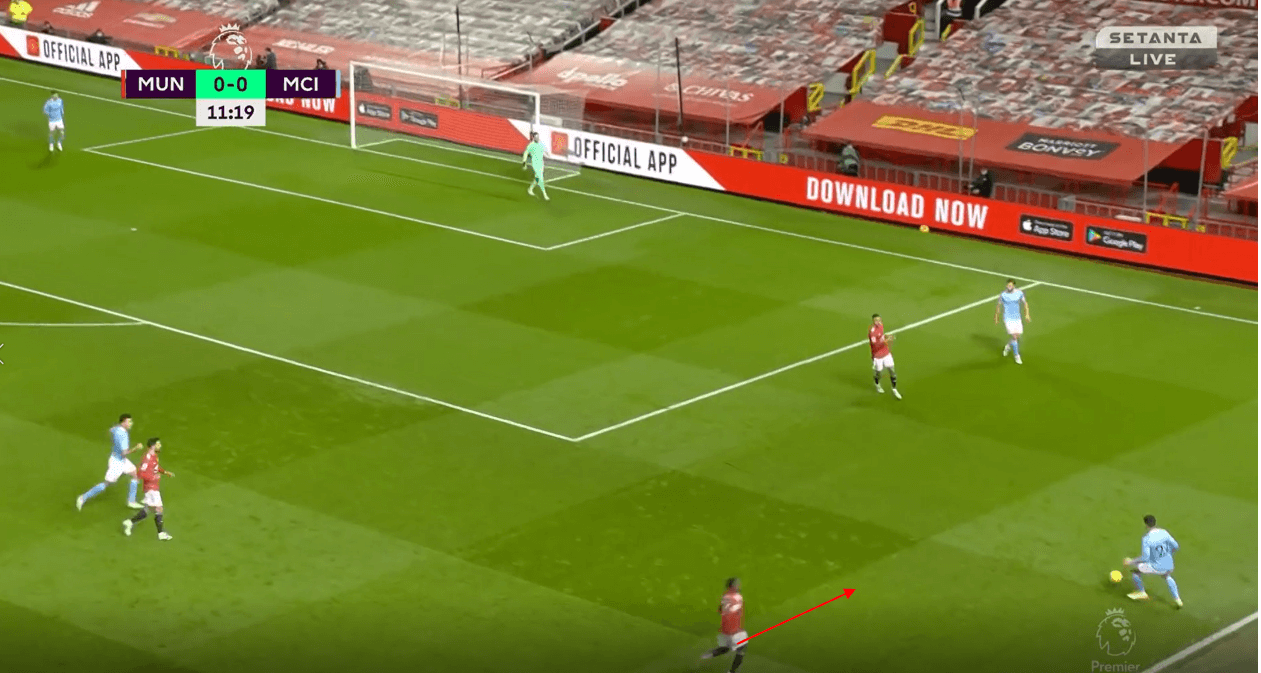

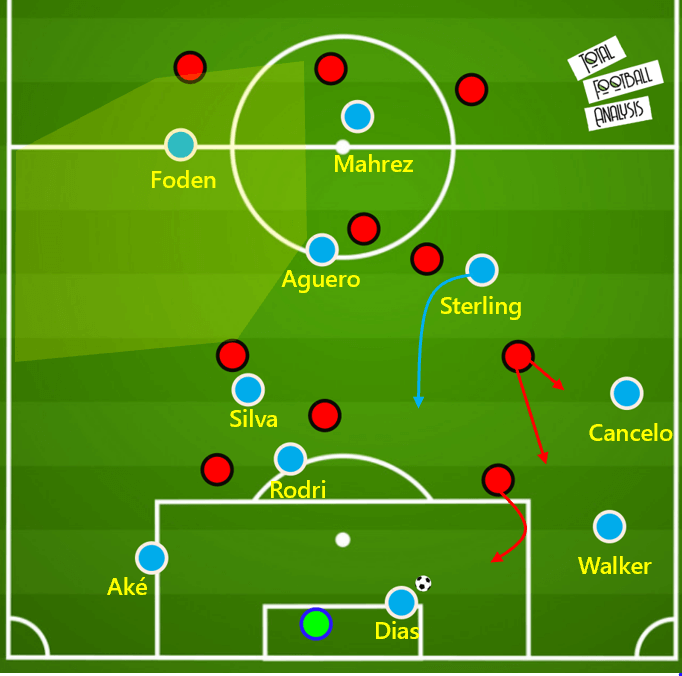

Teams that you would associate with a more patient, short build-up can use these kinds of patterns and ideas to their advantage even more, as the opposition is likely to prepare to press them in a high area. Manchester City have a massive advantage in Ederson, in that he can play short, and also has the best long-range distribution probably in the world. We can see an example here of City having Riyad Mahrez inverting from a wide position to provide vertical support to a central player.

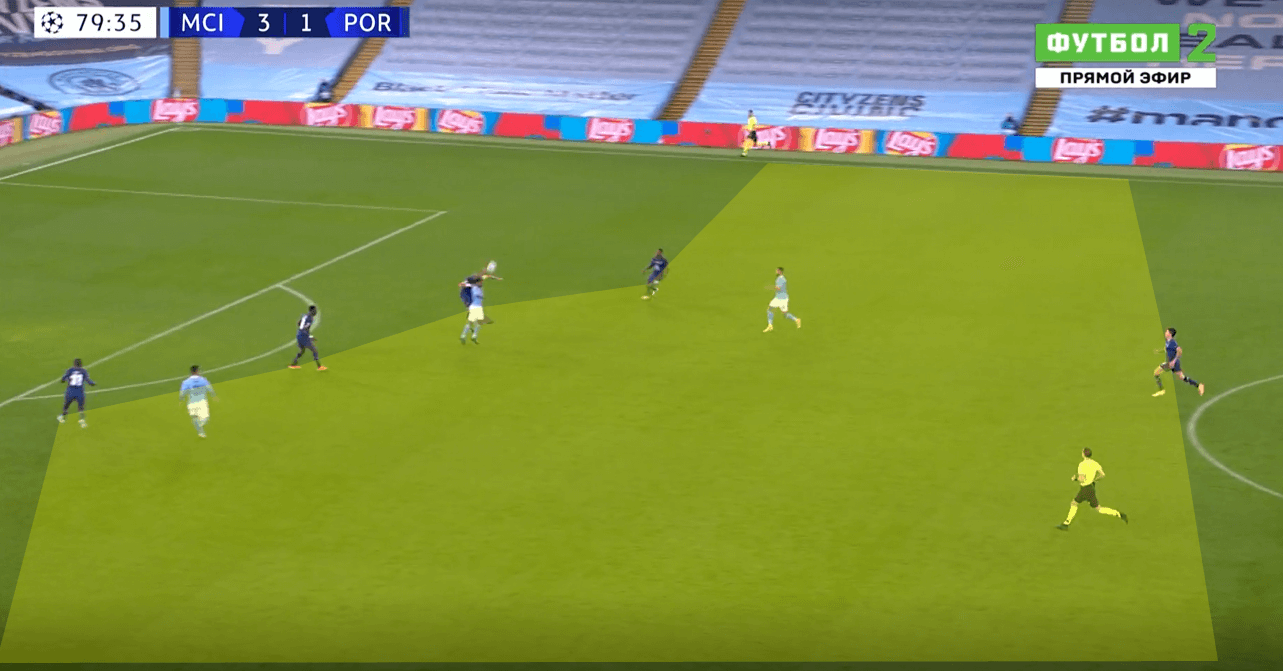

Another useful advantage Ederson gives can be seen in that previous example, in that this pass directly from a goal kick ends up about 25 yards from goal. As a result, the opposition cannot push their line higher against Man City, as if they do Ederson may be able to just kick it over them. The offside law obviously prevents you from being offside direct from a goal kick, and so something City have used over the past few years is a striker behind the opposition defensive line as a threat.

We can see a few vital concepts in this example from Manchester City. As I’ll discuss in detail later, their use of positional play concepts and Ederson as an extra centre back allows defenders to space wider. In this example, that means a City player can push high and wide as a wing-back. City commit two central midfielders deep and leave two slightly higher, and so are structured in a 3-6-2. Because of City’s use of a back three and wing-backs, Olympiakos’ full-backs are forced to press wider and higher, and so when this is combined with central occupation by City, spaces open up between.

Ederson slips while kicking, but he is still able to get the ball all the way to a wide player for City. The positioning of those two higher City central midfielders almost causes an interception, but they are just able to retain the ball. From there, those central midfielders can push forward to support the ball. Finally, we can see that threat being posed by Aguero here, as he is stood in a clear offside position when the first kick is taken. Again, not only does this offer the opportunity to get in behind, but it also makes the opposition less compact, as they are forced to stay deeper.

I will revisit these direct combinations later, with the idea being that most of the concepts within this analysis can overlap and intertwine in one phase of play.

Use of the goalkeeper in build-up structures

As I’m sure you’re aware, the use of the goalkeeper has evolved over the past decade massively, and certainly in shorter build-up phases from goal kicks goalkeepers are being asked to contribute more and more as an outfielder.

Goalkeepers will usually act as one of the centre backs in either a back two or three and their natural presence as an overloader creates more superiority than just numerical.

Using a goalkeeper in a back three gives the same advantages as regular back three does, in that it allows for wider spacing by the centre backs, and therefore stretches (at least) the first line of opposition pressure and gives vertical lanes in the centre and half-spaces. If a goalkeeper joins a back three, all of this still applies, but the possession team now doesn’t have the disadvantage of having to sacrifice a player from a higher position.

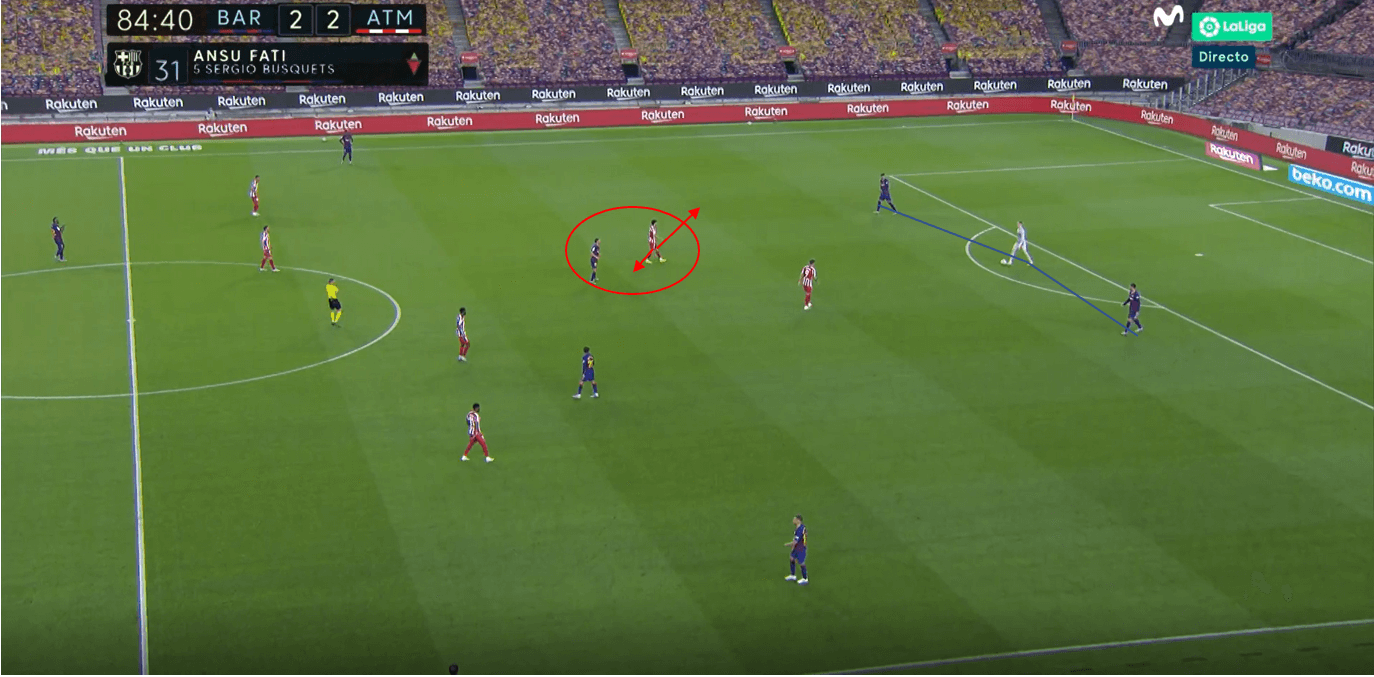

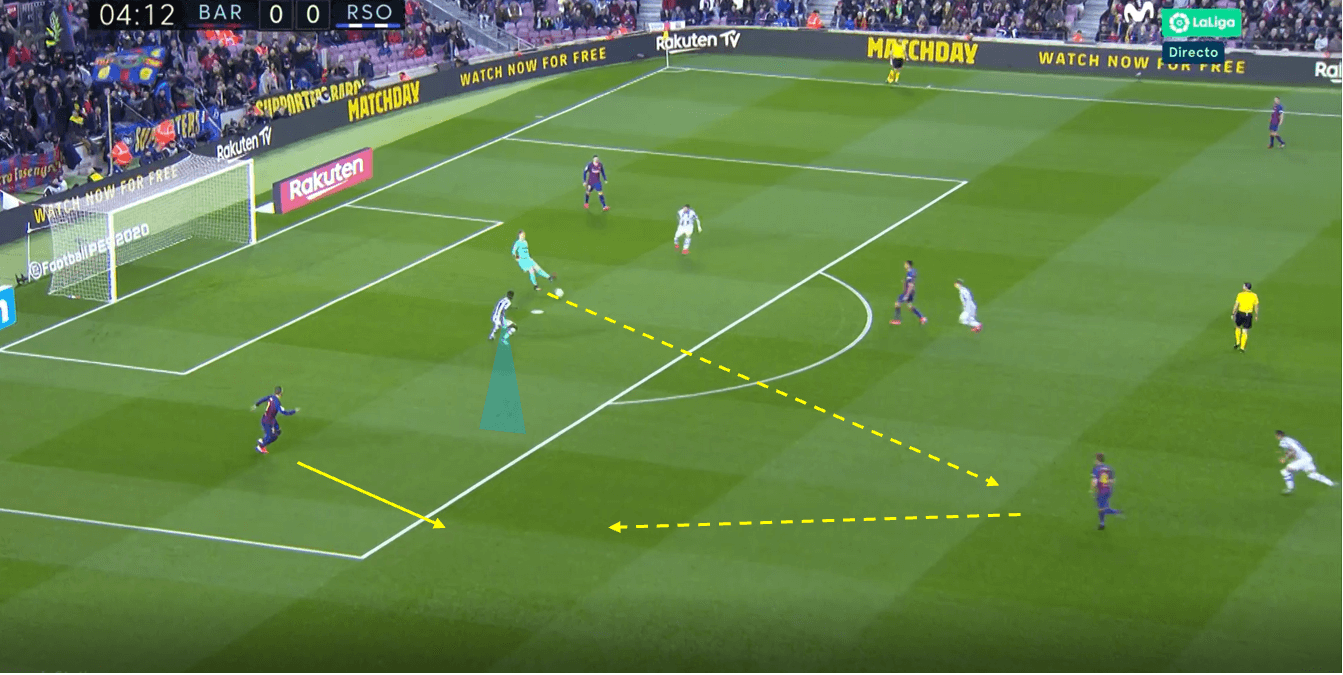

We can see an example of Barcelona under Quique Setien using Ter Stegen in a back three here, against a more passive Atlético Madrid 442 shape. Although Atlético stay in a fairly stable structure, this example still demonstrates the effect of the goalkeeper in a three. We can see Barcelona drop into a double pivot, with the most central of the two using the depth of the pitch well to avoid being pressed, with Atlético happier to sit off slightly to avoid being played over. As a result, their left striker has to be slightly passing lane oriented around this Barcelona pivot. This in turn affects this player’s spacing in relation to pressing the wide centre back, and so you can see whichever player they focus more on, they always have a disadvantage. The striker protects the central lane more here, and so Barcelona spread the ball wide and face little pressure.

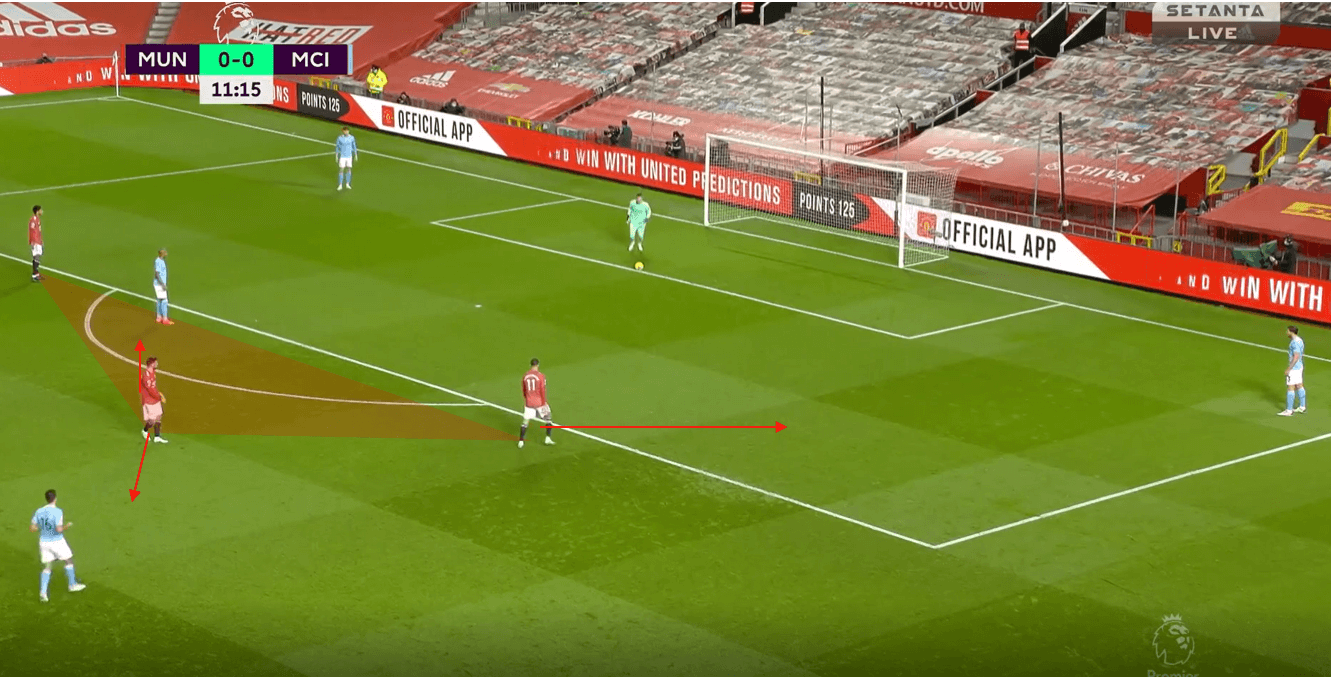

If teams press more aggressively, as in open play the back three can be used to manipulate their pressing structure. Here we can see an example from Manchester City’s match against Manchester United which demonstrates this well. United pressed out of a 4-2-3-1 shape in this game, and so, by using a back three from goal kicks this posed a problem for United. We can see here as a result of City’s wide back line, right winger Mason Greenwood is forced to press a wide centre back, effectively becoming a striker in his current position to also cut any diagonal lanes. Bruno Fernandes is engaged by both two central midfielders, and balances between the two.

Because City’s back three structure using the goalkeeper engages Mason Greenwood to engage, United’s high wide area is vacated, and so they rely on Aaron Wan Bissaka to push very high from full-back. If you’ve read any of my previous work, you’ll know that full-back on full-back presses can be dangerous if the right cover is not provided behind, and with United using a 4-2-3-1, they rely on their back line and two sitting midfielders to balance between their central markers and players moving into Wan Bissaka’s space. Sterling drops into this space and receives to win a foul, so United escape fairly lightly, but again this kind of sequence has the potential to cause some serious issues for the pressing team.

This use of a back three in the first line then can stretch two-player presses in the first line very well too, especially if strikers are intent on focusing on the wide centre backs only. As we saw in the Atlético example, if strikers want to press onto the wide centre backs, they have to space wider to give themselves chance to do so, and this naturally opens up central space. This space is the pivot space and can be used to manipulate the opposition in several ways depending on their pressing strategy.

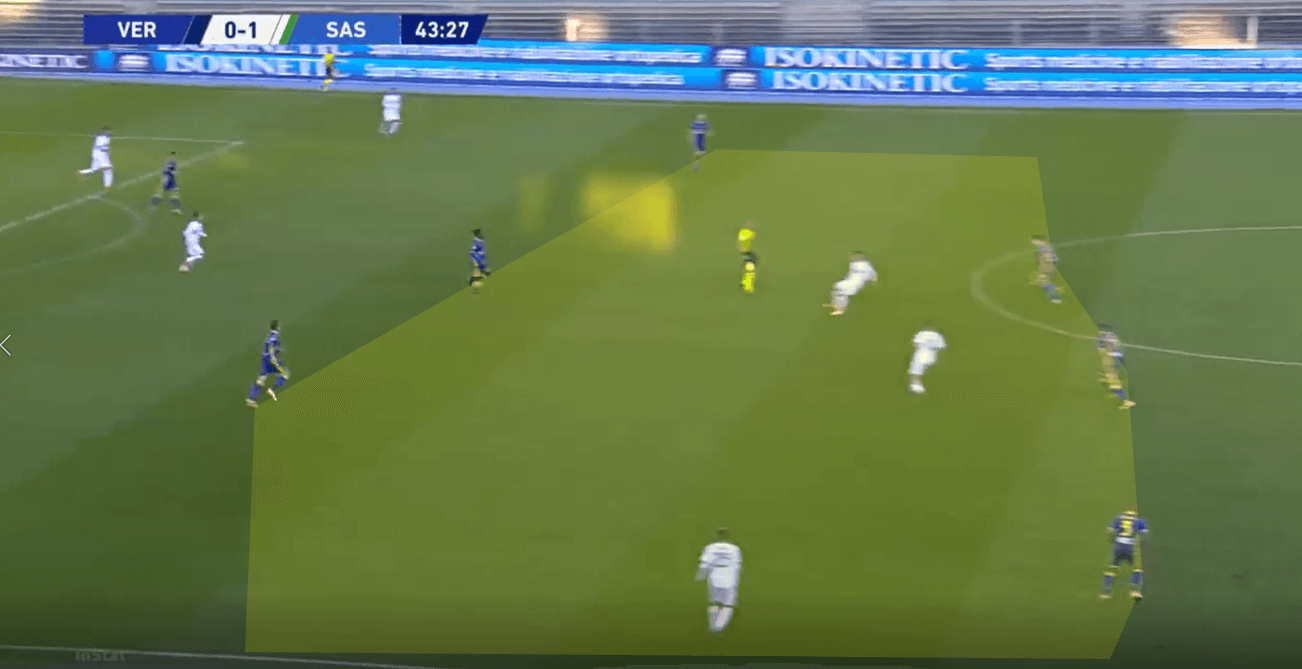

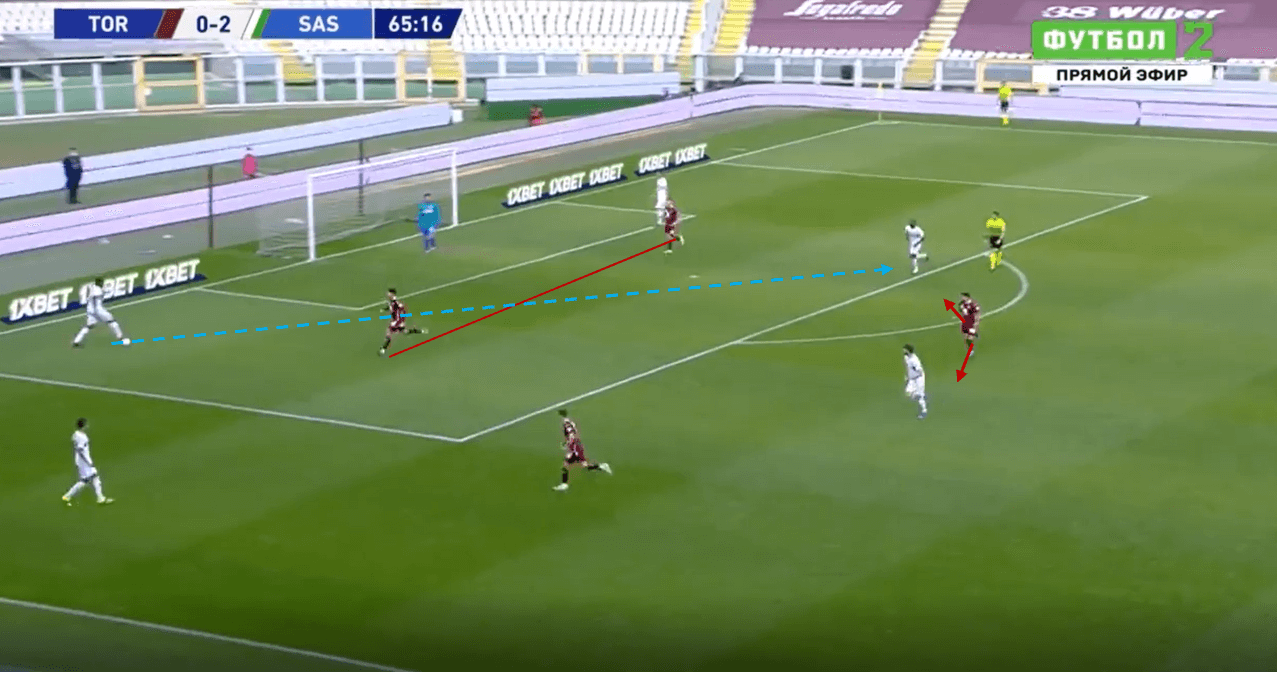

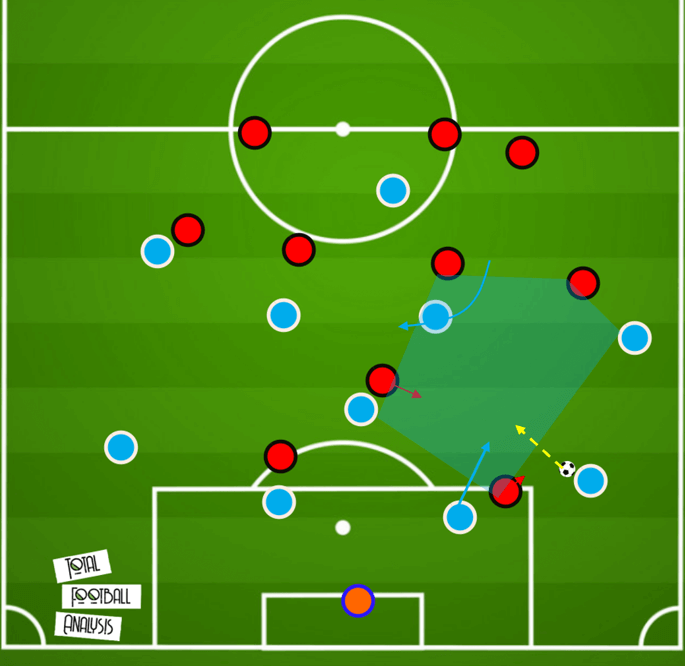

Serie A side Sassuolo are a team that are particularly good in the pivot space, using both static overloads and dynamic space occupation to progress play. We can see an example here where they use a back three involving the goalkeeper, and increase the spacing between the two strikers. They overload the pivot space with two players here, and are then able to play a risky but very beneficial pass between the pressing strikers.

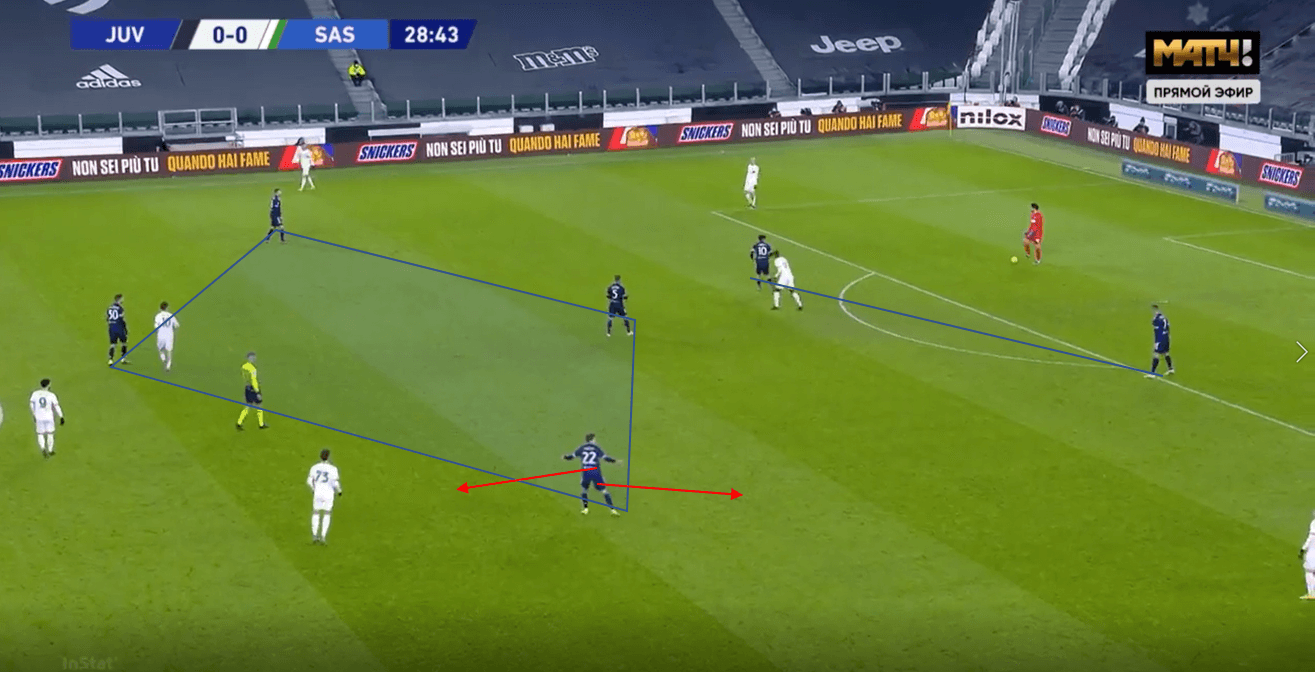

We can see a nice example of their shape having several effects on Juventus here, with their use of a back three and single pivot forcing Juventus’ 4-4-2 pressing shape into a 4-3-1-2. We can see Federico Chiesa on the far side is overloaded, as he is given the job of pressing wide and covering a central option. Sassuolo can work the ball wide as a result of Juventus’ spacing in the first line.

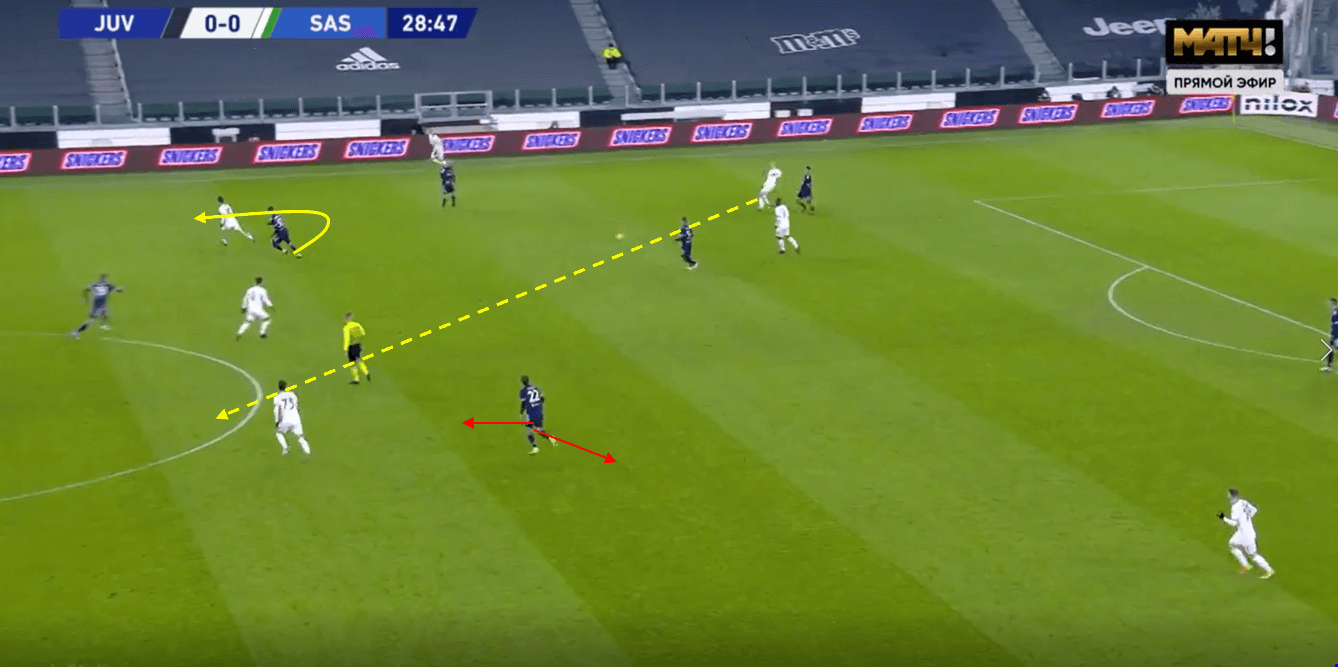

As a result of the ball being allowed wider, Juventus’ midfield is stretched further, with the ball near winger pulled wider, which in turn forces the lone central midfielder wider also. He is spun by his marker, who pulls him away from the central space further with this movement. Sassuolo then drop a player into the central space, and he drags a defender with him. Chiesa on the far side is still in two minds and doesn’t move narrower, and so Sassuolo are able to play an excellent dummy into this far diagonal option, and now have direct access to Juventus’ last line. All of this stems from that use of the goalkeeper in a back three and the subsequent effects it has on Juventus’ pressing structure.

Sassuolo have some excellent dynamic examples of using the pivot space, where for example they will occupy it, move out, and then drop another player in. We can see an example here where one pivot drops centrally in front of the goalkeeper in order to receive and play wide. Once they have played wide, they make a forward run out of the pivot space, while a previously higher midfielder drops into the now-vacated space to receive freely.

Tim Walter’s Holstein Kiel and Stuttgart are also famous for their dynamic occupation of the pivot space, where they will often empty it and rely on a centre back to make a dynamic movement into this space. You can see some of my previous analysis of Walter’s sides in the link.

A final very common and useful way of using the goalkeeper in either a back two or three is using third man plays to access wider players. Barcelona used this frequently under Setien, with their splitting of the first line of pressure helping to access their pivots, who could then lay the ball off with ease. We can see a typical example here, with Real Sociedad’s strikers split wider as a result of Barca’s structure. The strikers press diagonally, and so centre backs cannot be accessed by the goalkeeper initially. This structure then gives Ter Stegen increased access to central areas, which then allows these previously inaccessible centre backs to be used. Barcelona use a double pivot here, but often just allow Busquets to play these passes alone.

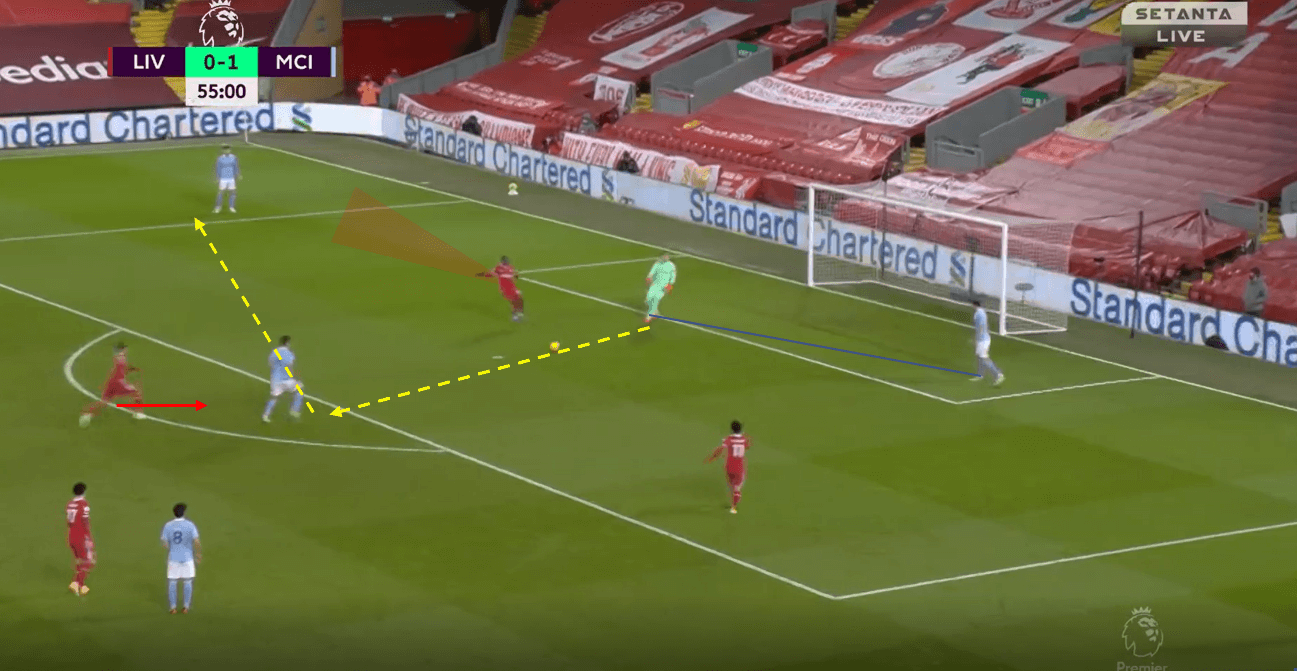

Manchester City use the same concept here against Liverpool using Ederson in a back two. This back two is used deliberately against Liverpool, with their aim being to use a single pivot to occupy Firmino, forcing Liverpool’s two inside forwards to press diagonally. If this was in open play, Roberto Firmino would shield this option, but he cannot. since he cannot enter the box, and so the third man play out to the wide centre back is on once Sadio Mané has engaged in the press. Liverpool again usually have traps involving their full-backs in these areas, but because it is so high up, they don’t want to commit too many players that high. Because this first pass is free and play is fixed initially, it makes Liverpool’s blindside pressing runs less effective, and so this is much more available from goal kicks than from regular play.

We can see an example here of an asymmetrical structure used by Manchester City against Arsenal this season, where the use of a back two involving the goalkeeper allows for double-width to be created. As a result of this, we see the ball near striker for Arsenal is forced to arc his pressing run, while their full-back is forced high and wide against Cancelo. Rodri and Bernardo Silva take advantage of Arsenal’s man orientations and position themselves on the same side as each other to open a lane for Sterling to drop into. This structure ultimately creates space for Foden to receive a long ball and play from there, but again it is the positional play concepts that have a continuous knock-on effect on Arsenal’s decision making and therefore their structure.

Dynamic space occupation and more third man runs

We have already spoken about some uses of dynamic space occupation and third man runs, but there are many useful examples that show methods of progressing play. I mentioned Tim Walter’s sides earlier, and Holstein Kiel under 19’s have continued to use this same philosophy around dynamic space occupation, and we can see an interesting, simple scene from a goal kick below. Here you see those same principles regarding a back three stretching the first line, but now a full back inverts on the blindside of his marker, leading to him not being followed. Their structure pins the opposition midfield deeper, and so the pivot space is open for a free pass and progression is allowed. This may not always be possible at the highest level, but principles around full-backs inverting into space, as well as centre backs pushing on into an empty pivot space have shown to be effective.

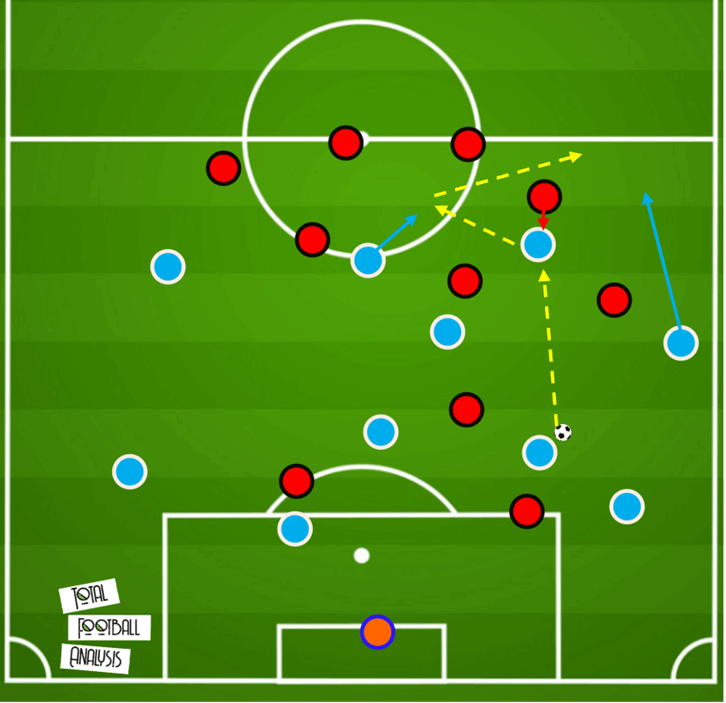

Huddersfield are a side this season that I have analysed and saw some nice dynamic space occupation and third man running. Below we can see an example of a goal kick from Huddersfield where their movements create a massive opportunity.

Play starts with the goalkeeper passing the ball to the right centre back in the box. The right centre back plays the ball into the full-back and continues his run to move past his marker and receive the ball again. While the centre back makes this run, a central midfielder previously occupying the half-space moves towards the centre to open the half-space lane.

The centre back receives the ball, and the half-space lane is opened thanks to the movement noted earlier by the central midfielder. The striker receives the ball, and the far central midfielder makes a run into space slightly behind and to the striker’s right (our left). This movement is timed well, and so he arrives onto the ball facing forward/diagonal. The right winger has continued a run, and so he can complete the third man concept. The far midfielder continues his run and gets the ball back again, before crossing the ball to the onrushing midfielders at the far post.

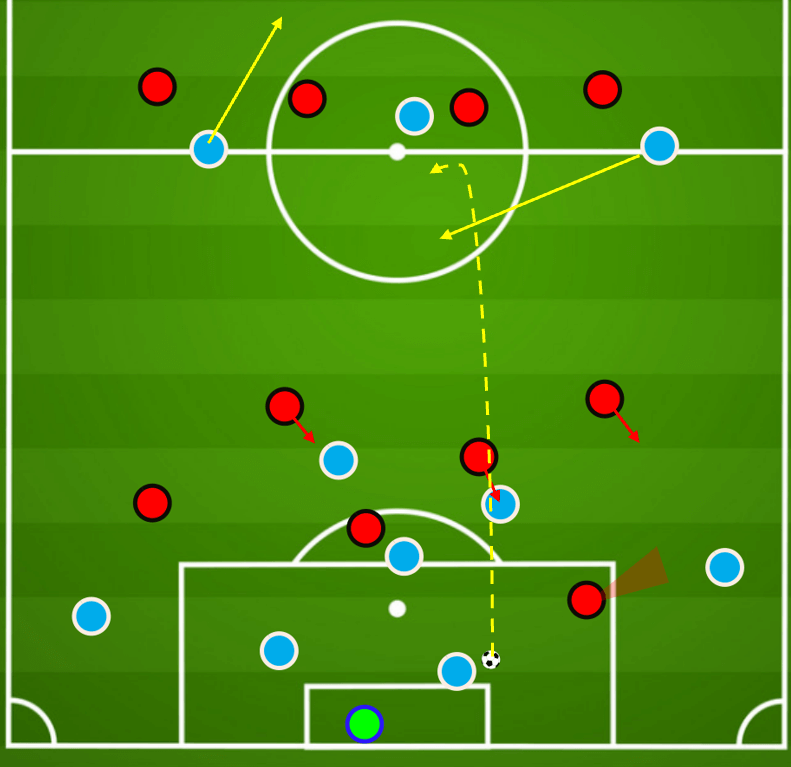

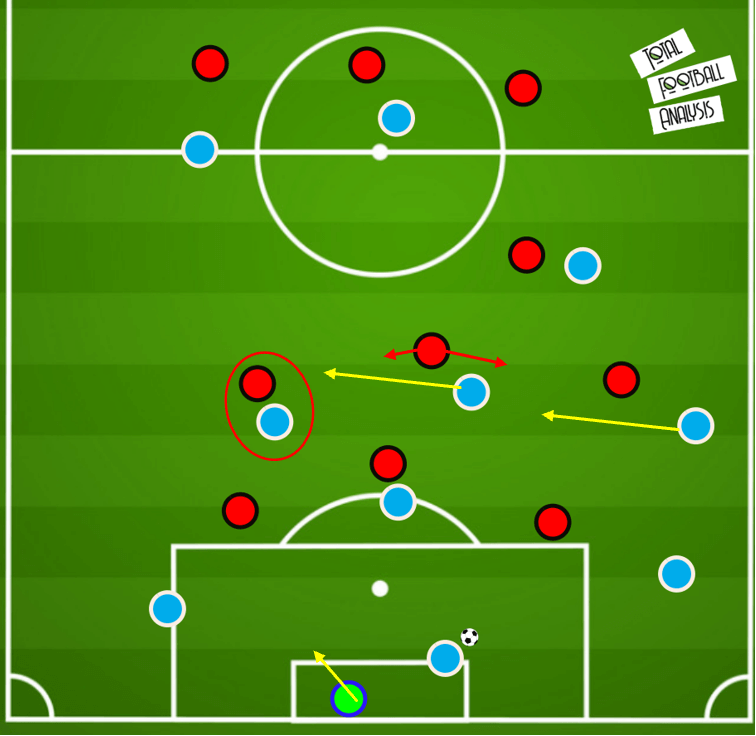

In the formation of this piece, I’ve also created some of my own ideas based on these principles outlined, and I have shared one such idea below, where dynamic space occupation is used to create an overload to win the second ball. The structure is based on that previous example of Manchester City vs Arsenal but can be applied elsewhere. The aim is to use the pivot space to force the opposition to act more zonally, essentially pinning players in place and not allowing them to follow players. The most central midfielder moves towards the wide area into space already occupied by an opposition player and teammate, with the aim being to create a 2v1. Because they are moving from a central area, and because of the use of double width, if their marker follows them, they would leave the central lane wide open for a pass, and so as a result most sides would likely allow the overload to be created. They possibly wouldn’t even see it as a threatening overload, due to a player already being there giving them almost a false sense of security.

This player drifts across to create the 2v1 and aims to be on the far side of the overloaded opposition midfielder when the ball is delivered long into a player. To win second balls, it is vital to win the race on that far side, and having a player given a head start naturally gives you an advantage. The opposite side wide player can move inwards to create a further decisional crisis for that red central midfielder, but this may not even be needed if the move is executed with the right timing.

Conclusion

This analysis has sought to investigate some of the strategies used by top teams from pressured goal kick situations in build-up. The largest trend from the piece seems to be the application of goalkeepers within a positional play structure, as well as teams constantly looking to use dynamic space occupations, or third man runs to progress or retain possession. Pressured goal kick situations against these teams are often quite rare as a result of these concepts coming to fruition, and so it will be interesting to see if more and more teams start to use interesting goal kick strategies, or if they are even given the opportunity. Sides lower in leagues could likely benefit the most due to teams often preferring to press against weaker in possession players, and so again as with anything in football, it will be about the risk and reward associated with these ideas.

Comments