Everything ends this way in France – everything. Weddings, christenings, duels, burials, swindlings, diplomatic affairs – everything is a pretext for a good dinner.

– Jean Anouilh, French playwright

Last night’s exciting Group A clash of the heavyweights: France versus Norway, left us with more to chew on that just our nails. Before us, in soaring temperatures and in front of an almost full Allianz Riviera crowd, we saw two sides competing in the 2019 World Cup’s most exciting tactical battle to date.

In this tactical analysis, we shall see how this game was split between a tactical chess match which Norway bettered before France’s natural flair managed to deliver two knockout blows in the second half. Fans will argue that France benefitted from VAR. Yet, this does not take away from the fact that France’s attack earned the opportunity to be kneecapped by Ingrid Engen in the penalty area. Norway’s own tactical ingenuity was bold enough to deserve a result, but their last-minute tactical rearrangements only managed to expose concerning trends within their World Cup squad.

Tactical Analysis – Line-ups and shapes

The French decided to keep things relatively familiar going into the game, and retained their usual 4-2-3-1 formation. Despite this though, there were some minor variations in how this system was deployed, as well as some interesting changes to playing personnel.

Following France’s 4-0 hammering of South Korea in Paris almost a week ago, one could have assumed that Corinne Diacre would have allowed the occasion and the hysteria bubbling inside the stadium, to get the best of her. We should have known better from this wiley manager, however. Her side’s shape didn’t see any major changes.

A perhaps expected change saw the eventual player of the match, Valérie Gauvin, move into replace Delphine Cascarino. By doing this, Gauvin took up the role of a dynamic centre forward. She is athletic, and her usual channel runs were designed to add an increasing amount of forward runs to the attack. Kadidiatou Diani, who led the line against South Korea, was moved to the right side, to enable overloads in this area behind the Norwegian left-back.

With regard to tactical surprises on the other side of the pitch, Martin Sjögren stamped his intent on taking Norway all the way, by really mixing up his tactical options. Changes in their starting XI from the side that faced Nigeria pre-determined some significant changes in their style of play.

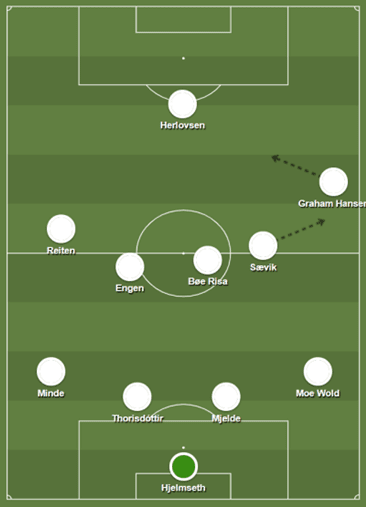

An unchanged defensive line, resting on a strong defensive core with two usual flying wing-backs, were covered by the usual pivot in the middle of the field of Ingrid Engen and Vilde Bøe Risa. Karina Sævik, an all-rounder with excellent abilities in both attack and defence, was positioned slightly to their right.

Whilst it could be argued that Norway started in a 4-5-1, with Carolina Graham Hansen positioned on the right side, this was an ingenious foil. With Sævik able to shift across, Hansen was given license to drift into the middle of the park, assisting Isabell Herlovsen up front with regularity.

The first half: Norway look to speed up their attack

In terms of how Norway’s new shape altered their attack, this tactical analysis will demonstrate that they hoped to speed up their attacking play. In order to do this, Graham Hansen’s positioning would be vital. By moving across from the right side for attacks, Norway were hoping to mash together the second and third stages of their usual attack.

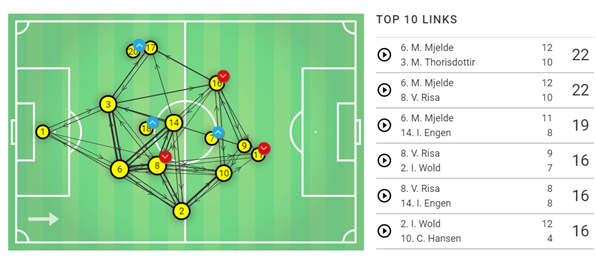

Generally speaking, Norway’s attack encompasses three distinct phases. Firstly, there is a patient build-up from the back, utilising Engen and Bøe Risa’s ability to move the ball forwards. Secondly, Reiten and Graham Hansen on either flank tuck-in, allowing space for the full-backs to push forward. A ball to the centre forwards usually finds these two inverted wingers. Finally, a ball is then played into the wide areas for a cross. The below pass map shows the average positions for Norway’s stars when moving the ball.

However, Sjögren clearly understood that Norway needed to be fast on the break, as they would expect to face long periods without the ball, and would need to hit the French quickly and by surprise. Counter attacks are not usually part of Norway’s game, although Sjögren would know that his side could be effective with it.

Against Nigeria, they recorded only one counter-attack, although this did lead successfully, to a chance on goal. Furthermore, a success rate of nearly 69% of their forward passes hitting their target, would be grounds for encouragement.

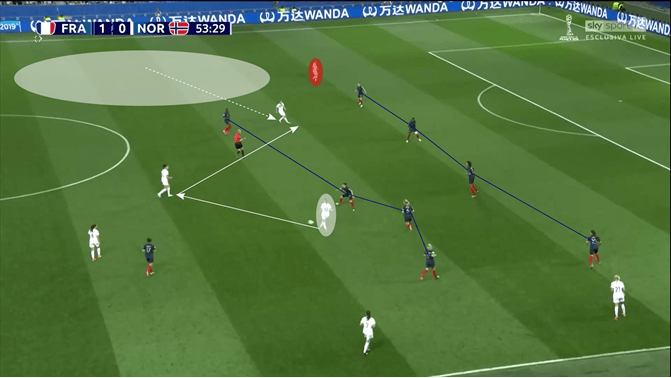

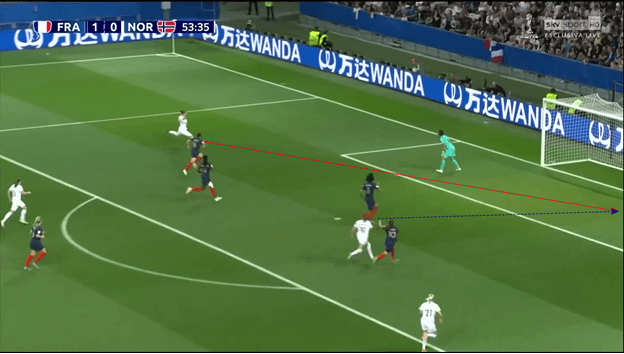

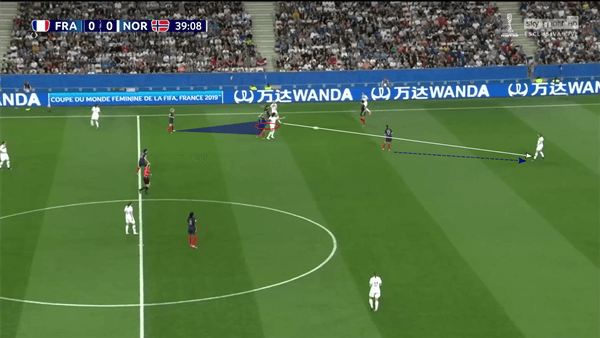

Width would be needed straight away, and with Guro Reiten and Kristine Minde on the left, with Ingrid Moe Wold and Sævik already on the right, Hansen could have plenty of options should she received the ball in the middle of the park. Whilst fans had to wait until the second half to see this tactic work, they were rewarded with a fantastic shot of this in action:

France keep their shape compact

Unfortunately for the Norwegian’s, however, France are miserly when it comes to conceding. Against the Koreans, France conceded just 0.06xG. The Koreans had just four shots, none were on target, nor had any real threat. Whilst four goals in their game against South Korea became the major talking point, it was this other side of the scoreline which reigned in significance in Nice.

In the first half, Les Bleus were dominant in attack but they still managed to see off Norwegian advances, usually on the break. This was ensured through quick transitions into a tight, compact defensive 4-4-2, with a high-mid block, when the ball was lost.

Naturally, however, there were limiting factors for the French attack which sprang from this conservatism at the back. For one thing, we really failed to see the French exploit some of their attacking nous in a really dynamic way.

Whilst Amandine Henry could still make lung-bursting runs forwards, there was always a caution that meant her space in midfield would need to be corked. Throughout, Henry looked to sit slightly more than she hoped to attack, aware that Graham Hansen would be lurking in the space behind.

As France’s attacking credentials really came into play, we could see how Henry was crucial to re-establishing equilibrium within the side. She would often continue to pull deeper, essentially setting up defensive triangles whenever Norway threatened down the flanks. This would then become a crucial catalyst for beginning France’s famed high press. This would be important in starting the attack which won the penalty.

This did not detract away from a very determined French press high up the field. To their credit, Engen and Bøe Risa did well to often negate this by sitting deeper and looking to shift the ball out of danger. All the same, however, it often proved too strong to penetrate, particularly as they were gradually squeezed into corners. By the second half, this press became even more determined and played a role in the controversial penalty decision, which settled the game.

The second half: the fall of the Bastille

The second half was when we really began to see the foundations of each side, so artfully crafted by Diacre and Sjögren tumble down – much to the fans’ relief. Diacre perhaps acknowledged that she had underestimated her counterparts’ ability to create major tactical shifts in his side in such a short space of time. She realised that the only way to beat such a rigid and disciplined side was to embrace ingenuity and individual flourishes of ability.

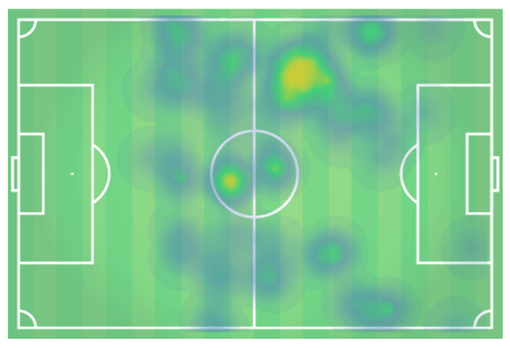

Wing play has been a hallmark of France’s attack under Diacre, and the first half by no means showed any sign of that ceasing. Yet, France’s first half lack of variation was surprising. Before the break, France almost attacked exclusively down their right-hand side.

Two of their most decorated attackers, Eugénie Le Sommer and Amel Majri, were often left covering the more central players, or usually left in space, with France being unable to switch the ball across. This is surprising, as Majri, for instance, has average nearly five crosses per game for both club and country. From the first half, however, this number would have looked inflated. The below graphic shows how crucial the left side was in their recent victory over South Korea:

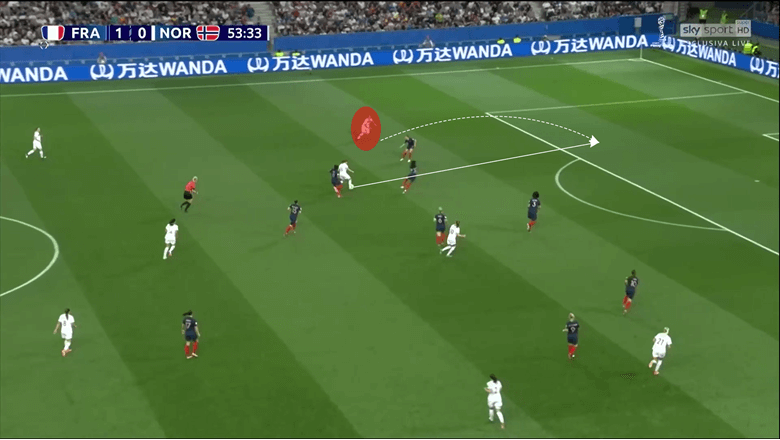

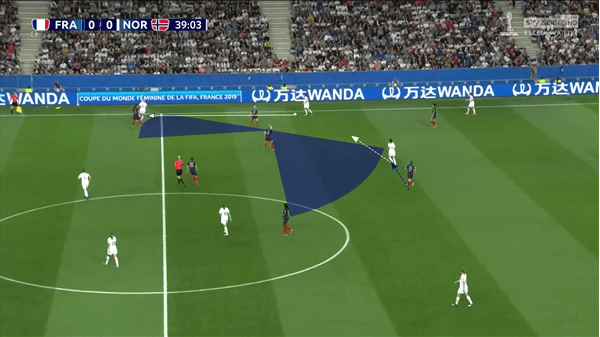

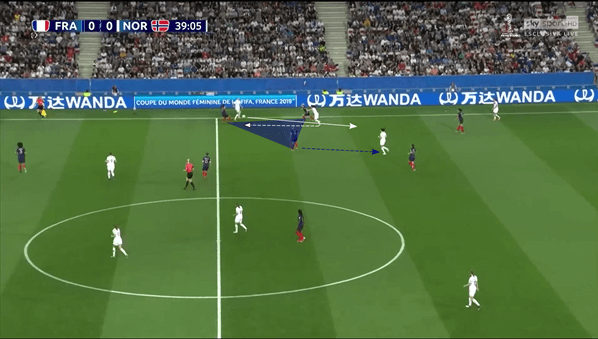

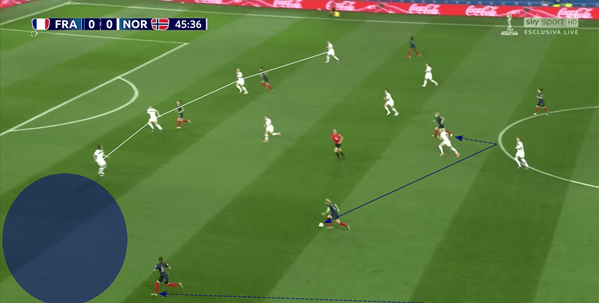

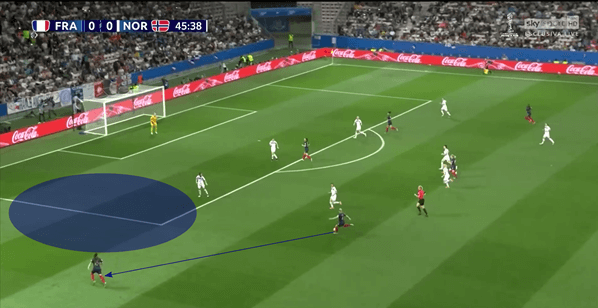

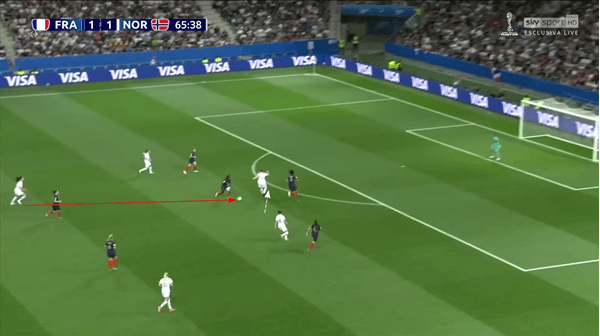

Notably, both of France’s goal’s found their point of origin through crosses from the left-hand side. The first example, was classic French attacking at work, with Majri providing a delectable cross which just needed to be steered home. This is shown in the graphics below:

The reasons for France’s pre-second half reticence to attack in numbers largely fall at the feet of Diacre, over any brilliant Norwegian tactical blocks. France looked to just be cautious and were aware of an attack on the break. Perhaps withdrawing Henry demonstrated to Diacre that she could soak up pressure, and thus both full backs could push on after half time.

Norway unable to optimise the full backs

France could afford to do this in the second half, as it became largely clear for Diacre that the Norwegian full-backs themselves, were having trouble coordinating their positioning. Interestingly, even after Sævik was withdrawn for Marie Karlseng-Utland and Norway resorted to a much more familiar 4-4-2 in attack, they were still unable to utilise this.

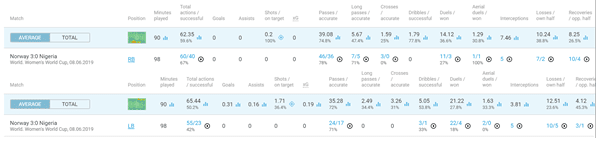

Worryingly for Norway, and especially when we look at their Moe Wold and Minde’s statistics from against Nigeria, we can see that they are not hitting the figures that indicate strong play on their parts. Below, we can see their statistics from the game against Nigeria. Whilst Moe Wold’s look stronger, we have to understand that she play’s from a much more subdued decision, which offers little in attack.

The first such reason for this was how well France defended. In his preview analysis, Abdullah Abdullah drew attention to how we should expect France to essentially play six at the back, with their wide players sitting slightly wider and ahead of their full-backs, who had pulled into the centre. In reality, France were slightly more cautious than this, keeping Henry back in the centre too. This was designed to get Norway to try and switch play. This was essentially entrapment of the highest order.

The second reason for Norway’s inability to properly engage their full-backs, however, was much more due to the lack of their usual overlapping triggers. The Norwegian’s usually attack like clockwork; they’re mechanized and sometimes, a little too predictable. The wingers, often Hansen and Reiten, pull into become inside forwards. This then signals for the full-backs to move within the final third and receive a pass for a cross.

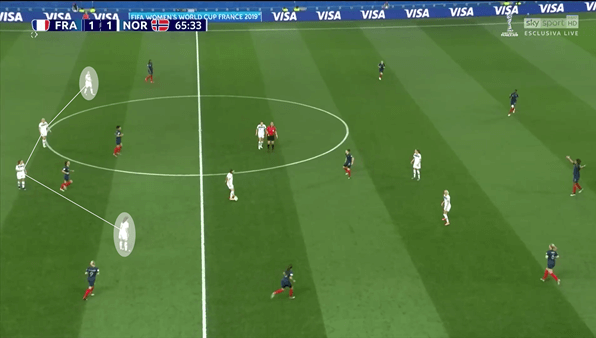

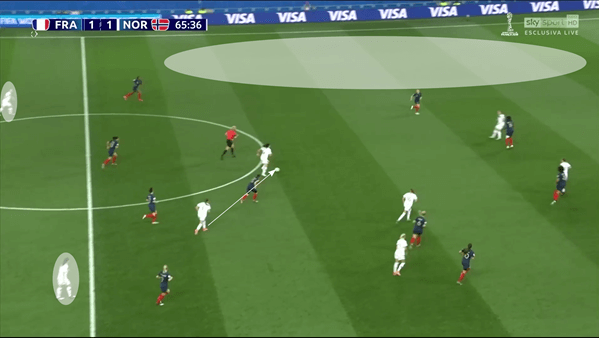

Last night, however, by packing the midfield earlier, the full-backs did not appear to realise at what point to make these pivotal runs. Often, they were simply sat waiting behind the ball, and chances would then go begging. A crucial example of this can be seen below:

Conclusions

France were always going to go into this game as favourites, and just like any high-stakes competition, it would be a case of who blinked first. We should have expected it would have been the Norwegian’s to feel the need to adapt, as Sjögren more or less stated that he would do so prior to the game. At the same time, his changes were remarkably bold and were not just obstinate defensive strategies. He clearly looked to build attacks faster. This did produce additional defensive ramifications, but at the same time, the Swede was not willing to sit out a 0-0 draw.

On the flip side, it would be incorrect to say that Diacre did not fear the threat the Norweigian’s would lay at their door. In front of a capacity crowd, baying for blood and demanding nothing less than a victory, Diacre also mobilised her troops to be wary. But this was largely to shore up concerns which the Norwegian’s could bring, and nothing more. Their full-backs remained deep, and their forwards moved into channels. What became apparent, however, was that by loosening up, France had the individual quality already pre-programmed in their minds to win.

Comments