Lisandro Martinez has had a difficult start to his Manchester United tenure. We’ve all seen the memes targeting his size and, sure enough, there have been some issues with opponents targeting him.

But football has a rich history of undersized centre-backs. One of the poster boys is the Englishman, Bobby Moore, who stood at 182 cm tall. The legendary, two-time Ballon d’Or winning German, Franz Beckenbauer, was 180 cm tall and fellow Ballon d’Or winner Fabio Cannavaro also stood at just 175 cm tall.

Defending against flighted balls and tussling with target men are not new concepts. They’ve been around the game for generations, if not from the start. While the game has evolved, football’s rich history not only points to several great, undersized centre-backs, but it also shows us the best centre-backs in the history of the game are considered short.

This tactical analysis goes out to the centre-backs who stand at 186 cm or shorter. We’ll look at the vulnerabilities faced by this specific player pool and show how top undersized centre-backs in the modern game use their size intelligently, consistently gaining an edge on the opponent.

Vulnerabilities

The transition to Manchester United simply hasn’t gone as planned for Martinez. Though his centre-back pairing offers the height that Martinez lacks, opponents have consistently targeted the 175 cm player. Placing a target forward against him and sending a runner underneath or behind, opponents have been able to win the first and second balls rather easily. They’ve also attacked him on set pieces.

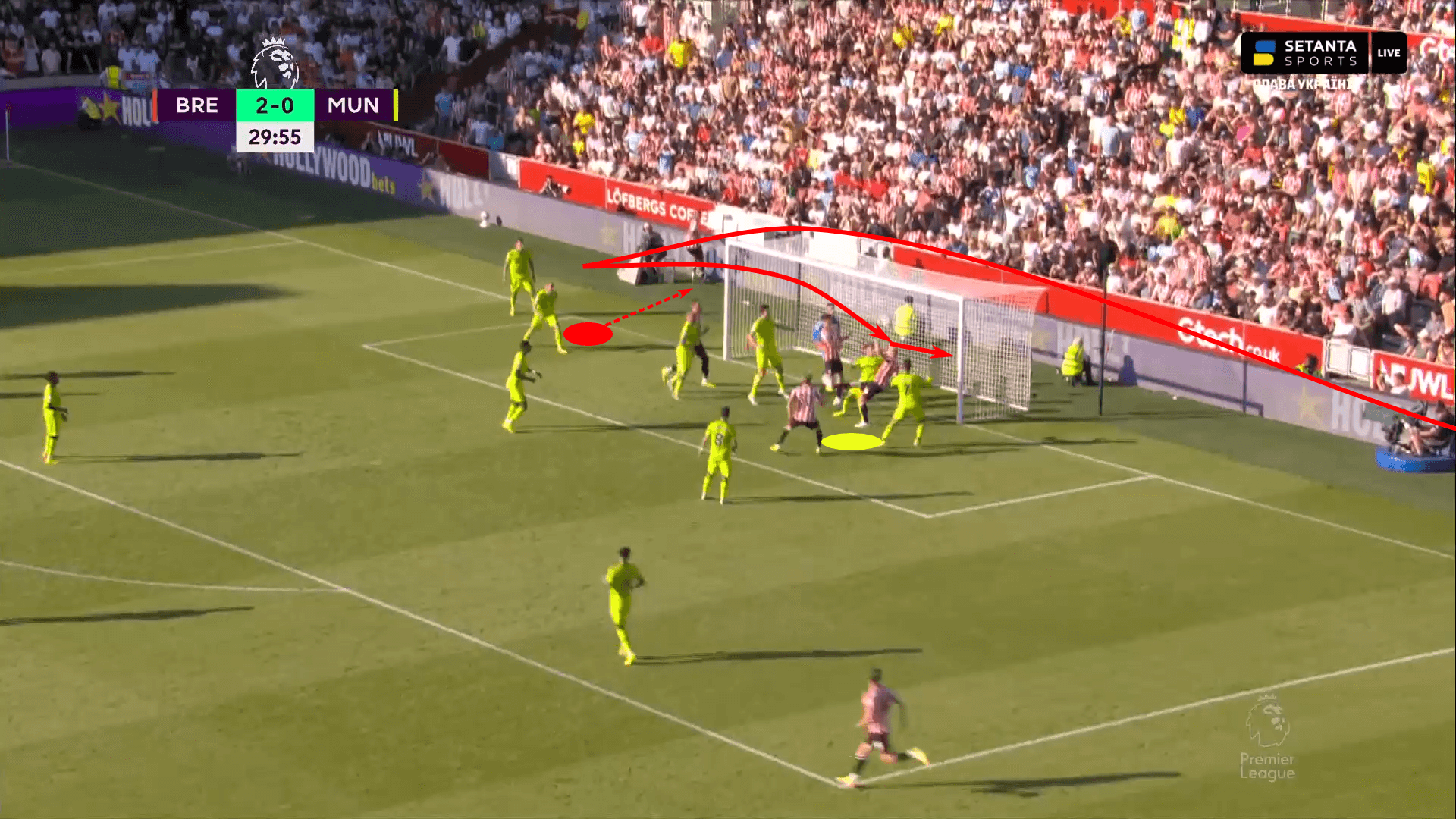

And that’s where we get the first vulnerability of short centre-backs, their disadvantage in the air. Let’s start with the most glaring, recent example, the Brentford corner kick goal.

Physical mismatches can be planned around just as much as they can be exploited by the opposition. On the Brentford corner kick goal against Manchester United, marking assignments are the first questions raised. Maybe this is an example of the opposition targeting an undersized player, but it was clear to see Martinez was overwhelmed by the assignment.

Again, coaches can plan their tactics, especially in set pieces, to avoid physical mismatches. However, when one of your centre-backs is undersized, your team is missing a player who is typically among the tallest on the pitch. Say, that instead of Martinez, Manchester United had Varane and McGuire on the pitch at that instant. Odds are this goal isn’t happening. Each of those players has the size and physicality to win the duel.

There’s a little more leeway on set pieces to hide smaller players or give them roles that delay the opposition’s timing or disrupt their balance, but that’s trickier in the flow of play. If the opposition has a large striker or two sizable centre forwards, they can typically determine which matchups they’d like to exploit.

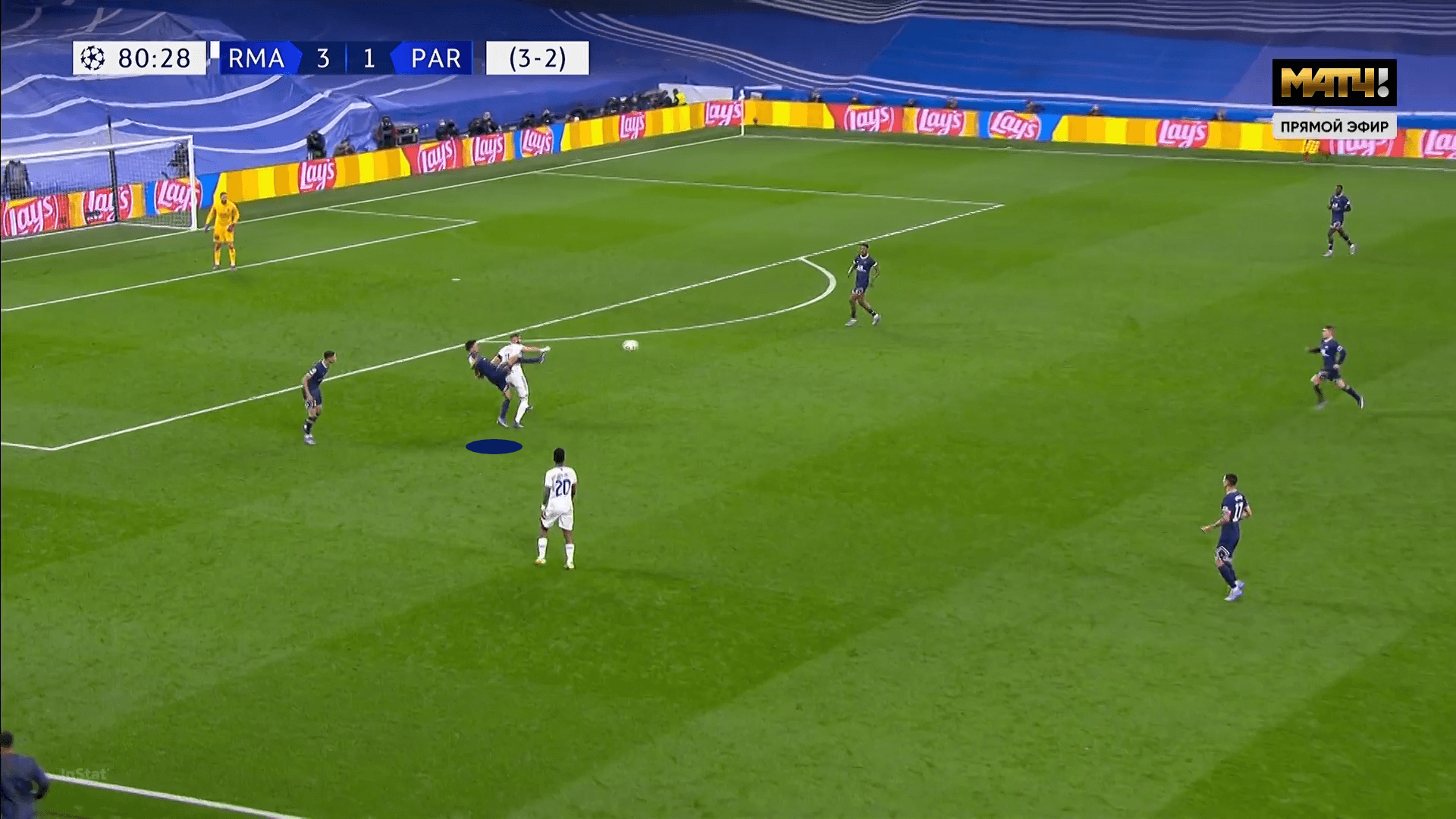

Last season during the Champions League, that’s exactly what Real Madrid did against PSG. Putting Big Benz up against Marquinhos, the Spanish side was able to use the Frenchman’s physical dominance to use him as a target man. Playing with his back to goal, Benzema was able to post up against Marquinhos and drive him away from the incoming passes.

You can see Marquinhos struggling with the physical battle. He’s off balance and falling backwards. His only hope is the desperate attempt of his extended leg to make enough contact with the ball to keep the Ballon D’or favourite from retaining possession or setting back to his teammate.

Notice Vinícius Júnior just underneath Benzema. It’s a perfect setup to win the first and second balls.

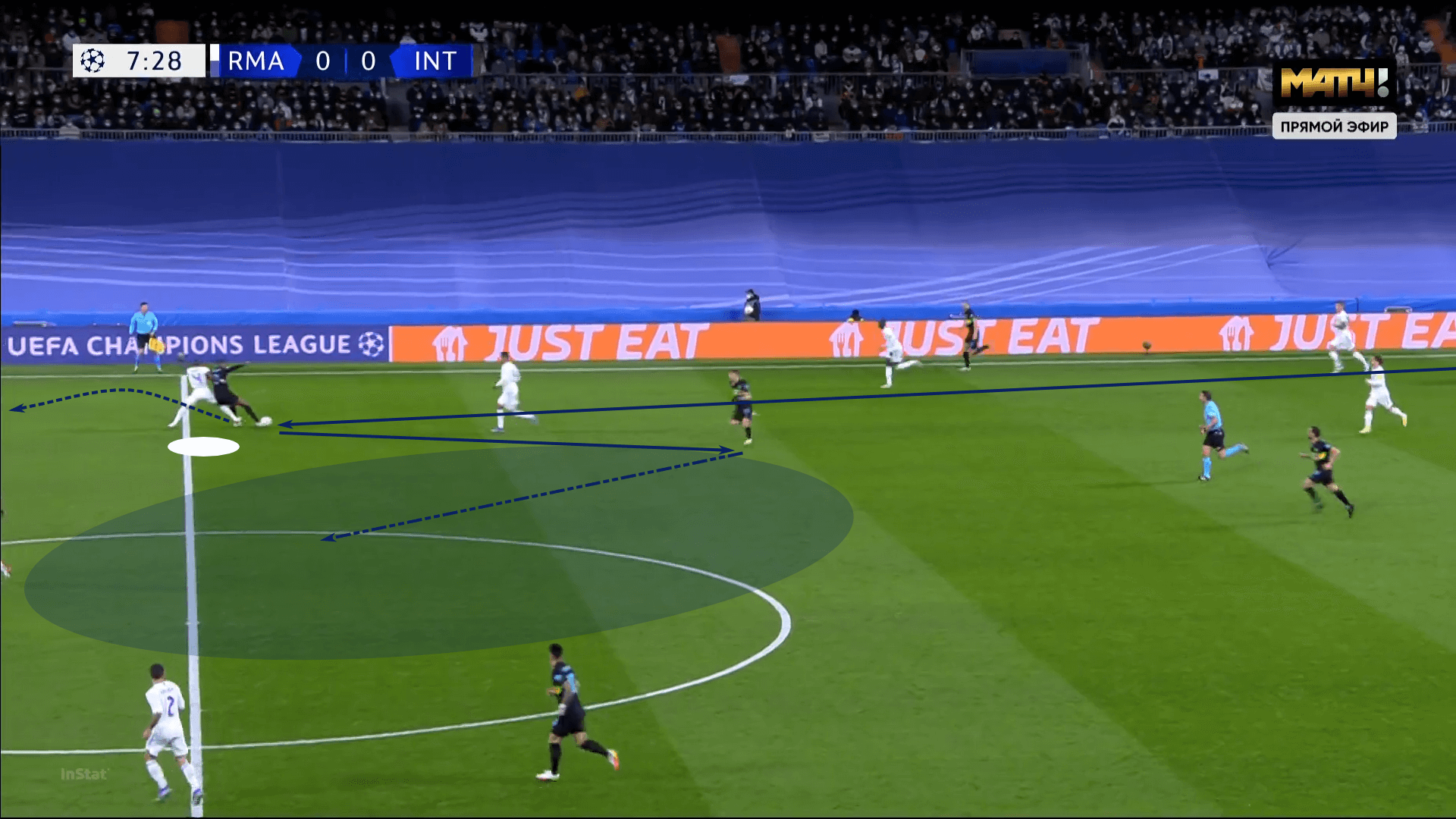

The ball doesn’t necessarily have to arrive in the air either. David Alaba, who stands at 180 CM tall, was asked to defend a bouncing ball with an opponent just in front of him. To his credit, Alaba does well to put the Inter Milan player off balance. However, the Austrian is also overextended. He lost the duel and two steps as his opponent was able to recover his balance quicker and run behind Alaba.

Though he nearly gets to the ball, Alaba’s reach isn’t quite long enough to get a touch. He is a physically strong athlete, which was enough to keep him from getting turned, but it wasn’t enough to make contact with the ball or force his opponent into a poor touch.

The last vulnerability we’ll discuss is both a blessing and a curse. Undersized centre-backs tend to gain an advantage through their mobility. They’re typically more agile than their larger opponents and often faster. Those are two of the primary reasons they’ve managed to remain at centre-back. With those advantages, they tend to cover ground really well. This includes stepping into midfield, which we see in the final example from the section.

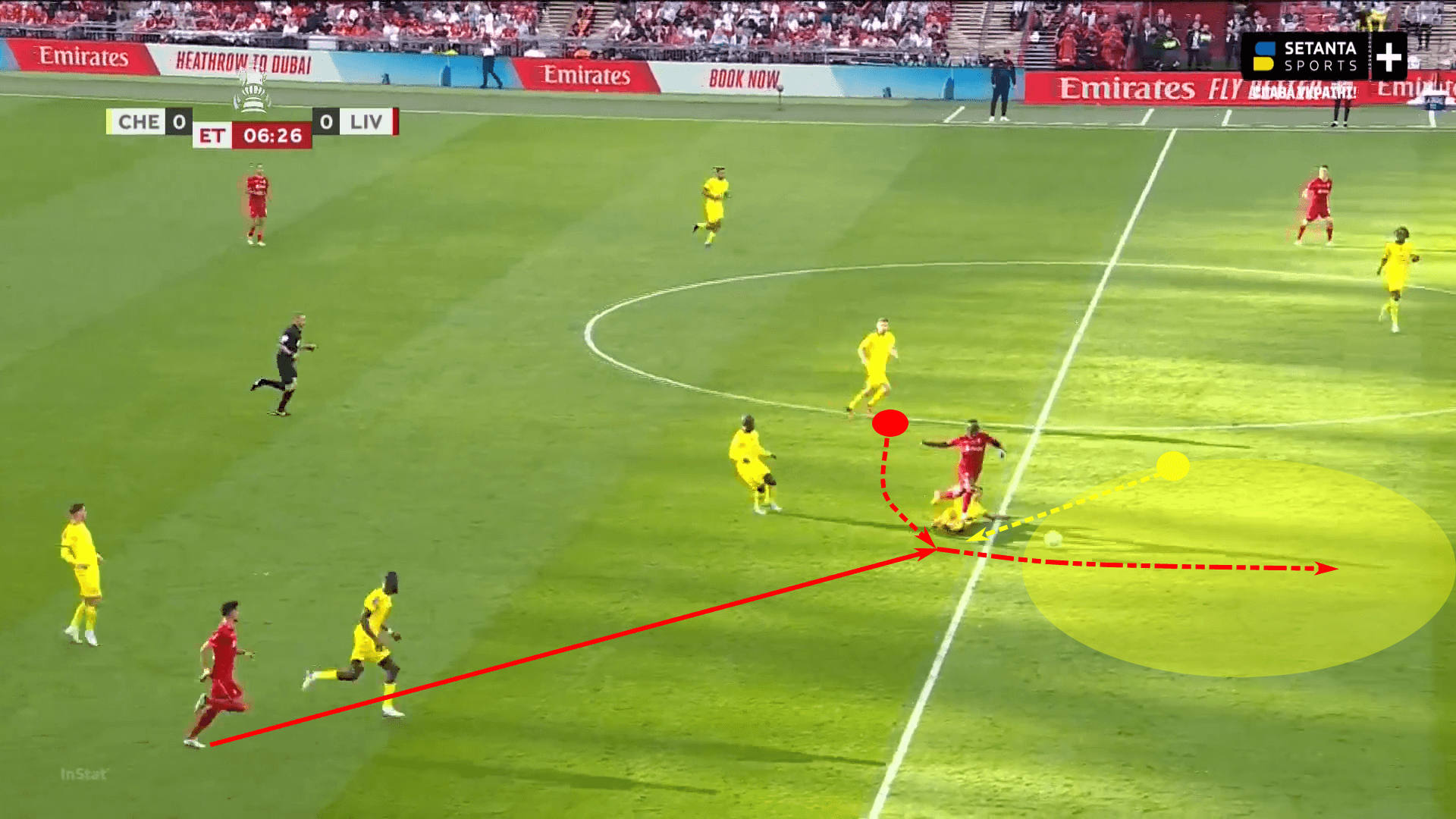

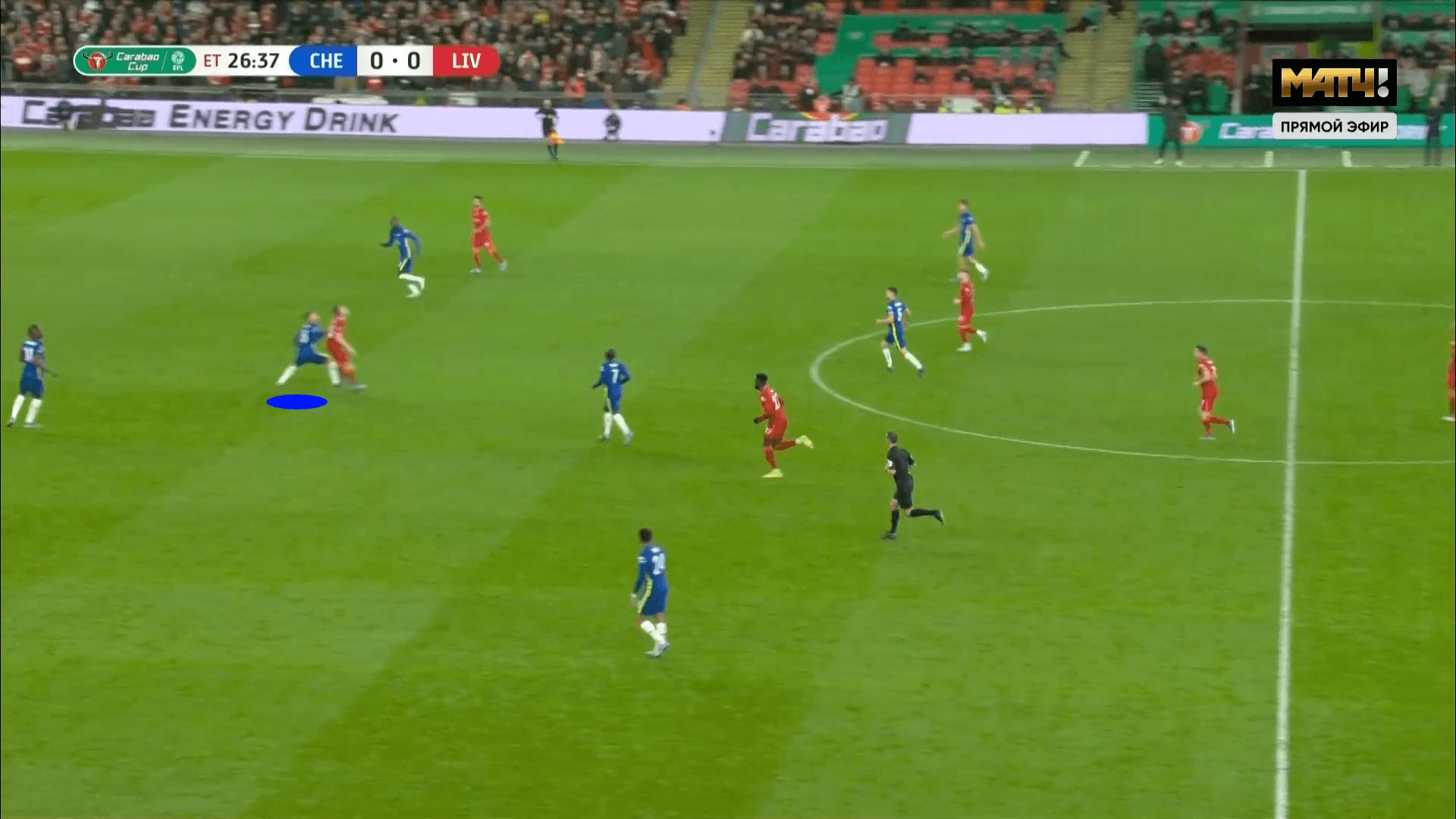

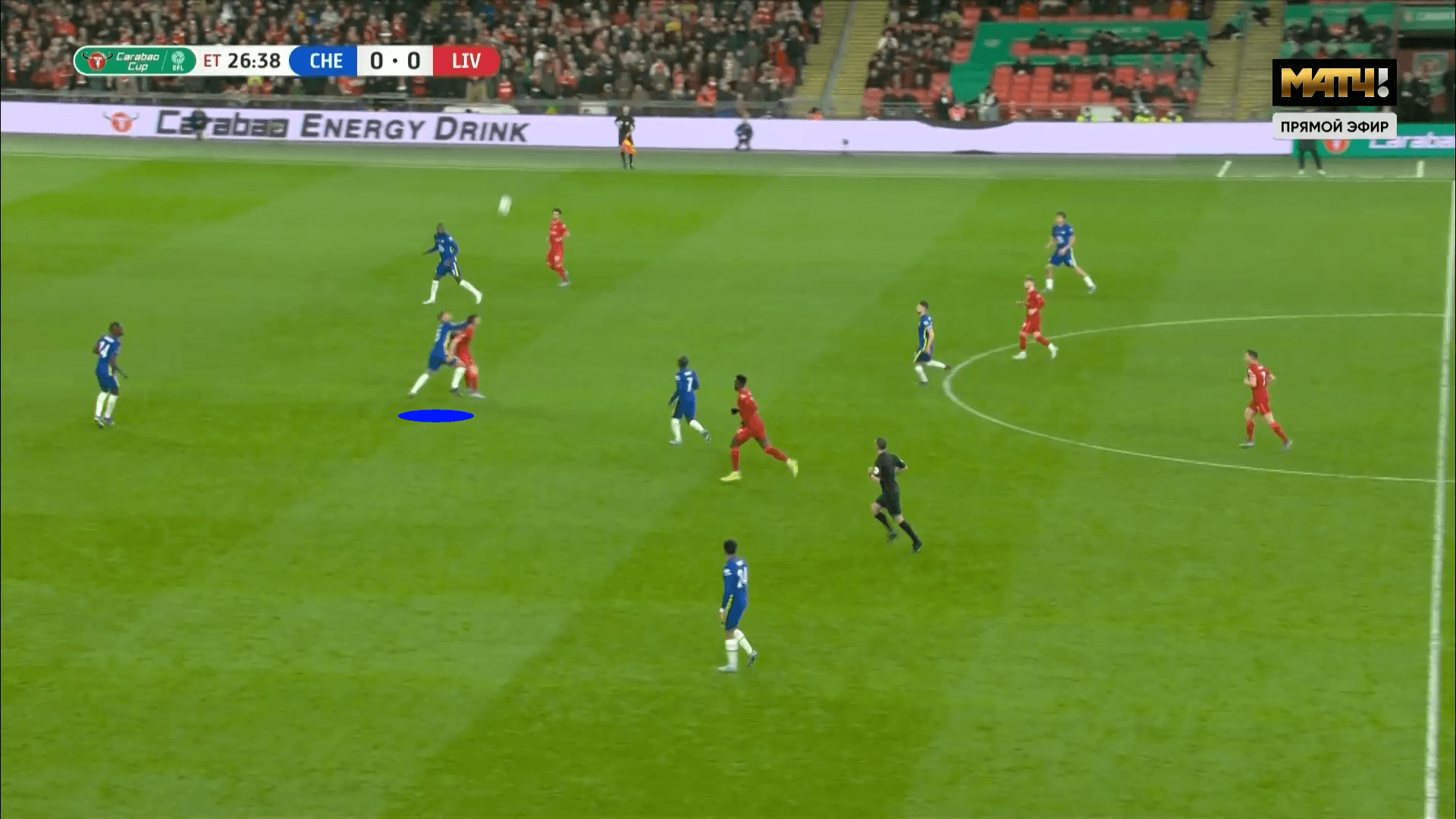

Chelsea’s Thiago Silva is one of the most intelligent centre-backs you’ll find. He has also had one of the most outstanding careers of his generation. But the cup match against Liverpool gives us a moment that serves as a warning to centre-backs who move aggressively into midfield.

Luis Díaz played into Sadio Mané, who was on a collision course with Silva. With the ball played just in front of the Brazilian, he took the cue to rush into midfield and attempt a sliding challenge. However, Mané was quicker to the spot and took a tidy touch around him.

Those aggressive movements into midfield are a blessing because centre-backs can often end a threat before it fully matures. The curse is the overconfidence that comes with the high success rate. When facing a club like Liverpool that has loads of pacey, agile forwards, undersized centre-backs have to adapt their game to account for the fact that they may not be the quickest or fastest players on the pitch, at least from a physical perspective. The opponents’ speed and quickness forces centre-backs to re-evaluate their timing. If you’re a split second ahead of a big, lumbering #9, you can typically get to the ball uncontested. Against a forward like Mané, that split-second anticipatory advantage can become a split-second disadvantage because of the opposition’s pace. Knowing the opponent and adapting to their skill set are critical.

So these are the main vulnerabilities we’ll address. We want to look at how undersized centre-backs deal with aerial duels, larger target players posting up against them, and maintaining that advantage moving into midfield. Let’s start with aerial duels.

Dealing with aerial duels

This section will be a little less tactical theory and a little more scout report on the techniques short centre-backs use to gain the upper hand on their physically advantaged opponents.

When it comes to aerial duels, positioning is key. Before the players even go up for the ball, a battle is taking place. It starts with the two players reading the trajectory of the ball and getting close to the anticipated endpoint.

We say close because the battle has only begun. As the two players slide close to the landing spot, the physical battle starts. The universal truth is that each player is trying to block the other’s path to the ball’s endpoint. That’s as true for Martinez as it is for Virgil Van Dijk. The only difference between the two is that the Liverpool star has much more leeway given his height. He can high point his header at an earlier spot on the ball’s downward trajectory, which makes it increasingly difficult for his opponents to win the aerial duel.

Undersized centre-backs don’t have that luxury. Blocking the opposition’s path to the ball’s landing point is all the more important. That’s exactly what we see in this first example, featuring Chelsea’s Silva.

One of the keys to winning this aerial duel is the way he blocks Diogo Jota’s backward movement. But that’s not the only key to this aerial win. Look at the postures of the two players. Jota’s centre of gravity is behind his feet, limiting the amount of force he can apply to Silva. Meanwhile, the Chelsea centre-back is in a balanced position with his knees bent and a forearm in Jota’s mid-back. In fact, Silva’s knee bumps into the back of Jota’s knee, making the knee buckle. This is part blocking the opponent’s path to the ball and part putting him off his balance with the contact. It’s textbook defending.

As the moment to jump arrives, it’s very important to note that Silva goes first. Not only does he jump first, but his right forearm slides up Jota’s back. That gives Silva more leverage for his jump and also prevents the Portuguese from getting in the air.

If you’re speaking to the computer screen and pointing out that this is a foul, it’s a good time to remind you that it’s only a foul if the referee catches it. Silva does well to disguise his action, not making the contact obvious by putting open hands-on Jota’s back or shoulders, as well as making sure he doesn’t jump over his opponent’s back. These subtleties set top defenders apart.

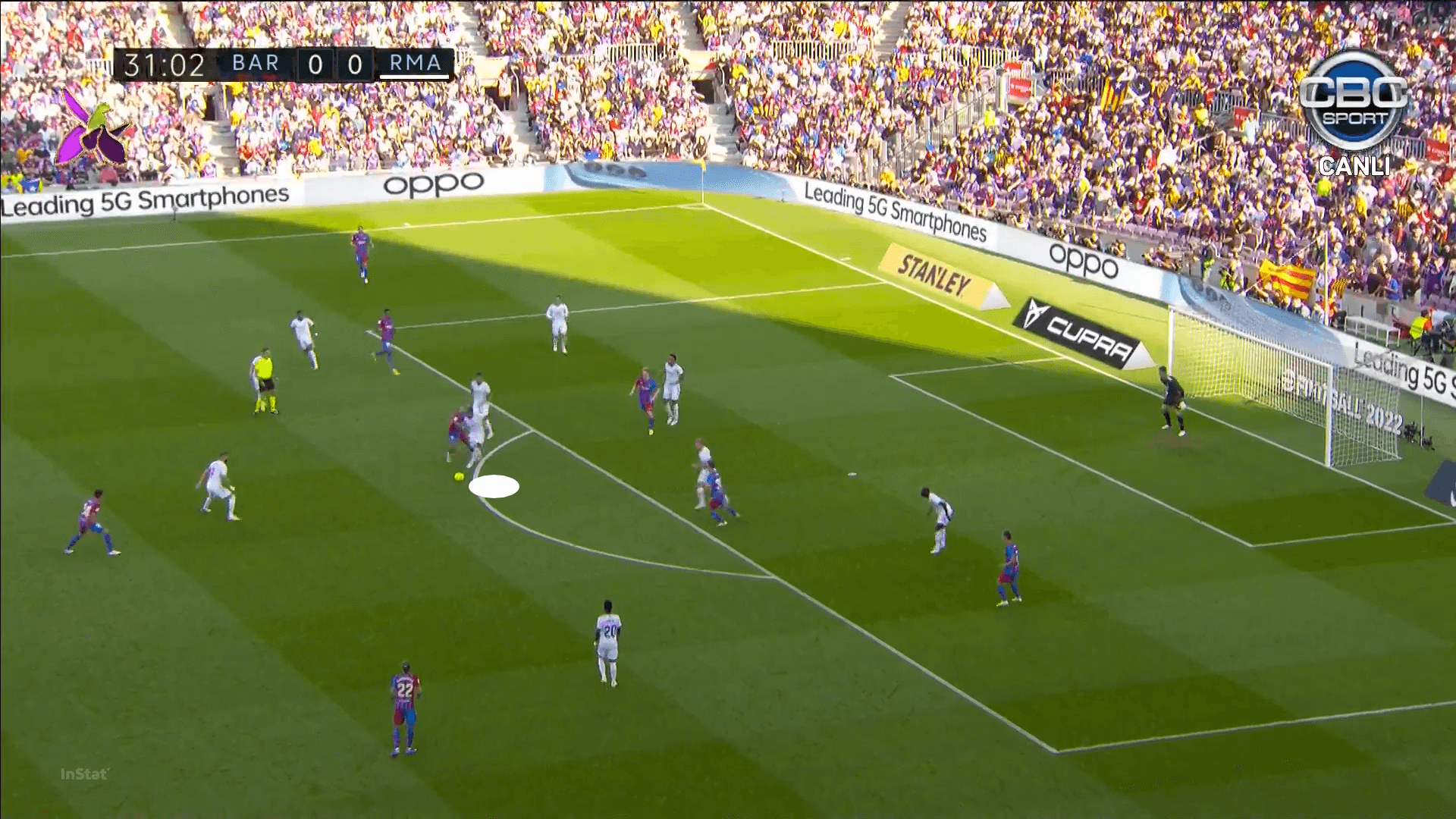

Even if the aerial duel is contested, all is not lost for our small centre-backs. Take this next example of the Barcelona signee, Jules Koundé.

We see Koundé’s extraordinary athleticism right away as he leaps significantly higher than his opponent. His vertical will help him, but we have to take note of another tactic in this example. Much like Silva, Koundé does jump first. Again like Silva, Koundé has used his arms to gain an advantage. The difference is in the timing and location of the contact.

Whereas Silva quickly slid his forearm up to the shoulder blade area, Koundé leaps slightly into the opponent and gets his forearm out. Part of that is to improve his vertical reach through good jumping technique. The other angle is that the extended forearm is intended to make contact with the opponent. As he attempts his jump, his back will inevitably make contact with the opponents outstretched arm, limiting the remainder of his jumping reach. Subtle but clever.

The final concept we’ll look at is closely connected, but the approach is slightly different. If the aerial pass requires the contending players to cover an extended amount of ground to reach the ball’s endpoint, undersize centre-backs can help themselves tremendously by developing their read of the ball’s trajectory and responding before the opponent.

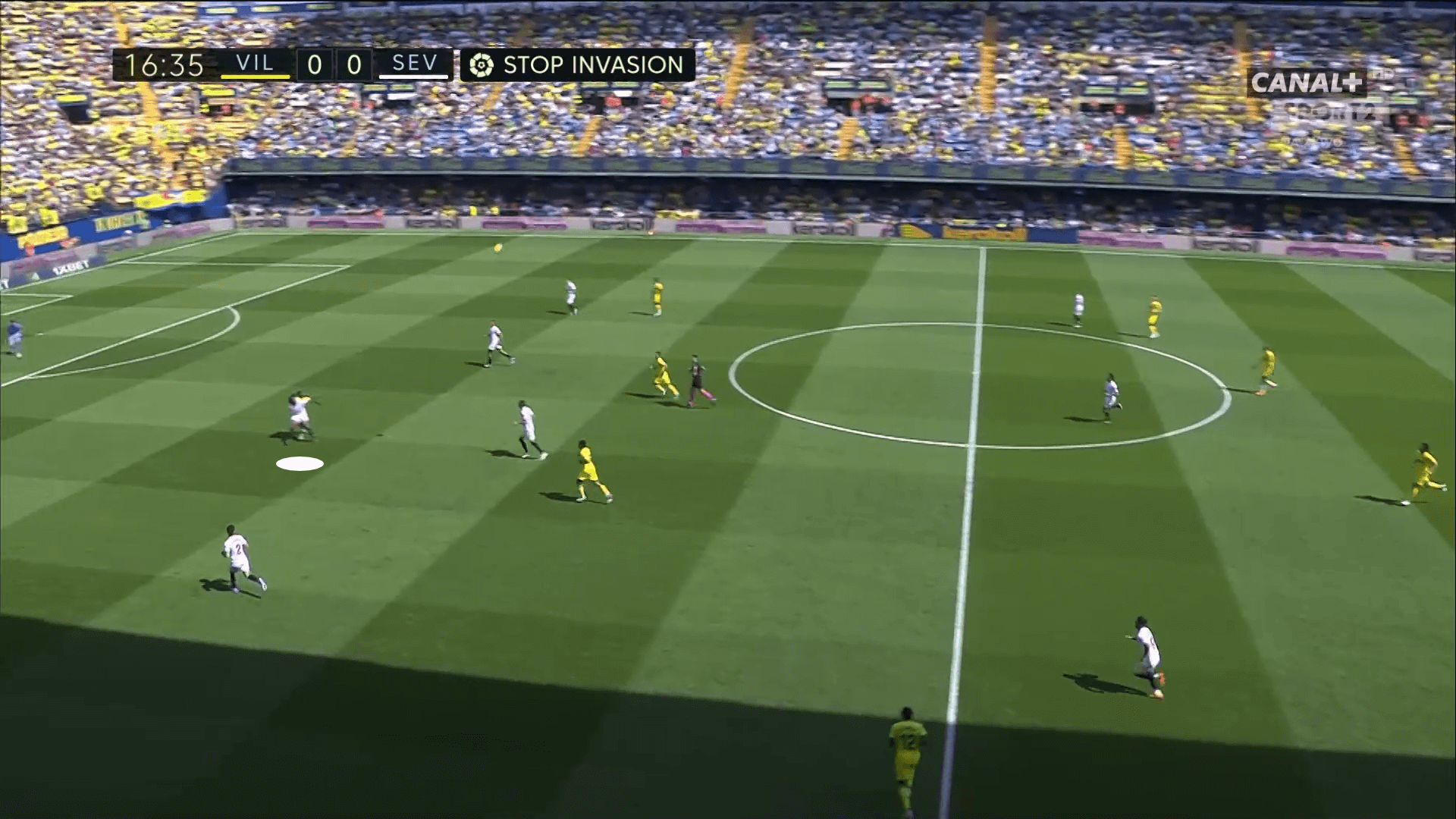

In this Koundé example, he manages to get to the location first. But, as he arrives, he does stop just short of the anticipated endpoint. Rather than getting to the correct location right away, he delays his approach at the very end. But why?

Notice that he is not only arriving at the spot at the last possible moment, but he’s also holding off a challenge from the Villarreal forward. That physical contact lets him know exactly where the opponent is and how he intends to get to the anticipated duel location.

Had Koundé immediately run to the spot, his opponent could have used a technique similar to the ones we’ve described to push the former Sevilla centre-back out of position. Instead, Koundé leaves that space unoccupied while prioritizing the physical duel. If he can keep his opponent from establishing position, the aerial win is a given. That’s exactly what happens. He fends off the opponent and launches a powerful header upfield.

If there is a recurring theme in this section, it’s that the physical battle precedes the aerial duel. Establishing positioning and manipulating the opponent’s balance in or during the aerial duel is critical for success. While that’s not specific to undersized centre-backs, it’s another instance of something slightly more important for them simply because there is so little margin for error. They simply can’t get to the anticipated endpoint and bully the opponent to claim the win. The aerial duel is decided before the ball even arrives.

Awareness and aggressive actions

Much like the previous section, we’ll address universal topics of defending here. What makes these so important for short centre-backs is that margin of error that was just mentioned. Make one mistake and the consequences are often more severe.

So, as we address awareness and aggressive actions, which will revolve largely around both dynamic movements and physicality, these are ideas that larger centre-backs can and should use, but, once again, typically deliver larger consequences to the undersized centre-back who gets it wrong.

The first trait we’ll look at is anticipation. Again, a universal skill for all players, especially for those at the end of the formation. Understand the threat and your odds of ending it improve. This is especially important for small centre-backs, who typically play in teams with high lines. Mobility is a key trait for undersize centre-backs. They’re not suited for low-block defending, but they are often the best candidates for teams that defend primarily through a high press.

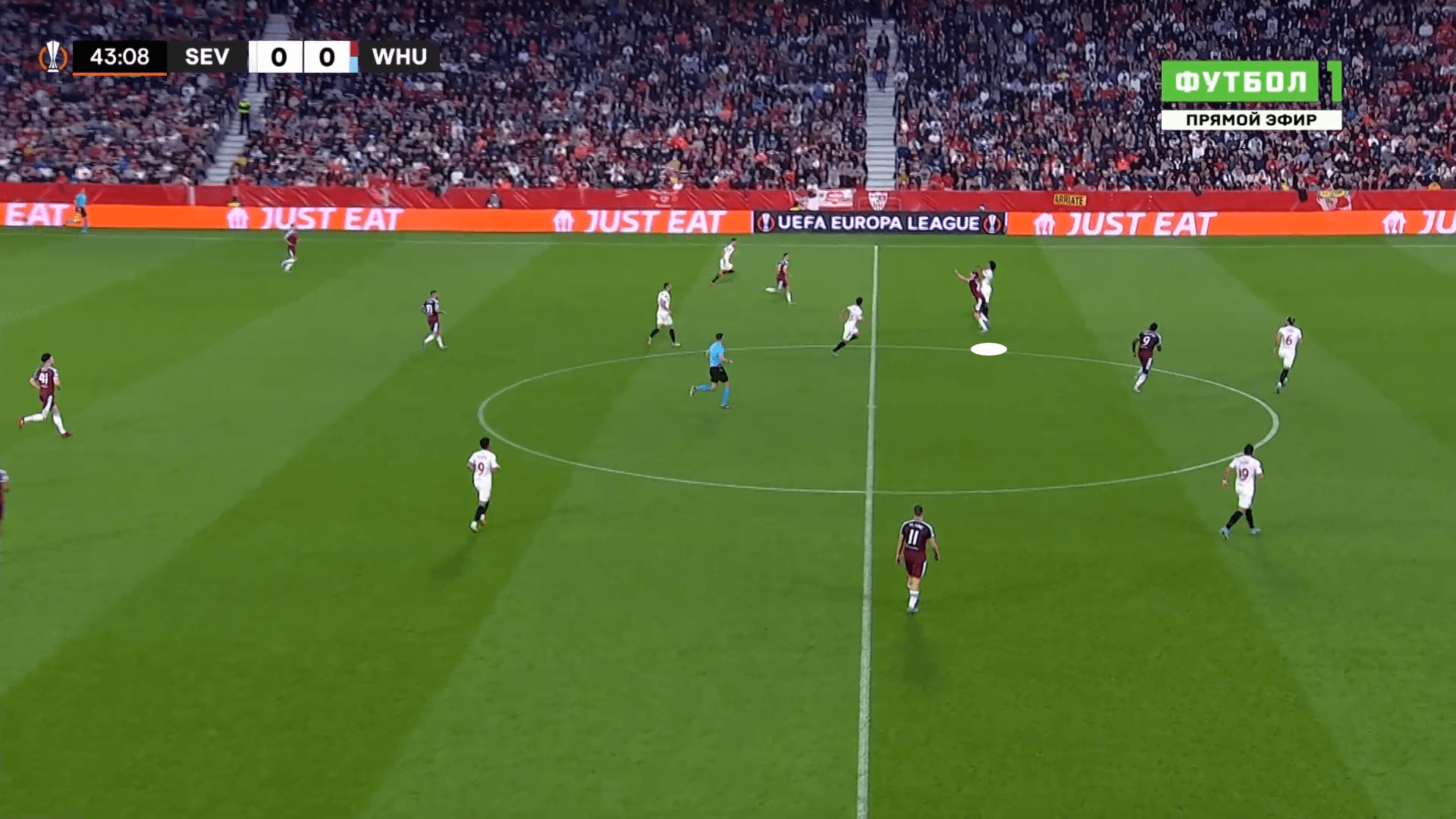

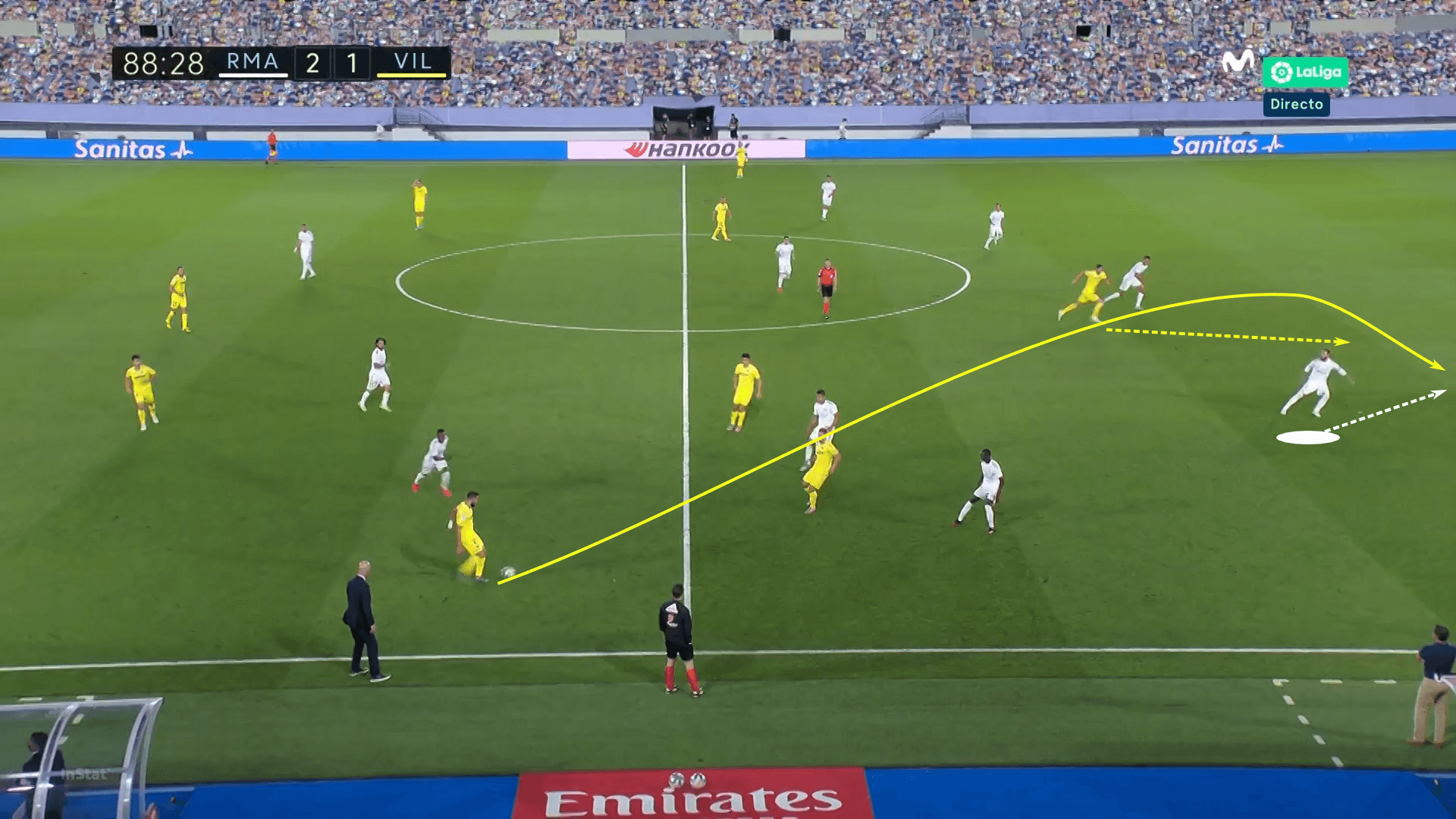

As an undersized centre-back in a high-pressing team, anticipating passes played over or through the backline are critical to the team’s success. That’s what we find in this Sergio Ramos example against Villarreal. As the Yellow Submarines look to play over the top, Ramos was two steps ahead of them. Looking over his right shoulder, he saw the run of the targeted attacker. Seeing the run and having several yards on him, Ramos was already backtracking by the time the first attacker put his head down to deliver the ball over the top.

Ramos claimed an uncontested header, regaining the ball for his side. Don’t let the ease of the final action take away from the brilliance of Ramos’ awareness and anticipation. Since the first attacker had time to pick up his head and identify runners higher up the pitch, Ramos naturally assumed that the run was coming. Without his shoulder check and early retreat, his opponent gets on the end of this pass.

While that example covers a ball played behind the backline, this next one returns to an idea mentioned in the vulnerability section, aggressive movements into midfield. You’ll recall the vulnerabilities attached to this movement are overconfidence and failing to adapt to faster opponents.

The strength of the action is that, when timed well and executed, it ends a threat before it fully develops.

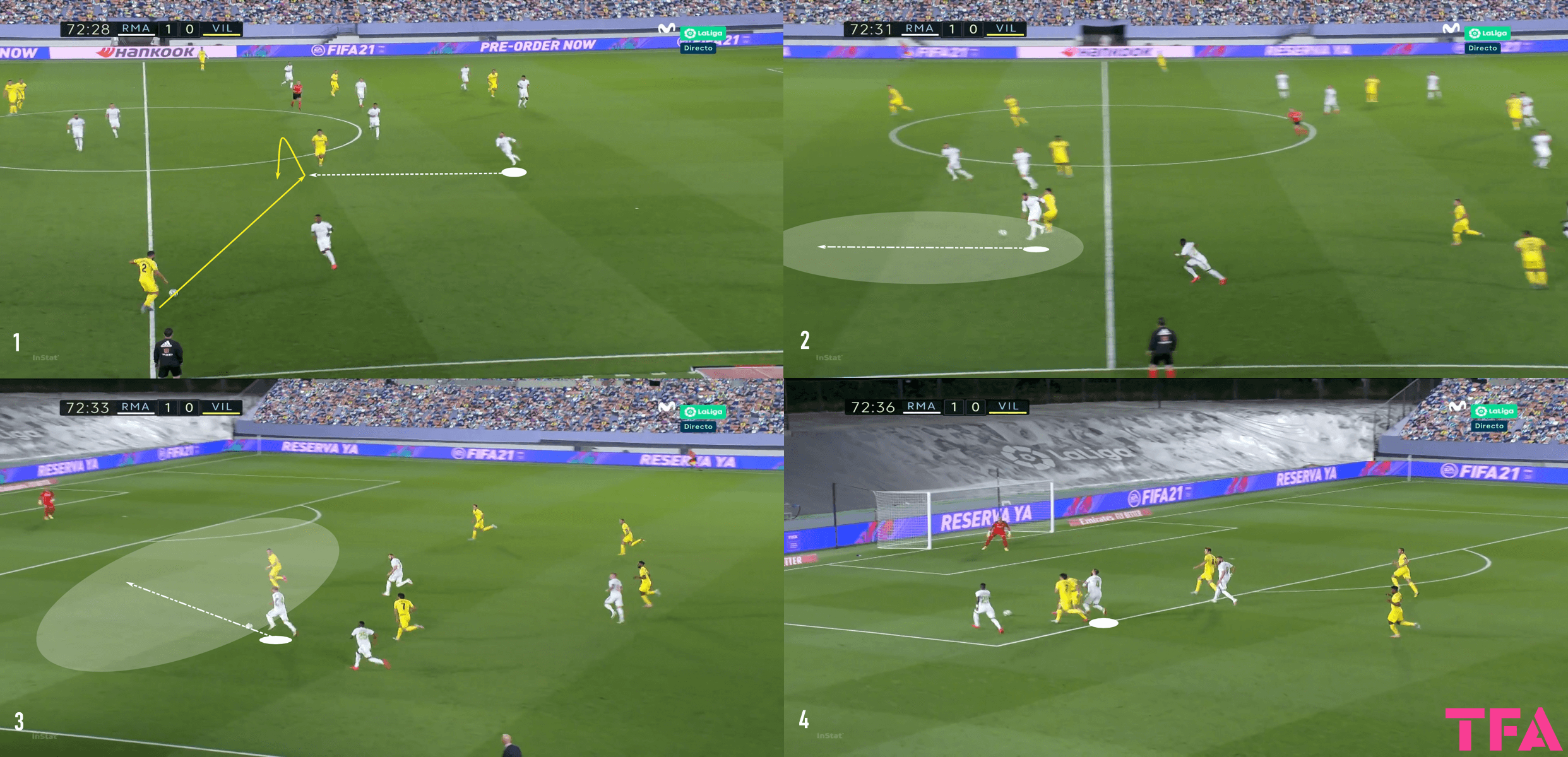

Take this Ramos sequence in the four-in-one image as an example. In the first frame, he identifies that the pass is coming central. Notice the timing of his movement. The pass isn’t even in motion, yet Ramos has already identified that that’s where the ball is going and is in route to his first defender role. That arched line in the first frame shows that the first touch was popped up, largely due to the pressure Ramos put on the first attacker.

In frame two, Ramos outmuscles his opponent and gains possession of the ball, then dribbles up the pitch to lead the counterattack in image three. The sequence ends with Ramos getting fouled on the top of the 18 to earn a penalty kick for his side. That turned out to be the game and title-clinching goal of Real Madrid’s 2019/20 La Liga campaign.

As a former right-back, Ramos’ instincts took over as he streaked up the pitch. The underlying physical qualities we see are his acceleration that compliments his read of play and the explosive speed to cover the ground and create the 1v1 higher up the pitch.

For undersized centre-backs, exceptional mobility is often as important as reading and responding to the flow of play. As those physical attributes decrease, the tactical acumen must increase.

Even as the physical skills gradually diminish, mobility is still key for undersized centre-backs, especially if they’re playing in a back four in a possession-dominant side. With the outside-backs pushing high up the pitch, the expectation is that the two centre-backs can manage both the space between themselves and the goalkeeper and the width of the pitch. An early read of those plays certainly helps, but the mobility to arrive first is still important.

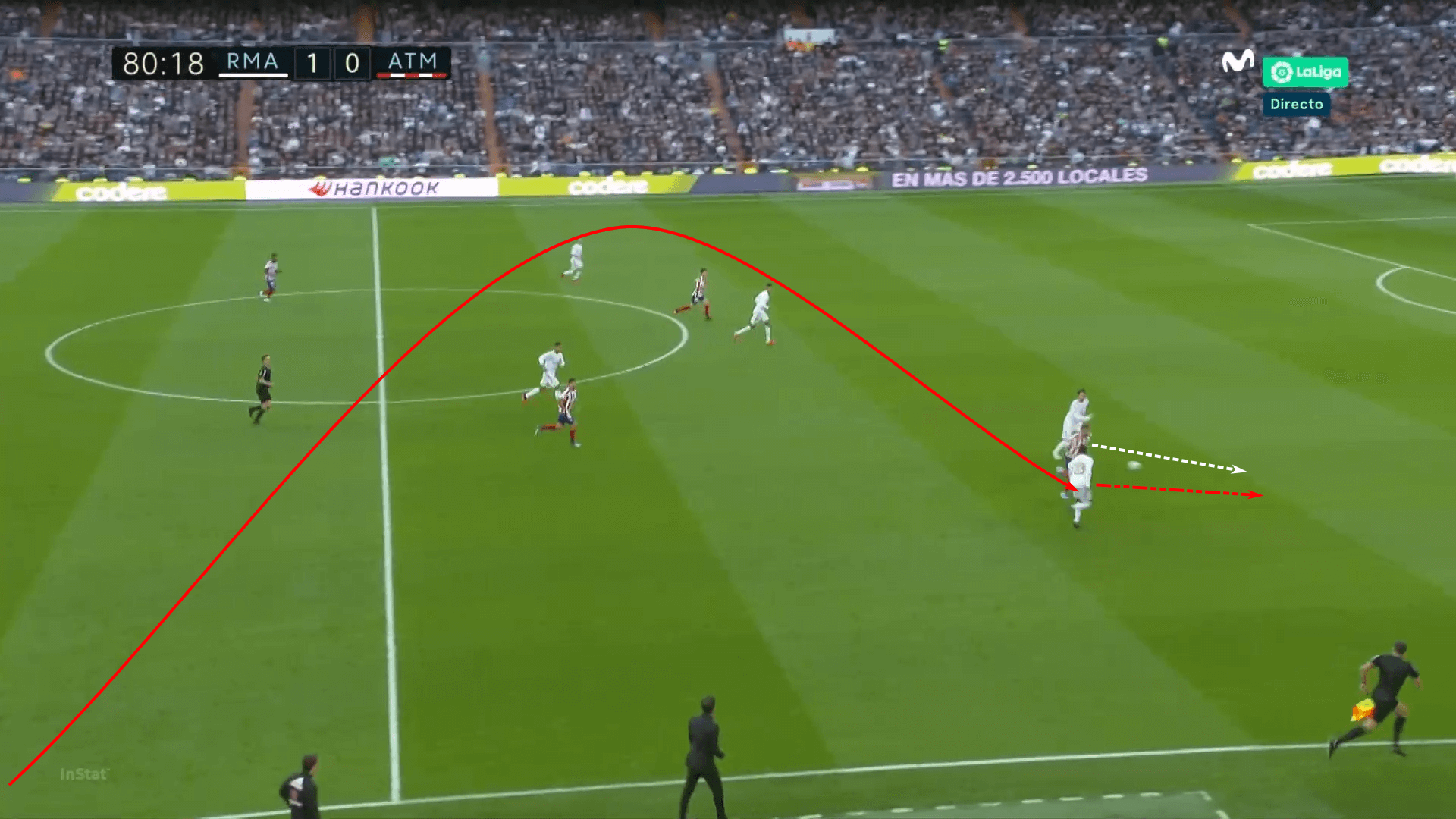

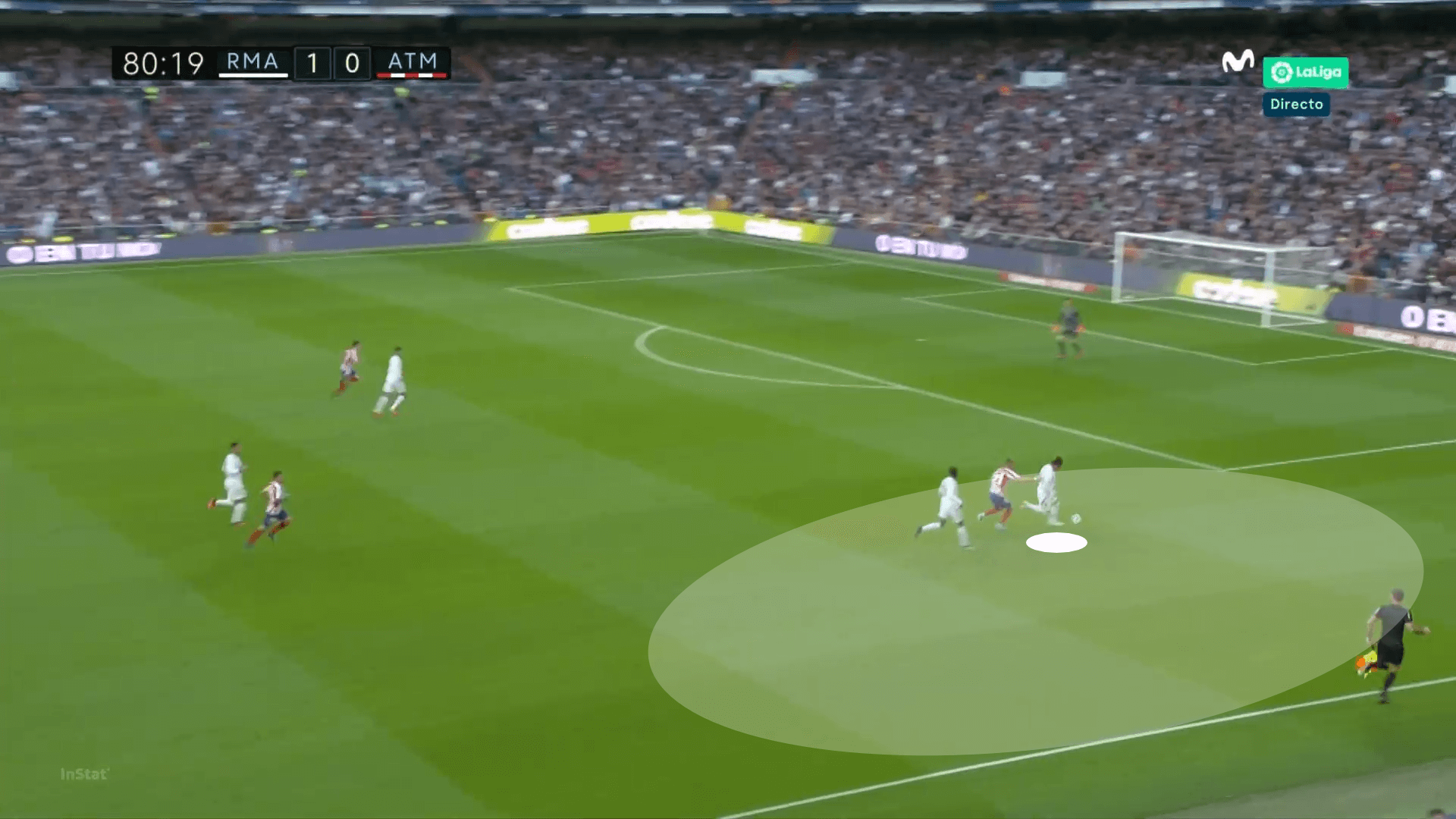

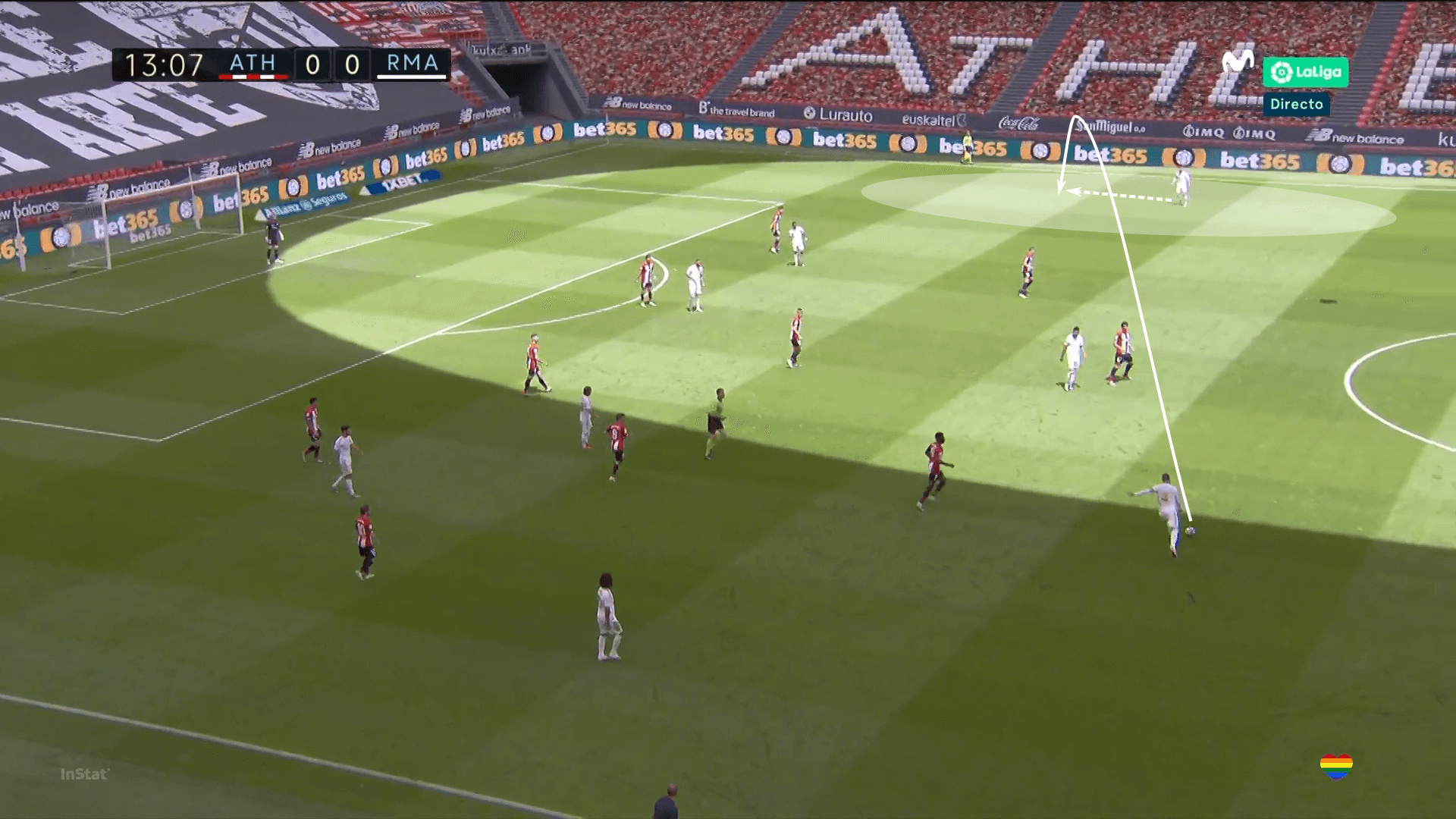

Let’s include one more Ramos example in this section. Again during his Real Madrid days, El Derbi Madrileño saw Atlético attempt to play behind Ferland Mendy on the Real Madrid left wing. The outside-back was beaten, cueing Ramos to transition into a first defender role. Fortunately, the opponent’s first touch was poor and knocked the ball too far in front of him. That touch turned this into a fight of physicality and pace.

Ramos does get to the ball first, winning possession and turning the corner, but throughout the chase, you could see the clever use of the hands and arms to establish position and move into the ideal running lane. By the ideal running lane, I mean he had cut off his opponent and secured a good angle of approach to the ball. Had he not been able to turn the corner and get free of his mark, Ramos almost certainly would have drawn a foul, getting himself and the team out of trouble.

His mental and physical quickness were key to establishing position. They certainly help defenders secure interceptions, but they’re also a key component in the tackle as well.

Ramos’ replacement at the Spanish capital, Alaba, offers a great example of how short centre-backs can use their specific physical qualities to their advantage. In the away leg against Barcelona, Alaba got on his opponent’s back, standing between him and the goal. However, as the attacker’s balance started to waver due to Alaba’s constant contact, the Austrian quickly shifted around his opponent to win possession of the ball.

The quickness and agility to get around his opponent, continuously moving his feet from one balanced position to another, is critical to Alaba’s success. That said, we can’t ignore the contact he makes throughout the duel. By constantly pushing his opponent off balance, Alaba was creating opportunities to use his quickness and agility to recover the ball.

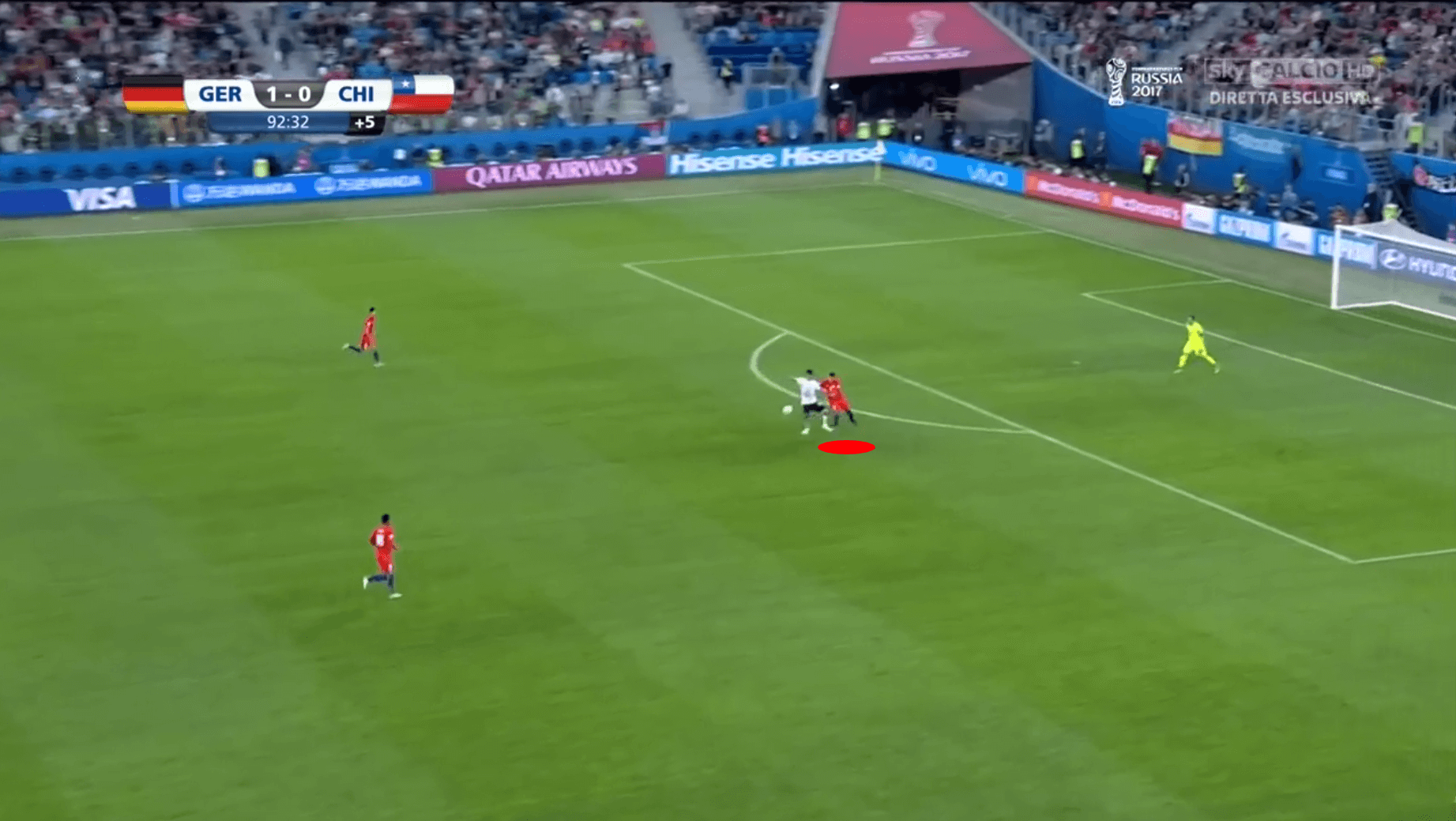

When you think of top, short centre-backs who were exceptional in their contact with opponents, you cannot beat the Chilean dynamo, Gary Medel.

Late in this Confederations Cup match against Germany, Medel was isolated with his opponent but managed to win the duel with some physical defending. Some of the key takeaways here are Medel’s low centre of gravity relative to his opponent’s. Zoom in on the image and you might even see a little arm hook. There’s lots of contact on the play, all designed to throw his opponent off-balance before attempting to win the ball.

Note the use of Medel’s arms. He does really well to ensure he doesn’t get turned on this play. As the last man back, it’s up to him to at least delay the opposition’s advances. Ultimately, through a combination of well-placed physicality, agility and quickness, Medel comes away with the win.

Passing ability

Finally, let’s briefly discuss passing ability.

Coming into this tactical theory piece, I assumed a quick data analysis would show that undersized centre-backs were superior with a ball at their feet. In fact, I assumed they would be far better than their larger peers. Perhaps this is simply an assumption, but dexterity seems to come easier to smaller players than larger ones. My assumption was that this would transfer to improved passing accuracy and, therefore, higher degrees of trust from the team to direct the attack, leading to more passes P90.

After all, as someone who watched Sergio Ramos at Real Madrid for over a decade, it just seemed natural that the Ramos’ of the football world would be more influential in possession than the Pepes and Varanes. It was incredibly challenging to find a single picture of Ramos’ distributions where both he and the target were in the same frame. With his passing range, it turned out to be a difficult task. It took time, but we do have one of his signature switches of play to Dani Carvajal high in the right-wing.

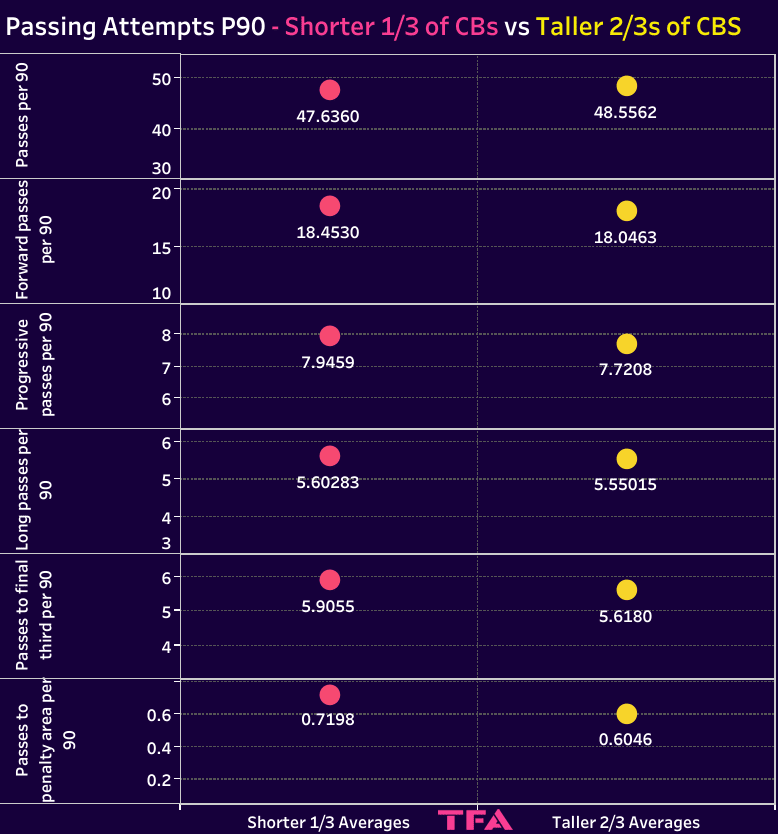

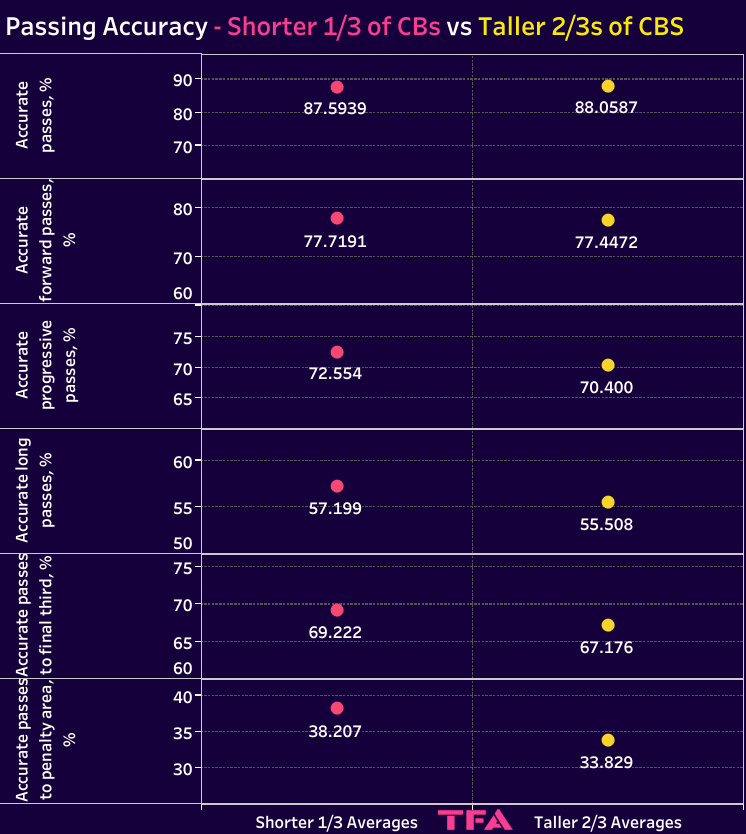

Again, the assumption was that the smaller centre-backs would be better on the ball and more influential in possession. It turns out that the two player pools are virtually even in terms of passing metrics. In the next two data visualizations, the player pool is centre-backs from the UEFA top five leagues from the 2020/21 campaign with a minimum of 500 minutes played.

To get a better sense of what constituted a short centre-back, the data made a nice split at 185 cm. Anyone at that height or shorter fell into the approximate bottom third of centre-back height. 186 cm and above represented approximately 2/3 of the eligible players.

As you work through the data, you’ll find that the shorter centre-backs typically have a slight advantage. For example, in the passing attempts P90 data visualization, which represents six distinct passing types, the only advantage for the taller 2/3 of centre-backs is in passes P90. Otherwise, shorter centre-backs maintain a slight advantage.

But what about accuracy? Does the assumption of superior dexterity carry any weight?

While the shorter centre-backs generally produce better passing accuracy numbers across those six metrics, it’s not enough of a difference to say definitively that the undersized player pool are either better with the ball at their feet or play a more prominent role in their teams in possession tactics.

So, while there are several highly influential undersized centre-backs with exceptional technical qualities, there’s not enough of a distinction to say that they are positioned centrally because of their distribution qualities. Rather, it’s more likely that their mobility and anticipatory skills while defending higher up the pitch are more critical than their influence in the team’s attacking tactics.

Conclusion

The legacy of short centre-backs who make a big influence is a long and storied one. The Moores, Beckenbauers, Baresis, Cannavaros and Pujols are still among us and still highly influential in the modern game. The legacy lives on through players like Ramos, Silva, Koundé and possibly Martinez.

As with any position, adaptation will be key for these players as they move to different leagues and take on different roles. Martinez has admittedly had a difficult start to life at Manchester United, but the success of his transfer is far from final after two matches. It’s up to him to show he can adapt and employ lessons from other great undersized centre-backs, both past and present.

The list of short centre-backs is impressive. In fact, you could even say it’s representative of the ‘best of’ at the position. While the game has evolved and the position has too, there are still so many lessons for today’s undersized centre-backs to take from their predecessors and colleagues.

The lessons are there. The key is to learn and apply. It’s a time to stop dreaming about physical growth and to key in on tactical intelligence.

Comments