The game’s best pressing teams have an orchestral quality to them.

Each movement is heavily synchronized and rhythmic. These sides often alternate between low-tempo structural movements and high-intensity chasing. These teams collectively identify the best moments to engage the opposition and showcase hypnotic teamwork to execute the defensive phase.

There’s so much to learn from these sides and this tactical analysis aims to identify the top principles of defensive engagement from the best. Running data on UEFA’s top 5 leagues, we have identified 17 distinct clubs to serve as examples of high press and middle block execution. We’ll start with the high press, examining the sides that lean heavy metal. After we’ve examined their principles of play, we’ll look at a passive high press, noting the adaptable tactics of coaches using this approach. Finally, we’ll look at the mid-block, breaking it down into principles of engagement and identifying pressing triggers.

Immediate pressure in the high press

An aggressive defensive structure requires an aggressive pressing mentality. Sorting through the high press clubs, the first distinction we’ll make is between those who prioritize immediate pressure on the first attacker versus those that take a more methodical approach, using spatial and personnel parameters to determine when to engage opponents. Let’s start with that first high-pressing group.

Most of the teams in this first section won’t surprise you at all. They’re possession dominant and among the top sides in Europe. They hold qualitative advantages over the vast majority of their opponents and are impeccably coached. These teams use their forward line to aggressively pursue the ball while the midfielders and defenders prioritize structure over pressure. In most cases, their job is to intercept intermediate-range passes into midfield or long-range passes into the opposition’s forward line. Their job is more nuanced, requiring them to protect the centre of the pitch while being prepared to contest outlet passes both centrally and in the wings as opponents attempt long diagonals.

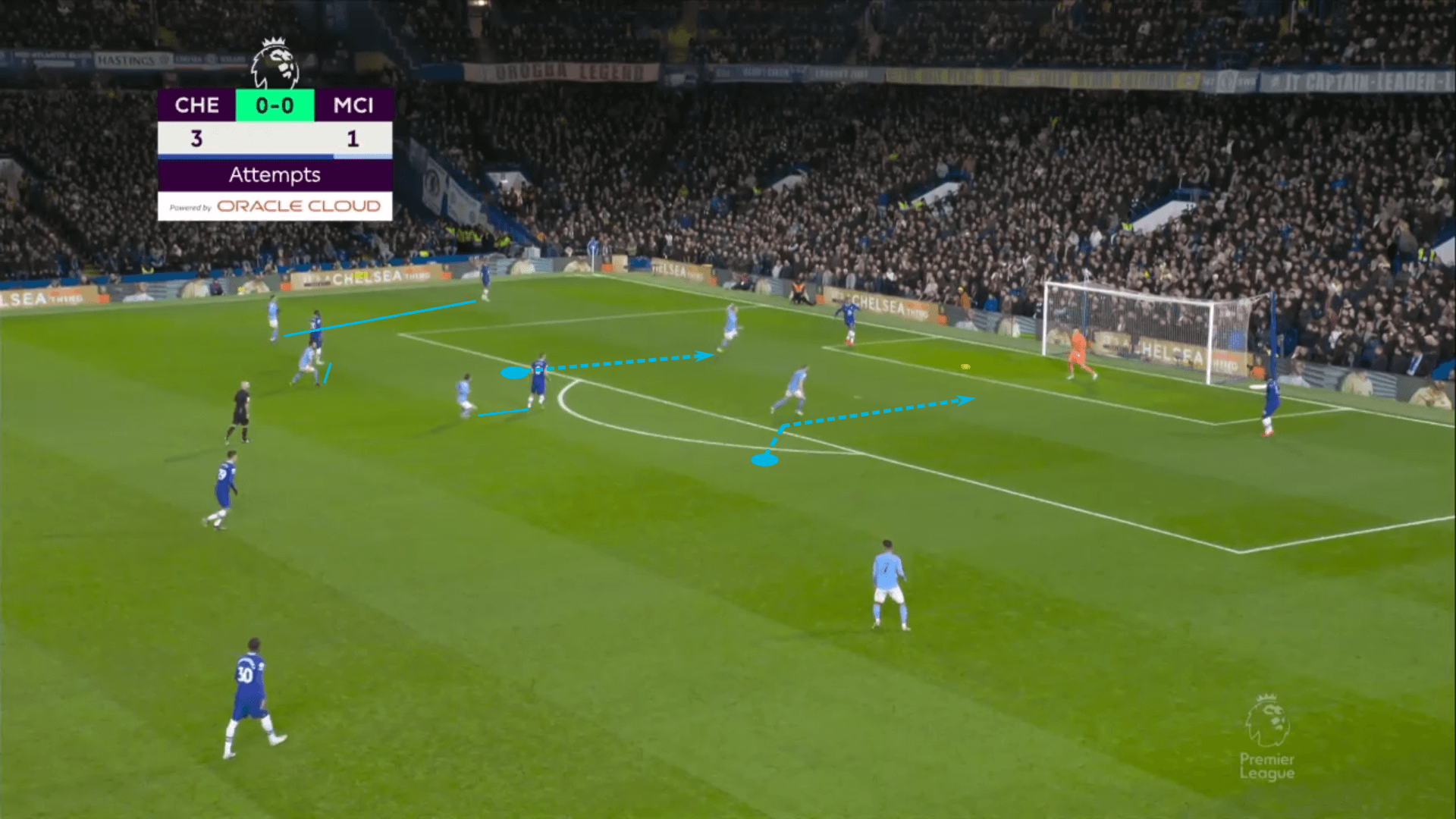

While counterpressing is the most important defensive quality for many of these elite sides, that general aggressive approach to the game is seen in their high-pressing tactics. Take Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City. When opponents take short goal kicks, two players are stationed at the ends of the penalty arc and are prepared to sprint into the box as the ball reenters play. They commit high to place immediate pressure on the goalkeeper and centre-backs. Meanwhile, the next line of the press is right behind, often just outside of the box to eliminate short and intermediate options. The top objective is to win the ball high up the pitch, the second is to force the opposition to play long. City typically enjoy a qualitative advantage at the back and are well-drilled at the back, typically winning first and second balls.

City’s positional superiority allows them to maximize their qualitative advantage. For Guardiola, the most common question in the high press is whether City will win the ball in the final or middle third.

From open play, the foundational concept is the same; the out-of-possession team’s nearest defender must apply pressure on the ball as quickly as possible. As the first attacker applies pressure, supporting defenders cut out short and intermediate options while the third defenders prioritize structure.

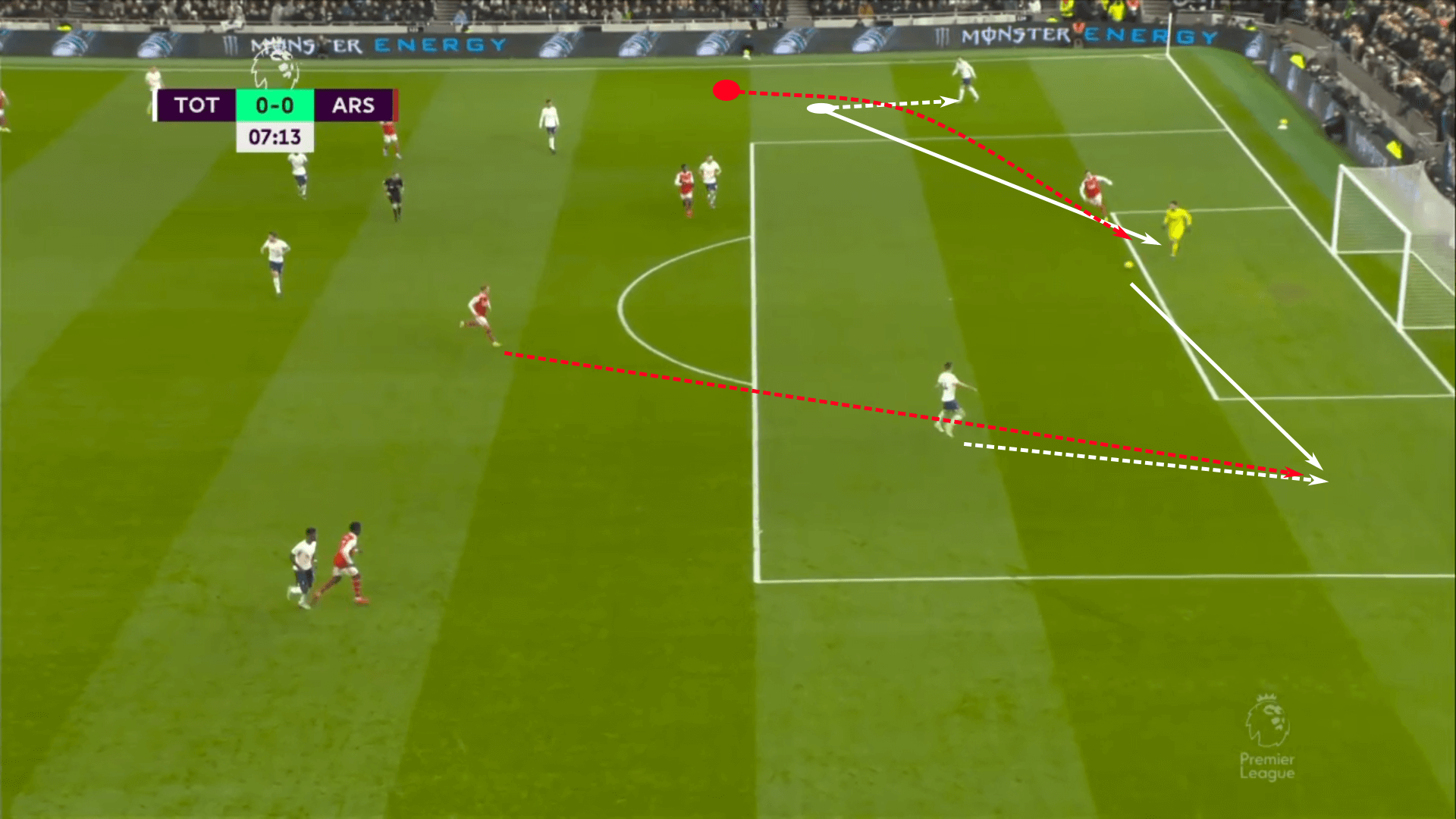

The North London Derby offered a perfect example. After a misplaced pass, Arsenal transitioned to defence while Tottenham opted to play all the way to Hugo Lloris, resetting the attack. That didn’t stop Arsenal from sending the first defender to pressure the goalkeeper. In fact, Lloris was so slow with his decision-making that he played the pass behind his left centre-back, Clément Lenglet. The moment Martin Ødegaard knew the past was going to Lenglet, as opposed to Pierre-Emile Højbjerg in the central channel, he quickly transitioned into the first defender role. The poor pass benefited the Norwegian, allowing him to block Lenglet’s attempted clearance, leading to an early chance for the Gunners.

With both the City and Arsenal examples, as well as the next one featuring Bayern Munich, we find a commitment to push numbers high into the press. If the ball is central, the team’s making an effort to apply immediate pressure on the ball while shortening intermediate options and asserting control over the centre of the pitch. The only way out is to play to the first line or hope for a successful long diagonal to the wings.

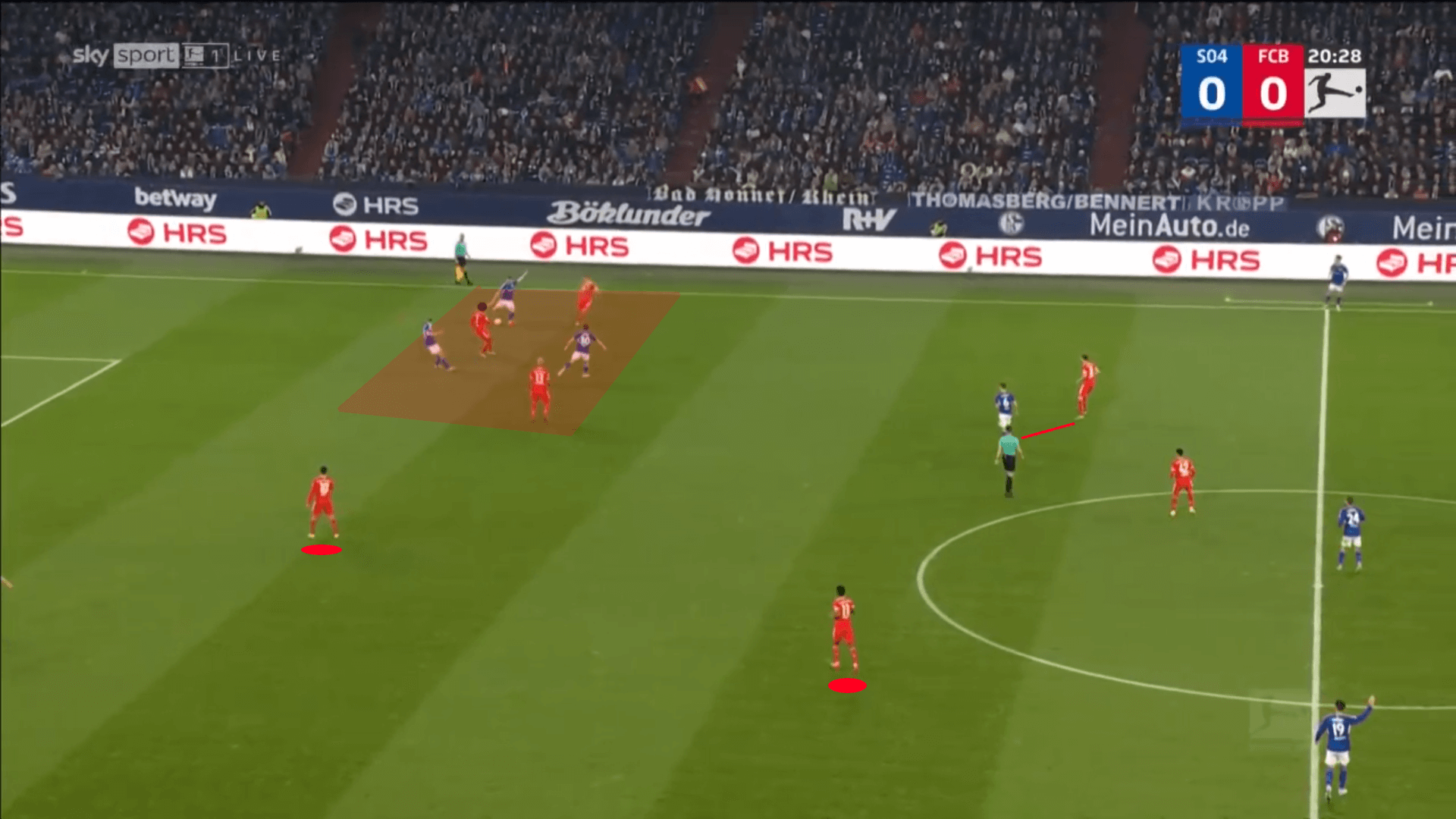

A hallmark of high-press teams that apply immediate pressure on the opposition is that they are exceptional at getting numbers near the ball. In this Bayern Munich example against Schalke, play is funnelled to the left wing and the Bavarians are quick to make it a 3v3 near the ball. The only intermediate option is tightly marked and the German champions have two players centrally with room to run toward goal should Bayern recover it. Sensing the threat, Schalke panicked and played long.

While the high recovery is preferable, there’s a certain predictability to the opposition launching hopeful balls into their forward line. With Bayern’s midfield dutifully cutting out intermediate options, the one path forward is high and long.

Teams that routinely play the long ball do so with the assumption that, by playing the odds, they’re likely to generate at least a couple of scoring opportunities a game. Chaos is the objective. For the defending team, managing the chaos with a strong structure at the back, dominant aerial presences, and good anticipation is key. Fortunately, the WHERE and the WHEN of the attacking action are easily anticipated. All that’s left is the execution, which is typically spot-on from the top players in the game.

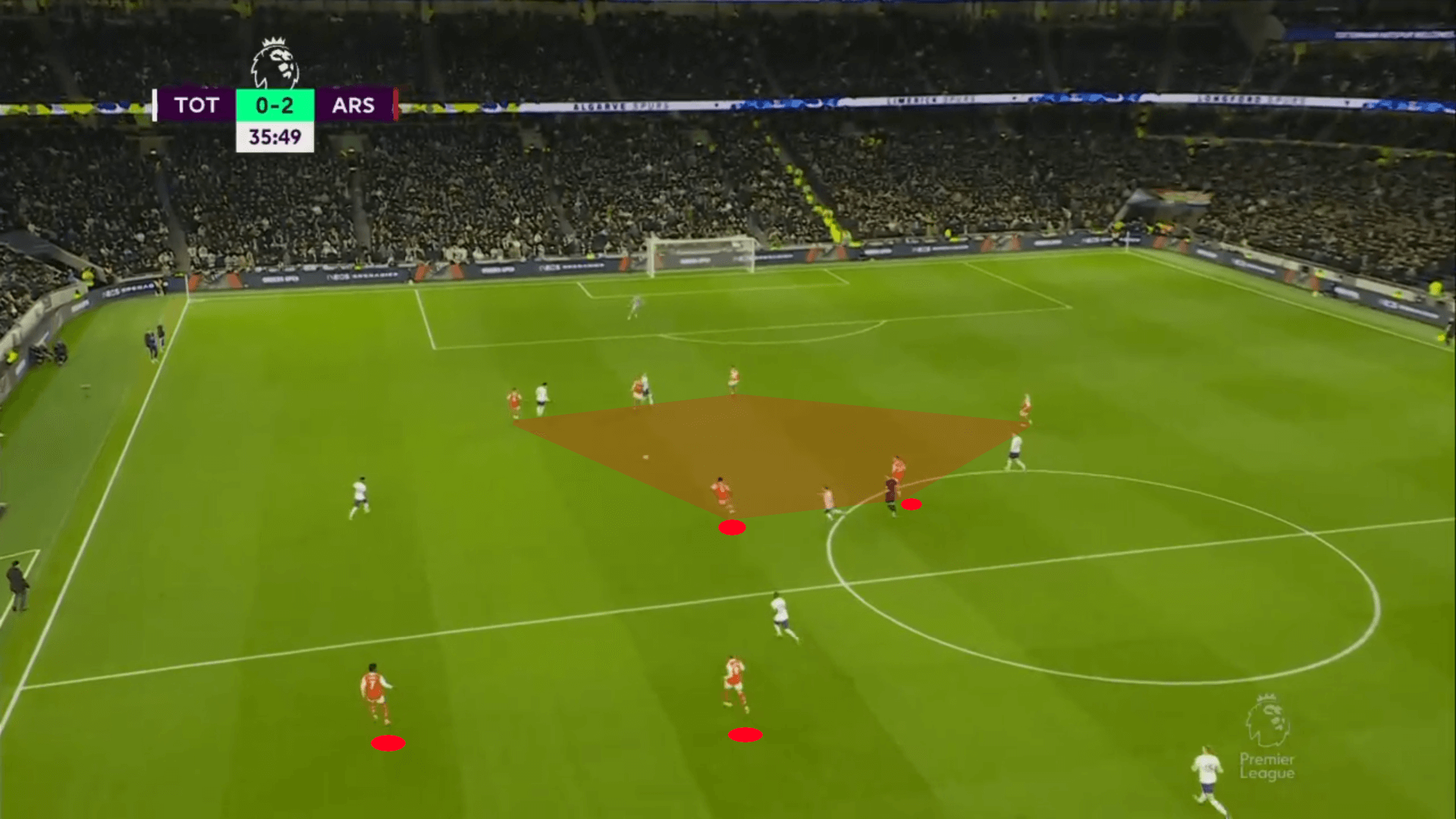

Take Arsenal for example. In that Tottenham match, Ødegaard ‘s goal, the second of the game, started with Arsenal winning the first and second balls after Tottenham attempted to play long. Arsenal has a 4-2 structure at the back with the two central midfielders tightly connected to the centre-backs. Once the first ball was won, the second was easily claimed and the counterattack started.

Looking at Arsenal’s shape, they have a strong central presence, outnumbering Tottenham both at the back and at midfield. Right away, they are favoured to win both the first and the second balls. Even for world-class talents like Harry Kane and Son Heung-min, positional superiority is difficult to beat.

Effective high-pressing teams find the balance between all-out pressing and positional discipline. The players up front typically have a simple job: put pressure on the ball. Meanwhile, the players behind them must find the balance between maintaining their central presence, eliminating easy outlets, and being prepared to track wide and seal the opposition.

To make everyone’s jobs easier, high-pressure teams can further tilt the advantage in their favour by forcing the ball into weak links along the backline or, commonly, funnelling play back to the goalkeeper. With the ball at his feet and limited to no options to move the ball locally, the one option is typically to smash it long. His delivery is further complicated if he’s wrong-footed or the pressure from the opposition impacts the timing or angle of his approach to the ball.

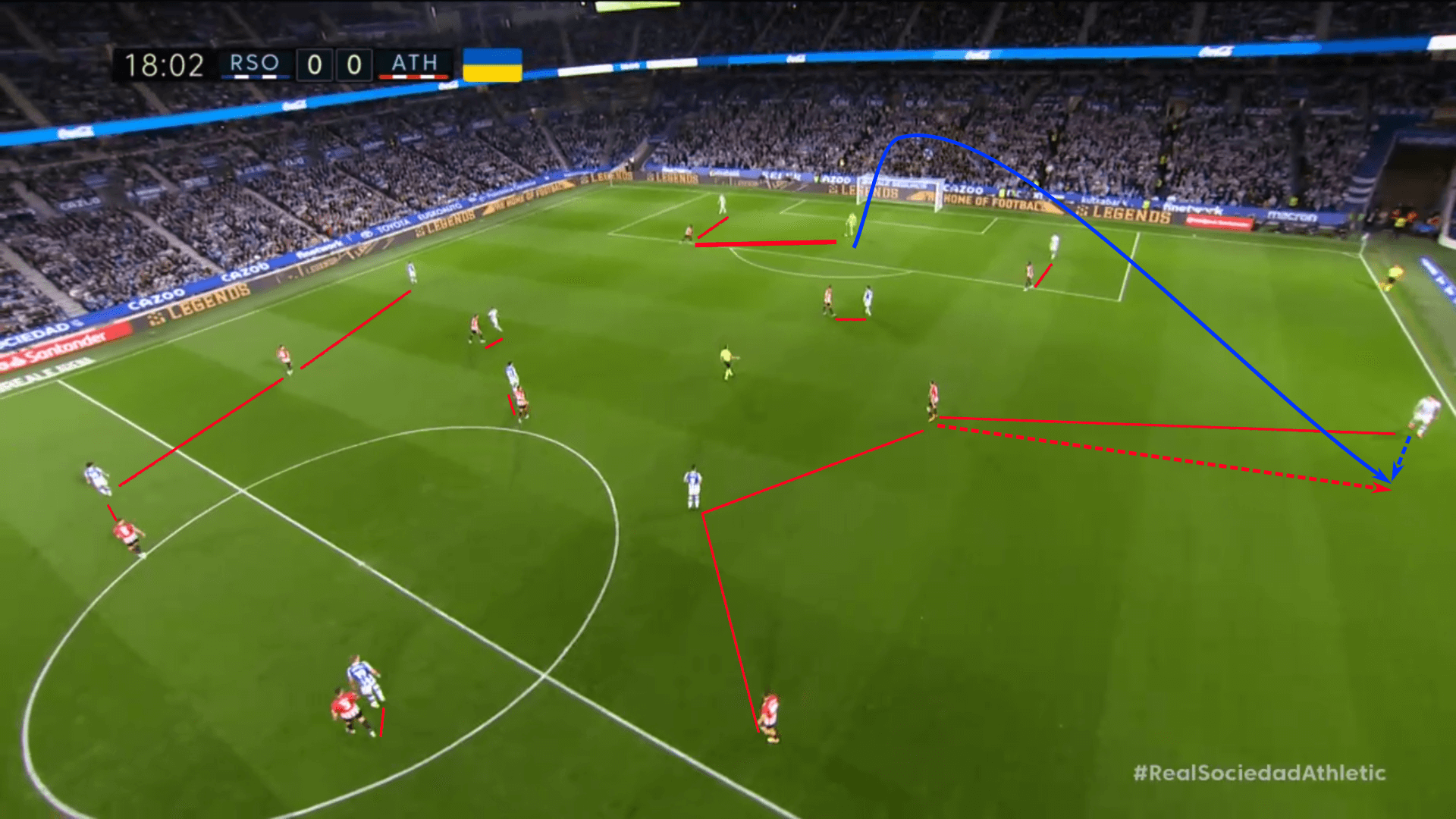

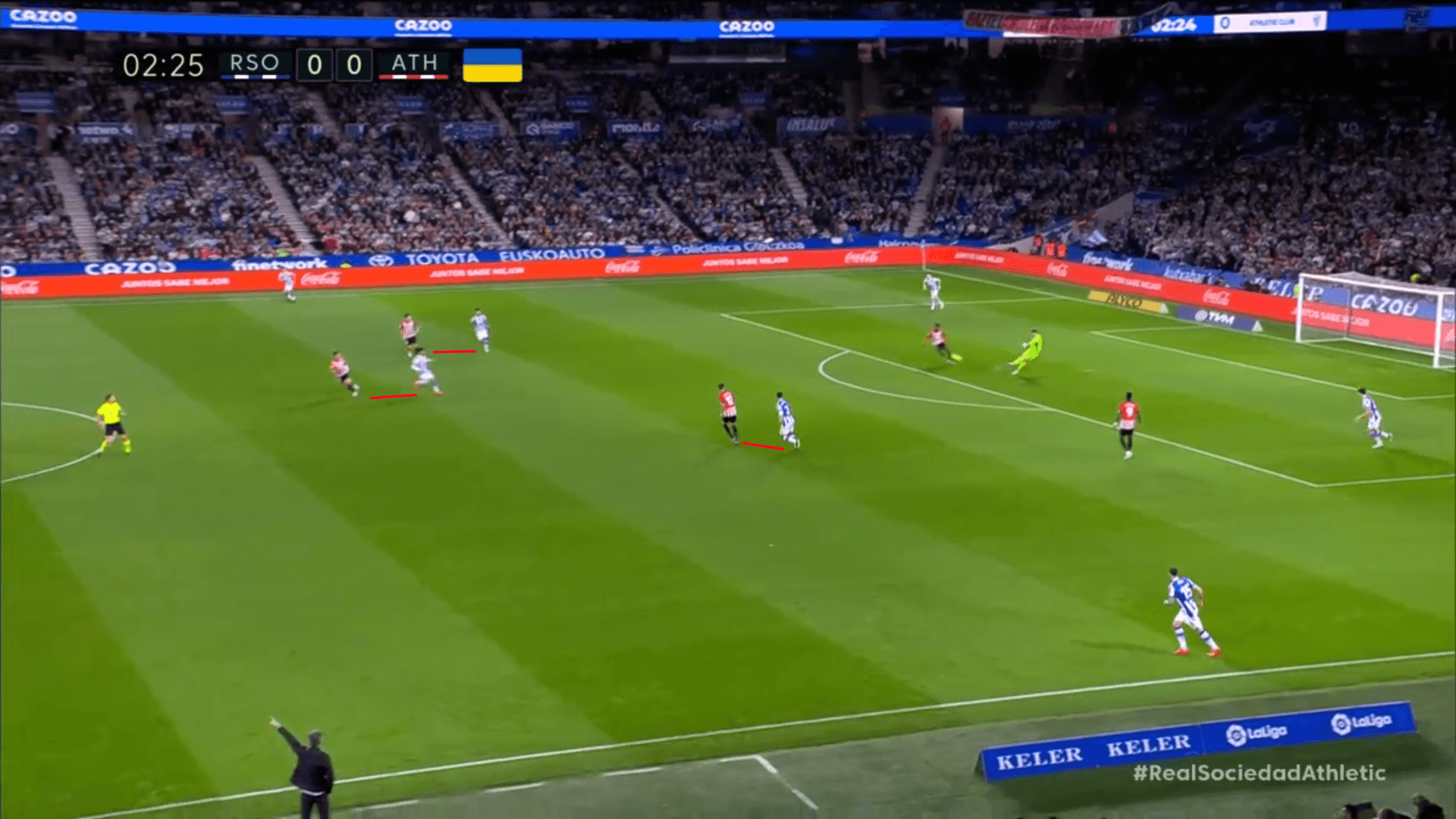

We have an example of this from Athletic Club. Iñaki Williams applied heavy pressure on the Real Sociedad goalkeeper, forcing him into a rushed delivery. Notice all the midfield options are accounted for. You would argue there’s one player near midfield who’s still an option, but there are three defenders within approximately 10 meters of him. Any pass into him will be contested. In the end, the long diagonal was played and even that is contested. A sequence of 50/50 balls leads to a change of possession, signalling a successful defensive sequence from Athletic Club.

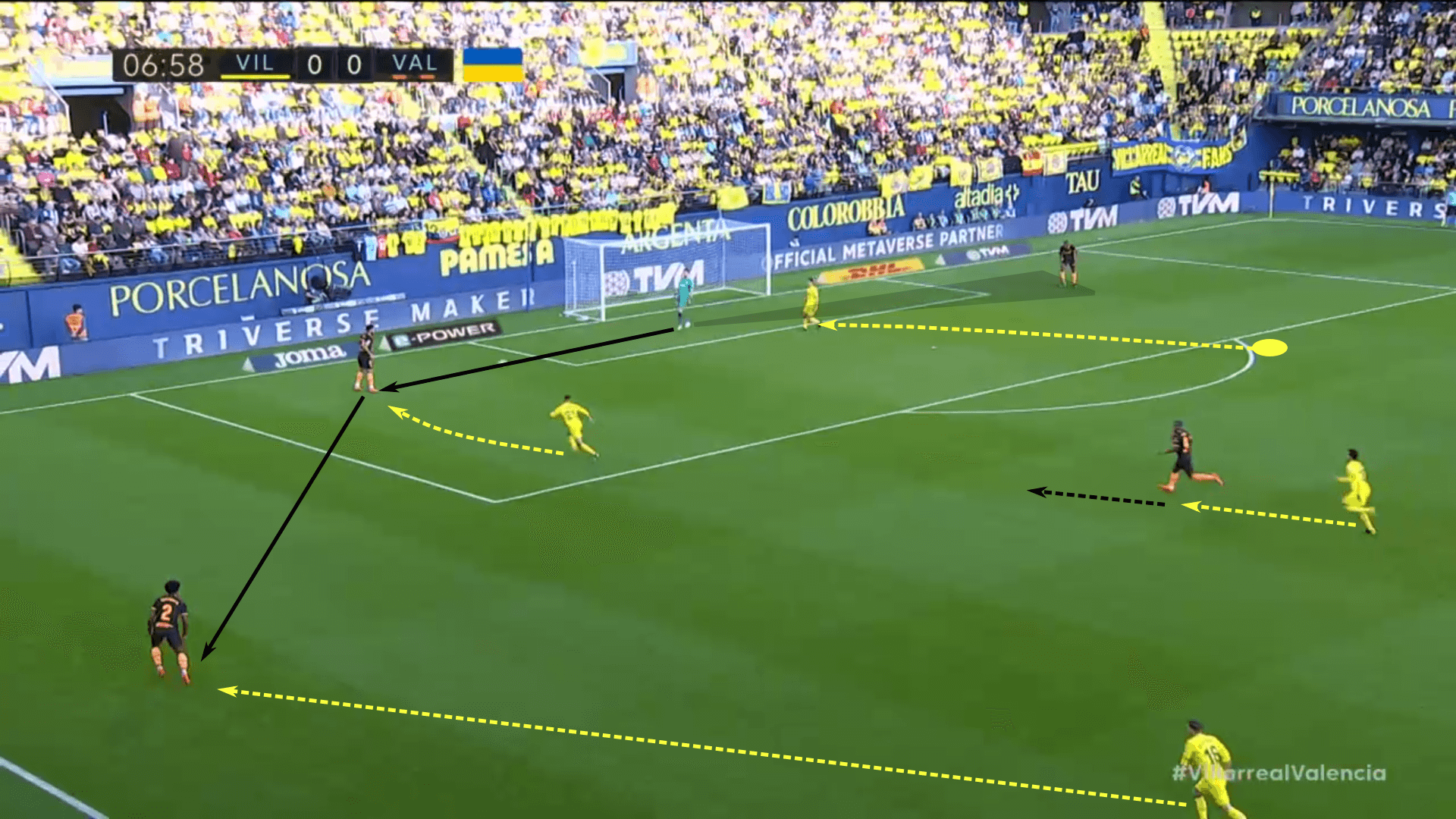

As high-pressure teams step forward, they’ll use the opposition’s actions against them. Take this example from Villarreal. The moment Valencia put the ball in play, Villarreal’s forwards rushed into the box. The ball was returned to the goalkeeper but his body orientation indicated his next pass was to his right. You can see Gerard Moreno slightly bending his run to eliminate the left side of the pitch. The curved run is very slight but the top priority is making ground up the pitch. As the pass was made to the right Yéremy Pino attempted to bend his run to eliminate the wide outlet, which was unsuccessful.

Two additional notes in the sequence are the heavy man-marking of Yunus Musah, Valencia’s checking midfielder, and Villarreal’s preparedness to step forward in the wing once the pass found its way to Kiko, the right-back. Alberto Moreno, Villarreal’s left-back, did well to anticipate the next pass into Kiko and move forward to apply immediate pressure. Though he did not intercept the pass to Kiko, what he did do was force a difficult pass forward, resulting in an interception for the home side.

Some of the key concepts in play were immediate pressure on the first attackers, central positional dominance to eliminate play through the middle and the next man quickly stepping into a first defender role as a wide outlet was played. The sequence is very aggressive, but it’s that aggressiveness high up the pitch that forced a poor pass leading to the interception. The idea is to gamble with numbers high to make play predictable for the deepest members of the team. Plus, with Valencia in their expansive attacking shape, Villarreal has an immediate positional advantage with their narrow defensive structure. Forcing Valencia to play into a numbers-down scenario is a tactical win for the Yellow Submarines.

One final distinction to make in this section is that high-pressure teams would like to win the ball in the final third, but that’s not their sole objective. If anything, the goal is to deny progression. Ideally, the defending team will force the opposition to play a rushed pass into a limited window where the out-of-possession team has a positional advantage. Winning the ball high up the pitch is ideal, but denying progression is a higher priority.

Forcing a sequence of negative passes is one of the best ways to force the opposition’s hand into playing a hopeful ball forward. If forward passes are unavailable, many teams will play a negative pass in search of a new angle forward. Continued first-defender pressure in unison with tight marking of short and intermediate targets will often generate a sequence of negative passes. The issue here is that there is a definitive endpoint, which is a pass to the goalkeeper. Once he has the ball, there’s nowhere to go but forward.

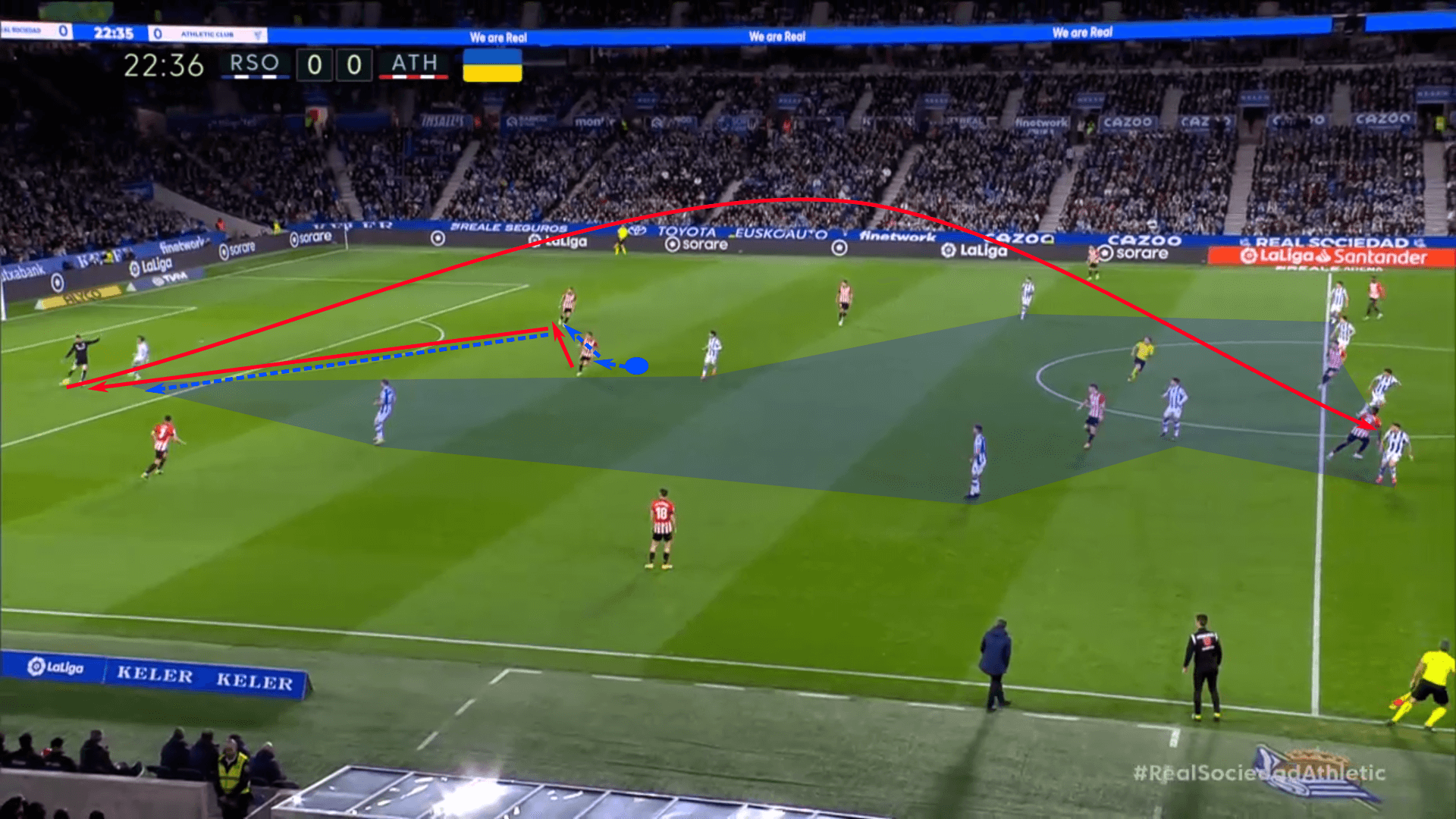

Looking at Real Sociedad’s high pressure against Athletic Club, we have an example of Takefusa Kubo chasing the ball as the first defender. The third player he pressures is the goalkeeper. As the ball arrives at the goalkeeper’s feet, he’s on his preferred right foot. From Kubo’s perspective, he must know that his odds of getting to the ball are slim, but what he can do is limit the goalkeeper’s angle forward. Not only is Athletic Club looking for the forward pass from a deep position, but now the angle of possible forward passes is extraordinarily slim as well.

As the goalkeeper plays the past forward, look at Real Sociedad’s defensive shape relative to Athletic Club’s attacking structure. While Athletic Club has several players in wide areas and minimal midfield presence, Real Sociedad is well-positioned to compete for the first ball and collect the second. That’s exactly what happens. They win the first and the second.

Among the core principles of high pressing are first defender pressure on the ball, elimination of short and intermediate targets and central positional dominance. From a meta-perspective, denying progression is the top objective. Forcing the opposition to play forward passes from deep positions, poor angles and rushed timing are some of the tactical approaches that increase their chances of success. With the out-of-possession team in their compact defensive shape, they own a positional advantage that the opponent will likely play into. Even if the opponent attempts to play long diagonals into the wings, the time of flight often makes these contested passes.

Aggression is key, forcing the opposition to make rushed decisions from their defensive third. The recovery may not come in the final third, but the defending team will at the very least expect to compete for a middle-third recovery.

Delayed pressure in the high press

We’re going to stick with the high press, but move away from immediate first-defender pressure. Instead of that pressure being a hard and fast rule, we’re going to look at teams that take a more nuanced approach to the high press. Pressure is delayed as teams look to engage the opponent within certain tactical parameters.

One of the nice things about this approach is that it’s highly adaptable, as we’ll see in the examples below. Each team may have a preferred approach to a passive high press, but as this analysis will show, it’s also adaptable to specific opponents. One of its strengths is the ability to adapt the press to account for the opposition’s strengths and exploit their weaknesses.

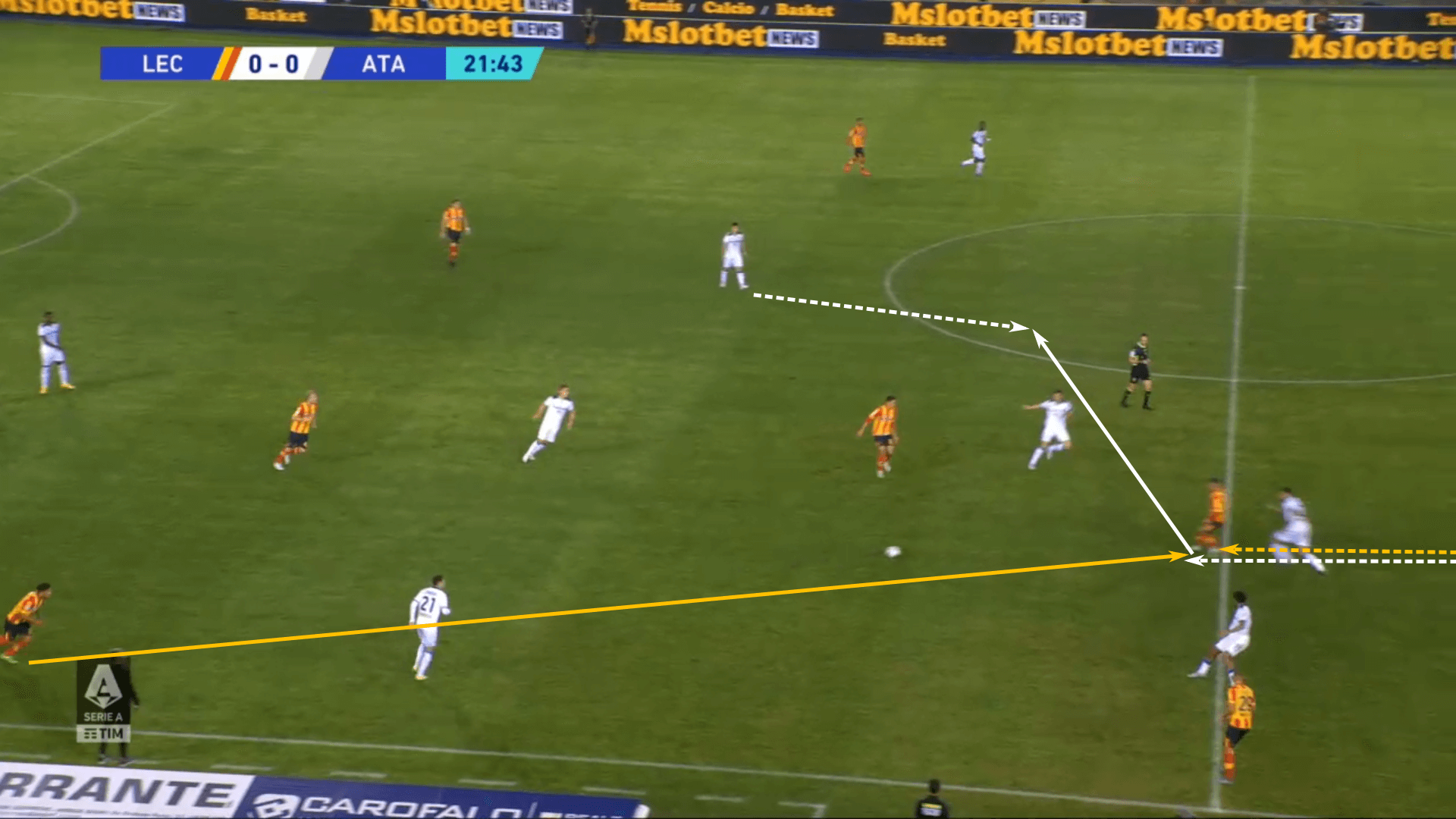

Let’s start with Lecce. The newly promoted Serie A side is one of the most complicated opponents in Italy. While they have struggled to score goals this season, their defensive discipline has them closer to the middle of the table than the relegation zone. Unlike most newly promoted sides, Lecce will push high up the pitch in search of high recoveries. Their setup against Atalanta led to two quick goals against Gasperini’s side, leading to an improbable victory against one of Italy’s top clubs.

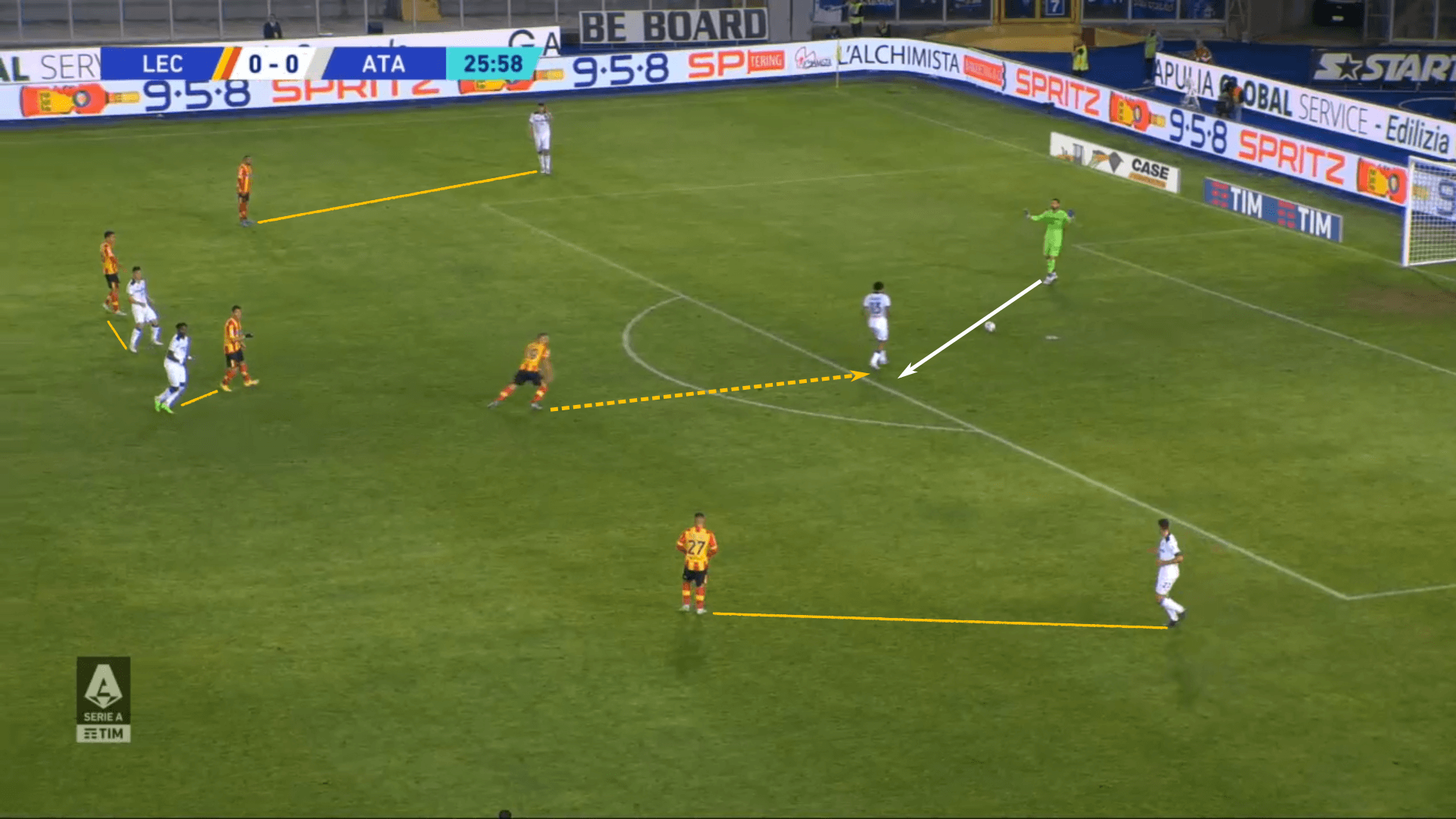

With Atalanta in a back three, Lecce kept three forwards in close proximity to the opposition’s back three. To limit entry into midfield, they also man-marked both pivot players. Other than the goalkeeper the next most available player was Memeh Caleb Okoli, the central player in the back three. As the only realistic short option, Atalanta funnelled play into him.

That’s exactly what Lecce had hoped for.

Marco Sportiello’s pass into Okoli was the pressing trigger. Notice his poor body orientation as he receives the ball. His two options are to touch the ball away from pressure and attempt to play forward or set a risky pass back to his keeper. This approach is specifically designed for a back three. The pass into the centre-back, especially from the goalkeeper, comes from a poor angle and limits the centre-back’s ability to properly orient his body for his next action. Further, since he’s facing his goalkeeper, pressure is now coming from his blind side.

The passive high press is often used to funnel play into specific players. This is an example of a positional trigger. As the central player in a back three, Okoli’s body orientation would mean receiving from his goalkeeper was a vulnerability Lecce could target.

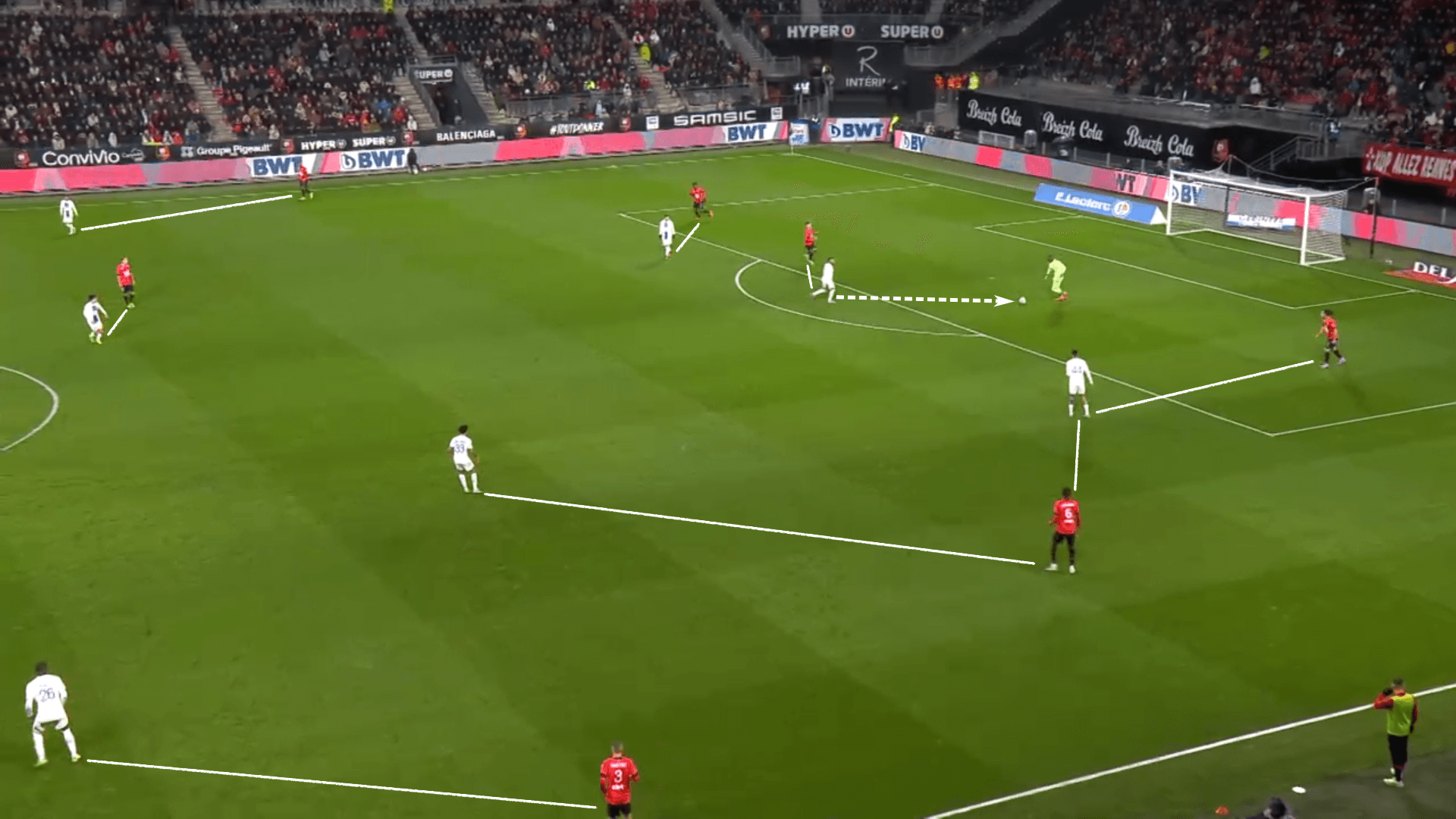

Another approach is to gradually force the opposition into deeper areas of the pitch. It’s very similar to the scenario in the first section, except here, the pressure on the first attacker is less intense. The sequence of negative passes tends to be more gradual in the space between the out-of-possession team’s forward line and the in-possession team’s backline or goalkeeper is gradually nullified. As PSG pressed Rennes, the defenders were virtually in line with a goalkeeper, cueing PSG to apply pressure now that the distance to the first attacker was shortened.

The first two examples showed us positional targets, both from deeper areas of the pitch. Another approach is to funnel play into the opposition’s weakest or most error-prone players. To set up this trigger, the pass to the targeted player must be the most appealing option for the attacking team. In other words, the targeted player should be the only realistic option to play into. Once the ball arrives at his feet, intense pressure is designed to take the ball off of him.

Returning to a more positional interpretation of the high press, effective teams are more likely to eliminate, or at least restrict, access to the central channel and half-spaces. If the opponent can receive centrally with a forward-facing body orientation, he has the full picture of the pith at his disposal. However, if entry into those central players is denied, that forces the opposition to look at long-range targets.

Take this Athletic Club example. The two centre-forwards repositioned closely to the two centre-backs. As the space between the forwards and the goalkeeper closed, Athletic Club engaged the opponent, rushing his delivery forward. The sudden appearance of pressure led to a rushed decision to go Route 1 rather than attempt a long diagonal into the wings. The result was an Athletic Club recovery in their defensive third.

Most teams will attempt to take away the centre of the pitch because the opponent has more options from that position. More options mean less predictable attacking play, which runs counter to defending teams’ wishes.

However, central recoveries are also more likely to lead to shots and goals. If done right, funnelling the opposition centrally can lead to a lucrative chance on goal. Let’s talk about some of the keys, looking at Inter Milan and Rennes for examples of well-executed high presses.

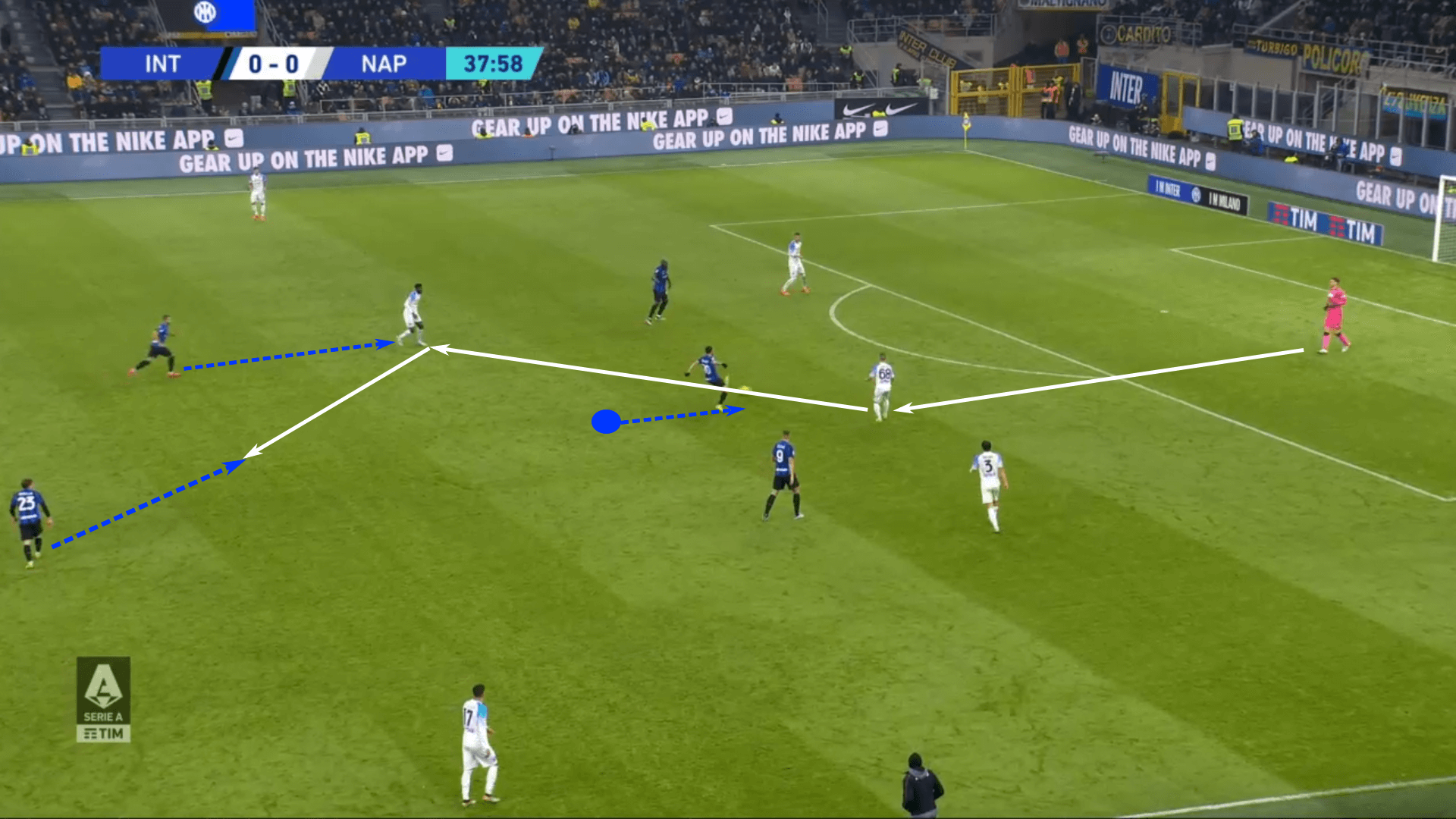

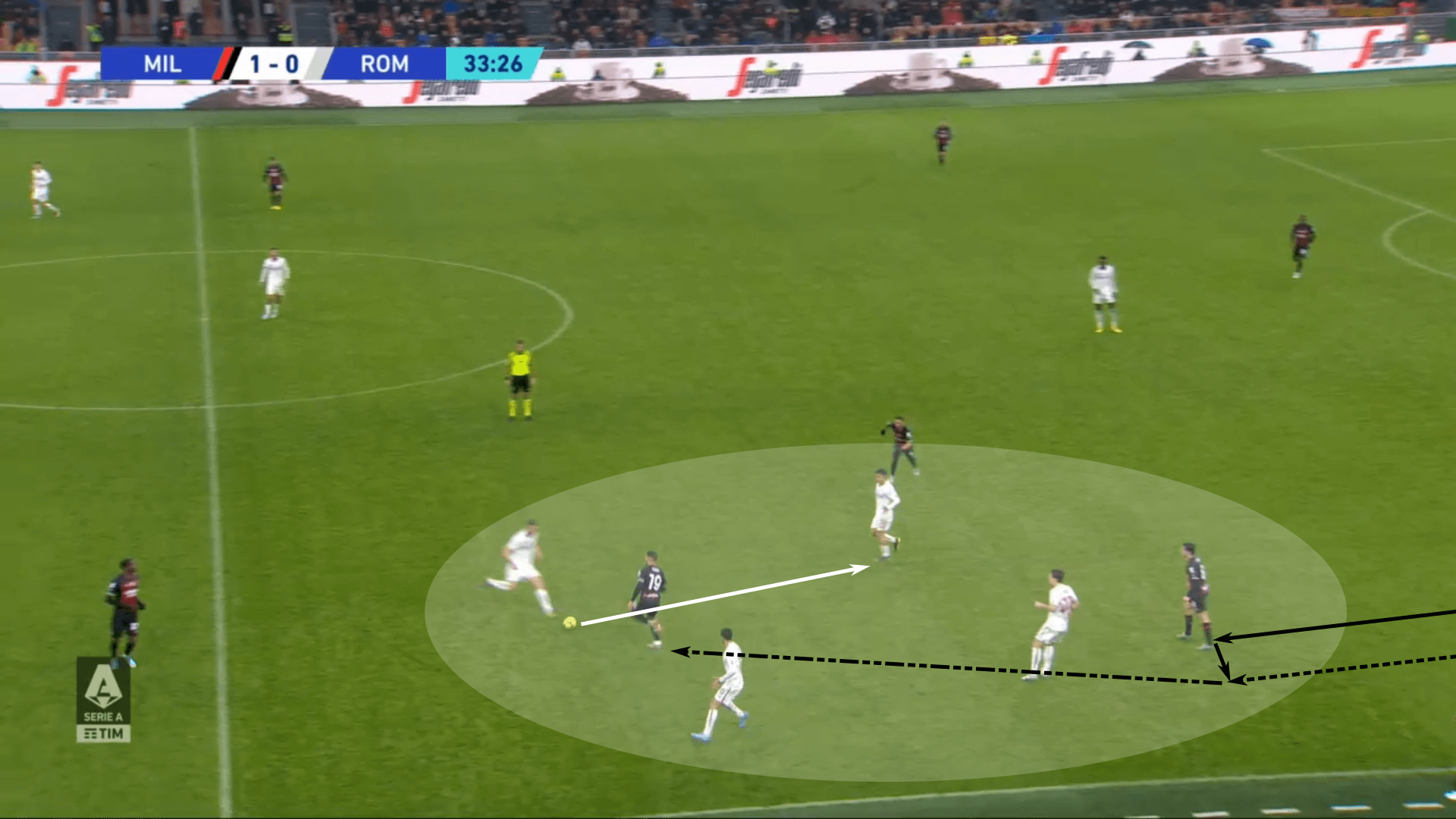

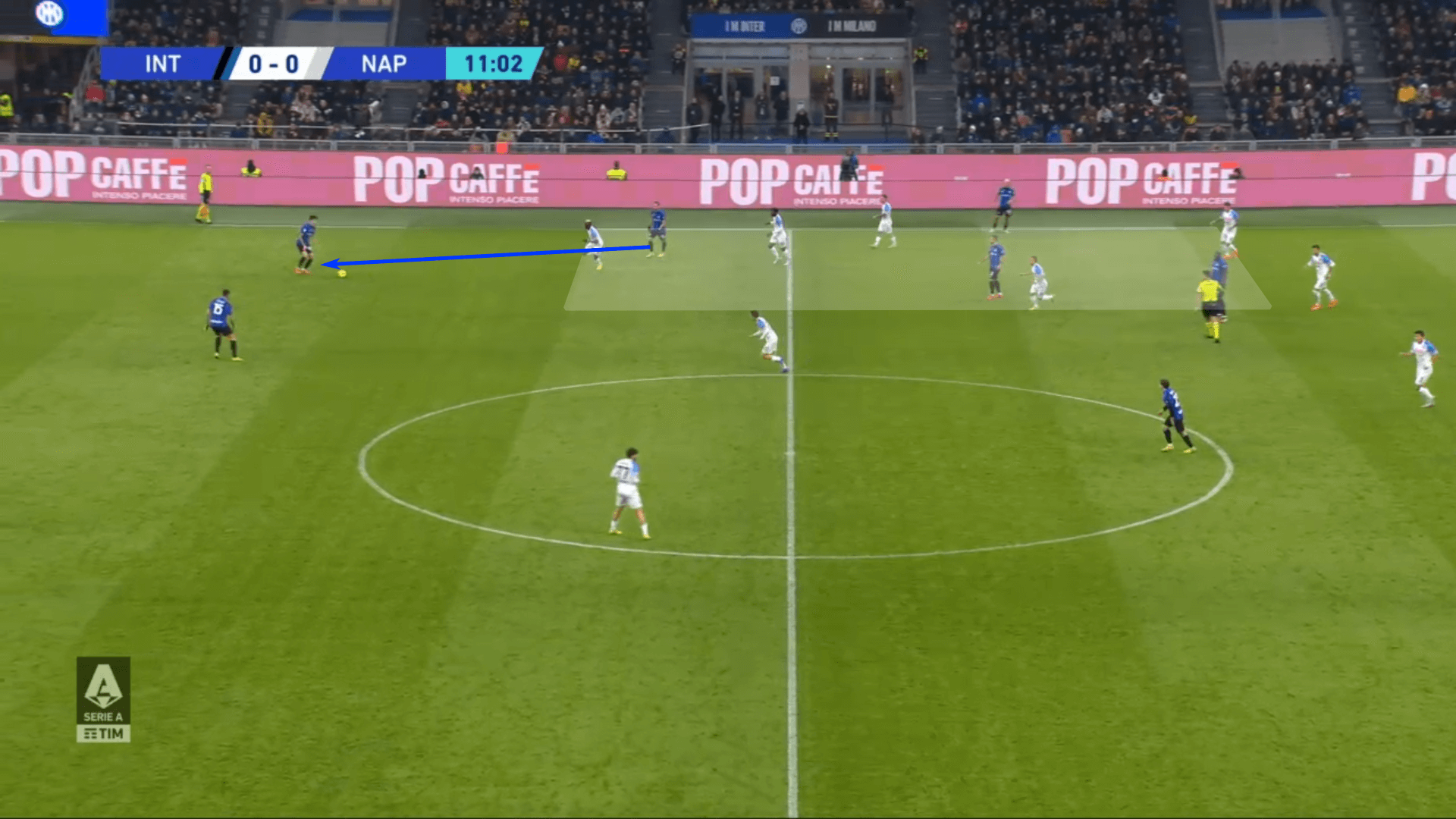

Starting with Inter, we have a very similar situation to the Lecce high press. It’s a pass from the goalkeeper to Stanislav Lobotka, the Napoli holding mid, that triggers a response from Inter. Receiving a straight pass limits the quality of the receiving player’s body orientation. It’s a clear pressing trigger. Inter does well to apply pressure on Lobotka who chooses to play forward instead of back to his goalkeeper. The only issue is that André Anguissa had closed himself off from the majority of the pitch as well. His poor body orientation and decision to play a one-touch pass into the central channel resulted in an easy recovery for Nicolò Barella and a counterattacking opportunity for the hosts.

For Rennes, the first pass is played in the left half-space, but the third runner is making his way through the central channel. It’s the third player who will orchestrate PSG’s movement into the attacking half of the pitch. Though the positioning is different in this example, the spacing from the second attacker is very similar. In both instances, the first pass is almost a given. For Napoli, so was the second. However, it’s that next pass that results in a turnover. The passive high press allowed the opposition to target a checking player with poor body orientation and limited support, reducing the number of variables. As the opposition broke the first line, the pressing intensity increased, which tells us the pressing trigger was in place.

In both instances, the player who lost the ball was trying to force play centrally and had poor body orientation, limiting his vision and awareness of the opposition’s numbers.

Limited support underneath is also a critical factor. This is especially the case when the attacking team’s backline attempts to send line-breaking passes. Take for example Lecce trying to target the space between the lines. Atalanta is well prepared for the sequence. The receiving player has limited options. There is the set pass into midfield, but a nearby opponent is close enough to make a play on the pass. The other option is to attempt to turn, which is likely to end in a dispossession anyway.

Given the poor attacking scenario for Lecce, Atalanta was very aggressive moving forward into midfield. A poke at the ball allows them to recover it centrally.

The key to Atalanta’s success is Lecce’s limited options to retain possession. Gasperini’s side has numerical quality near the ball and two nearby players in support positions. You could even say they held a 5v3 advantage in this part of the pitch. When a numerical advantage is intact, baiting the opposition to play into it benefits the defending team. This is especially the case when the backline is comfortable stepping aggressively into midfield with the opposition’s forwards.

In these last couple of examples, we’ll transition to a discussion on funnelling into the wide areas. The key reasons teams will funnel the opposition into the wings are to limit the number of outlets for progression, use the touchline as an additional defender and seal the opposition into one area of the pitch.

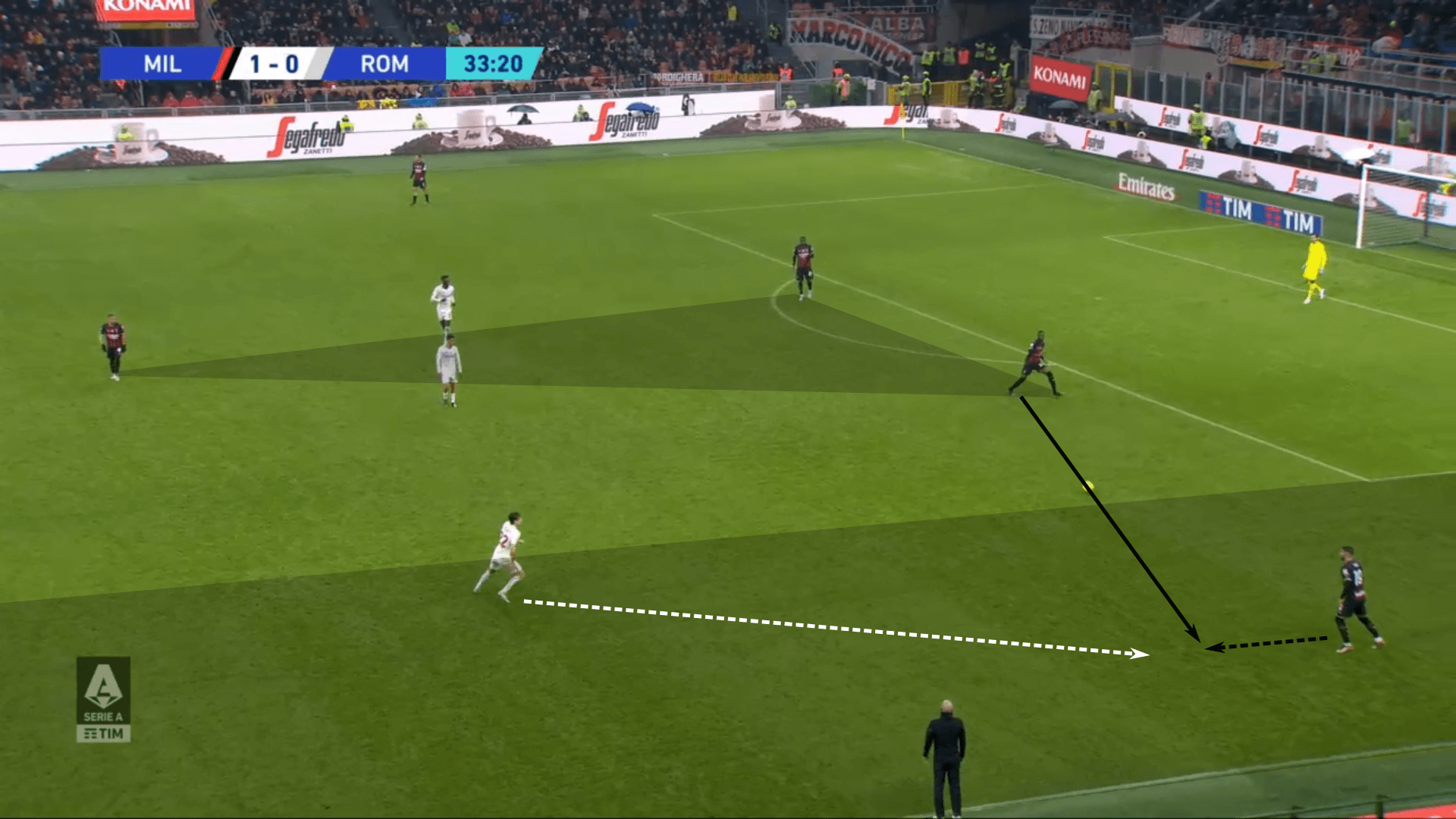

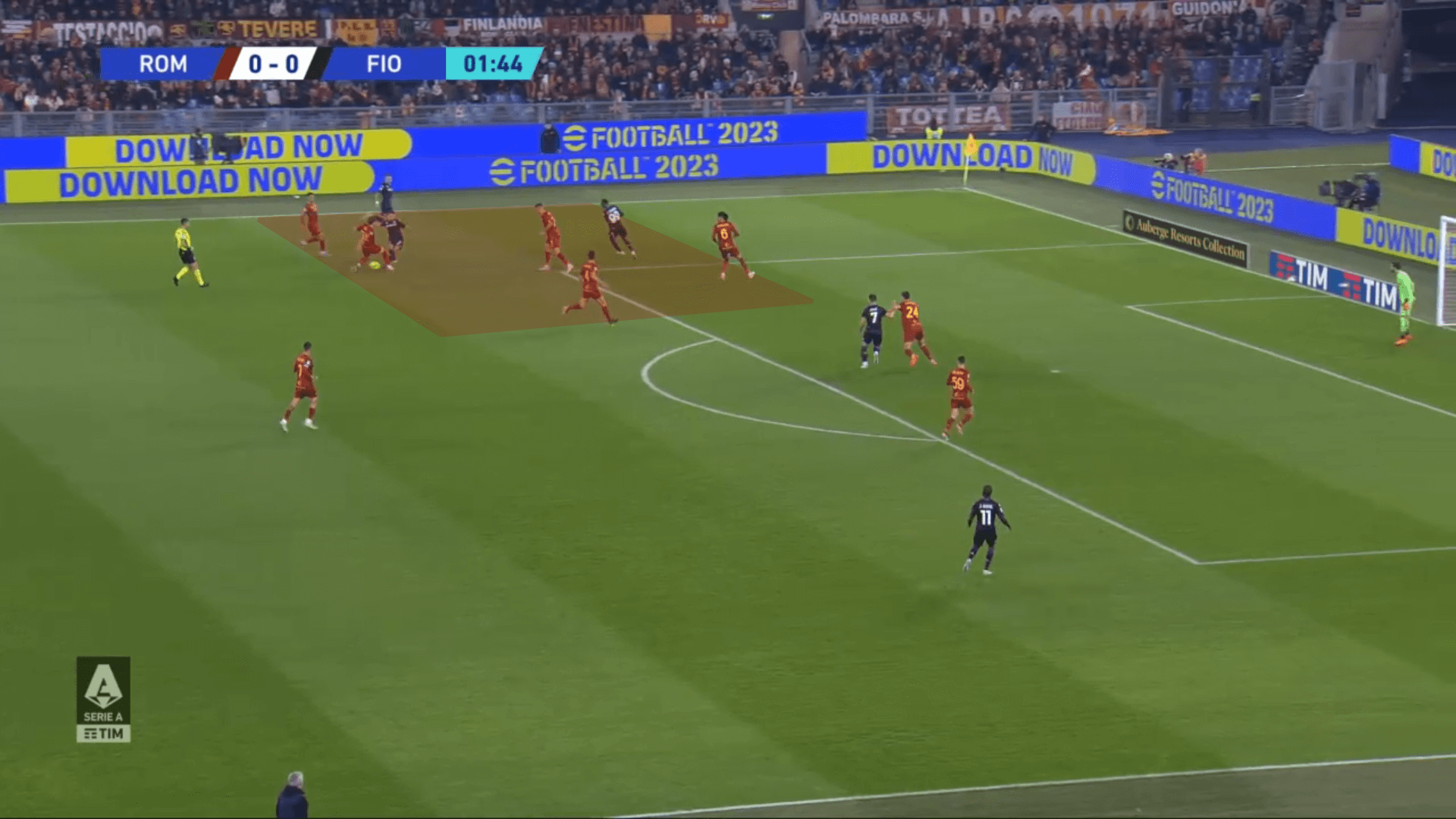

Perhaps no one in the game is better in this area than José Mourinho. An analysis of his Roma side shows that the wide pass is virtually a given. Once the pass is made, pressure on the first attacker is applied. Notice the two central players limiting the angle into the AC Milan holding mid. The next pass is not going central given the risk associated with that pass. It’s clearly going out to one of the two wings.

Once the ball is played to the left wing, the pressure defender makes it a 1v1 scenario. He doesn’t fly at Theo Hernández. Rather, he gives him the pass down the line to his checking teammates. The ball is passed forward and a give-and-go is attempted before it is turned over.

Notice the area of engagement. By the time AC Milan gets into the middle third, the true 1v1 they had seconds earlier is now a 4v3 favouring Roma. Additionally, the space is very tight. As space reduces, the angles to play out of pressure are also smaller, as are the distances between the defenders and attackers.

Roma offers an example of funnelling playing to the wings and sealing the opposition there. With limited options to play out of pressure, the attacking conditions give immediate feedback to the defending team. Space and angles are tight, so ramp up the intensity of the pressure.

The Roma example gives us a recovery in the wing. However, funnelling the opposition into the wings doesn’t necessitate a wide recovery. Instead, if options to play backwards are out of the equation, that pass into the wing can be designed for central recoveries. It’s not the pass into the wings that the defending team expects to recover. Rather, it’s the next pass.

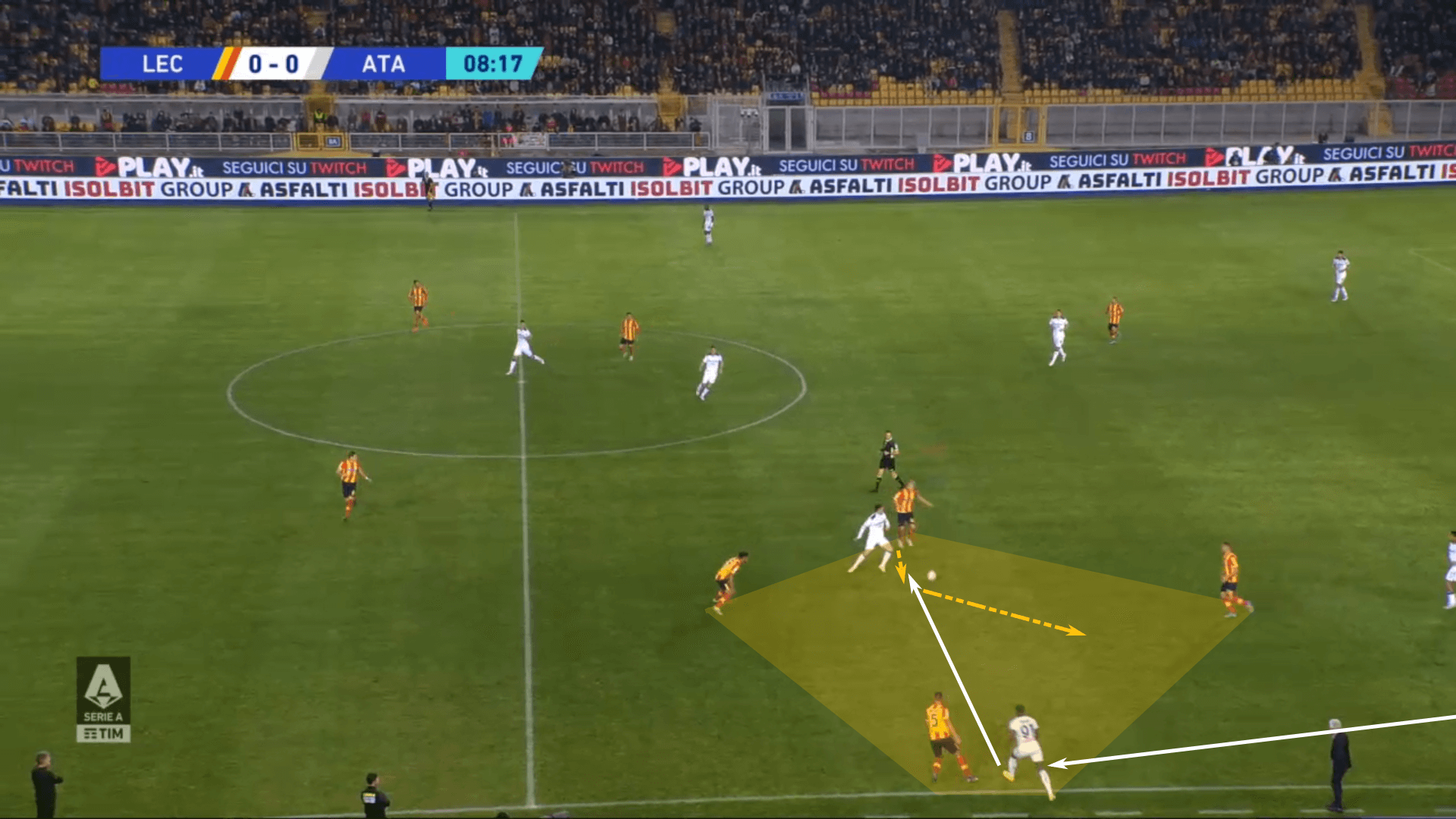

Let’s turn to our last example in the section. Atalanta has played high into the wings and has limited options to play a negative pass. Lecce plays the scenario perfectly. At first glance, the pass into the half space looks uncontested. However, Lecce has numbers around the ball and is close enough to the second attacker to move to him as it pass is played.

Lecce’s recovery shows us that funnelling opponents to the wings doesn’t necessarily force teams to aim for a wide recovery. Rather, that wide pass itself is a mechanism for a central recovery. Baiting the opposition to set a negative pass into the half spaces or do attempt a lateral distribution can pay huge dividends.

Whether pressing inside or outside, funnelling play to a positional vulnerability or into the weakest link on the opposing team, passive high presses are highly adaptable and profitable. Each match may see slight modifications to match the tactics of the opposition, adding a layer of unpredictability to the approach.

Mid-block objectives

Time to move to a deeper part of the pitch. Let’s have a look at teams setting up in a mid-block.

Much like a passive high press, one of the objectives of the mid-block is to use positional superiority to dictate where the opposition can play and limit their access to more threatening parts of the pitch. Setting up in a mid-block does not require immediate pressure on the ball, instead placing the priority on structural cohesion.

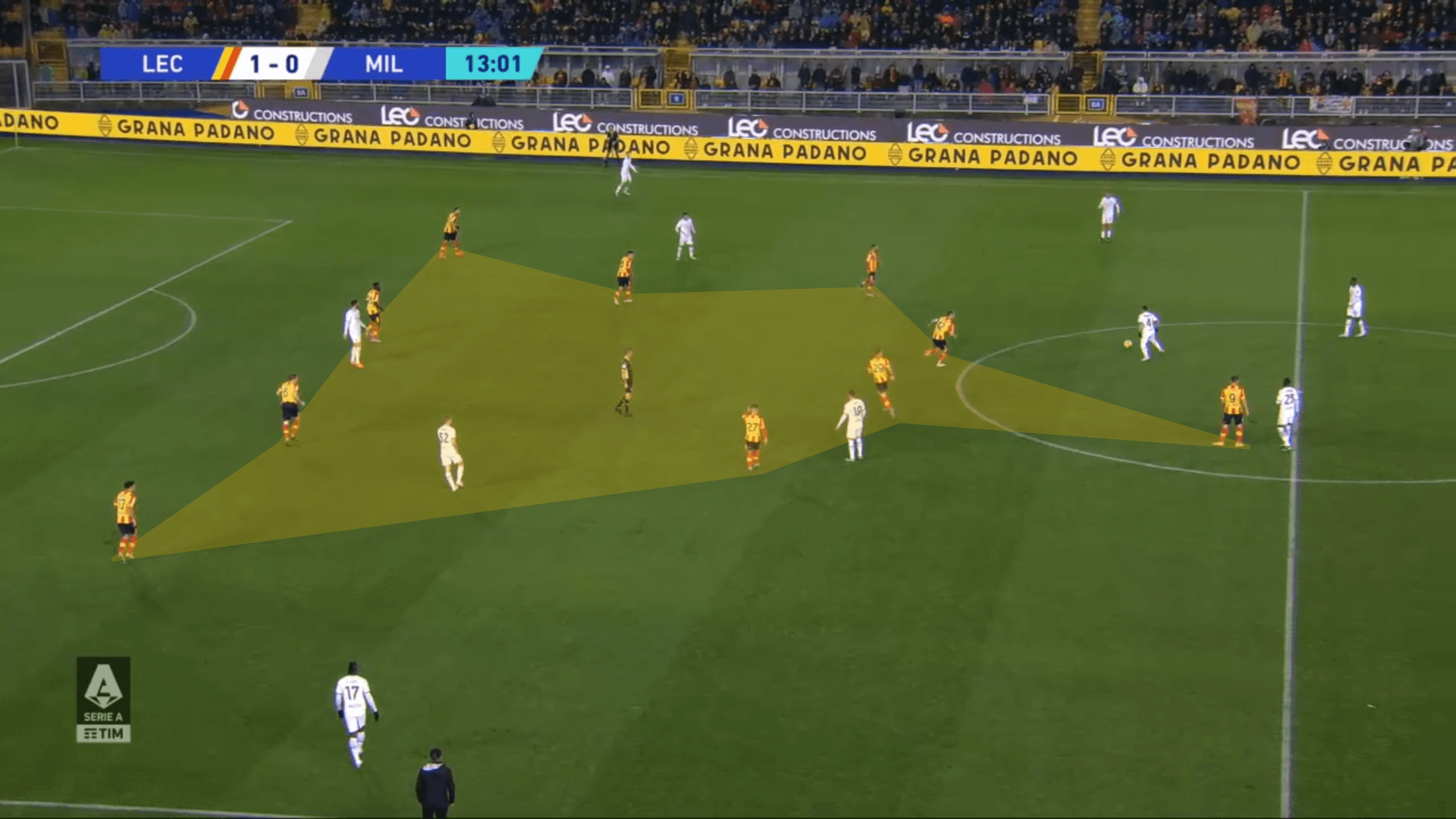

Dominating the centre of the pitch is typically the highest priority. Limiting the opponent’s access to Zone 14 and funnelling play into the wings makes defensive work more predictable. Perhaps the best-case scenario is reducing the opposition’s attack to a barrage of crosses, provided the defensive team is prepared to defend against them. We see this type of approach in our first image with Lecce dominating the central channel, leaving just the two outside-backs in the half-spaces.

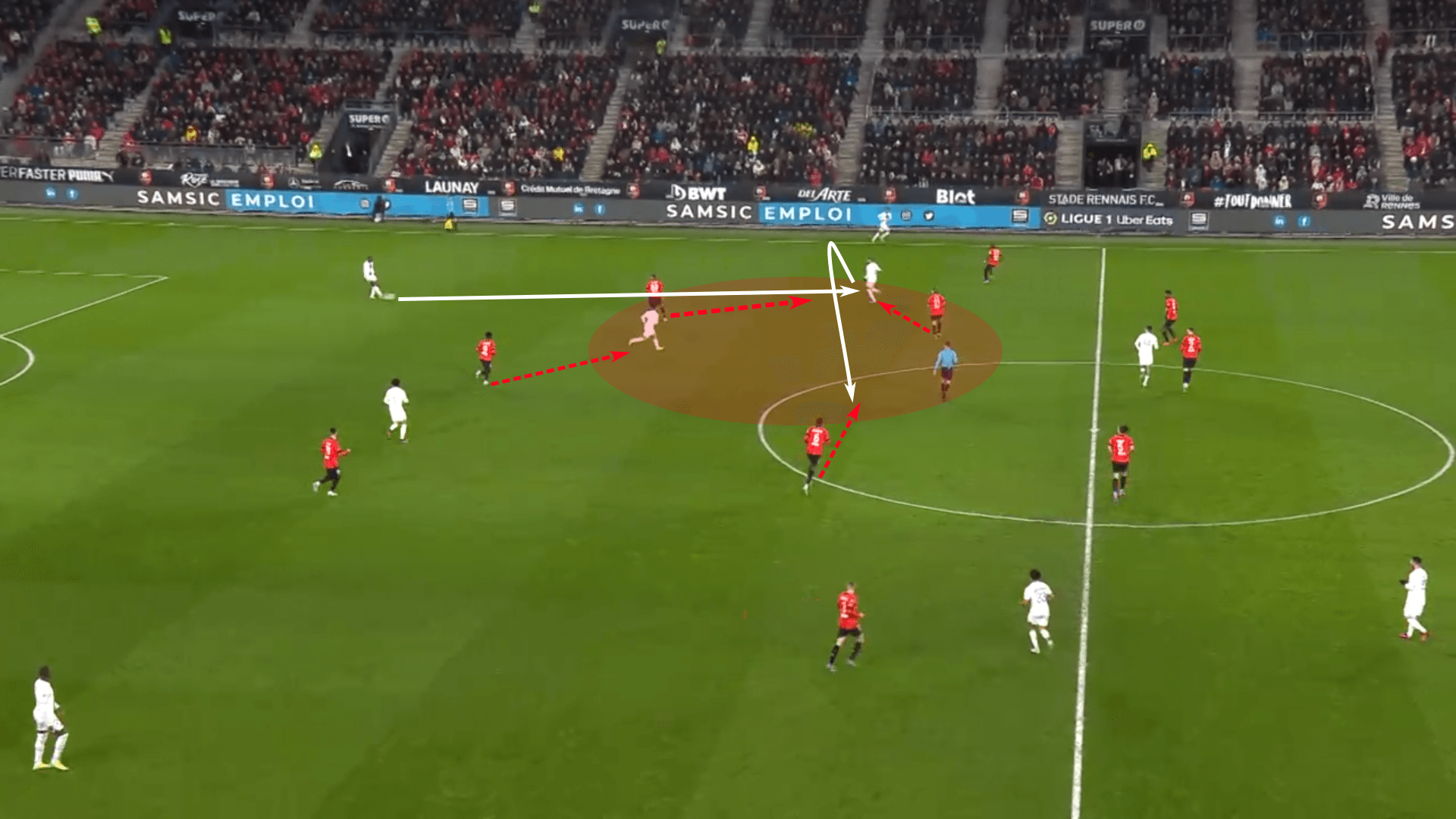

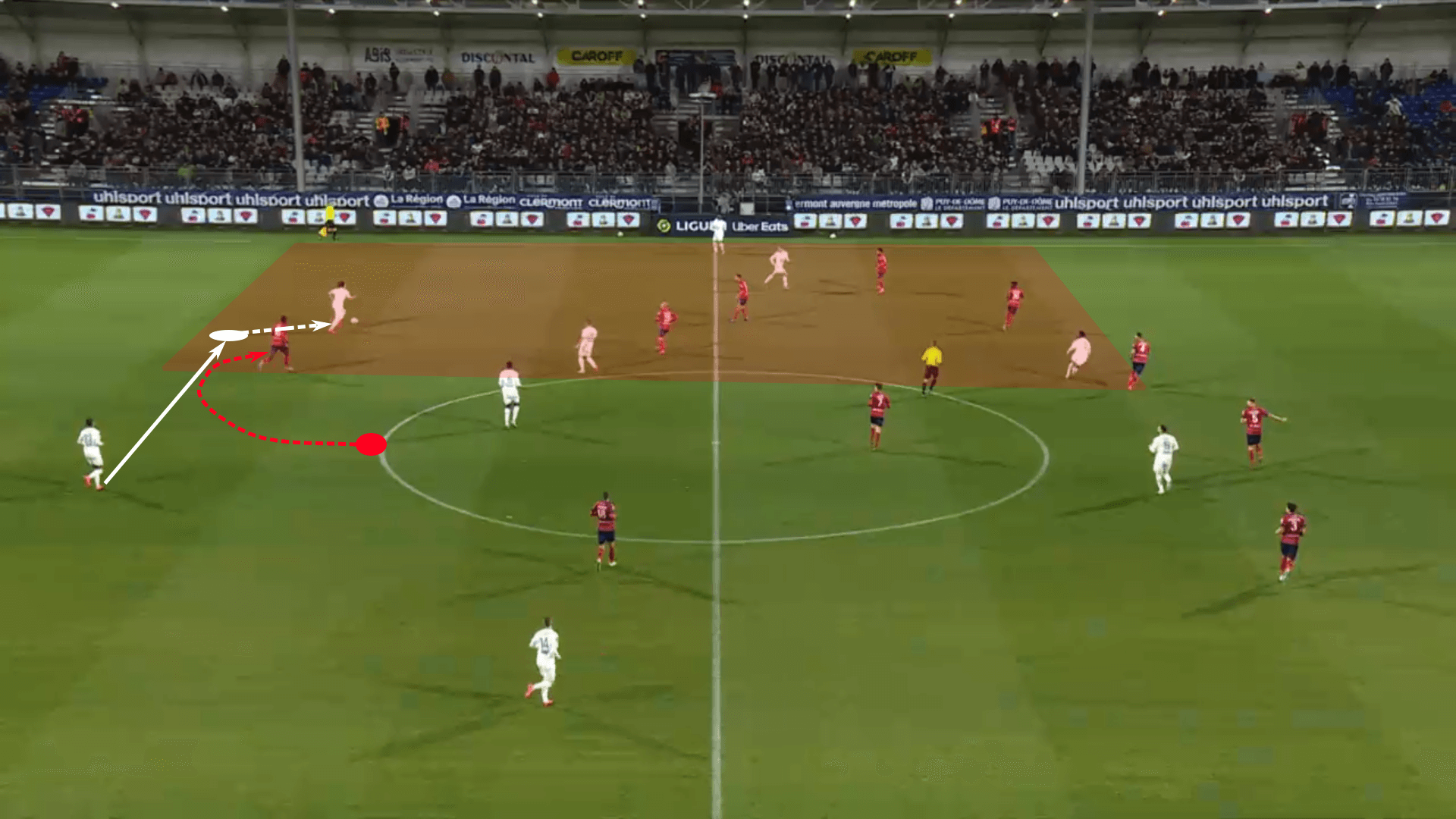

Once the opposition play to one of the wings, the goal is to keep them there. Though Rennes was the case study, Clermont Foot gave an excellent example of committing the opposition to one side of the pitch. As Clermont sat in a mid-block against Rennes, Les Lanciers patiently waited for one of the two centre-backs to commit to one side of the pitch. Once a commitment was made with Arthur Theate driving into the left half-space, Clermont was able to shift their lines to their right while Grejohn Kyei moved between the two centre-backs while chasing down the first attacker. His job isn’t to win the ball back, but two keep pushing Rennes further to the left side of the pitch.

While positioned centrally and waiting for the opposition to progress through the wings, a slow tempo will help limit the physical exertion of the defenders and allow the team to make a radical shift in tempo once the balls worked wide. Disrupting the opponent’s rhythm with drastic changes of tempo can lead to slow decision-making and sloppy execution.

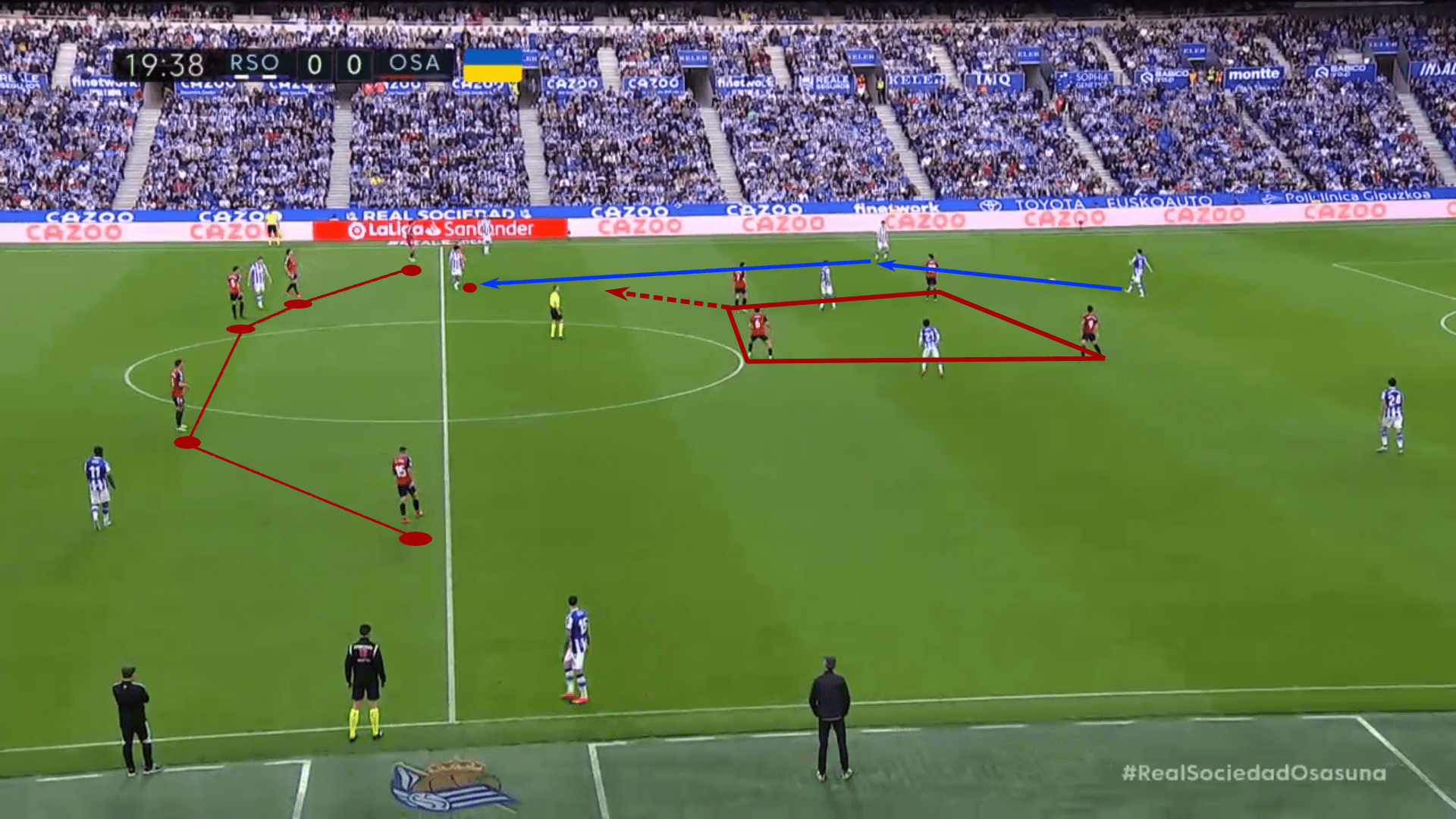

Osasuna used a disruption in tempo to catch Real Sociedad off guard. Once the ball was funnelled into the wings, the four highest players on the pitch shifted to the left wing and half-space. As Real Sociedad looked to play their way through the Osasuna press, Los Rojillos ramped up the intensity of their actions, quickly reducing the size of the playing area and applying heavier pressure on the first attacker.

From an attacking team’s perspective, there’s nothing wrong with wing progression. That’s often where there’s more space to penetrate, so it’s easiest to advance the ball in those areas.

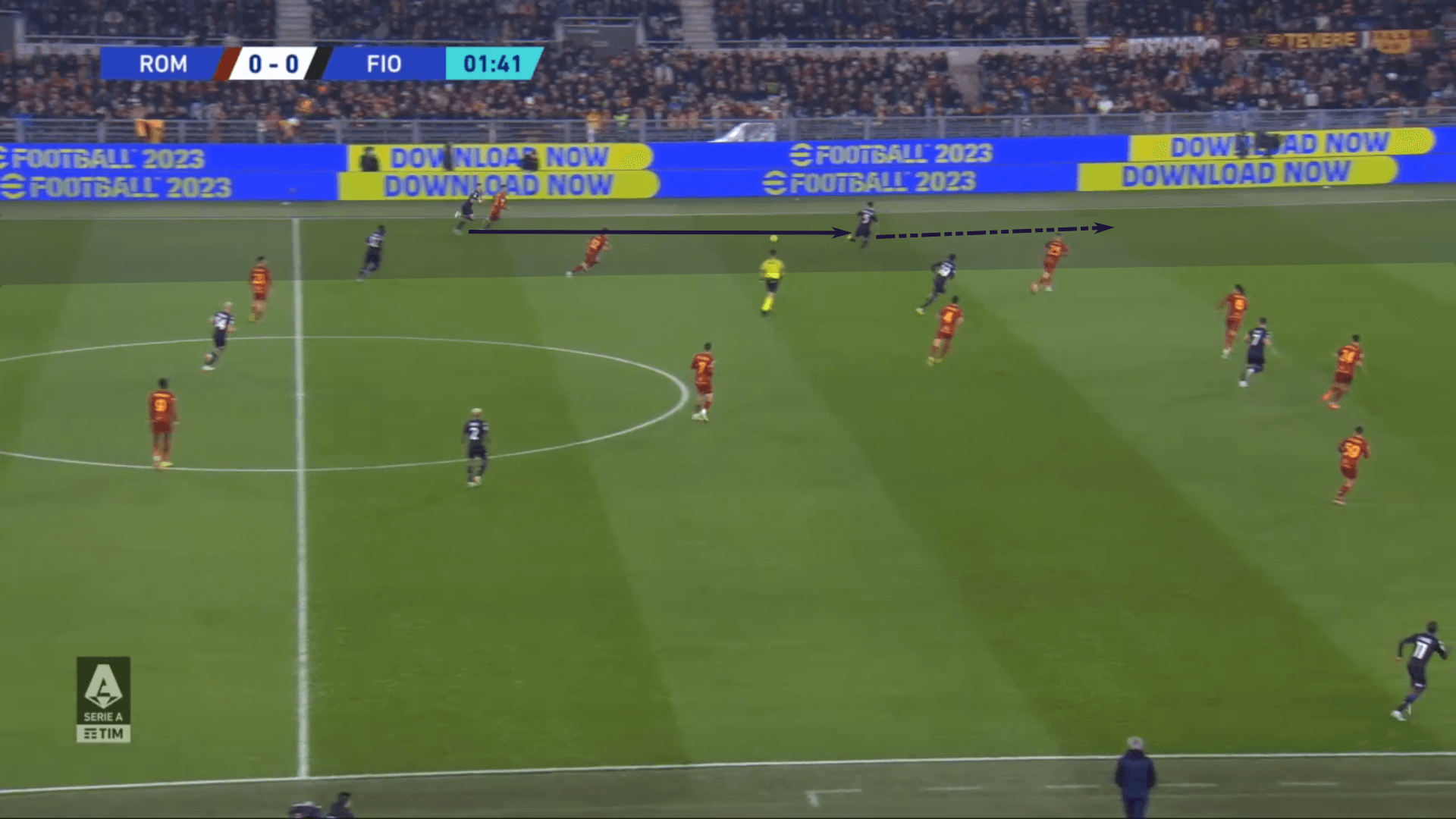

On the flip side, clever managers like Mourinho are masters at funnelling the opponent into the wing and sealing them there. Take this example from Roma. Play was switched and the ball was immediately played forward into the wing. There’s loads of space as the sequence begins.

The first defender does well to delay the attack, allowing Roma to get numbers near the ball. In just three seconds, a 1v1 became a 5v3 and Roma’s favour. The quickness to seal the opponent into that 15×12 m area eliminated all opportunities to break the press. In a sense, offering the wing progression was a means of shifting play into a less threatening area and creating a numeric overload near the ball, taking away Fiorentina’s options to break the press.

Following play into the wings is essentially a way of protecting the centre of the pitch. By forcing opponents into the wide regions, they are forced to attack from less threatening positions and with fewer outlets back to the centre.

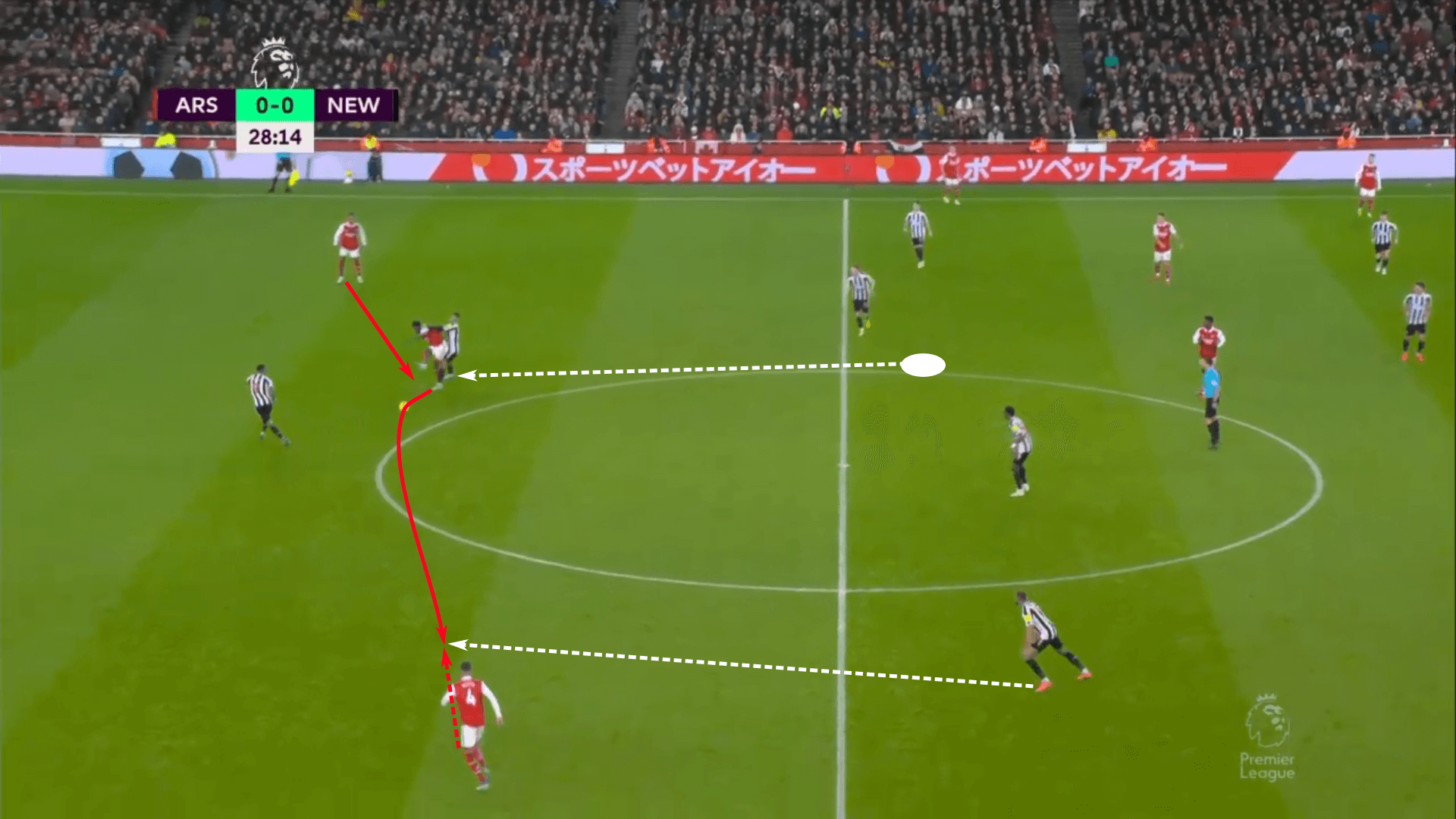

When playing against possession-dominant sides that excel in central penetration, such as Arsenal, another set of tactics you may find is dropping the midfield deeper to limit the space between them and the backline. By taking away the space between the lines, the opposition is more likely to settle for wing progression or move their creative players in front of the midfield line.

That’s precisely what Eddie Howe’s Newcastle side did against Mikel Arteta’s Arsenal. There was very limited space for the Gunners to attack between the lines, which forced them to push numbers in front of the Newcastle midfield. As Arsenal circulated the ball along the back, Newcastle’s midfielders looked for opportunities to push forward and pressure the first attacker. Their 4-5-1 setup transitioned into a momentary 4-4-2 as the midfielders stepped up to apply pressure. In this instance, the pressure was just enough to force a bad pass leading to a turnover.

One of the keys here is that the out-of-possession team always defends from a position of strength. As Arsenal passed the ball along the back, each pass wasn’t a cue for a new midfielder to step forward. Rather, they only stepped forward to apply pressure once the line itself was secure, meaning there were typically four players positioned to deny line-breaking passes. Had a new midfielder stepped forward with each pass, gaps would have opened up in midfield, allowing Arsenal to pick apart the Newcastle midfield.

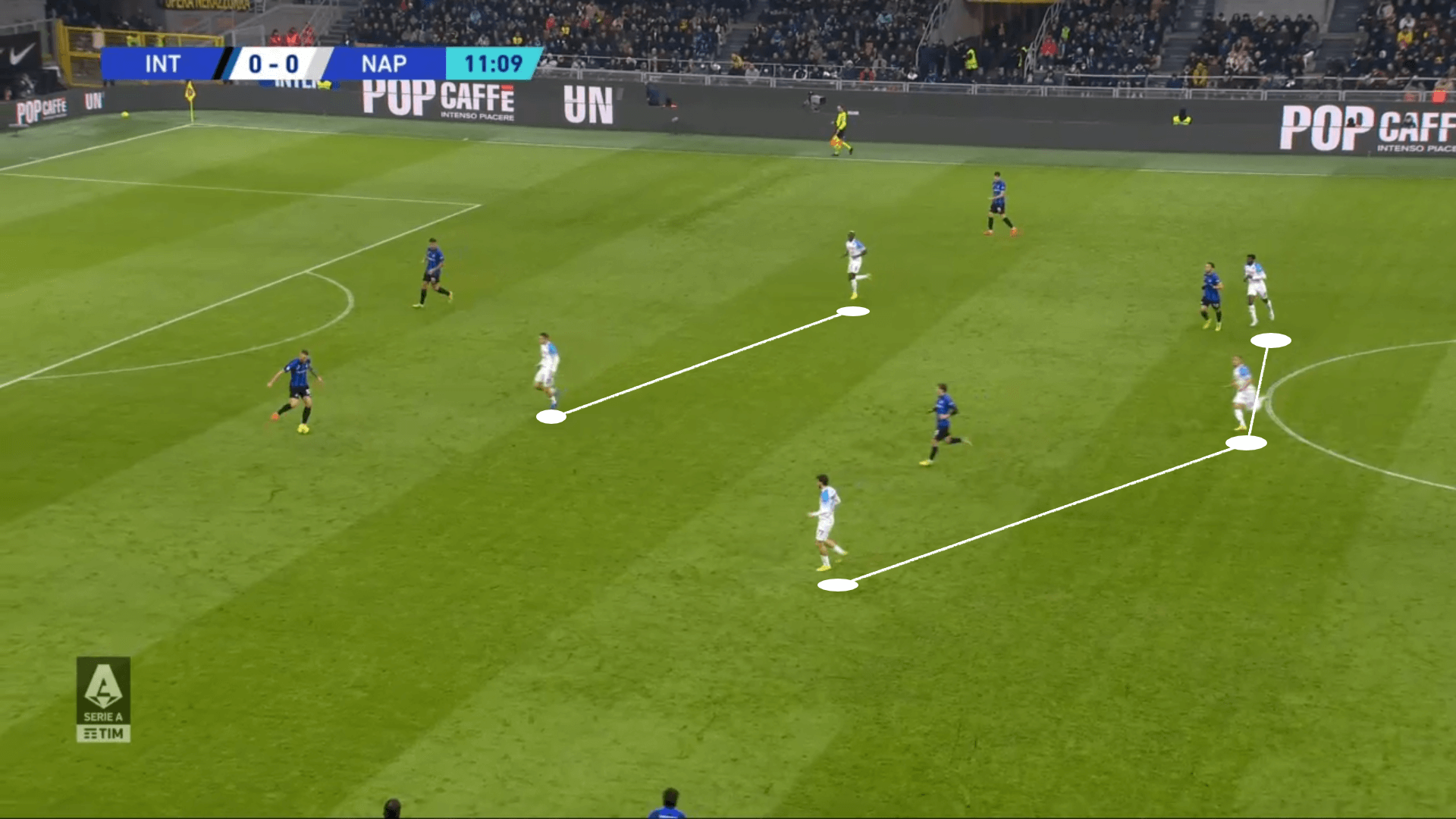

For the final example of this article, we’ll look at how a team should react when the press is beat. In this instance, we’re looking at Napoli in the white. They did well to funnel Inter Milan into the left-wing, but then couldn’t keep I Nerazzurri from playing a negative out of the press.

Rather than slowly shifting back into their central positions, Napoli kept their high-tempo press, leading to a sequence of negative passes from Inter. With each backward pass the first defender chased, each of his teammates was gifted a couple of spare seconds to recover into the team’s default mid-block. The hustle of the first defender gave his team an additional seven seconds to recover their shape and start the process over again. Without the work rate of the first defender and the follow-up movement of his teammates, Inter Milan would very likely have had the opportunity to switch the point of attack.

As this analysis has shown, the mid-block is a structural approach to funnelling the opposition into less threatening areas and reducing the amount of space they can work with. Without the threat of balls played behind the backline and the central dominance secured by the compact structure, play becomes more predictable. This is especially important when the opposition has dynamic attacking players or an overall qualitative advantage. Reducing the space and time they have to work with limits the types of opportunities to play forward.

Conclusion

This tactical theory has examined different forms of engagement, looking specifically at the moments that trigger action.

Well-executed defensive tactics dictate play by showing the opposition where and when they can go. Whether in the heavy metal, full-pressure high press or the more nuanced, harmonic movements of the passive high press or mid-block, defensive tactics are designed to disrupt the opposition’s rhythm and reduce their play to the predictable.

There’s something beautiful about a well-orchestrated press and the team-wide tactical discipline required to carry it out. We hope that this analysis has helped you better identify the underlying principles of the press and the moments of engagement that make them work.

Comments