Football offers a lot of different attacking tactics, and whereas the concept of overloads and the approach of positional play have become quite popular, asymmetrical shapes are a less popular phenomenon although they do offer some potential.

Asymmetrical shapes are often used as a combination of positional play and overloads. In this case, the overloads are not created through heavy shifting towards a certain area, but the shape creates a natural and constant overload in a certain area of the pitch.

This tactical analysis deals with the advantages and disadvantages of the usage of asymmetrical shapes. Therefore, we are going to reveal the tactical consequences of asymmetrical shapes and take a look at some teams, such as Peter Bosz’s Bayer Leverkusen using this concept.

Asymmetrical shapes with hybrid players

There are several reasons for the usage of an asymmetrical shape. One of the most common reasons is the fact that a team is lined up with different player types. For instance, while one full-back might like to move forward on the wing during the attacking phase, the other one might be a better build-up player in deeper areas. As a consequence, it can be sensible to avoid forcing players into roles they are not able to fulfil and instead use their strengths by giving them a role that suits their skill set.

Often, asymmetrical shapes are used to define the area of action for full-backs and wingers. Whether they mainly act within the half-space or on the flank can make a huge difference. When teams use asymmetrical shapes, they often lineup so-called hybrid players taking over a different position during the attacking phase, then when defending or vice versa.

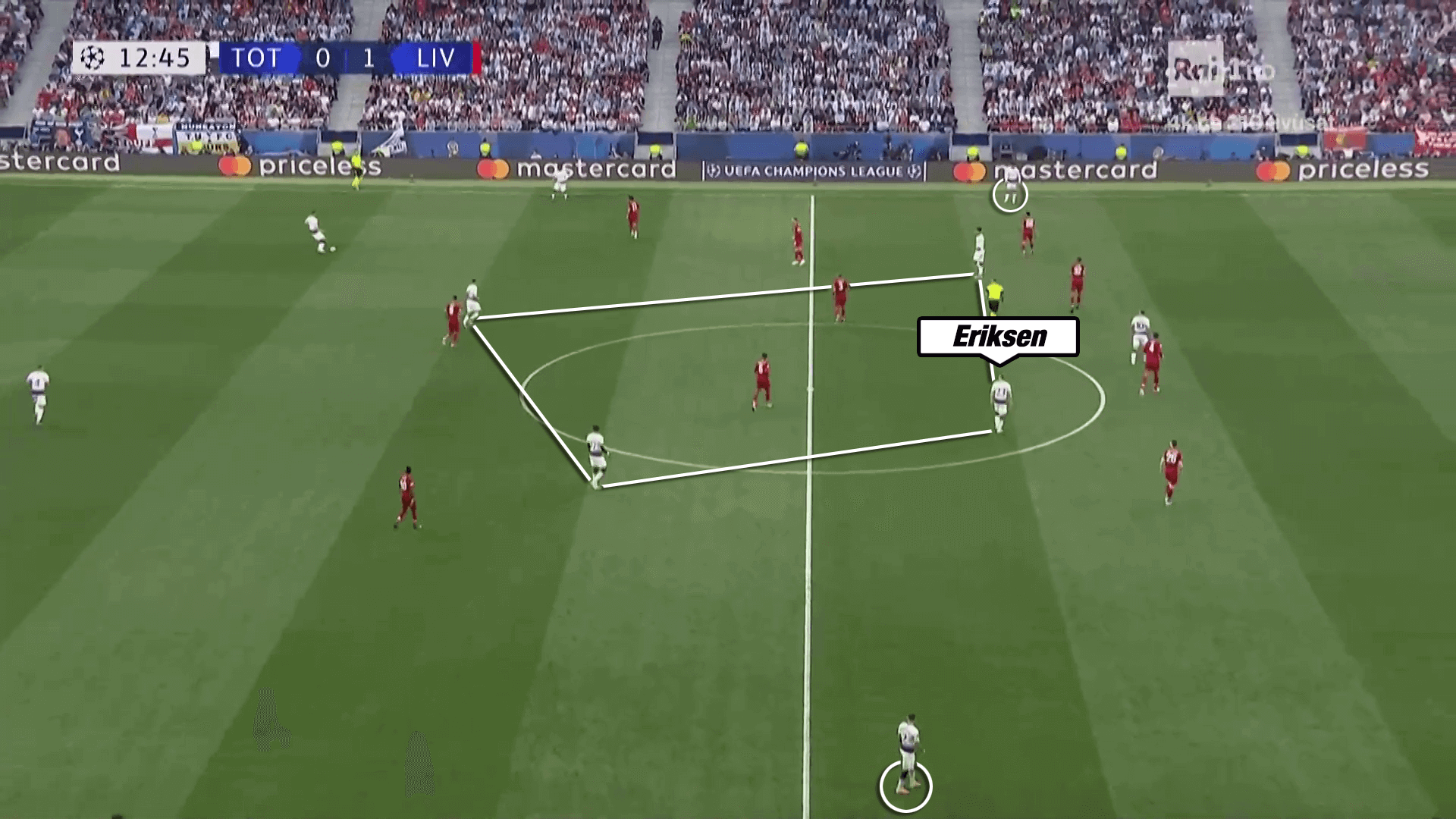

A common example for a hybrid player are wingers who act as central offensive midfielders in possession. Although pressing and defending out wide, they move inside during the possession phase. Tottenham’s Christian Eriksen is one example. Eriksen’s playmaking abilities can help Tottenham in possession. Therefore, the Danish attacking midfielder acts centrally during the attacking phase. In Tottenham’s Champions League final against Liverpool, this created an asymmetrical shape as can be seen below.

Whereas their left side was occupied by two players, their right side was only occupied by right-back Kieran Trippier as Eriksen moved inside.

As a consequence, Tottenham overloaded the centre of the pitch and Liverpool had to heavily shift in order to defend Tottenham when they attacked down their left side. In this particular case, the outcome was not great since Liverpool are following a ball-oriented defending approach anyways, and Trippier was not a big threat after switches.

Against a space-oriented defending approach

Any action in football is followed by a consequence. The same goes for the usage of asymmetrical shapes. If the attacking side deploy an asymmetrical structure, the defending side are forced to a reaction. Either they will attempt to adjust their shape in order to still gain a numerical superiority or at least equality in certain areas, or they will have to defend with fewer numbers. A change in shape is not always made by the coach but can also happen due to the players’ behaviour. A central midfielder, for instance, could shift further towards one side intentionally due to the positioning of the opponents.

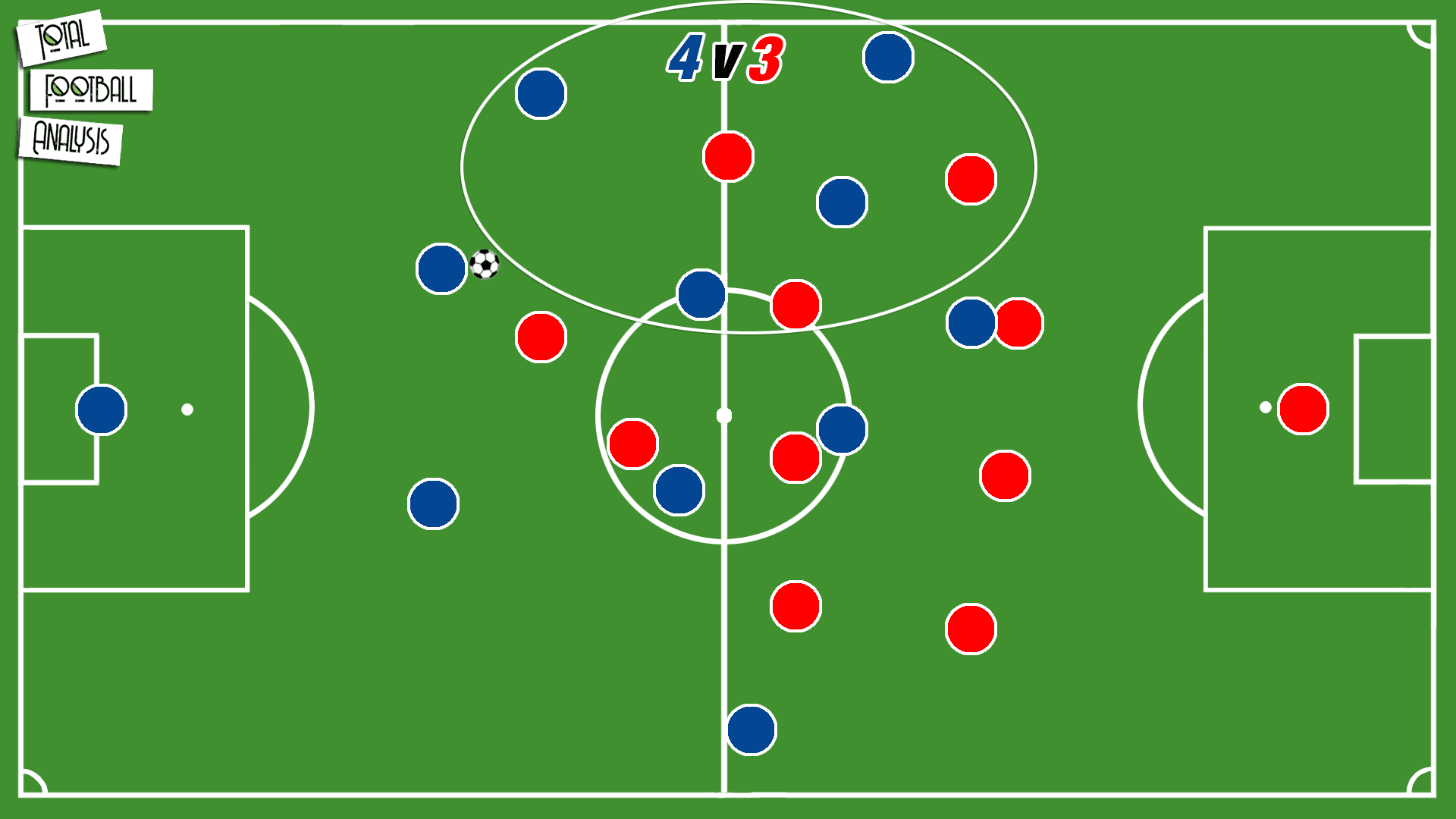

When using an asymmetrical shape against a space-oriented defensive side, the opposition might not adjust their defensive shape though. As a result, it is possible to create natural overloads on one side while having an underload on the other side. Below, we can see how the team in possession have a 4v3 numerical superiority on the ball side. This is a result of their asymmetrical shape with two wide players on the left and only one player on the right side.

Depending on the opposition defending qualities, one can then either play into the area with a numerical advantage straight away or attempt to decoy the opposition by playing into the underloaded area followed by a quick switch of play.

Against a man-oriented defending approach

The more man-oriented the defending approach though, the bigger is the impact on the defensive shape. Logically, when defending man-to-man, the defending players follow their direct opponent. As a result, they automatically mirror the opposition shape, whether asymmetrical or not and therewith create a numerical equality in most areas of the pitch (most sides provide one more player than the opposition within the backline).

So why should asymmetrical shapes be advantageous against man-oriented defending approaches then? Simply because one can provoke isolated 1v1 situations, ideally with so-called “mismatches” within certain areas. A “mismatch”, in this context, means that one player is clearly superior to his direct opponent. If deploying a skilful and fast winger on one side of the pitch, it can be advantageous to drag opponents to the other side in order to isolate the 1v1 with the biggest “mismatch”.

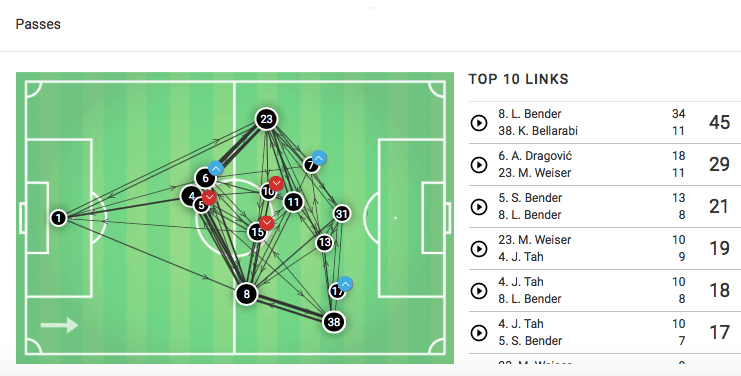

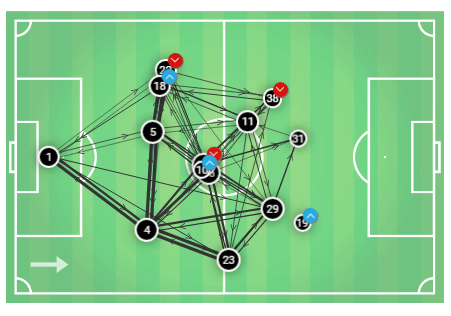

Although the man-oriented defending approach can lead to more space for the mismatch, the creation of a “mismatch” also works against a space-oriented defending approach. Leverkusen against Werder Bremen, for example, deployed Karim Bellarabi (#38) wide on the right side with right-back Lars Bender (#8) staying deep during the build-up. As the graphic below proves, Bellarabi received a lot of passes near the touchline. This allowed the fast winger to utilise his dribbling abilities in a “mismatch” against Bremen’s left-back.

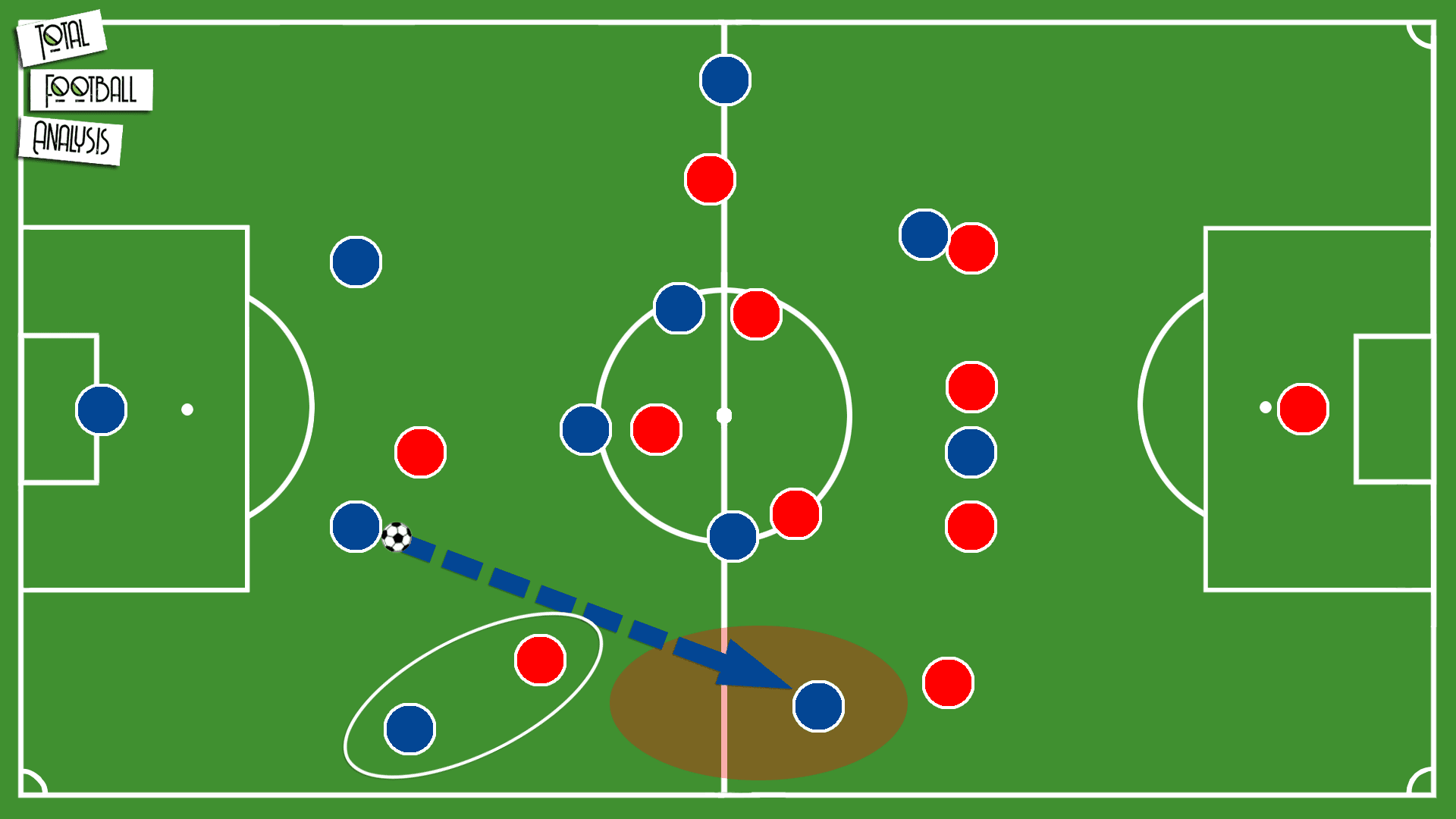

Especially in build-up against a man-oriented pressing, asymmetrical shapes can be very useful. By keeping one full-back deeper, the opposition winger will need to move higher during the press.

As displayed in the graphic above, this creates more space out wide and might even open up diagonal passing lanes towards the winger.

Possible disadvantages

As we have already discussed the advantages of asymmetrical shapes, it is quite obvious where the disadvantages of this concept lay. The advantage of having a numerical superiority in one area of the pitch can quickly turn into the disadvantage of being outnumbered in another area. This can lead to the struggle to sustain possession in the underloaded area or the threat to be caught with inferior numbers in a certain area after losing the ball. Therefore, it is not a big surprise that most sides using asymmetrical shapes are dominant in possession and often possess superior individual players.

Moreover, the success of an asymmetrical shape is dependent on the opposition. By lining up another defender than expected, for instance, the opposition might turn a “mismatch” around.

Depending on how the asymmetrical shape is formed, it could also decrease space. Leverkusen’s shape against RB Leipzig, for example, did not offer enough width. With no real left-winger, Leverkusen had no option to switch play and therefore struggled to penetrate a centrally focused Leipzig side.

As one can see on the graphic above, Leverkusen’s shape against Leipzig did not provide a left attacking side. That led to a predictability and a reduction of space which made it difficult for them to overcome Leipzig’s pressing.

Conclusion

All in all, asymmetrical shapes can create a huge advantage. The concept enables to use players in their preferred roles while also holding the advantage to purposefully create numerical superiorities or inferiorities in certain areas of the pitch.

Nevertheless, the usage of a constantly asymmetrical shape requires the ability to sustain possession as it also possesses weaknesses with its underloads in certain areas. Therefore, it is a tactical tool which is mainly utilised by top sides and which is more complex than the positional play or attacking overloads.

Comments