This month I have finally gotten round to writing part two to my previous analysis on the transferable elements between American football and football set-pieces (soccer to some). When originally planning the first article, I had planned to detail specific plays used in the NFL by teams, but became side-tracked by skills on the individual level within the NFL, with so much detail being available on how to create separation from a player, or oppositely to stop a player creating separation from you. In part two then, it is only right to go back to that idea of actual set plays in American football and how they can transfer into set plays in football.

Plays from other sports make up a big part of my set-piece ‘philosophy’, and using ideas from other sports is something which I do often when consulting around set-pieces. Therefore, this tactical analysis will focus on plays used by real NFL teams, from passing plays to runs, and how the concepts within them can help to increase understanding of all set-pieces in football.

Screens

One of the most obvious links between the two sports is the use of screens or blocks in order to create space for a teammate. On the face of it, this is a fairly obvious and straightforward detail, however the various different types of screens used in American football offer ideas not often seen in football.

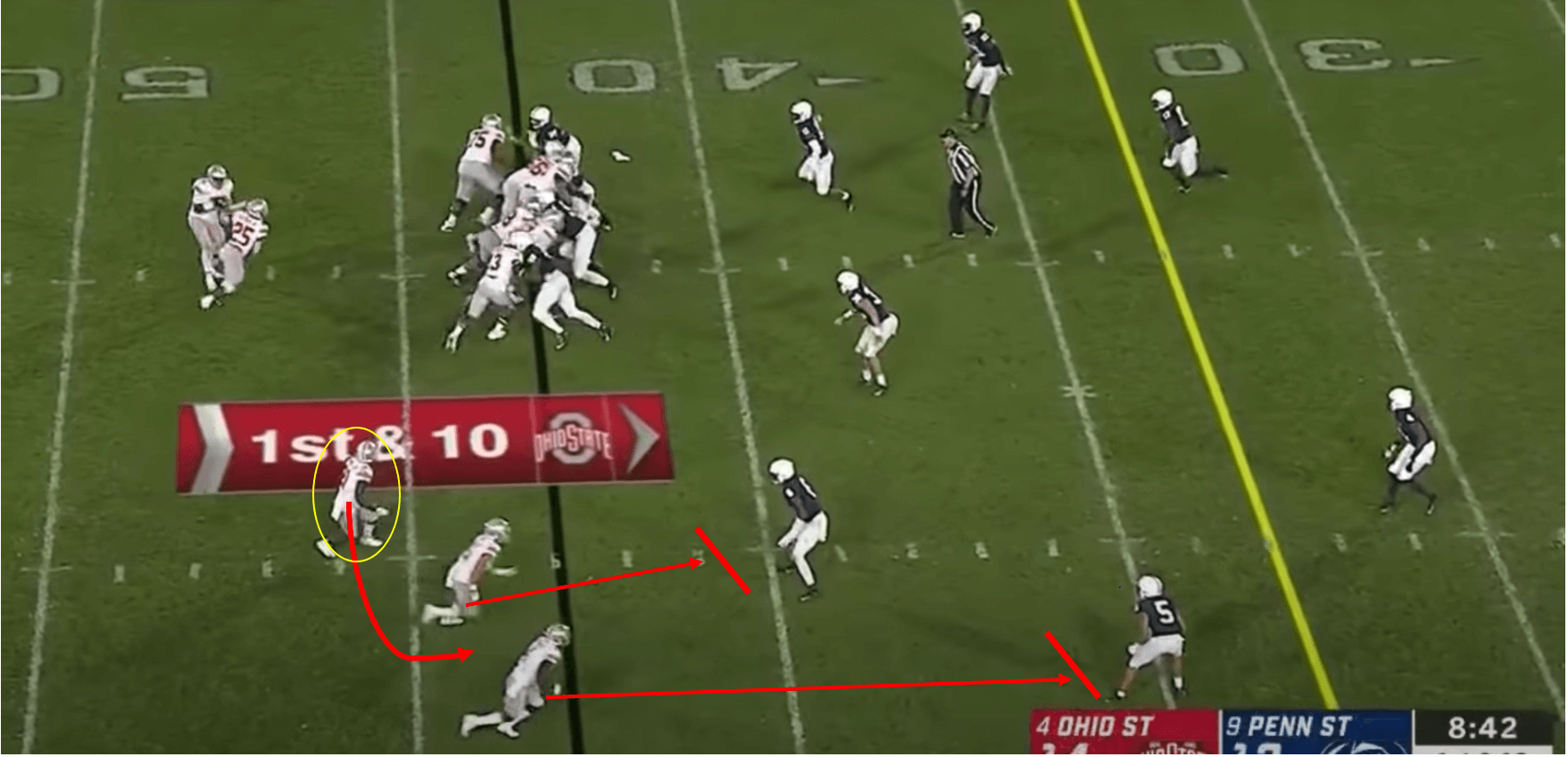

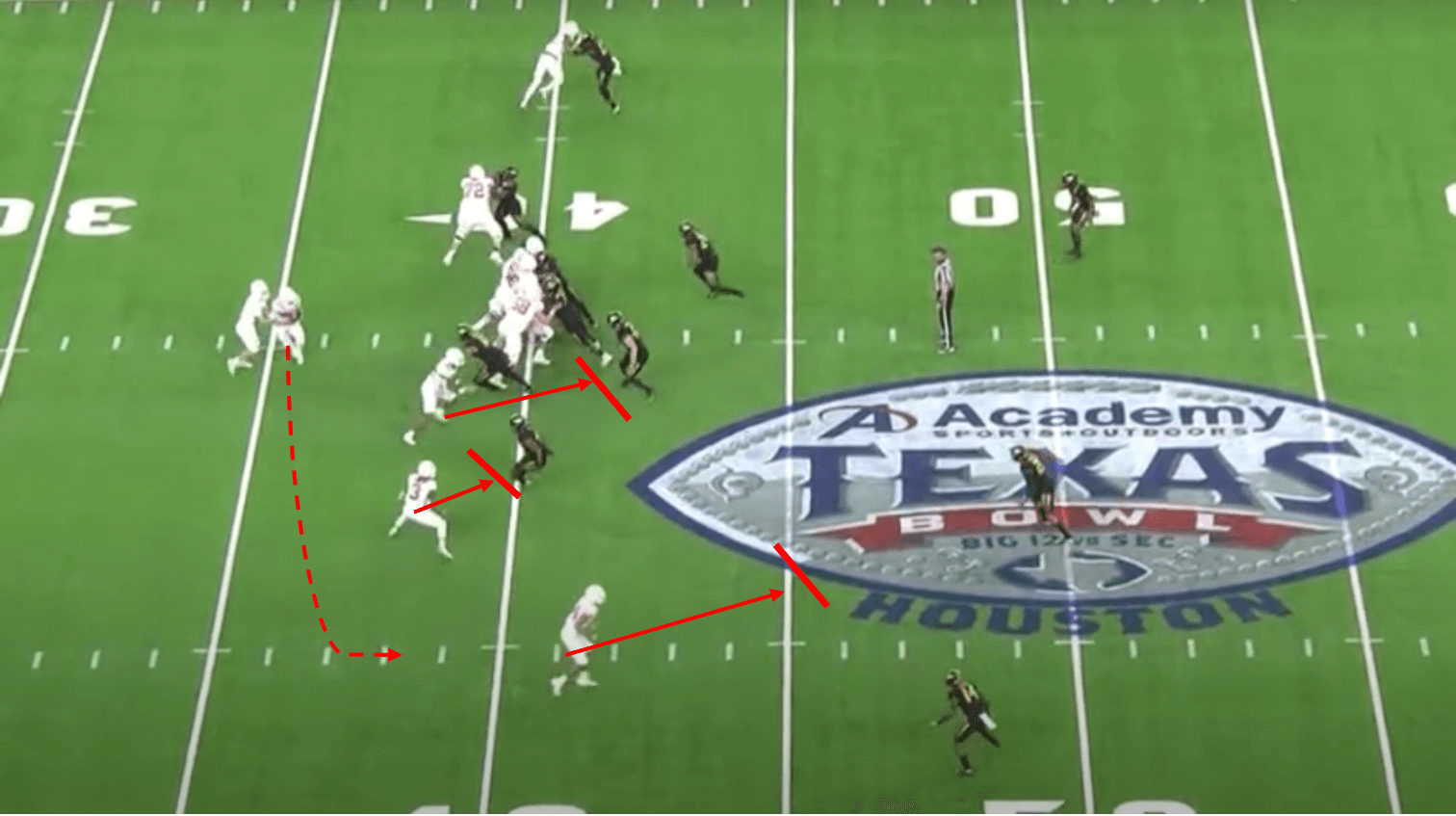

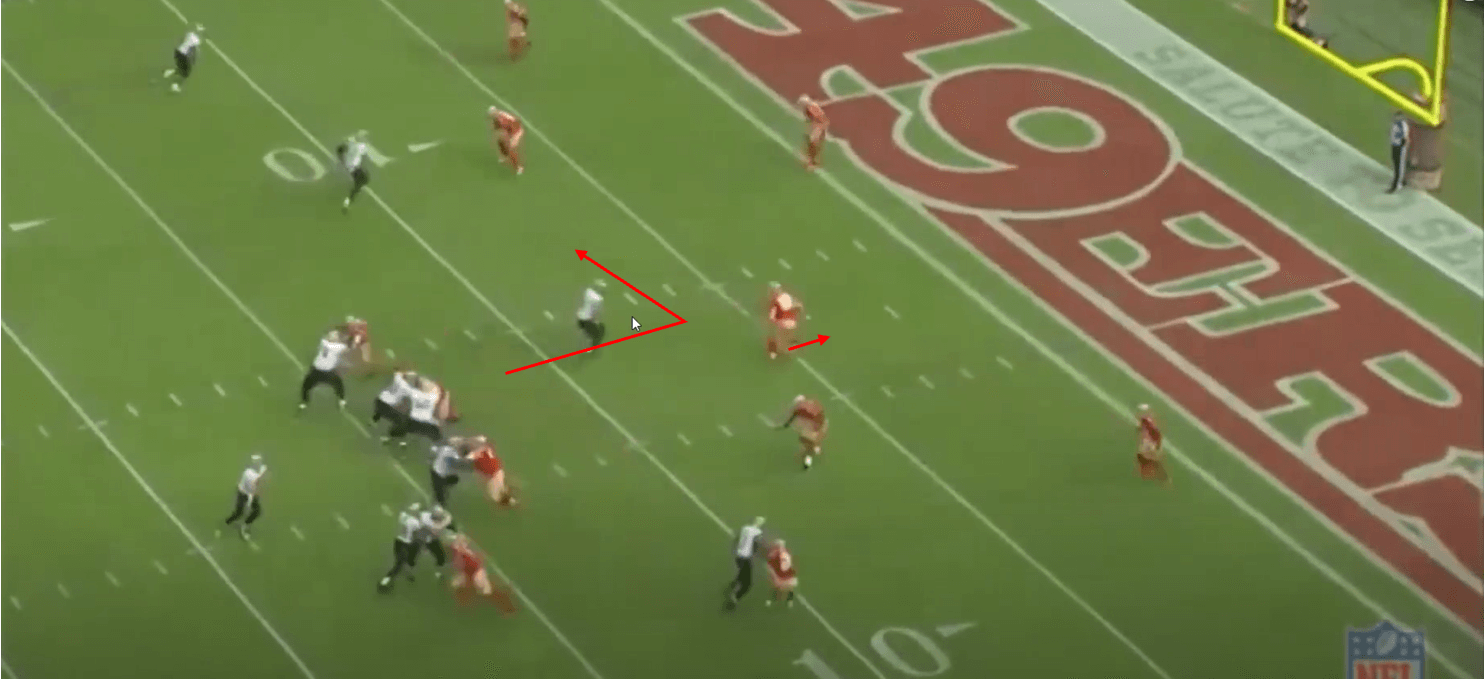

The main type of screen we will look at is the bubble screen, which involves a wide receiver starting closer to the quarterback. In this variation of a bubble screen here, the target player (wide receiver) starts the narrower of the three wide players, and makes an arced run to get around a teammate. His teammates either side of him then set blocks, and the movement to get in between gives time to catch the ball deeper before then running through an empty lane. The aim isn’t necessarily to always create a free player, but in this case it instead aims to create space to run into and progress the ball up the field.

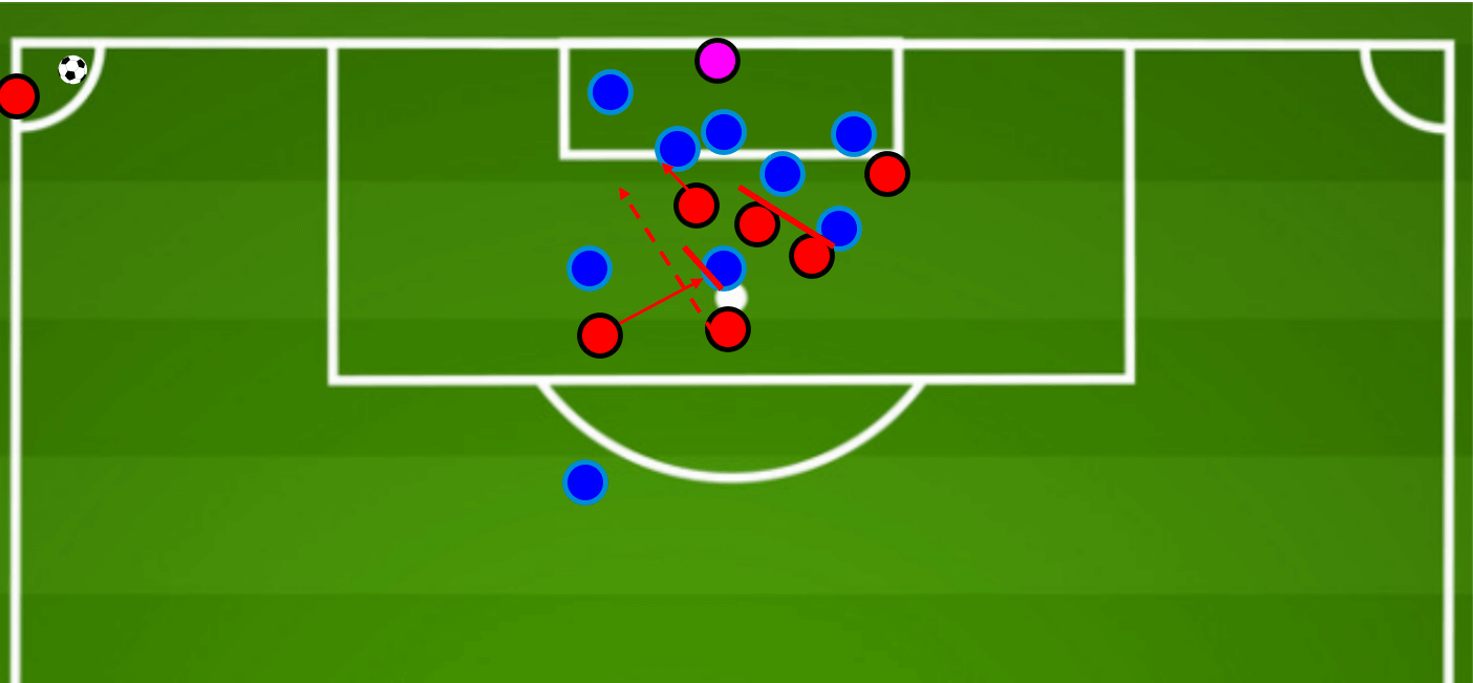

The play doesn’t have to involve three players, it can only involve one blocker and one receiver, and this type of screen can be transferred well into football in free-kicks. We can see an example of this below, with a free-kick in the final third taken with an outswinging delivery. The target area is the back post, and two players position themselves at the back post in a wide area, in the same way a wide receiver and running back would in the play above. The widest player looks to act as a blocker, while the second widest player acts as the target player. The widest player makes a diagonal run inwards that directly looks to block the target player’s marker, while that target player makes a curved run around the far side. The blocker is able to block the target player’s marker, but they are also able to take their original marker with them, meaning a free run is created for the target player.

This kind of screen relies heavily on timing, as the target player has to time when to start their run in order to receive in behind.

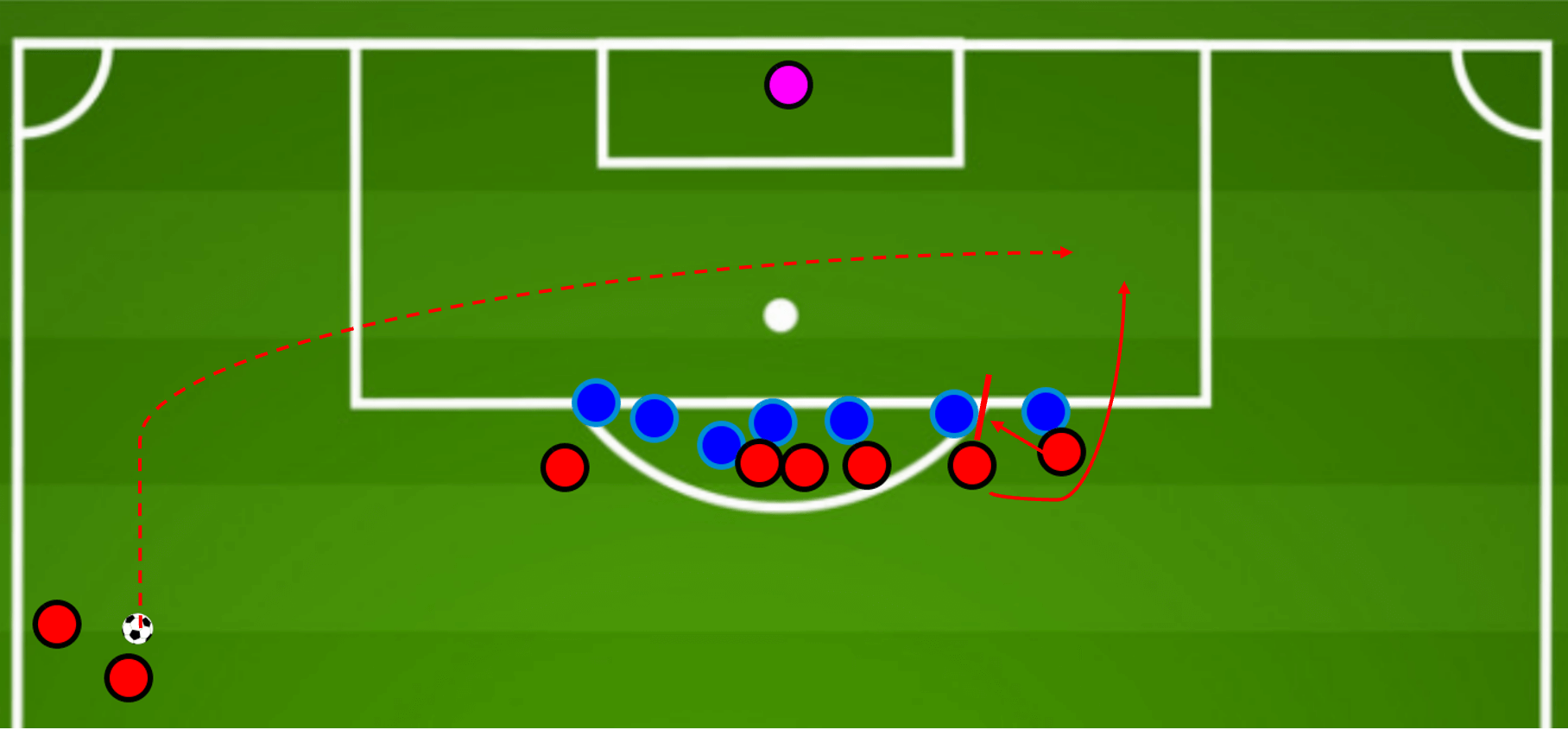

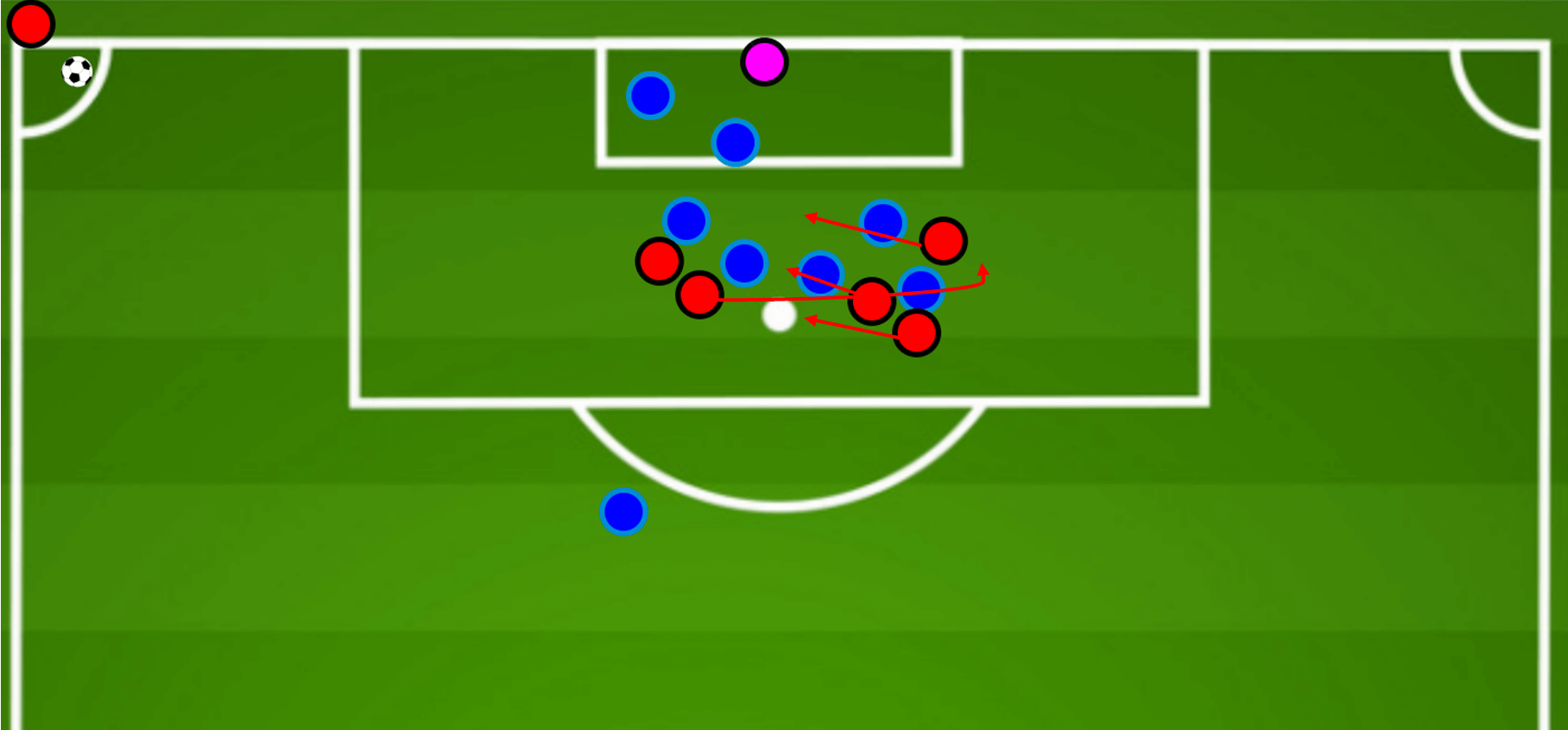

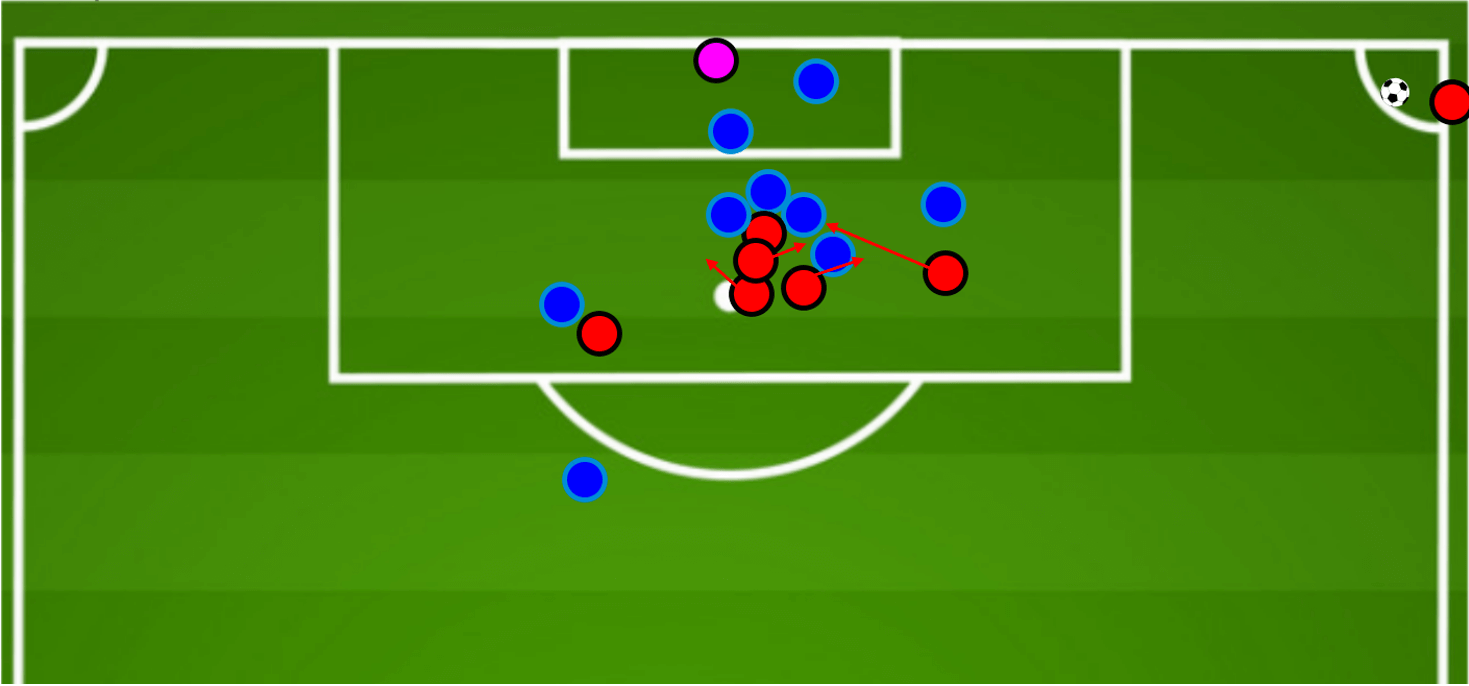

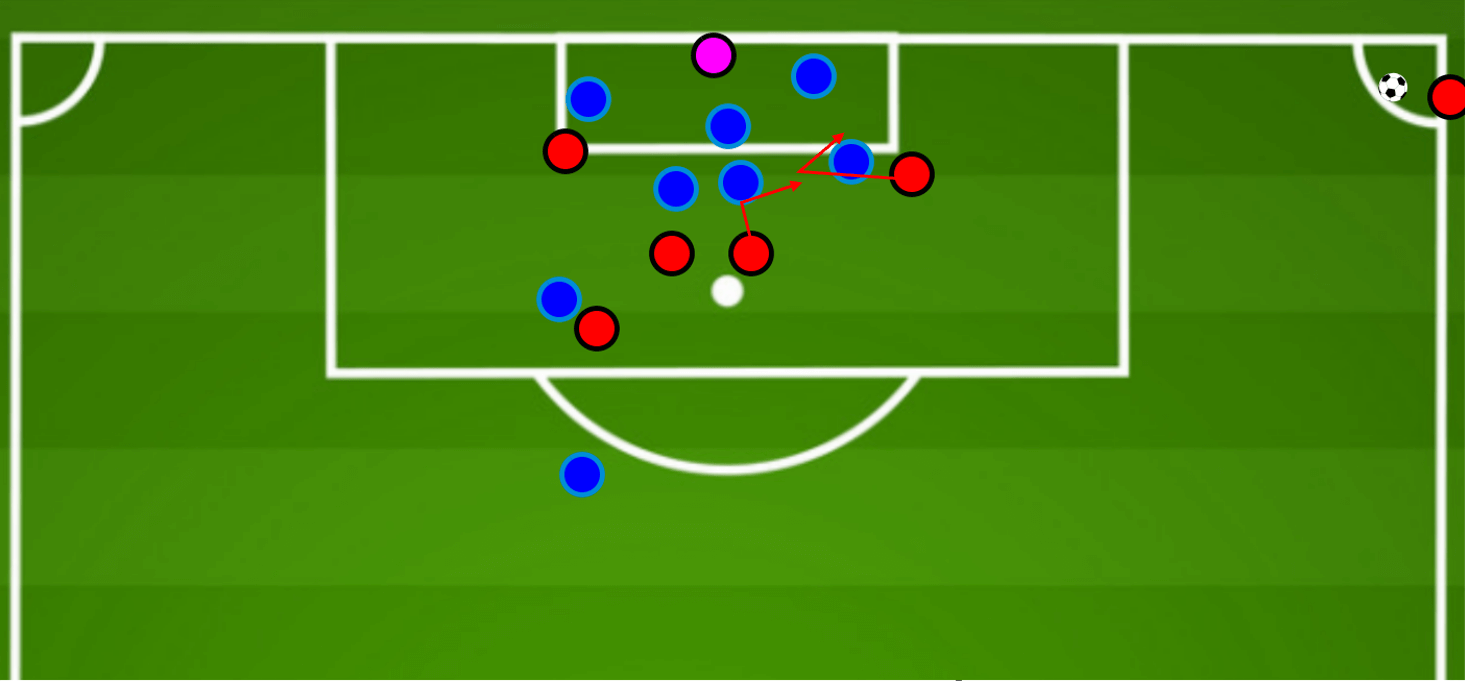

This kind of play could also be used for corners, and we can see an example of a routine I have designed below. Three players interact at the back post, with the two deeper players acting as screeners while the more central player acts as the target. The two screeners move in at a diagonal and look to take their markers in while blocking the target man’s marker. The target player moves around towards the back post, and because of the screens should have a free header at the back post.

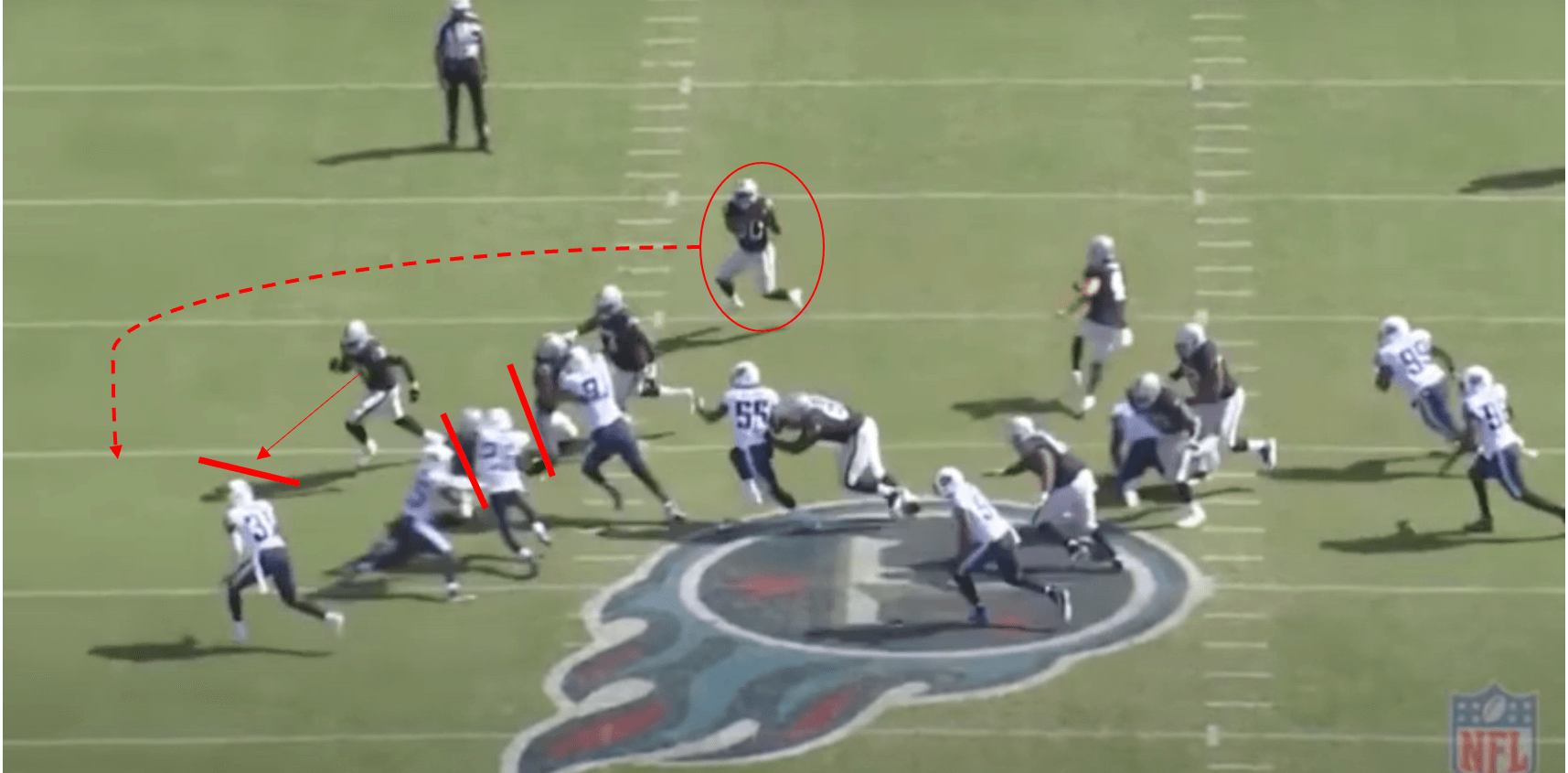

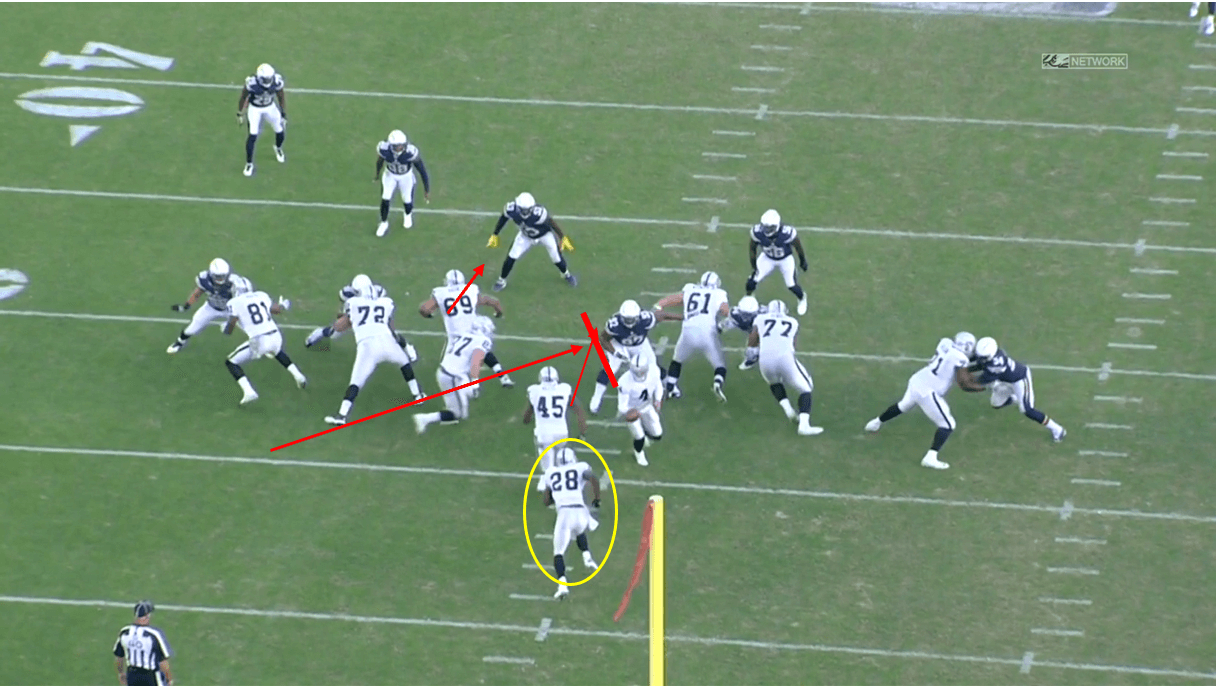

Another screen which can be utilised is the crack screen, which involves getting the ball to a deep running back early and setting blocks ahead of them to create space. We can see the play used here, with the running back being tossed the ball early. Players from wide areas move inwards on a diagonal and block defenders, and therefore restrict the defender’s access to the space behind them.

In this example, another player also runs ahead and drives at a defender before placing a block. As a result, the running back can catch the toss and run with the ball into open space. The concept between this screen and a bubble screen is somewhat similar, due to the wide receiver still moving inward, however a deeper player (running back) now acts as the target and his run is screened, whereas bubble screens are often used with passes.

Running plays

The concept of this play itself is similar to the idea of outside run plays, where a running back again takes the ball off the quarterback and looks to make a run around the outside of blockers. This creates a lot of separation between the running back and the defenders, but because it is a more lateral run, less vertical distance is covered.

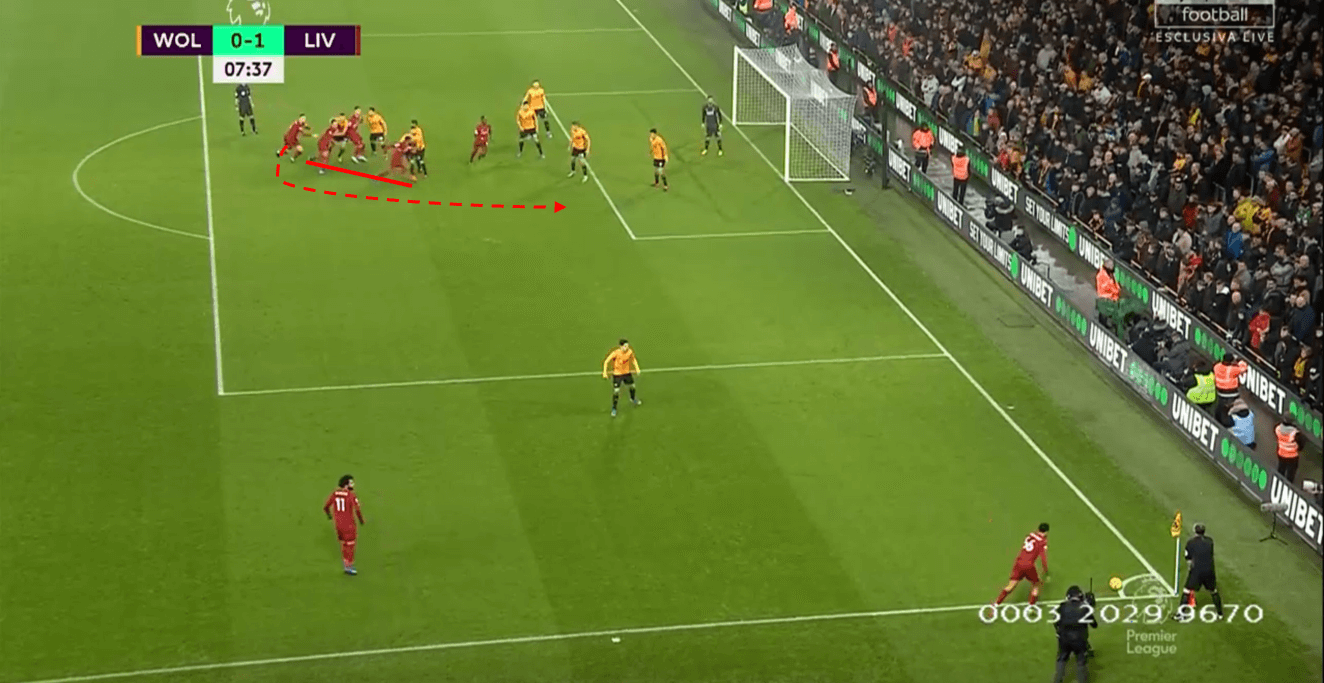

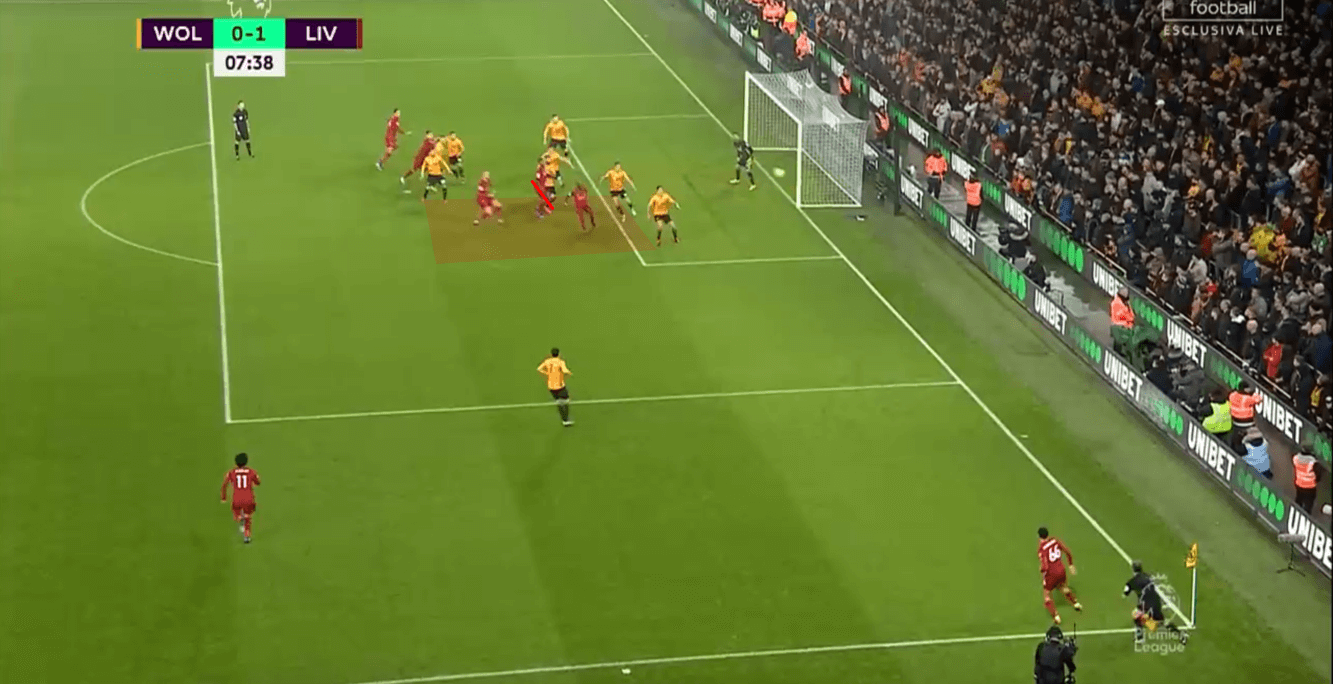

We can see an example of how this kind of screen or run can be replicated in football, with a Jordan Henderson goal from a corner for Liverpool. We see Henderson starts as the furthest player and also the deepest player, while other players stagger in front. Players in front stay on the far side of their markers, and so are able to apply blocks for Henderson, and so he has a free run around the outside.

The blocks on the Wolves markers allow for Henderson to have a free run, and players carry on their runs and end up applying blocks on zonal players. Trent Alexander Arnold delivers a pinpoint cross to meet Henderson’s run, and so he has a free header to score.

All of this is created by the idea of screening a deeper player to make an outside run.

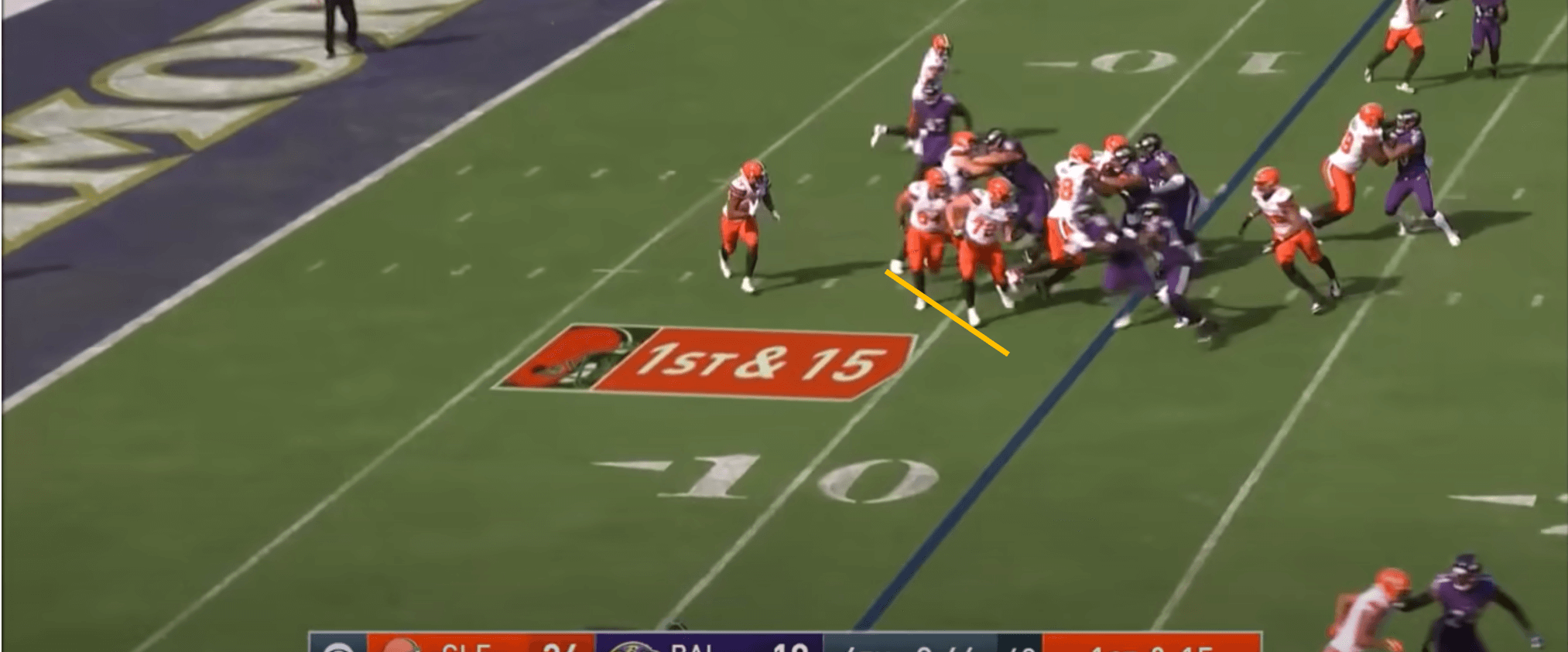

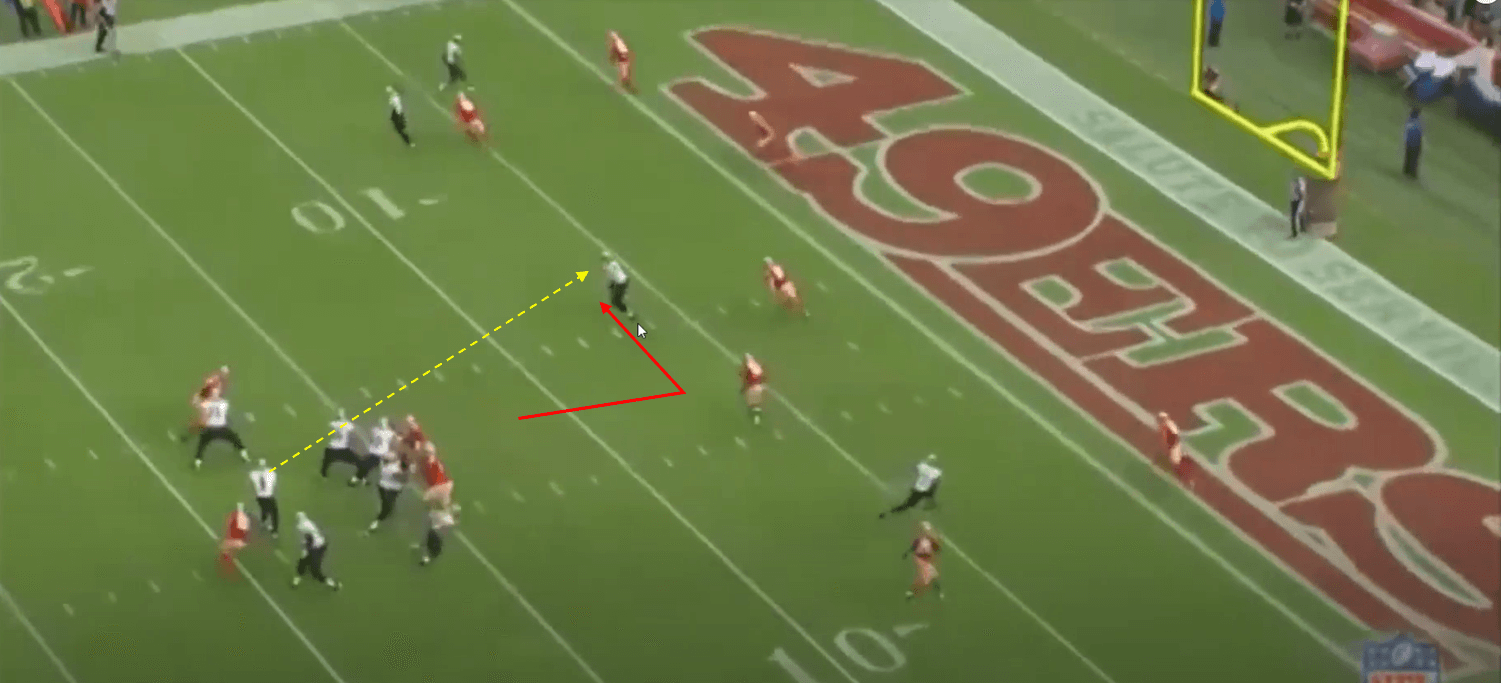

Runs are not just made on the outside though, and there are many different ways of running the ball. One effective way of finding space to run into is by cutting back inside on a run, and that is exactly what Nick Chubb does here.

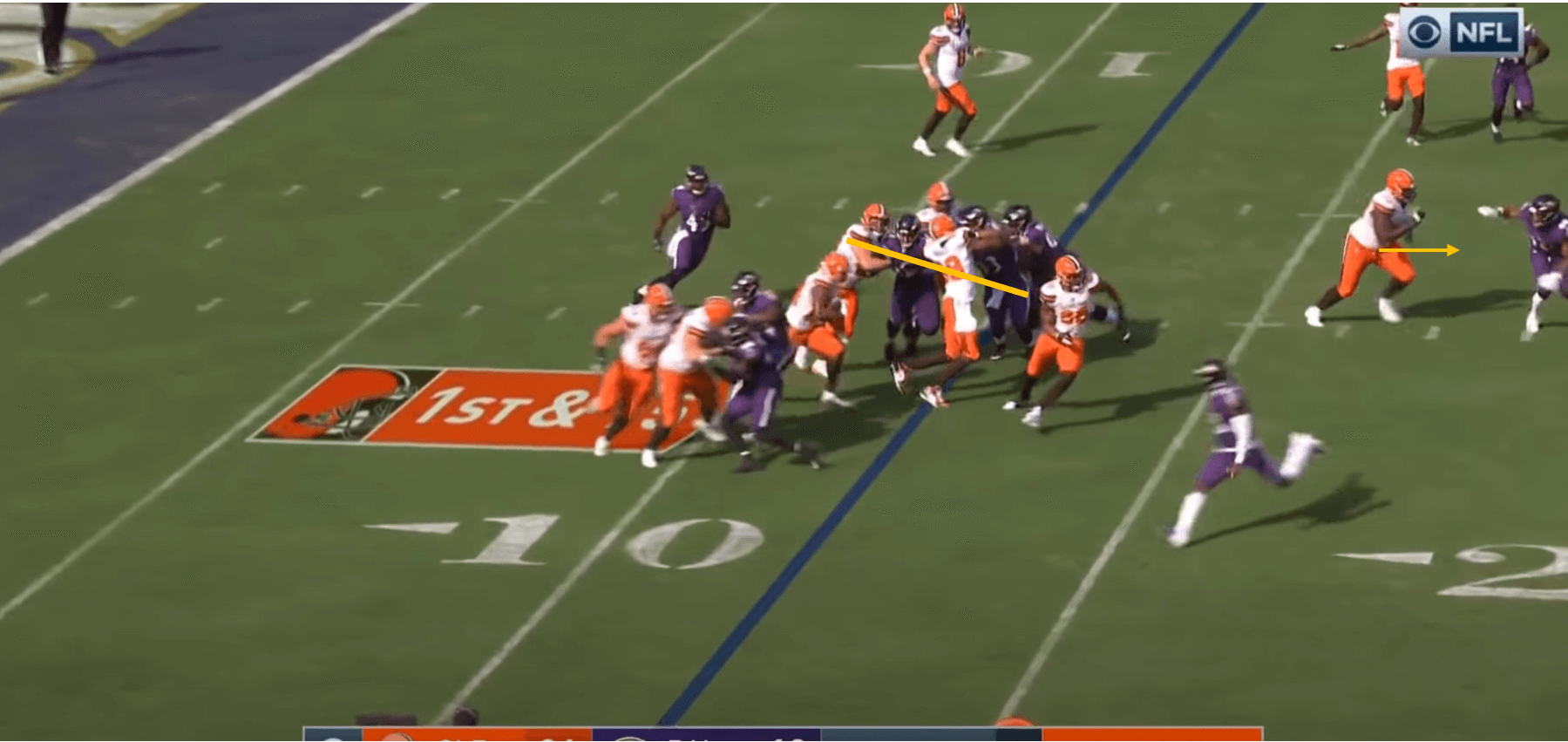

The play starts with a toss out to Chubb, and we can see the play very much resembles an outside run, with two players positioned to block the incoming Baltimore Ravens defenders. Because of the design of the play, the Ravens defence becomes focused on getting across to limit Chubb’s yards down the outside.

The two screeners on the outside actually act as a decoy here, and with screens placed on defenders recovering across, Chubb cuts back to make an inside run through an empty lane. We see the two wider Ravens defenders miss this cut and so Chubb runs past them. The Browns also have a screen placed higher up to prevent an early tackle, and Chubb ends up making an 88 yard touchdown run as a result of this cut.

Inspired by this idea of creating lanes to run into, routines such as the one below could be useful, with teammates running in opposite directions to create traffic. With optimal spacing and good organisation, you can create a clear running lane for the target player to move through, while their man markers cannot follow through this lane. As a bonus, if a defender runs into an attacker going in the opposite direction, a referee might take a closer look.

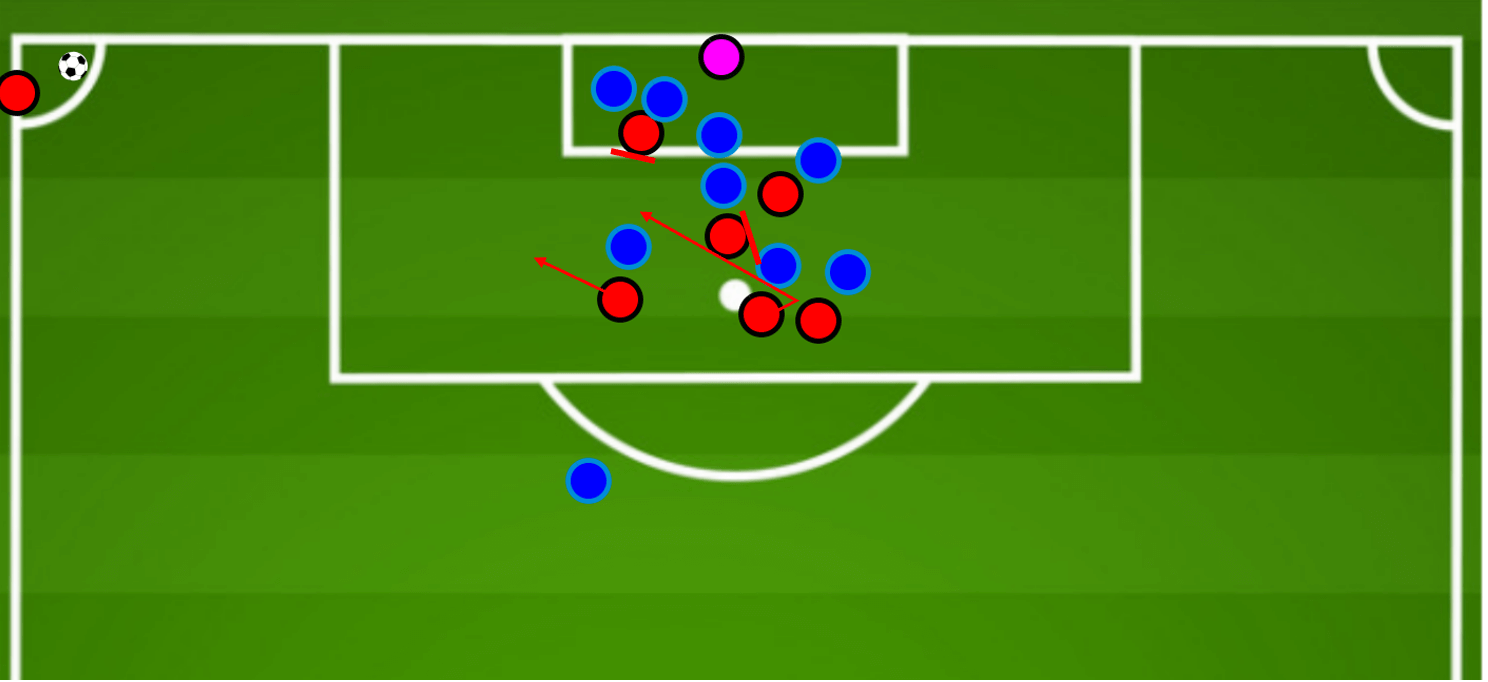

The kind of idea seen in the Nick Chubb example links to what I mentioned in part one regarding changing direction to dismark opponents, but the Browns have screens prepared to complement this change in direction. We can see an example of another potential routine which uses this concept, with the staggering of players helping to open lanes after a change in direction. The target player starts deep, and initially moves towards the back post before changing direction to dart towards the front post. A screen is ready to be applied by a player higher in the box, and so a free run in an open lane should be accessible.

A blocker is applied high up on the zonal marker to reduce the defender’s zonal coverage and reduce their chances of winning the header and clearing.

The two deepest players could start in a group to begin with to sell the back post (outside) run further.

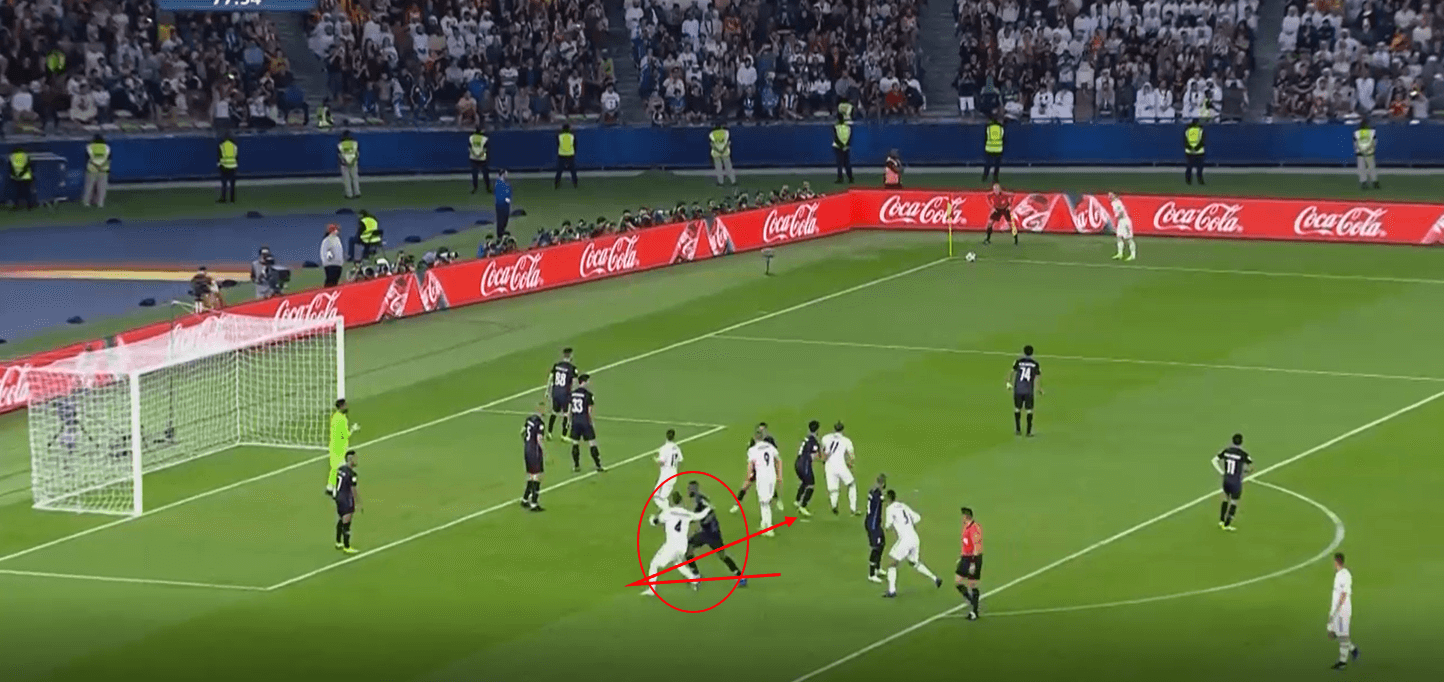

We can see Sergio Ramos scoring a goal for Real Madrid below by using this concept to his advantage. Ramos starts by moving towards the back post, before cutting quickly and shifting his weight well to change direction.

Notice how his weight is already shifted, while his marker’s full momentum is still running towards the back post. Ramos cuts into the direction of traffic.

Once Ramos’ marker reacts, Ramos is already on the far side of that block, and so his marker can’t make his way through the traffic to stay with his man. Ramos therefore gets a free header which he converts.

The Wham

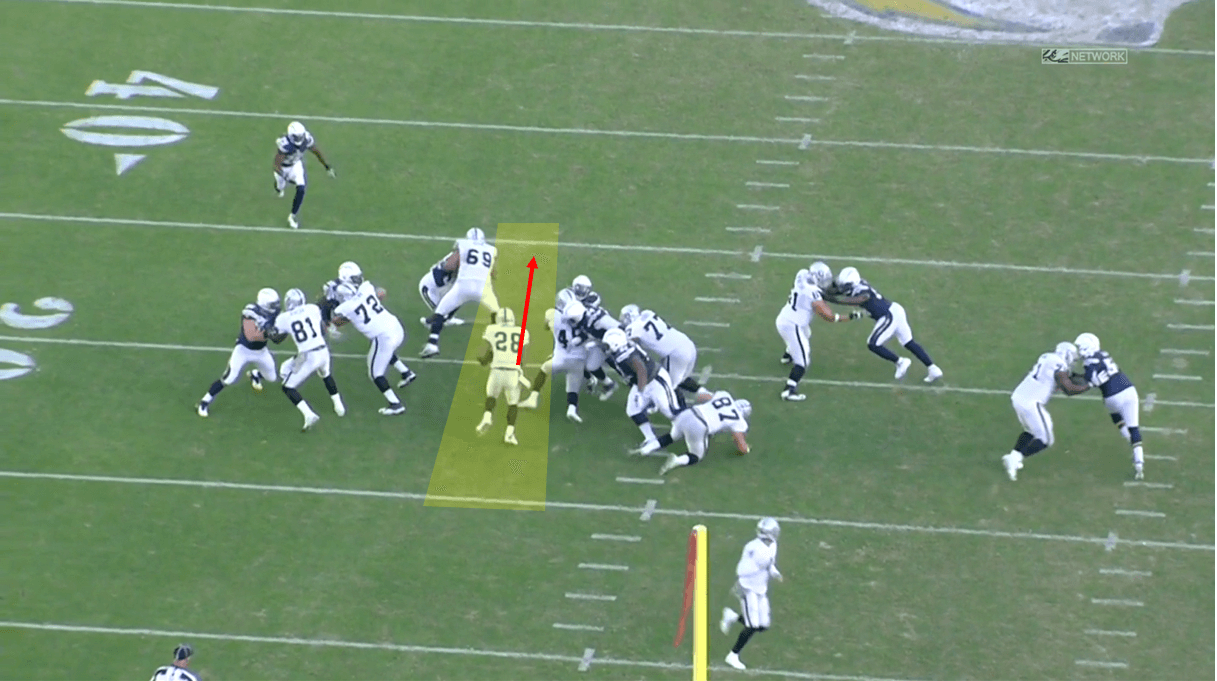

Another running play I think translates well into football is the ‘Wham’. The wham involves a player from the wing moving inwards and across the running lane in order to set a block on an opponent. We can see an example of the play in action below, where a player moves from wide and across the centre in order to block the nearest defender.

An attacker also lines up ahead of the target runner, in order to set a block in the same place. An offensive line man runs forward and sets a block higher.

The aim of this play is to really carve a hole or running lane in the opposition defence, and we can see below how the blocks set by those players allows for a clear running lane to open. The Philadelphia Eagles offense basically push and block defenders out of the way to create a lane for a player to run through.

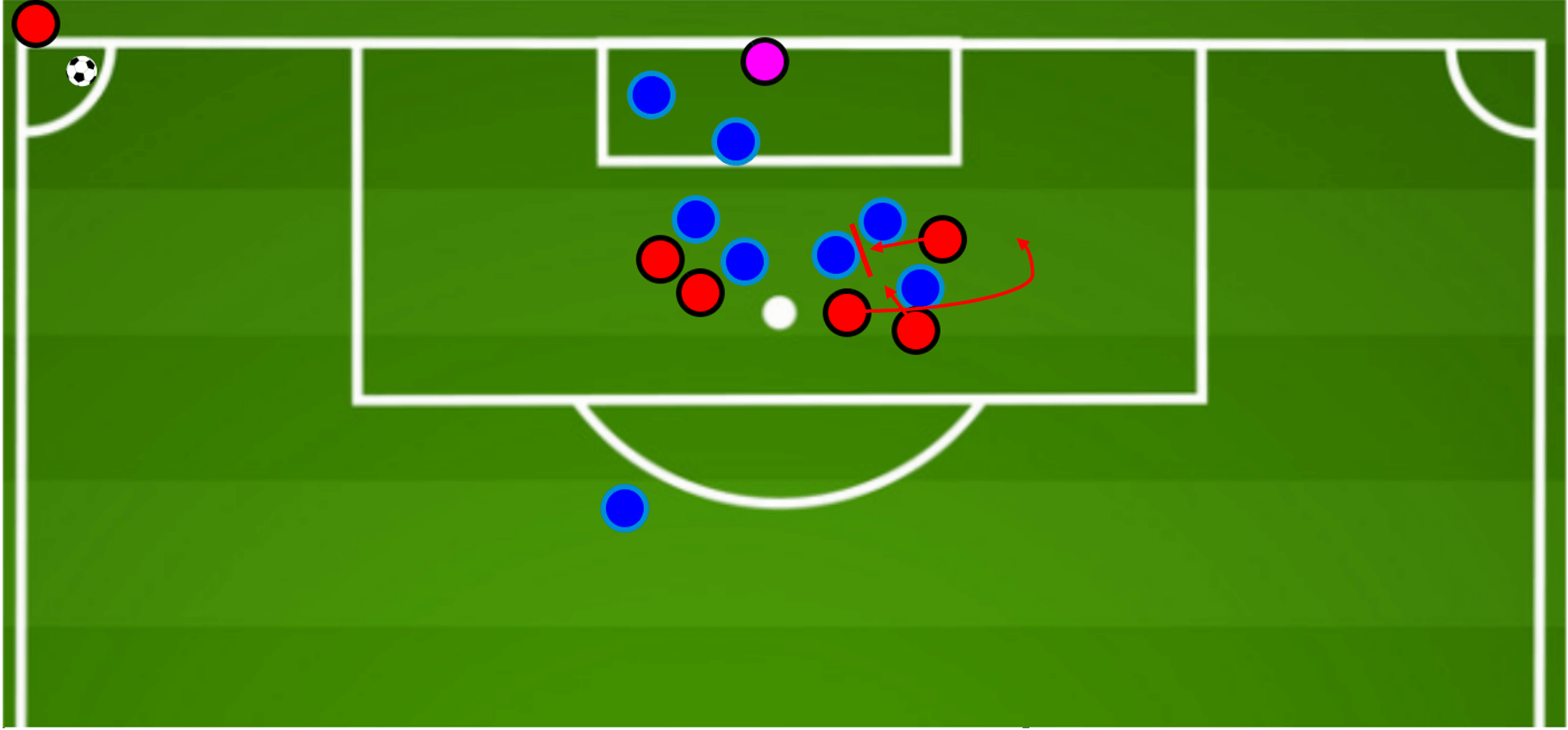

The wham could be used in football in a routine such as the one below. Two players start deep, with one player moving across into a central area to block the other’s marker. Other players start higher, and stay on the ball side of their opponents in order to set up a block. A player remains central and high, and looks to disrupt the zonal marker. The target player should have a free run from deep due to the block, and the zonal coverage of the defence should be disrupted.

The advantage of football in this case is that a man oriented defence will allow you to move players where you want, whereas an American football defence is set in it’s structure before the play is executed. As a result, it is easier to move players out of the way before the play in football.

One unique variation I have seen from some teams in Europe is to have one player act solely as a blocker, and so they simply run at opponents in order to allow teammates to create separation. We can see an example below where a player moves from the near post and just looks to run at a crowd of players and cause chaos. Defenders are especially likely to be hesitant to move and will slow down to avoid colliding, and if attackers know where the player is going to run into, they can move around them easily.

Stick play

The final play we will look at is the stick route, which is a common passing play where receivers will make vertical runs before cutting off at a horizontal angle to receive the throw. We can see the play illustrated below, with a player making a vertical run initially at a defender. This aims to put the defender on their heels and force them to think about moving back, with some defenders biting on this and shifting their weight backwards. Once this is achieved, the player ‘sticks’ and explodes off their lead foot to make a lateral run. This explosion and shift of weight off the front foot is vital to achieve separation.

As a result of the stick, separation is created and the receiver has his back to his initial defender, and if needed can shield the ball while catching to prevent an interception. The quarterback therefore has a pretty routine throw to the receiver for a catch. This play isn’t a long one that makes up lots of yards, but it is an efficient way of progressing the ball forward when needed.

Below we can see a few ideas of how this can be implemented in football. We can see two stick plays in one in this example, which is not something I would do in the same zone, but for the purposes of this article I am showing how you could use this concept. The first stick that could be used is a much more conventional method, where a player from deep (just past penalty spot) makes a vertical run at their marker, before then exploding off their left foot towards the near post. The aim remains the same: Put the defender on their heels. If done effectively, and if the delivery is good, separation should be created at the near post and a good quality header should come out of it.

The second example of a stick in this play is less conventional, as the player starts at the near post and actually has their back to the corner taker initially. This player feints a back post run initially, and so runs vertically and tries to take their marker with them. Once their marker’s momentum is taking them towards the back post, the player sticks their run and shifts back towards the near post. Again, separation should be created if done effectively and if the defender is very man-oriented.

Conclusion

There are multiple areas within American football which transfer well into set-pieces in football, and this piece has sought to identify some plays which could benefit our understanding. Many different plays also transfer well and there are certainly a few I probably don’t know about yet, but I simply arranged this piece in terms of plays I’m familiar with that could be useful. I have included another comparison in my set-piece analysis for this week’s magazine, where I look at the jet sweep and how it could be used.

An interesting aspect of plays in the NFL is that any play can also be faked, and so if teams read the offense early then a play can be faked to gain an advantage. In football, this is more difficult, as most defensive teams don’t tend to have a predetermined view of what plays an offense runs. It is not however impossible to fake a play, as if players momentarily commit to one side, in theory a good offensive team could adjust and gain an advantage. As we see more set-piece consultants and coaches entering football, will we reach a point where teams have a playbook and are able to fake plays to outwit one another? Teams certainly already have trends and tactics in their running or corner deliveries which you could classify maybe as a playbook, but I expect these kinds of ideas to increase over the coming years.

Finally, just as a shameless plug to myself, if you are interested in your team using these concepts and others, I offer my services as a set-piece consultant. I currently work with an FA Women’s Super League team and have consulted with teams all around Europe, so please get in touch if this is something you are interested in.

Comments