Often when you hear someone speak about direct vs possession football, you’ll find “direct” used in a pejorative manner.

Whereas possession is associated with structure, control, intricate movements and purposeful attacking, direct is often derided as a less aesthetically pleasing form of football. It’s simple, less intricate and more easily replicated. There’s also the reduction of direct play to a hit and hope Route 1 philosophy. Any old squad can have success with the direct approach whereas possession is the burden of talent.

That’s where we’ll make our first distinction. Rather than distinguishing direct from possession, we’re reframing the concept to think of it as direct possession vs indirect possession.

This tactical analysis is all about the benefits of direct ball progression and the many forms it takes. We will not only look at the various types of direct possession but also how teams implement the philosophy in concrete scenarios.

Let’s start with a necessary distinction, then progress to other forms of direct possession and finish with how defensive structures can create opportunities for direct attacking.

Route 1 vs Direct Possession

The most widely known form of direct possession is certainly the old school Route 1, so we’ll start there and examine how this simplified hit and hope tactic (while successful at times) differs from more developed forms of direct possession.

While there is a hit and hope element to Route 1 football, teams that utilise this style significantly increase their chances of success latching on to the long ball if they can get numbers high up the pitch, typically with a speed advantage over the opposition. Our example of the approach comes from a West Ham vs Leicester City match. Looking at West Ham, in particular, the club ranked 85th out of the UEFA top five leagues (98 teams) in possession, averaging 42.9 per game. However, they ranked 28th in goals per 90 minutes, averaging 1.52 with the 20th rated total xG for the 2020/21 campaign.

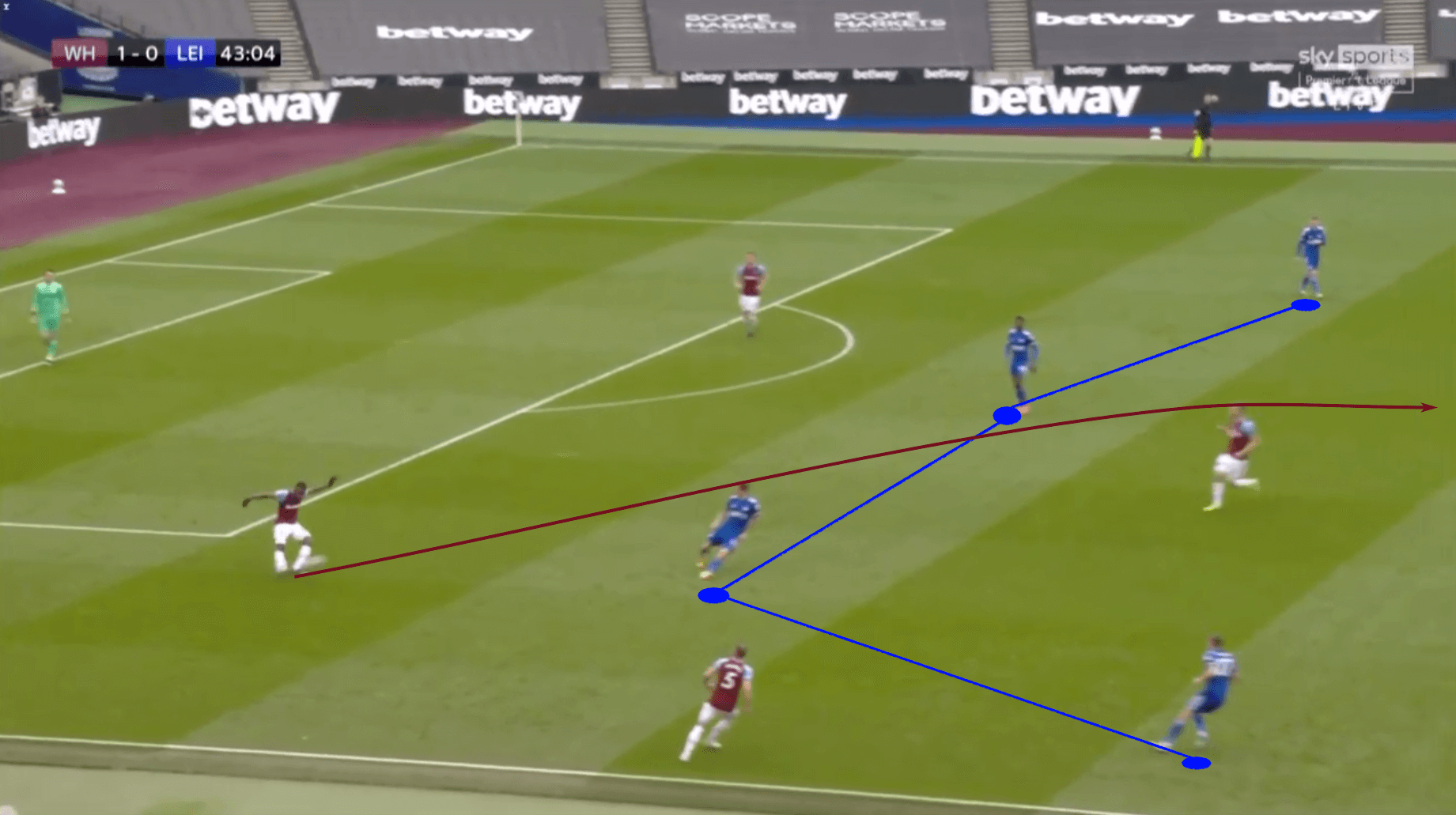

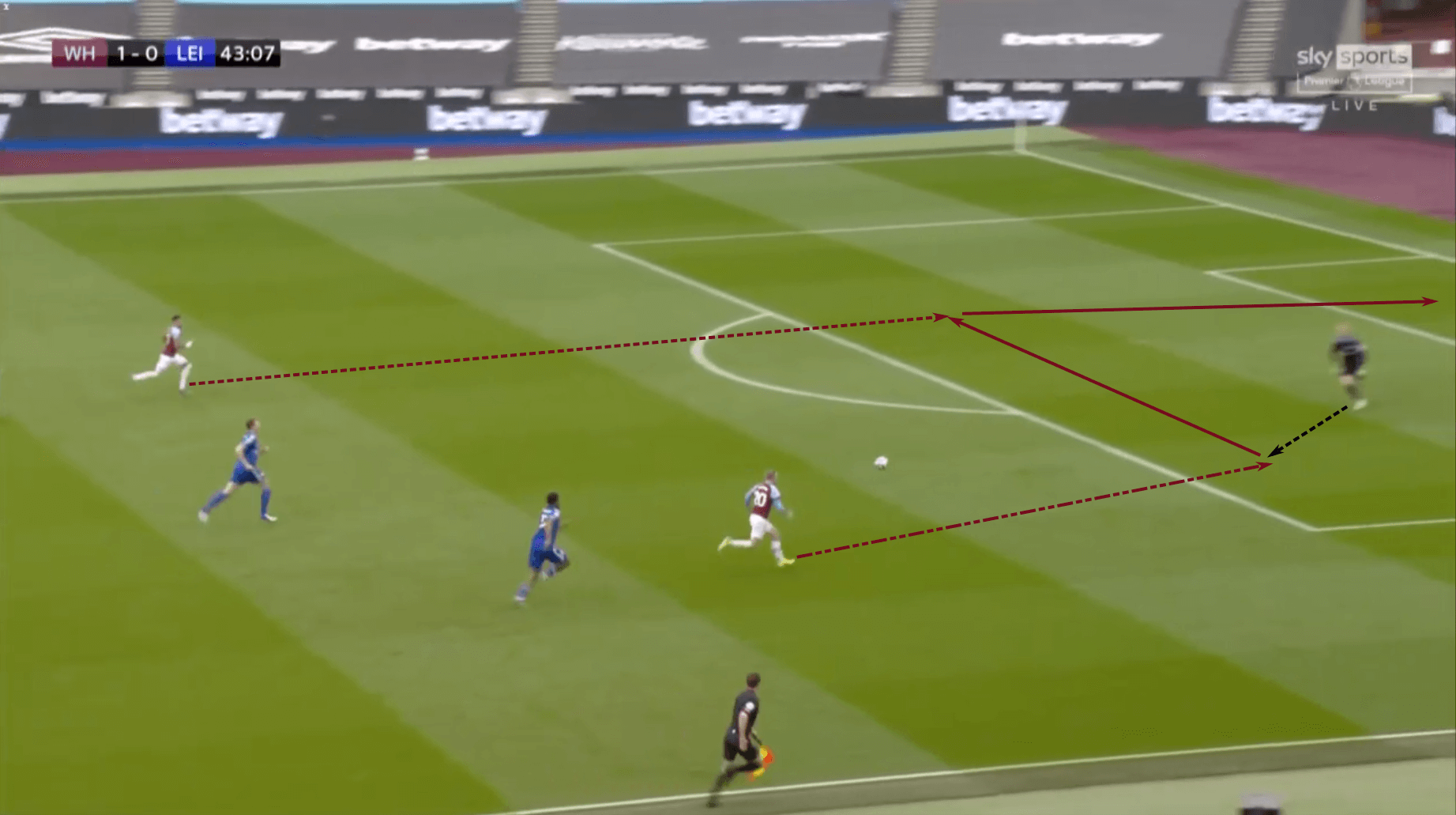

In this example, Leicester has committed numbers high up the pitch to press the West Ham build-out. Leicester’s backline is high up the pitch, leaving space for the West Ham forwards to run into. Issa Diop recognises the vulnerability and plays the ball over the top.

Jarrod Bowen latches on to the long pass, beating Kasper Schmeichel to the ball. Jesse Lingard makes a supporting run in the central channel, resulting in a simple square pass and finish to give the home side a 2-0 lead.

Route 1 directs the attack along the most efficient line. The attack is vertical, travelling along the shortest path, from A to B. It’s simple, plays the odds and allows teams to prioritise low block defending. It’s a risk-averse approach to the game that gambles on a mistake from the opposition that leads to goal-scoring opportunities.

That’s the prototypical view of direct attacking. But how does that differ from direct possession?

By direct possession, I mean a structured, controlled attacking brand of football that seeks to break lines and attack space with as few passes and as little time as possible. Not necessarily point A to point B, direct possession is not reliant on hopeful balls over the top, but, rather, is designed to capitalise on spatial and numeric vulnerabilities in the opposition through tightly connected networks, often with passes played on the ground.

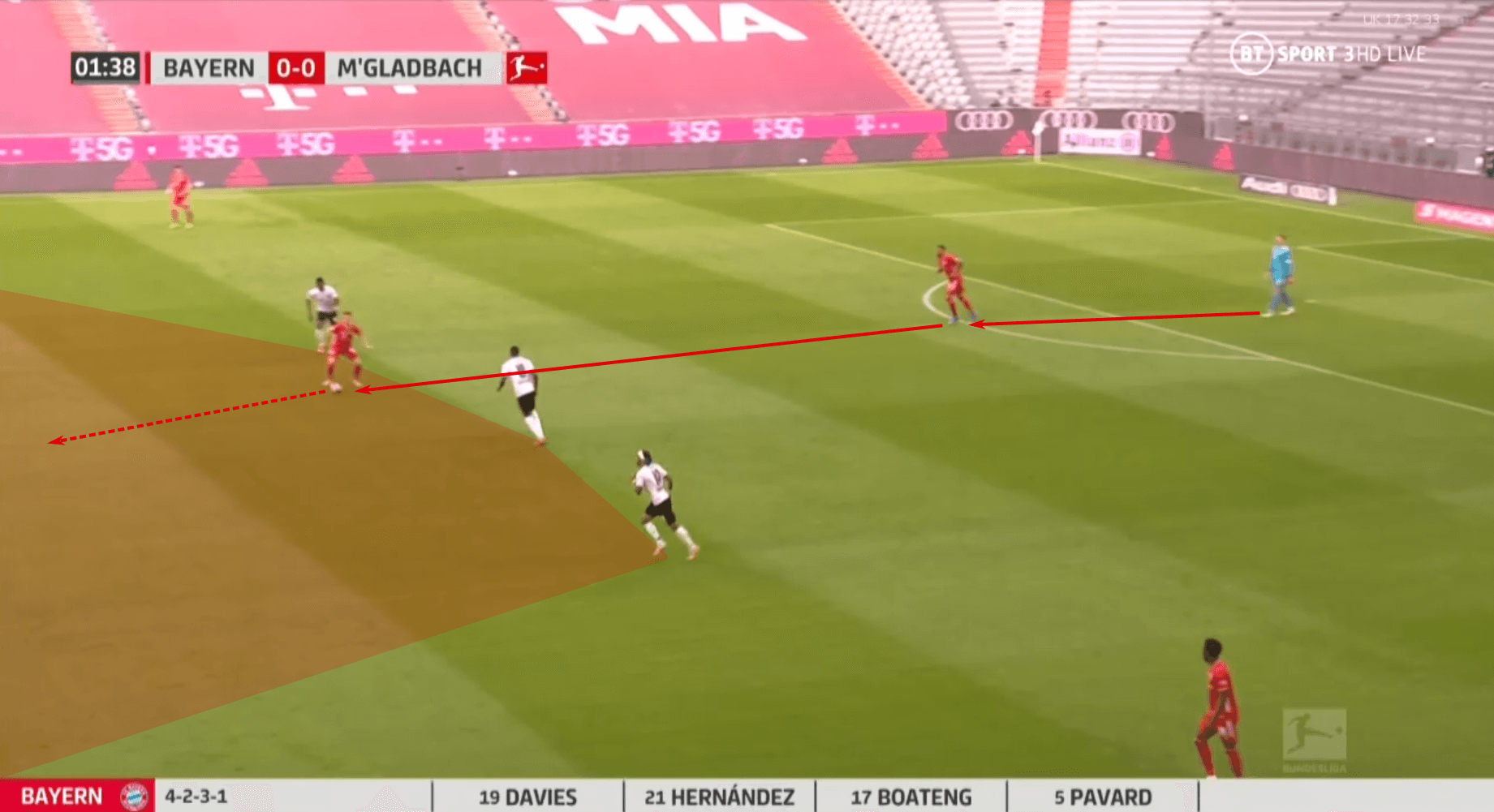

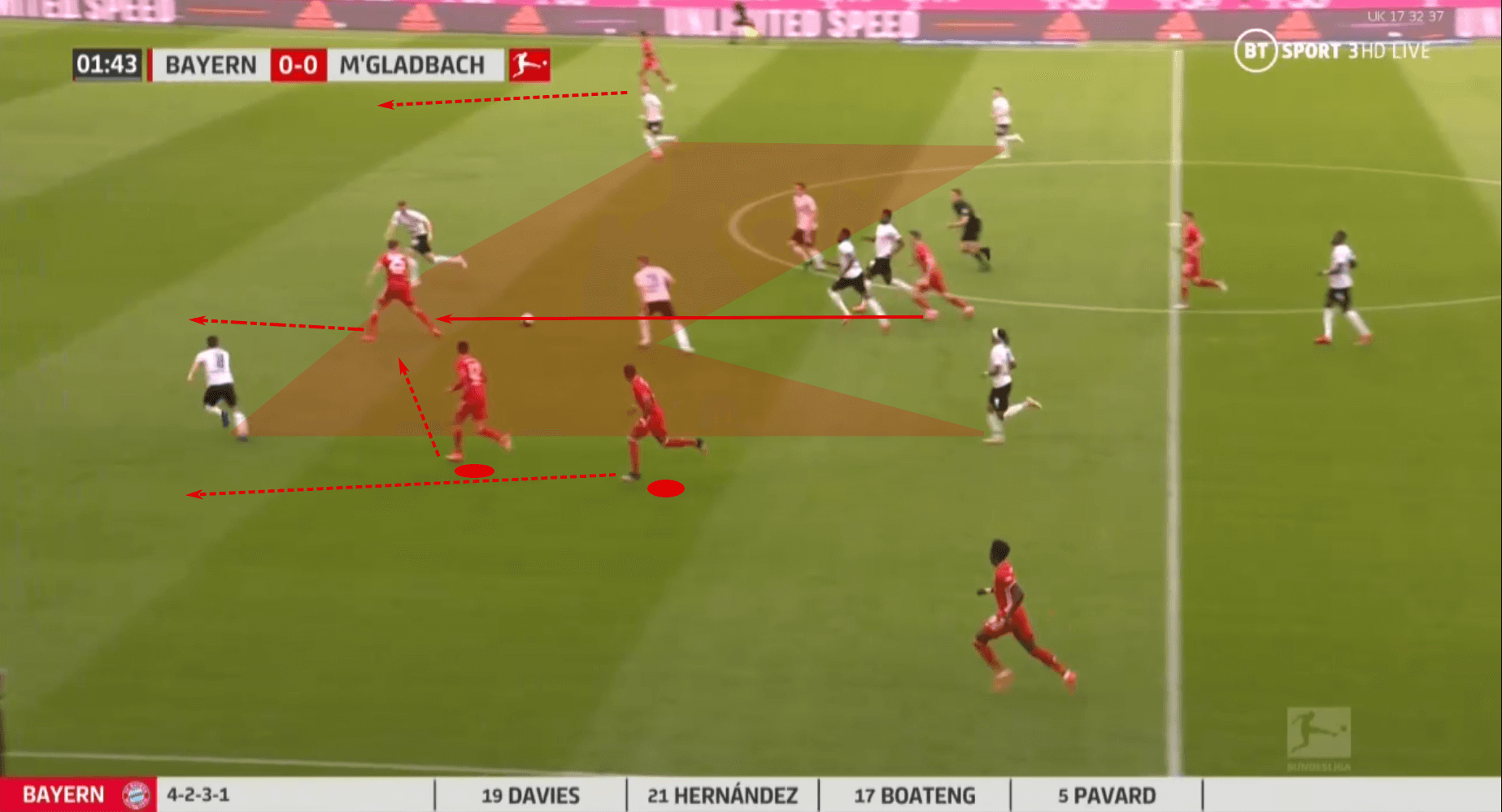

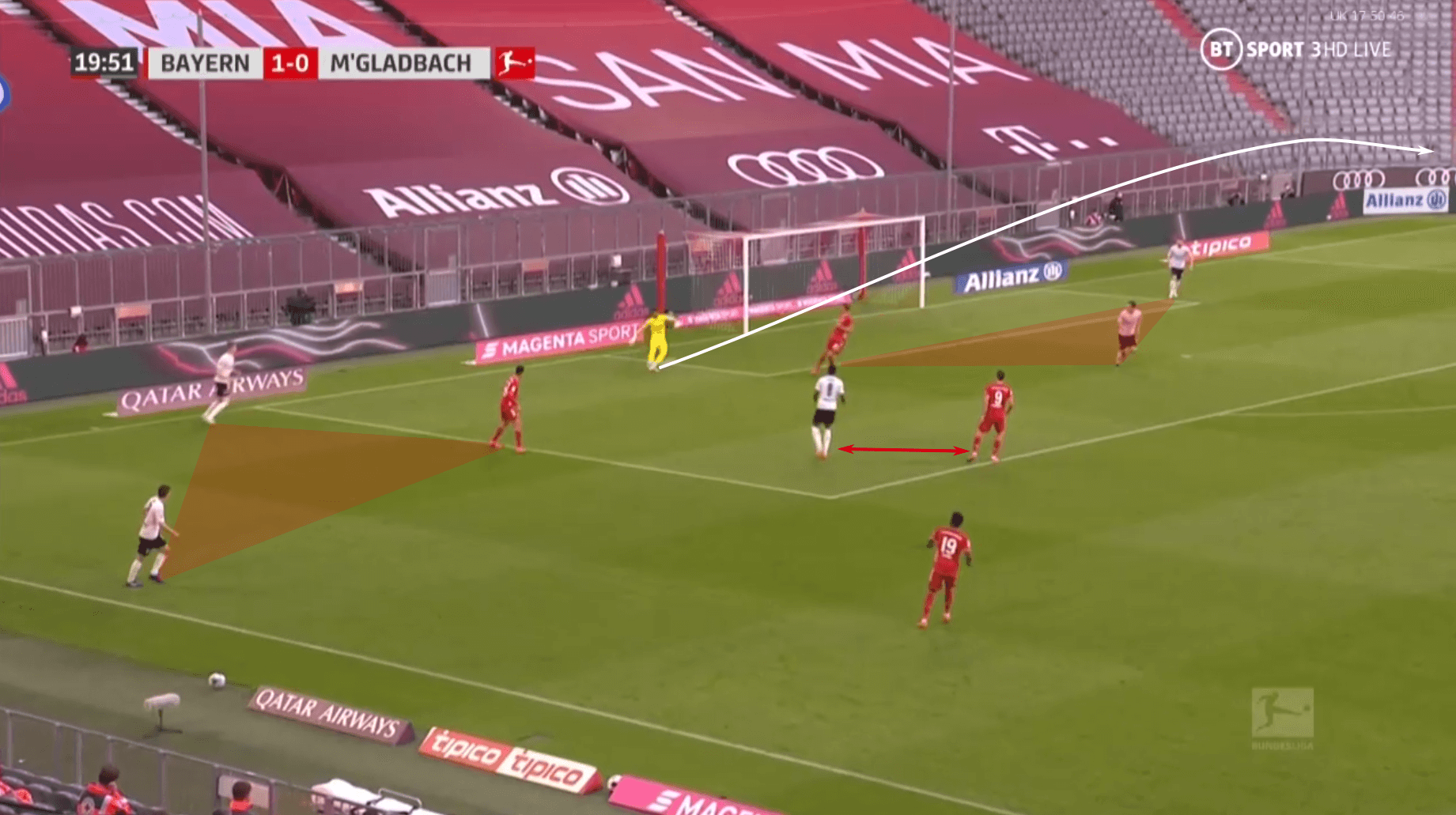

To visualise an excellently executed attack through direct possession, we turned to Bayern Munich. After Borussia Mönchengladbach’s long pass was claimed by Manuel Neuer, the sweeper-keeper played a simple short pass to his teammate, Jerome Boateng. The centre-back found Joshua Kimmich, who positioned himself beyond the first line of Borussia Mönchengladbach’s press, allowing him to touch the ball upfield on the half-turn and attack space through the dribble.

As he nears midfield, Kimmich attacks the second line of the press while the first line continues its pursuit. With the first line unable to catch Kimmich, the second line steps up with Denis Zakaria stepping into a first defender role.

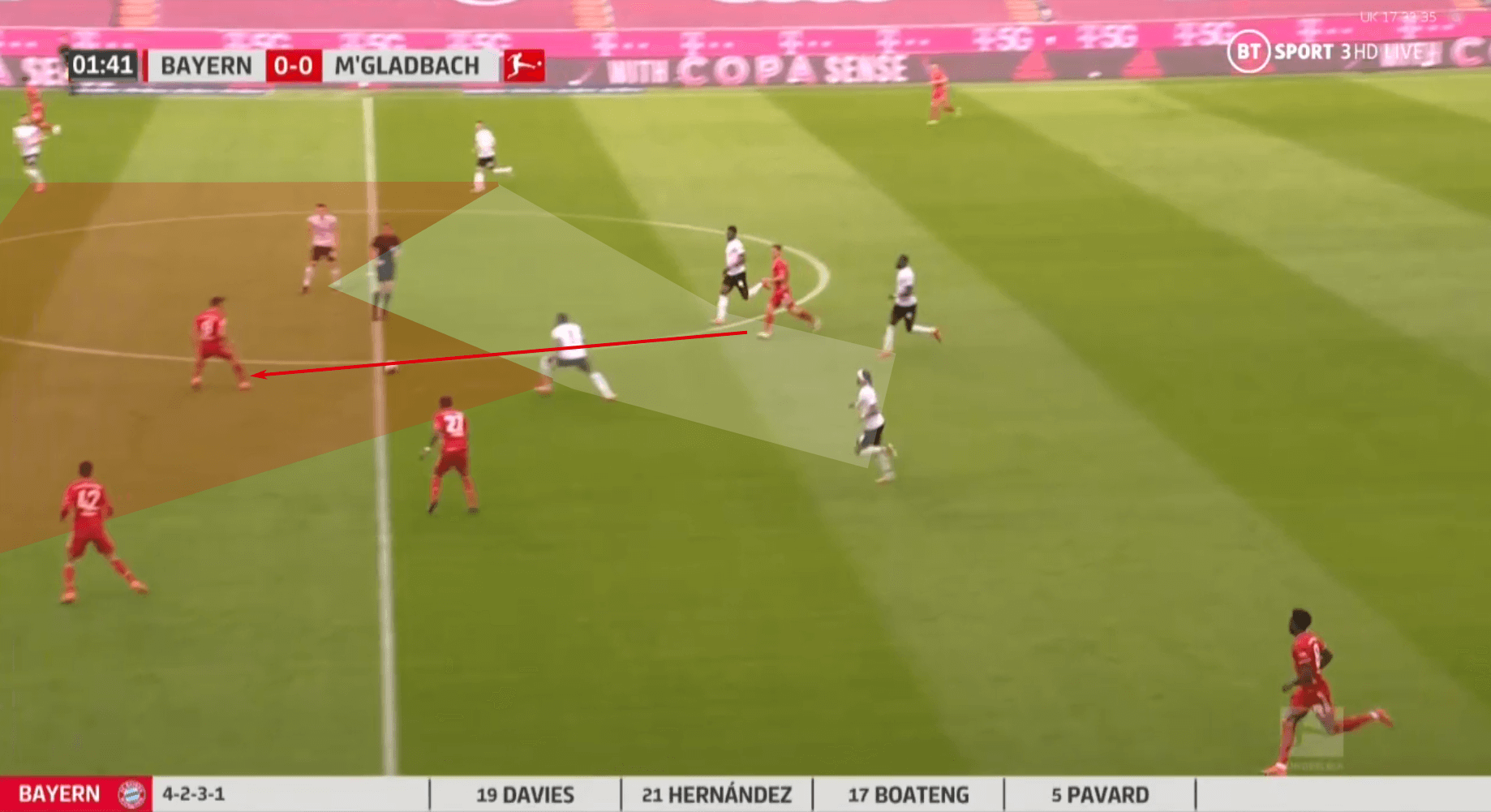

But the second line is essentially caught in no man’s land and pinned to the spot. A simple outlet pass from Kimmich to Robert Lewandowski breaks the second line. Notice that in each image, Bayern Munich players have taken up positions between the lines, allowing them to play through the press, take their first touch on the half-turn and attack space through the dribble.

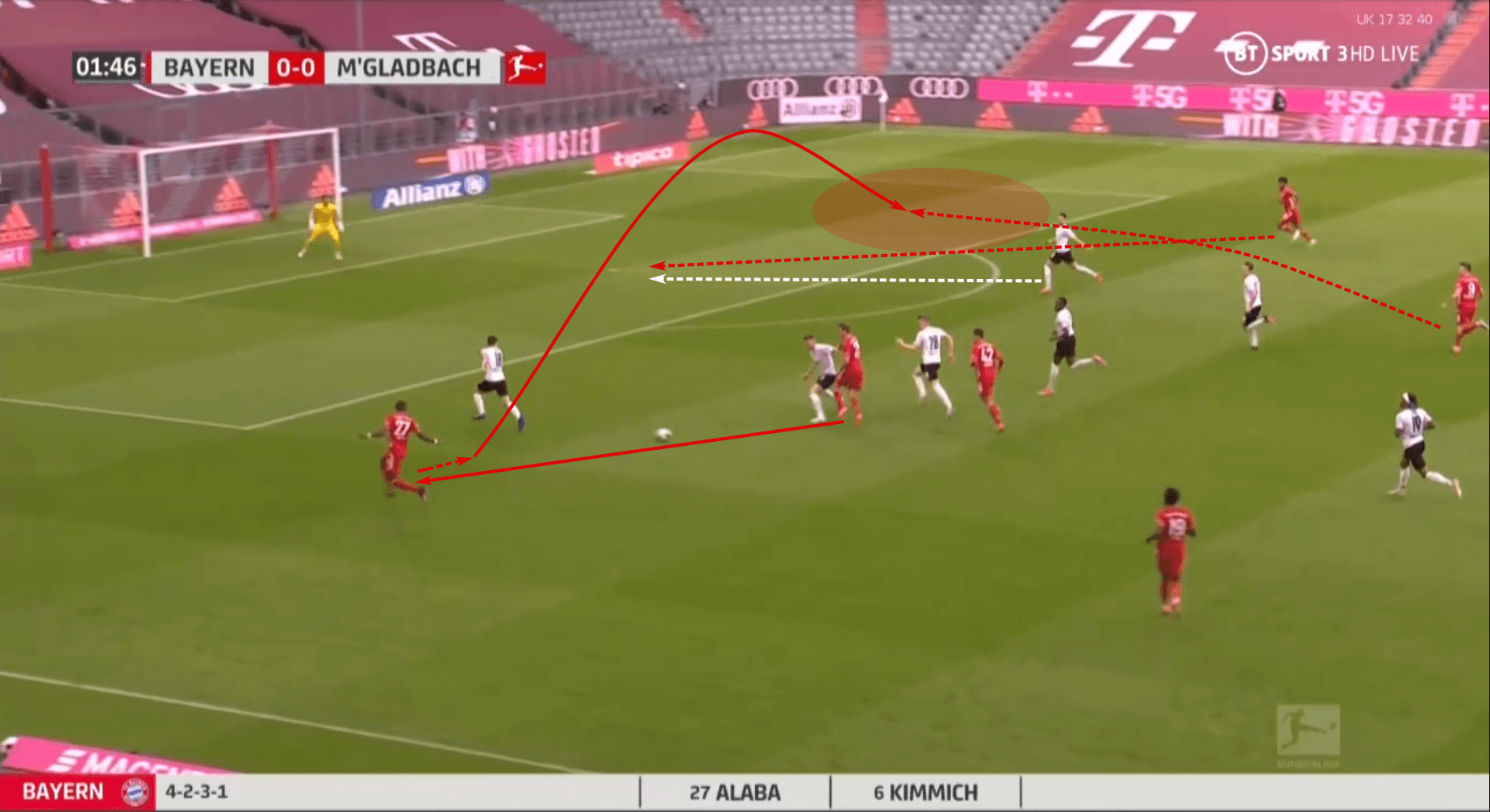

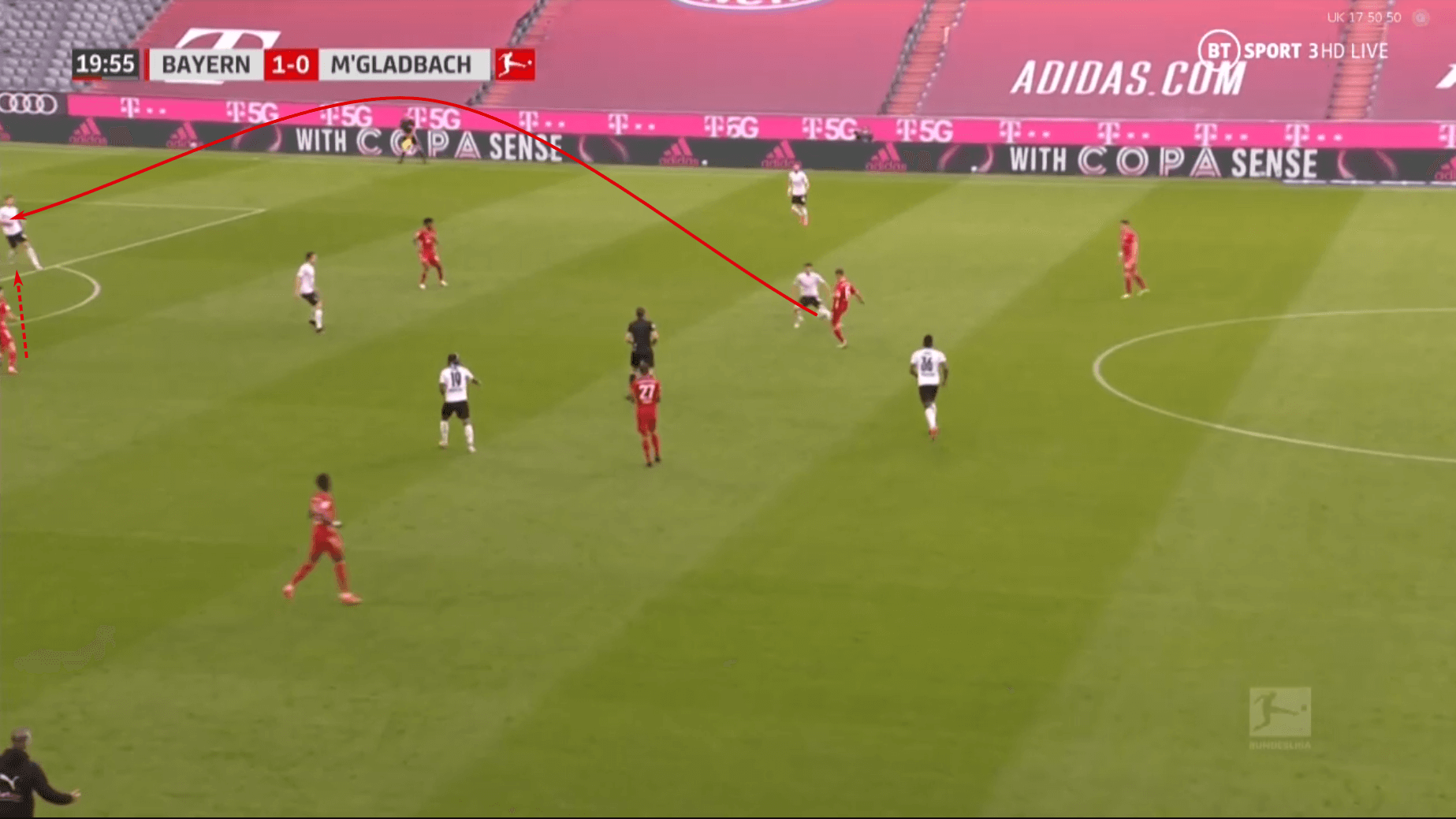

As Borussia Mönchengladbach collapse on Lewandowski, he finds Thomas Müller isolated against Matthias GInter. The pass is played into Müller, who receives the ball on the half-turn, allowing him to continue the team’s vertical move up the pitch. To his left, he has Jamal Musiala and David Alaba in a 2v1 against Stephen Lanier.

The pass is kicked wide to Alaba, who then cuts inside and prepares his cross. Kingsley Coman made an aggressive run into the central channel, commanding the attention of Ramy Bensebaini. Lewandowski reads the move perfectly, making the back post run to effectively switch roles with Coman. Alaba’s cross finds him at the back post and the Pole finishes off the play with a second-minute goal.

Route 1 is as simple as attacking can get. Point A to Point B in two passes in the West Ham scenario. Bayern Munich’s direct possession was much different. Although their move required just five passes before depositing the ball in the back of the net, we can see the principles of direct attacking at work in Die Roten’s possession.

First, their deep starting point and low tempo at the start of the possession encouraged the first line of the press to step forward along the vertical axis.

Second, as space widened between the Borussia Mönchengladbach lines, the Bayern Munich players intelligently positioned themselves between the lines.

Third, to play quickly and take advantage of the space readily available to them, we saw the Bayern players receive the ball in a side-on position, meaning their backs were facing the sideline allowing them to receive on the half turn. That body orientation allowed them to see the lines in front and behind them.

Fourth, knowing they had time and space to turn, the Bayern players quickly attacked space and looked to pin the defenders on the dribble.

Steps two through four were repeated twice more, then the Bundesliga champions attacked the opposition’s goal in numbers. Clever movements in the box freed Lewandowski for the goal, but it was the precision, efficiency and management of time and space to create superiorities and pin the opposition that were ultimately successful in this goal-scoring move.

Hitting the target man

The second form of direct possession we will cover is playing through the target men. Ideally, a target forward will have a large physique to physically overwhelm the opposing centre-backs. Rather than playing between the two centre-backs, you’ll often find him choosing his matchup against the less physically capable defender.

In a single central forward system, the target man must have exceptional holdup play to not only claim the first ball but hold it long enough to set it back to a teammate. By holding up the ball, he’s buying time for his teammates to push forward in the attack. He’ll often play a midfielder who’s directly underneath him before a longer pass is played behind the opposition’s backline. Up/back/through is a common pattern. Up to the target forward, back to a supporting midfielder and through to a runner in space.

In this section, we’ll look at Inter Milan’s two forward system featuring Romelu Lukaku and Lautaro Martínez. They’re your traditional striker plus secondary forward one-two punch. In the two forward formations, it’s common to see the target man ask for the ball to his feet while the second forward reads what’s available to him, either running behind his striker attacking height or playing underneath his teammate. If he plays underneath, this will again offer the up/back/through pattern.

In the case of Inter Milan, they’re fortunate to have a big man who can also run behind the opposition’s backline. Lukaku’s a nightmare matchup for opposing centre-backs because he’s one of the most versatile #9s in the game. Let’s get a sense of how the Nerazzurri use the Belgian.

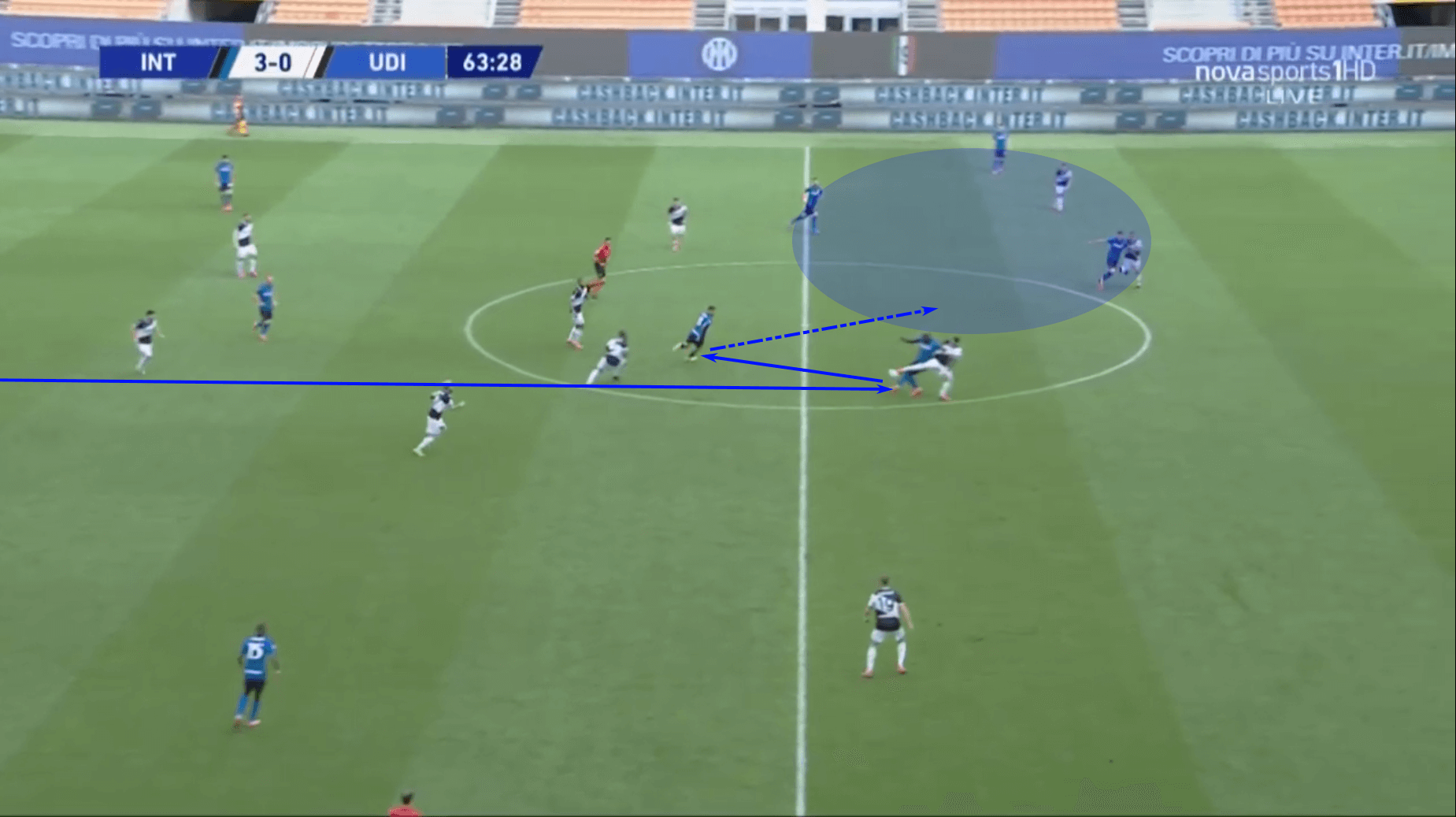

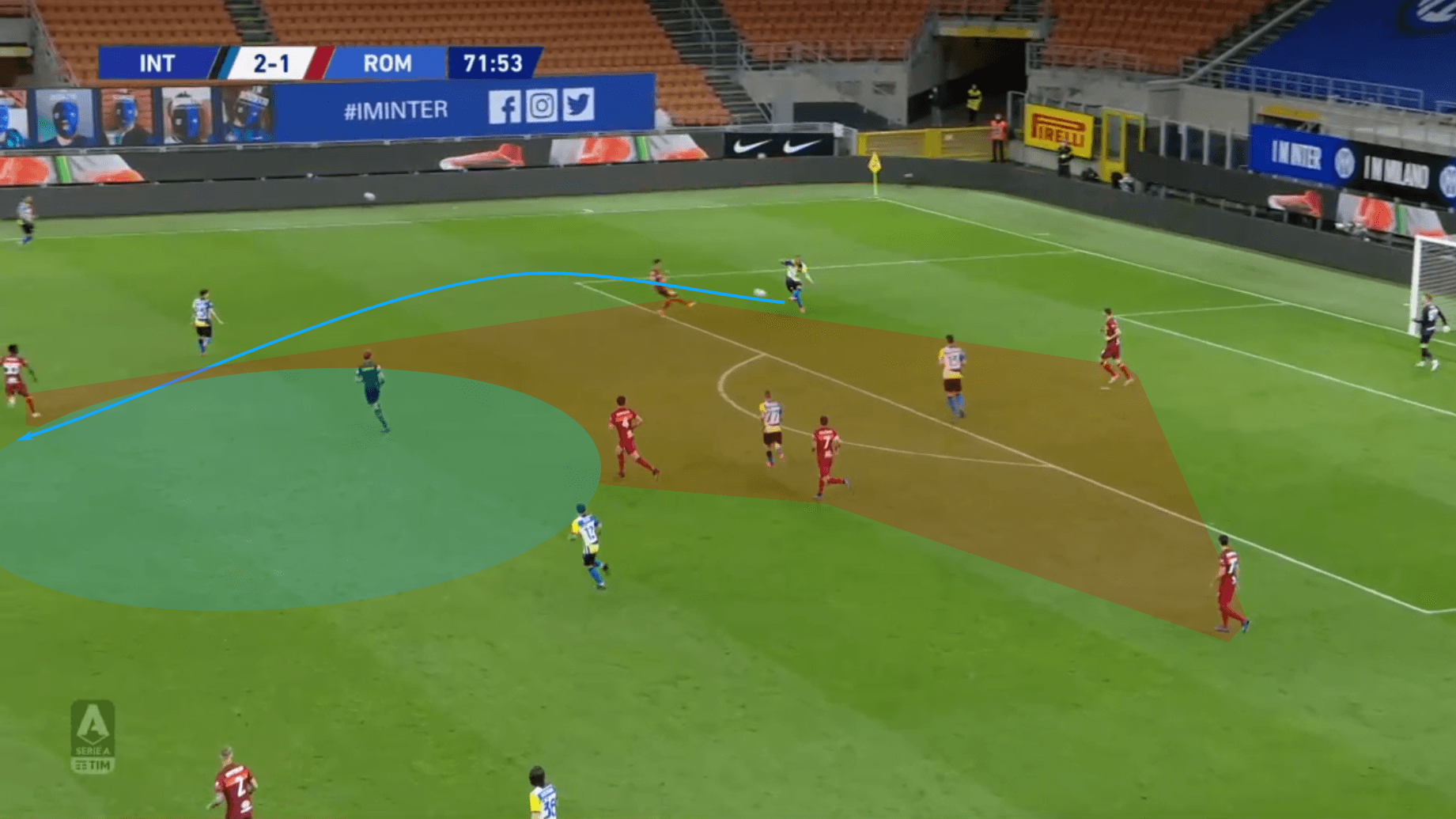

In our first image, Inter have played long into the path of Lukaku, who fights off his defender to win the entry ball. Meanwhile, he has support underneath and Inter have established a high, left-sided overload with a numerical superiority. As Lukaku receives the ball, he sets it into the path of Martínez who then carries forward as Inter attack 5v3, leading to an Ivan Perišić goal.

Inter not only have a prototypical #9 who’s reliable in winning the first ball, but Antonio Conte put the structure around him for the Nerazzurri to get the most out of their target forward. Even without the left-sided overload, Martínez’s position between the lines underneath Lukaku immediately sets the pair up for a 2v1 attack.

Looking at the left-sided overload, this is a situation where an asymmetric attacking shape gives Martínez a natural target once you receive the layoff from Lukaku to establish the up/back/through pattern. One of the key priorities is to give the second attacker options to play forward. Even though Martínez initially progresses through the dribble, Inter Milan’s 3v2 to his left limits Udinese’s defensive options. Martínez’s decision to delay the pass and progress through the dribble also allows his left-sided teammates to attack centrally, further disconnecting the two defenders and leaving Perišić open for his move on goal.

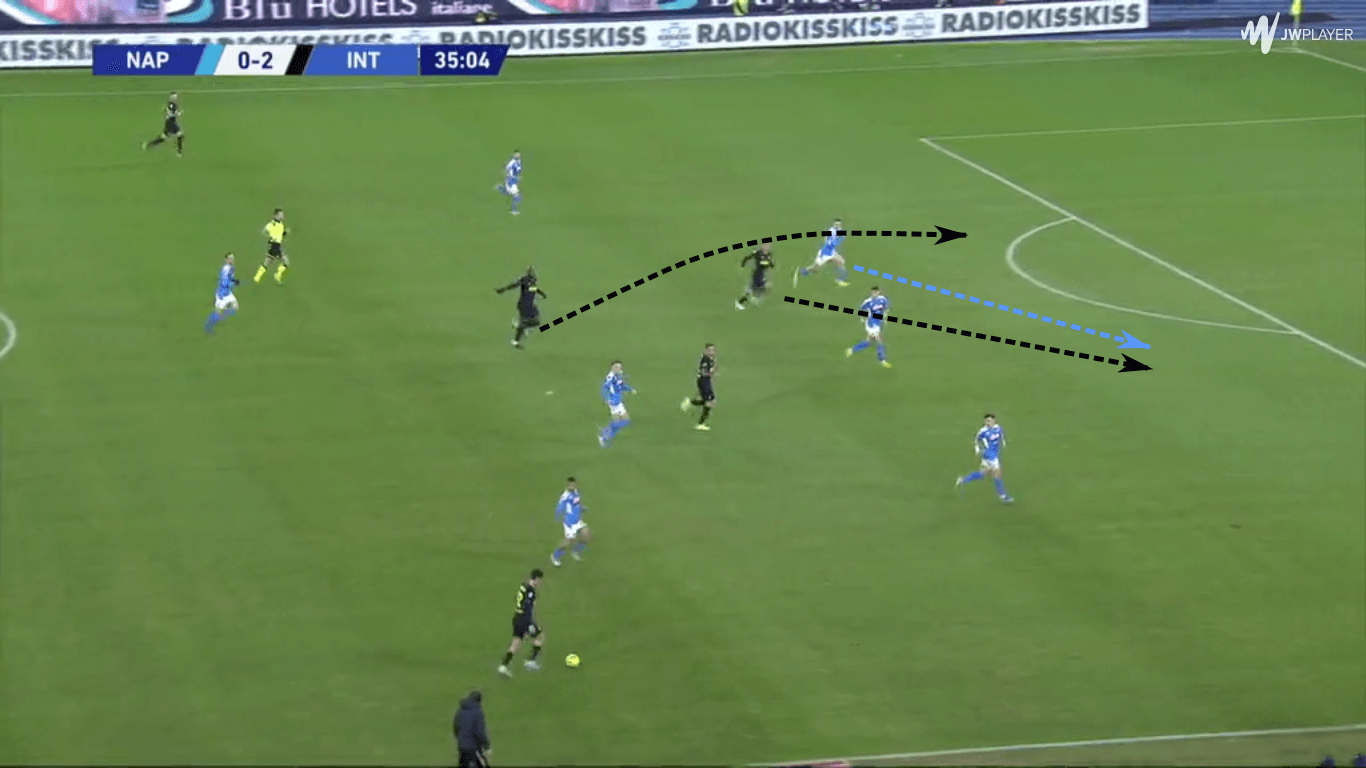

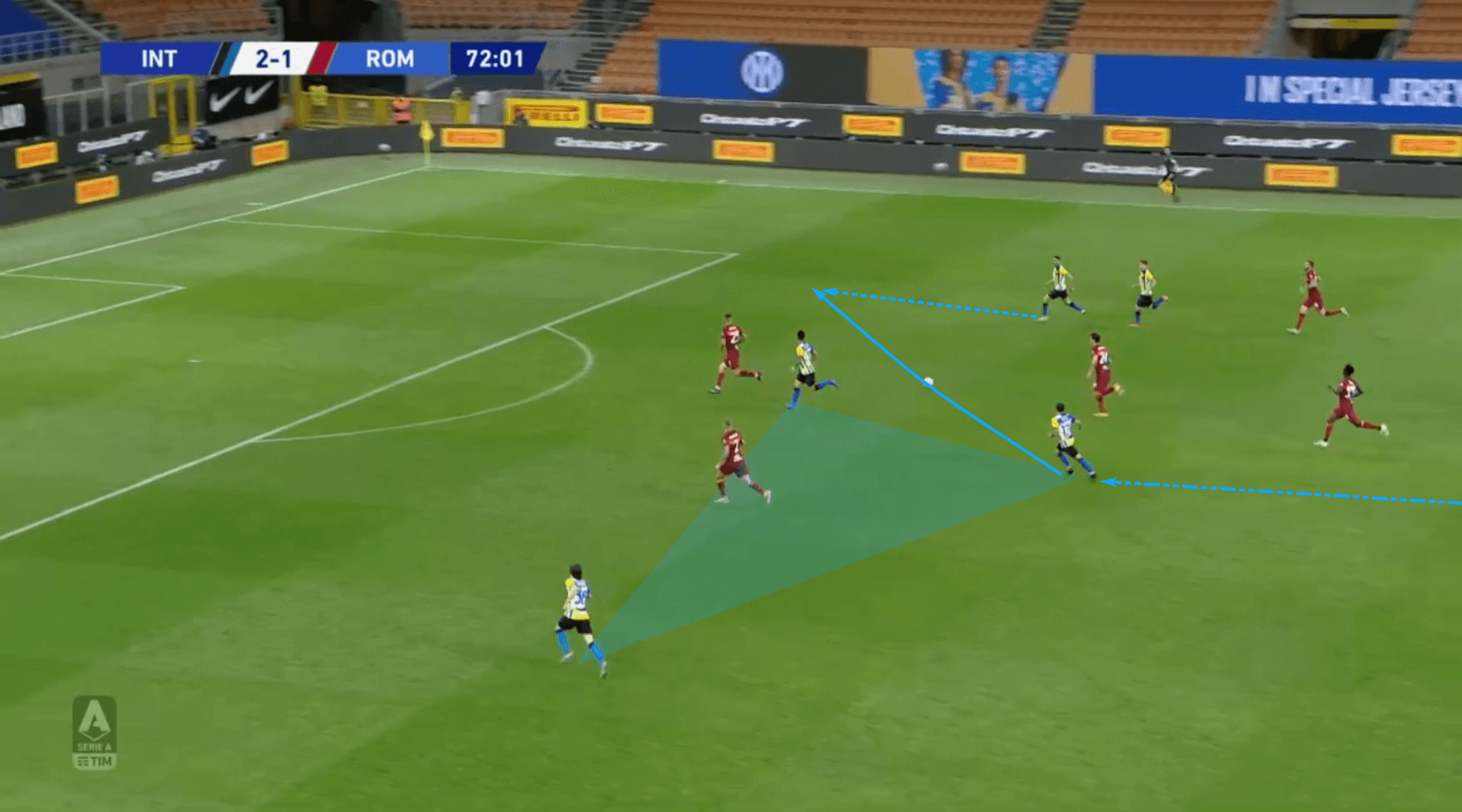

Finally, and this analysis is specific to teams with a mobile target forward, one idea is to play into the #9, initiate the up/back/through pattern and then use the second forward and wingers to attack the space behind the backline. As the second forward and wingers make their runs, they drag the opposition’s defenders with them. As we see in the final image of the section from the match against Napoli, the movement of Martínez pulls the far-sided centre-back, allowing Lukaku to kick it into 5th gear and overlap his teammate. This leaves him alone at the back post, an ideal setup for the cross.

Some of the key ideas for playing off the target forward include support underneath, runners to attack space behind the backline and initiating patterns such as the up/back/through. This direct possession approach is once again targeting an efficient move up the pitch, getting the majority of the team’s ball progression through two passes. In many cases, only three total passes are necessary to go from the defending third to the attacking third.

For target man play to be successful, there’s not only a need for a dominant striker but also runners in support. Those runners in support are both there to receive this set pass and, in a more general sense, to win the second ball. If the second forward or one of the wingers tends to stay higher up the pitch, tightly connected to the striker, there’s the option for flick-ons into the space behind the backline, which streamlines the possession even more. Granted, the odds of success are significantly lower when attacks are dependent on winning the second ball, but it’s still a low-risk/high-reward option for rapid progression up the pitch.

Indirect buildout to direct attack

If we were playing a game of “one of these things is not like the other,” the indirect build-up to direct possession would win the prize. Unlike the first three forms of direct attacking tactics we have discussed, this one starts with quick ball circulation at the back. If the other tactics were low-risk/high-reward styles, this is the high-risk/high-reward alternative.

From a tactical standpoint, the basic requirements are a goalkeeper and backline who are press resistant and midfielders who can move against the flow of the opposition’s press to offer pressure relief through split passes.

The other principle in effect is timing. From a tactical standpoint, this is the key ingredient to a successful indirect possession to direct attack. The rapid ball circulation at the back is designed to lure opponents into the high press. And not just a high press, but one that provokes the advancement of the opposition’s midfielders along the Y-axis. This is a case of the attacking team overloading at the back to unbalance the opposition. Creating a deep vs high attacking dichotomy leaves the opposition’s midfield in no-man’s-land. The first two lines of the press are essentially condensed into one, leaving a massive gap between the first line of the press and the backline.

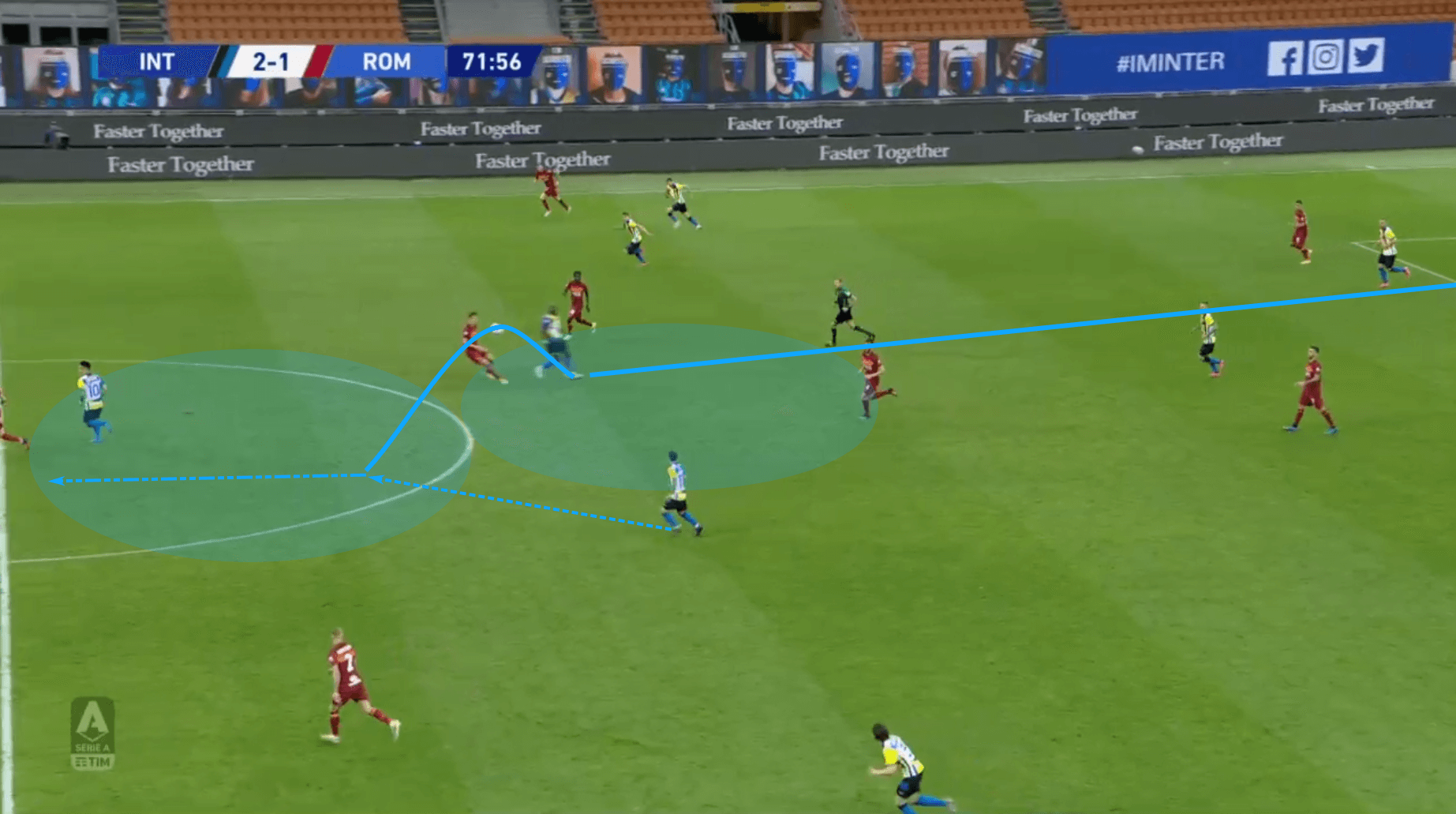

Pulling a sequence from Inter Milan’s match against Roma, we can see these principles in concrete form. Inter Milan’s centre-backs and central midfielders connect at the back while the wingbacks push higher up the pitch. Inter’s security in possession provokes the Roma midfield to push higher in support of the forwards. By the time Inter plays out of the press, Roma have five players in or just outside of the box. Ebrima Darboe is the lone Roma midfielder in the centre of the pitch, which gives Inter an opportunity for central progression.

Once again, it’s their big target man, Lukaku, who drops into that space. Rather than holding the ball up, a clever flick with the outside of the boot bends the ball into the path of Stefano Sensi, who has room to run.

Sensi progresses the ball into the attacking third through the dribble. Roma can do nothing more than attempt to delay the attack. As they delay, it’s Inter Milan that are best positioned to catch up to the run of play. Once time and space are condensed, Sensi releases his runner into the right half space. Note that as the ball makes its way to the right, the Nerazzurri still have a 3v2 numerical superiority in the central channel and left half space. The pass to the right is followed by a searching ball into the three central runners.

Though the Serie A champions didn’t manage a goal in this sequence, it’s a beautiful example of a direct attack that follows from a prolonged build-out.

In terms of the attacking principles at play, timing the attack is pivotal. As the goalkeeper, backline and deeper midfielders connect at the back, they’re waiting for the opponent to take the bait and overcommit high up the pitch. That unbalanced presence in the high press is easily seen in the over-commitment of numbers high up the pitch. However, the greatest cue that it’s time to play forward and play out of the press is in the feel of possession.

One coaching point I like to use, be it with a deep build-out or an overload higher up the pitch, is that we know it’s time to play out when we can feel it’s getting difficult to retain possession of the ball. Players may not have the time or presence of mind to count the number of players the opponent has committed to the press, but they will feel the difference between low-pressure ball circulation and the high-pressure ball circulation that follows. That feel is the key.

As it feels more difficult to retain possession, the players with optimal body orientation, meaning they are best positioned to see the pitch in front of them, are the ones responsible for playing out of the press. Anyone playing back to goal, which is often your midfielders, must play simply, typically playing the way they face. It’s the players with better vision and body orientation to play out of the press who dictate the WHEN. As pressure mounts and the group collectively feels time and space getting tighter, it’s those players whose body orientation allows them to play out of the press who determine when to progress from preparing to attack the opposition to attacking the opponent.

That’s what’s happening near the ball. Away from the ball, wide players must find the balance between cheating higher up the pitch to connect with the forwards and offering a deep drop if necessary to retain possession. High central players must coordinate their movements to create passing lanes for progression. That’s exactly what we’ve seen with Lukaku. Starting high up the pitch, you could see the time for progression was nearing, cueing his deep drop to receive the outlet pass. His concern was not in keeping possession or in working hard to remain an option at all times. Rather, it was to provide the right option at the right time.

As we saw in the Inter Milan vs Roma game, if the attack is timed correctly, it offers an exceptional shot creation opportunity.

Counterattacking

Moving along to counterattacking, this is the one form of direct possession that is exclusively aligned with transitional attacking. By its very nature, it’s an attack that starts with a ball recovery. It’s an attack that is a direct response to the opposition’s attack.

Like each of the other forms of direct attacking mentioned in this article, one of the core principles of counterattacking is rapid ball progression. Just like the other attacks we’ve covered, minus Route 1, effective counterattacks are not only reliant on quick progression, but also the precision of the attack and the willingness of second and third attackers to push forward. Since the opponent is still transitioning out of their expensive attacking shape, there is space to claim and counterattacking is a race to arrive first.

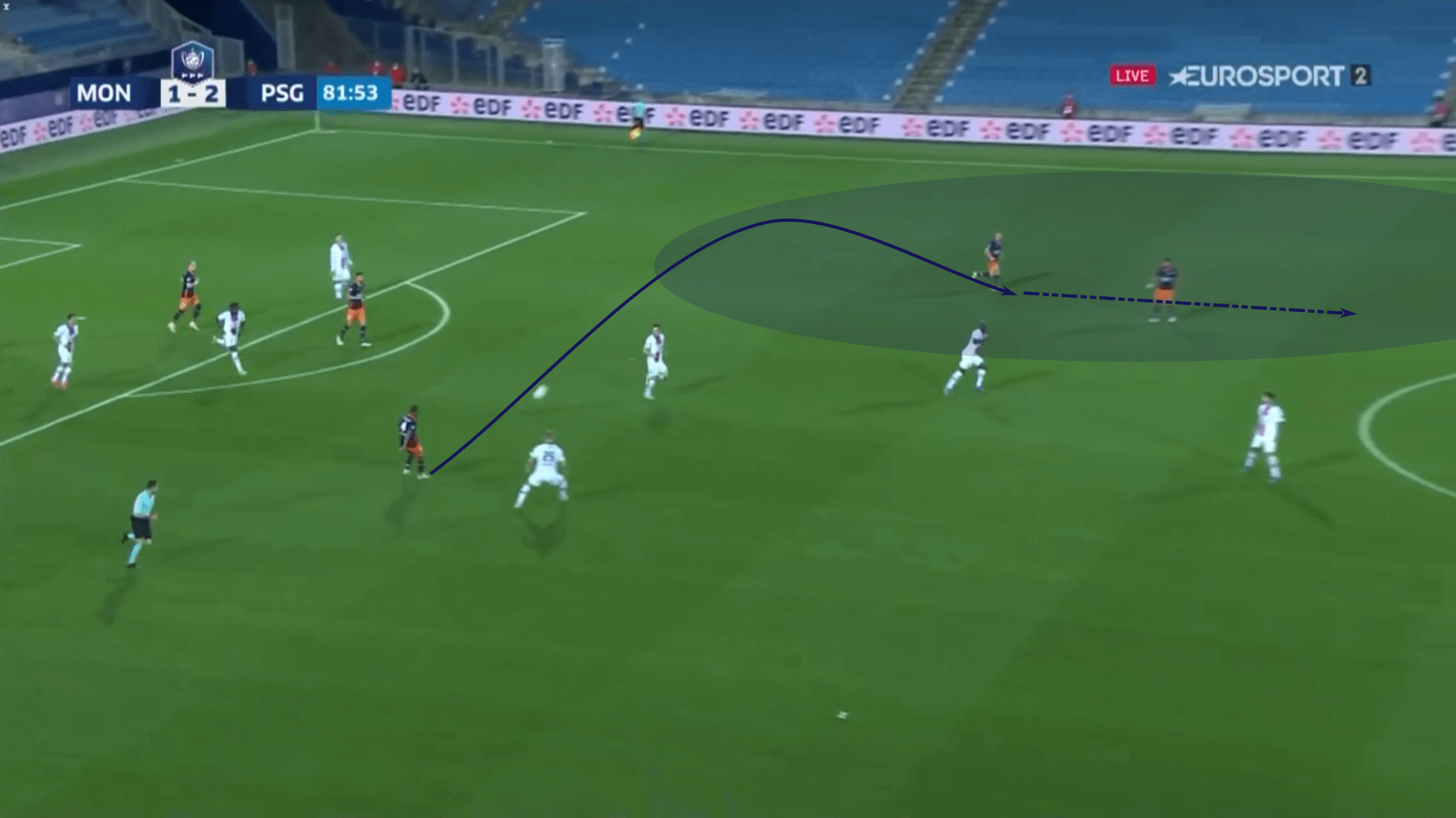

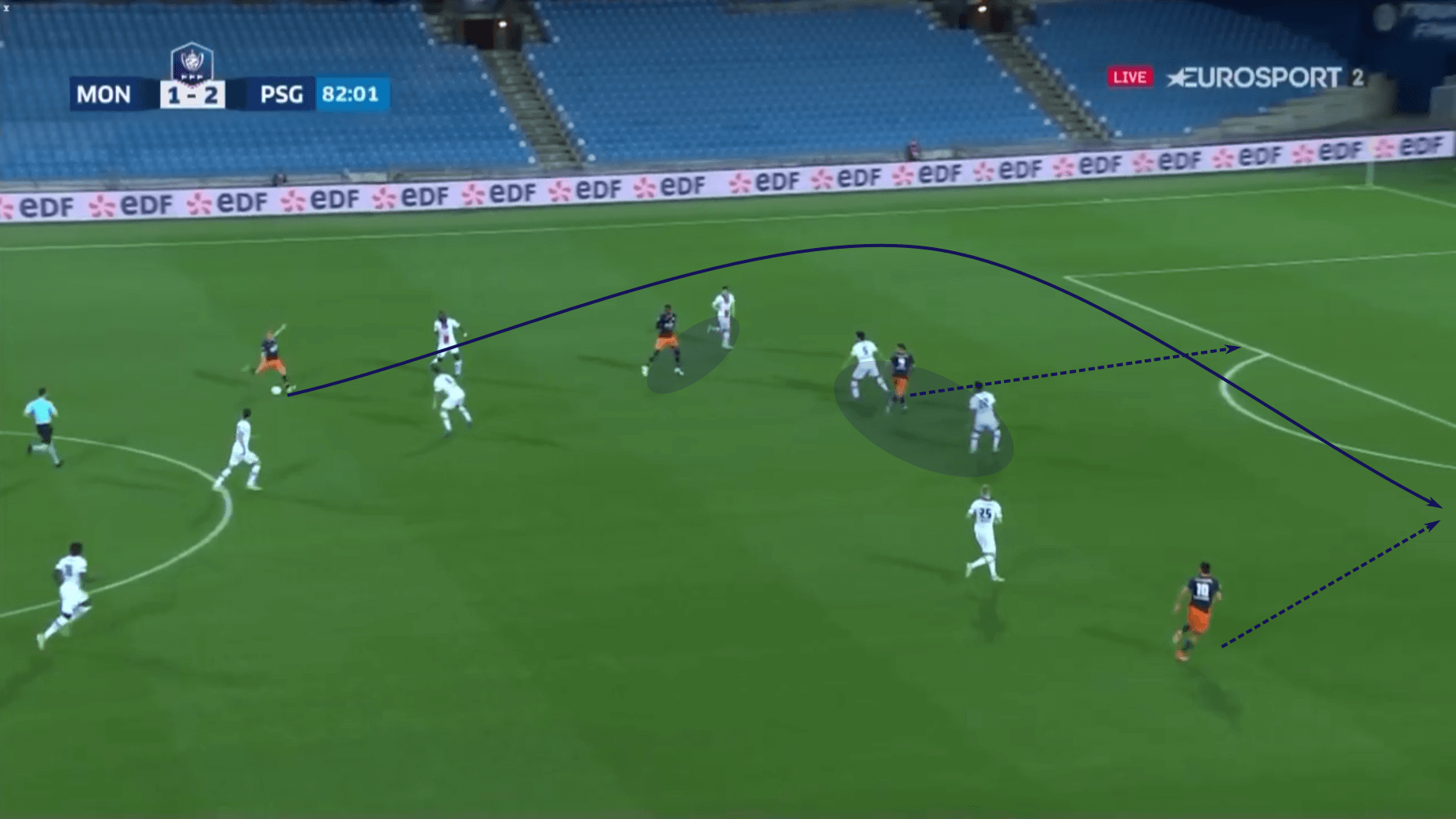

Our case study comes from the Coupe de France semifinal, Montpellier vs PSG. In the sequence, the Parisians have the ball deep in the Montpellier end of the pitch. The hosts are pinned back, but they also know the Ligue 1 super team has left themselves open to the counterattack. Upon winning possession of the ball, the runners initiate a full sprint up the pitch as Hilton plays the ball over the press. Montpellier have room to run on the left side of the pitch. The race is on.

Mihailo Ristić carries the ball approximately 35 m in the left half-space. As he dribbles, he has two players ahead of him occupying three members of the back four. That leaves Gaëtan Laborde isolated with Mitchel Bakker on the far side. Bakker has lost track of his opponent, freeing Laborde to make his unopposed back post run.

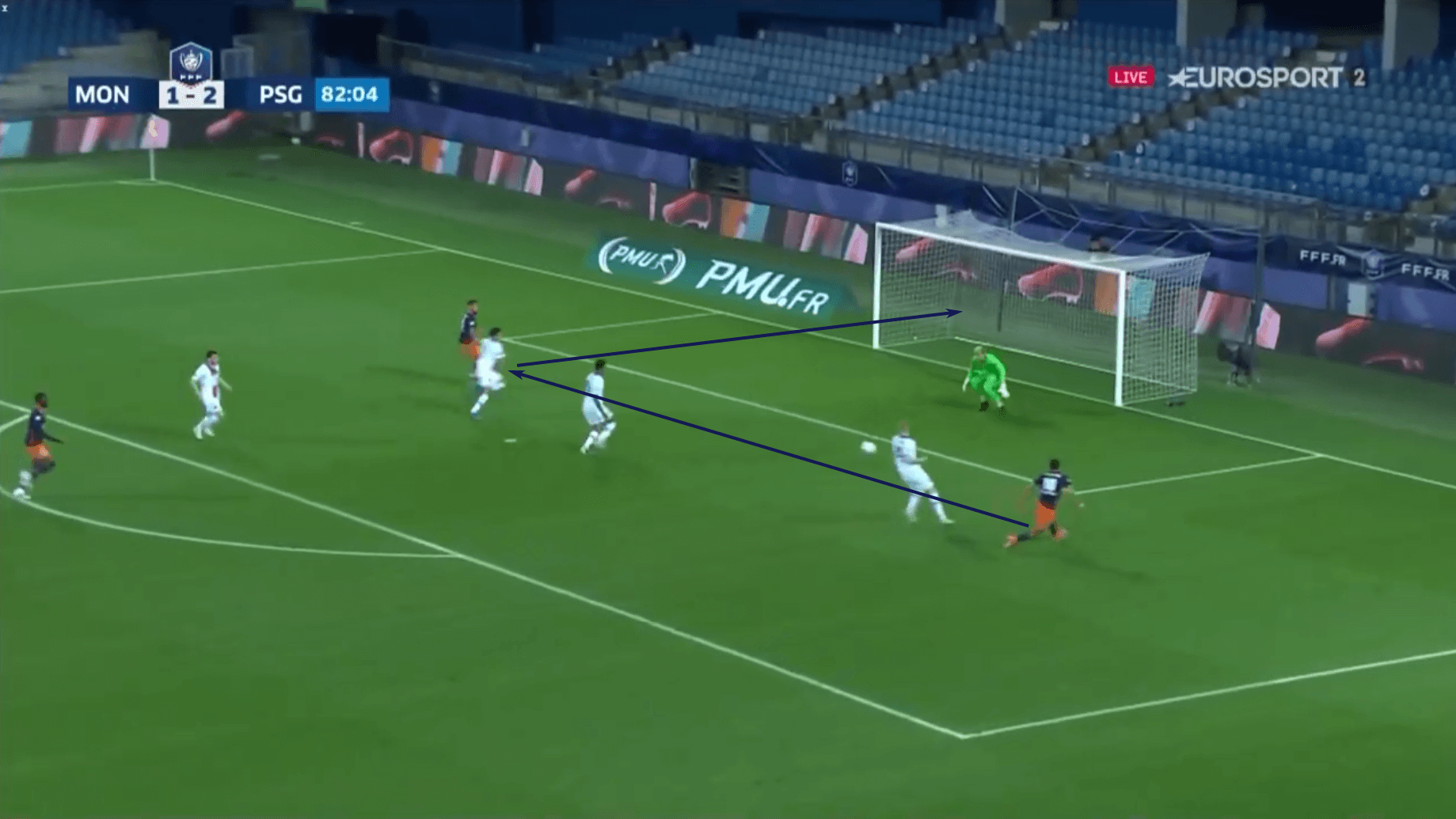

The pass is played perfectly into his path. A simple square ball across the face of goal finds Andy Delort for the game-tying goal.

Some of the key principles in that sequence are the ability to break the press, leading the second attacker into space and the psychological commitment of each runner to carry out the attack. Add in the intelligent movement in the attacking third to free up Laborde for an uncontested run into the box and you’ve got a recipe for success.

Montpellier, much like West Ham, were not a possession dominant team during the 2020/21 campaign. Of the 98 teams in the UEFA Top 5 leagues, the French side’s 45.3% possession share rated 71st. That got me thinking, are there any creative ways possession dominant sides can implement counterattacking principles?

Domagoj Kostanjšak has more detail for you in his August magazine analysis, Tactical Theory: Why intentionally losing the ball can be your greatest playmaker, but I will note here there is an opportunity for possession dominant sides to counter right after the opponent loses the ball in their own counterattack. One such example comes from Manchester United.

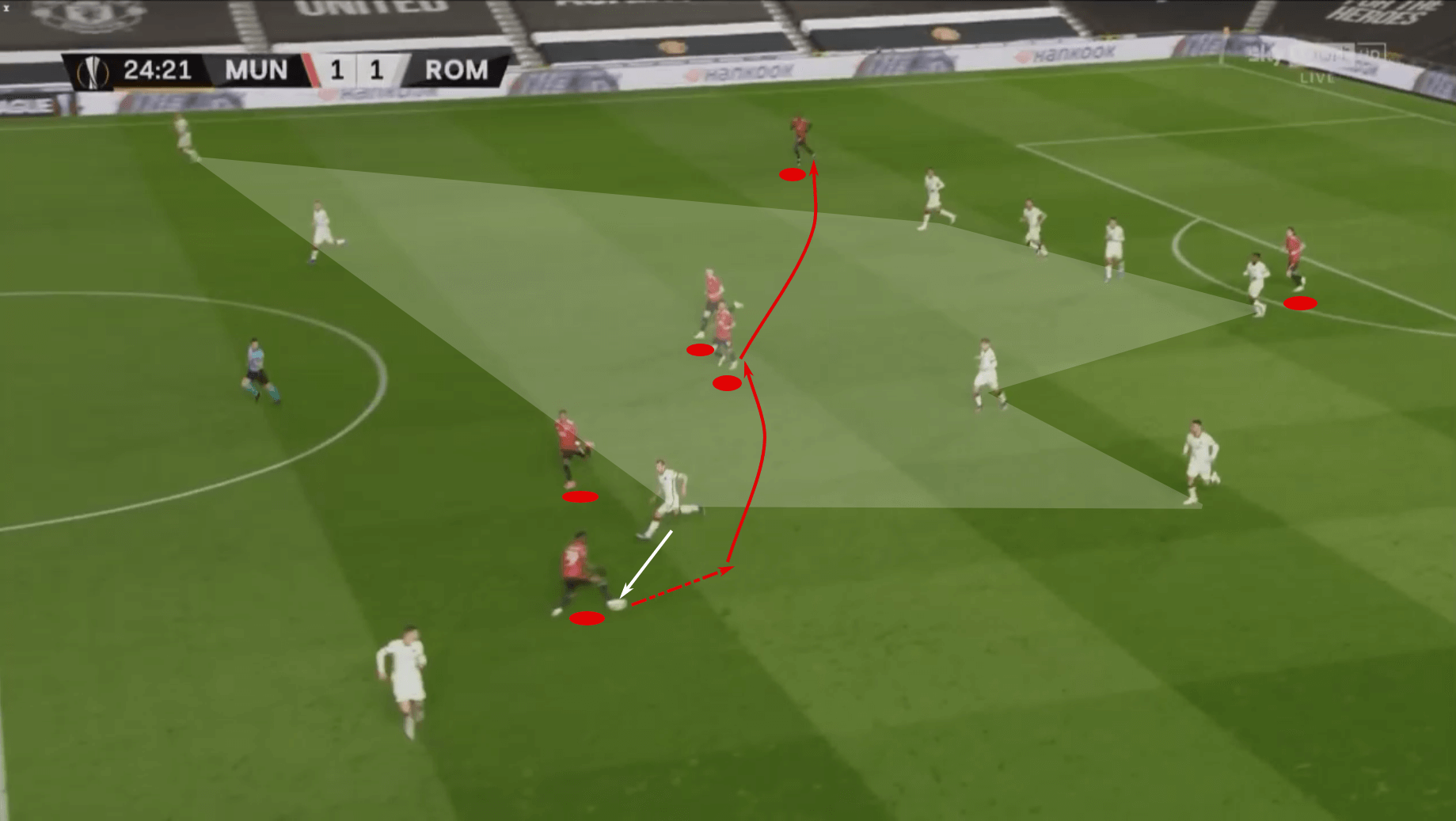

Roma once again serves as the victimised club as their counterattack is brought to an end by an Aaron Wan-Bissaka interception. Once the right-back gains control of the ball, he plays to Bruno Fernandes who completes the switch of play to Paul Pogba in the left wing. Notice in the sequence that as soon as Roma gain possession, the players are in a full sprint forward to support the attack and get behind United’s lines. However, once Manchester United regain possession of the ball, their network is still fairly intact and well-positioned in the huge gap between Roma’s lines.

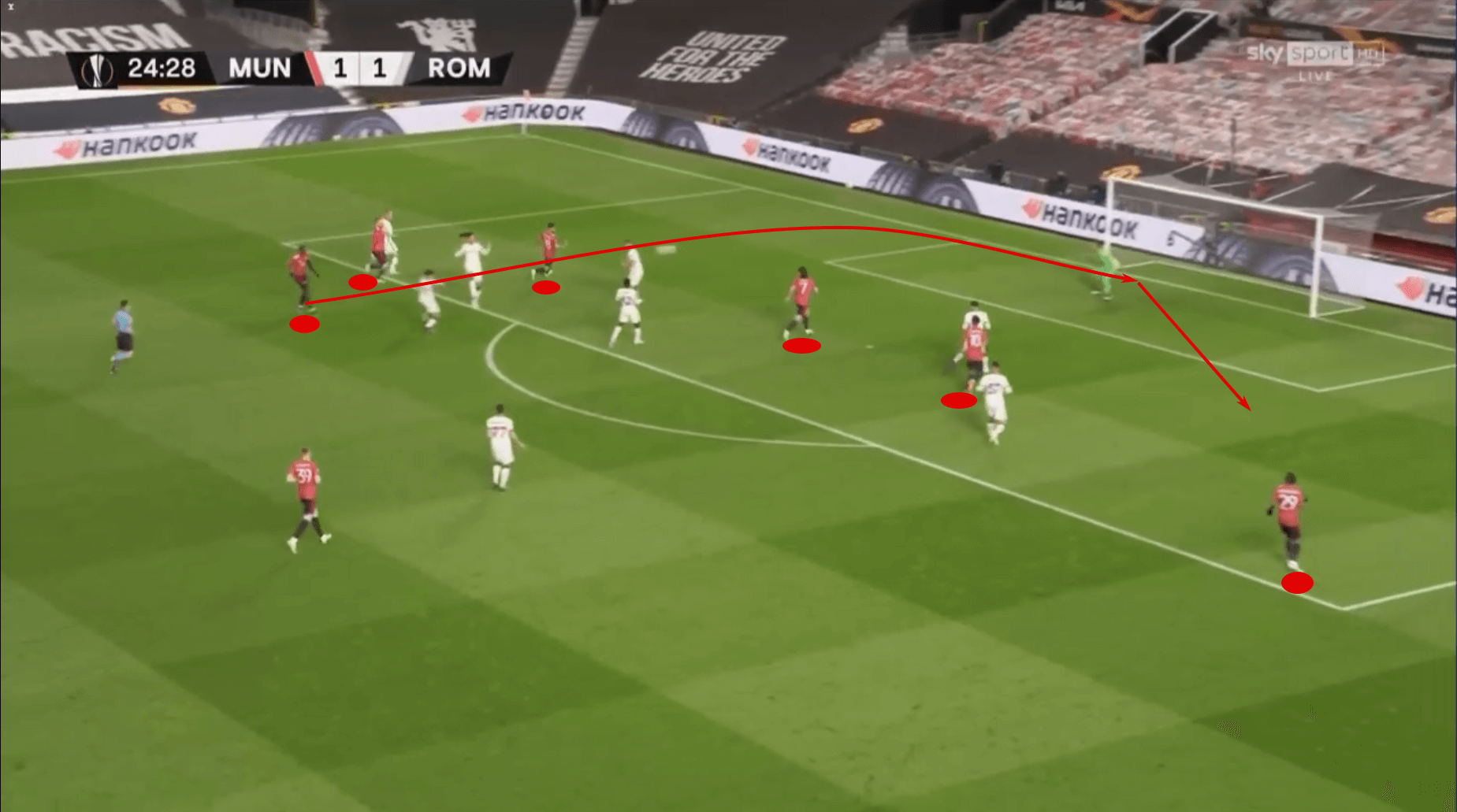

Pogba cuts inside and takes a shot, which is blocked, but the reason I’ve included this image is to show the number of Manchester United players in the box. Edinson Cavani is all alone in the middle of the box, Marcus Rashford is positioned to pounce on a potential rebound as well and Wan-Bissaka has pushed up the pitch in the wing. In fact, it’s the outside-back who recovers the loose ball after the Pau López save.

The big picture for the possession dominant sides is that an effective counterpress then creates their own counterattacking opportunity and their players, who are still recovering from their expansive attacking shape, are well-positioned to immediately counterattack.

How defensive tactics create direct possession opportunities

Let’s build off of the Manchester United example. In that instance, their counterpress and interception allowed them to counterattack an unbalanced Roma squad that was caught out in a counterattack of their own. Other than counterpressing situations, let’s look at how squads can use defensive tactics to create direct possession opportunities. In fact, let’s head straight to the pitch for some examples.

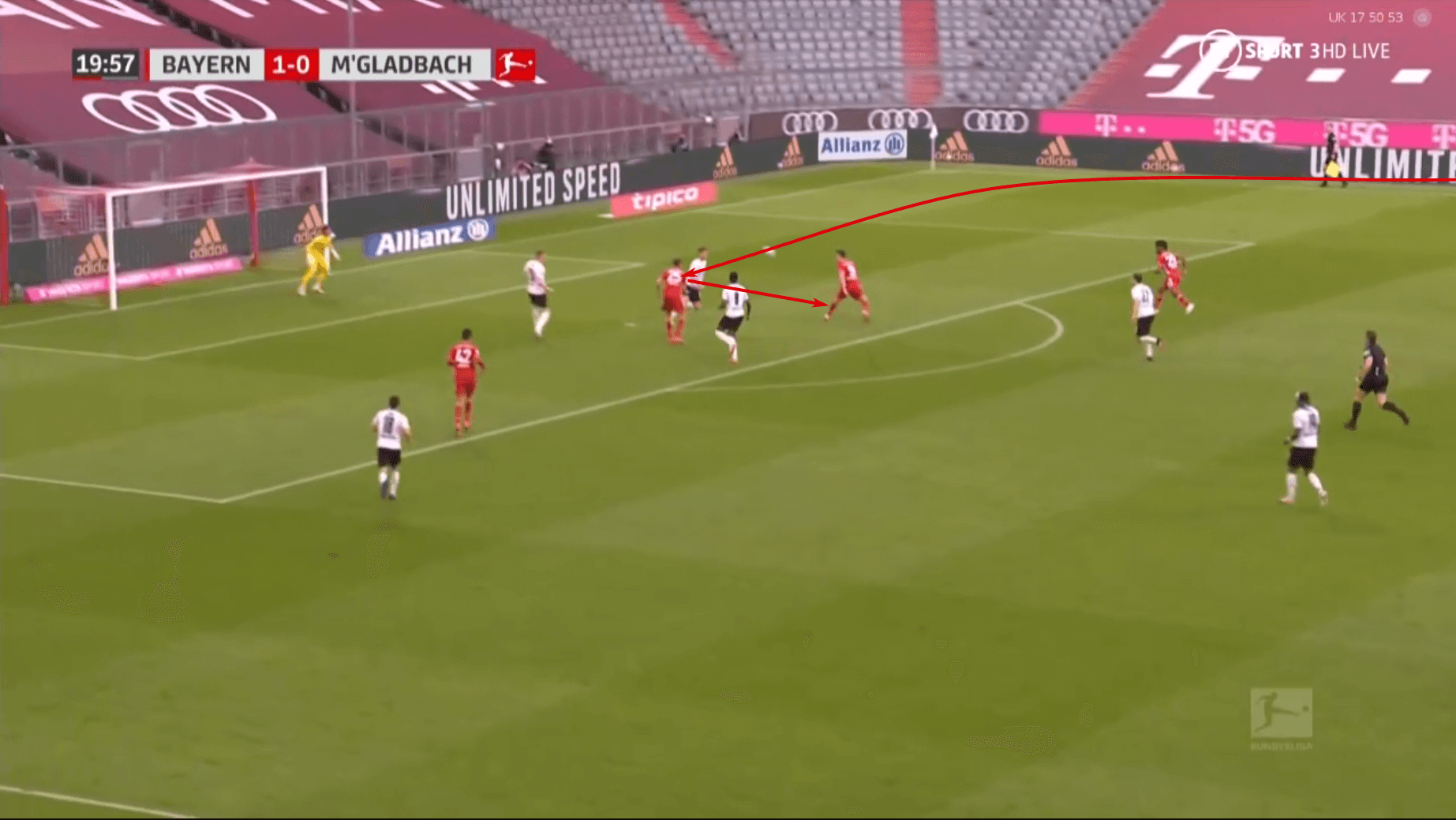

The first instance comes from Bayern Munich’s match against Borussia Mönchengladbach. In the 20th minute, Mönchengladbach attempted to play out of the Bayern Munich high press from a goal kick. If it sounds like they’re trying to unbalance the Bayern Munich defence along the Y-axis, creating an opportunity to transition from an indirect build-out to a direct attack, you’re correct.

However, Bayern were able to effectively defend the build-out with just four players committed high up the pitch against Mönchengladbach’s six. That allowed Bayern to keep numbers behind the ball and play for the pass out of pressure. That pass came in the form of a Yann Sommer 40 m pass under heavy pressure. To his credit, the Swiss goalkeeper hit his target, but the ball was not controlled and spilled into the path of Kimmich.

Knowing he had numbers in the Mönchengladbach box, Kimmich sent the ball right back into the penalty area with his first touch.

Müller won the first ball easily, chesting a pass into the path of Lewandowski who applied the finish.

In Bayern’s case, it was a systematic approach to the high press that drove Mönchengladbach closer to their endline, forcing a rushed pass forward that led to Der FCB’s direct possession. Though the Bundesliga champions were 4v6 during the Mönchengladbach build-out, Munich’s tightly connected network offered a better target for Kimmich’s ball than the more expensive Mönchengladbach defence could handle.

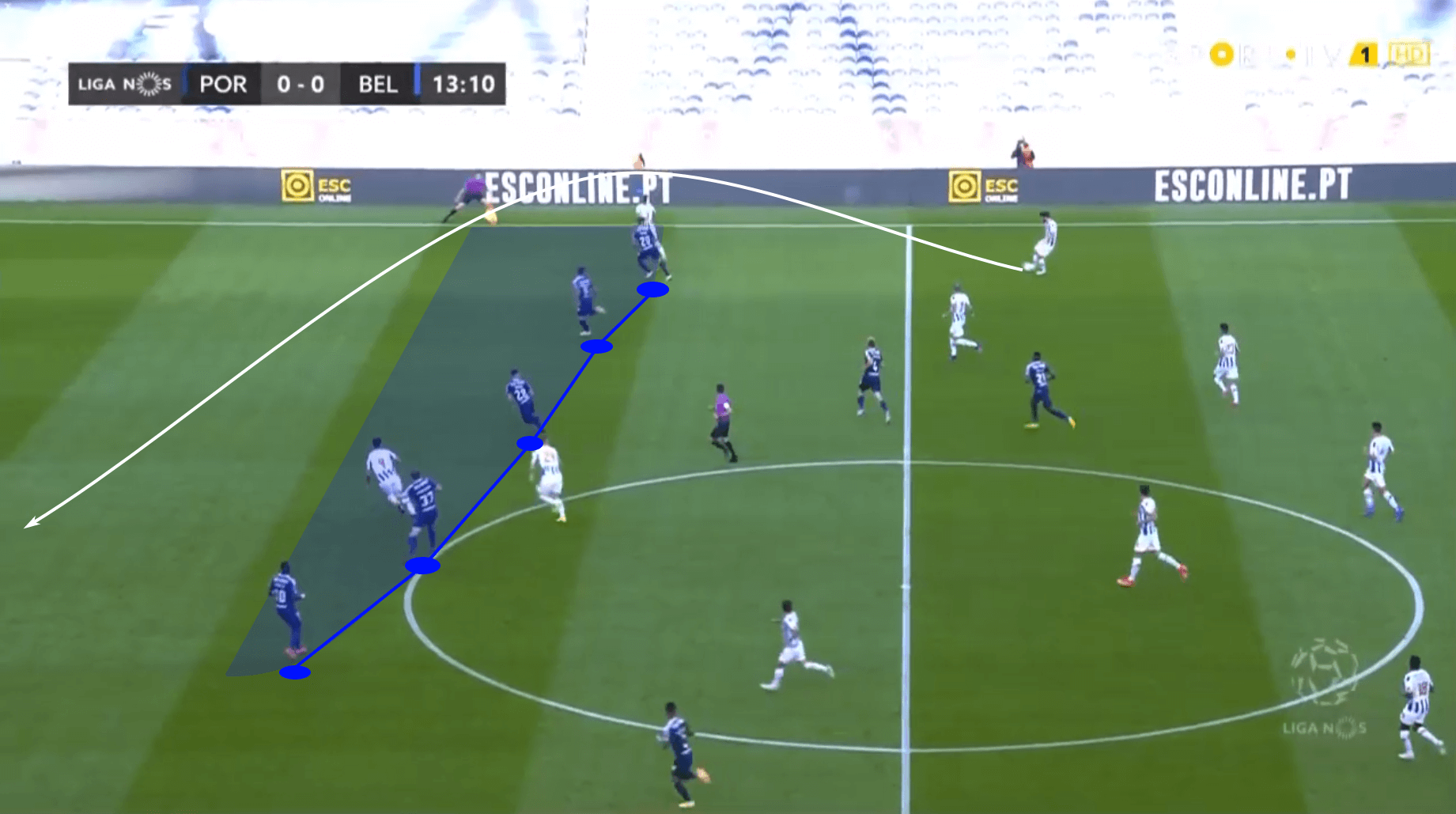

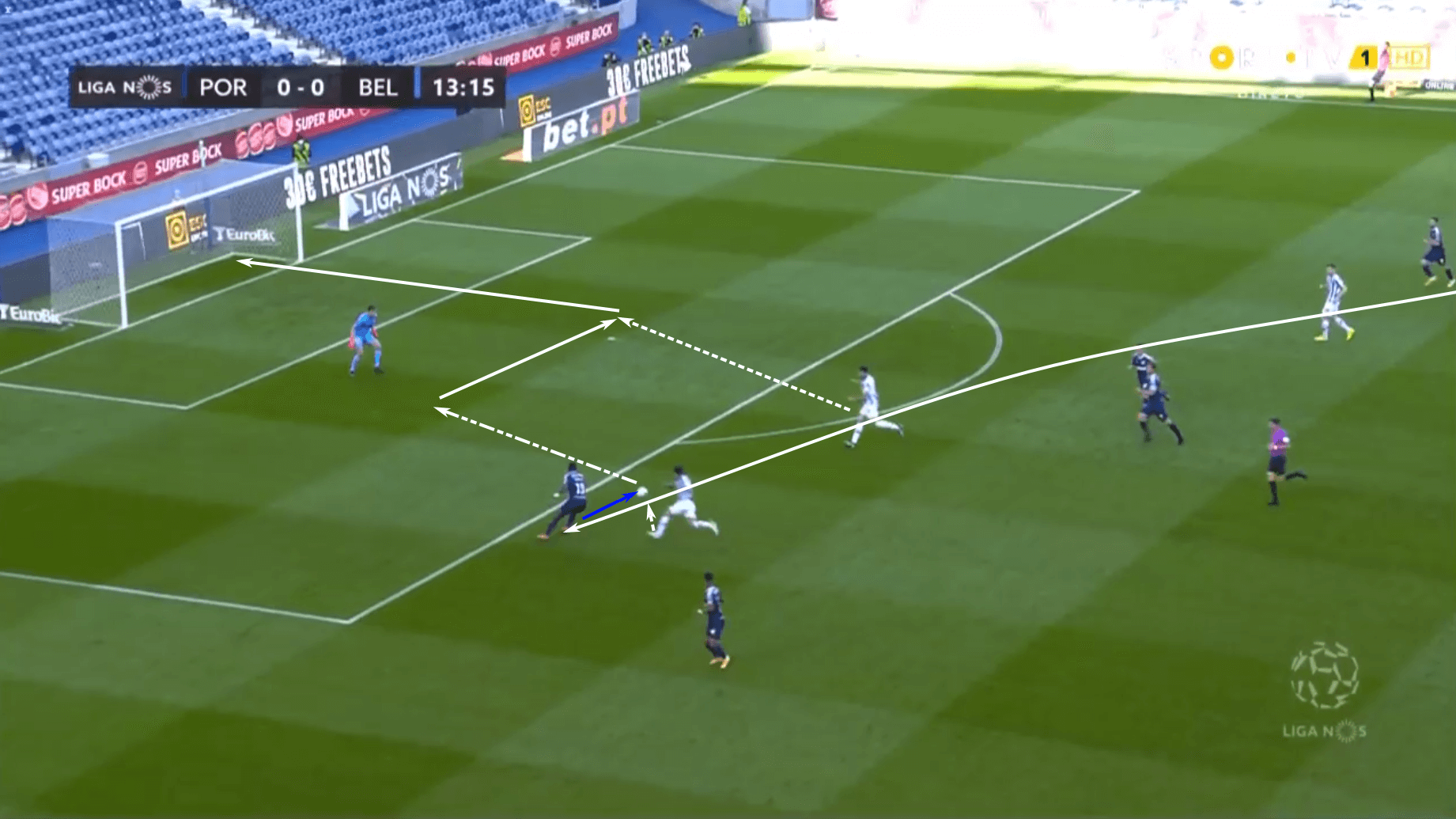

The high press isn’t the only way teams can create opportunities for direct possession deep in the opponent’s end. Our final example in the article comes from the Portuguese Liga NOS with Porto hosting Belenenses. Sérgio Conceição’s sides are known for their opportunistic attacking, particularly in sending low-risk/high-reward passes targeting the opposition’s backline. In this instance, Mehdi Taremi made his move behind the backline, attempting to latch on to a Sérgio Oliveira long pass. Silvester Varela, a wide forward by trade, is caught behind Gonçalo Silva, keeping Taremi onside.

However, Varela wins the race to Oliveira’s pass. Initially, it looks like he has accounted for his positioning error, but a horrible first touch puts the ball directly into the path of Toni Martínez. The Spanish forward picked up the loose ball and dribbled towards Stanislav Kritsyuk before teeing up Taremi for the opening goal.

The opportunism in this sequence is in the willingness of the Porto side to play into the gap between the backline and the goalkeeper, forcing the defence to navigate a contested ball while running towards their goal. There is a counterpressing element here, but it’s really the willingness to play the odds that opens up their direct, albeit brief, possession.

The elements of play are 1) the willingness to play a low-risk/high-reward ball behind the backline despite the low chance of latching onto the pass, 2) pursuit of the ball to either gain possession or 3) pressure a defender running towards his goal with limited options. In the end, Porto’s pursuit is rewarded with a Belenenses mistake, leading to the goal.

Conclusion

Far from the demeaning hit and hope implications in the direct vs possession arguments, direct possession can take many forms. The best attacks are not reduced to pure chance. Rather, teams that best implement direct possession employee tactical nuance to create superiorities and optimise opportunities for progression.

While there’s less of a need for the intricacies of indirect possession and the tactical nuances of positional rotations and positional play, direct possession is a means of ruthlessly efficient progression in a clean, calculated manner.

Tightly connected networks outside the immediate line of pressure allow teams to break lines. If done well, that first pass will target a player between the lines or someone with acres of space in front of them. Once that line is broken, the attacking team immediately shifts their mentality to pin the next line and break through the resistance. The move is quick, lethal and a necessary skill in the modern game. Deride direct possession at your own risk.

Comments