This tactical theory will analyse how teams can attack the box in a traditional 4-3-3 (or 4-2-3-1) formation. Examples from Roberto De Zerbi’s Brighton and Ange Postecoglou‘s Celtic will be analysed to provide insight into how goalscoring opportunities can be created in the final third.

This tactical analysis will focus on how central midfielders can get in behind the opposition’s defensive line using corner runs to provide cut-back options. The forward players’ supporting movements to optimise scoring opportunities from cut-backs will be included in this analysis. Options for crosses from the half-spaces, in front of the defence, will also be included. Additionally, there will be a section providing examples of how to implement these tactics through coaching sessions.

Corner runs

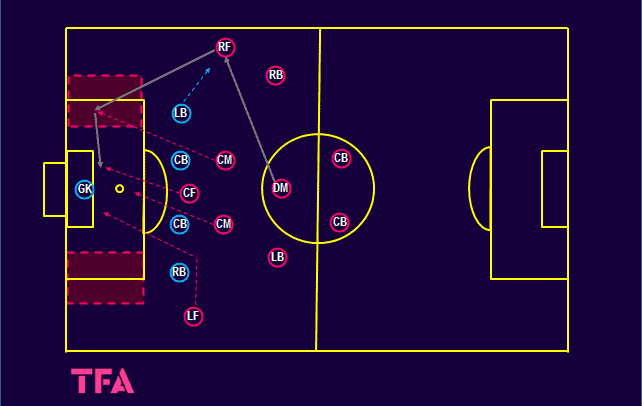

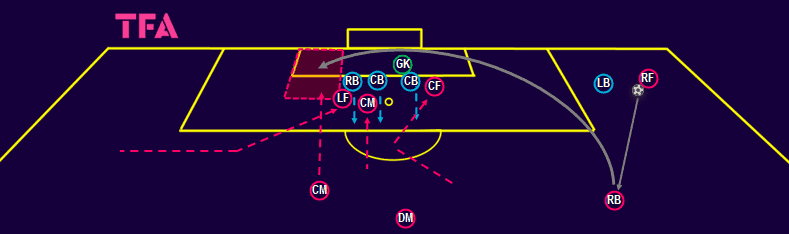

One way for teams to work the ball in behind the opposition’s backline in a 4-3-3 is for their central midfielders to be positioned high in the build-up phase. From advanced areas, the midfielders can make runs between their front players to receive through balls. This movement, shown in the diagram above, is often referred to as a “corner run”.

Central midfielders making corner runs are very difficult for the opposition to pick up. The defending team’s central midfielders do not want to be dragged deeper towards their own backline. This would leave the central area in front of their centre-backs (zone 14) exposed.

The centre-backs are often reluctant to track this run as this would create a gap in their backline. This could cause problems for their defensive partners by creating, at best, a one-on-one with the ball-far centre-back and the attacking team’s central forward.

The areas highlighted in the tactical diagram above are where teams try to aim these runs. Runs into these areas are hard to track, plus crosses and cut-backs delivered from here are much more likely to succeed than those from wider positions.

Postecoglou’s Celtic were a side whose midfielders were constantly making these runs when the ball was played into the wide areas. These runs were designed to do one of two things. One, create space for Celtic’s skilful wide players to cut inside to either shoot or combine. The other option, as above, is for the midfielder to receive the ball and facilitate a cut-back.

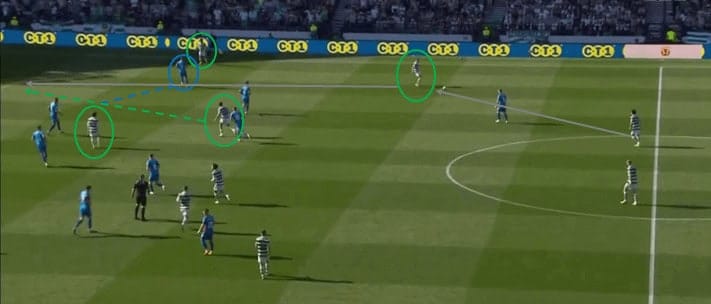

The above image shows the build-up to Celtic’s opening goal in June’s Scottish Cup Final against Inverness Caledonian Thistle. In this example, Celtic’s right-back, Alistair Johnston, plays the through ball for his central midfielder, Matt O’Riley, to run onto.

The attack began with the right centre-back passing to Johnston’s feet. As the ball travels, Inverness’s left-back steps out towards Jota, predicting the next pass to be played to the Portuguese. By positioning himself close enough to apply pressure to Jota’s first touch should he receive the ball, the left-back has created a gap between himself and his ball-near centre-back.

Before Johnston received the ball, O’Riley recognised the gap and began making his run between centre-back and left-back. The positioning of Celtic’s central forward, Kyogo, in between the centre-backs, means the ball-near centre-back cannot track the midfielders’ run. If he did, this would result in Kyogo being able to receive in an even more dangerous position.

Johnston plays the ball into the path of O’Riley who sprints into the area, away from his marker, and cuts the ball back for Kyogo to score. As this example shows, Celtic and Postecoglou prefer not to work the ball into very wide areas. Instead, they aim to get it into the highlighted areas, the cut-back zones, as quickly as possible.

Movement in the box

The movement of the forward players on the receiving end of cut-backs is dependent on how many players are positioned to attack the box. Ideally, as the above example shows, at least three players will enter the goal area for cut-backs. Typically, the ball-far wide forward, the central forward and a central midfielder will be involved. This allows two players to push the backline towards their own goal for the third player to receive alone.

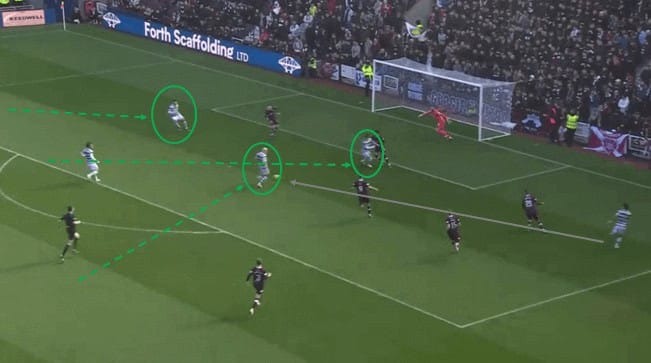

Using another example from last season’s Celtic side, the above image shows Jota, from the cut-back zone, setting up midfielder Aaron Mooy to score against Hearts in the Scottish Premiership. Jota entering the box with the ball drew Heart’s left-centre-back (of a back three) towards him.

Kyogo, who initially moved away from the ball, runs towards the 6-yard box in line with the front post. The left-forward, who began the move in the wide area, sprints towards the 6-yard box in line with the back post.

The two forwards making these runs push the central and right centre-backs back, emptying the penalty spot area. This clears the area for Mooy to sprint into to attack. With Kyogo screening the nearest defender, Mooy can shoot unopposed to open the scoring.

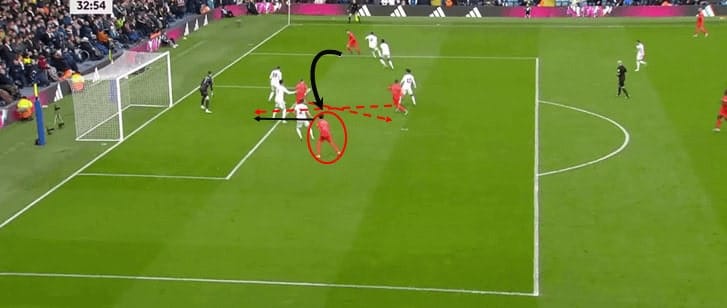

This image shows Brighton, in a similar position, creating the same triangle with two of their forwards and attacking midfielder, Alexis Mac Allister (now of Liverpool). These runs have the same effect, creating space for Mac Allister around the penalty spot.

On this occasion, though, the crosser delays the delivery and cuts back onto their left foot before again turning to deliver with their right. The cross is hung up towards the back area for the ball-far winger. As the ball is in the air, the central forward and attacking midfielder switch positions. The wide-forward heads back across the goal for Mac Allister to finish from close range.

Crosses from outside the box in the half-space

When the ball is played into deeper, wider areas, where the cross-conversion rate is severely diminished, sometimes the best option is to come back out and recycle the play. With many players in the final third, wide-forwards can put their team at risk by forcing a crossing opportunity that is not there. If the cross is blocked, intercepted or put into the goalkeeper’s hands, the team is vulnerable to a counterattack.

Instead of getting stuck in these areas, often the best option is to play back out early to a supporting full-back. This can allow for a cross from a more central location — in the half-space, in front of the backline.

Typically, when the ball is played deep into the wide area, the opposition’s backline will drop off to defend the expected cross. As the ball is played backwards, it can be expected that the backline will push up to clear the area in front of their goal.

As the backline steps up, this is an excellent opportunity for the full-back to put the ball in behind them with a first-time cross. With the advancing defenders watching the ball travel to the full-back, the attacking team’s central midfielder can sneak into the back area.

If positioned on the furthest defender from the goal, the left-forward, as in the tactical diagram above, can screen his central midfielders run. Unless he is well-tracked, the midfielder can meet the cross unopposed. This gives him the opportunity to put the ball back across the goal for one of his three on-rushing attackers.

Crossing and finishing – phase of play exercise

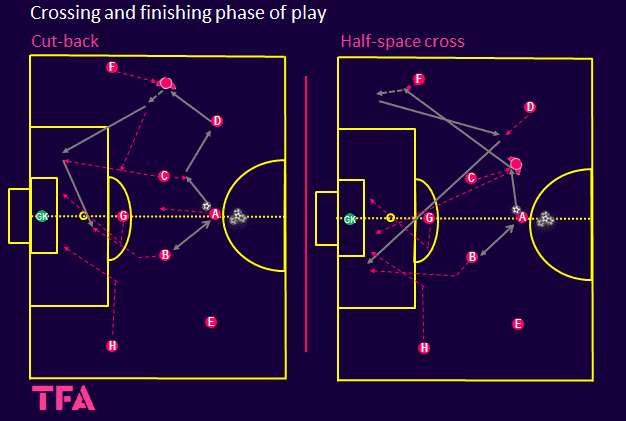

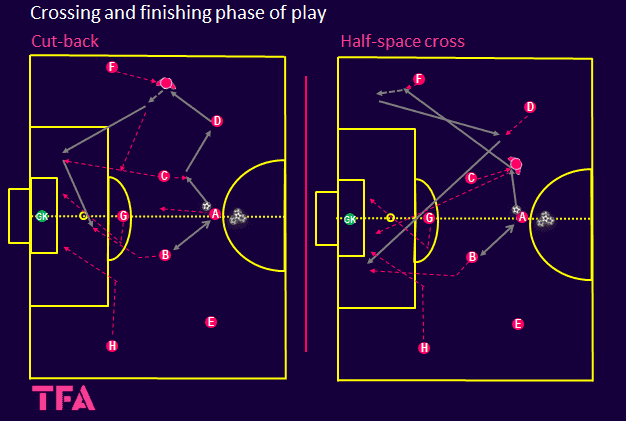

This crossing and finishing exercise is designed to allow coaches to mimic a phase of play and work unopposed on specific movements for crossing opportunities. The design of the activity should allow for lots of repetitions in a condensed period of time. The pitch is split in half to enable an attack down one side before being repeated down the opposite side. Multiple players can be at each station to enhance the intensity of the exercise.

All players are positioned as they would be during a positional attack in a 4-3-3. Player A represents a defensive midfielder with inverted full-backs on either side of him. Only one of these full-backs are involved per repetition. Players B and C are central midfielders in advanced positions with players F, G and H representing the front 3. Except for one full-back, all positions are involved in each attack.

In the first example of a possible phase of play to create a cut-back opportunity, player A plays a bounce pass with B to get the ball rolling. C then lays off to D, the right-back, who plays into F, the wide forward. The wide forward receives facing inside the pitch and takes an aggressive first touch before playing a through ball to his midfielder.

As the ball travels to the wide forward, the central midfielder should already be sprinting into the box to receive the next pass. The timing and speed of this run are vital in preventing the midfielder from being tracked in a game.

After feeding through C, player F can continue his run to provide a supporting or counter-pressing option at the edge of the box. The defensive midfielder should also squeeze up.

The ball-far wide forward, the central forward and the ball-far central midfielder should attack the box with specific areas to reach. The ball-far wide-forward and central forward should reach the edge of the six-yard box with one just inside the front post and the other at the back post. This allows them to drag defenders towards their own goal whilst still being a threat themselves should they receive the cut-back. If they were to drift wide of the goal, this would narrow their angle, giving them less chance of scoring.

The ball-far winger should start drifting inside as soon as it is clear the ball is going to be played down the opposite side. When the ball is played into the box, he should accelerate towards the 6-yard box. The central forward should move away from the ball before darting to the front area.

The ball-far central midfielder, the ideal target for the cut-back, drifts towards the box before sprinting to the penalty spot when the ball is ready to be delivered.

The second option above shows the ball being played into a deep, wide area before coming back out. The two forwards should make the same initial movements before moving back with the ball to remain “on-side”. Player B should drift away from the ball, on the blind side, before attacking the corner of the 6-yard box.

Defending players can gradually be introduced to increase the game-likeness of the exercise and allow the players to problem-solve real scenarios.

Conclusion

Cut-backs and crosses remain some of the best attacking options to create opportunities to score. The downside can be when teams are tempted to throw the ball in the box and hope for the best. This can result in many turnovers of possession without any threat to the opposing goal. It can also lead to dangerous counterattacks.

The opposition team’s defensive set-up has to be disrupted for intentional and repeatable success to be achieved from crosses and cut-backs. To do this, players must be coached in movements that move the opposition out of their defensive structure. Rehearsed patterns of play with specific areas of the box to attack greatly enhance the prospect of cut-backs and crosses resulting in a goal.

Comments