Sitting in the USSF B license (badge) course and working on a performance analysis project got me thinking… What are some common box-entry principles that lead to quality goal-scoring opportunities?

And that’s where this tactical analysis was born.

Our objective in this tactical theory article is to identify some of the best box entries from the weekend, each of which led to a goal.

In each case, the attacking sequence ended with a goal from a high-quality scoring opportunity. Those are the box entry ideas we want to decipher and replicate in our own environments.

Overload to enter the box

Let’s start on the wings.

When facing a highly organised defence, box entries seem like little more than a crap shoot. Opponents will tend to have numbers up centrally to defend against crosses, cover for the first defender and a balanced structure that gives them a positional superiority.

For the attacking team, the prerequisite for a quality box entry destabilises the opponent. There’s a need to move their lines and disconnect their defensive network. The in-possession team has to create the space they want to attack.

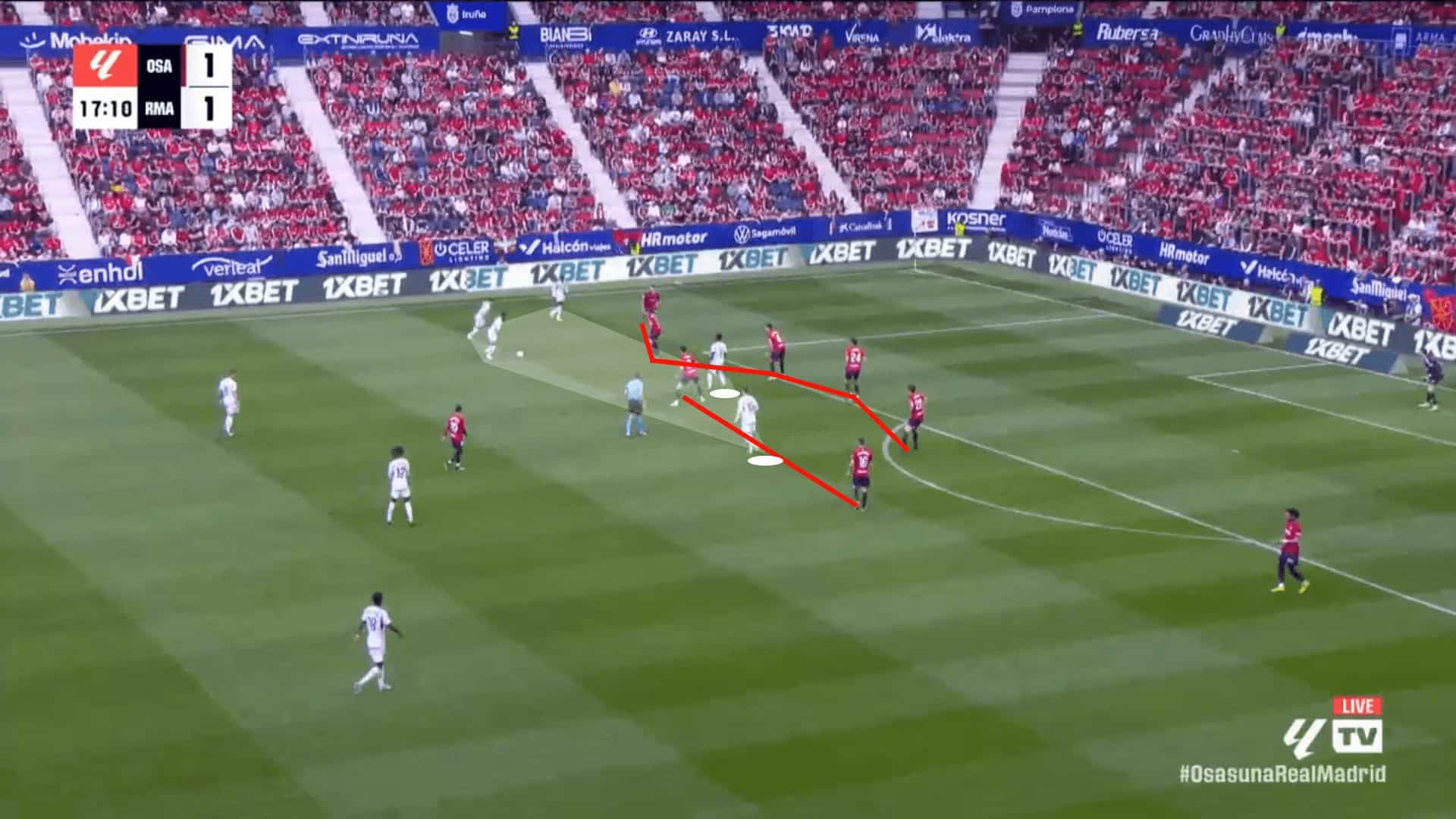

One way to disorganise the defending team is to use a numeric overload in the wings, which Real Madrid used for their second goal over the weekend. Their opponents, Osasuna, held an advantage centrally, so Real Madrid went to work in the wings. In the image below, notice the structure of this Osasuna side. To counter their defensive tactics, Real Madrid overloaded in the wings. In doing so, they posed a threat to progress into the box from either the left wing or left half-space. That required their opponents to slide away from the middle and nearer to the ball.

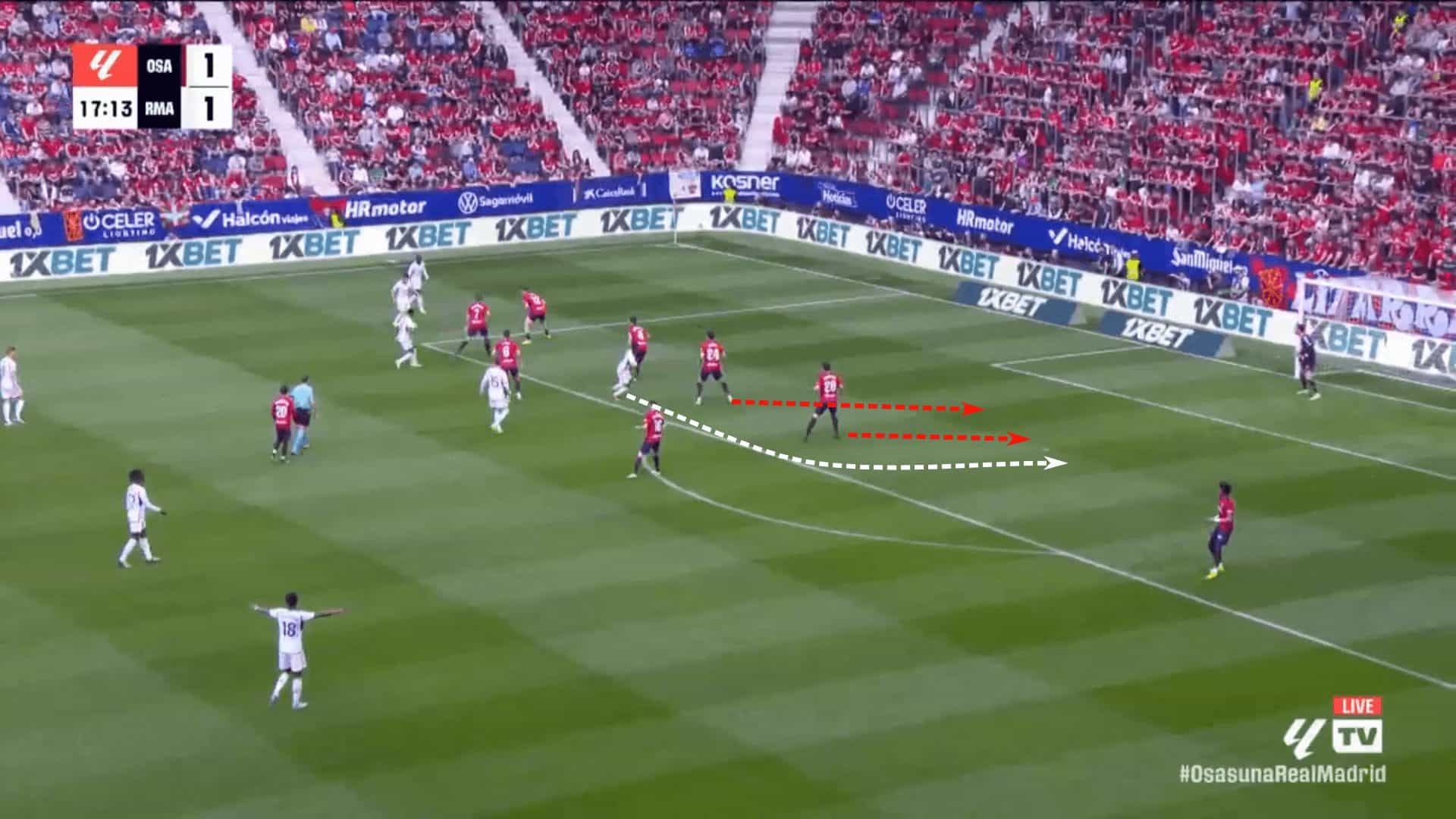

La Liga’s leaders drew the opponents near to the ball and then offered a sequence of runs behind the backline. It all started with Vinícius Júnior. Initially, right in the midst of the press, as the opposition compacted the space, the Brazilian made a horizontal run to the centre of the pitch and initiated his movement towards goal. In doing so, he took two defenders with him. Osasuna was happy to comply and keep their plus one in the goal zone.

His movement started the sequence of events. As the central defenders backtrack towards goal, space opens up for Fede Valverde to run into. Courtesy of Vinícius Júnior’s run, Valverde was able to run into the box between the backtracking central players and stay on the blind side of the four players near the ball.

The pass was flicked over the group of four, leading to Valverde’s assist of Dani Carvajal’s goal. The coordinated movements of Vinícius Júnior and Valverde were vital for Real Madrid’s box entry. As the high player who was drawing the opposition’s attention, the Brazilian’s central movement was seen by the deeper player, Valverde, cueing him to attack the space Vini had cleared. That cooperation of the high and low players to disconnect the opposition’s backline proved lethal.

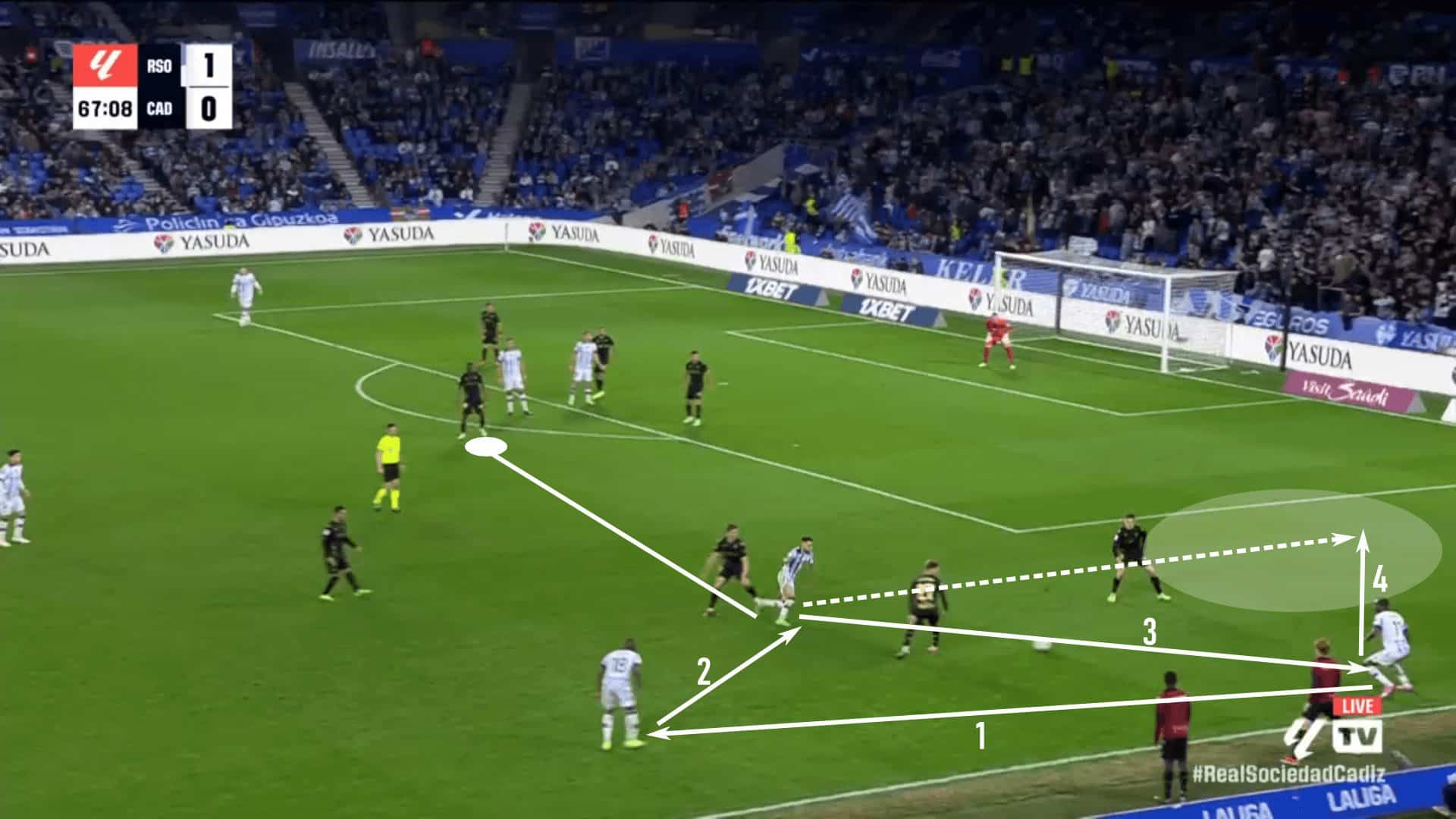

Staying in La Liga, we have another example of a wide overload leading to a goal in the Real Sociedad vs Cadiz matchup. This one starts 2v3. Real Sociedad has numbers centrally and is prepared for a quick cross, but they opt for a different route. Brais Méndez leaves the central channel, quickly checking to the ball to create a 3v3. A quick four-pass sequence gets him behind the three Cadiz defenders and gets him just into the box.

The wide overload producing a box entry is the focal point here, but it’s worth noting the complementary movements. They are part of the box entry. As Méndez prepares his delivery, Real Sociedad executes their central runs to perfection. Méndez’s movement draws the nearest central defender out, giving the home side an open near-post runner. There’s also the deeper player to attack the penalty spot and the far player who’s prepared for a lofted cross to the second post or a hard-driven delivery on the ground.

It’s that second option, the low-driven ball, that makes its way across the goal for an easy tap-in at the far post.

This is a fantastic example from a few angles. First, the wide overload gets Real Sociedad into an excellent space for the delivery. Second, because they were able to get behind the three wide defenders, they forced a defender to leave the central channel to defend the delivery. Finally, the runs into the box were straight off the training ground. Excellent movements, final position and timing from the three runners left Cadiz in shambles.

Well-executed wide overloads unbalance the opposition away from goal, leaving more space for the runners to attack. If those wide overloads managed to get the server behind the ball near defenders, that wide overload will likely pull another player from the goal zone. Both Real Madrid and Real Sociedad found success through them over the weekend.

Combining Centrally

The last section was exclusively Spanish. In section two, we’ll turn our attention to the Bundesliga. With the change of league, we’ll also shift our attention from the wings to the centre of the pitch. There’s an element of that numeric overload, but we’ll look at two examples for a more comprehensive look at box entries through the central channel.

When entering the box through the centre of the pitch, combination play is the standard route forward. The opposition will typically have numbers. Advantage and space are typically too tight for 1v1 duels, so dribbling has to take another focus. When moving towards the box from the centre of the pitch, the dribble isn’t designed for a duel. Rather, it is to give the impression of a 1v1 engagement. The end goal is to initiate through the dribble to pull an opponent higher up the pitch to create space to run behind him.

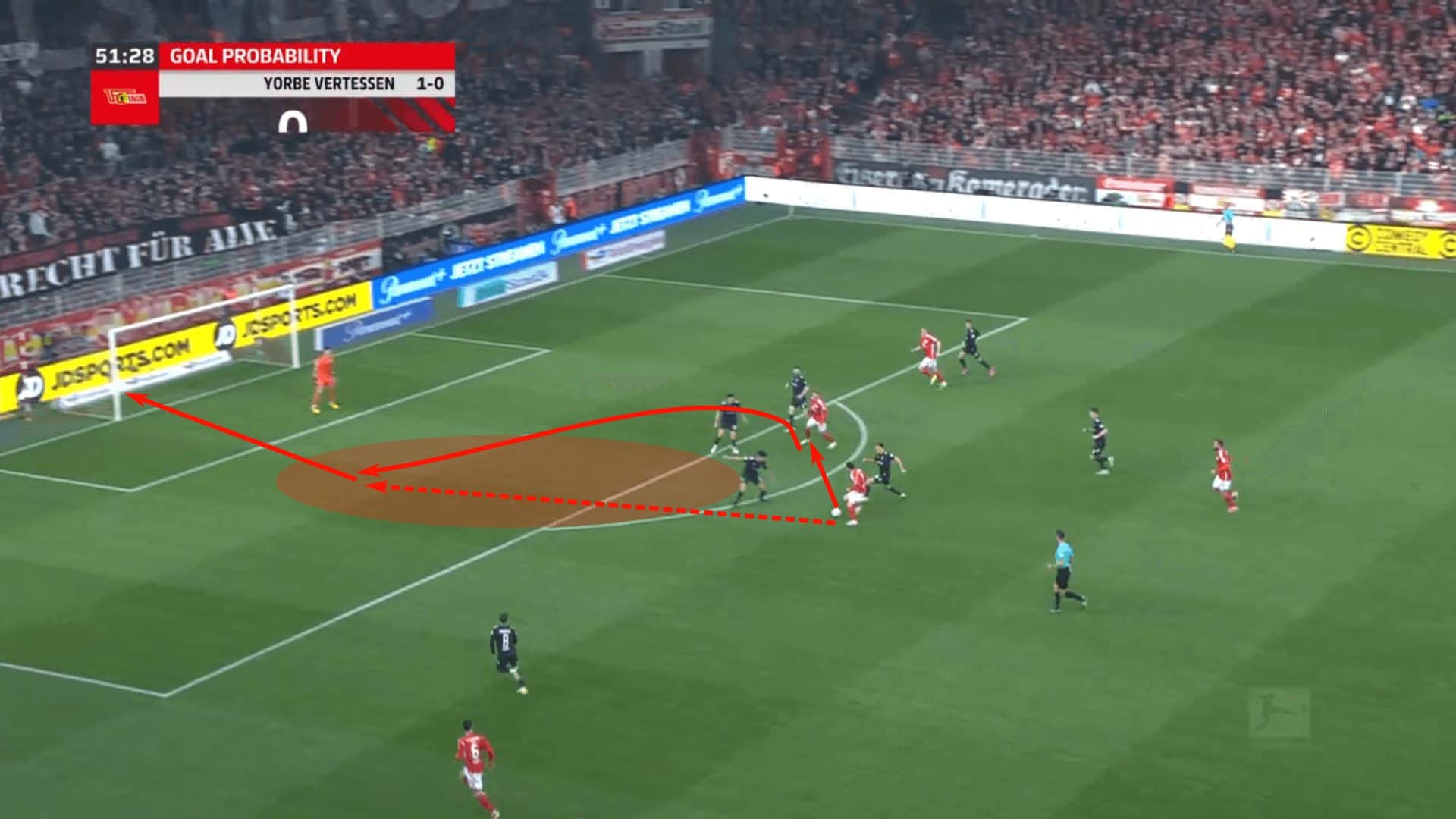

That’s precisely what we have with our first example, featuring Brenden Aaronson’s goal for Union Berlin. This attacking sequence starts a little bit deeper, with Aaronson bouncing off his opponent to put himself in the position below.

As he approached the box, he targeted the right centre-back, appearing to engage in a 1v1 duel. Given that threat, the centre-back, Miloš Veljković, was forced to slide to his right to offer coverage. With Julián Malatini pinned, Aaronson played a give-and-go with Yorbe Vertessen to get behind the backline and provide the eventual game-winner.

One thing to note in that sequence is the positioning of Vertessen. Knowing that Aaronson has space to run into, the Belgian intelligently holds his positioning a couple of yards in front of the Werder Bremen backline and splits the difference between the two remaining centre-backs. His positioning not only connected him to Aaronson for the give-and-go, but it also created more space for Aaronson to run into. Instead of moving into that shaded space, Veljković moved towards Vertessen. By stepping forward, his momentum carried him away from the space Union Berlin wanted to attack. One wrong step, and he found himself out of the play.

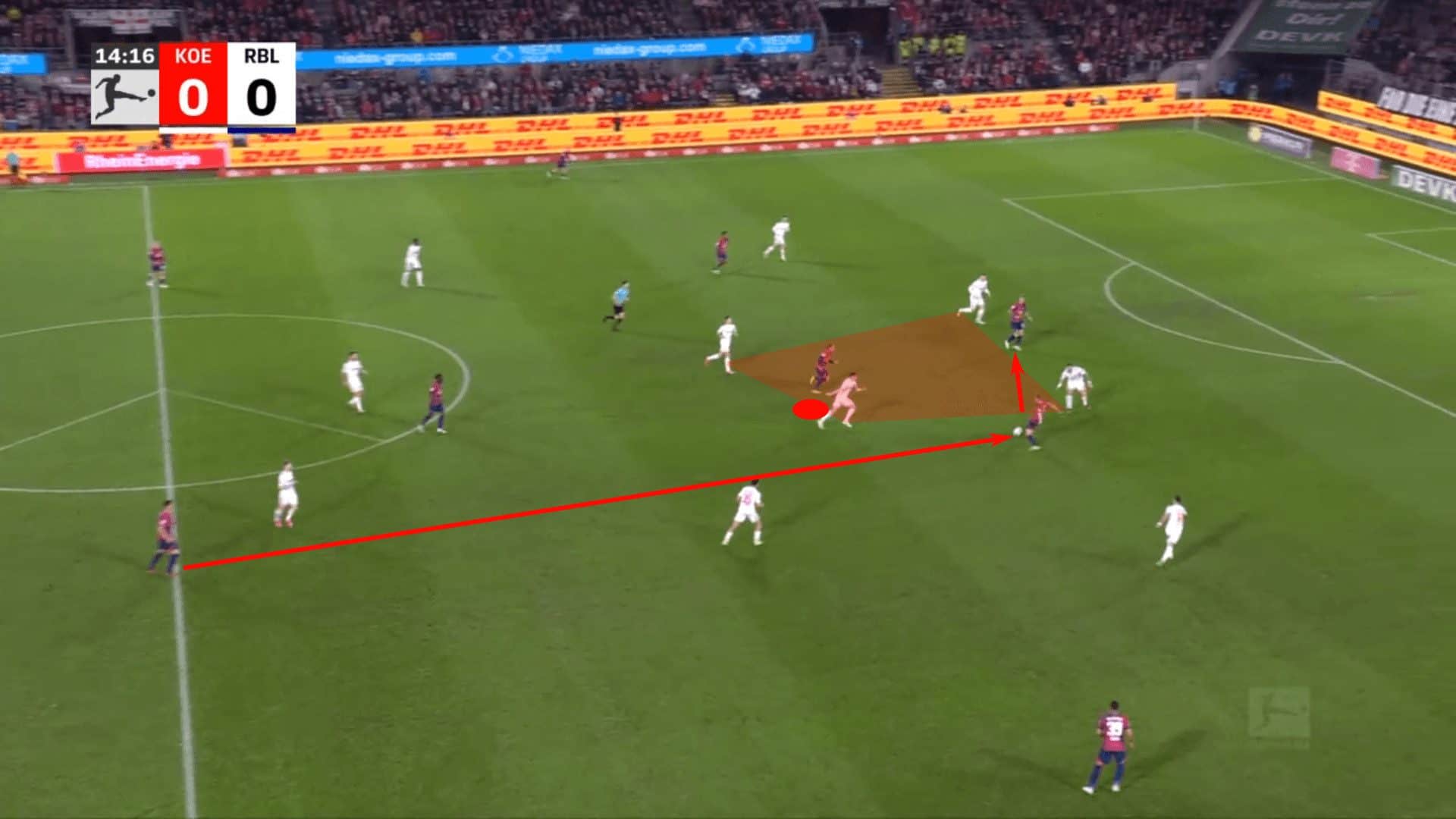

Elsewhere in the Bundesliga, Xavi Simons was having himself a day with RB Leipzig. High central overloads were crucial to his two goals.

Building up to the first goal, it was a brilliant line-breaking pass from Willi Orbán that found the foot of Dani Olmo. Right away, we can see that RB Leipzig has 2v2 high and centrally with Simons underneath in support. His movement is untracked, giving the away side a 3v2 advantage in Zone 14.

Olmo’s clever pass was set by Benjamin Šeško into the path of Simons. The former Barcelona and PSG prodigy used a heavy touch to push the ball beyond the backline and into the box. That set up a 1v1 against the goalkeeper and an easy finish for the 1-0 advantage.

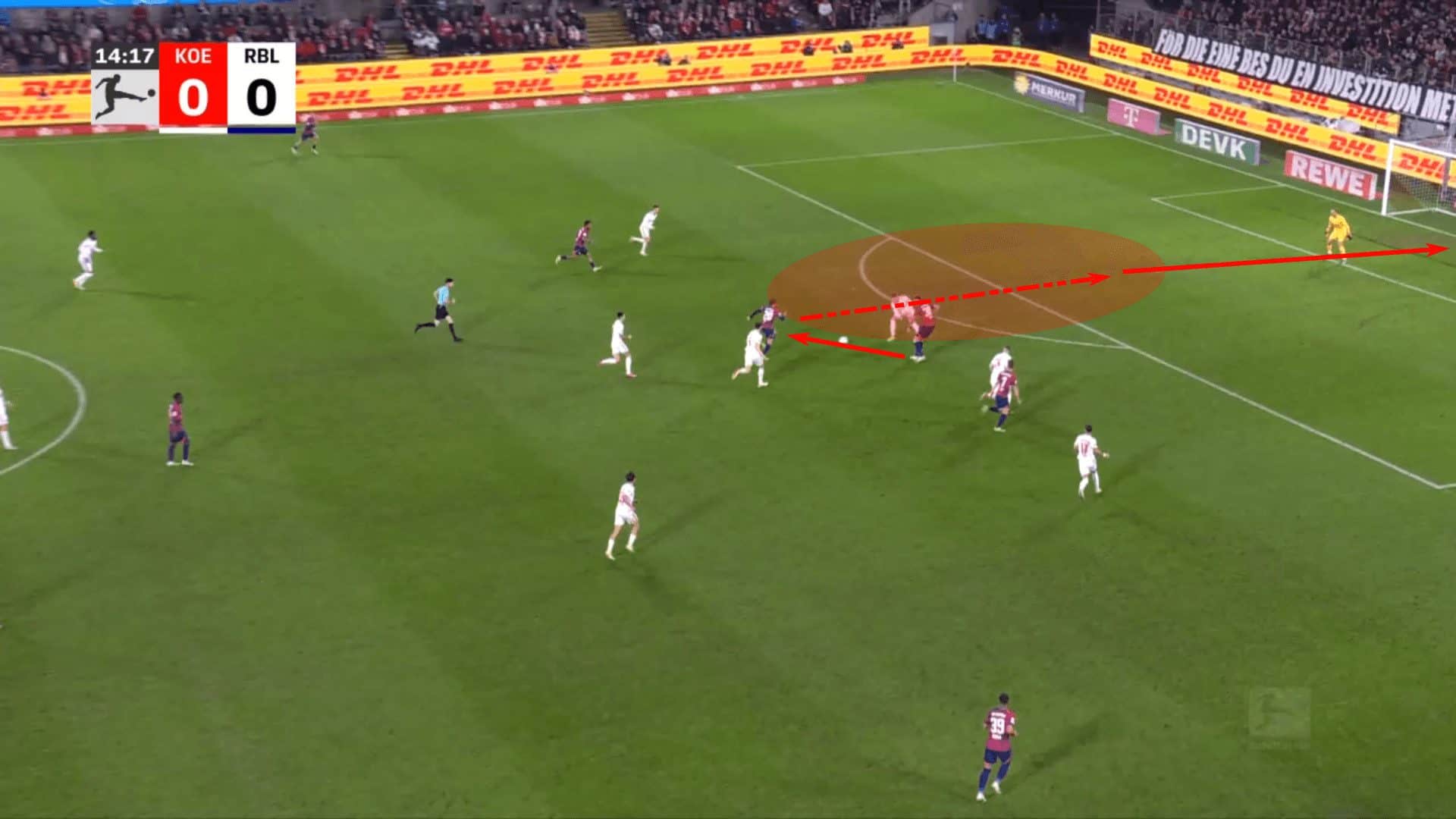

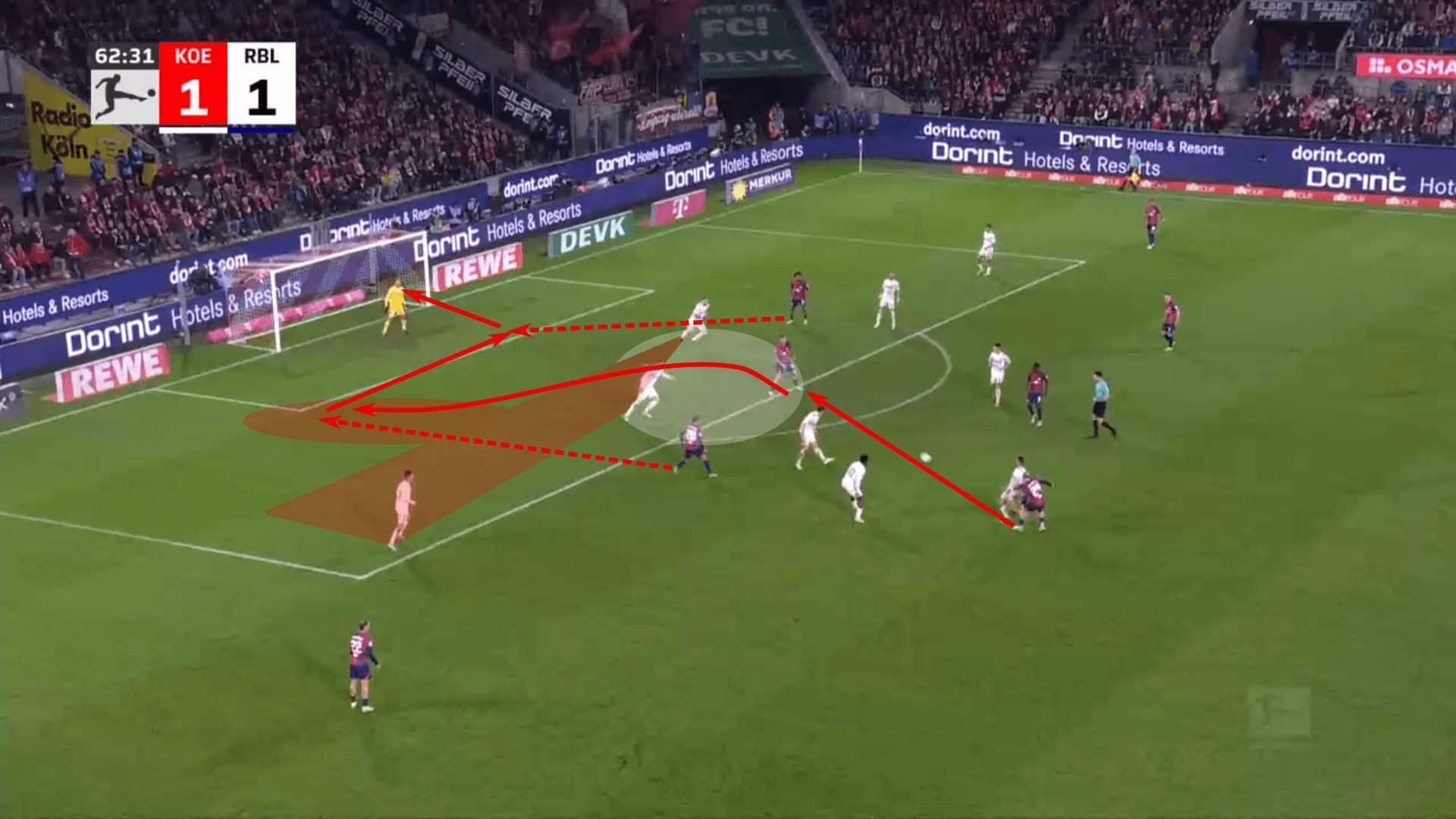

Simons would help break the deadlock again midway through the second half. Again, it’s combination play through a high central overload that does the trick. Simons is the third man, latching onto the pass and squaring it for Ikoma-Loïs Openda’s game-winner.

Looking at the image, RB Leipzig managed to disconnect the Köln backline by getting Julian Chabot to drop behind his teammates. As he dropped, Šeško would fill the space he left and play Simons into the box. The two RB Leipzig players created a 2v1 against Luca Kilian, getting him to respond to the first pass. That left Simons, the third runner, free to make his run into the box. Not only does RB Leipzig push numbers high and centrally, but they managed to create a 2v1 in a compact area. That numeric advantage and quick combination play helped them carve apart the Köln low block.

Playing behind the line

While there’s already an element of playing behind the line in each of the first two sections, there were some excellent examples of attackers in the highest line finding a way to get behind the defence. It’s those cases that we want to break down as we examine different ways of attacking the box.

We have two examples in this section. The first features an organised defence in a low block. The second offers a transitional moment, though one where the opponent is well-organized and looks prepared to defend.

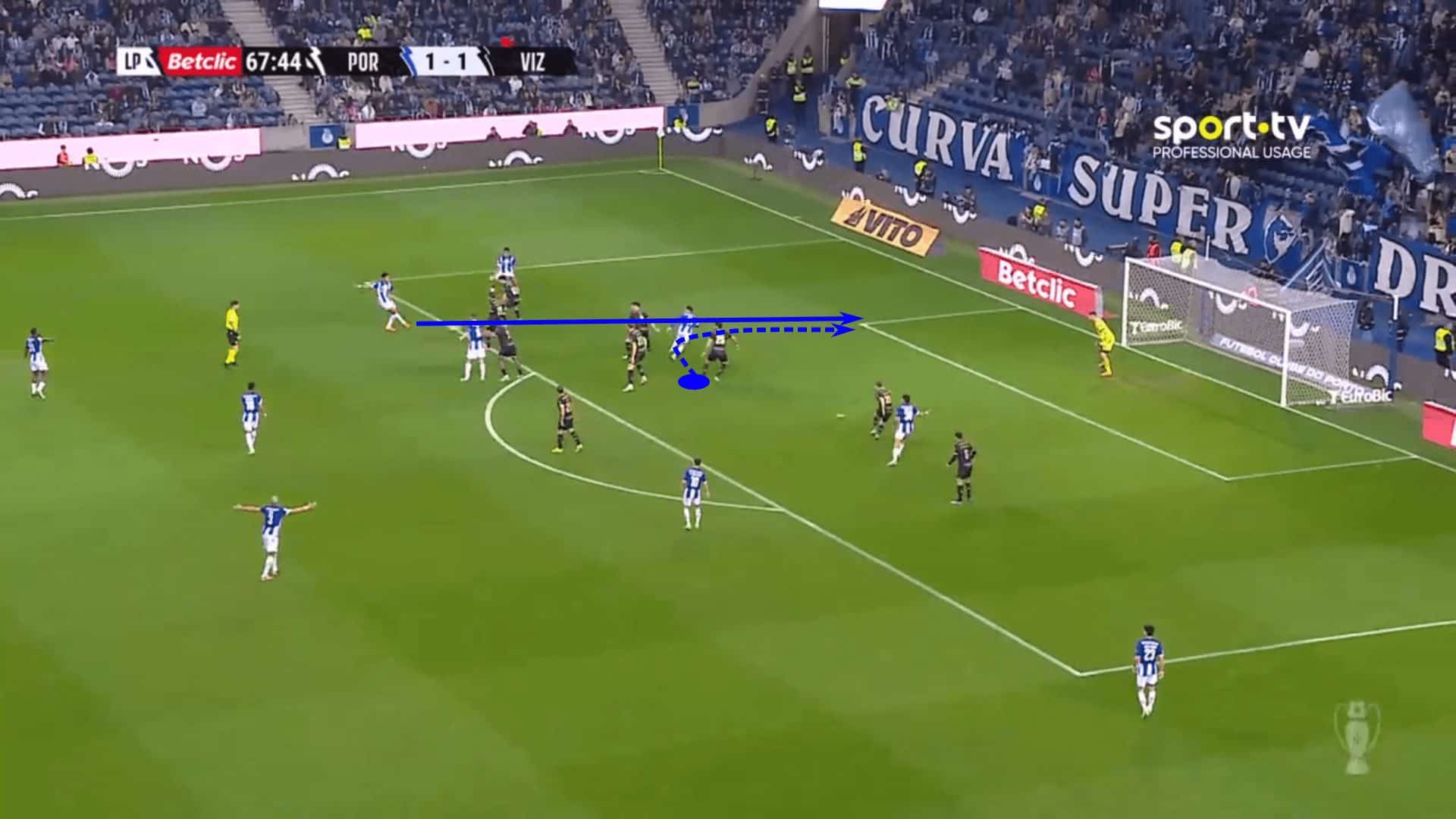

In that first example, we head to Portugal’s Primeira Liga, where Porto was taking on Vizela. Looking at the first image, the away side is well-organized and has numbers behind the ball. Porto doesn’t like that look, so they changed the picture. By moving deeper and more central, they can face forward and reevaluate how to attack the backline.

Once Danny Namaso comes central, he notices Pepê Aquino subtly moving along the backline. As Namaso faces forward, a couple of teammates check to him while another offers an option at the far post. Those two movements force numbers near the ball and deeper in the box. That’s exactly the moment Pepê Aquino is looking for. He offers a horizontal run, then latches on to the through pass before scoring.

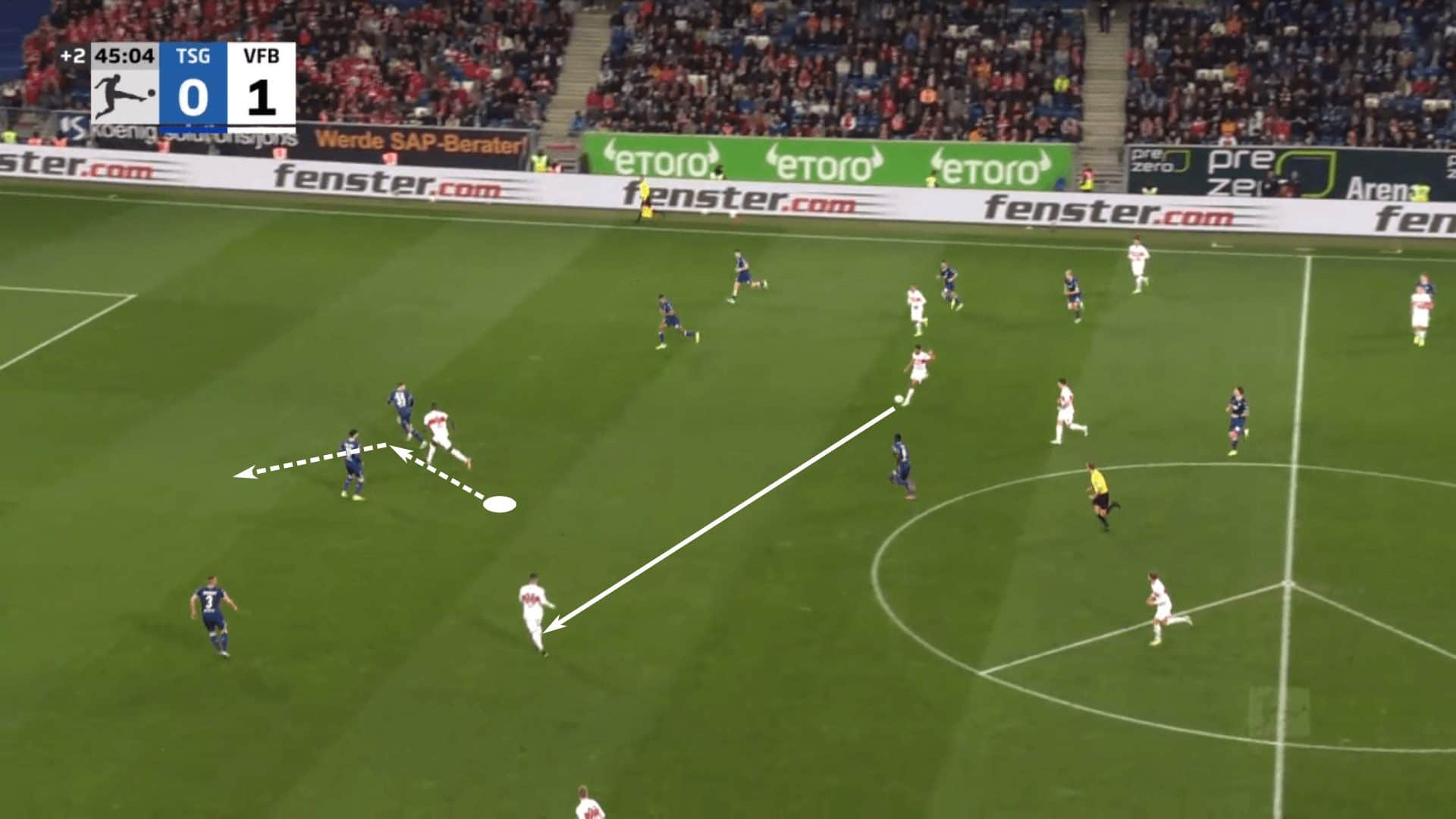

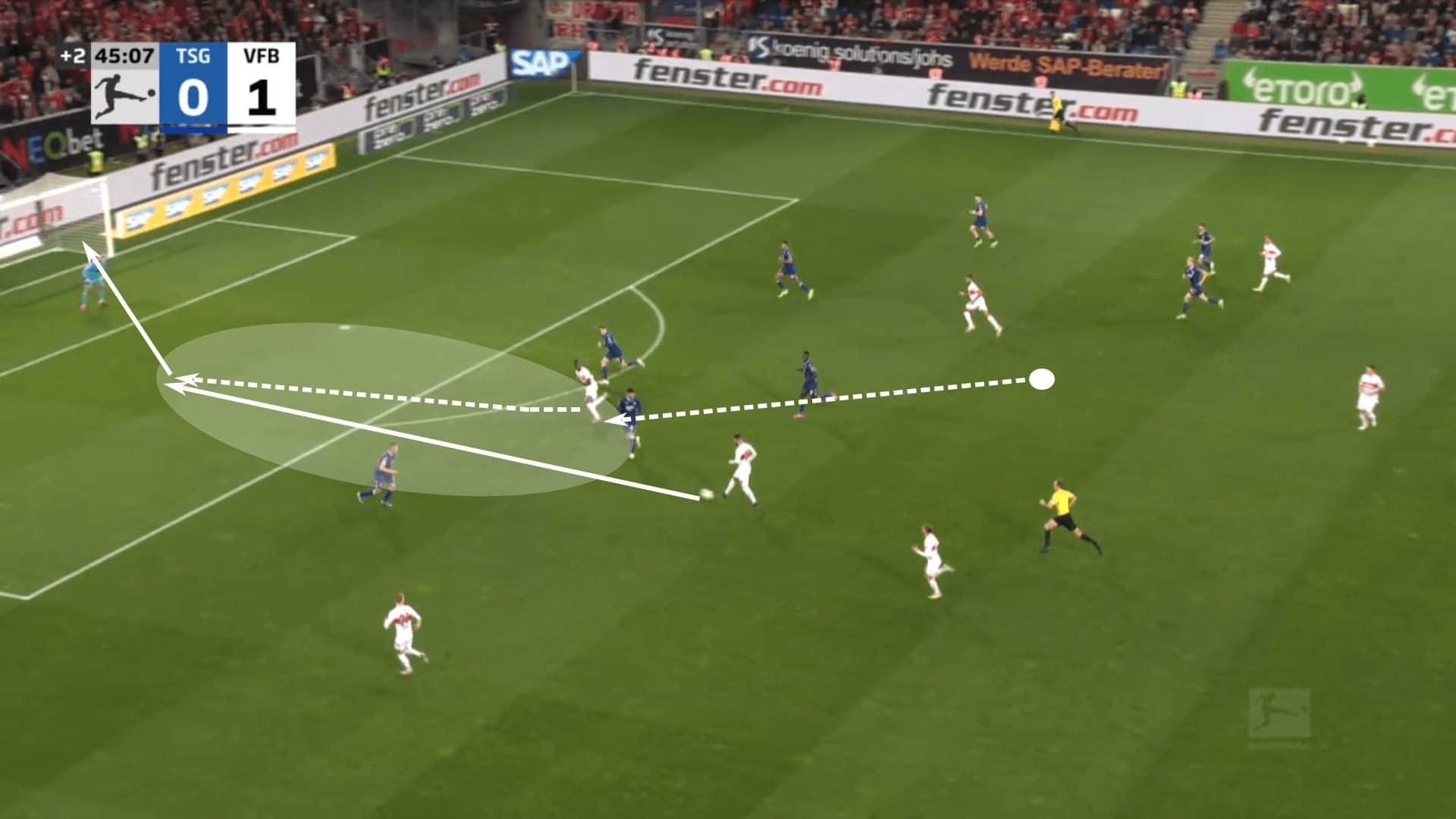

That’s our example from a set position. This next one from Stuttgart shows a Hoffenheim team in transition and recovering to goal. While they have numbers deep, the defending team has a large gap in midfield. Stuttgart takes advantage of their disorganisation by finding Deniz Undav centrally. As he receives, he notices the run of Serhou Guirassy. Initially, Undav offers a run behind the back three into the right half-space. Once the switch is played, he works to disconnect the left centre-back from the centre-back, then bursts into the space between them.

As Undav carries the ball forward, he pins the centre-back, Florian Grillitsch, drawing him forward. Once the centre-back moves forward, Guirassy has a few yards to run behind him. He latches onto the through ball and finishes.

In this transitional moment, much like we saw with the goal Aaronson scored in section two, the key is pulling a centre-back forward. Once he leaves the backline, he leaves a space for an attacker to run into. Stuttgart ran at Grillitsch early, creating space for Guirassy to run into.

The first defender left behind was critical to this attacking sequence. It differs from the Porto example in that the defenders were coaxed forward in different manners. For Porto, getting numbers near the ball was the bait to create an additional three yards of space to run into. Vizela was already sitting deep, so the attacking action was designed to pull them forward.

For Stuttgart, the backline is already retreating, so all they need is one player to abandon the retreat and step forward to apply pressure. In either case, the objective is creating space to play behind the backline. The runners were already in high positions, so the actions preceding the final pass had to maximise the space the second attacker could run into.

Conclusion

This article was born from an analysis project. That dedicated time to tagging film and tracking KPIs produced a moment of curiosity that served as the basis for this article.

And that’s how many analysis projects start. Some curiosity sparks a train of thought and leads to dedicated research time. Fortunately, there were several excellent examples to work with from this week’s games.

The beauty of this kind of tactical analysis is that it’s easy to apply within our own environments. Reducing these actions to principles of play helps us relate these sequences to our game model. You may notice the first section was entirely Spanish, the second entirely German, and the third a mix of Portuguese and German. The principles covered in this tactical theory article are diverse, with coaching points to fit any game model.

Taking the principles that best fit one’s own game model, coaches can then work backwards to recreate the scenarios in their training environments. The game is our starting point, and our training sessions follow from repeated moments and patterns.

Whether working in a coaching badge course or simply studying film, that quiet time for observation and reflection can be wildly productive. Just follow curiosity.

Comments