Set plays have always been critical to the outcome of football matches. However, they have been assigned even greater importance by clubs in recent years. It is now commonplace for top-level clubs to have set-play-specific analysts and/or coaches. These are positions that did not even exist just a few years ago.

Brentford were one of the pioneering clubs in the Premier League in their approach to set plays and the importance they attributed to them. This approach has paid off over the club’s three seasons in the Premier League, having been promoted from the Championship in 2021. Brentford are consistently amongst the most dangerous teams from set-pieces.

This tactical theory focuses on Brentford’s attacking corner kicks and analyses several of the tactical traits involved in Brentford’s corners. This tactical analysis explores how Brentford use different set-ups but have similar traits and tactics for each corner kick. Furthermore, our tactical analysis includes sample training exercises that coaches can use to improve efficiency at corner kicks.

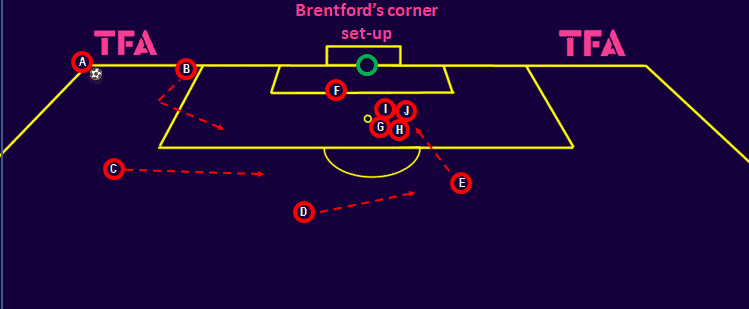

Brentford’s corner set-up

The above tactical diagram shows Brantford’s typical set-up for attacking corners. Although the exact positioning of players changes every game, and sometimes per corner, there are common trends.

One consistent trait is that all outfield players are involved in the attack, with the goalkeeper in the centre-circle in his own half. When the opposition leave a player high (rare in the Premier League), Brentford has dropped a player back and gone one-on-one.

Typically, one player (shown as “B”) will be almost in-line with the ball on the side of the box, appearing as an option to receive the ball. Player C also shows towards the ball around the corner of the box.

The primary objective of these two players’ positioning appears to be to attract two defending players out of the box. As soon as the ball is crossed, or as it is about to be crossed, these two players position themselves for the second ball.

Player C moves more centrally, with player B’s positioning concerning the expected delivery type. Based on Brentford’s first corner Vs Nottingham Forrest, this example shows that the ball was delivered to the front area. Player B positioned himself in the most likely place the ball would end up if the first zonal defender won first contact.

Players D and E also cover the edge of the box, with player E often making a late run into the box. The space for his runs into the box are created by G,H,I, and J, who make runs to attack the six-yard box. These four players’ starting positions and movements can differ significantly from game to game. Player F screens the opposition’s first zonally positioned defender.

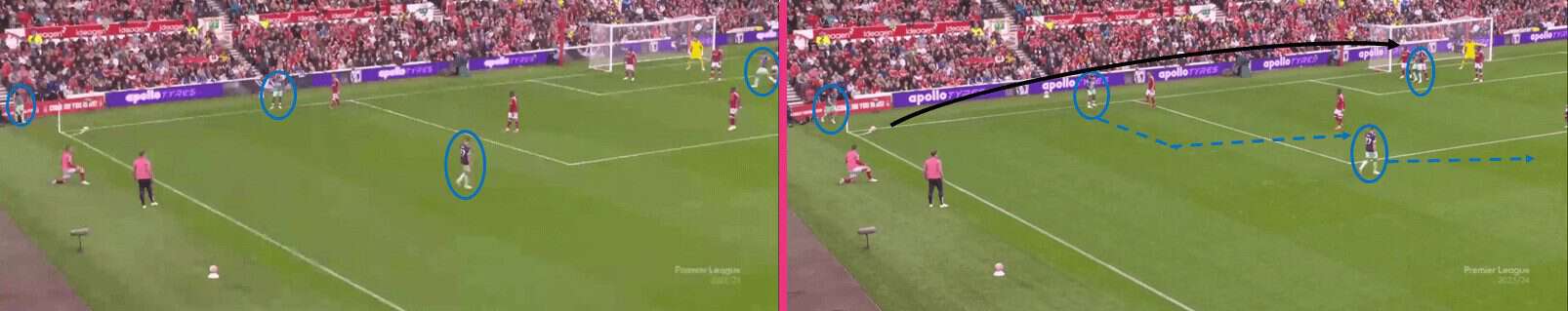

Late movements

The above image shows this setup in action against Nottingham Forrest. Just before the corner taker delivered the ball, Brentford changed the positioning of the players in the box. In this example, the key player (circled in the box) moves to a position to block or screen Forrest’s first zonally positioned player.

This brings two defending players to the same spot, resulting in less of the box being covered. The last-minute timing of the position change makes it hard for the zonal player to adjust to give himself a better chance of attacking the ball.

The zonally positioned player has gone from being completely free to having an opposition player and a teammate blocking his path to attack the cross. With more time to react, his teammate may have been able to mark the Brentford attacker whilst simultaneously clearing the way for his zonal defender.

The players near the ball also move, just as the ball is struck, to take up favourable positions for the second phase.

The above images show another late set-up change against Newcastle. The positioning slightly differs from their typical set-up, with no one near the ball. Initially, Brentford crowded the far half of the goal area with seven players. In the seconds immediately before the ball was crossed, all these players made movements away from the goal. These players then completed a second movement to either attack the ball or the back area of the goal.

The last-second change makes it hard to read what Brentford have planned and disrupts the opposition’s defensive set-up, giving them no time to adjust. Newcastle’s marking players were outnumbered when accounting for their zonally positioned players. With all the attacking players making a sudden burst away from the goal, Newcastle did not know which players to follow.

These movements dragged defending players away from the goal and left the back half of the goal completely devoid of defenders. Half of the Brentford players remaining in the box attacked the ball at the front area, with the apparent aim of flicking the ball on towards the back post. Two attackers made a double movement to attack the now empty back half of the goal area. Their makers found themselves having to scramble to backtrack towards their own goal.

Had Brentford’s set up like this initially, Newcastle’s players would have positioned themselves more easily to cover their man and the space. Several Brentford players found far more space than expected from a corner. Their movements away from the goal make it harder to be marked, as the defender cannot block the path of their run.

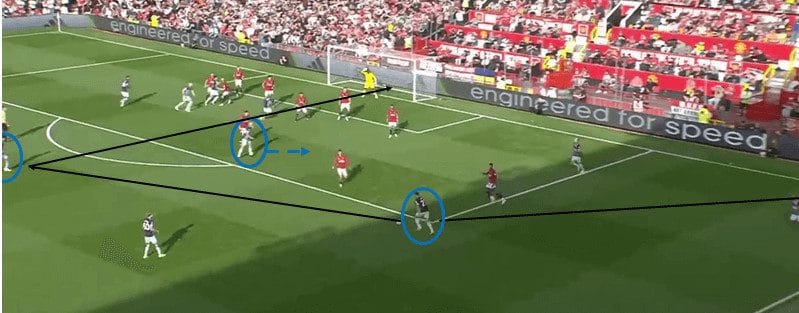

Variation

Brentford have many variations to their corner kick routines. This recent one, against Manchester United, was a short corner. The routine was designed to create a shooting opportunity at the edge of the box for Aaron Hickey. The players were positioned similarly to the previously tactical diagram.

The ball was played short, almost to the corner of the box. The players grouped in the box created a distraction by moving as if to get on the end of a potential cross. One of the players, usually assigned a position deeper inside the box, was positioned closer to the edge. His positioning and slight movement to show for the ball distracts and moves the sole United player in a position to press Hickey.

Hickey, initially positioned at the edge of the box, backtracked away from the goal. This allowed him to remain unmarked, as he was not an obvious danger. It also allowed him to step onto the ball when he received it.

As the ball was played across towards Hickey, the Brentford players in the box screened their markers. This was to prevent United’s players from pushing up to block Hickey’s shot. It also kept the defenders in deeper areas than they would have liked. Without being able to clear their box, any ricochet off them could have deflected into the net.

The details in the planning of this corner, however slight and simple they may appear, were enough that Manchester United fell for the movements twice in succession.

Coaching movement in the box

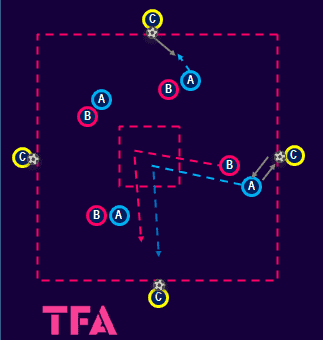

The following exercises are designed to help players develop the skills and movements required on the receiving end of a corner. These movements will aid them in implementing set-play routines, as analyzed above.

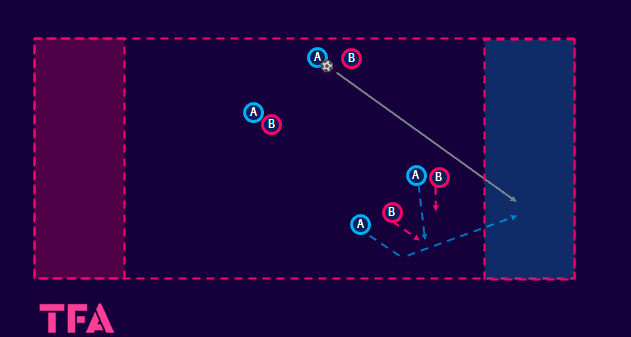

This introductory exercise, which can be implemented as part of the warm-up, is designed to work on players evading their markers precisely so they can break free in the box to attack crossed-corner deliveries.

The group is split into three teams. One team, with footballs in hand, is distributed outside a square or rectangle. Players from the two remaining teams pair up with a player from the opposite team. The aim for attacking players, shown in blue above, is to receive a thrown pass from as many of the yellow players as quickly as possible.

The attackers must catch the pass and throw the ball back to the same yellow. The aim of the defending players, shown as pink, is to mark their opponent as tightly as possible. They must either intercept the pass or “tag” the attacking player when the ball is in their hands. If either is achieved, the roles switch, and the attacking player has to quickly transition to being the marker. Players count how many throws they receive and compete with their direct opponent.

Players aim to create enough separation from their markers that the ball is safe and they are not in touching distance of the defending player. To encourage good, game-like movements, the receiving players must run through the central box before receiving their next ball. This exercise can be progressed to players using their heads or feet to receive the ball.

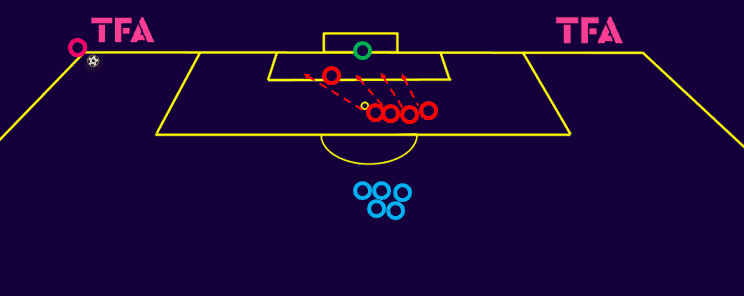

The second exercise leads on from the introductory exercise and is a competitive game of handball. Teams are split evenly, with players given a specific opposition player to mark. To score a goal, the ball must be received in the team’s “end-zone”.

The ball holder is not allowed to move. This increases the importance of the off-the-ball movement. As with the first exercise, players should be encouraged to create separation from their marker through sharp movements. Screens or blocks (as shown above) should be performed to enable teammates to receive the ball alone. Aggression and a desire to break away from their marker, just as with corners, are paramount in this activity.

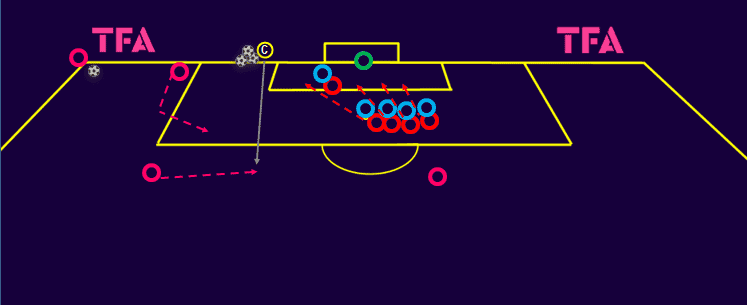

The two initial exercises can lead to an unopposed practice of set corner routines. Two groups can be formed, working one group at a time, with a designated corner taker (or takers). The first group sets up as determined by the coach and attacks a cross.

A second group, shown in blue, is then ready to set up quickly for the next cross. All players should be encouraged to get to their starting positions quickly to practice, giving the theoretical opposition as little time as possible to set up.

The exercise set-up allows players to practice their positioning, the timing of their movements, and finishing whilst completing several repetitions in a short amount of time. Just as with Brentford, the players can be set up in one way before making a last-second change before the ball is delivered.

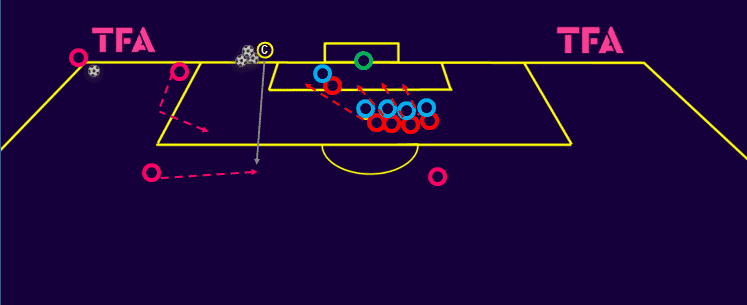

The last part of the practice session is an opposed or semi-opposed live corner. Neutral players, who always play for the attacking team, can be positioned where desired around the edge of the box. Two teams inside the box can take turns attacking the goal or defending.

The coach can create corners where a second phase does not organically occur. After the initial play, a second ball can be fed to a player on the edge of the box. Players in the box can then work on movements during the second phase of corners. This could include moving away from the ball to receive a back post cross or blocking defenders to allow a shot at goal.

Conclusion

With increased set-play analysis and set-play-specific roles within clubs, corner kicks are an ever-evolving part of the game. Brentford have been at the pinnacle of this over the previous several years. The infrastructure they have built behind the scenes to support their set-plays has been rewarded in goals and their comfortable position within the division.

Corner kicks will remain an essential part of deciding the outcomes of games. Coaches must prepare their teams as well as possible for these situations and analyze and work on corners on the training ground. The work on the practice field needs to be done as engaging as possible to keep players interested.

Comments