“The main — and most important (aspect of the build-out) — is to produce a better quality of service into front players.” Stewart Robson in an ESPN analysis on why teams build out.

Think of service as attacking opportunities.

Playing out of the back isn’t simply a means of keeping the ball for its own sake or building play through a seemingly endless sequence of short passes.

The build-out aims to create better attacking conditions higher up the pitch.

In this tactical theory piece, we’ll not only cover how to coach build-outs… we’ll also design our exercises from principles of play. The idea is that starting with principles of play will lead to better session development and clearer coaching points that are more broadly applicable than scripted patterns. We want to build game intelligence by showing our players which objectives we are trying to accomplish and teaching them how to construct play for various variables. This analysis will relate the ideas to tactics, including extending the opposition’s lines vertically and the art of overloads to unbalance the opposition. Finally, we’ll discuss the principle of control.

Extending the lines vertically to create artificial transitions

Let’s start with the build-out objective that’s most prominent right now: extending the opposition’s lines vertically to manufacture artificial transitions. The fundamental principles here are baiting the opposition to become unbalanced high up the pitch, disconnecting the midfield and defensive lines and creating an intermediate or long passing option into the forward line. That pass into the forward line offers a high degree of variability. Whether that’s playing centrally to a checking #9, a long diagonal into the wingers, an intermediate-range pass to the #10 between the lines or a ball over the top, this build-out draws the opposition high up the pitch to create better attacking conditions for the highest players in the system.

In order to draw the opposition high up the pitch, the in-possession team must offer an enticing prize. Take the ball from us in your final third and attack the goal with limited opposition. Dangle the bait that the opposition deems worthy of taking. What the defending team assesses as a high degree of risk, the attacking team must see as a means of manipulating the opposition’s lines to create a vertical imbalance. That’s what cues opportunities to play forward.

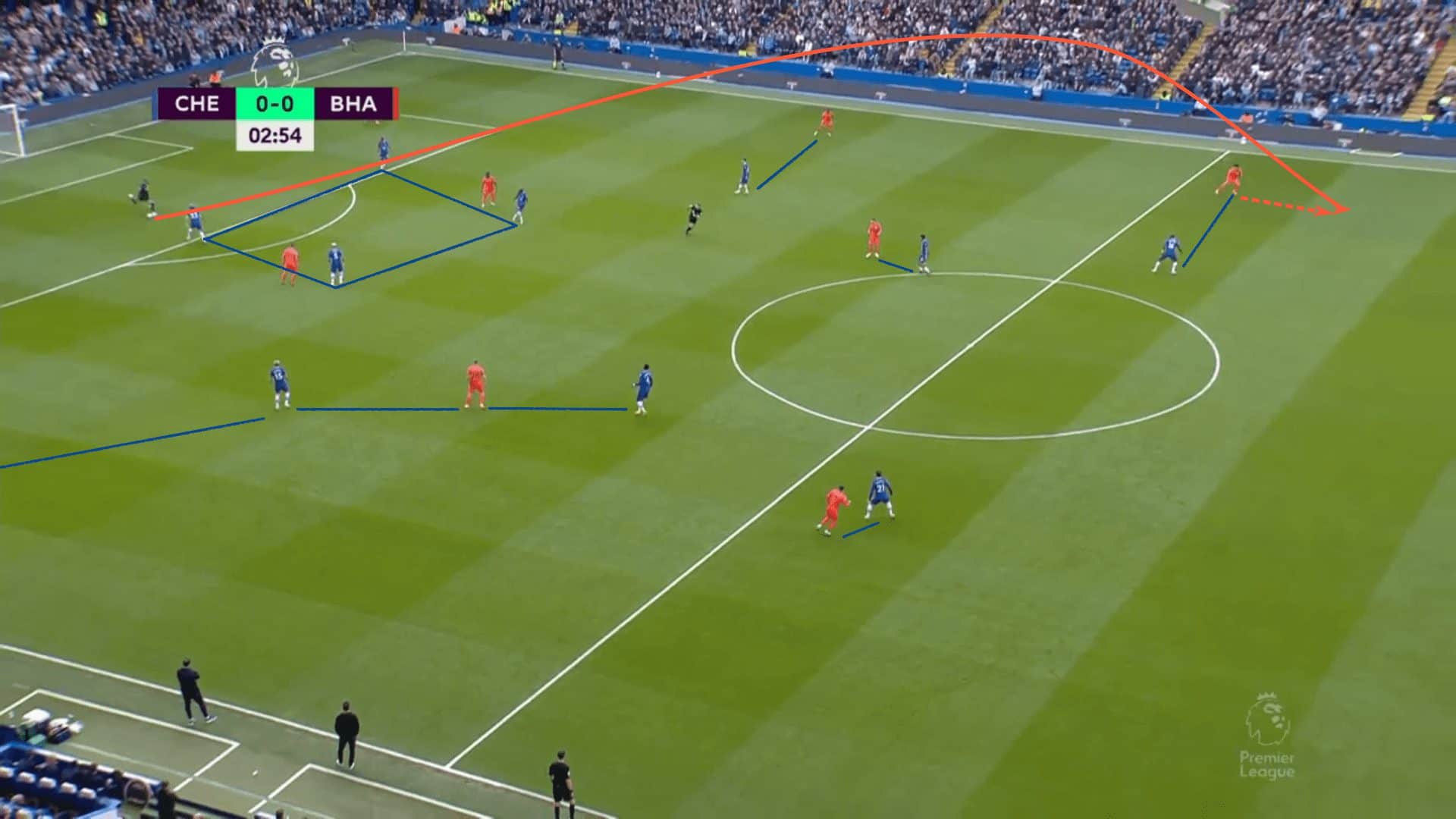

Perhaps no team in the world does this better than Roberto De Zerbi’s Brighton. To entice opponents to commit numbers forward, Brighton appears to take a great deal of risk at the back. But this assessment of risk is in the eye of the beholder. For a team that’s well drilled in keeping the ball at the back and has a clear understanding of when to play forward, who to target and how to best deliver those press-breaking passes, the risk is minimal and the reward maximal.

In the early stages of build-outs that are designed to unbalance the opposition’s lines vertically, a strong rest defence structure is a necessity. Aim for the best outcomes, but prepare for the worst. Positioning of the players at the back is of supreme importance. They must be prepared for a loss of possession and a quick recovery in defensive transition. This is where Brighton’s central square between the two centre-backs and double pivot gives them security against a deep loss.

One other note on that image above is the positioning of the remaining six players to determine where the ball is going next. The outside-backs take up wide positions to stretch the opposition’s lines along the x-axis. The central attacking midfielder, right-forward and centre-forward all take up more central positions to manipulate the shape of the backline. Brighton has overrun the EPL with their ability to connect centrally between the lines, leading to artificial transitions with the first attacker running at the backline.

But what about Kaoru Mitoma, the team’s best dribbler, on the left wing? He’s now in a position to receive and run at his mark or offer a run behind the backline. He’s well-positioned to use his qualitative superiority against the opposition. Add in the fact that he typically positions himself outside the opponent’s line of vision and is a tough player to track. In this instance, he receives the pass and engages in a 1v1 duel, giving Brighton their final third entry.

That was one form of disconnecting lines vertically to generate artificial transitions. The more classic form is playing into a target forward and setting the ball back into oncoming midfielders. The key here is using the build-out to compress the lines, signalling the midfielders and even the wide forwards to take up support positions underneath the target. If the attacking team can claim the second ball, they have numbers between the lines and can increase the attacking tempo, running at the backline.

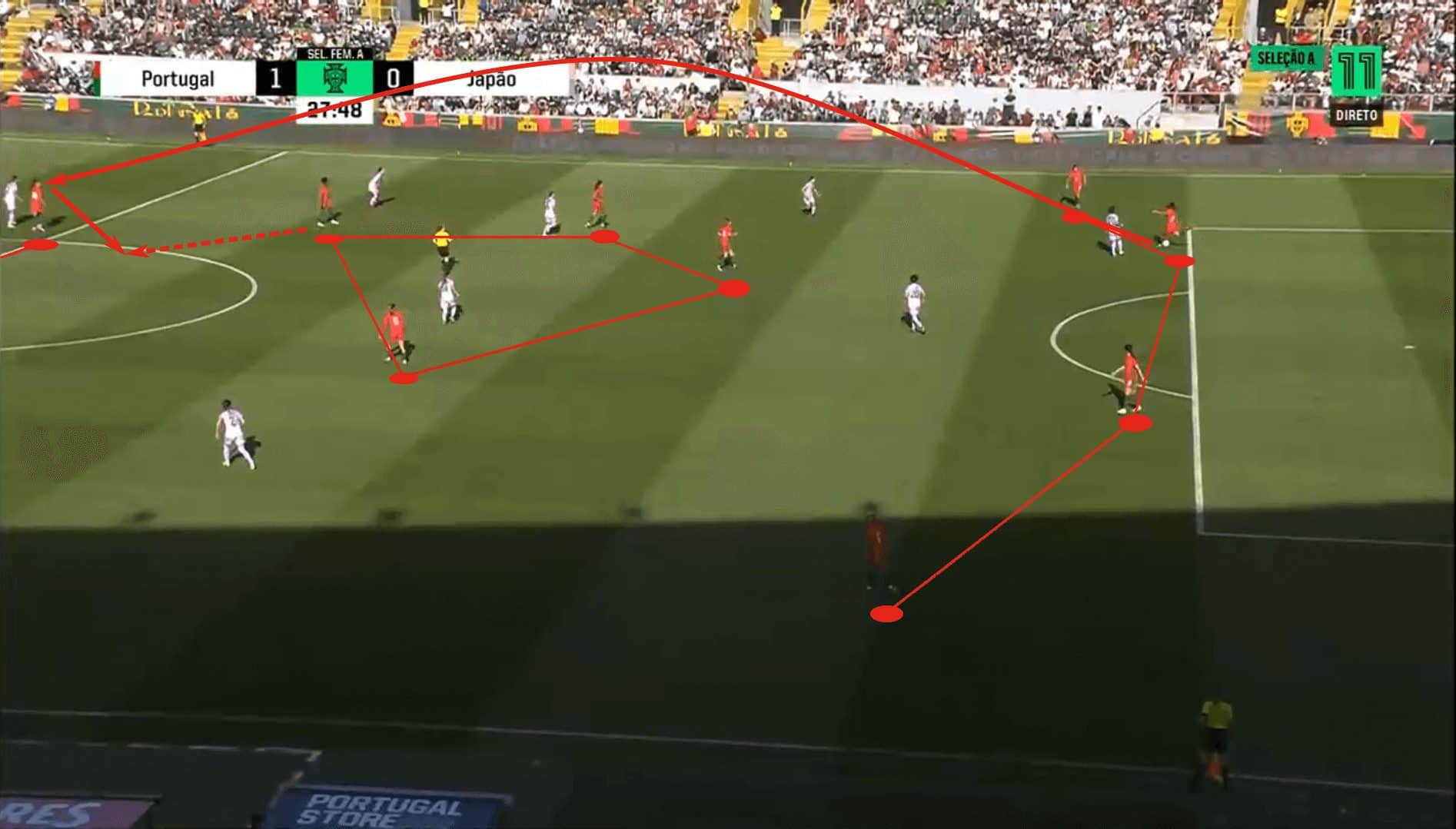

The Portuguese women’s national team gives us a perfect example. Playing a 4-4-2 with a diamond midfield, the long pass was played into Diana Silva, one of the two forwards, and immediately set back into the centre attacking mid. She had great space between the lines and could face forward due to the nature of the pass.

One point that shouldn’t escape notice is the positioning of the two #8s. As the ball’s played up the pitch, they’re prepared to run behind their marks and offer second-ball support. The balance here is not overrunning the second ball and allowing the opposition midfield to get behind them.

When extending the lines vertically, we want to get players into those gaps and receive in a forward-facing position to increase the attacking tempo immediately. If they can drive at the backline with runners in front of them, they effectively create a counterattacking scenario artificially through the build-out.

Ball circulation along the backline and into the holding midfielders creates vertical opportunities in both instances. So, how do we train it?

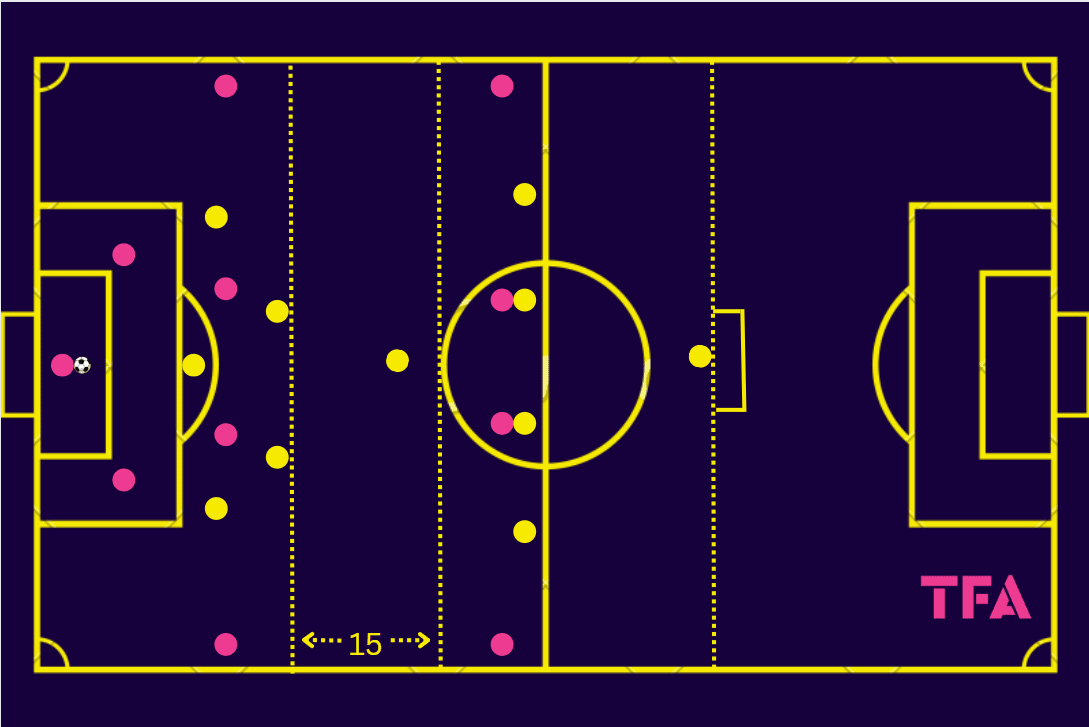

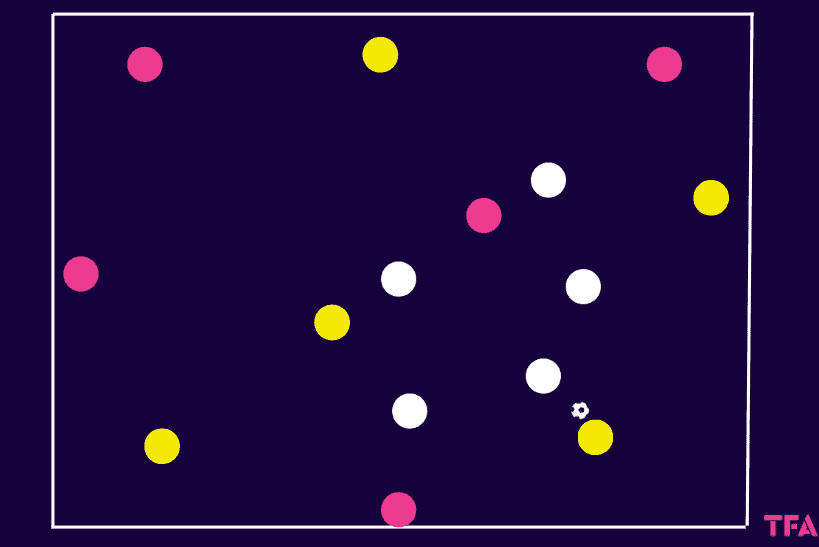

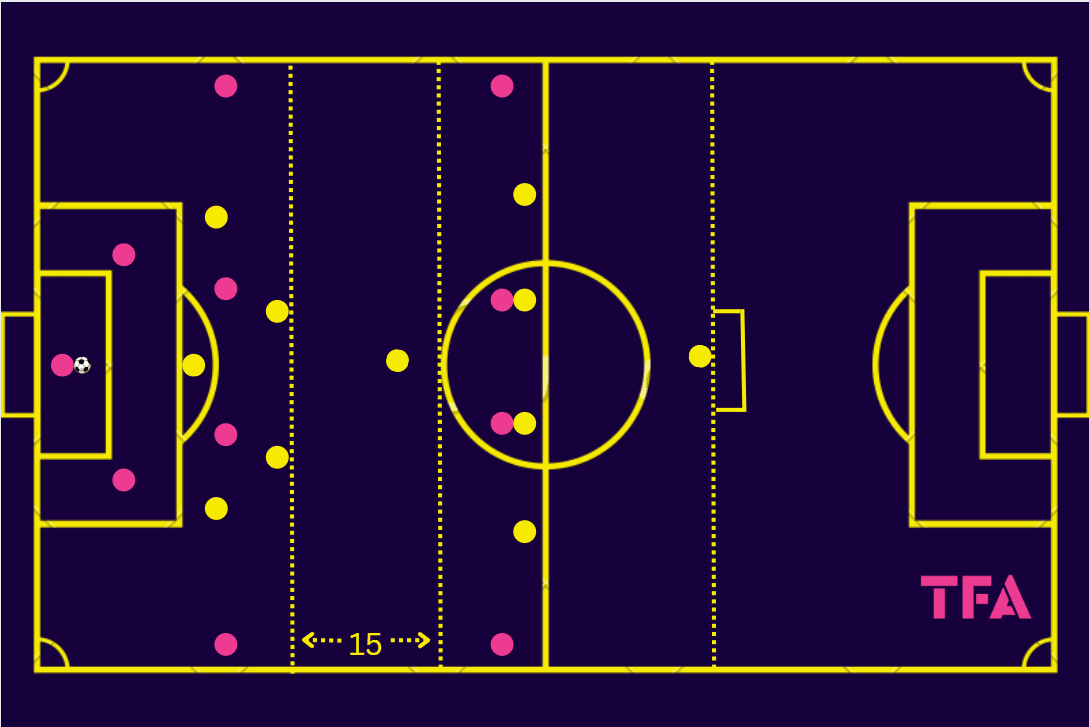

This exercise separates two 30 m zones by a 15 m middle space. As the two teams play 11v11, the focus group’s (pink) objective is to disconnect the opponent’s lines while building out in a restricted area. By limiting the build-out team to 30 yards, we’re emphasising the need to create that space between the lines before increasing the tempo of our attack.

Set the focus team up in whatever system you run and the second group with the upcoming opponent’s tactics.

In order to play into the four players up top, pink must circulate the ball amongst the seven players at the back. In order to receive, the front four must wait for a clear visual signal to check into the space between the lines. To limit the ease of playing into that middle space, the defending team is given one player, the defensive midfielder, who can roam in that space.

Once the focus group passes into the middle third, the two midfielders may join the attack, progressing into the central zone and final third to facilitate the attack on goal. Once the pass to the middle zone is played, simplify the drill and say that play is live. Everyone may push higher as play transitions to the other side of the pitch. That said, direct the pink team to focus on high-tempo attacks to goal.

As a progression, require passes from the defensive third into the middle zone to be played with diagonal passes. A third set-up is to allow a defender from that final third to track the runners into the central zone. Finally, let the back seven skip the middle zone entirely if a longer pass is available, especially a pass into the wings or a ball that sets a runner behind the backline.

For the seven attackers leading the build-out, retaining the ball is paramount. Beyond that, they should keep possession of the ball with short passes while forward-facing players constantly scan the pitch for intermediate and long-range passes. When the opportunity to play out of pressure arrives, they must take it. This exercise is designed to give them reps keeping the ball under heavy high pressure while training their vision to scan higher up the pitch.

Much like Brighton, the two central midfielders will typically be bounce players. We can’t risk a blind turn while playing out of the back, so they must orient their movement to connect with the goalkeeper and members of the backline. Those five players are tasked with playing in the middle zone, not the two midfielders.

The four players in the final third stretch the opposition’s backline while looking for opportunities to check into the middle zone. Once they receive the ball, they aim to reach the goal as quickly as possible, taking advantage of the space created by the deep build-out.

Overload to unbalance in the wings

To create those opportunities for vertical passes, which create artificial turnovers, the ball is circulated across the width of the pitch along the backline. Short-range passes into midfield are additional tools to draw the opposition higher up the pitch.

Moving to overloads to unbalance in the wings, we’re looking for a combination of short and intermediate passes that engage the opponent’s press to manipulate their width and height. While the first section focused on increasing the distance between the midfield and backline for a progressive pass, this section focuses on compressing the opposition’s press.

We want to limit the area the opposition covers while still creating outlets to play out of their press. If those outlets are maintained, then the build-out team can use their pitch control to take unopposed space through the middle third and prepare to attack the final third.

No one does this better than Pep Guardiola. Whether at Barcelona, Bayern Munich or Manchester City, the Spaniard has routinely built and developed press-resistant squads in tight spaces that can play out of intense pressure. Perhaps the simplest way to frame it is through the phrase “overload to imbalance.” Shift numbers near the ball, make progress up the pitch to force the opposition to commit numbers near it, and then attack the spaces they have vacated. In doing so, his sides create the space they want to attack.

This example from last year’s Champions League semi-final against Real Madrid shows the basic idea. Ederson played into the right-wing and Manchester City commenced the build-out. Look at the numbers: City shifts in support of the ball. There is an option high in the wing, two in the right half-space at varying heights, an option underneath from the supporting centre-back, and Ederson is still accessible at the very back. Five options show for the first attacker, which baits Madrid into bringing more numbers near the ball. They think they have City sealed in the wing, but that’s what the EPL champions wanted them to think.

As Real Madrid increases their defensive tempo, Manchester City understand that it’s time to play out of the press. On the left side of the pitch, Manuel Akanji is working hard to offer a passing angle to his deep teammates. The pass does reach him, and he has loads of uncontested space to attack.

Again, there is some risk in taking on this much pressure from the opposition, but that’s where time spent in training to know when and where to support the first attacker, understanding where the outlets are and developing an awareness of when to play out of pressure is so important.

One tool I use with my players is to direct their attention to their personal anxiety or stress during the build-out. Early on, especially when the attacking team enjoys a numeric superiority, composure is high, and the anxiety of losing the ball is low. As the opposition draws more numbers near the ball, the stress and anxiety increase. At some point, we do experience a heightened sense of awareness that the threat of losing the ball is near. That feeling or sensation is the psychological cue to play out of pressure. That’s when the opponents are most committed near the ball, and it’s time for us to attack the space we have created.

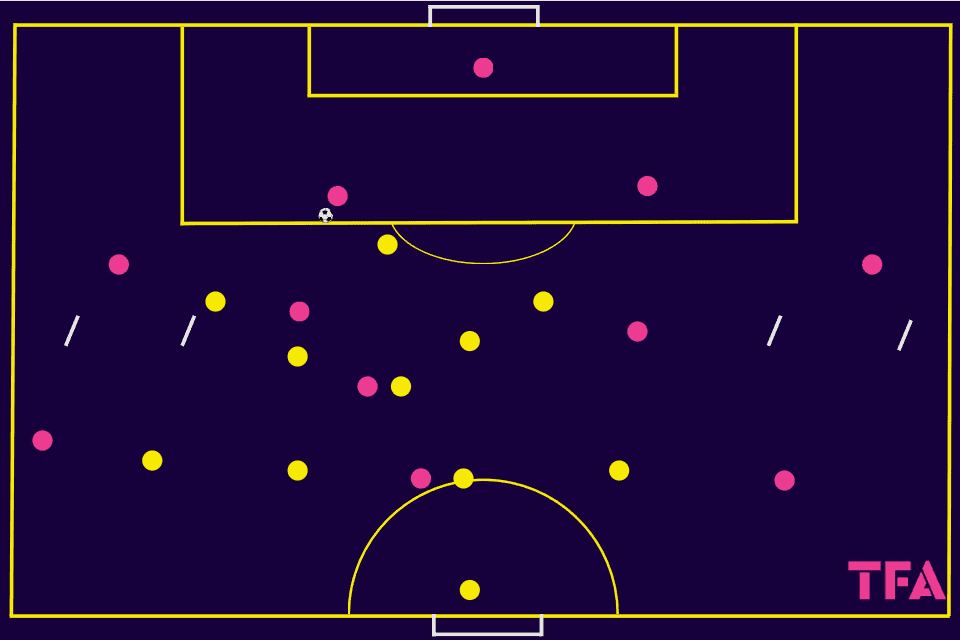

To train this approach of overloading in the wings to unbalance opponents, we will use dribbling gates on both sides of the pitch to encourage players to create these wide overloads. If the opponent doesn’t commit numbers near the ball, take the space that’s given and attack as a collective in that wing. That will force the opposition to shift numbers into the wing more quickly in the future. When they do, the goal is to draw them in, play out of their press and switch the point of attack.

This exercise is shown as an 11v11 game, but we can scale it back to as few numbers as 4v4.

For a small-sided game, adapt the size of the pitch to accommodate the numbers while still emphasising attacking in the wings. If you use this exercise with smaller numbers, 6v6 or 7v7 will give you numbers near the ball and players on the other side of the pitch to exploit space.

For 11v11, we’ll use the full width of the pitch and extend the length 10 m beyond midfield. If you don’t have the luxury of that much field space, scale back to fit what’s available. That may even necessitate fewer numbers on the pitch.

Each team will attack a full-size goal, but to incentivise them to play into the wings, we will give them one point each time they dribble through the gates and make a goal worth five points if they get through one of the gates first.

We won’t force them to go through the gate because the defending team will game the exercise and only defend wide. If the attacking team wants to go to goal through the middle channel because that’s the space given, so be it. They should take what’s given. If the opponent is well-structured, we aim to create the space we want to attack.

Controlling tempo

The first two sections were very pragmatic. Attack Space A to create Space B.

In this final section, the focus is on something less tangible. It’s centred on the concept of controlling match tempo. When opponents are willing to engage in a high press or move from a mid-block into a 3/4 press, there is a battle of tempo and initiative at play.

By taking up a higher position and putting pressure on the opposition build-out, the defending team wants to force the initiative from the defence. They want the opposition to attack at a higher tempo, requiring quicker decision-making and greater technical precision to break the press.

Composure in the build-out is a necessity regardless of build-out objectives. This section is inherently related to the other two. The critical elements of the first two sections are the ability to hold the ball and understand when to break the press.

The attacking team must battle for control of the match’s tempo. From deep in the defensive third, this is where the goalkeeper becomes a critical player in the build-out. He serves to relieve pressure from the backline, especially the centre-backs. As the build-out progresses higher up the pitch, he can still serve that function, as do the centre-backs.

If the opposition cannot generate the pressure necessary to force poor decisions or mistakes, most teams will respond by bringing additional numbers into the press. That’s where IFK Värnamo enters this tactical analysis.

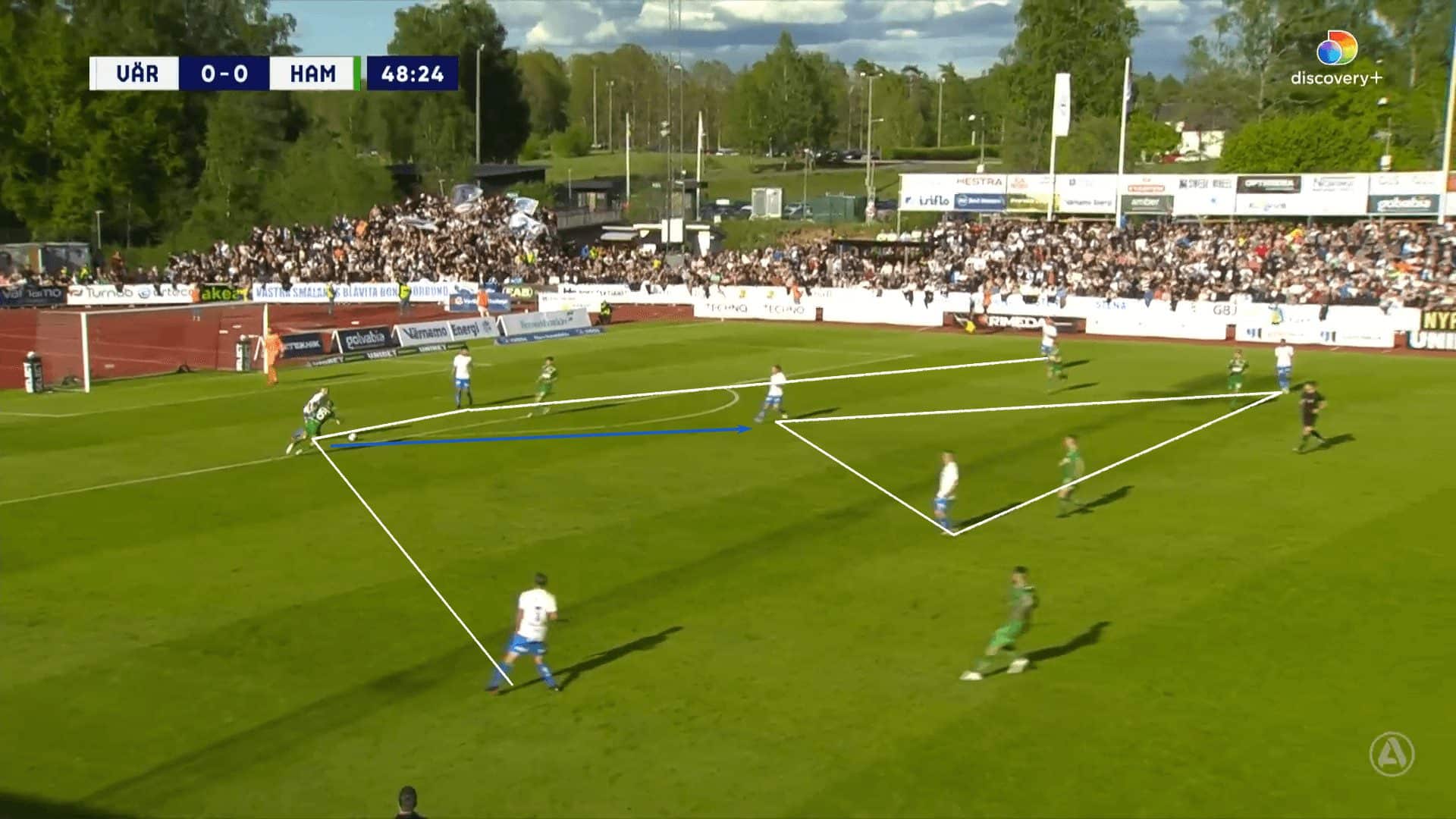

This Värnamo build-out doesn’t look much different from Brighton’s structure and objectives. Värnamo has a 4v2 advantage with the deep build-out between the goalkeeper, centre-back and holding midfielder. The defensive midfielder carefully navigates his space between the lines, offering a short-range, forward pass.

When the ball arrives at his feet, he can receive on the half turn and face forward. That’s the signal the higher players are looking for. In response, the forward drops in between the lines to receive a line-breaking pass.

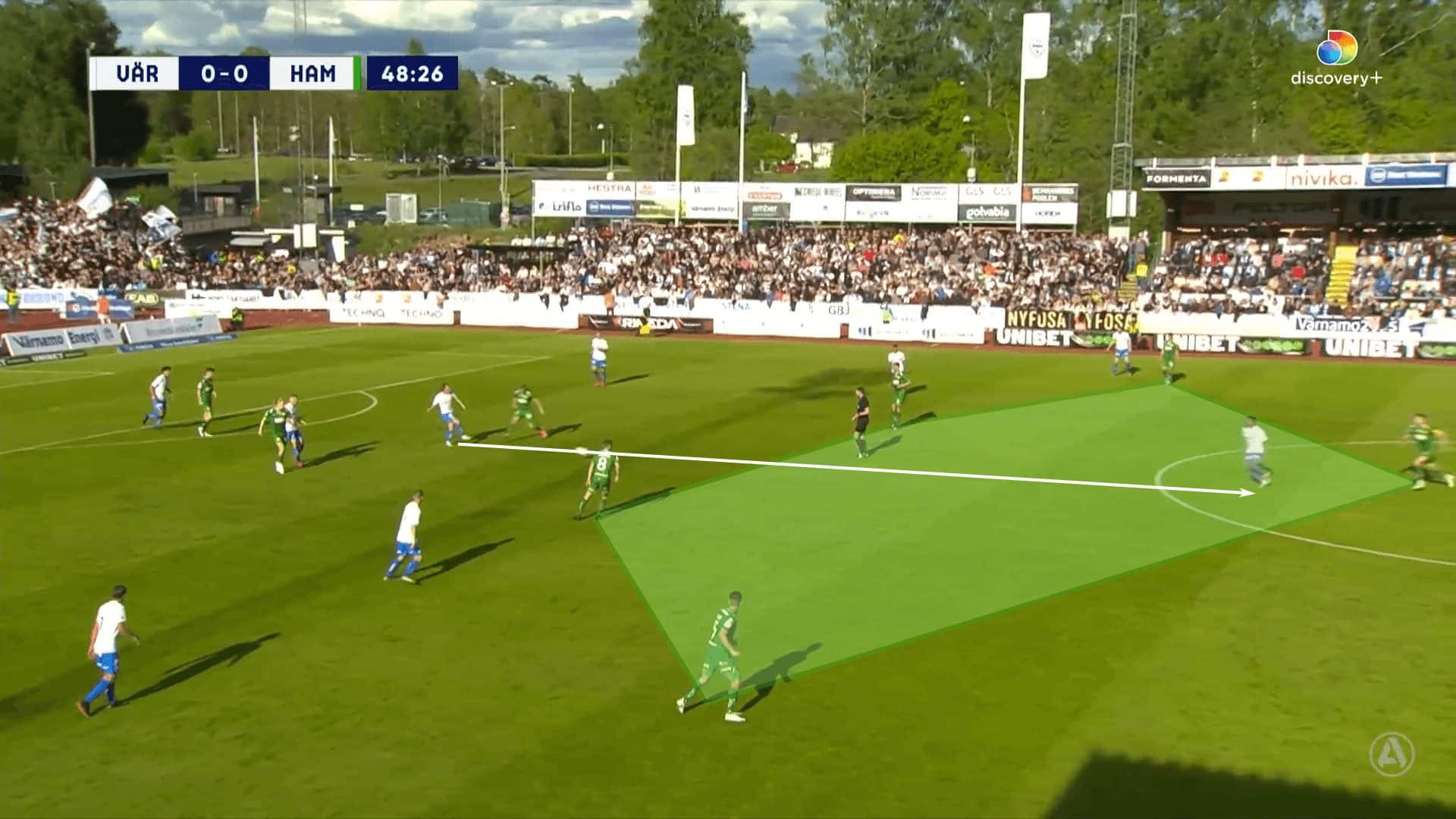

Now that they’ve played into one of the forwards, there’s a team-wide understanding that the attack has progressed from a lower tempo, indirect build-out to a direct possession, which has been covered in another tactical analysis.

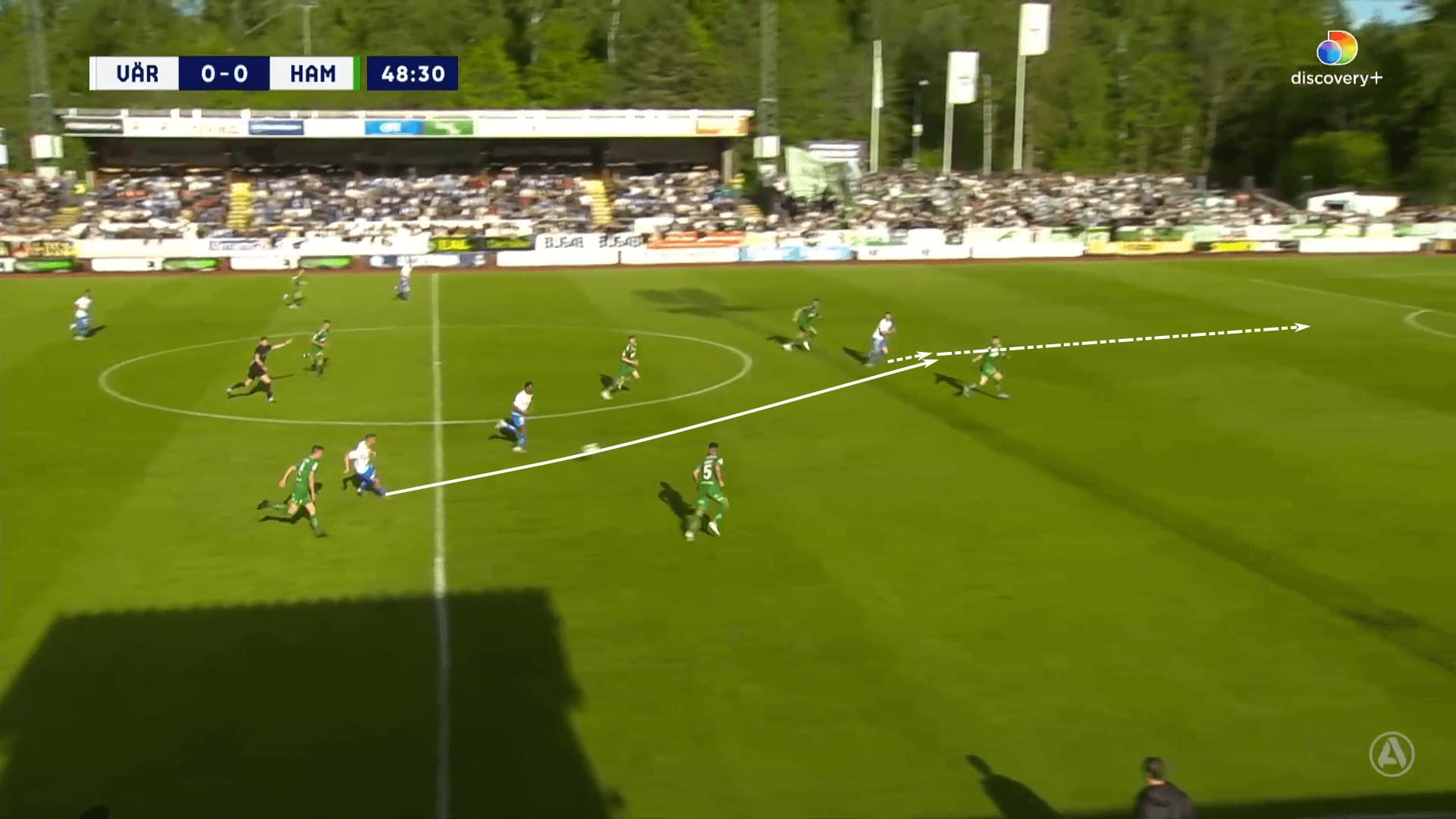

One line-breaking pass signals the team to advance to the next stage of the attack. Control early on unbalanced Hammarby, leading to opportunities higher up the pitch. With the forward pass, the team understands the need to push numbers forward and attack the goal as quickly as possible. One forward pass leads to a second, leading to a race to goal that Värnamo wins.

Since this principle of the buildup is a more general one that is tied to ideas like press resistance, composure, awareness of options and understanding of when to break the press, we want to train the players to have confidence in their ability to possess—developing that ability to keep the ball under pressure, exerting control of the match even while 100 m from goal, is our target.

To train these ideas, we are going to play one of my favourite exercises, a three-team rondo. The teams will play 5v5+5 in a 25×25 m area in this exercise.

Let’s talk about the coaching points before listing different variations of the game. First, coach the little details like scanning and filling the right spaces, proper body orientation and remaining in connection with teammates with high-quality, yet short, movements. Those are your notes for the individual players.

For the clusters near the ball, focus on building an awareness of when to play out of pressure. Have the composure to circulate the ball to draw the opposition in. Once that is accomplished, develop that understanding of when to break the press. Go back to the psychological response, embracing that awareness of increased stress or anxiety to keep the ball. That signals the need to play out of the press.

Draw them in, play out.

Now, here are some variations to the three-team rondo.

- Transitional rondo – Two teams against one. When one team commits a turnover, they immediately transition to defence. No stoppage of play. As they transition on the fly, the new defending team must get organised while the other two teams adapt their attacking shape. Give a point for 10 consecutive passes completed to incentivise the players to move the ball quickly. Both teams in possession receive one point per 10 successive completed passes so that they are more amenable to working together.

- 6-second rule – Two teams against one for 2 minutes. When the defending team wins the ball, their objective is to hold it for as long as possible. For every six seconds they retain possession, they earn one point. Keep track of the points for the three rounds to determine your winner. Another score variation is to continue giving one point to the two attacking teams for 10 consecutive passes completed.

- Dribble-out rondo – The same rules as the second variation, but when the defending team wins the ball, they earn a point by dribbling outside the playing area. A strong counterpress is necessary for the two attacking teams.

- Counterattack goal rondo – Same as the dribble-out rondo, except now, instead of dribbling out of the playing area, the defending team will play into small counterattack goals. I like to use four, but two will suffice if that’s all you have at your disposal.

- Counterattack to a full-size goal – Instead of counterattacking to small goals, set up the playing area at the top of the 18 and allow the defending team to attack the full-size goal when they win possession. You could even adapt the size of the playing area to fit the width of the six, giving a more rectangular playing area.

In the second through fifth variations, if the team with a numeric superiority puts the ball out of bounds, don’t reward them by letting them retain possession. Send a 50/50 ball into the playing area instead. In the transitional rondo, require teams to win the ball in order to move into the attack. Knocking the ball out of bounds means you’re defending in a game, so you’ll continue defending in the rondo.

These three team rondos are incredibly versatile. In each of these adaptations, there is, of course, an emphasis on attacking and defensive transitions. Still, there’s also the opportunity to build confidence in retaining possession, understanding why we possess in the first place and how to use possession more effectively to set up better attacking opportunities. To round off the versatility of the exercise, if the attacking teams are having too much success, there’s also an opportunity to train how to apply pressure on the ball, explicitly detailing the roles of the first, second and third defenders.

The playing area should be tight enough to challenge the attacking players, forcing them to show a high level of focus and competence relative to their ability. Reducing numbers is preferred to extending the playing area for less talented players. Reduce the number of options available to them and avoid distances that require more running than the defenders can handle.

Conclusion

Creating quality opportunities up front can easily start with the quality of work at the back. Well-constructed build-outs create better attacking conditions for players high up the pitch.

The objective of this tactical analysis was to identify fundamental principles of the build-out and relate them to our training. Using the exercises and coaching points provided, our players at the back should come away from sessions with a greater understanding of their importance in developing the attack. The better they can retain possession and manipulate the opposition’s shape, the more space they can create for players higher up the pitch.

After all, that is the end goal of the build-out, right Stuart Robson?

Comments