In modern-day football, teams expect to come up against compact defensive blocks designed to crowd the central areas of the pitch. When the opposition prioritises preventing teams from building the play through the middle, often the most efficient way to goal is by attacking from the wide areas.

Based on teams playing in a 4-3-3, this tactical analysis will analyse the key principles and tactics involved in attacking from wide areas, specifically the movements and combinations of the full-backs and the wide forwards such as overlaps and underlaps. The movements analysed will focus on how teams move the opposition’s full-back to allow either their wide forward or full-back to receive in behind. This tactical analysis will both analyse the movements and suggest how coaches can implement this tactical theory.

The overlap

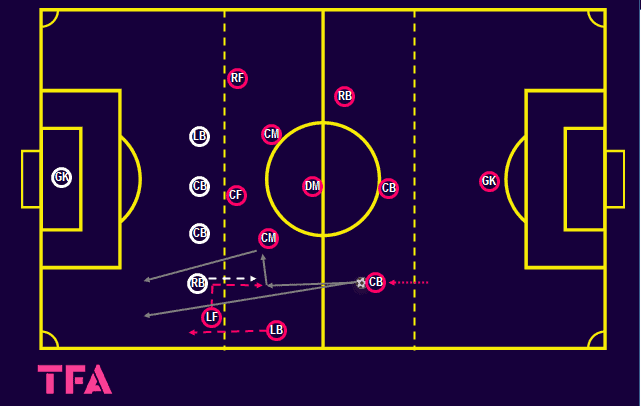

The above tactical diagram shows one of the most common wide-area rotations you will see from sides playing in a 4-3-3. The aim here is for the ball-near full-back to exploit the space created behind the opposition’s right-back by the wide forward enticing the opposition’s right-back towards the ball. Ordinarily, these rotations occur in the middle third of the pitch when there is more space behind the opposition’s backline.

The wide forward lures his direct opponent towards the ball by initially drifting inside to engage the full-back before making a sharp movement towards the ball. If done fast enough, whilst the centre-back (in this example) is carrying the ball forward, the full-back does not have time to think and will usually jump with the wide player.

Once the opposition full-back has been moved out of the backline, the in-possession team have several options. The centre-back could play a simple long ball in behind for his left-back to run onto. Alternatively, he could play into his wide forward’s feet, possibly drawing the right-back closer to the wide forward and further out of position.

When the wide forward receives, depending on the time he has on the ball and the supporting positions of his teammates, he could bounce the ball into his ball-near central midfielder who could play the overlapping left-back in behind. Another option for the forward is to receive taking his first touch inside the pitch. This would allow him to play in his overlapping left-back or to keep driving inwards and combine with his other forwards.

The above example shows Millonairios’ wide forward making the same initial movements described previously and dragging his direct opponent out of position. This time, however, without an overlapping fullback, the wide forward turns inside to combine with the central forward.

The wide forward disguised which way he was going to play by receiving the ball with his hips facing the touchline. As he controlled the ball with the inside of his right foot, he spun to face inside the pitch. The act of taking a touch drew the fullback in even closer, and his body shape made the defender over-commit to defending the outside of the pitch.

This afforded him the space to play into his striker, who had darted into a pocket of space in front of the ball-near centre-back. The right-winger then spun away on the blind side of his marker and attempted to receive a bounce pass in the space he had created behind the opposition left-back.

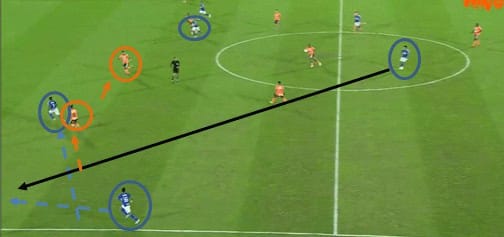

In this example, the ball is in a more central area than in the previous scenarios and is being played by a central midfielder. Millonarios’ left-forward has made a diagonal run from the wide area in behind rather than moving towards the ball.

The wide forward, knowing the ball was not for him, is triggered to make the run when his central midfielder pulls his leg back to play the long ball. The sharp timing of the run makes the opposition assume he is about to receive the ball, and, with that being the most dangerous passing option, the right-back follows him.

The central midfielder’s pass is played long into his left-back. The five-or-so yards the opposition defender has been dragged inside allows the left-back to receive alone. From here, the left-back has several dangerous attacking options. He can play a low, early cross in behind the defensive line or take his touch inside the pitch in front of the opposition full-back to either combine with one of his forwards or to deliver a high cross to what has become a 3v3.

The key to this play working is not just the timing of the wide player’s run but the positioning of his central forward (circled at the top of the image). In the build-up, Millonarios’ central forward drifted away from his left forward and occupied the opposition’s left centre-back. This caused the right centre-back to shift across to cover his central defensive partner, leaving his right back one on one. With no one to pass the wide forward onto, the right-back tracked the wide forward’s run, allowing Millonarios’ left back to receive in space.

Inverted full-back

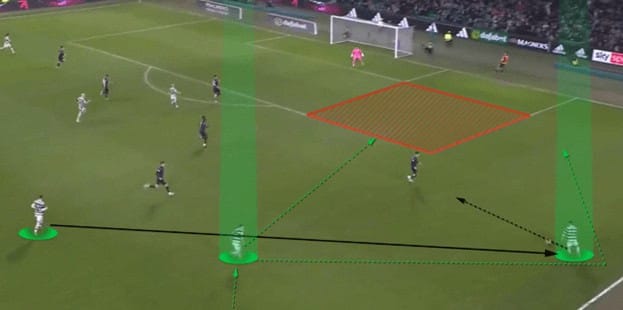

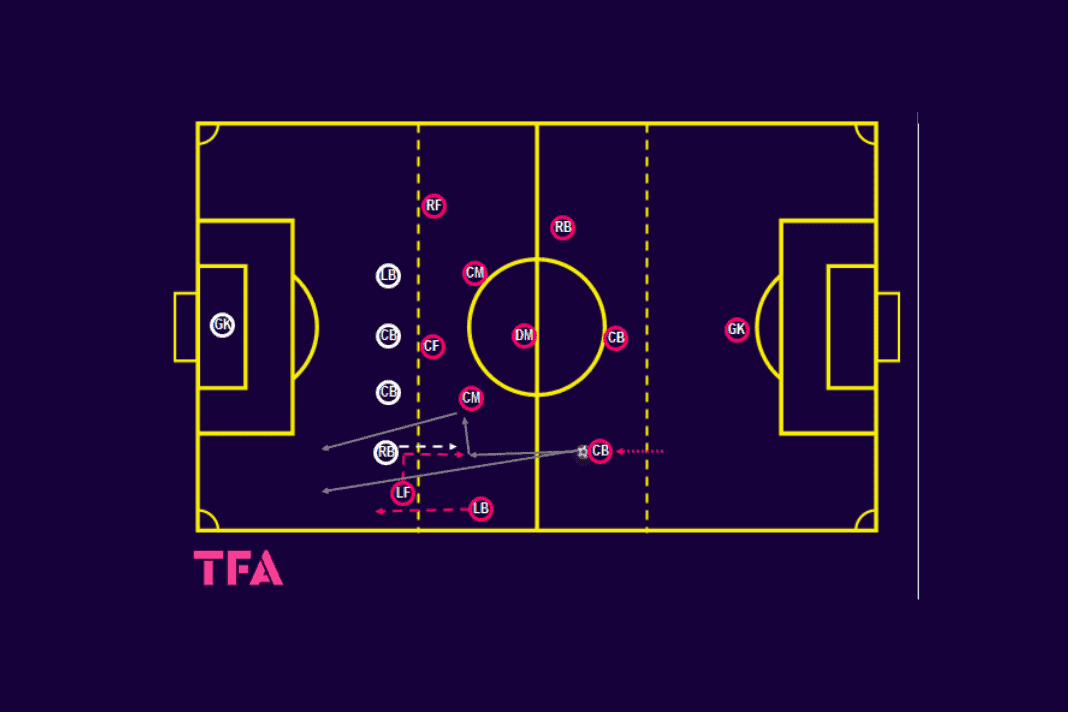

The above image shows a team, Celtic, attacking with both their wide forwards positioned in high and wide areas. As is the case above, this positioning is used to stretch opponents’ backlines, creating spaces in between for runners.

Here, Celtic’s right-forward, Liel Abada, has received a pass in the wide area from his central midfielder Callum McGregor. Celtic’s right-back, Alistair Johnston, whose starting position was also in the wide area, made a diagonal run inside the pitch as the ball was travelling to Abada.

Abada received the ball with an aggressive, diagonal first touch towards the opposition’s left back. This touch pinned the left-back, forcing him to engage with the ball. Now, from an inverted position, Johnston has the choice of making an overlapping run around the outside of Abada or into the half-space inside the box.

If Johnston chooses to overlap, which he did on this occasion, he can act as a supporting option for a pass. If he receives the ball, he is in a good position to provide a cross or cut-back. He can also be used on the overlap as a decoy for Abada to take on the full-back.

Johnston could have elected to make a straighter, underlapping run into the box, as Celtic’s full-backs often do. These runs are difficult for the opposition to pick up and can result in Celtic’s full-backs receiving the ball in a dangerous area.

To avoid pulling their centre-backs even more out of shape, the best the opposition could do in this scenario is for a central midfielder to track Johnston’s run. Had the nearest opposition midfielder to Johnston followed him into the box, McGregor would have been able to receive the ball back, alone. The midfielder would have been within 30 yards of goal with five teammates attacking the box.

Arteta’s angles

The above image shows Arsenal’s build-up play for their first goal against Liverpool in the two teams’ most recent EPL meeting. Ben White, playing as a right-back, is in possession and is about to play the ball into Bukayo Saka. In similar scenarios, you will often see the full-back playing a flat pass into the wide forward’s feet. However, White plays the ball at an angle, inside the pitch, for Saka to run onto.

Arsenal’s Mikel Arteta, in a widely shared clip on social media from a coaching conference, explained the importance of this micro-tactic. Regularly, wide forwards will receive a straight pass from their full-back near the sideline with their back to goal. Receiving this way makes it easy for the opposition to force them backwards, often eliminating passing options as they do, and dispossessing the attacking team.

When the wide forward is forced by the angle and direction of the pass to receive inside, he controls the ball facing inside the pitch. This creates many more options for him. His movement to receive the ball is also difficult for the opposition full-back to track. The full-back will often rush to close down the wide man, expecting him to receive to his feet before the angled pass is played.

In this example, Liverpool’s Andy Robertson, expecting Saka to receive in his static, wide position, sprinted to close him down. Perhaps wary of Saka’s ability to face up and take players on, Robertson ran straight at Saka. When White played the ball inside, Robertson could not adjust his run, slipped and allowed Saka to receive. Saka’s positioning and body orientation was then what allowed him to find Martin Ødegaard who set up the opening goal of the match.

Coaching attacking from wide-areas

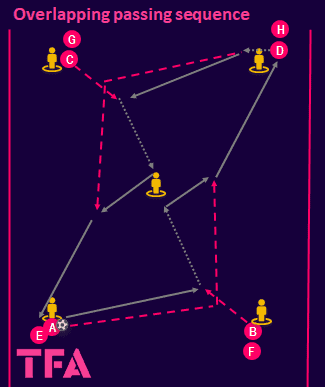

To bed in the overlapping component of attacking in the wide areas, the above passing exercise can be incorporated into the warm-up. The exercise begins with player A passing the ball to player B. The pass is slow enough to encourage player B to move inside to meet the ball.

Player B then takes a positive, diagonal touch towards the central mannequin, representing a defender. Player B’s inside touch is the trigger for Player A to overlap B. Player B drives at the mannequin before playing his overlapping teammate in the opposite half of the area. Player B should time his run so he is not beyond the mannequin and “offside” when the ball is played.

Players A and B then cross over each other again in the opposite half. This prevents the same players from performing the overlap each time. A and B join the end of their corresponding lines before repeating the exercise in the opposite direction. Two balls can be in play at a time, depending on the level of the players. Players should be encouraged to play at game speed to make the timings of their movements realistic.

Crossing and finishing patterns of play

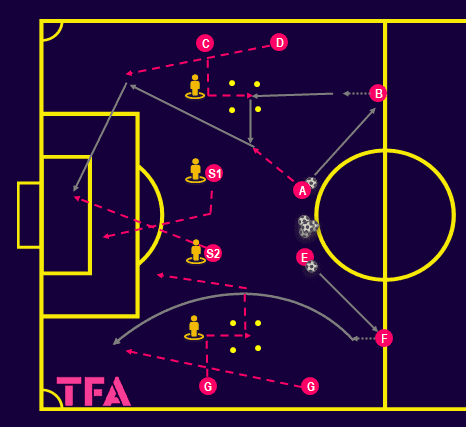

This crossing and finishing exercise allows coaches to work on the movements and rotations described in the previous sections. The pattern begins with Player A, who represents a central midfielder, playing the ball into Player B, his centre-back.

The centre-back drives forward with the ball before playing into his wide forward, Player C. As the wide forward sees his centre-back coming forward with the ball, he should drift inwards and push off the mannequin before making a sharp movement towards the ball. As the ball is travelling to Player C, Player D, the full-back, should begin his overlapping run.

The wide player should receive the ball with his hips facing the centre of the pitch and either take his first touch in this direction or play (an ideally angled) bounce pass into his central midfielder (Player A). Player A then feeds in the overlapping full-back who delivers a cross or cut-back, depending on the weight of the pass received.

The two strikers labelled S1 and S2 in the diagram, can remain as forwards throughout the exercise and when the ball is played from either side. In each instance, the ball-far forward represents a wide forward that has moved inside the pitch as the play has developed in the opposite wide area. Both players attack the box for every cross and should attempt to make crossover runs. All the other players rotate from A to B to C etc.

When the pattern on one side has been completed, it begins again on the opposite side. As shown in the diagram, different movements can be introduced. Players should be reminded about the importance of the timing of their runs and the triggers of when to make them. The drill can progress to an opposed practice with defenders, initially full-backs, being introduced.

Conclusion

With space to play in central areas becoming increasingly rare, often the best solution is for teams to attack from the wide areas. The ultimate aim of these attacks is usually for the wide players to entice the opposition’s full-back out of position to exploit the space behind them.

By having pre-planned, often simple, movements and triggers, full-backs and wide forwards can combine to get into these areas and provide crosses and cut-backs. To implement these combinations, full-backs must be high enough to interact with the wide forwards and be willing to run beyond them. The players must also be provided with enough variations so their movements are not too predictable.

Comments