Goal kicks have become integral to most teams’ build-up play and can often indicate their overall playing style. Many variations of set-ups and movements are now on display each weekend. No longer are goalkeepers only asked to push their teammates up the pitch, aim for a big striker and hope to win second balls.

The development in goal kicks has been brought along significantly by the implementation of the new goal kick rule in the 2019/22 season. This new rule, allowing the ball to be received in the box, was designed to curb time-wasting and speed up the game. Previously, the ball was not in play until it left the penalty area. If a receiving player was pressed, the player could deliberately step into the box to touch the ball. This would result in the goal kick being retaken and the in-possession team being let off the hook.

Consequently, this has dramatically extended goalkeepers’ involvement in building up from goal kicks. They are so integral that some are receiving, instead of playing, the first pass. This new FIFA law has probably had the most significant impact on how the game is played aesthetically and tactically since the pass-back law was introduced in 1992.

With new goal-kick set-ups occurring every week, coaches are constantly plotting new ideas on how to press and trap opposition teams from goal kicks. This has led to a continuous innovation cycle on both sides of the ball.

This tactical theory will provide a tactical analysis of how teams can build up from goal kicks. The primary analysis will be of De Zerbi’s Brighton and how they implement the latest trend of centre-backs taking the kick and passing to the goalkeeper. This tactical analysis will also include examples of how Pep Guardiola‘s Manchester City scored from playing goal kicks long. This analysis will also suggest how coaches can implement build-up play tactics from goal kicks.

First pass to the goalkeeper

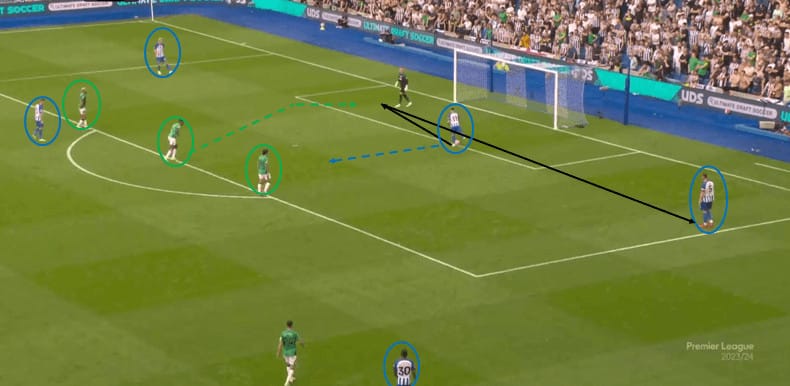

The above image shows Brighton’s set-up for goal kicks in their Premier League match against Newcastle this season. Brighton kept four players high in the build-up and six outfield players around the box. Newcastle matched this, pressing high with six payers. Three pressing players can be seen above, ready to pounce as soon as the ball is played. They have two players marking Brighton’s full-backs and one midfielder in the central area, just out of shot. Brighton’s right-back, out of shot, is in a symmetrical position to his left back.

Although the primary reason for Brighton’s goal kick set-up is to find a way through the first line of pressure, there is an added benefit. With six players in or around the goal area, should Brighton lose possession, there are enough players that the situation does not turn into a specific goal conceded.

In this example, Brighton began the play with their defensive midfielder, Billy Gilmour, passing to the goalkeeper, Bart Verbruggen. Even under intense pressure, Verbruggen is willing to receive the ball and is aware of how he is being pressed. Newcastle’s central forward pressed with a slightly arced run designed to force Brighton back to Brighton’s left.

As Verbruggen received the ball, Gilmour immediately began drifting away. This opened up the pass from Verbruggen to his left-centre-back. The centre-back’s relative width made it difficult for the right-sided Newcastle forward to press and prevent him from playing the ball forward.

Before the pressing forward could get close enough to affect him, the centre-back had already played the next pass. The left-back’s positioning is also pivotal here. He attracts Newcastle’s widest player because he is relatively low and wide, creating a passing lane in the half-space.

With a first-time pass, the centre-back found one of his forwards who had dropped from a high position towards the ball. Gilmour, who had drifted away from the ball, did not attempt to show for a pass from his centre-back. By disregarding a pass from his centre-back, he was then able to receive a bounce pass in space and face forward from his forward. Gilmour attacked the space ahead and attempted a through ball to one of his forwards.

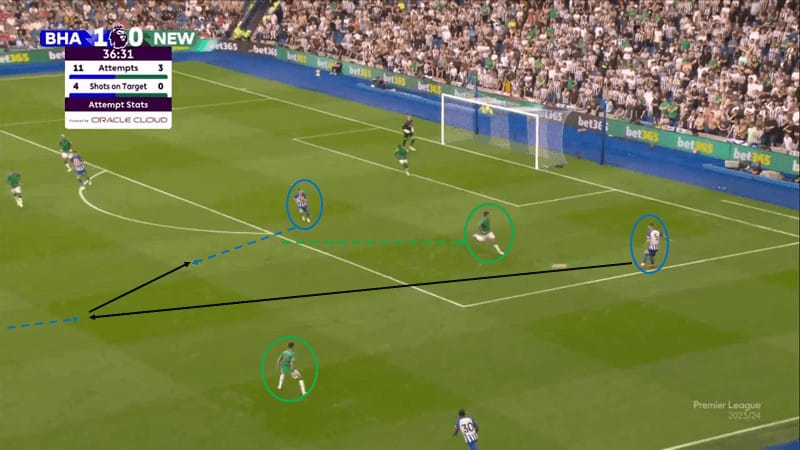

In this example, Brighton set up the same way with the centre-back again passing to Verbruggen. The positioning of the front four meant they pinned back Newcastle’s back four; a huge gap was created between the box and the halfway line. This time, Verbruggen clipped the ball into the space towards his forward.

The forward met the ball and flicked it onto his teammate behind him. His teammate, controlling the ball with his feet, turned and dribbled at Newcastle’s backline. This launched a four-on-four race towards Newcastle’s goal, resulting in a shot from inside the box for Brighton.

Verbruggen took the goal kick in another variation from the same game, passing to Gilmour. Gilmour put his foot on the ball to bait Newcastle’s forward into pressing him. When the forward engaged, Gilmour played back to his goalkeeper. Verbruggen was then pressed by the same forward, leaving Gilmour free. The right centre-back was then able to play into Gilmour, who, again, received facing forward.

Long goal kicks

Having a goalkeeper who can kick long distance accurately has the advantage of being able to threaten in behind straight from a goal kick. Manchester City’s Ederson once assisted Aguero in such a manner with a goal kick pinged deep into the opposition’s half. Aguero could occupy an “offside” position with no offsides from goal kicks.

By being able to put a player through on goal directly, and with no offsides from goal kicks, teams are forced to drop their backline. This stretches teams, creating more space between their front, pressing line, and their defenders.

Having a goalkeeper who can kick long distance accurately has the advantage of being able to threaten in behind straight from a goal kick. Manchester City’s Ederson once assisted Aguero in such a manner with a goal kick pinged deep into the opposition’s half. With no offsides from goal kicks, Aguero was able to occupy an “offside” position.

By being able to put a player through on goal directly, and with no offsides from goal kicks, teams are forced to drop their backline. This stretches teams, creating more space between their front, pressing line, and their defenders.

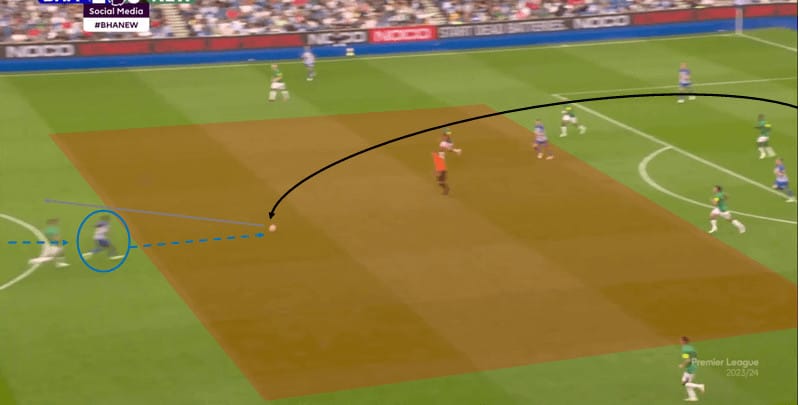

In this example, from a Manchester City game at Everton, Everton’s deepest player has dropped almost 20 yards into his own half to defend against Ederson’s long ball. The fear of the long, direct ball, plus Everton’s man-marking system, has created a massive gap in the middle of the pitch. Playing against a man-marking system allows the in-possession team to dictate where the space on the pitch is.

City used this to pin Everton’s side centre-backs deep and wide before their wide players made central runs to receive from Ederson. Moving inside from City’s left, Sané met the ball in the air. Kevin De Bruyne circled on the edge of his box and sprinted forward when the ball left Ederson’s foot.

The central striker pinned the deepest centre-back to allow De Bruyne to run down the side of him and remain onside. Having controlled the ball, Sané then played his attacking midfielder in behind. De Bruyne ran onto the ball to provide an assist.

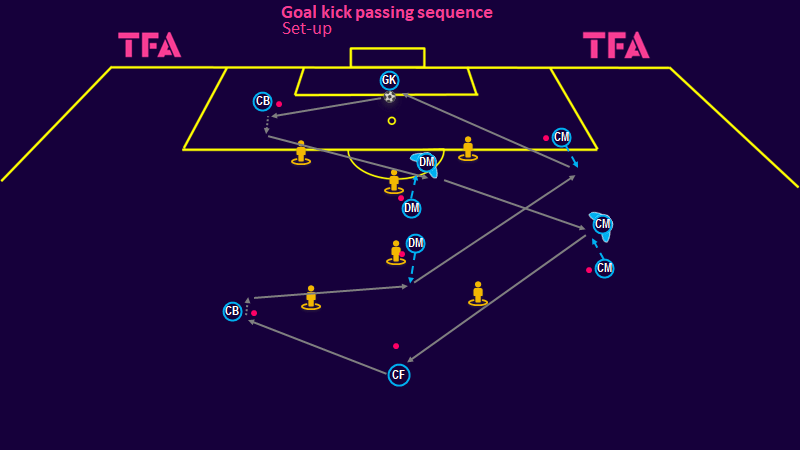

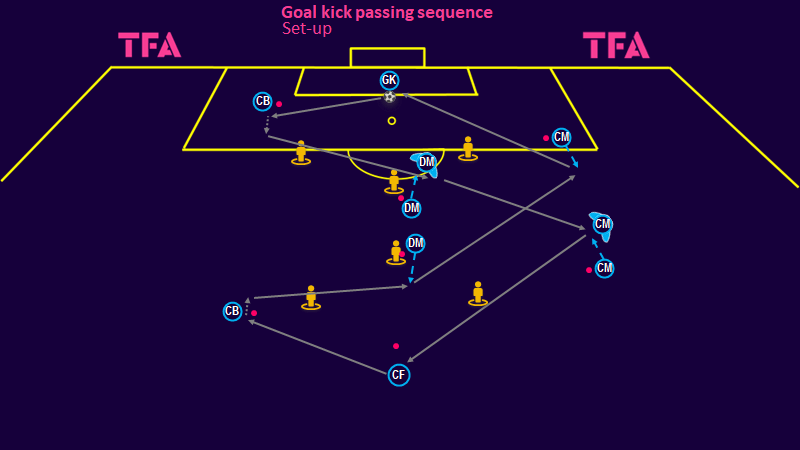

Goal kick passing sequence

This passing sequence is designed to replicate the starting positions and movements of a goal kick being played within the in-possession team’s box. The exercise is just over double-penalty box in size and goes in both directions to keep a continuous sequence. Players initially play and follow their pass to the next cone. The set-up allows players to work on their movements, body shape, and execution unopposedly.

Multiple balls can be used, and players can double up at each cone to speed up the rotation of the exercise. Extra players are required at both ends (not shown on the diagram) to restart each repetition. The positional tags each player has been given, e.g., “CM”, is to highlight the position they represent at that given movement of the sequence.

For the first sequence, the player representing the goalkeeper plays out to his right centre-backs outside foot. The centre-back takes a positive first touch before playing into his defensive midfielder. The defensive midfielder, simulating receiving under only half pressure, should receive at an angle, facing forward. This allows him to see both the ball and where his next passing option is. Each receiving player’s trigger to show for the ball is the first touch of the player receiving previously. Their movements and positioning should always allow them to see their next pass.

Variations to the player movements can be added to coach players on protecting the ball in different situations. For example, when working on the defensive midfielder being pressed, the midfielder may be unable to open up securely. Instead, a bounce pass, with a closed body shape, back to the centre-back or goalkeeper could be used. The midfielder could then move to clear the path to allow the defender or goalkeeper to play the progressive pass.

The exercise and positioning of each player can be adapted to suit the desired goal kick set-up of the coach. The coach should encourage a match-like speed of play, with the type and quality of each pass being vital.

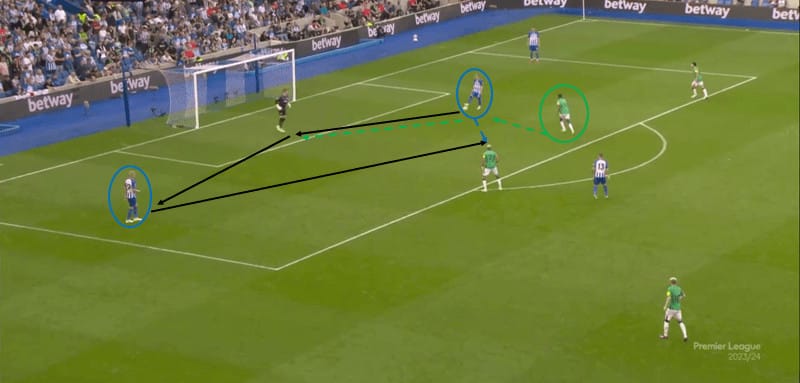

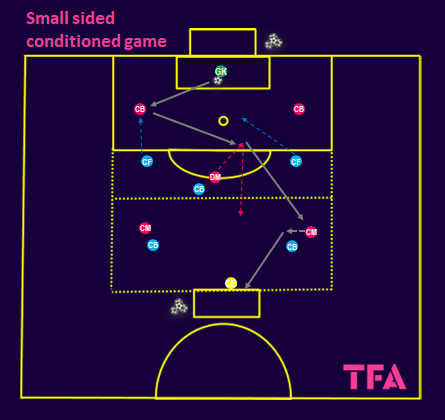

This small-sided conditioned game is designed to simulate playing out from goal kicks under high pressure from the opposition. It is designed for teams who want to play out centrally and work on their press resistance. The game is 6v6 with five outfield players. The five outfield players represent the centre-backs and three central midfielders, modelling a 4-3-3 formation.

Play begins with the goalkeeper passing to one of the centre-backs, who are both inside the box. The defensive midfielder begins in the middle zone but is free to move into the penalty box as soon as the ball is played. The central midfielders must remain in the opposite penalty box. Having a third zone that the central midfielders must remain in prevents them from moving towards the ball and crowding their defensive midfielders’ space. There is no offside, as the highest-placed players represent central midfielders playing in their own half.

When the ball is transferred into the final zone, the defensive midfielder should move into that box to support the play. One defending team player can follow the midfielder into that zone to create a three-against-three. In the above example, the in-possession team plays out under man-to-man marking. To simulate having an overload in the defensive third, a neutral player, who plays for whatever team has possession, can be added.

The two players representing central midfielders become central forwards in the defensive phase. These players should be encouraged to press aggressively. They can be coached on how best to trap teams, for example, not allowing the centre-back to go back across the box to the goalkeeper or opposite central defender.

Each restart begins with a goal kick. Initially, coaches can allow time for the opposition to set up to enable the team to work on specific patterns under these circumstances. As the game progresses, goalkeepers should be encouraged to retrieve a ball quickly to make it more match-like when the ball goes out of play. They should then try and restart the play when the opposition is still unbalanced. An outfield player can take the kick if desired, as per Brighton’s example.

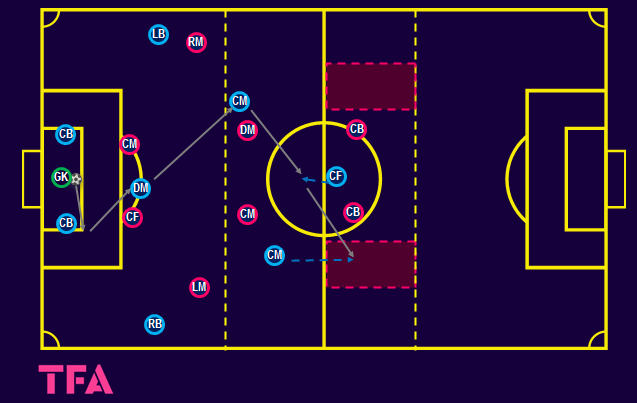

In this 8v8 game, the working team has to build up from a goal-kick and work the ball into the half-space (red boxes) in the opposition’s half. The attacking team (blue) is set up with a back four, midfield three and a striker to replicate a 4-3-3 without the wingers. When the pink team attacks, they adopt the same formation as the blue team did whilst attacking. The wide midfielders become full-backs, with the central midfielders organizing themselves with a single pivot.

The central midfielders are not allowed back over the yellow dotted line to encourage space in the build-up phase and to give more attacking options further up the pitch. The five outfield players involved in the initial build-up phase can support the play in this zone. Coaches should encourage these players to keep the ball while leaving themselves defensively well-balanced. Should the pink team regain possession, they attack freely towards the goal.

Conclusion

As shown with the examples from Brighton alone, the variations to goal kick set-ups and movements are almost endless. Teams are becoming increasingly creative with how they play out, showcasing new ideas every weekend. Coaches need to prepare their sides to face numerous styles of pressing as, with that side of the game, teams are becoming increasingly creative.

Comments