When it comes to defending and much of the content that has been written about it online, the same principles or similar versions of the same principles are usually mentioned. These principles are generally centred around the defensive shape of a team needing to be compact near the ball to cover shorter distances when pressing the ball carrier, supporting each other’s pressing actions and covering passing lanes.

Thus, a team looks to control the space around the ball and make it as difficult as possible for the opposition to progress the ball. What has also been largely written about is how four reference points guide these defensive principles — the ball, the opposition players, the space around the ball and the teammates of an individual player when defending.

These reference points are used to aid players in making coordinated actions and movements to limit space around the ball for the opposition and limit ball progression. It must be noted that these principles and reference points mentioned are not set in stone. More can be added, and their importance changes depending on which third a team is defending in, as well as the philosophy of a coach.

What is also important to note is how these principles do not exist in a vacuum and would have to be accompanied by other behaviours and actions from players for a side to improve defensively.

This tactical theory and analysis will present ideas on how these general principles can be trained to be able to defend effectively in a mid to low-block.

The significance and insignificance of defensive structure

An essential part of what allows players to implement the principles mentioned above is tied to a team’s structure in the game’s defensive phase. This structure is not just rooted in a particular formation that a side uses to defend but more so in whether or not the positioning of the players allows them to cover key areas of the pitch adequately. A side may choose to defend in a 4-4-2, but situationally in a game, this may need to change to something that resembles a 4-5-1 or 4-3-3.

The structure of a side, whether they start the game with it or adapt to the demands of the game, should allow players to have as few responsibilities as necessary for them only to have to cover a few players, travel short distances and protect small amounts of space. This gives them a platform to remain compact, support each other, and limit space around the ball for the opposition.

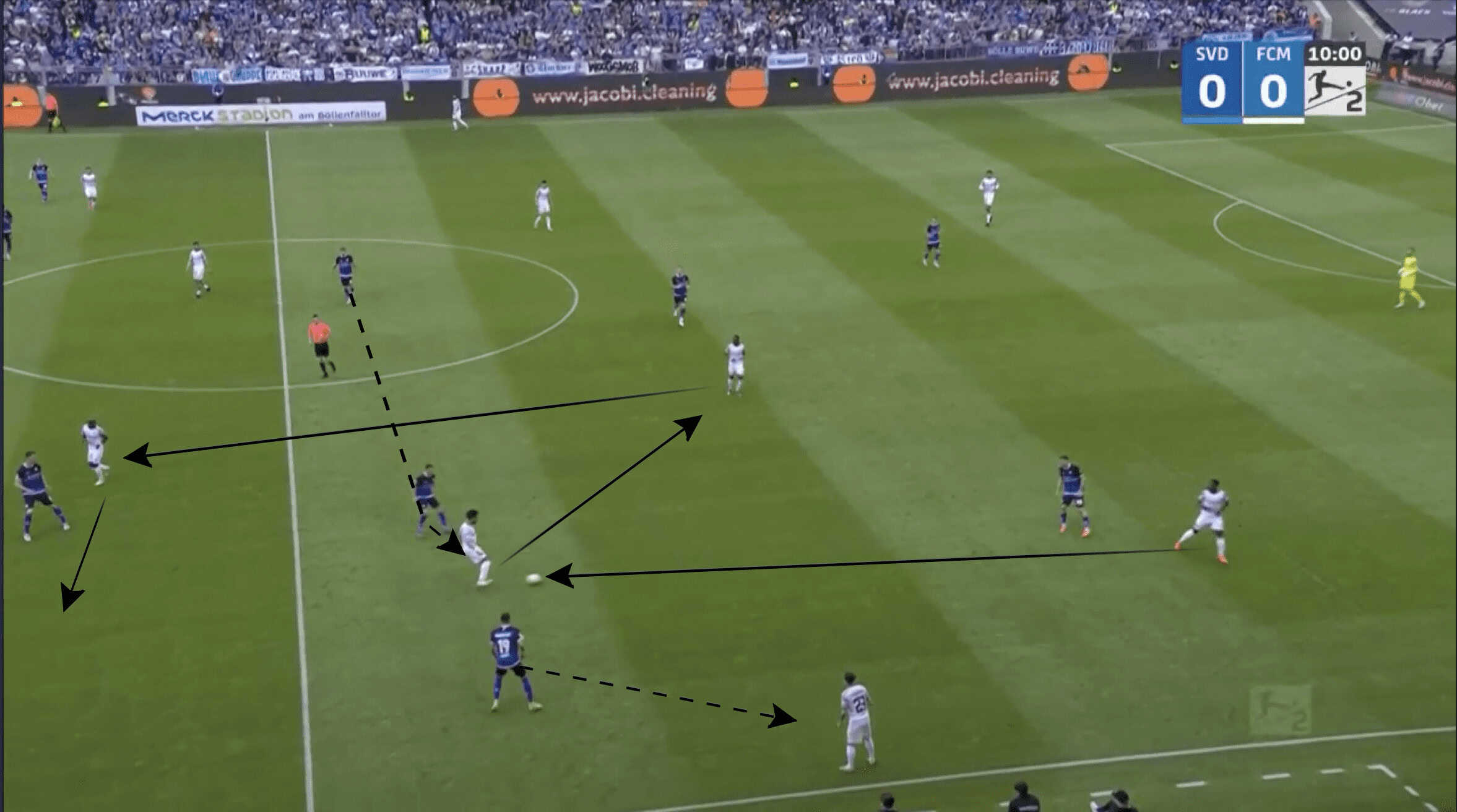

Below, although slightly more advanced than a mid-block, shows an example of how the structure of a side can hinder them in the defensive phase of the game.

In this game, Darmstadt’s midfielders continuously struggled with shifting to access the wide areas and simultaneously remain compact in the centre. In this instance, Tobias Kempe shifts to the right to press the opposition player, with Fabian Schnellhardt remaining in the centre. As a result, space is created between the two players, allowing for a pass through the centre.

As stated before, the structure of a side can provide them with a platform to cover space, support each other and cover the opposition. However, if players do not understand when to adjust their positioning to mitigate risks or even how, the opposition will still be able to progress the ball with ease.

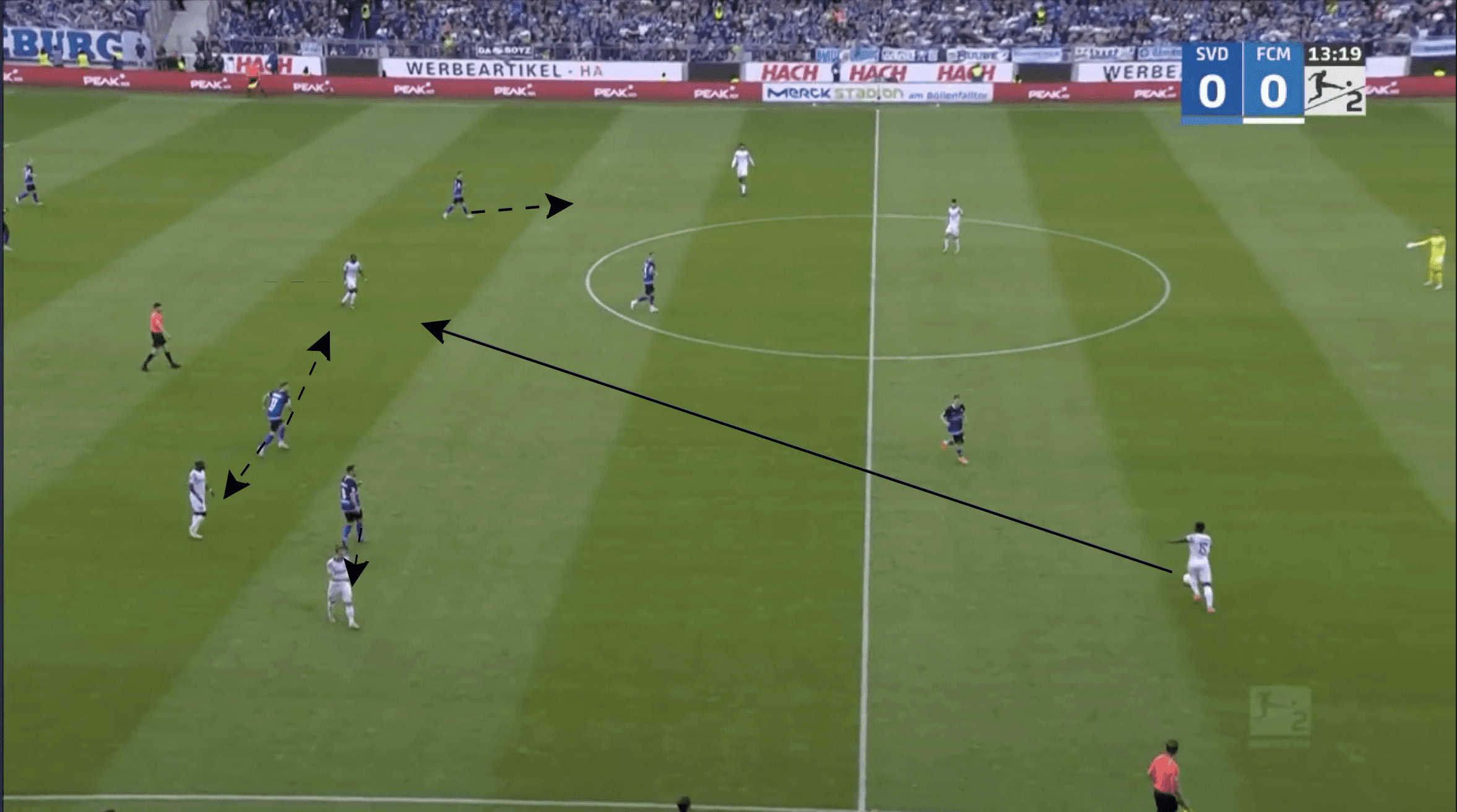

The example below is from the same Darmstadt game, where after a counterattack, the left winger of the side, Marvin Mehlem, would be positioned in the second line of the defence, forming a situational 5-3-2.

Theoretically, with three midfielders and two strikers, the midfielders would be able to cover the wide areas but remain compact centrally, with Antonio Conte’s Internazionale being an example of a team able to do this well. In the example below, however, two midfielders shift towards the wide area to cover the opposition players; Mehlem adjusts his position to cover the right-sided centre-back instead of pushing towards the centre to cover the space — as a result, Schnellhardt begins to move towards the centre from the wide areas to cover the opposition player.

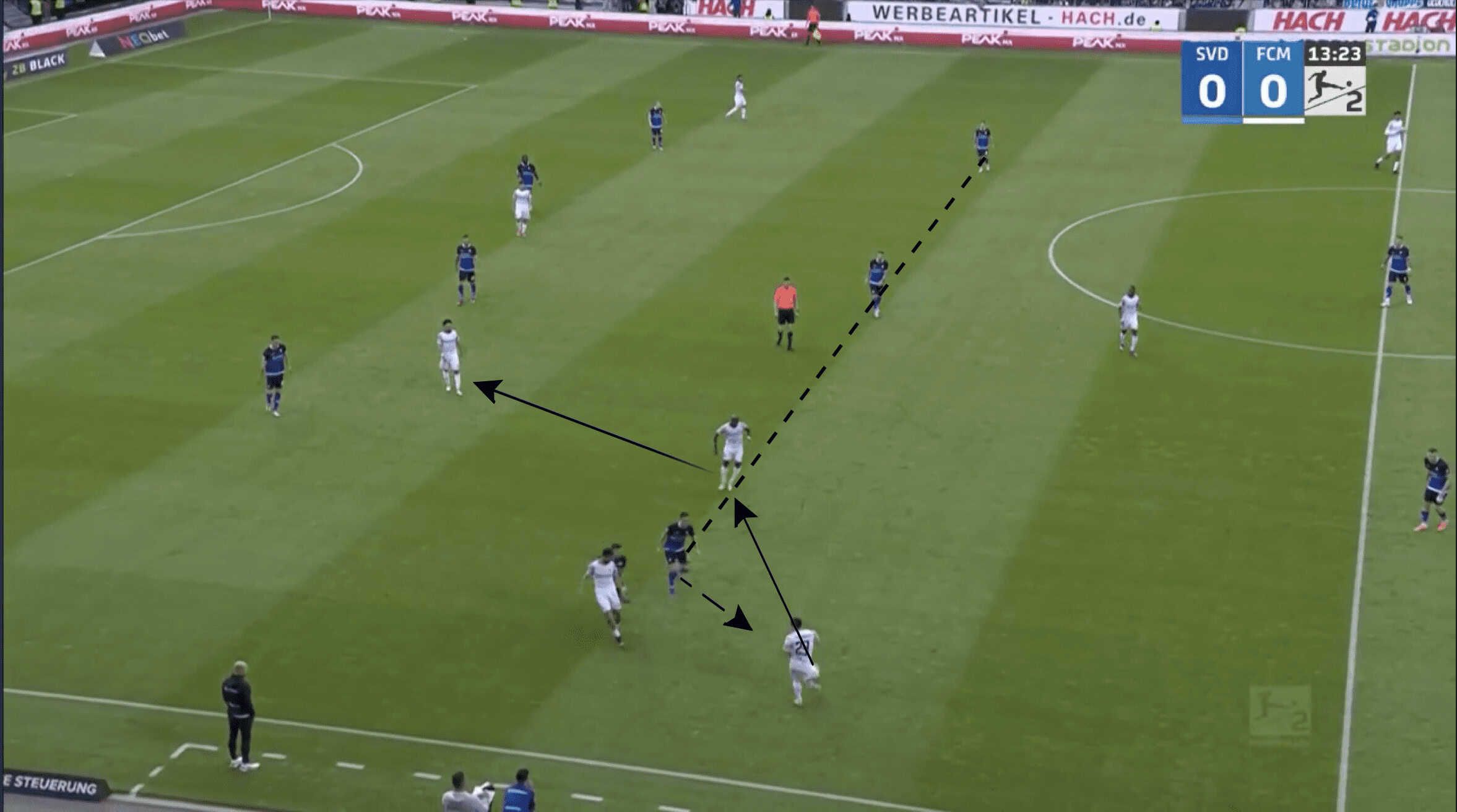

Moving on, we see large spaces are created between Darmstatdt’s midfielders, preventing them from being able to protect the centre or adequately cover the wide area, as seen below.

Thus, through this section, it can be seen that a side’s structure does play an essential role in the defensive phase of the game, but the effectiveness of a structure and what allows players to prevent progression and win back the ball depends on the actions and behaviours of players within this structure.

This is ultimately the objective of coaching, to give players the necessary tools that allow them to adapt to the needs of the game and be able to solve problems on their own. So which behaviours and actions can players learn for them to be able to solve problems?

Critical behaviours and actions in defence.

Awareness & positioning.

For players to be able to adjust their positions adequately regarding the reference points mentioned earlier, they need to have an understanding of the conditions around them. This understanding will help them assess the danger of different risks, allowing them to take their following action with these risks in mind. The only way to do this is through scanning, with players needing to understand what they are scanning for — which is where defensive reference points come in.

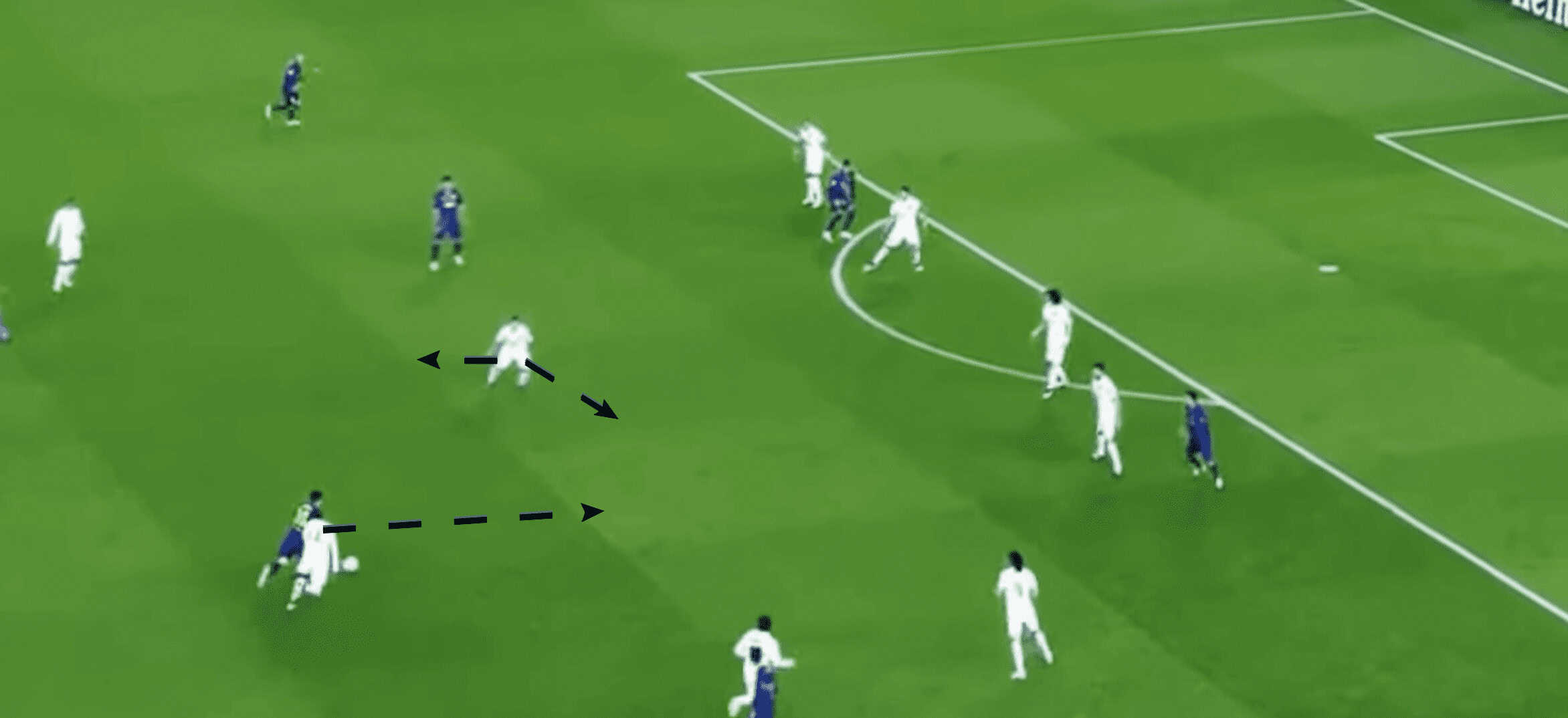

Below is an example of some excellent defensive work by Marco Verratti. With Lionel Messi advancing with the ball, Verrati, moments before, would look over his shoulder and see the position of the opposition player behind him. As a result, the Italian adjusts his body position to a “flat” one, allowing him to cut out a pass to the player behind him but still access the space to his left.

Once Messi begins to advance into the space ahead of him, Verrati approaches Messi from an angle that prevents him from playing a pass to the opposition player behind him and allow him to be in a position where he could win back the ball.

Knowing when to press.

This does not just entail the various pressing triggers that a side may have when defending but also when players begin to respond to multiple triggers. Below is an example where James Garner starts to move towards an opposition player before the pass to that player is even played.

This puts him in a position to challenge for the ball as quickly as possible.

Various factors can allow players to be able to make informed predictions on where the ball will be played as well as when. Some examples of these are cues from the opposition, such as body position, head movement, the speed of the penultimate pass, and how much time an opposition player has on the ball before making a pass.

Communication & Coordination

This is reasonably self-explanatory and something that players in a side cultivate through gaining familiarity with each other’s strengths and weaknesses. Due to the length of football matches and the physical and mental demands of the game, players will not be able to be aware of every risk at every moment. Therefore, players will need to rely on each other to express the need to cover specific spaces and opponents. This is especially pertinent when a side is shifting from one side of the pitch to the other.

How can all of this be trained?

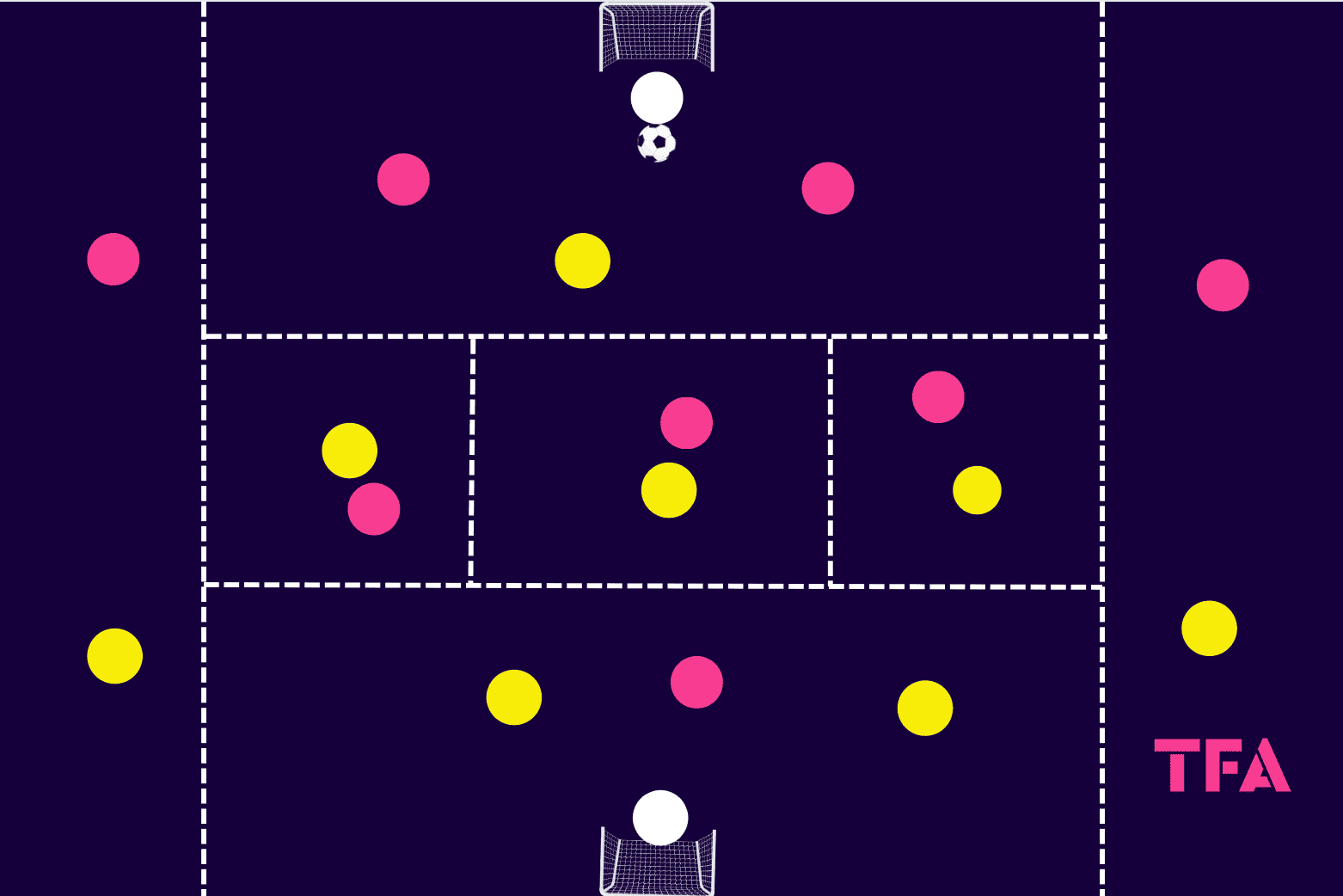

5v3 Reaction game

Pitch size: 7.5 x 15

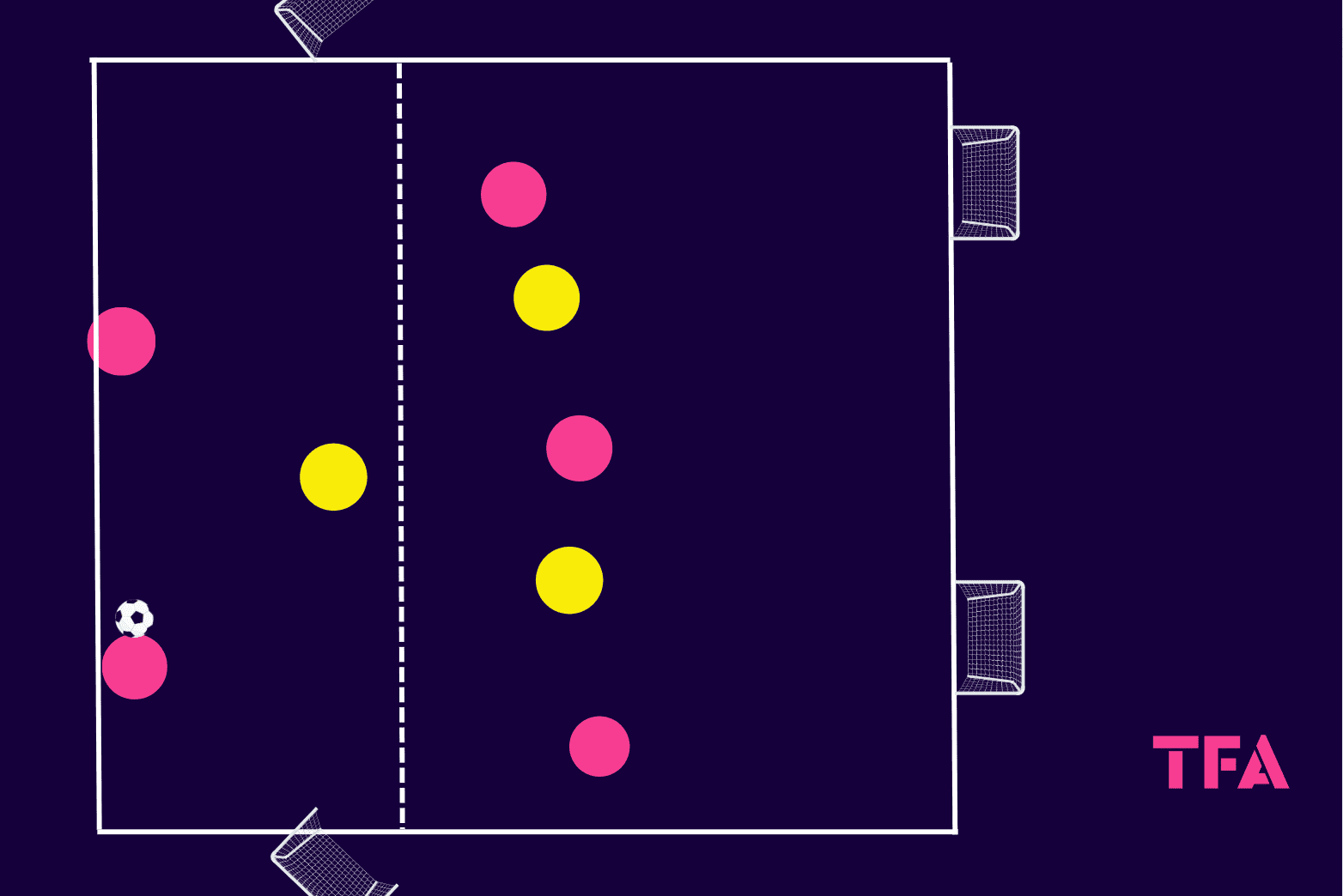

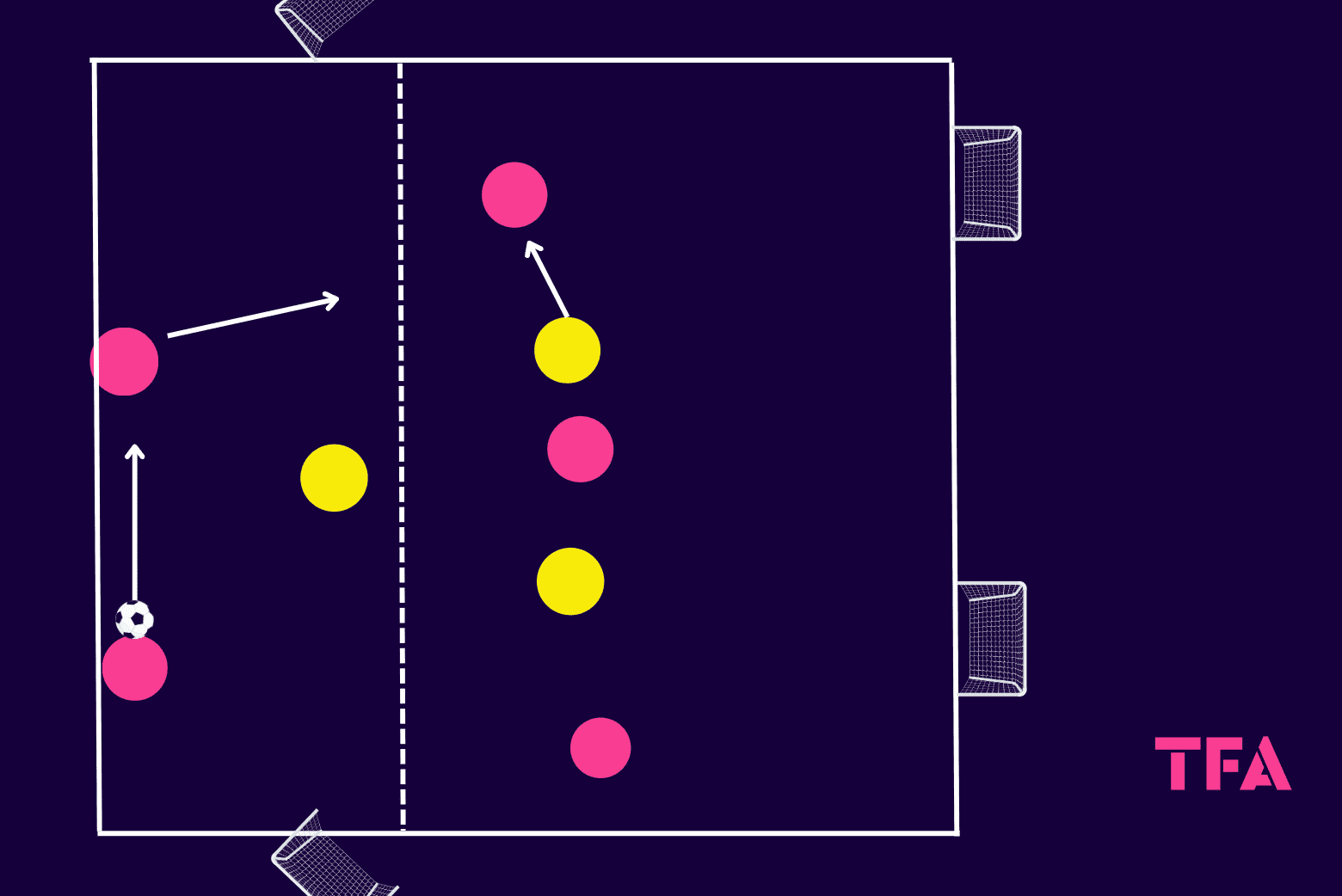

In this game, the pitch is divided unevenly into two areas, with a 3v1 in one half and a 3v2 in the other half. Players in the smaller half will have to play five passes before passing the ball into the next half, with the players receiving the ball looking to score in the mini-goals. Players from either team are not allowed to cross over into another half.

This drill is centred around awareness for the single ‘yellow’ player in one half, with that player adjusting his position to his teammates and the ‘pink’ players in the other half. The reason ‘pink’ players have to play five passes before passing into the next zone is to give the ‘yellow’ players in the next zone a defensive crutch.

This gives them an idea of when a pass will possibly be played into the next zone and gives them an opportunity to analyse cues provided by the ‘pink’ team on where they will pass the ball for the ‘yellow’ players to start moving early to cut out a pass or challenge quickly for the ball.

Another aspect that the ‘yellow’ players will need to consider is to be aware of their position in relation to the mini-goals behind them. Once they have one the ball, the ‘yellow’ team aims to play the ball into the mini-goals, with the ‘pink’ team looking to counterpress. A progression of this drill is to remove the pass requirement of the ‘pink’ team.

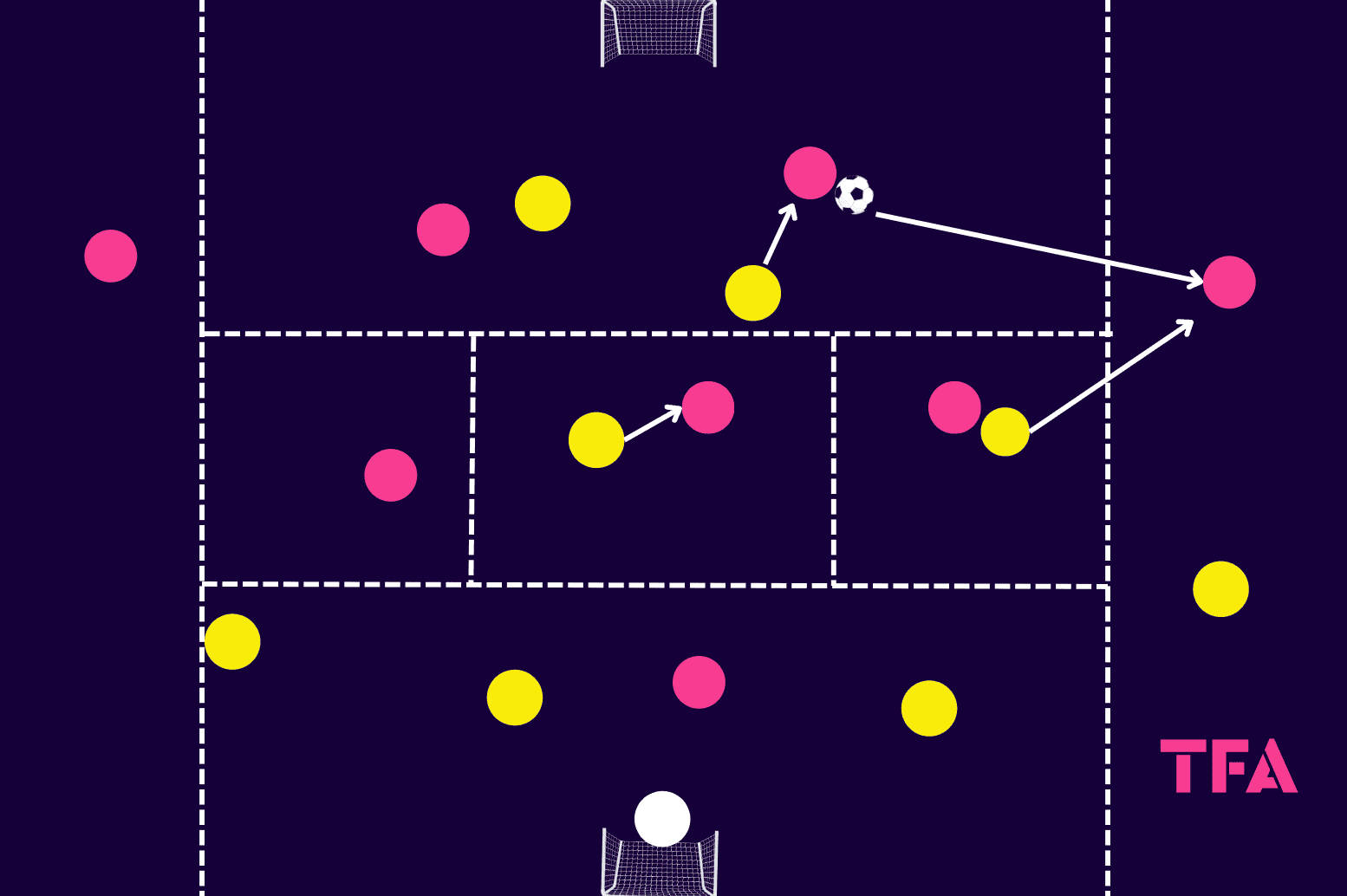

5v5 Small-sided game.

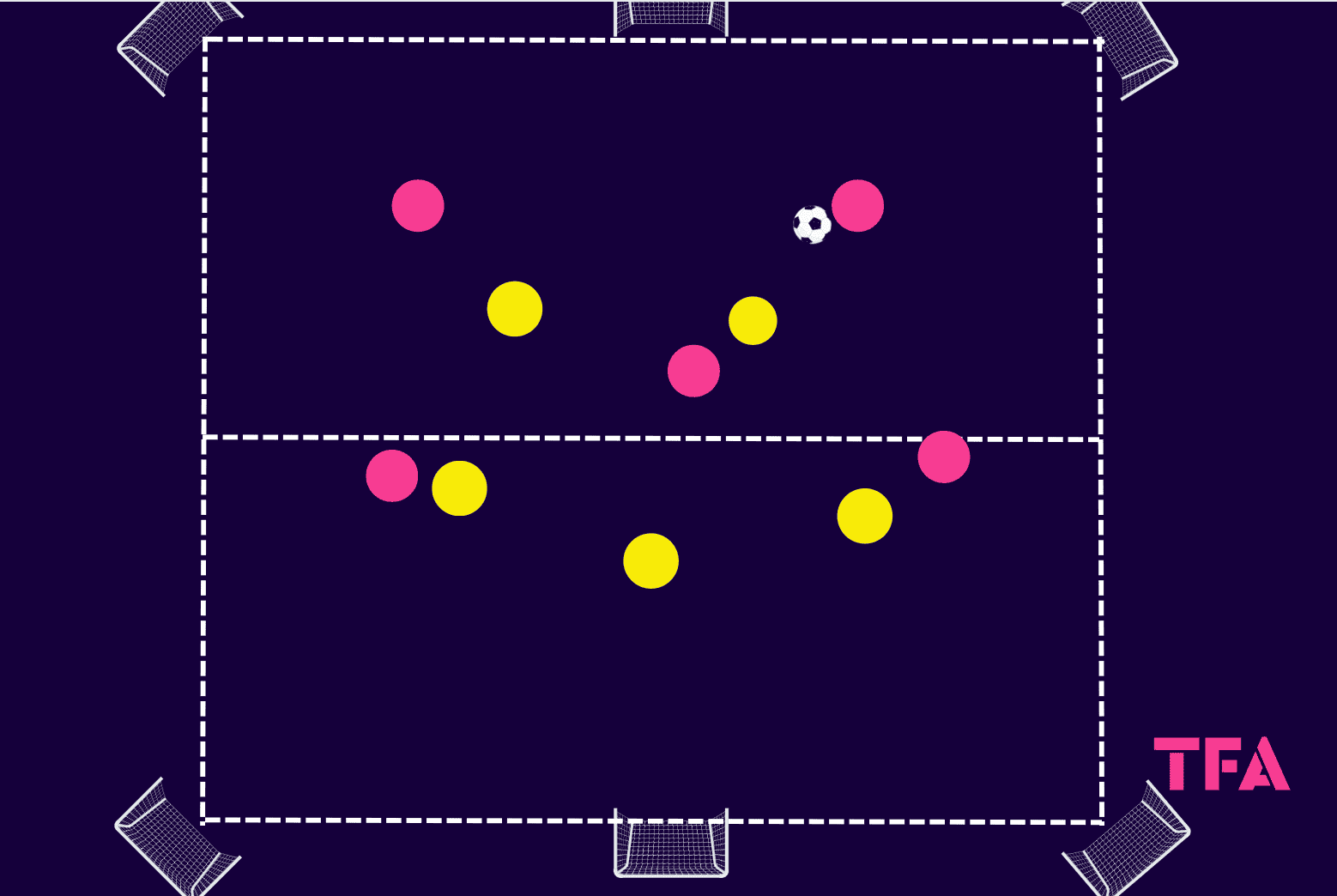

Pitch size 20×20

This is a relatively simple game, with the only constraint being that for the team in possession to play into the other half, they have to complete a one-two to do so. This aims to create scenarios where the defending players will have to press the ball carrier at an angle that prevents them from finding their teammates.

This allows for the next pass of the team in possession to be pretty predictable, with players in the defending team needing to be reminded of factors such as ball speed and cues given by the possessing team that can allow them to anticipate the next pass and regain the ball.

Besides the one-two rule, the only other rules in the game are that the team in possession score in the central goal, which counts for two goals and the team in possession cannot have all their players in one half. If the defending team wins the ball back, they must look to score in the goals on left and right, which counts for just one goal.

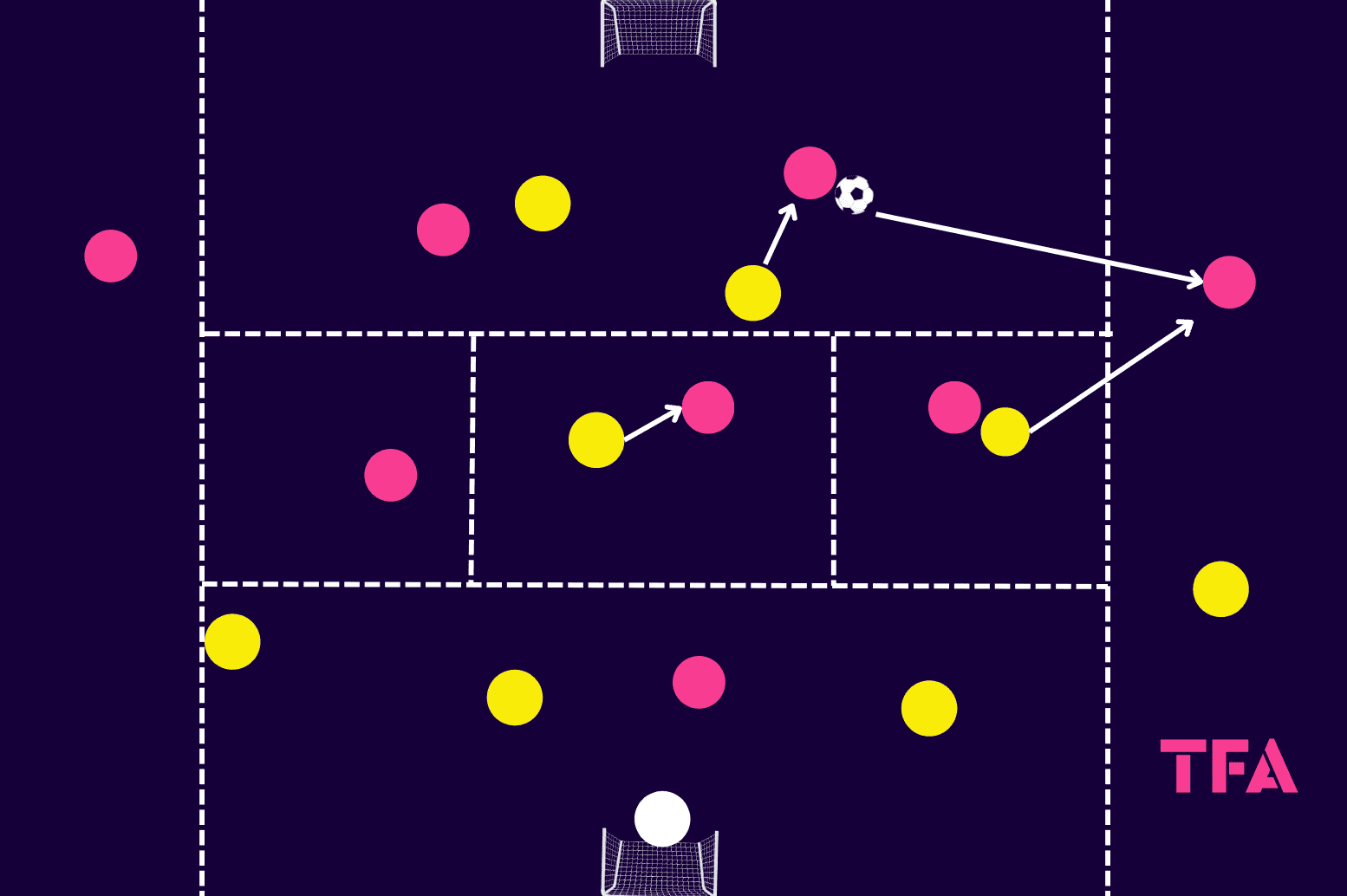

9v9 game-related practice.

Pitch size: 50×50 (but can vary depending on numbers as well as age)

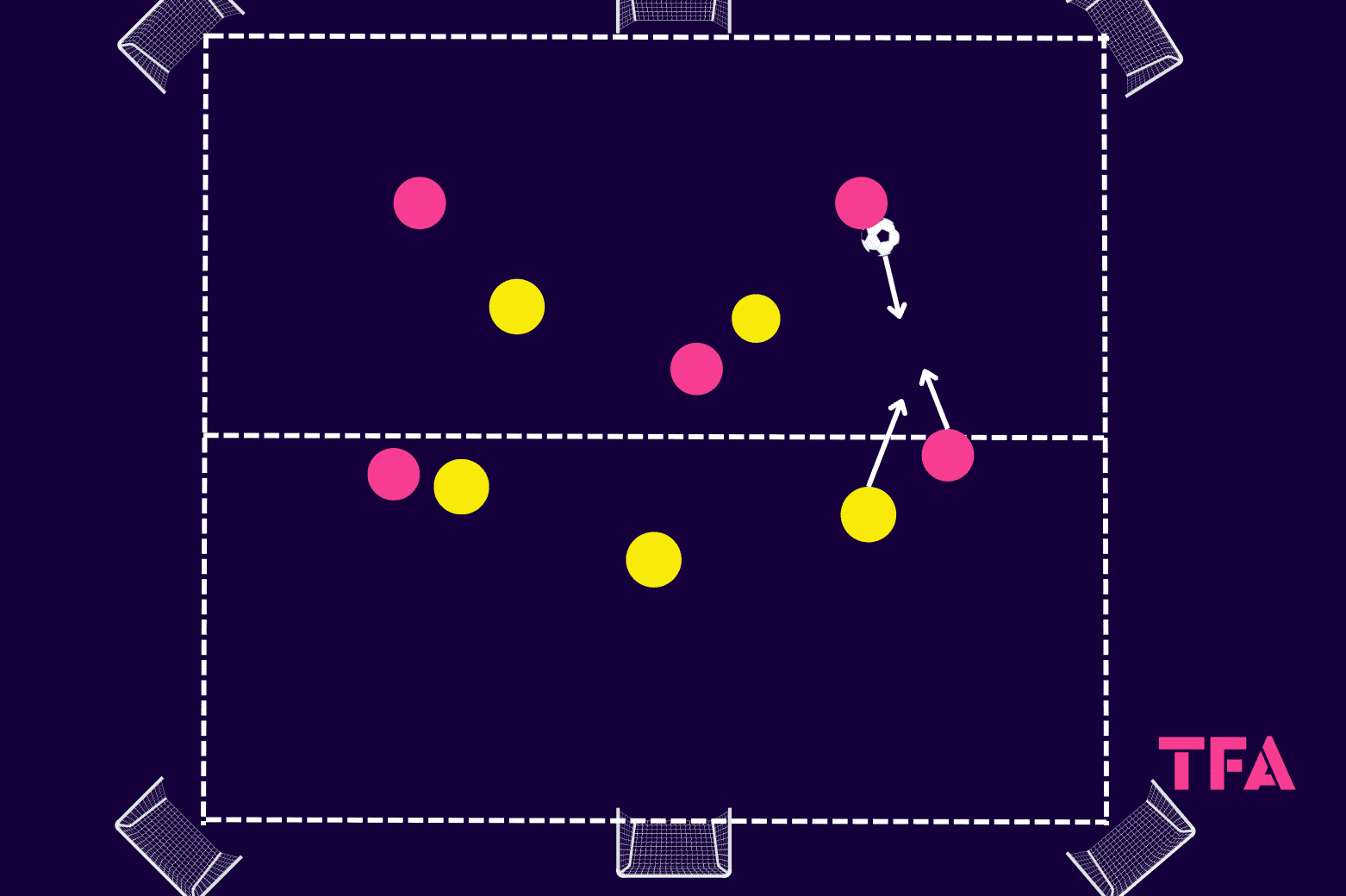

In this drill, the pitch is divided into three vertical and horizontal zones, with the central zone divided into 3. The defending team is tasked with preventing passes through the central area and directing the team in possession to the wide areas. This drill looks to focus on shifting defensively, with all of the zones acting as a guide for players when shifting and covering opposition players as well as space.

The players in the middle zone must be proactive in pressing players in wide areas and pick up on cues such as body shape on when a pass shall be played to the wide area. The drill also allows for focus on the back line, with the zones also aiding the back line in shifting from the right to the left. Players are allowed to move freely between the different zones. The aspects discussed in the previous drill are also relevant here, with the exercise looking to create a game-realistic setting.

Conclusion

This tactical analysis has shed light on some of the most important tactics and principles when defending in a mid-block and presents some ideas on how they can be trained. Through behaviours and actions such as awareness, reading the opposition to anticipate passes, communication, and coordination, players can stay compact and provide support for one another.

Comments