What Is Double Pivot In Football?

The double pivot can be a useful tactic in creating numerical superiority in the build-up phase.

It can attract opposition players towards the ball in high areas, leaving space to exploit behind their midfield line.

It can also provide stability behind the ball during the attacking phase.

The double pivot can be created in several ways.

The most common is to have two set defensive midfielders occupy these positions.

However, in recent times, top coaches have been creative with the rotations of their players in other positions to create a more fluid double-pivot system.

Ange Postecoglou and Mikel Arteta, to name but a few, have used their full-backs in inverted positions to play alongside a lone defensive midfielder.

Pep Guardiola has taken it a step further by having a centre-back stepping up to become a second defensive midfielder.

These examples emphasize the importance these managers place on having two players controlling the centre of the pitch.

This tactical analysis will use examples from De Zerbi’s Brighton and Xabi Alonso’s Leverkusen, currently top of the Bundesliga.

This analysis will use examples from these teams to highlight some of the movements modern midfielders are making.

This tactical theory will offer suggestions on how coaches can implement these tactics.

Building up with a double pivot

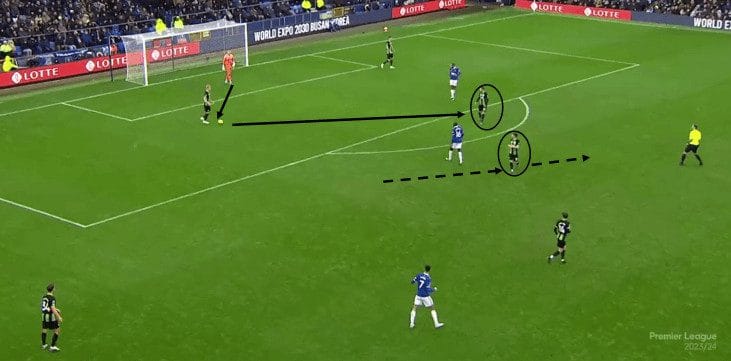

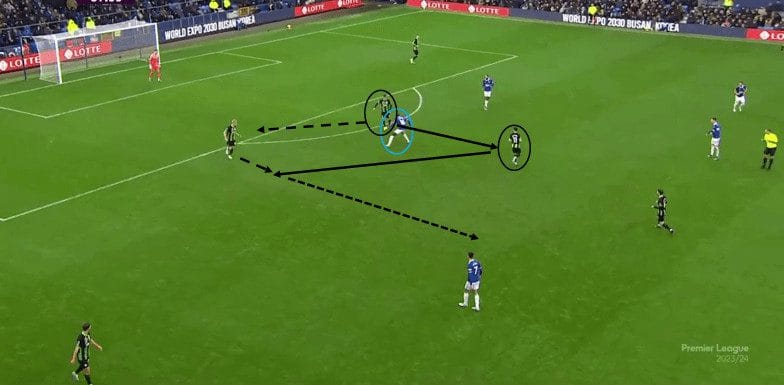

This example, from Brighton’s recent match at Everton, shows Brighton with a low double-pivot from goal-kicks.

Often, Brighton use this as a way of attracting pressure to leave space in higher areas.

Everton, perhaps more cautious of Brighton’s quality from goal kicks, kept their midfield slightly deeper to avoid creating a gap behind their midfield.

Brighton, in this example, used their double-pivot to play around the first line of pressure and clever rotations to break out of their half.

The two midfielders started close and parallel to each other.

When the ball was played to the right centre-back, Billy Gilmour, who was closest to the ball, then moved behind his teammate.

This meant Gilmour and his midfield partner, Pascal Gross, were now in a vertical straight line.

The pressing forward, who had been attempting to cut off a pass to Gilmour, now has no idea where Gilmour is.

Gilmour snuck to the inside to create a triangle around the striker.

Gross finds Gilmour, who plays a bounce pass into his centre-back.

The centre-back can now attack the space ahead of him and take Everton’s two forwards out of the game.

Gross then replaces the centre-back’s position in defence.

With their having been two midfielders low in the build-up, Gilmour is still there to support the ball as the play progresses.

Xabi Alonso’s double pivot

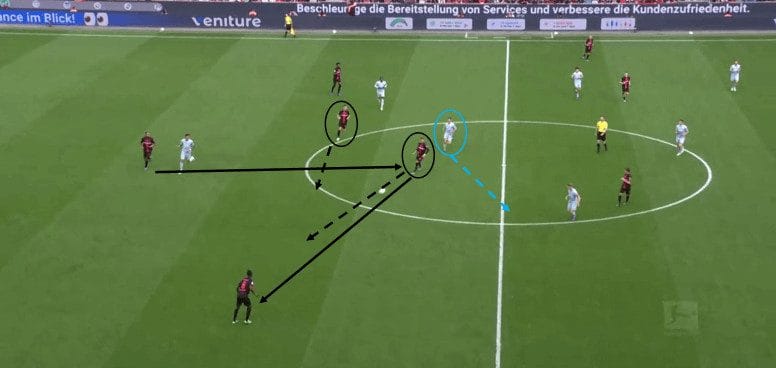

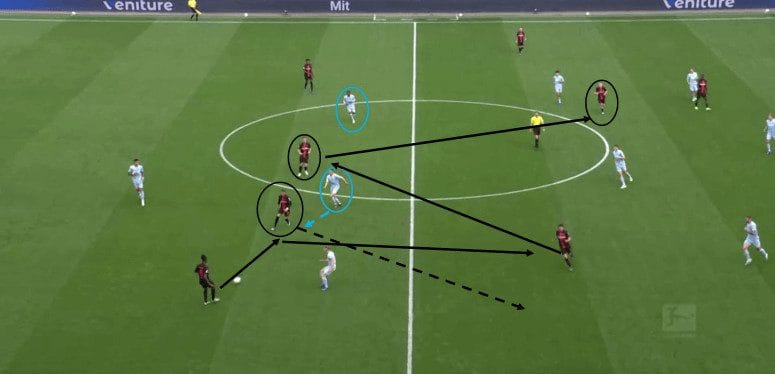

In this example from Xavi Alonso’s Bayer Leverkusen, both of his double-pivot midfielders (circled) move in perfect sync with one another.

The image shows the seconds after the ball has been played from Leverkusen’s left to their centre-back.

The centre-back has played into one of the midfielders who bounced the ball to the wider defender.

As the ball was played out to the side, both midfielders simultaneously dropped and positioned themselves low relative to the ball.

The midfielders both moved towards the ball and were very close to one another.

Typically, in these situations, you may expect one to show for the ball, with the other keeping their distance to receive the next pass.

Had the distance between the two midfielders been greater, the opposition player at the top of the image (circled) would have been positioned to cover both the ball-far midfielder and the left-back behind him.

In the positions they take up, he cannot press as this would leave his side vulnerable to a switch of play.

When the ball is played into the first midfielder, his side-on body shape allows him to play first time into his more advanced teammate.

The first midfielder receiving the ball attracted the nearest opposition midfielder.

This created the space for the second midfielder to receive a bounce pass.

The first midfielder’s movement after playing the forward pass is also important here.

As soon as he plays the ball, he runs after it.

This encourages his marker to follow him and creates even more space for his midfield teammate.

The second midfielder received facing forward and played a pass into his forward’s feet.

This phase of play led to Leverkusen’s opening goal against Köln earlier this season.

Coaching the double pivot

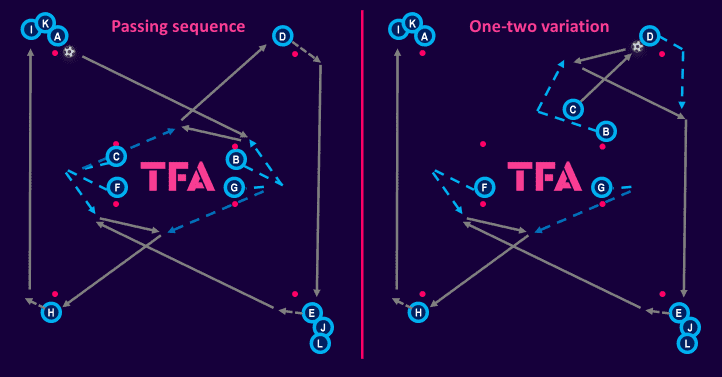

This passing exercise works on the movements of the defensive midfielders to find each other before switching the play.

It can be used as an introductory activity for a double-pivot practice or incorporated as part of the warm-up.

The ball starts with player ‘A’, who passes to B, who represents the ball-far DMC.

B makes a double movement, backtracking away and then dashing towards the ball to meet it.

B then lays the ball off to C, who has also made a double-movement to create space centrally.

C runs onto the ball and switches to D.

Player ‘D’ receives with an open body shape,e taking a touch around the outside of the cone.

Depending on the coach’s preference, D either plays a pass with his second touch or attacks the space before giving the ball to E.

The sequence then repeats itself on the opposite side of the box.

Each player follows their pass.

A variation of the sequence could be for the ball-far midfielder (B) to make a looping run around C after laying the ball off.

B would then receive the ball back from D and play a one-two.

Coaches should emphasize the importance of the double movements to create space.

The players’ body orientation, to be able to receive and play the next pass without turning or taking extra touches, should also be highlighted.

This, along with clean, quality passing, allows for a high speed of play.

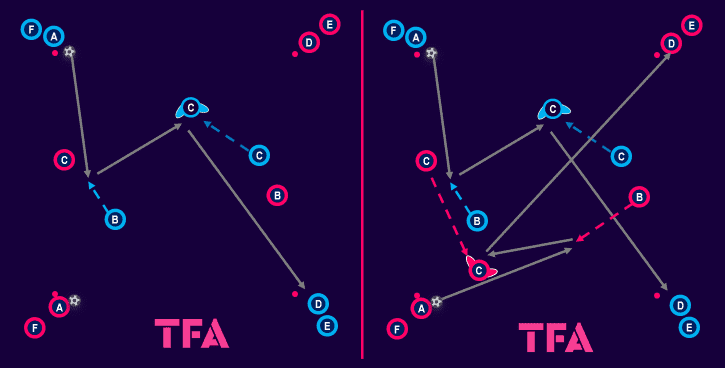

This following passing sequence is similar to the introductory activity, working on the same movements and concepts but is less prescriptive.

The exercise increases the difficulty by challenging players’ decision-making and perceptual skills.

Instead of having cones to position themselves by, the four working “DMCs” are free to move around anywhere in the square.

The four work in pairs to receive the ball from a corner player, find each other, and then play out diagonally to the opposite side of the box.

The group is split into two, with the two groups working to opposite corners of the box.

Both groups go at the same time.

As with the first exercise, to keep the sequence continuous, the players follow their pass.

‘A’ plays into one of the double pivots ‘B’.

The second midfielder, ‘C’, must then be positioned where the first midfielder can see him.

‘C’ should receive with his body positioned to play forward, without turning on the ball, to D.

After playing the final pass, ‘C’ follows the ball to join the line behind ‘D’.

Player ‘A’ then moves into the square to receive the first pass from ‘D’.

The player in the middle who plays the final pass moves to the outside of the square, and the sequence continues.

Having two balls on the go creates a degree of chaos in the middle.

This requires players to play with their heads up, not only to see their teammates but to avoid the players and ball working the opposite way.

It also provides the players with more realistic, moving obstacles to play around.

The players working in the middle should be reminded of the body orientation required to receive the ball and play the next pass without having to turn.

They should be scanning the area for their teammates and obstacles before receiving the ball.

The DMCs should be encouraged to make eye contact before playing the pass between them.

The weight of the passes is also crucial.

A firm, line-breaking pass should be fed to the first midfielder, who then takes the weight off the next pass.

This layoff should allow the second midfielder to step onto the ball and play another firm pass to the opposite side of the box.

Different movements and rotations can be included.

An example could be one player showing close for the ball, the passing missing that player out and finding the further midfielder.

The first midfielder then spins to receive a bounce pass and play forward whilst facing that way.

A shadow or full-on defender can be added to apply game-like pressure to the working players and create another level of realism.

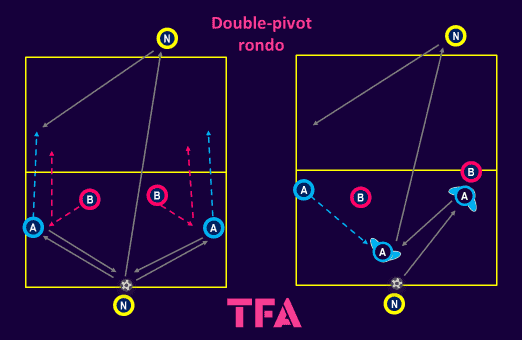

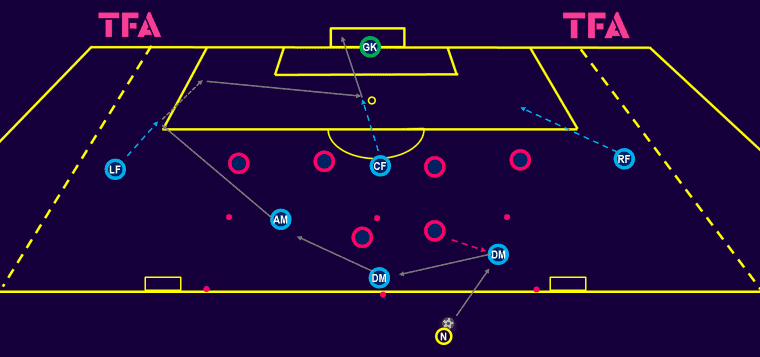

Double pivot rondo

This basic rondo set-up allows the central midfielders to work as a pair whilst being pressed one-on-one by two opposition players.

The rondo aims to progress the ball from one neutral (yellow) player to the other, either directly or via the two central players.

Once the ball is switched, both teams move to that side of the box before attempting to play back to the other side.

The neutrals on both ends can move across their line to help create angles to receive the ball.

If the pink team steals the ball, they become the working team.

The attacking team, being pressed one-on-one, must be intelligent with their movements.

They must both create separation between themselves and their marker and create passing lanes for the ball to progress to the other side.

The example shown on the left has both blue players keeping their width and playing bounce passes with the neutral end player.

Receiving the ball attracts their markers and opens a passing lane for the neutral player to exploit.

The example on the right shows one attacking player supporting underneath the other to progress the ball.

Depending on the level of the players being worked with, conditions such as one-touch passing can be introduced.

Within this set-up, the focus can also be shifted on to the defending players.

They can be coached on how, in their double pivot, they press and prevent the opposition from playing forward.

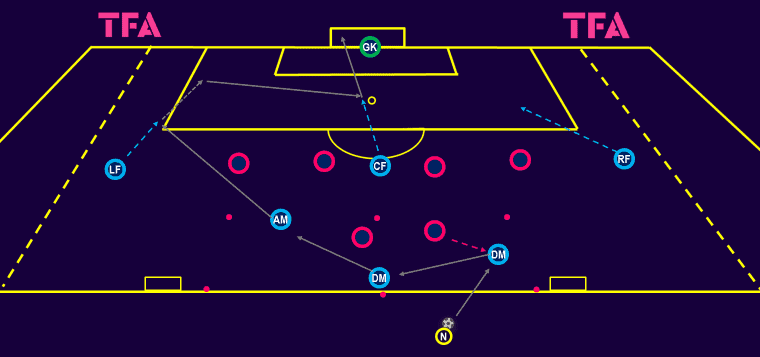

Half-pitch shape game

From an unopposed passing exercise to an opposed rondo, the session can now progress to a more game-like scenario.

This six vs six plus one begins with a rondo box, as in the previous exercise.

The two central midfielders playing in the double-pivot remain inside the box with a neutral and attacking midfielder supporting them.

The AMC does not enter the box but plays along the top side.

The neutral player, representing a centre-back in this phase, moves along the bottom line.

The four attacking players must connect a certain number of passes, dependent on the level of the player working with, before breaking out and playing a live game.

The players in the rondo, whilst allowing looking to play forward, should be patient until an opportunity to progress the ball cleanly arrives.

Once the play is live, the neutral player moves into the rondo box and remains involved in the attack.

The double-pivot supports the play whilst staying (mainly) behind the ball in positions that allow them to switch the play.

When possession is lost, the pink team attacks towards the small-sided goals on the halfway line.

The now attacking team can use the neutral player, now acting as a central forward, to combine with before attacking the goals.

Conclusion

Although a relatively new coined term, the double pivot has existed for decades in football.

The more recent developments in the system, brought on by the likes of De Zerbi and Alonso, are how the two interact and combine with each other.

Another modern trend is how these players take up different positions on the pitch to allow their teammates to move into different areas.

As with the Brighton example against Everton, this creates tactical flexibility.

Players from different positions, for example, full-backs or even centre-backs, moving to the centre of the pitch to create the double-pivot is another trend that will no doubt develop further in the seasons to come.

To create a successful double-pivot partnership, the midfielders have to be comfortable receiving the ball in almost all areas of the pitch.

They must then be coached on specific movements and have a great understanding of where one another will be.

Comments