England U21s had a very successful tournament at the UEFA European Under-21 Championship this summer. Not only did they win the championship, but England also did so without conceding a goal in the entire finals. This record was kept intact when the tournament concluded in the most dramatic fashion. Ex-Manchester City youth team player, James Trafford saved a 98th-minute penalty to both secure both the clean sheet record and win England’s third UEFA U21 Euros title.

England qualified for Euro 2023, their ninth straight finals, with victories over Czechia, Kosovo, Albania and Andorra. Their only real blemishes in the whole tournament, in qualifying and in the finals, came against Slovenia. Slovenia drew 2-2 at home with the young Lions before beating them in Huddersfield 2-1. Although this defeat came after securing qualification, it would have hurt being the match that broke their 54-game unbeaten run in qualifying. This record stretched back to November 2011.

This tactical analysis will focus on how England, managed by ex-Premier League and Everton star Lee Carsley, build-up from the back. This tactical theory and analysis includes a section providing examples of how to implement these tactics on the training field.

Goal Kicks

This section is going to analyse goal-kicks that are taken short and after the opposition has been able to organise their defensive setup. Throughout the tournament, goalkeeper Trafford would play out quickly before either team was in a well-defined setup. When the team were prepared, the favoured option appeared to be to play short, but England also often went long.

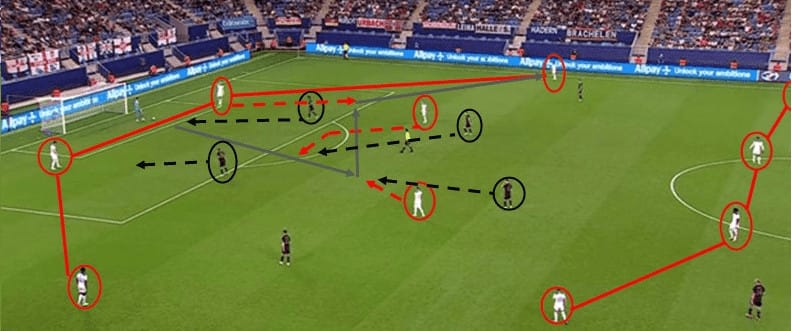

The above image shows England’s 4-2-4 structure, which sometimes became a 4-2-2-2, against Germany. England’s left centre-back took the goal-kicks from the corner of the 6-yard box, passing to the centrally positioned Trafford. When playing against two high-pressing forwards, as in this example, it means if one of the two forwards presses the ball, one centre-back becomes free.

In this build-up scenario, England’s aim appears to be to bait Germany down one side (England’s right) before switching it out the other way. When the ball is played to Trafford, he shapes to play to his right whilst being pressed in that direction by one of the forwards. Thinking they have trapped England down one side, Germany’s left-forward is poised to press the right centre-back and starts creeping towards him.

This movement by the forward provides enough room for the ball-far central midfielder to move towards and receive the ball. This central midfielder is supported underneath by his midfield partner. The supporting movement achieves two things. Firstly, it gives the player on the ball a passing option without having to turn on the ball. He would have been facing up the pitch if the second midfielder had received a pass.

This movement’s second outcome was attracting Germany’s right-sided central midfielder into the opposite side of the pitch. This made Germany’s central forwards and midfielders all very lopsided and opened up England’s left. Instead of laying back to his midfield partner, the midfielder on the ball switched the ball to his free centre-back, whose marker had jumped to press Trafford.

The result of this switch of play is England’s left-back receiving and being able to progress with the ball relatively unopposed into the middle third. The front four that have remained positionally disciplined in the build-up are now man for man on Germany’s back line.

Goal-kick adaptation and recovery

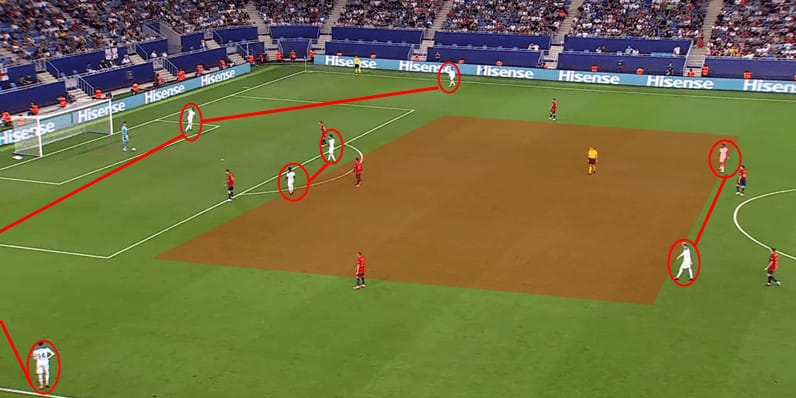

The above image shows an England goal-kick in the final against Spain. England made subtle adaptations to their positioning for goal-kicks in this match. The left centre-back still took the kick and was positioned inside the box. The opposite centre-back, however, was moved to the outside of the penalty area (just out of shot).

This made it more difficult for the two forwards of Spain to cover both centre-backs. Both forwards could not position themselves parallel or even within pressing distance of each centre-back. If they had, they would have opened it up for one of England’s two central midfielders to get on the ball.

England setting up with two midfielders deep at the edge of the box (they had done this in previous matches) could have been a ploy to attract more Spanish players towards the box. This could be done to create more space for the two players in advanced central positions. These tweaks meant that England were structured in more of a 4-2-2-2 than 4-2-4.

In addition to the positioning allowing England to play out, it also had a secondary benefit. England had more defensive security by having more players in or around the box, should they lose the ball.

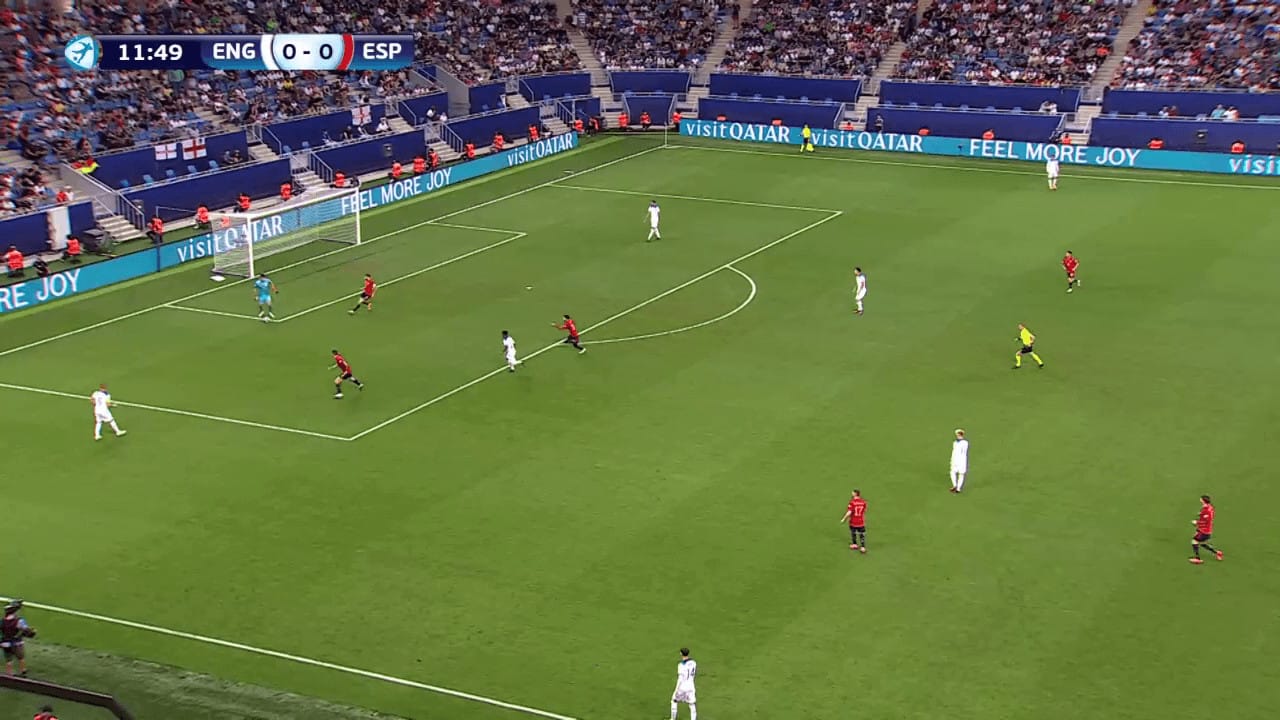

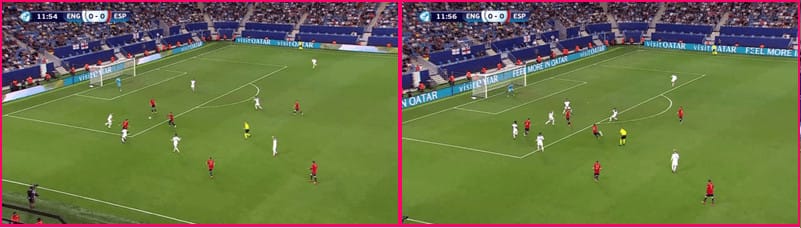

Spain caused England the most problems in the tournament by the way they pressed goal-kicks. Almost all of England’s 13 goal-kicks in this match resulted in a turnover of possession in Spain’s favour.

In the above example, from England’s first goal-kick of the match, Spain trapped England very well by forcing Trafford down one side and then covering all passing options. With Spain’s right forward closing him down, Trafford attempted to clip the ball into his right-back, but Spain’s left midfielder intercepted the pass.

The above images show the seconds after England’s goalkeeper lost possession of the ball. When the ball came back at them, England had just two players behind the ball. With the ball at their feet, Spain had three players in or about to enter the box. Within seconds of losing possession, England had blocked off the goal and forced a shot from outside the box. Although still dangerous, the xG dropped significantly by England’s quick reactions, not allowing Spain to enter the penalty area.

Midfield Dynamism

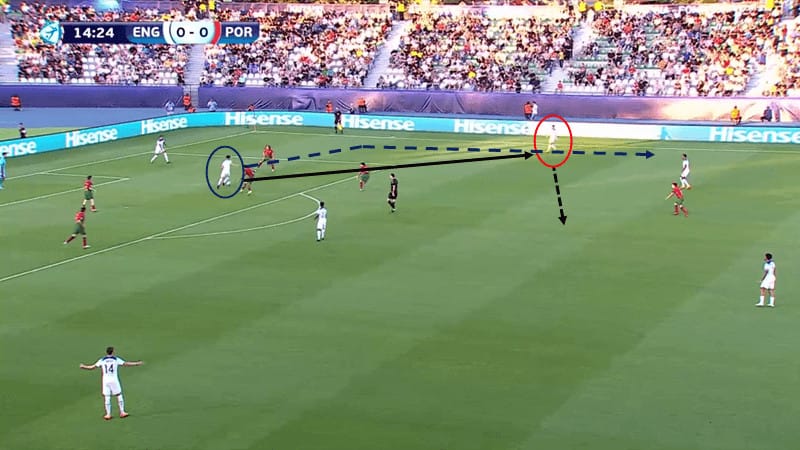

Another impressive aspect of England’s build-up play is the dynamism of their movements when they progress the ball. In the above example, defensive midfielder Curtis Jones is circled in blue. Circled in red is left back Max Aarons. Jones has just received the ball from Trafford and is about to play it out wide to Aarons.

Once the ball is played, Aarons receives and dribbles inside the pitch. Instead of moving back to a more central area, Jones overlaps Aarons rather unorthodoxly. The Liverpool star’s movement helps to keep the central area clear for his left-back to run into with the ball. It also means after Aarons has released the ball, he can remain inverted, with England in the same shape, keeping him involved in the play. This rotation of positions prevents England from slowing down their build-up by having to re-arrange players back into their original positions.

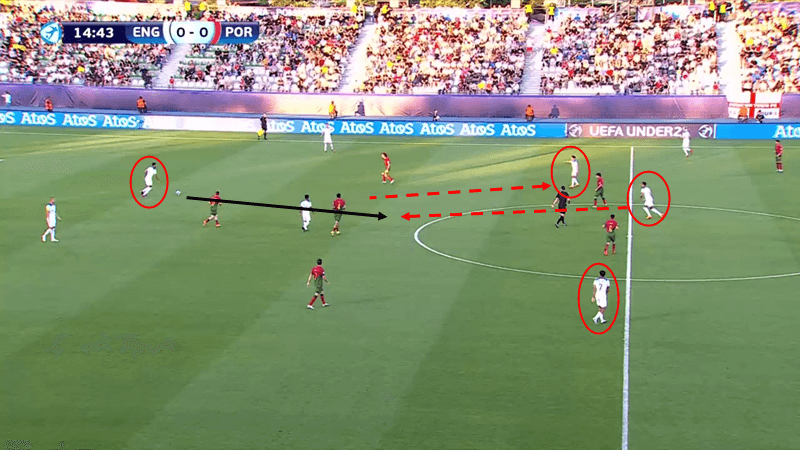

Having played the ball back to his centre-back, who can now receive it comfortably, instead of reverting to his starting position in the wide area, Aarons remains central. Similarly, Jones has now become a de facto left-back (top of image)

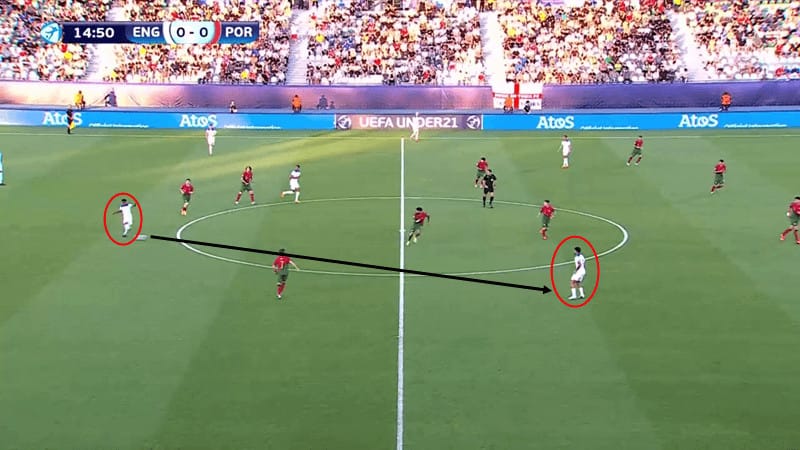

Aarons then backtracks to a more advanced position to create a gap between Portugal’s two defensive midfielders and their front four. At this point, England have effectively gone from a 4-2-2-2 into a 4-3-3 whilst the ball has been moving. Jacob Ramsey, positioned as the striker, then darted from the defensive midfielders’ blindside into the space created by Aarons.

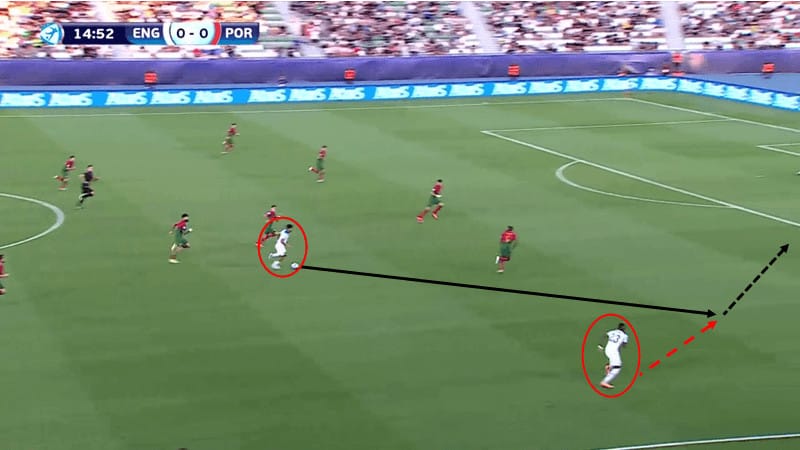

Having attracted players towards him, Ramsey dropped the ball back to his central midfielder, who found #7 Morgan Gibbs-White in the right half-space. By Gibbs-White not getting drawn towards the ball, he could receive on the outside of Portugal’s shape and beyond their midfield line.

Gibbs-White then attacked the space ahead of him with the ball before playing his right forward in behind. Here, the positional discipline initially of Gibbs-White, allowed him to receive in a difficult position to defend against. Then, the patience of his wide forward kept the Portugal defence pinned back and eventually allowed England to exploit the wide areas. This style of build up, which is very enjoyable to watch, can only be described as a mix of very dynamic movements coupled with positional play.

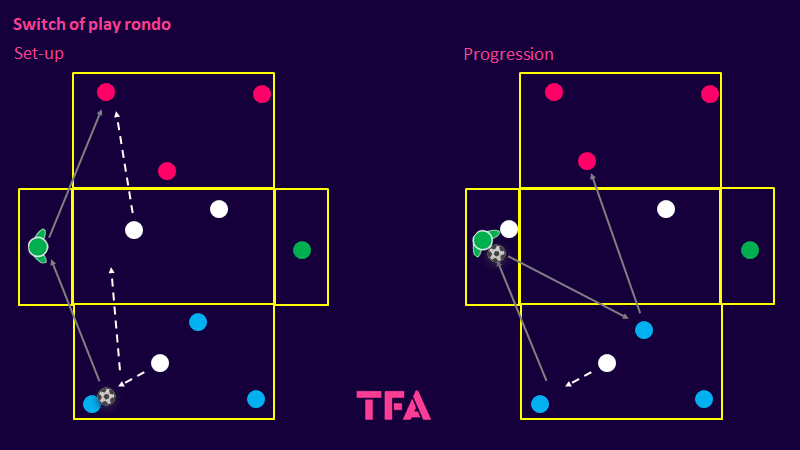

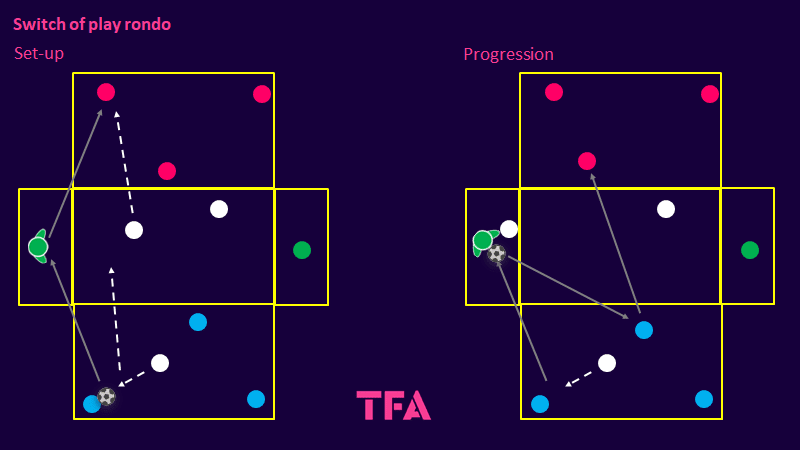

Switch of play rondo

A key component for teams during the build-up phase is often to swing the ball from side to side. This can be to either stretch the opposition and penetrate centrally or to create space in one of the wide areas and attack down the sides.

This exercise allows teams to work on switches of play in a much-condensed area and to recognise triggers of when to play forward. The rondo contains three boxes of equal size, with two additional rectangles on the side. The rectangular boxes represent the wide areas with full-backs occupying each of them.

The central box contains two defending players, with an additional defending player entering the in-possession team’s box. The three players in the in-possession box could represent two central defenders and a defensive midfielder. The “full-backs” in the side boxes play for both in-possession teams.

The aim of the rondo is to connect a certain number of passes, before passing into a wide player, who then progresses the ball to the opposite box. When the ball is switched, the first pressing player returns to the middle box, and a new pressing player enters the opposite box. Each team defends for a pre-determined amount of time.

Initially, the wide players are unopposed but must switch the ball within two touches. The progression for the rondo is for the defending team to be able to press the wide players. If the wide player is dispossessed or prevented from playing the ball forward, he can now bounce it back into the square it came from.

Once the ball has been played to one full-back, if it comes back, they have two options. They can quickly switch to the other side if the opposite full-back is open. Alternatively, if the defending team has become stretched, they can play a line-breaking pass through the middle box.

This now means that the attacking team has more decisions to make and must be more aware of the defenders positioning. They have to decide whether they should continue circulating the ball, switch it or play a line-breaking pass through the middle.

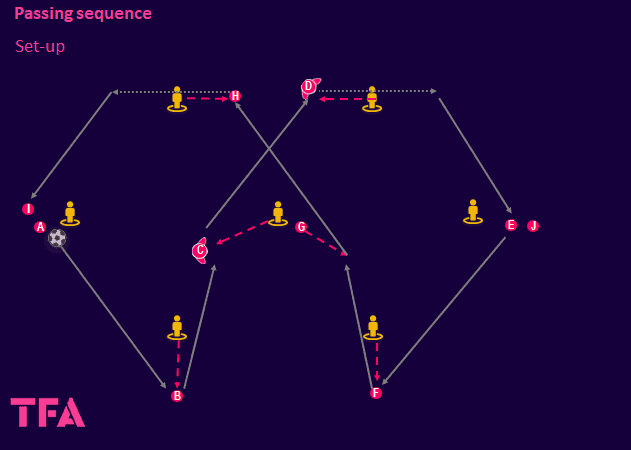

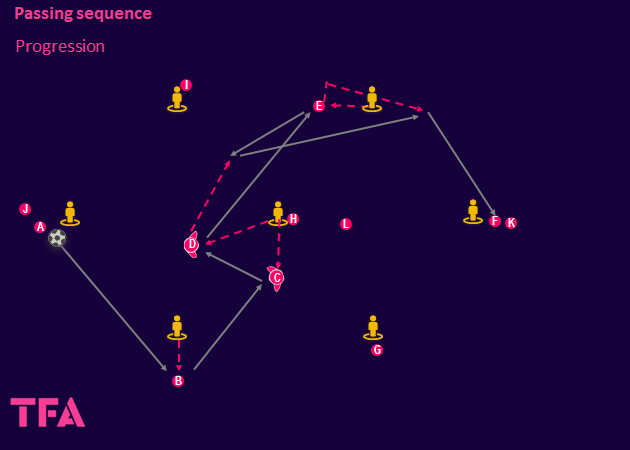

Passing Sequence

This unopposed passing sequence allows players to work on patterns of their build-up play. The exercise is set up with two diamond shapes, moving the ball in a continuous loop. Two balls, starting at either end of the diamonds, can be used at one time.

The player starting on the ball could represent the goalkeeper passing to his centre-back, who then passes to his defensive midfielder. The defensive midfielder then switches the ball out to either a central midfielder in the half-space or an inverted full-back. The passing sequence initially begins with players passing from A to B to C, etc. and following their pass.

At this stage, players should be encouraged to play quickly and receive the ball with the correct body orientation, i.e. facing forward. They should receive each pass with their back foot. Every player should move off the mannequin before receiving the ball so as not to receive standing still. The trigger for this movement is the player’s first touch before them.

The setup of this passing exercise allows for many progressions. Several patterns can be implemented to fit the coach’s needs. As in the example above, two midfielders can be used on either side of the sequence. Adding a second midfielder allows the central midfielders to combine and practice movements that will enable them to progress the ball whilst facing forward.

One-two’s and overlaps can be added. Just as with England’s youngsters, this passing sequence can encourage dynamic, free-flowing movements and positional discipline and patience. Shadow or full defenders can be introduced to the middle to give an element of realism and test the players’ decision-making.

Conclusion

In a possession-based system where players are expected to receive the ball in their own box during the build-up phase, individual technical abilities are obviously vital. It requires capable and brave players to receive the ball in tight areas and often near their own goal. It also takes a lot of work on the training ground to ensure the players understand where they should be positioned.

The dynamic movements and rotations of players often look free-flowing and improvised, but they are usually pre-determined. When implemented correctly, it can be challenging for opposition teams to position themselves to thwart attacks. As well as drilling these movements into the players, they must also learn how to react when things go wrong. Losing the ball is inevitable at some point. England U21s were excellent at making sure losing a goal from these transitions was not also inevitable.

Comments