For over a decade, Luis Suárez has been one of the most prolific forwards in world football. Many remember his heroics for Liverpool. He was instrumental in Brendan Rodgers’s side that came all so close to winning the Premier League 2013-14, scoring 31 league goals that season. The South American then went on to score almost 200 goals in six seasons with Barcelona. It was there that he formed the formidable trio beside Messi and Neymar.

In Saurez’s most recent season, at 36 years old, he scored 26 goals for Grêmio in Brazil’s Serie A. He led his side to a second-placed finish in the league as top scorer in the division. He was also awarded the Bola de Ouro as the league’s best player.

This tactical analysis will analyse the goals and movement of Luis Suárez when scoring for his most recent club, Grêmio. This tactical theory will offer analysis and suggestions on how coaches can work on Suárez’s movement and tactics with their own players.

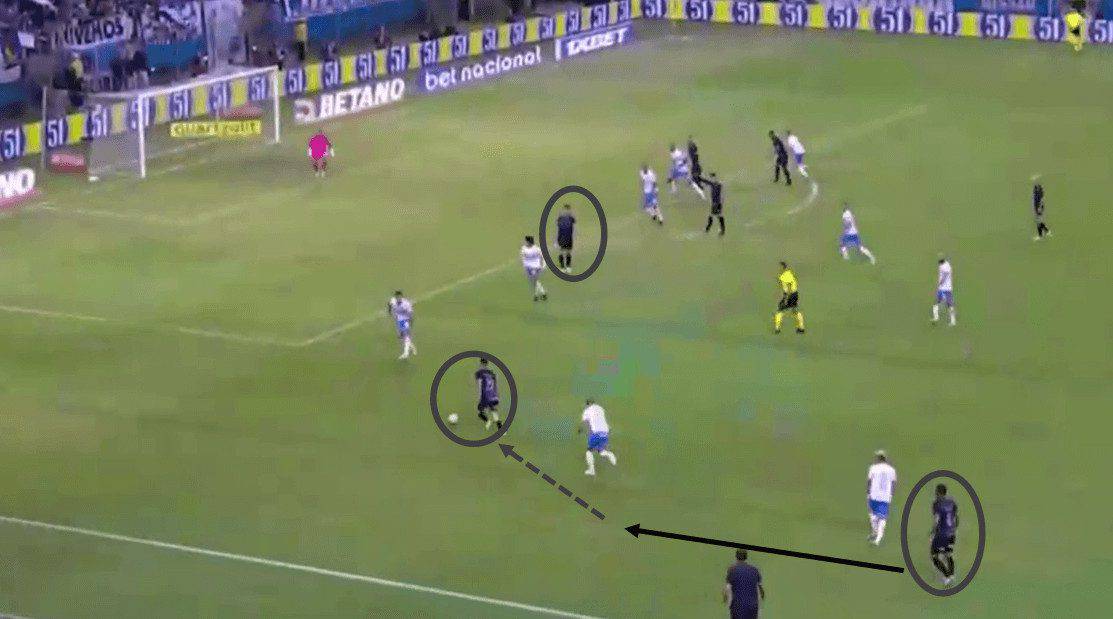

Receiving in-behind

The above image shows the build-up to what many will consider a typical Suárez goal- darting onto a slide-rule ball inside the box followed by a deft finish. Suárez’s football intelligence, especially in these moments, is what makes him so dangerous in and around the box.

In this scenario, the ball has just been played from a free-kick into his winger, who dribbles towards the opposition full-back. As defenders shift across the pitch to cover each other, Suárez stands still. This results in him being left alone between two defenders.

As his teammate cuts inside with the ball, Suárez makes the slightest movement to his left (away from goal). When the centre-back moves to block this passing path with lightning speed, the forward changes direction and bursts into the box. It is his side-one body orientation, with his hips pointing to the side of the pitch, that allows this quick change of direction.

Another trademark of Suárez’s is his first-time finishes. Here, the goalkeeper reacted quickly to the through ball and rushed off his line to narrow the angle. Whilst the goalkeeper was still moving forward and not set for the shot, Suárez slotted it past him first time. In similar situations, where the goalkeeper is in his set position, the forward has taken a touch to change the angle of the shot. This forces the goalkeeper to move his feet before attempting to dive at the ball.

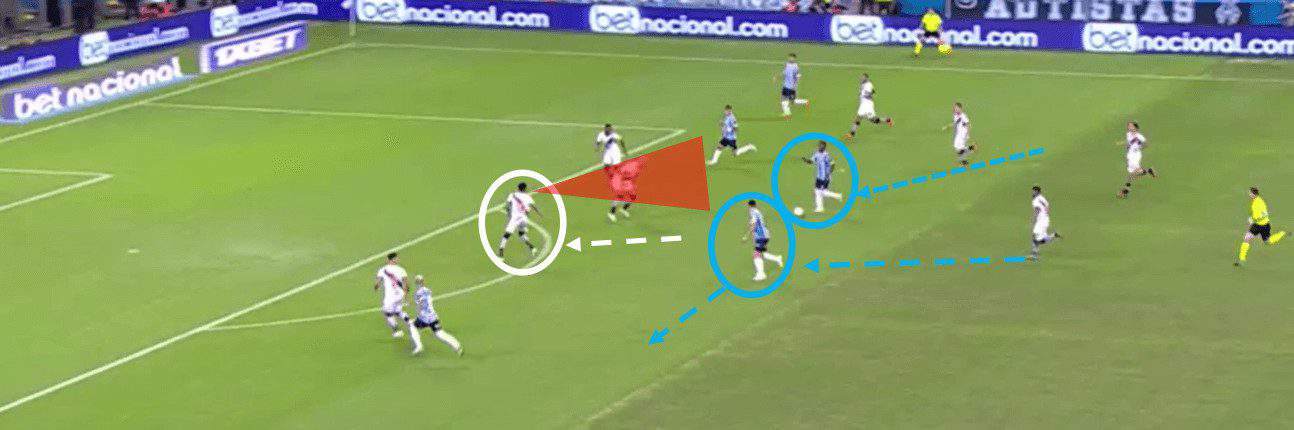

Receiving in front of the defence

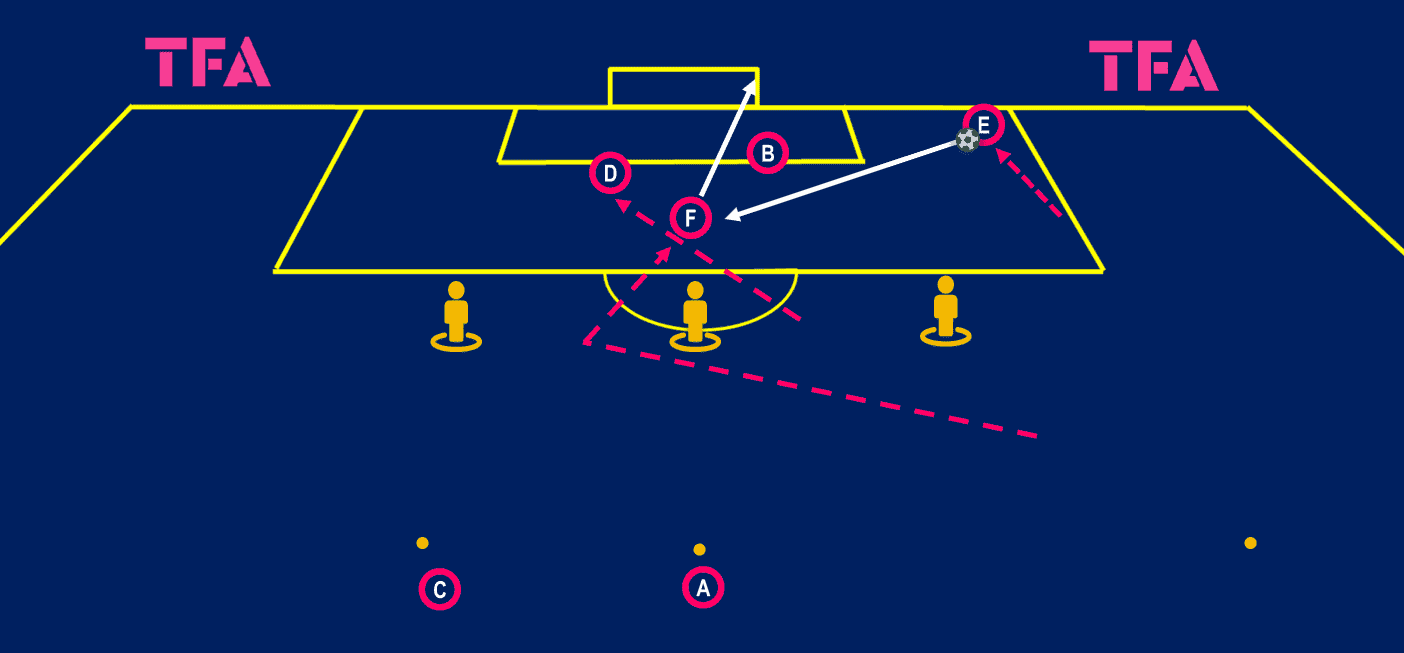

What makes Suárez the complete striker and a nightmare for defending players is that he can finish in all kinds of ways and scenarios. The above image shows a goal Suárez scored from outside the box with the opposition trying to prevent the slide-rule ball.

In this example, Suárez threatens to run in behind as his teammate dribbles with the ball towards the opposition’s backline. The backline drops back to protect the space behind them, leaving Suárez alone. As the defenders backtrack, Suárez then adapts his run to move sideways rather than forward. With the centre-back responsible for Suárez now focused on the ball, this movement takes the forward out of his line of sight.

The sideways movement also allows the pass to be received with a side-on-body shape. This body shape makes the first-time shot possible, which appears to catch the goalkeeper by surprise. The goalkeeper, whose view of the ball is blocked by his defenders, was shifting to his right to be in a more central position. The early striker meant he had to suddenly change direction and dive to his left, as his feet were taking him right.

Although the goal belongs to Suárez, his teammate continuing his run into the box after playing the pass plays a huge part. This run prevented the centre-back from stepping up to apply pressure to the ball. Otherwise, Suárez could have fed in his midfield teammate.

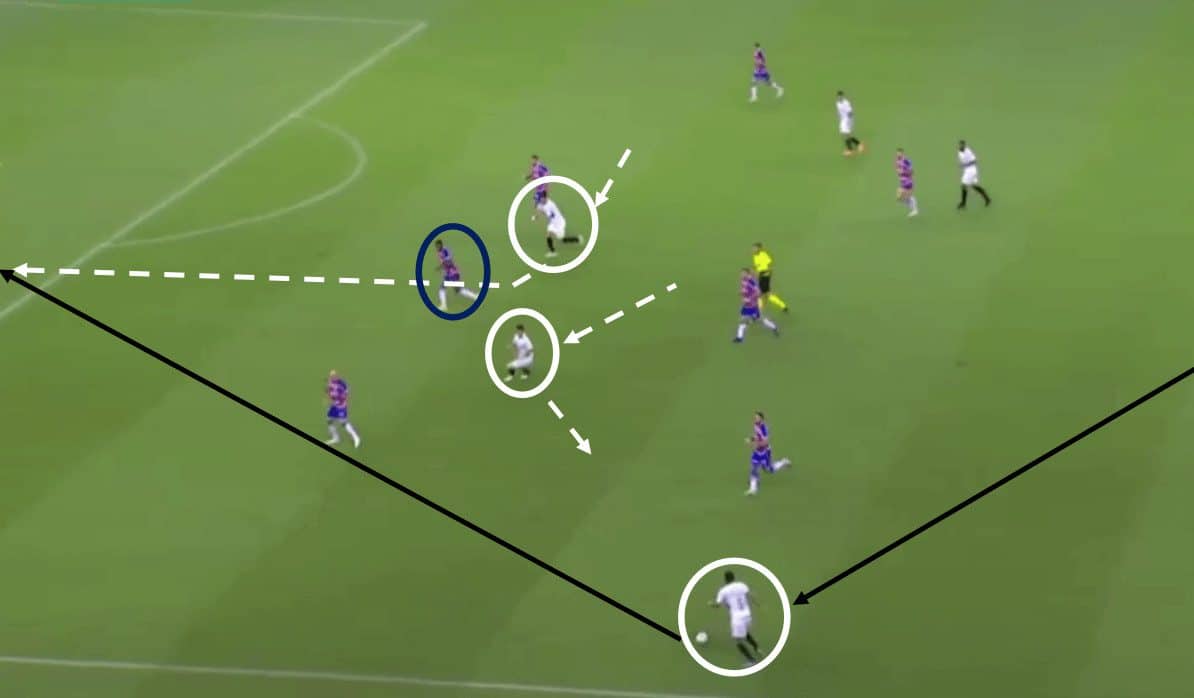

Runs in behind from deep

The image above shows Saurez’s movement when the ball is in deeper areas, and the opposition’s backline is further from their own box. As the ball is travelling from one side of the pitch to the other, Suárez runs across the backline before making his run in behind the ball-near centre-back.

The initial, slower movement across the backline is to keep the striker onside before he darts in behind. The trigger for his change in speed and direction is his wide-forward teammate’s movement towards the ball. The wide-forward circle makes the slightest of movements to show for the ball, which is enough to distract the ball-near centre-back. Suárez then sprints behind the stuttering defender.

The timing and speed of these movements are vital. When the ball is played wide and Suárez is moving across the line, he mustn’t run too fast. Otherwise, when the ball is eventually played into him, he would be further wide of goal with either a tougher or non-existent angle to shoot from.

The sharp run, away from one centre-back and behind another, creates ambiguity between the defenders. For just a split second, it is unclear who is to mark him. The timing of his sprint must be as his teammate has moved towards the ball and just before the ball is played. This allows him to run on the blindside of the distracted ball-near centre back, who, due to the proximity of the ball, must keep his eye on it. It also stops him from drifting into an offside position.

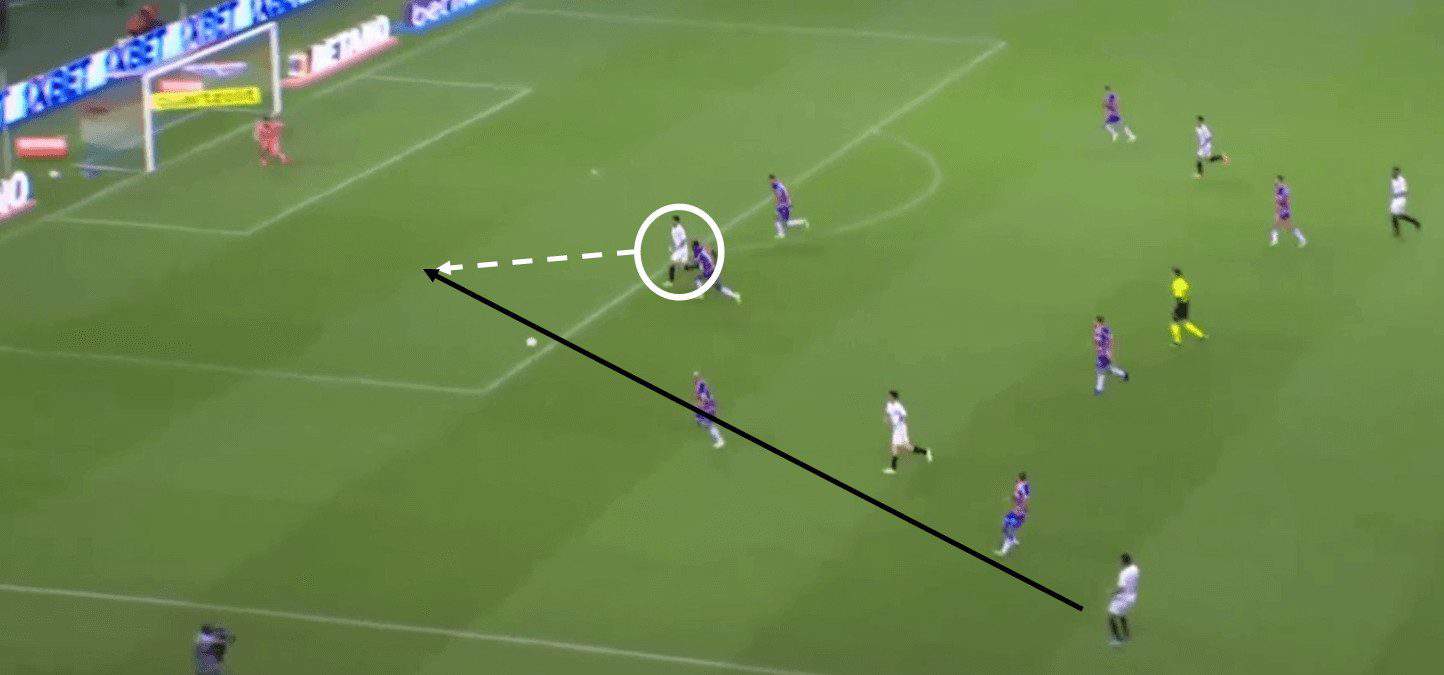

Drifting to the far post

The above image shows the build-up to a goal where Suárez scores from drifting away from his marker towards the back post area. As the image shows, Suárez begins in a central starting position. Initially, when the ball is played wide, he makes a straight run, in line with the penalty spot from the middle third towards the box.

As his teammate cuts inside with the ball and enters the box, Suárez drifts wider, creating greater separation between himself and the nearest defender. As the image shows, all the opposition defenders are fully focused on the ball as he widens his movement.

As the defenders get drawn closer and closer to the ball, Suárez keeps his discipline remaining in the space. His angled body shape and (relatively) wide positioning allow him to step onto his teammate’s pass with a clear view of the goal. In an 18-yard box containing six defending players plus a goalkeeper, he receives the ball within a 10-yard radius of space. From this point, it is his technical ability and calmness of thought that allows him to put the ball past the goalkeeper.

When the final pass was made, not a single defender had eyes on the forward, and none knew where he was. This is a common scenario he creates. When having put the ball in the net, defenders are left looking at each other, questioning whose responsibility it was to pick the goal scorer up.

Finishing Exercise

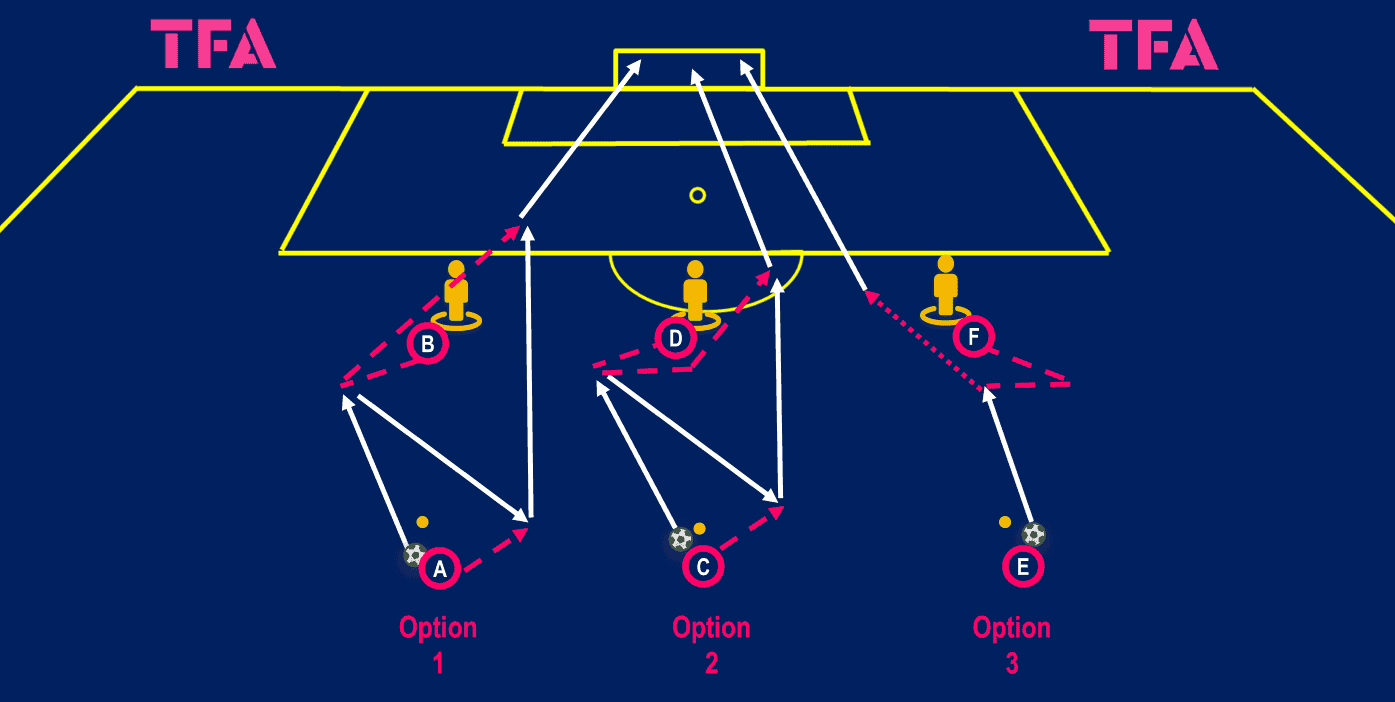

This unopposed shooting drill takes part in two phases. The first phase concentrates on finishing repetitions, with the second phase incorporating combination play. At the beginning of the exercise, players are provided with a variety of individual movements that lead to shots at the goal from different angles and distances.

The diagram above gives three examples of basic movements that can be performed in the lead-up to a shot at goal. The first option is for the striker to move off his marker at an angle towards the ball. The striker plays a bounce pass before being fed in behind. The striker’s movement to receive is on the blind side of the defender, whose eyes would be focused on the ball.

The second option involves another bounce pass. This time, however, the striker makes his run across the defender after laying the ball back. This is to work on blocking the defender’s path to the ball and prevent the defender from intercepting it.

For the first two options, the strikers have the option of whether to shoot first time, as Suárez is renowned, or to take a set-up touch. The forwards should be encouraged, via a side-on body shape and scanning, to be aware of the goalkeeper’s positioning. If the goalkeeper is set for a shot by the time the striker runs onto the ball, the striker can be instructed to take a touch. The touch should change the angle of the shot and force the goalkeeper to have to move his feet before diving.

For the third option, the striker angles off before receiving the ball in front of the defender. The striker, with a side-on body shape, then punches the ball through themselves before shooting. The pass is played directly in front of the defender to encourage the defender to jump at the ball and leave space behind. Alternatively, the striker to take a touch across the defender, assuming the defender did not jump, and shoot from outside the box.

Combination play

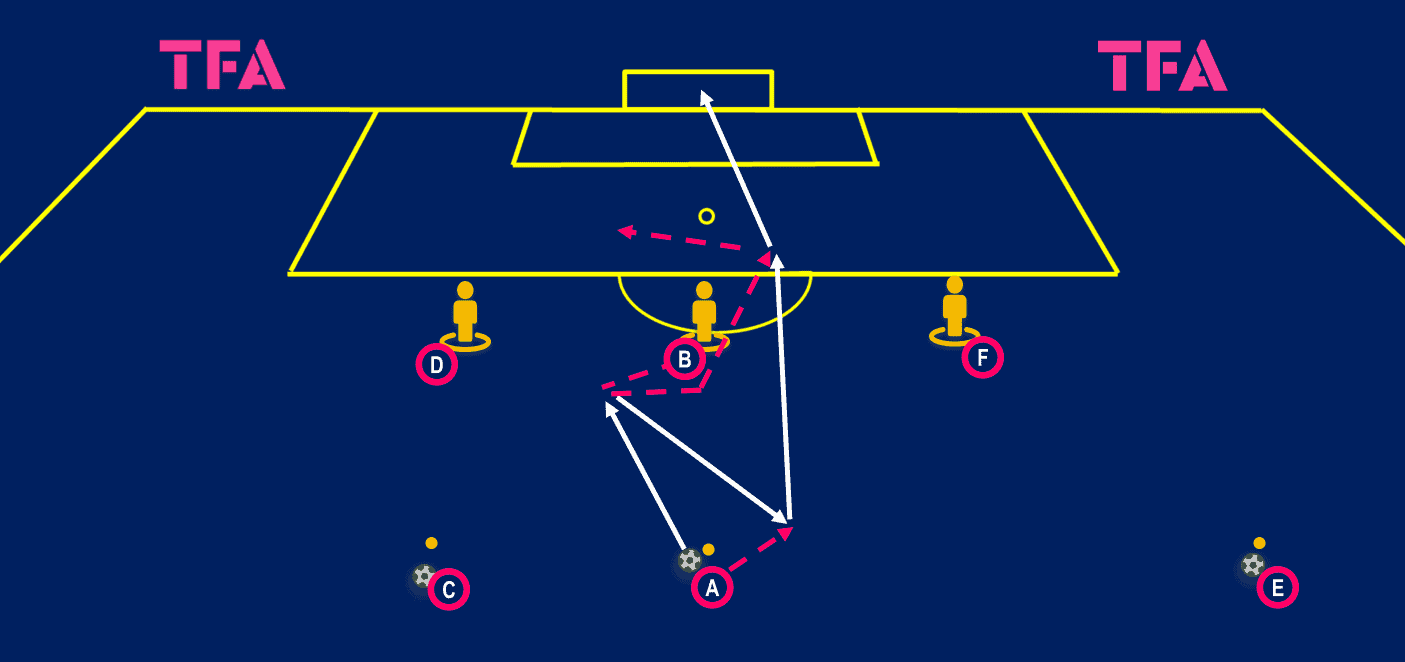

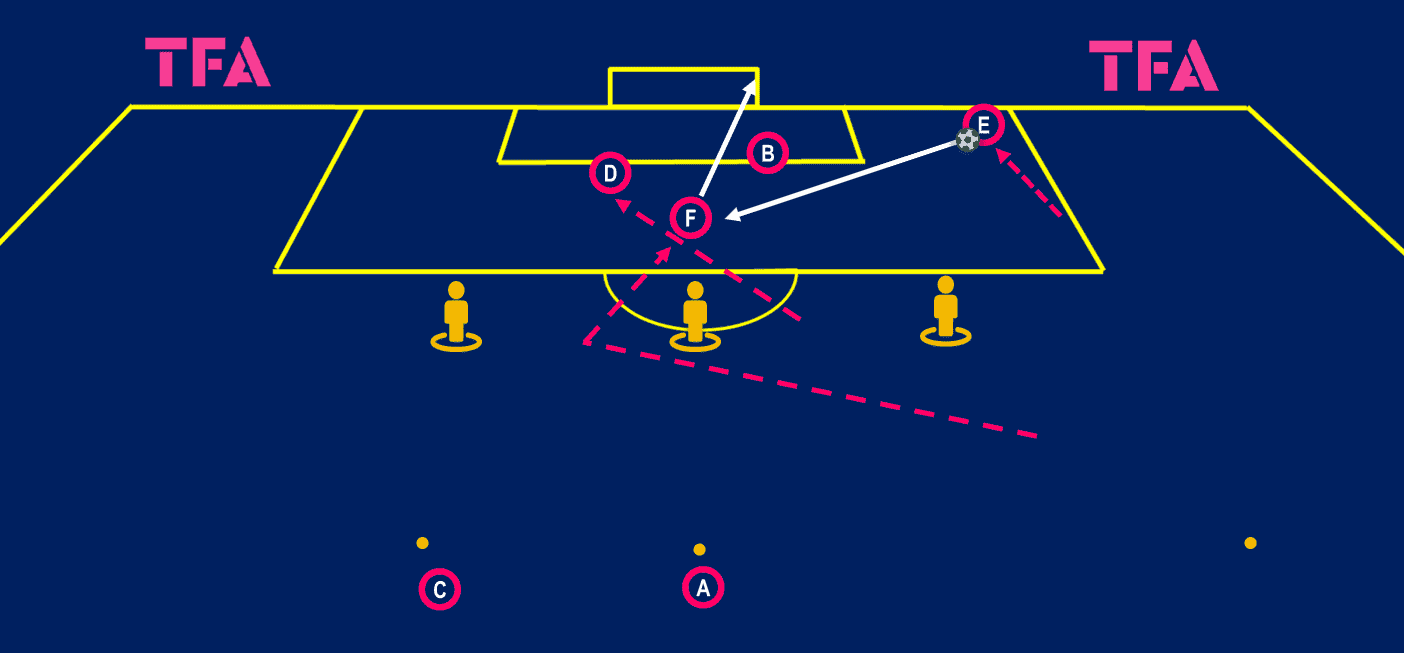

The second phase of this shooting exercise incorporates three shots at goal per repetition and works on various forms of combination play. The first combination, beginning centrally, replicates the movements performed in the first phase of the drill. After shooting, the striker remains involved for the entirety of the drill.

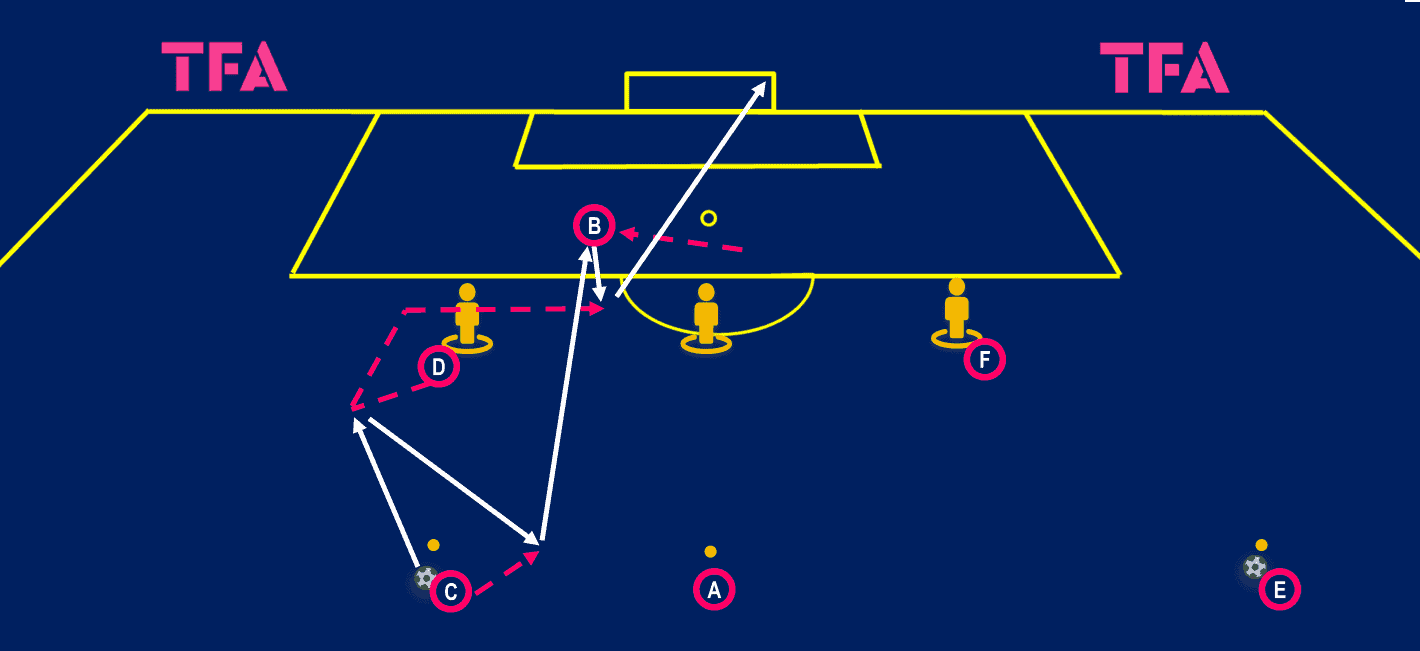

In the second combination, player ‘B’, who has just shot at goal, immediately moves to receive from player “C”. Player “C”, who has already played a bounce pass with ‘D’, plays a firm, line breaking pass into ‘B’. ‘D’ makes a blindside movement around the defender before running across ‘B’ and receiving a layoff. After shooting, ‘D’ immediately shows for the next ball. The aim is for the passes to be timed well enough that they can be completed without hesitation.

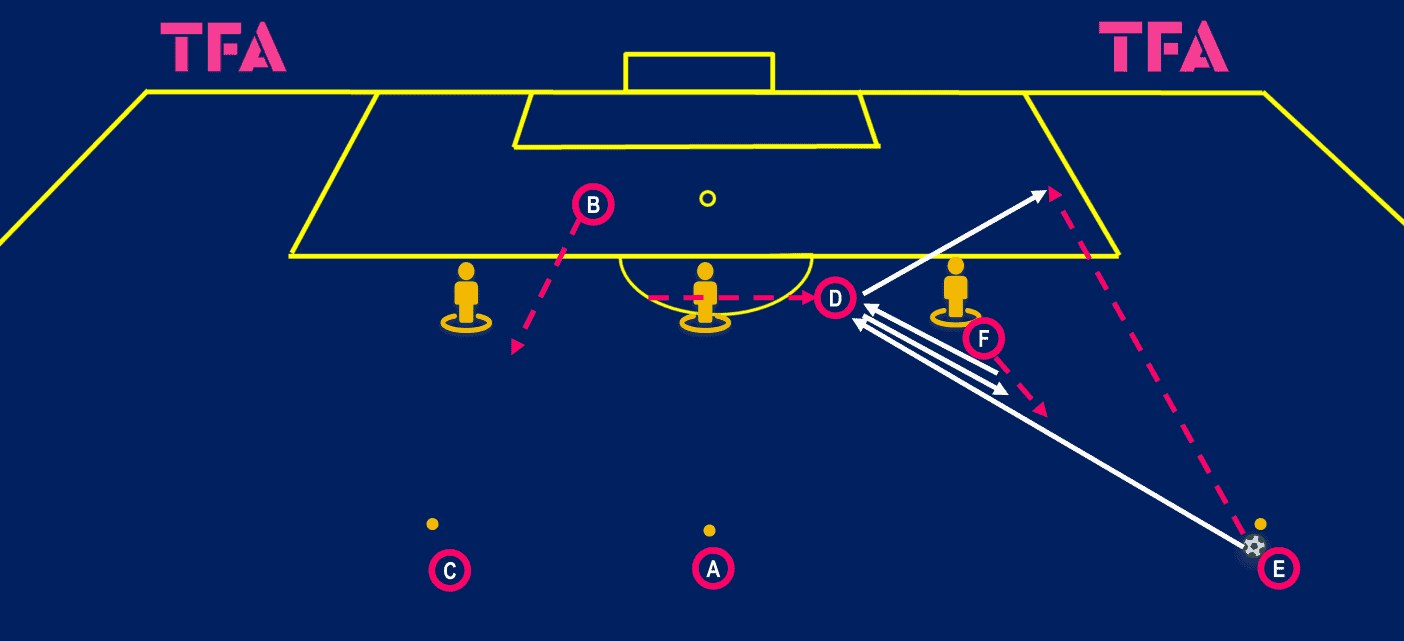

The third shot comes from a combination leading to a cut-back. ‘D’ receives form ‘E’ and lays the ball back to ‘F’, who had initially moved towards the pass from ‘E’ before stepping over it. ‘F’ bounces the ball to ‘D’, who plays the ball out wide for ‘E’ to run onto. As this is happening, ‘B’ moves to an “onside” position.

As the ball is played wide, ‘B’ and ‘D’ cross over each other and make runs towards the goal. These runs are designed to replicate players arriving in the box early and pushing the defensive line back towards their own goal. This creates the space for ‘F’, who is the intended target, to receive the cut-back around the penalty spot area. If the timings of the runs are not in sync with the positioning of the ball, the wide player can pick out players’ B’ and ‘D’ instead.

Conclusion

Luis Suárez is undoubtedly one of the best forwards of the modern era. The Uruguayan, who turns 37 next month, is still able to find the net at the highest level of the game. Suárez lacks none of the tenacity he once blessed European football with, and his movement and composure make him still one of the world’s top strikers.

The four-time La Liga champion and UEFA Champions League winner in 2015 can finish with his head and both feet. He can score from outside the box, set plays and is one of the calmest players around in one-on-one situations. These attributes, coupled with the intelligence of his movements, make him impossible to play against and a model player for any aspiring striker.

Comments