“Rhythm” is a term that many football fans have heard, with commentators, pundits, coaches and players using it in many contexts, whether it is used to describe an individual’s game, interactions between a couple of members of a team or the squad or the state of the game in general.

The difficulty surrounding buzzwords in any field is that after a certain amount of time, they can be used and interpreted in many different ways, such as whether or not the “game is flowing” from the perspective of commentators.

In this particular context, it is clear that rhythm, in most situations, is used to describe the speed at which the game is being played and the rate of different actions and interactions by players. But within this, it is also essential to discuss how rhythm can be controlled in the first place.

This tactical theory analysis will examine how different teams’ tactics that allow them to control the rhythm of their play and how the understanding of controlling rhythm can be trained. However, as this piece will later explain, due to the unique game models and identities of teams, the drill discussed will be centred around ideas on how the concept of controlling the rhythm of build-up can be introduced. As a result, readers may feel free to adapt and tweak certain practices however they see fit.

Space & Time in football.

When referencing the rhythm of build-up play, the concepts of space and time are essential. As the Portuguese coach João Carlos Pereira has stated, rhythm is interlinked with the speed of ball circulation regarding space and time.

From this view, when space increases, players are afforded more time on the ball, allowing them to take more touches and more time to make decisions. However, when space decreases, players may have less time on the ball, giving them fewer touches and less time to make decisions.

However, both space and time can be deceiving in regard to the control of the rhythm of the build-up. In the context of larger space being available, although players can take more touches and have more time to make decisions, this does not necessarily mean that they should take more touches and more time to make decisions.

From the perspective of decreased space, players are likely to still have to take fewer touches on the ball and will have less time to make decisions, but this does not mean that the resulting speed of play should increase and only be geared towards progressing the ball forward in that space.

Thus, players need to understand how their side looks to progress the ball, and from this, an understanding of how they can control the rhythm of progression can be cultivated. From experience, players must not only be told to try and progress the ball through a particular area of the pitch (wide areas, between lines, half spaces etc.) or a specific type of pass (diagonal, vertical etc.).

Players should be coached to move into spaces to create certain conditions and situations and recognise these situations to enable them to progress the ball in a certain way. As a result, the knowledge of how other players in a team intend to move into spaces and how a side intends to exploit the opposition in these spaces allows players to analyse different situations and make decisions according to this.

From this perspective, the concept of rhythm can then be introduced to players as players are more aware of how quickly they should circulate the ball based on their knowledge of the model and the analysis of specific scenarios.

More work can then be done on different methods that aid them in controlling the tempo of build-up, such as body position when receiving the ball, speed of passing and how they look to control the ball. Some of these concepts can be seen in De Zerbi’s sides, with players using the soles of their feet to slow down the game and instigate the opposition press.

To fully explain these concepts, it is best to provide concrete examples of how different teams look to control the rhythm of their build-up.

Inzaghi and Alonso

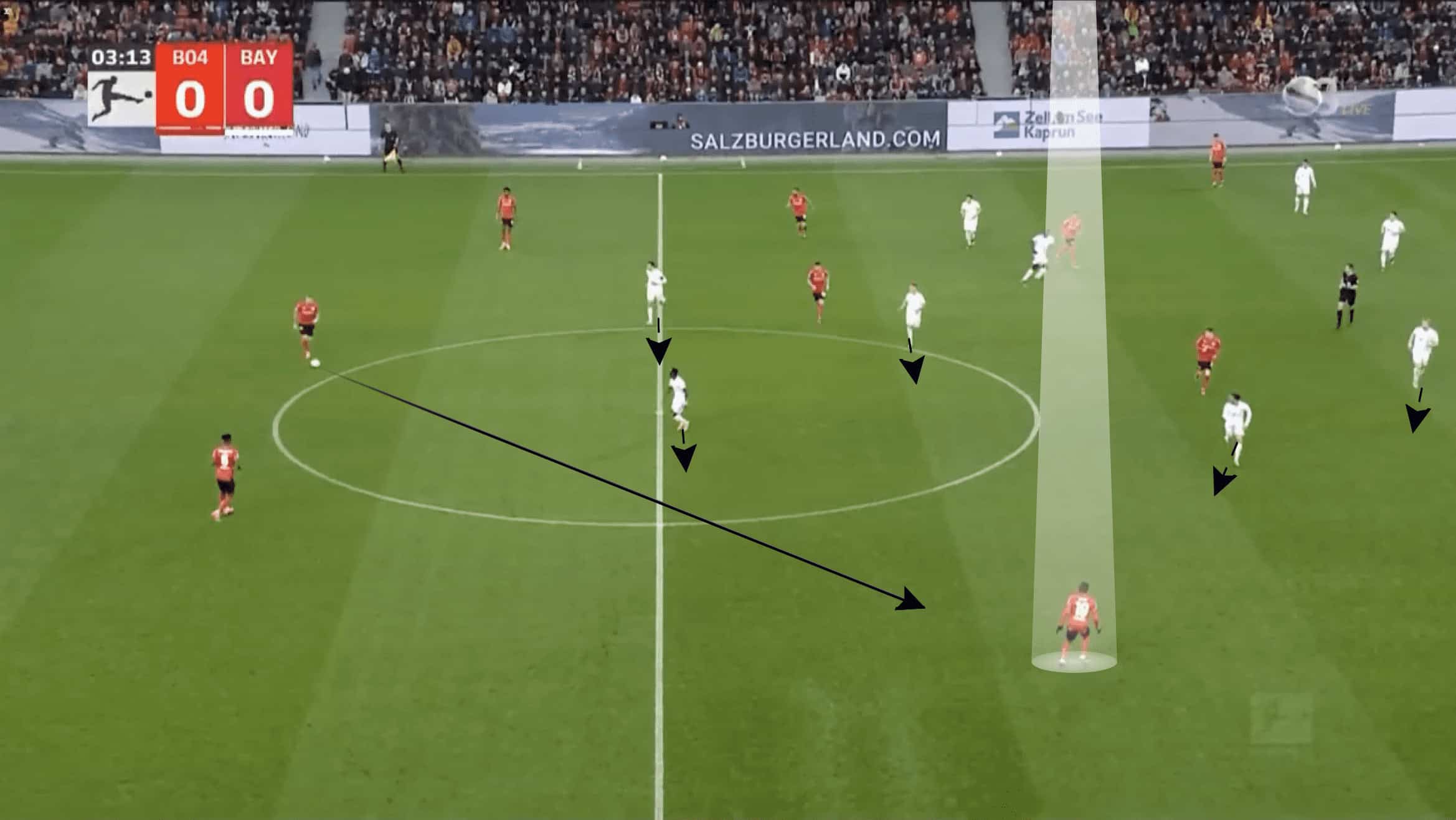

Inzaghi’s Internazionale last season were a fascinating team to observe throughout last season. Inter looked to attack opposition teams quickly from their own third. However, they would pick their moments to do so, with many of these quick attacks coming after relatively slow and controlled build-up.

Their overarching method in controlling the tempo of the build-up has a similar objective to that of Brighton, with the back three to slow the game down often to instigate the opposition press.

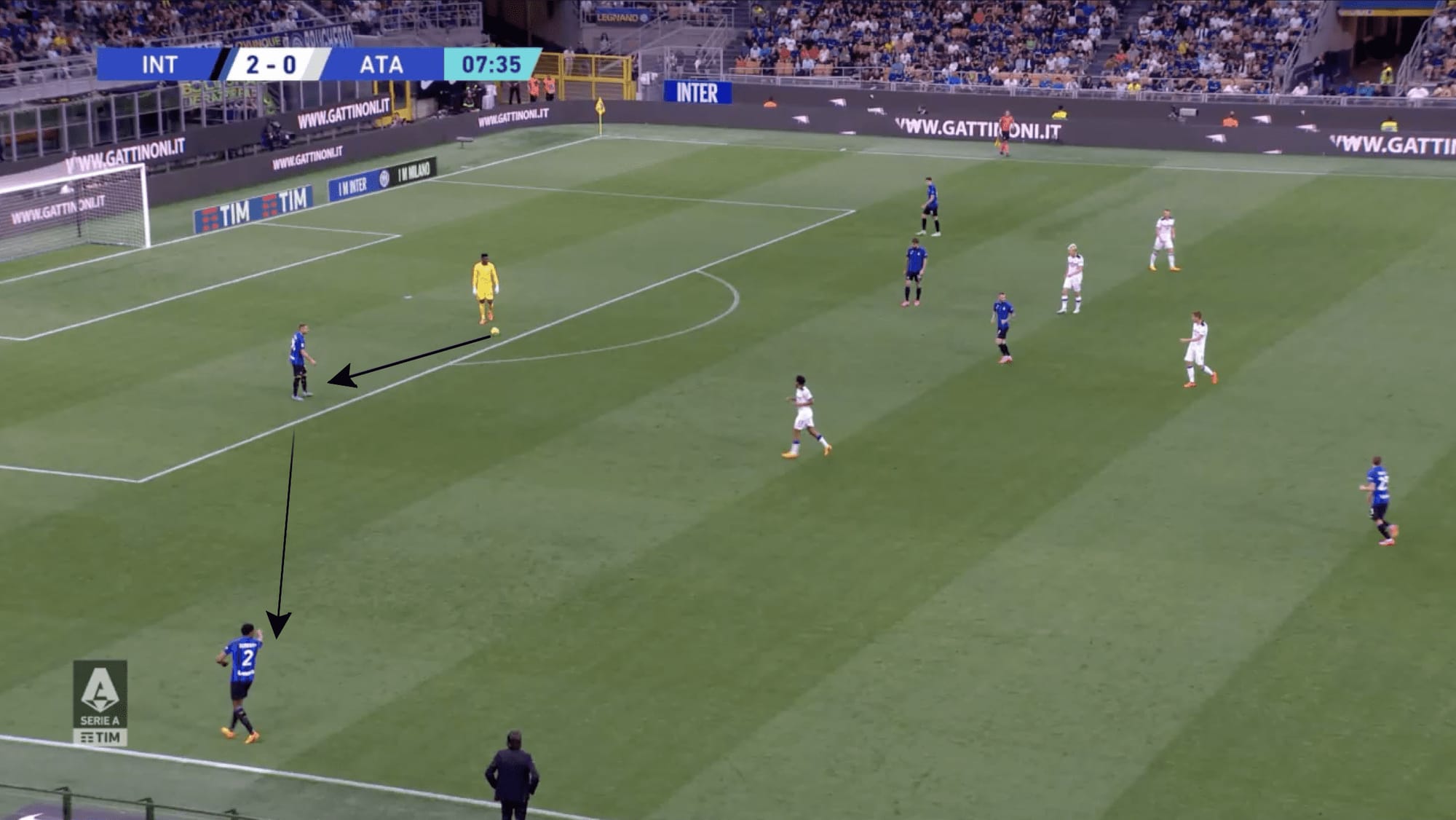

Inzaghi’s men did this to wait to create spaces where passes could be played directly on the ground to one of the two strikers or to players in the wide areas and outer central channels who would then look to play the furthest forward pass that they could and complete third man combinations, with the moment of the forward pass being the general signal for an increase in the speed of play. An example of this can be seen in the image below.

In this game, the opposition were reluctant to press Inter’s backline aggressively and looked to prevent progression through the central channels. In this scenario, there is enough space and time for Onana to play the ball to his right to the centre-back, who could have then played a pass to Denzel Dumfries, who could then look to play a pass forward.

However, Onana chose to hold on to the ball, perhaps surmising that the team were not adequately prepared for an increase in the speed of play.

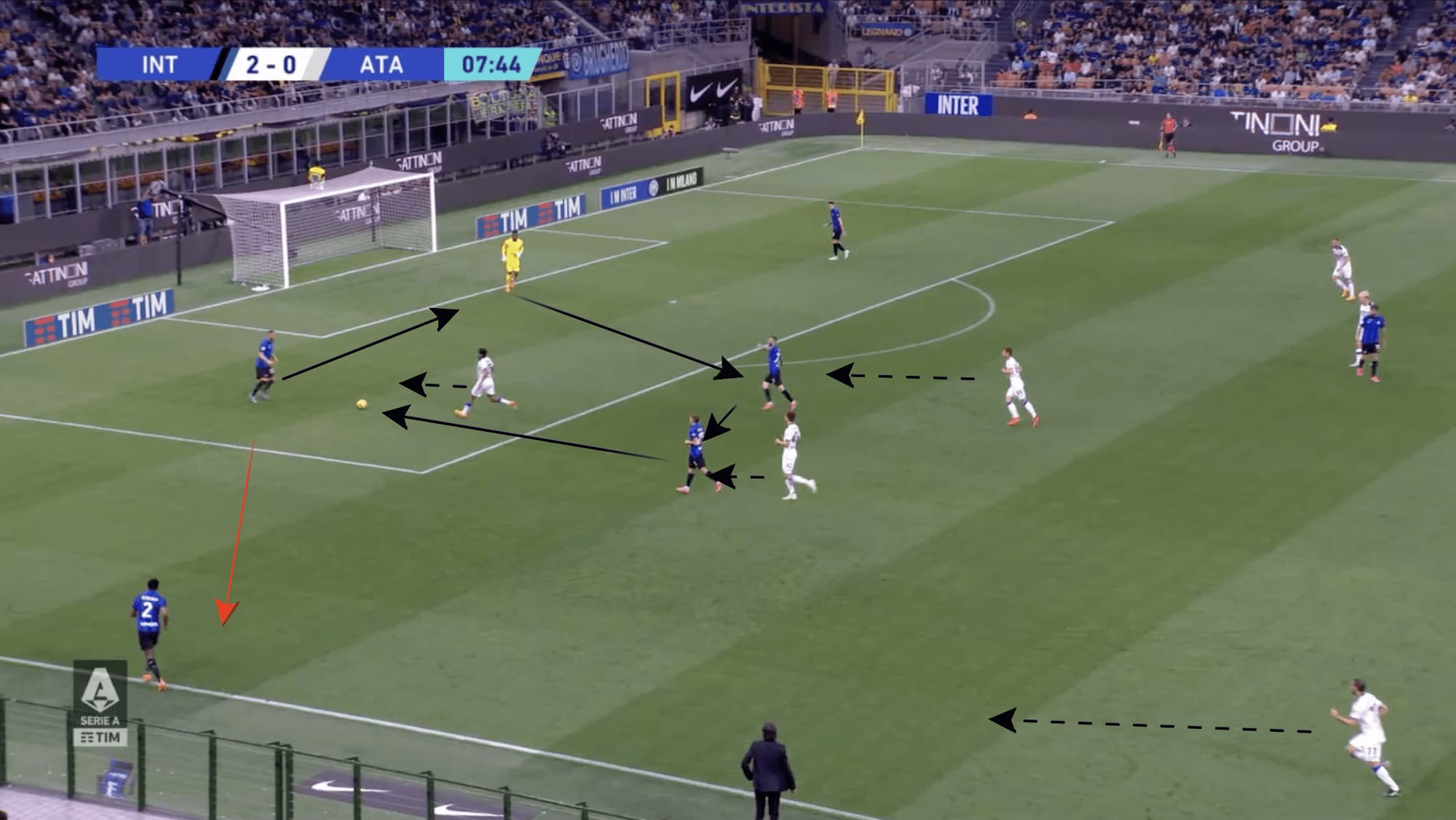

Onana, however, decided to play a pass into the midfield and thus trigger the opposition’s press in the centre of the pitch, resulting in a decrease in space and time for both Nicoló Barella and Marcelo Brozović, resulting in the pair playing one-touch passes and briefly increasing the tempo.

As the image below shows, part of the opposition press triggered. As the tempo rises, Danilo D’Ambrosio has the option of playing the ball to Denzel Dumfries, which Brozović directs him to do, with the wing-back having enough space and time to take a touch and play a pass forward and thus continue to speed up the rhythm of play.

However, the centre-back chooses to play a pass back to the goalkeeper and slow the game back down again. This links back to the previous idea that an increase in tempo and a decrease in space and time does not have to result in a general increase in the speed of play.

With more space due to a lack of opposition pressure, Onana takes more time on the ball; he and Alessandro Bastoni begin to play passes between each other slowly, instigating the opposition press.

As the opposition becomes more aggressive with their press, Inter’s midfielders start moving closer to the ball. Still, whilst this occurs, players in more advanced areas do not begin to drop deeper but maintain their positions, increasing the distance between the lines of defence.

Due to the opposition press and the movement and positioning of Inter’s players, space is created for Onana to execute a long ball on the ground to Romelu Lukaku.

As stated earlier, this type of forward pass acts as a trigger for the general speed of play to increase, with the players moving quickly to support the player receiving the pass, with most actions after the furthest pass done in one to two touches.

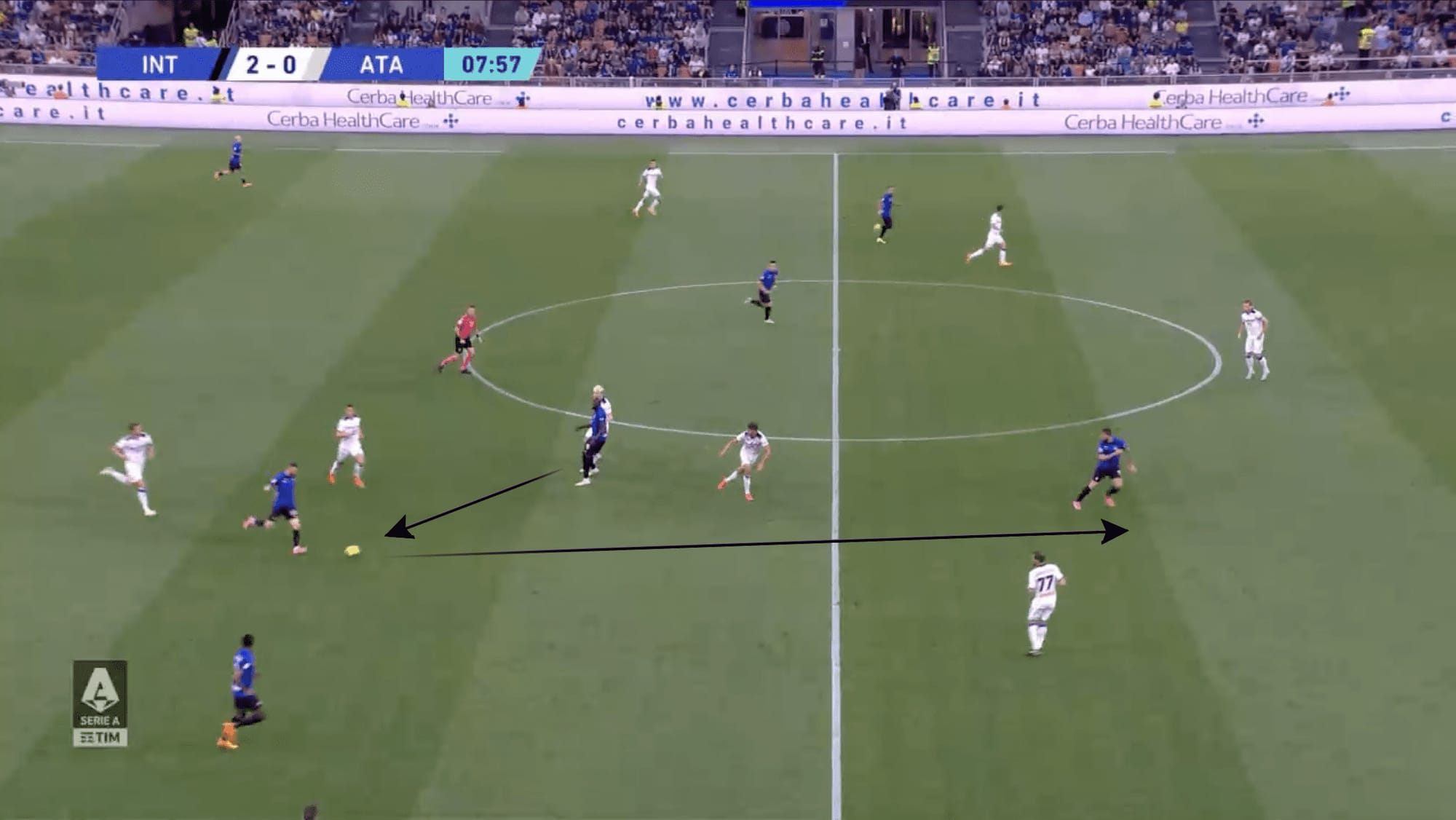

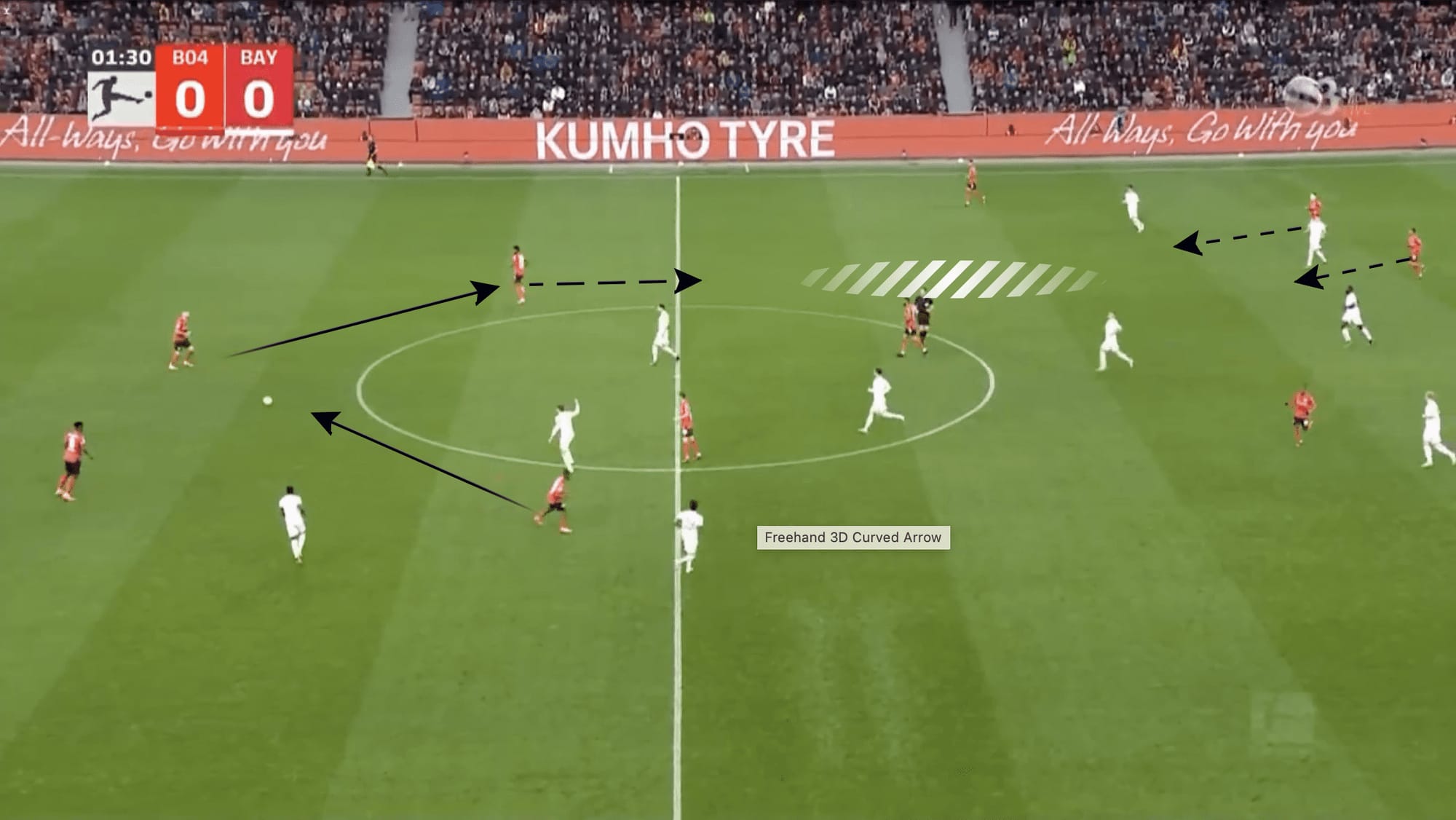

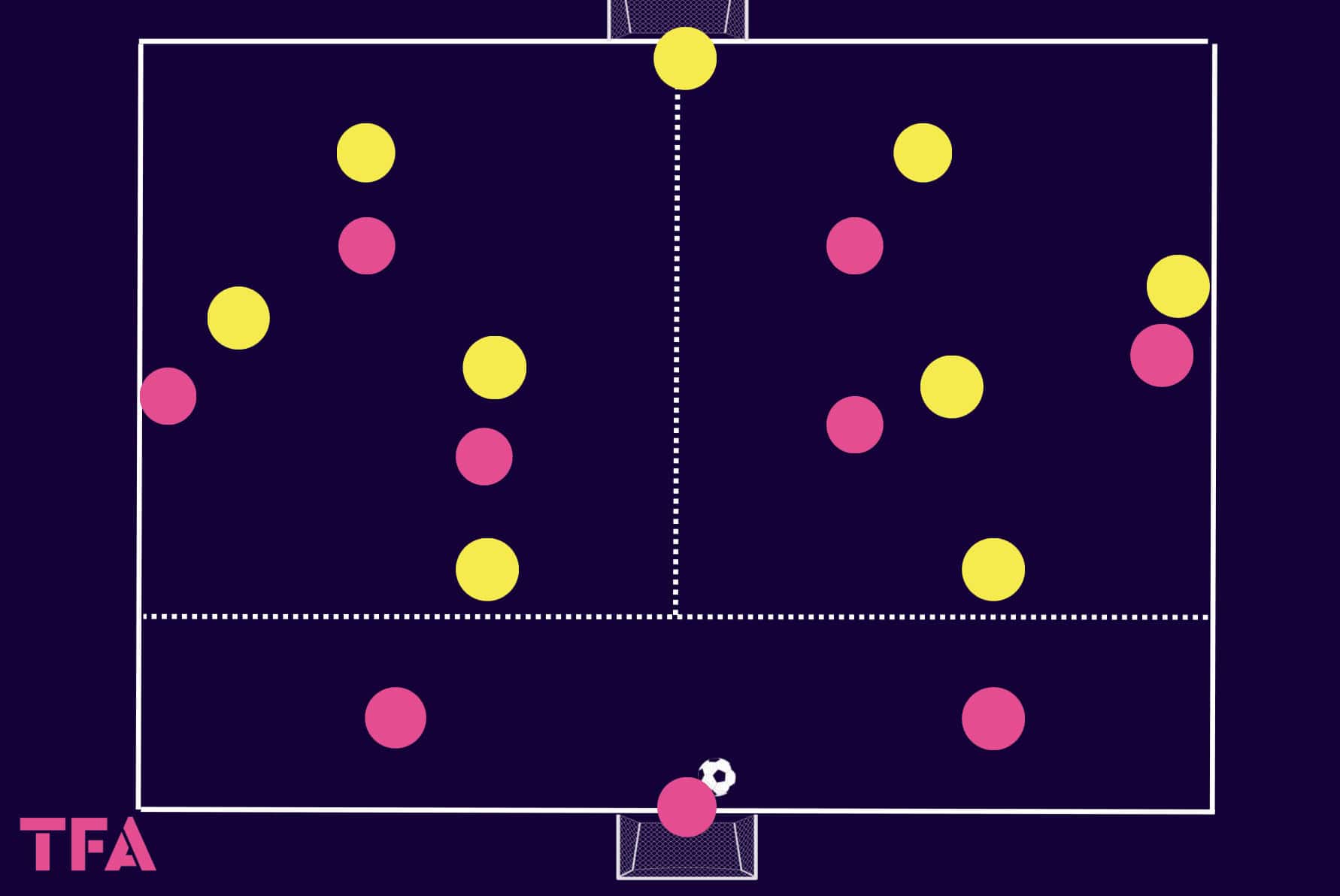

On the other hand, Xabi Alonso’s Bayer Leverkusen are much less concerned with trying to directly provoke the opposition into pressing them. In this game, Leverkusen chose to build up with three players, have very good attacking wing-backs, and have players playing with two tens that operate between the half-space and can drift out wide.

They then work to try and progress the ball in the wide areas, with their centre-backs carrying the ball forward and the players ahead of the ball looking to move into spaces that allow them to take advantage of 3v3s or 4v3s in their favour.

If they cannot progress the ball forward down one side of the pitch, they look to switch to the opposite half space or wide area. Due to this, the speed of their passes at the back is critical at times, as they need to be done very quickly to give the opposition as little time as possible to regain their defensive shape and cover the opposite side of the pitch.

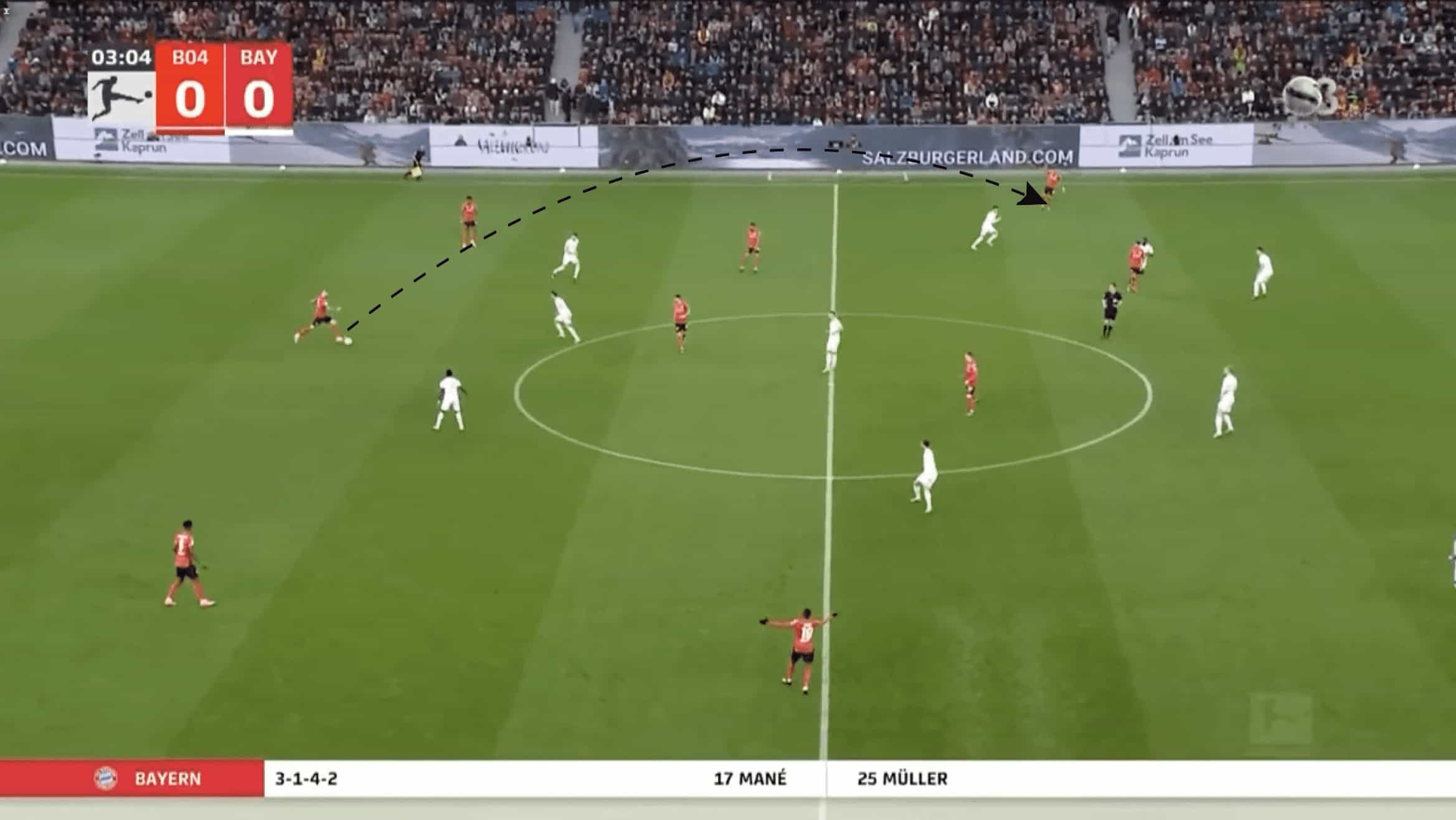

The image below provides an example of Leverkusen’s structure and the dangers of too much space and time leading to slow decision-making. The right wing-back Jeremie Frimpong plays a pass to Robert Andrich, who dropped into the back-line to form a back three.

From the pass, Robert Andrich waits for the pass to arrive and starts to move backwards before playing a pass to the left centre-back Edmond Tapsoba. With more space and time, Andrich takes longer to play the pass to Tapsoba, who can carry the ball forward, access the wide area, and take advantage of the opposition’s slightly disorganised state.

However, due to the speed of the previous action, the opposition could regroup defensively, and the previously vulnerable space became well-defended.

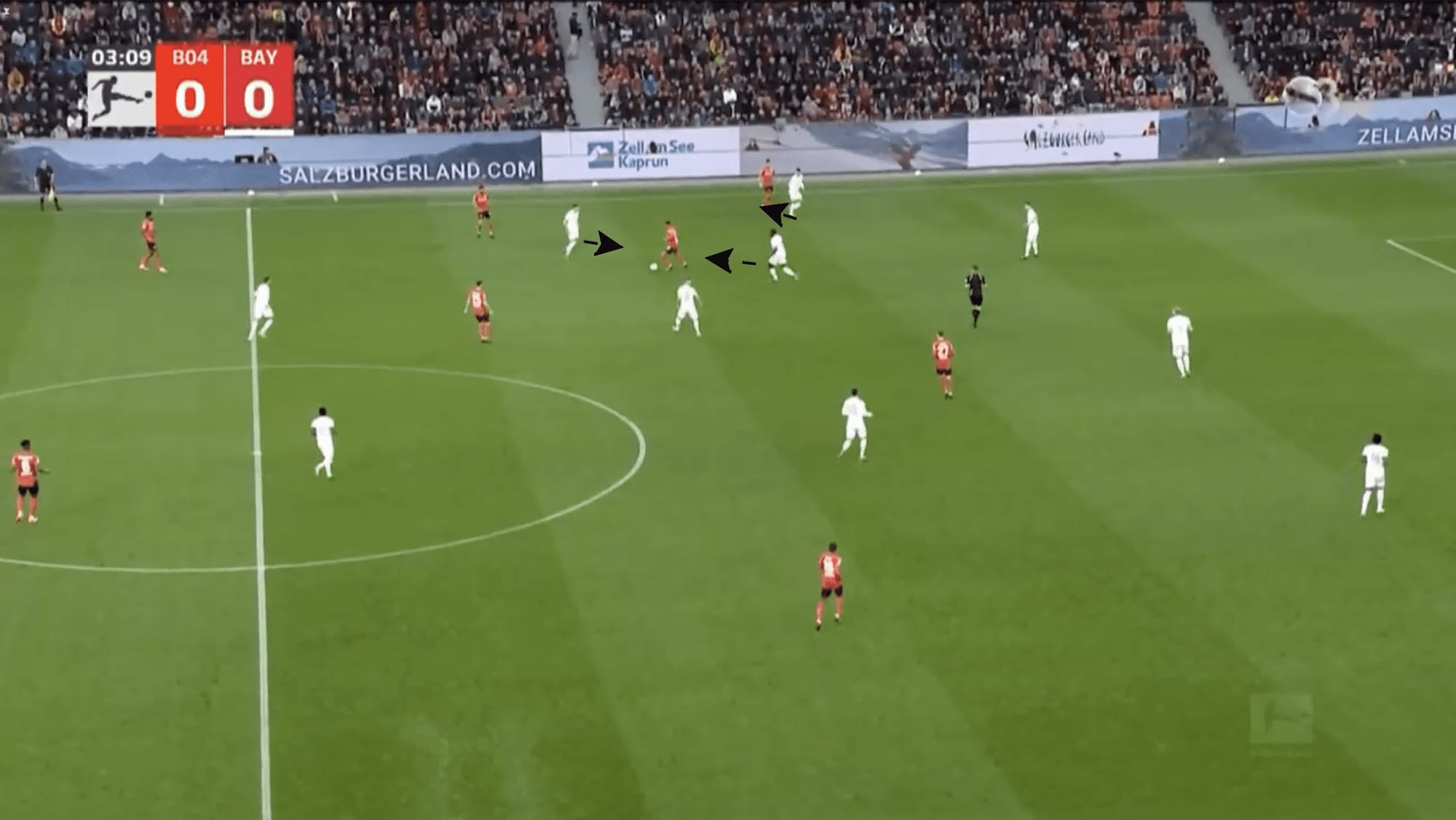

The following example shows how pivotal the speed of passes and the speed of the switch is in controlling the rhythm of the build-up. Andrich receives the ball, advances more urgently than in the previous example, and plays a pass to the left wing-back.

Leverkusen’s players close to the ball move into spaces that allow them to create a triangle in the wide area but are closely marked and, as a result, unable to progress the ball.

The ball is played back to Andrich, who receives the pass and plays the quick to Moussa Diaby on the opposite side, who can find space due to the opposition’s shift towards the right-hand side.

Training ideas

As stated previously, for the control of rhythm to occur, players need to have a clear idea of how the side looks to progress and how to move into spaces that create conditions that allow for progression. The following training games on ideas on how the concept of controlling the rhythm of the game can be introduced.

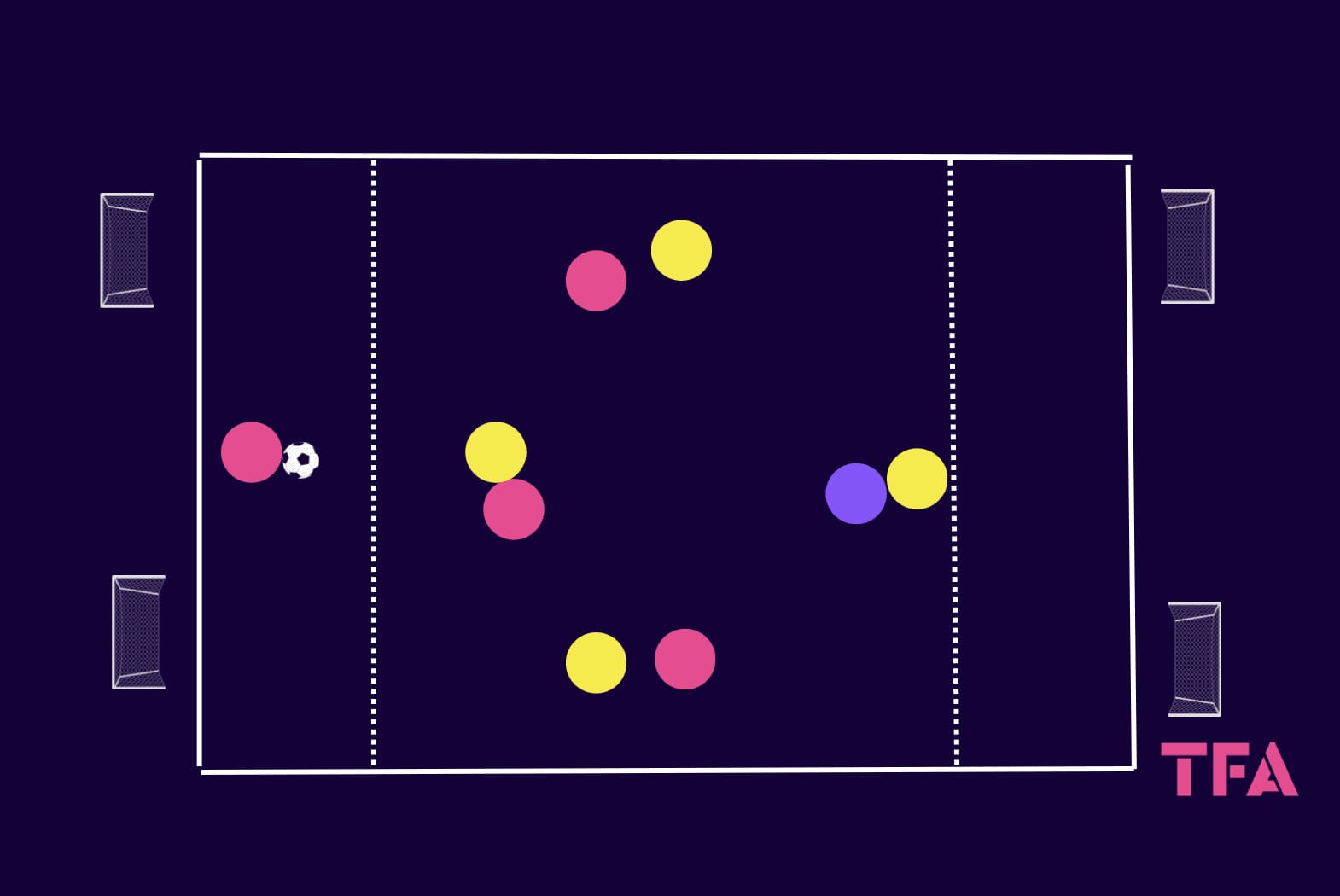

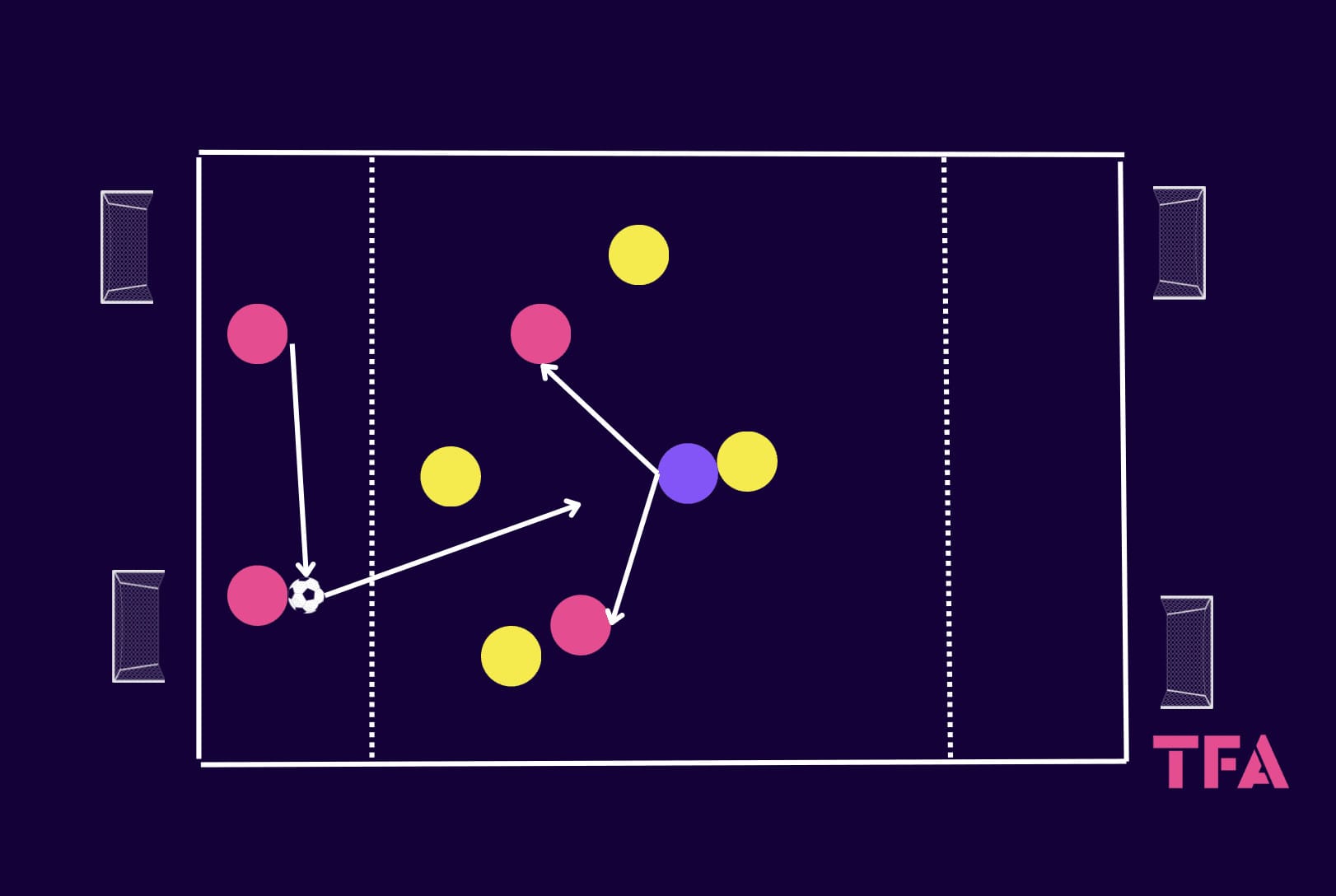

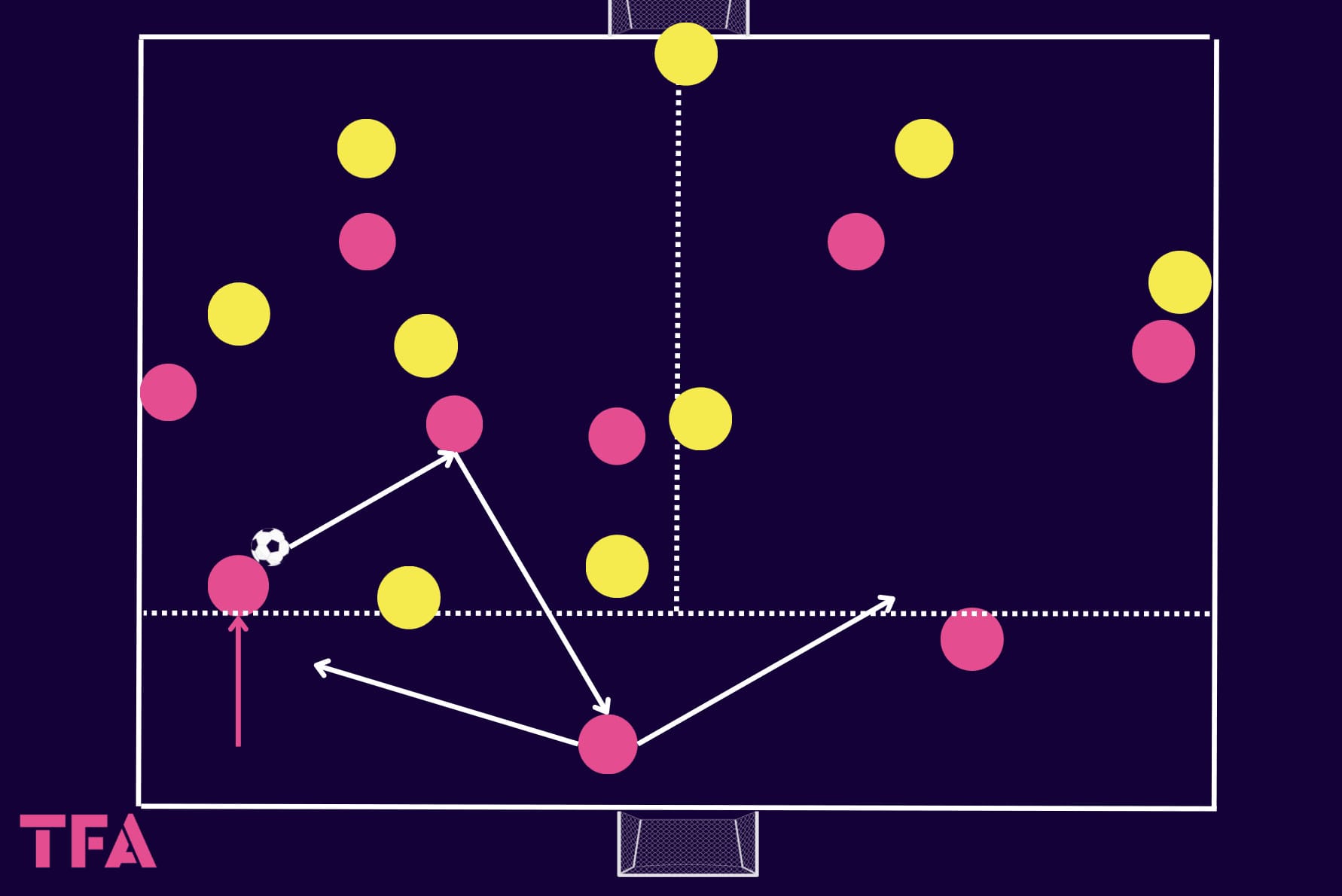

4V4 + 1 game

Size: 20×20-25×25

The rules of this three-zone game are relatively simple, with teams trying to progress the ball to the opposite side and score in the mini-goals. The defending team must stay in the middle zone, press opposition players in their end zone, and only enter it once they regain possession.

As a result of this, passes back into these zones have the effect of slowing down the speed of the game, with the team in possession allowed to have a maximum of two players in their end zone, encouraging different players to occupy this space, with these players dynamically also allowed to carry the ball into the middle zone.

The team in possession is awarded three goals if they complete a third-man combination with the neutral purple player.

Players in the middle zone in this exercise should ensure they are not all positioned on one line and look to support the receiver of a pass as soon as possible. If players still need to be in a position to receive or support a forward pass, then players should refrain from playing the ball forward.

Players should also be aware of their surroundings and ensure their positioning does not block a potential forward pass to the neutral purple player.

Due to the freedom that the end zone provides, this is also a perfect time for players in this zone to try and provoke pressure, which could be done by threatening to dribble slowly into the middle zone to create other spaces for their teammates.

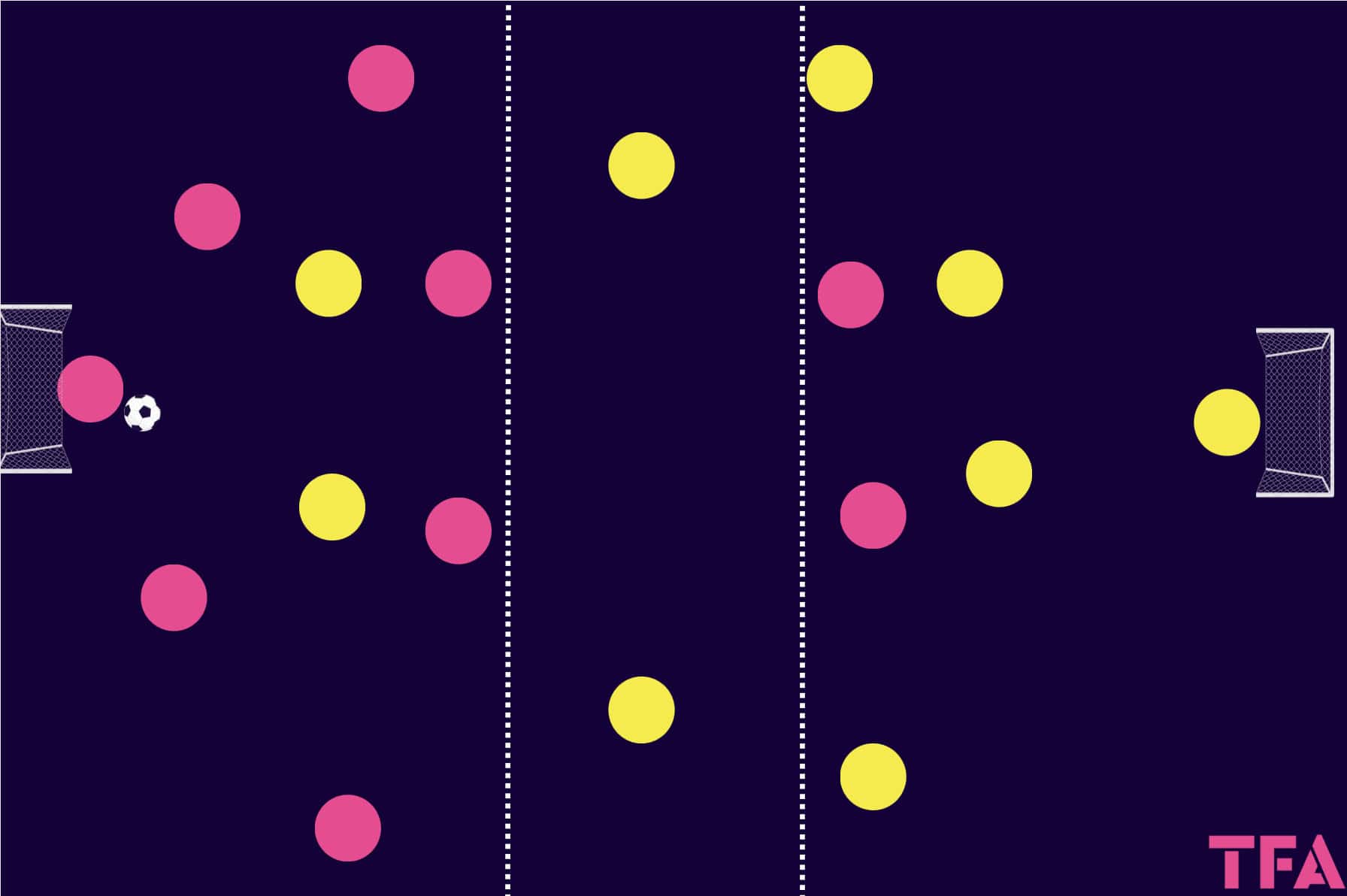

9V9 positional game

Size 60×60

The rules of this next practice are also simple, with players trying to score the goal on the opposite side of the pitch. To progress the ball into the other half, the team in possession must play the ball into the middle zone and complete a third-man combination to play into the other half.

All players are restricted to their zones except in defence and attack, except for the two midfielders in the side. All players are free to move into the middle zone. Once a pass has been played into the central zone and a third-man combination is completed, the side in possession can progress into the other half, with players no longer restricted to their zone.

The coaching points around this are centred around how we should look to progress, with the numerical superiority in possession due to the zone restriction. The team with the ball have adequate time and space to play quickly and slow the game down.

However, players are aware of the zone they need to play into to progress and, as a result, will need to be mindful if this pass is possible. Players need to ensure that after a pass is played into the middle zone, they occupy positions to support the receiver of the pass.

Players in the other half also need to time their movement into the middle zone and should refrain from just staying in the zone.

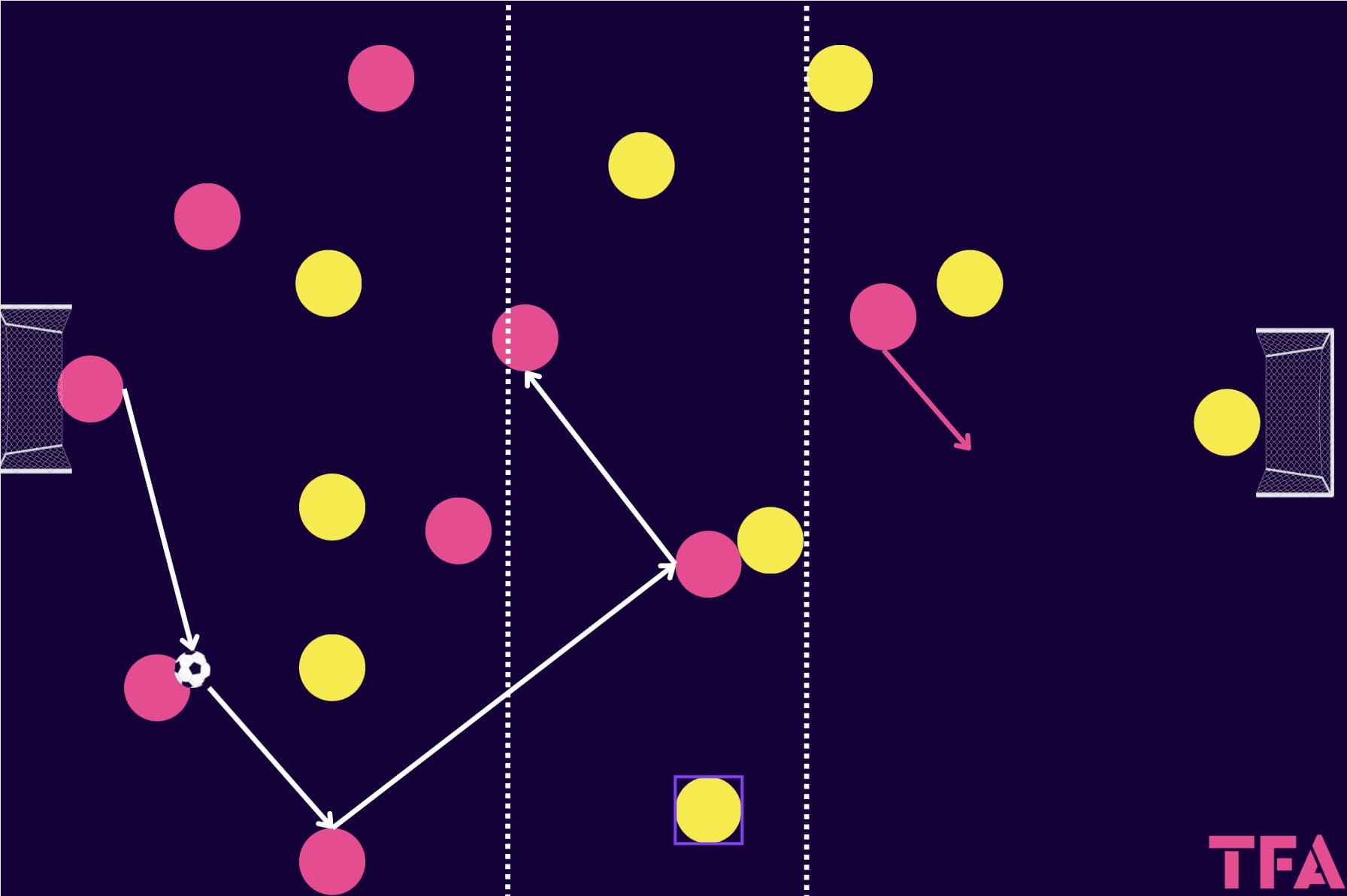

9v9 switch game.

Size: 60X60

This game is less positionally focused and is looking to work more on switching possession and carrying the ball forward. The game is played in 15-minute halves, with one team looking to carry the ball forward into space when they are not being pressed.

If the team in possession switches from one half to the other and scores, they are awarded two goals. There are no restrictions to movement in this exercise.

In this exercise, the speed of the switching pass is essential if the opposite half is left vacated. At the same time, the carry by the defender is also significant. When playing in either of the halves, the positioning of all players is paramount, with players needing to ensure that they give the ball carrier at least two passing options.

Conclusion

This tactical theory analysis has looked to explain the concept of rhythm in football. Like many concepts in football, the rhythm of build-up and the control of build-up do not exist in a vacuum and are interlinked with many different aspects of the game. From a personal perspective, the control of the rhythm can only exist with players having a clear idea of how they need to progress the ball and which spaces they should move into to create the right conditions for how they intend to progress it.

Players can then be taught how to analyse different situations and make decisions on the game’s speed as a result.

Comments