The high press consumed football tactics for most of the past few decades.

It was a way to set the match’s tempo from defence, to be the aggressor and create opportunities for recoveries high up the pitch. Clubs like Barcelona and Manchester City have been leaders in the movement. Add in any club that Jurgen Klopp and Thomas Tuchel have coached.

But versatility when defending is still a necessity. Though many top teams still initiate play through a high press, other top clubs have shown the ability, and at times a preference, to defend in a mid-block. Analysis of those top clubs gives us an idea of how to do it and, equally important, connect the mid-block to counterattacking opportunities.

In this tactical analysis, we’ll start with organisation and pressing traps within a mid-block. But that isn’t the end goal. We want to connect defensive tactics to transition attacking. This analysis will look at in-game tactics and then connect the ideas to exercises for coaches to take to their own environments.

Setting up the mid-block

Before we can even talk about counterattacking, we have to create those opportunities with a staunch mid-block. Let’s start with the things we want to achieve by defending from this position.

First, we want to reduce the space opponents can play into behind our backline. The short distance between the centre-backs and the goalkeeper makes it very difficult for opponents to successfully play into that space. If they do try to knock the ball behind the backline, it’s the goalkeeper’s responsibility to give his centre-back coverage.

Second, we want to keep our lines tightly connected, making it difficult for opponents to play through us. We can take this a couple of ways. One option is to occupy the central part of the pitch to force opponents to play around the press. Another is to create a pressing trap centrally by baiting a central pass and then crashing on the first attacker while eliminating passing lanes to play out of the press.

We’ll focus on taking away the centre of the pitch and funnelling opponents around the press. We have an excellent example from Napoli. Even though Juventus had a back three and five midfielders and forwards positioned between the width of the box, Napoli’s press made it nearly impossible for Juventus to play through them. To do so, Juventus would have to play risky, contested passes in the centre of the pitch. Not ideal against a side that’s ready to counterattack.

Juventus does try to play around the press, but a poor pass is intercepted and kickstarts the Napoli counterattack. The way Napoli was set up in the mid-block, they were well prepared to sprint up the pitch with tightly connected numbers near the ball. That allowed them to mostly attack on a straight line, maximising the efficiency of the counterattack.

Intercepting entry passes into the wings is ideal, but even if the opponent does make it to the wide regions of the pitch, a well-designed mid-block will make the playing area smaller and seal opponents. Once opponents are sealed in the wings, the goal is to put pressure on the first attacker so he can’t play over the press, as well as contest all short and intermediate options. As the defending team, we want to hold a numeric superiority once we’ve funnelled the opponent into the wing. Once that happens, we just can’t let them out.

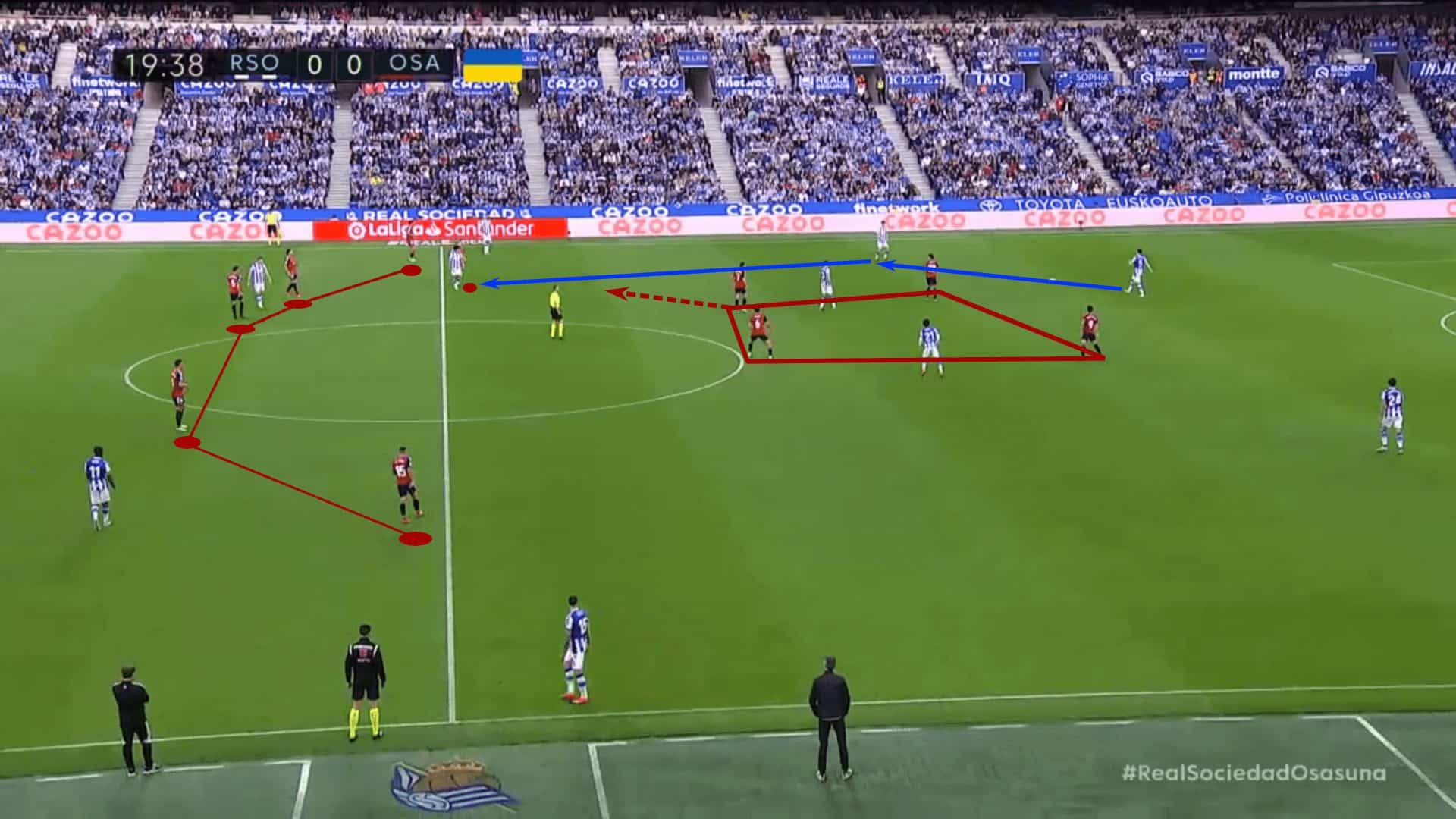

We have Osasuna set to funnel Real Sociedad in the wings to highlight this idea. The defending team enjoy a numeric superiority centrally, making it clear to La Real that the space to take is in the wings. However, once the pass is played into the wings, Osasuna quickly moves towards the ball to seal Real Sociedad out wide. With no outlets to play through or around the press, the result is a turnover in the middle third.

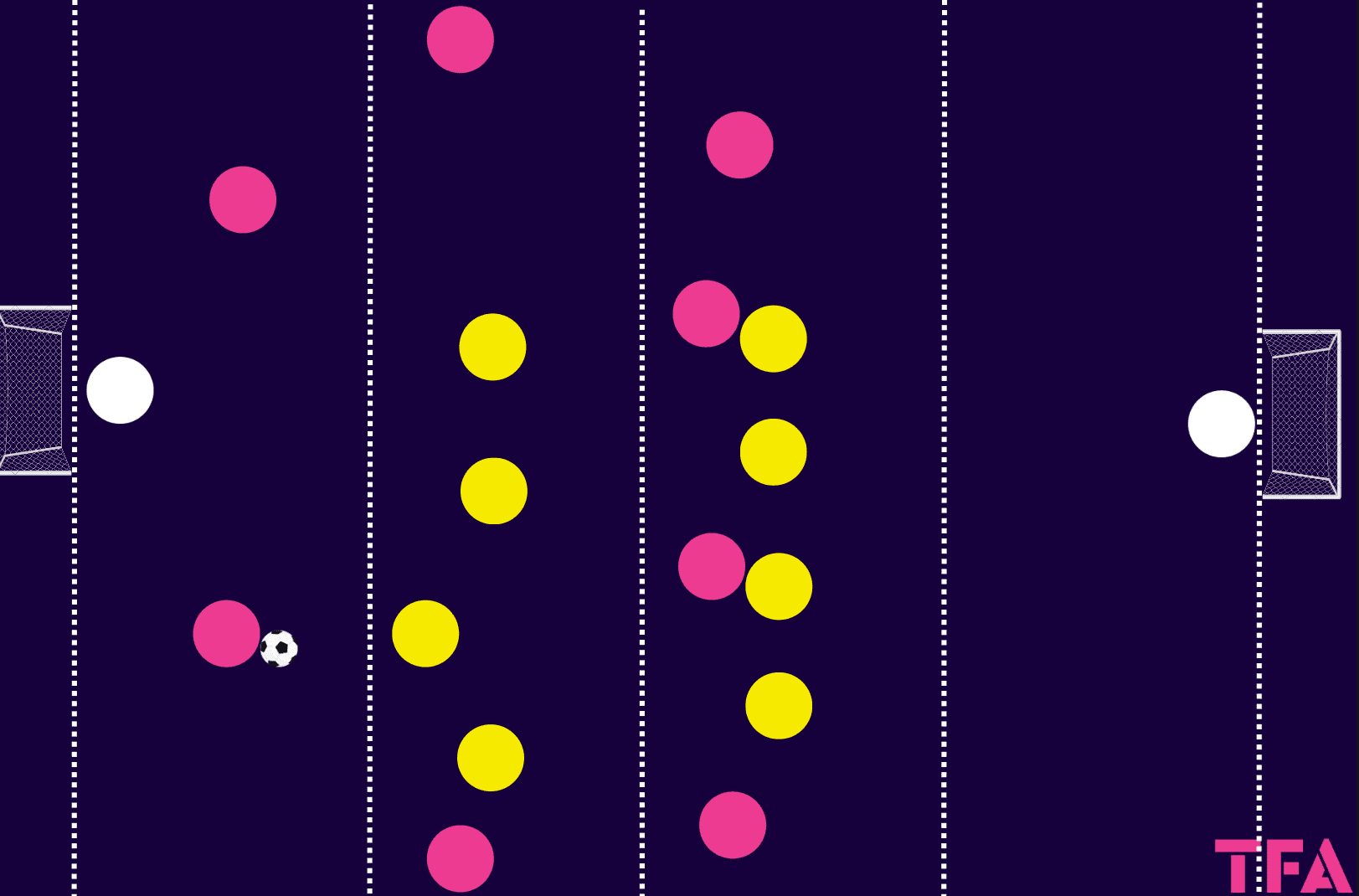

To train the movement of our lines, as well as vertical compactness, we’ll play a training game called 8v8 closing down. Each team has eight field players and a goalkeeper. Using the width of the box, we will create a pitch with a 40 m length that is broken up into 10 m segments.

The defending team must start in the two middle zones, with the first line in second quadrant and the backline in Zone 3. The attacking team is given three uncontested passes in Zone 1 before the defending team can take space and push into that highest zone.

The attacking team can play forward whenever they want, even on their first or second pass, but when they do swing the ball across the backline and connect with the goalkeeper, the eight defenders must limit the ability to play through the lines and show appropriate examples of pressure, cover and balance.

If the attacking team scores, play, make it take it. If they take a shot and miss, the two teams switch roles. Play 5-minute games and incorporate principles of the mid-block.

Coaching pressing traps

What if you don’t want to funnel opponents in the wings? The best scoring opportunities often come when the defending team recovers the ball centrally, and the opponent is still in their expansive attacking shape. If this recovery comes in the opponent’s half of the pitch or at least near midfield, there’s typically space to attack.

Directing the opponent inside rather than outside comes from the same general idea as the wide funnel. When we want to funnel opponents into the wings, we compress numbers centrally to signal that there’s no space to attack. We’re basically inviting them to take a free pass into the wings.

Likewise, funnelling the opponent centrally into a pressing trap has to communicate that there is space between our lines. Play there now.

Defending comes down to telling the opponent where they can go and when they can attack that space. If the defending team can control the where and when, they have made play predictable, giving them the advantage. This allows them to defend from a position of strength.

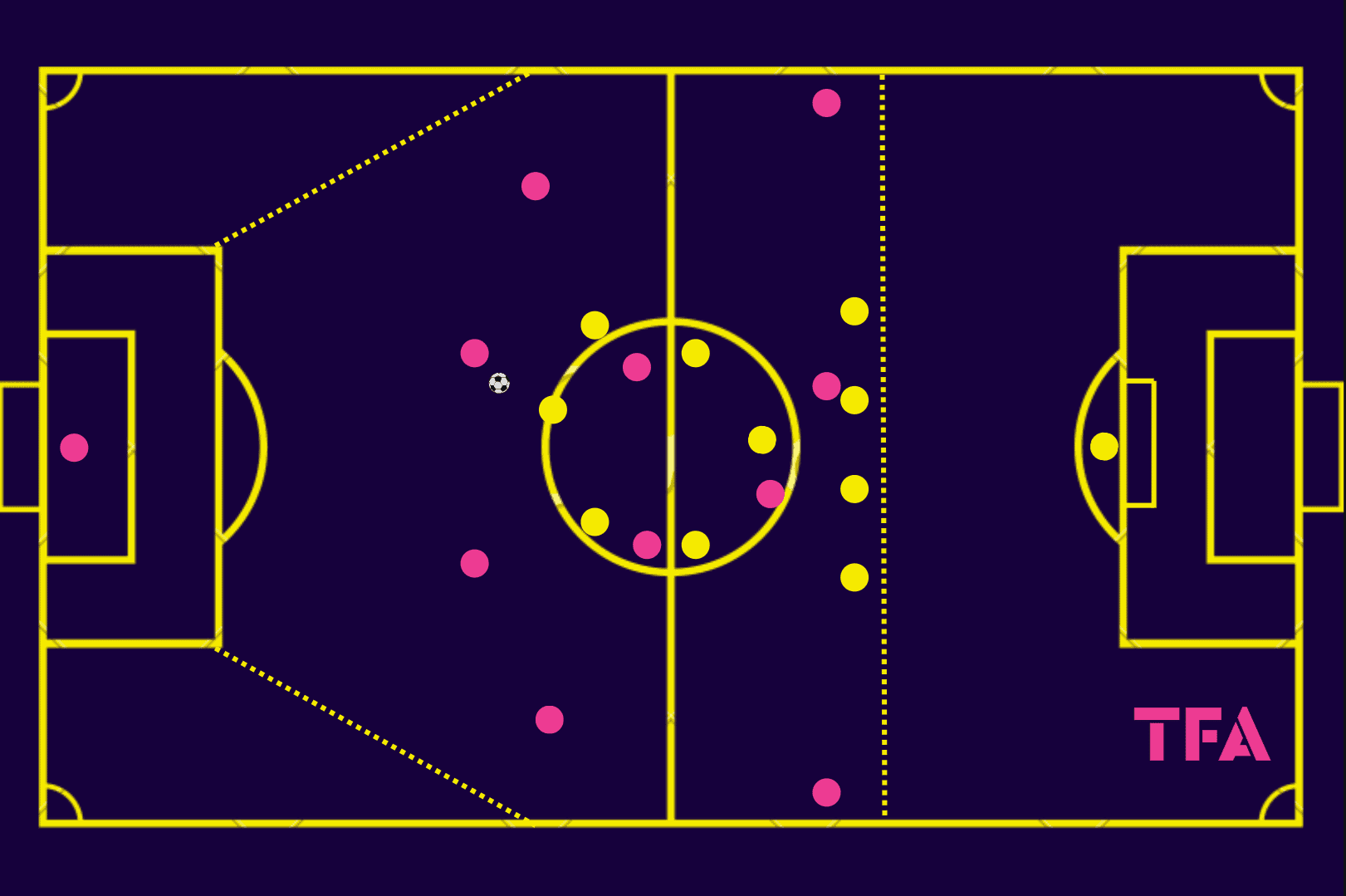

Let’s turn to Real Madrid’s mid-block against Manchester City to invite opponents into the central part of the pitch. Notice how many Real Madrid players have multiple assignments. The wingers are positioned between two players, one interior and one exterior. Even the midfielders are positioned between two players. This is designed to entice City to play into the press.

That is one way to do it. Increase the width of the lines to signal an opportunity centrally. Once the central pass is made, that large white-shaded space has to compress quickly. If they don’t, City will have the time and space to play out of the press.

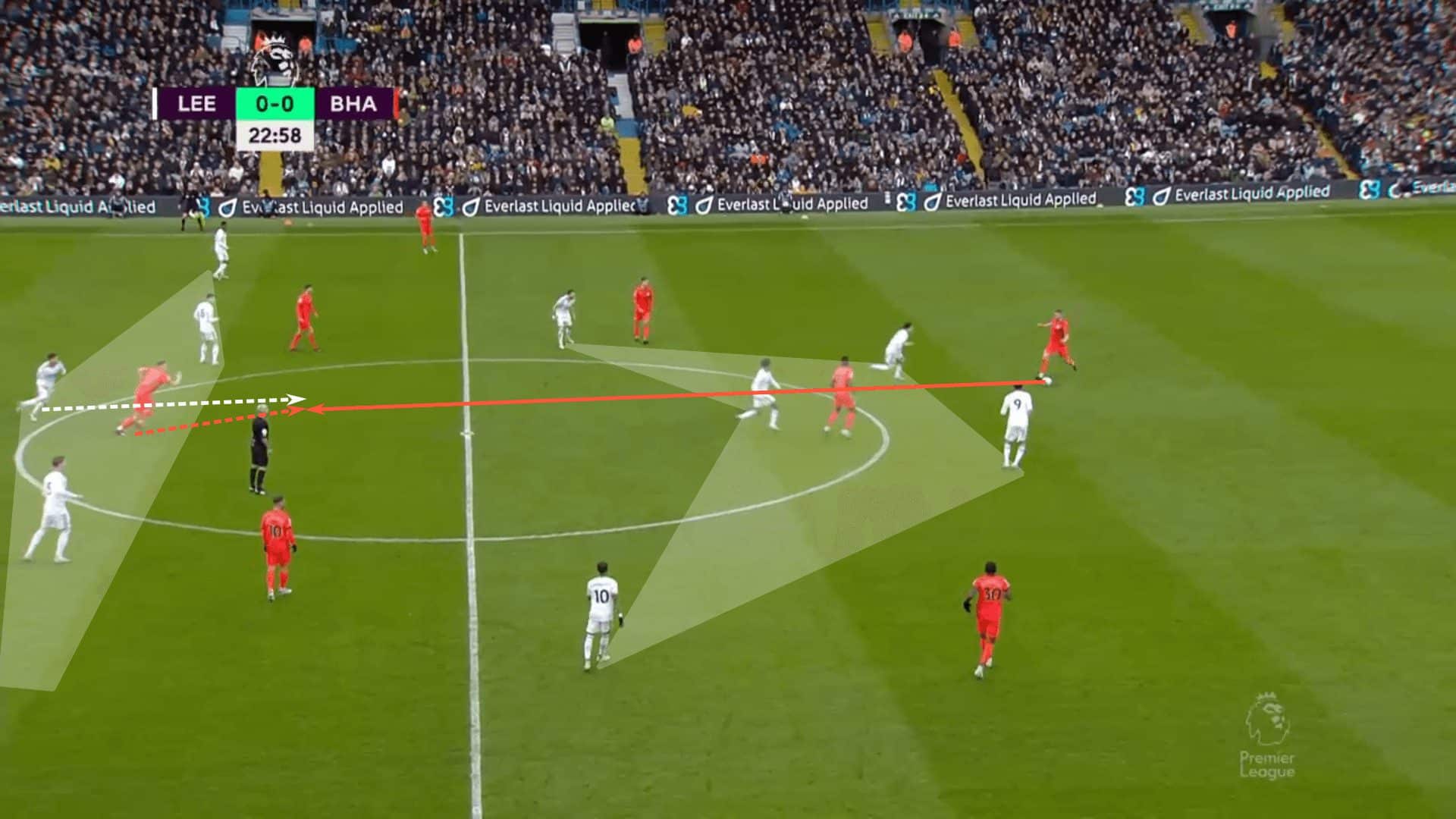

Another way to set a central pressing trap is to take a high and low approach, leaving space between those two groups. This is how Leeds United approached their matchup against Brighton last season. They committed high numbers up the pitch to pressure the centre-backs and defensive midfielders. The remaining players remained relatively flat to remove any layering in midfield. That created space for Brighton’s forwards to check into.

But that was the plan. Leeds could better apply pressure on that pass from front and back by forcing the forwards to drop into midfield while playing back to goal. Plus, their lines are centralised enough that they can quickly collapse near the ball once that pass is made.

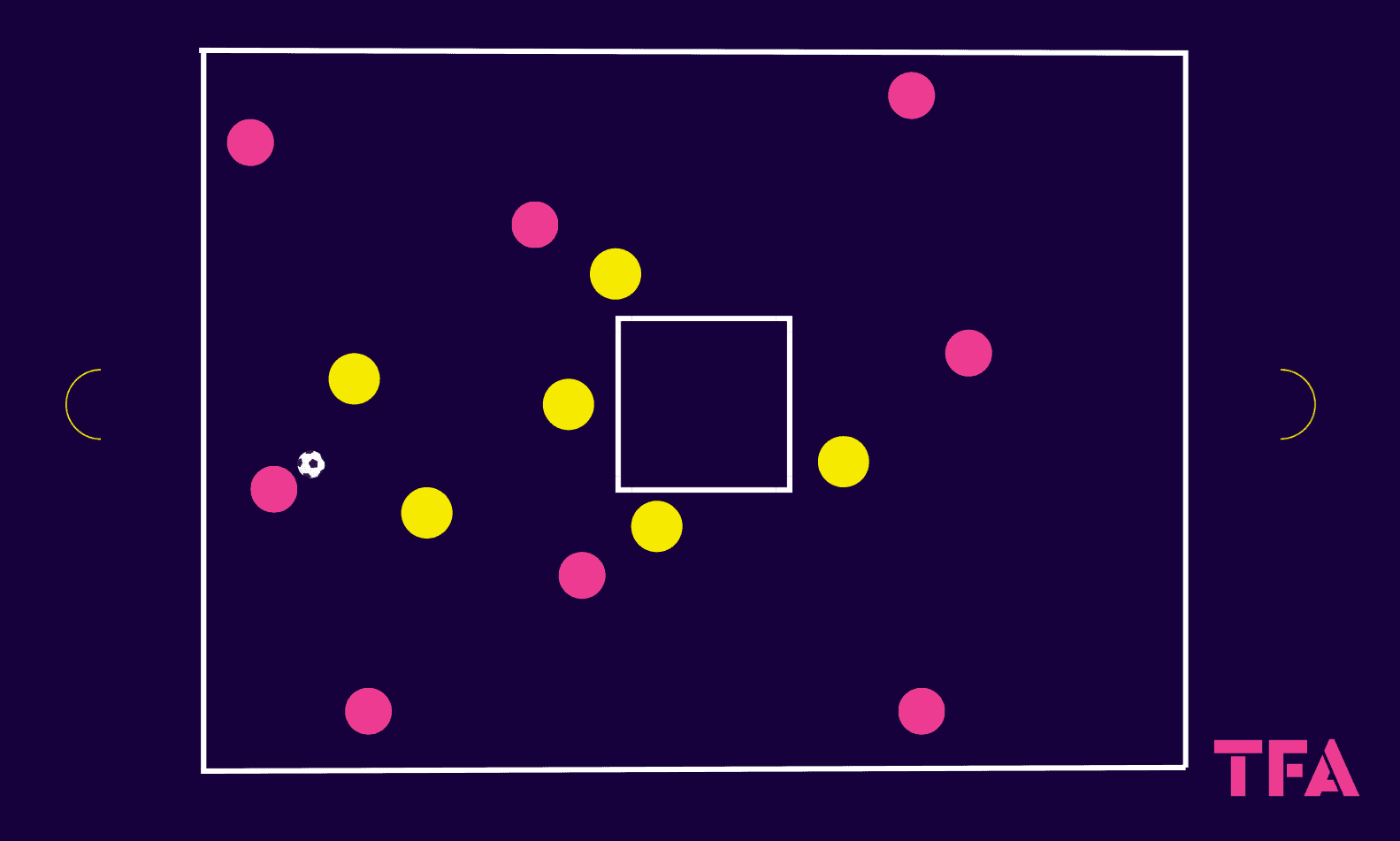

To train players to set that central passing trap and collapse on the checking player, we have a 40×40 meter grid with a 10×10 m square in the middle.

This is an 8v6 game. The eight attackers receive a point anytime they connect 15 passes (this number is adaptable to your team’s level) or with a passing sequence that sees them play into a teammate in that central square who can then play out of the square while keeping possession. To rephrase that second scoring opportunity, the attacking team has to play in and out of the square while keeping the ball. To work on the timing of the attacking move, use an offsides rule. If the second attacker enters the small square before the pass is played, he’s offsides. He must wait to make his move until the ball is played.

The defending team has two opportunities for points. First, they can score in one of the four mini-goals. Second, the defending team gets a point whenever the opponent manages to play into the square but the second pass, the one that leaves the square, is intercepted. This will help them improve their response time to that central pass. We want to communicate that it’s okay for the opponent to play into that space, but we have to make sure they can’t leave it.

Connecting the counterattack

Now that the first two sections have covered how to recover the ball let’s turn our attention to the counterattack. Following basic counterattacking principles, we want streamlined attacks that limit wide movements and square or negative passes. Any movement that allows the opponents to get numbers behind the ball will only decrease the odds of a successful counterattack.

The biggest point of emphasis is to use our tightly connected network to push forward. As the counterattack starts, the team in the attacking transition benefits from limited width, while the team in the defensive transition must recover from their expansive attacking shape. That positional superiority requires a sense of urgency from both sides, one to retain their advantage and the other to get numbers behind the ball.

As we speak to our players about counterattacking, it is important to emphasise more north-south movement rather than horizontal. It’s also important to note that one or two diagonals play an important role in getting behind the backline. Running on a straight line pulls the opponents near the ball, condensing the amount of ground the defending team can cover. Since they have limited numbers at their disposal, committing players near the ball often creates opportunities in the half-spaces for our third attackers. That’s exactly what we find in the example below. Värnamo uses a 5v5 in that first shaded area to draw opponents near the ball, creating a diagonal into the second shaded area.

Straight lines set up diagonal passes out of the press. That forces a recovery near the ball. As the defenders reposition themselves near the ball, space opens up for the remaining high players, like the five Värnamo attackers, to make untracked runs into the box.

Another key to the counterattack is to advocate for the first pass to go forward. Granted, there are situations where the only available option is negative. But even there, if the first pass is negative, the next one needs to go forward. We want to build a habit of hurting the opposition early in attacking transitions. The additional benefit is that we’ll train the players’ minds to respond with forward movements the moment the ball is won. That response time is vital.

The ball doesn’t have to go into the highest line; it just goes forward. In this Portugal vs. Uruguay example, when the South Americans won the ball, the first pass went in between Portugal’s lines and allowed their midfield to run at the backline.

Training the players on the timing of that next pass is key. It’s too soon, and you allow the backline to retain their shape and play the pass. It was too late, and the distance between the first attacker and his defender limited the angle to play through the press.

We need players to understand that as they drive at the backline, the goal is to get a commitment. Get one member of the backline, ideally a centre-back, to step forward and contest the ball carrier. The defender moving forward is the trigger. As he leaves a gap in the backline, we attack that space.

To train this attacking movement, we’re going to play the majority of this next game in the middle third. That will allow us to move from the mid-block to a counterattack. Move the goals up to the 18s and cut the focus team’s attacking half with a diagonal lane from the corner of the box to where the touchline is 10 yards beyond midfield.

This is an 11v11 game that is very much focused on one team. Our focus team will work on their mid-block and counterattacking. In terms of the mid-block approach, you can determine whether to emphasise funnelling wide or creating central pressing trims. Whichever approach you take, just ensure it’s connected to an efficient counterattack.

The focus group’s attacking half is on a diagonal to train direct moves to goal rather than settling for space in the wings. Ensure that it’s not just the forwards who are attacking the box. Help the midfielders and outside backs to see their opportunities, especially if they are the far-sided player. If they can offer a third-man run to get the team into the box, they should make that sacrifice for the team.

Make sure first passes are played forward as often as possible, that the receiver’s body orientation allows him to face forward immediately upon receiving the pass and that players understand the need to pin the next line to create space higher up the pitch.

Conclusion

A good counterattack always starts with the team’s defensive tactics. The way we defend is critical. Whether in the way we funnel play or in the traps we set, our defending has to create opportunities to go forward. This analysis of mid-block defending gives ideas for organisation and how to create recoveries.

It’s also connected to the counterattack. Winning the ball isn’t enough. Upon recovering possession, we have to be dangerous, hurting the opposition whenever possible. Linking with block defending to counterattacking in training will help build more fluid and dangerous counterattacks.

That was our goal with this tactical theory and coaching piece. Set the initiative and defence, then be dangerous getting forward.

Comments