The half-space is an area of the pitch in football which has been the subject of much writing from an offensive point of view, with its offensive qualities and advantages making it a frequently used and targeted area for build-up. Because of this, the half-space is obviously a key area to defend within football, particularly when facing teams who prioritise positional play, however there has been little writing around how to actually do this. With this looking like becoming a facet of football with increasing importance, it makes sense to consider methods of defending this space.

This tactical analysis presents methods and fundamental ideas which are vital to defending the half-space, taking lessons from the likes of Diego Simeone, Julian Nagelsmann, José Mourinho, Lucien Favre, Antonio Conte and many more.

Protect the centre first

A prerequisite to defending the half-space is to defend the centre of the pitch. The very reason the half-space is valued is because it offers some of the same characteristics as the centre of the pitch, for example a better field of vision and more passing angles. The centre is therefore the most valuable area of the pitch, and so naturally it needs the most protection. If you protect the centre, you can force the ball wide, which is often the poorest place to be on the pitch. If you then protect the half-space from here, then ball progression becomes very difficult for the opposition. Therefore, everything stems from staying centrally compact, and this piece incorporates this into defending the half-space, as the two are dependent on each other.

As a disclaimer then, this piece could also just be general methods of defending in a deep/mid block, as most teams specifically look to cover the half-space, but this piece focuses in detail the methods around limiting progression through this area in particular. The piece will also only focus on mid/deep pressing, as we are looking more at maintaining coverage of the half-space and limiting progression, rather than looking for ways to recover possession.

A key concept: Limiting responsibilities and overloads

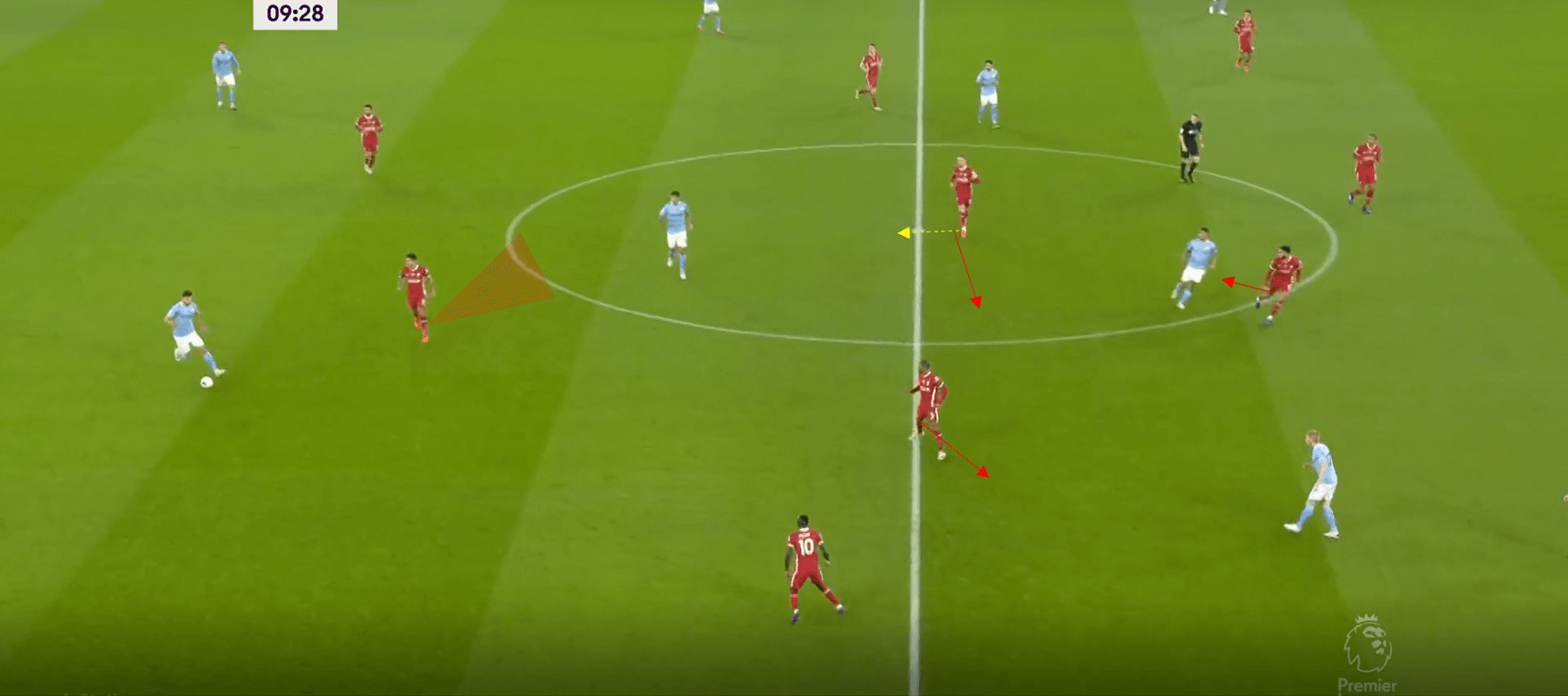

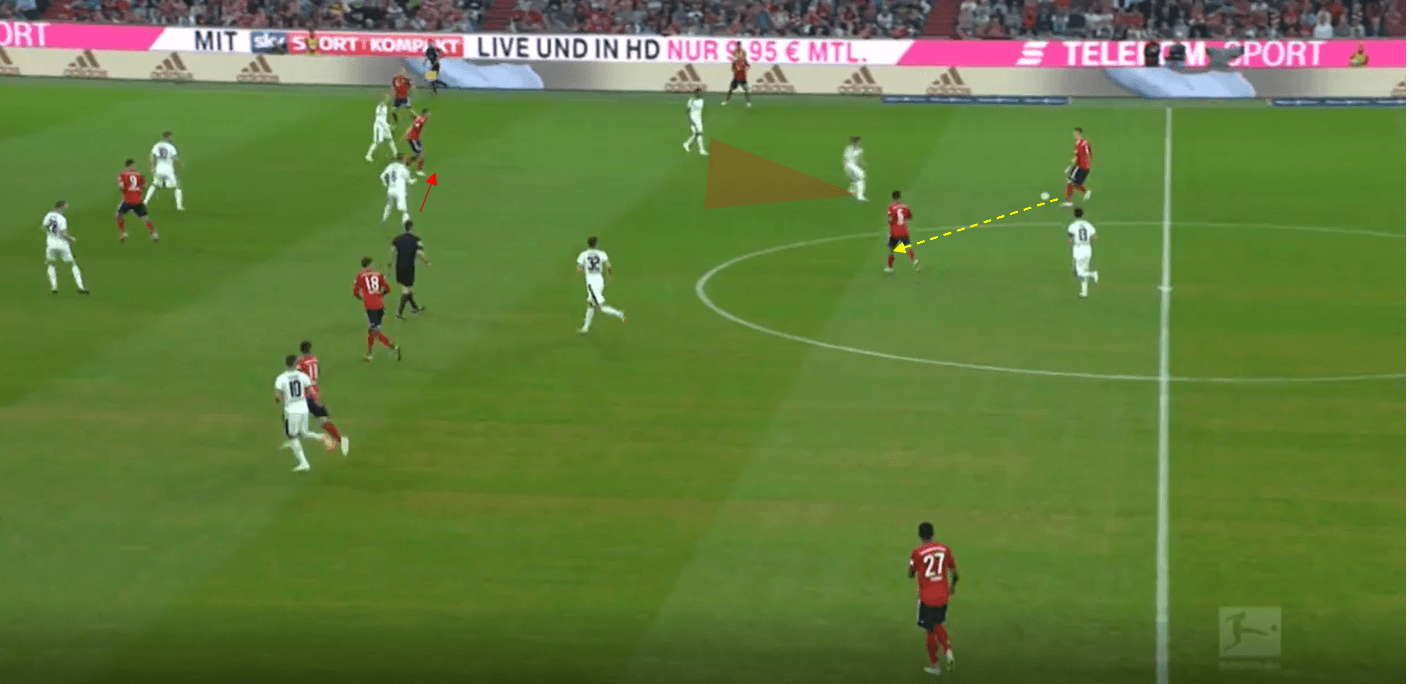

One of the key concepts that will feature in all of the systems in this article is the concept of limiting responsibilities. Within any pressing structure, an individual player has a role to carry out, and it is these roles which positional play looks to manipulate and exploit. Therefore, one of the key areas of defending in a compact shape is limiting responsibility on certain individuals. If you do this, you limit the ‘decisional crises’ that good positional play sides create. We can see an example here where limiting responsibility helps to increase coverage of the centre of the pitch. Here, Roberto Firmino cuts access to the Manchester City pivot with his cover shadow. This means that Jordan Henderson, the closest midfield player to Rodri, no longer has the responsibility of pressing Rodri if he receives the ball. As a result, he can focus solely on protecting the central lane by shuffling across, and there is no opportunity for Manchester City to create a decisional crises for Henderson.

It is a basic idea, but the less roles you can assign to defenders in key areas, the less likely you are to be overloaded. The following systems and ideas showcase how to do this.

Methods

The 4-4-2

The first system we will look at is the 442, which we have already seen briefly in the Liverpool example earlier. This is a system which has been used with massive success by the likes of Mourinho, Simeone, and Favre.

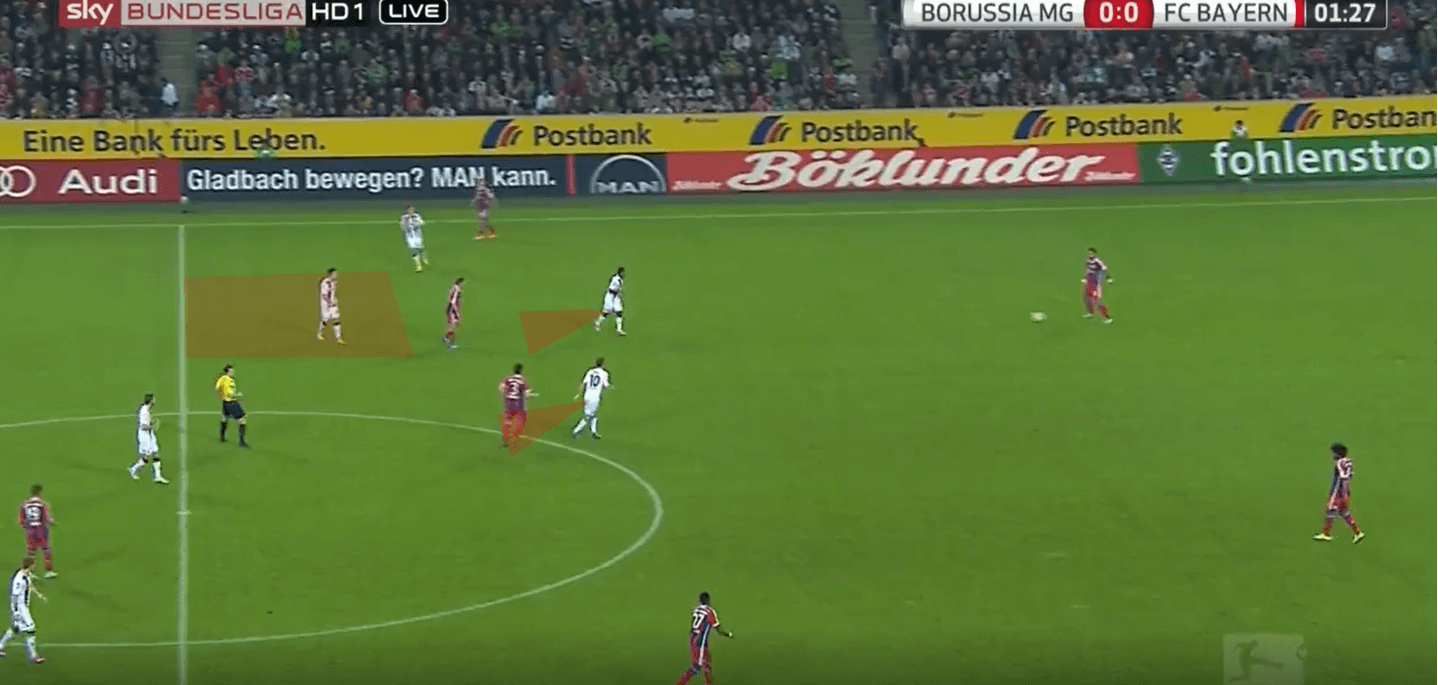

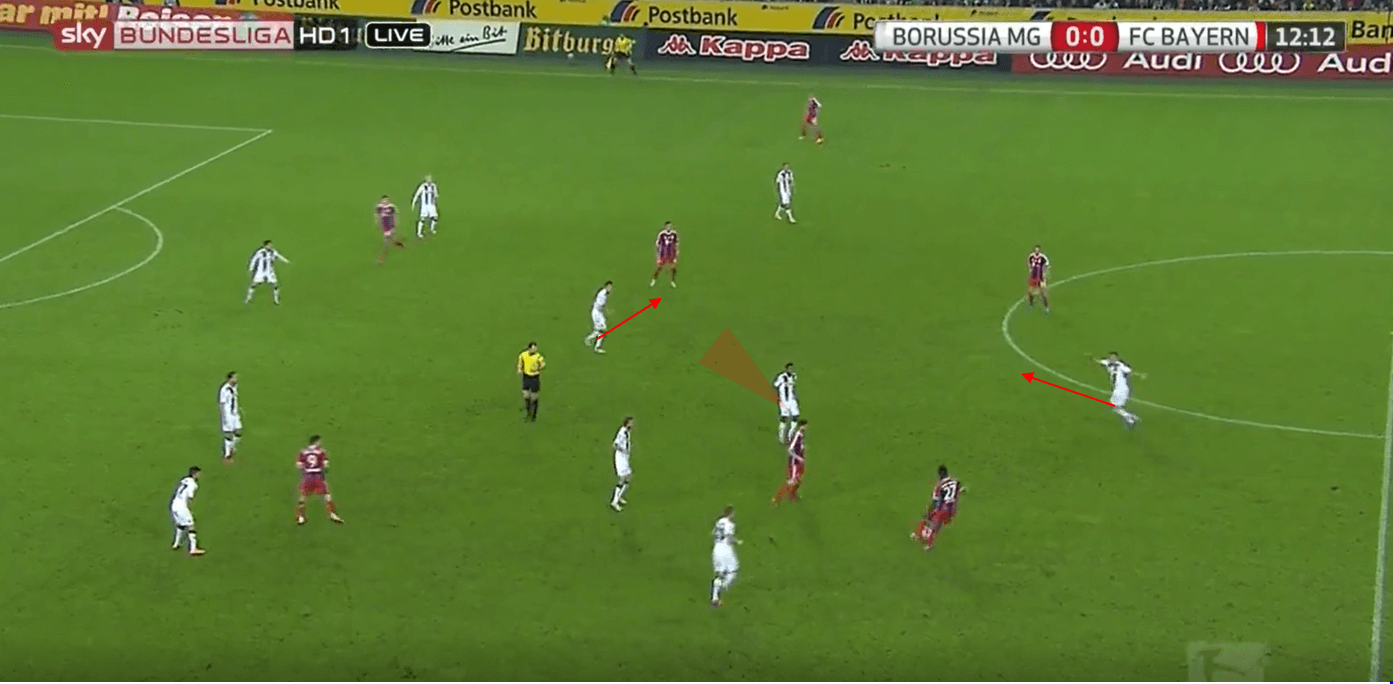

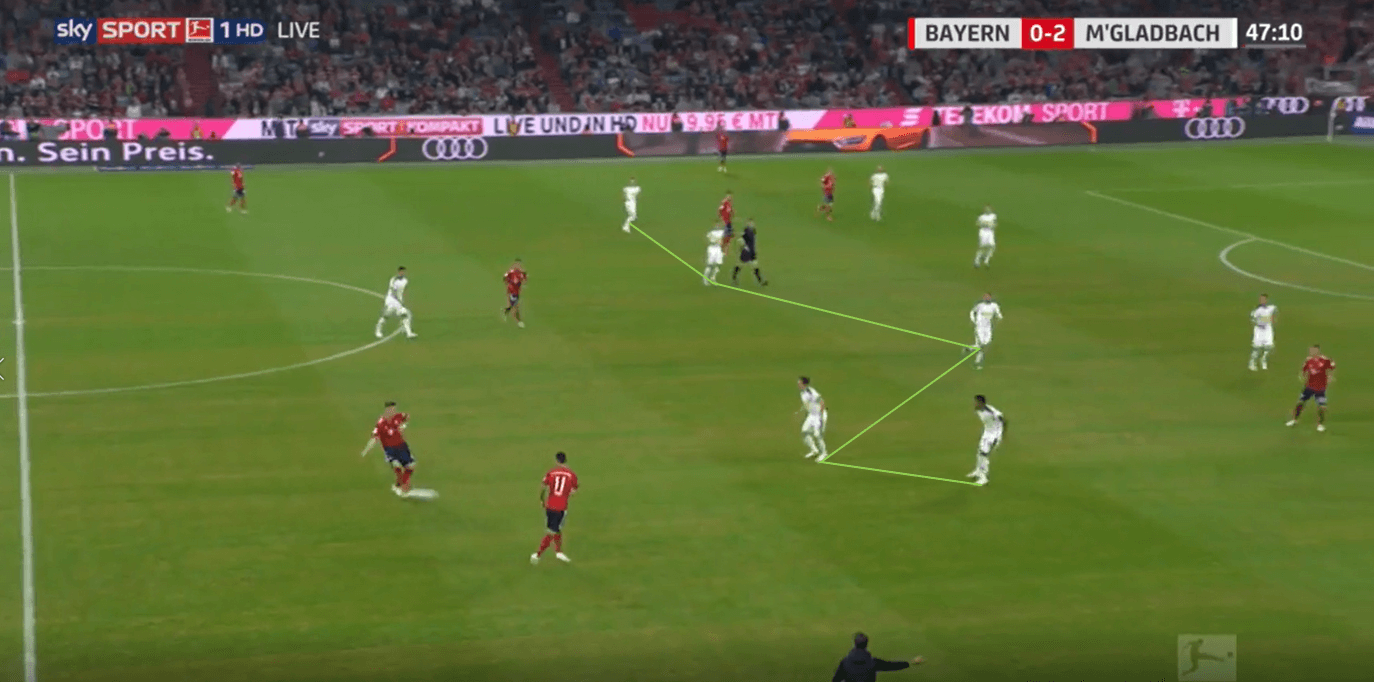

This example here from Favre’s time at Gladbach shows an ideal mid-block scenario for the 442. The two strikers drop off to become more passive, and instead cut the passing lanes into the Bayern Munich double pivot. The ball near central midfielder then simply has to cover the half-space as mentioned, while the wingers can press the full-backs or remain more passive, depending on the formation of the opponent.

This structure therefore cuts central access almost completely, and so the ball is forced either long or wide. When the ball is forced wide, the defensive team can stay in a stable shape, with the winger able to put pressure on the full-back, and the central midfielder able to cover the half-space without being occupied by a central midfielder in front. We can see an example here of this happening, with Herrmann here able to cut access to the half-space also by applying pressure on the ball. Gladbach remain vertically compact also which helps to limit space, and Kramer can cover the half-space and prepare to step forward with the whole defensive unit.

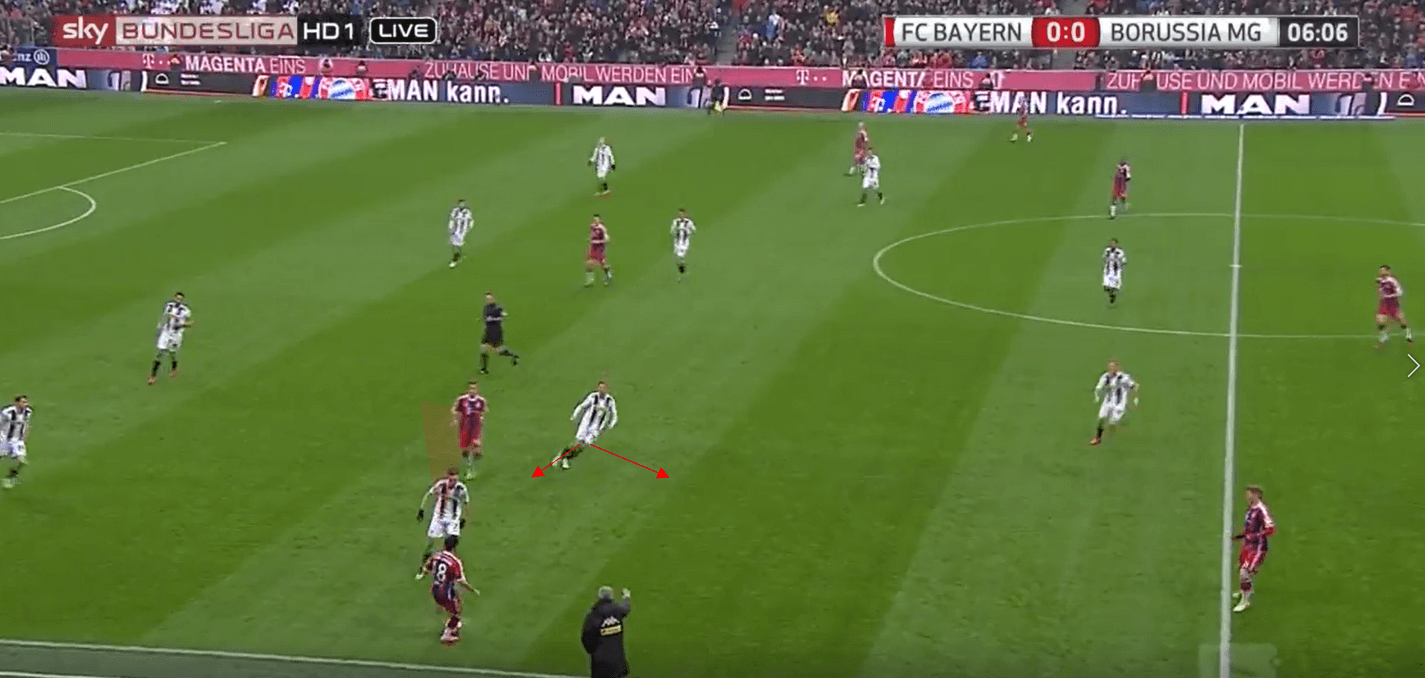

Another method Gladbach used to limit central play was to have their strikers back press to cut access into pivots, which we can see Raffael does here. This again prevents central play, and limits the responsibilities of the central midfielders.

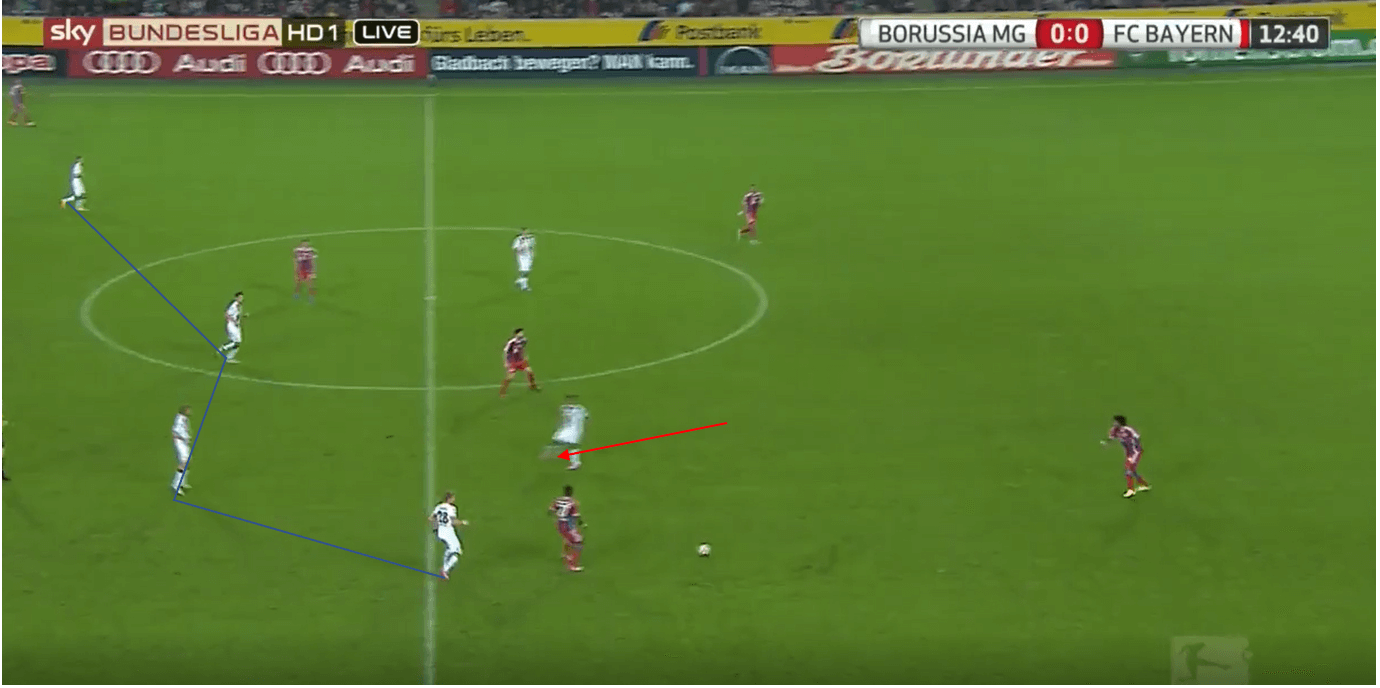

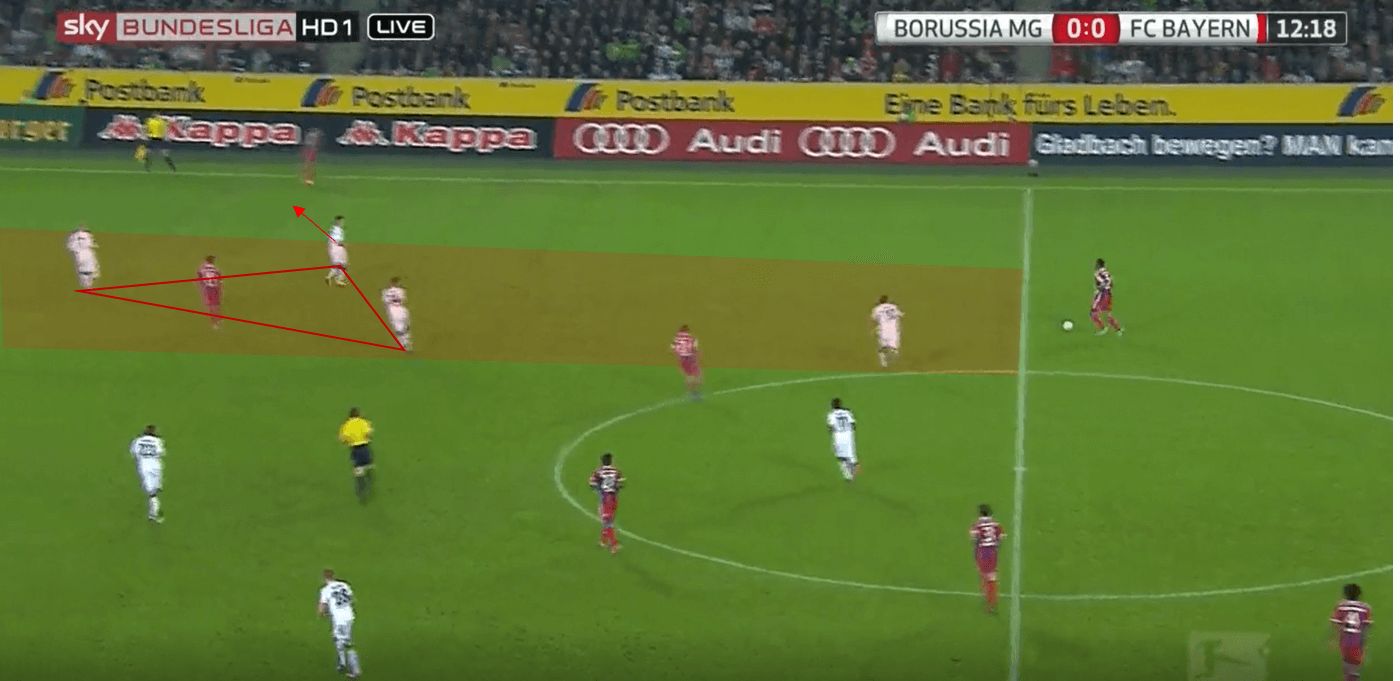

One of the disadvantages of this system is its use of only two central midfielders to cover the half-spaces, and as a result, defensive shuffling and compactness after switches in play is vital for the success of this system. In another example from Favre’s side we see here how they prepare to get compact on the other side. Nearby strikers back press to cut immediate switching options, forcing the ball back and then horizontally. Left central midfielder Granit Xhaka here can begin to shuffle across to the left thanks to Raffael’s positioning.

As a result, six seconds later when the ball is switch is about to be completed, Gladbach are in a very stable structure, with three players covering the half-space. Favre’s side were famous for their position oriented marking, where they moved as a block in the same direction and covered space respective to teammates. If you shift horizontally poorly, teams will find holes in the pressing structure.

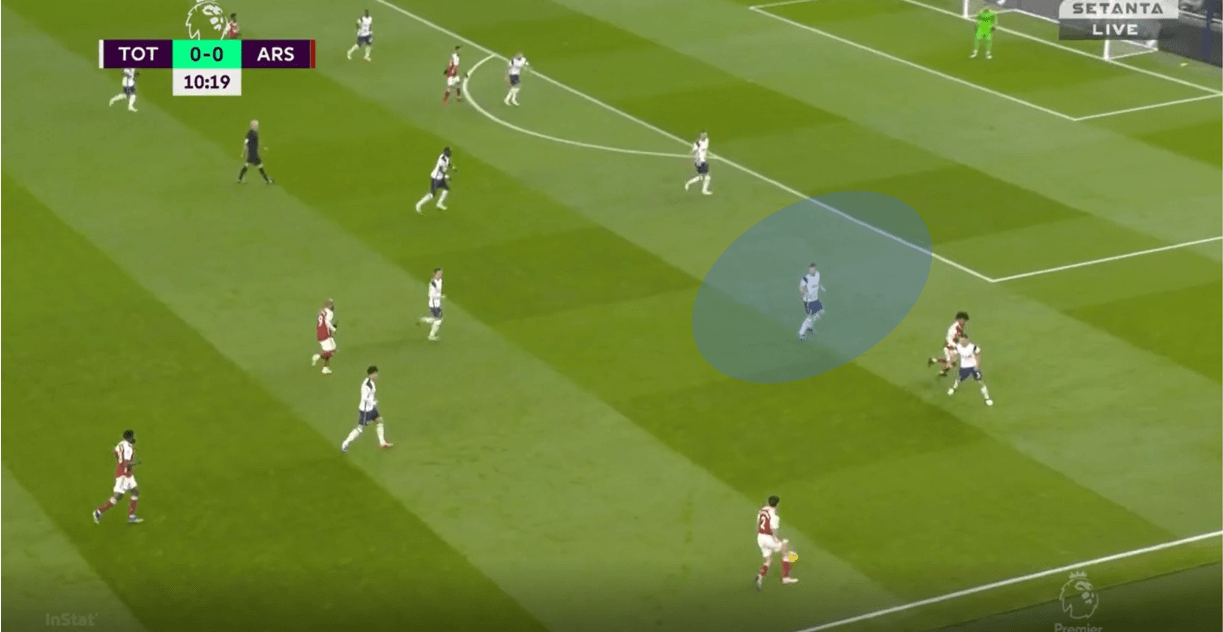

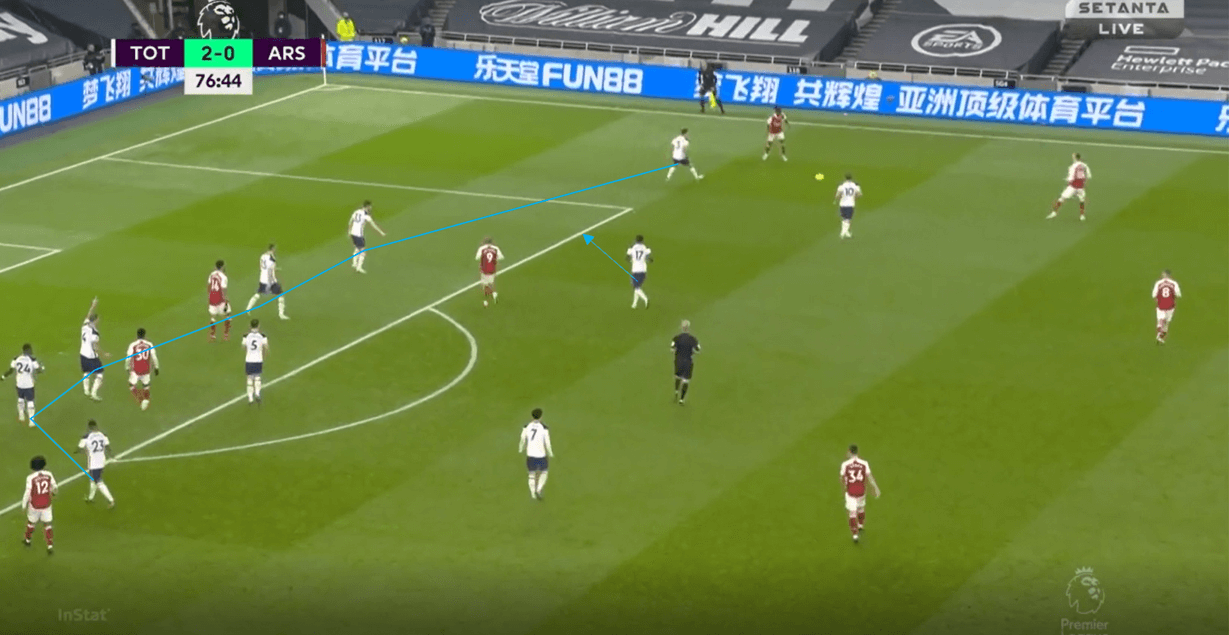

Mourinho’s central midfielders are generally deeper in the half-space, and will sometimes be just a yard or two in front of the defence, but their role remains the same, just that they may be slightly more zonally oriented than other teams, in that players will still cover the half-space if there is no immediate threat, as we can see here, with Højbjerg well prepared to occupy the half-space from deep, with the advantage of this being that he can cover players in front of him (which he can see), rather than having to defend space that is behind him.

A key factor in all back four formations is the roles of the wingers within a compact block, with another key concept of limiting space being to limit engagements. If the aim is to stay in a compact block and limit progression, certain areas of the pitch want to reduce how often they engage the opposition in a press, and the wingers and full-backs are particularly in this regard when defending the half-space.

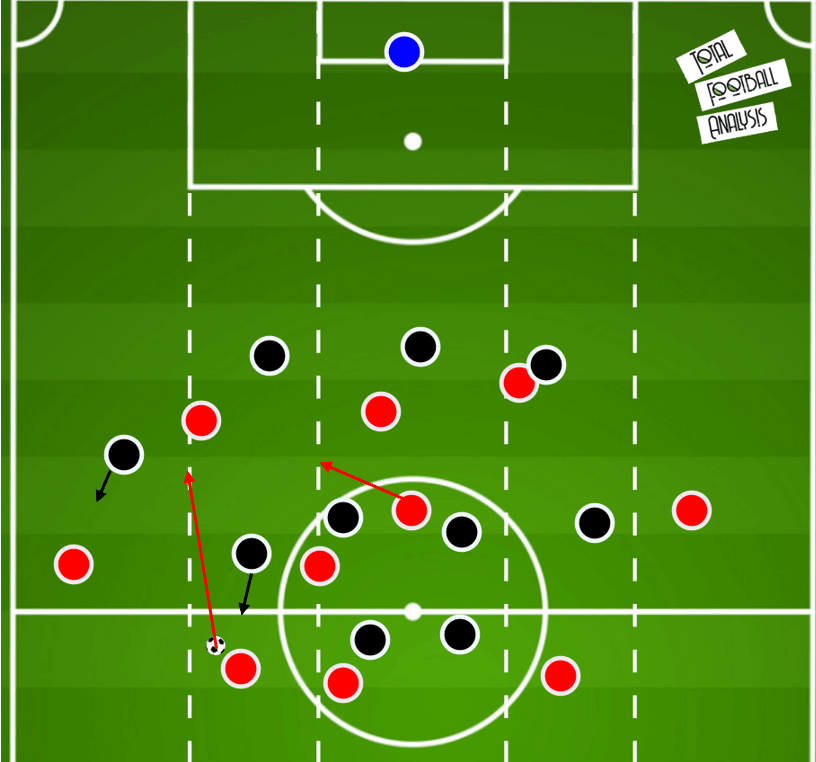

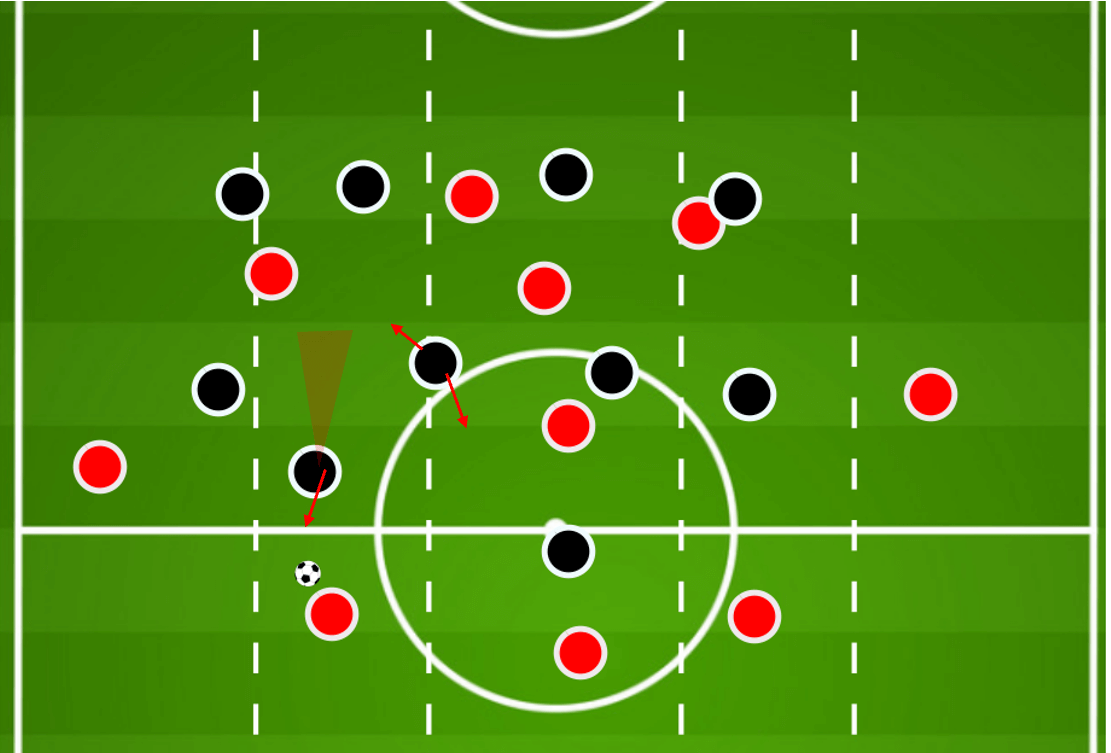

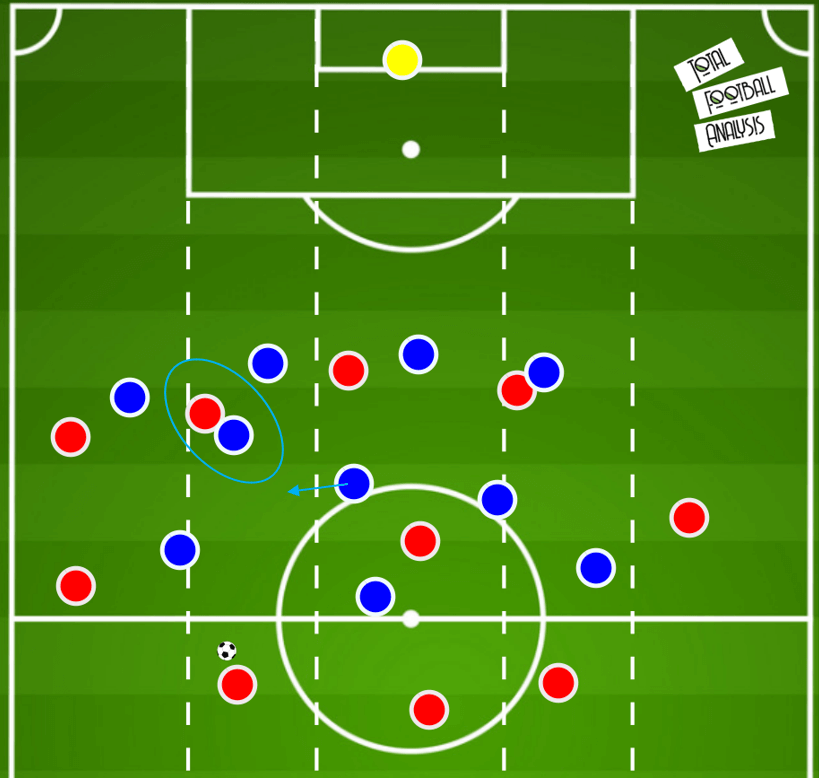

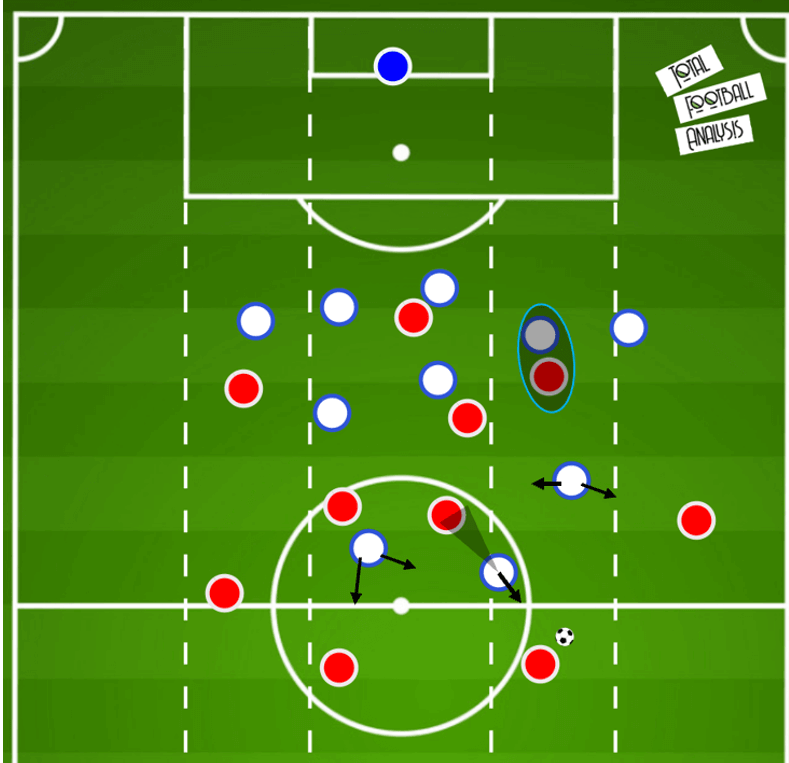

Limiting a full-back on full-back press is absolutely vital to maintaining coverage of the half-space, as we can see in this diagram below illustrating a bad press from the 442. Lots of teams will often drop into a back three with the aim of opening up the half-space, and we can see the team in red do this here. Against the back three, the winger now presses a wide centre back, meaning the full-back is now free in a very wide area. If the team want to maintain pressure on the ball, the full-back has to step up and wide to press, and so with the defensive winger narrower, and the defensive full-back higher and wider, the half-space opens. Furthermore, the defensive team now have a centre back occupying the half-space, who is likely to be matched up against a smaller, trickier inside forward.

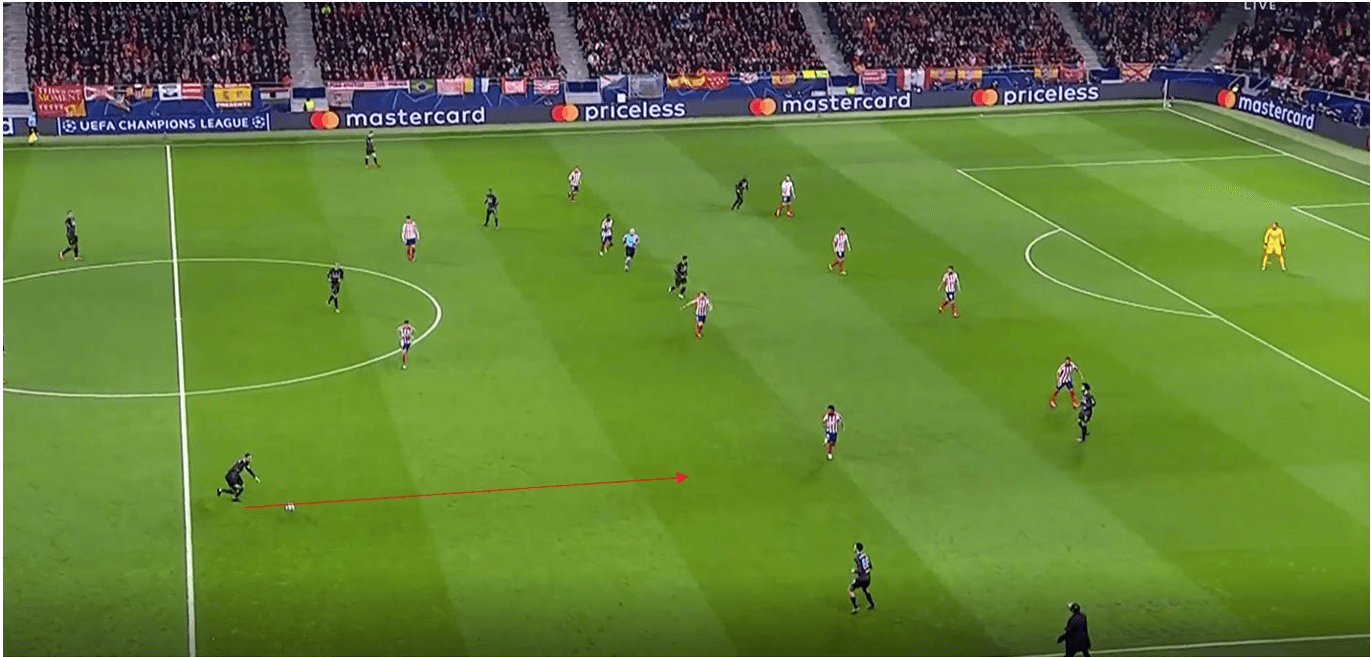

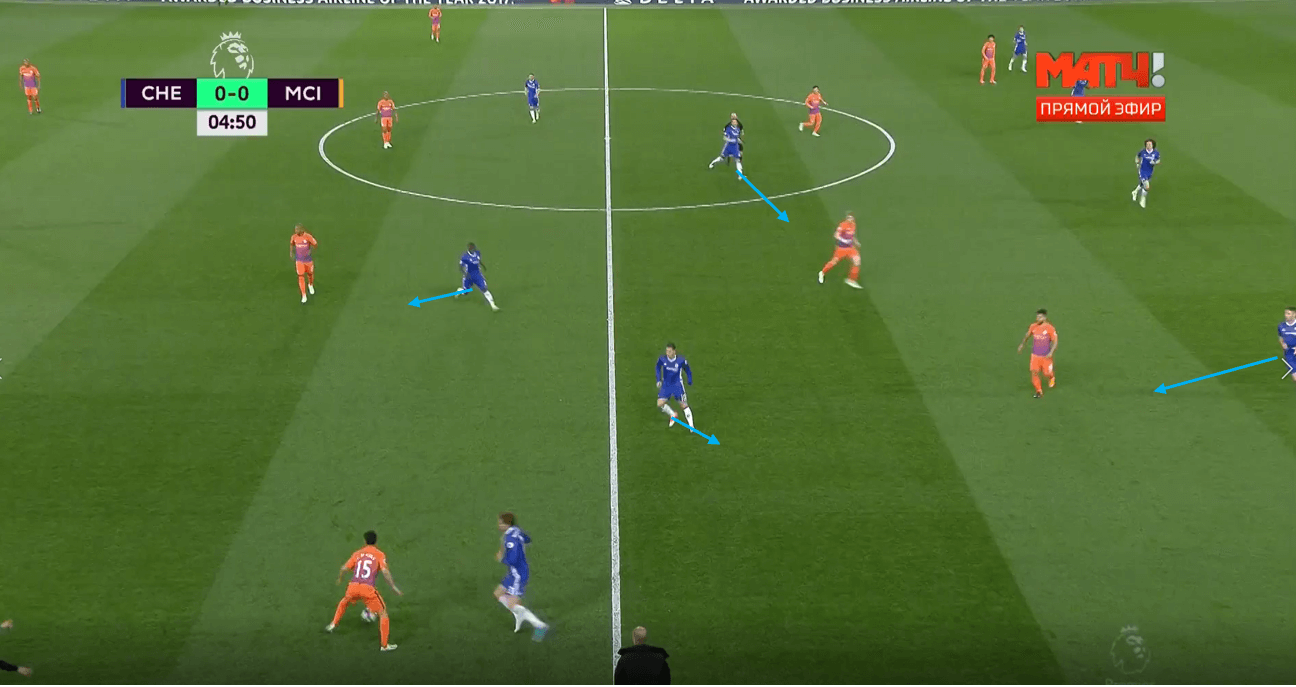

Atlético Madrid are usually excellent at preventing a full-back on full-back press, as their wingers remain passive and narrow in order to increase coverage of the half-space. We can see here Henderson picks up the ball as a wide centre back for Liverpool, and is given lots of space to move forward into. The left-winger is drilled not to engage Henderson in this situation, as doing so would open the half-space. Instead, both himself and the full-back behind him stay narrow until the ball is played wide, where they can then press the nearby players.

Mourinho’s wingers will become so passive at times that they will form a situational back six, with the midfielder tucking into the half-space, and the full-back becoming very narrow. This of course makes it very difficult to build through.

4-5-1 and its variants

The 4-5-1 naturally gives greater lateral coverage in the midfield line, however it also reduces coverage in the forward line, so how does the 4-5-1 look to limit half-space progressions? To answer this, we will look at Dieter Hecking’s Gladbach and Julian Naglesmann’s Hoffenheim.

In the particular game in question, a 3-0 victory away to Bayern Munich, Dieter Hecking’s side used a 4-1-4-1, although in pressing moments it would also switch to a 4-4-2. We can see their pressing scheme here in a deep block, with the 4-5-1 allowing for greater horizontal coverage in the midfield line. The widest central midfielder would often push higher to press the centre back, in which case the central midfielder (Kramer) would look to press across to cover the half-space. This example here is a nice one in that Neuhaus is able to apply pressure on the centre back and cover the half-space.

You could then call this shape a 4-4-2 with Neuhaus jumping, however jumping from this midfield line is a different proposition to acting as a striker. Firstly, the player is always pressing from in front of the centre back, which isn’t always possible as a striker. Secondly therefore, in theory, better angles can be covered around the half-space. We can see in this example here an example where the central midfielder gets their pressing angle perfect, and so the half-space is covered. The deeper central midfielder can step into the centre, or into the half-space for further cover.

The problem with this pressing scheme though is that the perfect pressing angle may not always be achieved, and having only one player covering the opposition back line immediately can reduce deeper central occupation and some pressure on the ball. Here for example, the pressing midfielder gets his angle spot on, and covers the half-space well. However, because he is arriving from deep and pressing from directly in front, the sideways pass into the central option becomes available. This could be solved by a 4-5-1-0 formation at times, with the striker marking the pivot, however this greatly reduces pressure on the ball. As a result, this system has its own advantages and disadvantages, as does the 4-4-2.

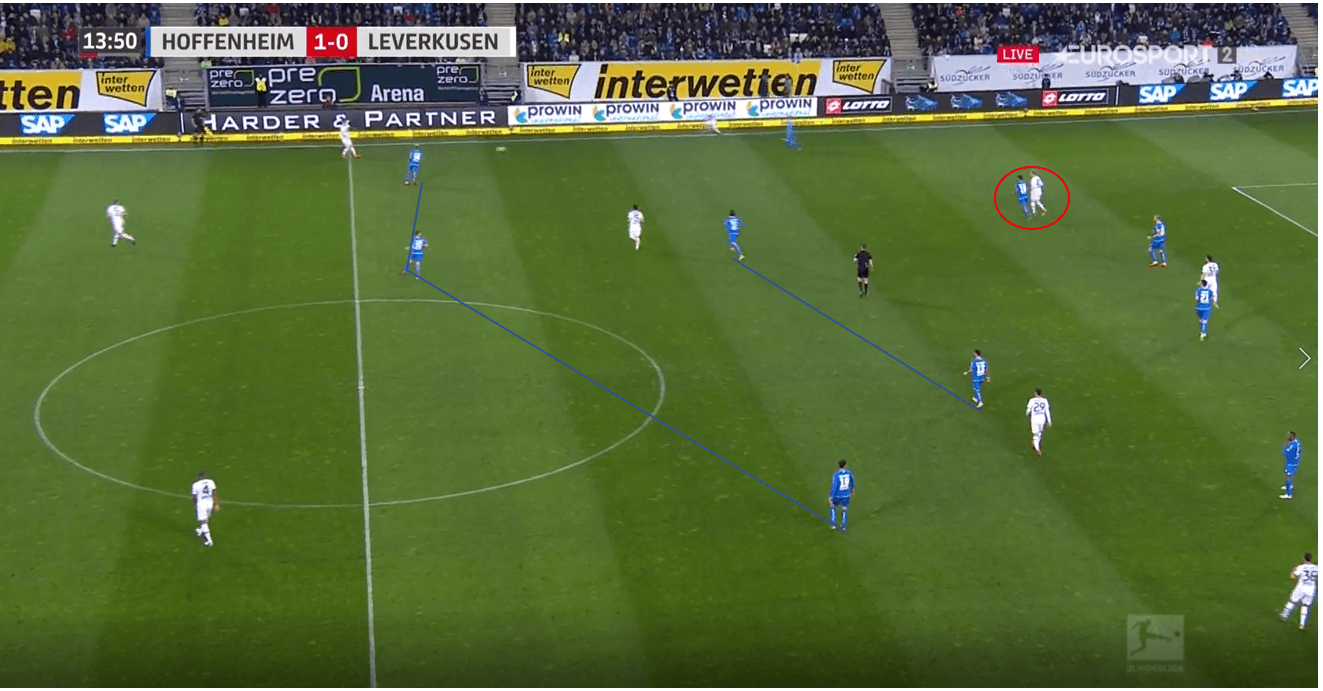

Against Peter Bosz’s Leverkusen, Julian Nagelsmann used a 4-3-3 which dropped into a 5-2-3 situationally. The front three would look to apply pressure to the Leverkusen back line, with the striker cutting off the lone pivot, while the wide forwards would press the full-backs or wide centre backs. Therefore, at times there would be a full-back on full-back press. However, the Hoffenheim central midfielders acted within the half-spaces, and would mark players once they moved into these areas no matter how deep they went. Therefore, Hoffenheim would often drop into a back five, meaning that the pressing full-back now had cover and the half-space wasn’t poorly covered.

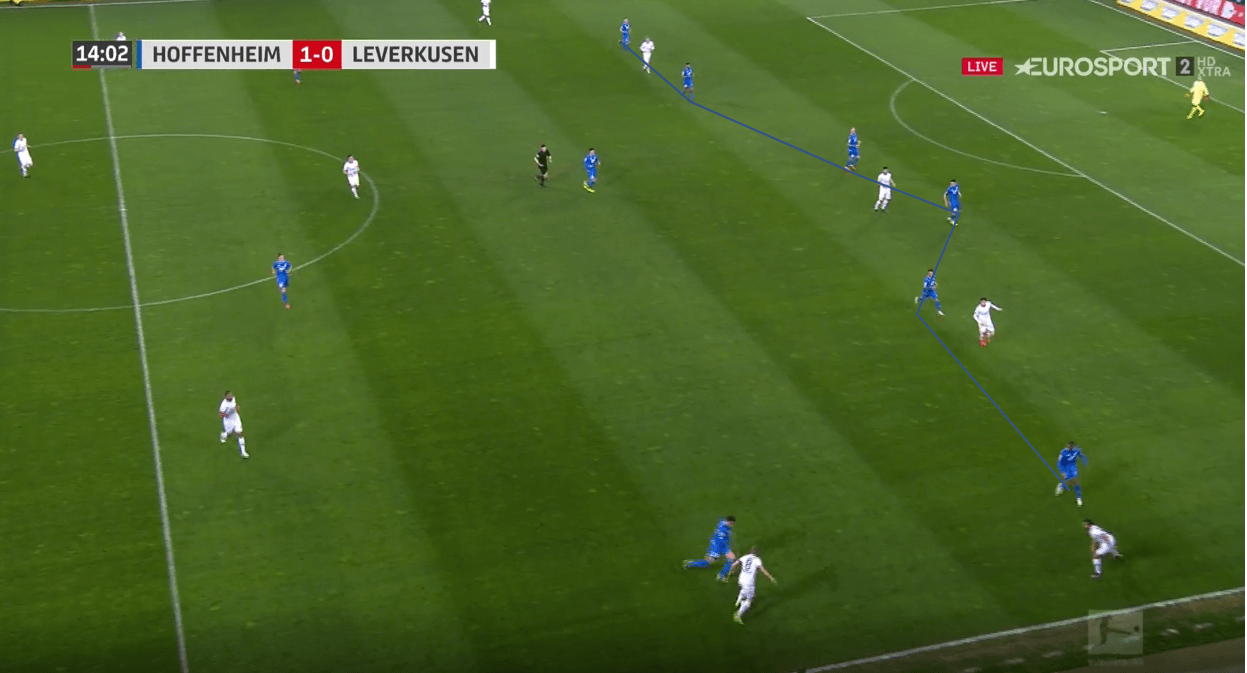

Here they even end up in a back six, due to Leverkusen switching from one half-space to another. The system fluctuates between a 4-3-3 and a 5-2-3 depending on the opposition’s movements in the half-space, and so because of it’s situational nature it becomes very adaptable in game.

Therefore even when the opposition create a structure like double width, the half-space can have ip to five players within it, depending on how narrow the full-back wants to tuck. If the opposition don’t create double width here and instead just invert one of these wide players, Hoffenheim still have a nearby central midfielder who can cover the half-space overload, which takes advantage of that increased horizontal coverage.

Back three systems

This fluid Nagelsmann system naturally leads us into looking at how back three/five formations cover the half-spaces. Here we can see a fairly traditional back five pressing structure, with wide centre backs often given the role of occupying inside forwards due to the increased coverage along the back line. This illustration shows Lyon’s pressing structure in the latter stages of the UEFA Champions League last season. They operated within a 5-3-2 and would look to cut access centrally to force the ball wide, where their ball near central midfielder would press wide, leaving the wide centre back and shuffling central midfielders to occupy the half-space. This system means that half-space occupation is virtually always existent by the centre-back, unless they are dragged wide, and so to play through it, this centre back has to be either dismarked or overloaded in both directions, which is difficult to do, as Manchester City and Juventus found out.

To reduce responsibility on the centre backs, Antonio Conte often used a 5-4-1 formation in which midfielders provided excellent coverage of the half-space to limit progression. The shape would act like a conventional 5-4-1 at times, but a particularly interesting tactic massively helped to limit progression- favouring a wing-back on wing-back press.

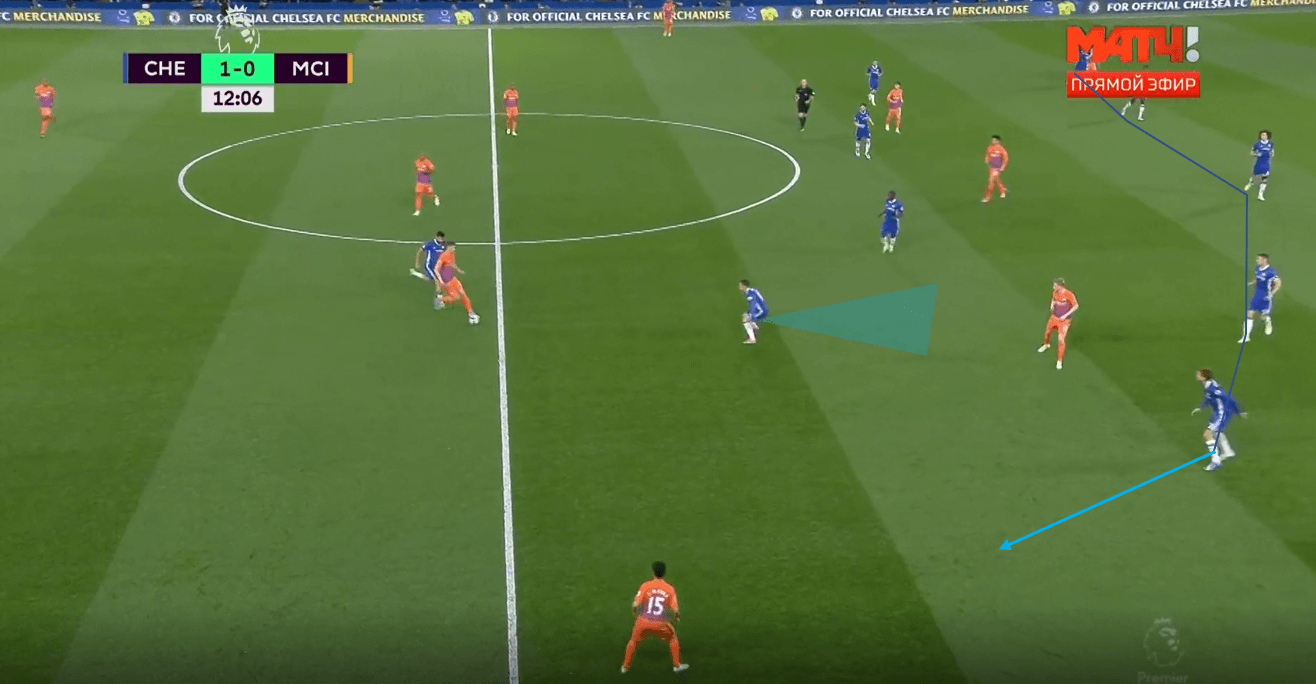

The aim of this was to increase the winger’s half-space coverage, which in turn helps to protect the wide centre back. We can see an example of this pressing scheme below, where Eden Hazard stays very wide here while Alonso gets ready to jump and press the City full-back. In a conventional 5-4-1, you would rely on the ball near central midfielder and centre back to cover the half-space here.

The main danger of forcing a full-back to engage high is that the half-space is left open due to the winger also committing, however if the winger doesn’t commit, you are left with more occupation of the half-space. Chelsea therefore jump into a 4-5-1 all of a sudden due to Alonso’s jump, and so Hazard can now tuck in to cover the half-space, while N’Golo Kanté can press higher to cover the pivot here if needed. This job could also be fulfilled by the striker, leaving Kanté deep to protect the half-space also. The positioning of Hazard here limits ball progression through the half-space massively, and so City are forced backwards.

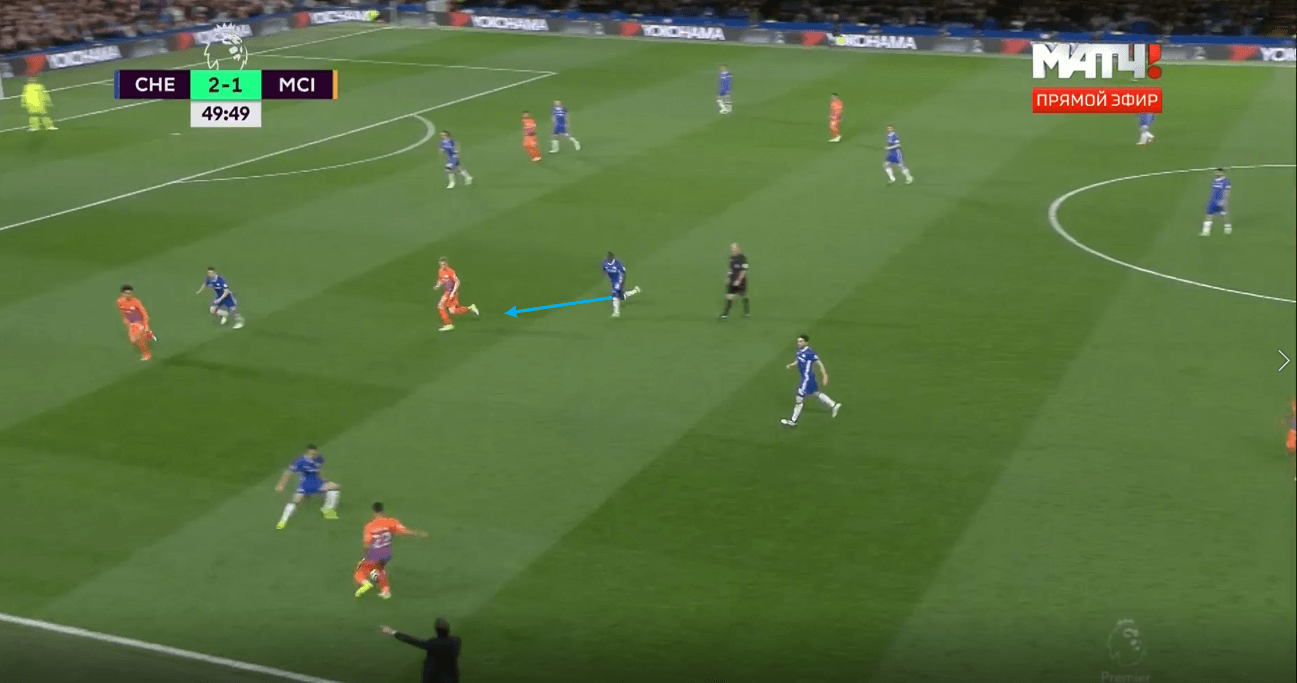

Here, even when Manchester City create double width, pinning the full-back deeper and forcing the winger to press wider, the ball near central midfielder is able to come across and cover the half-space. City work the ball down the line, but by this point the near central midfielder has easily recovered to prevent the ball being progressed.

Conclusion

This analysis has sought to look at a few methods and tactics good defensive teams have used to limit ball progression both generally and around the half-space. This tactical theory piece only tells a small part of the story around these defensive systems, as another large factor to consider is how to either win the ball from such scenarios, or how to then attack from them. The topic of pressing traps within the half space (and whether this is a good idea) is something I am experimenting with at the moment, and so I will likely write about it in the future.

Overall then, the half-space is a sought after area of the pitch by positional play sides, and with fans of this style of football growing over the last decade, it only makes sense that methods of limiting such teams have also become of interest and had success. A key part of any defensive side’s success is their inability to limit progression, and with the half-space being a key area for ball progression against deeper blocks, knowing how to stop this is a useful tool to have, with this analysis hopefully triggering an interest to consider this topic more.

Comments