We often hear of these infamous chats between some of the greatest minds in football behind closed doors.

The likes of a story detailed by Bayern Munich’s former technical director Michael Reschke describing a chat between Pep Guardiola and Thomas Tuchel in a bar in Germany, discussing nothing but tactics and football philosophy over some wine spritzers. Oh, to be a fly on that wall.

Tuchel was the head coach of mid-table Bundesliga side Mainz at this time while Pep oversaw the biggest superpower in German football. The former was able to pick the mind of one of his coaching idols for an entire evening, something many of us could only dream about.

For most of us, having a chat with a master tactician isn’t very accessible. But what if you lived with them? Or better yet, shared the same blood.

While not many elite managers have close relatives who set down the same path of football coaching, there are a few. One can only imagine how much fun Christmas Day is around their house, dissecting different strategies and coaching methods over some mulled wine and crisp turkey.

But do they all think the same?

The idea behind this tactical analysis piece isn’t to go through every coaching family in the professional world but to take a few examples and analyse their teams’ tactics to see if there are major philosophical similarities in their ways of playing.

To add further context, pairs such as Carlo and Davide Ancelotti will not be included because there’s no evidence of Davide’s tactical identity yet other than working under his father’s wing for several years while coaching families such as the Cruyffs, Cloughs and Fergusons will not be included either as each manager will still need to be actively working or seeking a job as of writing. Also, it would be rather distasteful to compare Jordi, Nigel and Darren to their fathers’ illustrious careers.

However, the Inzaghi, the Schreuder and the Still brothers are certainly on the table.

Are there obvious similarities in each of their tactical philosophies? Let’s find out in this tactical theory piece.

The Inzaghis

Simone Inzaghi made a great career for himself as a player — one that many would be jealous of.

In 2000, whilst playing for Lazio, the Biancocelesti won Serie A under Sven-Göran Eriksson, lifting the crown for the first time in 26 years, a time before Inzaghi had even been born.

The Italian striker had an excellent season, finishing as Lazio’s top goalscorer in a team comprised of stars such as Pavel Nedvěd, Diego Simeone, Roberto Mancini, Dejan Stanković, Juan Sebastián Verón, Alessandro Nesta, Sergio Conceição, Siniša Mihajlović, Marcelo Salas, Matías Almeyda and Fabrizio Ravanelli. Wow.

Unfortunately for him, it was Simone’s brother who stole the limelight for most of their simultaneous careers.

Filippo went on to become a two-time UEFA Champions League winner, a three-time Serie A winner, a holder of a World Cup winners’ medal and one of the greatest Italian goalscorers of all time, casting his brother into his shadow in the meantime.

Nevertheless, when it comes to management, it is Simone who trumps his legendary brother, currently managing UCL semi-finalists Internazionale while Pippo battles it out for promotion in the deathly gallows of Serie B with Reggina.

The two Inzaghis faced off against each other eight times during their playing careers and thrice in management. Pippo had the upper hand on his brother as a player, being on the winning side three times to Simone’s two. However, the latter has never lost to his sibling as a manager, winning twice and drawing once.

Let’s look to see if there are any statistical similarities between the two sides this season under the guidance of the Inzaghis.

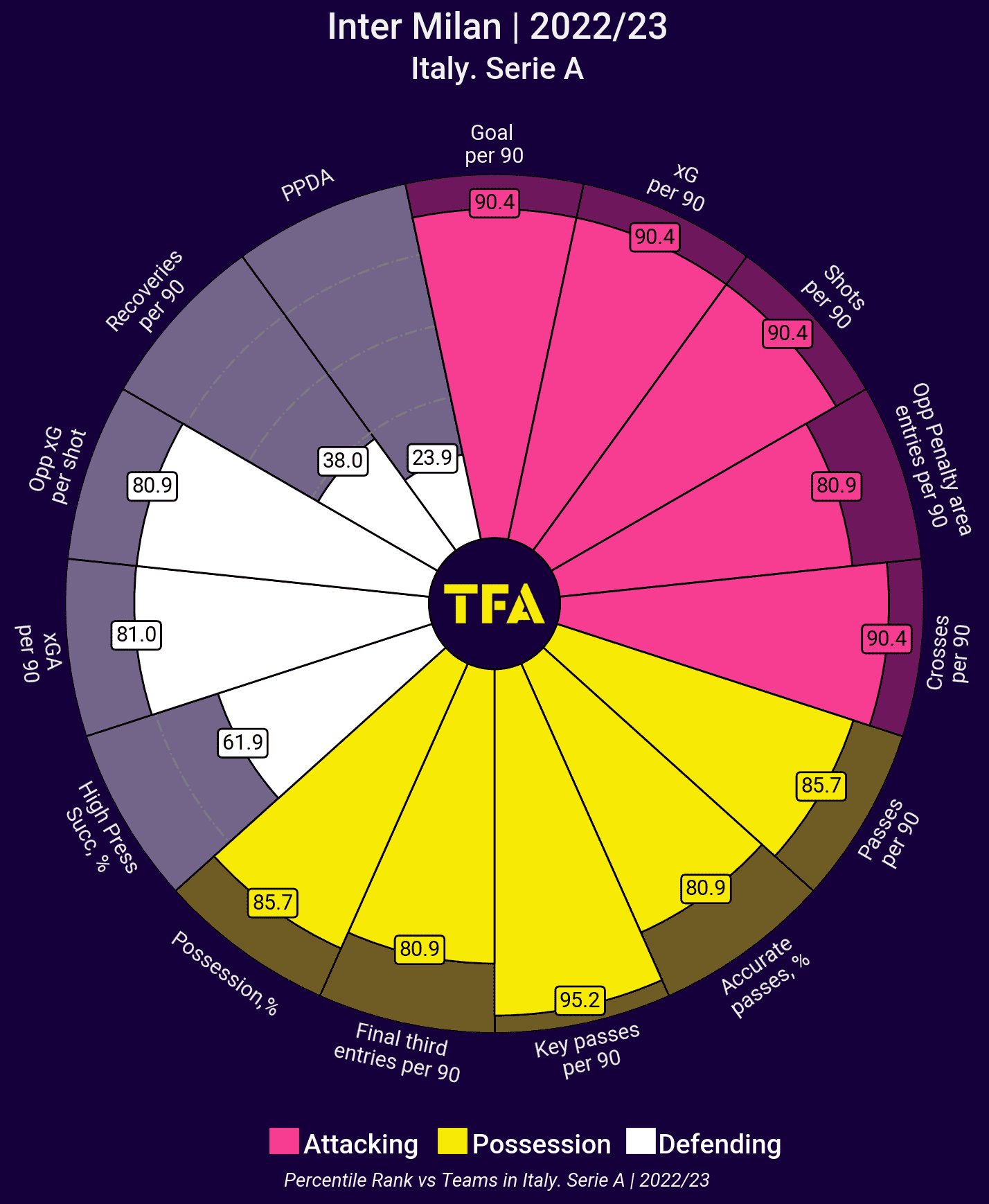

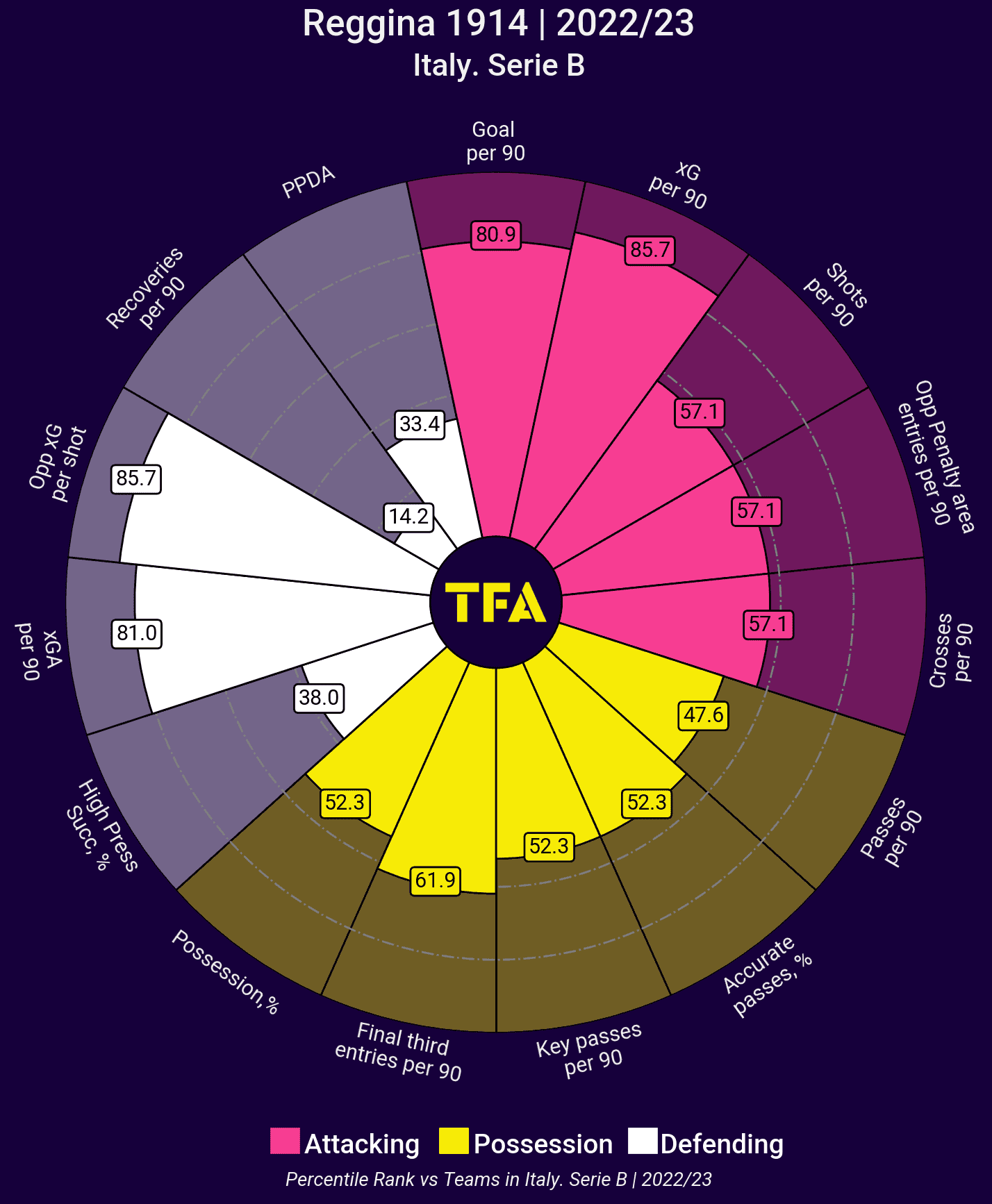

There really aren’t that many statistical similarities between Inter and Reggina this season apart from their ability to score lots of goals in each respective division while also conceding quite a lot of chances at the other end.

Simone Inzaghi is far more adamant about his side having possession of the ball. At Lazio, this wasn’t always the case, particularly in big games, but there is much greater scope for integrating a possession-oriented style now given the quality of the players.

The same cannot really be said for his brother. Flippo Inzaghi has always been more pragmatic of the two. The style depends on the players available, according to the man who was born offside.

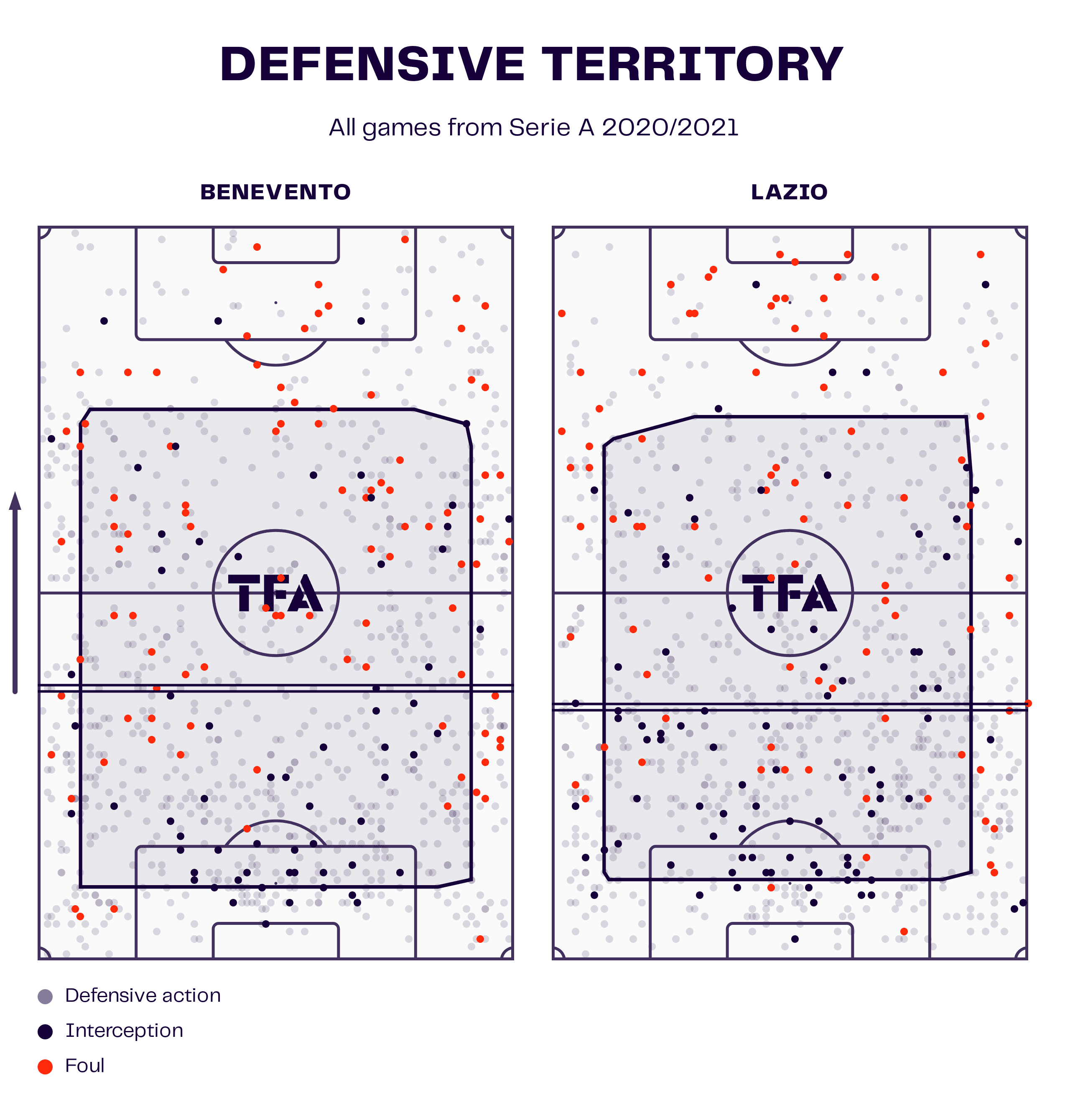

The last time the two men faced each other in the dugout, their footballing ideologies could not have been any more different. It was a thrilling 5-3 game won by the hosts Lazio and Pippo’s Benevento held just 42% of the ball.

The strategy throughout was to sit in a compact 4-3-2-1 mid-block which became a 4-4-2 low block as one winger dropped further back and the other tucked inside.

Throughout the entirety of the 2020/21 season, Filippo’s Benevento registered one of the highest PPDA figures in Europe’s top-five leagues at 15.03, showcasing a lack of willingness to press the opposition. Passiveness in the defensive phase was a criticism thrown at the World Cup winner during his time at the Stadio Ciro Vigorito.

Benevento were really passive out of possession, looking to soak up pressure and hit teams on the break. But they weren’t the only team in Serie A who fit into this bracket.

In fact, when analysing Lazio’s average defensive line height, it was deeper than Benevento’s. Simone Inzaghi’s side also recorded a PPDA of 12.85 which was higher than Sean Dyche’s infamous Burnley.

While the two men may have coached teams with very different quality levels, both were not massive advocates for pressing high up the pitch. The Inzaghi brothers preferred to drop off into a compact mid-block.

However, upon taking the reins at the San Siro with Internazionale, Simone decided he wanted to start defending higher up the pitch. Perhaps this was because he believed that he now had better defenders than during his time with Lazio, but the difference is stark.

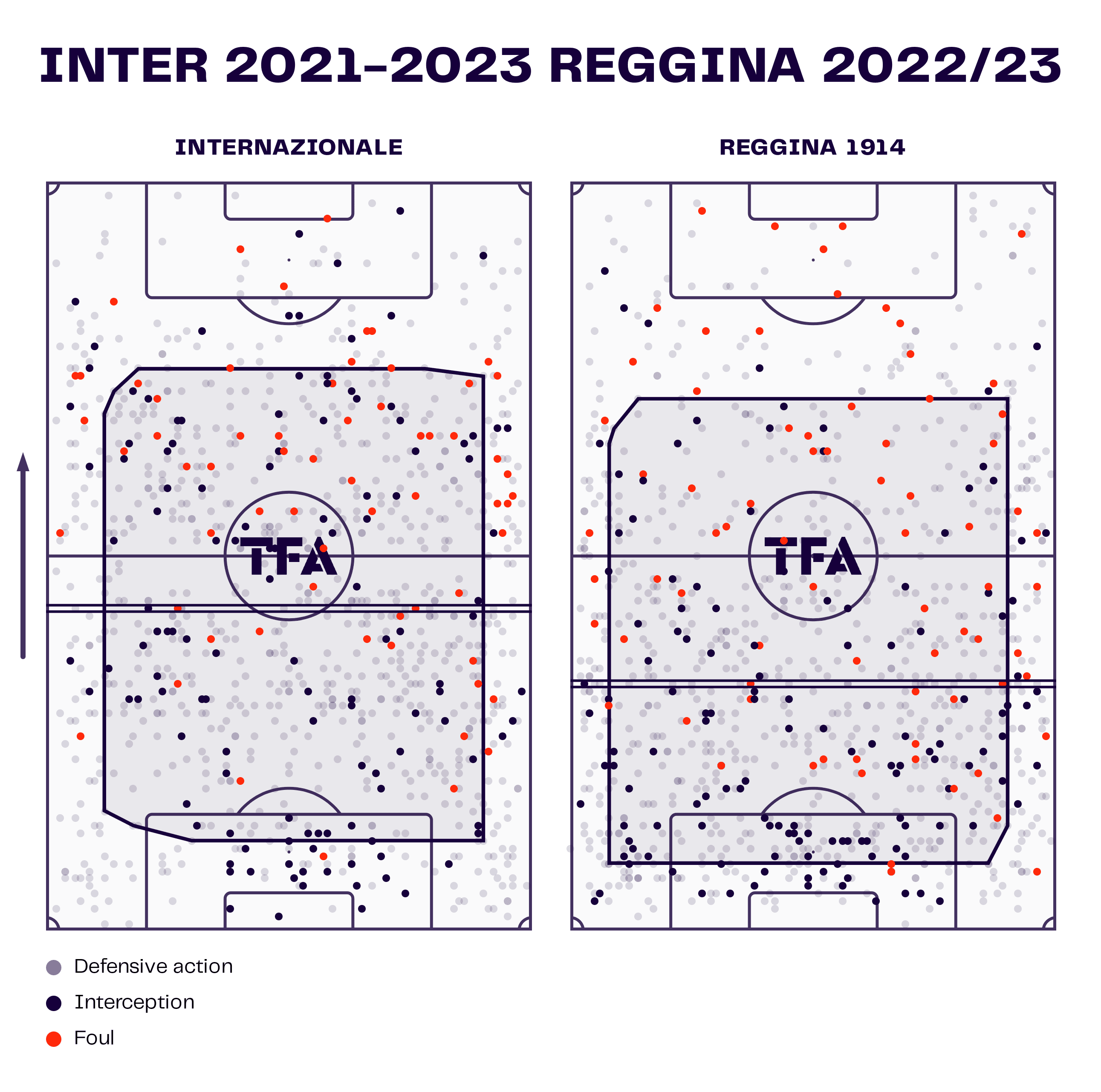

The Nerazzurri defend very high up the field, close to the halfway line on average, while Filippo Inzaghi’s philosophy has gone in the opposite direction with Reggina defending in an incredibly deep low block.

For a manager with such an emphasis on defending lower down the pitch, Reggina have conceded the second-highest number of goals in the top half of Serie B. Leaking goals has always been a problem for Pippo’s teams, hence why he lost his job at Brescia last season too.

The midfield was often far too easy to play through, which in turn caused gaps to open up as the centre-backs would be forced to step up and cover.

On the flip side, Inter have the sixth-best defence in Serie A currently and have conceded the fourth-fewest shots on average per 90 while boasting a PPDA of 8.98 — the third-lowest in Italy’s top-flight.

Defensively, the two brothers could not be any more different right now. Although, there is a little bit more similarity in how their sides build up from the back.

Granted, one must keep in mind that Inter are averaging 56.1% of the ball per game compared to Reggina’s 49.9. Their philosophy in this respect is quite the contrast. But we did find similarities in how they set up their teams during the build-up phase.

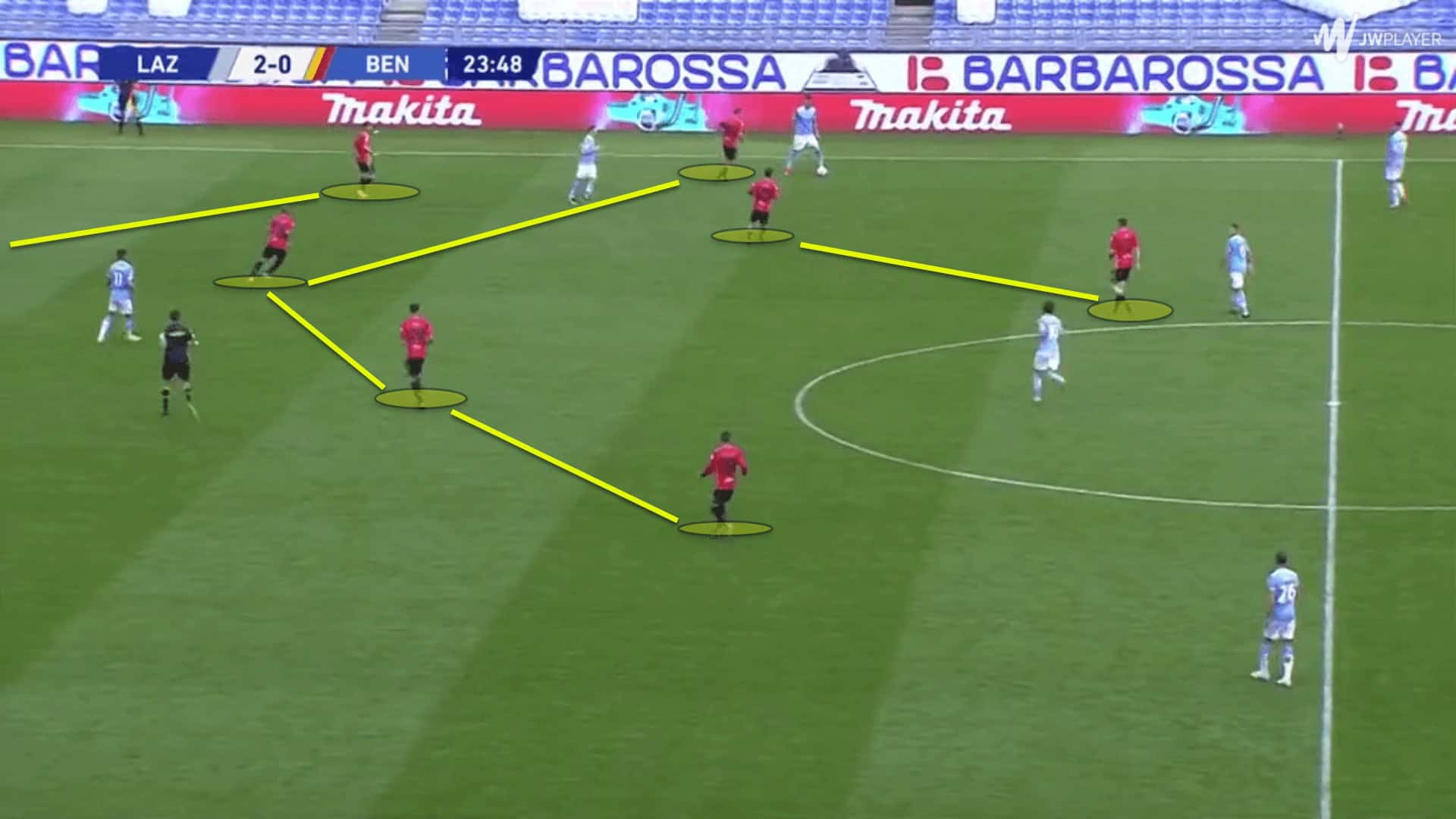

A common variation for Inter when passing it out from the first third is by pushing the central centre-back into the second line behind the opposition’s first line of pressure, offering an extra progressive passing angle to break the press. This has been highlighted in the previous screenshot.

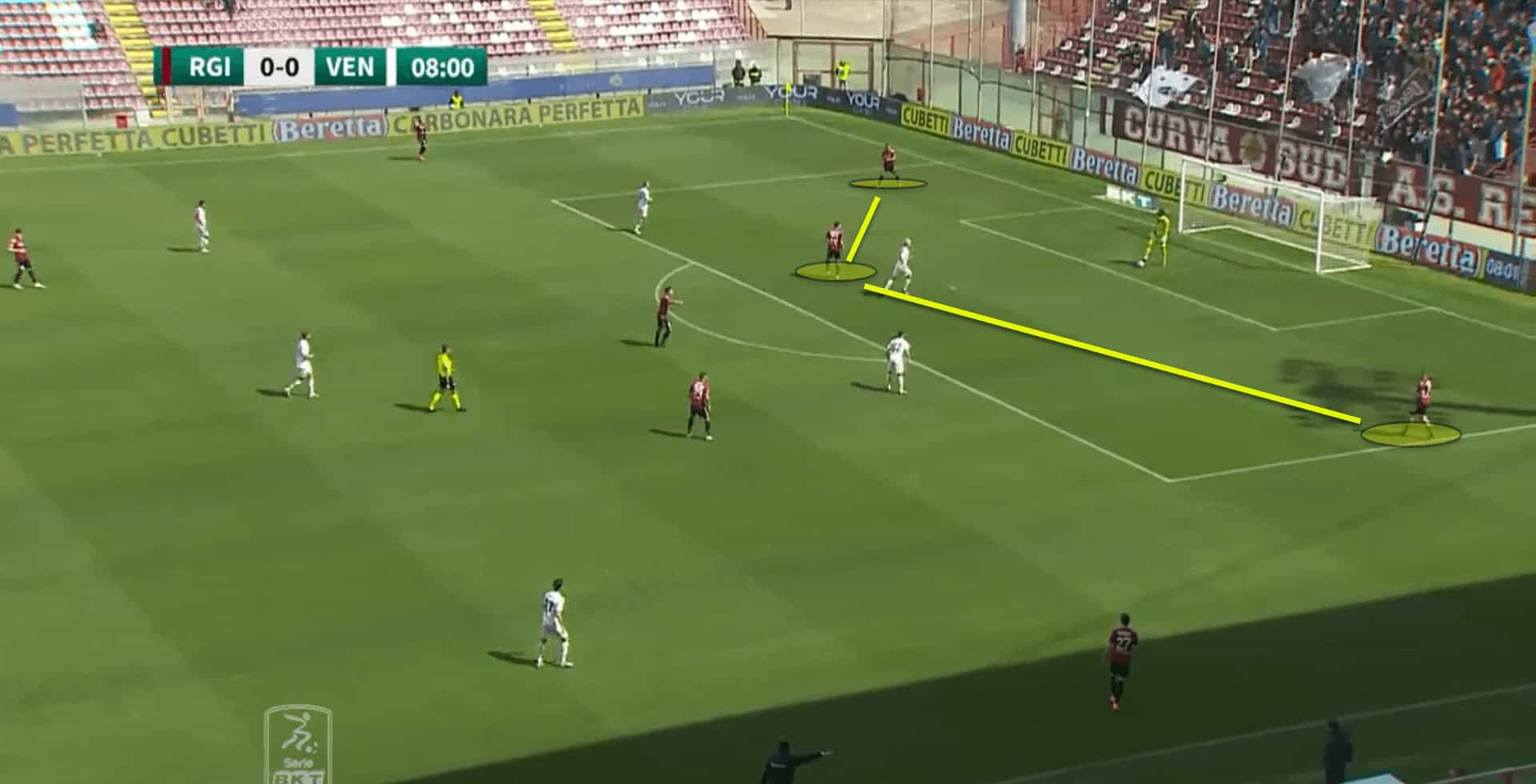

When analysing Pippo’s Benevento and Brescia, none of these variations were present. However, let’s look at Reggina from a recent 1-0 win over Venezia at home — a game in which he deployed a 3-5-2 instead of his preferred 4-3-2-1 (4-3-3).

Notice anything? Well, we hope you have because it’s been annotated in the example. Reggina’s central centre-back was pushing up behind the opposition’s first line of pressure, causing the build-up shape to look more like that of a 4-3-3 as opposed to a 3-5-2.

Reggina are far more direct when playing out from the back whereas Inter look to play on the deck and build through the thirds. The Serie B side set up to play short, enticing the opposition to press, before eventually going long.

There are very few similarities between how Simone and Filippo Inzaghi’s teams play but it’s still quite cool to see Pippo taking some tactical tips from his younger brother. As the Irish saying goes, he didn’t lick it off the stones and was clearly influenced by his sibling.

The Stills

One man who has made countless headlines over the past few months is Will Still who took charge of Stade de Reims in Ligue 1 after a sticky patch of form for the French team. At just 30, Will is the youngest manager in any top-five league right now and has completely turned things around for Reims at the Stade Auguste Delaune, guiding the side to a 14-game unbeaten run in his first 14 matches in charge.

Still’s appointment was quite controversial given that the club were charged €25,000 per game that he managed since the young coach had no UEFA Pro License. Thankfully, the fining has stopped as Still is undergoing his license as things stand but it was a gutsy decision from Reims to put such financial faith in an inexperienced manager.

Nevertheless, Will is not the only young Still currently managing in the top division of a European league. His brother, Edward, oversees Belgian Pro League team KAS Eupen, with his even younger brother Nicolas acting as the assistant manager. What a family!

Edward is 32, older than both Will and Nicolas (26) which is comical considering he’s still one of the youngest head coaches in European football.

But while the brotherly trio all seem to be part of a close-knit family from the outside looking in, are there any philosophical similarities with how they see the game?

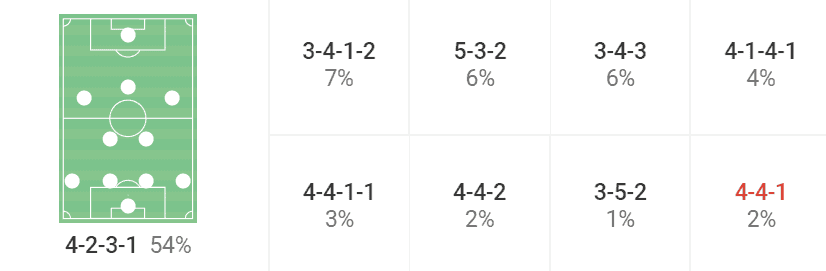

Since Will’s appointment at Reims, he has preferred to utilise a 4-2-3-1 formation, rarely switching to any other structures apart from the odd 4-1-4-1. The 30-year-old has been quite consistent with his formation choice so far.

The 4-2-3-1 has seen more usage than any other shape this season at Reims, primarily because of the manager’s insistence on deploying the conventional structure. There are other formations that have been used, including several back three shapes, but this predates Will Still and are a throwback to Óscar García’s time in charge when the current Reims boss was operating as number two.

Edward, on the other hand, has primarily opted to use a 4-3-3 formation. This is potentially a result of Eupen playing a little more transitional and deeper down the pitch, which we’ll get onto in a bit.

However, Eupen have been more willing to switch formation under their respective Still. Edward has deployed several different structures, including several variations of a back three. Even the 4-2-3-1 has seen some action at 11%.

But formations don’t really matter a whole lot. Formations are interchangeable and disposable. Pep Guardiola has proven that this season more than any other coach, using a 3-2-2-3 in possession and an aggressive 4-4-2 out of possession instead of the 4-3-3 we had become so accustomed to.

What’s more important are the principles integrated by each manager to implement their own ideas about how teams should play the game. So, let’s see if there are any similarities.

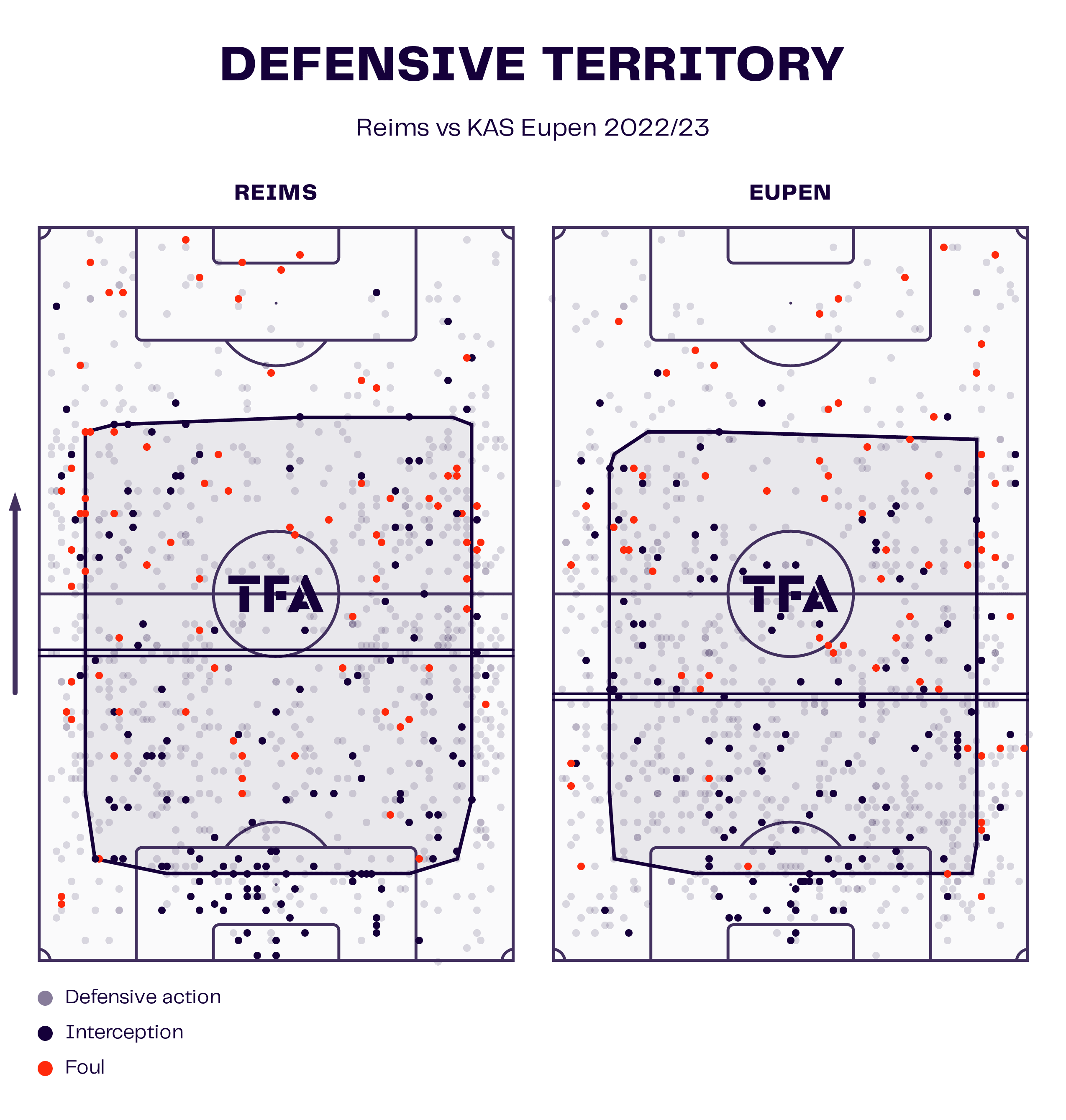

Out of possession, both Reims and Eupen like to defend in a mid-block but the former’s block is a mid-to-high block whereas the latter’s is a mid-to-low block. We can see this from the average defensive line height of each team this season.

Eupen defend much lower down the pitch in a mid-to-low block, staying as compact as possible between the lines in whatever shape they use on the day.

Meanwhile, Reims defend in a mid-to-high block, trying to force the opposition to make backward passes so they can step up and press in the final third, potentially winning the ball in a dangerous position.

There are some similarities in how each team looks to win the ball. Both Will and Edward want to force play wide to then go man-for-man on the flanks. Each team does it differently, but the end goal is the same.

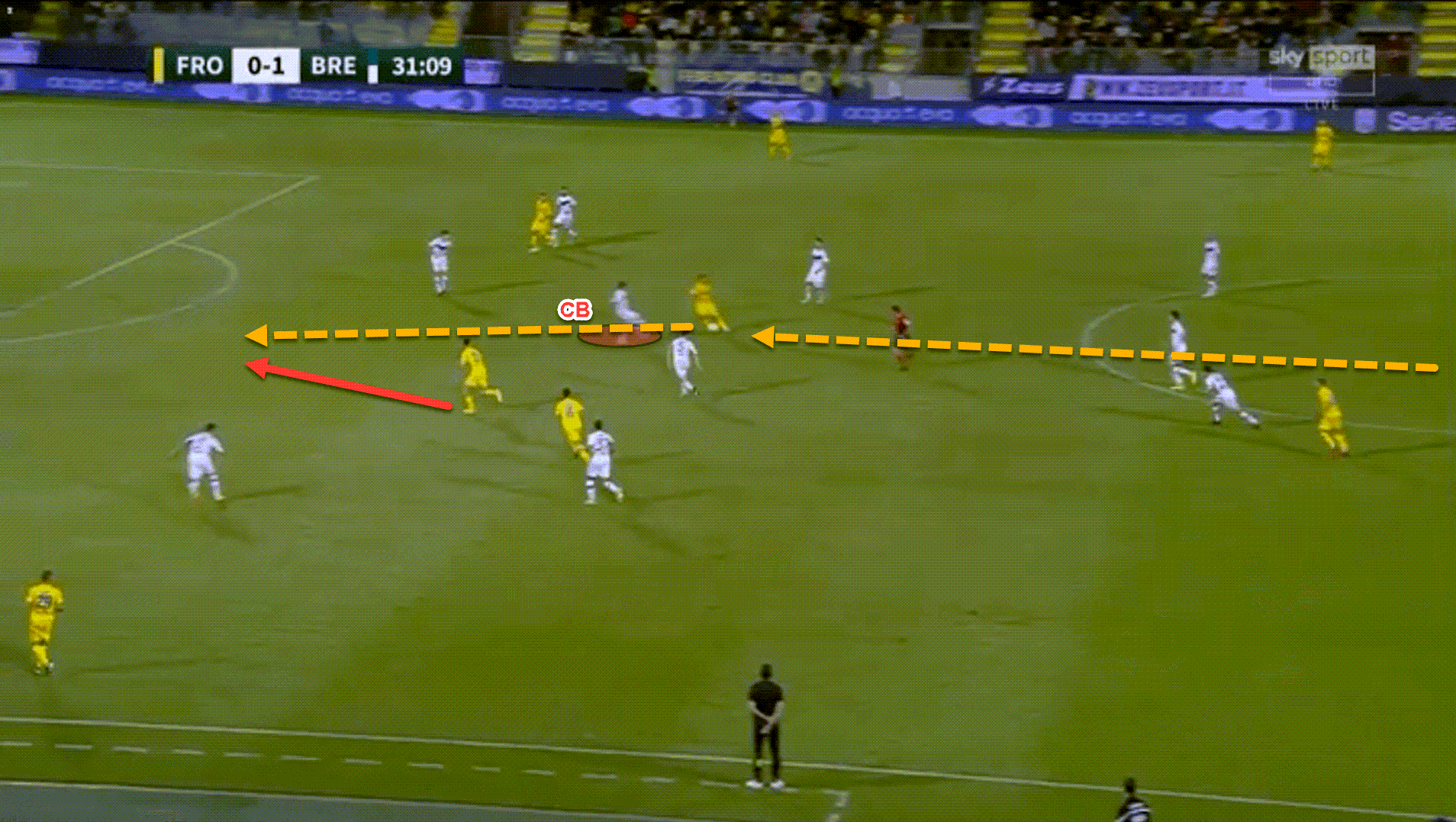

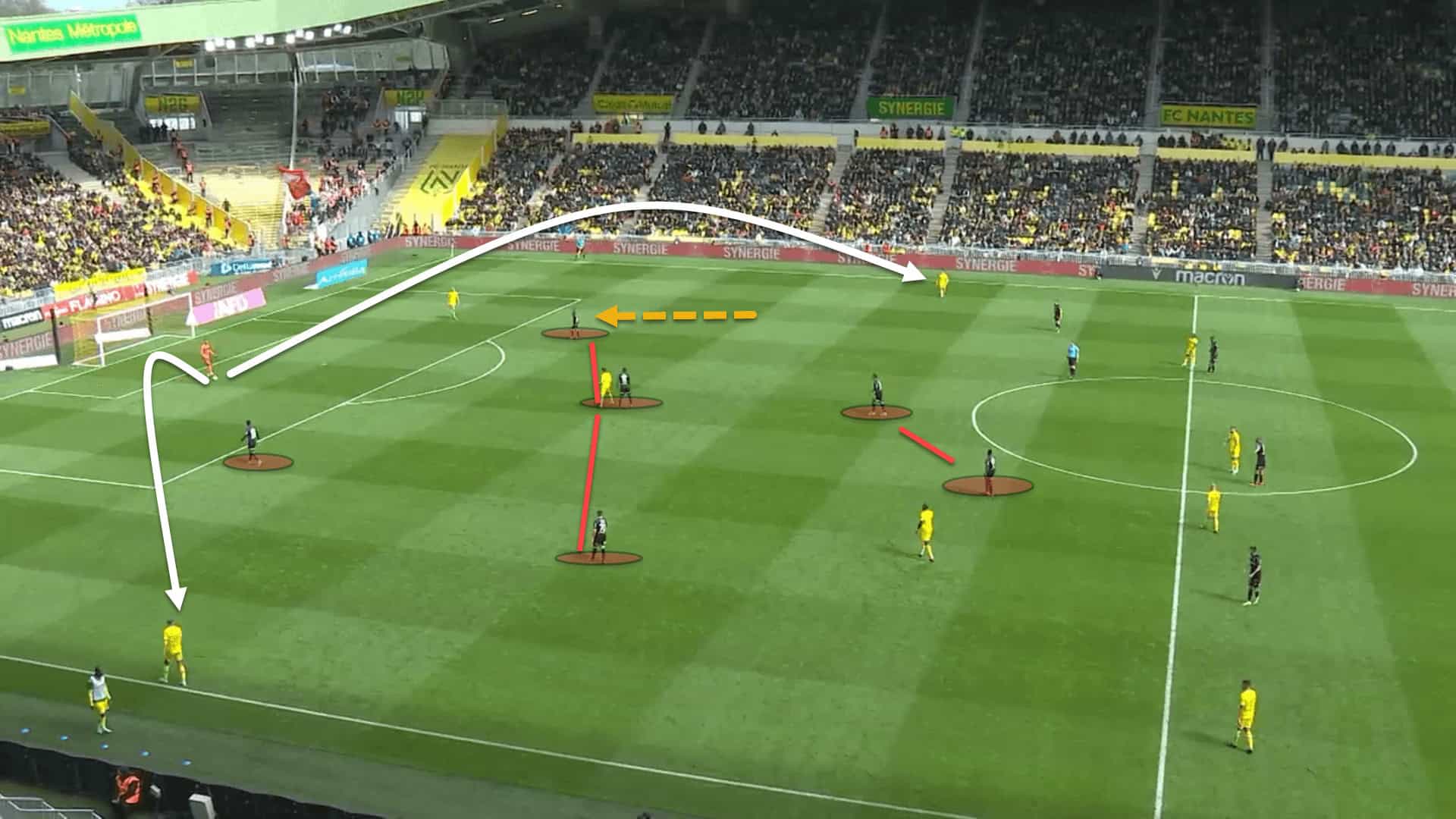

Will Still normally instructs one of his wingers to tuck inside alongside the centre-forward to press one of the opposition’s centre-backs while the fullback on that side steps up to stay close to their opposite number.

When this happens, the shape resembles that of a 4-4-2 diamond but is indeed just a lopsided 4-2-3-1.

Nevertheless, Reims want to entice the attacking team to hit the ball out to the fullbacks or else go long to the forward line.

Once the ball is played out to the wide areas, Reims lock on and go man-for-man to try and force a turnover of possession. The initial approach is zonal but once the ball moves wider, it becomes a man-oriented system.

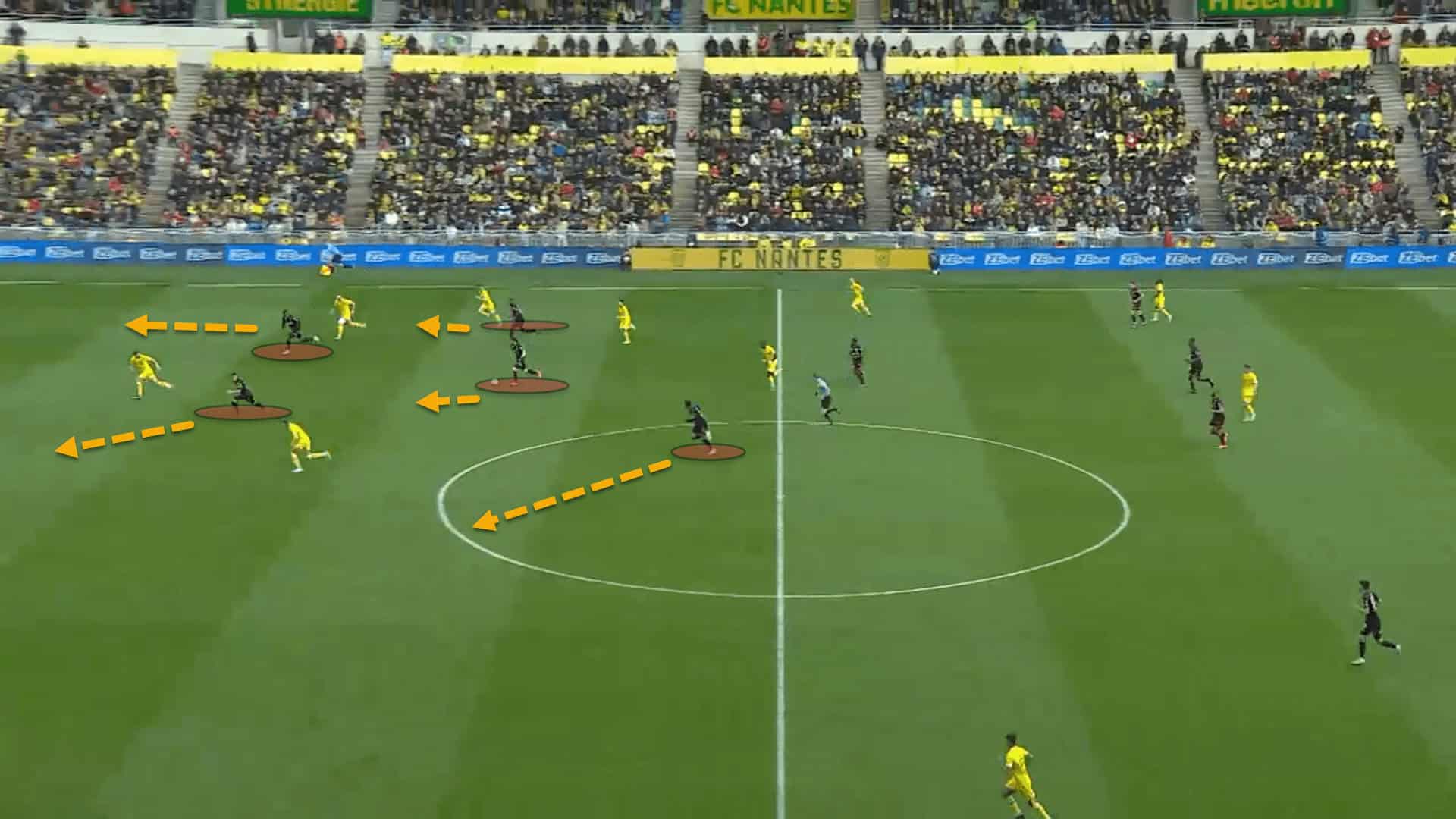

In the previous screenshot, the centre-forward, left-winger, left-back, number ‘10’ and nearest pivot player all push across to the left flank and go man-for-man against Nantes as the hosts attempt to progress the ball into Reims’ half.

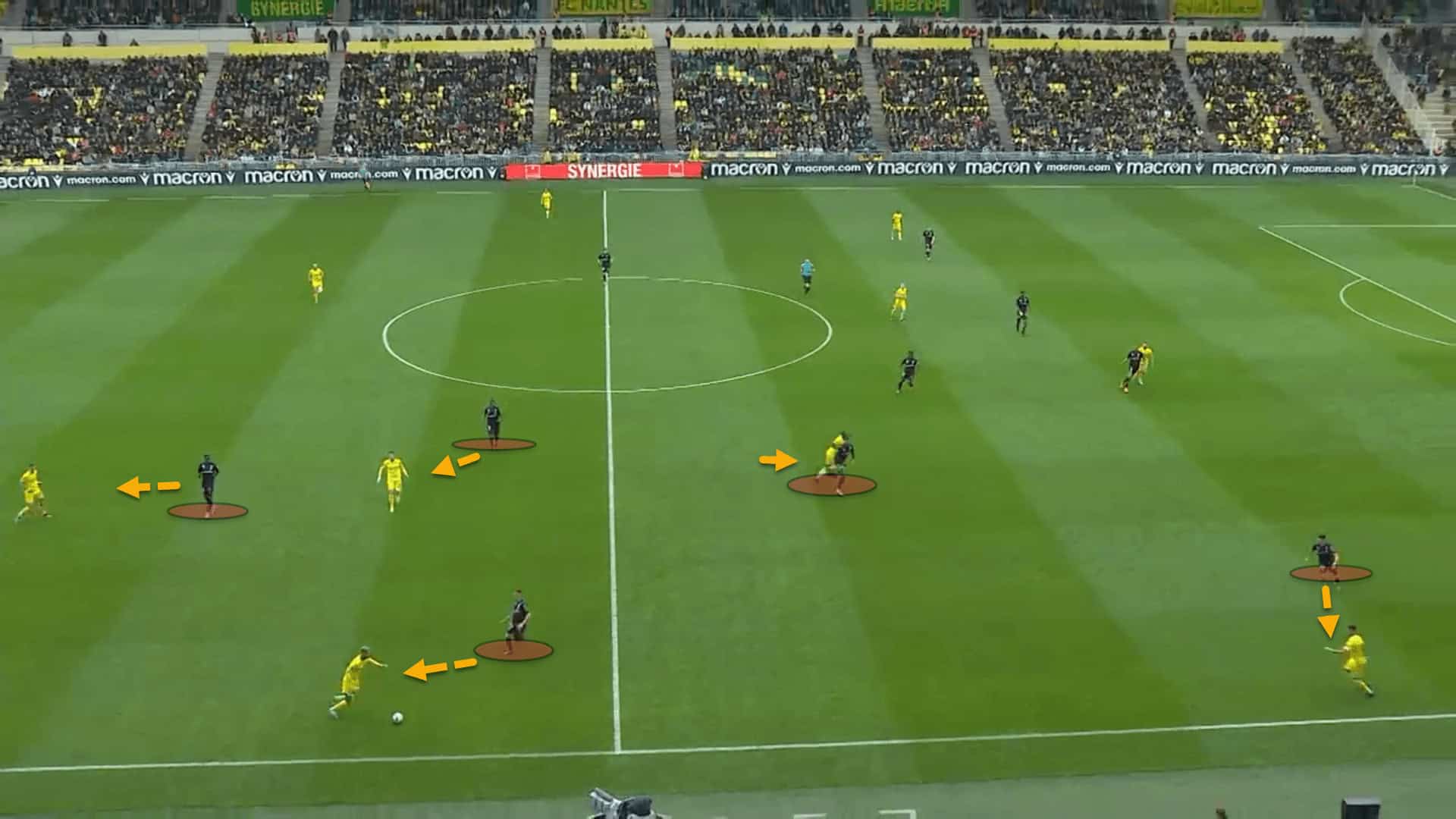

Edward still implements a very similar defensive system, although it’s a little different because of how low down the pitch Eupen defend. Nonetheless, the mechanisms are the same.

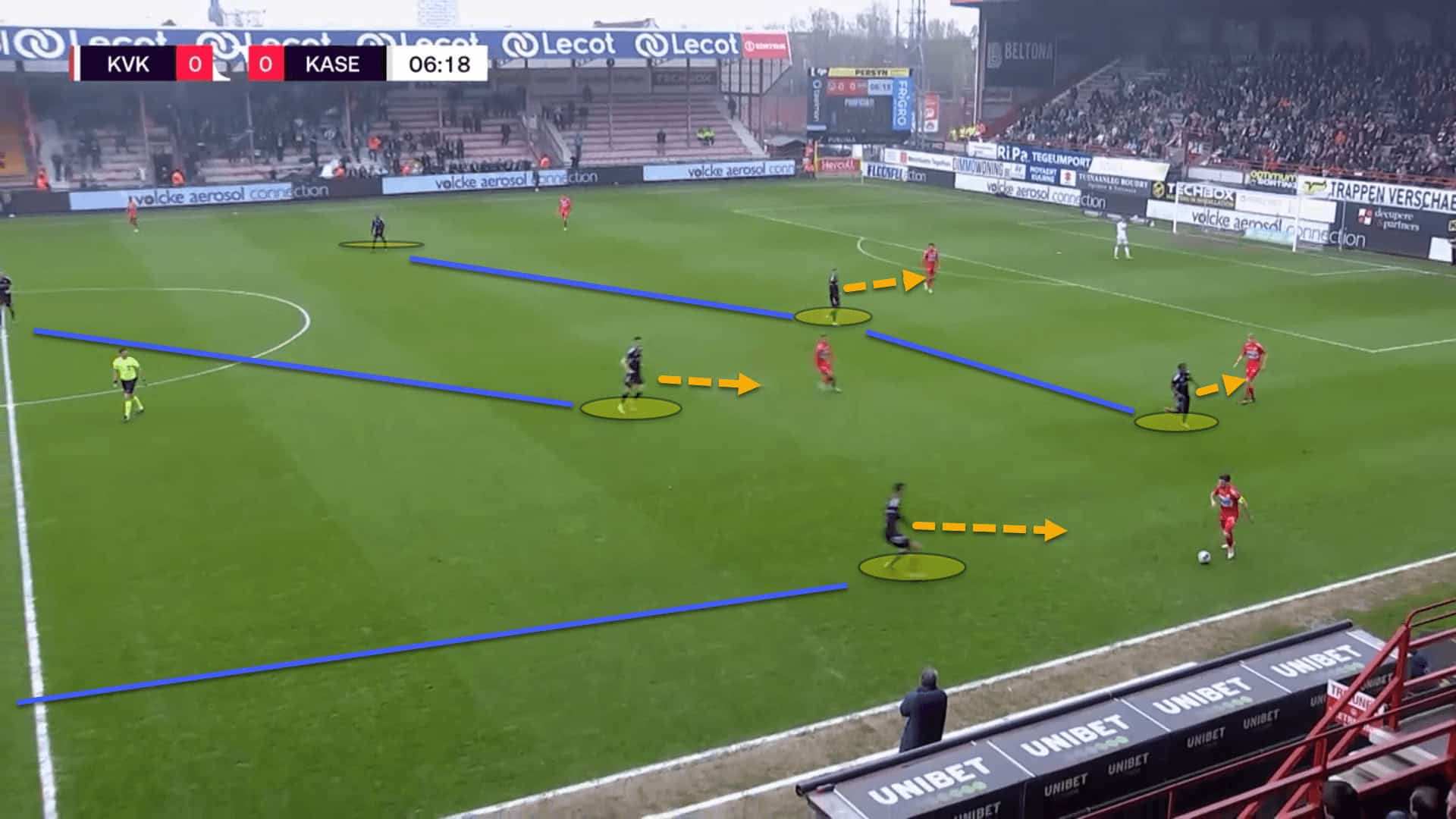

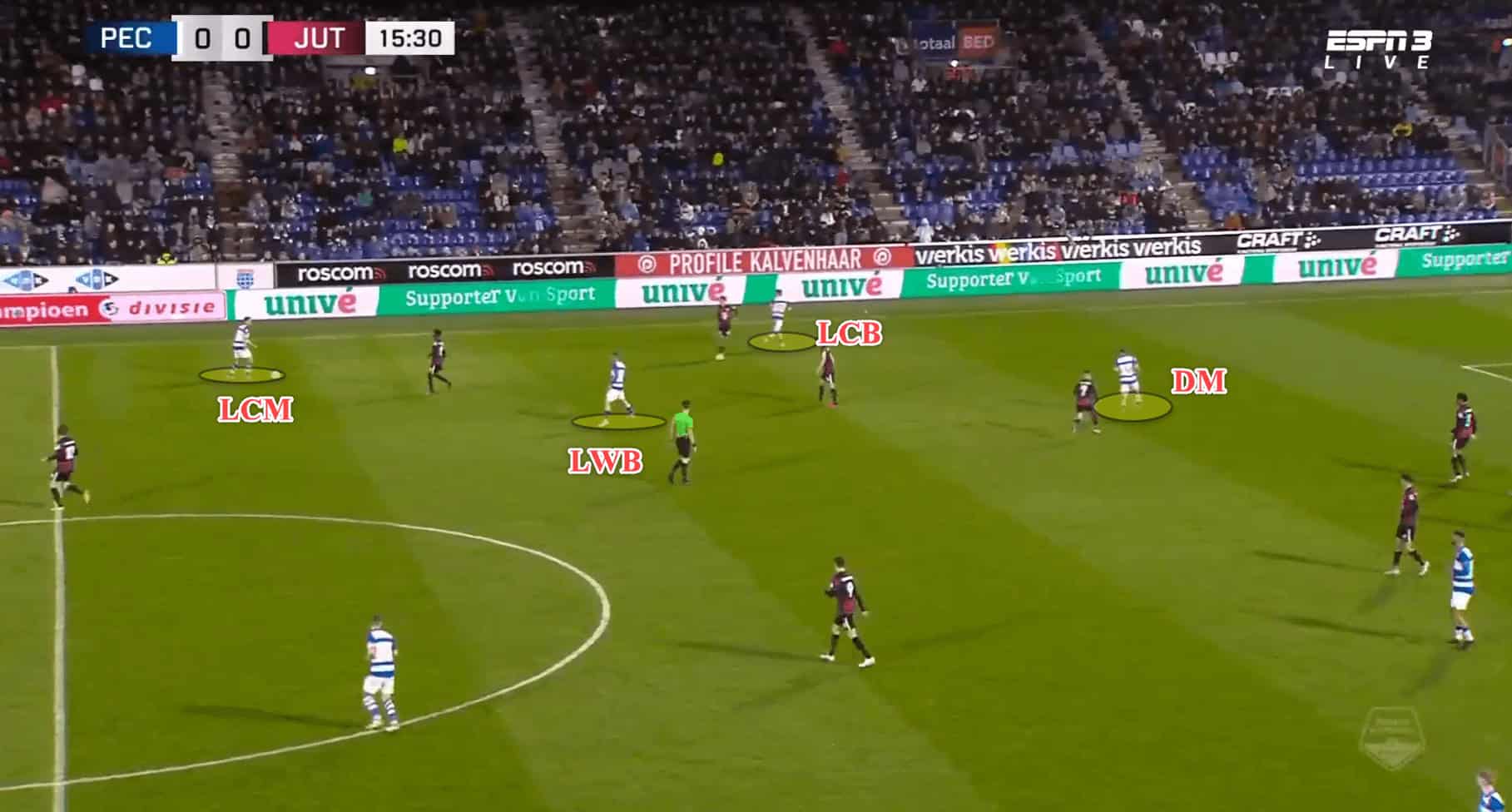

Here is an example of Eupen pressing higher up the pitch in a 4-3-3 to try and match the scenario that we analysed with Reims. The front three are pressing man-oriented versus Kortrijk’s back three, leaving the wingbacks free to receive.

Once one of the wingbacks eventually did get on the ball, they were met with Eupen’s nearest fullback who would step up to support the press from deep. Meanwhile, Eupen’s central midfielders shifted across and all defended man-for-man, locking on against their opposite numbers in the wide areas.

In this sense, both Will and Edward share a very similar philosophy about how they want their teams to press and regain possession, although the height of their blocks is extremely different.

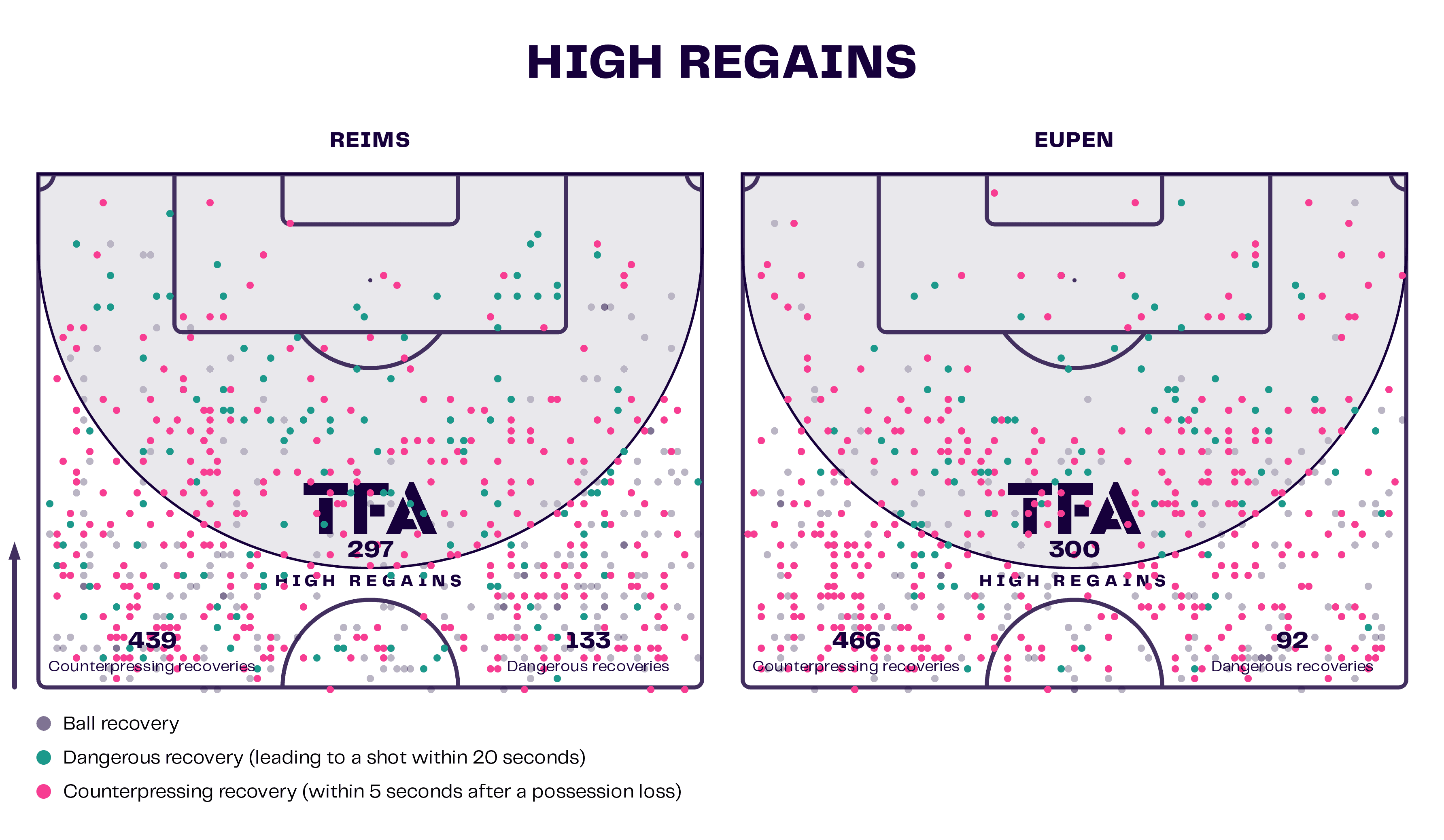

From this data viz, we can see that most of the two teams’ high regains and ball recoveries in the opposition’s half this season have been in the wide areas of the pitch.

The other big similarity between the Stills is their emphasis on being explosive in transition. There really were no big similarities between their styles in possession. Eupen are more transition-based anyway and prefer to soak up pressure before hitting teams on the break, whereas Reims are really structured in possession while also being dangerous in transition.

Pace, power and purpose are important to both men when their teams turnover possession and are breaking forward. Both commit a significant number of bodies forward, normally leaving five back and pushing five up to create a perfect balance.

Reims’ example led to a second goal versus Nantes while Eupen came very close to taking the lead from their counterattack. The speed with which the two sides break forward is astronomical and each manager has clearly spent many afternoons on the training pitch practising transitional exercises. They are both very similar in this regard.

It’s fair to say that, while there are still quite a lot of differences in terms of their teams’ styles on the pitch, they are far more similar than the Inzaghi brothers and share some more tactical DNA in the dugout than merely a build-up pattern.

However, neither example comes close to the Schreuders…

The Schreuders

The surname ‘Schreuder’ has negative connotations now in Dutch football since Alfred was disgraced from Ajax, taking the champions to sixth place at the halfway mark of the season.

However, one Schreuder that is flying high right now is Alfred’s older brother Dick who is currently guiding PEC Zwolle back to the Eredivisie, sitting atop the Eerste Divisie, playing some scintillating stuff to boot.

Unfortunately, Dick Schreuder was the man who took Zwolle down from the top-flight last season but has been given the opportunity to take the club back to the promised land — something he certainly didn’t take lightly.

The duo’s football philosophy is extremely similar. One could put this down to the inherited Dutch coaching blueprint instilled upon many young minds in the Netherlands, but both take Total Football to the very extreme compared to more positional coaches such as Ronald Koeman, Louis van Gaal and even Erik ten Hag. It can’t be a coincidence.

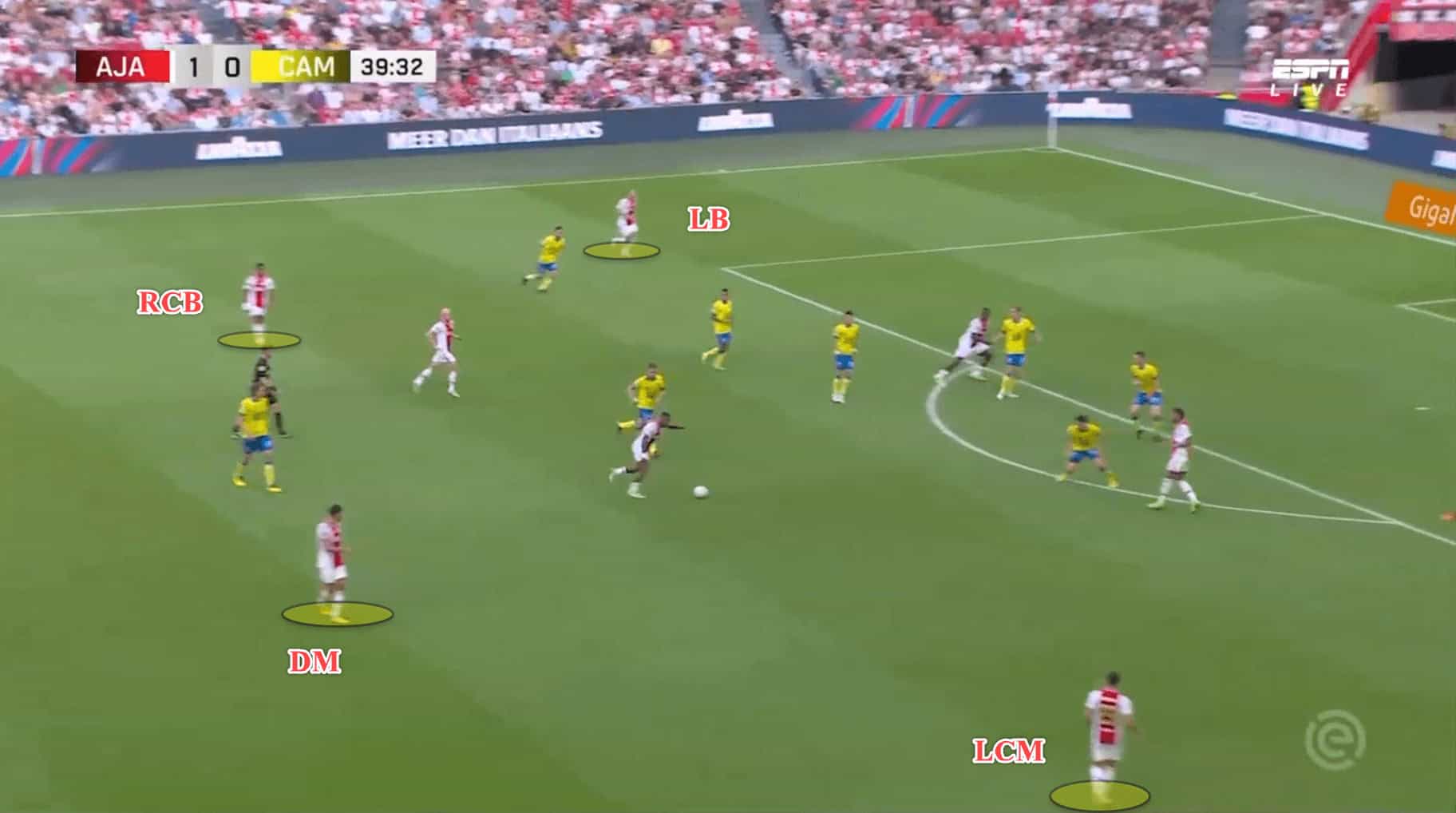

The biggest similarity between their tactical identities is the idea that, in possession, formations really don’t matter. The idea is to create a structure filled with rotations and positional interchanges while playing fluid, attacking football to concoct as many chances as possible.

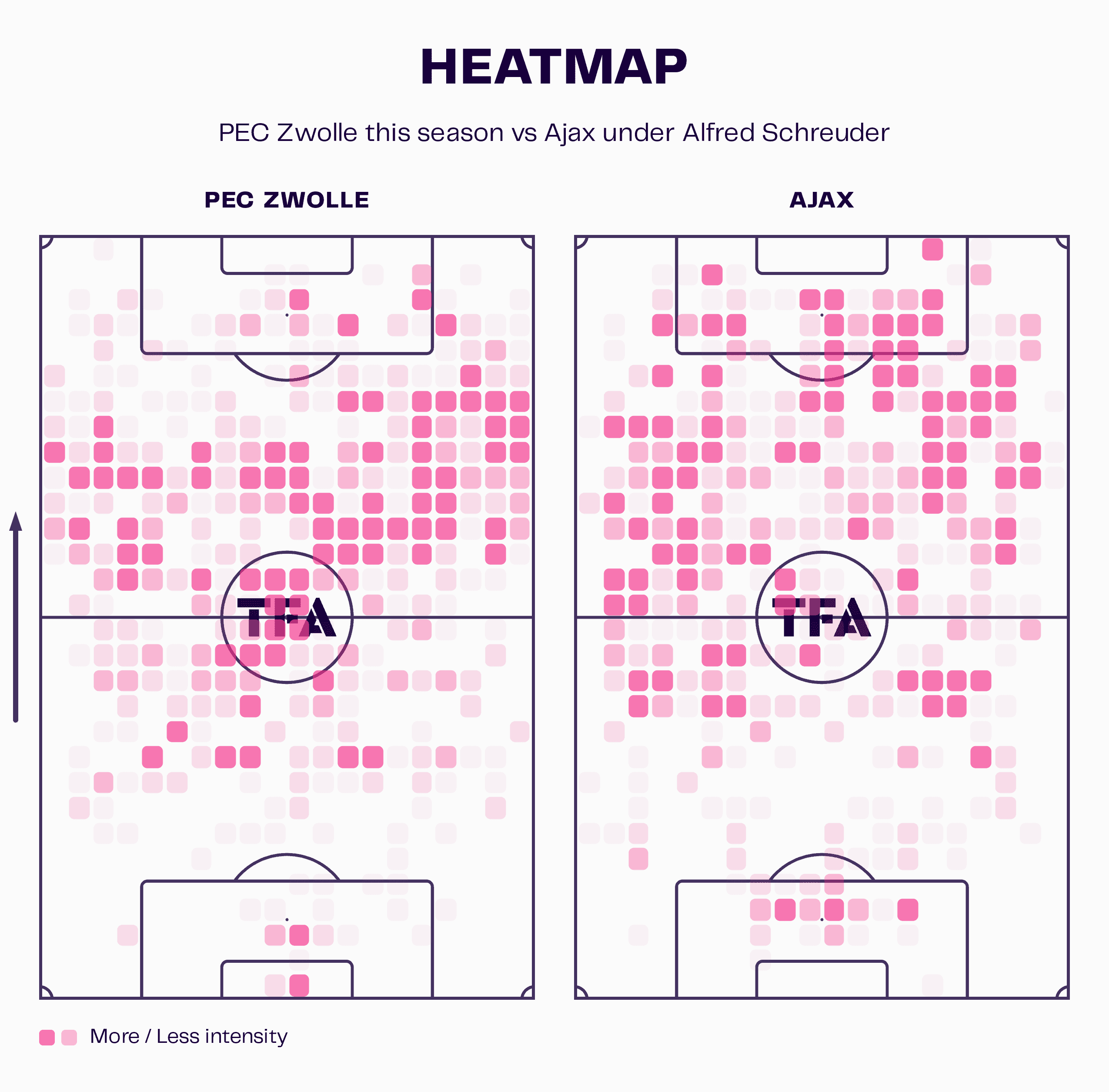

When looking at the heatmap from PEC Zwolle under Dick and Ajax under Alfred, we can see that both coaches want to have the ball in the same areas of the pitch — the halfspaces and wide areas, where the best rotations can occur without causing too much disruption to the balance of the side.

But rotations also occur lower down the pitch with the centre-backs who are given freedom to stand in front or behind the opposition’s first line of pressure.

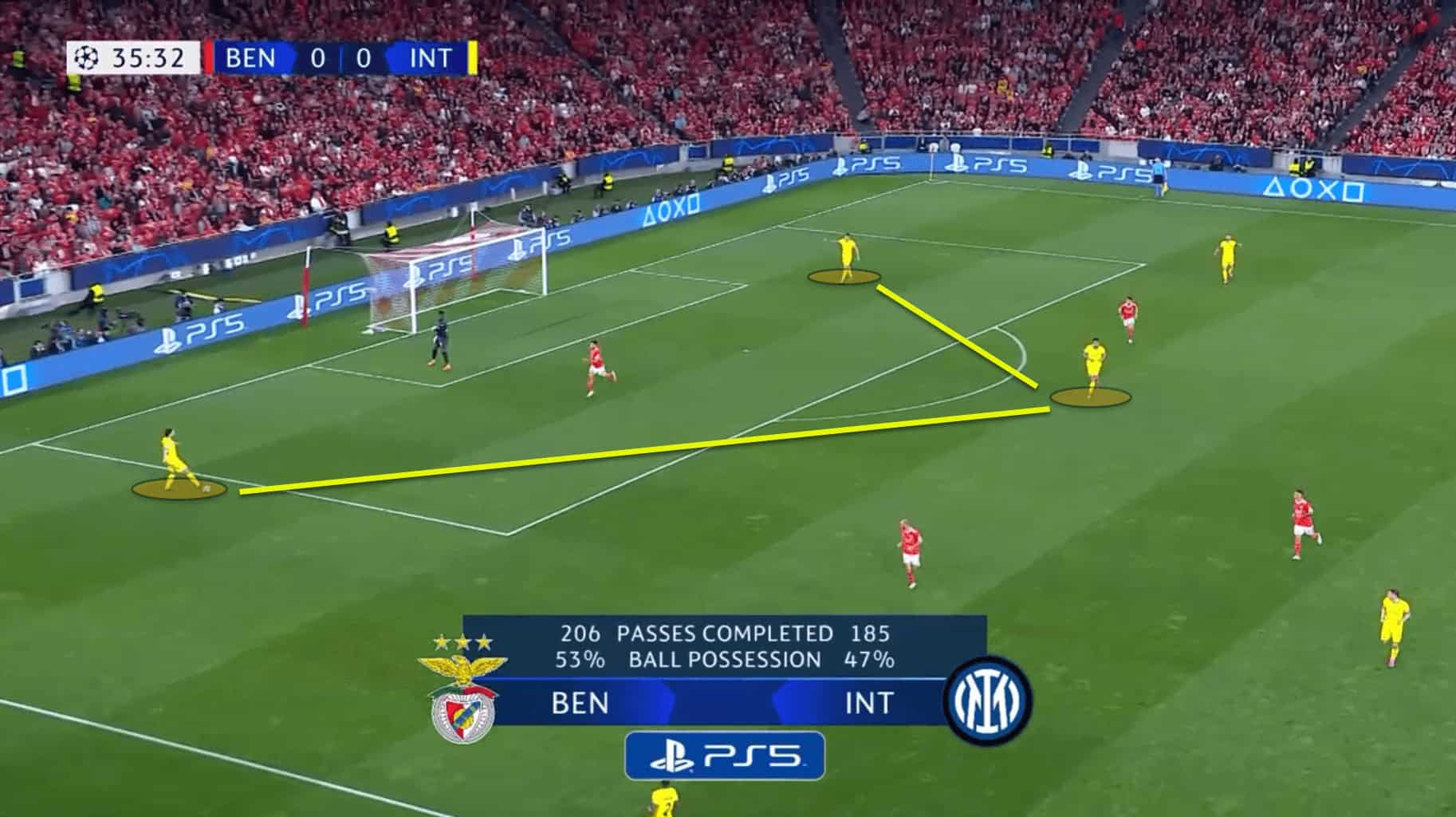

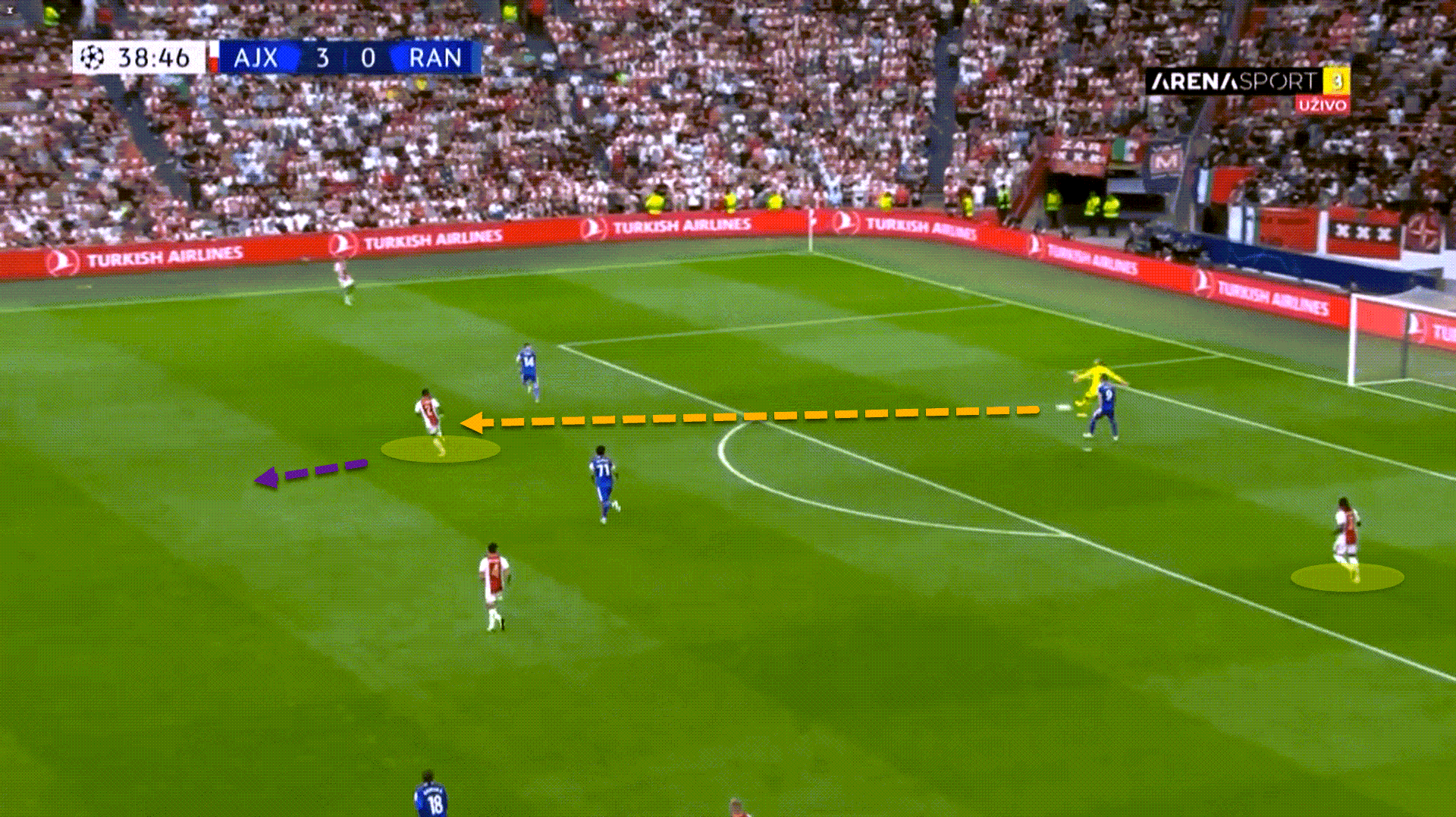

Alfred Schreuder is a little more lenient with the positioning of the centre-backs than his brother though. Look at the previous screenshot as a perfect example. Despite starting to build up with a back four and one pivot player, right centre-back Jurrien Timber pushed up behind the second line to receive to feet from the goalkeeper, which was achieved successfully.

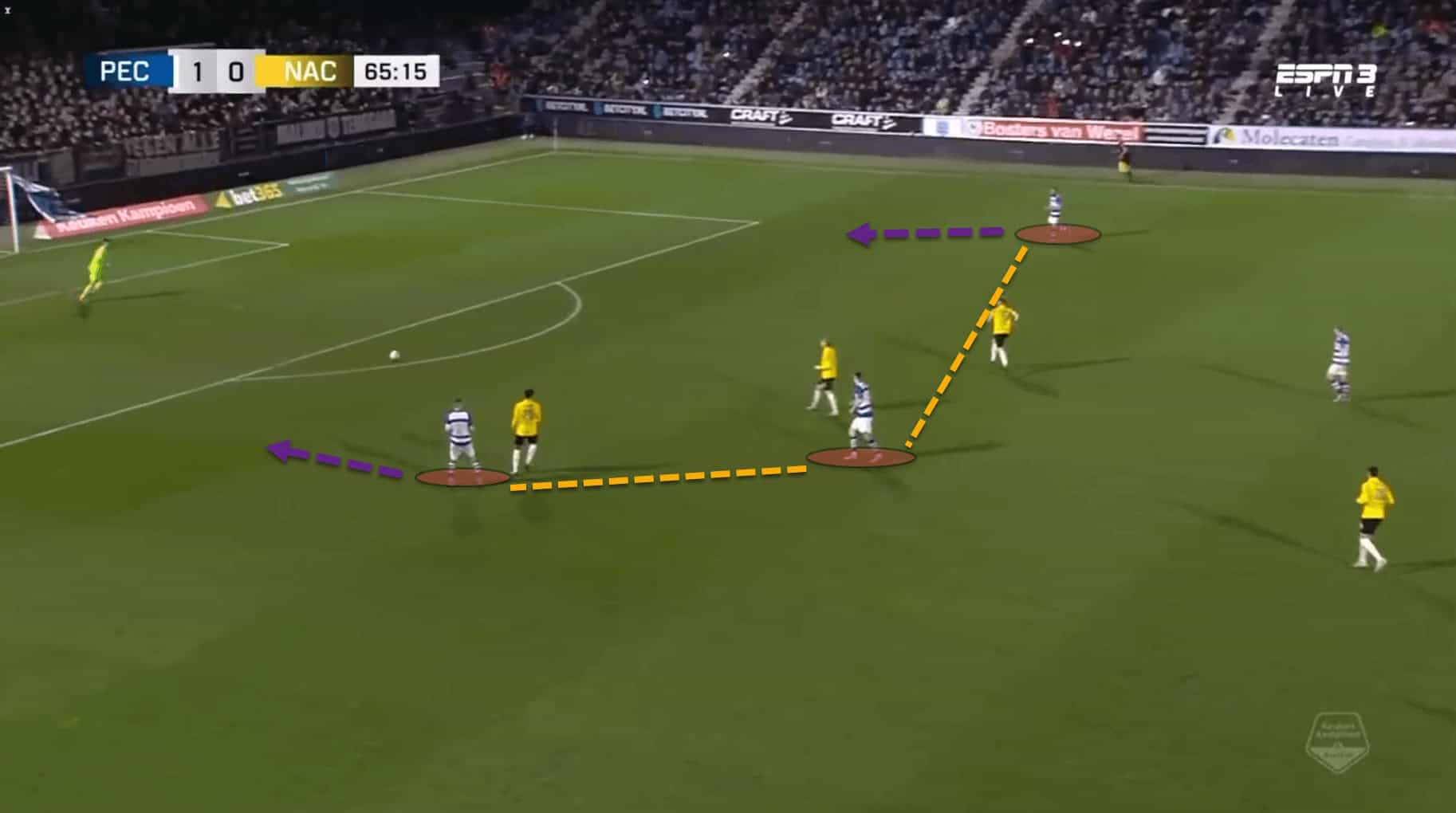

While Dick Schreuder’s PEC Zwolle are not as risky as Alfred’s Ajax, there is still a lot of fluidity with the positioning of the backline during the build-up phase.

Unlike his brother’s adamancy on using the 4-3-3 at the Johan Cruijff Arena, Dick Schreuder has preferred to deploy three centre-backs. However, during the first phase, the central centre-back pushes up behind the second line while the wide centre-backs drop a bit deeper to get the ball from the goalkeeper.

The structure is slightly different in this respect, but the principle behind what each manager is trying to achieve is identical.

Further up the pitch, things get even crazier for the Schreuder brothers. Both have completely succumbed to the blueprint of Total Football that they take on almost an extremist form.

It’s not a case of a central midfielder pushing out to the fullback slot while the fullback moves inside, interchanging positions but keeping the same structure. The Schreuders create an environment of chaos where space is worshipped as a God and all the players are disciples.

Formations don’t exist and every player is given license to roam around, providing there is still some rest defence structure in case of a turnover of possession.

In the previous example, centre-back Timber was positioned in space out on the left flank while left central midfielder Steven Berghuis was holding the width in a typical right-back spot. Meanwhile, the pivot player formed a two-man rest defence alongside the other centre-back Calvin Bassey. It’s carnage but makes for fun viewing.

Dick Schreuder is an advocate for the exact same style as his younger brother.

Here, PEC Zwolle are attacking down the left and have created an overload with four players but the positioning is incredible. The left central midfielder is the deepest player of the four. The left wingback is positioned in the halfspace while the left centre-back is running in behind alongside the number ‘6’ who is doing the same but in a more central role. Again, carnage.

We’re not here to criticise this style or set-up or to even make critical observations about each head coach but to merely note that their styles are incredibly similar, centred around having possession of the ball and having freedom of movement all over the park to disorientate the opposition’s defensive shape.

It is very clear that out of the three sets of brothers analysed in this article, Dick and Alfred Schreuder are the most similar in terms of style and the imposition of this tactical philosophy.

Conclusion

This article was intended to just be a little bit of fun. There is no conclusive data that could tell us whether head coaches who are siblings share a similar tactical identity because there are a million other variables which dictate this such as learnings from their playing careers, personnel and the identity of the club, just to name a few.

However, they all do share some similarities, whether it be in or out of possession, but some more so than others, as this analysis has shown.

Comments