Rondo’s are now a generally accepted training practice at all levels and locations of the game. Believed to have been invented by Barcelona youth coach Laureano Ruiz, advanced by Johan Cruyff and lauded by Pep Guardiola, its roots are firmly planted in the Catalan capital. Now, they are commonplace throughout the football world, and it is difficult to find a training session that does not include some variation of the exercise.

Although the secret is in their simplicity, rondo’s have evolved greatly over the previous few years. They are now much more than a lighthearted way to begin a practice. This tactical analysis shows there are numerous ways in which they can be utilised. This tactical theory will explain the uses and limitations of rondos and offer three examples of rondos that can be used to work on various tactical situations.

Definition of a rondo

Rondos have certain traits that differentiate them from what some would call “possession games”. Typically, in a rondo, the in-possession team has an attacking overload, and their players are positioned in a somewhat fixed position. The area is usually greatly condensed, allowing for just one or two touches while being put under immediate pressure from a limited number of defenders.

The defending or pressing players usually have the opportunity to join or become the in-possession team should they intercept the ball. This can be used by coaches as subliminal motivation for possession-based teams – you lose the ball, you run. There are many variations of rondos, with countless set-ups and conditions or rules within set-ups, but these are the common themes they share.

Uses of Rondos

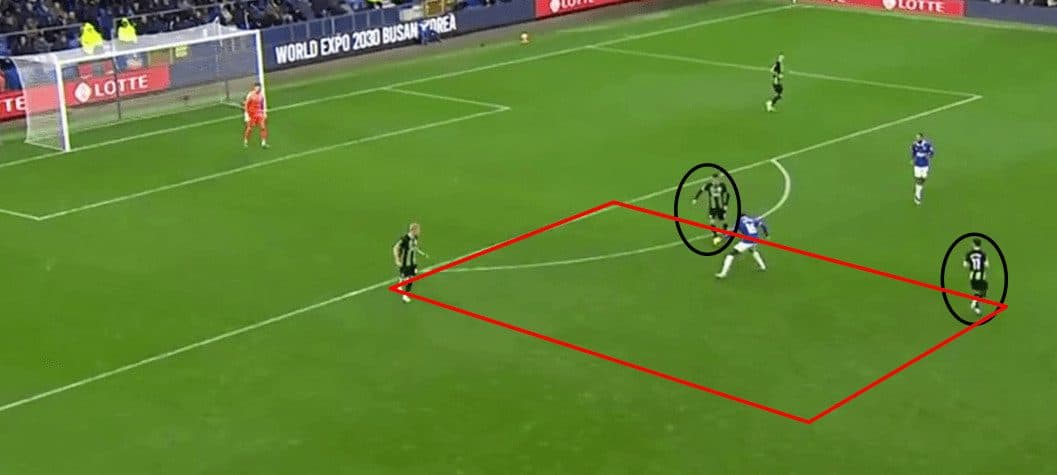

Rondo-like situations can occur all over the pitch, as the image above from Brighton against Everton shows, when three or more players are positioned in a small area. These players, angled towards each other, create a situation where another opens if the defending player cuts off one passing option. This positioning allows the players to bounce the ball off one another. These scenarios often have the effect of attracting defending players towards the ball. Teams can then escape to the space that has been created elsewhere.

The condensed areas rondos are usually conducted in and are designed to give players the skill set to be comfortable in these situations. Players must be on their toes, always expecting the ball, and be quick in their decision-making. With the ball coming from all directions, and not always cleanly, all parts of the foot will be used to keep from losing the ball. Often, coaches introduce a limit on the number of touches that can be used. This increases the intensity yet again and adds pressure to have a perfect first touch.

The defending players in the middle of the rondo are also learning, and not just by means of punishment, for losing the ball. Players working in twos or more against a greater number of players have to be deliberate in how they press. If playing against capable teammates, randomly chasing the ball means they will never get it back. Instead, one player can narrow an angle to make the next pass predictable for his teammate to steal the ball.

Rondo’s limitations

One criticism of the typical rondo set-up is that it does not require scanning (looking around the pitch) as players are in fixed positions. The area is also small, with the ball moving too fast to accommodate the checking of one’s shoulder.

A short clip of Sergio Busquets playing in a rondo with the Spanish national team surfaced a few years ago. Busquets, who was acting as a playmaker in the middle of a rondo box, was praised by viewers for his awareness of his surroundings. A quick analysis of the video shows that not once in the 60-second-long video does Busquets “scan” or check over his shoulder. He does not have to. He knows where his teammates are, but that is because they do not move. They are in fixed positions.

Undoubtedly, Busquets can, and does, scan when dominating in midfield. However, he likely did not acquire this habit from rondos of this style. Instead, it is his close control, the weight of pass, quickness of thought and positioning relative to the nearest defender that have been developed – all vital skills to have.

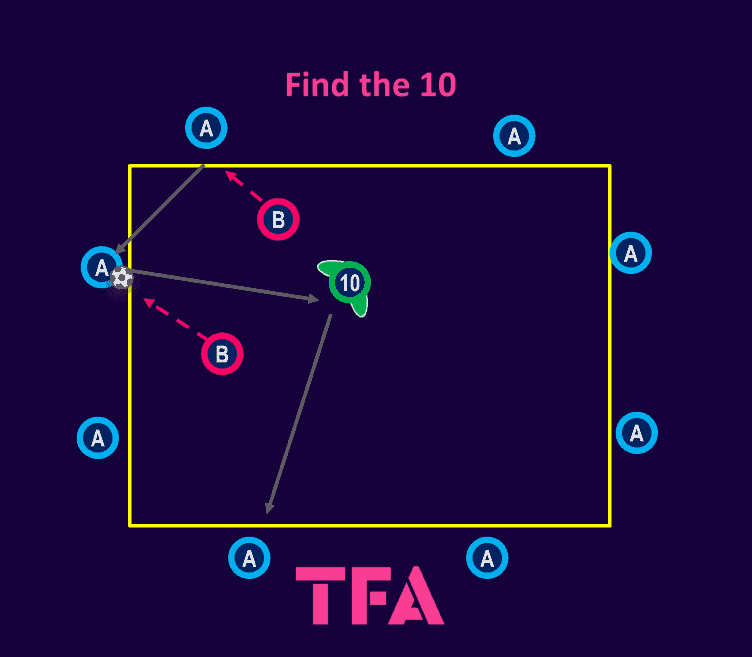

Find the 10

Number of players: 7 to 12

Area size: 10-15 X 10-15 yards

The set-up of this exercise is closely related to what most would consider a “classic rondo”, with in-possession players on the sides of a box and two or three defenders in the middle. For this rondo, an additional in-possession player is added to the middle. This player represents a “10” or even a defensive midfielder who is attempting to find pockets of space between defending players.

The aim of the rondo is for the players on the edge of the box to play passes into the middle player. The middle player must then play a pass into a player on a different side of the box, either with a first or second touch. The working player should be encouraged to pick up positions outside the defender’s line of vision and be able to “see” the ball (i.e. not hiding behind a defender). A body shape that allows the player to play out to another side should also be taught.

If the coach wants to add a competitive element, passes into the working player that get switched to another side can be counted. These can count towards the working players’ total or tallied against the defending players. The working player and defenders can stay in the middle for a set period of time. Alternatively, a player who loses the ball can switch with the player who intercepted it.

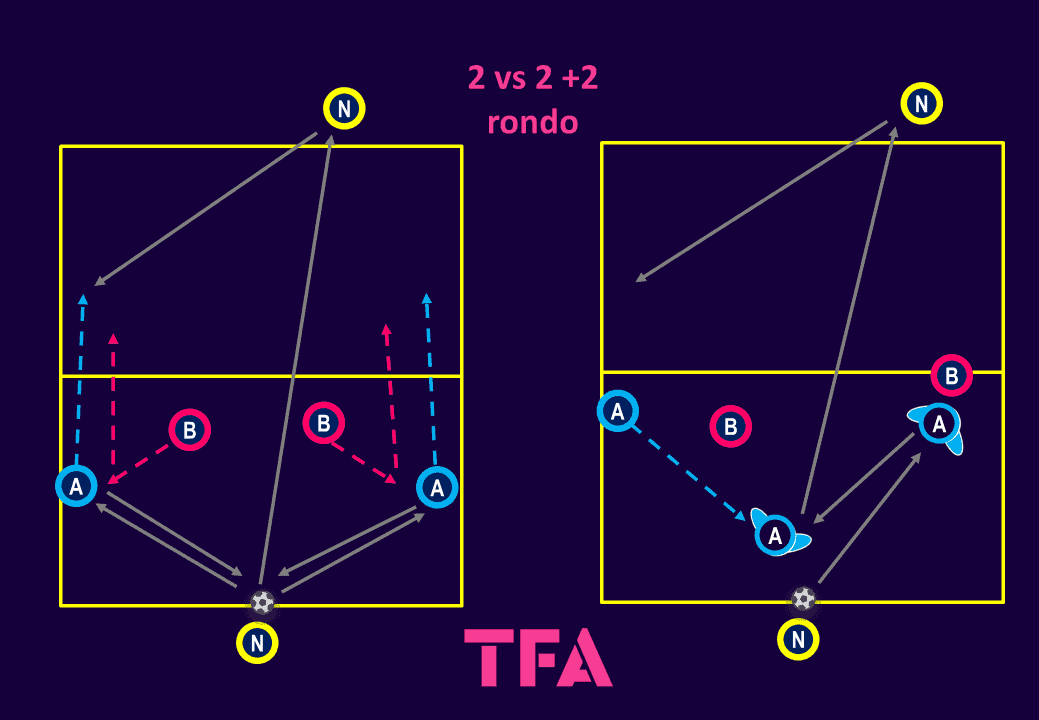

2 Vs 2 + 2

Number of players: 6

Area size: 8-10 X 16-20 yards

This rondo is more directional than the previous example, with players given a clear target to work the ball to. Two players, shown as pink, press in one half of the area as one neutral (yellow) and two in-possession (blue) players keep the ball. The three players must keep the ball for several passes (3-5 ) before working an opening that allows them to switch the ball. The four working players then transition to the opposite side of the box and play off the target players’ first or second touch. Should the pinks win the ball or poke it out of play twice, they become the in-possession team.

The three teams stay in their roles for a set time (1:30-3 minutes) before switching out. To make it more transitionary, an alternative condition for this game is to have whichever team, including the yellows, that gives the ball away become the defending team. In this example, should the pinks intercept a pass from the yellows, they would pass to the blues and switch places with the yellows.

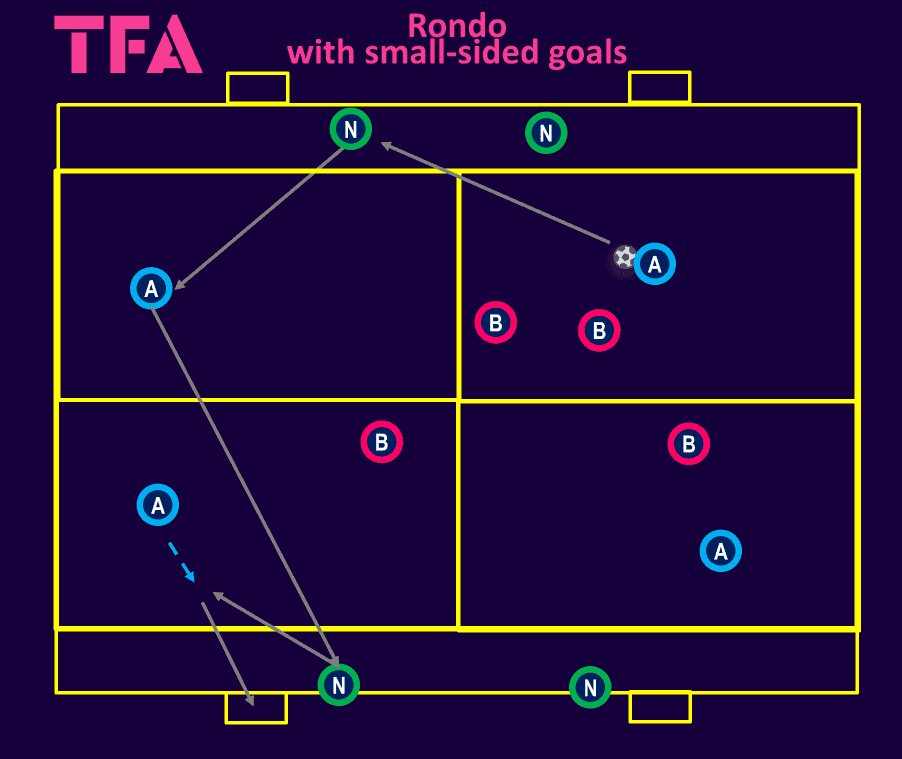

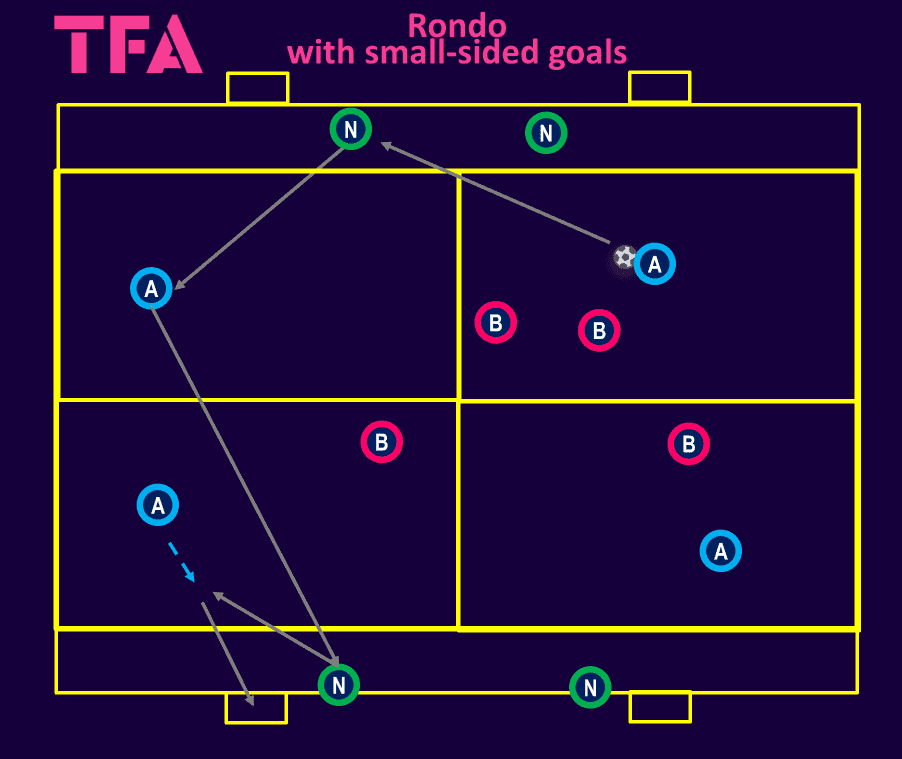

Rondo with small-sided goals

Number of players: 10 to 15

Area size: 20 X 20 yards + 5-yard end zone

This rondo incorporates small-sided goals whilst still maintaining the principles of a rondo. The aim is for the in-possession team (blue) to pass to an end player (green), receive the ball back, and shoot into the small-sided goals to score.

The inside area is split into four boxes of 10 X 10 yards. The in-possession team must occupy each of these boxes. The defending players (pink) are free to move around the entire grid as they please. The neutral players play for both teams but must remain in their zones. When they receive the ball from the team attacking the goals closest to them, they must bounce it first into a player from that team. The first-time pass means the attacking team must make early supporting runs.

The players having to occupy each of the inner boxes works on their spacing and forces them to maximise the space available. The coach may allow the in-possession players to switch boxes to encourage more fluidity. This would authorise more than one player to enter a box as long as they are in the process of rotating.

Conclusion

Rondos have developed a lot over the last several years and, for many, are a vital part of a training session. The speed of play, manufactured by the area size and the constant close proximity of a defender, means poor technique will be highlighted immediately.

In addition to individual skill acquisition, rondos also offer a good way of introducing tactical concepts. Switching the ball out of tight areas or creating space and angles for a target player are just two examples of tactics that can be worked on.

It should be noted, however, that rondos are not a panacea for all of football’s complex scenarios. There can be a temptation to overuse rondos, but if we accept their limitations, they form a pivotal part of a coach’s training session or cycle.

Comments