As with attacking phases of play, modern coaches are constantly innovating in how they teach their players to defend. These can be both new concepts for old problems and tactics to counter the developments on the opposite side of the ball.

This tactical theory will first provide an analysis of defensive techniques and tactics that have changed in recent seasons and now go against conventional wisdom from years gone by. How Pep Guardiola has used a different tactic to defend long balls and how players, collectively and individually, defend the box with a more thought-out strategy are analysed. This tactical analysis includes some sample training exercises that coaches can use to implement these defensive coaching theories.

Defending the box

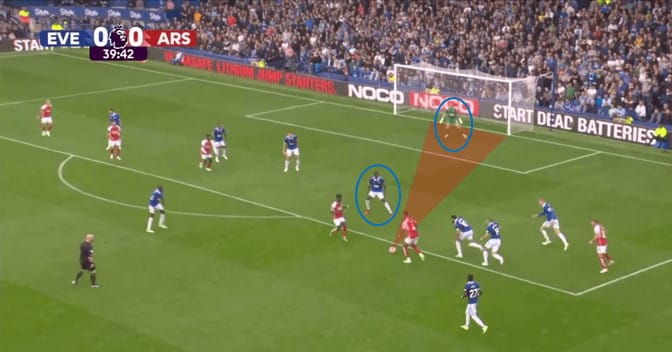

Modern players, particularly those playing in the backline, have changed their approach to defending the edge of the box in recent years. Instead of prioritising getting their body between the ball and the goal, they now move slightly off-centre.

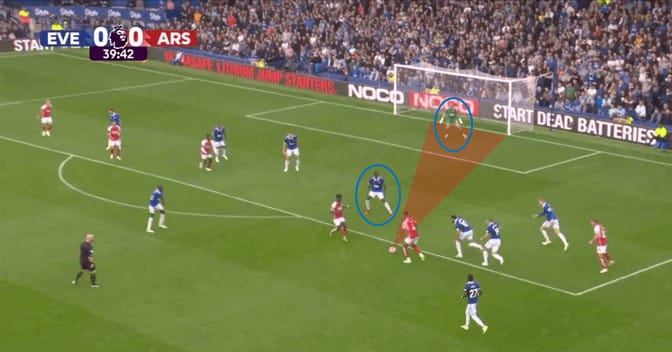

In the above example, from Everton’s recent match against Arsenal, he would have covered more of the goal if the defender had been directly in front of the ball. However, this positioning would have made things more difficult for Jordan Pickford in goal.

Pickford would have been unsighted, unable to see the ball because of his defender. This may have forced him to overcompensate to one side of the goal. It would also have allowed the attacking player to use the defender to bend the ball around.

When the ball is in a more central area, Dyche and other top-level managers have instructed their centre-backs to prioritise defending the corners of the goal. This, again, allows the goalkeeper a clear sight of the ball, less of the plan to cover, and prevents a defender from being used to curl the ball around.

In similar situations, when shots are hit from the edge or just inside the box, you may expect players to throw anything they can at the ball to obstruct its path. Think England’s John Terry “fish diving” at the 2010 World Cup. However, these actions, often dangling a leg at a shot, can lead to a deflection that takes the ball away from the goalkeeper’s dive.

Liverpool was possibly the first, or most obvious example, of a top team that deliberately stopped defenders throwing a flailing leg at a shot. Initially, this appeared quite striking, with players almost making themselves “smaller” with their arms and legs tucked in.

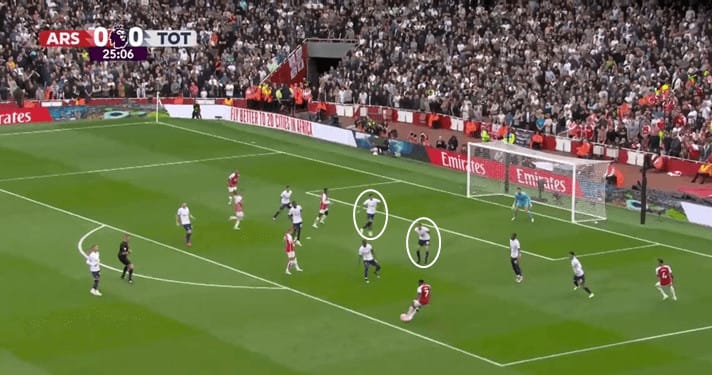

As with the first image, their players typically cover the far side of the goal, allowing the goalkeeper a clear sight of the ball. When the shot is taken, they do not put out an outstretched leg, with the risk of deflecting it past the goalkeeper. Instead, they trust their goalkeeper to deal with the shot.

In this example, from Tottenham’s recent match at Arsenal, Spurs adopt the same tactic with the first defender protecting the far half of the goal. However, with the ball going wide of the target, the second defender sticks out a leg and deflects the ball into the net. This shows the danger of players instinctively trying to get in the way of shots.

Dropping off to defend long balls

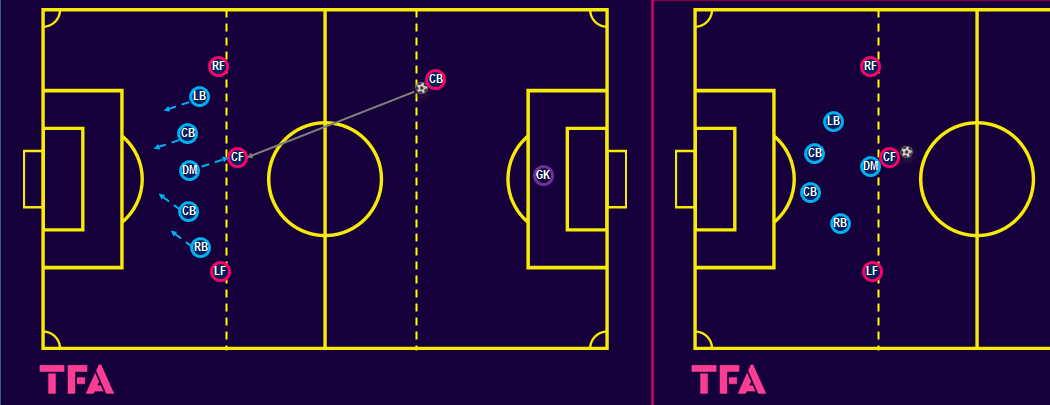

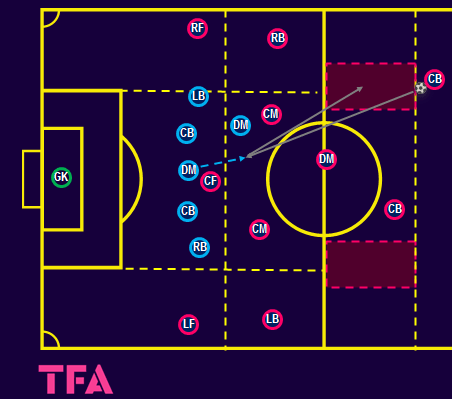

Another development at the top level is how teams react to long balls. The above tactical diagram is based on Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City, who adopted this tactic a few seasons ago. It shows how their back four and defensive midfielder are utilised to deal with teams playing direct, long balls to their target man.

Often, centre-backs feel a need to assert their dominance by competing for the ball when it is in the air. Enticing the centre-back to challenge before winning the ball and flicking it on is usually precisely what the centre-forward wants. This creates a gap in the backline for another forward to run through and onto the ball.

Guardiola’s solution was to have his defensive midfielder drop into the back line. This allows the midfielder to attack the ball whilst the backline forms a ‘C’ shape behind the player competing for the ball. In the worst-case scenario, where the first contact is lost and the ball is flicked on, the backline are well placed to receive the second ball.

Alternatively, the defensive midfielder and centre-back temporarily switch roles, with the midfielder joining the backline and the centre-back competing for the ball. Working on the assumption that at least one of the centre-backs are dominant aerially, this is usually the preferred option.

One-on-one emergency defending

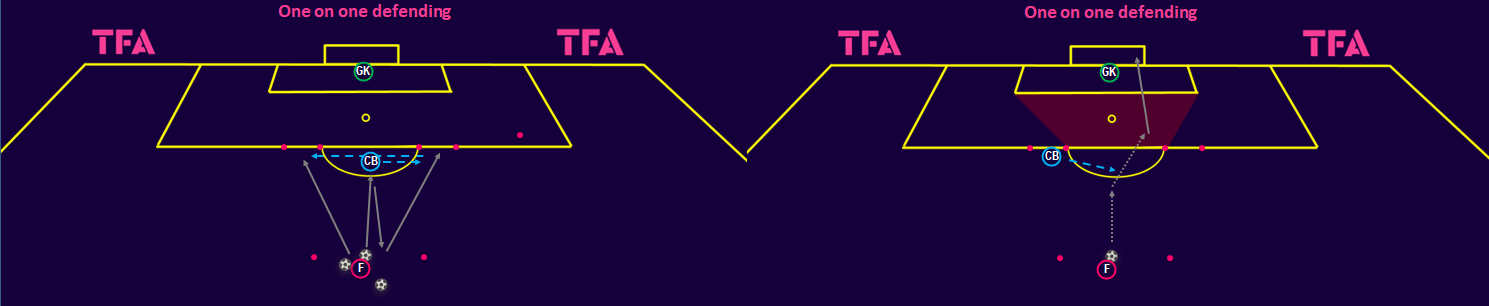

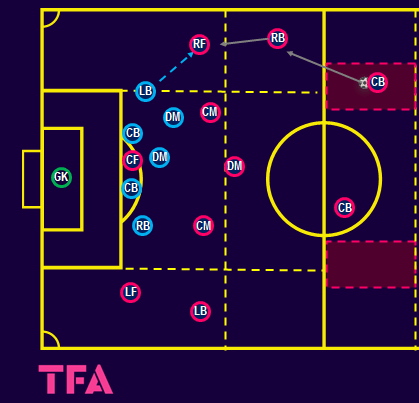

This one-on-one defending exercise begins with the attacking player (pink) passing the ball to the defender (blue) and receiving a bounce pass back. The pink player then aims a side-footed pass through one of the gates on either side of the defender. The defender must react quickly to prevent the ball from going through the gate. Ideally, when defending the gate, the ball is cleared high and wide or controlled and passed out if timed well enough.

A second ball is then immediately aimed at the gate on the opposite side, which the defending player has to react quickly to. This is designed to replicate defending through-balls at the edge of the box on the five yards on either side of the centre-back.

As shown in the image on the right, a third ball is introduced after defending the second through ball. The defending player must recover centrally as soon as possible to prevent the attacking player from progressing forward with the ball.

The attacker can shoot early or dribble past the defender within the width of the two gates. Once the attacking player enters the box, if the defender forces the attacker wider than the width of the 6-yard box, the play stops. This is shown as the shaded red area in the diagram. In this “emergency” situation, the defender forcing the attacker wider than the 6-yard box severely decreases the chances of a shot resulting in a goal. This should be seen as a win for the defending player.

The defending player should be encouraged to show the attacker onto their weaker side whilst protecting as much of the goal as possible. Depending on the angle of the shot, the player may be instructed to prioritise covering one side of the goal- as with the examples in the analysis above.

This set-up can be progressed to allow for two central defenders and/or an entire back four.

Defensive phase of play

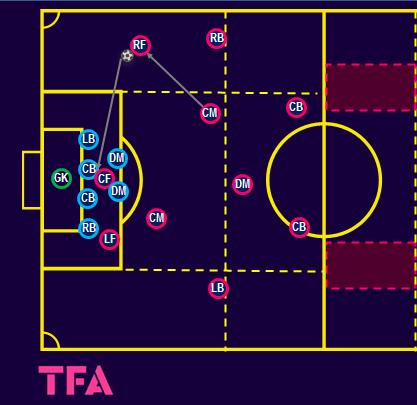

The training session can progress to a 10 against six phase of play with certain restrictions. The defending team can be underloaded to increase the opportunities for the opposition to attack and increase the amount of time defending the box. The exercise takes place in three phases and encompasses defending a long ball, defending one one-on-one in the wide area, and defending the box.

The play begins with the opposition team (pink) playing a long ball from their own half towards the working team’s (blue) penalty area. As with the example in the analysis of Manchester City, the blue team’s backline should drop off and allow the central midfielder to win the ball.

The midfielder should head the ball clear, targeting height and distance to give their team time to regain their shape. As the ball is travelling back towards the opposition’s backline, the blue team should push up, stopping when the ball stops.

The second phase of the exercise has the centre back playing into the wide area. This can create a one-on-one or a two-on-one overload, depending on what the coach wants to work on. The attacking team aims to work the ball into a crossing position by the side of the box. The defending team initially aims to prevent a cross with their one exposed full-back. Should it be delivered, the other members of the backline and the two defending midfielders have to position themselves optimally to defend the cross.

In the final phase of the exercise, the attacking team attacks freely but is allowed unopposed possession in the wide areas. As the attacking team builds the play, the defending team should move in relation to the ball corresponding with their playing position. This set-up allows the back four and defensive midfielders to prioritise defending the centre of the pitch. It then lets them defend crosses with their defensive shape intact.

A progression in this phase could be for a full-back to apply pressure to the cross in the wide area. This works on the reaction of the back four when they become detached from one another.

Should the defending team gain possession in all phases of the exercise, they should aim to transition by working the ball into the red areas. This can be achieved by clearing the ball or building the play.

Conclusion

As with attacking tactics, the defensive side of the game is always evolving with new ideas being implemented. This can result in established ways of thinking being turned upside down. At one point in time, not long ago, it would have been unthinkable for a centre-back to allow a striker a clear view of the goal. Now, it is common practice in the Premier League. Top-level coaches are constantly questioning even their own ideas. However radical new ideas first appear, they can soon become the new norm.

Comments