The role of a centre-back changed throughout football history and in the last decade the importance of having ball-playing centre-backs who are capable of beginning the attacks only grew. The ability to pick the next pass, be resistant under pressure, control the tempo of the game – these are modern requirements for a top centre-back outside of his defensive abilities. Centre-backs influence team’s attacking play in the final third with their passes, runs and positioning. The last aspect is probably more overlooked than others because it’s seemingly less important, but I think it’s a very interesting topic to pick up on. The positioning of centre-backs during the build-up impacts the attack to the same extent as does a movement of actual attackers. For example, Van Dijk’s push forward and then the pass over to Alexander-Arnold may have as much value in ball progression than the Englishman’s further delivery. This being a trivial example, centre-backs play a big role in attacking the structure of their team and their positioning is an important aspect to consider.

In this tactical analysis, I will look into different ways of positioning of centre-backs in the build-up, and how every way of positioning influences a team’s attacking dynamics in the final third. I will analyse several teams and try to depict the main patterns of play with different ways of positioning.

Narrow positioning

The usage of narrow positioning for centre-backs has several reasons:

- Shorter distances between centre-backs allow for faster ball circulation and hence, more passing options in a shorter periods of time

- Narrow positioning usually means the desire of a team to play more through central areas, with midfielders receiving behind the opposition’s first line of press

- Teams that play with a narrow pair of centre-backs don’t rely on them with long deliveries into the final third, and that responsibility usually falls on full-backs. Generally speaking, the narrower centre-backs position, the more oriented they become to play short passes

To observe patterns of play with narrow positioning of centre-backs in the build-up, I will use two teams as examples: Roberto de Zerbi’s Sassuolo and Sebastián Beccacece’s Racing. Both teams tend to use the whole defensive line – the centre-backs and full-backs – for the ball circulation in the build-up phase.

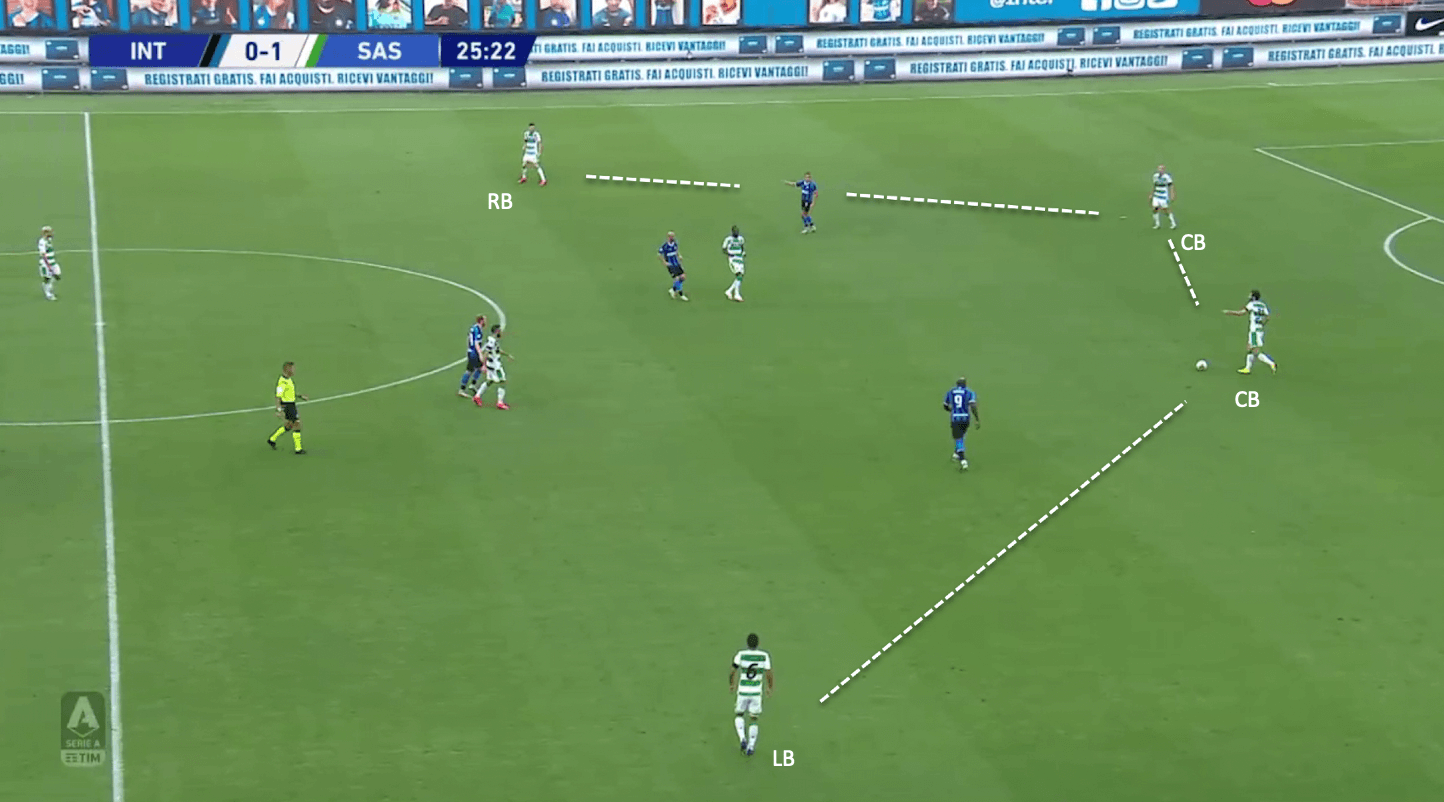

Here, Sassuolo full-backs are deep and a bit inside, in order to offer more passing options for centre-backs. With two CBs staying narrow, circulation of the ball around the backline and in the end getting the ball to full-backs or central midfielders behind opposition’s first line of pressing is the main goal of Sassuolo’s build-up.

The ball-far central midfielder moves diagonally towards the ball-carrier to receive behind Sanchez and Lukaku, and with the Chilean focused more on the other CB, the right-back can receive without much pressure. The lob balls over the opposition strikers towards one of the full-backs are the standard occurrence, as that allows to progress the ball further by the full-back himself or by passing the ball back to the centre or on the wing.

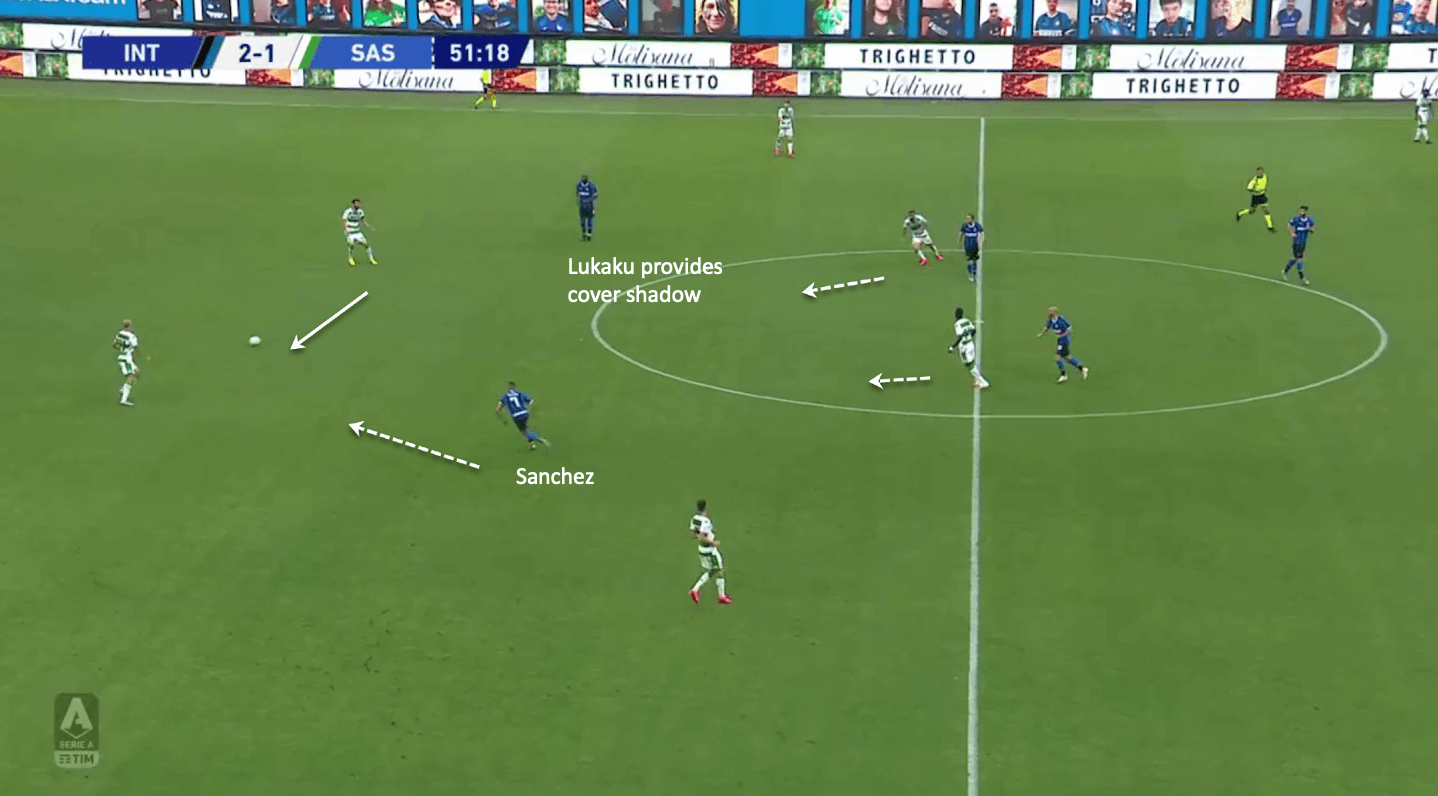

With centre-backs constantly engaging passes, sooner or later they invite press from opposition attackers. Usually, when the ball is played to the centre-back, the ball-near pressing player jumps at the receiver from sideways position, in an attempt to cut off the passing lane to the full-back. The chance of losing the ball becomes more possible at this point, and the help from central midfielders becomes important. In order to keep the ball in possession, the third-man principle can be used, with central midfielder receiving from the centre-back and then laying it off to the full-back, who usually is open. In the image below, Sanchez jumps at the centre-back, and the passing lane to the right-back is shut, while Lukaku is ready to press another centre-back from sideways too, at the same time cutting the access to the left-back. So, both midfielders, despite being heavily marked, come closer and offer passing options. Against one man pressing in the first line, midfielder would lay off the ball to the other centre-back, but with Inter’s aggressive press in this example the full-backs become the best option.

The more narrow partnership between the centre-backs oftentimes forces the press, but only in certain moments. With centre-backs able to quickly exchange passes and constant help from fullbacks and central midfielders, opposite teams try to press only after a certain trigger and showing little to no pressure on other occasions. In the shot above it was a good example of a pressing trigger with Sanchez jumping at the centre-back at the right time, leaving little time to pick the next pass.

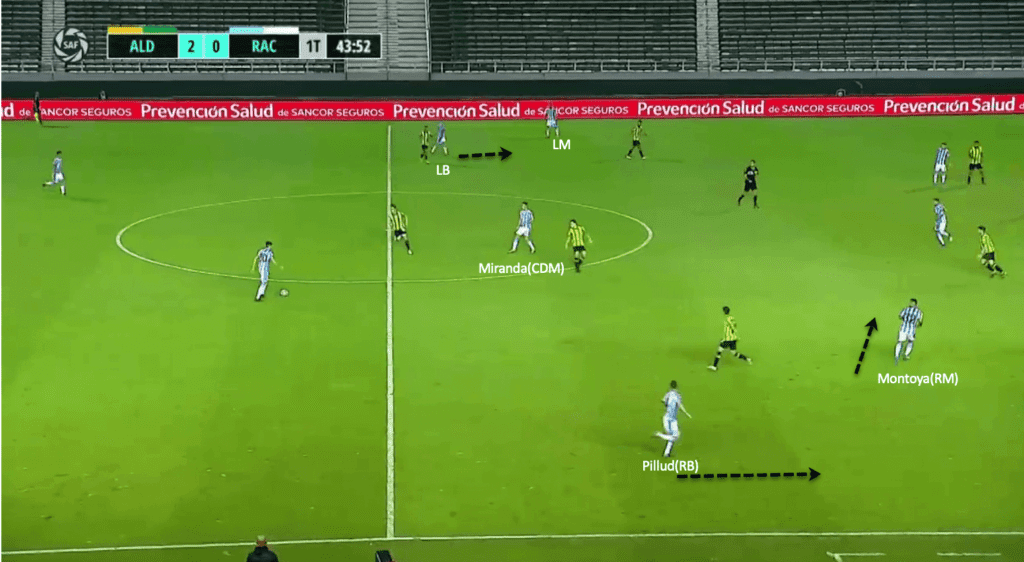

Beccacece’s Racing uses almost the same build-up structure as Sassuolo, however, the dynamics in the final third are different. The back-four remains with the full-backs relatively deep and pushing higher after wide rotations most of the time. Here Pillud pushes higher while the winger Montoya gets inside, completing the aforementioned wide rotation. Racing, just like Sassuolo, use narrow positioning of centre-backs and the same initial 4-2-3-1 formation. However, in Racing’s case, it’s only defensive midfielder Miranda responsible for collecting the ball behind the first pressing line. The other two midfielders, Zaracho and Rojas, also drop deep on occasions, but primarily it’s the defensive midfielder’s job to help circulate the ball around the backline. The main difference from Sassuolo’s build-up strategy in terms of positioning is having one less player deep in the middle, but the involvement of full-backs and the possession-oriented build-up remind of de Zerbi’s side.

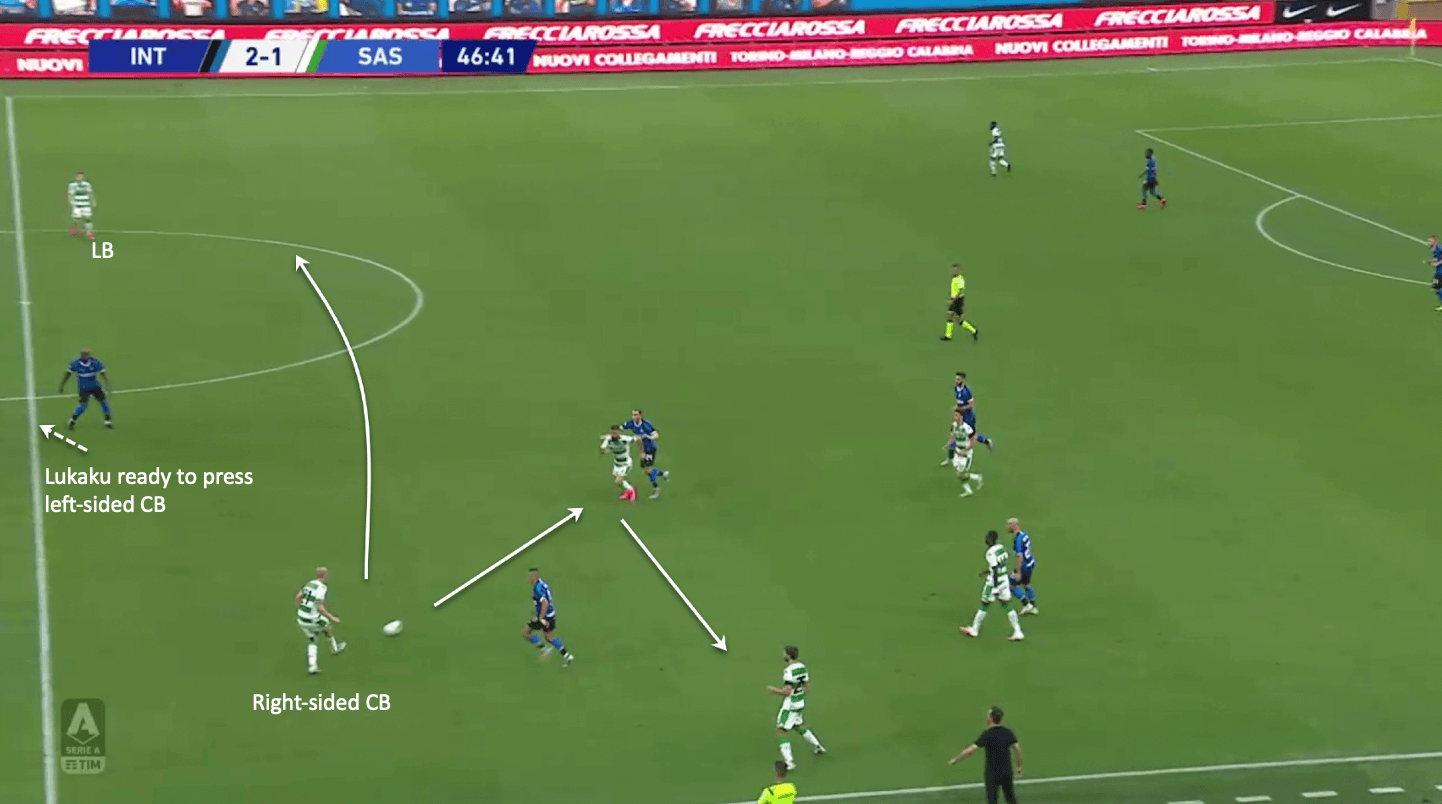

The help of full-backs and central midfielders against an organised and aggressive press becomes essential, and we can see that in the example below. With Lukaku marking the left-sided centre-back and Sanchez pressing the centre-back on the ball(again, pressure from sideways is extremely effective as it cuts out the full-back), with the help of midfielder the ball can still arrive to the right-back. Also, the passing option to the left-back is available, but it’s much harder to use it than the first variant.

Having two centre-backs positioned this way aims at controlling opposition pressing structure by moving the ball around and finding options in the middle, as well as on the flanks. Hence, full-backs and central midfielders become heavily involved in the build-up and have more time on the ball, compared to teams that use more wide positioning of centre-backs. Also, with lesser distances between the players, having centre-backs with different strong foot becomes important because in such tight spaces making one more touch can be costly.

In the next section of this tactical theory piece, I will delve into the next common variant – wide positioning of centre-backs.

Wide positioning

Using wide positioning also has its reasons:

- Wide positioning and passes between the centre-backs help to attract press from the first line, which then forces the whole opposition team to move up the pitch, and that, in its turn, creates an opportunity for a long ball behind the defensive line

- Teams that use wide centre-backs are set to play through the wide areas, and we will see that in this section

- The desire to play long and through wide areas minimises the importance of central midfielders in the build-up, as they are now more valuable in the final third as an attacking outlet and in grabbing rebounds after long balls, than as a way of progressing the ball centrally

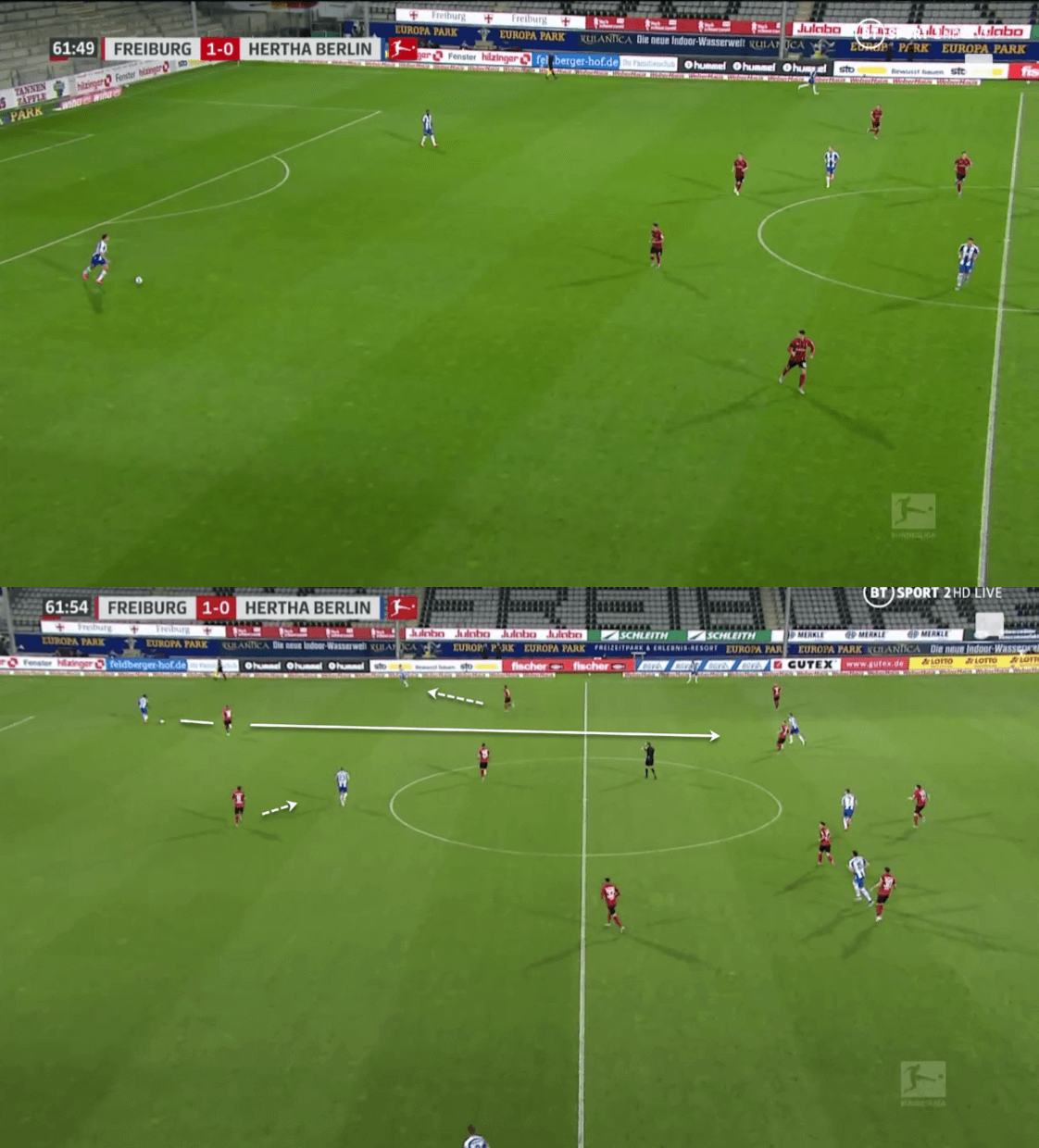

I am going to use Hertha Berlin to show examples of how wide positioning of centre-backs affects the attacking play. Since Bruno Labbadia has been appointed as a coach of the German club in April, he made Boyata and Torunarigha the starting pair of centre-backs. Both centre-backs position wide during the build-up, which eventually attracts press from the opposition, and then it creates an opportunity to play long. In the example below, the centre-back gets the ball on the left side and gets pressed with obvious options being cut, and he makes a pass forward to Ibišević.

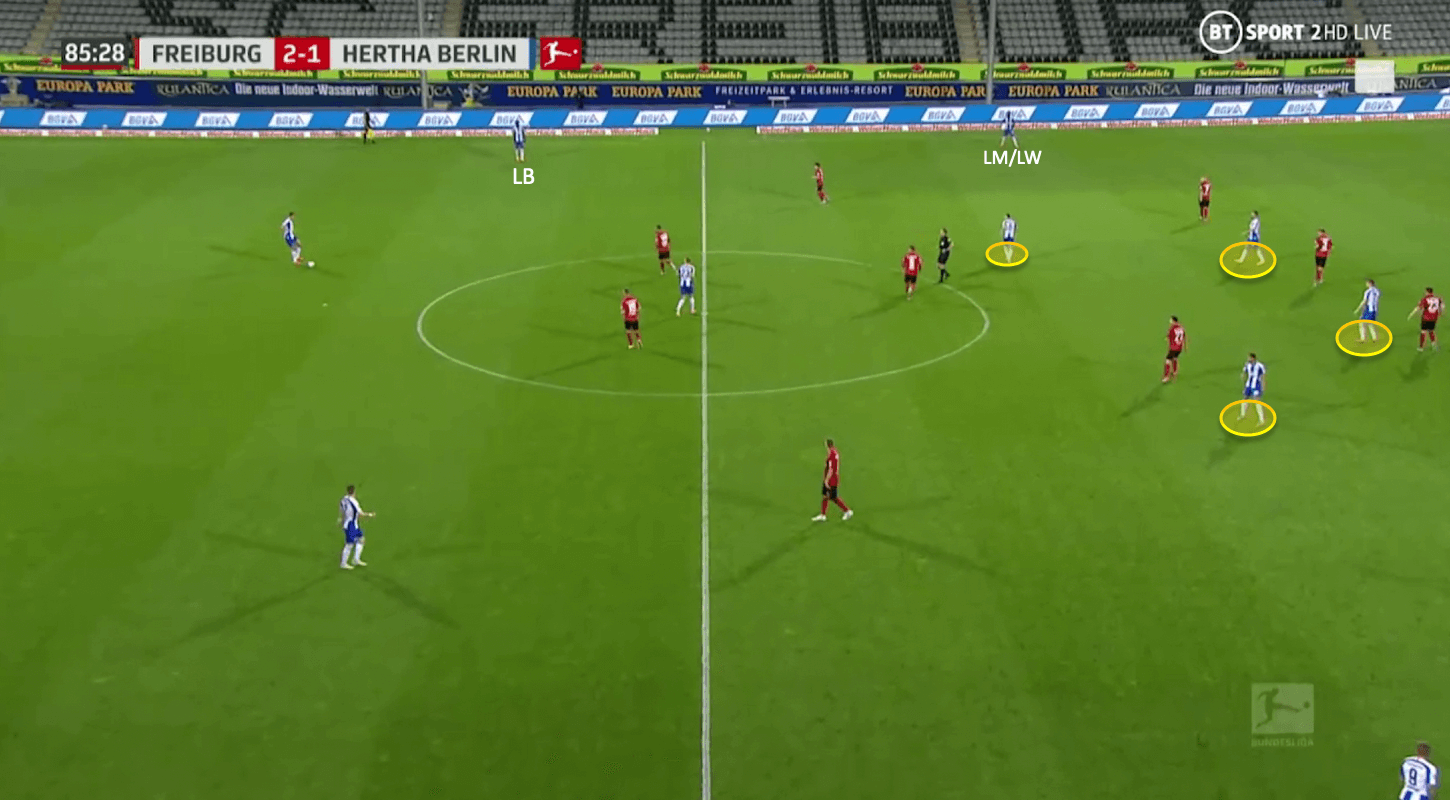

With centre-backs positioning wide, the full-backs usually push higher to join the attack. Either Plattenhardt or Pekarik push higher, increasing the number of attackers who are up against the opposition backline. The 8s in Grujić and Stark also actively support the attack by positioning in more advanced half-space, while forwards remain central. With one of the full-backs in a more advanced position, the wide rotation happens with a winger moving inside to accommodate the full-backs movement. Winger on the other side provides width with full-back staying deeper. In the shot below you can see this structure, two centre-backs stay wide and one of the full-backs stays in a deeper position, 8s in the half-spaces and right-back and left-winger provide width.

Hertha aims at having players in all five vertical channels when attacking, with a big focus on playing direct football with a lot of long, diagonal passes and passes behind the opposition backline. In a short period of time, Labbadia managed to instil simple and at the same time effective attacking structure.

The introduction of Torunarigha as a starting centre-back along with Boyata and a changed role of centre-backs in the build-up with their more wide positions and the switch to a more direct playing style proved to be a right decision.

From the direct comparison of these teams from last two sections of the analysis, the generalized conclusion can be made that teams with a more narrow pair of centre-backs tend to be more possession-oriented and using central areas more to progress the ball. Teams with more wide positioning, on the other hand, have more direct and high risk – high reward style. However, the centre-backs themselves spend more time on the ball when they are positioned wider because of lesser involvement of other players and the desire to invite press and create the opportunity to play in behind.

Unorthodox positioning

Apart from the more traditional approach with centre-backs being responsible mostly for getting the ball out of the backline and escaping the first line of pressure, in modern football, with more compact and organised defences, some interesting patterns can occur.

Using a ball-playing defender as an additional midfield player is a standard procedure in many coaches’ tactics to overload opposition midfield. When playing against a low block, having such defender becomes even more important. Players like Virgil Van Dijk and Harry Maguire do this consistently for Liverpool and Manchester United respectively, entering the final third and becoming one more situational midfielder. In the image below, Maguire drives forward and creates one more attacking player for Manchester United playing against Tottenham’s compact defensive structure.

Teams at the highest level look to create numerical superiorities when defending, especially in the wide areas, and oftentimes wingers and other attacking players bear a lot of defensive load. Chris Wilder’s usage of overlapping and underlapping runs from wide centre-backs is one of the most interesting ways to battle that phenomenon. Here, Chris Basham makes an underlapping run in the half-space, equalling Sheffield and Tottenham players on this flank, as well as providing depth to the attack. Centre-backs with good pace and on-ball ability help to create advantageous situations in the final third if used right and Sheffield’s centre-backs is surely one of the best examples.

Another example would be another way of wide rotation implemented by Antonio Conte at Inter, with Skriniar moving wide in the full-backs position, a midfielder taking his place in the backline, and the wing-back moving inside to accommodate Skriniar’s movement. This is another effective way to create an overload in wide areas with the help of centre-backs.

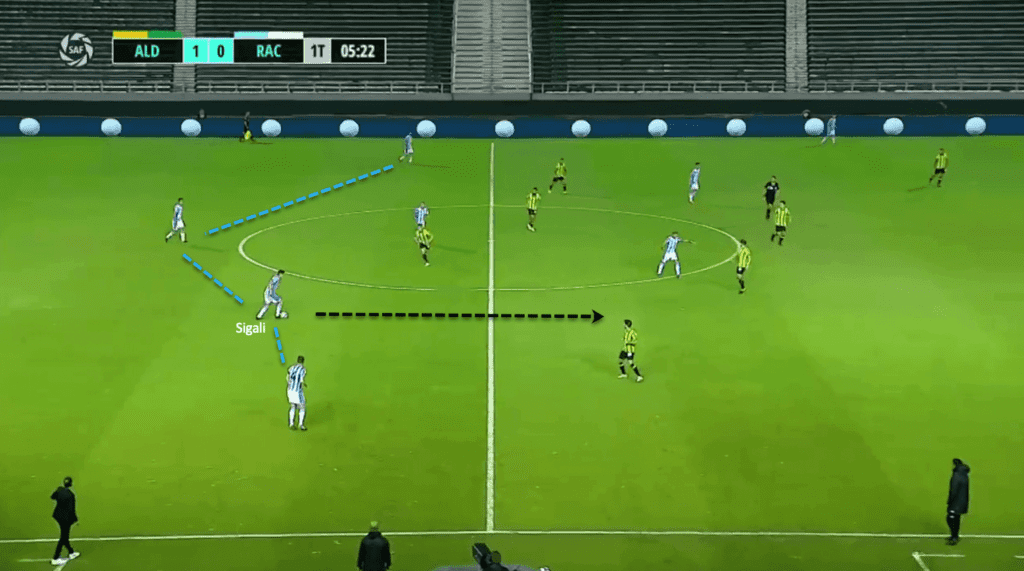

With a more narrow position of centre-back, they are more likely to face pressure coming from sideways, so sometimes a push forward with the ball can be an effective weapon for a centre-back to progress the ball forward. Here, Racing’s defender Sigali is about to get pressured from the forward, and while left-winger is preoccupied with the right-back, Sigali can drive forward with the ball at his feet and pick a pass at the brink of the final third. This is also another way to overload the centre with the centre-back, very similar to the example with Maguire.

Final remarks

This tactical theory piece was mainly aimed at explaining how different positioning of centre-backs at the beginning of attacks influences the whole team’s attacking structure. Obviously, centre-backs positioning during the game depends on many factors – opposition first line of pressing, the positioning of full-backs, the desire of the team to play through the centre more often or not – and teams use different positioning depending on the circumstances. I’ve used teams that have a more clear philosophy of how their centre-backs should position, in order to see how it impact the further development of attacks. It is a very broad and interesting topic to explore, and I haven’t even touched upon the attacking dynamics in three centre-back formations. There is surely a lot of angles to consider and more teams to analyse, and I hope this article shed some light on this topic or provided you with some tactical insights.

Comments