If you have read Jonathan Wilson’s extraordinary book, “Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Soccer Tactics”, you are well aware of football’s historic march from attack centred formations and subsequent footnotes.

As the book portrays, football tactics started with attack-minded systems, then became more defensive in the pursuit of results.

Like today’s game, tactical trends and formations followed a problem/solution progression.

Though the discovery and implementation of new tactics and philosophies emerged at a far slower rate than the modern game, no doubt due to professionalising the sport and use of technology.

Formations like England’s 1-2-7 and Scotland’s 2-2-6 in the first international match certainly strike the modern fan, coach and analyst as novelties of football history and, to an extent, they are.

The 2-3-5 pyramid formation will strike a similar tone.

You might ask how teams defended with just two defenders.

With football returning to more attacking philosophies, there are many historic influences, but none greater than the legendary Johan Cruyff.

His time at Ajax and Barcelona shaped the modern game, developing his philosophy and winning over disciples who have carried on his legacy.

In this tactical analysis, “Inverting the Pyramid” will serve as our guide to football’s earliest developments, then I will give an account of my research in the usage of outside-backs, a key cog in this project.

In the end, this article will show how modern tacticians have resurrected and implemented the 2-3-5 pyramid formation.

Examples of usage and tactical responsibilities will show how this is no longer a novel concept of a previous age, but an attacking system favoured by many of Europe’s elite.

Historic use of the outside-backs

The first 90 years of tactics followed a common tactical structure: high targets across the forward line and the remaining players taking away the middle.

As Wilson notes, football was highly individualized in the early days.

Dribbling ability was the mark of a great player and a physical approach was equated with toughness.

Early losses to the English led Scotland to develop the passing side of the game, but both approaches fit within the 2-3-5 pyramid formation.

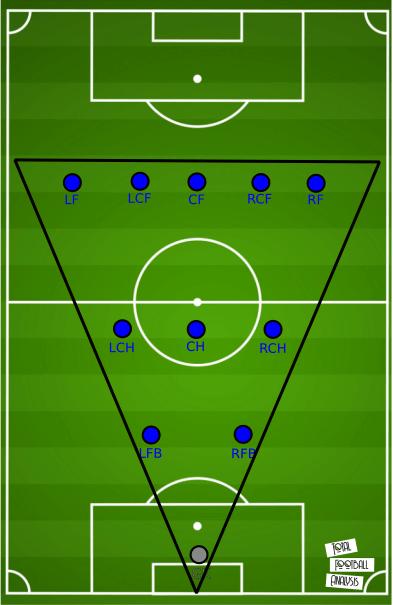

As you can see in the image below, the basic structure of the pyramid allowed for greater width in attack while protecting against central counterattacks.

The skilful forwards were covered by midfielders or centre-halves.

As possession was lost and teams moved into their defensive third, the centre-halves joined the full-backs to numerically account for the opposition’s forwards.

In the 1920s, legendary coach Herbert Chapman introduced the W-M formation.

A variation of the 2-3-5, the W-M layered the forward line, adding an element of central dominance and triangulation.

This 2-3-3-2 ensured losses of possession resulted in the opposition needing to clear another line of defence.

Chapman is known for placing results above style, so, while this evolution of tactics was more pragmatic and defensively sound, it does initiate a more defensive, pragmatic, results-based approach to the sport, a trend that would continue for several more decades as one.

Progressions included one, then a second, centre-half dropping in between the full-backs for further defensive solidity.

In fact, after the M-M, many teams moved towards a 4-2-4.

Historically, this was the next major evolution of tactics.

The centre-half now took on the roles previously assigned to the full-backs, making the centre-halves fully back.

Regardless of whether the centre-backs were flat or in a sweeper/stopper alignment, the full-backs of the past were seen more as defensive cover.

In my search for the modern outside-back, I analysed a number of historic matches.

Researching outside-backs who made all-time best lists led me to the following games.

- Inter Milan vs Celtic (25 May 1967)

- Brazil vs Italy (21 June 1970)

- Ajax vs Juventus (30 May 1973)

- Italy vs Brazil (5 July 1982)

- AC Milan vs Real Madrid (19 April 1989)

- AC Milan vs Barcelona (18 May 1994)

With the exception of Cruyff’s Ajax, those first three matches featured few rotations, opting for a more tactically rigid approach.

While the Brazil and Ajax teams of the 1970s were well ahead of their time, it was clear that these were the early days of a revolution.

Line breaking passes, positional triangulation and intense pressing were foundational to their approach.

Additionally, Brazil’s use of Carlos Alberto and Everaldo saw the outside-backs take on attacking responsibilities high up the pitch.

The success of attacking outside-backs produced a paradigm shift.

Rather than forcing the creatives into congested midfields, teams used the outside-backs almost as an additional midfielder.

As the game evolved, outside-backs became more involved in the attack, giving us players like Roberto Carlos, Javier Zanetti, Philipp Lahm, Dani Alves and Marcelo.

Now, we are witnessing another progression, which is really a return to our footballing roots.

Inspired by the totaalvoetbal of Michels and Cruyff, Barcelona’s Juego de Posición and the renewal of Ajax point to an evolutionary advancement in attacking football.

Following Cruyff’s petri dishes, Ajax and Barcelona, we’re seeing his students and their direct rivals adapt the fundamental tactical principles of the 2-3-5 pyramid to the modern game.

With a basic understanding of the pyramid’s history and development of modern outside-backs, it’s time to look closely at the manifestations and variations of the 2-3-5 in play today.

Rather than giving an overview of each team, we’ll investigate the tactical theory driving this new application of the pyramid, showcasing some of the leading teams in the world and noting some of the tactical nuances that distinguish the clubs.

Three forwards occupy the centre

Last summer, the transfer of Antoine Griezmann from Atlético Madrid to Barcelona led many, myself included, to ask how the Catalans would deploy three centre-forwards in the starting lineup.

Despite some inconsistencies in attack and issues beating the low block, Barcelona average a staggering 2.25 goals per match, conceding an average of 1.03.

Though the side is not nearly on par with the Golden Generation, which was developed by Cruyff and coached by Pep Guardiola, the attacking mentality of Barcelona is ever-present.

With the side commonly featuring three centre-forwards, the basic idea is to occupy the middle of the pitch and provide width through the outside-backs.

The reasoning behind this tactical motive is that teams are already dropping off into deep blocks.

Whether or not Barcelona, or any of these other pyramid teams, dedicates players to Zones 14 and 17, the opposition will.

Without players sitting in those zones, it’s extremely difficult to connect crosses, engage in combination play or run in behind the lines.

As Barcelona enter their attacking half of the pitch, the centre-forwards tend to occupy the central channel.

The one exception, of course, is Messi, who drops into a more standard creative midfield role.

One variation we see with Barcelona is that, rather than positioning Messi in that highest line, allowing opponents to largely negate his influence, Barcelona use players like Arturo Vidal and Ivan Rakitić to switch positions with the Argentine.

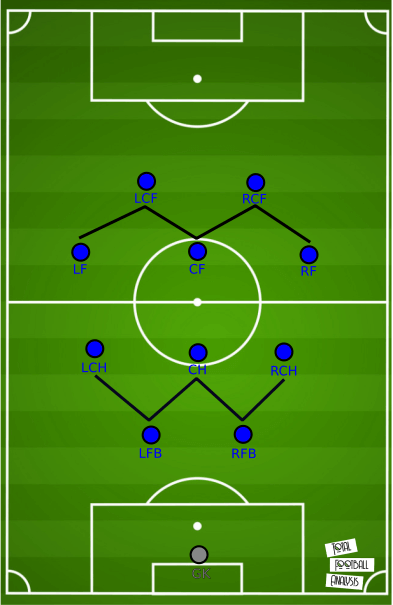

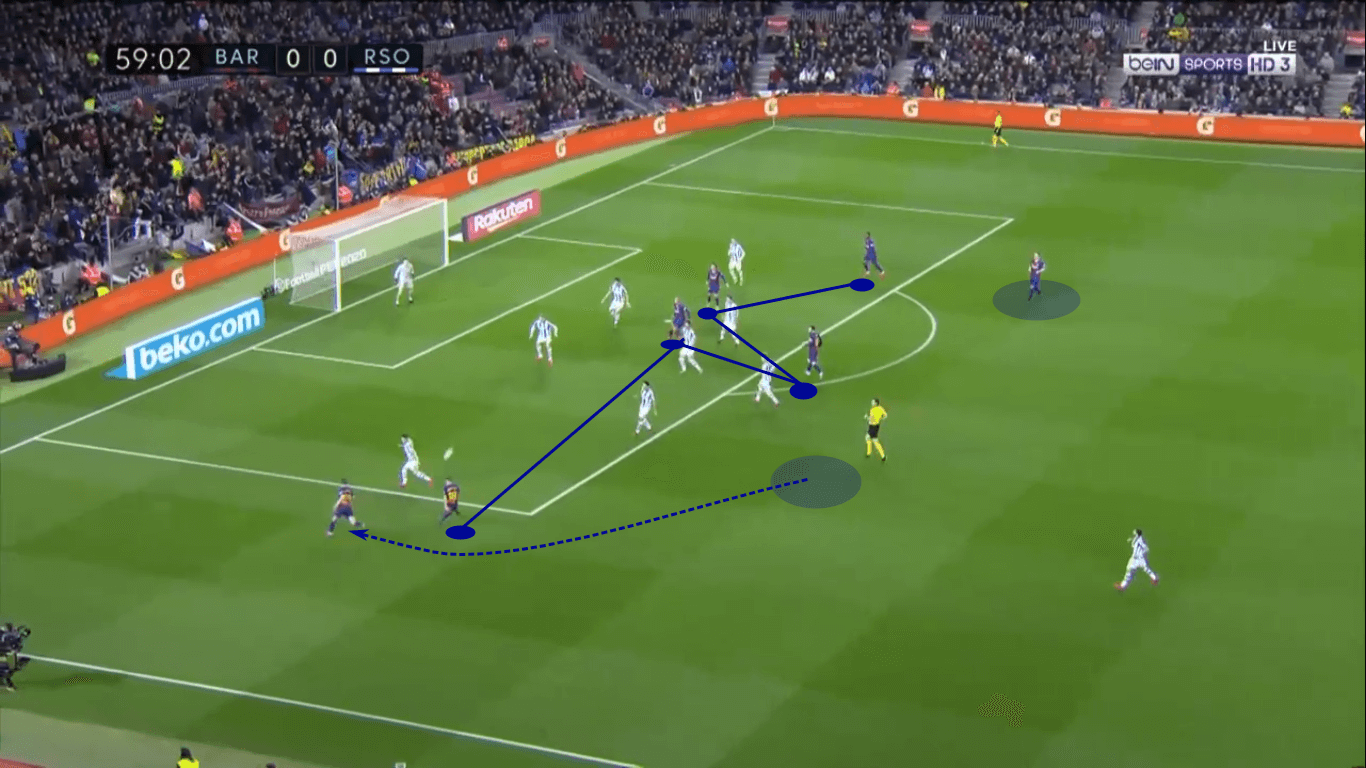

As you see in the image below, by situating the three centre-forwards so closely to each other, the defence becomes horizontally compact, freeing the wings and half-spaces for the outside-backs.

If Barcelona have the ball in a wider area, Messi will remain outside the box, allowing Vidal or Rakitić to contest the aerial ball.

If the outside-back is able to deliver a pass on the ground, a sequence of runs ends with Messi running into the zone near the penalty spot with Vidal or Rakitić dropping outside of the box.

Near-post runs from Suárez typically free passing lanes to Messi, while the far-post runners pull defenders towards the goal line and away from La Pulga.

With Messi starting in a deeper role, he can then move untracked into the box.

Three centre-forwards not only gives Barcelona numbers in the box, but it also forces the opponent to call in defensive reinforcements.

Even if the opposition recovers or clears the ball, few numbers high up the pitch, deep starting points and Barca’s numbers around the ball in the counter-press see most attacks fizzle out before they’ve properly started.

High and wide outside-backs

Ajax took the world by storm in last season’s UEFA Champions League.

Defeating Real Madrid and Juventus, then nearly defeating Tottenham in the semi-final, the Dutch side offered a thrilling, dazzling brand of football.

Much like the Golden Era at Barcelona, the man painting the developmental picture was none other than Cruyff.

A few stints with Ajax from 2008 to 2012 saw Cruyff return to his boyhood club, reforming the program and helping create an environment that would once again produce world-class academy talent.

The most recent Ajax sides are a direct result of his philosophy and innovation.

In Ajax’s classic 4-3-3 system, we’re seeing a greater emphasis on the forwards occupying the central channel and half-spaces.

Much like Barcelona, this side does like to free up their top playmakers.

Future Chelsea man, Hakim Ziyech, is one of those players.

With his sensational dribbling and crossing ability, it’s common to see the right-back, often the young American, Sergiño Dest, switch roles with him.

Ziyech and Dest rotate frequently, but it’s Dest’s discipline to get into a high and wide position that allows the rotation to occur.

Between Ajax’s outside-backs and wide forwards, one will remain high and wide on the wings while the other moves more centrally.

If the wider of the two players prefers isolation to engage 1v1, the other moves closer, sometimes into, the central channel.

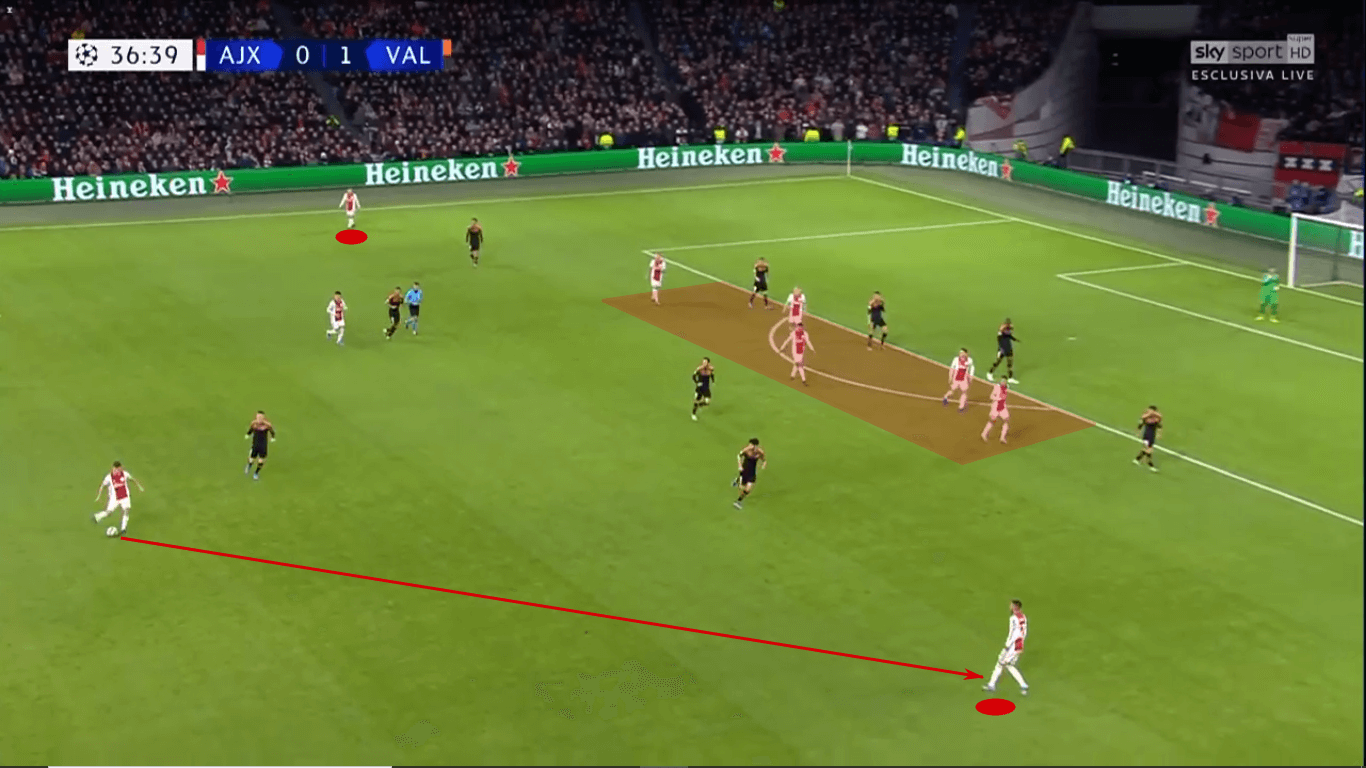

In the example below, we see Noussair Mazraoui starting against Valencia and moving centrally to free up space for Ziyech.

While most cases of the pyramid structure link the outside-backs with the forwards, this scenario is a really nice example of the flexibility of the system.

As the centre-midfielders move higher, the players in the outside-back roles drop off.

A couple of reasons for this are the security of the rest defence and getting key attacking targets outside of the opponent’s defensive structure.

With the centre-mids pushing higher and the outside-backs, which includes Ziyech because of his switch in roles, Ajax now have a high wide target to deliver a cross and five possible targets in the box.

Plus, with Ziyech alone on the wing, Valencia must move their defensive shape to pressure him and contest his delivery.

Gaps emerge for the five players at the top of the box.

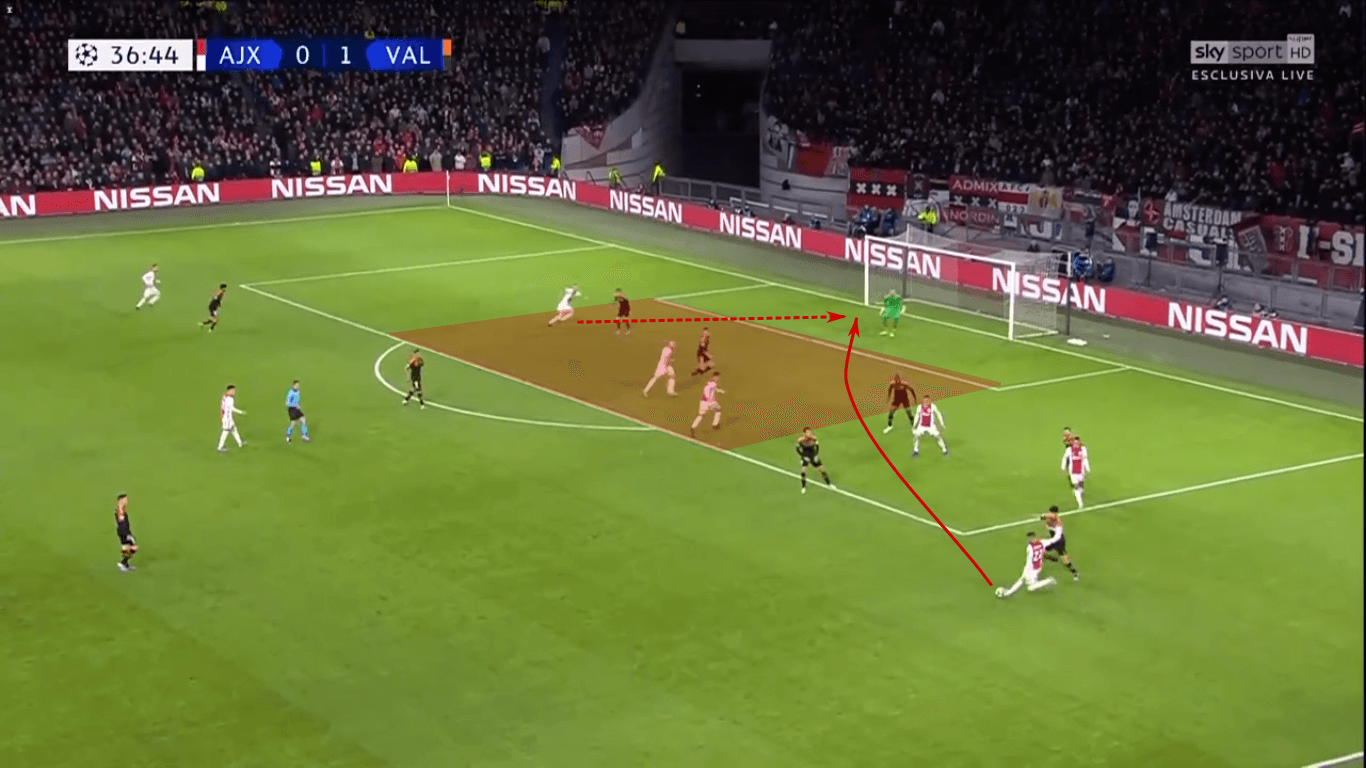

As Ziyech delivers the cross, his bending, far-post effort is just a foot ahead of his teammate.

Between the initial pass to Ziyech and the two Ajax players in support, Valencia’s lines are disorganized, opening up a 3v2 opportunity in the box for Ajax.

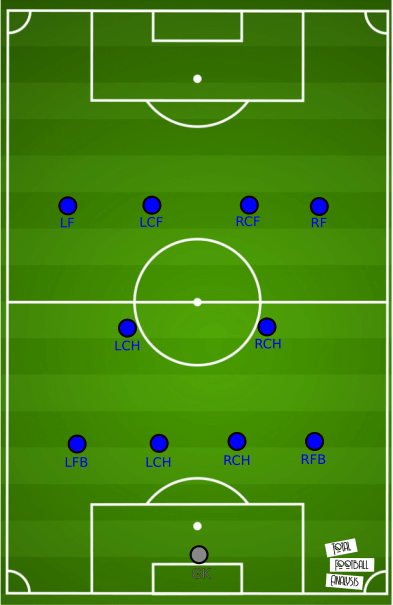

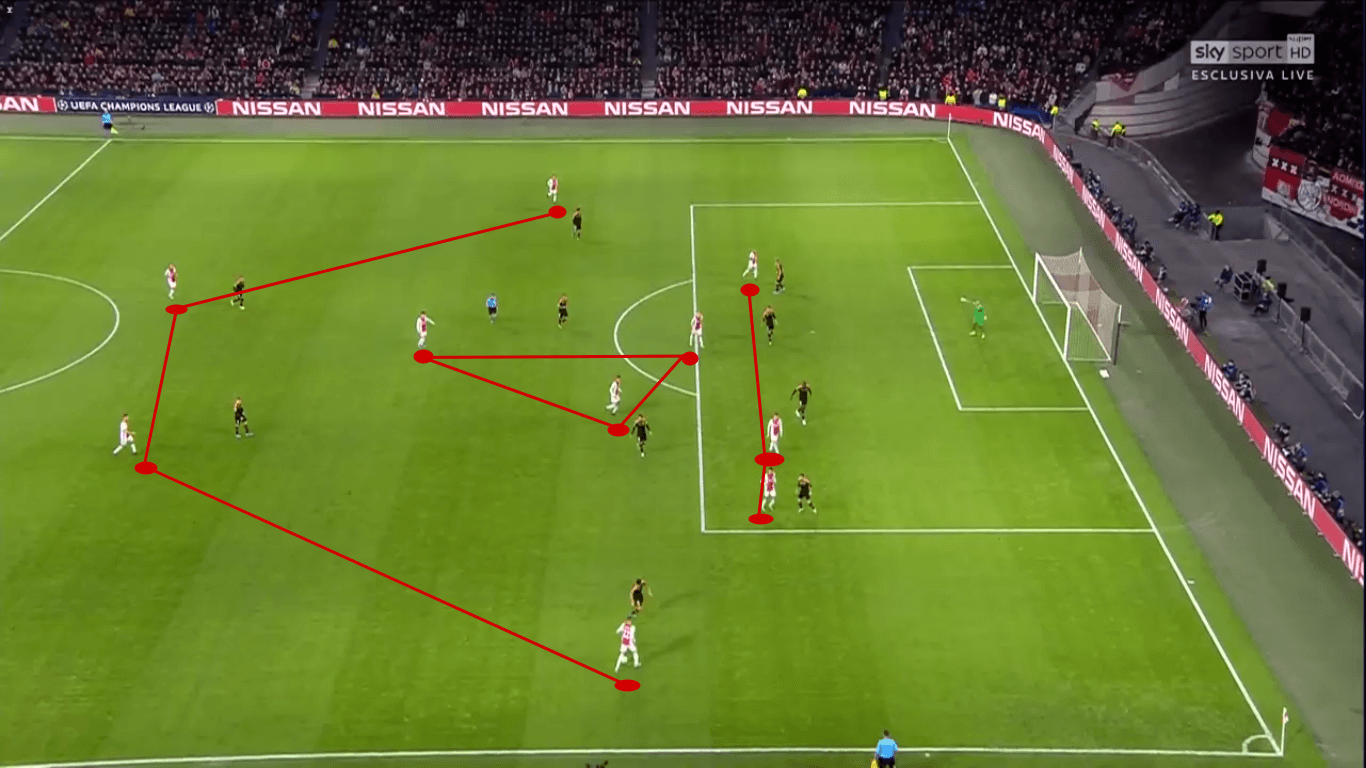

From a different angle, we can see Ajax’s attacking setup.

A line of three forwards in the box, three midfielders triangulating their rest defence and the two wide players looking to deliver crosses into the box.

Whether it’s the outside-back offering width or a teammate who has switched role with him, the attacking responsibilities of the outside-back role far outweigh the defensive duties in the pyramid.

An outside-back must push high up the pitch, either offering width or enabling a teammate to do so.

Since the opponent is compact in defence and wide outlets are typically not immediately available, the outside-backs must push higher up the pitch to pin the opponent back.

Since the pyramid protects against counterattacks with the two centre-backs and three centre-mids taking away the middle of the pitch, the wide players have few defensive concerns if possession is lost.

The reward of pushing outside-backs higher up the pitch outweighs the risk of opposition counterattacks through the wings.

With the team’s defensive shape eliminating the most direct threats, the wingers are free to move higher up the pitch to take on important attacking duties.

Midfield pragmatism

The evolution of the outside-back has impacted the way midfielders are utilised.

Rather than the classic #10 of old, we’re seeing many midfielders operating in an 8/10 hybrid role.

This is especially prevalent in the pyramid.

As the creatives have moved into the spacious landscapes of the wings, the need for defensively competent midfielders has skyrocketed.

A classic #10 with little, if any, defensive responsibility simply doesn’t have a place in the game.

Unless your name is Lionel Messi, whose attacking output far outweighs his lack of defensive contribution, minutes for the true #10s are dwindling.

One of the sides that epitomises this approach is Liverpool.

While the midfielders are skilled box-to-box technicians, none fit the mould of a true #10.

With their brilliant options at forward and outside-back, creative roles are largely unnecessary in the midfield.

Rather, it’s the versatility and mentality of the group that defines their roles.

In possession, they offer ball retention and intelligent positioning against the opposition counterattack.

Out of possession, it’s a hard-working group that reads play brilliantly, eliminating threats with interceptions and timely tackles.

Those are the core characteristics of the pyramid midfield.

They’re not the flashy #10, nor the clumsy #6.

Instead, they’re players who are comfortable in and out of possession.

Their discipline, especially in possession, safeguards the side against a counter-attack by taking away the middle.

That, in turn, offers greater freedom in attack to the wide players.

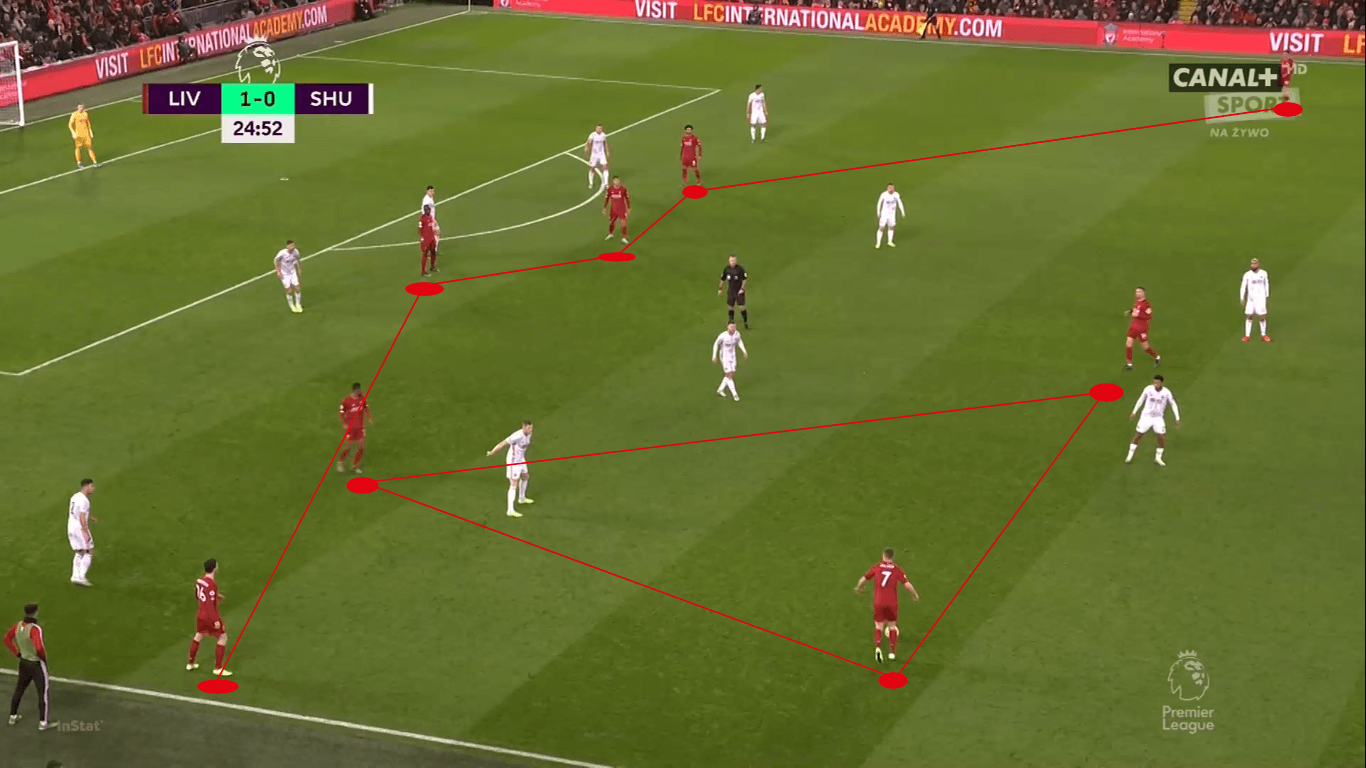

In the home match against Sheffield United, we saw the pyramid attacking structure clearly in use.

With Trent Alexander-Arnold and Andy Robertson pushed high up the pitch, it was the three centre-midfielders who assisted the centre-backs with progression.

With each layer of the pyramid, the width increases, offering connections from one line to the next while protecting the centre of the pitch.

As Liverpool advance the ball, the midfielders overload near the ball, offering numerical superiority and, if necessary, a quick transition to counter-press.

Georginio Wijnaldum is the highest midfielder in the image below.

While James Milner and Jordan Henderson are positioned more conservatively, Wijnaldum offers a line-breaking pass or a switch in roles with his teammates.

Much like Ajax, we do see Liverpool use positional rotations to create space, free up key attackers and disorganise the defence.

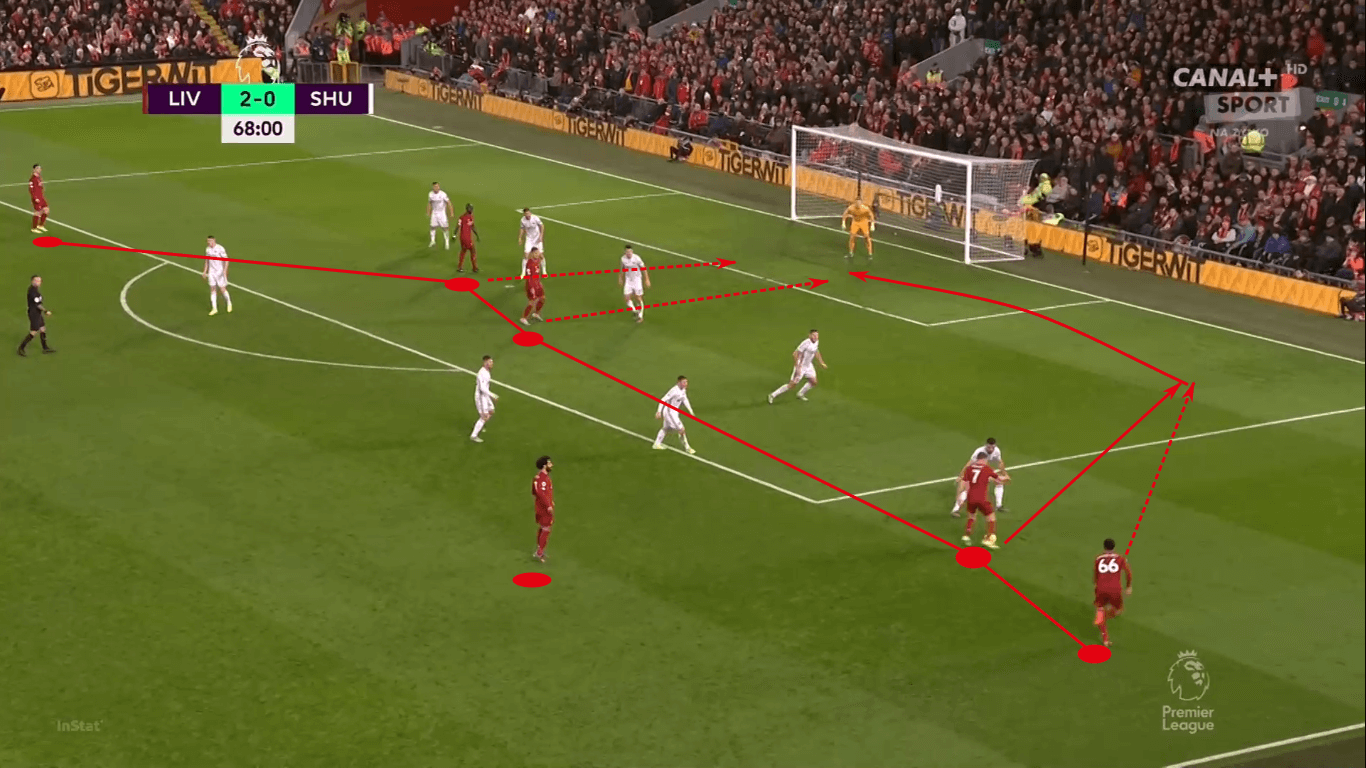

In the image below, Liverpool are initiating their move towards goal.

As Milner dribbled forward, Mohamed Salah swapped roles with him.

With the 2v1 on the wing, Milner’s job is clear…play Alexander-Arnold behind the line for a crossing attempt.

While a classic #10 might scoff at the simplicity of the role, the 2-3-5 attacking shape doesn’t require midfielders with world-class playmaking ability.

With the number of high-quality attackers in the highest line, two-way play is a necessity for the three midfielders.

Milner’s simple leading pass to TAA is an example of the rotational intelligence and attacking execution necessary from the three midfielders.

Balance is the key.

In addition to their attacking responsibilities, the balanced skill set of the midfielders is equally important in defence.

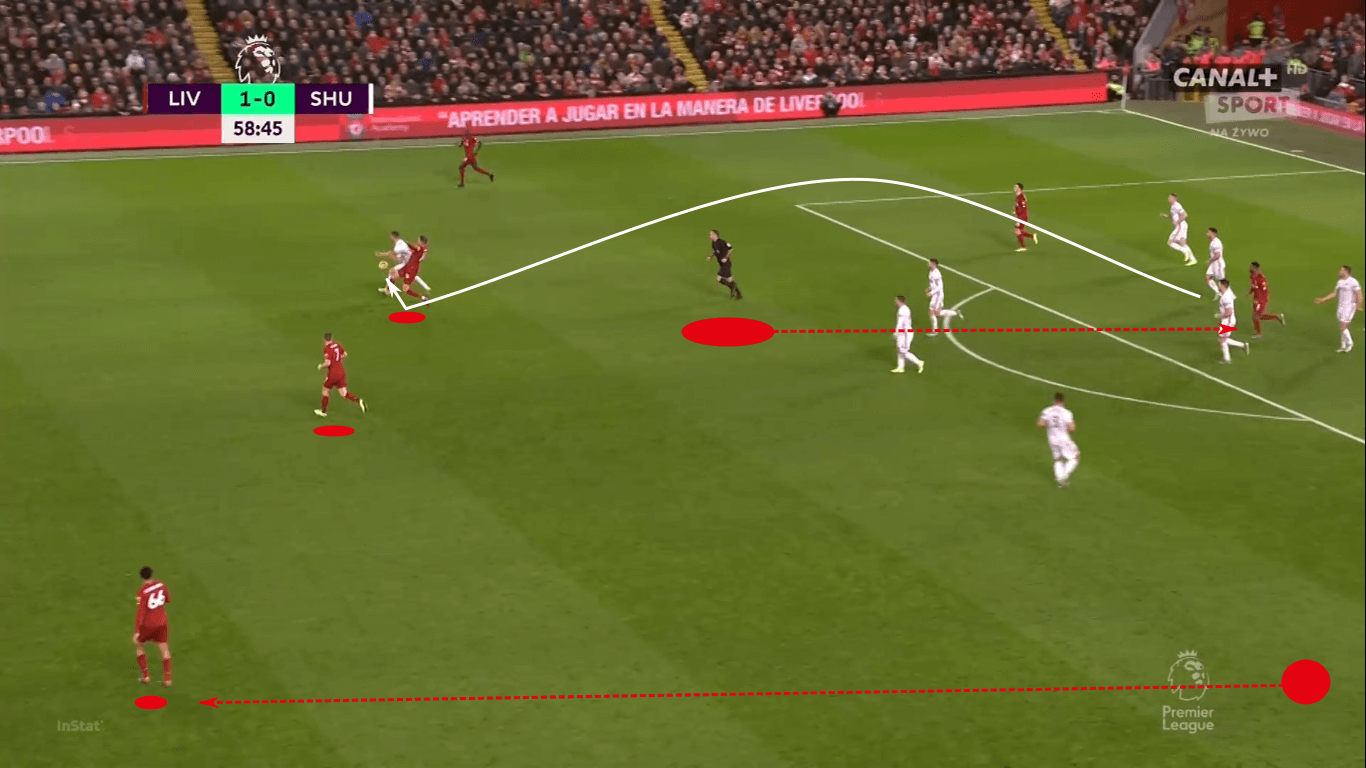

Watch a team like Liverpool and you’ll see the rest defence of the midfielders protects the side against counterattacks, enables quick counter-pressing and creates defensive duel with numeric superiority.

Sticking with that match against Sheffield United, Liverpool held their opponent to 26% possession, two shots (both on target) and a 0.76 xG.

Sheffield simply couldn’t find their way out of the press.

Liverpool’s counter-pressing and intelligent rest defence allowed the midfielders to reclaim the ball and restart possession within seconds of a loss.

In the images below, the moment Sheffield manages to clear the ball, Liverpool are there to contest it, recovering the ball immediately and restarting the attack.

Given the quality of attacking options Liverpool has up top and in the wings, a more pragmatic midfield, offering a balance of ball retention and defensive ability, is ideal for a 2-3-5 midfield.

Roles for players who can only play on one side of possession or the other are falling by the wayside.

While two-way ability is becoming a necessity for all players, the 8/10 hybrid midfielder is the most obvious sign of the times.

Box-and-one

Since we started with Barcelona, a club shaped by Cruyff’s philosophy, it’s fitting to end with his most famous student, Pep Guardiola.

Though I could have used his time at either Barcelona or Bayern in any section of this analysis, this is a great area to give Guardiola credit.

Acclaimed for his side’s attacking intelligence and fluidity, and rightly so, the defensive work of his teams rarely gets the attention it deserves.

Though Liverpool and Real Madrid have allowed fewer goals, Manchester City’s xGA is comparable to those two sides.

Madrid lead the way at 0.80 xGA, followed by Liverpool’s 0.90 xGA mark, but City is right behind their domestic rivals with a 0.94 xGA.

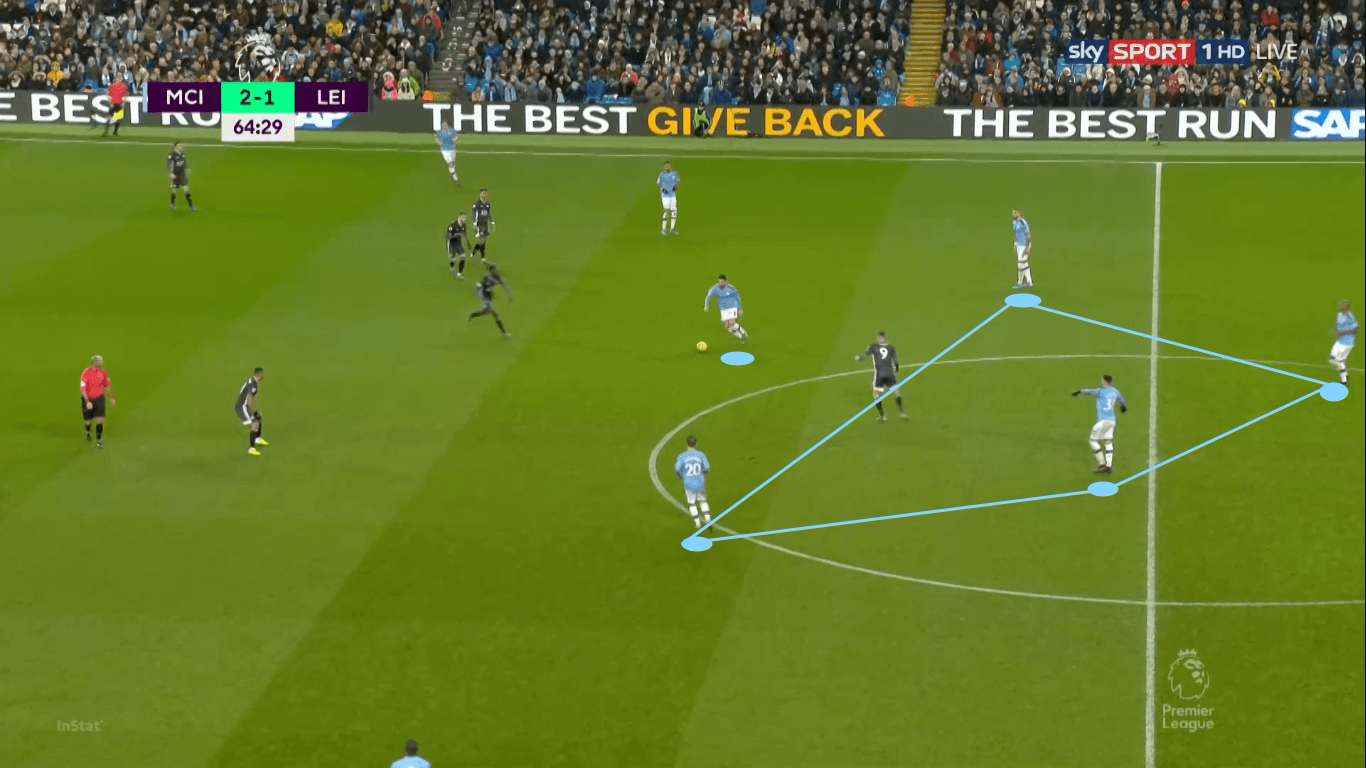

Averaging 64% possession, City’s rest defence is key to stifling counterattacks.

Like the other clubs in this tactical theory piece, City populate the middle of the pitch with the defenders and midfielders.

One distinction is that you typically see Kyle Walker as an inverted outside-back.

That leaves the right-wing free for Kevin De Bruyne moving from a central, out of possession position into the right half-space and wing.

The other two midfielders, in addition to possession support, complete the rest defence shape.

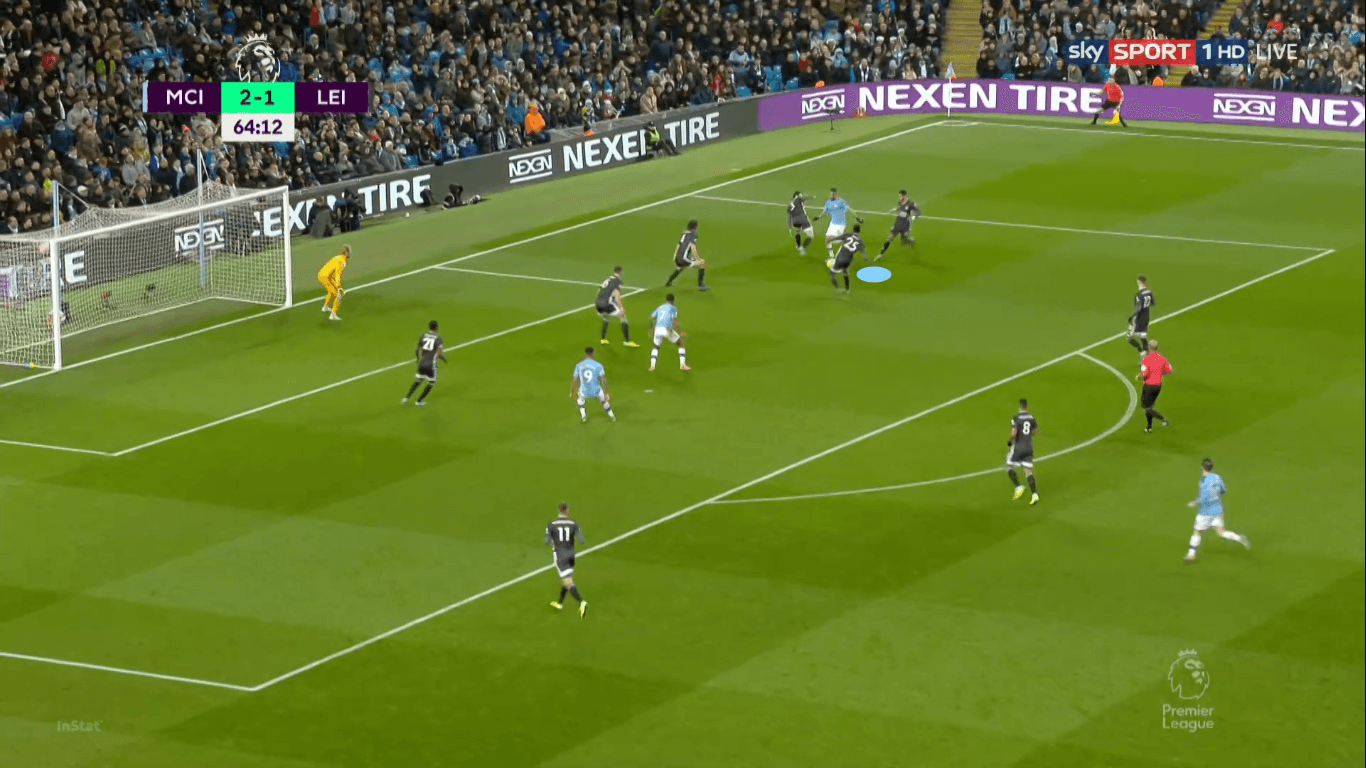

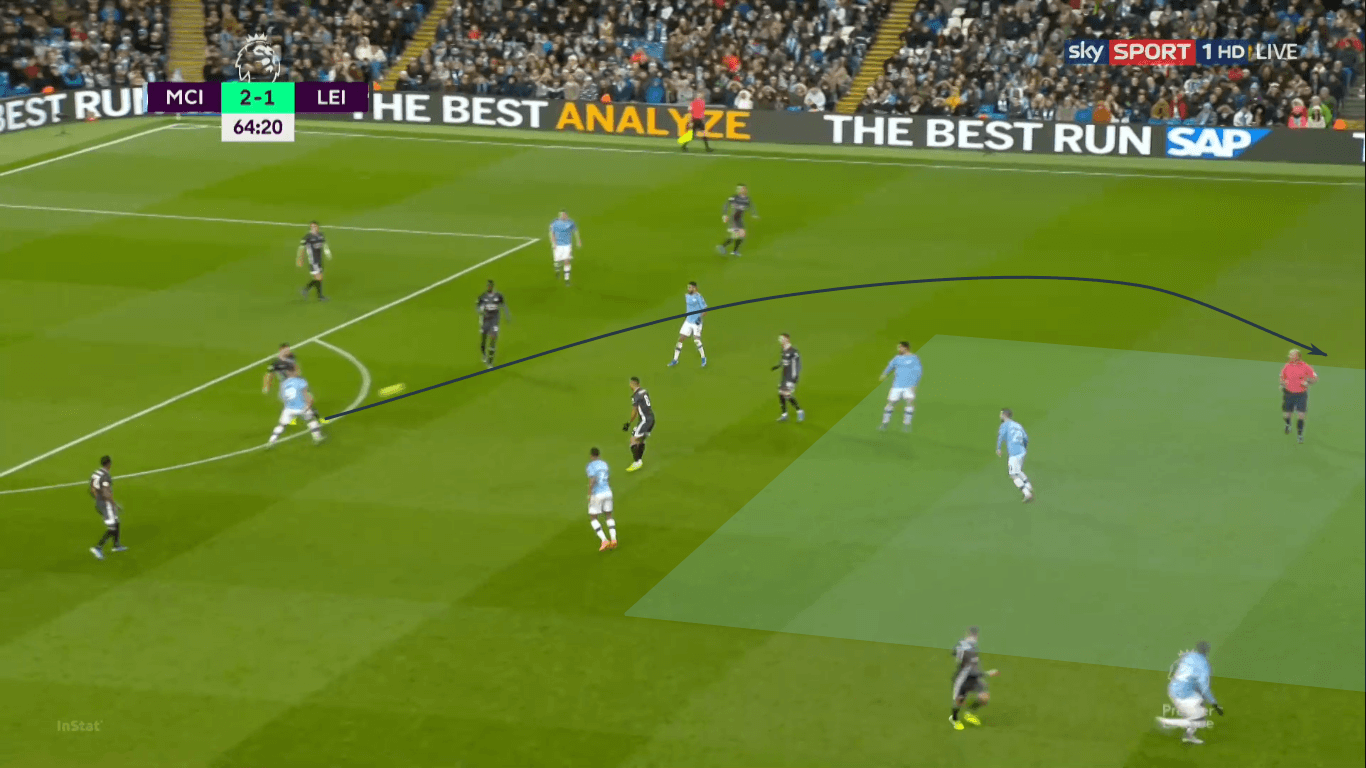

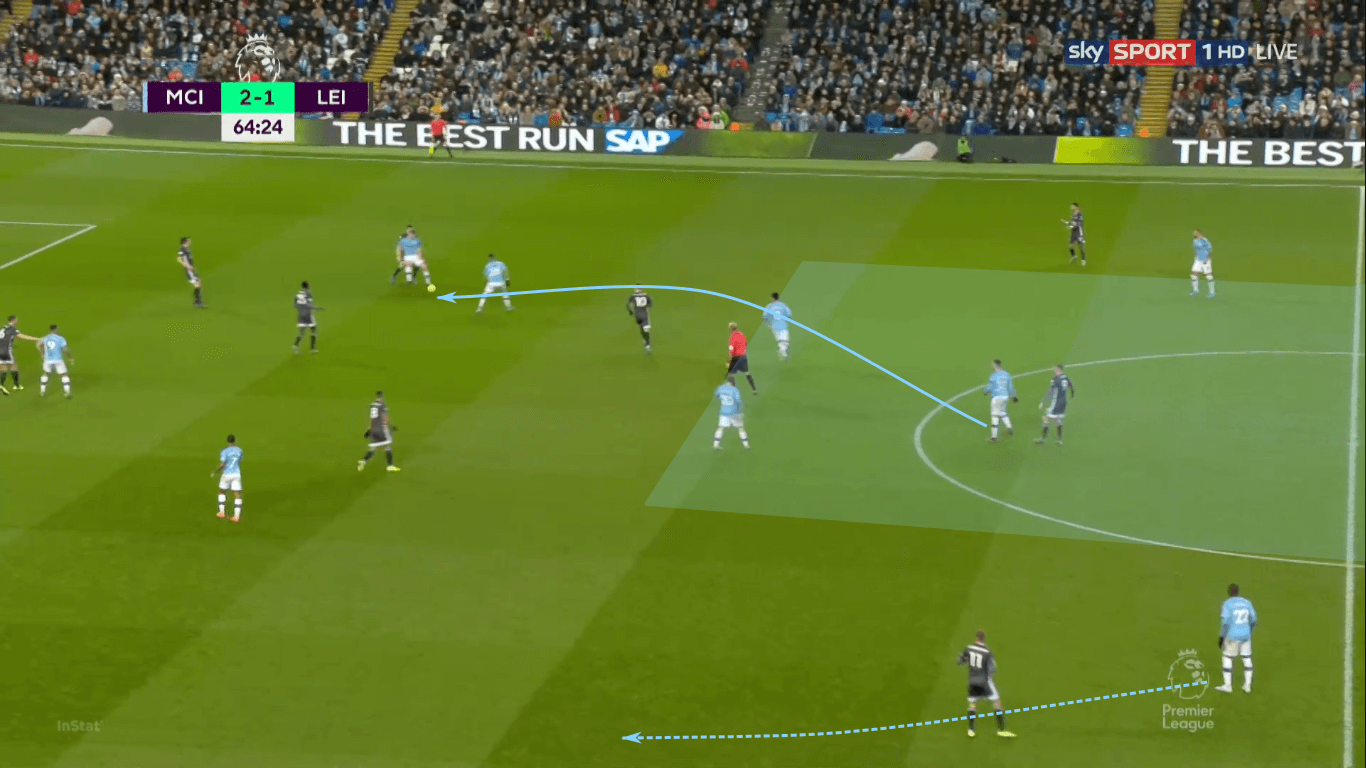

In the match against Leicester City, Riyad Mahrez dribbled into a bad situation and lost the ball.

As City counter-pressed, the players at the back of the formation tightened up their lines.

When Leicester was finally able to clear the press, they attempted to hit their high target.

Notice that, even though Leicester had numbers around the ball, the pressure on the ball carrier and risk of playing out on the ground forced the clearance.

As the ball is played centrally, City steps up to touch the ball back into Leicester’s end.

Since City’s midfield was behind the Leicester players as the ball was played to Jamie Vardy, they were better positioned to claim the second ball.

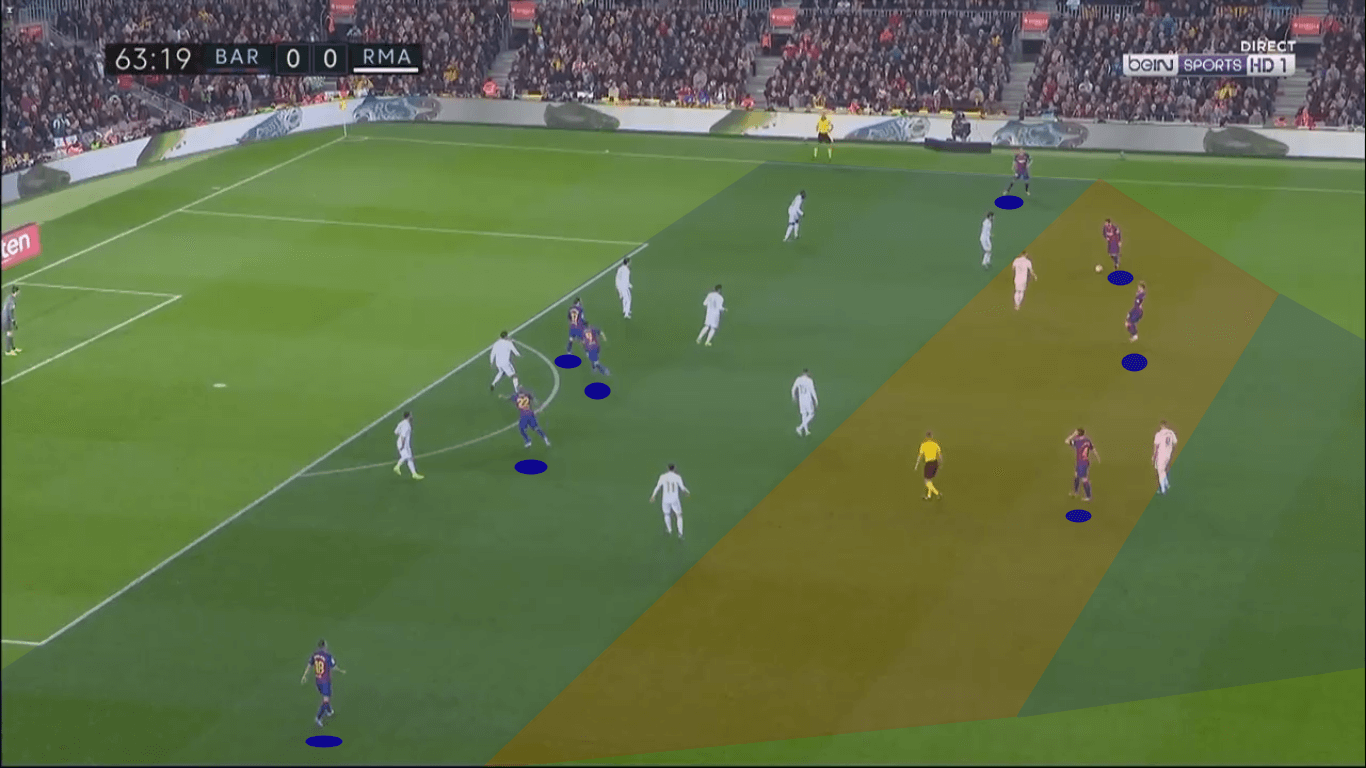

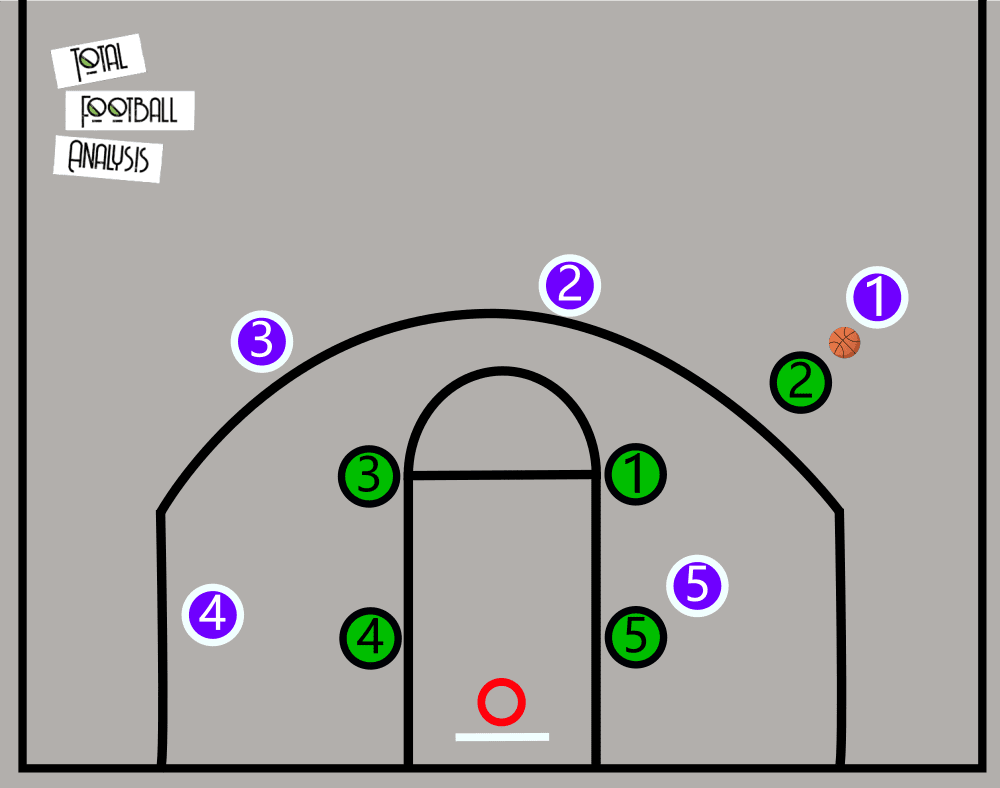

One thing that stood out as City defended is that the five deepest players had a shape that resembles the box-and-one in basketball.

In fact, this is a common feature of rest defence when attacking in the pyramid.

In basketball, the basic structure is the formation of the box, keeping the two post players near the basket and two of the remaining players near the foul line to guard the perimeter.

The final player, usually the best defender of the three, can them operate in a man-to-man defensive role.

Rotations in and out of the box-and-one allow the team to release a player to pressure on the perimeter while allowing the team to eliminate, or at least contest, post and mid-range shots.

Relating the box-and-one to football, two centre-backs makes up the further of the two lines, but the midfield three, or Walker plus two midfielders in this case, complete the box and leave a player free to adapt to the conditions of the match.

It’s typically the player nearest the ball who adapts his positioning to the context of the match while the other two midfielders cover the central channel and half-spaces.

Zonal protection allows for context-dependent man-marking.

As City restarted their attack, the box-and-one took shape with the two centre-backs, Walker and Bernardo Silva providing the basic rest defence shape while İlkay Gündoğan pushed higher in attack.

Though the wings offer an obvious counterattacking opportunity, it’s preferable to give the opponent the wing while safeguarding the middle.

The results are delayed attacks, protection in front of the goal, funnelling play to a less threatening area and reducing the likelihood of an all-or-nothing type challenge.

Conclusion

Once a formation of yesteryear, the 2-3-5 pyramid has found its way back into the game.

While the game has changed a great deal, the creativity and intelligence of the coaching community manifest itself when an old concept is adapted to meet the modern conditions of the game.

Even though this 2-3-5 doesn’t exactly play out the way it did in the past, it does join the solution of previous generations to the problems present in the modern game.

Committing to the pyramid is tying yourself to attacking football, accepting the risks as well as the rewards.

It’s an admission that aesthetics plays a vital role in the game, a belief that results and style are compatible.

Those are beliefs that Johan Cruyff brought to the sport.

Though he is gone, his legacy lives on through the clubs he reinvented, players he developed and family who care on his philosophy.

With the resurrection of football’s 2-3-5 pyramid, we have the great opportunity to enjoy the courageous, intelligent, aesthetically pleasing attacking football that Cruyff valiantly promoted.

Comments