Playing with a back three has enjoyed a kind of renaissance in recent years with many top-level teams implementing the system. Jose Mourinho and Pep Guardiola, the game’s elite managers who normally favour a back four, have switched to using a three on occasions in recent times. It is also, of course, the preferred system of Antonio Conte, at Chelsea and Tottenham, and Simone Inzaghi with this season’s UEFA Champions League finalists Inter.

This tactical analysis is going to focus on teams that play with two strikers in a 3-5-2 and how those forwards interact. This tactical analysis will first analyse the tactics involved in the forwards’ movements. It will then suggest how coaches can implement this tactical theory to create goalscoring opportunities.

Receiving from central areas

Inzaghi’s Inter consistently played with a front two this season. In the Champions League final, World Cup winner Lautaro Martinez was paired with Romelu Lukaku and Edin Dzeko. These pairings could be referred to as a classic “big man-little man” combination. Lukaka and Dzeko being the target men with Martinez feeding off them as a second striker.

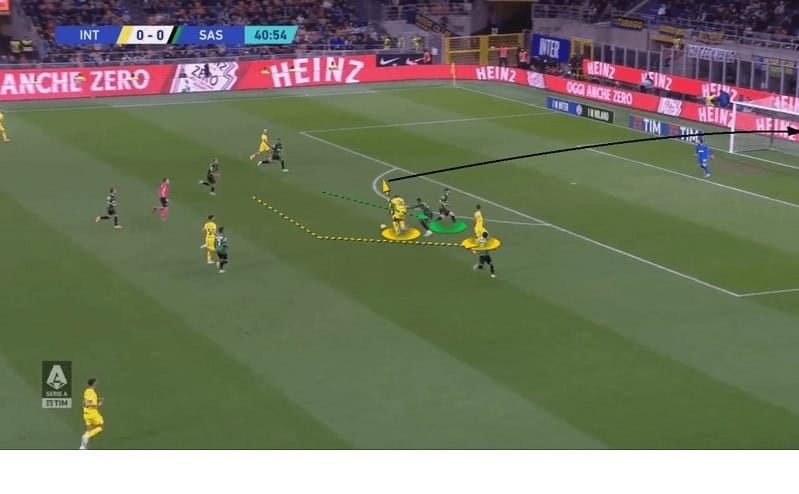

In this example, against Sassuolo, Lukaku is playing alongside Joaquin Correa on this occasion. Both Inter forwards are playing high, up against Sassuolo’s two centre-backs. Both centre-backs being occupied is something that modern centre-backs are not as used to dealing with, and, as in this example, struggle to defend against.

The image above shows the seconds after Inter’s most central centre-back received the ball from the left centre-back and played it into Lukaku’s feet. As the ball was travelling from one centre-back to the other, the two central midfielders split either side of the receiving player. The two midfielders showing for the ball brought the two nearest opposition midfielders with them. This opened up a passing lane into Lukaku’s feet.

Lukaku, instead of moving towards the ball, backed into his marker and lowered his centre of gravity. He also angled his body to receive on his back (left) foot, pinning his marker in place. This could have given him the opportunity to roll his marker and be through on goal.

As soon as the ball was on its way to the Belgian, Correa, playing as the second striker, made a run across the face. He then cut down the side of his strike partner towards the box.

Correa’s run dragged the ball-far centre-back all the way across the goal towards the ball. Lukaku’s marker, overcompensating to prevent himself from being rolled and to be positioned to intercept the potential pass to Correa, also shifted in that direction.

The reaction from the centre-backs plus their right-back being distracted by Inter’s high left wing-back created a huge opening at the edge of Sassuolo’s box. Lukaku, using Correa’s run as a decoy, twisted his hips and controlled the ball with the inside of his left foot towards this opening. He then, with his second touch, smashed the ball into the top corner of the net.

Movement for others

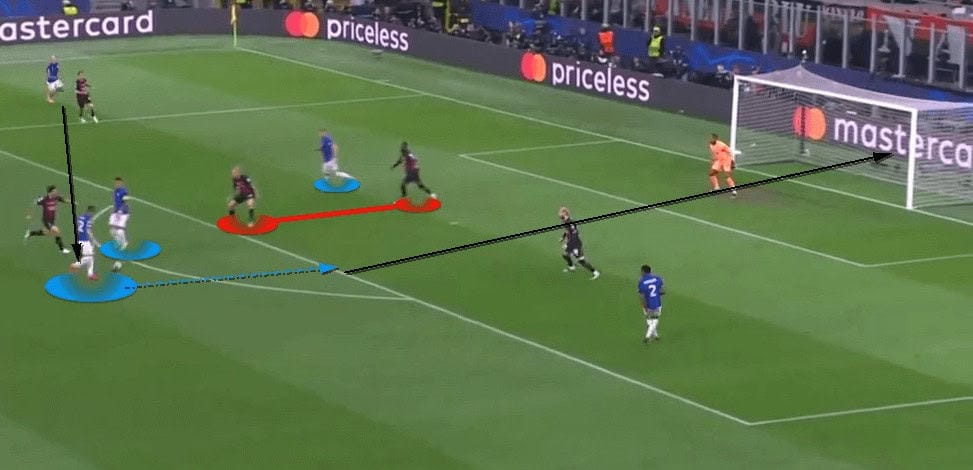

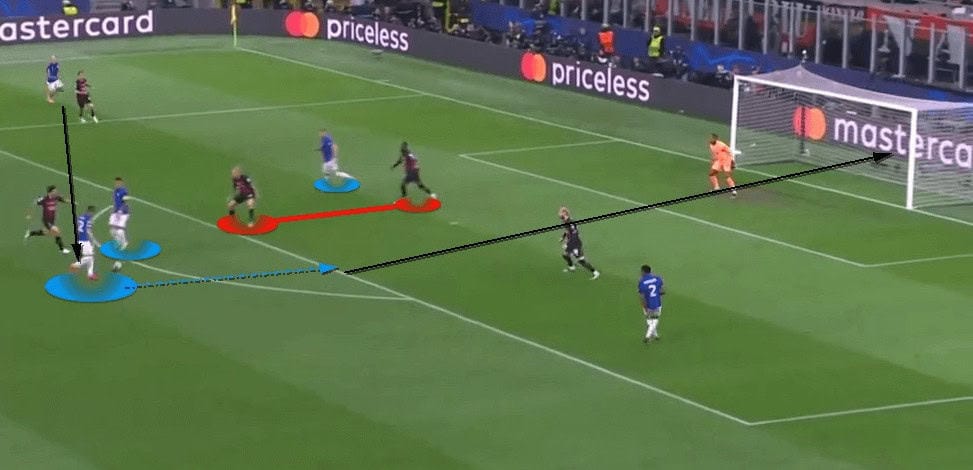

By having two forwards apply pressure to the centre-backs, their very presence can create chances for others without them even having to touch the ball. In this example, from Inter’s Champions League semi-final against AC Milan, the two forwards are occupying both centre-backs playing in a back four.

As the ball was played wide, both forwards made sprinting runs towards the goal. The initial benefit of this positioning, and then movement, is that it prevented the centre-backs from shifting to cover their full-back. This left Inters’ tricky wing-back, Federico Dimarco, in a one-on-one in the wide area.

It also pushed the defenders back towards their own goal. This created a gap in front of them for Inters attacking midfielders to run into. At the end of the move, it is this space that Henrikh Mkhitaryan exploits to run onto the ball and score.

As Dimarco reached the outside of AC Milan’s box, Džeko, the ball-far forward, ran across his striker partner towards the front post. Martinez made a slight movement towards the ball as it was crossed, before stepping over it. These runs meant that AC Milan’s centre-backs ended up in the same vertical line as one another.

This paved the way for Mkhitaryan to drive with and strike the ball with a clear sight of the goal. The forwards’ runs and presence make them a major factor in this goal without having touched the ball.

This image, from Cincinnati against Chicago Fire in the MLS, is another example of how the presence of two forwards can create opportunities for other players.

Here, the Chicago right-back has been drawn to Cincinnati’s left wing-back (highlighted) when he received the ball. As the wing-back received the ball, his ball-near forward dropped into the space to show for a pass into his feet. When this pass was played, the Chicago centre-back jumped to close him down. With the ball-far centre-back being occupied by the ball-far forward (highlighted at the top of the image), a huge gap was created between the centre-backs.

Cincinnati’s most advanced central midfielder accelerated to make a corner run between the centre-backs. The forward then fed through his advancing midfielder to put him in behind Chicago’s backline for him to set up their first goal of the match.

These counter-movements by the forwards are designed to pull centre-backs apart. Ideas for how to implement them are included in the coaching striker movement section.

Attacking Crosses

Crossing opportunities is another situation where it can be advantageous to have two forwards playing up-against against two centre-backs. With both players occupied, one cannot attack the cross whilst the other one sweeps behind. It also means their full-backs, often smaller than their central teammates, can be isolated for high balls to the back area.

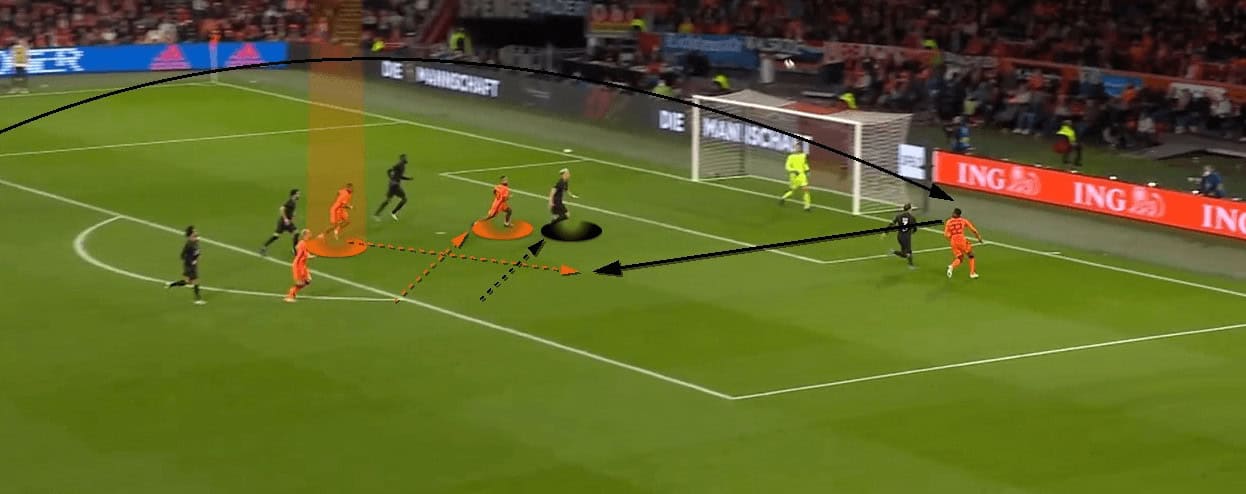

The above image shows one such scenario with the Netherlands about to cross from the half-space towards the back area.

When movements are made just as the ball is about to (or is seemingly about to) be delivered, opposition defenders have little choice but to follow their marks. This can be a method to clear the way for another player or to isolate a teammate one-on-one with a defender.

The above image shows Netherlands’ Memphis Depay just after making a diagonal run towards the front post as his teammate was about to cross the ball. Due to the timing of his movements, the centre-back tracked his run. This created a one-on-one aerial duel between Germany’s left-back and the Netherlands’ right-wingback, Denzel Dumfries.

With the left-back tucking in slightly to cover his centre-backs, Dumfries, who already has a height advantage, can get a run on him. Because of this, the left-back was unable to position himself to disrupt Dumfries’ run and jump. Dumfries made the most of his aerial mismatch to win the header and put it back across goal.

The header was aimed into the space created by the Germany left centre-back being dragged across the goal. Steven Bergwijn then cut into the front half of the second 6-yard box to meet the knockdown and volley past Manuel Neuer.

Coaching striker movement

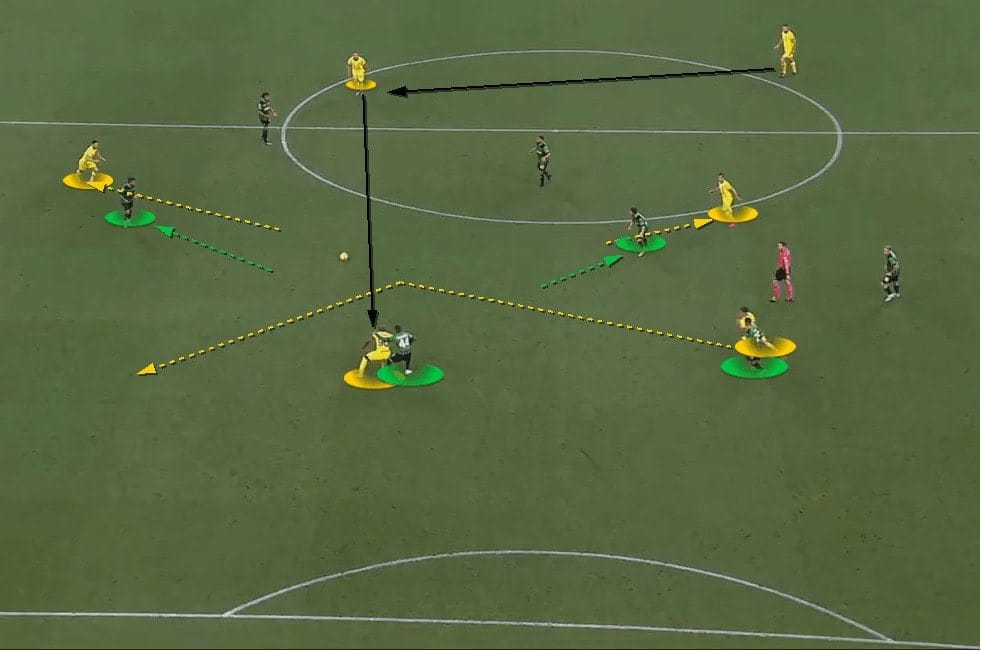

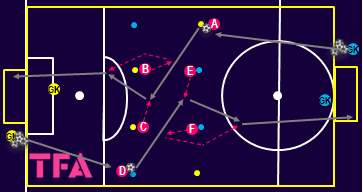

This shooting pattern is designed to work on runs, counter-movements and the body orientation of central-forwards playing in a front two. It aims to teach players how to create separation between opposition centre-backs and exploit the spaces that appear. It will also work on the forwards’ hold-up play and finishing.

The exercise works towards two goals with the balls starting in the half-spaces and being played into either forward. The forwards complete a pre-determined combination before shooting at the goal. After each shot, the players rotate A to B to C and so on.

Players C and E move to the next set to shoot at the opposite goal. If numbers allow, spare goalkeepers or coaches can feed the balls into players A and D. This makes the practice more game-like with forwards having to better time their movements. Two players can also be added to each of the cones representing a forward. This will aid in the intensity of the exercise and provides the opportunity to add in shadow and/or full defenders. These defenders represent centre-backs in a back four.

The forward’s starting point is just slightly wider than the width of the goal, around 10 yards. This distance allows them to be close enough to combine. In the pattern shown in the above diagram, the first forward’s run should be long enough that it moves the first defender. This is to make sure separation between opposition centre-backs is achieved.

After a certain amount of rotations, the starting points can be adapted (see empty blue and yellow cones) for the initial pass to be coming from the opposite side.

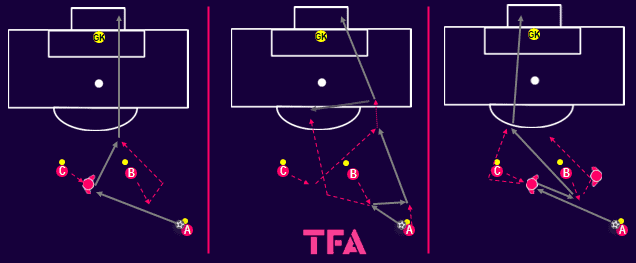

The above image shows examples of the movements and combinations the two forwards can make.

Sequence one has the first forward (the forward closest to the ball), make an angled run towards the ball, bringing the first centre-back with him. The first pass misses out Player B, who spins to the outside. Player C receives side-on, just as Lukaku in the first section of the analysis, and plays a through ball to B with his front (right) foot.

Sequence two has both forwards making the same initial movement as in the previous sequence. This time, however, it is the first striker that receives the ball. He plays a bounce pass with A before spinning and making a looping run around his strike partner. Player C makes a run behind player B before receiving a through ball from A. If the pass into the second striker does not allow a good shooting angle, player B can be an option for a cutback.

Sequence three has player C receive the ball and play a first-time pass to player B. Player B, who turns to face C as the ball travels past him, then plays a through ball to C. C has laid the ball back to B and spun to the outside to run inside onto the ball.

Players should be coached to spin the opposite way from the direction of the ball whilst keeping the body orientated towards it. This allowed them to not take their eyes off the ball. This movement also keeps them on the blind side of the defenders.

When receiving a through ball, they should be encouraged to time their runs to avoid being offside. If the through ball is delayed, forwards can remain on-side by backtracking wider, rather than stopping or halting their runs.

Crossing and finishing

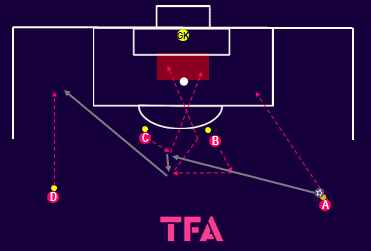

This crossing and finishing exercise is a progression from the previous drill and is designed to incorporate the same striker movements. The two forwards combine before switching the play and attacking the box to get on the end of a cross. The previous exercise is modified slightly, with the first pass coming from the wide area, to transform it into a crossing and finishing sequence.

The two players in the wide areas represent wingers playing in a 3-5-2. As in the finishing exercise, the play starts with player B moving towards the ball. B is missed out by Player A who plays a drilled pass, fast enough to not risk being intercepted, into the feet of Player C. Player B, then runs across the face of C who lays the ball straight back whilst screening it. B then plays the ball into the wide area for D to run onto.

As the ball is played wide, the two forwards should move away from the ball before attacking the box. This helps isolate the winger in a one-on-one with the opposition full-back. It also makes their movements more difficult to track as it is harder for the defending player to see the ball and their mark at the same time.

As the forwards attack the box, they cross over each other before splitting the second six-yard box in two. One attacks the front area and one the back. The winger who played the first pass into the striker can become the third player in the box and attack the back far-side of the 18-yard box.

The exercise can be replicated on the opposite side.

Conclusion

One major benefit of playing with three at the back is that it allows teams to play with two upfront without sacrificing a central midfield player. Teams, especially those that play with two centre-backs, are often unable to cope playing against two forwards. The task is all the harder when one of those has a big physical profile of the likes of Lukaku.

Two forwards playing close together allows them to combine and pull centre-backs into areas they do not want to go. When centre-backs jump with them, this can leave space for either the forwards or a supporting player to exploit. This may be a tactic more and more coaches begin returning to.

Comments