If you’ve followed the Total Football Analysis La Liga Podcast, you might recall this question: “Is there any place for the dark arts in the age of VAR?”

As a practitioner of the dark arts in my younger days, I was stunned by this question. Can you have football without gamesmanship? That’s like having hockey without a goon or basketball without the dribble/drive guard who gets 60% of his points from the free throw line.

Between that question, the season Sergio Ramos had and all the controversy surrounding VAR, it seemed like the right time for this tactical theory article.

In this tactical analysis, we’ll investigate the underhanded tactics at play in the age of VAR. Gamesmanship is not dead, but it has certainly evolved, mostly out of necessity. Our topics are tactical fouls and rotating fouls, discovering the “where” of yellow card offences, finding our modern enforcer, usage of screens and looking at the impact of simulation.

Tactical fouls and rotating fouls

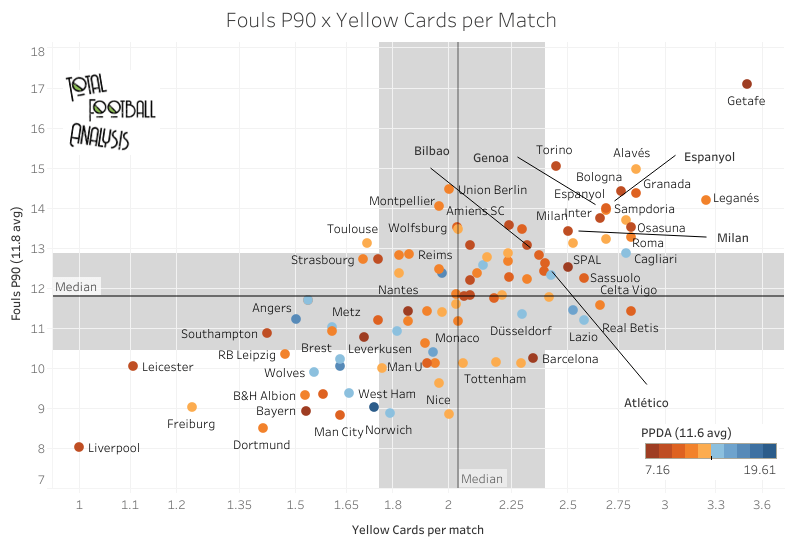

To determine how clubs use and value tactical fouls, the first task is to find the sides that most heavily rely on this dark art and if there is a trend in the data. Going into the data analysis, the working theory was that clubs with high foul frequencies and a high number of yellow cards on a per match basis would rate either near the top (foul well) or bottom (foul poorly and often) of the table or have a distinctive possession-based attacking philosophy.

The rationale behind the latter theory is that possession-based clubs, often committing numbers forward to counterattack the opponent’s low block, would rely on tactical fouls as a means of denying counterattacking opportunities.

In addition to those extremes and the possession-based attacking teams, clubs with a top PPDA (passes per defensive action) scores would feature in the list. This includes teams with direct and indirect attacking styles. Covering La Liga for Total Football Analysis, I knew Getafe would rate highly in nearly every dark arts metric. Their high pressing, narrow defending, direct attacking style meant opponents struggled to beat the press and contain Getafe’s numbers near the ball. When opponents did find an outlet, Getafe was quick to close the window with a clattering challenge.

Sure enough, Getafe are the stars of our first chart, fouls P90 x yellow cards per match + PPDA. Leaders in fouls and yellow cards P90, they also rate among the best pressing sides in Europe’s top five leagues.

This chart, just like the one after it, features every club from Europe’s top five leagues. All statistics are from the 2019/20 campaign, so I’ve filtered the results on a per 90 basis to account for the variance in games played.

Beyond our outlier, we find a mixed bag in that upper right quadrant. In fact, if there’s any notable correlation, it’s that the teams keeping Getafe company were mostly either battling for European play or fighting relegation. Very few of those sides were middle of the table type teams.

Interestingly, Liverpool, Bayern Munich, Manchester City and a number of other top clubs are in the lower left quadrant, meaning they commit fewer fouls and pick up fewer yellow cards than the rest of the sample. Among the teams in this quarter of the chart, you’ll find that they either have exceptional rest defences or leak goals like an uncapped fire hydrant.

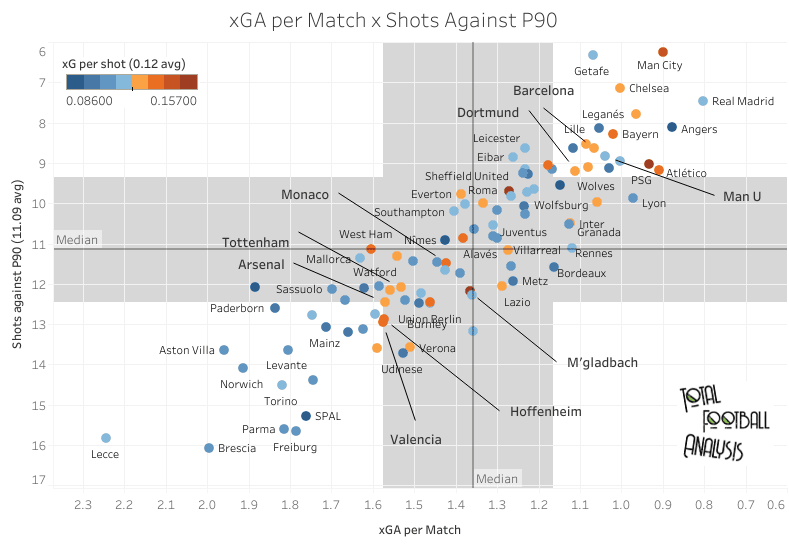

The next metrics considered are xGA per match x shots against P90 + xG per shot. This chart gives a really nice few of the elite defensive teams. With a few exceptions, that upper right quadrant features the top clubs across the Big 5.

In addition to identifying top defensive sides and seeing if any clubs made a second appearance in the top right quadrant, we also wanted to identify which sides needed tactical fouls most. Identifying these clubs is helped by our colour variants.

Clubs with a deep blue point hold their opponents to low xG per shot averages, which means they typically concede low-quality shooting opportunities. The burnt orange end of our scale highlights teams that give the opponents more high-quality chances.

Of note, Manchester City, which fell in the few fouls and yellow cards portion of the previous chart, typically conceded higher quality scoring opportunities to opponents than Real Madrid and Getafe.

Meanwhile, a side like Norwich City had few fouls and yellow cards, allowed a high xGA and shots against, high xGA per shot and too few points to avoid relegation.

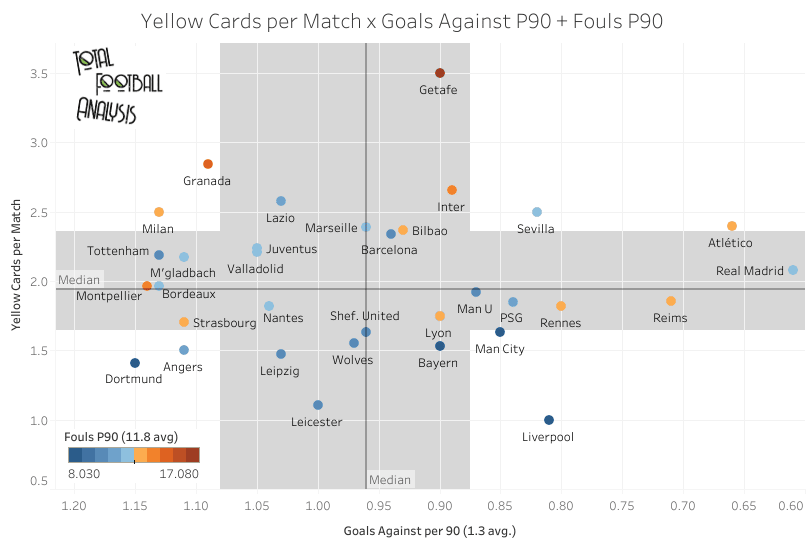

Thus far, our investigation has mostly provided an idea of which teams use tactical fouls and high foul frequency in practice, as well as those who, in theory, should foul more frequently. Refining the spotlight even further, I filtered for clubs with a goals against P90 of 1.15 or less. The average among the greater dataset was 1.3 goals allowed P90, so we’re filtering out the underachievers to focus on the teams that foul well.

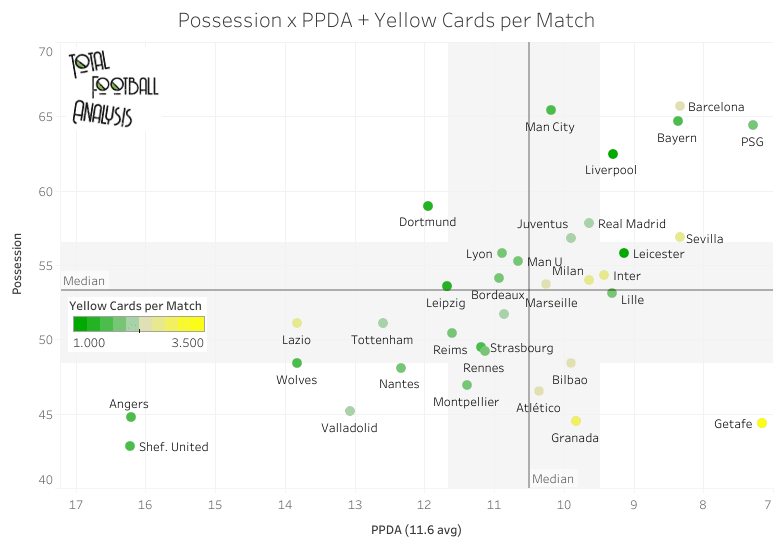

Sticking with the theory that possession-based attacking clubs near the top of the table will have a relatively high foul frequency and yellow card accumulation, the next graph shows possession x PPDA + yellow cards per match. We want to determine which possession-based attacking clubs and high PPDA sides earn a high number of yellow cards.

As expected, the super clubs rule the top right quadrant. Barcelona, Sevilla and Inter Milan are the notables in the category. Not only are they in the top right quadrant, but they’re also sides with high yellow card accumulation.

Getafe and Granada are fascinating studies as well. If Jürgen Klopp’s Dortmund sides were the heavy metal band of the footballing world, José Bordalás’ Getafe are the guys in the mosh pit body-slamming each other on tables and smashing chairs over each other’s backs. They epitomise old-school, direct play. Their Spanish counterparts, Granada, qualified for the Europa League in their first season back in La Liga. With each team operating on a tight budget, their hard-nosed, tactically savvy use of the dark arts propelled them to success.

The final side I’ll highlight is Lazio. The Italian side, once the dark horse to end Juventus’ monopoly over Serie A, is the top-performing side in the bottom left quadrant. Even despite their tendency to sit a little deeper and split possession, they still racked up a high number of yellow cards.

Finally, we have yellow cards per match x GA P90 + fouls P90. The goal here is to identify which clubs excel defensively while utilising tactical fouls and high foul frequency.

For sides that rate highly in yellow cards and fouls yet still maintain a strong goals against P90 average, like Getafe, Granada and Inter Milan, those foul totals require rotating fouls, a reliable resource for the clubs that dabble in the dark arts. In order to avoid high foul totals for a single player, the players will take turns cutting down the opponent. It’s an effective way to sustain the playing philosophy while safeguarding the players from yellow cards for foul accumulation.

Elsewhere, we again see Lazio, Sevilla and Barcelona with low foul totals but high yellow card accumulation. Sevilla commits the fewest fouls of the three and owned the best goals against P90 average.

Where do savvy teams commit tactical fouls?

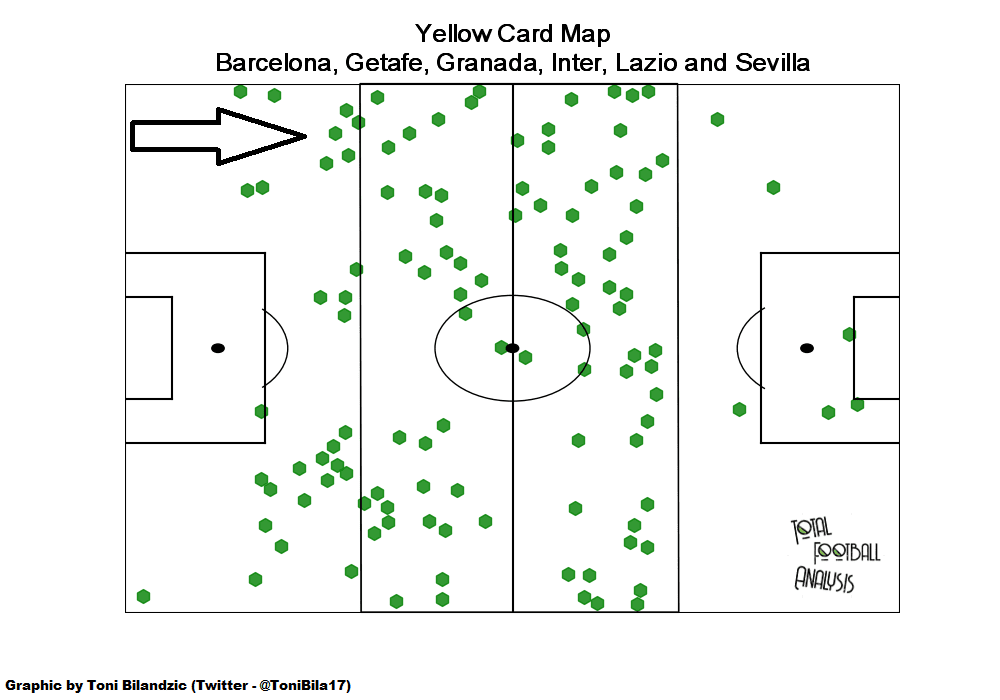

With these six clubs standing out, I decided to plot the locations of their yellow card infractions. Since each club ranks among the leaders in yellow cards and offers excellent defensive statistics, the goal was to see if any trends emerged in event locations.

The above event map reveals the locations of yellow cards from the 2019/20 campaign. Studying the data, five matches per side, each with high yellow card accumulation, were plotted. Getafe and Sevilla picked up a bonus match for producing high yellow card performances from Granada and Barcelona, respectively. Breaking the yellow card offences down by pitch thirds, the result is 29-82-5. 25% of yellow card offences came in the defensive third, 71% in the middle third and just 4% in the attacking third.

One interesting detail to note is the lack of yellow card offences in zones 14 and 17 (before and in the box). When the sides resorted to yellow card offences near their goal, the tendency was to do the deed in the wings.

So, why the tendency to foul in the middle third?

In many cases, the card was issued after a tactical foul. With the first line or two of the press broken, the teams committed the foul before the opponent could break another line or enter into a shooting position.

One of the reasons for the high number of yellow cards in the wings and half spaces is that counterattacking teams frequently targeted the space behind the outside-backs. That left the centre-backs or centre-mids moving away from the side’s defensive structure to defend in the wide areas. If the odds of a recovery were against them, a foul in a non-threatening position eliminated the more pressing threat.

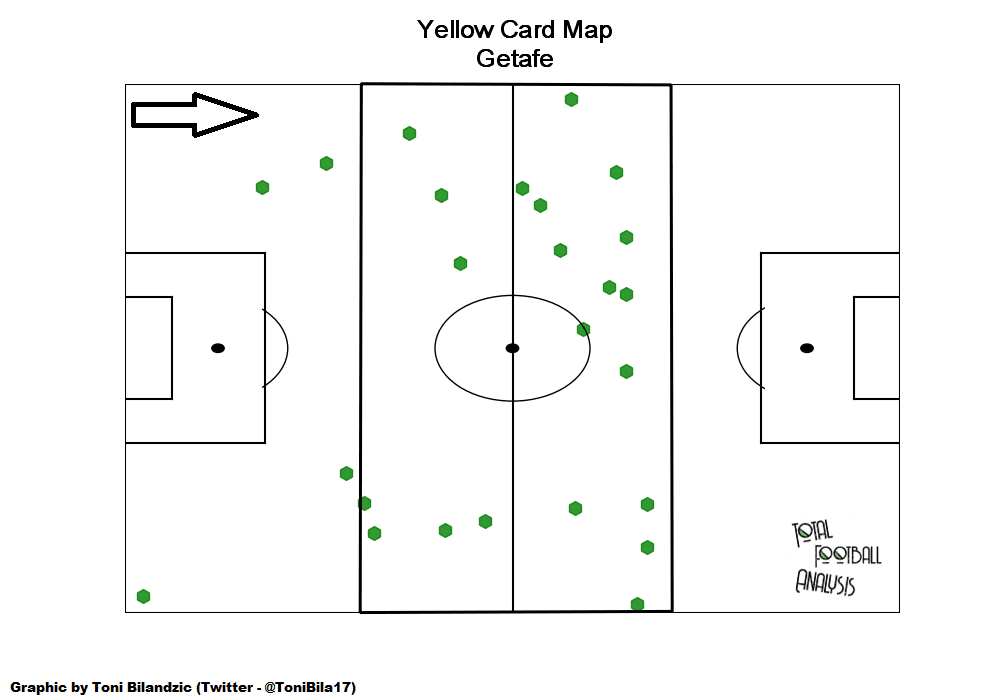

Our final image highlights Getafe. Until the COVID-19 suspension of play, they were contending for UEFA Champions League spots, sitting in 5th. With one of the lowest salaries in La Liga, this side was a purveyor of the dark arts. Their highly direct approach, both in attack and defence, meant any lost duel could cripple the defence. Rather than taking that risk, fouls, and hard ones at that, were the answer. Of the 25 yellow card offences in those six matches, 21 (84%) came in the middle third. With just 0.9 goals against P90 and 6.33 shots allowed P90, you had to take the few chances afforded to you, because the masters of the dark arts wouldn’t give you many more.

The Enforcer

Speaking of enforcers in the age of VAR seems like a misnomer. Compared to the bone-crushing tackles of decades past, being an enforcer in today’s game is like being the alpha puppy in the litter, more of a cute role than a terrifying one.

Fewer Gennaro “Rino” Gattusos, Vinny Joneses and Nigel De Jongs exist in today’s game, which has certainly lengthened careers. Even though fewer enforcers exist in today’s high-tempo, attacking football, the role will never die off. Rather, it will adapt to the new constraints, taking on a less malicious form, moving more towards pragmatic, disguised aggression.

While researching this analysis, I came across the research paper of Emily Zitek and Alexander H. Jordan entitled. “Anger, Aggression, and Athletics: Technical Fouls Predict Performance Outcomes in the NBA.” In this study, the researchers concluded that aggression took two modes, instrumental and hostile. The former serves the purpose of the big picture, winning the game, whereas the latter is more reactive and a response to a perceived threat rooted in a high-arousal state.

Before VAR, the referee crew’s eyes were the only resources for interpretation. Now, with the application of VAR, acts of hostile aggression are reduced simply because there’s no hiding them.

However, one thing the study notes is that the middle and long-term impact of hostile aggression is negative as the high-arousal state impairs judgement and performance. Rather than helping, it’s actually a distraction from the task at hand. As the study notes, even instrumental can detract from the performance of high-level tasks where precision is critical. That said, instrumental aggression is a common trait in elite performers. In the context of basketball, that results in more points scored, rebounds and blocks. In football, defensive excellence, 1v1 dribbling and spatial orientation are some key performance indicators.

Instrumental aggression seems like the best categorisation of the modern enforcer. Rather than a brute, he’s an intelligent player with the ability to quickly access risk. The greater the threat, the more likely he is to foul. When forced into a fouling situation, you’ll still see him sending a message with hard contact, but it’s measured to protect himself from red cards.

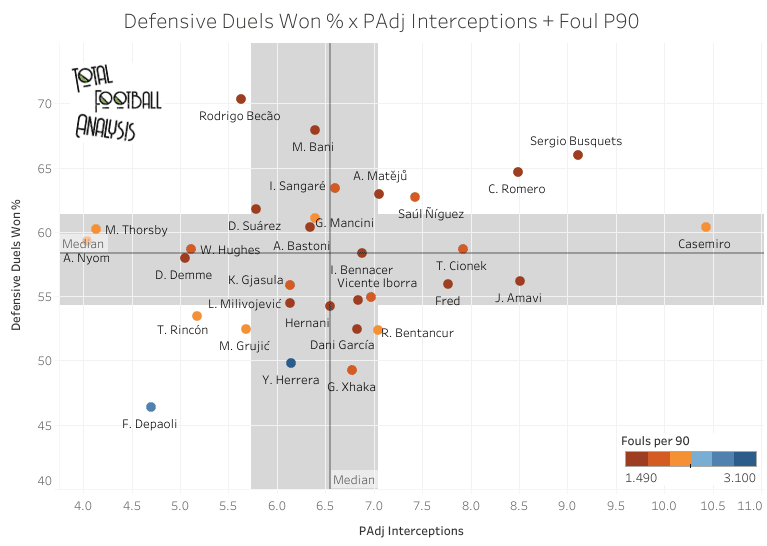

Our chart below searches for the top enforcers from the 2019/20 season. To narrow the dataset, a 2000 minute minimum was set, as well as a minimum of 1.49 fouls P90 and 0.3 yellow cards P90. The aggressive standards eliminated players like Sergio Ramos, mostly because centre-backs simply can’t afford to commit many fouls per game and Ramos prefers a different colour, but he’ll make an appearance soon enough. The goal is to identify which enforcers also offer a strong defensive contribution.

Right away, Casemiro stands out. He hits all the boxes, commanding the midfield and offering hard, counterattacking killing fouls whenever necessary. Sergio Busquets might surprise some, but the Spaniard’s biggest issue at Barcelona is that he’s simply asked to cover too much ground in a really poor rest defence. When he’s not scrambling across the width of the pitch, his defensive work is still reasonably good, he just doesn’t have much support in front of him.

Cristian Romero, the 22-year-old Argentine who plays for Genoa, is another top defensive player among our enforcer class with a 64.69% defensive duel win rate and 8.49 possession adjusted interceptions P90. Saúl Ñíguez and Aleš Matějů of Brescia round out the top defensive performers among the class, implying that their fouls and yellow card accumulation are not the result of sloppy defensive work, but, rather, necessities to deny threats.

On the bottom left quadrant, we have the lower end of the defensive performers. Fabio Depaoli of Sampdoria is in a league of his own, but in the wrong way. Yangel Herrera, the Manchester City player who spent the season at Granada, performed poorly in defensive duels and PAdj Interceptions while setting the standard in fouls. These two, as well as the others in the lower left quadrant, are prone to sloppy defensive work, using fouls as a means of bailing themselves out of trouble as much as intelligently helping the team.

Turning our attention to the top enforcers of recent years, we’ll turn the spotlight on concrete examples courtesy of Casemiro, Ramos and Pepe (Giorgio Chiellini and Luis Suárez will suffice as honourable mentions).

In the image below, Casemiro offers an example of both the intelligent tactical foul (instrumental aggression) and hard contact (hostile aggression) to rattle the opponent. Going back to the academic article from Zitek and Jordan, hostile aggression points to a high-arousal state. That aggressive mindset helps the individual maintain higher levels of energy and performance, especially in tasks requiring forceful energy.

That’s the exact scenario Casemiro and his Real Madrid teammates were in at that moment. Without the need to push forward and score, the psychological and physical boost offered by the hard foul assisted Casemiro in seeing out the 2-1 win. Given the stage of the game, that hard foul through the back of Rony Lopes doesn’t offer Sevilla any long-term benefit, especially if it disrupts the flow of the match and allows Real Madrid to defend from a position of strength. Since the need for precision in technical execution is lower at this stage in the match, hostile aggression, even combining it with a tactical foul, is beneficial to the individual as he helps his team see out the waning minutes of the match.

An additional aspect to consider is the emotive state of the opposition. Against sides with a greater inclination for unrestrained emotional displays, a combination of instrumental and hostile aggression produced can distract the opponent from the needs of the present.

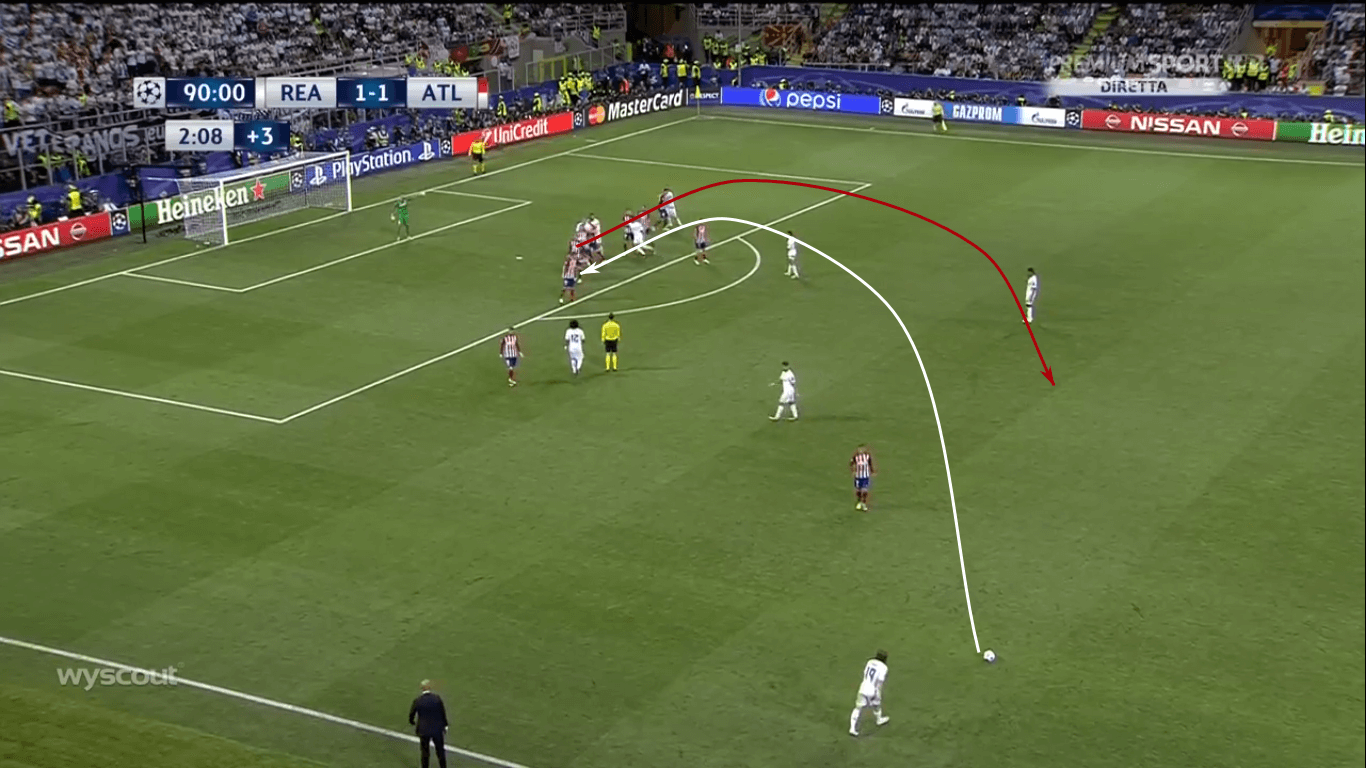

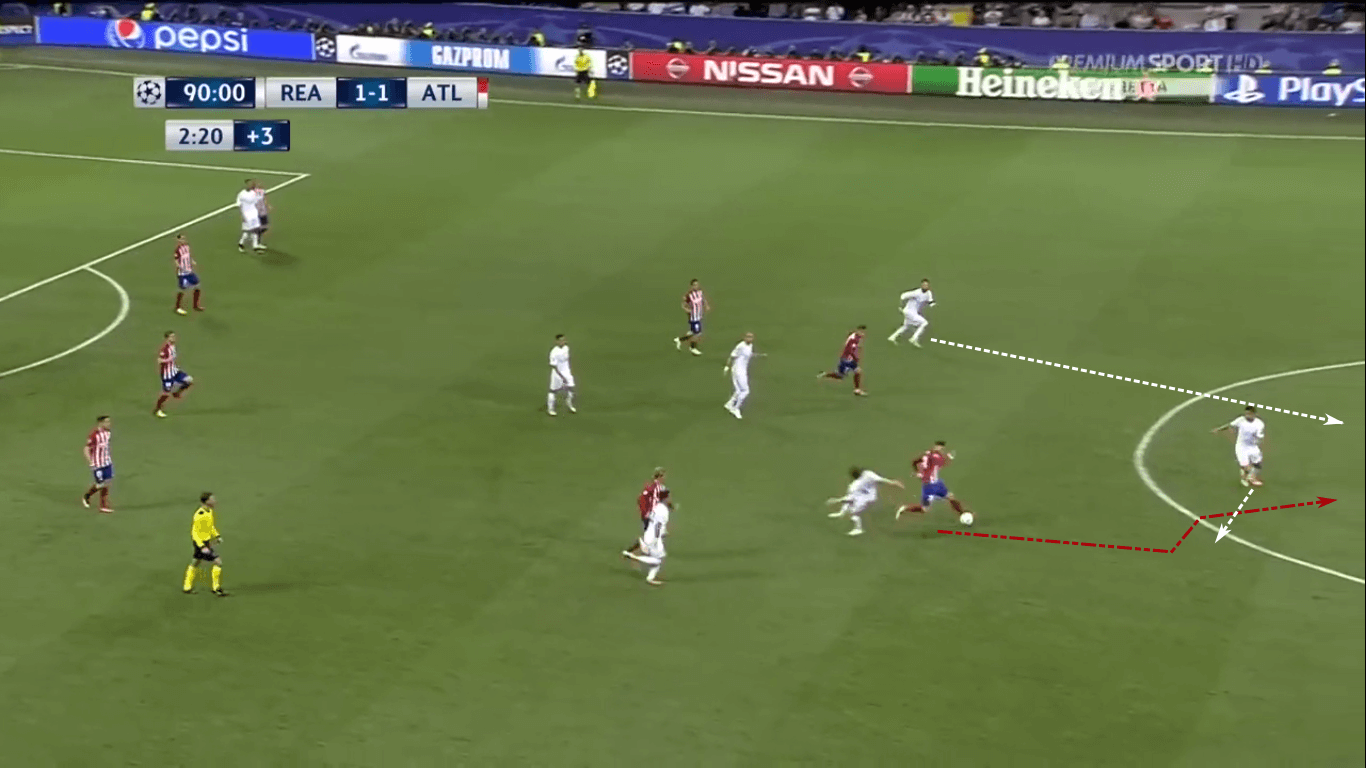

Take the 2015/16 UEFA Champions League final as an example. In the final minute, Real Madrid had a free kick against Atlético Madrid. Luka Modrić lined up for the set piece, but his delivery was cleared.

Pepe jumps to head the ball back into the Atléti box, but Yannick Carrasco recovers the ball with numbers moving forward. Carrasco dribbled past Modrić’s attempted tackle, skipped past Casemiro and had only Danilo in front of him past Atléti teammates to his left and right.

That’s when Ramos’ recovery run put him in a position to save the game. Rather than allow Carrasco to run at Danilo, Ramos did his duty, bringing down the Belgian before he could release the ball, killing the attack and earning a yellow card as his medal of honour. The scissor tackle was both dangerous and highly tactical, but the location of the tackle and, we’ll say, close proximity to the ball led to a yellow rather than a straight red.

Simeone’s men played extraordinarily well that day. La Liga champions two years prior, these sides represented peak Atlético. They were dangerous going forward, especially when Real Madrid pushed numbers higher in pursuit of the winner.

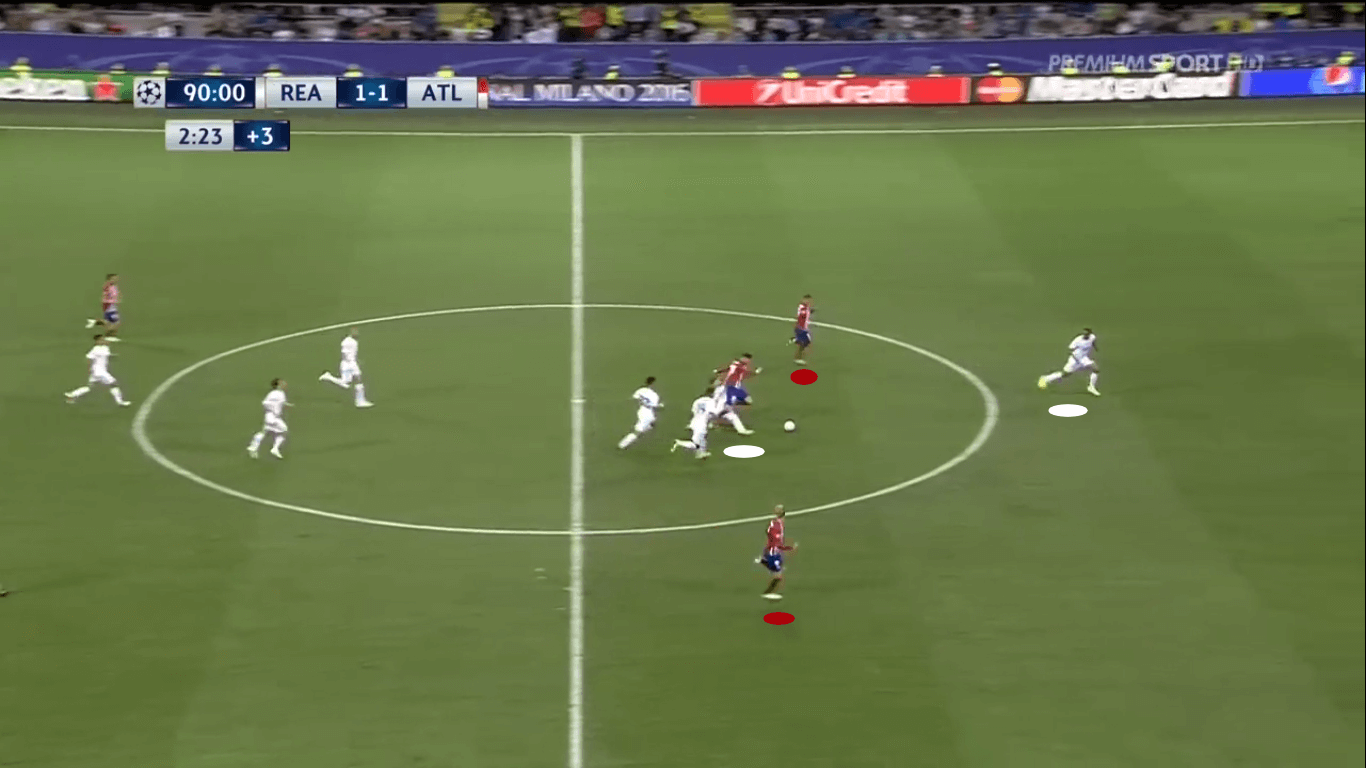

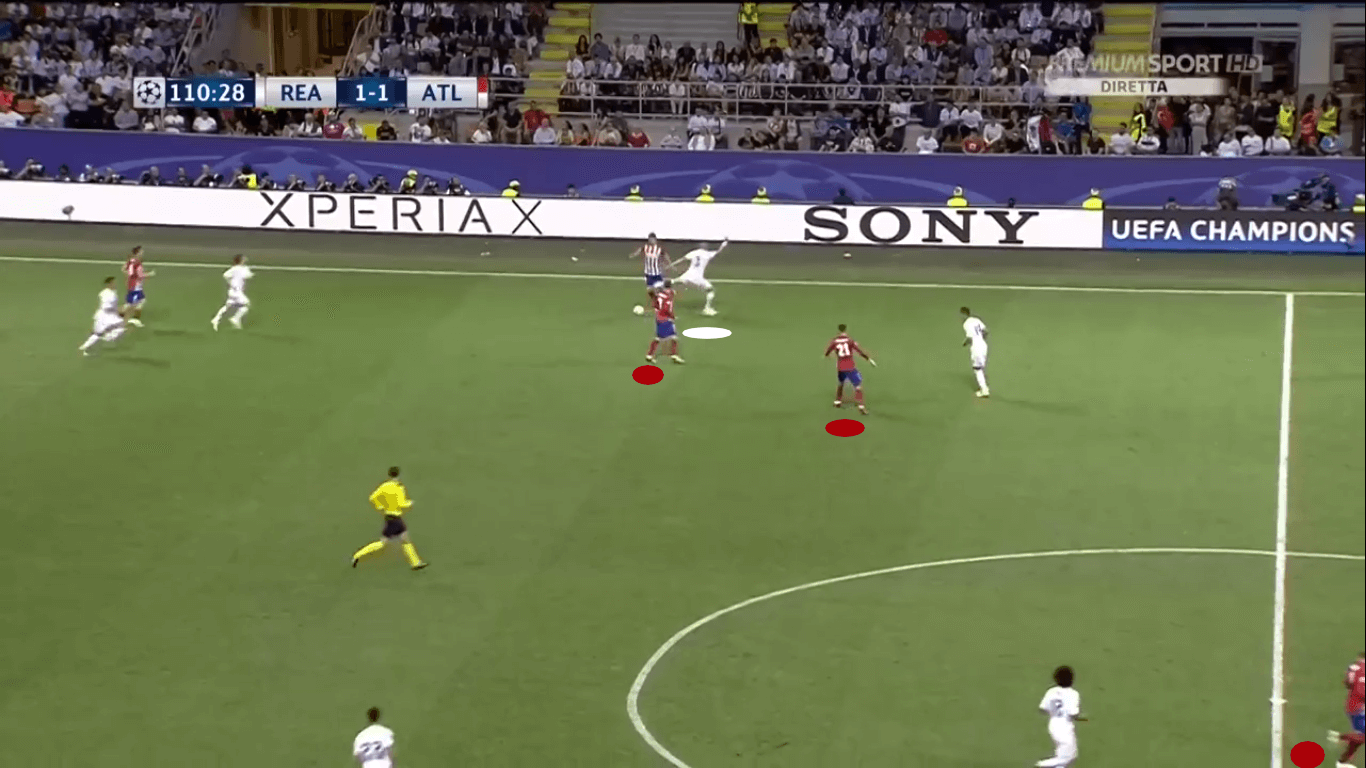

In the 110th minute, Real Madrid was again caught going forward. This time, it was the other of the Twins of Tactical Terror hacking Gabi at the knees. With Real Madrid disorganised and Atlético shifting into a higher gear, Pepe sacrificed himself and committed the tackle foul, though something tells me he wasn’t particularly bothered by it.

Though some tackles give the impression of recklessness, and Ramos does at times cross the line, the modern enforcer is more measured in the tackle. Take Pepe as an example. Ask the common football fan how many red cards Pepe has picked up in his career and you’ll likely hear a Ramos-esque number. However, according to WhoScored, Pepe only has four red cards in his career. He’s a brilliant example of instrumental aggression in an enforcer in today’s game.

Screens

This is one of the more contentious dark arts, especially since it’s generally in response to shirt-tugging, bear-hugging defenders, but screens are in fact one of the dark arts. Technically illegal, screens are means of acting on the person rather than the ball.

Set pieces are the clearest example of screens in football. Attacking teams will often look to spring one of their top aerial threats by screening the path of the defender, allowing the attacker to move to his desired location more freely. You’ll generally see screens near the penalty spot.

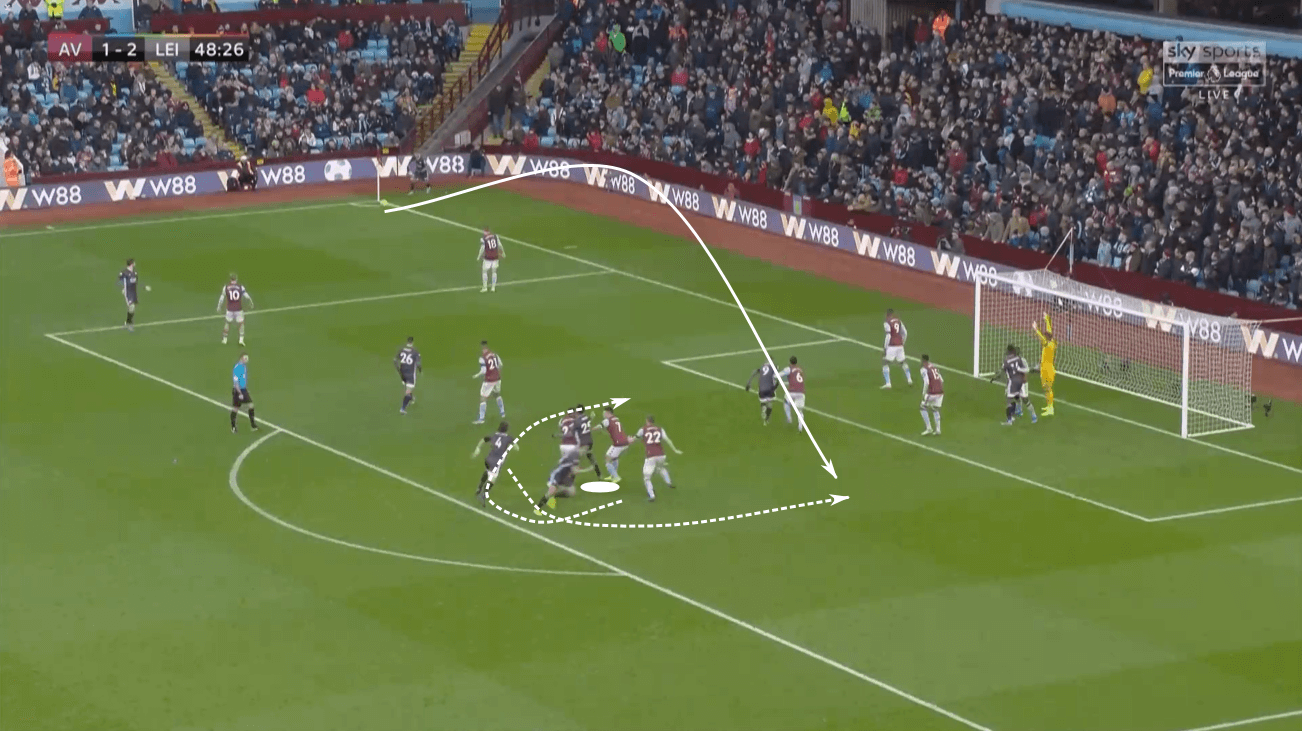

In the example below, Leicester City is taking a corner kick from the goalkeeper’s right side. A man on the keeper screens him from the centre of the box, making it difficult for him to collect the in-swinging corner. More importantly, you’ll notice the activity at the penalty spot.

Leicester City’s corner routine is designed to leave Jonny Evans in space, freeing him to make the back post run. Wilfred Ndidi sets the screen, then Çağlar Söyüncü and Evans run around him. If Evan’s mark had gotten around Ndidi’s screen, Söyüncü’s run would have fully dismarked Evans. The result was a powerful, far post header from the Northern Irishman, helping Leicester to a 4-1 victory.

Set pieces are common sources of screens, but they occur during open play too. From an attacking perspective, overloads allow players to cut into the path of an opponent, springing a teammate free. The referee is occasionally used as well.

However, the best example from open play is a defender who’s either running towards his own goal or trapped near the perimeter. Dangling that little bit of hope in front of the attacker, prodding him to sprint forward or lunge for the poke tackle, as an incredibly reliable means of earning a foul or allowing a teammate to clean up.

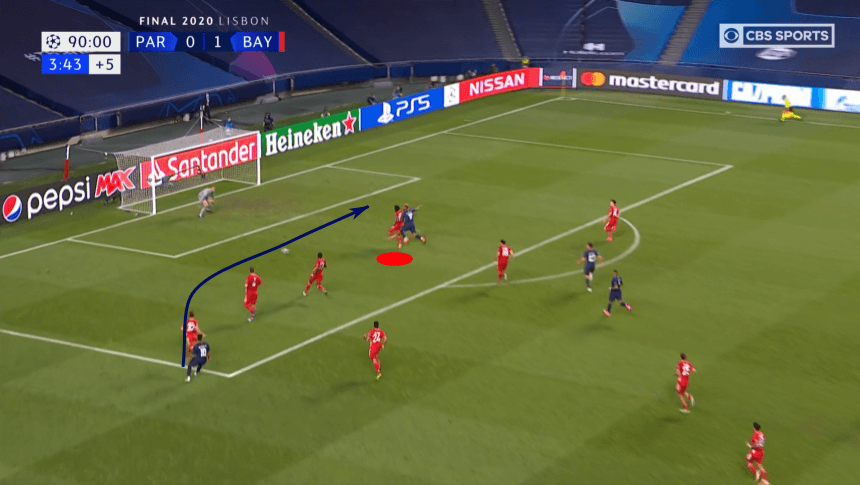

In the UEFA Champions League final, we saw a great example of this from the young Canadian, Alphonso Davies. Neymar picked out the run of Eric Maxim Choupo-Moting in the centre of the box. Alert to the run, Davies not only tracked his runner, but gained positioning and obstructed his movement forward.

You can say that this is simply great defence from Davies, and it is, but that element of screening, deliberately obstructing the progress of an opponent while acting primarily upon the opponent rather than playing the ball, is still an application of the dark arts.

Simulation and initiating contact

In a season that featured 14 penalty kicks for Manchester United, 15 penalty kick goals for Lazio and 152 Serie A penalty kick goals on 187 attempts, red flags are waving. With the strict enforcement of the hand ball rule, a combination of clever flicks, simulation and unrelenting officiating saw the number of penalty kick goals skyrocket.

Another area impacted by simulation is zone 14. Just beyond the box, this zone is a hot spot for simulation. Clubs with great direct kick takers can afford to play more centrally, looking to either slip a runner into the box or draw contact to get the foul.

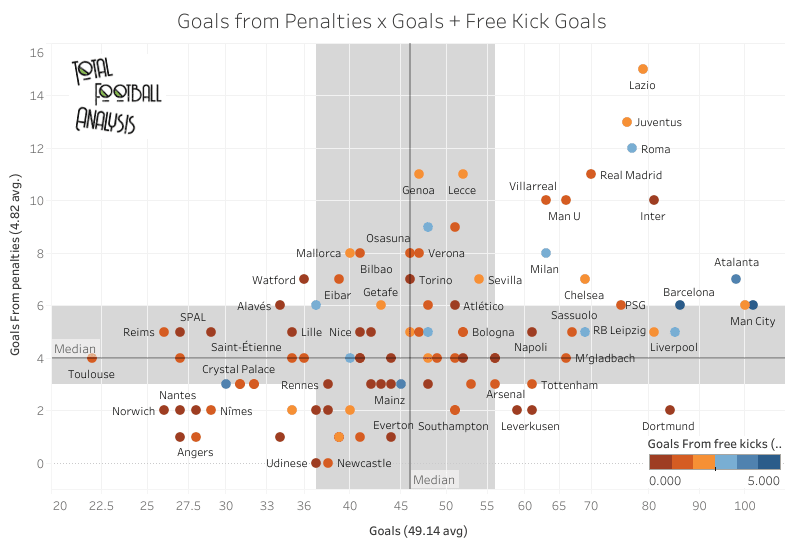

Which teams benefited most in 2019/20? The below chart shows goals from goals from penalty kicks x goals + direct kicks goals.

Lazio was the clear winner in the penalty kick goals category. Behind them were two other Serie A powers, Juventus and Roma. In fact, with the exception of Real Madrid, Villarreal and Manchester United, the top beneficiaries play in Serie A. In terms of free kick goals, Barcelona and Manchester City set the standard.

While the current interpretation of the handling rule, as well as VAR backed reviews, have led to an increase in penalty kicks, it’s the direct kicks we’ll focus on. After all, it’s pretty obvious how and why teams simulate contact to earn a penalty kick, but it’s not as clear for direct kicks.

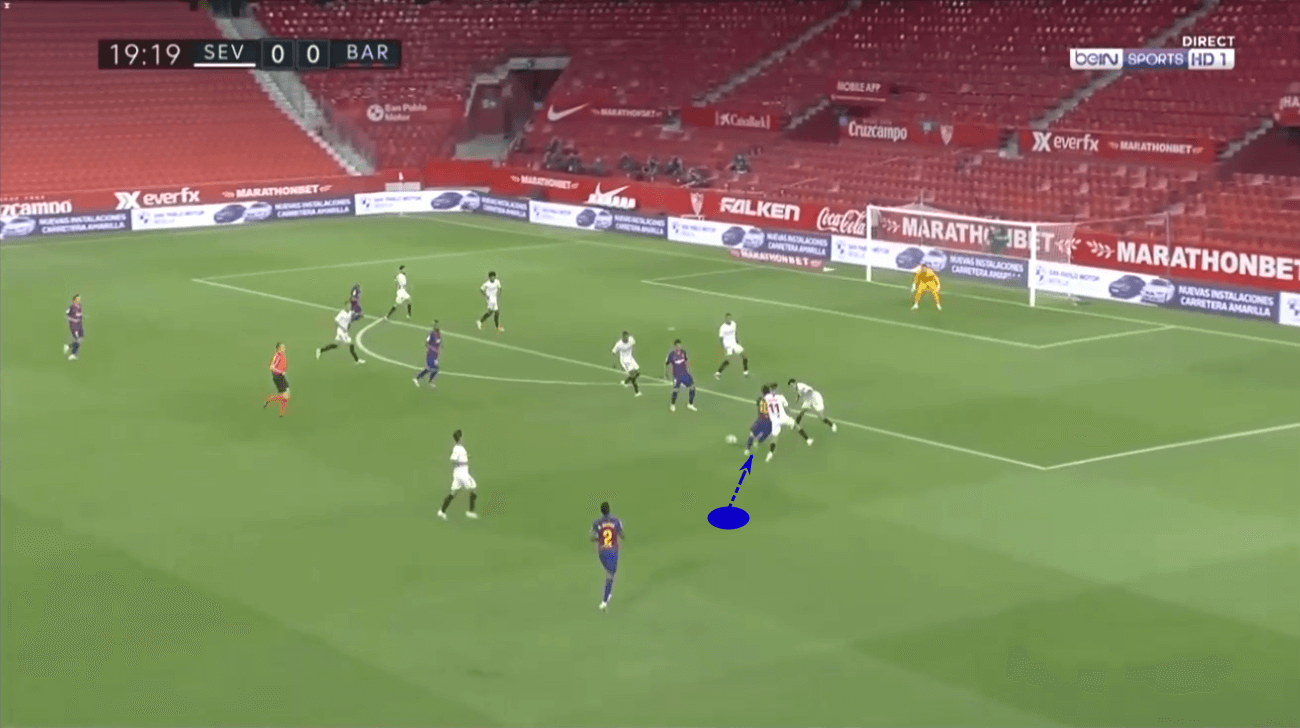

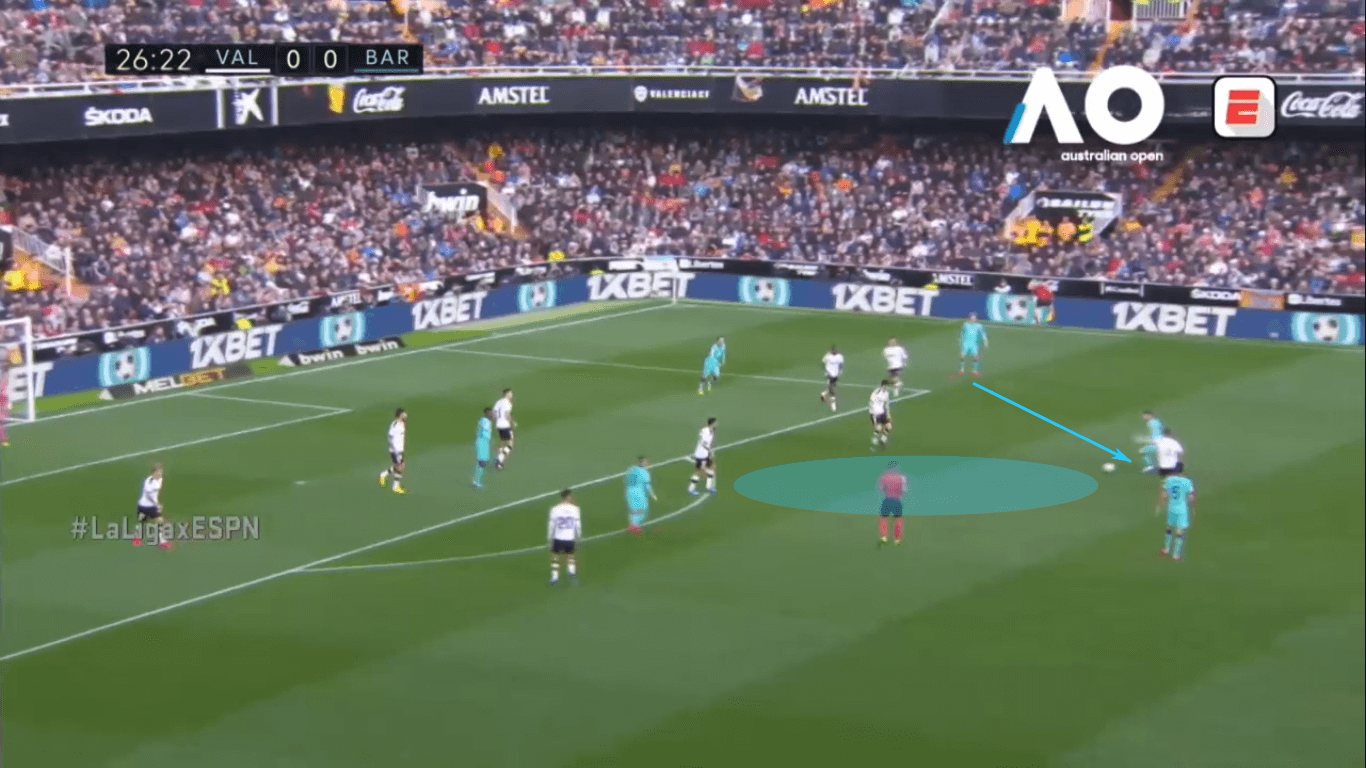

Take the image below as an example. We’ve already seen that Barcelona led Europe’s Big 5 in direct kick goals and we know how lethal Lionel Messi is within 30 yards. A tactical trend that sticks out is Barcelona’s use of Messi just outside of his free kick range. With Messi able to receive in that area, he can then drive forward into the opposition’s numbers. Though he’s not as quick as he used to be, he’s still quick enough in tight spaces to force contact and earn a foul.

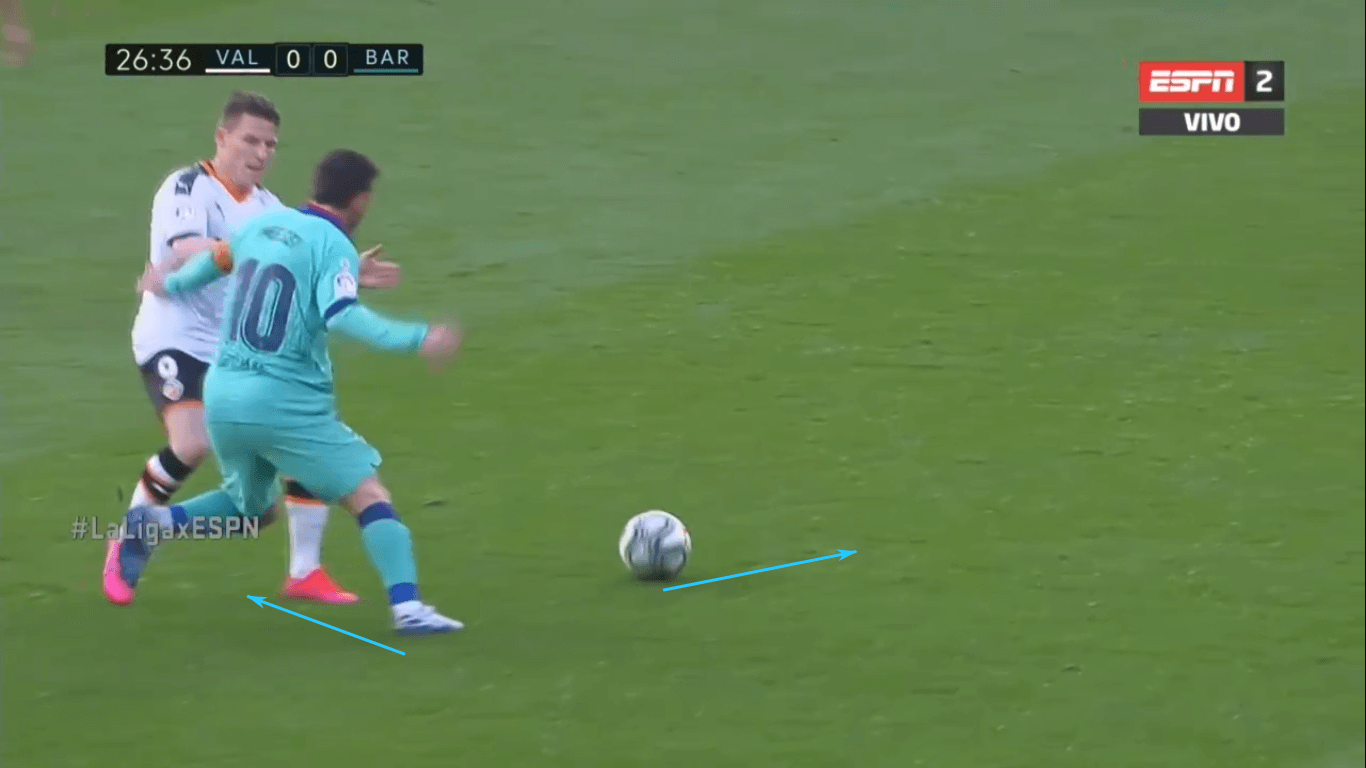

The sequence below is even more indicative of the dark arts at work. As the ball is played back to Messi, he has a clear running lane forward, but a conservative touch doesn’t take him into the space.

Instead, Messi literally jumps into Kevin Gameiro to draw the foul. It was so obvious that both players could only smirk at the absurdity of the action. The below image shows Gameiro decelerating while Messi’s weight is on his right foot, which is launching him into Gameiro.

Fortunately for Valencia, Messi didn’t convert the direct kick, but the manner in which Messi forced contact and simulated the extent of it offers another insight into how players can escape the authority of VAR to gain an advantage.

Conclusion

VAR has changed the way players conduct themselves, even impacting the types of challenges delivered and a team’s play in or near the box. Frustration with the video review system lingers, but the players and coaches don’t have time to complain. Rather, they’re adapting to the new conditions.

The topics addressed are not new to the game, nor is this an exhaustive list, but the way these tactics are implemented by the players and coaches has certainly evolved from previous generations. With VAR catching more deviant actions, the degree of hostile aggression has decreased, but rule changes have never stopped clever players and coaches.

So, as we move further into this age of VAR, I not only confirm that the dark arts are alive and well, but also that they’re not going anywhere. You’ll find the dark arts at play wherever there’s a competitor desperately seeking out a minuscule advantage, a coach looking to keep his job or a player trying to earn a contract extension. Trends come and go, but the dark arts fall beyond that realm. They’re subtle means of gaining an upper-hand.

So long as we have this beautiful game, the dark arts will have a place.

Comments