Throughout its historical development, football has seen its tactical evolution driven by struggles, akin to the adage of a fighter who is inspired by the very struggle.

In the past decade, Pep Guardiola, one of the most influential coaches on the planet, has undergone significant changes, adapting his approach to his opponents.

His journey in Spain differed from his time in Germany and it is entirely distinct from his current endeavours in England where his path has evolved from its inception to its culmination.

While football has undoubtedly advanced technically, the question remains: does the present state signify true tactical development? Some have drawn parallels between one of Guardiola’s new variations, the 31213 (as seen in the UFEA Champions League final vs Inter Milan), the same as Johan Cruyff once elucidated on a television program in The Netherlands more than a decade ago.

Regardless of past or novelty, everyone seeks superiority through diverse means.

Desires vary, whether it’s attaining midfield dominance or exploiting the flanks, with each approach influenced by the techniques and qualities of individuals.

Two of the most prominent forms that are always used are the diamond and box midfield shapes.

The centrality of the two lies in positioning players centrally in various ways to gain the positional advantage of the spaces closest to the goal while dealing with the flanks differently.

However, the final configuration of these formations can vary extensively based on the players’ specific characteristics.

In some way, football is undergoing a transformation that goes beyond mere formations in midfield, focusing instead on the roles and responsibilities of players to shape the overall structure which enables participants to be more versatile and well-equipped to adapt to various situations.

In this tactical theory, we journey into the tactics of the diamond, its variations, and interchangeability with the box-midfield as well as explore some of their strengths, weaknesses, and the ways in which coaches shape the dynamics.

Both can be adjusted to suit the strengths of the team and exploit the vulnerabilities of the opponent and coaches have the flexibility to tailor the diamond and box-midfield variations which we illustrate throughout the piece.

Diamond

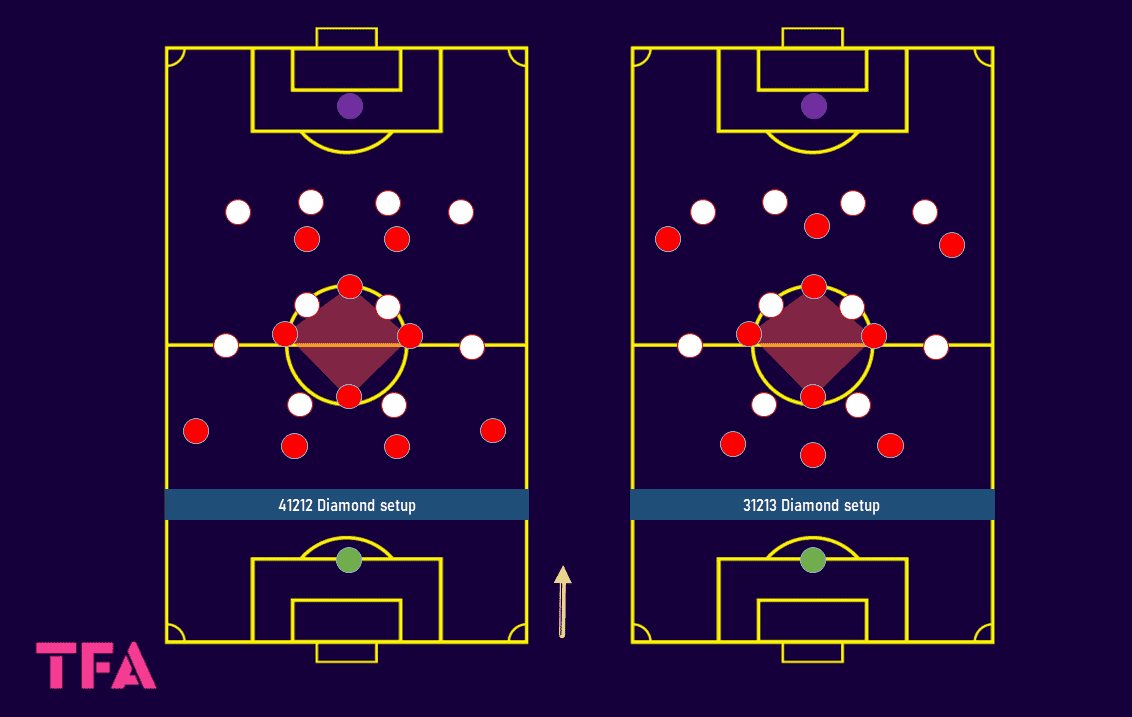

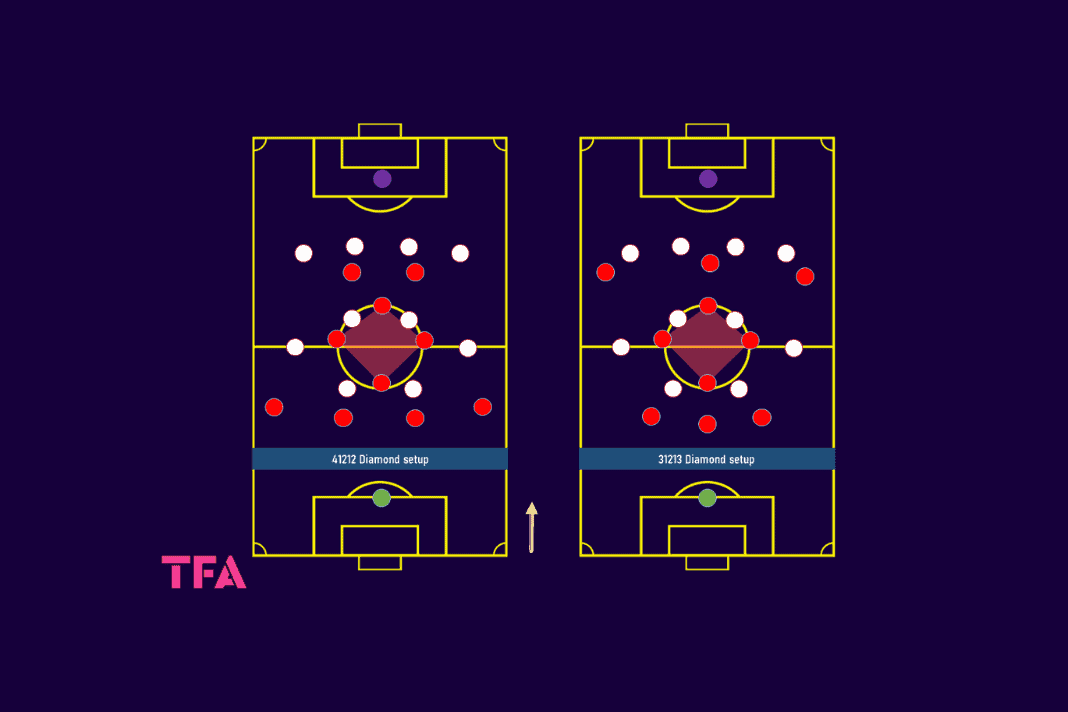

The renowned diamond setup is 4-1-2-1-2 or 4-3-1-2 which involves positioning the midfielders in a diamond and features a flat four-man backline, and two forwards up front, while the diamond is created by the defensive midfielder, double 8s, and the attacking midfielder.

Certainly, this provides a numerical advantage in the middle of the pitch, potentially giving positional superiority over the opponent’s two or three midfielders.

However, it is worth noting that this concentrated central setup sacrifices presence on the wings.

This presence can vary, sometimes lower with fullbacks in 4-1-2-1-2 or higher with wingers in 3-1-2-1-3.

The latter (3-1-2-1-3) utilises a three-man backline, sacrificing the full-backs and one striker in order to have two wingers positioned higher up on the flanks while the diamond in the midfield is maintained.

The utilisation of the diamond can vary based on the players’ roles and the coaches’ strategies.

Typically, teams rely on a No.

6, who can be either a deep-lying playmaker (regista) responsible for retention and distribution or a defensive midfielder who shields and protects the play.

This role sure is reflected in the duo of central midfielders who cover a whole lot of ground and may function as box-to-box players (e.g., Paul Pogba with Juventus) or defensive No.

8s tasked with supporting the deep-lying playmaker (e.g., Gattuso with Pirlo in Carlo Ancelotti’s 4-1-2-1-2 with Milan).

Furthermore, the presence of the No.

10 positioned higher in this narrow setup allows for freedom of movement both longitudinally and laterally, depending on the immediate situation.

This player can either be a traditional playmaker or can take advantage of the spaces created by the movements of the front two forwards (e.g., Dele Alli in Mauricio Pochettino’s 4-1-2-1-2 with Tottenham Hotspur).

Due to this central narrow and compact nature of the diamond, there is inevitably a lack of width.

Naturally, the diamond is susceptible to defensive vulnerabilities against wide attacks.

Opponents can exploit the spaces left by the full-backs or overload against the isolated full-back.

Additionally, there is a risk of being exposed to counterattacks when the team is focused on overloading the central areas and attempting to fill the wide areas simultaneously.

Some variations of the diamond

In 4-1-2-1-2, the lack of width is particularly evident higher on the flanks.

To address this, teams often rely on overlapping fullbacks who push higher up the pitch, stretching the width to exploit the wide areas dynamically.

The compactness of the central diamond also tends to draw opponents towards the centre which opens the spaces.

However, this demanding and exhausting role of the fullbacks leaves significant space behind them, which can be exploited during transitions.

This vulnerability is considered a major weakness of this variation.

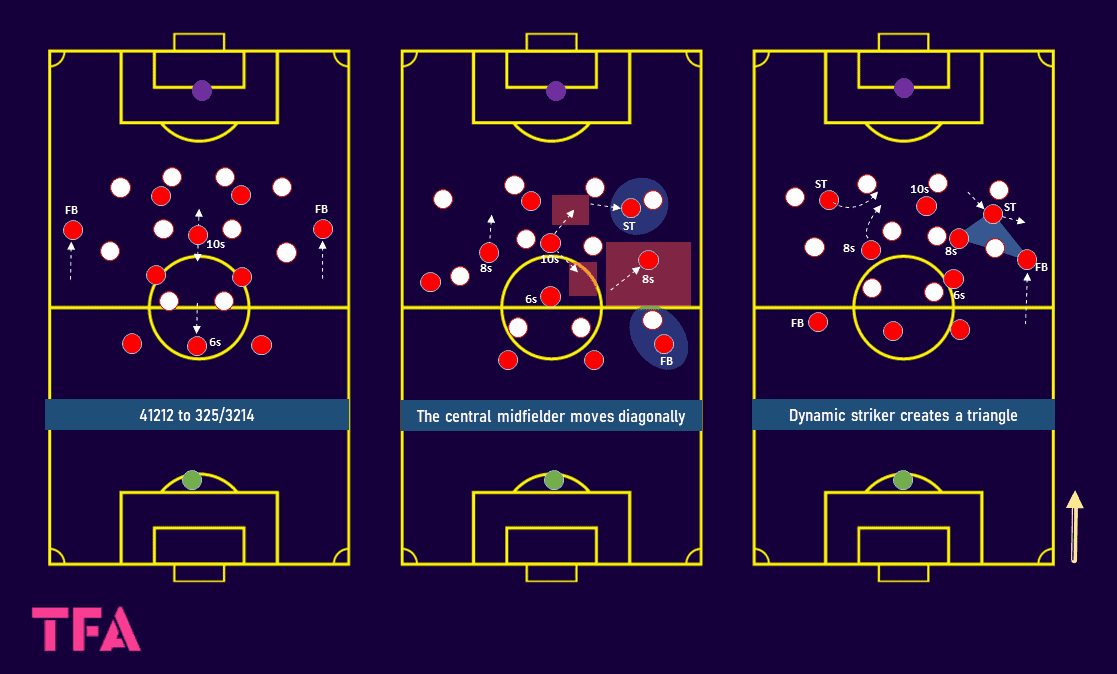

Consequently, many teams opt to transform from the 4-1-2-1-2 diamond to 3-2-1-4 or 3-2-5 like in the below graphic, as the defensive midfielder drops between the centre-backs to progress the attack and cover the exposed spaces on the sides (known as “La Salida Laviolpiana”, originally from Mexico).

Another variation and dynamic which varies, as mentioned, based on players’ characteristics and coaches’ styles, involves a different approach.

In this case, instead of the fullbacks pushing higher up immediately, the nearest central midfielder moves diagonally to exploit the spaces on the sides.

Simultaneously, the opposition’s wingers move forward to press, and sometimes the nearest striker drifts to pin the opponent’s fullback.

Here, the No.

10 is ready to strategically exploit the space generated thanks to his positional advantage, either by dropping to the generated space from the central midfielder who moved diagonally or going up to the front line to exploit the space generated by the drifting striker.

Additionally, in this dynamic, the reverse No.

8 is also prepared to make vertical movements to provide a +1 in the front line.

In another variation below, synchronisation and positional rotations play a crucial role.

In this setup, the two strikers (or at least the one closest to the ball) should have the mobility to position initially into the half-space.

The striker initiates the movement toward the flank, the full-back overlaps and pushes forward and the nearest No.

8 moves to form the triangle while the reverse No.

8 is prepared to join the frontline (e.g, Manchester United, when they played the 4-1-2-1-2 diamond structure under Ole Gunnar Solskjaer and Marcus Rashford and Anthony Martial were the mobile strikers).

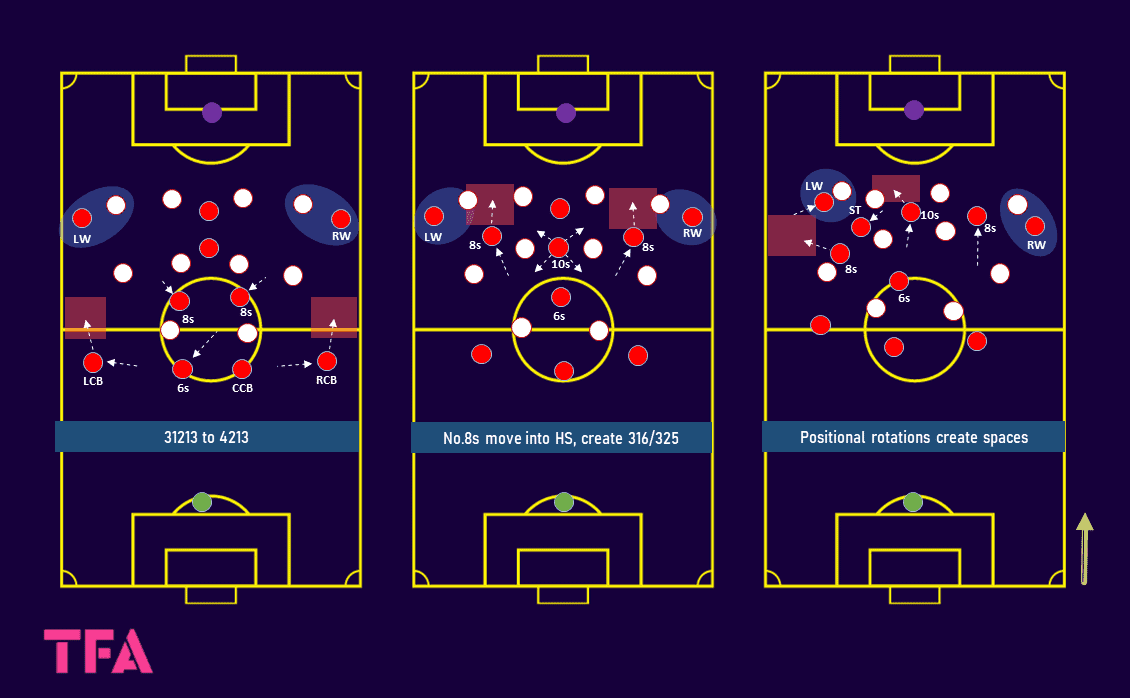

In 3-1-2-1-3, the flanks are occupied by wingers who position higher up the pitch, stretching the width.

To effectively execute this structure, it is advantageous to have mobile-wide centre-backs that possess the ability to contribute and attack the side, similar to full-backs.

In the first variation below, the No.

6 drops deeper to form a four-backline, allowing the wide centre-backs to move wider.

Meanwhile, both wingers pin the opposition’s full-backs, preventing them from venturing forward.

Also, sometimes the wingers themselves may drop off to receive in those spaces.

The initial positioning of the players is crucial.

The diamond shape and the density in the central areas draw the opposing team inward, and then the empty wide spaces are exploited.

In the second variation, the emphasis is on exploiting the half-spaces where the attacking No.

8s aim to occupy those spaces horizontally.

This creates a dilemma for the opposition’s fullbacks who must decide whether to stay outside with the winger (leaving the half-space exposed) or defend inside (leaving the wing empty).

In this setup, the movements of the No.

10 can vary depending on the situation.

He has the flexibility to move downwards, dropping deeper to add a +1 in midfield or moving upwards to exploit spaces there.

In the final variation, the reliance here is on positional rotations.

The winger moves diagonally inward to draw the attention of the opposing full-back.

At the same time, No.

8 makes a diagonal movement outward to exploit the vacant space.

Furthermore, the striker drops off to combine into that generated space.

Meanwhile, the No.

10 moves towards the last line, aiming to exploit the gaps.

Interchangeability between the diamond and box-midfield

The interchangeability between the diamond and box midfield serves as a means to enhance flexibility, create confusion, and gain numerical or positional superiority at specific points.

The transition from the initial point to another requires multiple immediate answers from the direct opponent.

It is possible to create interchangeability with fluid movement from the box where the triangle or the square is sketched in the middle to the shape of a diamond and vice versa.

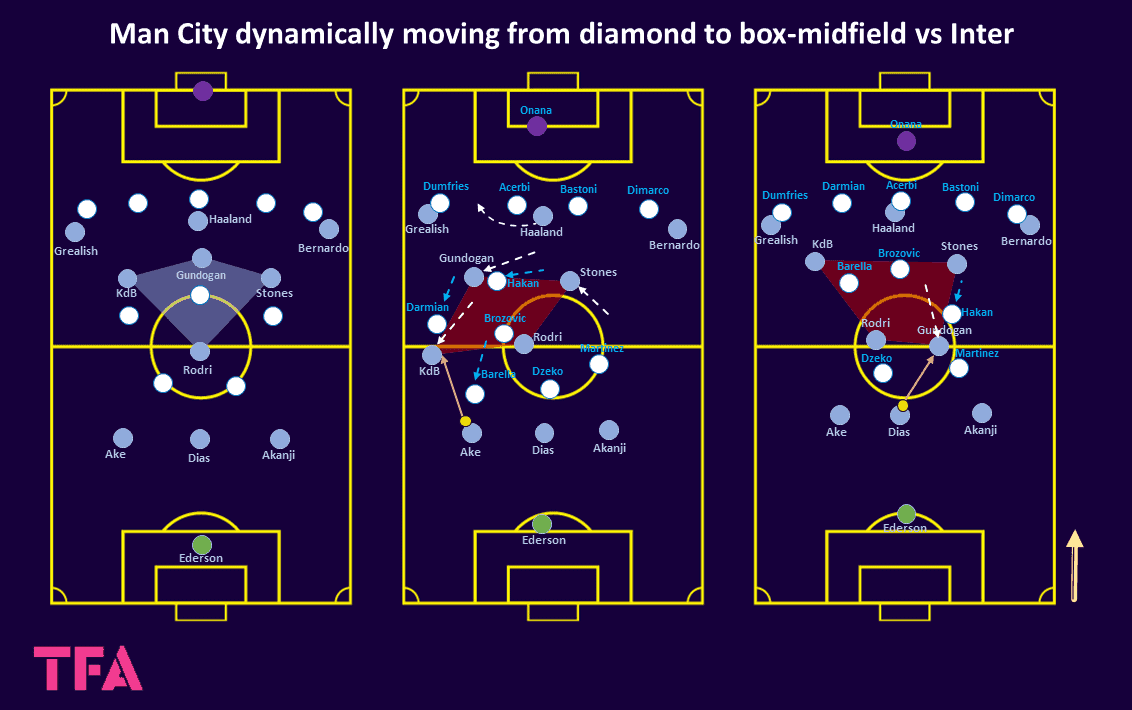

One of the most significant matches during Guardiola’s era at Manchester City was the UEFA Champions League final against Inter Milan.

In this match, Pep, who had been favouring the box midfield shape (3-2-2-3) recently, decided to switch to a 3-1-2-1-3 with a midfield setup closer to a diamond to adapt to Inter Milan’s defensive structure (5-3-2).

Pep relied mainly on this interchangeability where Man City transformed dynamically from the diamond shape to the box-midfield in different ways.

In the graphic, Kevin De Bruyne (No.

8) drops off, aligning with Rodri (No.

6), to receive a pass from Nathan Aké.

At the same time, İlkay Gündoğan moves towards the left, and Stones slightly advances to create the box midfield.

However, this positioning frequently left the farthest No.

8 ( John Stones) free in an advanced position.

In this particular scene, the left centre-back Matteo Darmian tracks De Bruyne.

As a result, this opens up a gap for Erling Haaland to exploit.

Additionally, Jack Grealish plays a role in pinning Denzel Dumfries higher.

In another variation of the transformation from diamond to box, Gundogan drops off vertically alongside Rodri, essentially luring one of Inter Milan’s midfielders to come out and press him.

This attitude is not only adding +1 deeper but is also intentional provocation which creates space for one of Cityzens’ No.

8s to become free higher in the box.

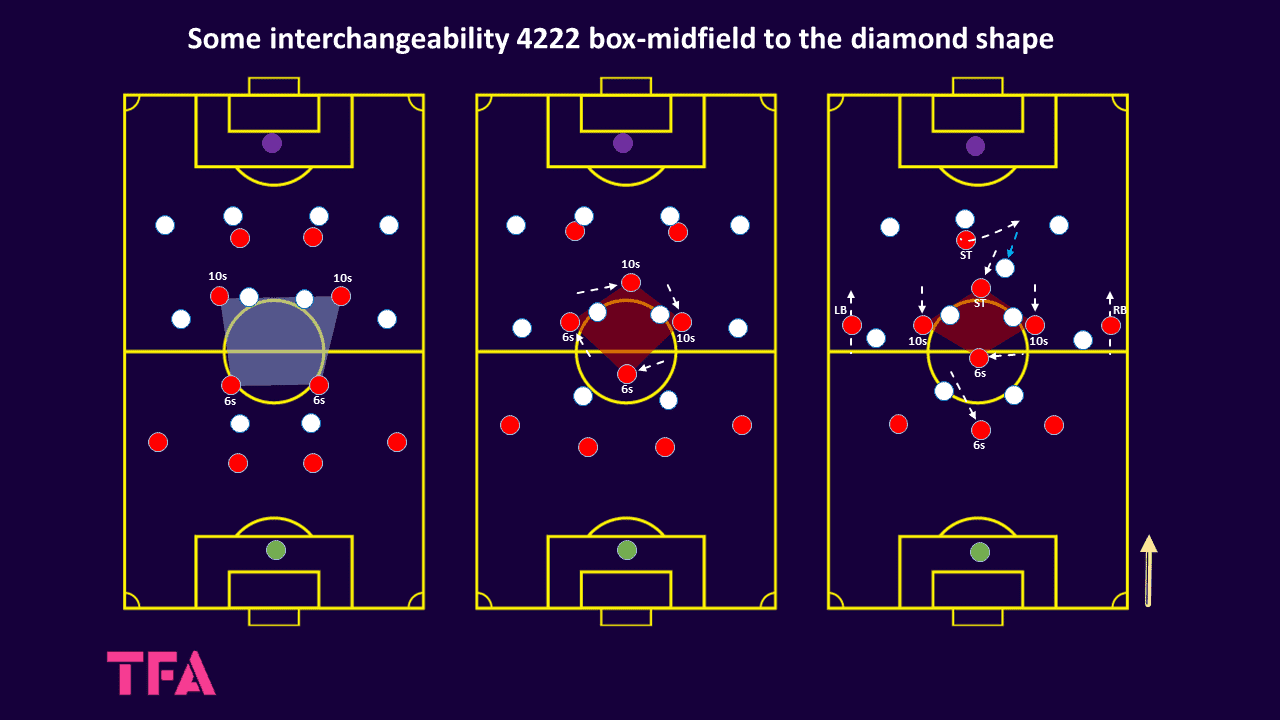

In contrast, the graphic below showcases some of the possible transitions from a box-midfield to a diamond shape.

One of the common initial formations that can lead directly to the box-midfield is the 4-2-2-2.

In the first transition, the box can be transformed either clockwise or counterclockwise.

One of the No.

6s act as a pivot, while the other moves up to be a central midfielder.

Simultaneously, one of the No.

10s moves diagonally to function as a straight playmaker between the lines while the other No.

10 drops slightly deeper to form the diamond.

In the other setup, not only the midfielders but also most of the team engages in the dynamic.

One of the No.

6s drop between the centre-backs to form a three-man backline which pushes the full-backs forward, while the other No.

6 acts as a sole pivot, and both No.

10s position themselves on either side of the pivot.

Meanwhile, one of the strikers drops off to the head of the diamond while the other striker attempts to exploit the spaces generated.

Summary

In conclusion, this tactical analysis illustrates the analysis of the diamond shape, its variations and some of the interchangeability with the box-midfield.

The diamond and box midfield shapes offer strengths and weaknesses that coaches can exploit based on their team’s characteristics and the vulnerabilities of the opponent.

The interchangeability between the diamond and box midfield shapes adds flexibility and confusion.

Coaches can transition between the two shapes to adapt to specific opponents or situations.

Comments