Pep Guardiola’s teams are renowned for their ball possession stats, build-up from the back, and controlling space around the pitch via player positioning. Since his first stint as a manager for Barcelona B in 2007, it is evident Guardiola’s football philosophy is rooted and influenced by Johan Cruyff’s success and ideology from their time working together when Guardiola broke into Barcelona’s first team.

With this said, adapting to the quality of his players is constantly at the forefront of Guardiola’s approach, referring to this often in press conferences throughout his time at different clubs.

This tactical analysis piece will be an analysis, looking at the importance and emphasis on effective wingers in a Guardiola team, and how the type of winger Guardiola wants has evolved and changed over time in his tactics.

Demands of a Guardiola winger

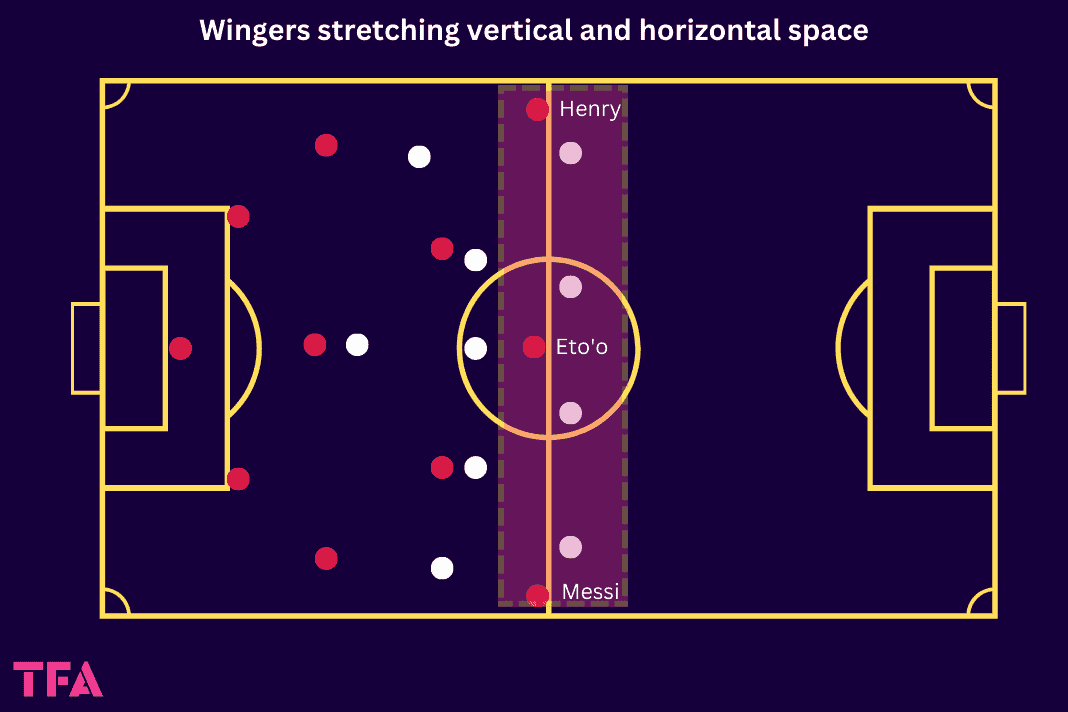

One of Cruyff’s ideas that seem evident in Guardiola’s team still to this day is his demand for players to maximize the horizontal and vertical space on the pitch during the build-up. This is why Guardiola has put a huge emphasis on the importance of disciplined and dynamic wingers throughout his coaching career in Spain, Germany, and now in England with Manchester City.

“More than ever we must move, move, move, and constantly create superiority. We’ll open up the pitch and we’ll look for the wings and then there will be space down the centre.” – Pep Guardiola

By using his wingers to stretch opposition teams vertically and horizontally, Guardiola’s side maximises the space on the field, making it difficult for the opposition to press effectively. This creates space in the centre of the pitch for his midfielders to safely move the ball further up the field.

Although the principles remain, Guardiola has since evolved, adapted, and changed his ideas on the type of wingers he wants in his teams, especially in the final third. From Thierry Henry to Franck Ribery, to Raheem Sterling and Phil Foden, let’s take a look at how the Catalan makes use of the qualities of these players and why spending 100 million pounds on Jack Grealish is showing signs of an astute transfer.

Barcelona (traditional wingers and inverted strikers)

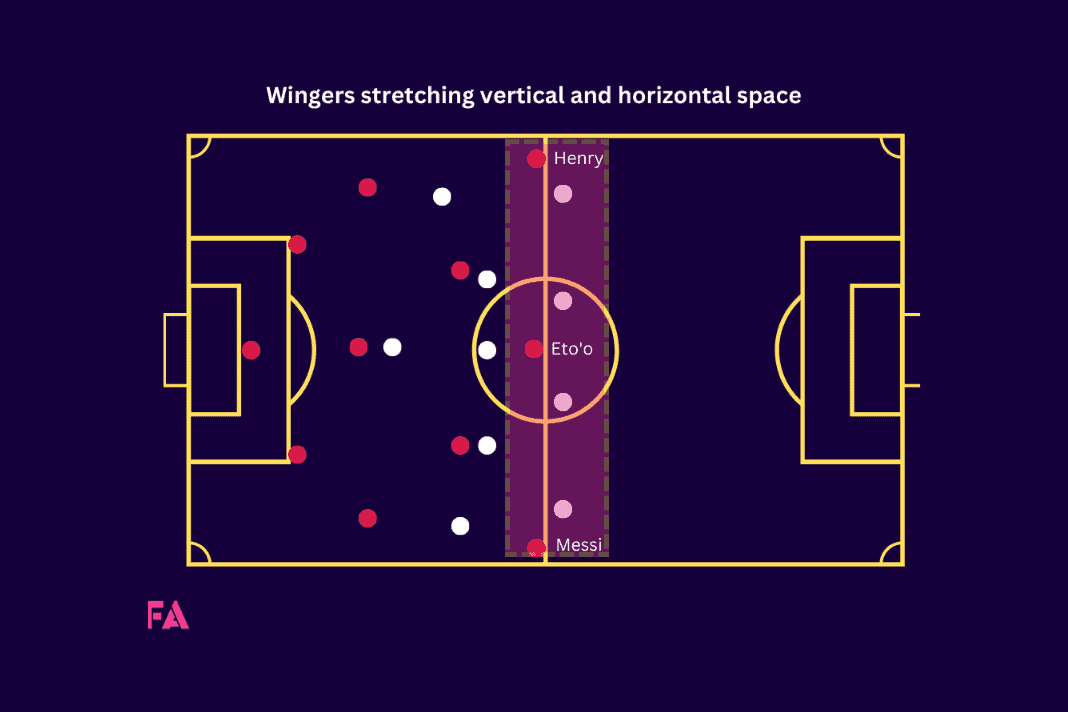

It has been 15 years since Guardiola’s first season as a manager for Barcelona, stepping into the upper echelon of Spanish football, and inheriting a squad filled with world-class talent with the likes of Samuel Eto’o, Henry, and a young Lionel Messi at his disposal. Guardiola often lined up in a 4-3-3, asking his wingers to stay high and wide.

With Eto’o, Henry, and Lionel Messi, he had pace, guile, and excellent players in 1v1 positions. At the time, opposition teams in La Liga often pressed from the front. During the team’s build-up phase in their half, his wingers were asked to stay high and wide as decoys to occupy the opponent’s back four to create numerical superiority in the build-up.

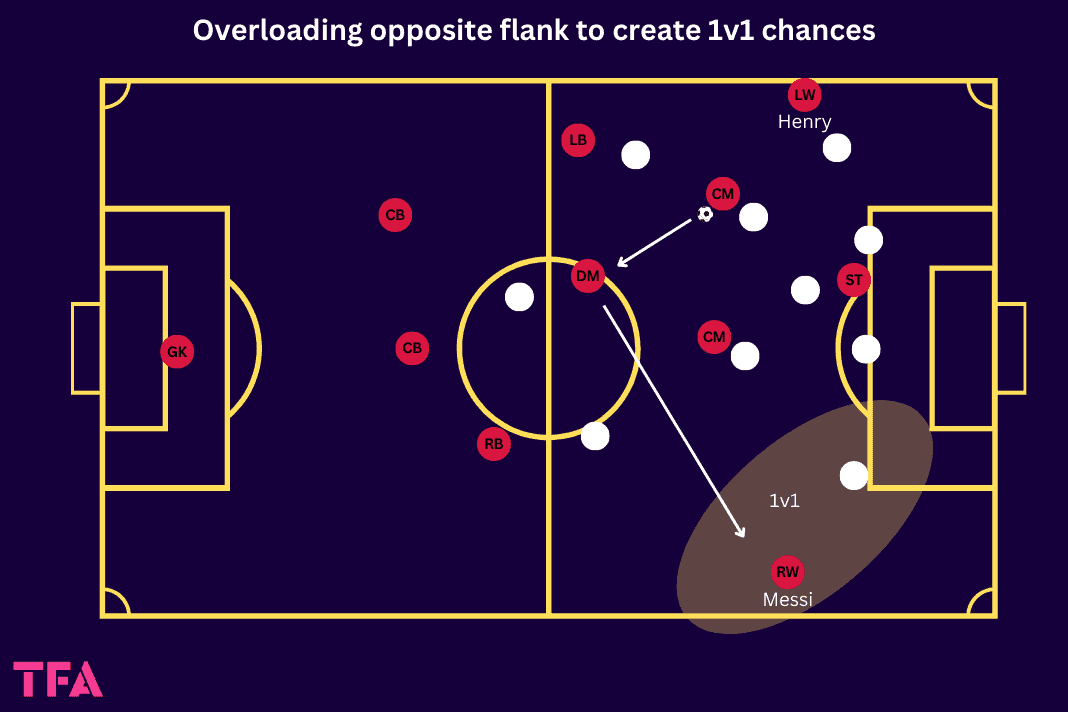

Guardiola also tended to overload one side of the pitch to then switch the ball at speed to the opposite side to provide Messi or Henry with a 1v1 against the opposition’s fullbacks for a shot at goal, with both players registering 34 and 26 goals contributions that season, respectively.

Although largely successful, winning La Liga and getting to the final of the UEFA Champions League, star players like Eto’o and Henry began to grow tired of Guardiola’s demand for positional discipline from his wingers. Compounded with the fact that opposition teams began to sit back and double up on the wings, Guardiola’s wingers experienced their first evolution. Enter David Villa and Pedro.

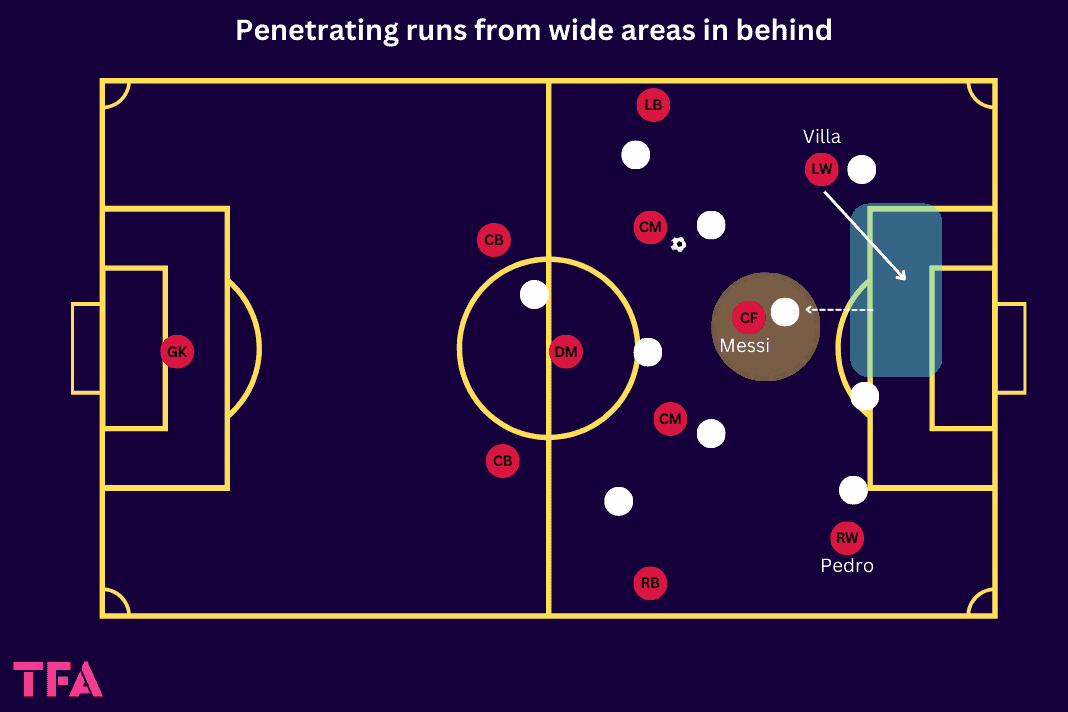

Unlike the previous two seasons, Guardiola moved away from employing traditional wingers who excelled in 1v1 situations to inverted strikers who were willing runners and could make penetrating runs from wide areas, exploiting space behind the opposition’s back four.

Asking for the ball in behind instead of wide and to feet is a major shift in his previous approach to wing play. This is partly due to the rise of Messi employed in a false nine position, dragging defenders out of shape, but more importantly, Guardiola used his wingers to stretch teams vertically to allow the likes of Messi, Andreas Iniesta, and Xavi more space to dominate the opposition’s central areas.

With his wingers making runs narrow and deep, Guardiola used his fullbacks to stretch the play horizontally. This proved incredibly successful with two Champions League titles in three and radically changing the landscape of football, with teams across Europe adopting high-flying fullbacks and inverted wingers of their own.

Bayern Munich (traditional #9, and crosses in the box)

Under Jupp Heynckes, Bayern Munich were the reigning European Champions with incredible speed and directness in transitions, led by the flying inverted wingers of Arjen Robben and Franck Ribery. With Guardiola’s arrival, Bayern’s play became more systematic and methodical. Acknowledging the difficulty in stopping the devastating counter-attacks in the Bundesliga, Guardiola moved Philip Lahm and David Alaba (world-class overlapping fullbacks at the time) narrow into midfield to support the circulation of the ball and control defensive transitions.

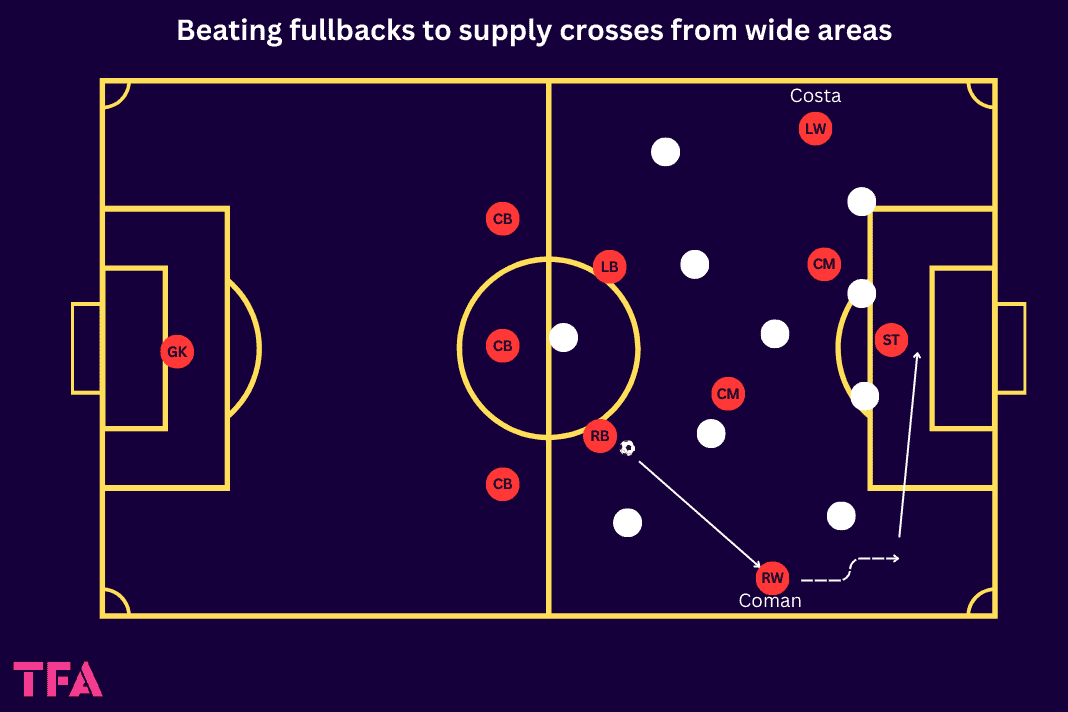

As a result, Bayern’s wingers again became the tools to stretch the game wide and control the team’s width. However, different from Henry and Messi at Barcelona, especially with the arrival of Robert Lewandoski in support of Thomas Muller in central areas, Guardiola isolated his wingers in 1v1 situations with the aim to provide dangerous crosses for his attackers, instead of shots on goal.

Robben and Ribery (alongside numerous injuries throughout Guardiola’s time at Bayern) struggled to cope with the demands of this role, and Douglas Costa and Kingsley Coman were brought in, both with incredible pace and the ability to beat players 1v1 around the outside of the fullback.

Lewandoski and Muller particularly enjoyed the new role of the wingers and the constant supply of crosses under Guardiola with Muller, in particular, registering a combined 71 goals and assists across his three seasons with Guardiola.

Manchester City (fast and direct)

As Guardiola moved from Germany to Manchester, much of his first few seasons with the Blues reassembled the sort of demands he had for his wingers as he did with Bayern Munich. He brought in Nolito and Jesus Navas to rotate alongside Raheem Sterling and Leroy Sane to play as orthodox wingers, getting high and wide, beating fullbacks to supply crosses for Sergio Aguero. As always, the opposition sought to find ways to nullify Guardiola’s potent attack, with teams frequently dropping deep and often deploying five defenders on the edge of the box.

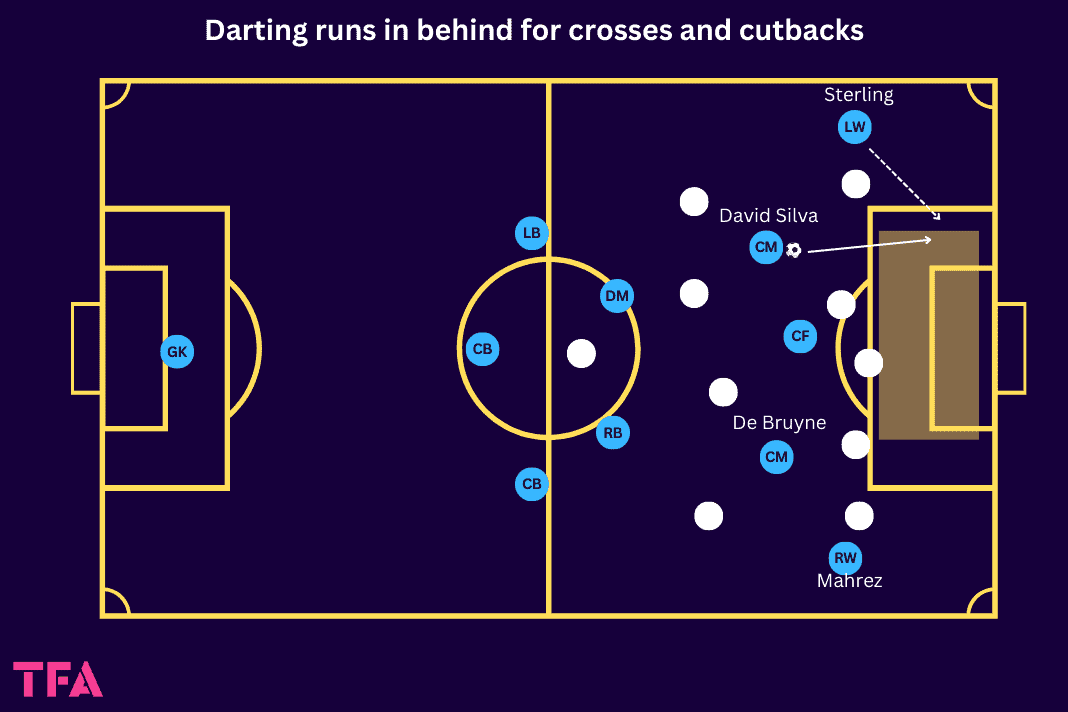

With the quality of Kevin De Bruyne, Ilkay Gundogan, and especially David Silva, Guardiola evolved the wingers in his second and third seasons in the Premier League to become a version of the inverted wingers once seen in Barcelona with an element of Bayern’s crosses into the box. Raheem Sterling and Riyad Mahrez started being deployed as inverted wide wingers, waiting for the opportune time to make darting runs behind fullbacks instead of out wide and to feet when the ‘10s’ would pick up the ball, delivering devastating first-time crosses across the six-yard box or cut-backs for City’s players to tap in.

This was especially effective during the time City played without an orthodox striker in Aguero when he made his move to Barcelona, so long as City committed enough players into the box.

Manchester City 2022 – 2023 (wide playmakers)

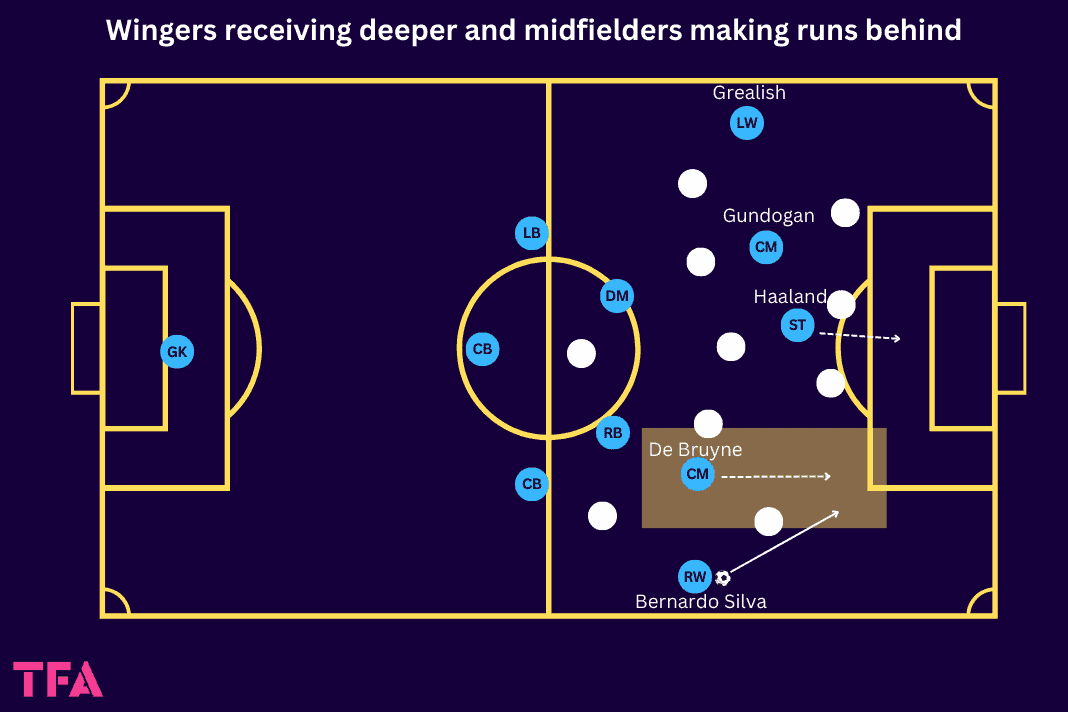

Here, we have arrived at the current 2022/23 Premier League season, where City’s lineup is dominated by technical ball-playing midfielders, patient penetration in the final third, and the return of a traditional number ‘9’ and a goalscoring sensation in Erling Haaland. Gone are the days of the pacy and direct wingers of old, beating fullbacks and running in behind, and in with the wide playmaking midfielder.

Guardiola’s most frequent wingers used this season are Jack Grealish, Bernardo Silva, Phil Foden, and Riyad Mahrez, with the exception of the Algerian, all of whom can be seen as wide player-makers who possess incredible ball retention and technical ability.

Guardiola’s build-up play from the back is still largely the same. Wingers occupy positions high and wide. However, what is evident is the changes in the winger’s role in the final third of the pitch. Guardiola is asking his wingers to be an outlet for possession out wide, and allowing his central midfielders in Gundogan and De Bryune to make underlapping runs behind the opposition’s back four.

These runs are incredibly difficult to pick up and Grealish especially has found joy this season receiving the ball in deeper areas and helping City retain possession in wide areas. This also capitalises on De Bruyne’s ability to work in the half-space and deliver crosses into the ‘corridor of uncertainty’ for a certain 6 ft 4 striker to finish, with the two combining for 7 goals this season in the Premier League alone.

Conclusion

Guardiola’s emphasis on adapting to his player’s quality has seen a constant evolution in his wingers throughout the past 15 years in Europe’s top flight, as this tactical theory piece has displayed.

From the converted striker-turned-winger in David Villa to the mercurial and dynamic duo of Kingsley Coman and Douglas Costa, and now the 100 million pound man Jack Grealish, Guardiola looks to find the system to best fits the qualities of his players, and no doubt will we see a continuation of this evolutionary process when teams look to stifle City’s wide playmakers next season.

Comments