We’ve all been there.

We’re watching our favourite teams, maybe a big match in the Champions League, and a world-class player scores an outrageous goal that leaves us bewildered.

We are blown away by the quality of the goal, maybe of the sequence as a whole. From a fan’s perspective, we get to see replays from a few different angles, then a minute later the ball is back in play. Our analysis has ended and we’re right back in the flow of the match, though understandably still abuzz given the quality of the goal we’ve just witnessed.

We’re going to go a little bit deeper here, not simply focusing on those goalscoring plays themselves, but on the movements and actions that turn those goals from possibility to reality.

This tactical analysis focuses on the intelligent movements that separate elite attackers from the pack. We will look at the movements of the world’s best forwards, separating them into three distinct categories. The first group is the deep-lying playmakers, who are followed by more complete attackers, and then ending with the world’s top poachers. We want to identify specific movements and ideas these players habitually implement in the flow of the game. The ideas behind the movements, as well as the flawless execution of the actions themselves, are the differentiators that have taken these forwards to the top of the game.

The deep-lying playmakers

Let’s start with our first group, the deep-lying playmakers. With each of these players, we are looking specifically at the types of roles they play at this time. Their contributions are not exclusively those of deep-lying playmakers, but their efficiency and impact from deeper areas of the pitch are standout qualities.

The first objective we will address is the way forwards use their presence and check into midfield to connect play. The first player we will turn to is Harry Kane of Tottenham Hotspur. The big Englishman is an extraordinary goalscorer, but he has also developed the skill set to drop into midfield to get touches, create pockets of space, and utilise his excellent passing range.

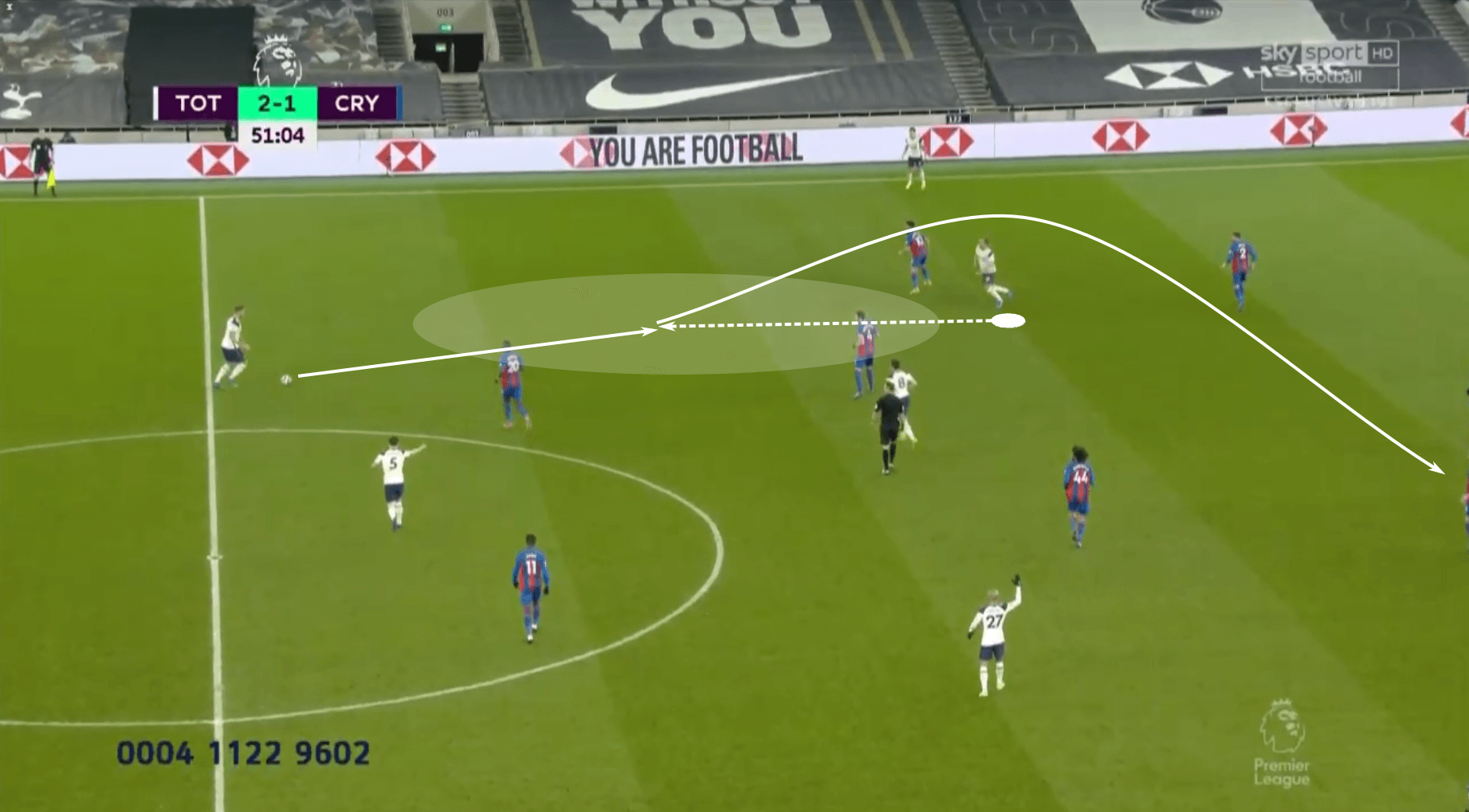

In a match against Crystal Palace, we had a great example of Kane offset to the left half-space to create numeric equality on that side of the pitch and situate himself against a single centre-back rather than both.

As Tottenham progressed to midfield, Crystal Palace was set up in a 4-4-2 middle block. Their press held a positional superiority in the middle of the park, which led Kane to check to the ball, moving in front of Crystal Palace’s midfield four. As Kane received the pass, he immediately took a touch inside and switched the point of attack to the right-wing.

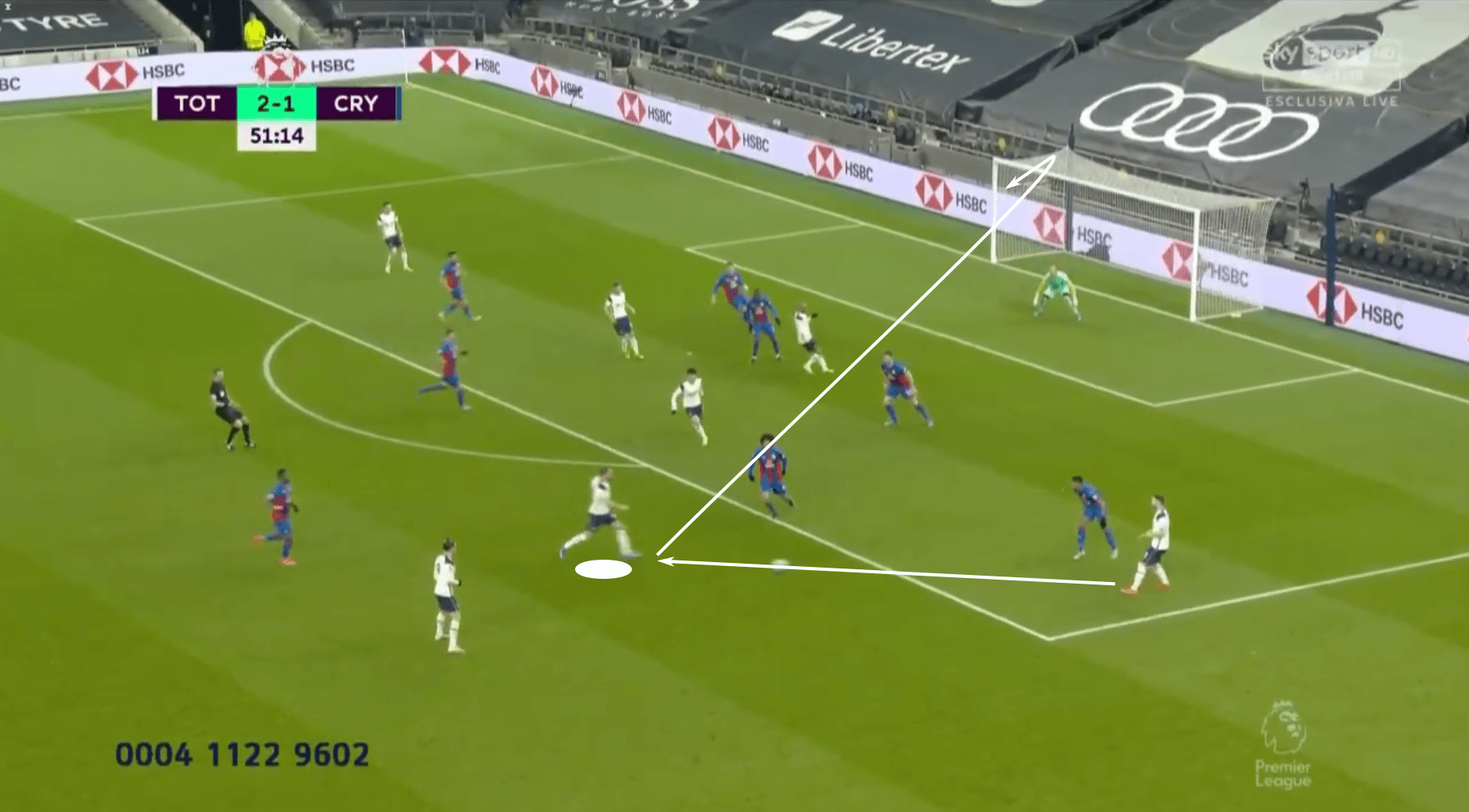

But his participation in the play does not end here. Rather than slowly regaining his place at the top of the formation or making a straight run into the box, Kane decided to follow his pass, attacking the space between Crystal Palace’s midfield and forward lines. With the opponent’s midfielders dropping into the box to contain the wide threat, Kane located open territory in the right half-space, just outside of the Crystal Palace box.

As the ball was sent into his running lane, Kane unleashed a bent shot that would have moved David Beckham to jump out of his seat.

With Crystal Palace’s middle block cutting off any opportunities for progressive passes into the central channel or half-spaces, Kane’s decision to check in front of the midfield bank of four was designed to draw that line higher up the pitch, disconnecting them from the backline. With that increased distance, it was easier for him to pick out a high target on minimal touches.

The added advantage is that, with the check into a deep position, Kane has effectively dismarked from the centre-back, giving him the freedom to drift behind the intense recovery run of Crystal Palace’s midfield four. Dismarking with checking runs carries the added advantage of putting these elite attackers in a forward-facing position. There’s perhaps no one better in this particular area than Lionel Messi.

During his final years at Barcelona, the new PSG signing didn’t necessarily have to check into midfield to dismark. As Barcelona circulated the ball, forcing the opposition to constantly update their defensive shape along the X and Y axis, the Argentine simply pulled himself out of the flow of play. Rather than searching for pockets of space with constant movement, Messi’s free role in Barcelona’s tactics let him remain stationary, allowing the tide of players to move beyond him. Refusing to cooperate with the game’s reference points, he took a different approach, refraining from movement as a means of dismarking while also occupying his preferred regions of the pitch.

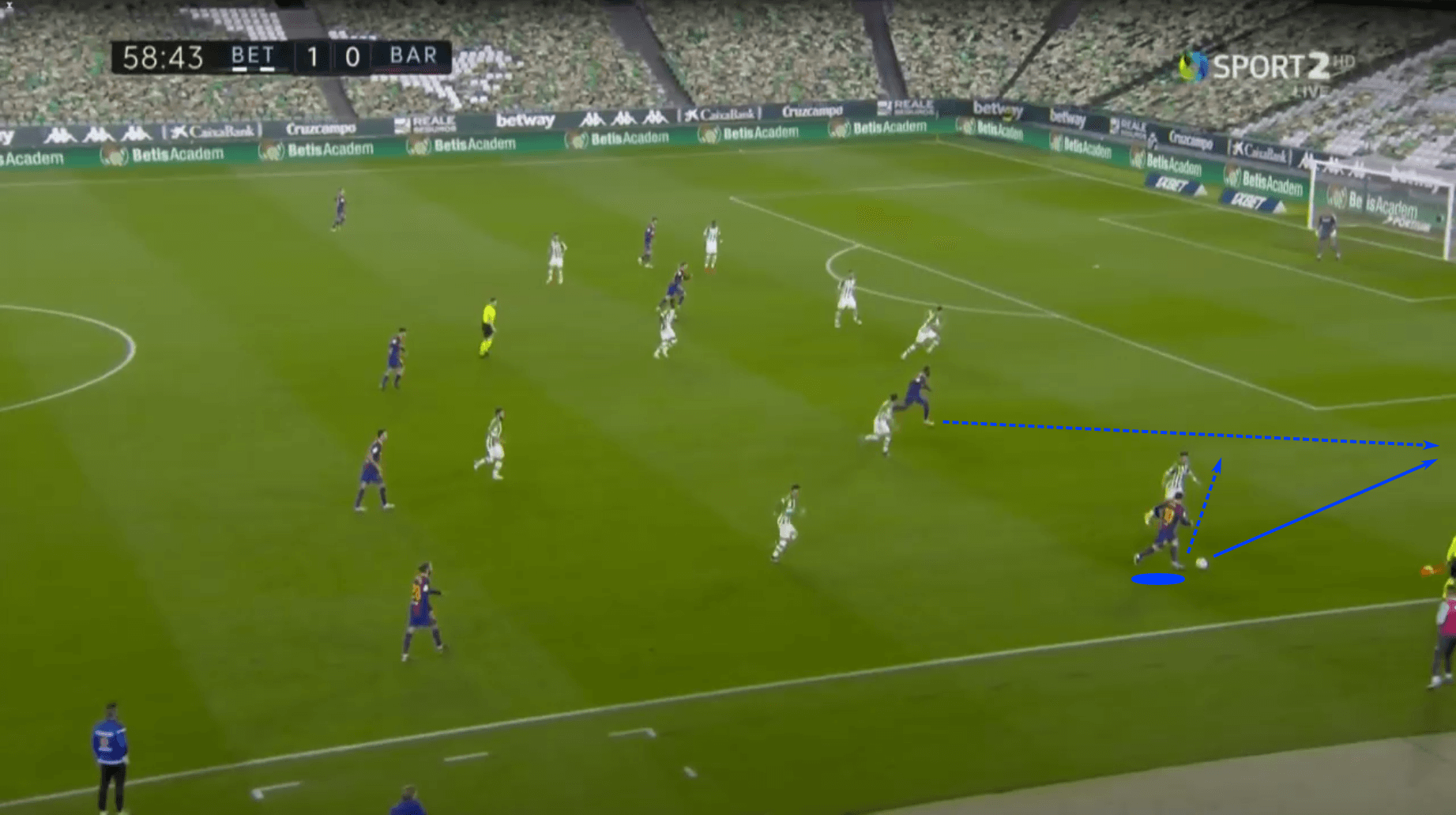

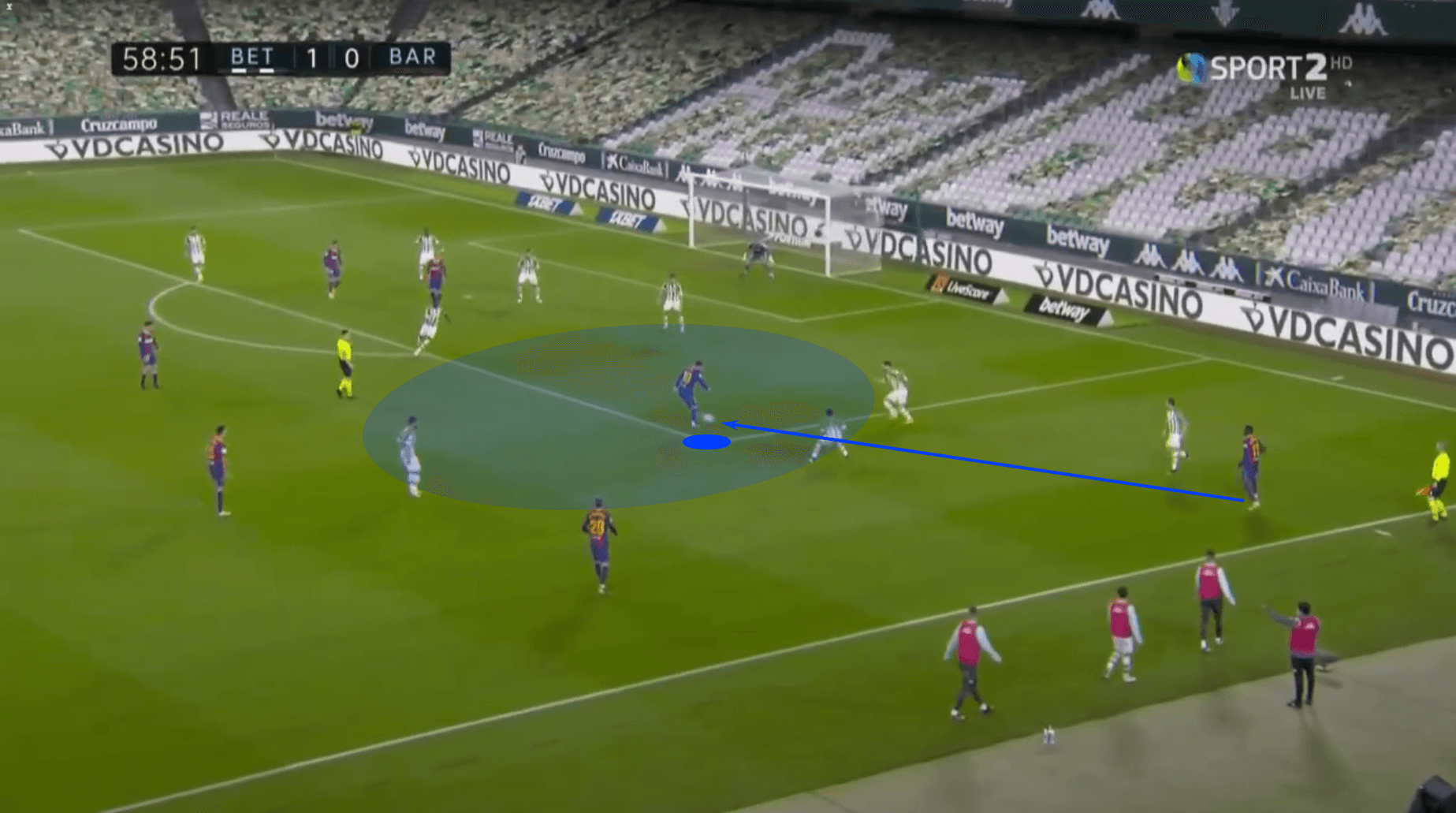

In those instances when his involvement in the play eliminated the possibility of dismarking through stillness, Messi adapted. In a match against Real Betis, Messi played the run of Ousmane Dembélé into the right-wing, cueing a dynamic positional rotation.

But Messi did not make the anticipated sprint into the right half-space—at least not initially. After releasing the pass, he used a hesitation move to deceive his opponent. Since Messi did not give the impression that he would run into the right half-space, the Betis defender left him to track down Dembélé.

Again, Messi’s deception, signalling inactivity, was his dismarking approach. With his direct opponent picking up the cue of inactivity, Messi was free to move into the right half-space and receive a return pass from Dembélé. Just look at the space he was able to claim because of a single moment of stillness.

That brings us nicely to the last of our tactics for this section, as well as our final player.

One of the poster boys for the deep-lying forwards’ style of play is Karim Benzema. Though he’s best known for his interactions with Cristiano Ronaldo on the left side of Real Madrid’s BBC, the Frenchman is still one of the top deep-lying forwards in the world.

His current conundrum is that he is also Real Madrid’s primary scorer, a role he inherited when CR7 departed for Juventus. Thanks to Vinícius Júnior’s breakout start, Benzema has more support managing the goalscoring burden this season. However, the first three years of the post-Ronaldo era amplified the attention placed on Big Benz.

As you analyse the evolution of Benzema’s playing style since becoming Real Madrid’s primary scorer, you’ll find he’s done a better job of managing the depth and width of his checking runs. Rather than the deep check that we saw from Kane, Benzema has adapted his runs so that he’s not pulled too far from the goal as the team transitions to the “attacking the goal” phase.

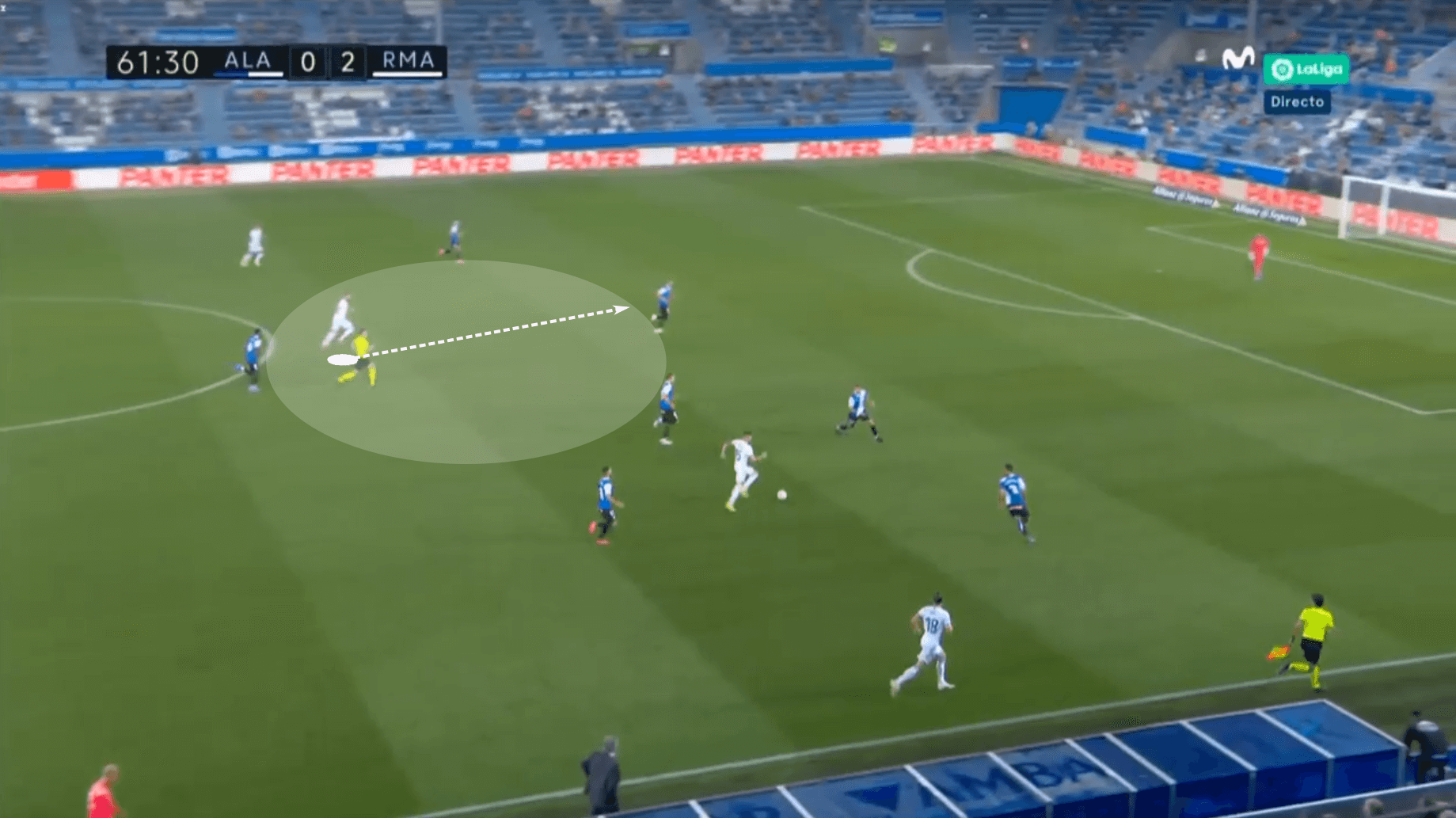

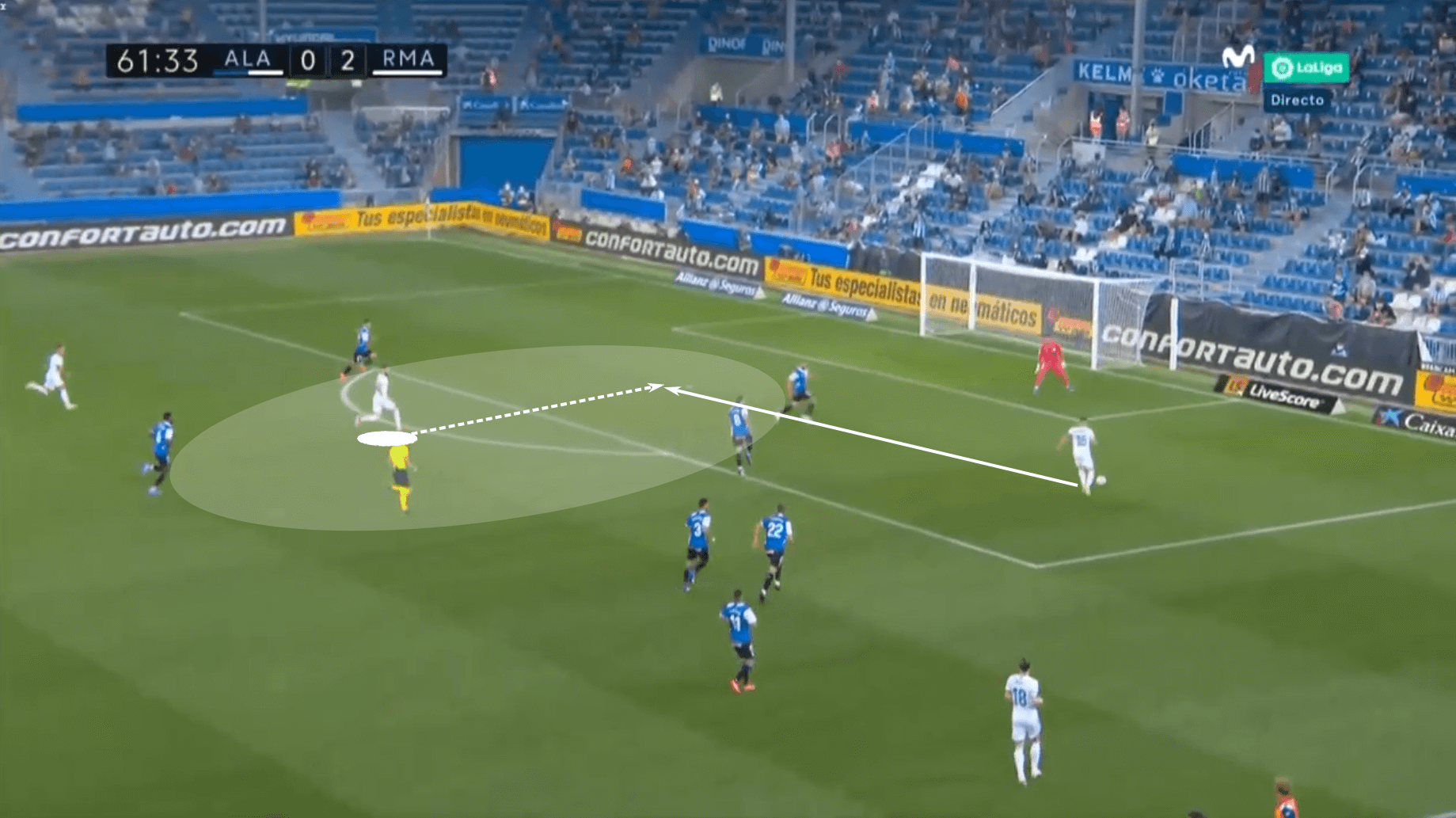

Instead, Benzema will drop into midfield as a means of dismarking, but also to put him in a forward-facing position between the opposition’s lines, leaving his runs largely untracked from those deeper positions. As his teammate on the ball provides the highest point in the team’s attacking shape, Benzema can then tailor his actions as a response to the reactions of the opponent’s backline. If the centre-backs slide aggressively to the left or the right, Benzema can make counter-movements to take advantage of their unbalanced structure. A forward-facing body orientation with a clear sight of the backline’s movements and gaps tells him exactly where he needs to go. That’s what we see as Fede Valverde, a dangerous dribbler in open space, has a run at the Deportivo Alavés backline.

Valverde wins his 1v1 duel, progressing into the Alavés box. As he bears down on goal, he has the option to shoot from a poor angle or to pick out a central target. Benzema’s late run sees him arrive at the exact moment Valverde must play centrally. With time and space at his disposal, Benzema was able to claim his goal.

Benzema, just as we saw with Kane and Messi, used this deeper starting position as a means of creating better-attacking conditions for himself higher up the pitch. As he drops, someone else steps higher. That rotation impacts the way the backline sets up, which is all seen by the forward-facing, deep-lying forward. With an improved range of vision, the forward’s best options become rather obvious.

The complete forwards

Our first section offered an analysis of forwards who excel in a deep-lying playmaking role and the final group consists of the fox in the box type forwards. The middle child in this trio is our class of forwards who do a little (a lot, really) bit of everything. We’ll call them the complete forwards.

The forwards highlighted in this section are players who currently operate in this type of role. It’s not to say that Ronaldo or Messi were not complete forwards at one time, but both players have intelligently adapted their playing styles to their career paths.

Rather than looking backwards, we’ll highlight examples from the present, giving readers and students of the game players and movements to study each week.

Among this class of forwards, there’s no better example than Kylian Mbappé. When you watch him play, it’s easy to see why PSG was willing to pay €180 million for him and why Real Madrid was willing to match that fee this summer, even with a single year left on his current contract. Mbappé’s ability to carry out any attacking role in any part of the pitch highlights his football IQ and incredible ability.

PSG’s tactics for the current campaign remain a work in progress, but Mbappé has typically operated as a left-forward with frequent rotations to the centre of the pitch during his time at PSG. Given his 1v1 dominance and ability to turn the corner on the defender, Mbappé’s primary role as a width provider who’s also well-positioned to stretch the field vertically has made him the world’s most valuable player…and our first sequence in this section shows how he uses width to his advantage.

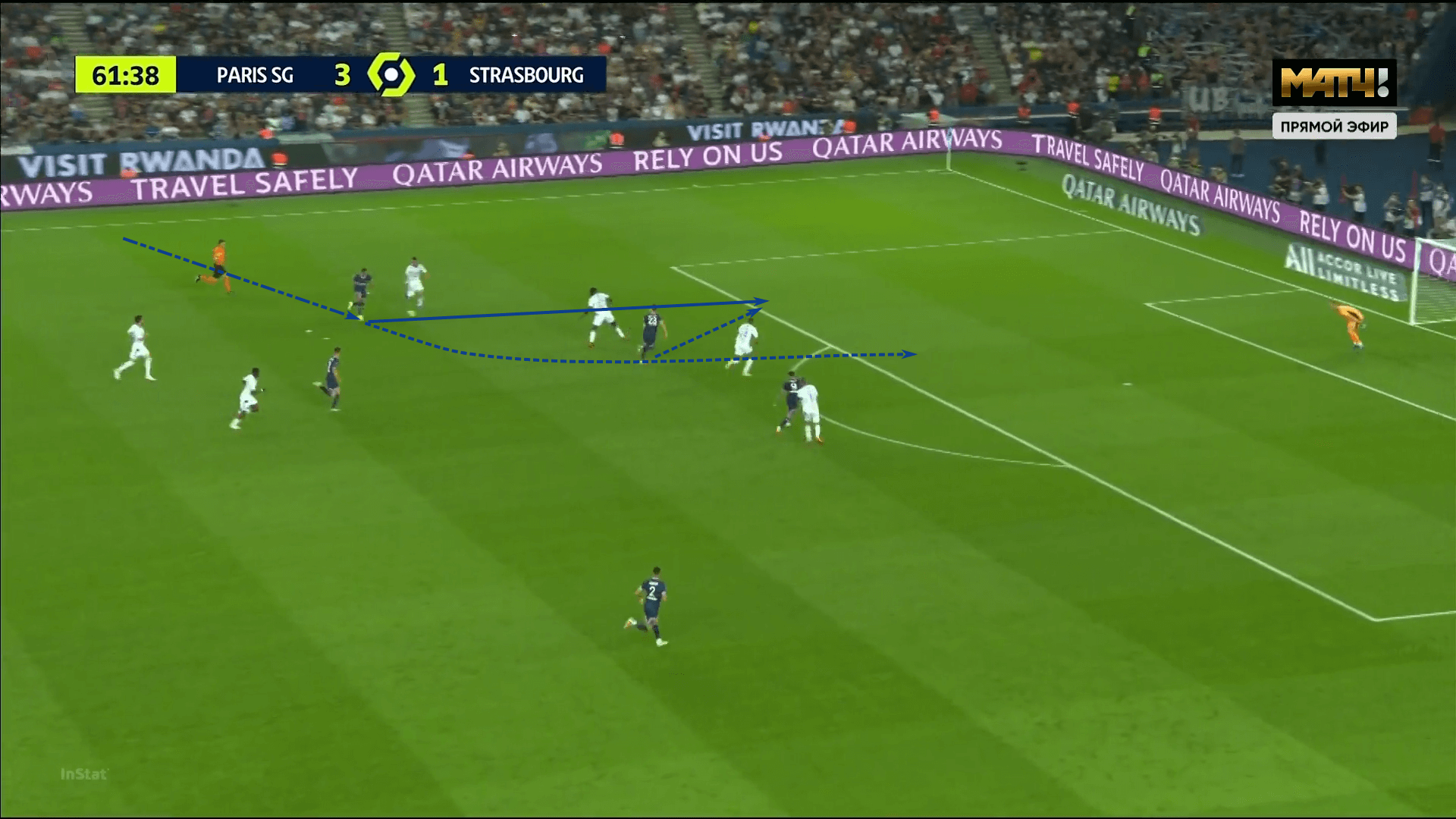

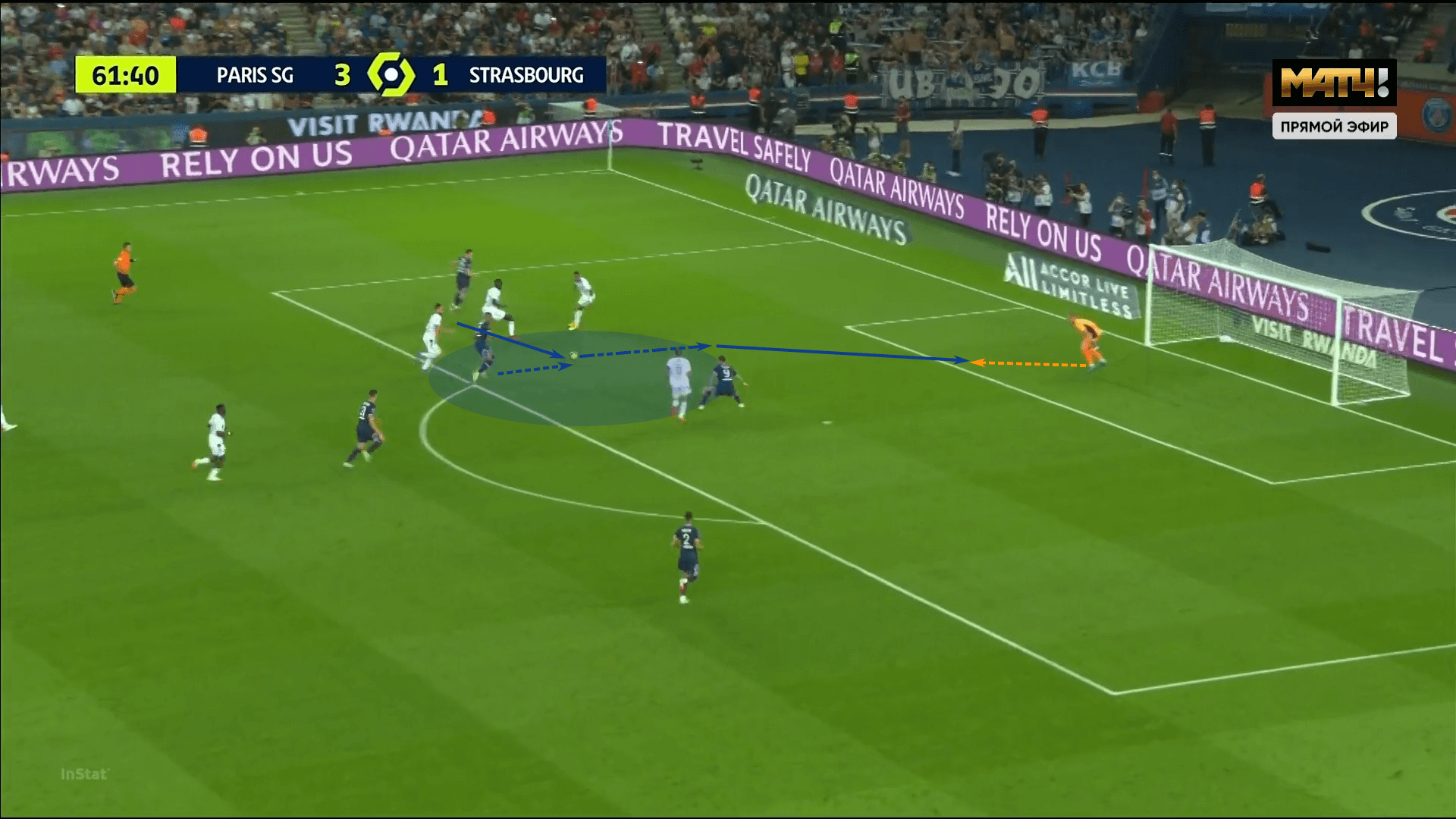

Mbappé initially starts high on the left-wing and engages his defender in a 1v1 duel. The Real Madrid transfer target cut inside on his preferred right foot, leaving the Strasbourg right-back chasing and the right centre-back pinned in coverage. Seeing the near-sided centre-back pinned, Julian Draxler made a run into the 2/4 gap. Mbappé played the simple through pass and continued his run into the central channel.

Draxler made the return pass to Mbappé, who took a poor touch and lost the ball to the keeper. Though he doesn’t get his goal, Mbappé stretching the width of the pitch is an excellent example of a player leveraging his skill set to create favourable attacking opportunities. Taking up a high and wide starting point increases the likelihood of finding that 1v1 isolation he enjoys. With his pace, Mbappé has the option to push the ball down the line and run past the defender or, if the defender overcommits towards the touchline, he’s well-positioned to cut inside on his stronger foot and penetrate centrally.

His starting positioning is the most important piece of this sequence, but his movements on and off the ball highlight his dynamic presence on the pitch. First, we see his dribbling ability. Second, the intelligence to pin the second defender while still attacking the first which, third, sets up the through pass to Draxler. Finally, there’s the continuation of his run knowing that his initial dribble and pass have removed three players from the centre of the pitch with the lone remaining member of the backline occupying Mauro Icardi. In this sequence, Mbappé stretches the width of the pitch to create his own running lane centrally. It’s a brilliant, well-orchestrated move by the young Frenchman.

But Mbappé isn’t the only wonderkid on the list. Just across the border is the 21-year-old Norwegian sensation Erling Braut Haaland. He has taken the game by storm since his 2020/21 Champions League performance against Liverpool. Another player with a comprehensive skill set, Haaland will serve as our example for the next movement, which is stretching the pitch vertically.

He and Mbappé are wonderfully direct players, the latter of the two showcasing fantastic shoulder feints towards depth to unbalance his defender, then burst into height, but this portion of the analysis will focus on Haaland’s movement in the flow of a counterattack.

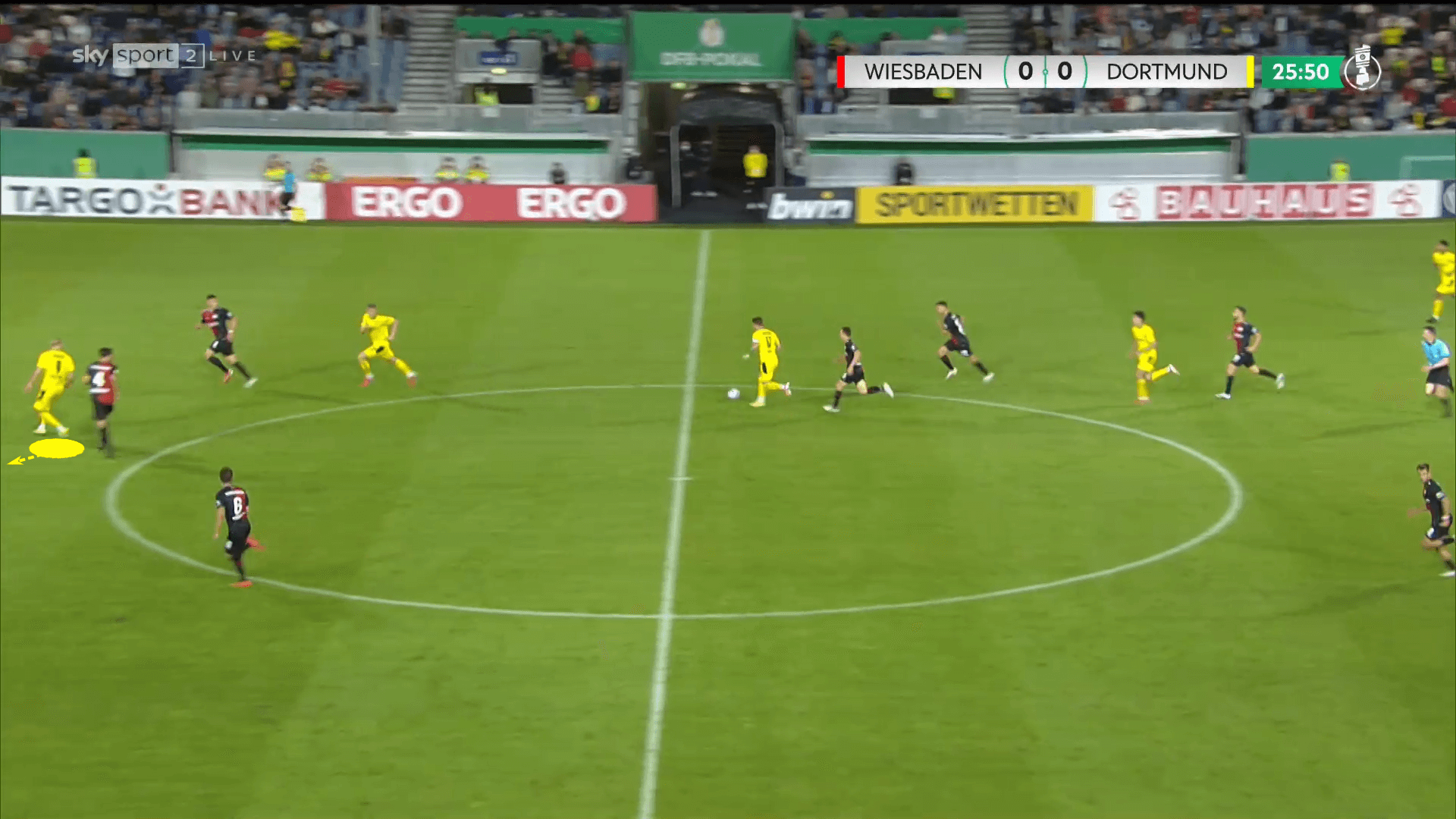

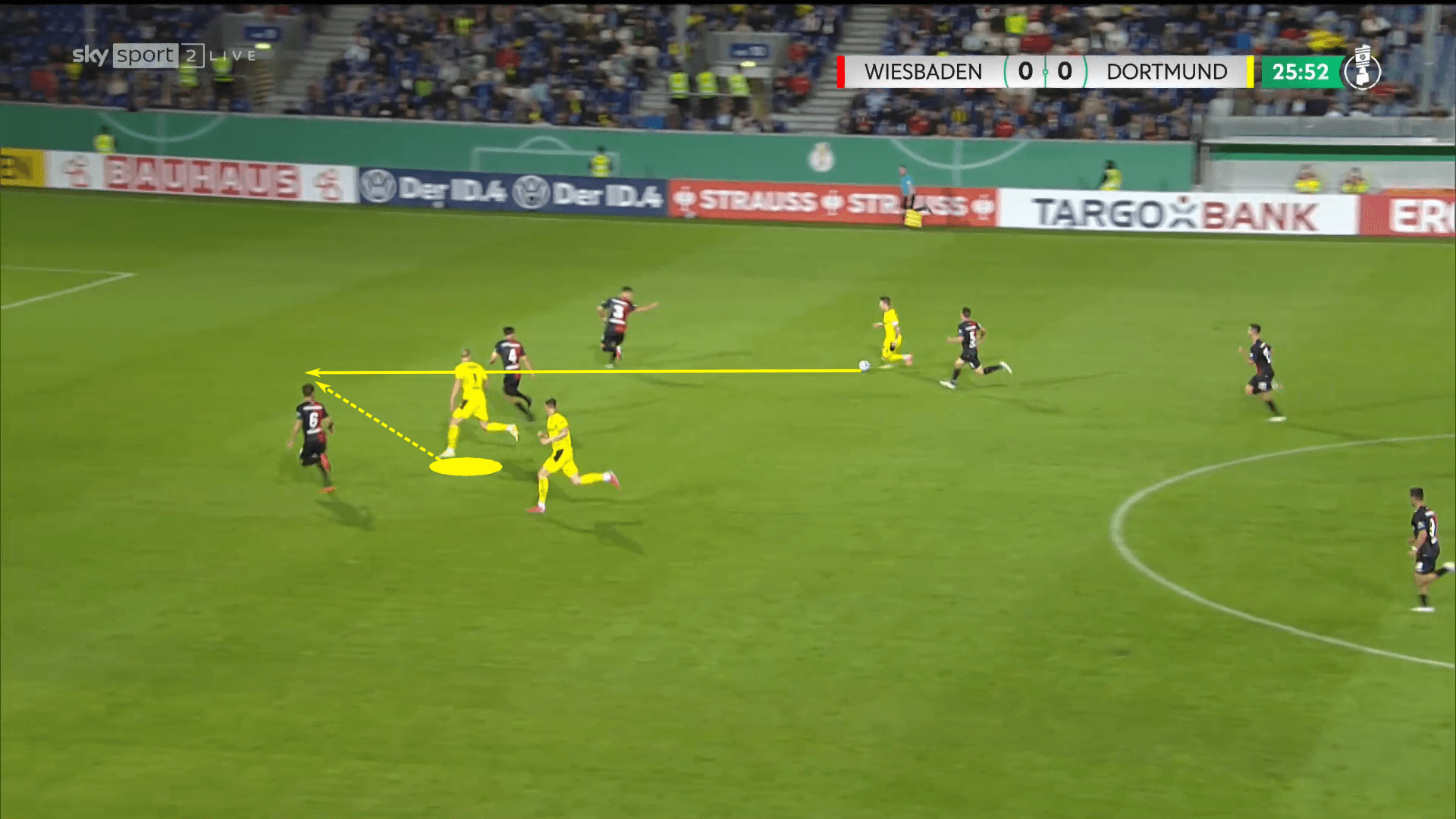

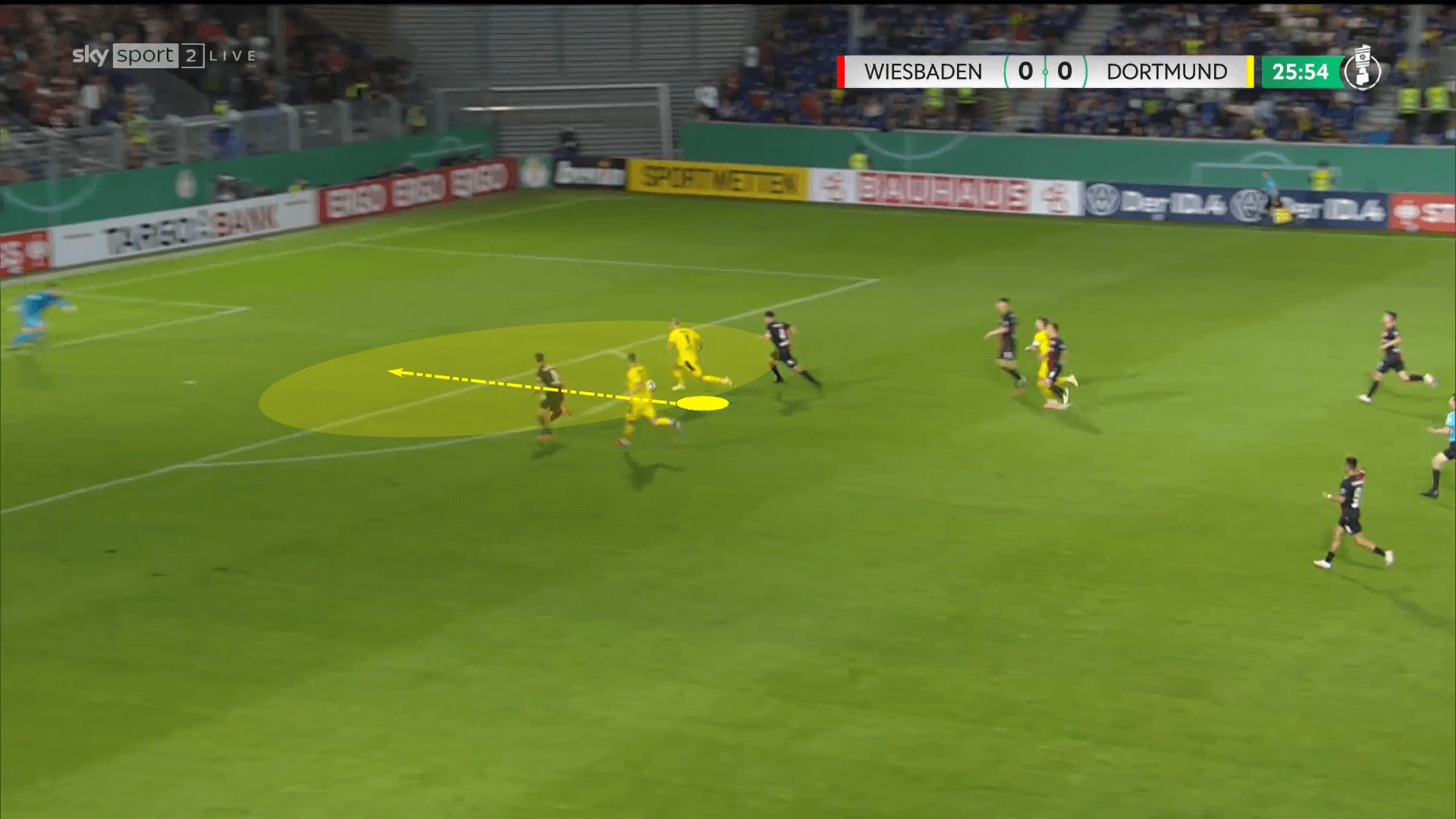

In this example, Haaland had offered the vertical ball, but it was delayed, leaving him in an offside position. Notice that his current position is just inside the right centre-back’s line of vision.

As play progresses 10 m, Haaland has corrected his positioning, moving into the defender’s blindside. His top two objectives here are to position himself outside of the defender’s line of vision, which makes his movements more difficult to track, and to create space for his teammate to engage in a 1v1 duel. Whether his teammate decides to engage on the dribble doesn’t matter. What’s ultimately happening is that Haaland is using his movement to manipulate the positioning of the right centre-back. That player’s positioning then informs the 1st and 2nd attackers of their options for progression. If the right centre-back move towards the ball, Haaland can receive a pass centrally to his feet. If the defender makes a straight run in an attempt to stay close to Haaland, then the 1v1 duel and through ball to the big Norwegian are options, especially since his positioning on the blindside of the defender allows him to time his run more discreetly.

In the end, the through ball is played and Haaland’s blindside positioning allows him to easily accelerate past the defender and score.

One theme we’ve already addressed in this analysis is the forward-facing attacker. That theme is immediately evident in the Haaland example. To make the move to goal, or to attack the opponent more efficiently, a forward-facing body orientation allows the high targets to run at or behind the backline. Ideally, defenders want to keep play in front of them. It’s easier to read, more predictable.

Haaland did well in that sequence to participate in the attack with forward-facing body orientation. While he used it to stretch the backline vertically, we do have examples of elite players targeting a forward-facing body orientation between the lines to signal a transition to attacking the opponent. Let’s go back to Paris and focus on a third world-class attacker, Neymar.

With Mbappé and Icardi In the lineup, Neymar could afford to diversify his approach. Since those two stretched the width and height of the pitch, you would often find Neymar getting between the opposition’s lines. Whether there were three at the back or four, PSG tended to use a double pivot during the 2020/21 campaign. One of the benefits of a double pivot is that it often forces the opposition to commit an additional player further up to pitch to contest the build-out. As opponents tried to high press or counterpress PSG, the distance between the backline and highest midfielders increased. That’s exactly what Neymar targeted.

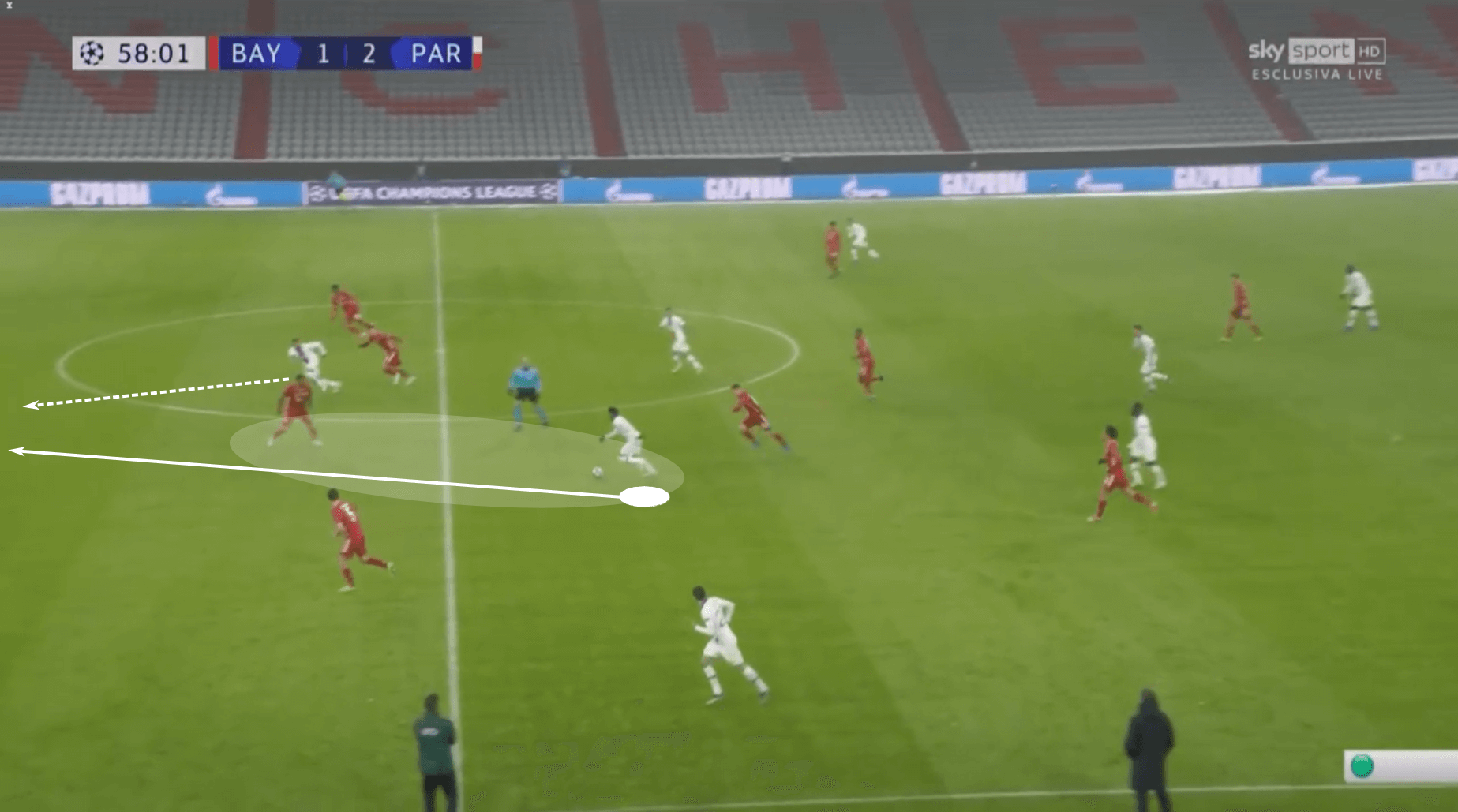

That increased distance opened up additional space for him to get between the lines. As we see in their Champions League match against Bayern Munich, Neymar initially started with the highest line of attackers, then quickly dropped into the pocket of space between the backline and midfield.

Receiving on the half-turn, Neymar is then able to run at the backline, pin Jérôme Boateng, and slip a through ball into the path of Mbappé.

As opponents counterpress or look to initiate play with high and middle blocks, playing into a forward-facing playmaker between the lines allows for a change in tempo. The attack then becomes very direct, allowing the team in possession to determine how quickly they want to engage the opponent’s backline. If the opponents are caught off guard and engage without limiting access to the space behind their lines, attacking becomes very simple, as in the case of PSG vs Bayern. As the first attacker, Neymar in this example, attacks and attempts to pin the backline, his forward-facing body orientation gives him a full view of the backline’s positioning and how his teammates intend to attack their structure.

Like stretching the width and height of the pitch, receiving between the lines with a forward-facing body orientation is a clever way that elite attackers move off the ball with minimal contact to positively influence play.

Our final movement in this section still starts off the ball, but brace yourself for a heavy dose of physicality.

The final movement of complete forwards we will address in this analysis is how they control the point of attack, the opponent’s positioning and his body orientation by physical means. Though Haaland is well suited for this example, there’s perhaps no one better in the game in this area than Romelu Lukaku. The big Belgian is a master at controlling opponents physically and using their body mechanics against them.

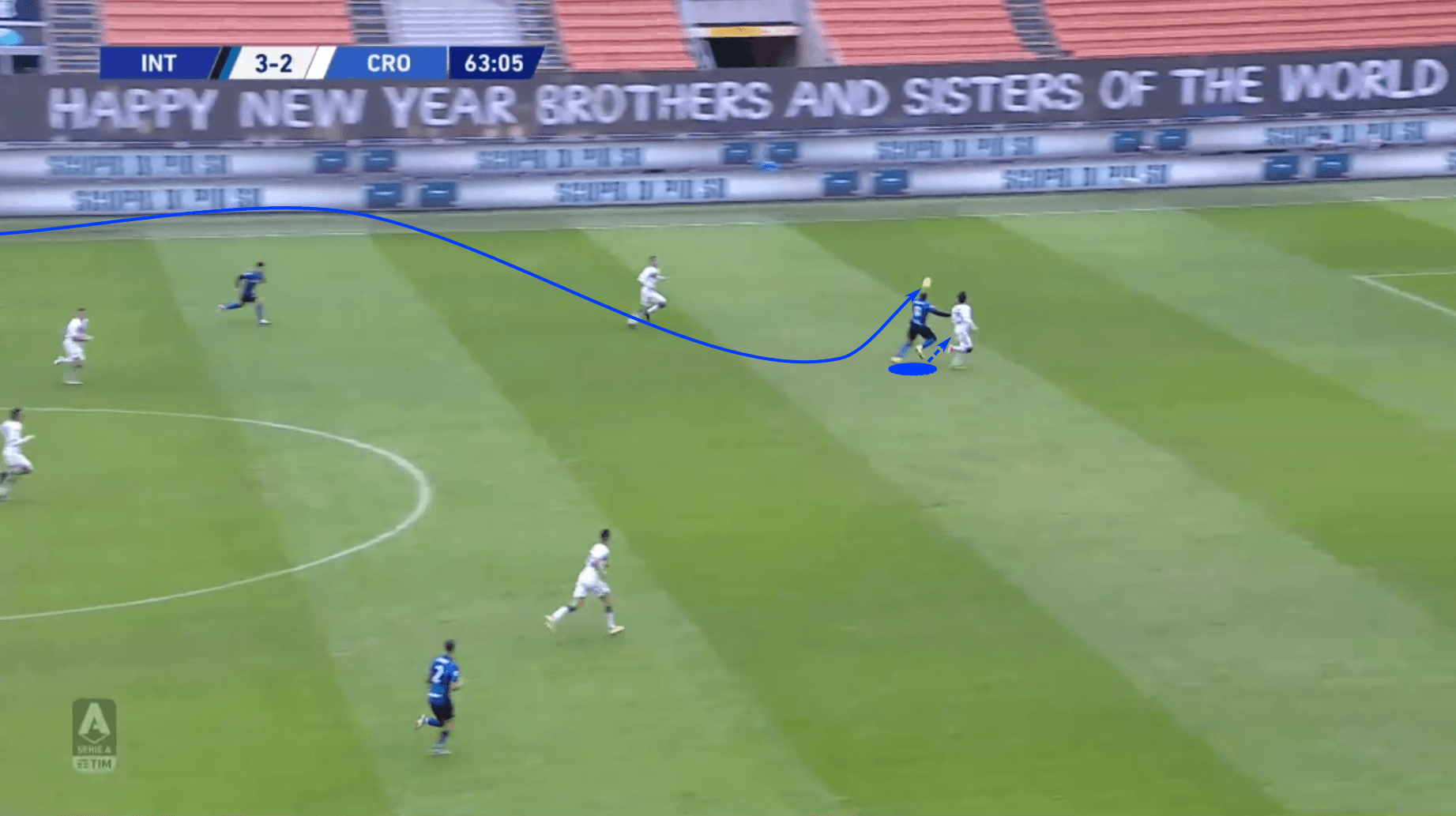

The setup for this sequence is fairly simple. Lukaku makes a run into the left half-space and a long pass over the backline is played into his path. That’s the basic structure for our first image in the Inter Milan vs Crotone match. We have Lukaku 1v1 against the last field player. Both players are moving on a diagonal towards the corner flag with a Crotone player, Sebastiano Luperto, appearing to have half a step on Lukaku.

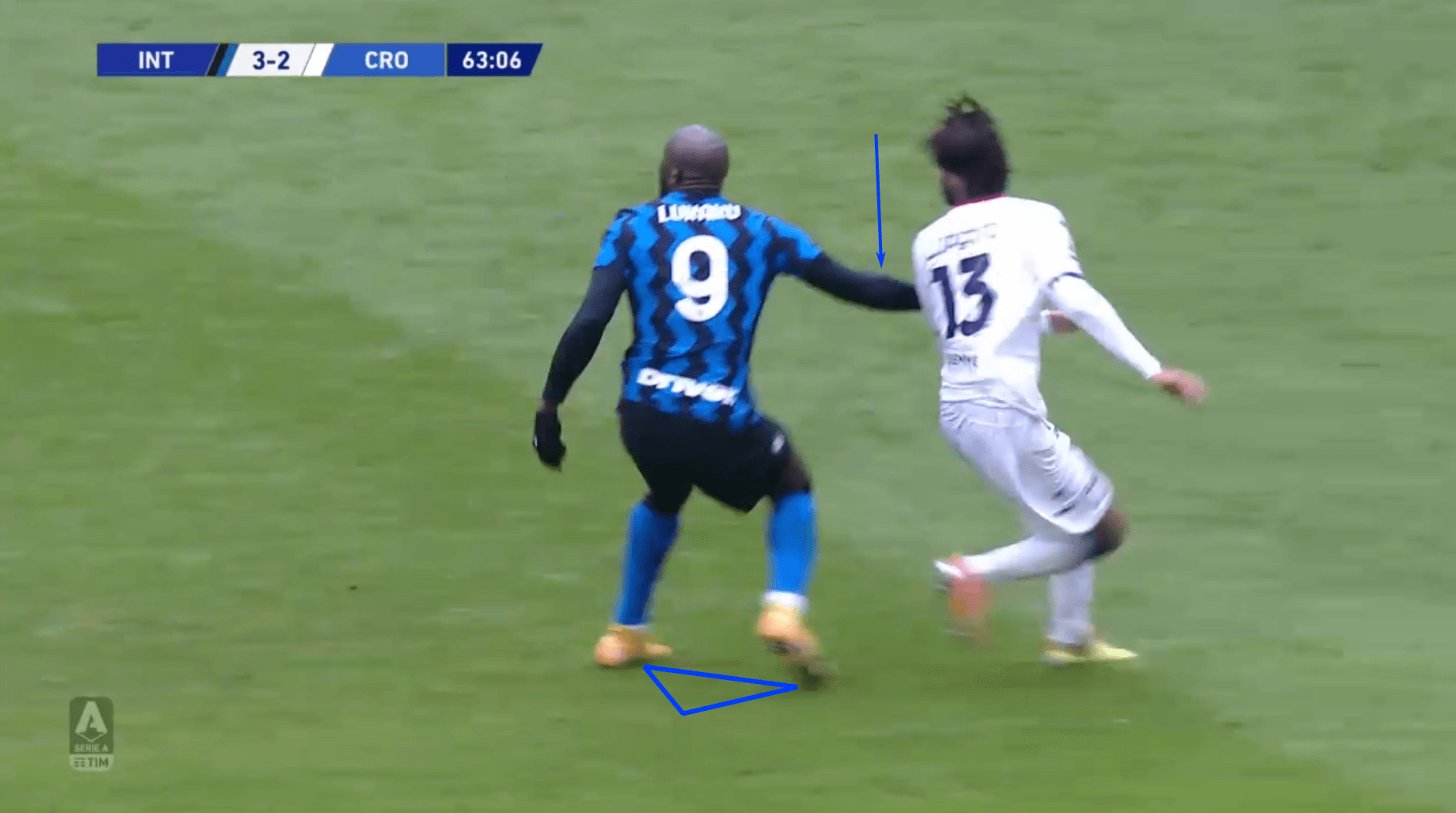

And that’s where his advantage ends. As we get a close-up of Lukaku and Luperto (who’s 6’3″), we can see the way the former Inter Milan man establishes his balance with good quad activation and distance between his feet. He’s also prepared to use his upper body strength to fend off Luperto, who is still running in the direction of the corner flag, unbalanced and only now starting to understand Lukaku’s intentions.

In American football, defensive linemen are taught the “swim move”, which is an upper-body movement designed to move the aggressor from one side of the defender to the other. If the aggressor wants to move from the left side of the blocker to the right side, he uses his left hand to stunt the blockers movement to the right whilst using a swimming motion to move his right arm over the left hand, allowing him to establish body positioning on the blocker’s right side. That’s what you see in the final image from the section.

Lukaku’s right hand engages Luperto’s left hip while the left arm “swims” over the defender’s body to give the Belgian positioning to his mark’s left. One of the key features here is the relative balance of the two players. Notice Lukaku has his hips set a little bit lower and his body in alignment whereas Luperto is twisting at the hips as he desperately tries to hold off his aggressor.

It’s a brilliantly executed, technically sound move from Lukaku. The initial half-step advantage of Luperto seemed by design intending to spin him centrally and physically engage before the Crotone defender could recover his balance. Lukaku’s build-up to that engagement, setting up the physical encounter was brilliantly done.

While it’s not a finesse approach, it’s a highly intelligent one and something each complete forward should have in their toolbox, obviously to varying degrees. If there is a trend among the complete attackers, it’s the way they use their movements to manipulate the opponents in direct attacking scenarios. Again, these players are capable of dropping in and of playing more of a fox in the box roll, but they’re so wonderfully dynamic that the examples really had to showcase the talents that make them so dangerous.

The poachers

Moving to the final group of players, we have our poachers. The point of emphasis here is the quality of the work these players do within the tight confines of the penalty box. It doesn’t matter who these three play against, the type of defensive block or the game state, these three are masters of box movement and execution.

Jumping right into it, the first topic to address is dismarking in the box. Though you can still make the case for Ronaldo, Lewandowski is as good as they get. The Bayern Munich striker is incredibly difficult to track in the box. He just seems to pop out at the right time, in the right place. Part of that is down to the fact that he is a very optimistic forward, willing to follow up on any shot or make runs in anticipation of an opponent’s mistake. A forward’s optimism alone will guarantee a 20% increase in goals.

But it’s not his optimistic approach that we will highlight in this analysis. Rather, it’s his ability to dismark in the box. He’s one of those players where, when he scores, you watch the replays over and over again in an attempt to figure out who was responsible for marking him in the box. He always seems to be free, which is difficult to explain given that he’s the person teams pay extra attention to, at least initially.

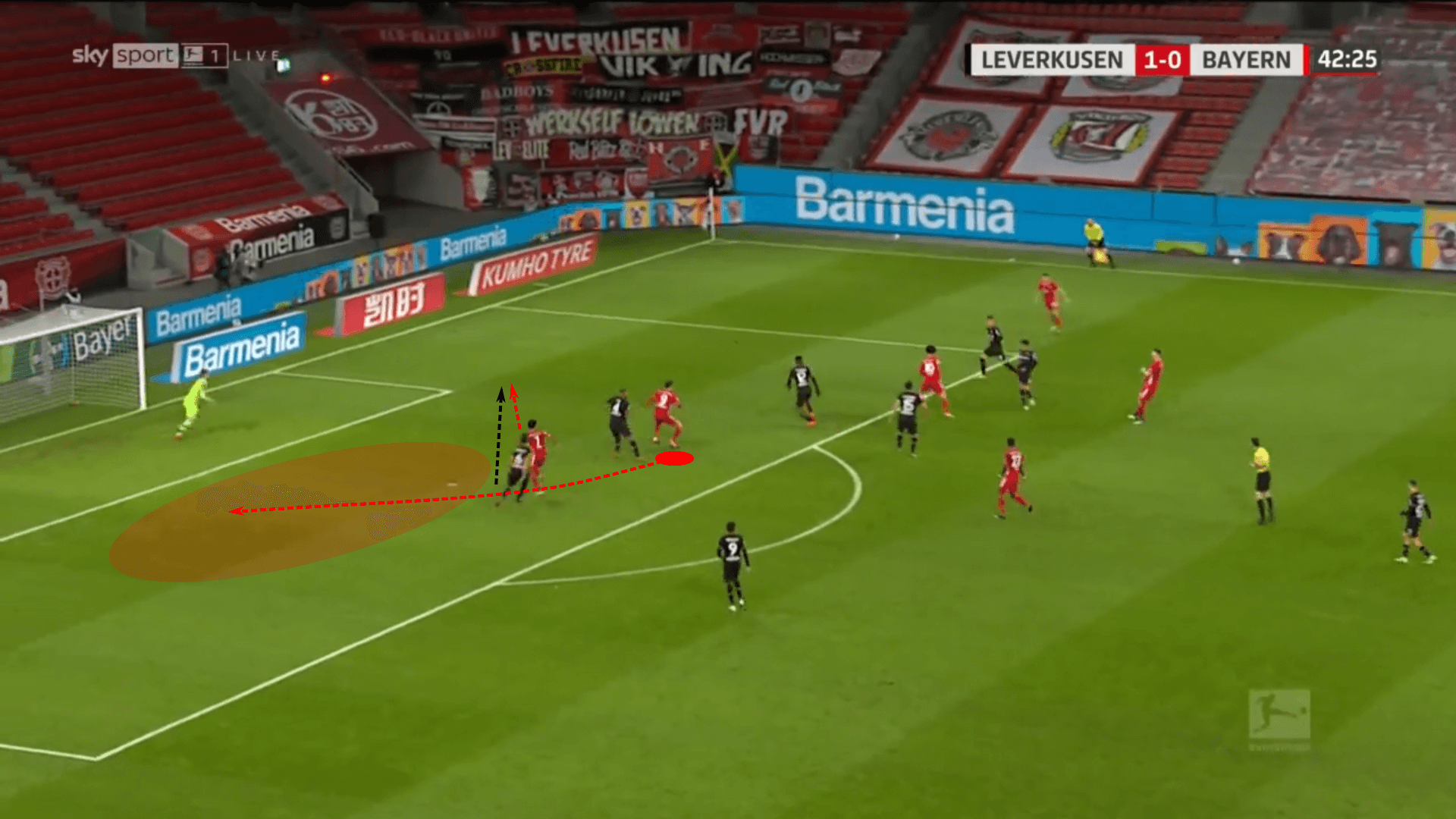

Dismarking in the box is really difficult to show in picture form because there are typically several sequences leading to a successful attempt. However, the first image from Bayer Leverkusen vs Bayern Munich offers a simplified visual. As Bayern looks into the box, Lewandowski has the inside track on his defender and is prepared to receive the ball at his feet. However, the pass does not arrive, forcing Bayern to find a Plan B. In the image, you can see Leroy Sané making a run from the centre of the box towards the corner of the six. On film, Lewandowski catches Sané’s run on a quick shoulder check, then notices the far post is unopposed. With his defender focused intently on the ball, Lewandowski peels away.

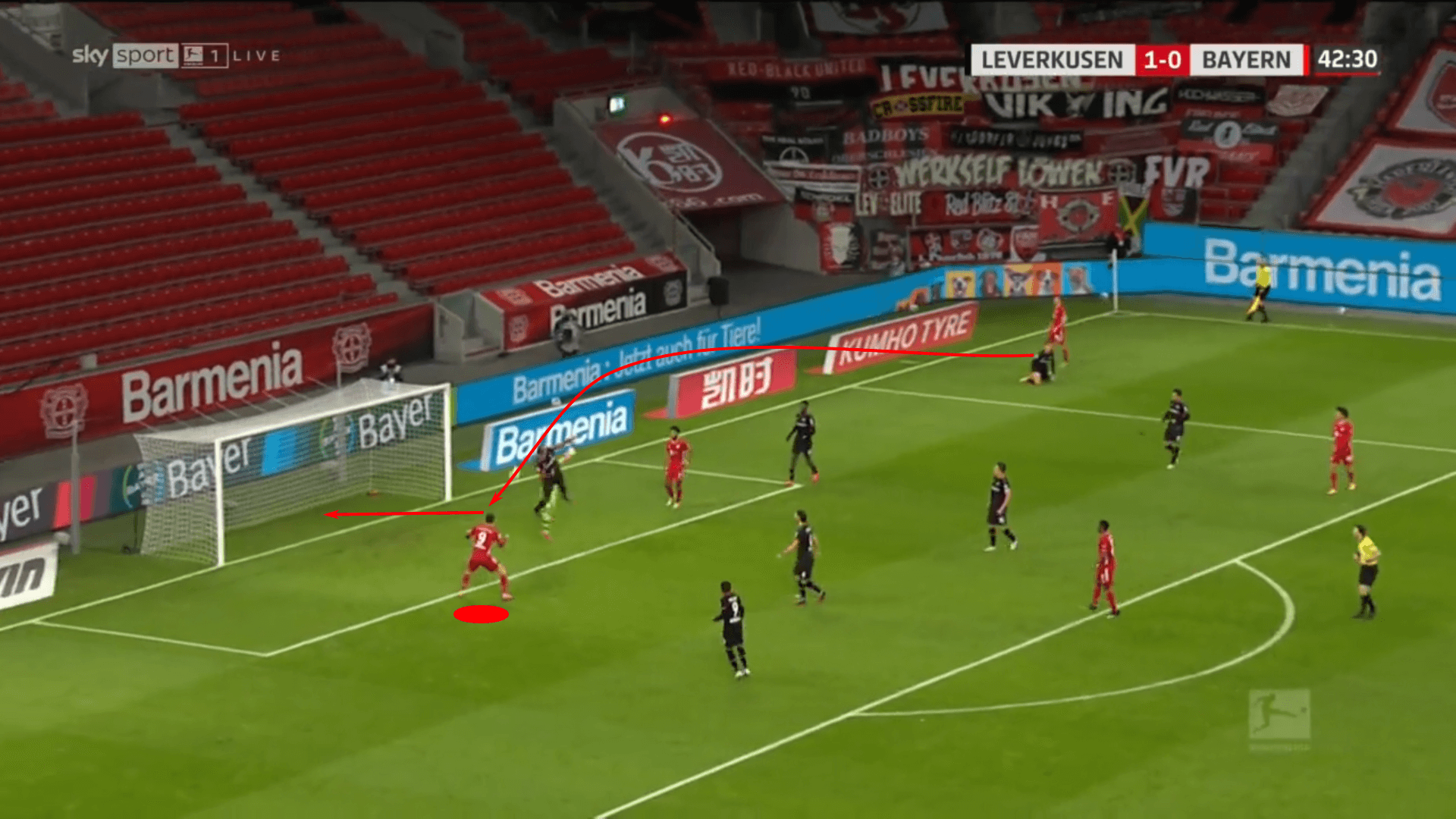

When the cross is sent, a nice ball paired with a terrible miscommunication at the back gives Lewandowski a simple headed finish into an open goal.

The movement itself wasn’t complicated, but his awareness of Sané’s run, the ball-watching focus of his defender and the subtlety of his movement produce this simple finish. Consider this…how many players would have remained central and contested the goalkeeper and centre-back for the header rather than drifting to the far post for the simple, uncontested finish? There’s beauty in simplicity, and goals too.

Speaking of goals, we’ve waited long enough to see an example featuring football’s all-time leading goalscorer, Cristiano Ronaldo. He is the player representative and the tactical concept is timing.

If Lewandowski is the best in the world at finding uncontested pockets of space to finish in the box, Ronaldo is the best at timing his movements to beat defenders at the last possible moment. You’ll need about 20 pairs of hands to count the number of times a defender has looked on in a state of shock as he saw Ronaldo burst in front of or over him for the finish. If you’ve watched Ronaldo in “Tested to the Limit,” you’re aware that he can track the trajectory of the ball based simply on the information he receives from his teammate’s approach and strike. Those visual cues give him the information he needs for the where and when of the run.

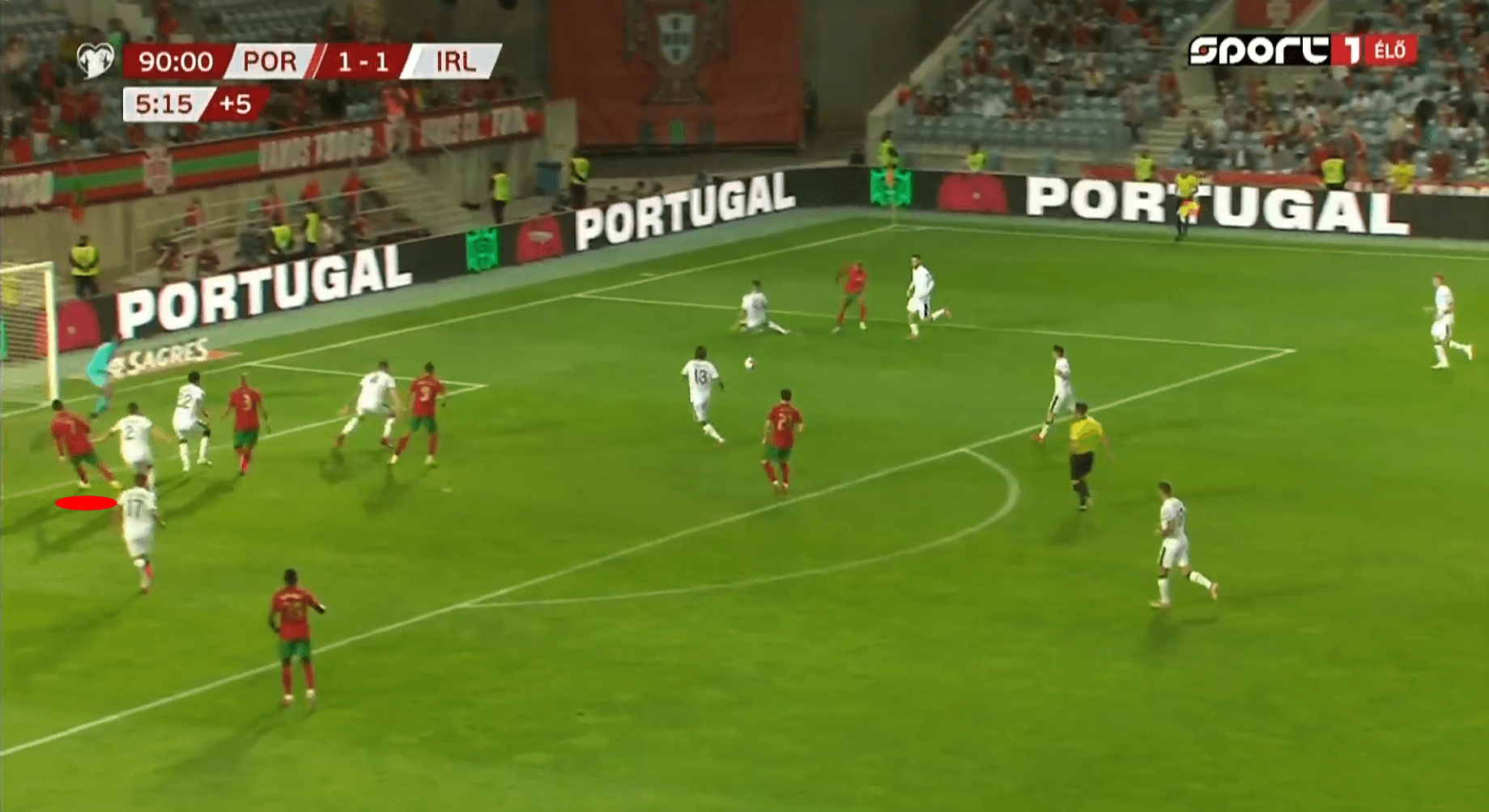

In Portugal’s recent match against Ireland, A Seleção were desperate for a late winner to keep them level on points with Serbia in World Cup qualifying. In the first image of the sequence, Ronaldo has a step on his defender in anticipation of an early cross. Based on the location of the crosser and the space available in the six, he believed there was an opportunity for a low, driven ball across the goalmouth. The initial cross was blocked, so Portugal regrouped.

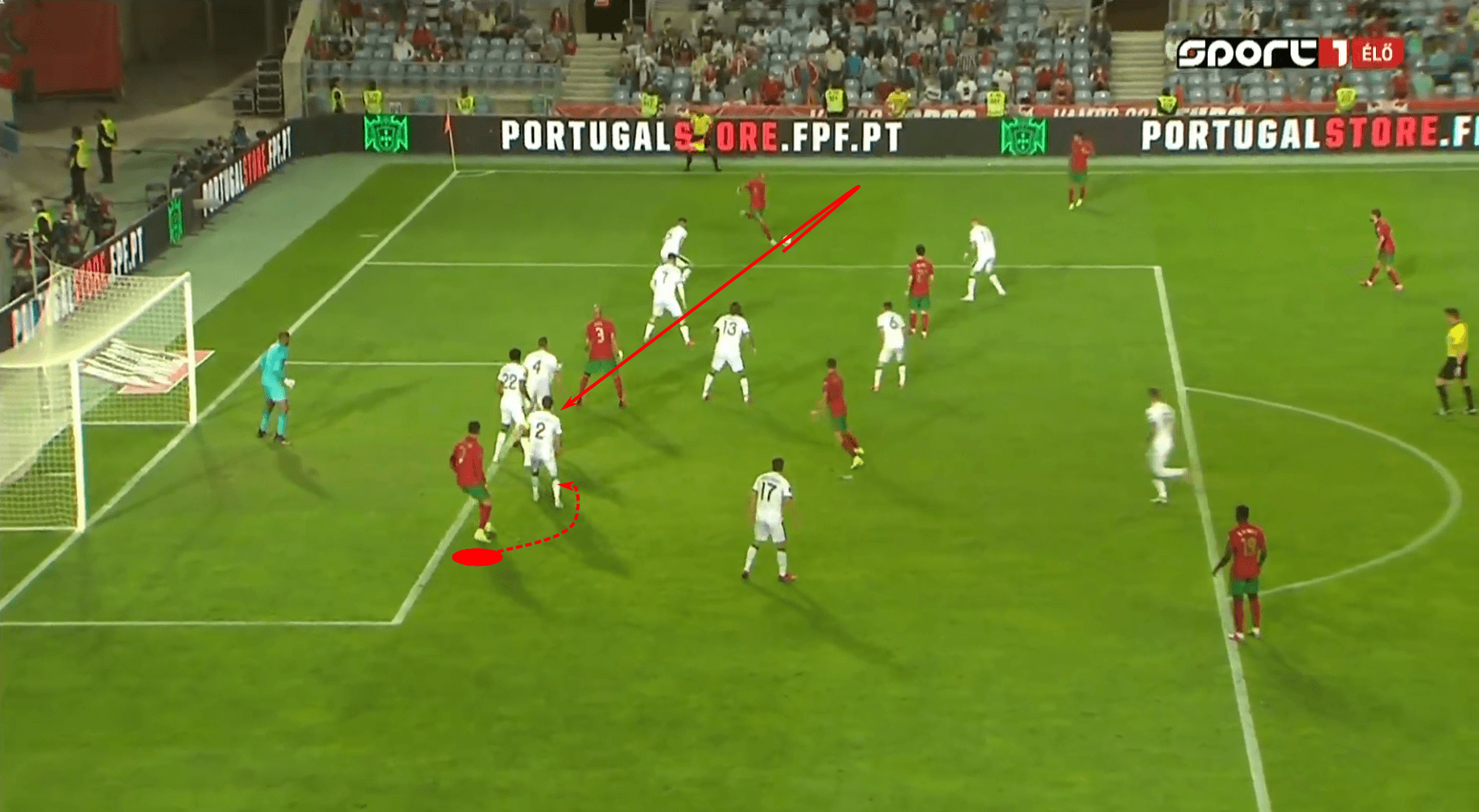

The ball returned out wide to João Mário. As Ronaldo recovered his position, he ventured outside of his opponent’s line of vision. Not only is there an advantage of blindside positioning, but he also offers a far post aerial threat against a backpedalling defender and he can keep play in front of him. Overall, his positioning is excellent, especially when you consider the quickness and timing of his move from the blindspot to cutting in front of the defender.

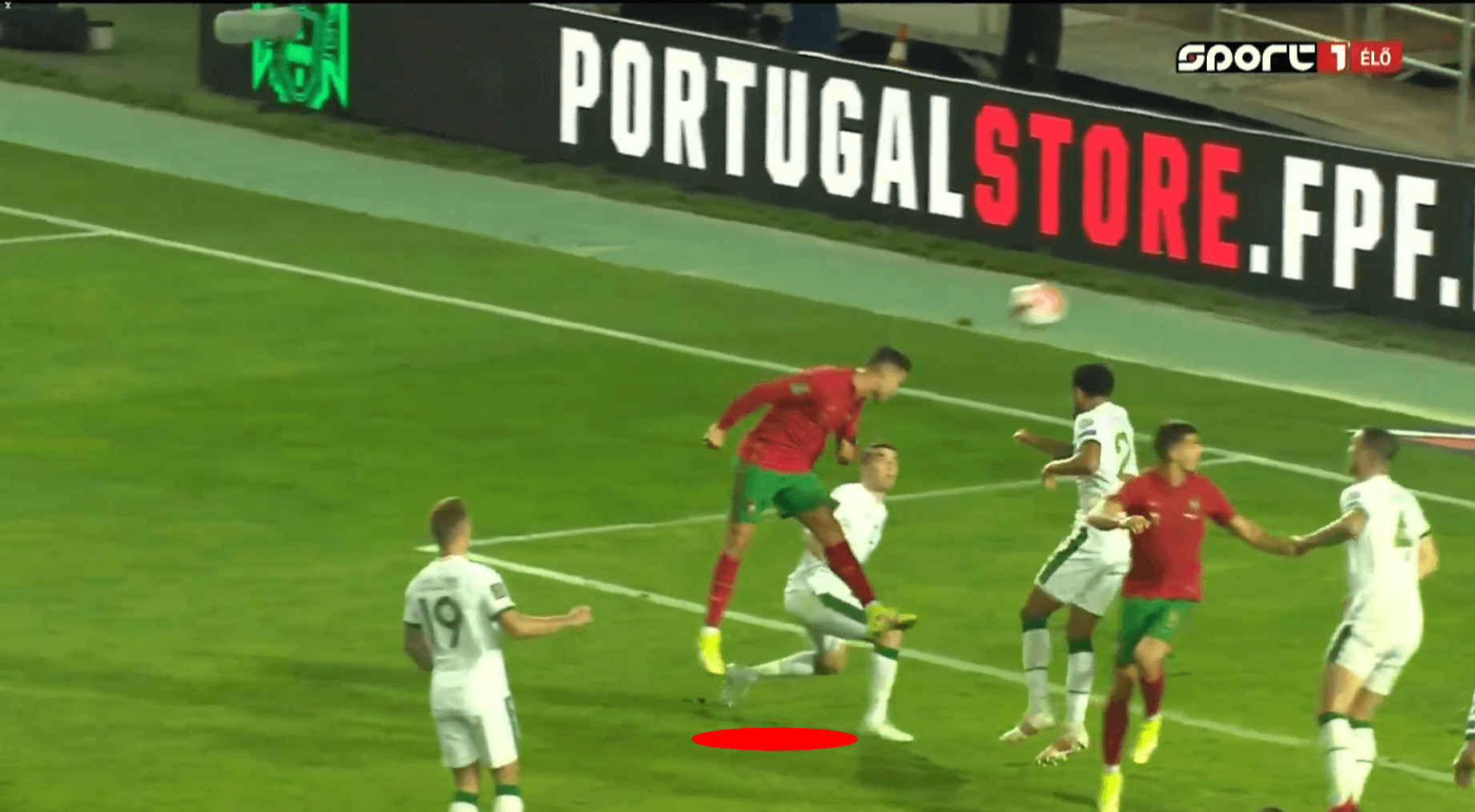

The second image in the sequence shows this positioning as the ball is struck and the third image identifies his location as he heads home the game-winner with the last touch of the game. If there’s any one aspect of the third image that portrays the excellence of Ronaldo’s timing, it’s the look on Séamus Coleman’s face. You can see the surprise, the fear and his understanding that he’s at Ronaldo’s mercy. With that heading technique, Irish hope immediately vanished.

The complexity of timing is that it requires an awareness of one’s physical and technical abilities, then adapting them to the context of the present. That level of awareness and decision making are difficult to train, but they’re also standard in the elite performers. In this circumstance, Ronaldo had a clear understanding of where he needed to go and the necessary time to arrive at the perfect moment.

Timing is the top concept from the Ronaldo example, but “the where” is equally important. The Portuguese gives us a brilliant example of determining the where of the run, but this analysis will end with an example with the player who is last on the list alphabetically, Zlatan Ibrahimović.

The final concept in this tactical analysis is the importance of positioning relative to the defender. In some instances, like the Lewandowski one, he adapted his positioning to open into the space behind the defender. There was lots of space at the far post, his positioning was uncontested and Bayern had the ability to hit the far target. In that instance, having the outside track to goal makes perfect sense.

In our Ibrahimović example, We see the importance of gaining the inside track. In most instances this is the positioning top forwards will target. By beating the defender to the inside, they reduce the odds of the defender clearing the ball or at least interfering with the delivery in some way. Typically, if a forward chooses the outside track, it’s because there’s lots of space. When space is tighter or the attacker has to move towards goal with the direction of the crosser to beat the defender to the ball, the player to the inside typically holds the advantage.

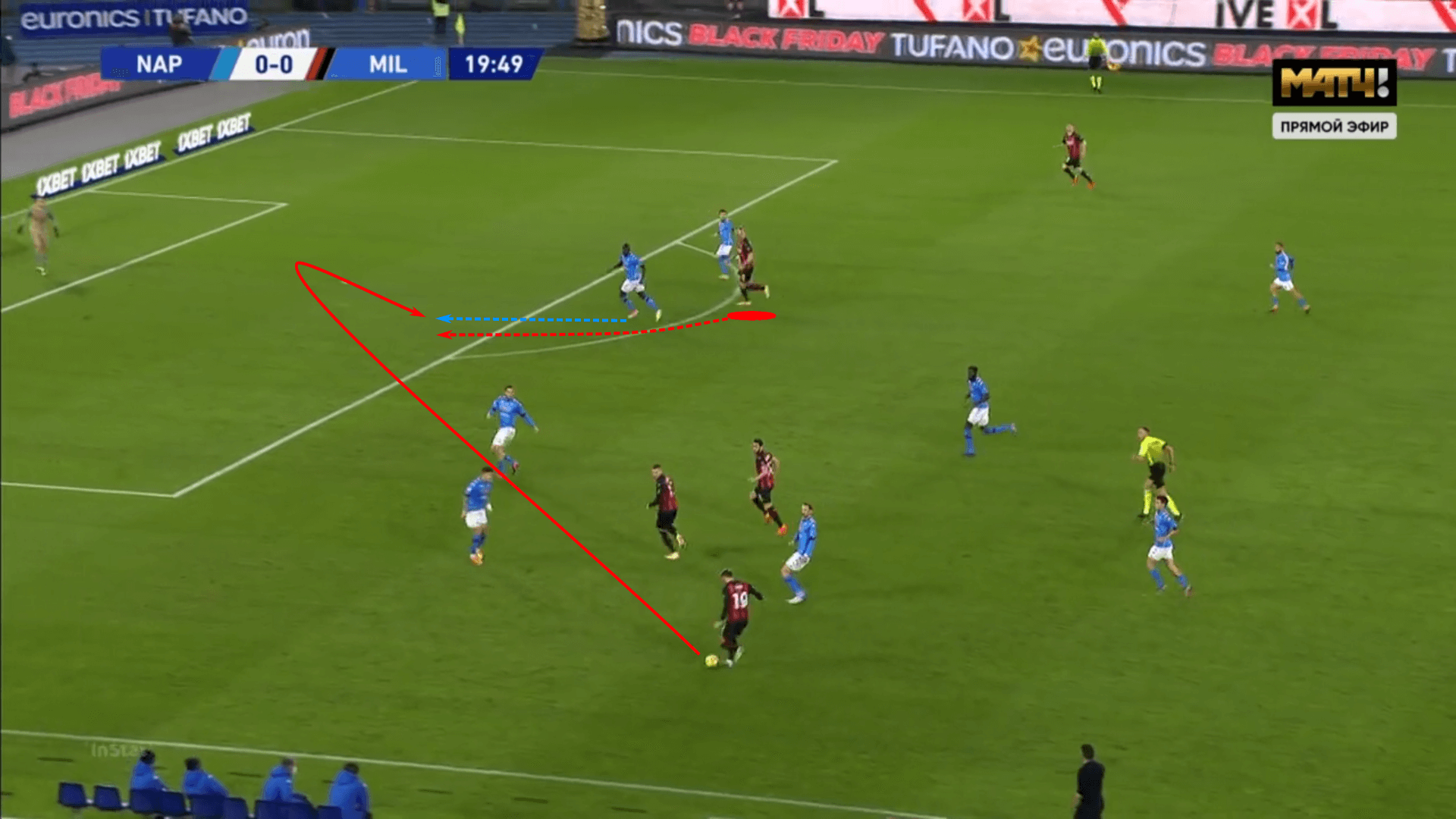

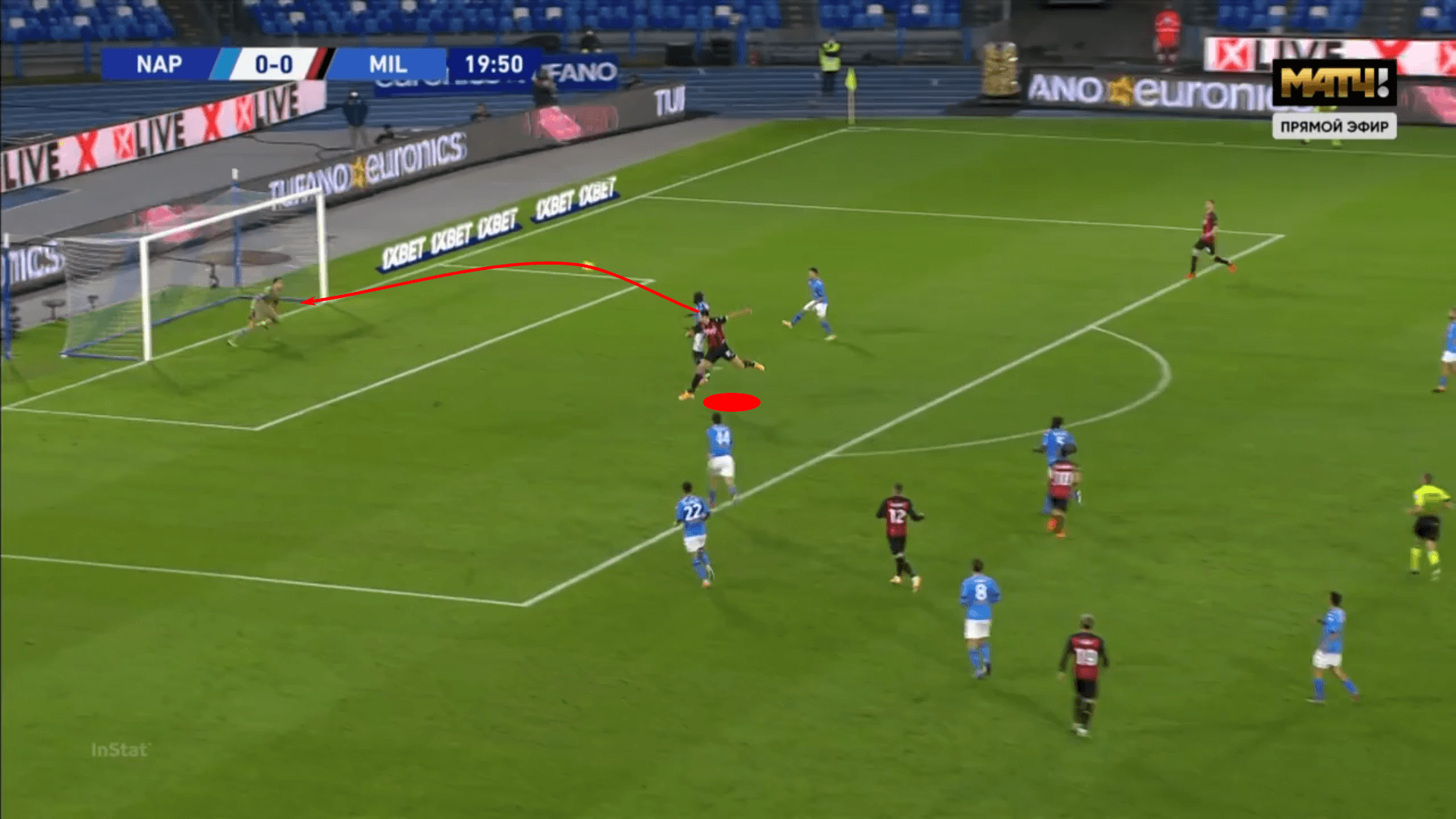

When Napoli hosted AC Milan, we had the opportunity to watch Ibrahimović match up directly against Kalidou Koulibaly. Though the Swede holds a 4-in height advantage over the Senegalese centre-back, Koulibaly’s strength and aerial ability put Ibrahimović to the test. As the cross was whipped in, the two superstars took the preparation steps for their aerial encounter.

Ibrahimović is outjumped by Koulibaly on the play, but his ball-near positioning in the aerial duel leads to an AC Milan opening goal. Establishing position on the inside track was the catalyst for this goal. The run was well-timed but had he contested on the far side of Koulibaly, the Napoli defender would surely have claimed the aerial duel win.

Within the tight confines of the box, attackers have so little freedom of movement to ensure their highest possibility of success. It’s the small details, such as the dismarking tactics of Lewandowski, the timing of Ronaldo’s movements and Ibrahimović’s determined runs to establish positioning on the inside of the defender that produce opportunities. There’s still the need to finish off the play with the appropriate strike, but the work these elite attackers put in beforehand is what separates them from the pack.

Conclusion

Three types of positional roles, 10 elite strikers and nearly 5k words later, my hope is that you’ve walked away from this analysis with ideas for implementation. Whether you are a fellow coach or a player, watching the movements of the game’s elite players is an education. The patterns and nuances of their actions are excellent sources for developing the small tactical details. This extraordinarily high level of football IQ is part of what drives our love and interest in the game.

They say the game is the best teacher. Watching the way the best players engage the game, then implementing the ideas lends some clarity to the concept. We’ve long known that Mbappé studied Ronaldo’s movements intensely, and it shows. His game intelligence and awareness of the individual battles that occur within the big picture is testimony to his studying habits.

Given the level of access we have to the game, it’s the youngsters who know how to watch the game and what cues to look for who hold a distinct developmental advantage moving forward. They get to see the movements of football’s elite attackers on a weekly basis, often multiple times a week.

My bold claim for this tactical theory article is that the importance of analysis has only just begun. As access to the game continues to grow, we’ll find that top players and coaches are becoming more thorough students of the game. The best way to do that is to watch the game itself, especially the best in the craft as they leave signs of their elite understanding of the game.

Comments