Here we go, article #3 in the intelligent movements series.

Having written, “Tactical theory: the intelligent movements of elite attackers,” for the October magazine and last month’s tactical analysis, “Tactical theory: the intelligent movements of elite midfielder,” it’s time to drop deeper down the pitch to analyse the backline.

Much like the midfielders article, this analysis is broken into positional roles. The last line of defence (minus keepers), centrebacks and the first up. We’ll examine the attacking and defensive movements of top 4s and 5s, both on the ball and off of it.

We’ll then move on to outside-backs with a section split between the attacking and defensive movements of top players. The role has evolved into an attack-first position, but we still want to see how the game’s best respond in critical moments.

Centrebacks

“If I have to make a tackle then I have already made a mistake.” – Paolo Maldini

We can argue all we want about Maldini’s claim, I don’t think that’s always the case, but there is the underlying principle that a centreback’s duties include directing the team’s defensive structure, sealing access to the central parts of the pitch and understanding the likelihood of where the ball will go next in order to make a play on it through an Interception. Then again, The Sun’s analysis of Maldini’s career claimed he “averaged only 0.56 challenges per game,” which is such an extraordinarily low number it’s difficult to even fathom. Maybe he’s right after all.

If a centreback knows where the next pass is going, odds are they can pick up the second and third as too. Well structured defensive presses should funnel play into pressing traps, limiting the number of outcomes for the second and third ball. If that organization is intact, outcomes are much more predictable. And that’s ultimately the objective of the out of possession team; make play predictable through your defensive organization. Restrict access to one part of the pitch in order to funnel play into another. Once play is funnelled into the desired area, the team picks up their pressure on the ball carrier. That, in turn, will often limit the opponent to short and Intermediate passing options.

In most cases, there are anywhere from one to three realistic passing options. The attacker’s body orientation offers information for that next pass, as do the recovery runs of the out of possession team. With those options limited, the goals are to not be beaten by a moment of individual brilliance and to challenge for an Interception on that next pass. It’s not always taking the ball off the first attacker that’s the priority or objective. Many times, it’s the pass from the first attacker to a second attacker that intelligent players will contest.

It’s the ability to quickly analyse one’s reference points and assess the likelihood of the next one to three actions that sets elite defenders apart.

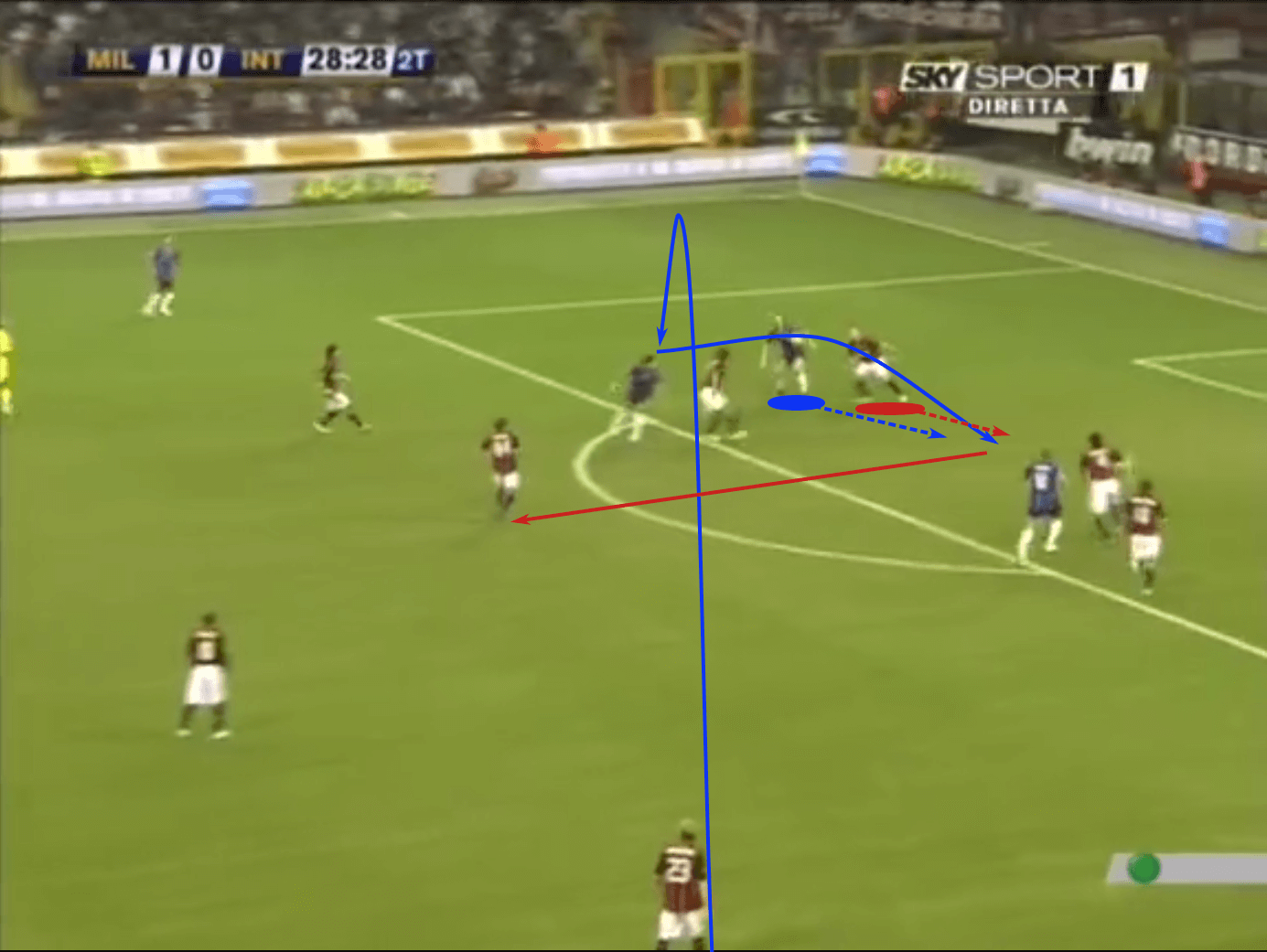

Since Maldini was mentioned at the start of the section, we will turn to him as a reference for the coupling of excellent starting positioning and quickly calculating the likelihood of the next action. Back in 2008, 39-year-old Maldini locked 26-year-old Zlatan Ibrahimovic down in the Derby della Madonnina.

Once you finish reading this article, have a look at the lineups from this match. It was a star-studded affair with the star Swede expected to lead the Inter Milan attack. However, it was Maldini who put on the masterclass, consistently playing two or three steps ahead of Ibrahimovic. Zlatan never had a chance.

Maldini was so good that Ibrahimovic and Inter Milan attempted to avoid the Italian stalwart as much as possible. Finding a sequence or still frame for this article was so difficult because Maldini never had to take extraordinary action. In the sequence, a cross is played in and headed towards the penalty spot. Maldini beats Ibrahimovic to the ball and clears it up field, but let’s examine why it was so easy.

First, notice his starting position. He’s close enough to Ibrahimovic to contest any ball flicked onto the Swede, but he also has the inside track by a couple of yards, which was necessary since Ibrahimovic was significantly quicker than his Italian opponent. The moment the flick is made, Maldini initiates his move and beats the quicker Ibrahimovic to the ball comfortably. Notice his body orientation as well. He can see the ball and his mark and is well-positioned to move either towards Ibrahimovic or towards the penalty spot. His stance is low with his quads activated, ready to move. These are small details, but it’s Maldini’s attention to the little things that made his influence so large.

Centreback can be a difficult position to analyse. It’s one of those where you know what it shouldn’t look like, but it can be difficult to capture what it should look like. Ideally, centrebacks will consistently put in performances like Maldini’s against Inter. There were no extraordinary defensive actions, no last-ditch defending or heroic sacrifices in his box. He did the little things well, so the grandiose actions were unnecessary.

Many battles on the pitch are, first, a battle for positioning, perhaps none more so than aerial duels. While most of the centrebacks in this analysis are 6’2” or taller, we do have an undersized centreback in Sergio Ramos. Granted, 6 ft tall isn’t too great a disadvantage for a centreback, but it means he does have to take care of the minute details.

In aerial duels, Ramos is frequently outmatched by taller centrebacks. In these instances, if he goes into the duel with a positional disadvantage, or even positional neutrality, he’s not going to beat your average centre-forward.

But that’s where the small details come into play. Ramos’ first task, which he routinely wins, is the battle for positioning.

He reads the trajectory of aerial balls extremely well, which is a massive advantage in aerial duels. But that’s not enough. In aerial duels, it’s critical to win the positional battle, which, after the initial read of the ball’s trajectory, becomes a physical duel. Once the destination of the ball is known, the objective is to prevent the opponent from moving into that space. The objective is to contest positioning rather than immediately position oneself for the first ball. By establishing early contact and blocking off the opponent’s access to the ball’s destination, defenders like Ramos increase their chances of an aerial win. Control the opponent to keep control of the space.

When you watch top defenders play, regardless of whether they’re defending a 1v1 or battle in an aerial duel, a common theme is the physical battle before a technical action. Limiting the movement of an opponent and knocking them into an unbalanced stance are actions you will see from the best defensive players.

But not all defensive actions require a physical battle. Remember, Maldini wanted to recover the ball before any such engagement was necessary.

I mentioned we could quibble about whether a defender has made a mistake or not based on whether he is forced into a tackle. At times, a player will slide into a second defender role, offering coverage for the players around him. In the case of the centreback, taking on coverage responsibility often means he becomes the last defender, particularly when covering for another member of the backline. For those of us who are old enough to have either played with or watched sweepers, this is as close as the modern game gets to that role. A centreback covering for either of the two players beside him will drop off into a deeper position so that, as the opponent tries to push the ball past the first defender, the second defender can then step in, transitioning into the new first defender role and, hopefully, claiming a recovery in the process.

In that second defender role, centrebacks have to find that balance between safeguarding the middle of the pitch and offering support to the first defender. If the encounter happens in a central part of the pitch, the stakes are higher, but there’s no need to sacrifice the middle of the pitch. When that engagement comes out wide, the centreback will typically position himself in the near half space, protecting the central part of the pitch while also looking for the visual cue for his move into the wings.

Those visual cues include the first attacker pushing the ball well past the first defender or the pressure defender losing a 1v1 duel. In either instance, there is a need for the centreback to either win the ball or delay the opponent’s attack by offering resistance. Resistance can come in the form of a challenge or even in delaying the attack to allow his teammate to swap roles with him. For an outside-back, this would mean transitioning from that first defender role in the 1v1 duel to now offering coverage to the centreback, taking up a more central position.

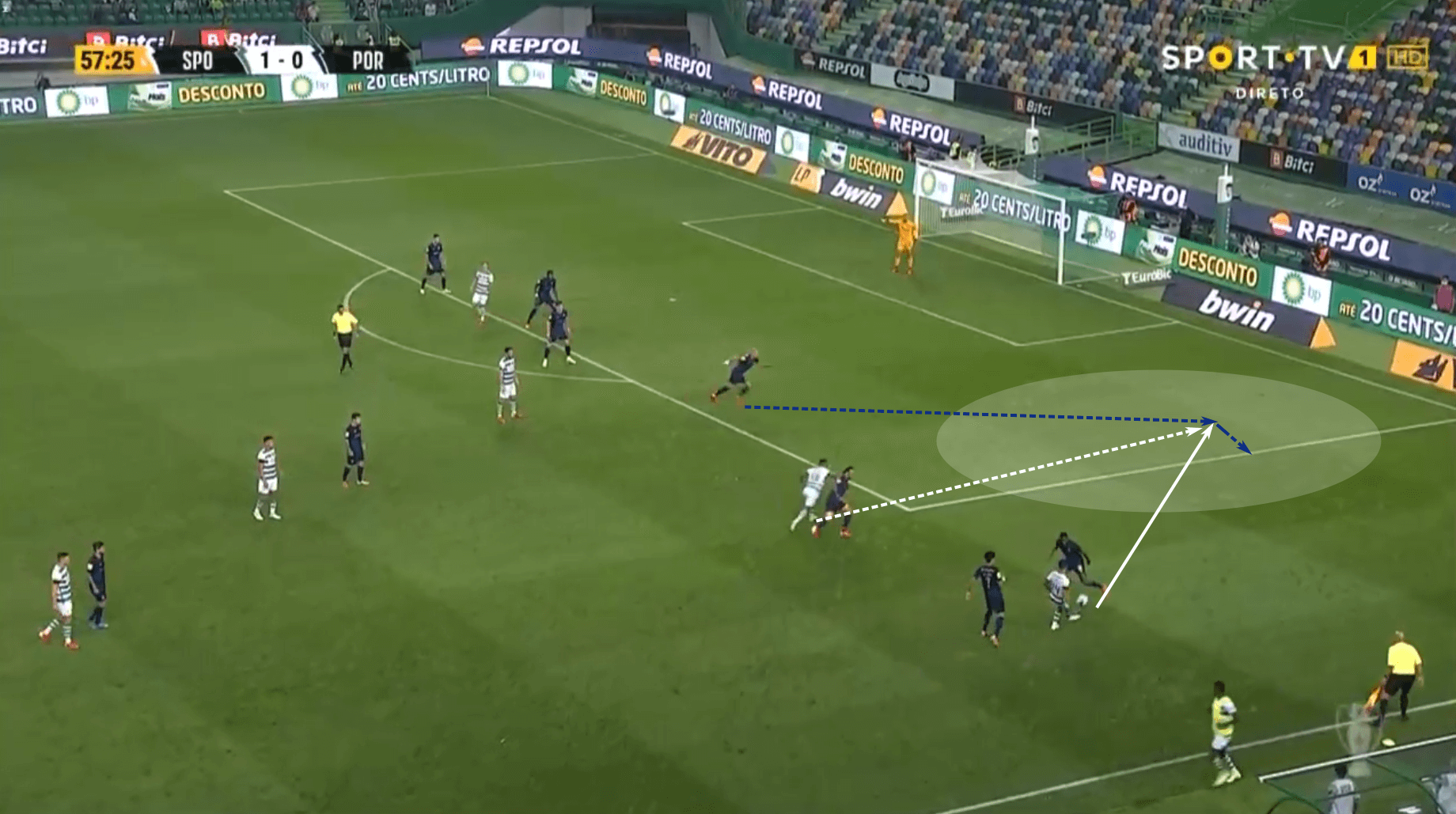

Over the last 20 years, few have carried out these responsibilities as well as Pepe. Whether at the national or club levels, he pairs well with a ball-winning centreback and attack-minded outside-backs. His read of the game and understanding of when to step in is rarely wrong.

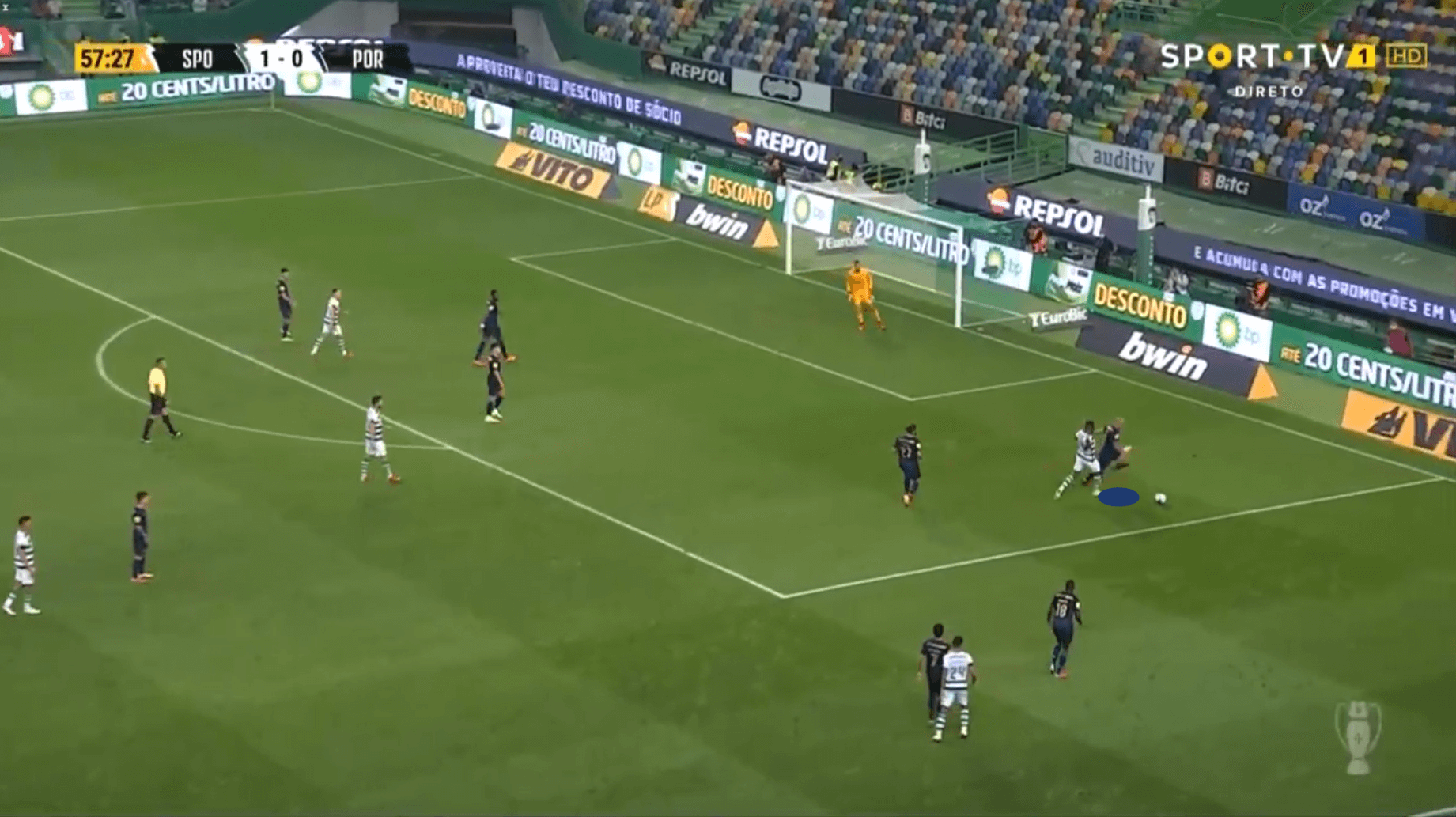

In a recent match against the Primeira Liga champions, Sporting had developed their attack in the right-wing and were looking to make their move into the half space for a cross. The space is there and the run is on, signalling the pass. However, 38-year-old Pepe, who starts the sequence in the central channel, identifies the run and anticipates the pass. Once he knows the pass will be played, he bursts into action, offering coverage in the widest reaches of the half space despite starting the move nearly 20 m away.

Ultimately, he’s successful in claiming the interception and touching the ball around the oncoming Sporting attacker. While safeguarding the central channel, Pepe’s awareness and threat analysis have allowed him to cover his teammates in similar scenarios for nearly two decades. Aggressive defenders like Sergio Ramos and attacking outside-backs are excellent pairs for centrebacks like Pepe who excel in covering for aggressive teammates.

Pepe gives us an excellent example of a player who excels in a coverage role, but what about offering coverage after a complete defensive breakdown? How do top centrebacks use intelligent movements to read the play, assess threats and offer coverage in a chaotic recovery?

Typically when we think of chaotic recoveries, a team like Juventus doesn’t come to mind. They’re well known for their structure and ability to initiate play through their defensive tactics. But in any side, there will be lapses and the need for intelligent recoveries. That’s where we’ll turn to one of the most intelligent centrebacks to ever play the game, Giorgio Chiellini.

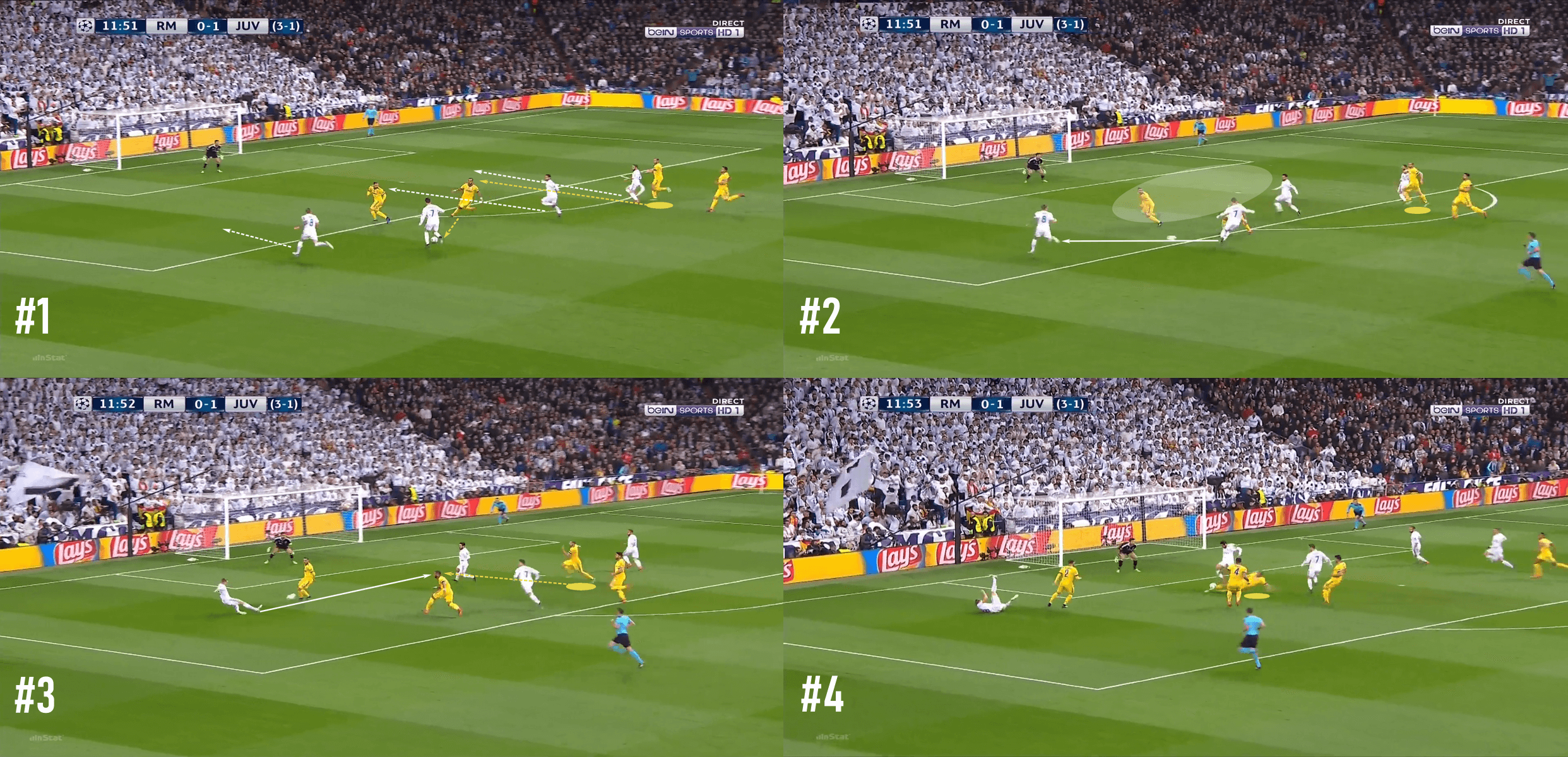

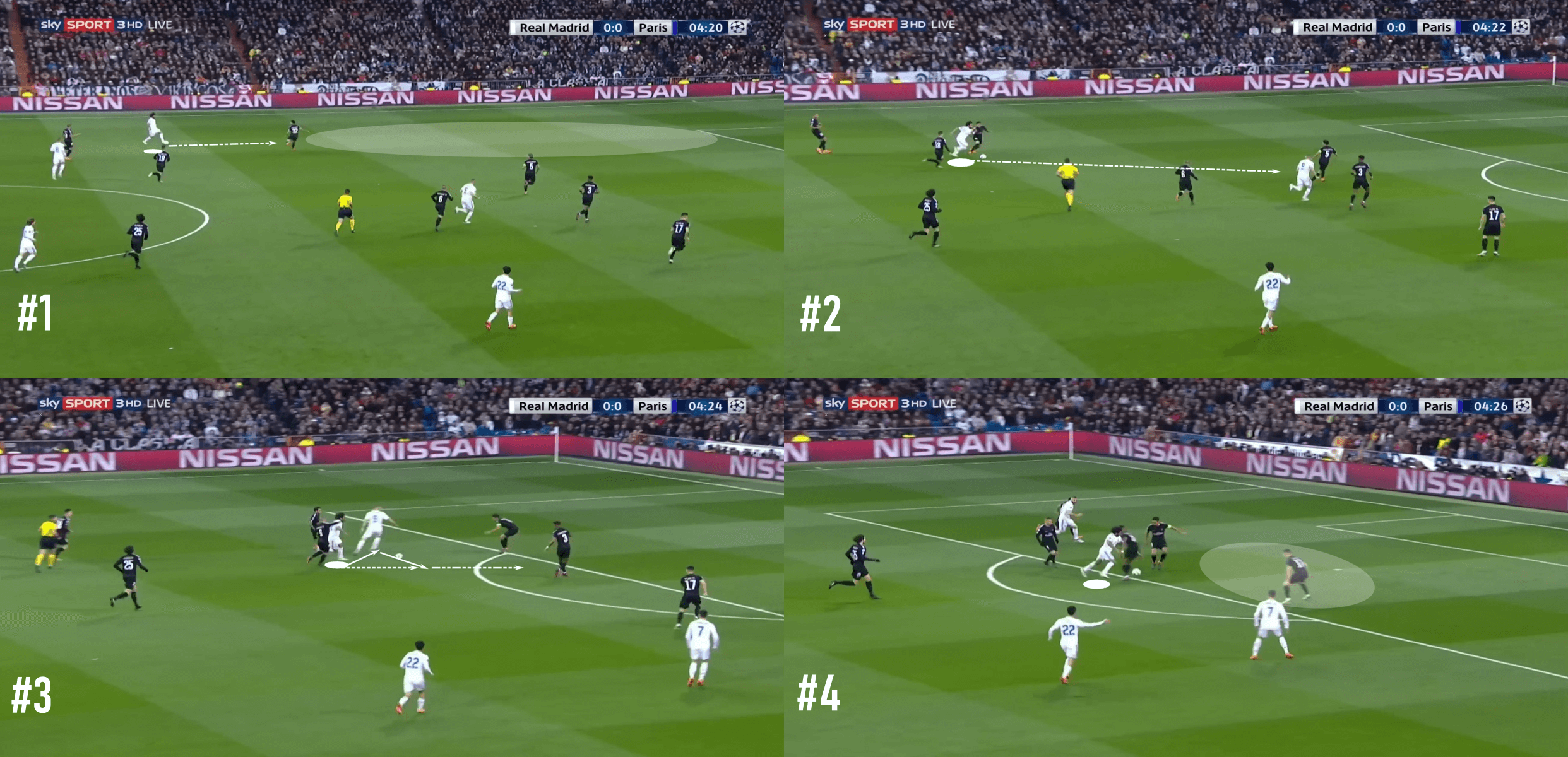

In this example, we again turn to a four image sequence to highlight the intelligence of his movements. When the counterattack starts, he is initially caught up field. As he makes his recovery run, he not only makes his way centrally but also inside of his mark. As Real Madrid nears the box, Juventus reaches their line of resistance, stepping to challenge the ball carrier. As the first defender steps, Isco continues his run into the emerging gap.

Chiellini is quick to recognize the threat. As a ball moves out wide to Kroos, Chiellini finds the perfect balance between eliminating the far post target and positioning himself to contest the pass to the central player, Isco. In the final image, Kroos plays a ball into Isco, who’s in a fantastic shooting position. However, it’s the brilliant coverage of Chiellini that allows him to recover quickly enough to block the shot.

Granted, no team wants to defend in these scenarios on a routine basis, but there will always be a need for intelligent recoveries and engagements either as the first or second defender. Chiellini’s read of play in this instance showcases the intelligence that has allowed him to remain at the top of the position for over a decade.

A defender’s worst nightmare is to have a pacey, agile attacker dribbling at them in the open field with no coverage. A foul results in a red card and if the opponent gets by they are through to goal.

With the contemporary game directing teams tactics to create high central overloads between the lines, we are seeing some of the game’s most athletic and creative players receiving on the half turn with an opportunity to run at the backline. Ideally, defenders will be well-positioned to contest the initial pass. However, this is not always the case.

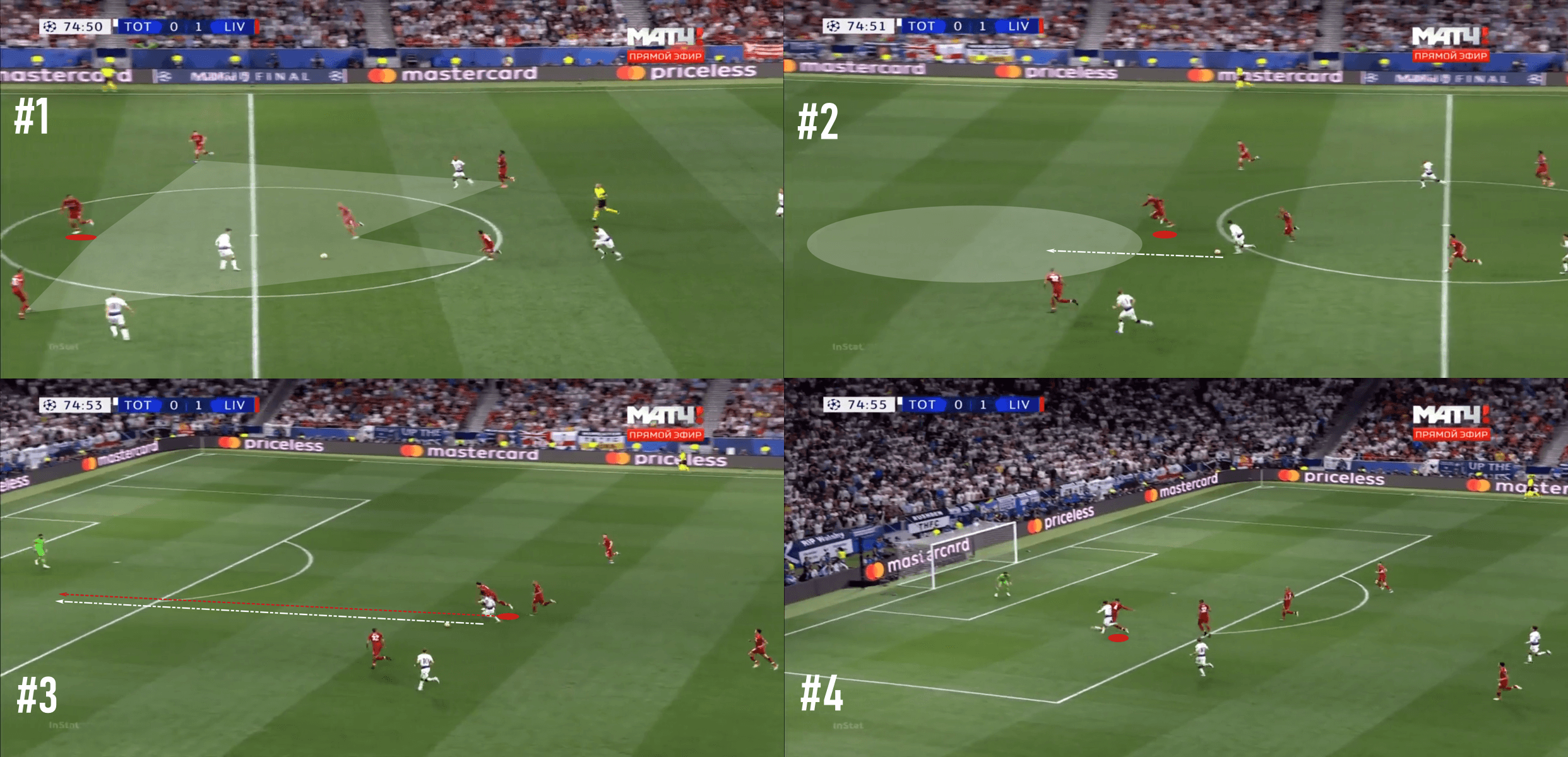

Even elite defenders, like Virgil van Dijk, can get caught in these scenarios, as he did against Tottenham Hotspur. This is a fantastic situation to analyse not only due to VVD’s talent, but also because the attacker is Son Heung-min, one of the EPL’s top attacking talents.

In this four image sequence, we first see the starting position of Son and his distance from both the midfield and defensive lines. Second, his reception on the half turn is an excellent directional touch that allows him to run directly at van Dijk. As the sequence evolves, Van Dijk shows the awareness that he is isolated against the pacey, powerful Son. He wisely gives ground, retreating into depth to limit the space Son can run into.

Third, as Son approaches that moment where he has to make his move, we can already see that Van Dijk has excellent defensive posture and is funnelling the South Korean onto his left foot. Now that Van Dijk knows where Son will attack, the job is to determine when. That third image portrays the moment Son pushes the ball forward, making his move on Van Dijk. Though Son initially gains a step on the Dutch defender, Van Dijk is well-positioned to use his recovery speed, getting an excellent push off to quickly accelerate. In image number 4, as Son is preparing for the shot, he has to decelerate as he approaches the ball, which is where Van Dijk completes his recovery, making up the remaining ground to block the shot.

This is textbook defending. Delay the progression of the attacker, maintain good defensive posture, determine where the opponent can attack, influence when he makes his move and make up the last couple of yards in the recovery as the opponent decelerates for the shot. No need for a rash tackle or to have a stab at the ball. Show patience, force the attacker to make the first move and contain his attacking threat.

For the last centreback topic, let’s move to the attacking side of the ball, particularly is the visual cues they’re looking for during the build-out.

Building out of the back has taken centre stage in the contemporary game. As teams set out in their attack, the build-outs are intended to buy time for the attacking team to get into their more expansive attacking shape while also starting to manipulate the opposition’s defensive shape. In other words, we can say this is the phase where the attacking team is preparing to attack the opponents. The centrebacks play an important role in creating those opportunities and setting the team’s attacking structure.

Some of the simpler points are that centrebacks need to take up deep positions outside of the opposition’s press to ensure teammates can safely play into them and that their first couple of touches are not hotly contested. This point of taking up a starting position outside of the opposition’s press is an important one. By pulling themselves out of the play, dropping to a deeper starting position, centrebacks give themselves ample time on the ball, as well as enough space to maximize their pitch view.

Maximizing their time and space for receiving is the first step. The second is the visual cues they are searching for as the build-out evolves. Teams that build out of the back are attempting to coax the opposition higher up the pitch. As the opposition moves higher, they typically concede space between their lines. The opposition backline doesn’t want to drop off too far, giving the in possesion team space to play in behind, but they’re also trying to strike that balance of staying connected with their midfield line, who in turn are trying to stay connected to the forwards. If the midfield line pushes higher up the pitch and becomes disconnected from the backline, that creates opportunities for the in possession team to break the first two lines of the press with a long pass into the forward line. They will then contest the first ball and position themselves to recover the second.

If the midfield line is well-connected to the backline but doesn’t offer adequate support to the forwards, in possession centrebacks can then play into their midfielders, breaking the first line of the press and forcing the second line to move forward to contest the new first attacker.

These are the visual cues centrebacks are looking for as their teams build out. Elite centrebacks are excellent in identifying the vertical spacing between the opposition’s lines. They’re actively searching for those gaps in the opposition’s press, especially in identifying if the opposing midfield is conceding space between the first and second lines or the second and third lines of the press. With that information, especially from a deeper position with full sight of the pitch, top centrebacks can then pick out the pass that the opposition is giving them.

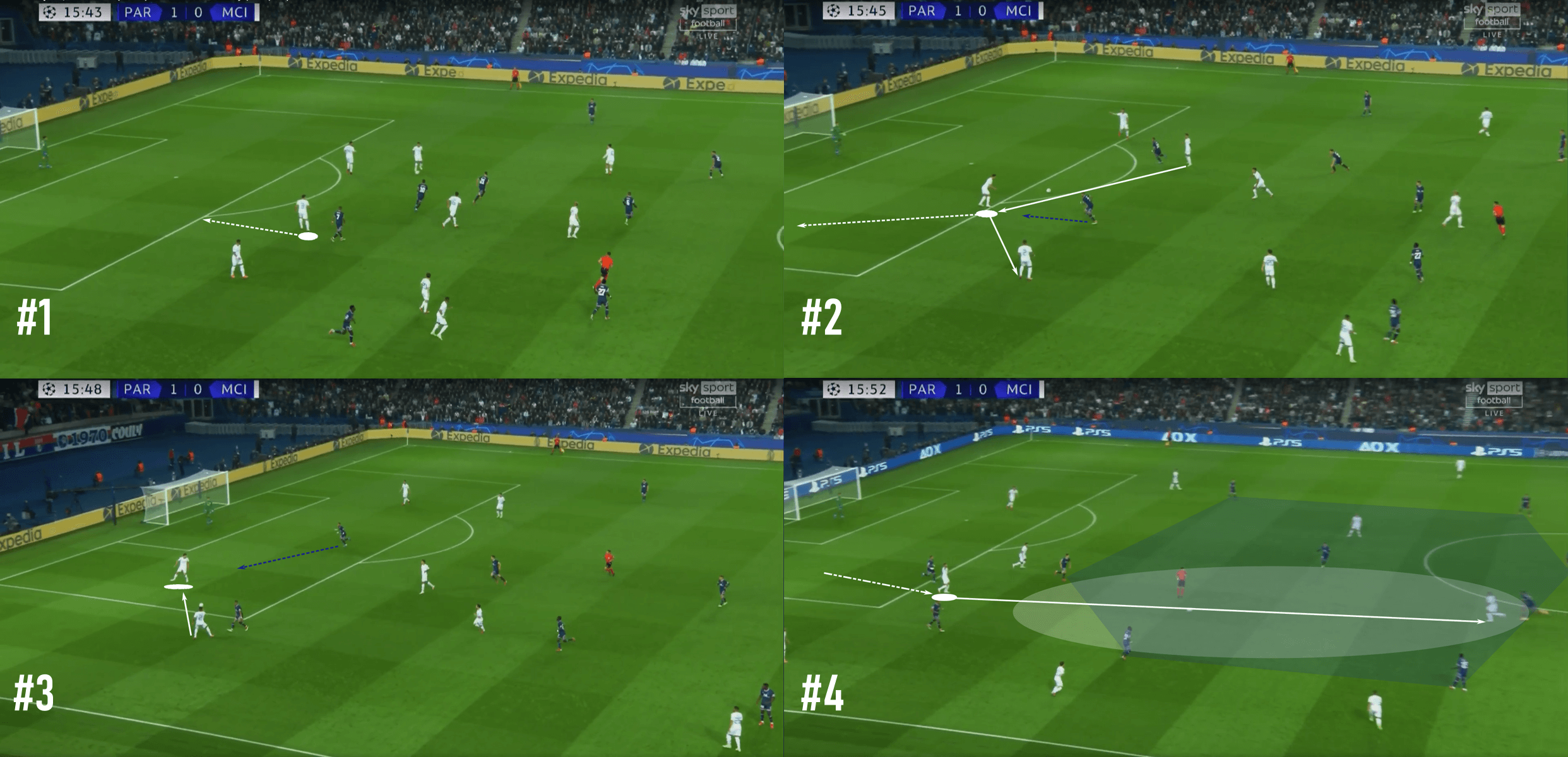

In this sequence, Rúben Dias starts near Kylian Mbappé, then drops deeper as City secure possession. As the ball is played into his feet, he quickly sends it wide, then drops even deeper to offer a return pass.

That pass does eventually arrive at his feet. Notice how disconnected the two forwards are. Dias dribbles right through them, then plays a 30-yard pass on the ground to break the PSG press. With just Marco Verratti between the front and back lines, the pass is a simple one for a player of Dias’ calibre.

Dropping deeper allows centrebacks to see more of the pitch, creates better spatial and temporal conditions for receiving and increases the distance between the opponent’s lines as they step forward to pressure. With those principles in place, they can search for space between the lines, both near and far.

Outside-backs: Attacking

As the game has evolved, perhaps no position has seen such an extreme transformation as outside-back. Watch footage from the pre-Total Football days and you’ll find three and four-man backlines that were stationary at the back. There was little to no attacking support. These players were exclusively defensive stalwarts tasked with shutting down the opposition’s attack.

Fast forward to the current day and you could argue that most outside-backs are average to poor defenders. The role has evolved to the point where they are now attack-first players who are typically the width providers in the team’s system. Unleashing the runs from deep areas allows outside-backs to take advantage of the space afforded them in the wings.

Perhaps no outside-back has embodied this progression better over the past few seasons than Trent Alexander-Arnold. He’s an assist machine with the dangerous delivery into the box, which is closely tied to the way he picks his delivery locations.

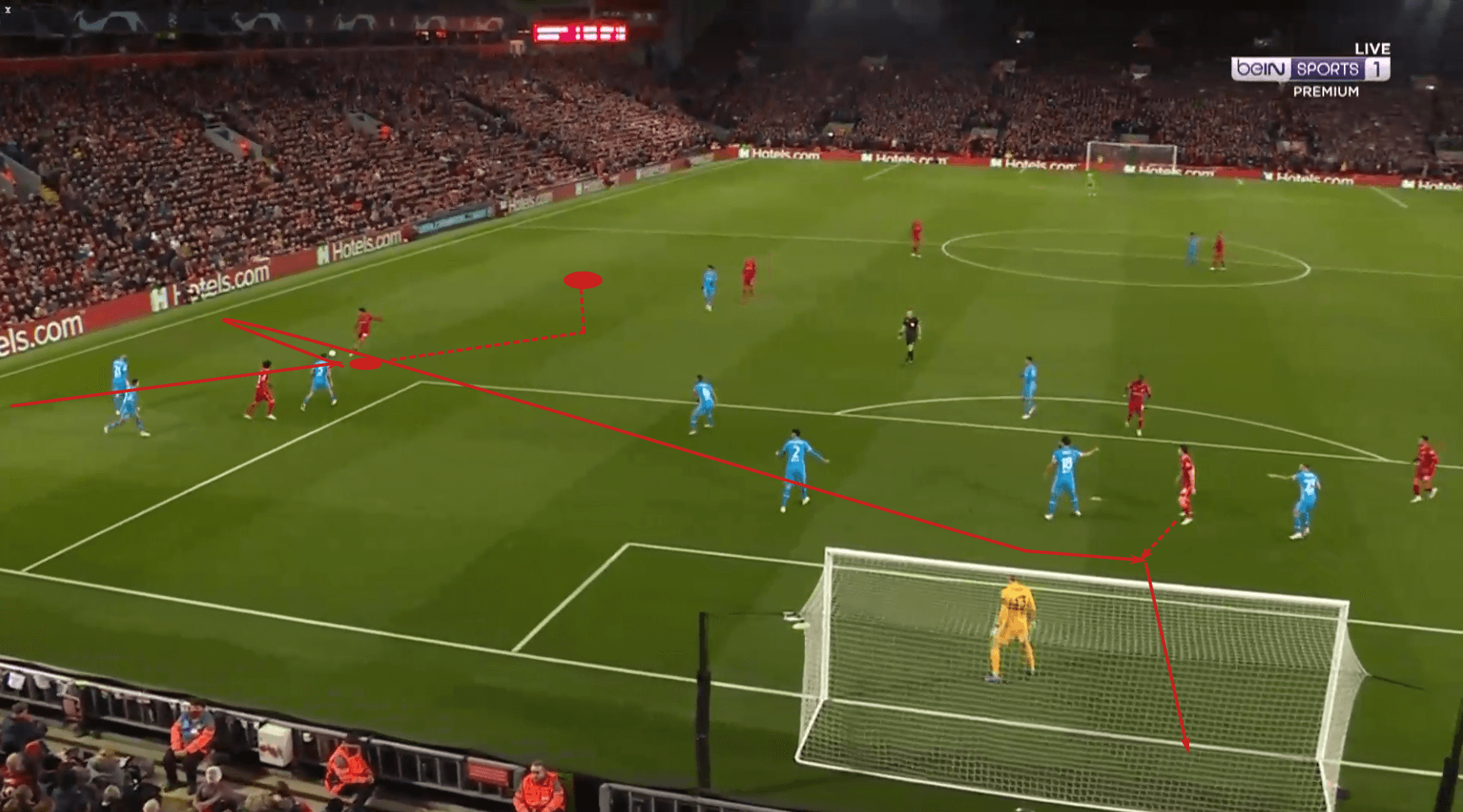

For example, in this sequence, he makes a late run to push into the final third, initially running into the right half space. As the 2v2 gets bogged down out wide, Alexander-Arnold moves it to the wing to offer a better outlet for his teammates to play out of pressure. As he makes his move into the wing, he makes sure that his body orientation allows him to send a first time cross.

Diogo Jota had excellent positioning on the play and easily headed the cross into the goal. Even though Alexander-Arnold has excellent crossing ability, you can see the initial inclination is to underlap and work his way into the half space. Deliveries from the half space are statistically more dangerous than those from the wings, so the initial move is an intelligent one. However, as the play breaks down, moving into the right-wing puts Alexander-Arnold in a position to send the early cross before the opposition can get their shape. Notice that he is still only a few yards away from the half space. Although he moves wider, his positioning is still as far central as he can go while maintaining both the passing lane and preserving the angle of approach for his cross.

Though outside-backs are typically the width providers in the modern game, they don’t necessarily stay in the wings. As we saw with the Alexander-Arnold example, he started in the half space, then moved into the wing for the delivery. Prime Marcelo, who typically had the more central Cristiano Ronaldo in front of him at Real Madrid, was the width provider for Los Blancos, but he was equally dangerous moving inside or staying in the wings, that despite being a one-footed player.

You could argue he was most effective when starting in a wider position and taking an aggressive first touch up the wing. With Marcelo’s dribbling and crossing ability from the wings, opponents were forced to close him down quickly. As they approached, he watched carefully for their overcommitment.

In this four image sequence, we see Marcelo initially receive in the wing, forcing the opposing right-back to step higher as the pressure defender. There’s no coverage in the wing, so the natural inclinations are to rely on the cover defenders centrally or prepare to contest the 1v1 duel in the wing.

However, Marcelo cut inside, splitting the two defenders. As he approached the box, he and Karim Benzema exchanged a give-and-go, putting the ball on Marcelo’s feet as he neared the penalty arc. In the 4th image from the sequence, he draws some contact and loses his footing just enough to turn the ball over as he entered the box. The Brazilian was one or two steps away from completing a marvellous goal which started with a strong cut to the inside.

The general idea here is to maximize the width of the pitch, which then stretches the opposition’s defensive shape horizontally. As they become stretched, the option to attack centrally becomes more realistic. Further, in this Marcelo example, he’s in a position where he can attack either centrally or by continuing in the wing. Those two options allow him to pin his unsure opponent. Caught between two options, the PSG defender was unable to dictate where Marcelo had to attack, so he was forced into a reactive engagement.

Marcelo used his positioning in the wing to create attacking opportunities centrally. However, we do have examples of outside-backs who start in the half spaces, allowing the wide forwards to offer width in the formation. They are called inverted outside-backs. The best example comes from Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City with his niche role for João Cancelo.

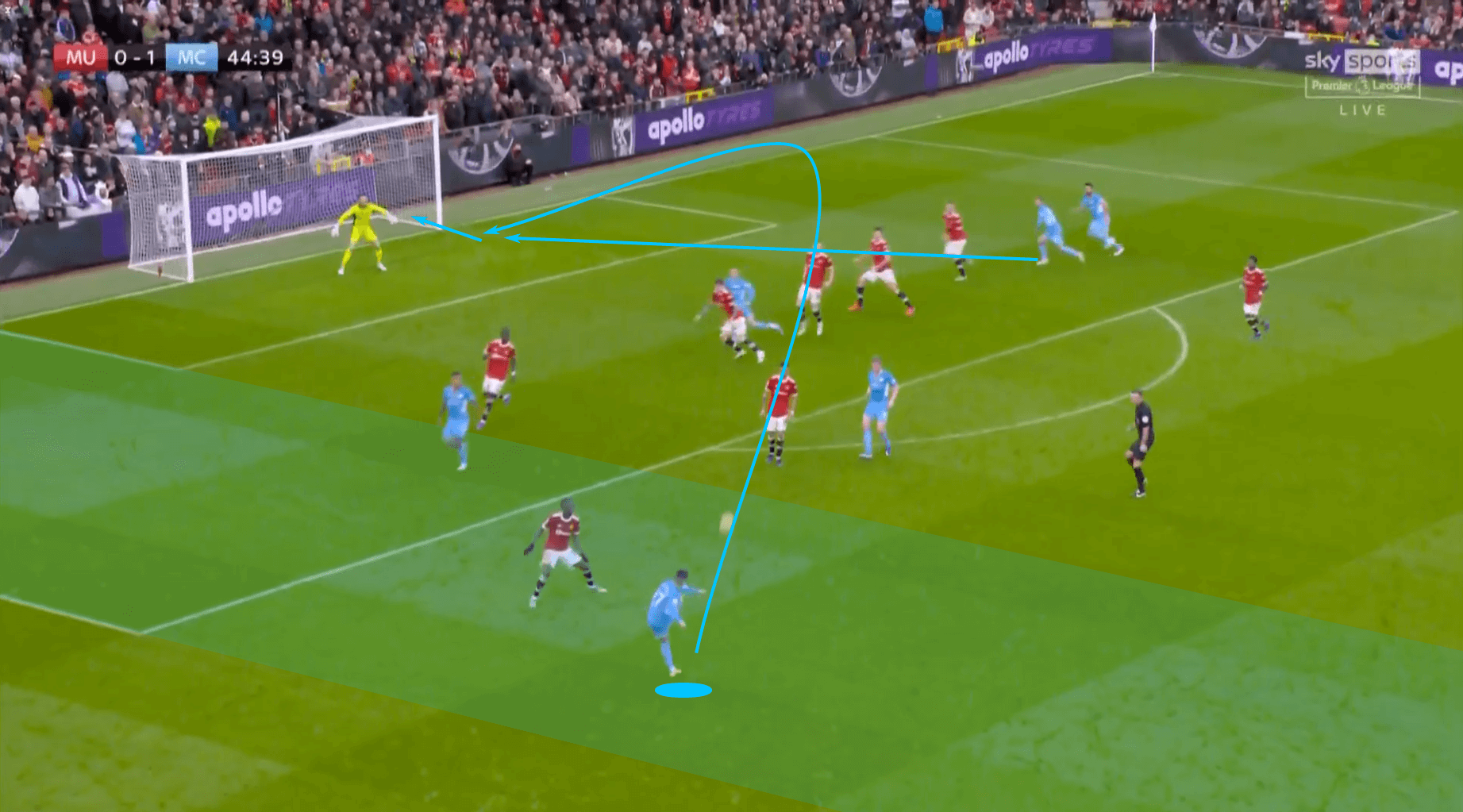

Sliding into the half space allows for direct participation in the early phases of the attack and puts the onus on a top passer like Cancelo to control the tempo, switch the point of attack and position him to play into anyone on the highest line.

The advantage in the final third is undeniable. Rather than sending out swinging crosses from deep in the wing, the right-footed Cancelo is now well-positioned to send in-swinging deliveries to the back post, a nightmare scenario for goalkeepers. That in swinging cross keeps them on their line as they attempt to figure out if the ball is headed on frame or wide of the goal.

Further, as we see in this example from the Manchester Derby, the back post run of Bernardo Silva is untracked, leaving him within a few yards of the goal as he releases his shot. David de Gea parries the ball into the side netting, but he can do little more than offer a reflex redirection from that distance.

As was detailed in the previous article, “Tactical Analysis: The intelligent movements of elite midfielders,” Toni Kroos took a starting position outside of the opposition’s press in the left half space to fully utilize his passing range. From that deep position, he could use his preferred right foot to drive the ball 60 yards across the pitch or hit the shorter distance, but more technically complex, action on the near side.

That’s exactly what we see in the Cancelo example and one of the clear opportunities for wrong-footing outside-backs. Since Cancelo is right-footed, it benefits him to slide centrally, putting the ball on his right foot with an open body orientation.

The additional benefit of an inverted outside-back is Cancelo’s positioning within the Manchester City rest defence. Moving closer to the centre of the pitch, he is well-positioned to intercept or contest outlet passes into the half space. He can also compete for second balls if the opponents attempt to play into a target forward up top.

Finally, there’s the benefit of novelty. Since inverted outside-backs are still a fairly new concept and teams rarely encounter them in matches, it’s difficult to adapt when they play against one.

Outside-backs: Defending

Since we’ve already started the conversation about the defensive contributions of outside-backs in the Cancelo example, let’s transition to the defensive phases of the game. Our objective here is not a full examination of how outside-backs should operate within a given system. Instead, we are looking for intelligent decisions and movements. In instances where an average player might step too high or move too far to his left or his right to cover a threat, how do elite outside-backs distinguish themselves?

Perhaps the most difficult aspect of this section is that we’re dealing with a phase of the game that, at its best, produces predictable decisions and actions from the collective. Whereas attacking tactics are creative, incorporating unpredictable actions to unbalance the opposition, defending in open play stresses the solidity of the unit more so than the actions of any one individual. In this analysis, this was the most difficult section to research.

What I did find was that individuals distinguish themselves in moments of unit breakdowns or in creating a perception of multiple options while effectively giving none.

In our first example, we follow the second description with a sequence centring on Philipp Lahm. The long time Bayern Munich and Germany right-back was an exceptionally intelligent player. In this example, his supporting midfielder, Thomas Müller, is a few steps behind his Borussia Dortmund counterpart. Lahm is faced with a runner moving from the half space into the central channel as well as his own mark who is positioned in the wing. Caught in a difficult predicament, Lahm is effectively responsible for two players in the sequence.

One key is the work of Bastian Schweinsteiger. As his opponent dribbles towards Lahm, Schweinsteiger does well to narrow the passing lane into the central channel. As that lane narrows, Lahm moves a few steps to his right understanding that the lone remaining pass is the one into the wing. Whereas in the first picture there are two passing options, each carrying a significant threat for Borussia Dortmund, Lahm’s initial stillness positioned him to contest the central pass, essentially taking away the option, which left his opponent with just the one remaining.

Since Lahm knows there is only one remaining option and that he’s well-positioned to intercept the pass, it becomes a matter of waiting for the right moment to step higher and claim the ball. He does so, intercepting the pass and restarting Bayern Munich’s attack.

The first example of outside-backs performing their defensive duties within the team’s tactics came in an open attack. This next example, which is the final one in the article, deals with defensive transitions, particularly counterpressing. For this one, we’ll examine the work of Lahm’s former teammate, David Alaba.

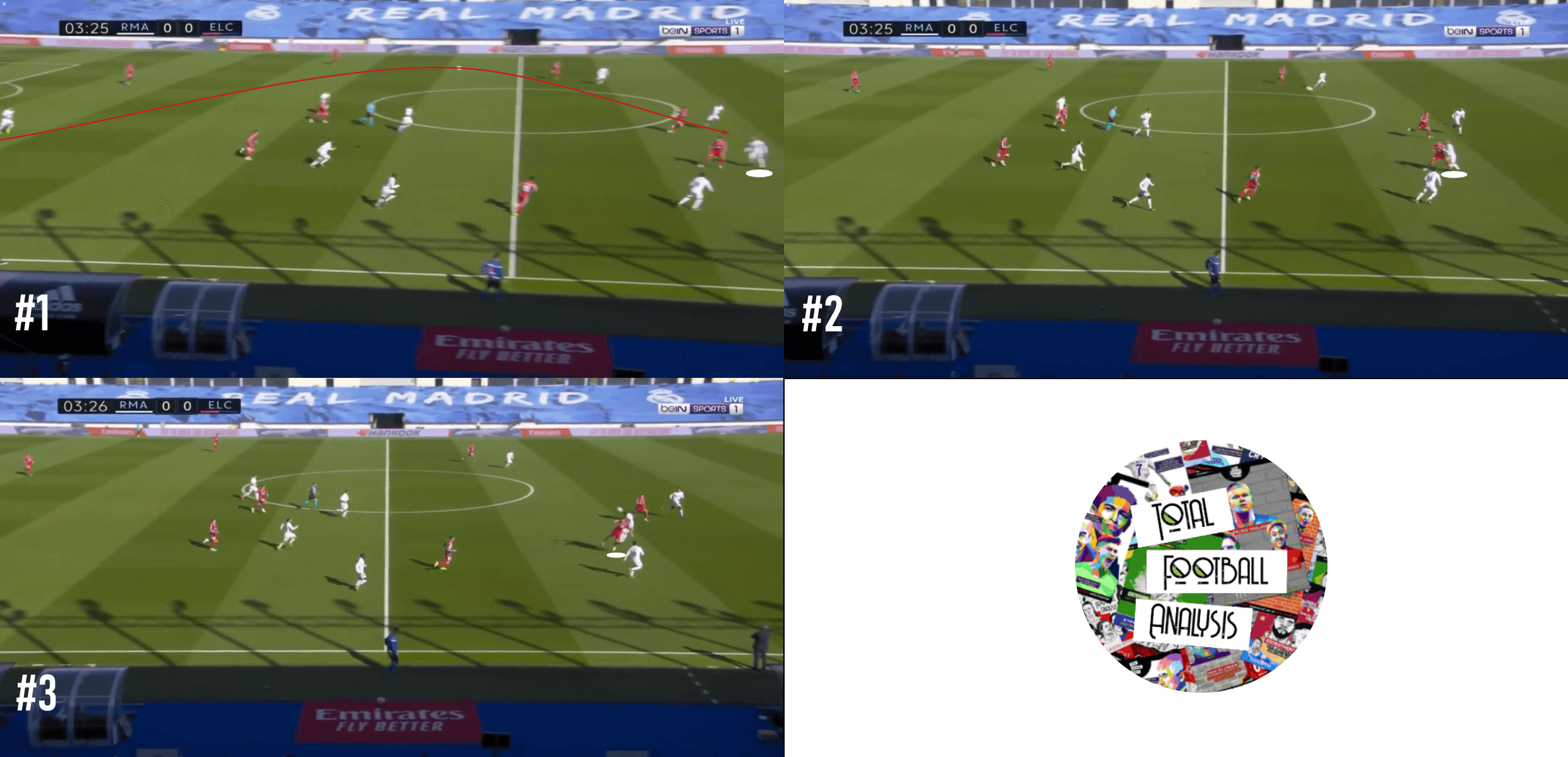

The recent Real Madrid signee has largely played centreback this season, filing a massive personnel void for Los Blancos. However, he has played left-back on a few occasions this season, one of which was against Deportivo Alavés.

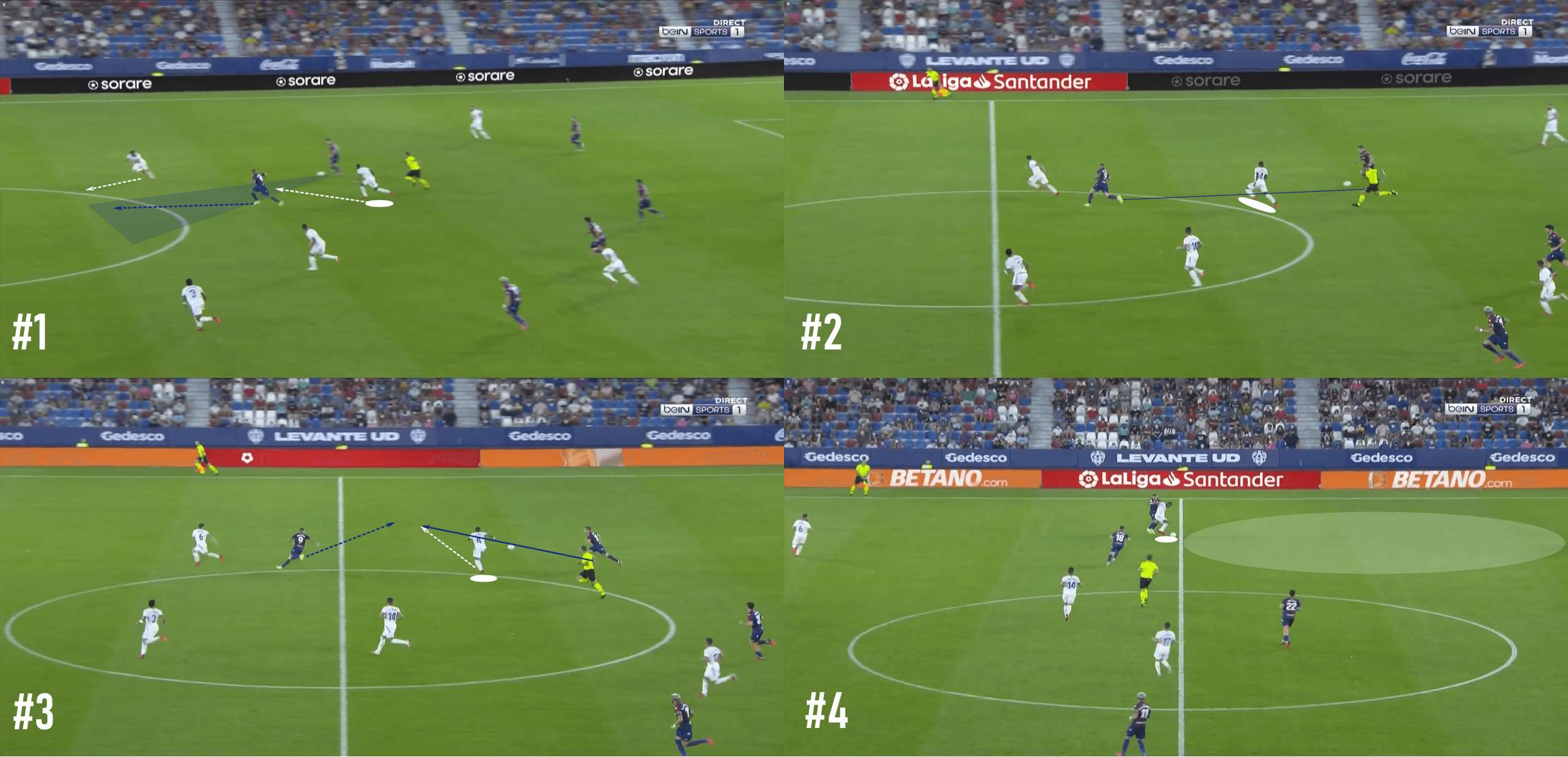

In this example, Real Madrid has just lost the ball and are poorly positioned to deal with the counterattack. In the image, you can see the distance between Éder Militão and Nacho, as well as the space available behind them. That’s where Alaba flies into action.

As Nacho recovers centrally, Alaba’s instinct is not to pressure the first attacker, but to close down the passing lane to the second attacker. In the first image of the sequence, you can see the passing lane that’s initially available. A moment later, Alaba is in the same line as the first and second attackers.

Since he has taken away the passing lane, the result is an awkward strike at the ball to the first attacker’s right. There is certainly a lack of technical execution in the sequence, but that strike is heavily influenced by Alaba’s intelligent and quick recovery. The Austrian is the first one to the mishit ball and is fouled before he has a chance to dribble into the space in front of him.

Two key points here are identifying the top threat and tailoring movement to deny it. There’s no need to pressure the first attacker. Running towards him will only cue him to release the ball sooner. If Alaba were to run directly at him, that passing lane into the central channel would have remained open, especially if the pass was hit sooner.

However, understanding that the pass to the second attacker was more dangerous than the dribble progression of the first attacker, Alaba’s decision making and movement single-handedly ended the threat.

The lesson here is that even in the case of a defensive breakdown, there’s still a need to quickly assess the present threats rather than simply pressuring the first attacker in the hope of taking the ball off of him. Alaba’s intelligent movement shows an excellent understanding and quick threat analysis of the conditions in front of him. His movement isn’t determined simply by the location of the ball, but by the threat of the dangerous runner into the gap between his two teammates. It’s a wonderful example of football IQ in action.

Conclusion

That concludes part three of the intelligent movements of elite players series. An analysis of goalkeeper movements is in consideration, but I haven’t made a decision at the time of writing. This may end as a trilogy.

Fortunately, there are several goalkeepers, current and former, in my immediate network. If a goalkeeper article is feasible, look for it in February 2022 (we’ll start the new year with TFA 22 for 22).

For now, there’s a complete analysis on the intelligent movements of field players. Between the three articles, there are over 15k words on the topic. If you enjoyed this tactical theory piece but haven’t read the first two in the series, you can find the hyperlinks in the intro of this article.

Comments