Last month, I wrote a piece entitled, “Tactical analysis: The intelligent movements of elite attackers.”

This month’s piece is a follow-up, moving deeper down the field to study the game’s top midfielders. These players have an exceptional understanding of the game which is manifest in their movements off the ball.

Through video research and tactical analysis, my goal is to identify which movements help these players dominate the tight confines of the midfield. Given that elite players tend to play for world-class teams that tend to be possession dominant, this analysis is slanted more towards the attacking side of each midfield role than the defensive duties. However, there are some defensive examples, as well as images focusing on the movement mechanics of specific players. This select group of midfielders shows incredible intelligence with their tactical movements, as well as the way they use their body to improve their likelihood of success.

Each section is determined by the specific roles of the midfielders. Taking up the standard #6, #8 and #10 roles, the midfielders studied for this analysis are slotted into those identifiers. Though there is a high degree of variance in the skill sets of the players within each role, as well as differences in the way clubs use their talents, this simple midfield classification helps us to see the possibilities within each role in relation to the area of the pitch where they are most commonly found.

Let’s start with our #6s.

#6 – Muscle and maestros

Perhaps nowhere else in the game is there such a variation in player types as we have at the #6, also known as defensive midfielders. As the section subheading suggests, #6s range from muscular ball winners, like Casemiro, to smaller-framed artists like Andrea Pirlo. There’s also the lanky, intelligent presence of midfielder like Sergio Busquets, as well as the perpetual motion motor of the diminutive N’Golo Kanté, who is also a master of the mental side of the game.

Player profiles vary wildly and each has a unique skill set that makes him so effective. But those talents are always in cooperation with the primary responsibilities of the deepest midfielder. A #6 must remain connected to his centrebacks both in possession and out of it, as well as help the team connect the lines in attack. Among the elite #6s, you’ll also find exceptional leadership skills, particularly in the way they provide structure and directives to the players around them. They are often the minds of the midfield.

For roughly the past seven years, you could argue there’s no better defensive midfielder than Casemiro of Real Madrid. Whether filtering through La Liga or Champions League data, you will find him in the 90th percentile or better in virtually every defensive stat category. He’s an absolute monster out of possession. Much of his success comes down to the intelligence of his starting positions and the actions he induces.

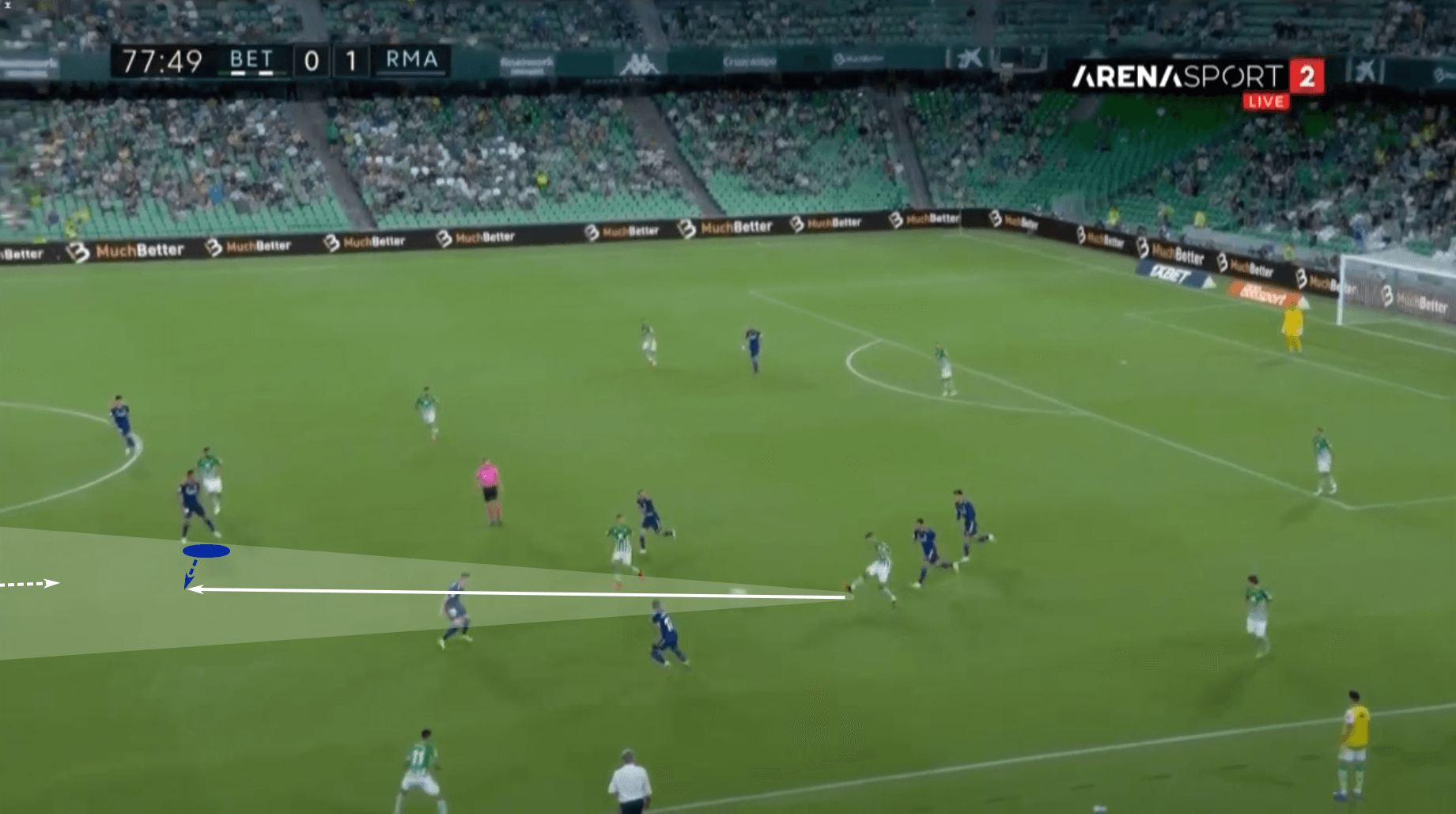

Take the recent match against Real Betis. In the 78th minute, the hosts were engaged in the build-out and thought they had found their opportunity to play through Real Madrid’s press. A window of opportunity to play into the top line opened up, so Betis took their chance.

What they didn’t see was the positioning of Casemiro. When you dissect the image, the first notable point is that he is close enough to his mark to deny the entry pass. Second, his analysis of the passing lane is spot on. He sees that it is the most likely pass in this instance and that by cheating a couple of yards away from his mark, he’s well-positioned to move into that passing lane to intercept the pass. And he does so with ease.

The intelligence of Casemiro’s movement is that he quickly assesses his reference points to identify the likeliest action Real Betis will undertake. Tying this into the four reference points, the Brazilian positions himself with respect to the opponent within his zone and calculates the angle of a potential pass based on the position of the ball and locations of nearby teammates and opponents. Further, he sees the space they are targeting. Understanding those reference points helps him coordinate his starting position, which then allows him to cheat closer to the passing lane and respond to the threat with early movement into that lane.

This is certainly easier said than done, as the dynamic nature of the game is constantly changing the reference points. However, Casemiro’s presence of mind, scanning and threat analysis allow him to assess the likelihood of a given action better than most, if not all, defensive midfielders in the game. In the end, it’s a simple action that produces the desired result, but there is beauty in the simplicity of the act.

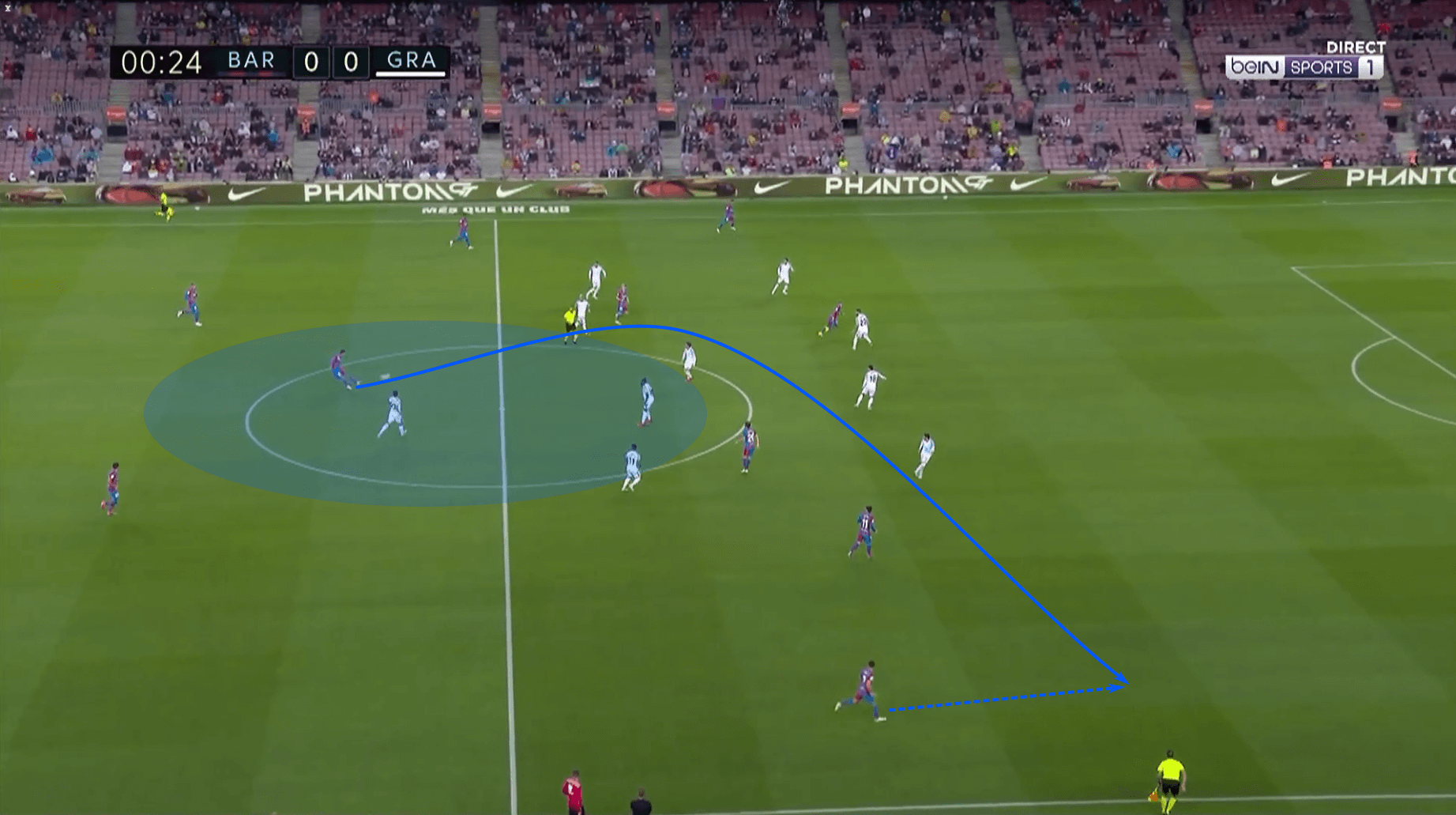

Speaking of beauty in simplicity, we’ll stay in La Liga but move to Real Madrid’s eternal nemesis, Barcelona. Sergio Busquets has run the show from deep in the Barcelona midfield for nearly 15 years. By no means is he a flashy player, but his effectiveness is a result of his intelligence, both on and off the ball. One key concept underlying his performances is the use of central positions to impact play. From a defensive standpoint, his central starting points are intended to keep him in connection with the centrebacks. In attack, he is a deep, central outlet who is easy to find by design.

From that deep central position, Sergio Busquets can operate both as a deep pressure relief option, as well as a facilitator when switching the point of attack or playing over an unbalanced defence, as we see here against Granada. With the opponent in a compact 4-5-1 middle block, Sergio Busquets takes up a position outside of the press in the centre of the park. From there, he offers security of possession, as well as the possibility of switching the point of attack.

Deep starting positions are frequently taken up by defensive midfielders, allowing them to step outside of pressure into a forward-facing position where they can utilise their passing skills to break the opposition’s lines. It’s very common to see a #6 drop between two centrebacks to direct the build-out.

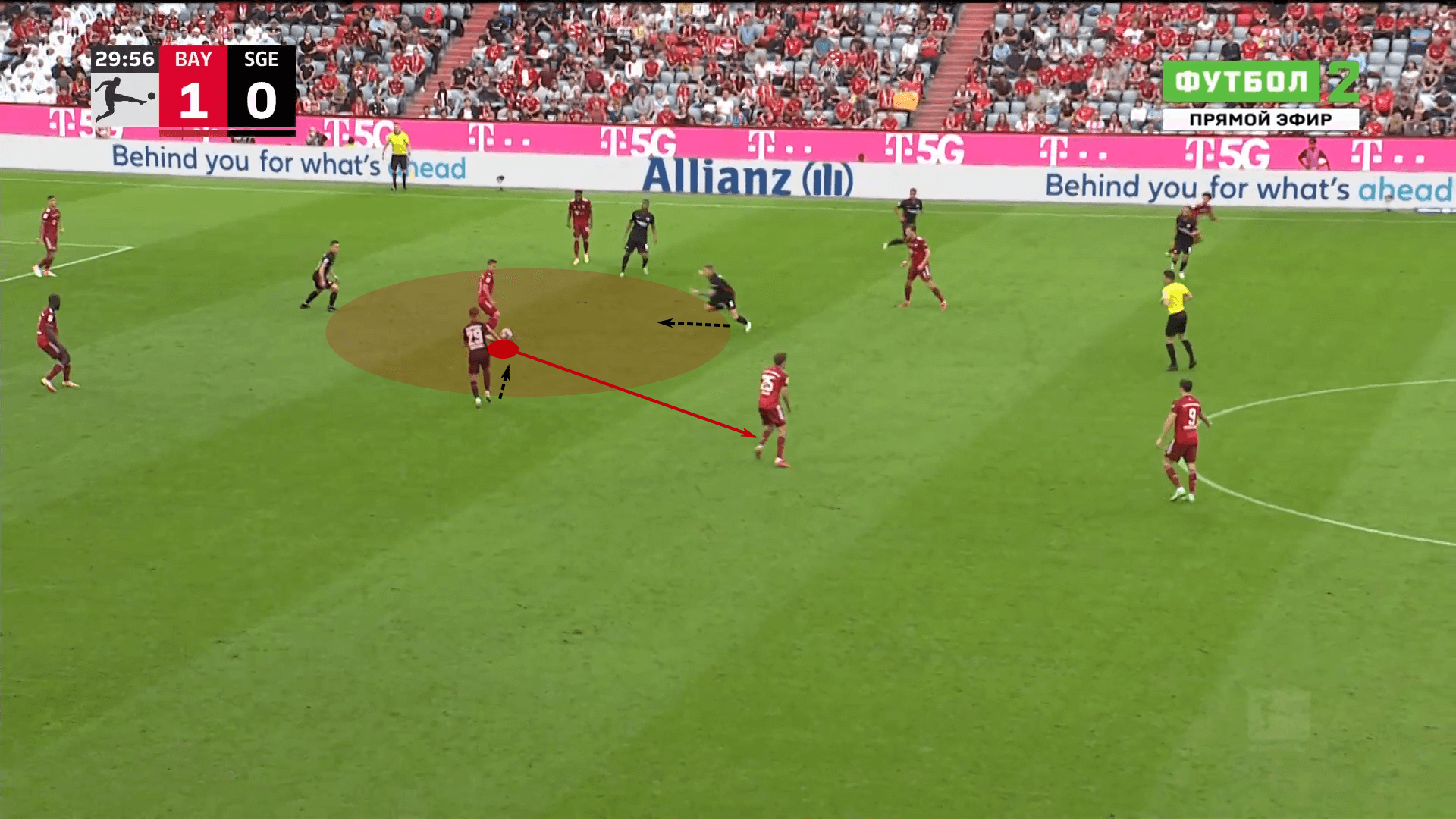

However, not all deep starting points have to originate outside of the opposition’s press. Our next example comes courtesy of Joshua Kimmich of Bayern Munich. The Philipp Lahm tactical doppelganger will often drop outside of the opposition’s press, but he’s also comfortable sitting between the first and second lines of the press. From that position, he bypasses the first line and coaxes the second line forward. As we see in this example, as the second line of the press steps forward, more space emerges between the second and third lines of the press, allowing Joshua Kimmich to easily split the defence.

Another aspect of this positioning is the importance of getting into a forward-facing body orientation between the lines. One of the more common sayings in football is to “play the way you face.” If a player commonly orients their body in a back to goal position, their attacking contribution is inherently limited. They’re not positioned to play forward as their body orientation limits their field vision and body mechanics.

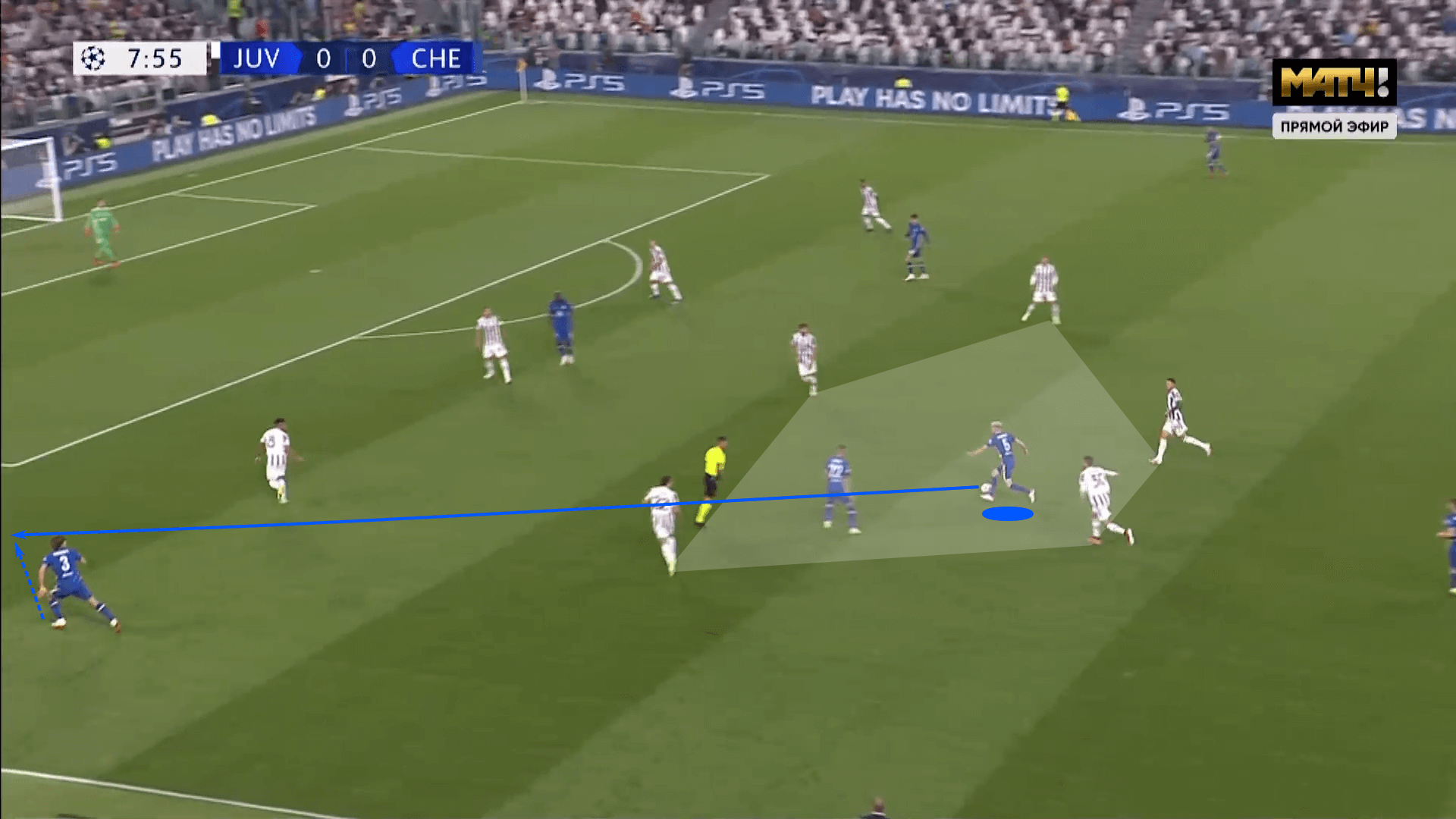

One thing we saw in the Kimmich example, which again is present in Jorginho’s role in Chelsea’s tactics, is that getting into a forward-facing position between the lines allows the deep playmaker #6s to better set the tempo of the attack, determining when there’s the transition from preparing to attack the opponents to attacking the opponents. As Jorginho receives between Juventus’s midfield and forward lines, he is able to play forward, cueing his team to make their move towards goal.

Whether in or out of possession, a common theme among elite defensive midfielders is the understanding of how to quickly analyse the four reference points and determine their response. That response is a product of threat analysis and an understanding of opportunities higher up the pitch. In either situation, top #6’s use their influence from a deeper position to collect a more complete picture of the match dynamics and impose their will on the game.

#8 – Box-to-box bosses

Moving higher up the pitch, we have our box-to-box midfielders, the #8s. Depending on the qualities of the #6, the #8 could be more of a deep-lying playmaker type such as Toni Kroos or more of a true box-to-box presence like Leon Goretzka. A possession dominant side will require an #8 who is comfortable on the ball, whereas a team that struggles in possession, or even prefers to concede it, may opt for an #8 with more defensive qualities.

Since this tactical theory focuses on elite midfielders, the player pool is naturally skewed towards possession dominant teams. That said, there is significant variability in their styles of play and how they fit into their clubs’ tactics.

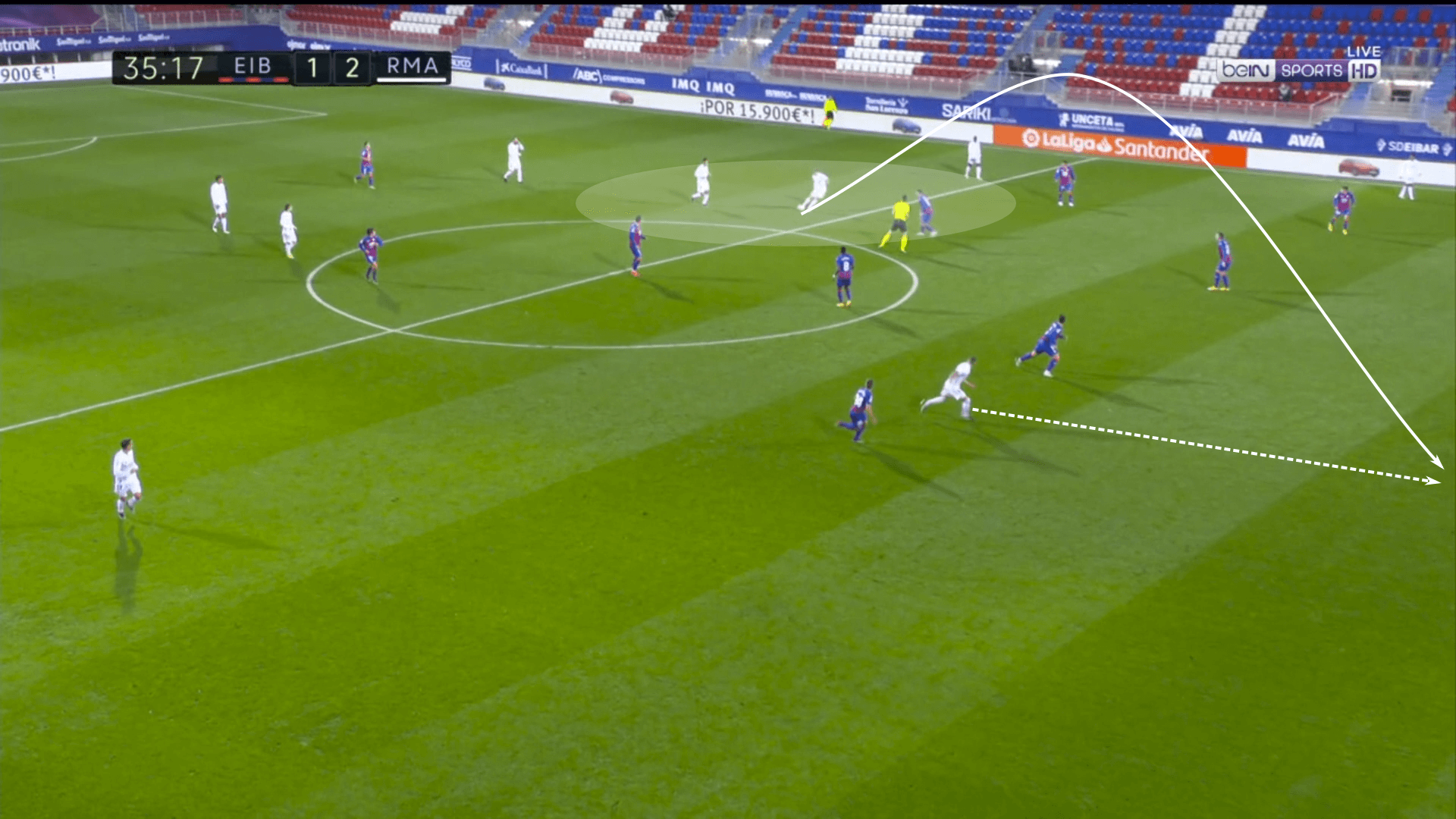

Let’s have a look at our first #8, Kroos. The German’s role is best described as a regista, a deep-lying playmaker whose attacking starting position is often in line with Casemiro, Real Madrid’s #6.

Much like a basketball player who has “his spot” on the floor, Kroos prefers to take up a starting position in the left half space. It’s his hot spot. From the left half space, he can use his incisive passing range to switch the point of attack through long diagonals over a compact defence or he can attack on Real Madrid’s left with split passes.

The benefit of situating himself in the left half space is that it allows him to take up a body orientation that allows him to send accurate passes to any player in front of him. The more difficult cross-body pass to his left is the shortest distance option, whereas the less complicated pass is the 50 to 60-yard diagonal drive to his right. In the first instance, the more difficult technique is aligned with the shorter distance, whereas in the second, the longer pass is met with a more simple technique with a greater margin for error due to the spacing of the opposition.

An added advantage is that aerial passes put into the central channel are also on a diagonal, which are easier for the receivers to control and less likely to run into the path of the goalkeeper.

Kroos, like other registas, typically remains outside of the opposition’s press in order to keep the opponents within his field of vision. With his view of the opponent’s ever-changing defensive shape, Kroos identifies opportunities for attacking actions. His understanding of attacking opportunities allows him to set the team’s tempo. When Real Madrid is well-positioned to transition from preparing to attack the opponent to attacking the opponent, Kroos changes the tempo of the attack and directs his higher positioned teammates to engage the opposition through his passing. Positioning outside of the press leads to greater vision and awareness, which then allows the deep-lying playmaker to signal a change in attacking rhythm.

However, that starting position is not always an option for #8s. At times, they have to create the space they want to attack from.

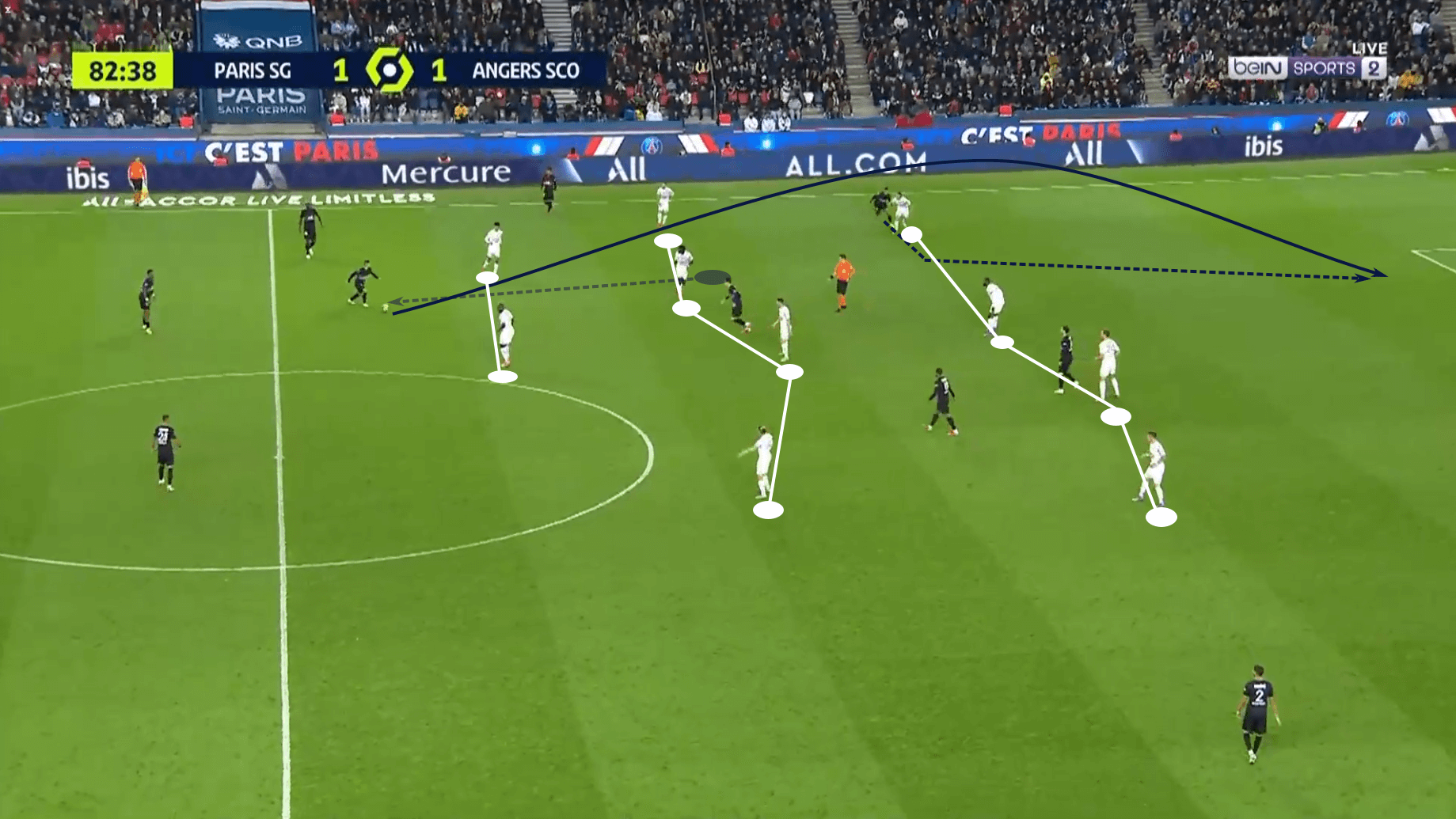

The next image comes from PSG’s match against Angers. Our featured player is none other than Marco Verratti. The diminutive Italian floats between the lines so effectively. This image shows how Marco Verratti initially took up a higher starting position while tightly marked by the midfield line, then checked in front of the line of two forwards. This movement allows him to dismark and get on the ball in a forward-facing orientation. Once he’s in that forward-facing position, that cues the run of Kylian Mbappé to stretch the pitch by attacking the space behind the lines.

Marco Verratti’s check into a deeper position was a simple movement, but it’s the purpose that stands out. Lesser midfielders will often check into too shallow a position. That leads to contested first touches and prevents them from achieving a forward-facing body orientation. Marco Verratti checks well in front of the two forwards and splits the distance between the two, forming an equilateral triangle with them. That equality of distance produces confusion as the two players try to determine who should take on the role of first defender pressure. In the end, neither does, allowing the Italian to play a dangerous ball into a lethal player.

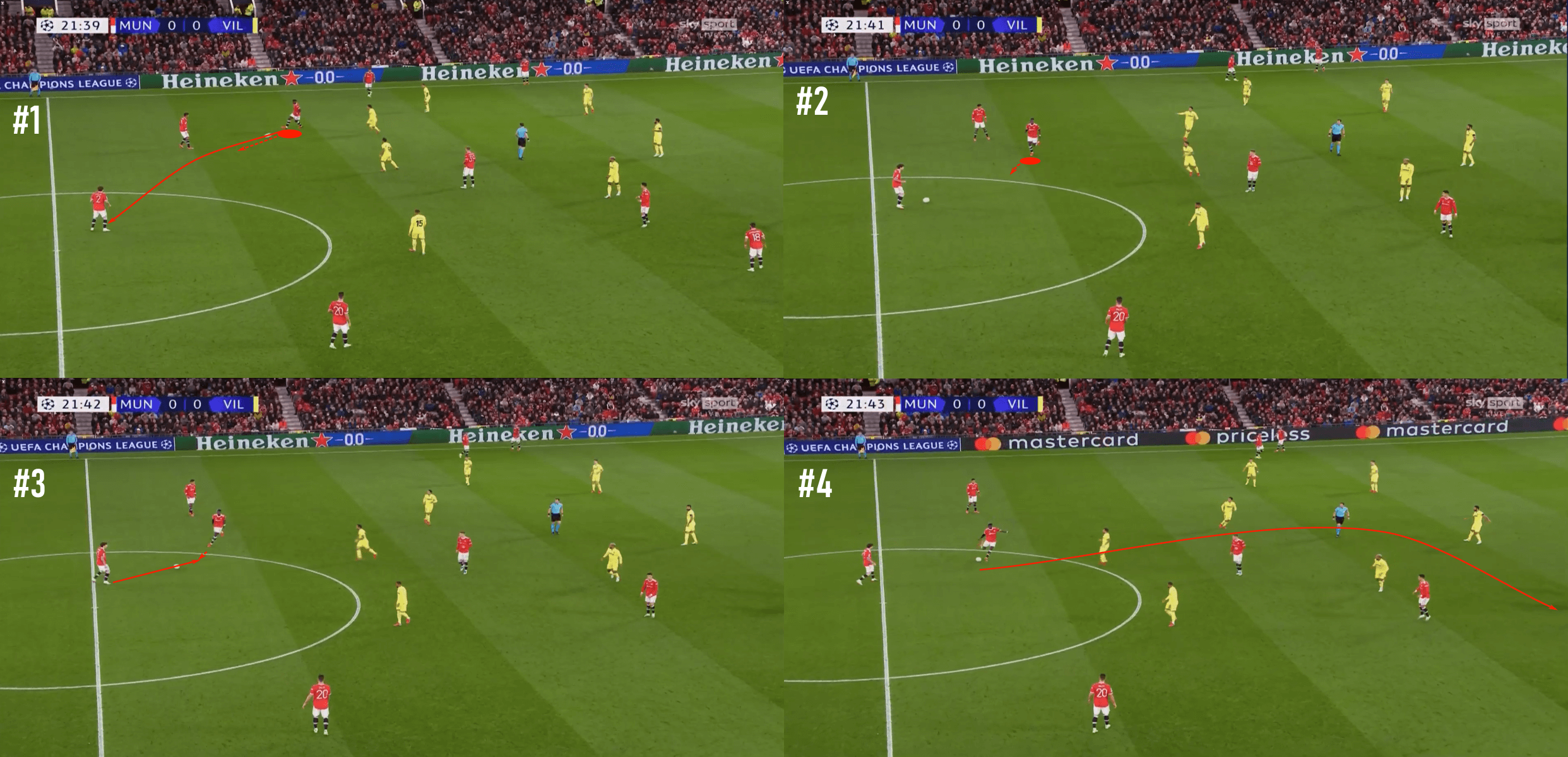

But checking into a deep position isn’t the only point to emphasize. It’s also important to examine how more advanced players, such as #8s, arrive in those deeper locations. Take this four-frame sequence of Paul Pogba as an example.

Pogba is initially engaged in the left half space in an attempt to create a numeric advantage. Villarreal’s press denies that superiority and is well situated centrally as well, holding a positional superiority. Quick ball circulation or a creative pass to break pressure is needed. That’s exactly what Pogba provides.

Not only does he move into the pocket of space in front of the first line, but the angle of his approach is exceptional. Pogba initially runs on a straight diagonal to take the space quickly while it’s still available. In the second frame, he starts to curve his run so that, in the third frame, his hips have already started turning in the direction he wants to play. The fourth frame shows his body orientation as he hits a first-touch pass that breaks the Villarreal press. The bent pass over the press is stunning, but it’s his check into depth and the way he tailors his approach to accommodate the striking technique that allows him to complete the pass.

Thus far, this section on box-to-box midfielders has focused exclusively on creating from deep positions. Whether the #8s are starting outside of the press or checking in front of the first line, this analysis has shown how box-to-box players can use depth in the attacking shape to operate as deep-lying playmakers.

Since these players attack from both depth and height, we will transition into the latter part of our analysis on #8s, identifying how they contribute to the attack from higher up the pitch.

If there’s a better player in the history of the game at striking a balance and attacking from height and depth than Xavi, make your case, but know it will be viewed with the highest degree of scepticism.

Barcelona’s Golden Generation was no stranger to the low block. Since the Catalonians used possession as their stranglehold, opponents learned to drop off, deny space and frustrate Barcelona. With opponents in a low block, the Barcelona midfield was tasked with creating space between the opponent’s lines. Disconnecting the backline from the midfield line was key to their success. In order to do that, Barcelona’s midfielders had to strike a balance between attacking in front of the opposition’s midfield to bring them forward and moving between the back and midfield lines once that space was created.

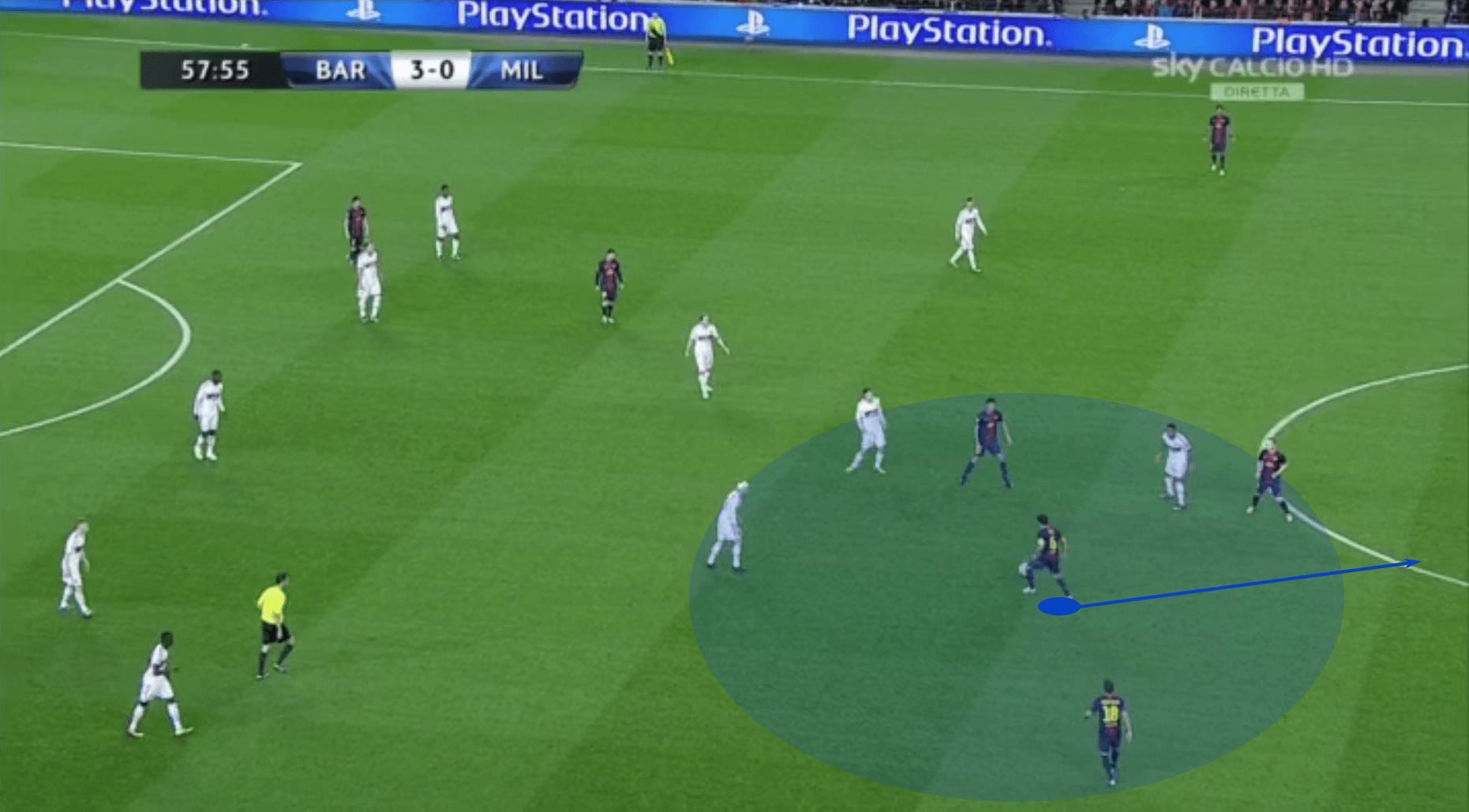

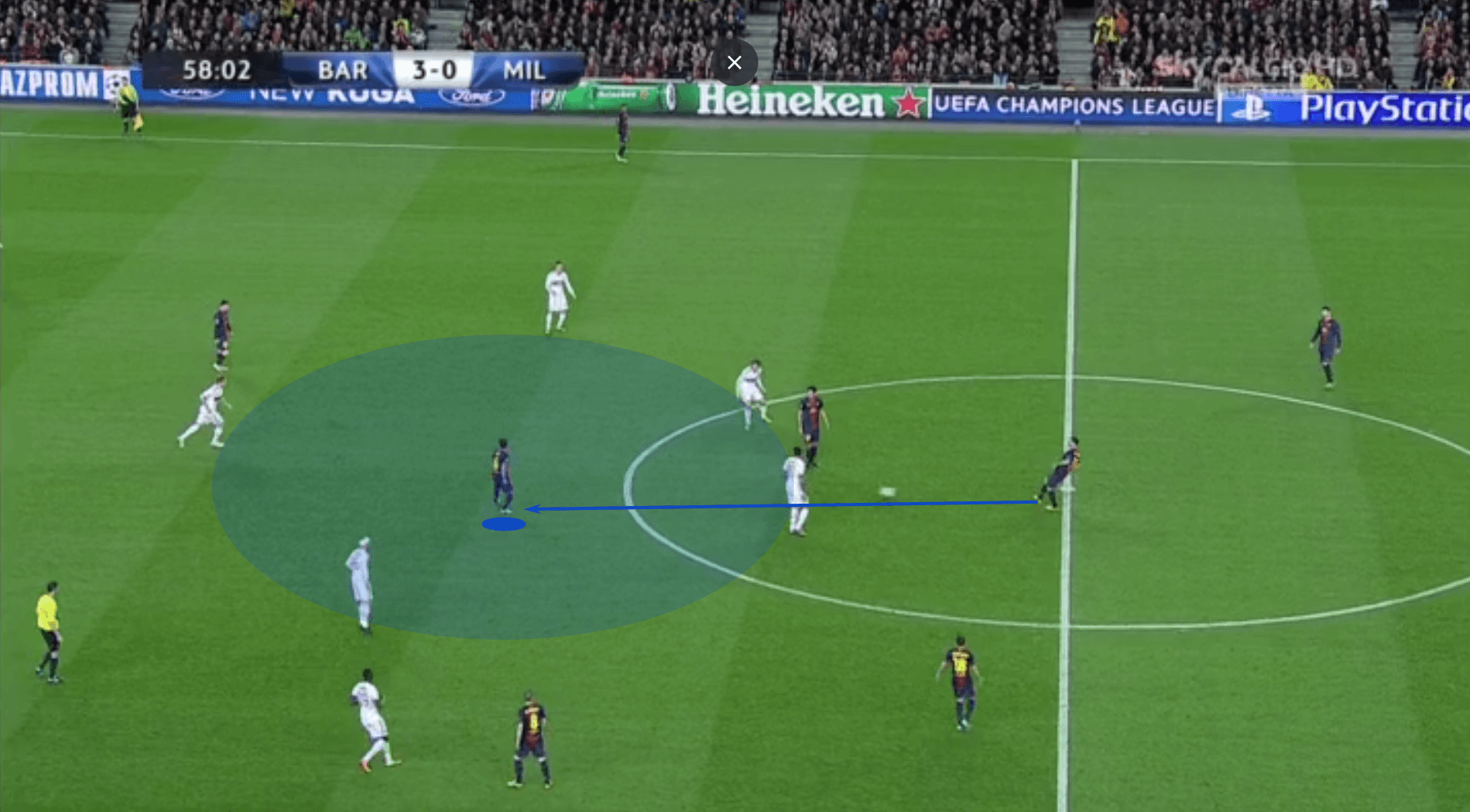

Our Xavi example comes from a Champions League match against AC Milan. The Serie A side’s midfield line is set approximately 36 yards from goal while the defenders have set a line of resistance 24 yards from the end line. Doing the math, that leaves a 12-yard gap between the two lines with two Milan defenders stationed between the lines. That space between the lines is not yet ripe for attacking, so Xavi takes up a position of depth to lure the midfield line forward while Barcelona’s forwards attempt to stretch the height of the attacking space. Xavi received a pass in front of the Milan midfield, then played backwards in an attempt to further lure the opposition higher up the pitch.

As Milan steps forward, Xavi slides centrally to offer a split pass. Even though he doesn’t change his height in an objective sense, he does penetrate the midfield line by coaxing them forward. Relative to the positioning of the ball, space, the opponents and his teammates, Xavi is now attacking from a position of height. He has engaged the midfield line of the press, most especially the midfielder who is lingering in a deeper starting point. The defensive midfielder is now forced to step higher up the pitch, widening the gaps between the back and midfield lines. That’s precisely what the Barcelona of old targeted in open play. At this point, Xavi could play into a higher positioned teammate who could then have a run at the backline. By alternating attacking from depth and height, Xavi used numeric and positional superiorities to unbalance AC Milan’s press and trigger the next phase of Barcelona’s attack.

Operating from numeric and positional superiorities is a powerful tool of elite #8s. This is especially important higher up the pitch as the team looks to progress from preparing to attack the opponents to attacking the opponents. The combination of numeric and positional superiorities creates conditions for proactive attacking patterns. Players coordinate their movement so they move the opposition in a way that enables a progressive action, be it passing or dribbling. Even in cases of numerical quality, where the two teams are locked in a man-to-man duel, a positional superiority for the in possession team allows for dynamic positional rotations.

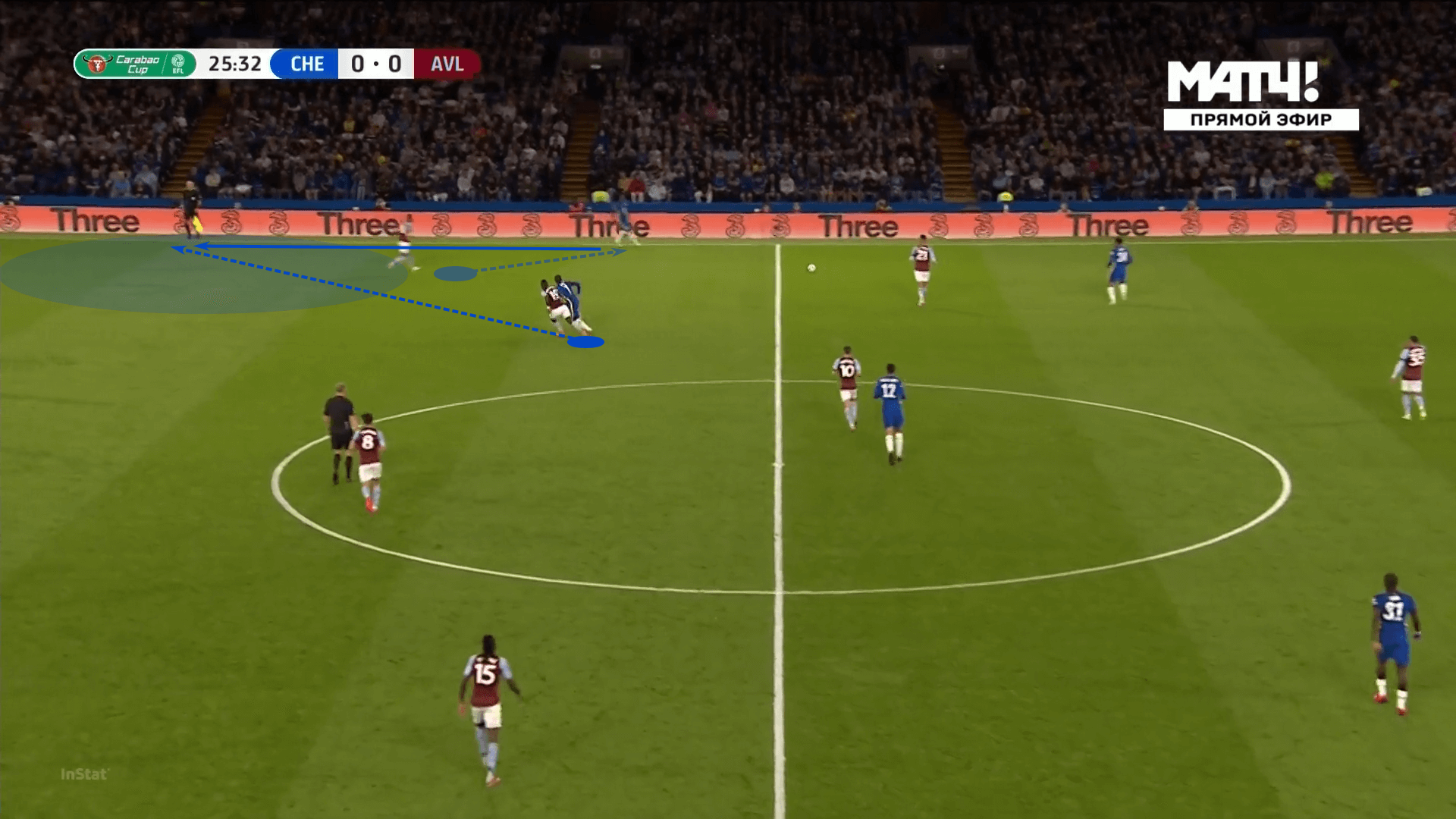

Kante and his Chelsea teammates offer a nice example. As Callum Hudson-Odoi moves centrally from the wing into the half space, Hakim Ziyech becomes the width provider, which frees up space for Kante to attack higher up the pitch.

The rotation is a simple one, but it’s extremely effective. There’s the aspect of ball progression, but this move also places the midfielder, who may or may not be untracked, in a forward-facing body orientation. If he’s untracked or clear of the trailing midfielder, he forces a response from the backline. If the ball near centreback is drawn into the wings to defend against the #8, he’s likely leaving the remaining members of the backline 2v2 centrally. The stakes rise considerably if he’s drawn out.

Dynamic positional rotations are highly effective means of entering the final third and putting the midfielder in a position to send the final ball.

But what about box entries to create and take advantage of scoring opportunities? How can #8s tailor their positioning and runs to offer a threat in the box?

Let’s head over to Germany and study the intelligent movements of Leon Goretzka. The Bayern Munich box-to-box midfielder has evolved into a reliable goal-scoring threat with his late movements into the box. Though his uncommonly large physique for a box-to-box midfielder helps him in contested situations, it’s uncanny how often he arrives at the last possible moment in the box while totally unmarked.

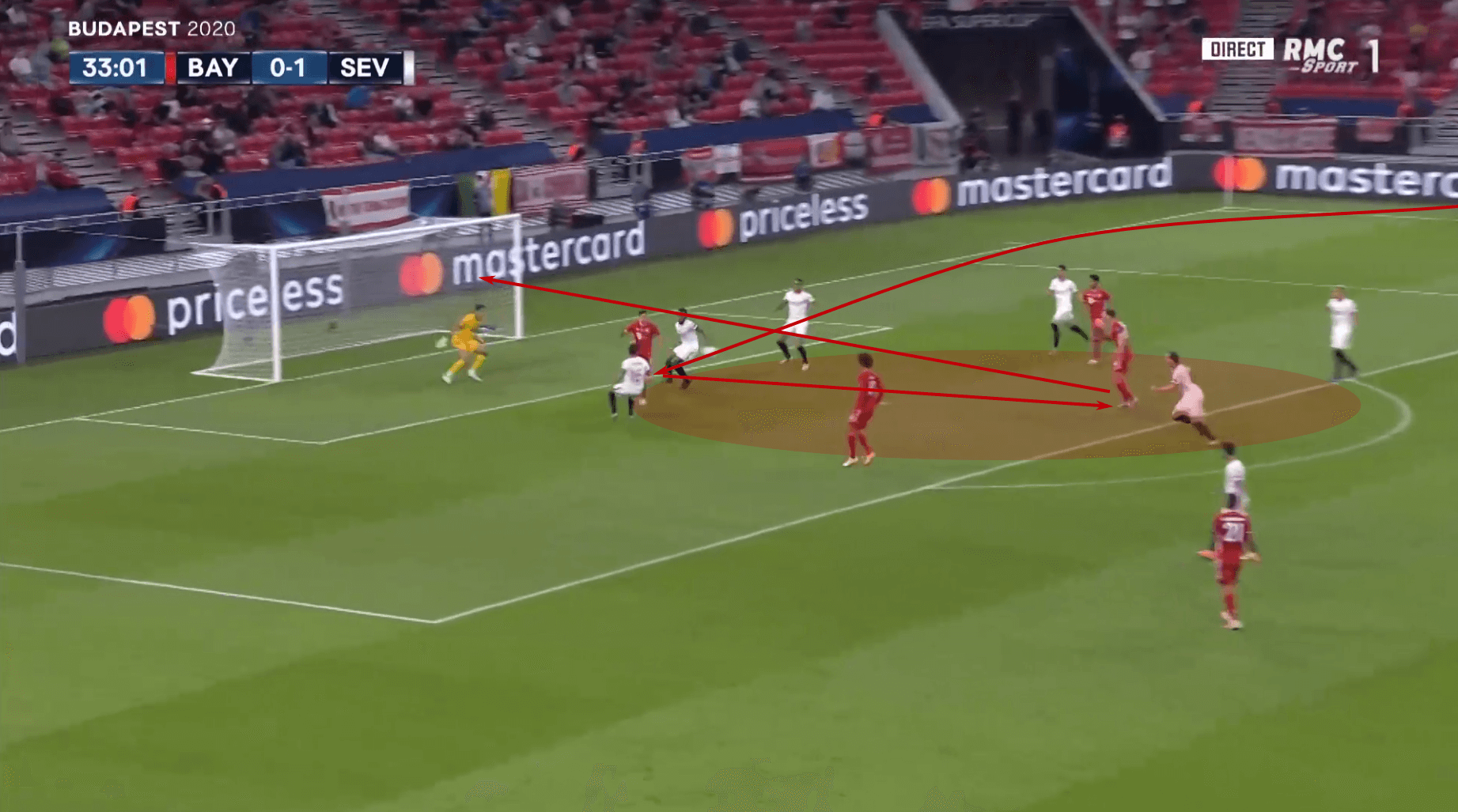

When facing Sevilla, the Bavarians sent a sumptuous cross into the middle of the box. Robert Lewandowski won the first ball, setting it into the path of Goretzka, who provided the finish. Running underneath the forwards is a simple concept used by many, but the effectiveness of this tactic is largely determined by the ability of the forwards to win the first ball and set it into the path of the trailing runners. If the forwards have this talent in their toolbox, the next step is training players to run underneath the forwards.

As you look at the image, Goretzka has found acres of space in the box. Watching this sequence evolve, one of the key points is that, as play was developing, Goretzka was nowhere near Lewandowski. The benefit is that, in starting from a deeper position, he was forcing the Sevilla midfield to account for him in a deeper position, impacting the La Liga side’s positioning. As Bayern Munich move the ball into the wings, Goretzka made his move underneath Lewandowski. As you can see in that image, his late arrival into the box was untracked, meaning he took advantage of a momentary lapse in concentration from the Sevilla midfield to gain his positional superiority. He still had to finish, but the work he did off the ball provided optimal attacking conditions.

We’ve seen how the #8s use their intelligence to attack from both depth and height, creating conditions of attacking superiority with their movement off the ball. In many instances, we’ve seen them create the space they want to attack. That very intentional and intelligent approach to the game looks to disorganized the opposition’s press. The timing of the arrival, as well as the movement mechanics in those final steps, play a huge role in a box-to-box midfielder’s success. If they can arrive in that space while placing themselves in a forward-facing position, they then force an immediate response from the defence, which carries additional attacking opportunities as the lines become disjointed.

Box-to-box midfielders are typically very clever players, but now we move on to the most clever of them all, the revered #10s.

The #10 – Midfield magicians

Though the classic role of the #10 is an endangered species in the modern game, between true #10s and the more common 8/10 hybrid, we’re still blessed with midfield magicians. In fact, even with the decline of the pure #10, we’ve still seen Bruno Fernandes set the season goal-scoring record for midfielders. Not bad for a role that’s in decline.

When you look back to many of the true #10s in the history of the game, their role was strictly an attacking one. With the contemporary game heavily emphasising the high press, few teams can afford to field a player who offers little to no defensive output, regardless of how great a contribution that player makes to the attack. The role of the classic #10 has morphed into more of an 8/10 role as players are called upon to contribute to the defensive press and track back as help is needed in the defensive third.

This change has produced some exceptional, complete players. Over the past couple of decades, the standard-bearer for the position has been Andrés Iniesta. Currently in the J League with Vissel Kobe, the Barcelona legend exemplified the artistry, cunning and defensive commitment that is now standard in the role.

As mentioned earlier in the analysis while studying Xavi’s movements, we noted that Barcelona’s Golden Generation frequently encountered low blocks, requiring the midfielders to work in tight spaces and design their movements to create the space they wanted to attack.

Iniesta was a master at drifting to either side of the opponent’s midfield line. Though it was common for him to check deep to offer a numeric superiority near the ball, it was equally common for him to initially start higher up the pitch, pinning the opponent’s midfield, then dropping deep into the space he had created. As the opponent stepped forward, leaving gaps between their lines, Iniesta looked to break their lines with runs, dribbles or passes.

That’s precisely what happened in this match against Sevilla. Iniesta took a high starting position, checked in front of the midfield line to receive and then split the defenders on the dribble. With each defender trying to deny a passing lane, Iniesta took the space they were giving him via the dribble.

The keys here are pinning the opposition high up the pitch, checking into a deeper space to receive and then taking the space given.

The mobility and quickness of the #10 plays a significant role in their success. Acceleration and deceleration are key attributes as these midfield magicians use deception to make new spaces appear out of thin air.

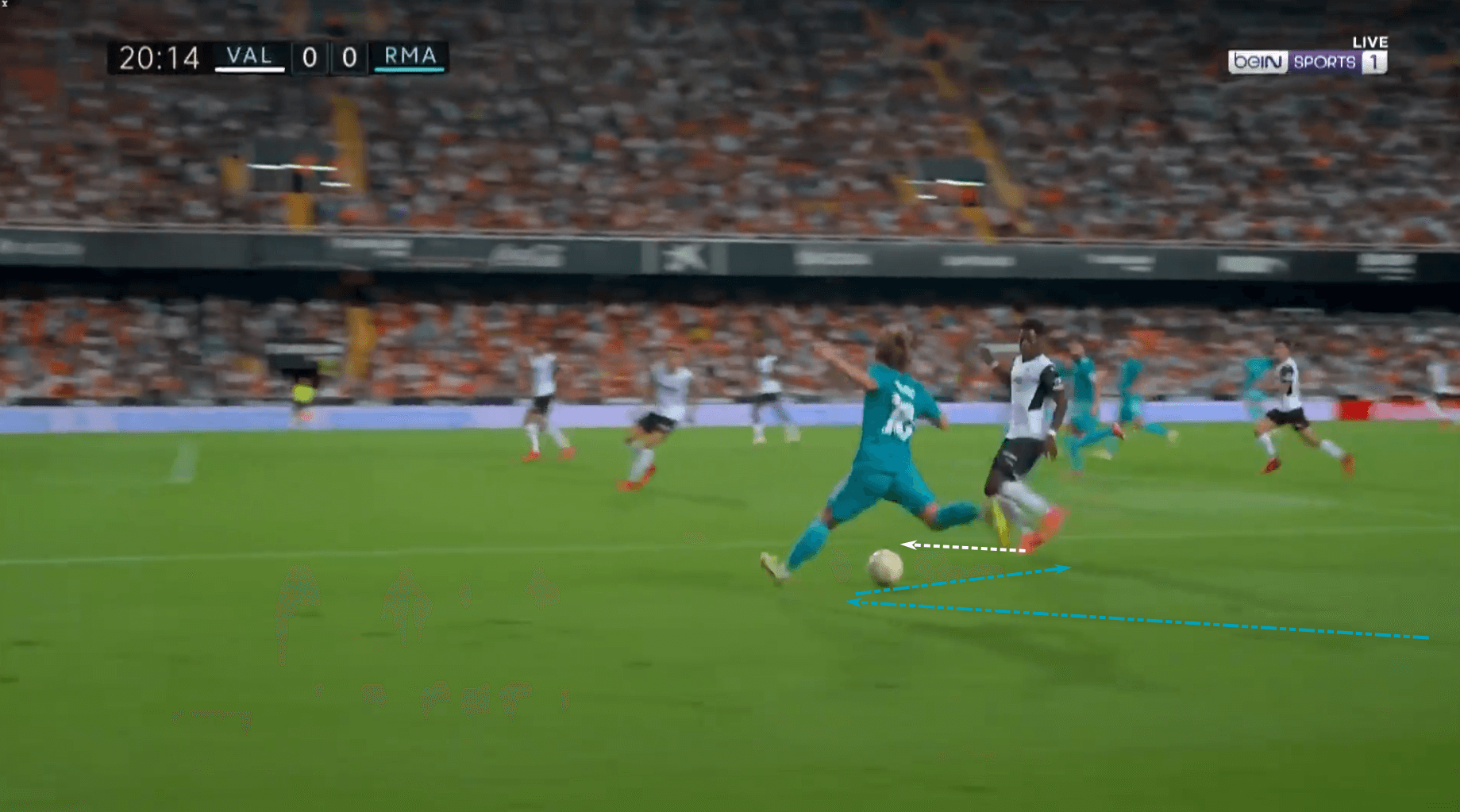

Among active players, it’s difficult to look beyond Luka Modrić in the movement mechanics department. Though he’s 36 years old, his acceleration and deceleration are incredible to watch. The total body control and use of deception in his movements, all while maintaining close control of the ball, leave his defenders in uncomfortable predicaments.

To give an example of a Luka Modrić deceleration with a technical action feint, the cameras caught a great view during a recent match against Valencia. Modrić, who can hit a deadly trivela, gives the impression that he’s sending a cross into the Valencia box with the outside of his right foot. The defender bites on the play and, in a flash, Modrić cuts around him to his right.

As teams enter the final third, individuals are often looking for just a yard or less to complete a shot, cross or pass. There’s so little room to operate that movement mastery from the most advanced players is pivotal to their success.

As we see in Modrić’s movement, baiting the defender to overpursue, selling a deceptive action and the body mechanics to quickly decelerate then accelerate make the elite #10s stand out from the crowd.

Now, that’s an example while under pressure from a defender. Watching the top #10s play, you’ll find that they are also masters of dismarking. Somehow, they will push high into the final third without commanding the attention of either the backline or opposing midfielders. There’s a stealth quality to them even though they’re one of the players on the pitch that receives the most attention from the opposition.

Manchester City’s Kevin De Bruyne is a fantastic example of this. The way he drifts into support positions underneath his front three or darts high into the half spaces to receive the ball in the box and provide a negative cross is a masterclass in midfield movement.

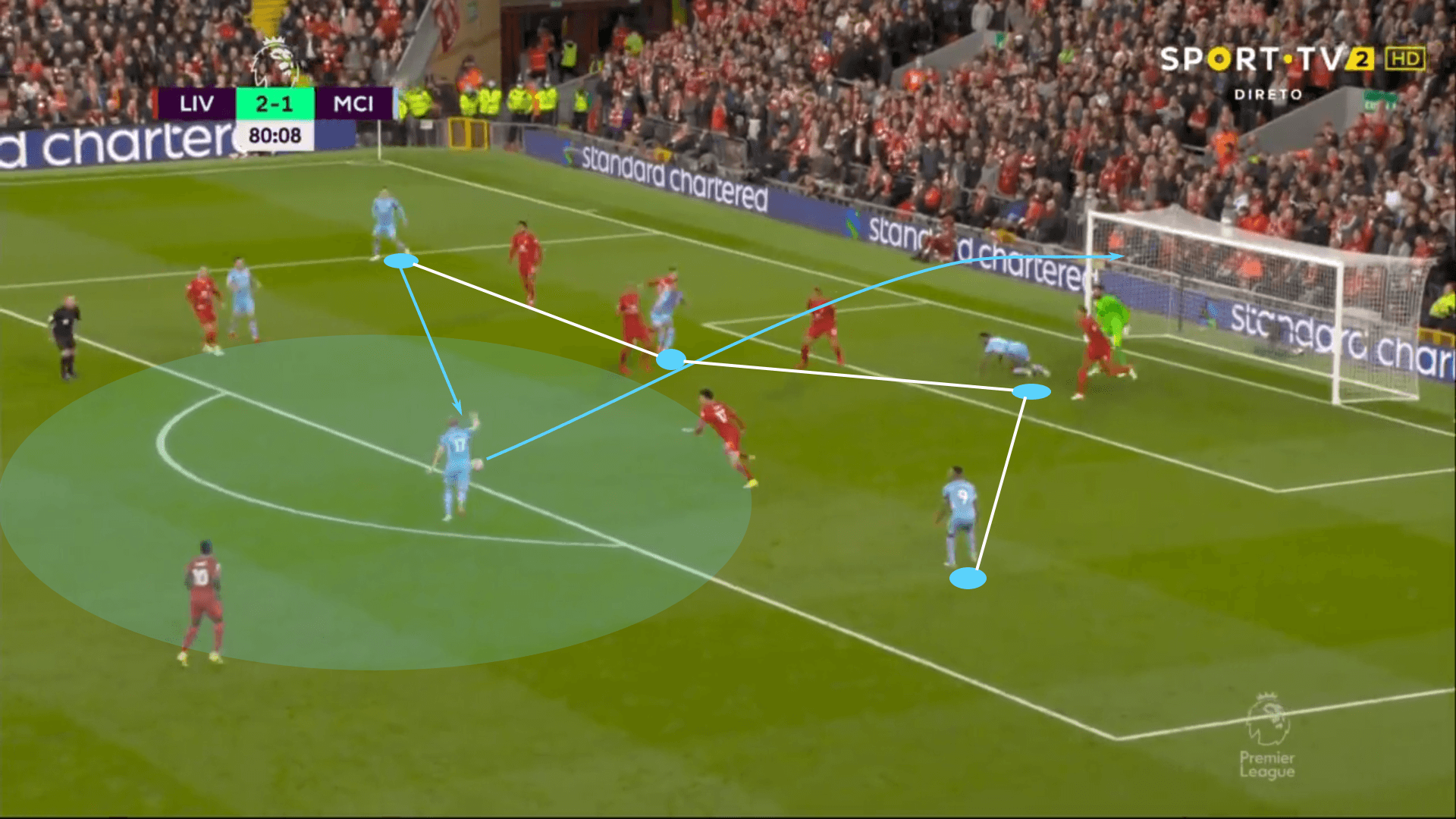

Though he’s better known for assisting goals rather than scoring them, he’s still one of the top goal-scoring #10s in the game, which really lends credit to how exceptional a playmaker he is. In Manchester City’s 2-2 draw against Liverpool, it was De Bruyne who levelled the scoreline late in the match. The key to the goal…allowing play to develop ahead of him.

As Phil Foden entered the box from the left-wing, he hit a low-driven cross into the box which deflected into the path of De Bruyne. The Belgian was unmarked at the top of the box and his shot secured a point. Sounds simple, right?

There are a few keys to this goal. First, City had two players running deep into the box to offer Foden a target. As they pushed forward, they commanded the attention of Liverpool’s backline.

Second, notice the space De Bruyne has. Initially, Curtis Jones was running with him step for step. However, as Foden prepared to send the cross, Jones continued running into the box at the same pace whereas De Bruyne, who is just outside of the box at that time, slowed his pace to create separation. There’s certainly some good fortune in the ball deflecting into the path of De Bruyne, but his movement to dismark from Jones and find space at the top of the box showcased his football IQ. The ancient Roman philosopher Seneca said that “luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity.” De Bruyne’s preparation in the sequence was spot on.

De Bruyne isn’t the only #10 in Manchester to make the list. His Manchester United foe, Fernandes, is also a master of movement off the ball. His goal totals pay tribute to the quality of his movement.

As you watch the former Sporting Clube midfielder play, you’ll find that he is exceptional at identifying pockets of space in the left and right half spaces, then sending a dangerous ball into the box. Much like Kroos, there’s an element of “finding his spot” on the pitch. Especially from the left half space where he can bend a ball into the path of his runners or crack a shot himself.

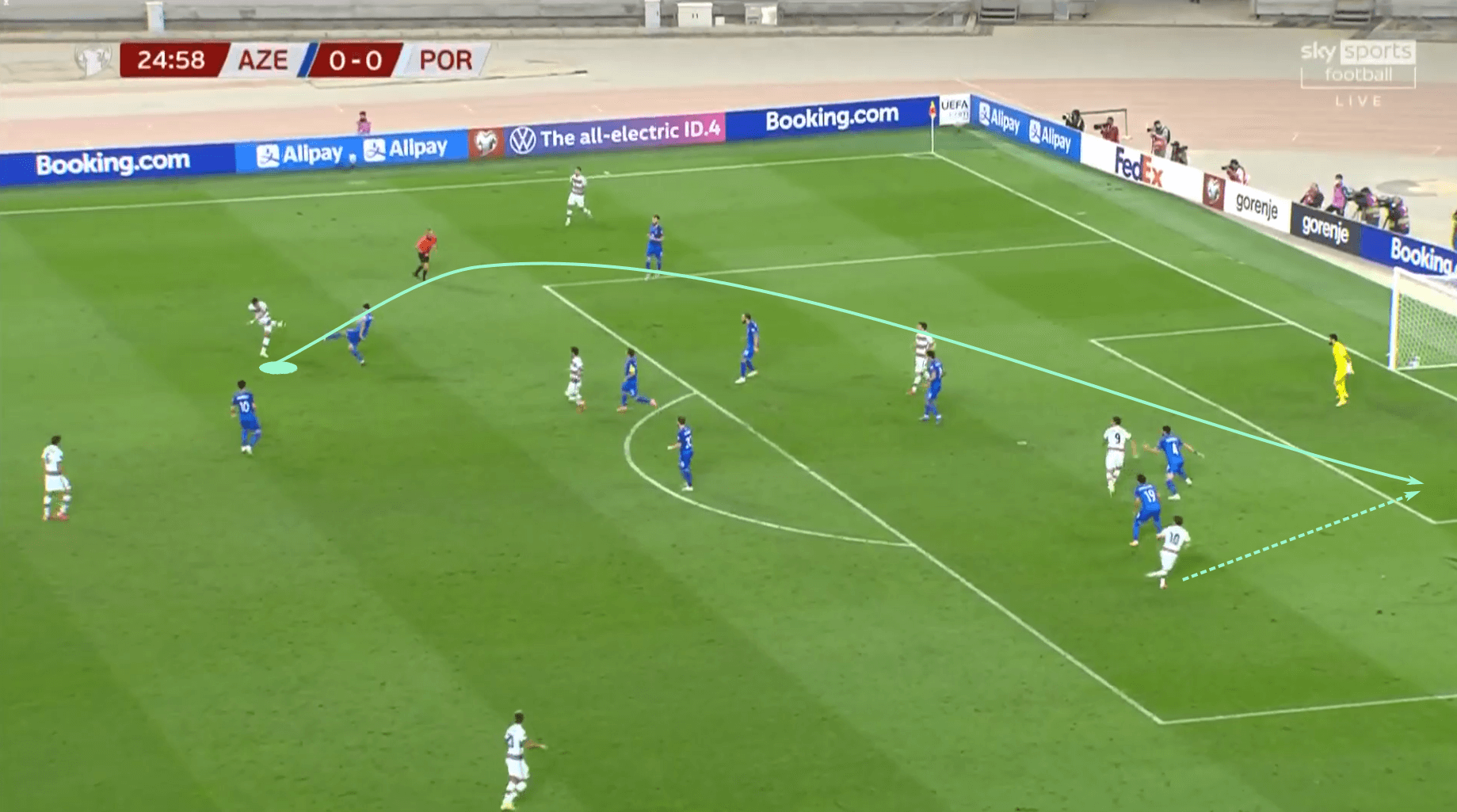

In Portugal’s World Cup qualifier against Azerbaijan, Fernandes played one of his far post crosses into the path of Bernardo Silva. The connection gave Portugal their first goal of the game and paved the way to an important road win.

As you watch the play, there is that element of pulling himself outside of the run of play, targeting his preferred region of the pitch just beyond the opposition’s press. In doing so, he finds himself in a forward-facing position with time and space to play forward into the path of ready runners. At times, the best way to go forward is to start by going backwards. That’s precisely what he does with his positioning before playing a dangerous ball from the half space.

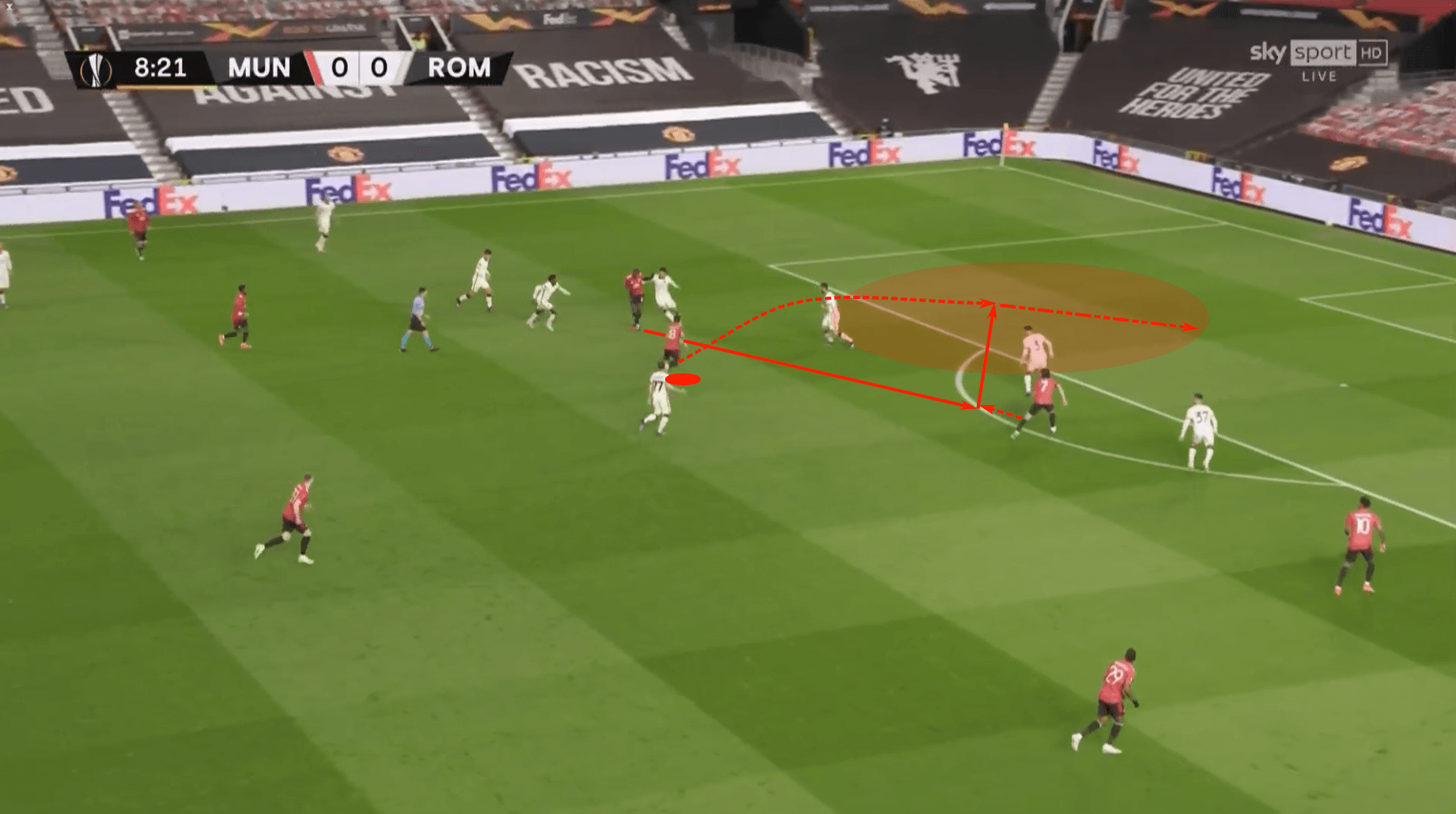

Taking up those positions deeper in the half space pays additional dividends. Circling back to Manchester, United’s Europa League fixture against Roma saw Fernandes set up in the left half space once again. This time, Pogba cut inside on his preferred right foot, drawing Chris Smalling higher up the pitch. As Pogba played a pass into the feet of Edinson Cavani, Fernandes burst into the space behind Smalling, securing the first of six Manchester United goals on the night.

From that position in the half space, Fernandes can either target a dangerous ball into the box or make a run into the 18 himself if he finds a crack in the opposition’s defences. The added advantages of positioning himself between the opposition’s lines are that the midfield will struggle to recover and his line of vision allows him to scan for the opposition’s vulnerabilities as they defend against a threatening attack.

#10s are crafty players, hyper-aware of vulnerabilities in the opposition’s defences. As cracks surface, they’re quick to attack and provide either the final pass or generate their own shooting opportunity. Whether more of a playmaking #10 like Iniesta and Modrić or a goal-scoring threat like De Bruyne and Fernandes, #10s are masters of movement in tight spaces. Where we see bodies, they see opportunities. All they have to do is move the right pieces to create the space they want to attack. Once they’ve done that, it’s game over.

Conclusion

You’ll notice this analysis did not study the movements of wide midfielders. Their movements are often very similar to those of wide forwards so, if you are a wide midfielder or field one in your team, I recommend taking a look at the tactical analysis on the intelligent movements of elite attackers.

This article focused primarily on a midfield three, though, when you look at some of the player examples, there are instances of midfielders playing within a flat-four. Kante and Jorginho, Chelsea’s two central midfielders, play in a line of four. Some of the movements are more specific to a role within a midfield three, but many of the other movements in this analysis are more general approaches to moving in and out of the opposition’s press.

In the end, it should be a sense that within each match there’s a game within the game. Midfielders are not only trying to position themselves with respect to their teammates or the position of the ball, but they’re also analysing their other two reference points, the opposition and space, to identify how they can make a positive contribution to their team’s attack. At times, that means checking towards the ball to get it on their feet. At other times, it’s pulling themselves away from play, setting themselves to play off of the second or third attacker.

As you look at the images again, you’ll find that a common theme is that these midfielders were consistently putting themselves in forward-facing positions. If we are to play the way we face, we want to orient our bodies to maximize our attacking threat any chance we can. There is a time to play with one’s back to goal and simply set the ball back into a teammate, but there are other times when better movement off the ball prepares a player to be more effective when the ball does arrive at his feet. That point stresses the mental side of the game, especially the importance of staying switched on so we can identify the problems posed by the opposition and work towards the solution.

Next month, we’ll continue the trend of intelligent movements, moving deeper once again to examine members of the backline. Until then, if you have found this article helpful, take the ideas to your training sessions and matches.

Comments