If you think about it, registered formations are one of the few aspects of football that hasn’t advanced in recent years. A team can adopt multiple shapes and systems depending on where they are on the pitch, and who has possession of the ball. Stating a team as playing in a set 4-3-3, for example, is actually quite an archaic outlook on the modern game.

Now I’m not saying I have the methodology to rectify this shortcoming in our game, merely highlighting that by assigning one value to a team’s shape we hide the true fluidity and dynamism of that particular system, losing out on the nuances in tactics between each team.

Within this rigid assignment we still crave, despite it not truly reflecting ongoings on the pitch (perhaps at kick-off only), managers have been able to hide their philosophies and winning ways under the guise of these classic formation labels.

In this tactical analysis, we uncover the true identity of winning formations, drawing attention to one system in particular – that I have never seen as a recorded formation – which secretly keeps winning teams the Premier League. That formation is the 3-2-5.

The Foundation

That formation doesn’t look correct, right? How can a team play with just two midfielders and not be overrun? How do you even subtly play five attackers in one team? The practical example reiterates the problem with static formation labelling – it completely removes in-game context.

Depending on your familiarity with tactical analysis, you may be aware that this system can be identified in teams spanning back years, but most memorably – and where I will be focussing on in this article – in Antonio Conte’s Chelsea, Pep Guardiola’s Man City and Jürgen Klopp’s newly crown champions, Liverpool.

Each of these managers all play a notoriously different style of football within differing position parameters. Chelsea under Conte played in a ‘rigid 3-4-3’, Man City, when they won the title in 2018/19, played an ‘artistic 4-3-3’ and Liverpool’s ‘explosive 4-3-3’ is world-renowned.

Despite the overt differences, there’s one particular area within certain contexts of the game where each team had very similar approaches, and that was the 3-2-5. There were slight variations within each system – which we will look at – but the fundamental principles were identical.

Chelsea 2016/17

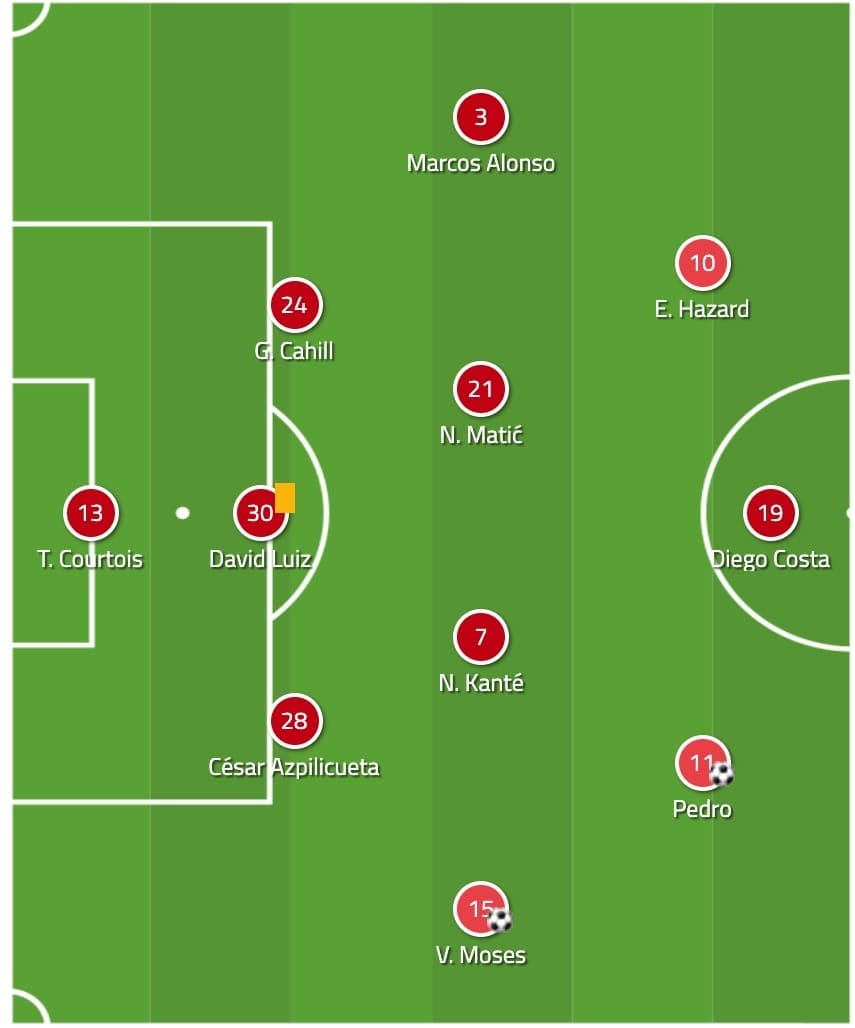

Starting in chronological order we look at Chelsea’s title-winning team in 2016/17. Conte’s men finished the season on 93 points, seven ahead of rivals Tottenham, scoring 85 goals. Below is a typical line-up fielded by the Blues.

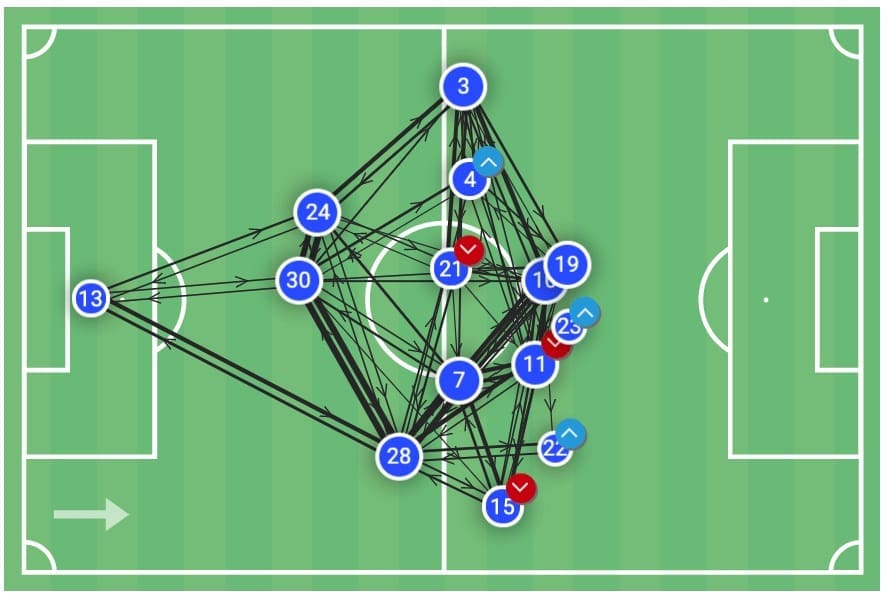

From a static overview, it can be called a 3-4-3, which they used 48% of the time, racking up over 1,919 minutes in the system. This tells us the philosophy and instruction of Conte was imposed from the outset and continued (obviously) as a result of the success it yielded.

Where it deviated from its label, getting into the crux of the article, is when the shape shifted into a 3-2-5 system in the second phase.

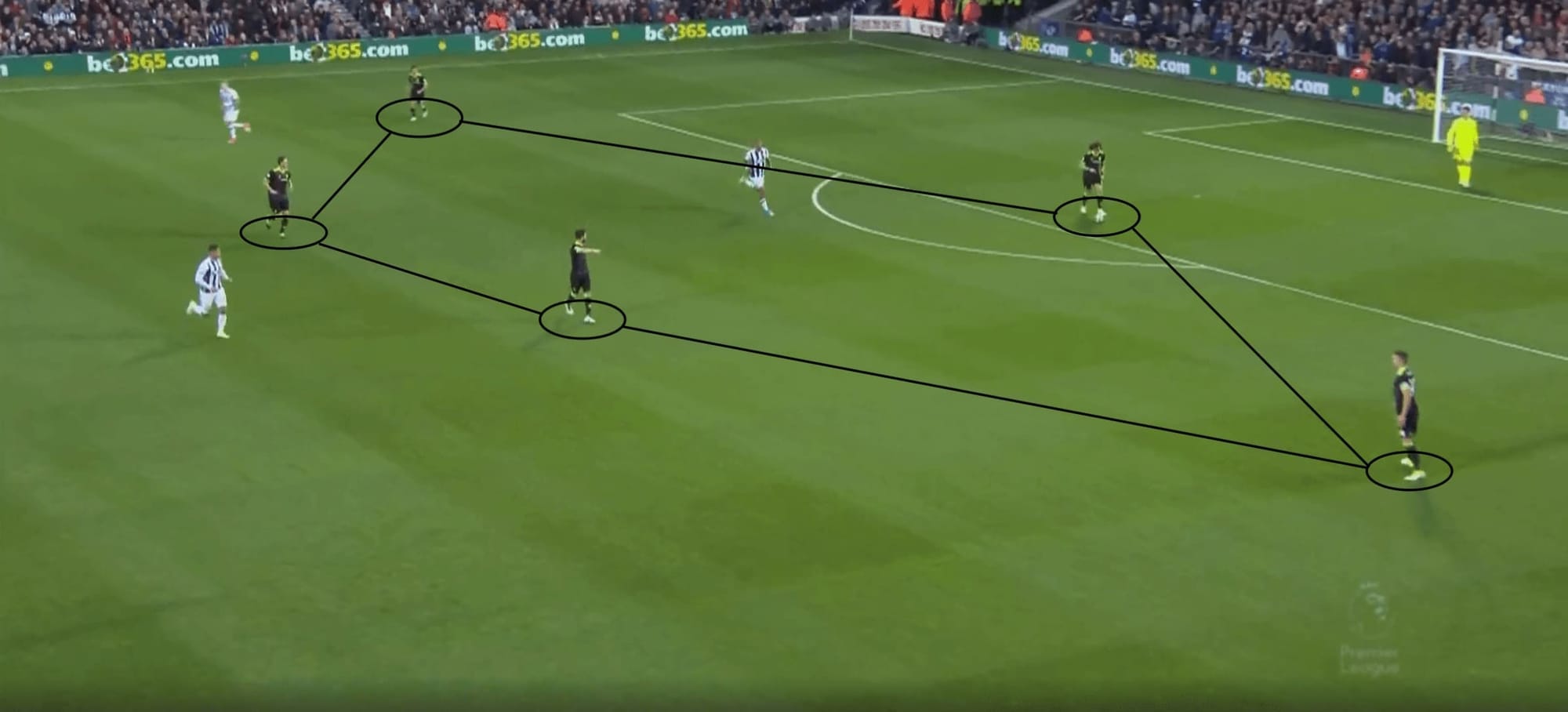

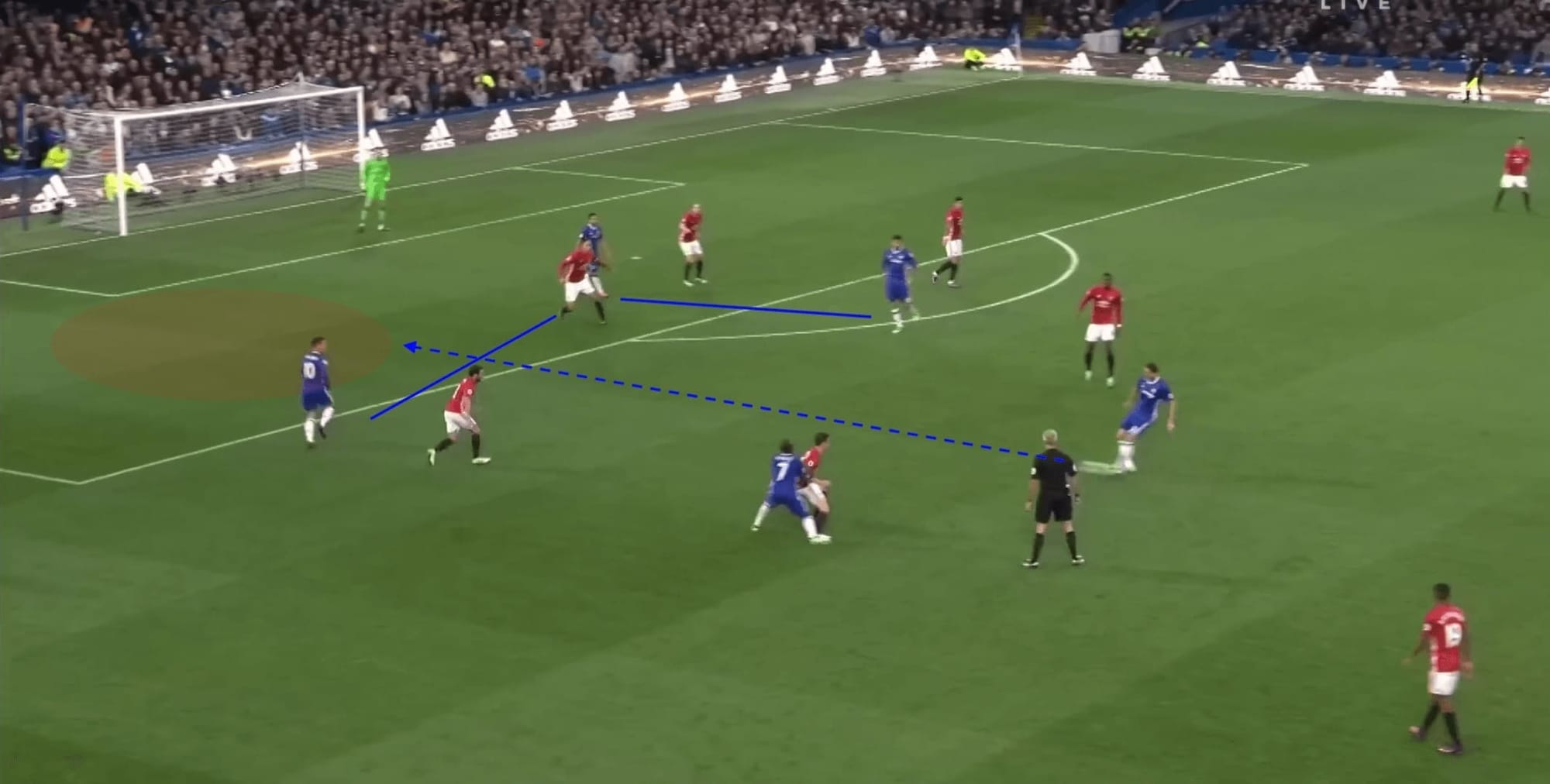

Once Chelsea had recovered possession and established control of the ball, they immediately put their tactics into play. The first part of the system involved splitting the pitch into two ‘mini-games’ as we can see above.

As seen from the images, Chelsea split their centre-backs, who were usually Gary Cahill and César Azpilicueta, allowing David Luiz in the middle to retrieve the ball from his goalkeeper. The centre-backs movement worked in conjunction with the wing-backs, Marcos Alonso and Victor Moses, who already at this stage in possession had moved forward to join the second ‘mini-game’ in the opponents half. The central midfielders, in this instance Nemanja Matić and Cesc Fàbregas, acted as a double pivot and dropped deeper on the same line to create the first half of the 3-2-5.

By splitting the pitch in this way allowed Chelsea to overload against a high pressing team. Often when teams looked to regain possession in high positions against this Chelsea side, they faced a 4vs5 or 4vs6, including the goalkeeper, making it extremely difficult to press effectively. As a result, Chelsea were continually able to progress the ball into opponent territory with little risk of possession loss.

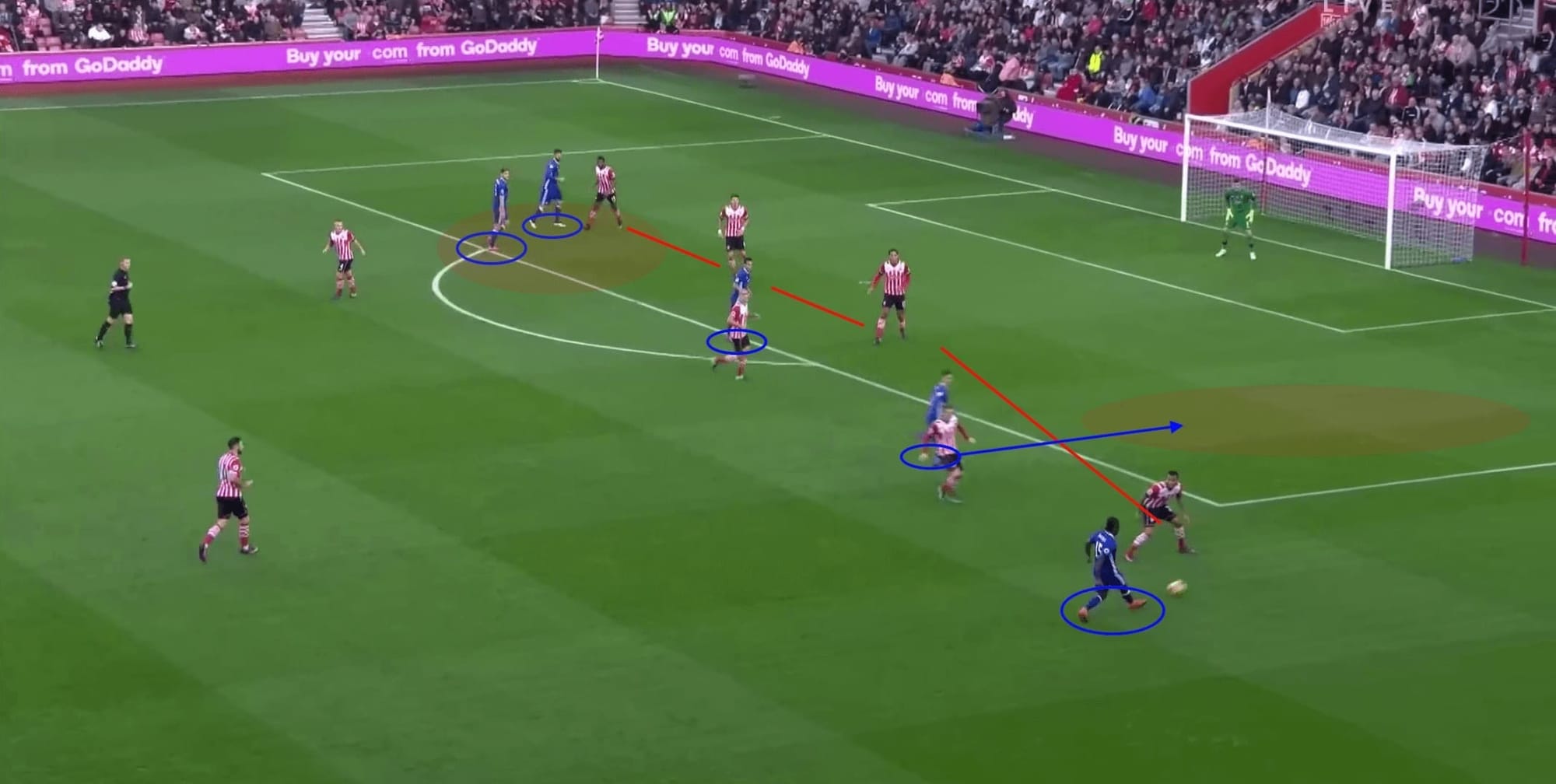

Once out of their own half, the game entered into the second ‘mini-game’, which this time featured the attacking unit of Chelsea. There’s a lot going on in the image above but by breaking it down we can reveal the beauty in its simplicity.

As previously mentioned, Chelsea’s wing-backs pushed high and wide, protected by the five-man unit left in the other ‘mini-game’. The inside forwards, usually Eden Hazard and Pedro/Willian, moved inside into the half-spaces. The presence and width of the wing-backs is imperative to the whole tactic as it forces the opposition wing-backs into a difficult decision-making scenario.

As we can see above, Chelsea often faced up against 4-man defences, meaning their high-5 attacking players could create 5vs4 overloads in this area of the pitch. We can see that the opposition wing-back has moved out away from his centre-back, opening large gaps in the half-spaces. Because of Hazard’s narrow positioning, he is able to penetrate into this space unmarked by running in the blind spot of his marker.

Notice on the other side of the pitch, this full-back also has a problem. He has two players to mark because the four-man backline cannot cope with the five of Chelsea in attack. If Hazard is able to put in a delivery of any quality, which he often was, it resulted in a good opportunity at goal.

The picture above further demonstrates the effect of the narrow front three, which is supported by the high and wide wing-backs. In this instance, Man United fielded a back-four, and Antonio Valencia (out of shot) decided to stay with the advancing wing-back. In doing so he opens the half-space for Chelsea to penetrate.

This simple approach of creating two sections of the field and deploying two units to fulfil their segregated roles, allowed Chelsea to win game after game and take the Premier League title. Their ability to overload in key position constantly asked difficult questions of decent defenders, who eventually became overrun. It will be known as the 3-4-3 that won the league, but to me, this is a great example of using a 3-2-5.

Man City 2018/19

Next up is Manchester City’s title-winning team in the 2018/19 season. Under Pep Guardiola this Man City team wowed the footballing world by playing a brand of football that hadn’t been seen in the Premier League before.

Despite the philosophy being unrecognisable, the underlying principles of the 3-2-5 featured prominently in this City triumph, as we now take a look.

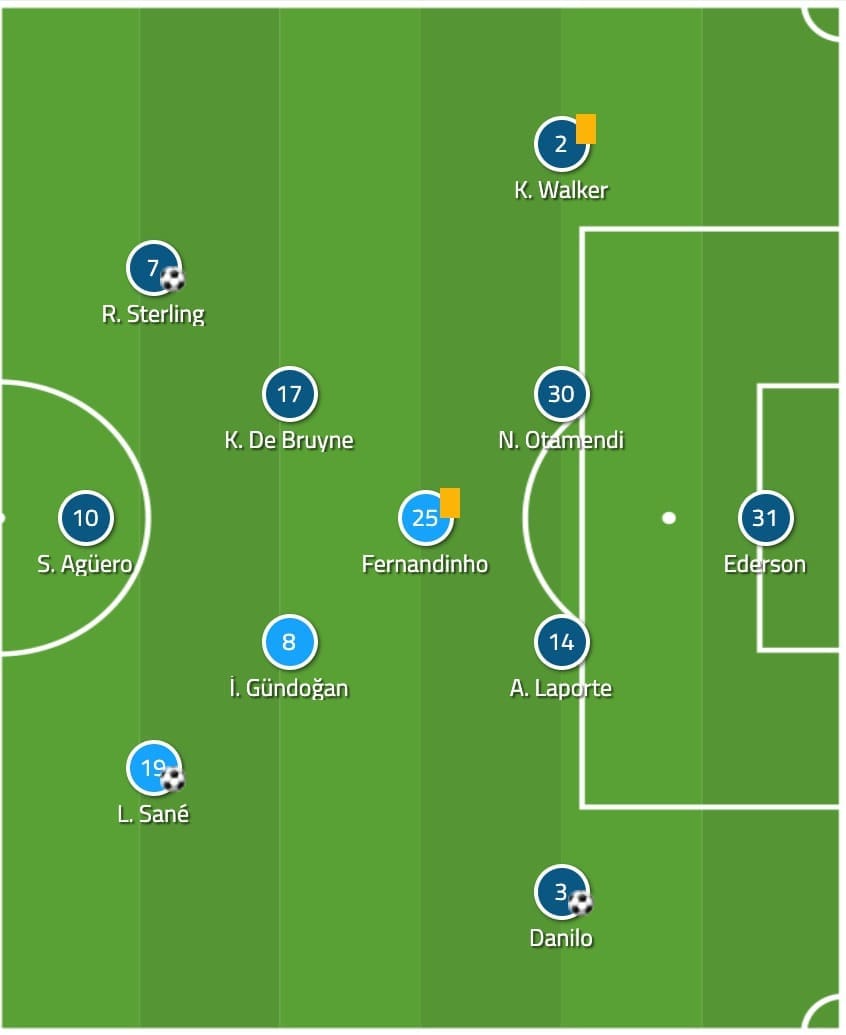

Above was a common line-up from Guardiola, featuring the likes of Fernandinho, Kevin De Bruyne and İlkay Gündoğan/David Silva as part of a midfield trio. Man City lined up in the ‘4-3-3’ system 77% of the time in their title-winning campaign.

Again, what was called a 4-3-3, in certain contexts of the match, was actually a 3-2-5. Much in the same way as Chelsea had done a few seasons ago, Guardiola implemented his own spin on the unorthodox tactic.

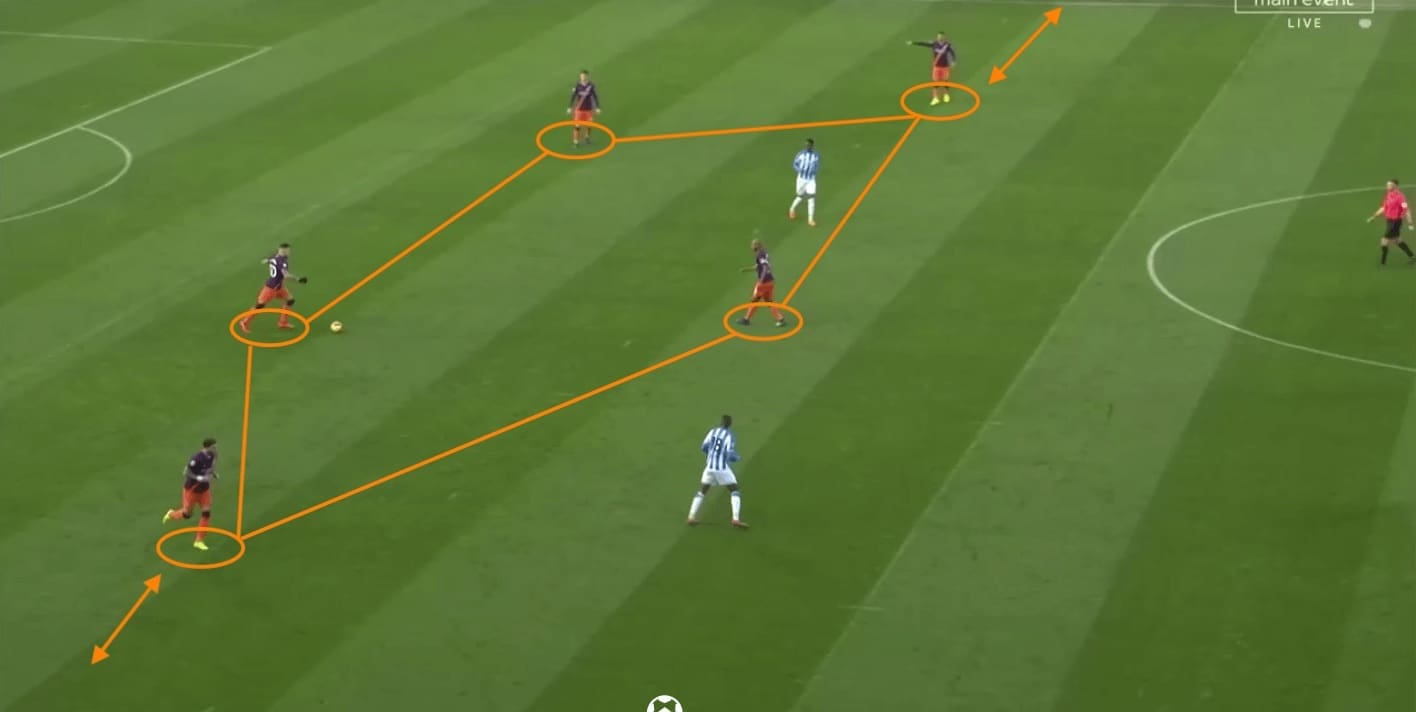

Above we can again see how Man City also create two separate scenarios in each half of the pitch when in the second phase. They start with short passes from the goalkeeper into the central defenders, but where they differ from Chelsea is that rather than push the full-backs forward at this point, Man City create the ‘3-2’ part of the 3-2-5 by squeezing them infield instead.

Notice how this time the defensive-five is made up of the full-backs and one single pivot (Fernandinho), compared to Chelsea’s double-pivot. Ultimately the same scenario in the second phase is achieved in that teams struggle to make high recoveries against this five-man unit, unless they are willing to commit many players to the press. This is high-risk considering the other five players now stationed in the opponents half.

An added benefit for Guardiola by making this tweak is that Kyle Walker can be used in defensive transition. The Englishman’s pace is unrivalled in the Premier League, making him a big asset to have if possession is given away sloppily.

The knock-on effect of using these players in the initial section can be seen below.

Instead of moving inside as they did for Chelsea, Man City’s wingers stay touchline tight, making the pitch as wide as possible. This suits the Man City wide men, in this instance, Leroy Sané and Raheem Sterling, who are natural wingers as opposed to inside forwards (though they are capable of both). As a result, the two creative midfielders – who have the ability to play the incisive passes – take on the positions in the half-spaces. Notice how the 5vs4 has now been created for Man City along the four-man defensive backline of their opposition.

The result is the same. Man City are now asking tough questions of the opposition full-backs, who are trapped between moving inside with the likes of Kevin De Bruyne, or staying tight to the winger and potentially exposing the half-space in behind. Notice at the top of the picture how the opposition right-back has made his decision to move inside. This allows Sané free entry at the back post should any deliveries come into the box.

City rinsed and repeated this two-sided approach in the same manner that Chelsea had done, leading them to 32 victories, 95 goals and a whopping 98 points. Again, it will be known as a successful 4-3-3, when as we’ve seen again, it’s ultimately an updated version of the 3-2-5.

Liverpool 2019/20

Most recently, Liverpool are the side who have adopted their own version of this hidden tactic. This season Klopp’s men reached a record-breaking 99 points, a massive 18 points ahead of rivals Man City.

Known for their rock and roll football spawning from high-intensity pressing and roaring atmospheric comebacks, Liverpool actually secretly introduced their version of the 3-2-5 which many didn’t notice.

Above is a typical starting formation for the Reds, who have many options in midfield, including Fabinho and Naby Keïta who don’t start here. Generally, the most technically sound ball-payer takes up the deeper defensive positioning, the reason for which, we will see below. It is this 4-3-3 shape that they have become renowned for, using it in 85% of their Premier League minutes this season.

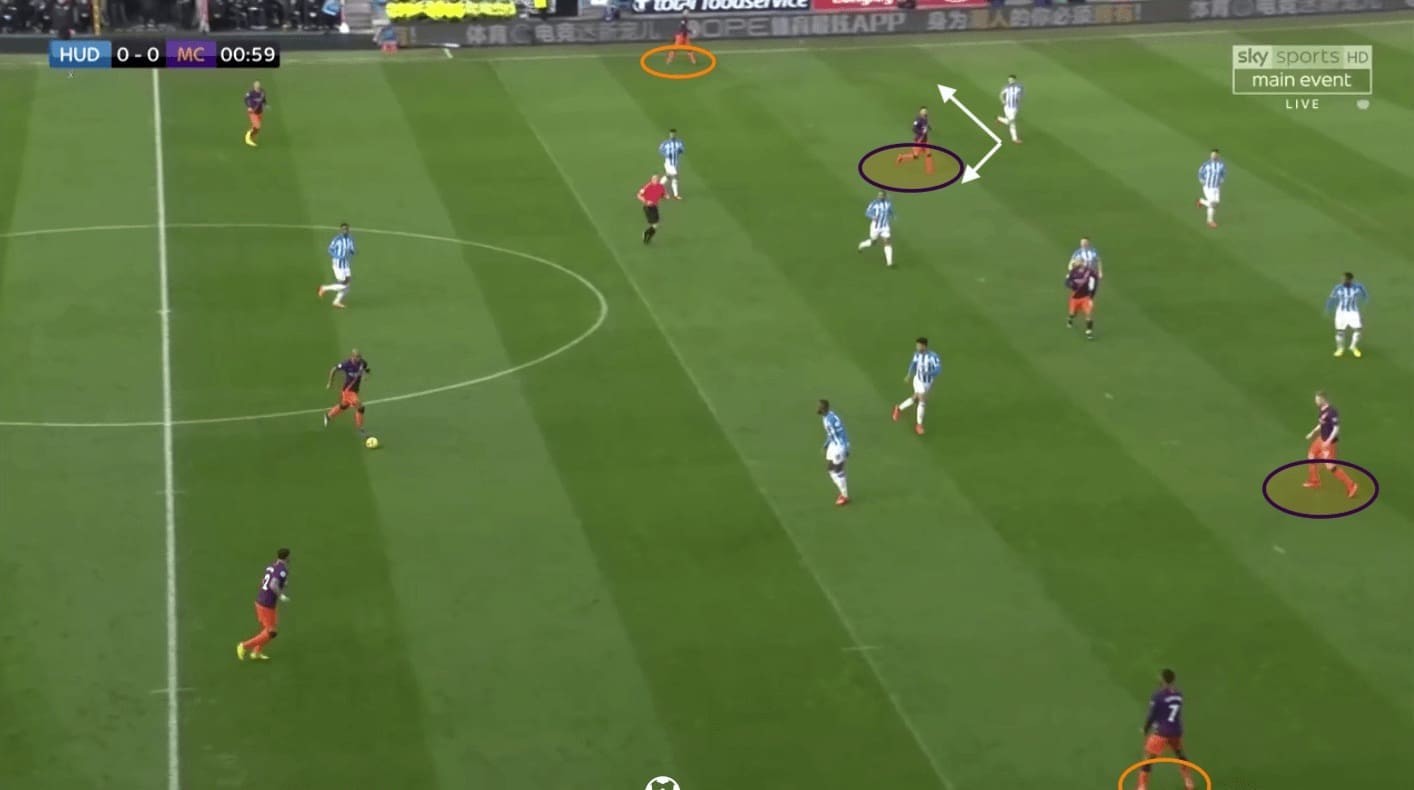

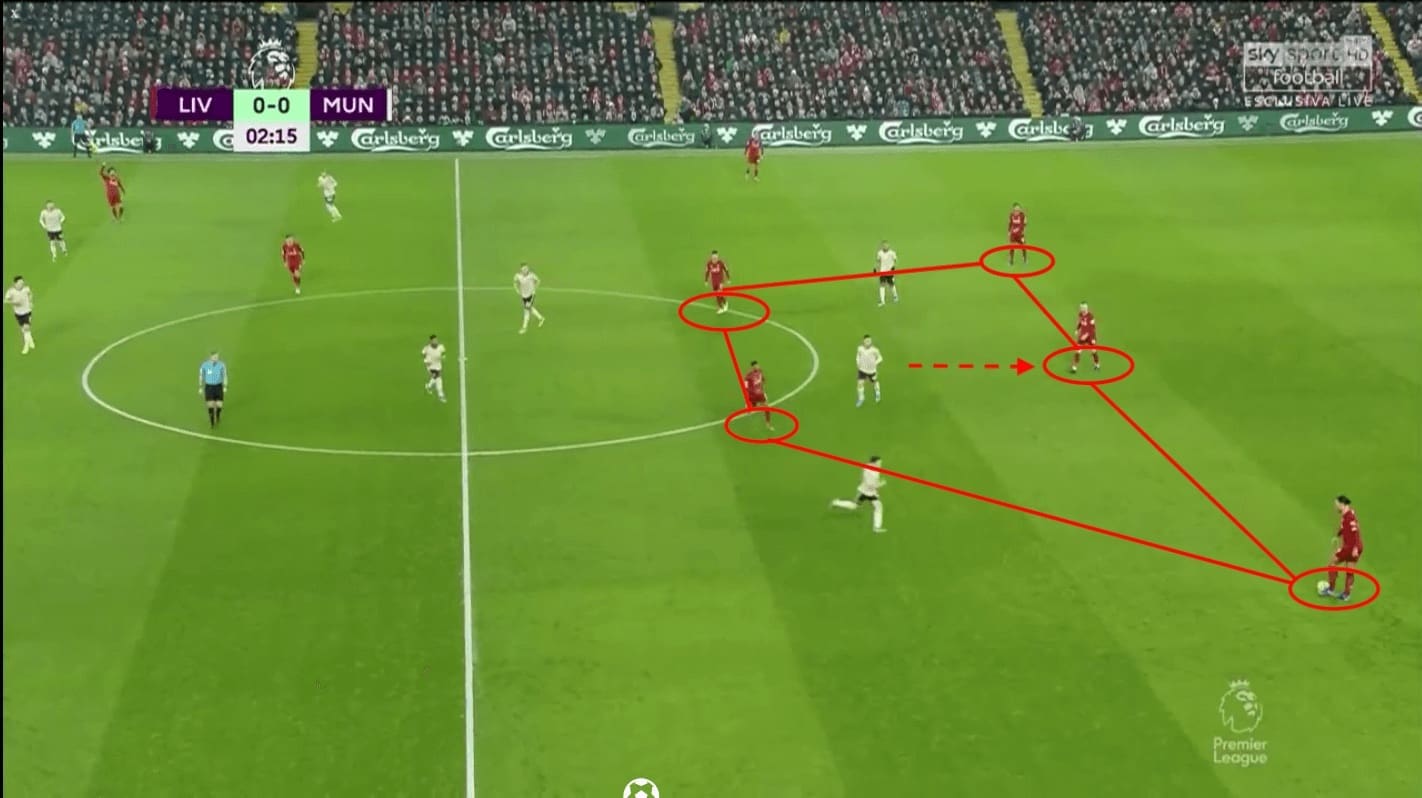

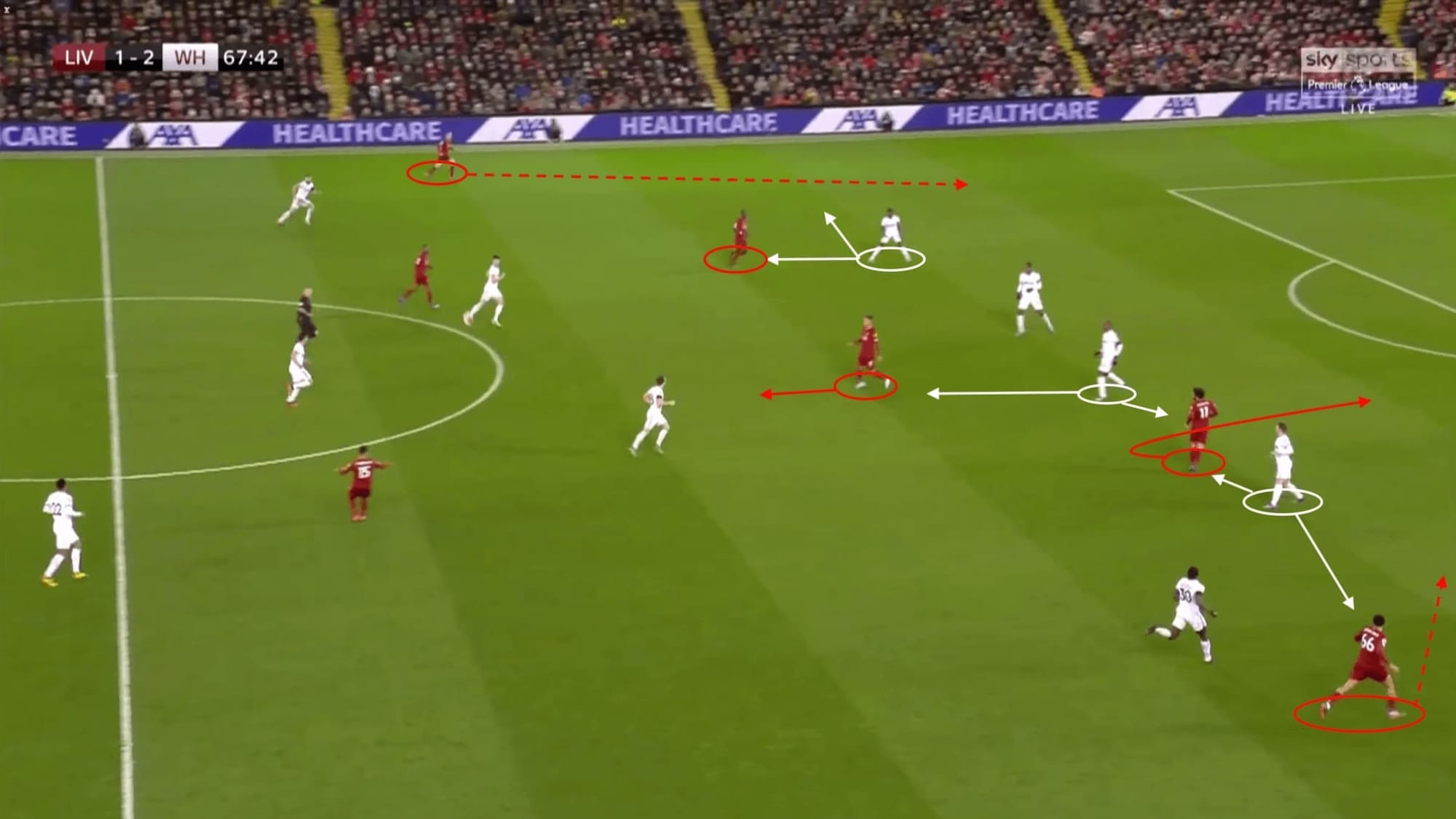

Liverpool use a hybrid of both Man City’s and Chelsea’s approach. In the second phase, they split their centre-backs and push their full-backs high up the field. This allows them to maximise the crossing abilities of their full-backs, who racked up 25 assists between them in the season.

Much like Chelsea, Liverpool use a double pivot to drop deeper to create a five-man unit at the back. Instead of a third centre-back, however, Liverpool use their defensive midfielder to drop into the backline to act as a third centre-back, as can be seen above. Doing this has all the benefits of a third centre-back in the early possession phase but also allows Liverpool to control the game higher up as Jordan Henderson/Fabinho pushes out into midfield once again.

Like the other two, the result is devastating to defend against. In the second ‘mini-game’, Liverpool tuck their forwards inside to sit in the half-spaces – in the same way Chelsea did with Hazard and Pedro. This is complemented by the advancing full-backs who are given full-license to move forward thanks to the five-man unit left in the defensive half.

Where this Liverpool side is better than the Chelsea title-winning side is the added threat level. Liverpool have the benefit of Roberto Firminio, who is technically gifted when receiving the ball on the half-turn. This means he can drop off the defensive line as the other inside forwards penetrate in behind. This gives the opposition another conundrum (as if they needed more!) as highlighted above.

The second improvement is Klopp’s focus on obtaining full-backs with dangerous deliveries. In doing so he forces the opposition to attempt to block the cross, as allowing Trent Alexander-Arnold to cross without pressure is asking for trouble. The result of this – as we’ve seen above – is that it opens space in the half-space, which we can see Mohammed Salah looking to exploit. By picking the right players for this system Klopp has created a rock-and-a-hard-place situation every time the opposition is asked to defend.

This tactic reaped its rewards this season for Klopp’s men, who now have a Premier League trophy to show for their tremendous efforts and imaginative evolution of the 3-2-5.

Conclusion

As the system evolves and improves its fundamentals remain the same; create two separate scenarios in the second phase. In the defensive half, use a five-man unit to safely progress the ball through the pitch. In the offensive half, use a five-man attacking unit to overload the defensive backline.

We’ve seen in this tactical theory article how despite using three different starting formations, each of the teams analysed above have tweaked the 3-2-5 system to suit their player’s technical ability and maximise their output to devastating effect. Whether this hidden tactic continues to dominate English football, remains to be seen. One this is for certain, I’m excited to see if there’s yet another take on this highly successful secret formation next season.

Comments