What Is 4-2-4 Formation?

In recent times, certain formations have become the convention to deploy, as they are conducive to allowing the tactical demands in modern football to be met.

The 4-3-3 formation, for example, somewhat phased out the regular 4-4-2 because of the numerical superiority in midfield.

By extension, the 4-3-3 is actually an ideal formation to deploy for teams who favour a positional play (Juego de Posicion/JDP) approach.

And this appears to be the essence of why formations come into and out of fashion; they are simply a means for a team to access structures and shapes that are suitable when adhering to certain over-arching principles.

A three-at-the-back formation is typically useful for a very rigid, automatism-heavy tactical makeup.

The use of only one nominal wide player on each wing, along with three nominal centrebacks makes lateral rotations very difficult to deploy, and the team is less fluid in that regard as a result.

So it is with great interest that a handful of elite teams have begun to use the 4-2-4 formation.

This formation induces a refreshingly exciting style of play – quite the move away from disciplined JDP systems and rigid three-at-the-back structures.

The 4-2-4 incites fluidity, ambitious front-foot possession play, attacking overloads and physically-intensive pressing.

This tactical analysis article will largely refer to Jurgen Klopp’s new-look Liverpool side as a case study but will also aim to discuss some key distinctions between various 4-2-4 formations.

This tactical theory piece will be an analysis, looking at the 4-2-4 and how top coaches have implemented their tactics within the structure.

The build-up phase

The build-up phase in a 4-2-4 is an interesting case study because the sequential manner of building with the ball, in conjunction with the notion that the 4-2-4 is generally a move away from a rigid possession style, seems rather counterintuitive.

In short, one can interpret that statement as: a 4-2-4 in build-up offers ideal positional and spatial advantages without the limitations of rigid positioning.

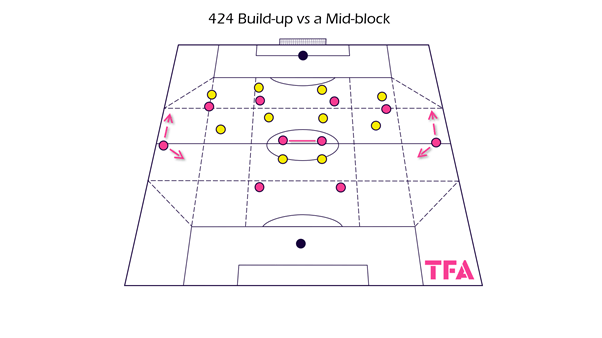

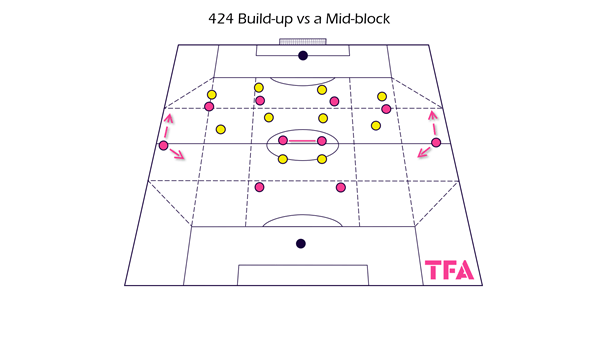

Build-up versus a mid-block

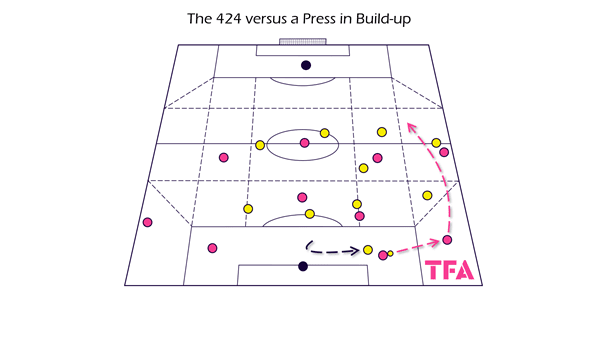

It is important to distinguish the build-up shape of the 424 versus a mid-block and versus a press – the two defensive set-ups are certainly distinct.

The two centre-backs (with support from a ball-playing keeper) form the central and deep base of the build-up.

The midfield double-pivot are another component, strongly linked to each other for a number of reasons; not least to offer a compact rest defence and a strong central core.

The fullbacks are the other relevant component in this build-up scenario – they will generally move in a vertical plane to offer progression angles, as well as offering width which can disrupt the first line of the opposition’s defensive structure.

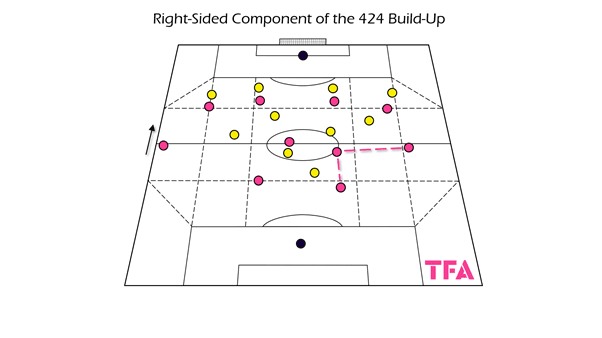

While it is easy to break down the different build-up components into “centre-backs, double pivot, fullbacks”, the other way of viewing the build-up is as a right side and a left side.

Lateral passes are generally discouraged, in both positional play systems, but also overly fluid systems such as the ‘classic ’Red Bull 4-2-4/4-4-2 system.

The right side for example, will have strong passing links from the right-sided centre-back to the fullback (diagonal pass) or right central midfielder (vertical pass).

Similarly, if the ball is switched to the left side, typically through a centre-back-to-centre-back pass, the opposing structure would be created.

Ball progression can occur in a fairly sequential manner in the 424.

What this means is that each pass from player to player induces changes in the opposition shape, which opens a logical passing option for the next pass.

Each player is a checkpoint, in some regards – a checkpoint which is established in a position which forces the opposition to react.

Like placing an opposition’s King under check in chess.

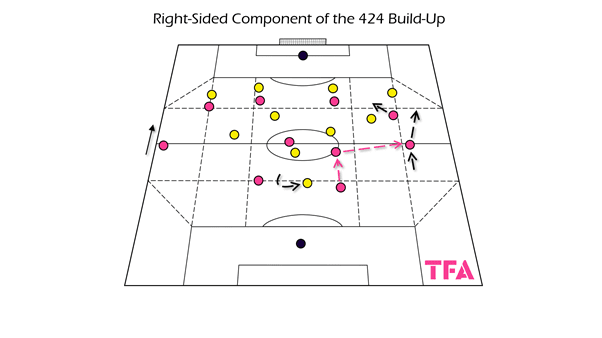

One example of such a sequential build-up is initiated when the centre-back passes into a midfielder.

Being forced to make this pass is often induced by an opponent’s front two playing in a conventional manner; one striker curves their pressure to force play in one direction, the other screens the double-pivot midfielder.

This opens a wall pass into the other double pivot midfielder – who can then play an ‘around the corner’ pass into the fullback.

The fullback can receive with an open body shape and attack space into an attacking area, particularly because the opponent’s left midfielder has been dragged inside by the attacking team’s right winger.

The 4-2-4 is conducive to many of these dilemmas being posed on the opponent’s defensive structure; do players jump to press or sit off and allow the player in ball possession to get their head up?

Perhaps this is a result of the 4-2-4 mirroring the 4-4-2 defensive block so closely or the fact that the defined components (double pivot, vertically fluid fullbacks, etc) can collaborate in any given area of the pitch, just in a similarly congruent manner – unlike in a positional play style where the team is confined to zones and are therefore somewhat predictable.

Additionally, the dangers the front four pose certainly plays a role in disrupting the opponent’s defensive structure.

The threats a dynamic front four can pose are significant, particularly when considering that if the defensive side apply a press, a simple ‘out ball’ can lead to a 4v4.

The predictive threat of the attacking side accessing their front four in this manner means that the midfield line of the defensive team is often preoccupied with screening passes into the front four, which therefore opens pockets for the players in the earlier build-up to progress through.

Build-up versus a press

The 4-2-4 in nature offers a great foundation when looking to play out of a press.

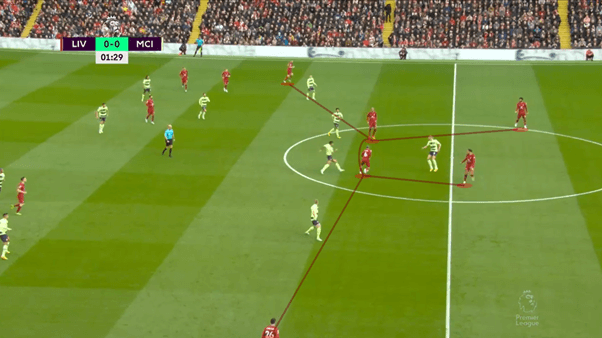

One instance where the 4-2-4 is utilised to play out of pressing scenarios is Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City side from 2021 onwards.

This example is highly pertinent, particularly because Guardiola typically opted for a completely distinct nominal formation in ball possession, with the shape morphing into a 4-2-4 to deal with a high press.

Guardiola seems to have a strong proclivity to avoid a non-JDP formation like the 4-2-4, yet coached his team to revert to it in scenarios where the 4-2-4 can break through high-quality pressing opposition – the 4-2-4 was most notably brandished versus Klopp’s Liverpool.

In the structure, the fullbacks dropping deep and wide is the most evident change, when switching from a 4-3-3 for example.

With the fullbacks dropping deep and wide, the team in ball possession can then have a strong ‘security ring’ in possession, with the keeper plus four defenders all occupying the first line of build-up.

If play is forced down one side by the press, the fullback can often receive in enough space to open their body with their first touch, and play out in a manner which is less conducive to being dispossessed by a presser.

Taking a step back, to a more holistic viewpoint, it could be said that disciplined positional play systems could struggle versus a good, high-intensity press.

A more fluid (almost freeform) system like the 4-2-4 is therefore more adaptable, and the reason for its successes versus a press isn’t limited to numerical/geometric advantages.

The 4-2-4 is conducive to most players having quite a wide scope of movement within the structures – just as the fullback can drop deep + wide to receive in an ideal posture.

Likewise, other players are able to advantage themselves to ensure they have the extra time and space required to execute actions with a higher chance of success when looking to break through the pressure.

The 4-2-4 relies on principles rather than all-encompassing coaching, and this accentuates how adaptable it is.

Principles include, but aren’t limited to, repeated micro-actions such as body shape when receiving in certain circumstances, dis-marking to receive, out-to-in/in-to-out funnels of play and triggers.

Attacking phase and induced transition states

Maintaining somewhat of a holistic view of the game, we can say that football is broadly broken down into four phases of play: ball possession (build-up, progression, and creation), opposition possession, attack-to-defence transition and defence-to-attack transition.

The boundaries between these four sections blur when elite coaches began to tinker with some fairly complex ideas.

Inducing a transition-like state is something that can occur when you bait a press for example.

Encouraging the opponent to press the team in ball possession drags their structure up the pitch – and they’ll likely take risks in ‘jumping’ on an individual level to press when the carrot of regaining possession in what would be their attacking third is dangled in front of them.

The result for the ball possession side when inducing this situation is a manufactured state of defensive disorganisation to exploit if they can break through the pressure.

The features of the 4-2-4 make this formation ideal to 1) bait a press and 2) play out of the press.

These features are touched upon in both of the build-up sections above, as build-up is where baiting an entire defensive structure up the pitch to press is the most effective – the defensive line is simply dragged the furthest up the pitch and this either creates more space in behind or leaves space between the lines.

The means of baiting and playing out of a press are one side of the coin, having a form of superiority in attack is the other side, when discussing how to exploit defensive structures in an induced transition.

Quite simply put, having a front four to capitalise on transition-like attacking scenarios is highly advantageous – it goes above and beyond what you’d normally expect from a team going forwards (typically you’d have a front three, or a few players on the break – but rarely a highly organised front four).

The profiles in the front four differ from team to team, and on an individual level.

It can be ideal to have a #10 and a striker, with two wingers (Pep Guardiola typically utilises this when his side reverted to a 424 vs Liverpool, with De Bruyne being the #10 and catalyst to bring the ball into final third situations).

Liverpool utilise Darwin Nunez well, as a disruptive striker, but are still reliant on inverting wingers such as Salah to be the clinical goalscoring edge.

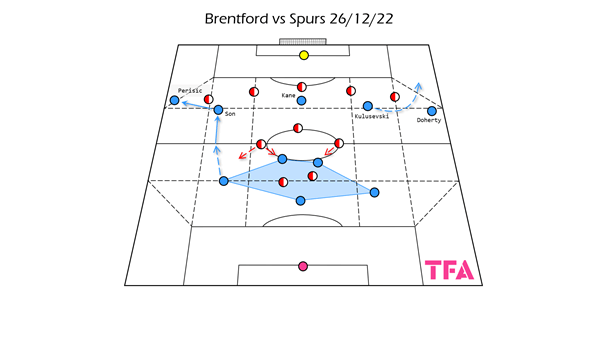

Many teams use a front five, in a 2-3-5 or 3-2-5 formation, and while a front five has advantages stretching opponents laterally, they are often quite rigid and easy to defend against if vertical movement isn’t too pronounced.

Most recently, Spurs struggled to access their rigid front five versus Brentford – in the 424, dynamism and socio-relationships between players are generally more conducive to fluid, destructive, attacking play – although a degree of this stems from the disruption induced by the build-up.

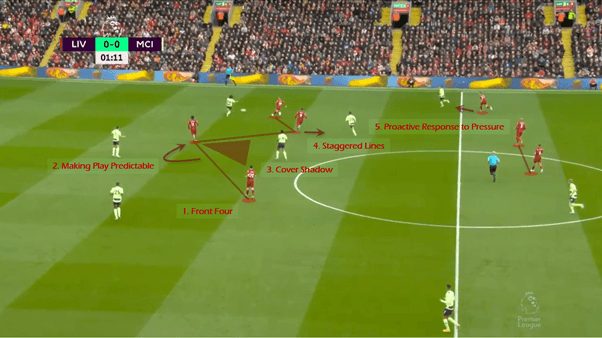

The 4-2-4 is also quite an ideal formation when it comes to deploying a conventional type of press.

For example, when in a settled phase without the ball.

In short, the front four is optimised to apply pressure from the front – the two central members can build a relationship just as strikers would, with one pressing and the other using their cover shadow to block off the opponent’s #6.

The pressing striker can also force play down one half of the pitch, making defending more predictable, while also inducing the opponent to play into a trap.

The fullbacks in the 4-2-4 can push on to pin the opponent’s wingers back, while the double pivot can advance up the pitch in a compact manner, acting as a defensive screen, blocking off the opponent’s front line.

The 4-2-4 is certainly conducive to a strong defensive shape, providing the team is well-coached and has an understanding of when to press and when to settle into a 4-4-2/4-2-4 mid-block.

Conclusion

The 4-2-4 is a perfect antidote to the rigid positional play systems that have become synonymous with elite modern football.

It is dynamic, it is conducive to organised chaos, and most importantly the positional versatility it offers allows it to cope with highly organised defensive systems, both high pressing and well structured blocks.

It is worth noting that the 4-2-4 isn’t for everyone.

Pep’s iteration of the 4-2-4 hinges very much on the brilliance and press resistance of Bernardo Silva, alongside the physical spine of the team in Rodri.

Liverpool are a second-ball-winning juggernaut – physically imposing and intense, and this allows them to cope with the duel scenarios a chaotic 4-2-4 can create in a game.

Fullbacks who are smart in movement and strong in execution are a must because they’re often the ones to play the ‘out balls’ – while the front four need to build a complementary relationship with each other.

The 4-2-4 does give rise to a plethora of strong, natural angles to play through from build-up to creation, but an interesting thought for the future could be how a similar (or different) formation could offer the same benefits when taking down elite, tactically-conventional sides.

Comments