Like millions of sports fans around the world, I too watched ‘The Last Dance’ documentary and took many things from it, one being a renewed interest in basketball again. Basketball is something I have used in my football coaching sessions at times, and the similarities in the two sports are often stated, but rarely explained. Pep Guardiola was said to have conversations with Bayern Munich’s basketball coach while in Germany, while basketball players such as Steve Nash and Steph Curry have a keen interest in the sport, with Curry said to watch Barcelona to develop himself. Therefore, on the back of a basketball binge in the past month, I decided to detail some tactical similarities in the sports and how we can use basketball concepts to benefit our football, particularly in offense in this article. I have to give credit to the fantastic Ben Taylor and his book and YouTube channel ‘Thinking Basketball’, as well as Coach Daniel on YouTube, who’s content has given me many of the basketball concepts in this analysis. I should point out this is a strictly open play based article, with the transfer to set-pieces much easier and simpler than open play. In this tactical analysis, we will mainly focus on the various aspects of positional play and space utilisation in basketball that can be transferred into football, with various schemes detailed and transferred into a football setting.

Differences

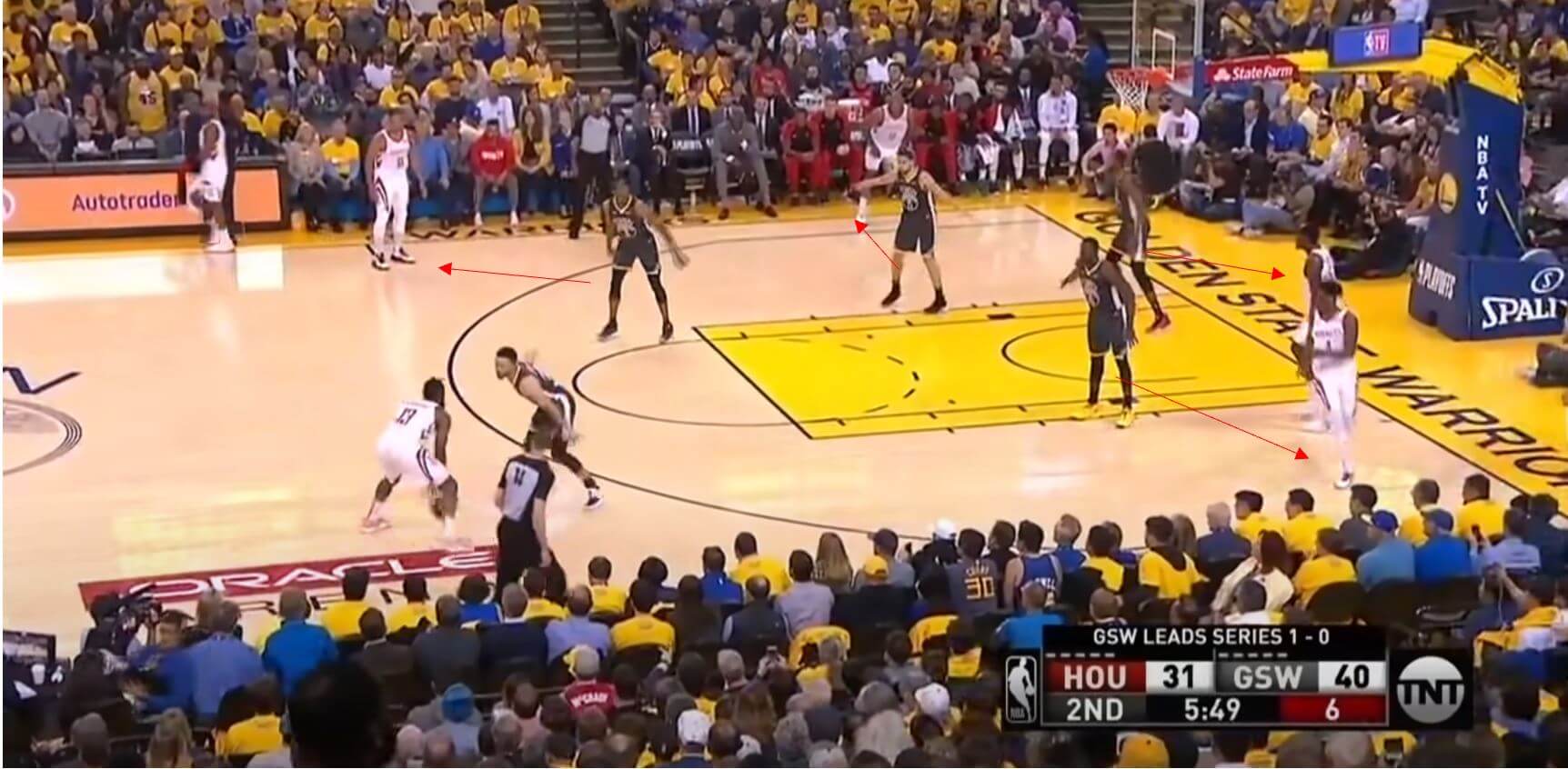

Before we set out areas for transfer to occur, it is worth pointing out the differences in the sports which give us challenges when trying to apply concepts across sports. The first major difference in basketball that impacts this article is individual ball possession. In basketball, if a player stands still with the ball in both hands it is very unlikely they lose possession by having the ball stolen, unless they are up against a particularly good and aggressive defender. Instead at times you will see players hold it in both hands moving the ball around in the air, preventing a steal and looking for passing options. Therefore, theoretically, a player can retain possession for 24 seconds with a defender directly in front. This is of course different to football, as having the ball in two hands is obviously not the same as having the ball at your feet. As a result, isolation plays such as this one below involving James Harden can’t occur in open play build-up, as the risk of the player in front tackling is far greater. The spacing concept is one that can be transferred easily, with this offense called an isolation offense because the Rockets space to isolate Harden and his defender Curry.

Basketball as a general rule is also much more man orientated than football is. In the image above players may space themselves in zonal man orientation, so that they remain close to their player while still covering a specific area, however players are still generally tasked with matching up against one player and following them, no matter their position on the court. This is more possible due to the number of players and space on a basketball court compared to a football pitch, as it’s easier to follow a player across a shorter distance and on a court which will leave less space behind when you do. Teams do use watered down versions at times, but it is too simplistic and generally, the more man orientated a team is the more disorganised they tend to become. Ernst Happel once said, “If you mark man-to-man, you’re sending out eleven donkeys.” Complete zonal defence does exist in basketball but is far rarer, with rules around standing in the same area forcing players to move, and the threat of distance shooting both impacting.

As a result, dismarking is a common concept in basketball, and is a massive one which applies to football tactics, but the methods and frequency at which you can dismark in football is different. For example, here we see Steph Curry move backwards behind a double screen set by his teammates. His teammates are both marked and Curry moves from high to low, where his marker tries to follow but is physically blocked by Curry’s teammates. In football it is difficult and often illegal to block players from physically running to an area, but we can use positioning to apply the same concept without the physical concept. These are just some of the slight differences which affect this piece and worth considering before we get into the detail.

The concept of gravity

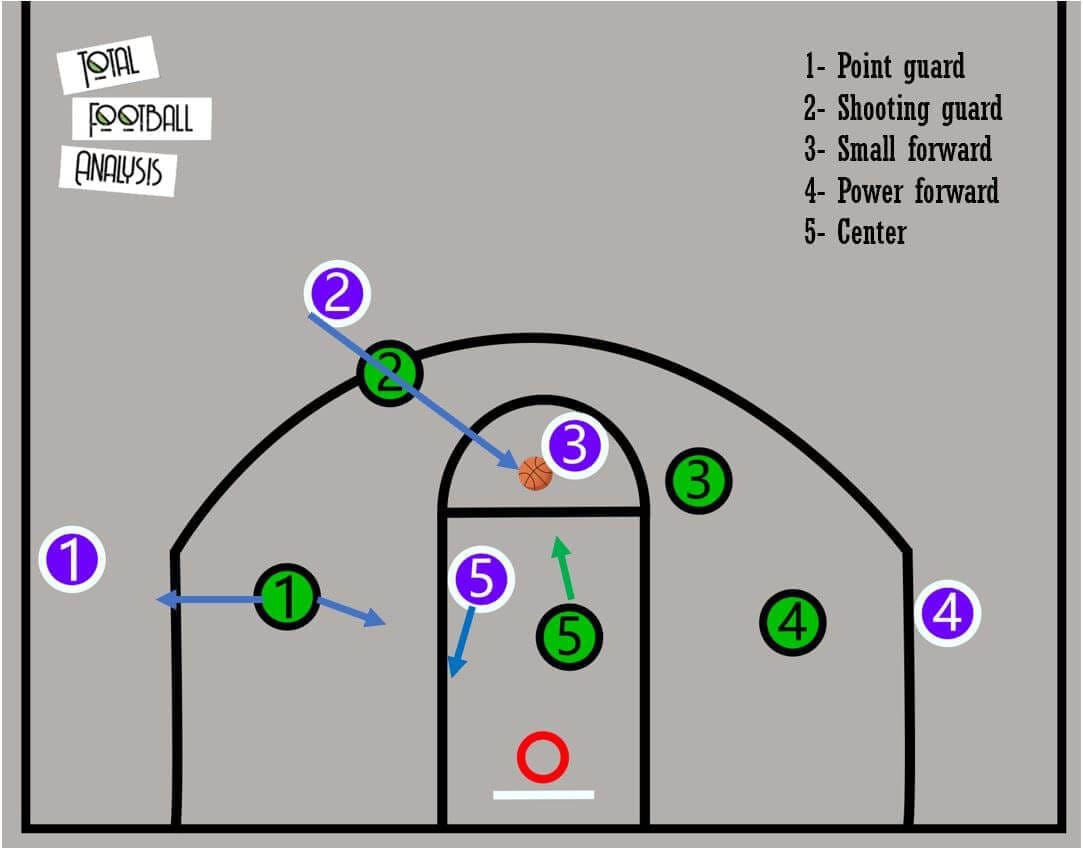

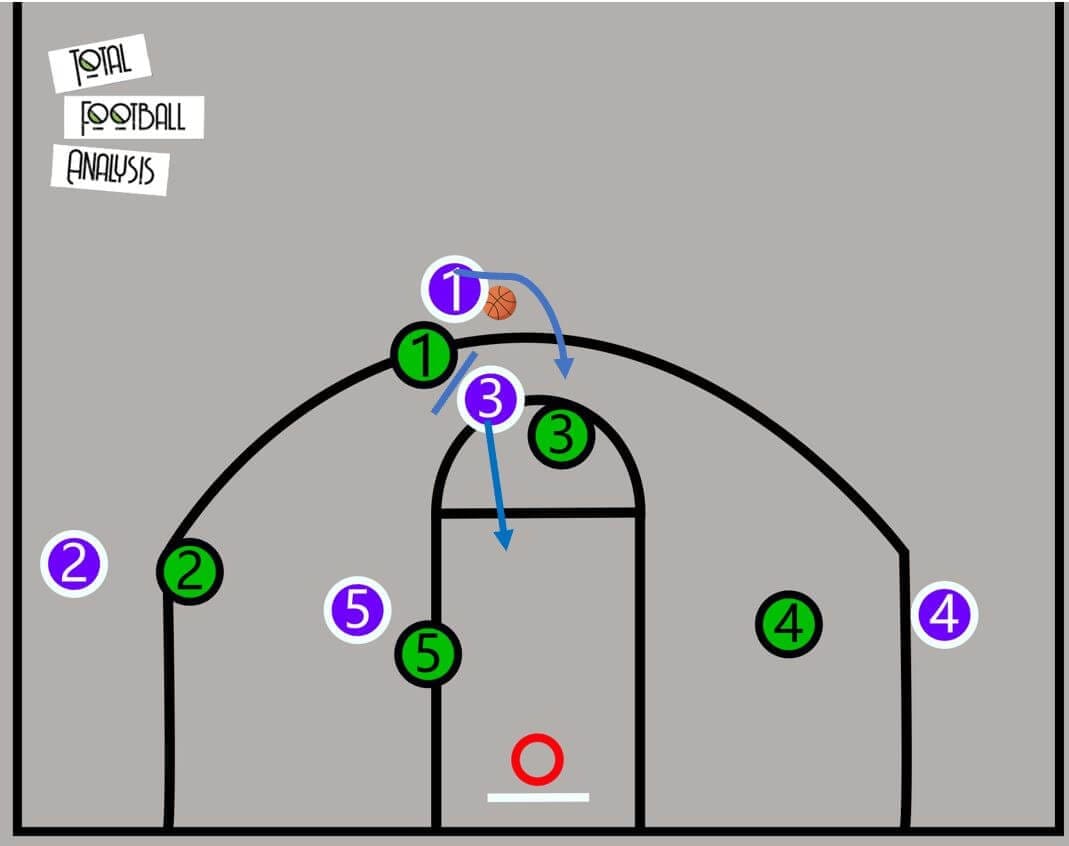

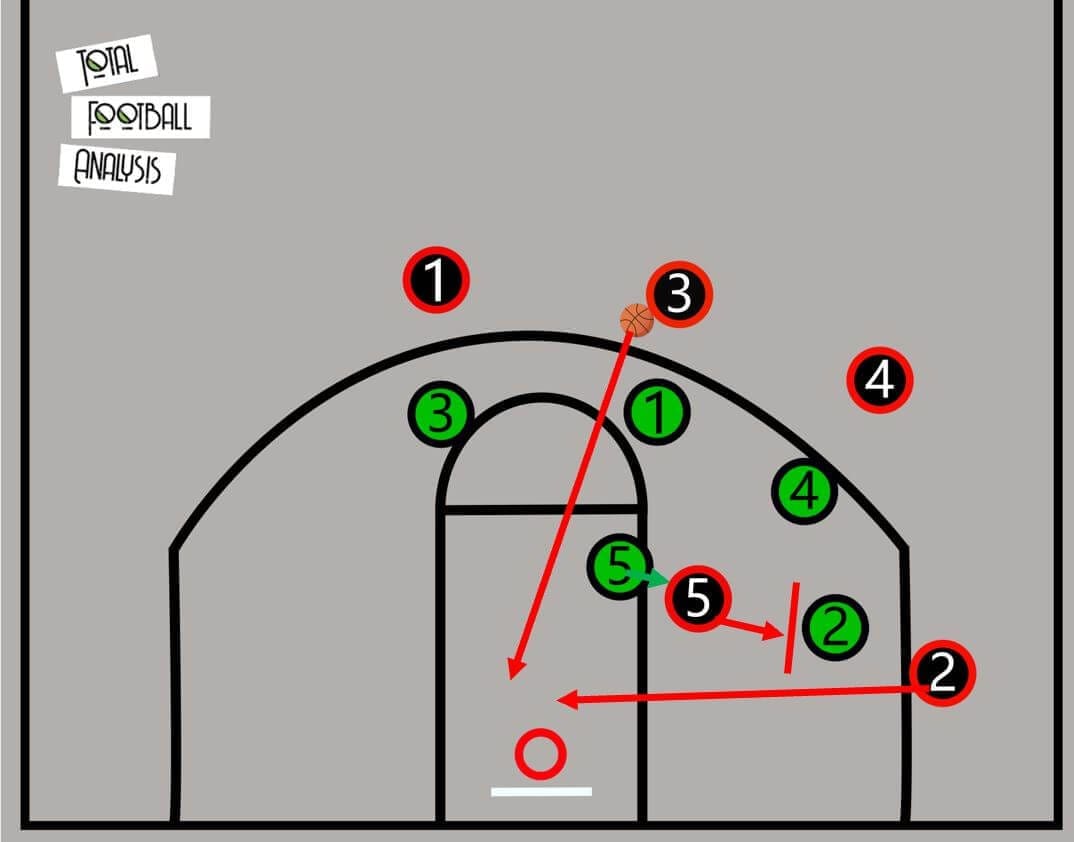

The first similarity we are going to look at is the concept of gravity. This is defined in basketball by Kevin Felton of ESPN as: “the tendency of defenders to be pulled to certain parts of the floor” with every offensive player said to possess their own gravity. We can see an example of how this works below in this theoretical example. Here the ball has been passed to the free-throw line area, with number three (small forward) losing his marker to receive the pass. As a result, you now have a decisional problem and an overload, with the green three basically out of the play. Therefore, the five has to move forward (or as I call jump) to prevent an open shot for the green three, however the player must also consider the positioning of the initial marker, who now moves towards the basket away from his marker. If the five moves forward too much, the ball can go over them, and if they don’t move forward enough, a shot is open. The ‘gravity’ of each player is effectively the distance their defenders stay from them.

If we look at the green point guard (number one), they are also impacted in this decisional problem, as they have to consider their distance from both their marker and the basket. Again, go too close to the wing and the centre becomes open, and go too centrally and the wing becomes open for a higher value shot.

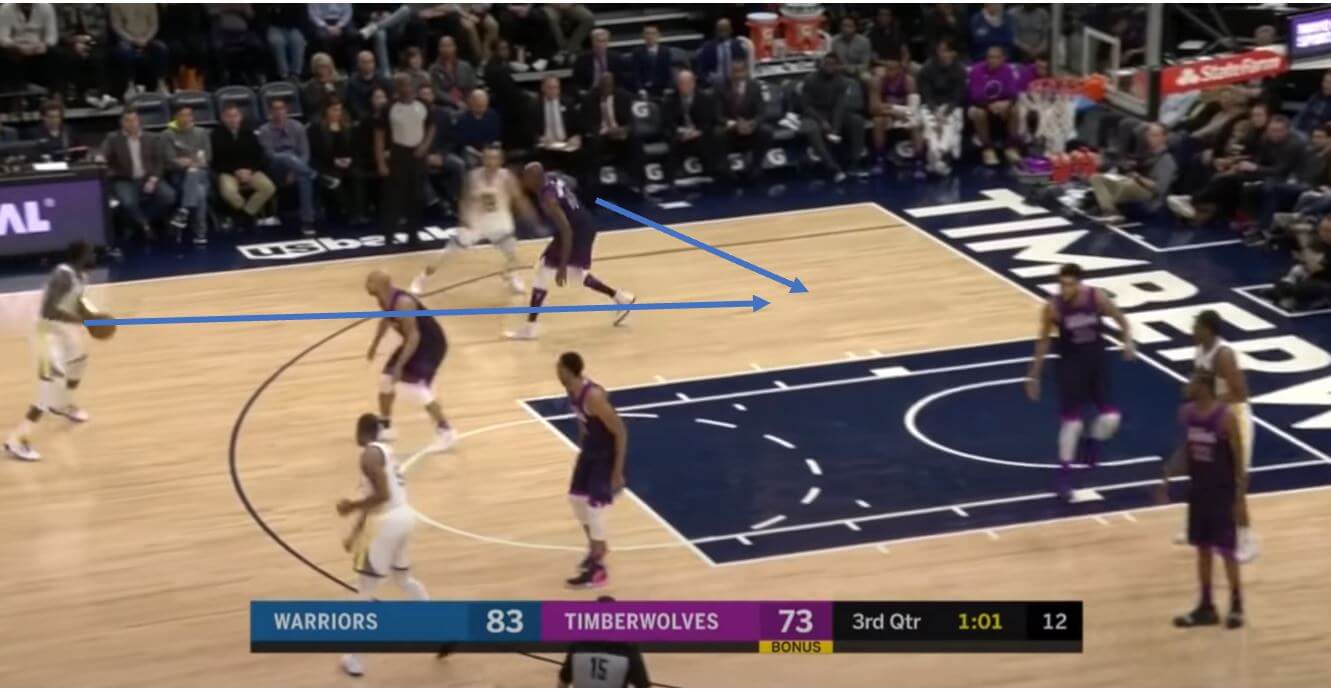

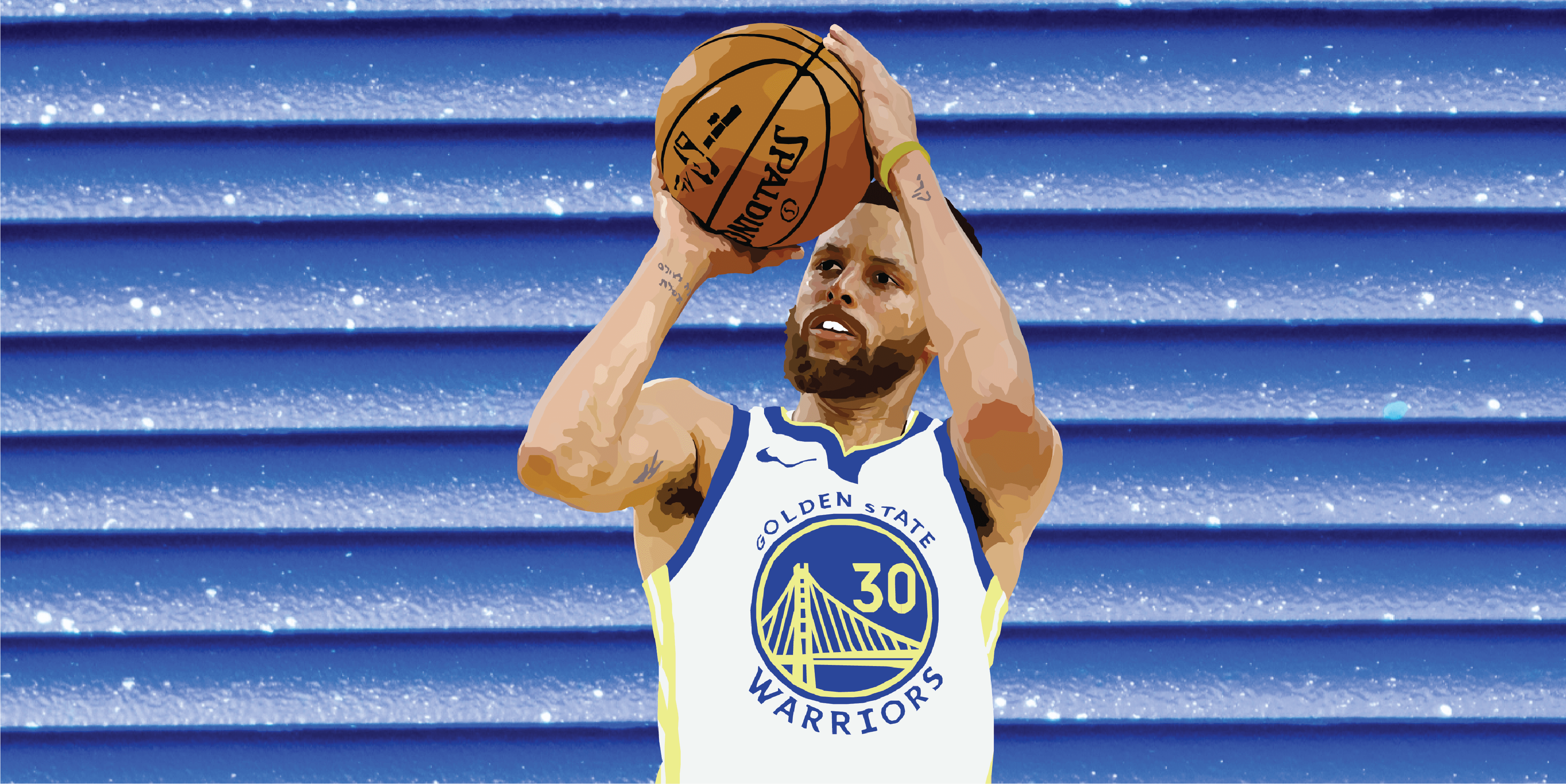

If we then bring personnel and pitch/court location into the matter, decision making of defenders is impacted. Here, Curry, the greatest shooter of all time, moves to the three-point line from deep. The defenders stay closer to Curry, or gravitate towards him, as they view him as the bigger threat or priority. As a result, they leave another lane open and Golden State gets an easy basket.

In football this applies extremely well in positional play, with the concept of pinning and creating overloads a common idea.

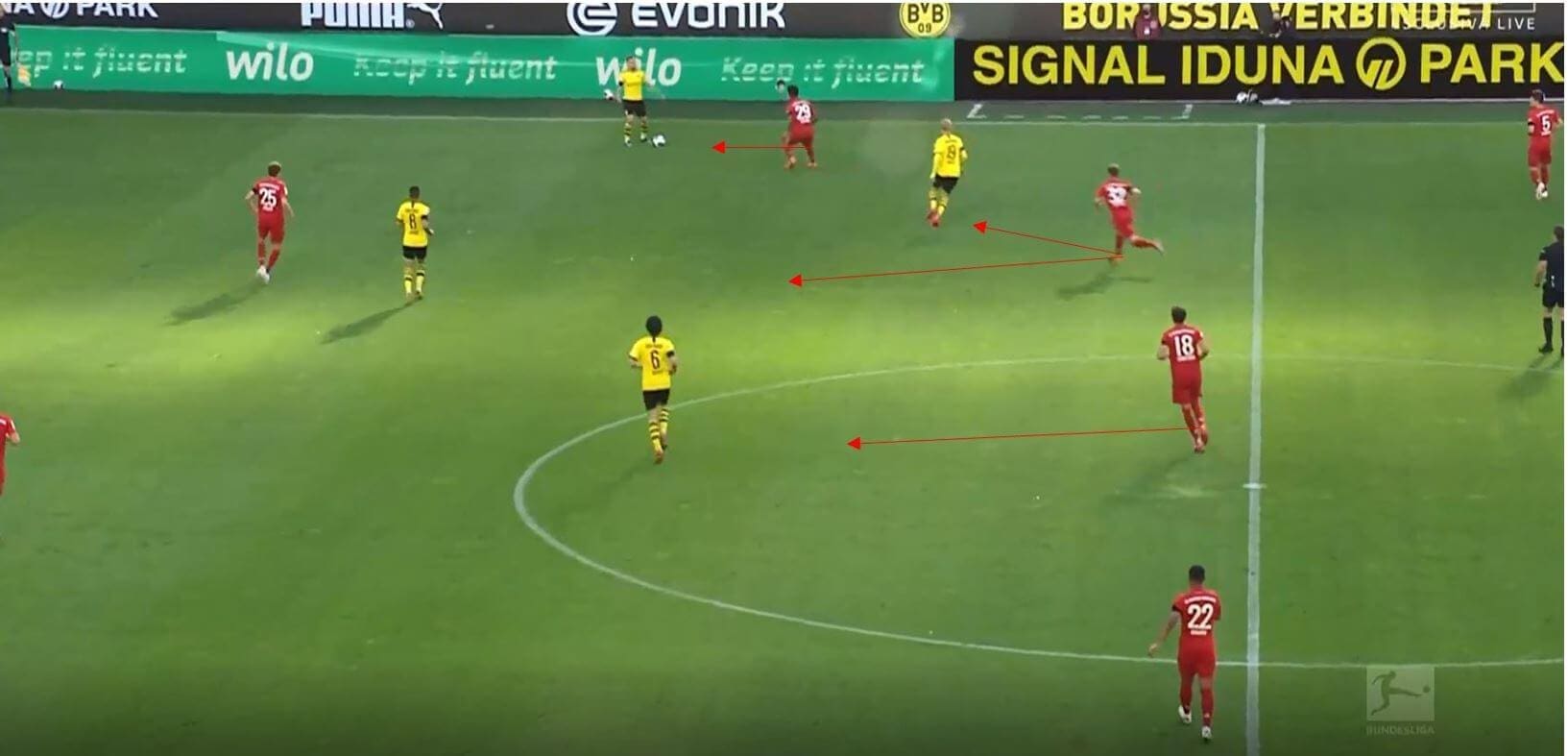

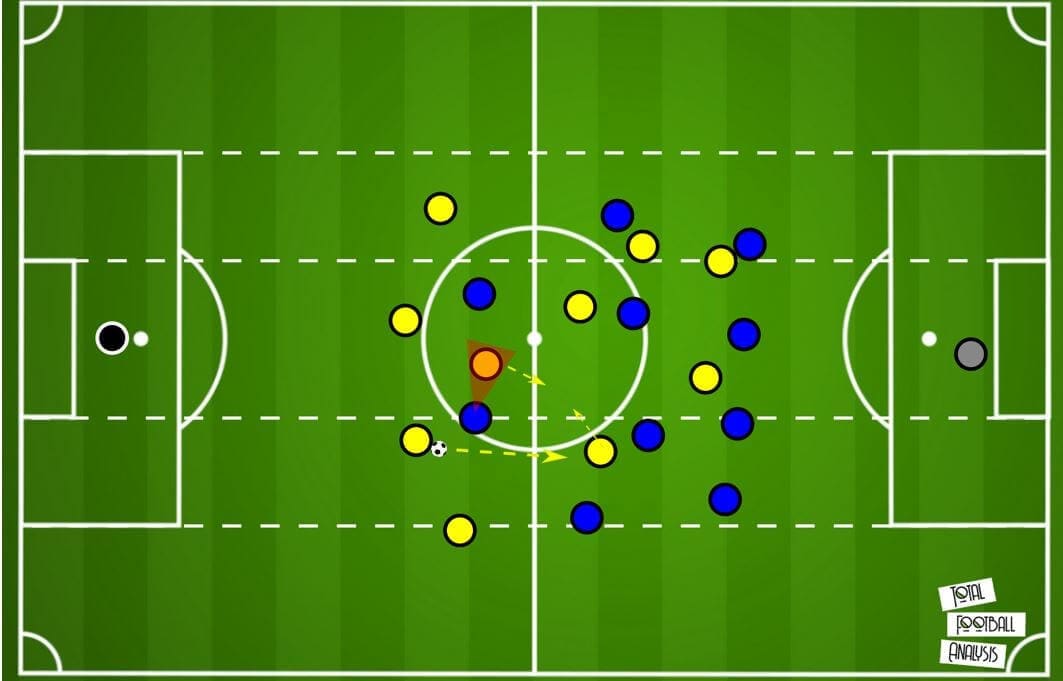

We can see an example of an overload and decisional problem here, which Borussia Dortmund created against Bayern and Schalke recently. Here when the ball is played wide, Joshua Kimmich has two players to press and so an overload on him is created. His midfield partner Leon Goretzka cannot come across because of Dahoud’s positioning (gravity). If Kimmich commits to the nearest player Julian Brandt, he leaves the far player open, and vice versa if he commits to the far player. If Kimmich commits to the far player, the right-back in the image may jump in, but that then leaves gaps elsewhere, showing this kind of chain reaction that overloads create. Therefore, Kimmich has to try and find a happy medium which allows him to react, and this distance that he opts for between each player is as a result of the opposition player’s gravity.

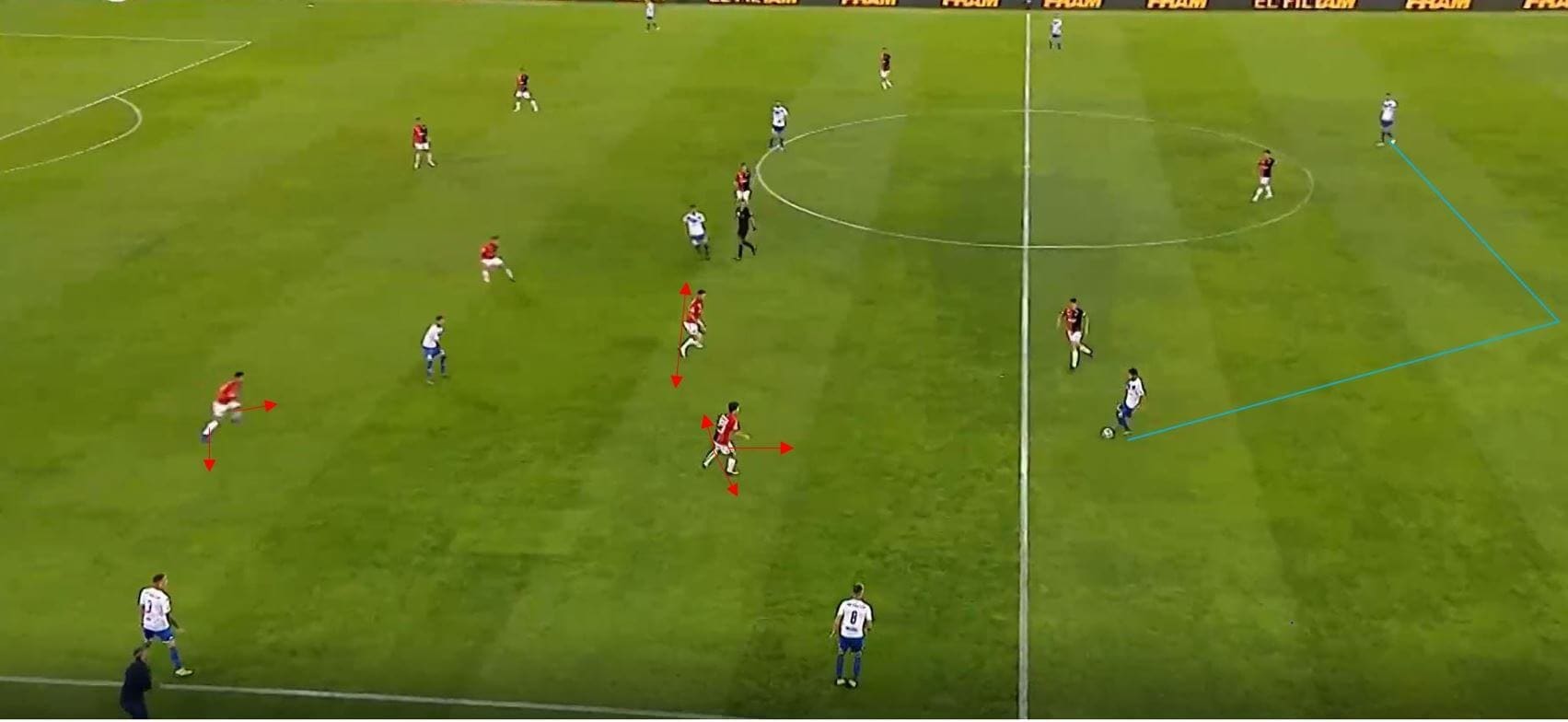

We can see an example of positional play affecting decision making of the opponent and creating problems here, with Gabriel Heinze’s Vélez Sarsfield. In a back-three, we see the decisional problems firstly on the opposition right-winger, who potentially has to engage the ball carrier, while remaining in a position which allows him to press the wide player if needed, but also allows him to protect the half-space somewhat. If we look along the chain to the nearest central midfielder, he has to also consider the half-space, while covering the central option. The full-back also has to cover the half-space and a potential wide pass. This positioning causes problems for defenders and can sometimes leave them in no man’s land, where they commit neither one way nor the other and can’t do much.

We can see here in a structure that Manchester City often use, decisional problems on several players allow City to play through. Here, the full-back provides width while the inside forward occupies the half-space. The opposition’s right-winger can’t move wide or they open the half-space and can’t commit too centrally or leave the wide area open. Likewise, the central midfielder can’t do the same, while the centre-back can’t push forward straight away to mark, as this would offer space in behind for the striker. Of course, the more players committed in higher areas, the easier it is to create an overload.

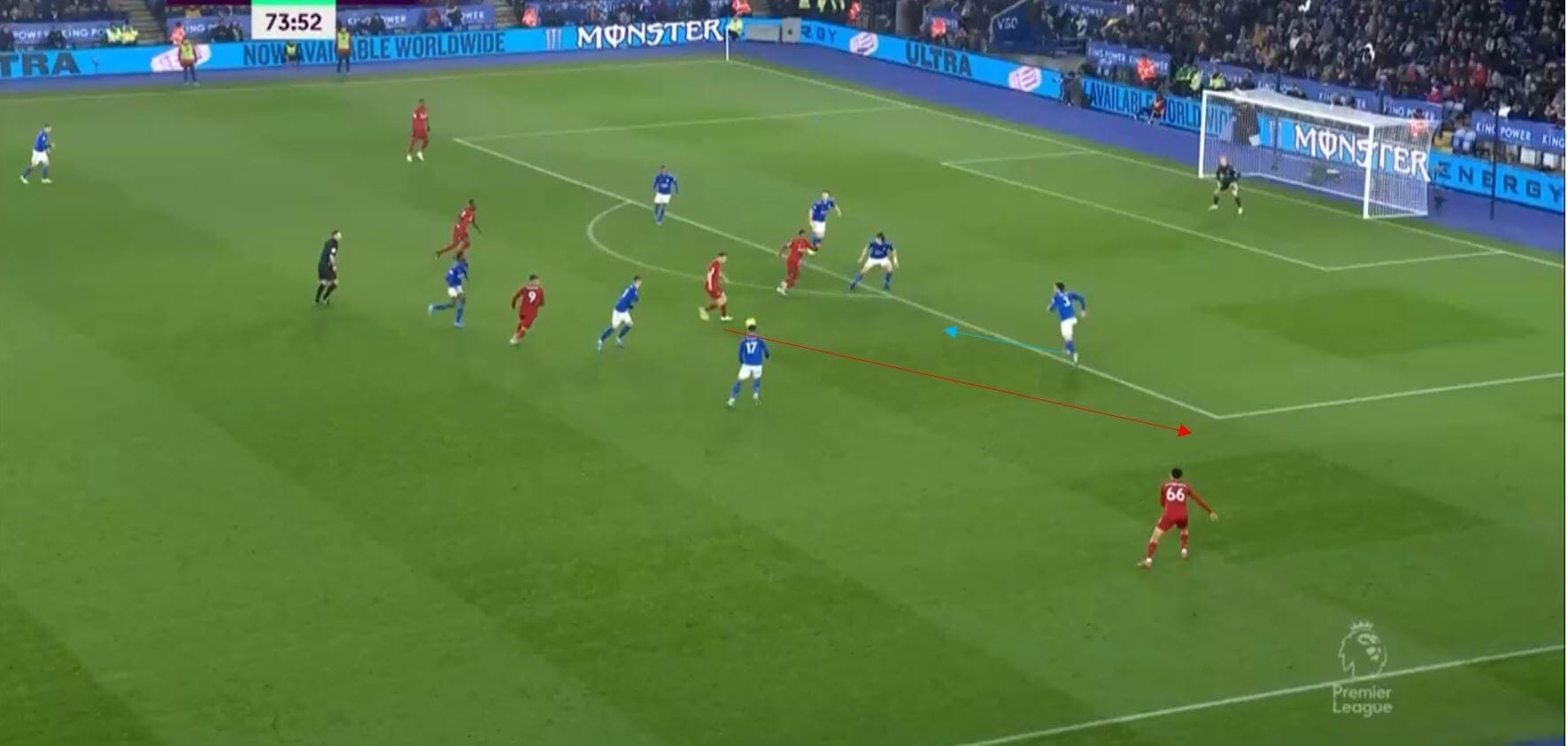

Therefore, if certain players have particular characteristics, or the ball is in a certain area, the defender’s decisions and gravity will be altered. We see here, Liverpool are able to access the central area through Milner and have the opportunity to shoot on goal or maybe just play in behind. As a result, Ben Chilwell moves across to cover the area and increase compactness. This then increases space on the wing for Trent Alexander-Arnold, who you could argue has a higher gravity than Milner in this situation, although Milner’s gravity in this situation has increased due to the position he is in. The best teams have multiple players with high gravity in high gravity areas, and so choosing which one lane to cover in a split second is very difficult. Liverpool for example have players who can play in tight areas in the middle, who can play wide and deliver crosses, and who can run in behind using pace. Here Liverpool play the ball wide, and Alexander-Arnold delivers an excellent cross for an assist.

This is very comparable to this scene here, with the only difference being the method in which pressure is attracted. Here, it is a dribble from the player which attracts pressure, which is also very comparable to football. Here, the defender half occupying the wide area, moves in due to his teammate struggling to defend. As a result, the on-ball player can dribble and then shift a pass to the wing, for a three-point shot. Chilwell faces the same dilemma as the defender here.

Here again we see a dribble attracting pressure and creating space elsewhere, with gravity playing a factor again here. Kevin Durant is on the ball, one of the best mid-range shooters in the game, while Curry is on the three-point line. The defender looks to fill in to prevent Durant driving or creating space for a shot, but at the same time then increases space for Curry. In football this is slightly different as shots obviously aren’t as common, and so Chilwell in the example sacrifices the crossing area inadvertently to one of the best crossers in the Premier League. If Liverpool had full-backs who couldn’t cross or drive with the ball, teams who find it much easier to defend as they could close the half-space more and leave more space on the wing.

We can see here Andrew Robertson completes one of his signature driving runs down the line, where he here attracts the full-back to press. This leaves Sadio Mané wide open in the half-space to receive, with the opposition full-back’s timing of his challenge here poor, jumping in and being left in no man’s land, with him unable to stop the attack at its source, or cover the player behind him.

The best defenders use their timing to jump at the correct time, and therefore keep the gravity of the attackers as low as possible. We can see here, Virgil Van Dijk occupies the lane to the player threatening a run in behind, while also remaining in a position to jump to help tackle the dribbler. Van Dijk stays covering the lane and senses an opportunity to jump in when a heavy touch is taken, winning the ball. Excellent defenders know when to jump and what position is best to take up, with basketball players such as Draymond Green being excellent examples of this. This kind of example of good defensive decision making can of course also happen in higher areas such as in pressing.

Pick and roll

The pick and roll, along with its multiple variations, is a common way for basketball sides to create overloads and find space to drive to the basket. A pick and roll is simply one player setting a screen by moving forwards (pick) for the ball carrier, before then moving (rolling) towards the basket. We can see an example of this here. The small forward (three) moves forward and occupies the man marking the ball carrier. As they move forwards, they are also followed by their marker. The small forward screens the on-ball defender, while the ball carrier then moves around the screen with the ball, now occupying the screener’s (pickers) marker. Therefore, once the player has set the pick, they can move forward unmarked, thus creating a numerical advantage as the initial on ball defender is rendered useless on the play.

We can see here Nikola Jokić sets the pick for the ball carrier, which prevents the on-ball defender from staying with his man effectively, therefore forcing the nearest marker to jump in to mark and stop a drive. Consequently, Jokić can just drive to the basket and look for a lay up or a pass to one of his teammates. Other pick and rolls can involve three players such as a double drag, and not all pick and rolls lead towards the basket, slipped pick and rolls can lead to three pointers and pick and fades to mid-range shots.

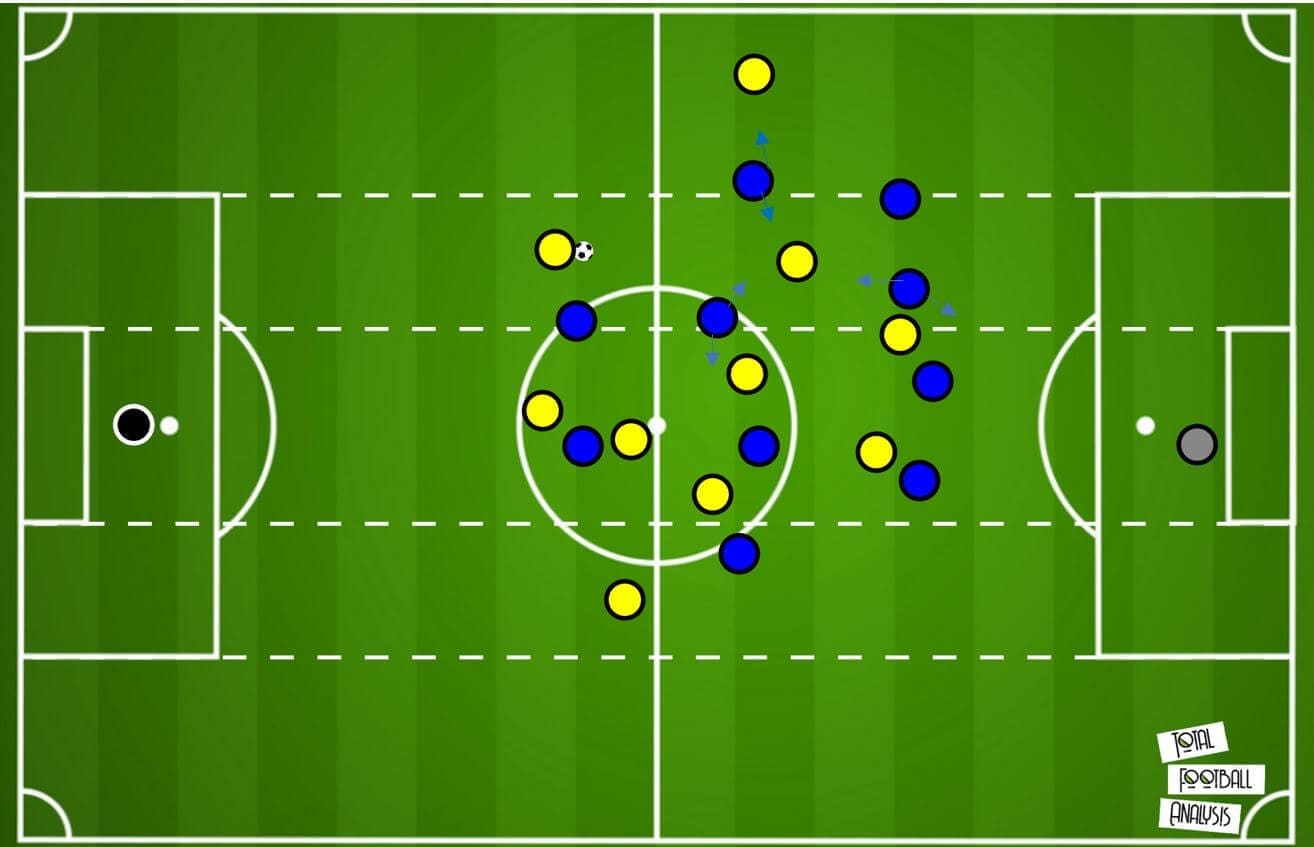

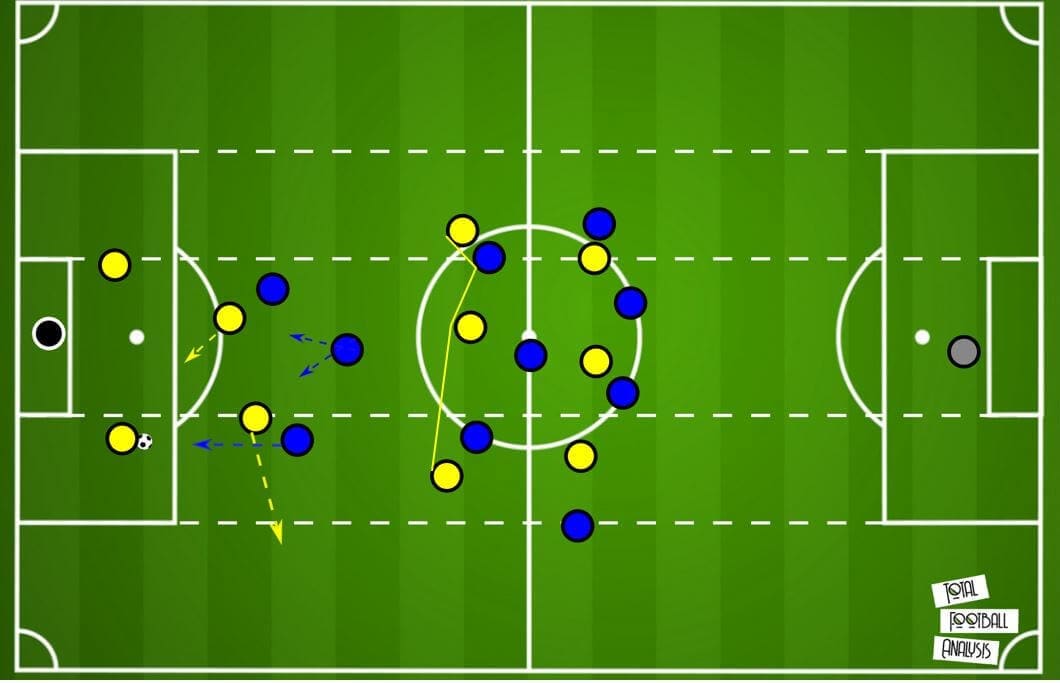

The process of the pick and roll is easier to translate into football when broken down. When broken down, a pick and roll involves player X occupying the on-ball defender, while the secondary defender becomes occupied also, creating a free man when player X moves away from the initial on ball defender. Therefore, this concept applies well here in build-up, where we can use the cover shadows of opponents to create numerical advantages. Here, the central defender has possession, and a deep midfielder threatens a central pass, meaning the striker adjusts their pressing run to keep the midfielder in their cover shadow. The half-space is open for a pass, and the player initially helping the ball progression of the defender can move to receive an open pass, creating a 3v2 overload in central midfield thanks to the third man concept.

This means that in this play, the on-ball defender is occupied by player X, and the secondary defender is also occupied, with the pass equating to the dribble seen in the basketball pick and roll. The central defender could dribble to attract pressure from a marker, before passing to the free man created, but in football this is far riskier and difficult. Once the second defender becomes occupied, player X can then move forward to create a numerical advantage.

This concept of moving from a marked position/cover shadow into an unmarked area is one which is able to be developed, and the concept of pinning which also exists in basketball can be used to benefit this. Here we can see build-up from the goalkeeper, with the full-backs inverted and initially unable to receive due to being next to the pressing strikers. The left sided inverted full-back can move centrally, creating a decisional problem, while the two strikers would press the centre backs. As a result, the right full-back becomes free, and the opposition midfield may struggle to press due to the pinning of the midfield.

The key aspect of translating the pick and roll to football in open play is that we can’t simply block players in order to stop them pressing, but we can occupy players to force an adjustment which can later be manipulated, which is the same concept as a pick and roll.

Cuts

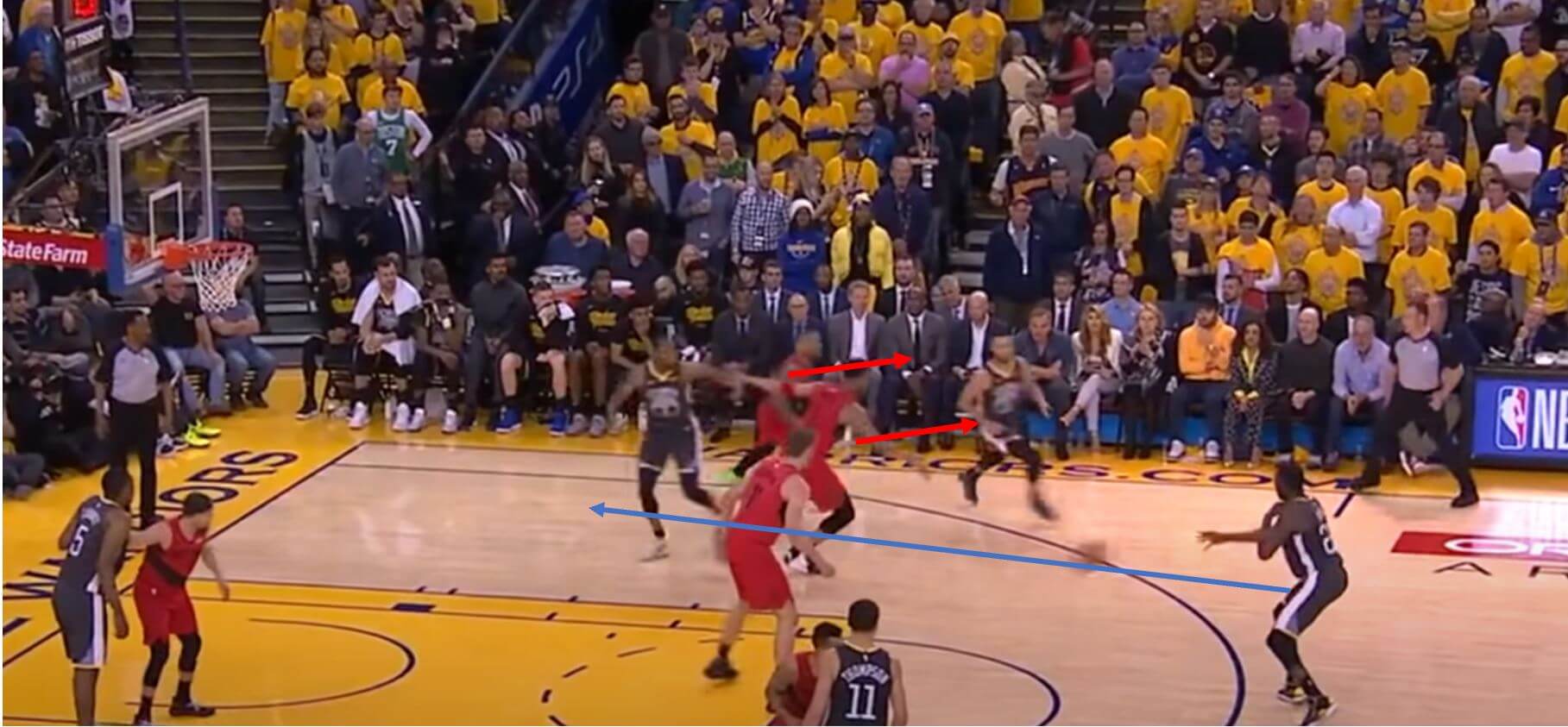

Something which Guardiola is said to be keen on is the use of a backdoor cut, a concept taken from basketball. A backdoor cut involves a player moving behind the opposition defence, usually from the wing to towards the basket. We can see a very simple cut here from Curry, who is able to shift his opponent’s body weight and run behind the defender towards the basket, where he is picked out with a pass from the inside.

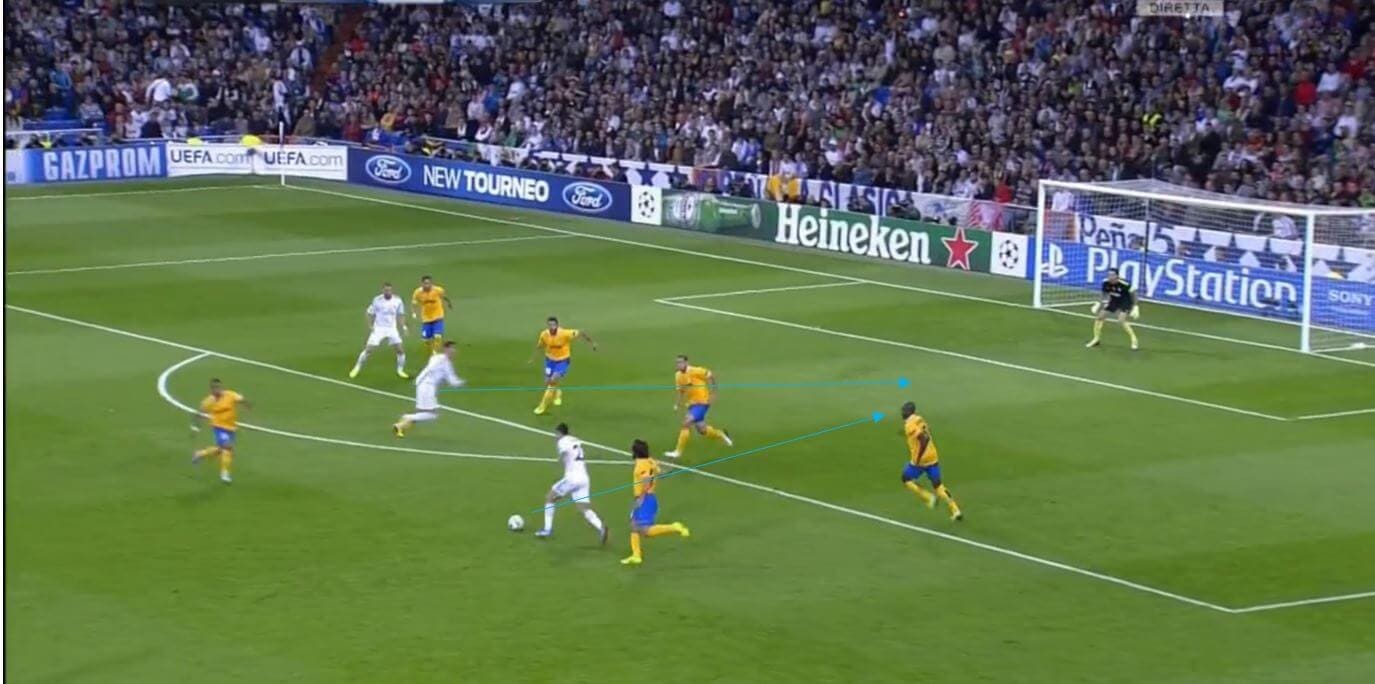

In football, you will see elite level strikers make this kind of movement to unlock defences, with dynamic superiority still a factor. Here, Cristiano Ronaldo moves across and behind the defence to penetrate. Notice how Juventus’ defenders are all still moving forwards. An excellent reverse pass then finds Ronaldo for a goal.

Back cuts can also involve screens to create a free player, with this able to be translated into football through pinning and occupation of players. We can see an example of this here with a back-cut play by the 2013 Miami Heat. The five moves onto the opposition two, setting a screen which allows the Miami two Dwayne Wade to perform a back cut to the basket. The opposition five can’t simply rotate onto the two, as the Miami five is on the basket side of the screen, meaning if left free he has a simple lay-up.

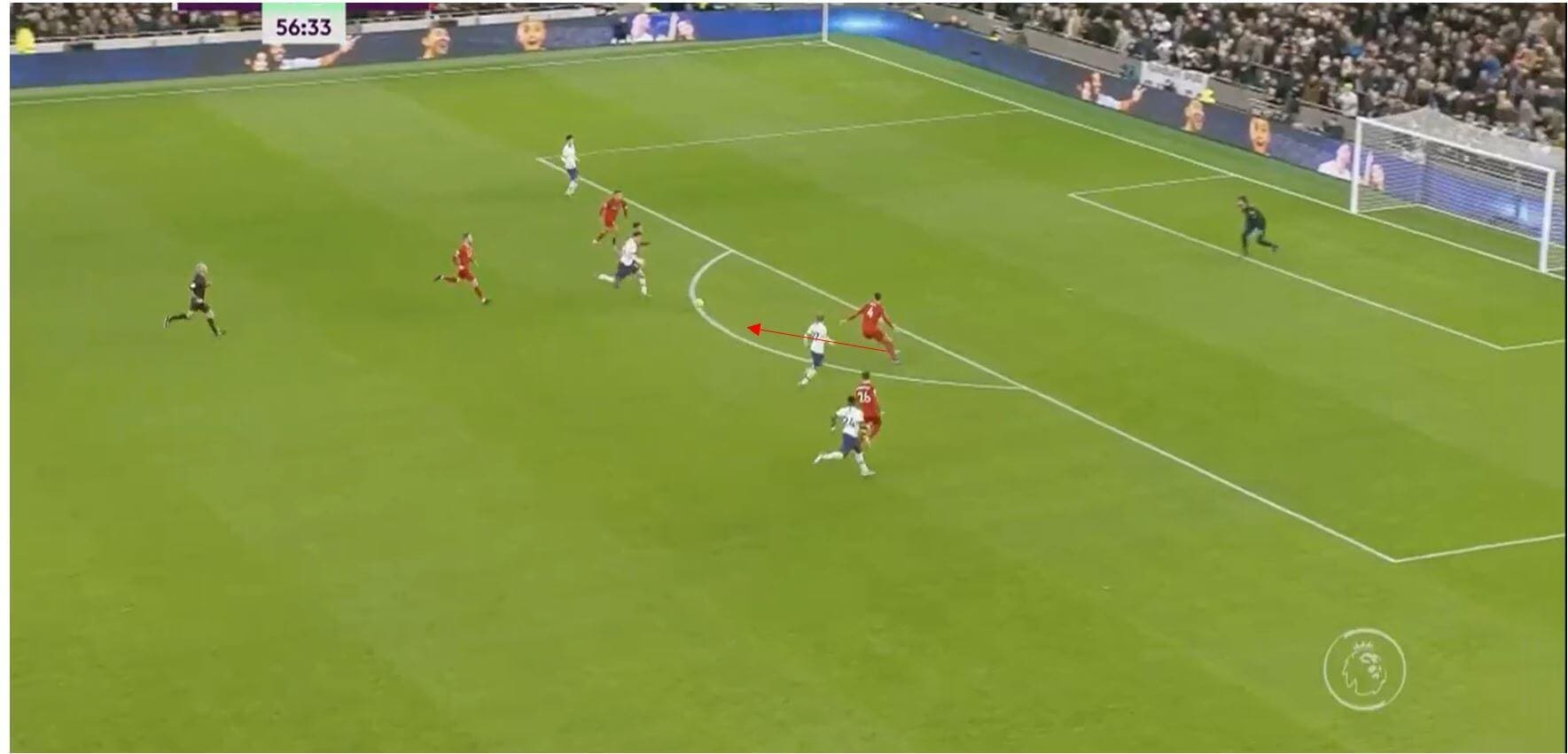

We can use the same principle of occupation to create a cut in football, as we can see here with Heinze’s Vélez Sarsfield. Two players occupy the wing, before one makes a run behind the opposition line to receive a pass. The opposition full-back can’t move in, as they are pinned by the movement of the striker in behind, and the winger can’t tuck in completely either, as another player still occupies the wing. This blind side movement is difficult to defend because you can’t see the opponent behind you, and therefore if they move into different passing lanes, it is difficult to track.

Conclusion

As you can see from this analysis, there are several concepts which can be transferred from basketball and used to improve multiple areas of our game, with this tactical theory article mainly focusing on positional play and build-up. This is really just the start of ideas and concepts which can be translated, and I will certainly be writing more on this subject in the near future, as my notes for this piece haven’t even been half used yet and I have much more learning to do still. Gaining insights from a different sport not only increases our understanding of basketball, but gives us a greater understanding and more well-rounded view of our own sport in time, and hopefully this article has gone some way to starting to do that, or has at least highlighted some ideas or areas of interest.

Comments