Time to come clean.

When the data analysis on defence of underperformers from Europe’s big five leagues was posted back in June, we said the tactical analysis article would follow two weeks later.

Your author got caught up in his work and forgot about the Euros and Copa América.

Without further ado, here is the analysis of underperforming defensive teams. Since their styles vary, we’ve funnelled the approach into more general issues recognized throughout the research games, both over the course of the season and specifically for this article.

There is a surprise progression through the article, one that was initially not considered but certainly recognized as a necessity throughout the research process.

But first up, let’s look at how our focus teams hurt themselves by conceding key spaces.

Conceding key spaces

Let’s start with pure defensive tactics before progressing the analysis to other phases of play.

This is the first and most obvious area to focus on. While defensive transitions and set pieces certainly factor into the equation, there are some clubs whose out-of-possession structures and pressing intensity ultimately hurt their defensive efforts. Generally speaking, when these teams are picked apart during organized, structured play, the tactical issues are too little pressure on the ball, conceding key spaces and a reactive approach as opposed to funnelling teams into pressing areas and traps.

Where clubs decide to funnel opponents and ramp up their pressing intensity is a very specific tactical conversation. We won’t touch on that today, but what we will discuss are the issues that arise from poor defensive structures and a lack of pressure on the ball.

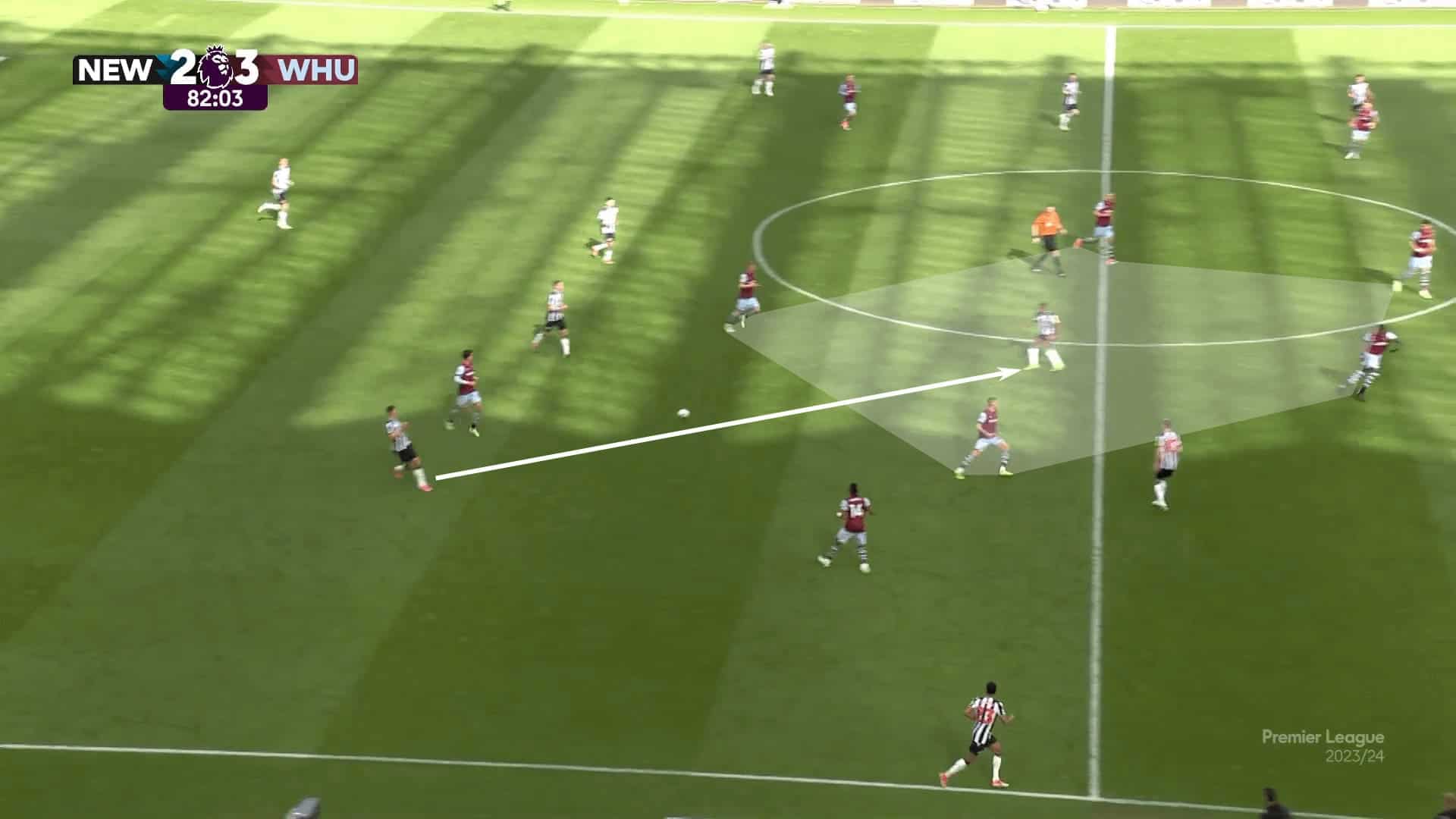

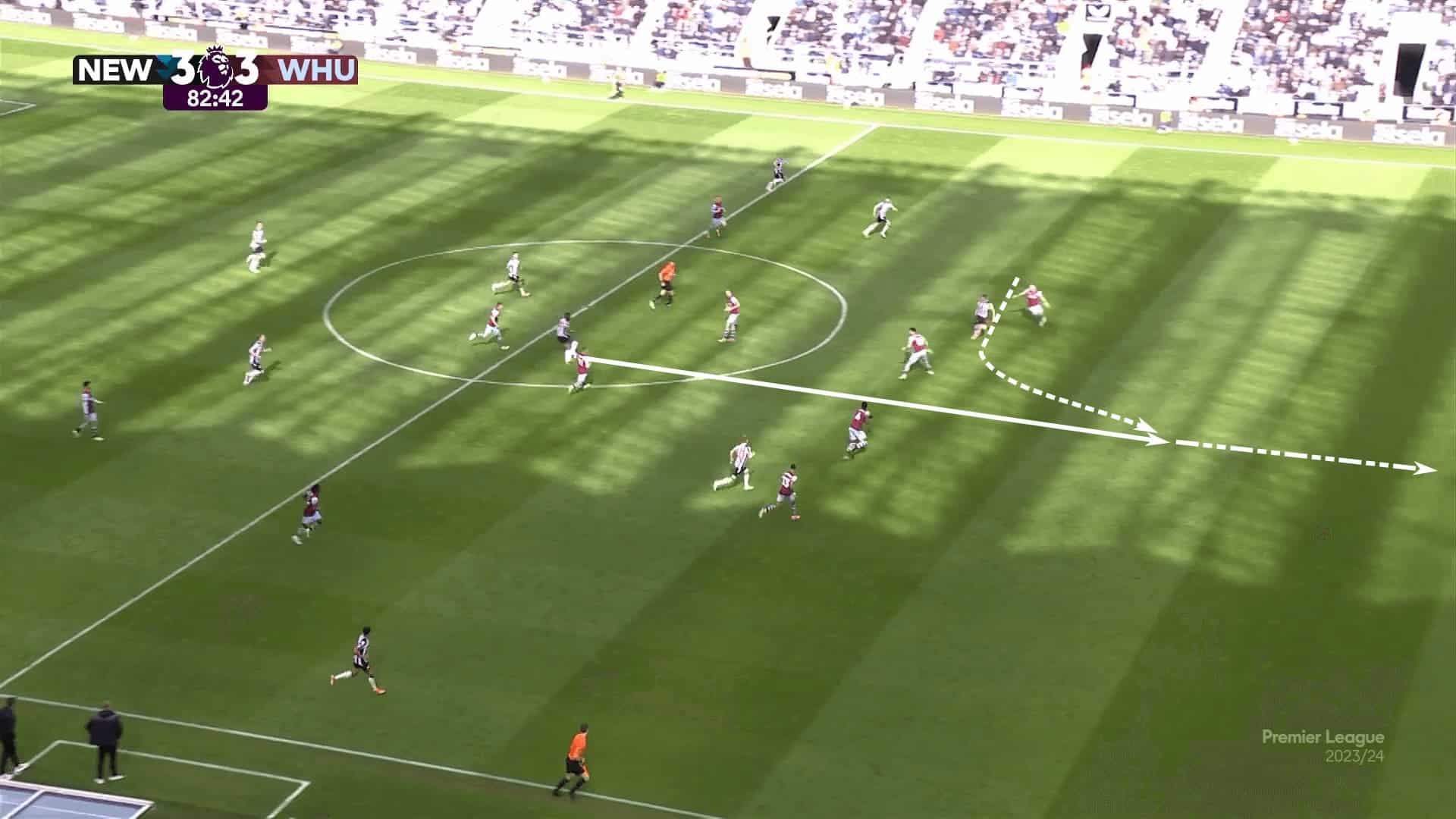

Our first example comes courtesy of West Ham. This image gives a nice overview of a common issue experienced by underperforming defensive sides. As the opponent circulates the ball outside of the defending team’s press, the objectives are typically either to play around the press or find spaces to attack through the press.

This is where West Ham was frequently caught out. The space they consistently gave Newcastle was a gap between the midfield and centrebacks. Not only did Newcastle receive between the lines, but they were able to take the ball on the half-turn and face forward.

In this case, it was Alexander Isak who dropped between the lines. As the Newcastle #9 received, the wingers understood their assignments. With the West Ham outside-backs keeping them onside, horizontal runs gave the wide forwards an opportunity to get behind the centrebacks. It was such a simple sequence—a pass between the lines, a through ball behind the backline and then a Newcastle goal.

It was a similar situation for Borussia Mönchengladbach. They consistently conceded prime real estate to Hoffenheim. In the instance below, they allow a clear passing lane into the #9 and lose track of the #10 in Zone 14. As the #10 drifted off of his defender, he did so in a way that kept him connected to the #9. A clever little flick was all it took to unlock the Mönchengladbach defence and give Hoffenheim a clear look at goal from the top of the box, one that was ultimately pushed wide.

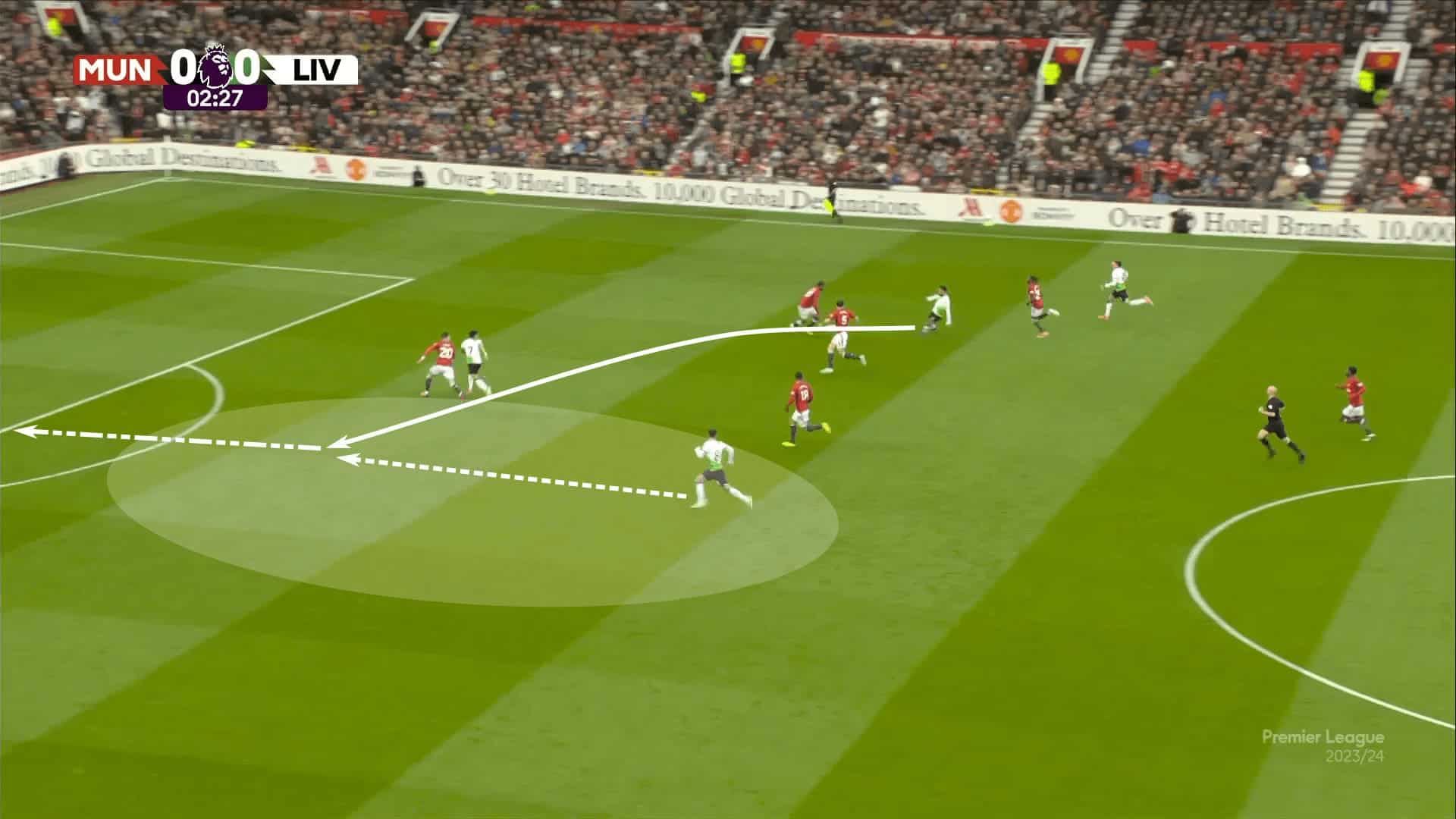

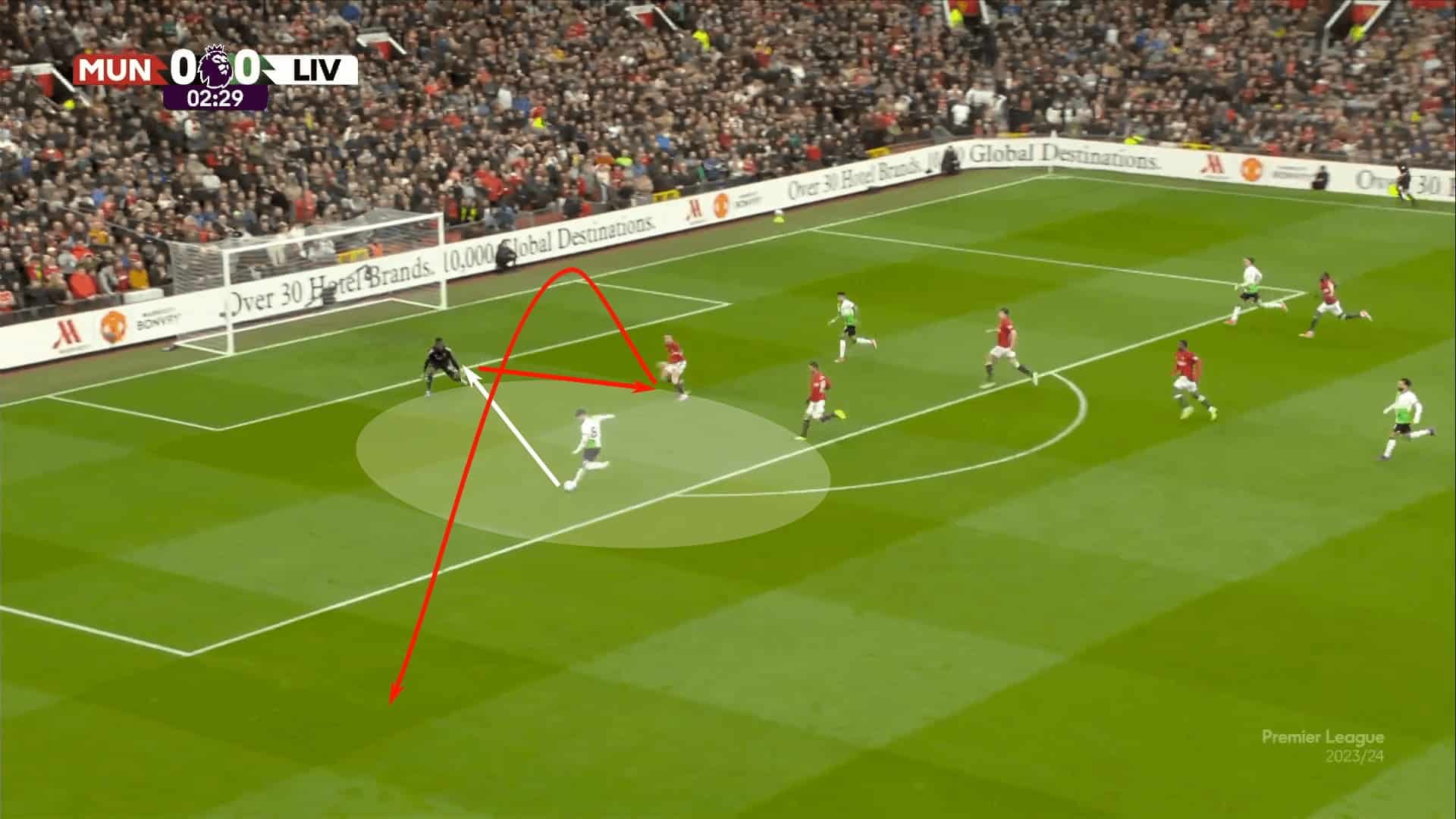

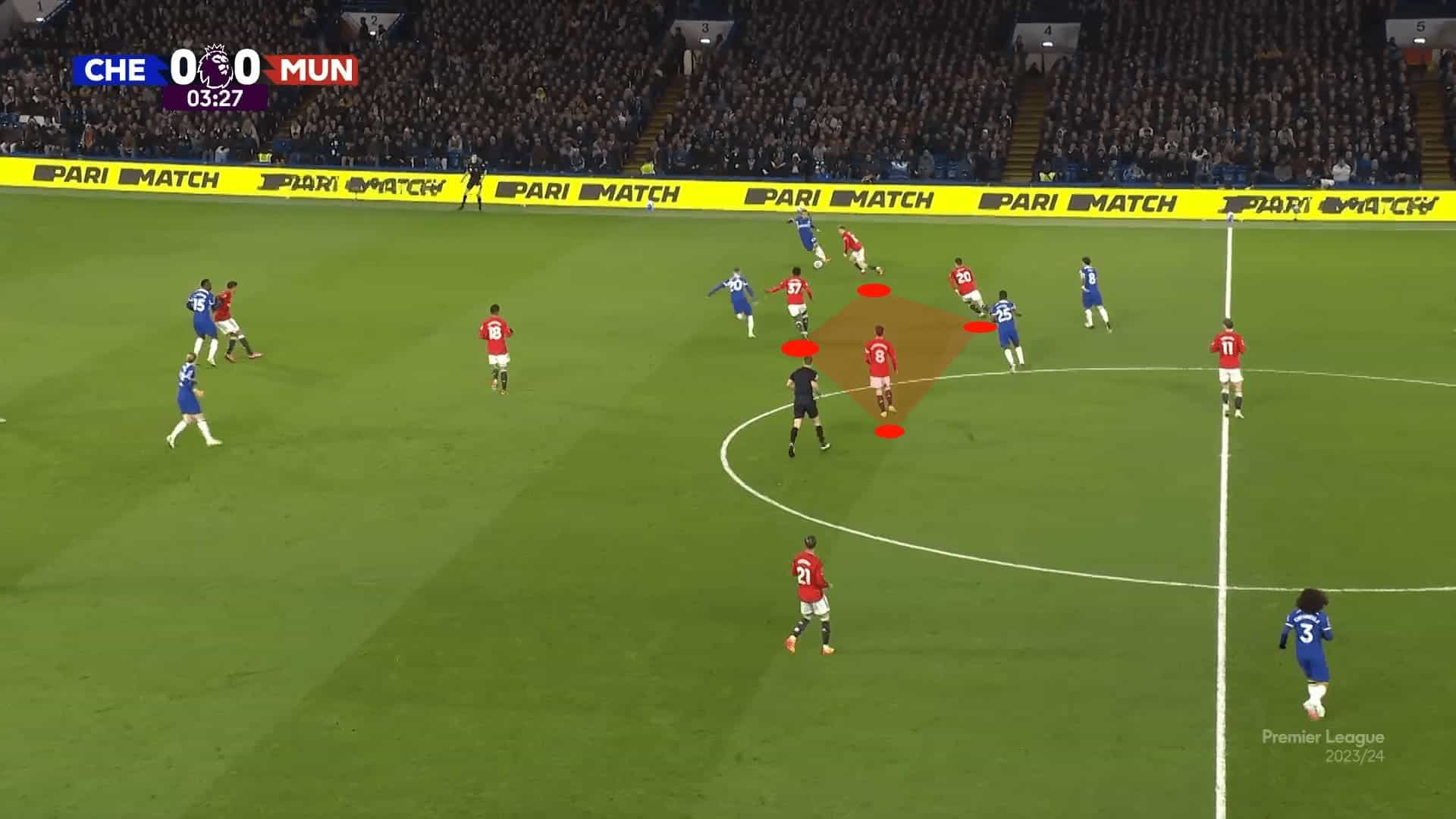

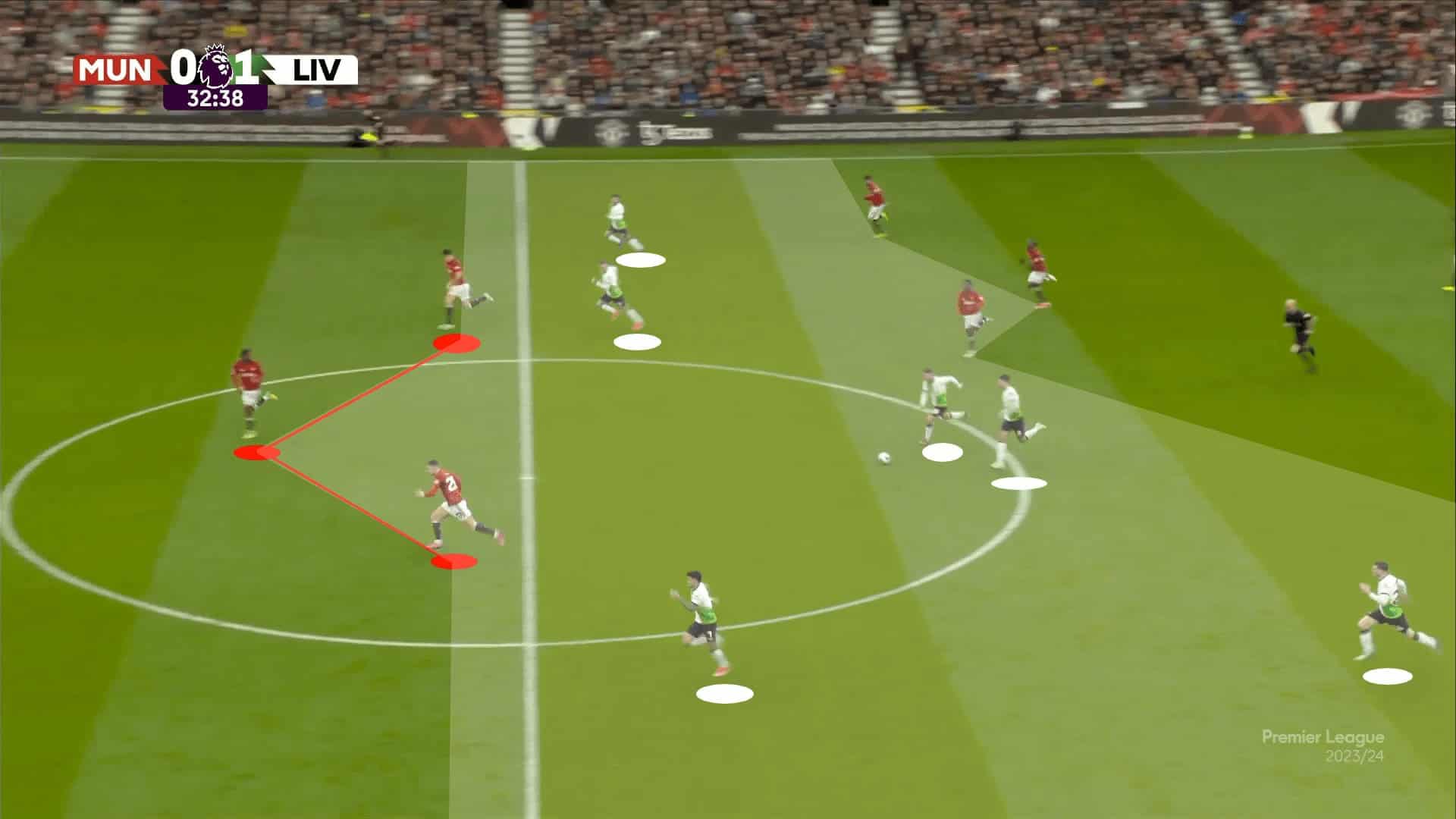

So that was an example of a deep, defensive approach. Now we go to the other end of the spectrum with an aggressive setup from Manchester United. Erik ten Hag’s defensive tactics essentially gave United a one-for-one across the pitch. It’s certainly not a true man-marking system. The team does slide to the left in the example below to compress the field and attempt to seal Liverpool in the wings. That said, they also lack the pressure on the first attacker, which is typical of man-marking.

The issues centre on United being one-for-one at the back, becoming vertically unbalanced and attacking a Liverpool side with the tactical savvy to understand when to play direct. As United pushed up the pitch, Liverpool set the trap, getting numbers forward to play over the press.

Liverpool finds themselves 2v2 along their highest line, with runners coming in support. The United players make an effort to get behind the ball, but this is an instance with the damage has already been done. Luis Díaz’s run from left to right pulls Diogo Dalot away from the central channel. That means Dominik Szoboszlai is in a foot race against Casemiro. This is clearly a favourable position for Liverpool.

A brilliant curling pass finds Szoboszlai, who carries the ball into the box. André Onana made a fantastic 1v1 save to keep this game goalless, but the warning shots were fired. Liverpool would take advantage of Manchester’s poor defensive structure all game, turning this into a foot race and punishing their bitter rivals with one artificial transition after another. These direct possessions all came courtesy of vertically unbalanced pressing structures.

A lack of balance is the key here. For the defence of underperformers, some of the key tendencies in their out-of-possession structures were pushing too many numbers high up the pitch in the high press, losing their structure as the lines shifted in reference to the ball, and the lack of pressure on the first attacker, allowing him to pick out dangerous options higher up the pitch. Whether falling into the attacking team’s traps or simply reacting to their initiatives in possession, the defensive underperformers struggled to control the match through their defensive tactics. As a result, they were left chasing the ball and often the match.

Losing in transition

The impact of transitional moments is an interesting one for our defensive underperformers. Painting with a broad brush, there was a tendency in the games watched for teams to place extra emphasis on their transition tactics, both in attack and defence. Getting forward on the counterattack was undoubtedly a priority, but there was an aspect of reckless abandon as they pushed forward.

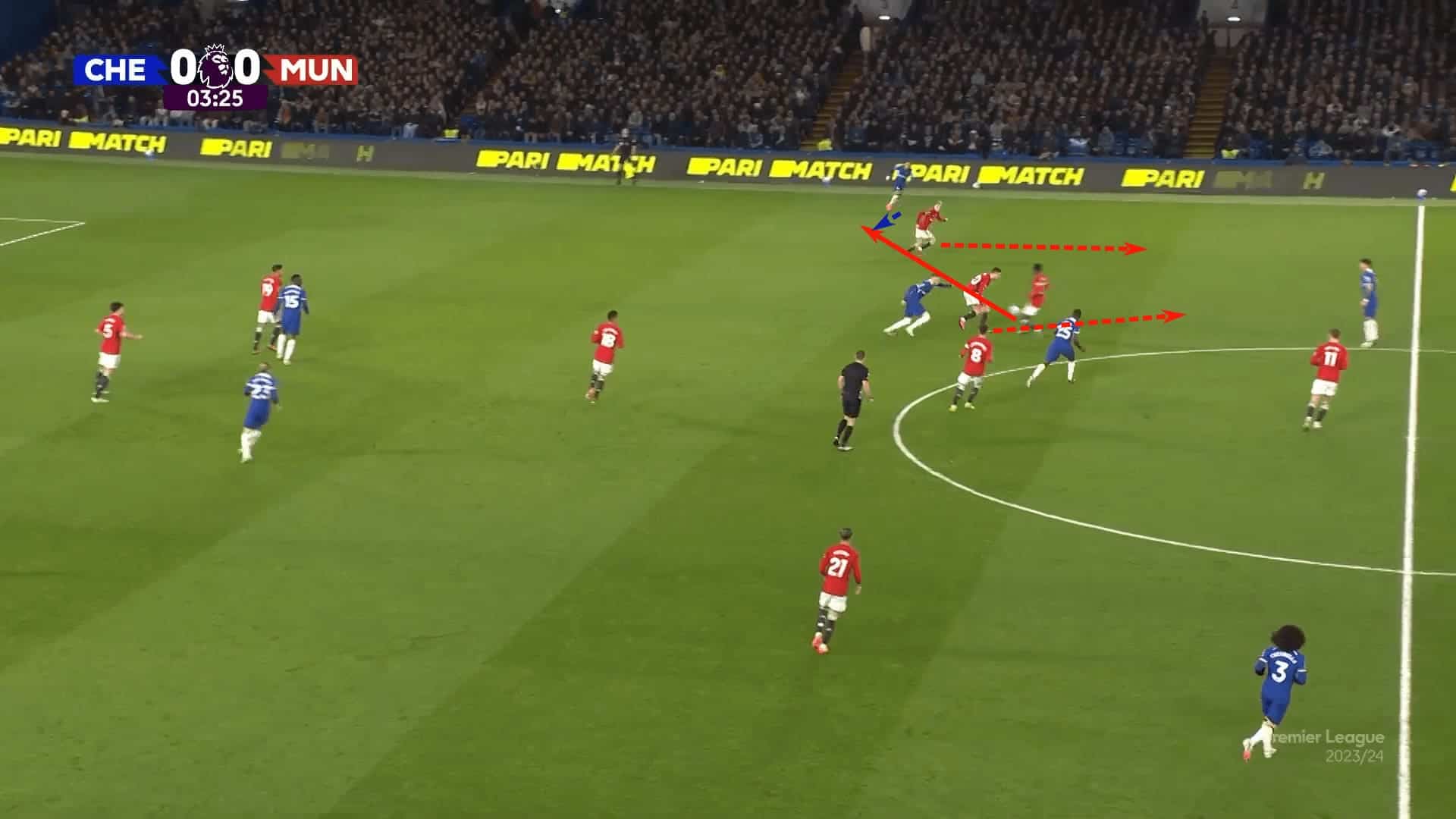

This is where Manchester United consistently found themselves in trouble. Upon recovering the ball, the first instinct was to burst forward. From a tactical perspective, it makes sense to look to play the first pass forward, get between the opposition’s lines and into a forward-facing position. Issues come into play when the first ball can’t go forward, yet nearby players are already off to the races.

That’s what we saw against Chelsea. Once Manchester United recovered the ball, the second attackers were already making an effort to push up the pitch. The problem is that the first pass went backwards on a diagonal, resulting in a turnover.

That means Chelsea, moments after turning the ball over, was now back in possession and had numbers behind the United counterpress.

The Red Devils did fairly well to recover behind the ball, but what they didn’t manage was to eliminate Chelsea’s positional superiority. The London side still had two players behind the United counterpressers. A simple pass beat them and put Chelsea into the final third with space to take.

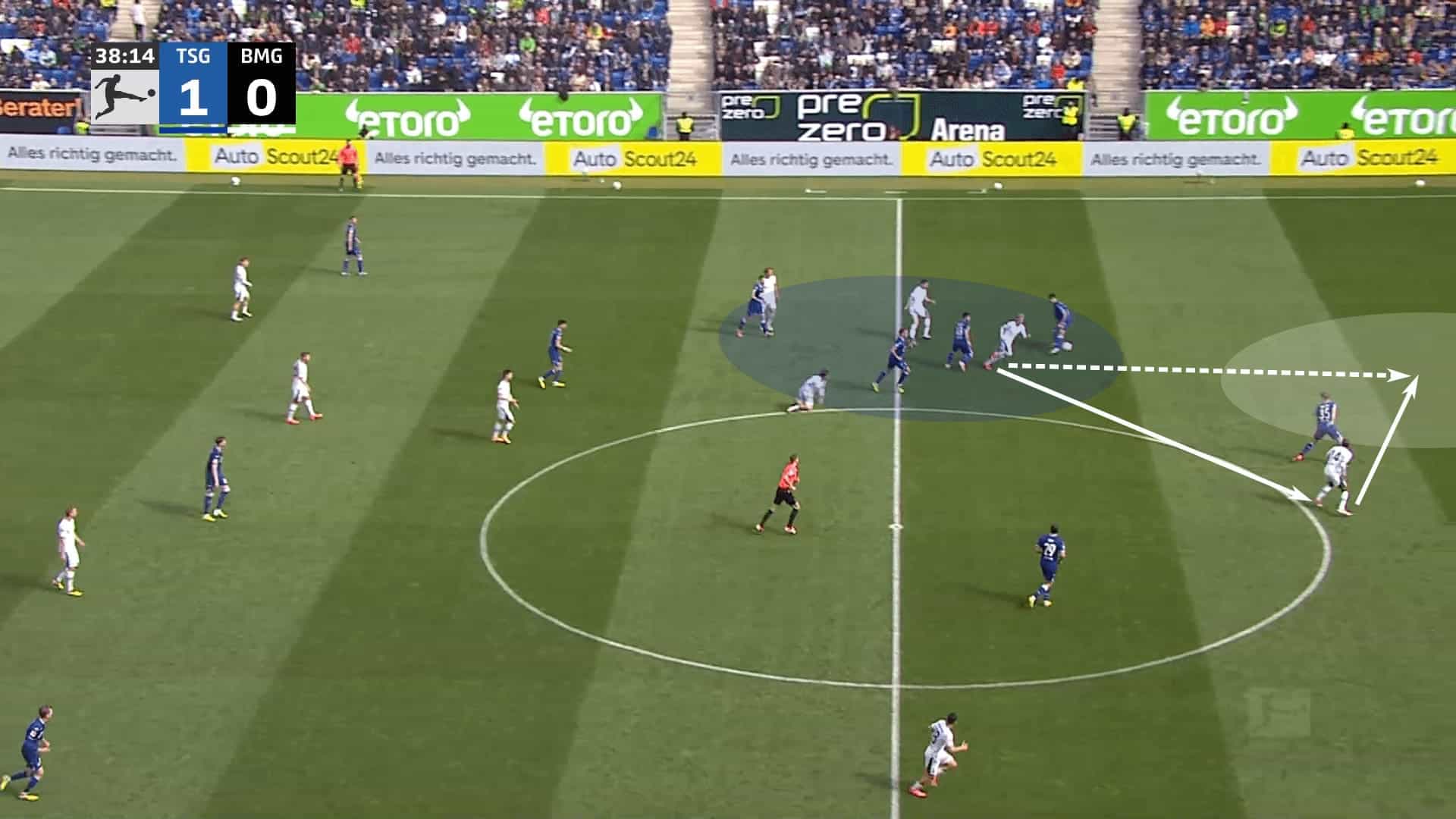

Attacking transitions weren’t the only issue. Defensive tactics played a role as well. Hoffenheim was one of the clubs that made appearances on the underperformance charts. In their match against Borussia Mönchengladbach, their high press was fantastic, forcing hopeful balls forward and leading to middle recoveries. The most challenging moments Hoffenheim faced were largely born out of their unrelenting aggression to recover the ball.

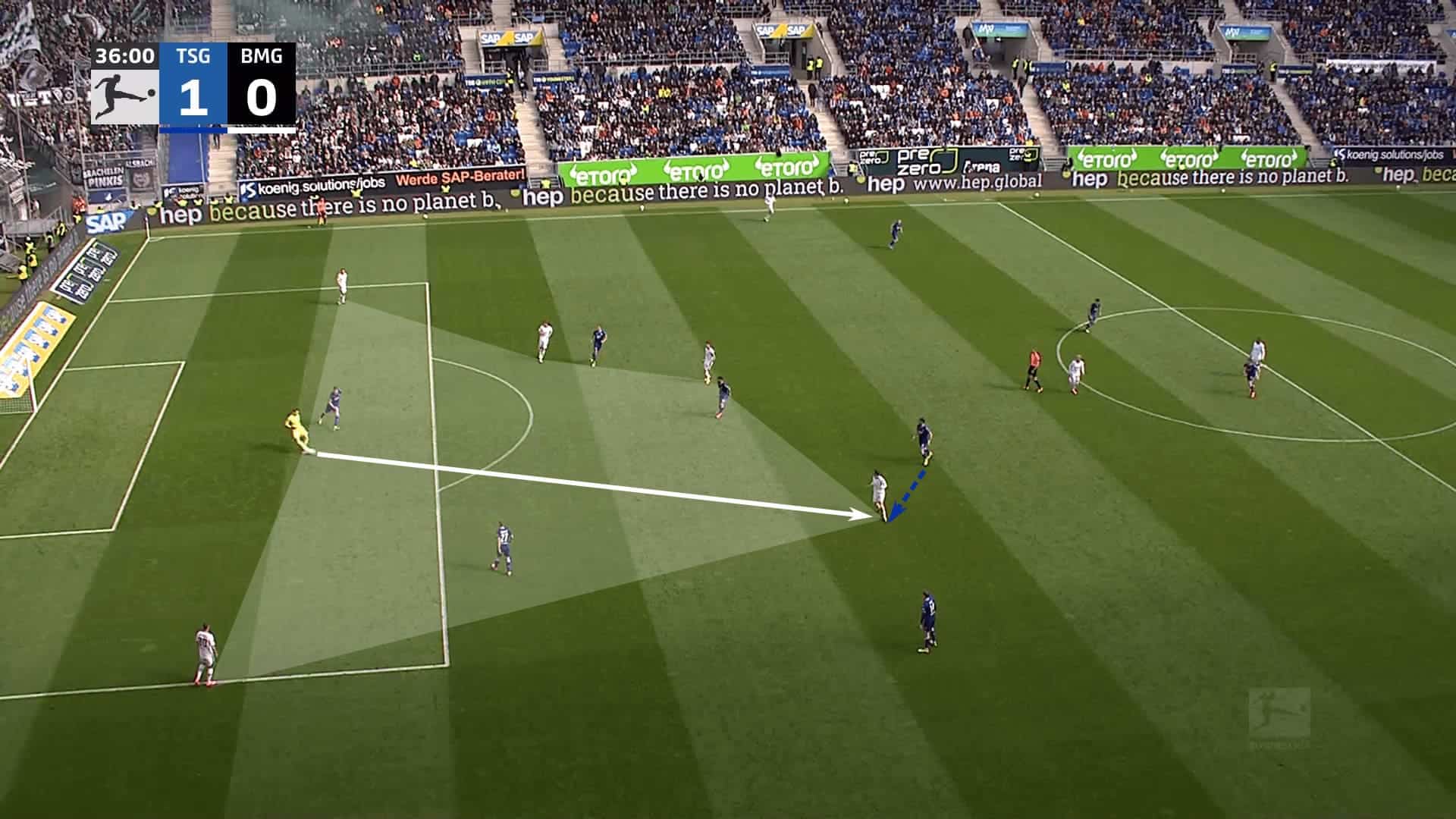

Borussia Mönchengladbach’s first goal came from structural issues that came from an aggressive defensive transition. When Hoffenheim lost the ball at midfield, the nearby players swarmed to the ball. All of them did. The first issue is the space conceded in order to recover the ball. The second issue is that they did not recover the ball despite the numbers committed in the counterpress.

That combination is deadly.

Mönchengladbach played a give-and-go to beat the counterpress and used a 2v1 to attack the Hoffenheim goal. It was BMG’s first real threat, and that moment proved costly for Hoffenheim. As we progress through this tactical analysis, it is those moments, those lapses in concentration, that are the costliest.

In-possession structures and miscues

If you clicked on this article, looking for a masterpiece on defensive tactics, here’s the unexpected twist. Perhaps the greatest influence on a team’s defensive struggles was their attacking tactics.

The game is holistic. Every action is interconnected. When a team attacks, there should be a consideration for how they transition to defence and what a recovery into an organized structure looks like. Likewise, when a team defends, the tactics must connect to principles of transitional play and how they set up their positional attacks once the counter is no longer available.

If there is one common theme for our defensive underperformers, it’s that their attacking principles are incompatible with their defensive transitions. It’s their attacking tactics and rest defence that ultimately causes the greatest defensive strain.

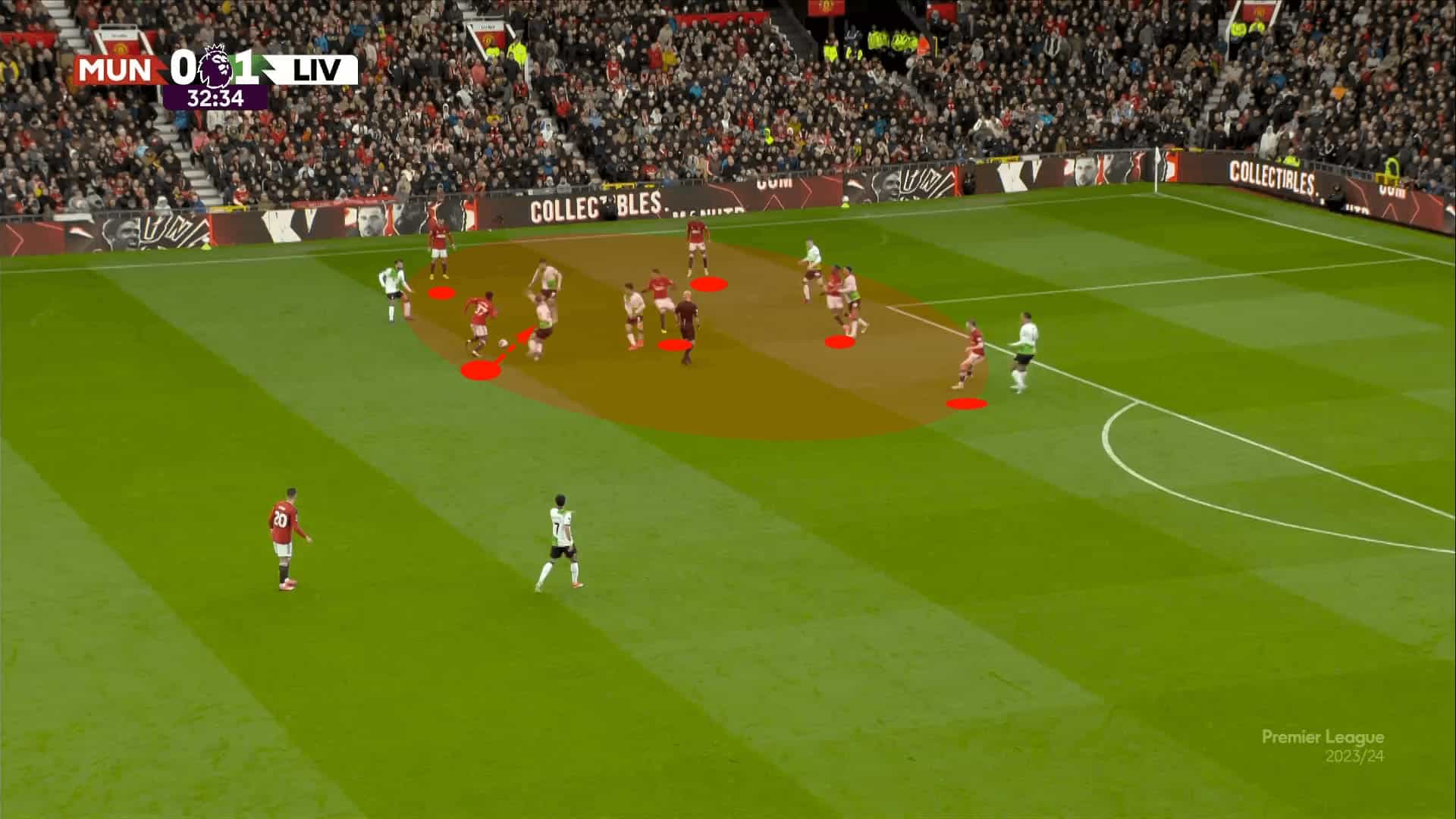

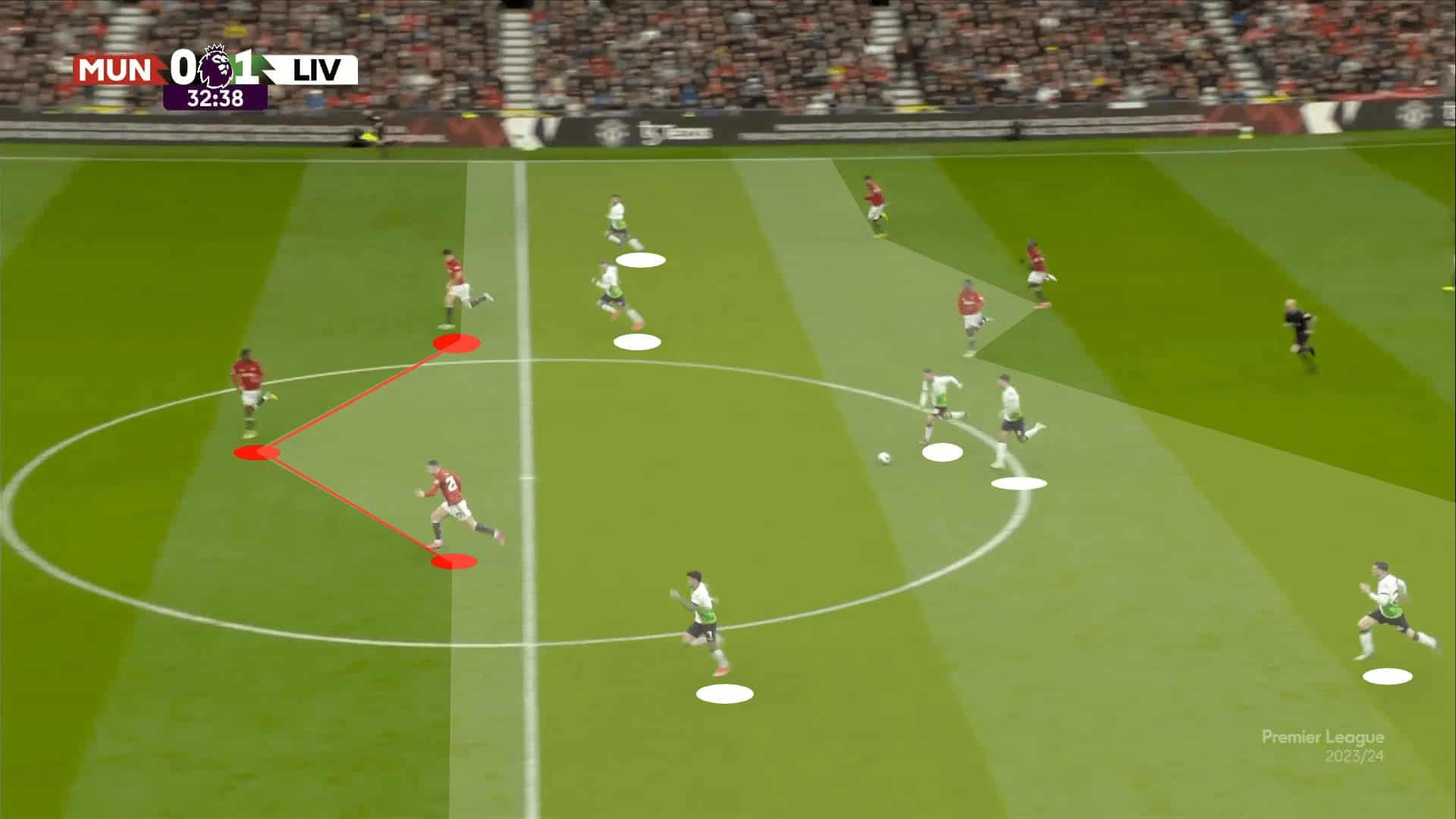

Let’s return to that Manchester United versus Liverpool match. As Manchester United is attacking in the final third, look at their numbers in that shaded area. Six out of the 10 field players are in that small spot; four are left to cover the rest of the pitch.

Their positional distribution is bad enough, but then Kobbie Mainoo decides to dribble right into the heart of the press. The sequence results in a turnover, and Liverpool is off to the races.

Look at the space conceded by the Manchester United attacking structure. They have three players back to contain the Liverpool counterattack. As Liverpool flies forward, they managed to get six players between Manchester United’s midfield and three at the back. It’s a nightmare scenario for a defending team.

Even as United recovers behind the ball they have to respond to the most immediate threats. That requires them to put numbers between the ball and the goal and eventually apply some pressure on the first attacker. As we can see in the picture below, they simply can’t account for every threat. The ball travels to Liverpool’s right and finds the free man. Again, it’s Onana who puts out the fire.

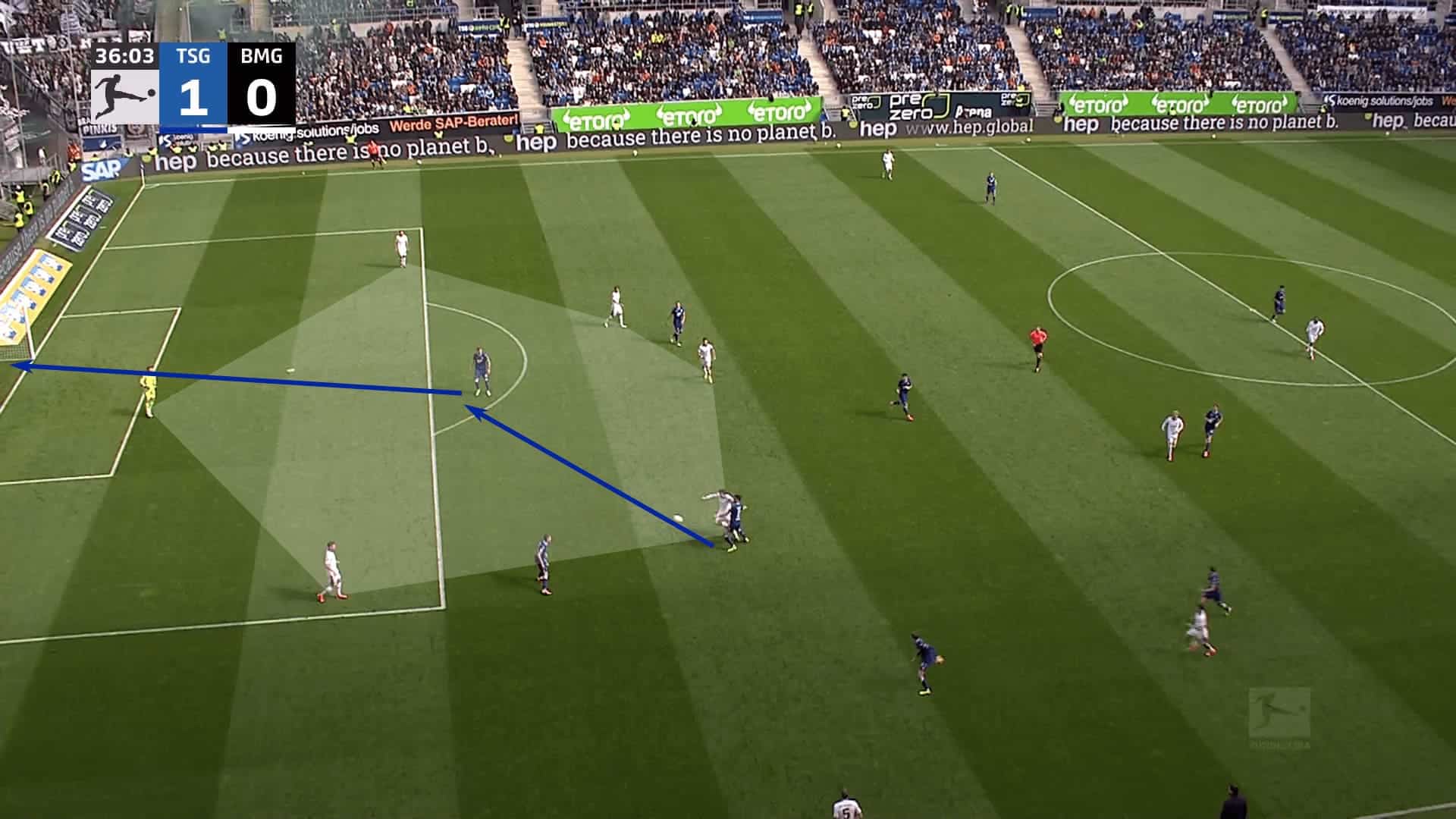

The Borussia Mönchengladbach example is even more egregious. When building out of the back, they push the centrebacks wide to let the goalkeeper control the central channel. He’s the player tasked with progressing the ball from that central area.

The decision-making proves catastrophic. His pass is played to a checking midfielder who receives the ball with his back to goal. Hoffenheim’s high press quickly closes that space and pokes the ball into the path of their #9.

As he receives and finishes, look at the spacing of the Borussia Mönchengladbach players. We’ve mentioned attacking with defending in mind. The only analysis we can offer of this particular sequence is that it’s a build-out that assumes success.

The lack of consideration for in-possession structure and protecting the centre of the pitch was a recurring theme for Borussia Mönchengladbach. Even when in possession, we see that it’s so critical to ask that “what if.” What if the ball is lost? What structure do we need given the way we want to attack? Where are we most likely to assume risk and how do we counter that with our positional structure?

These are the questions that cannot be disassociated from in-possession tactics. The way a team attacks necessarily relates to the way they defend.

We have examples from Manchester United in the final third and Borussia Mönchengladbach in their defensive third. Let’s turn our attention to the middle third for a final example. This is a more subtle topic, but certainly one that is worth exploring.

This Crystal Palace goal is worth watching, but we’ll give a four-in-one image to show how the sequence unravelled. As West Ham possessed on their left, there was a positive initiative to unbalance the Palace defence and switch the point of attack. West Ham got the ball into the centre successfully, but that’s when their problem started.

Their attacking tempo slowed, allowing Crystal Palace to poke the ball away. With a first pass forward, Palace found a free man between the lines, played the next pass behind the West Ham backline, and then squared the ball across the box for a routine finish.

Let’s dig deeper into the analysis. When a team switches the point of attack, the objective is to attack unoccupied space. The opposition has limited numbers on that side of the pitch, but ultimately, so does the attacking team.

One way or the other, the team in possession has few obstacles in their path. If the team that switched the point of attack loses the ball, as West Ham did here, they concede a significant positional superiority to the opponents. That immediately triggers recovery and emergency defending. In one moment, West Ham moved from quickly advancing up the pitch to now desperately acting to put out fires. In this example, the task was too big.

Conclusion

We’ve covered all 3/3 of the pitch. In terms of general principles that led to high-risk situations, we can point to structural issues in each attacking subphase. Playing from the back, there’s a lack of central presence to protect against the turnover. In the middle third, the miscue turned an advantage into a disadvantage. In the final third, becoming unbalanced on the vertical axis, and in the Manchester United example, near the ball, the players outside of the overload simply have too much space to cover.

Casemiro took a lot of flak for his lack of mobility last season, but asking a player with his skill set to routinely engage in foot races is the real culprit. The same goes for Sergio Busquets’ final years at Barcelona. He was often the scapegoat for Barcelona’s defensive vulnerabilities. His direct opponents having success wasn’t the cause of the issues, merely the symptom. Ultimately, Barcelona’s attacking structure left him unsupported and with too great a task.

When rest defence is poor, individuals are overwhelmed by the responsibility of covering responsibilities and spaces that are better suited for multiple players.

If there’s one lesson to take from this tactical theory article, it’s that a team’s attacking and defensive tactics must complement each other. A holistic approach that pieces together the phases of play within a cohesive game model is the recipe for success.

At the very least, it offers a path for staying out of the running for underperformer accolades.

Comments