In the 46th Total Football Analysis Magazine, dated November 5th 2020, we ran a data analysis piece entitled, “The Art of Overachieving.” Analysing the impact of wage bills and transfer spending, top overperforming teams were identified and their recruitment and tactical philosophies studied.

With a massive database on hand, it seemed natural to find teams on the other end of the spectrum, the underachievers. Who are they, how did they perform and why were they unable to hit an appropriate mark relative to their financial strength?

To answer these questions, this data analysis takes a looks at the underachieving teams in the global game. As with the overachiever article, this piece uses the financial statistics from Global Sports Salaries and Transfermarkt, as well as performance data from Wyscout. The goals of this analysis are to use club wages bill to identify the supposed powers, examine what poor transfer spending looks like and hone in on existing models and influences in underachievement.

Performance and financial data from the top five UEFA leagues are applied in this analysis and the data sourced ranges from the 2013-14 season to 2019-20 campaign. Dates listed next to each team represents the ending year of the campaign, so “Milan 2018” corresponds to the AC Milan 2017-18 team. Each comparison in the data analysis uses uniform measures from across the top five leagues, ensuring the integrity of the data.

Team salary

From “The Art of Overachieving” article, we know that a club’s wage bill is the best indicator of expected success. Each league’s powerhouses might vary greatly in transfer spending from one window to the next, but they’ll always pay top players top wages. It’s a constant in the analysis.

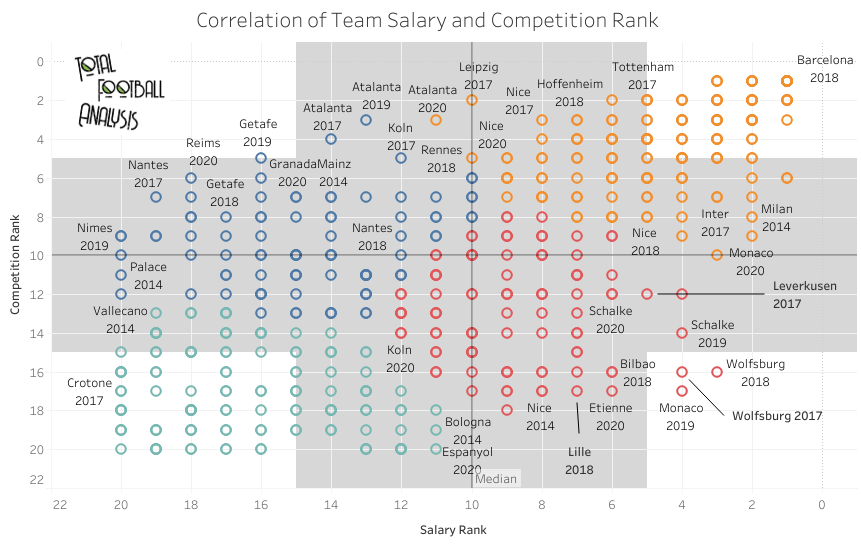

You’ll recall the graph showing the correlation between team salary and competition rank. As the club’s wage bill becomes more robust, so will their competition rank, at least in a general sense.

Above, we find the 2016/17 and 2017/18 Wolfsburg sides rate 4th and 3rd in Bundesliga salary rank for their respective seasons, but the club was barely able to stave off relegation, surviving via a playoff with the 3rd place Bundesliga 2 team.

That 2018/19 Monaco team is one to remember. You’ll recall the summer transfer window of 2017 that saw the club lose Kylian Mbappe, Bernardo Silva, Benjamin Mendy, Tiémoué Bakayoko and Rúben Vinagre. They followed up that window by losing Fabinho, Youri Tielemans, João Moutinho and Thomas Lemar the next summer. Nearly an entire starting XI, and a world-class one at that, left the club within a 15 month window. Despite the reinvestment in the transfer window and high wage bill, that 2018/19 drop off isn’t surprising.

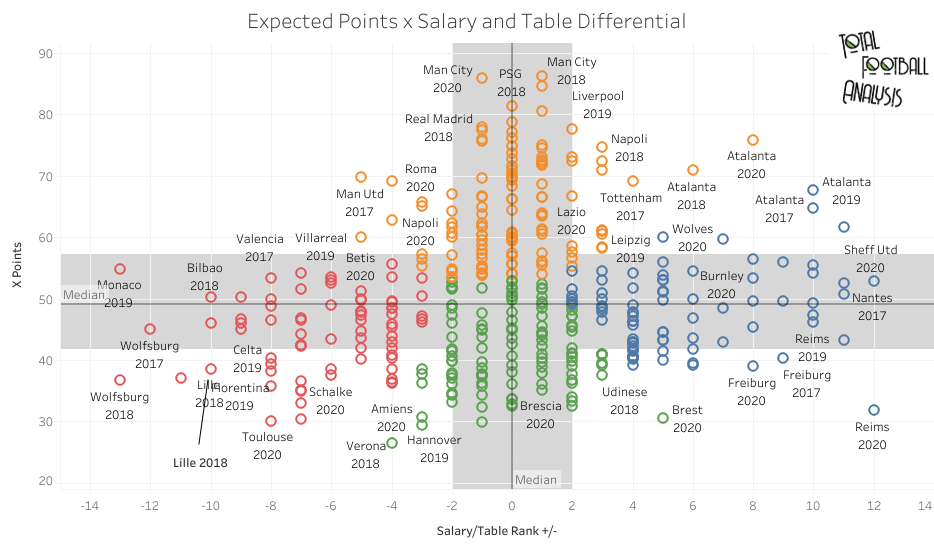

Part of their struggles simply came down to bad luck under Leonardo Jardim and Thierry Henry. Looking at the expected points total from the 2018/19 season, Monaco should have garnered far more than the 36 points they managed that season. Their xPoints for the season came in at a healthy 54.9, good enough for 8th in Ligue 1.

The image above also bears a repeat listing for Wolfsburg’s 2016/17 and 2017/18 sides. Finishing 12 and 13 spots, respectively, behind their salary rank, those teams also managed meagre xPoints totals. 45.1 xPoints in 2016/17 was 10th in the Bundesliga, but the 36.7 the following year rated 17th in an 18 team league, indicating that Wolfsburg was luck not to be relegated.

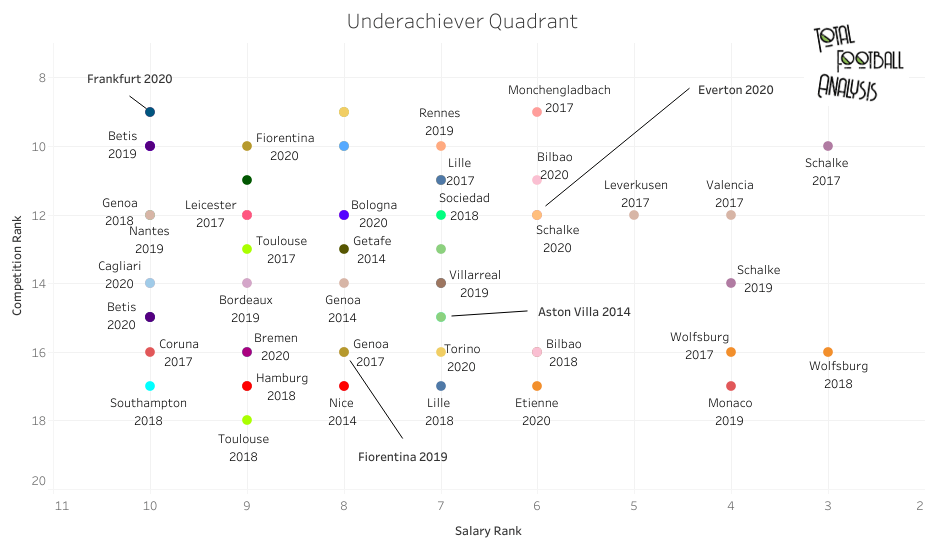

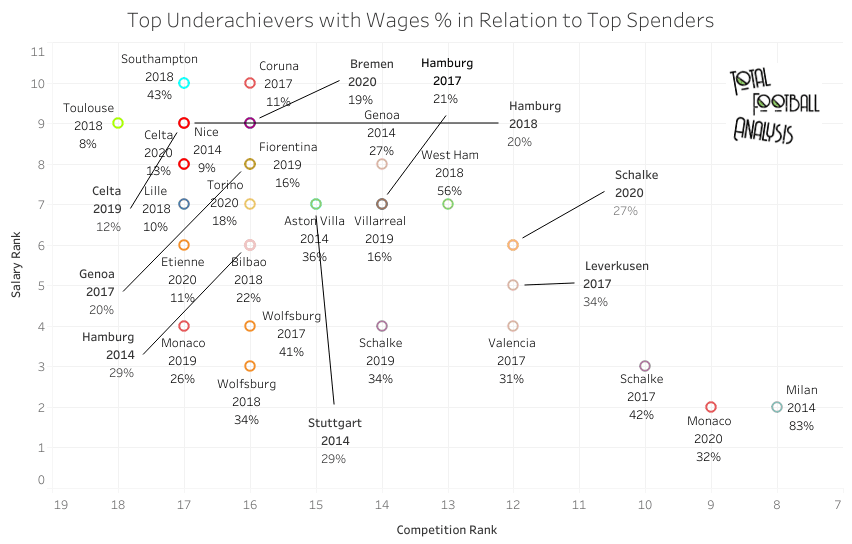

Looking specifically at the underachiever quadrant, the image below filters for clubs that rated in the top half of their league in salary rank, yet finished in the bottom half of the table.

Within the dataset, these teams have produced the greatest feats of underachievement. Wolfsburg and Monaco claim their spots on the one extreme, but there are a number of surprising, very competent clubs to suffer a terrible season or two. Lille, Real Betis and Schalke are all solid mid-tier clubs that fell on difficult times.

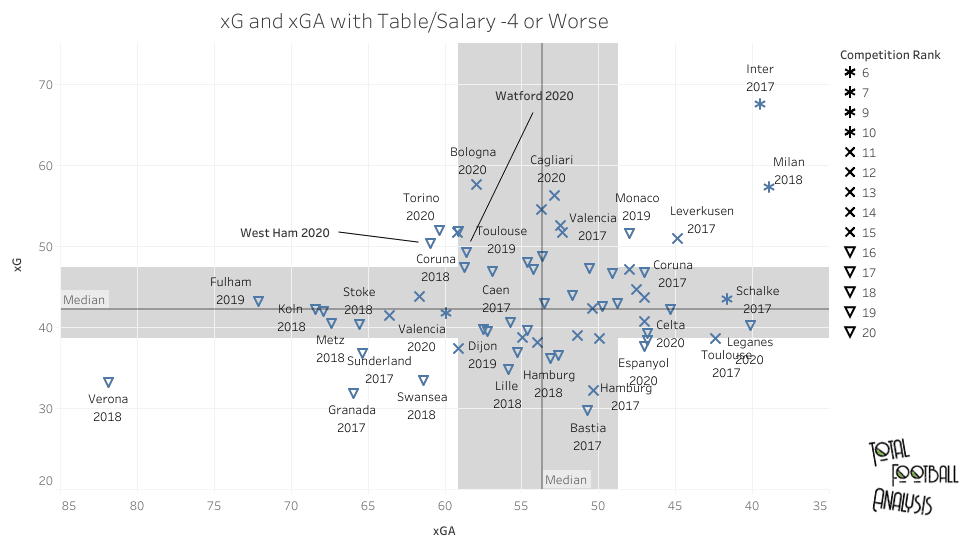

Reframing our view on the top underperformers, the image below examines xG and xGA among teams that finished at least four spots lower on the league table than they did in the league’s salary rank.

Across Europe’s top five leagues, the average xG and xGA per team is 49.4 per season since the 2016/17 season. For a club to find themselves in the lower-left quadrant in the above image, rest assured they had a season so awful, it was almost spectacularly bad.

Even among the sides in the top right quadrant, only the 2016/17 Inter Milan team stands out as a shock underperformer, rating highly in both xG and xGA. While the 2017/18 AC Milan was strong defensively, their expected goals tally is only slightly above average, which simply isn’t good enough given the massive amount of money pumped into the roster that year. Interestingly, that’s also the region we find that 2018/19 Monaco team.

To give a better idea of season expectations and the relative spending power of the elites, the next graph considers salary and table ranks but also lists the percentage spent on player wages relative to the top spender in their respective league.

For many of our underachievers, we find that the failure is not relative to the teams with the highest wages bills, but performance among their financial peers. The one exception in the chart is the 2013/14 AC Milan team, which had the 2nd highest wage bill in Serie A, spending 83% of Juventus’ total.

For sides like Deportivo de La Coruña, Nice and Toulouse, spending roughly 10% of a PSG or Barcelona still keeps your club among the league’s top 10 wage spenders, so the underperformance is relative to the bottom half of the table.

But what about the wealthiest clubs? What does underachievement look like for them?

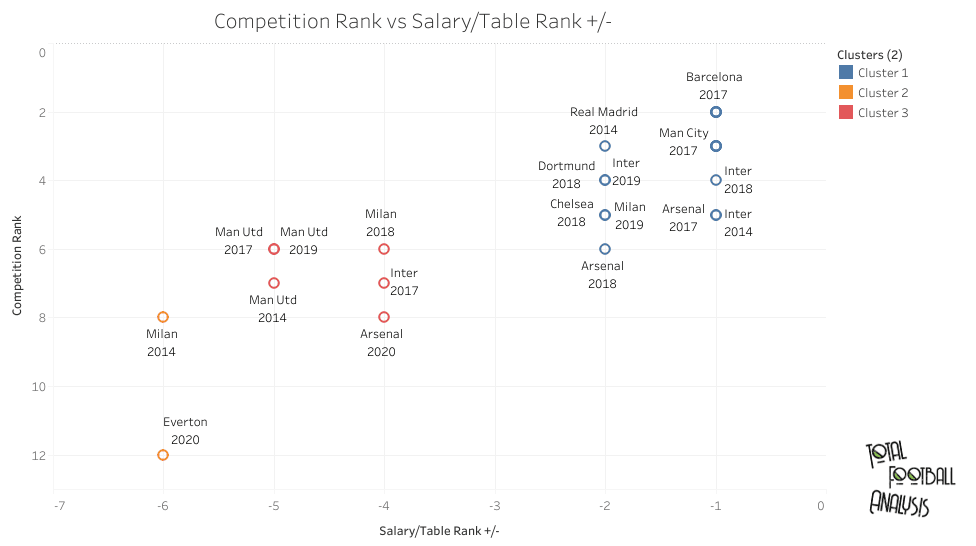

Filtering for the teams with the highest wage bills, we can then examine our top underachievement candidates relative to their league rank and the biggest discrepancies between salary and table rank.

In the top right corner, we have the narrow underachievers in blue. They’ve missed the mark, but not by much, at least not relative to their wages. In red, we have teams that significantly underperformed. Finally, at the bottom left of the image, roughly the worst seasons from top spending clubs. It might surprise some to find 2019/20 Everton in that lowest position, but a large investment from the club placed them sixth in the EPL’s wage bill table.

Worse than the one-shot wonder is the repeat on the list, a real glutton for punishment. To find three Manchester United squads in the red cluster is an indictment on their performance relative to their spending. Sir Alex’s departure certainly takes a toll, but the money spent on wages and transfers ought to produce better results.

Though Arsenal makes the chart three times, two are in the blue cluster. However, the 2019/20 season, which saw the club drop Unai Emery for Mikel Arteta and bring in a number of young reinforcements, rates among the worst performances from the dataset.

Looking at some of the most frequent clubs to appear in this section, we can track their spending, table and salary rank and expected performance statistics.

Interestingly enough, while underperformance can plague a club for a number of seasons, the stats in the image above give the impression that extreme underperformances are fairly easy to correct within a year or two. As we’ll see later in this analysis, there’s usually a shock to the system that leads to aggressive underperforming.

Transfer market spending

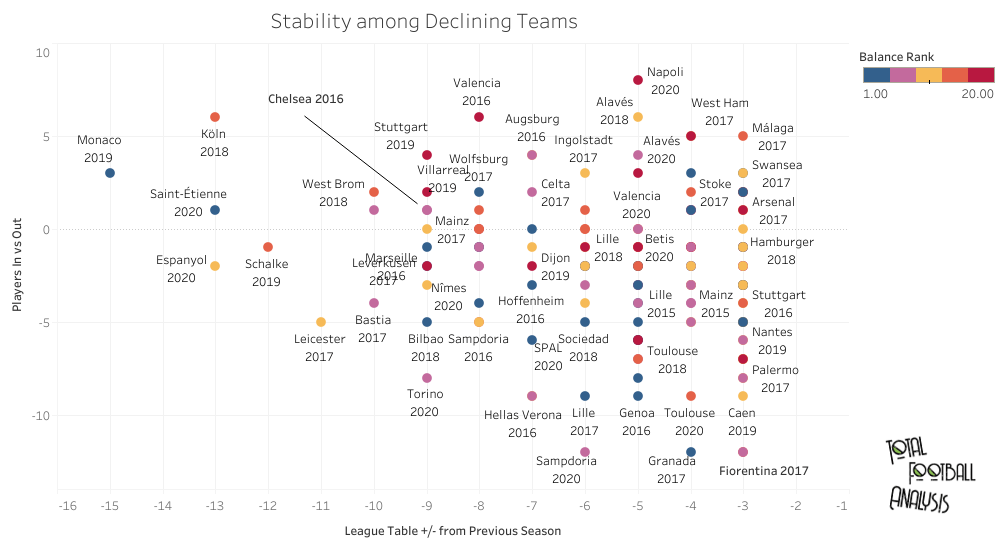

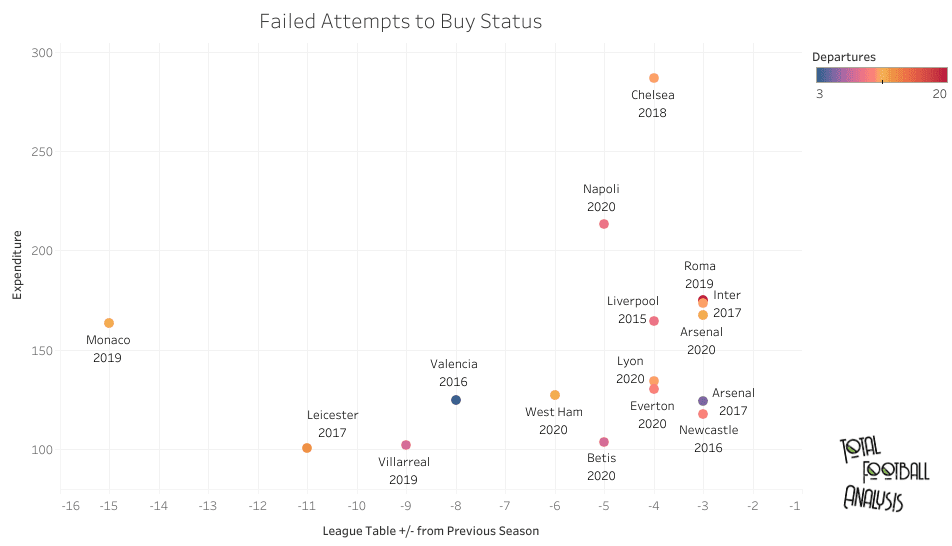

In the graph below, we’re looking at the stability rating of teams that dropped at least three spots in the league table from the previous season. Keep in mind that few of Europe’s elites will fall into this graph. Three spots is a significant drop for top teams, but it’s far more likely from the middle tier clubs.

With the exception of the 2015/16 Chelsea and 2016/17 Arsenal teams, we find that it’s generally more established, mid-tier clubs that make the list. A period of success followed by a spell of underperformance is likely influenced by competing in Europe or the loss of key players. On that second point, as mid-tier clubs ride the backs of top, emerging players to new heights in the table, Europe’s elite wait in the wings to sign the player. It’s no coincidence that Wolfsburg’s struggles also correspond with the loss of a certain Kevin de Bruyne.

To that point, Espanyol’s 2019/20 team was a Europa League qualifier the season beforehand. While struggling to compete in two competitions, their La Liga form slide and the coach’s seat was hot all season. Four managers stood at the helm, but none were able to correct the course.

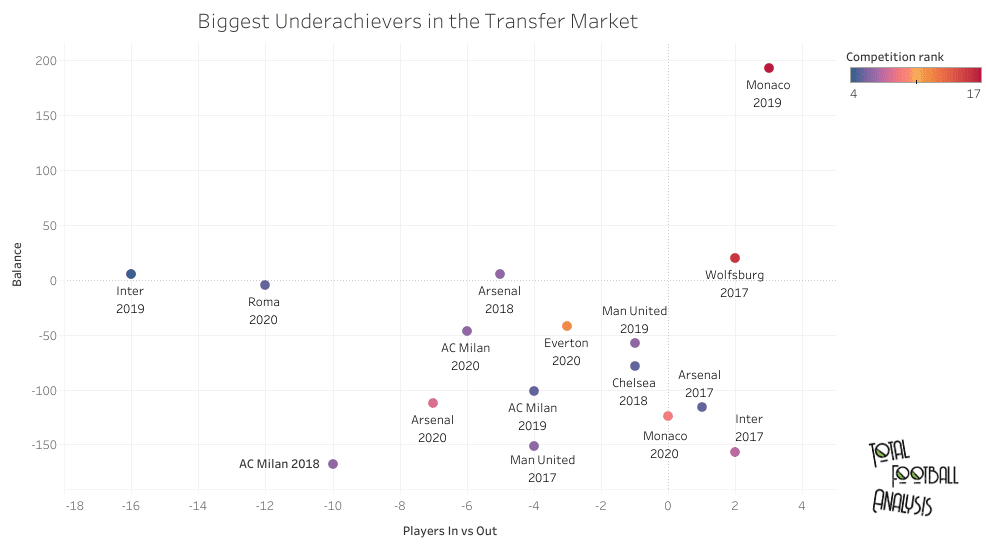

Among the underachieving teams with high wage bills, we find that it wasn’t down to a lack of investment. Of the 16 points in the plot below, only five rate at or above a zero balance.

We find that most teams not only spent money, typically large sums, but they also finished the season with more players departing than joining the squad. The general pattern is offloading first-team excess and academy products to funnel funds into top-shelf talent.

For clubs at the lower financial end of this tier, such as Wolfsburg and Monaco, you might see fewer top-level talents enter the club, but a number of high-upside players come in, offering lineup depth, the hope of next-level talent and the prospect of a large outgoing transfer fee. This recruitment philosophy is sometimes called “the shotgun approach”, prioritising high-ceiling low-floor players instead of top-end quality. When you’re right, much like Monaco was in 2016/17, winning Ligue 1 and reaching the UEFA Champions League semifinal, the result resembles a video game save more so than reality.

That said, it really is difficult to buy your way out of trouble. There are simply too many variables to consider, especially if the core of the team is gutted. Player quality fluctuates, the established playing style might not fit the incoming players, team cohesion needs time to develop and maintaining the psychological state of individuals, especially higher-priced new players, can present difficulties.

Filtering for teams that spent a minimum of $100 million in a transfer market, all in a single season, we can see that clubs can’t necessarily buy their way to a higher domestic status.

Casting transfer expenditure against league table movement from the previous season, the image above identifies clubs that spent big yet still dropped at least three spots in the league table. With some sides, like the 2016/17 Leicester team, the massive drop is indicative of wild overachievement one season, followed by a regression to the mean the next. Fitting the UEFA Champions League fixtures into their schedule simply didn’t help matters either.

On a positive, there is a sense that a large transfer expenditure should, in theory, lay the foundation for future success. So long as consecutive seasons of underachievement doesn’t happen, a club can maintain hope that they’ve done good business in the transfer market.

So, no, clubs can’t spend their way to improved domestic standing, that short-term underachievement can play a role in long-term success, especially for clubs with a wage bill less than 75% of the league’s top dog.

Where did they go wrong?

In the salaries section, we highlighted five clubs that had numerous seasons of underachievement. Much like The Art of Overachieving article, this one will briefly address some of the underlying contributors to lacklustre performances relative to wages. The first of which is recruitment philosophies.

Recruitment philosophies

As mentioned earlier, some clubs have a “shotgun approach” to signing players. At times, this is by necessity, especially from clubs that sit just outside of Europe’s financial elites. Other times, a new owner looking to make a splash or a perceived need to reload the roster serve as the impetus for large-scale transfer spending. AC Milan and Monaco fall into this category.

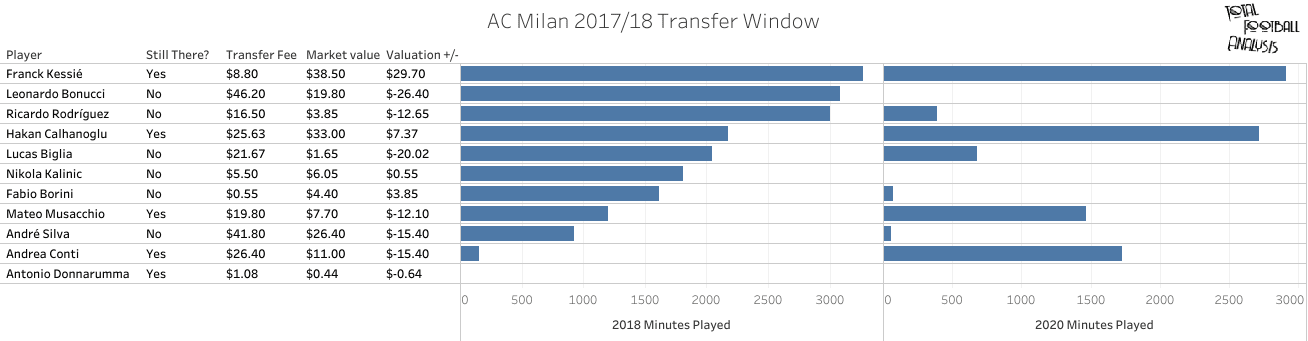

To visualise the point, have a look at AC Milan’s transfer spending in the summer of 2017. Many expected them to contest, if not overcome, Juventus’ reign at the top of the Serie A table. The backline received an instant upgrade, especially with the signing of Leonardo Bonucci from Juventus. Franck Kessié and Hakan Calhanoglu represented improvements in midfield, while André Silva, coming off an extraordinary season with Porto, was tabbed to lead the line up top.

Below we see the big summer signings, the financial data points and minutes played in the 2017/18 and 2019/20 seasons.

While eight of the signings registered more than 100 minutes, Silva never settled in, Bonucci returned to Juventus after one season and six of the 11 signings are no longer with the club. Of those remaining, Kessié and Calhanoglu have stepped into major roles, Andrea Conti is emerging as a regular starter and Mateo Musacchio is still contributing.

Lots of players arrived, a massive sum was spent to bring them in and Milan are yet to return to the UEFA Champions League for the first time since the 2013/14 season. While the 2017/18 signings registered a total of 37,494 minutes in 2017/18, that number has dropped to 21,313 in 2019/20, a 43% decline. Additionally, since signing with AC Milan a few summers ago, that group has lost a total player valuation of $61 million. A few great players have panned out, but, on the whole, wasteful spending plagued AC Milan.

Inability to balance European and domestic play

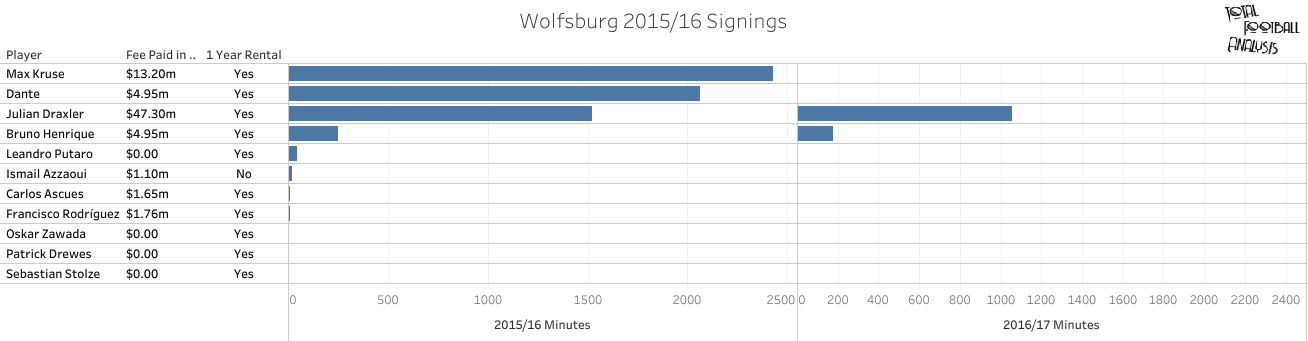

Turning our attention to Wolfsburg, we find a club that spent money on wages, keeping key contributors at the club, but also a measured approach to transfer spending. Losing KDB to Manchester City certainly hurt their prospects of a successful UCL run, but it was the lack of depth at the club that hampered their ability to cope with another competition.

With Wolfsburg in particular, we see their 2015 summer spending having a short-term impact on the club. Of the players they brought in, only three registered significant minutes, meaning those depth signings failed to achieve their purpose. Further, looking at the minutes from the following season, only Julian Draxler and Bruno Henrique registered any minutes, and they left the club in January 2017. That means Francisco Rodríguez was the only player to remain at the club for more than a season and a half, yet even he was sent out on loan for the majority of his five years under contract with Wolfsburg.

Monaco could really fit into this category too. Between the two clubs, we see top players helping them achieve new heights, then leave for big-money contracts with Europe’s elite. Lost in the wreckage was an inability to replace those marquee players and manage the additional strain of Champions League football.

Plugging holes in the status quo

The heading might be a bit unfair, but when you’re a Big 6 team in the EPL, evolution is a necessity. Jürgen Klopp and Pep Guardiola have revolutionised Liverpool and Manchester City respectively, and then you had an impressive Tottenham side coached by Mauricio Pochettino and the effective pragmatism of Chelsea. Since the retirement of their legendary coaches, Manchester United and Arsenal have drifted from coach-to-coach, looking to resolve cultural and tactical issues within the side. In Arsenal’s case, you could argue they were already in that phase in Arsène Wenger’s final seasons.

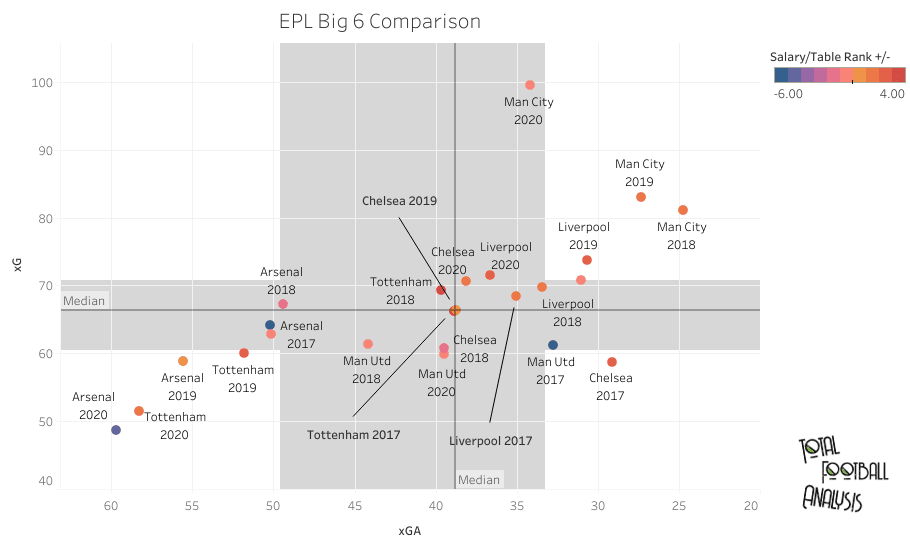

In terms of the performance on the pitch, we see both clubs lagging behind in xG. Arsenal’s four most recent sides have also performed poorly in the xGA metric as well.

It’s important to keep in mind the 49.4 average xG and xGA across Europe’s top five leagues. Last season’s Arsenal and Tottenham team were worse than the average club in expected goals for and against. Meanwhile, Manchester City and Liverpool have put together some incredible performances.

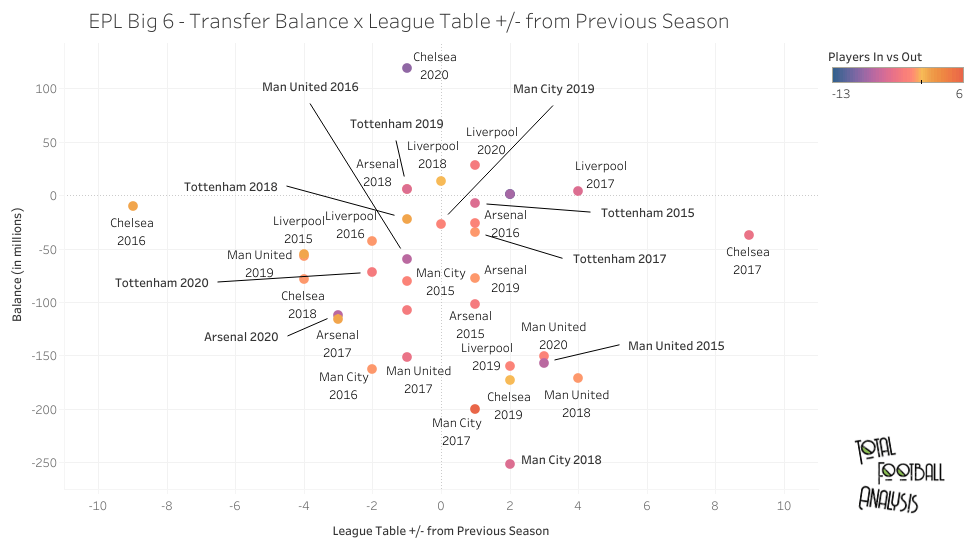

In our final chart, we’re again looking at the EPL’s Big 6. Our objective here is to gauge transfer spending and the relationship to the previous season’s performance.

Chelsea owns the two outliers in the chart. The 2016/17 performance makes sense in light of the previous season’s failure. It is interesting to note that the Manchester clubs, Chelsea and Arsenal occupy nearly all the points at the bottom of the list, showing the highest spending season’s among these six clubs. Arsenal’s top improvement is by one spot in the table (three times), yet they have fallen by three spots twice.

Manchester United nearly alternate between climbing in the table followed by a stumble. Further, far from the narrative that they don’t spend money, Man United actually spend a lot in the transfer market. Not once since the 2014/15 season have they finished with a positive transfer balance.

Meanwhile, Manchester City and Liverpool have stayed pretty consistently in the +1 to -1 range, showcasing the current stability at the clubs. They have very clear identities, making structured purchases rather than plugging the holes that emerge from one season to the next. You can see that line of thought in Tottenham’s downfall. With Pochettino out of the picture, they’re another club looking for an identity that will allow them to break the glass ceiling. They’ll hope Mourinho is the man to lead them to that much-coveted EPL title.

The last thing I’ll say on this topic is that the coaching carousel at Europe’s biggest clubs cannot be overlooked. If there is a departure from the previous regime’s playing philosophy, time is needed. Some will say coaches don’t have time and that success must be immediate, but instability at the managerial role gives every appearance of hampering progress rather than igniting a run up the table. Klopp didn’t win immediately, yet he was given the time to implement a system. Because of their faith in Klopp and intelligent moves in the transfer market, all fitting into the German gaffer’s system, Liverpool were able to hoist the English Premier League trophy.

Conclusion

It’s said that success leaves clues, but so does failure. While some pitfalls seem unavoidable, such as losing superstars to Europe’s elites, others are. Too many changes too quickly destabilise the core of the team. When that central group is lost, so is that club’s identity, both on the pitch and off. While massive investments in the transfer markets may pay off eventually, underachieving in a minimum of one season is highly likely. In some cases, like AC Milan’s, it could take a few years to rebound from a poor window.

That said, poor windows can still produce integral parts of a new core. AC Milan’s strong start to the season, in part due to the contributions of Kessié and Calhanoglu, is our case in point.

Finally, as we find with Europe’s elite, success is typically tied to clarity of identity. When that identity is lost, either through a weakening of the core, loss of key leaders or instability in the coaching role, performance and results suffer. Europe’s top teams all have a clear identity, some in a top-down approach where the coach sets the tone, others through a strong player culture.

Identity and stability are the measures of success. Elite clubs and overachievers have it, underachievers must stumble their way to it.

Comments