Théo Barbet (184cm/6’0”, 77kg/169lbs) is a left-footed, left-sided centre-back who joined Croatian top-flight side NK Lokomotiva Zagreb from Ligue 2 strugglers Dijon FCO on 1st September. The Mâcon-born Dijon academy product spent the 2020/21 season, in which Les Hiboux were relegated from Ligue 1, out on loan in Championnat National 1, where he played with Bastia-Borgo – who finished the campaign third-from-bottom of France’s third tier. During the season, the 20-year-old explained that he felt the loan spell was maturing him as a player, and perhaps as a person.

Despite his loan side’s struggles last season, however, Barbet made a good impression on many during his time at Bastia-Borgo – even managing to earn a call-up to France’s U20 side back in March. However, on returning to Dijon, the centre-back failed to make a single competitive appearance this season before ultimately departing the club for which he’d played for his entire career on transfer deadline day to embark on a new challenge in 1. HNL.

This tactical analysis and scout report will highlight why we believe Barbet’s departure will prove to be a major loss for Dijon, despite his insignificant role in their senior squad of late. We’ll provide analysis of the key strengths and weaknesses in Barbet’s game to show what Lokomotiva can expect from their new centre-back before he fits into their tactics. We’ll also explain why we believe Barbet should be tracked closely by clubs from Europe’s strongest and richest leagues, such as the EPL, Serie A, La Liga, the Bundesliga, and Ligue 1 – because he’s got a very bright future.

Defensive and physical qualities

Barbet stood out for his defensive qualities among National 1’s centre-backs last season. The 20-year-old completed an impressive 14.98 successful defensive actions per 90 last term – the highest number of successful defensive actions that were completed by any centre-back in France’s third tier to have played at least 800 minutes of football.

This highlights the volume of Barbet’s defensive actions – he was extremely active at the back for the struggling National 1 side, and much of the time he was called on, he performed well. Barbet engaged in 9.95 defensive duels per 90 – the fifth most of any National 1 centre-back who played at least 800 minutes – with a 74.75% success rate, which also ranks very well among National 1 centre-backs for the 2020/21 campaign. Additionally, Barbet made 6.16 interceptions per 90, which also ranked him highly for this metric among National 1 centre-backs last season.

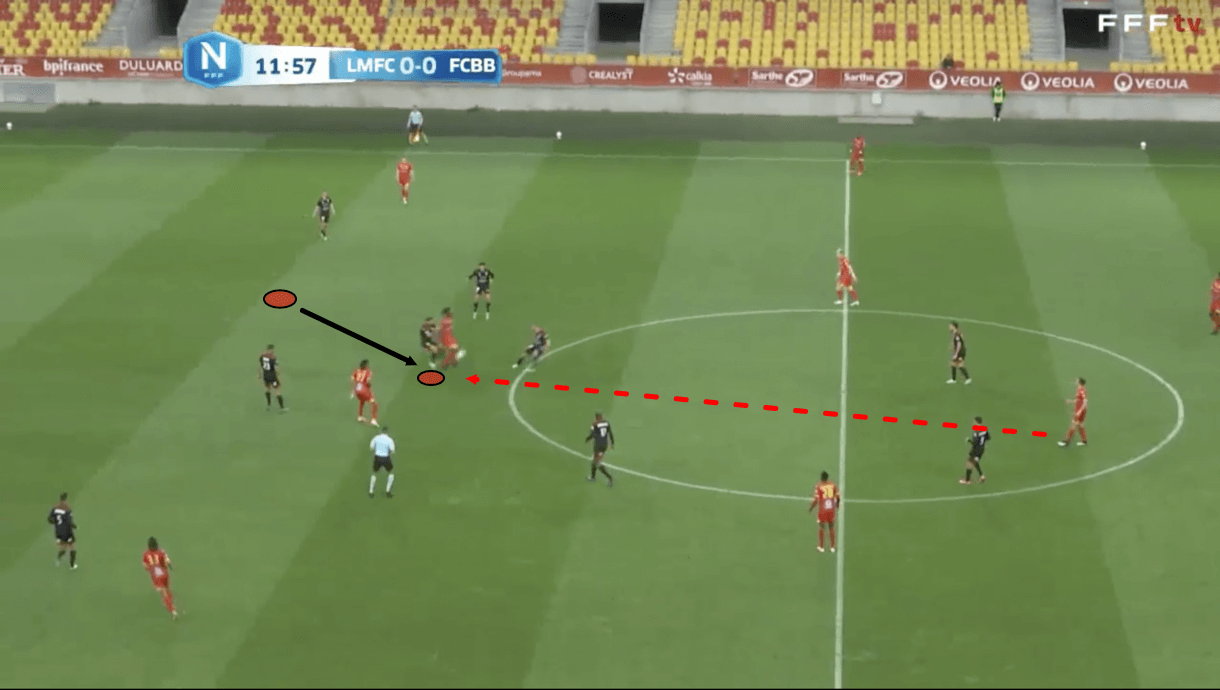

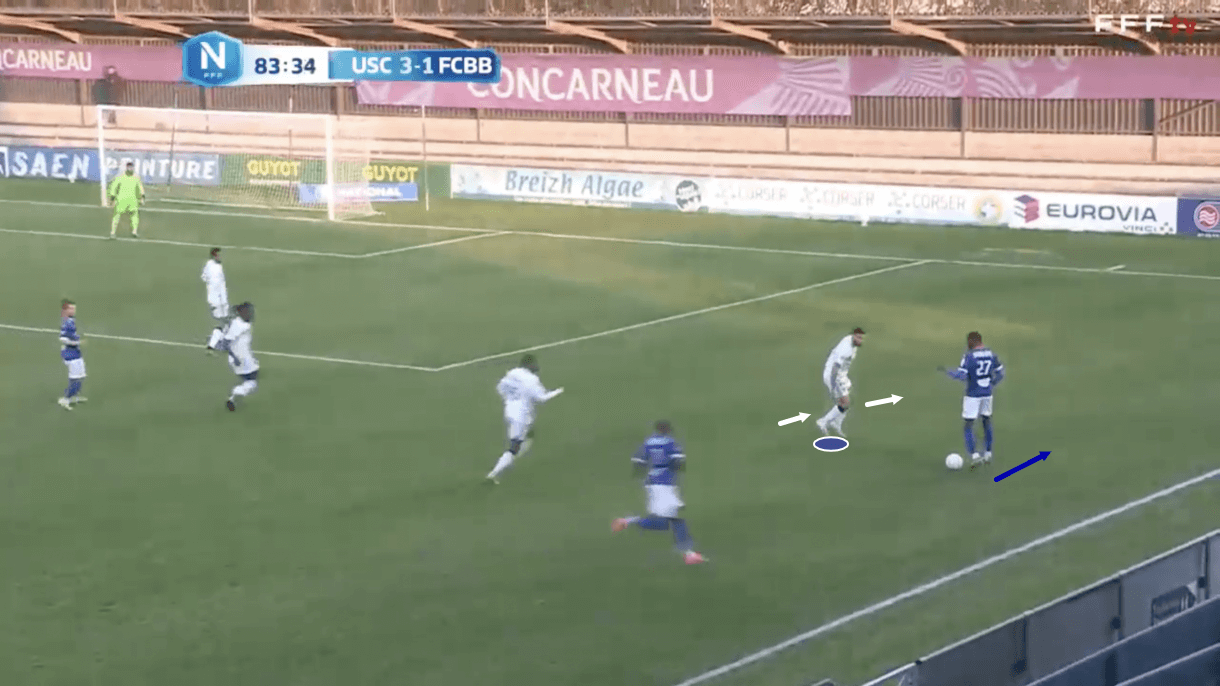

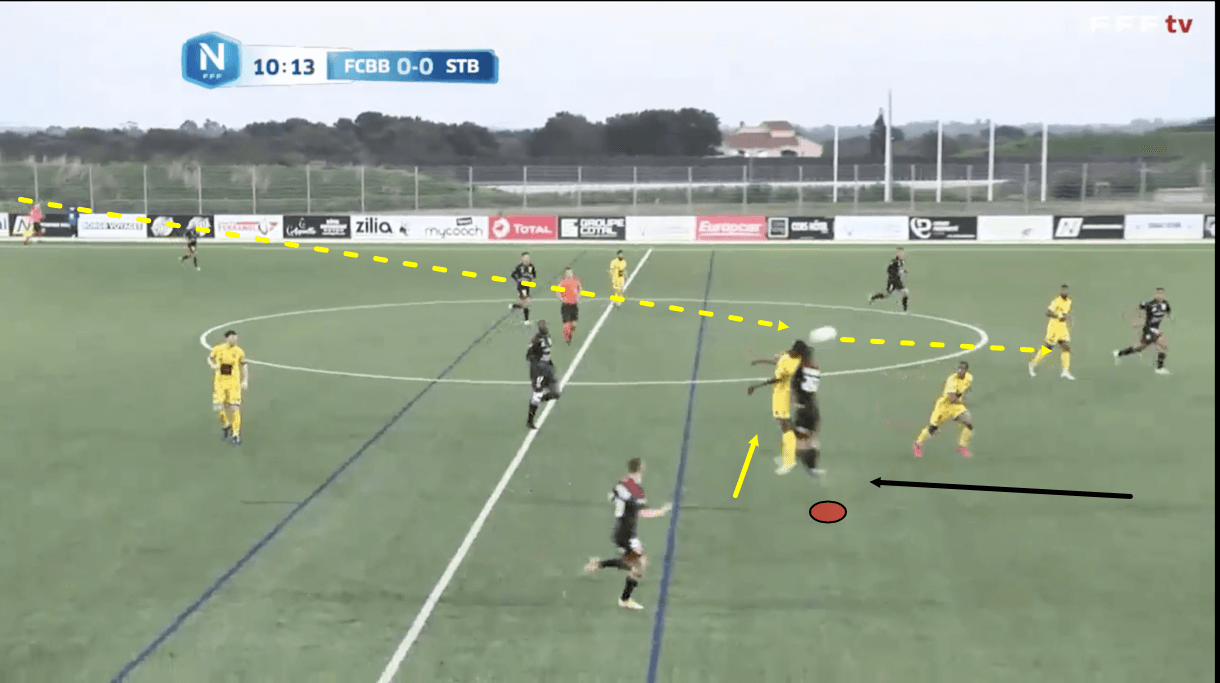

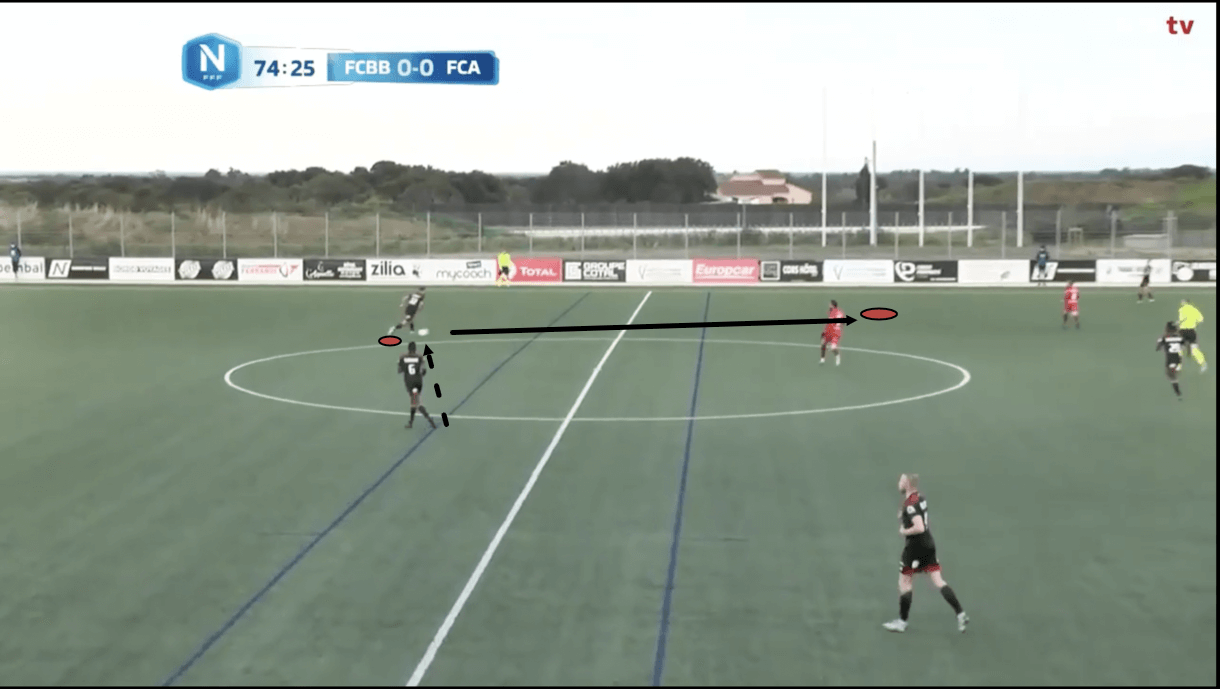

In addition to the fact that Bastia-Borgo struggled last season and were often placed on the back foot as a result, one key reason for Barbet’s large volume of defensive actions last season is his style of defending. The 20-year-old likes to defend aggressively, frequently stepping out of the backline to proactively engage opposition attackers slightly higher up the pitch. We see an example of this in figure 1, where Barbet has just stepped out of the backline, getting just in line with his holding midfield teammate to press an opposition forward receiving this forward pass.

When the pass from figure 1 was played, Barbet was sat where the deeper circle on the image lies, in the left centre-back position. As this pass made its way to the receiver, the centre-back sprung into action and got into this position right behind the forward. Barbet is generally very good at getting tight to opposition forwards and he tends to perform well, defensively, in these situations. One of the benefits of this, using figure 1 as an example, is that he successfully prevents the forward from turning or linking up with the other forward beside him just through his positioning. This turns the space where this player receives the ball for the opposition into something of a cul-de-sac, with backwards being the only realistic place to escape.

When Barbet steps out of the backline to press a deeper attacker, as well as preventing them from turning, he’s also good at forcing them into heavy touches and preventing them from just controlling the ball. In figure 1, Barbet helps the midfielder pressing this attacker from the front to regain possession for Bastia-Borgo by getting tight to the attacker, preventing him from turning or dropping back and ultimately pressing him into a heavy touch which leads to a turnover.

The 20-year-old centre-back loves to defend physically. He likes to use his strength to essentially bully attackers. He’s not an easy defender for attackers to back into when receiving the ball so they can hold up play – he’s good at holding his ground and forcing attackers to move towards the ball when receiving it – sometimes making it more difficult for them to control the pass as a result – and forcing them to move backwards, away from goal and into a less threatening area.

On occasions where attackers do manage to control the ball in situations like the one we see in figure 1, Barbet often likes to use his legs to reach around the attacker to try and nick the ball away. He doesn’t have very long legs, nor is he especially tall, but as mentioned previously, he’s good at holding his ground and getting physical. He’s happy to widen his stance to give himself a more stable base before using his legs to reach around the attacker and try to regain possession.

So, he’s not just proactive about stepping out of defence to engage attackers higher up the pitch, prevent them from turning and force them backwards – he’s proactive about controlling their movement, forcing them to be more still, and using his legs to tackle carefully and cleanly from behind to try and regain possession for his side.

You’ll sometimes see Barbet using his arms briefly to reach around attackers from behind, also to control their movement. He’s not afraid of being physical with attackers at all, he’s happy to drive his shoulder into them, get his chest into their back, and get his arms around them to keep them under his control. This can, of course, lead to him conceding free-kicks. However, he’s often able to do this so briefly and subtly that he avoids conceding the free-kick and enjoys the advantage gained from controlling the attacker that little bit more.

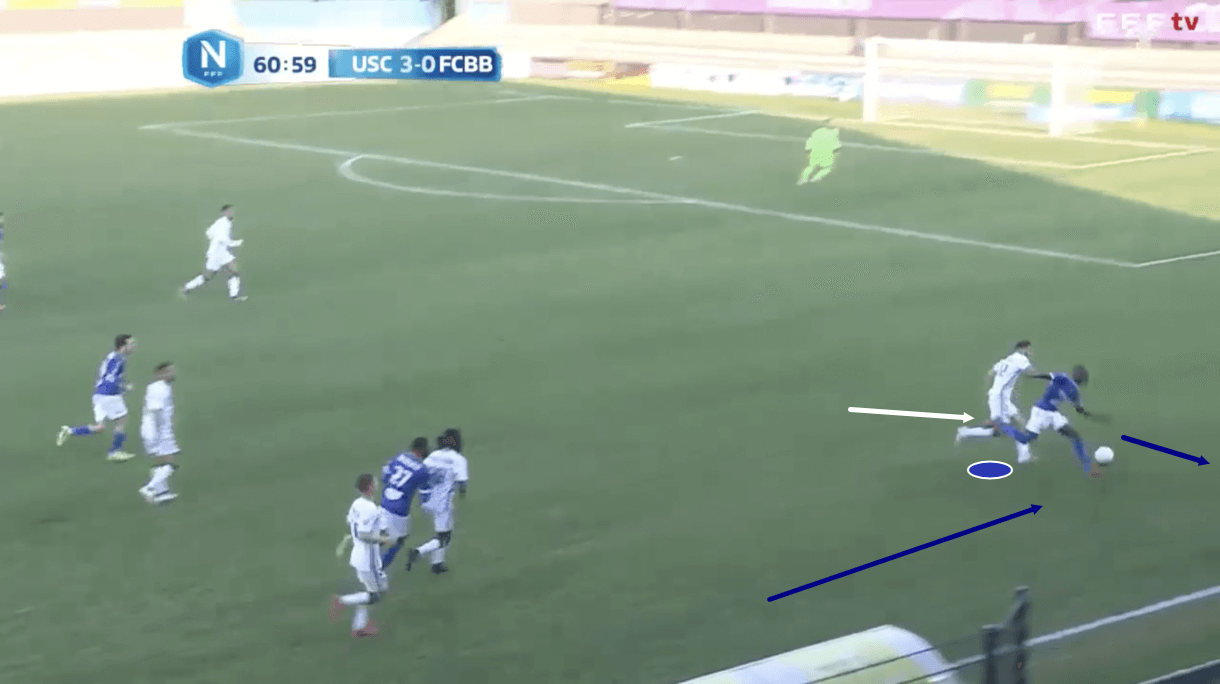

We see another example of Barbet’s physicality in figure 2. Just before this image, an opposition attacker was played through on the wing to penetrate Bastia-Borgo’s backline. Barbet reacted well to the situation, sliding across from his left centre-back position to cover this space out wide and track the attacker’s run onto this through ball. When Barbet and the attacker’s running paths collided, the centre-back sent the opposition player off track by delivering a strong, decisive, fair shoulder. As play moves on, we see the opposition attacker end up on the ground, while Barbet easily collects the ball, eradicating the danger and starting an attack for his side.

Again, this highlights how Barbet likes to get physical with attackers. He’s very comfortable with and capable of using his body to disrupt attackers’ movements and attempts to exploit the defence. If attackers want to compete with Barbet, either when getting played in behind as was the case here, or when receiving the ball to feet to hold up the play, they have to be prepared for a physical battle every time, as the 20-year-old Frenchman loves that side of the game. Attackers often can’t compete with Barbet physically, leading to situations as we see in figures 1 and 2, where the defender comes out on top of a physical duel which makes all the difference.

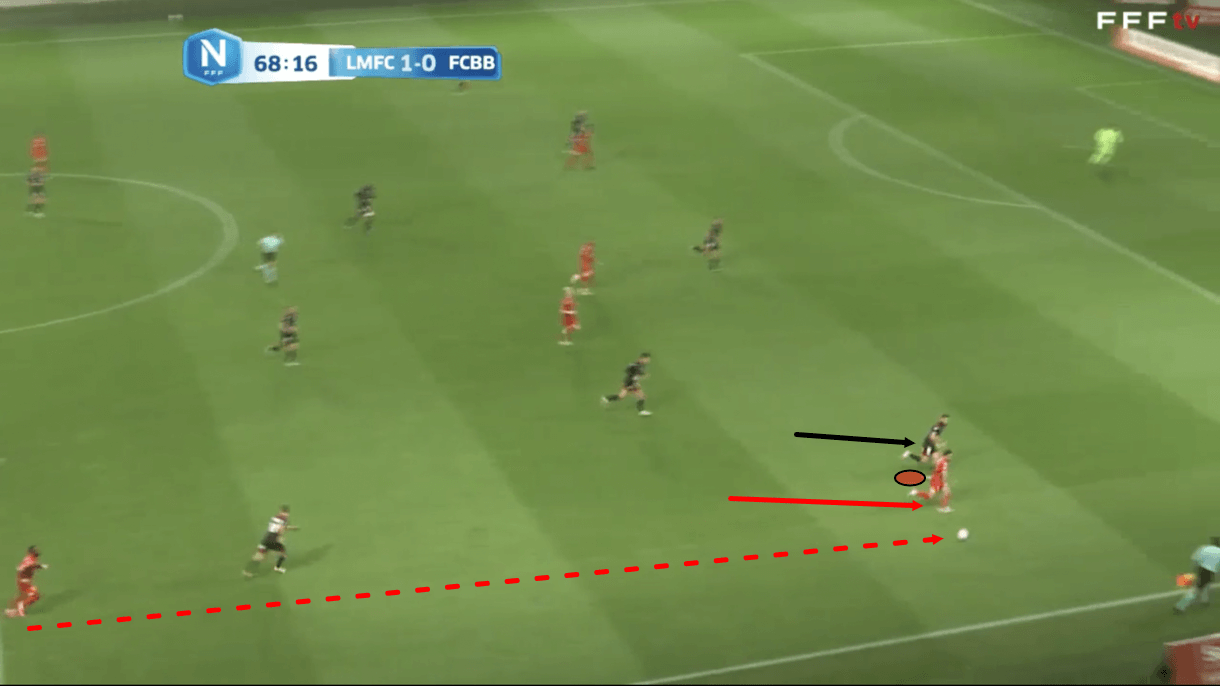

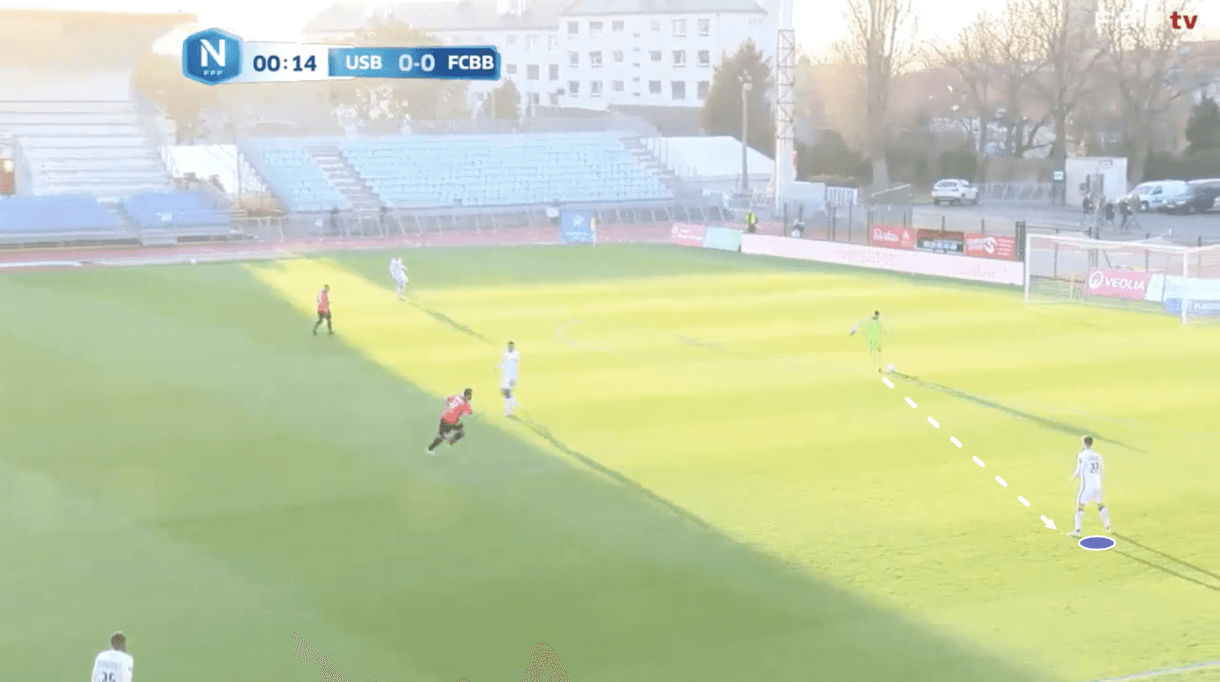

Barbet’s physicality isn’t just in his strength, but also in his speed. The France youth international demonstrated very good recovery pace last season. He’s not rapid by any means but he is very capable of providing cover if the opposition does manage to exploit some space behind the backline. It’s always an asset when a defender has a decent level of pace in his game because it gives his side the option of playing a higher line more comfortably. Figure 3, above, and figure 4, below, highlight an example of Barbet’s recovery pace in action.

Just before figure 3, just like in figure 2, the opposition attacker was sent through to exploit space behind Bastia-Borgo’s backline on the wing. Again, Barbet performed the movement we saw in figure 2 – stepping out wide to cover this space and engage the attacker. On this occasion, however, he was unable to collide with the attacker during their dribble, and so can’t perform a fair, legal shoulder. Instead, he has to compete in a race. It’s worth noting that Barbet’s angled run is less than ideal compared to the attackers run in a straight line. While these two players have the same intended destination, you’ll be more efficient in reaching that destination when moving in a straight line compared to when moving diagonally. Despite that, Barbet got ahead of the attacker, demonstrating his solid recovery pace.

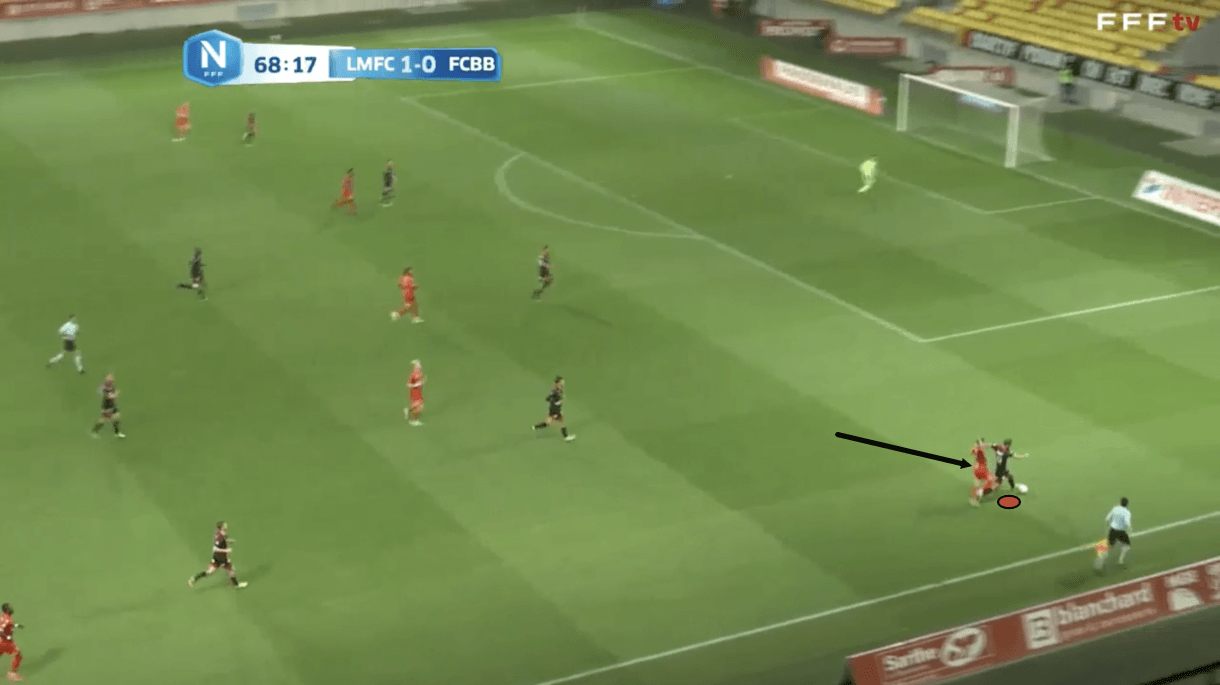

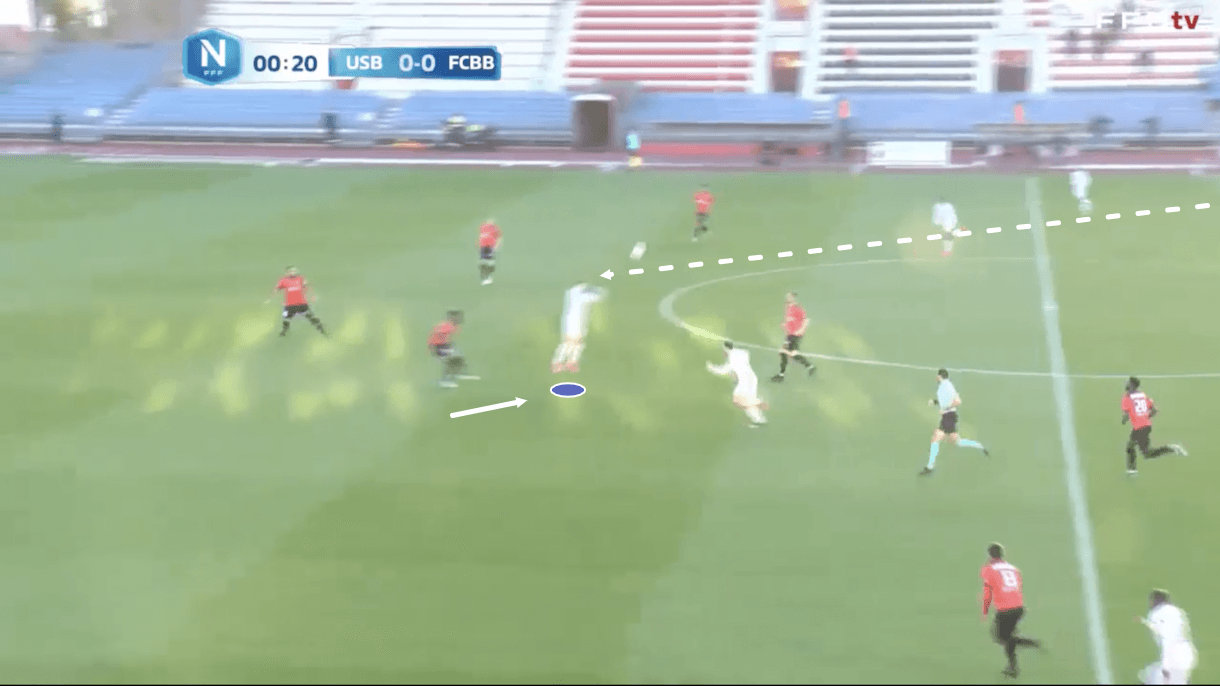

Figure 4 shows how this defensive action culminates in a turnover, with Barbet regaining possession for Bastia-Borgo. Here, Barbet did a good job of spotting danger and proactively dealing with it through his positioning and movement out onto the wing as he nipped in front of the attacker with his speed. Once in control of the ball and in front of the attacker, Barbet put his team back in the driver’s seat.

Again, Barbet isn’t extremely tall and doesn’t have very long legs. He doesn’t run with long strides that cover a lot of ground in a step, but he has strong legs which allow him to run with power and drive him into sprints like this one which helps him to cover a short distance quite quickly.

Figure 5 shows an example of Barbet engaging an attacker out wide, yet again, in a 1v1. By now, it’s clear that Barbet is comfortable defending away from goal, either higher up the pitch yet still centrally or in deeper but wider areas. This often results in 1v1s, like the one shown in figure 5, being created.

Barbet tends to perform quite well in defensive 1v1s. In situations like figure 5 where Barbet and the attacker are out wide with plenty of space around the defender for the man in possession to attack, Barbet is very good at staying on his toes, being light on his feet and prepared to turn inside or outside, reacting to the attacker’s movement. He does a really good job of not being flat-footed and caught square by the man on the ball. This helps him to avoid getting left in the attacker’s tracks due to some quick agility and dribbling quality.

At times, Barbet can get baited into committing too much in one direction, allowing the attacker to then turn and exit in the other direction but that’s the nature of his aggressive defending. Particularly in 1v1s, Barbet likes to bide his time and wait for the right opportunity to strike. If he sees a heavy touch or something like that which takes the ball a bit further away from the attacker, he doesn’t hesitate to pounce, which can leave him open to getting turned if the attacker can reach the ball quicker.

However, that’s what you get with Barbet – he’s an aggressive defender and the trade-off of winning the ball quicker/higher up the pitch is that he does leave gaps when departing from his position and he does overcommit on occasion. His very high number of successful defensive actions and high defensive duel success percentage from last season highlight that he’s generally quite reliable, however, and his defensive style works for him.

As mentioned previously, and seen in figure 1, Barbet likes to leave the backline and defend higher if situations like figure 6 present themselves, where a forward drops to receive a pass. On this occasion, however, unlike in figure 1, the attacker got to the ball quickly and managed to turn before Barbet got tight enough to him. In these situations, the space that Barbet vacated in the backline can be exploited.

However, there were also multiple occasions last season where the centre-back dealt with this occurrence very well – managing to intercept the attacker’s pass and still regain possession for his side. This was the case in figure 6. As the attacker turned on the ball, he was closed down by Barbet who managed to not overcommit and leave too much space for the attacker to simply dribble past him. Barbet’s aggressiveness combined with some intelligent positioning here to help him regain possession for Basta-Borgo by pulling off the interception.

Barbet’s aggressiveness doesn’t just allow him to engage in defensive duels high up the pitch and prevent the attacker from turning, it can also be positive if the attacker does turn, as the 20-year-old closes down the attacker, positioning himself well to block the passing lane into the space he vacated and making the interception as a result.

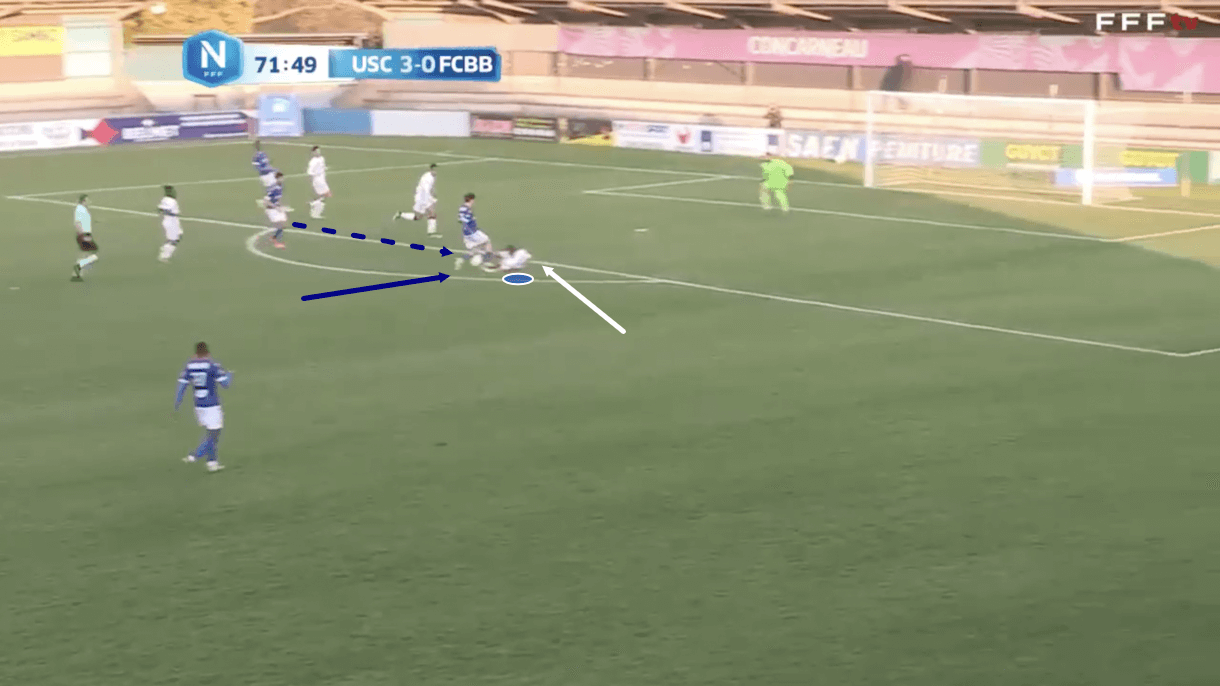

Barbet performed 1.38 sliding tackles per 90 last season – the joint-highest amount of any National 1 centre-back to have played at least 800 minutes. Again, this fits with his profile as an aggressive defender – he’s happy to go to ground more easily and more regularly than most centre-backs. Often, you’ll see him do this in situations as we saw in figures 2, 3, and 4 – where he’s defending out wide. He likes going to ground if required to prevent an attacker from progressing down the wing via a run. However, in figure 7, we see the 20-year-old going to ground centrally, which highlights an example of a riskier sliding tackle.

Barbet is happy to dive in and perform this style of sliding tackle as a form of last-ditch defending. Just before this image, the opposition attacker on the ball received a pass from the left wing, which alerted Barbet to the danger. The centre-back sprinted into action, moving from the left side of defence into this slightly more central position where he could make the tackle, which was very well timed and effective at preventing a shot from a very threatening position. This highlights the centre-back’s good sense of danger and impressive reactions. He was quick to react to the danger and sprint into position to deal with the threat effectively. As play moves on, we see Bastia-Borgo regain possession.

All in all, we view Barbet as a really well-rounded defender. Just in terms of his defensive qualities, Barbet is really effective in terms of his ability on the ground, either in 1v1s, higher positions, wider positions, or deeper positions. He’s impressive technically, in terms of his tackling quality – both standing and sliding – his ability to get tight to defenders, and his positioning. The defender is also impressive physically, both in terms of strength and pace, as well as mentally in terms of his reactions and ability to assess danger. All of these factors combined to play an important role in Barbet’s impressive statistical performance in terms of successful defensive actions in National 1 last season.

Aerial issues

Barbet engaged in 4.68 aerial duels per 90 last season, which ranks highly amongst National 1 centre-backs to have played at least 800 minutes of league football. However. the 20-year-old ended the campaign with an aerial duel success rate of just 53.68%, which isn’t so impressive. Barbet can improve his aerial quality and this section of analysis will highlight some in-game examples of his aerial ability to potentially show where some of his weaknesses lie.

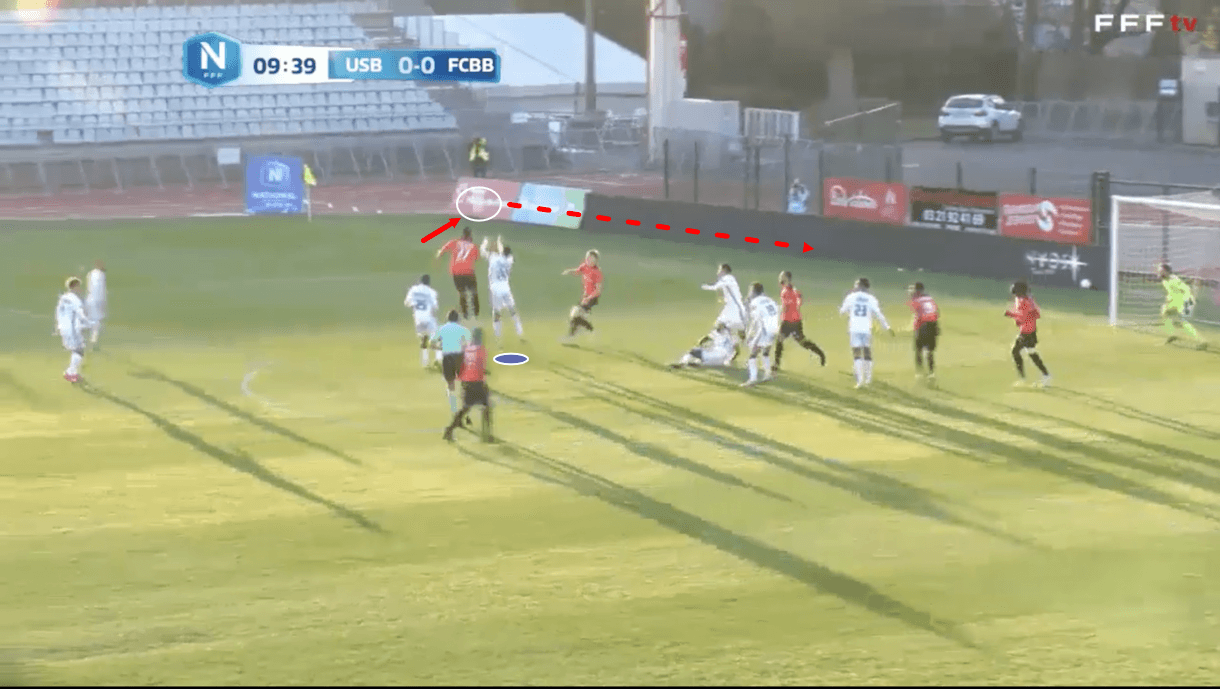

Firstly, in figure 8, we see an example of Barbet contesting a defensive aerial duel at a set-piece. Here, Barbet can be seen in white, while the opposition attacker is wearing red. As the ball gets up between these two players. We can see that the attacker is jumping a lot higher than Barbet. This isn’t a one-off, it was a fairly common sight in the aerial duels that Barbet lost last term. One area where he could potentially improve physically is with his jumping reach – he doesn’t tend to jump very high and as he’s also not extremely tall, this can lead to situations like this one from figure 8, where he’s simply outmatched in the air.

As this particular passage of play moves on, the attacker sends the ball deeper into the box, setting up a dangerous shooting opportunity for a teammate. Barbet’s failure to win the aerial duel and deal with the initial ball led to a very dangerous situation for Bastia-Borgo here, which highlights how this area of improvement can be exposed by the opposition.

Obviously, aerial ability can be a particularly glaring weakness for a centre-back, not just from set-pieces, but in open play as well. If opponents spot this weakness, they can set out to deliberately target it with an aerially strong forward and long balls from the back.

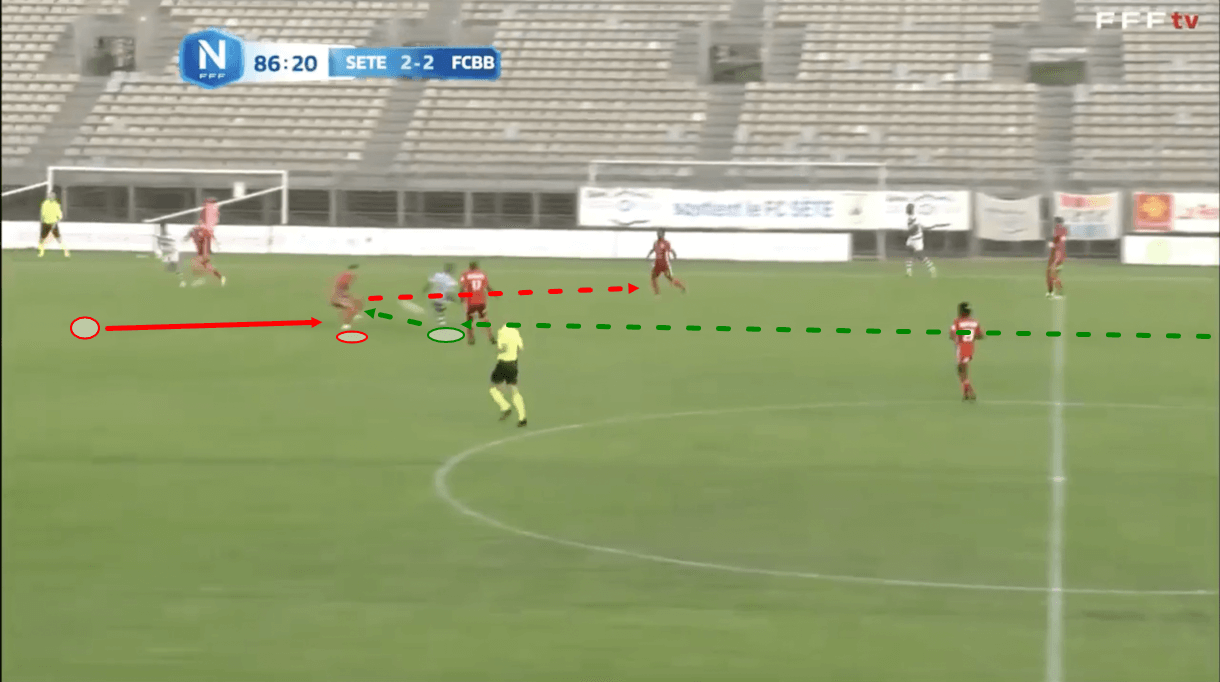

Figure 9 shows an example of Barbet contesting an aerial duel in midfield versus an opposition attacker last season. Just before this image, the ball was sent upfield from the goalkeeper while this forward dropped deeper into midfield to contest the aerial duel. This pulled Barbet – the nearest centre-back – forward as well to contest the aerial duel. As the aerial duel was contested and Barbet lost out – failing to outjump the forward and failing to do enough physically to make up for that lack of jumping reach – the opposition attacker flicked the ball on into the space which Barbet had just vacated, allowing a teammate to attack the space.

This gives us an example of how Barbet’s aerial weakness can be exploited in open play. While Barbet generally performs very well when defending on the ground and can protect the space he vacates even if the attacker manages to turn, he’s not as effective when defending aerially and if he gets dragged out of position then, as was the case here in figure 9, the opposition can exploit that space more easily.

Barbet does still win the majority of his aerial duels, but last season he ranked quite poorly in this area among National 1’s centre-backs so it is something for him to focus on as there is clear room for improvement here.

Passing

Barbet is a risk-taker on the ball and a very progressive centre-back. He’s the guy you want to rely on to drive your team upfield from the back. Firstly, Barbet played an average of 38.57 passes per 90 last season, which wasn’t a lot for a National 1 centre-back. He also ended the campaign with 78.93% pass accuracy, which is quite a poor pass accuracy rate. However, the reason for this poor pass accuracy rate is because the majority of Barbet’s passes (20.05 per 90) were forward passes, while he also played a lot of long passes (9.11 per 90) last term, which highlights his risk-taking nature on the ball.

The 20-year-old’s backwards and lateral passing accuracy was generally good. He can be a bit sloppy in possession at times and there were some occasions where he underhit or misdirected a simple short pass. However, when dealing with young players, you will get mistakes. He can be safer if needed and reliable in that situation, however, in general, he prefers to be the one progressing the ball upfield for his team much more – that’s where Barbet is comfortable.

The Frenchman’s long passing, in particular, tends to be quite inaccurate. This is partly because a lot of the time his long passing results in an aerial duel which his side could lose, but still benefit from by winning the second ball – they are riskier passes, from which losing the ball may not necessarily be a disaster. However, it’s true to say that Barbet’s long passing has plenty of room for improvement.

His 46.49% long pass success rate from last season doesn’t rank impressively among National 1 centre-backs. It was particularly common to see Barbet under-hitting long passes. He struggled with pass power quite often and seemed to have a particular issue with not putting enough on passes, resulting in them falling short of the intended target and being intercepted. So, while Barbet is very brave on the ball and demonstrates a lot of good skills, like vision, he can work on his technique in terms of judging the necessary weight of the ball better.

In figure 10, we see an example of Barbet receiving the ball from the goalkeeper during build-up in his typical left centre-back position. He prefers to play on the left side where he can use his stronger left foot to open up his body and enjoy a wide passing angle range. The fact he’s left-footed helps him in build-up when being pressed by a striker, which is evident from figure 10. Here, the striker is pressing him from the inside, which is very common. This suits Barbet down to the ground, however, as he can receive the ball, turn, and open up his body while taking the ball onto his stronger left foot to progress play comfortably, without most of his passing lanes being cut off by the press from inside.

Additionally, if passing to the left-back which is a pass that Barbet frequently likes to play, being left-footed helps him to avoid potential interceptions as his pass will naturally curve away from midfield as opposed to towards it. Some coaches will value a left-footed centre-back on the left side more than others – ultimately, a player is fine to play wherever they are most comfortable – but you’re more likely to come across a coach who dislikes having a right-footed player on the left than a coach who dislikes having a left-footed player there, so it’s a benefit of Barbet’s that he ticks this particular box.

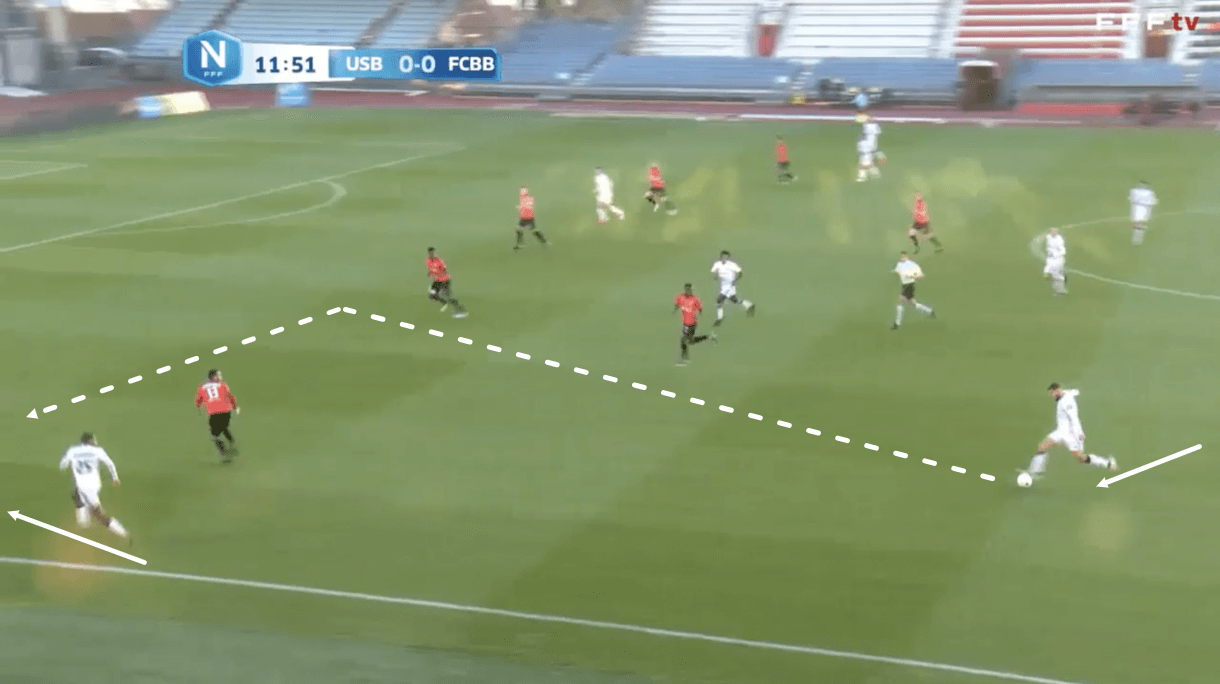

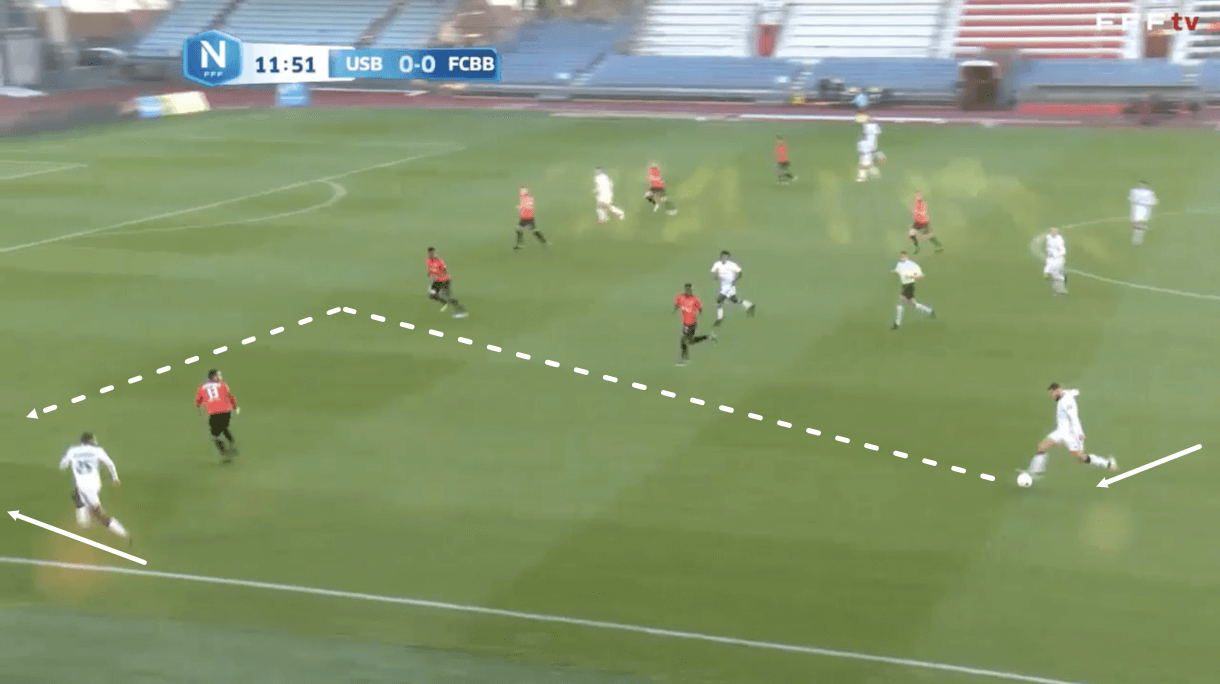

As this passage of play moves on, we see Barbet take the ball forward a couple of steps and send it long, aiming for the centre-forward. This results in the scene we have in figure 11, where the centre-forward drops deep to take the ball down from the air. Here, we see an easy opportunity for the target man to link up with his attacking teammate running through, targeting space beyond the target man, highlighting how effective this type of long ball can be in getting the team into an advantageous attacking position quickly.

When Barbet’s passing is accurate, his tendency to play these types of passes frequently from the left centre-back position can be really beneficial for his team as a playmaking tool. If he can work on his passing accuracy to play more long balls of this standard regularly, then that will only mean good things for his team’s attack.

In figure 12, we see an example of Barbet in a slightly more advanced position, aiming to play his left-back teammate behind the opposition’s backline. The teammate has made a threatening run and is right on the shoulder of the defender here as Barbet lines up his pass. It’s very common to see Barbet driving into positions like this from where he can play lightly chipped through balls over the top in search of the left-back or winger running in behind. This is an example of Barbet linking up with the left-back, which, as mentioned, is a really common combination. He likes to use this player a lot, as opposed to playing crossfield balls which are more likely to be under-hit – a tendency of his.

In contrast, he can play these chipped through balls down the left wing more safely and accurately, helping his side to break down the opposition while being more confident in retaining possession. Through his movement out wide onto the wing, Barbet can help his team to overload this side as well. On this occasion, he drove forward from the left centre-back position and enjoyed a lot of freedom, essentially becoming the free man. If the opposition’s right central midfielder pressed him, then the Bastia-Borgo midfielder beside him would’ve become free, while the opposition right-back couldn’t press Barbet and free up the left-back either, so we can see how the aggressive, advancing centre-back can create a lot of problems for the opposition through his movement, in this example creating a 3v2 wide overload.

Lastly, figure 13 will show us an example of Barbet’s preferred on-the-ball movement. In addition to playing progressive passes, Barbet likes to run forward with the ball to a certain extent as well. We saw an example of this in figure 12, and that wasn’t a one-off. The same thing happened here in figure 13. Barbet received the ball deep in the left centre-back position, got his head up, and targeted space to exploit deep in the left half-space.

We know that Barbet can easily help his side to create wide overloads via this kind of movement. He either drives forward into space and doesn’t attract attention, allowing him to play a creative ball from a dangerous position, or he does attract attention, thus freeing up a more advanced teammate.

As is common with Barbet, there’s an obvious risk involved, in that he’s vacated space at the back which could be exploited in transition. However, on the ball, the 20-year-old is a great asset for what he offers his side in terms of ball progression and risk-taking. He likes to play long balls from deep, as seen in figures 10 and 11, but he’s at his best in the ball progression phase, like figure 13, where he can drive forward to get in position to play a more creative pass by either finding space for himself or creating space for a teammate.

Conclusion

To conclude this tactical analysis and scout report, we feel Barbet has a lot of exciting and useful assets on the ball and off the ball, in terms of passing and defending. Overall, he can be described as aggressive. He excels in ground duels, in terms of his physical, technical, and mental attributes. Meanwhile, he’s a very progressive defender on the ball who loves to drive forward into space to help his team create chances.

The 20-year-old can improve in terms of his aerial ability and long passing ability, while, as with any young player, there is some improvement to be made in terms of decision-making and concentration, particularly on the ball to cut out moments of sloppiness, especially with passing. However, we feel that Barbet is an extremely exciting talent based on what he showed in National 1 last season, he would’ve been a great asset for struggling Dijon in Ligue 2 this term, and we’re excited to see how he adapts to Croatia and shows his ability with Lokomotiva this season.

As alluded to elsewhere in this piece, a good left-footed centre-back can be a hot commodity in the right market. When you throw in the fact that he’s good at progressing play, he’s fast enough to cover space in behind, and he proved to be so solid in defensive ground duels last season, that all makes Barbet a centre-back that must be tracked closely. If he can work on his areas of improvement in Croatia and continue his development at a higher level than National 1, expect Barbet’s name to become a lot more prominent and his value to increase over the coming years.

Comments