The 52-year-old German coach Thomas Letsch is very much a part of the new breed of football coaches.

He has secured opportunities in first-team settings without ever playing the game professionally.

That does not mean, however, that his current position as head coach of Vitesse Arnhem in the Dutch Eredivisie represents an overnight success.

Instead, Letsch has spent time building and learning his craft as a coach, most notably as part of the coaching setup at Red Bull Salzburg.

He is now in a position to show his game model to the watching world.

He initially made his first steps in professional coaching through different clubs in the German lower leagues.

He was an assistant at Stuttgart Kickers and then at SSV Ulm, where Ralf Rangnick also coached, before moving across the border to join the coaching staff at Red Bull Salzburg in Austria.

Even then, his position was never truly in the limelight.

He was in charge of the U16s and then the U18s before becoming the caretaker coach in charge of the first team for a couple of matches when Peter Zeidler left the club.

He then took charge of FC Liefering, a side that plays in the second tier of Austrian football but effectively acts as Salzburg's B team.

In 2017, we saw Letsch move away from the Red Bull umbrella to return to Germany with Erzgebirge Aue and then return to Austria the following season with Austria Vienna.

Before starting the 2019/20 season, Letsch agreed to take charge of Vitesse as the club sought to transition to a more modern playing style.

Having adopted many tactical concepts synonymous with the Red Bull group, Vitesse is emerging as a surprise challenger for the Dutch title.

Undoubtedly, Thomas Letsch is a coach to watch going into 2021.

Thomas Letsch Style Of Play

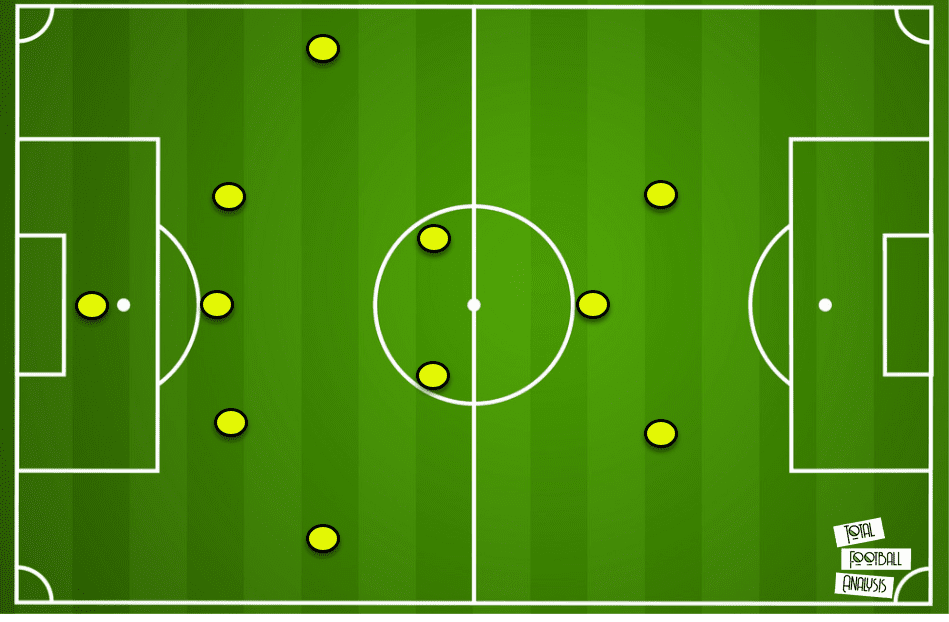

So far this term, at the time of writing, we have seen Vitesse favour something approaching a 3-4-1-2 system with a very structured look in the attacking phase.

They look to attack their opposition through quick combinations of vertical passes that move the ball through the thirds and towards the attacking goal.

There are interesting rotations throughout the attacking structure, as players rotate in and out of pockets of space to empty space and receive passes that break the lines of the opposition's defensive structure.

In the defensive phase, perhaps unsurprisingly for a coach brought through the Red Bull system, Vitesse defended aggressively and pressed the immediate point of transition.

In more prolonged periods out of possession, the 3-4-1-2 system will quickly transition into a 5-3-2 with a compact defensive structure that makes it difficult for the opposition to play through and break down the defensive block.

Thomas Letsch Defensive Phase

While Vitesse are aggressive in the initial stages when the ball is lost, their PPDA (passes per defensive action) is 9.65 at the time of writing.

This does not mean that they do not cover the threat of the press being played through or beaten with relative ease.

Their initial defensive action tends to involve the two forwards pressing and engaging the man in possession for the opposition.

At the same time, the ‘10’ will typically drop onto a deeper line to cover the threat of a central pass being played past the line of pressure.

While one striker presses, the other tends to angle their run to try to force the player in possession into the area that the second striker is occupying.

This is intended to force the opposition to either play into a dangerous area or into a long pass to escape the press.

This press also has a secondary purpose: Behind it, the rest of the Vitesse players will typically drop back into a more structured shape to cover their defensive third.

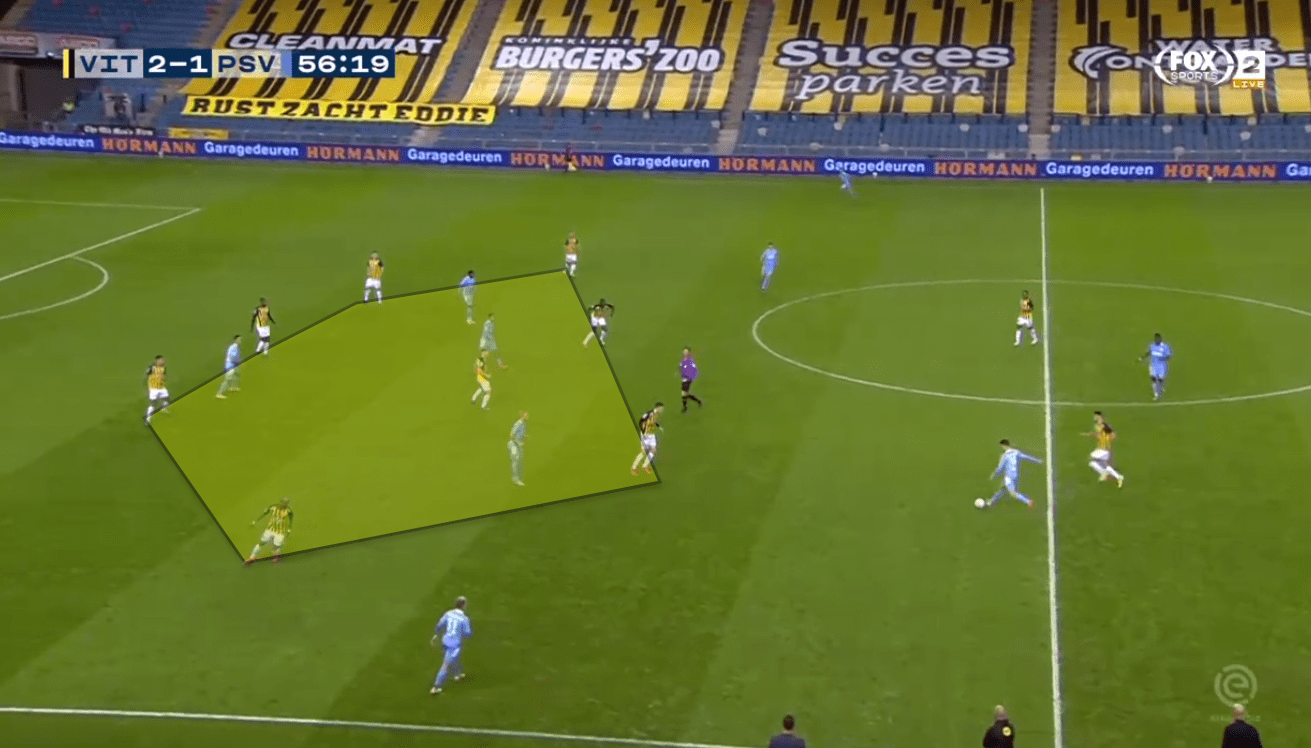

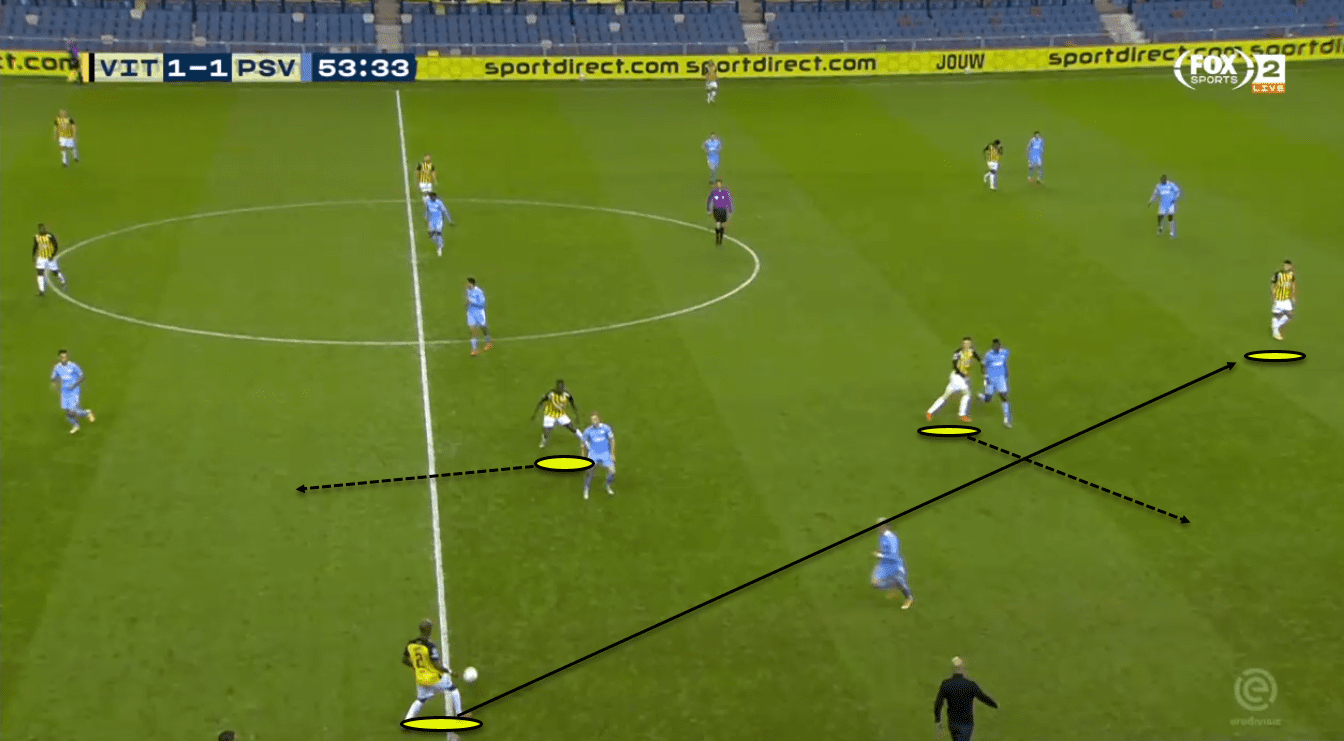

We see an example of this here: the opposition has outplayed Vitesse's two-man press, and with the ‘10 having dropped in to form part of the block, there appears to be time on the ball for the opposition player in possession.

Vitesse has effectively denied PSV Eindhoven any opportunity to play vertically into the central areas of the pitch.

Under Letsch, they work hard to deny these spaces and passing lanes.

As such, the opposition is typically forced to look for ways to attack down the outside spaces in an attempt to play around the defensive block or force Vitesse to break players away from the main defensive structure.

In this example, the option is to switch play diagonally to the far side of the pitch.

The Dutch side, however, are extremely flexible and well coached and the defensive structure moves well in a pendulum style in order to move over to close down threats in the wide spaces.

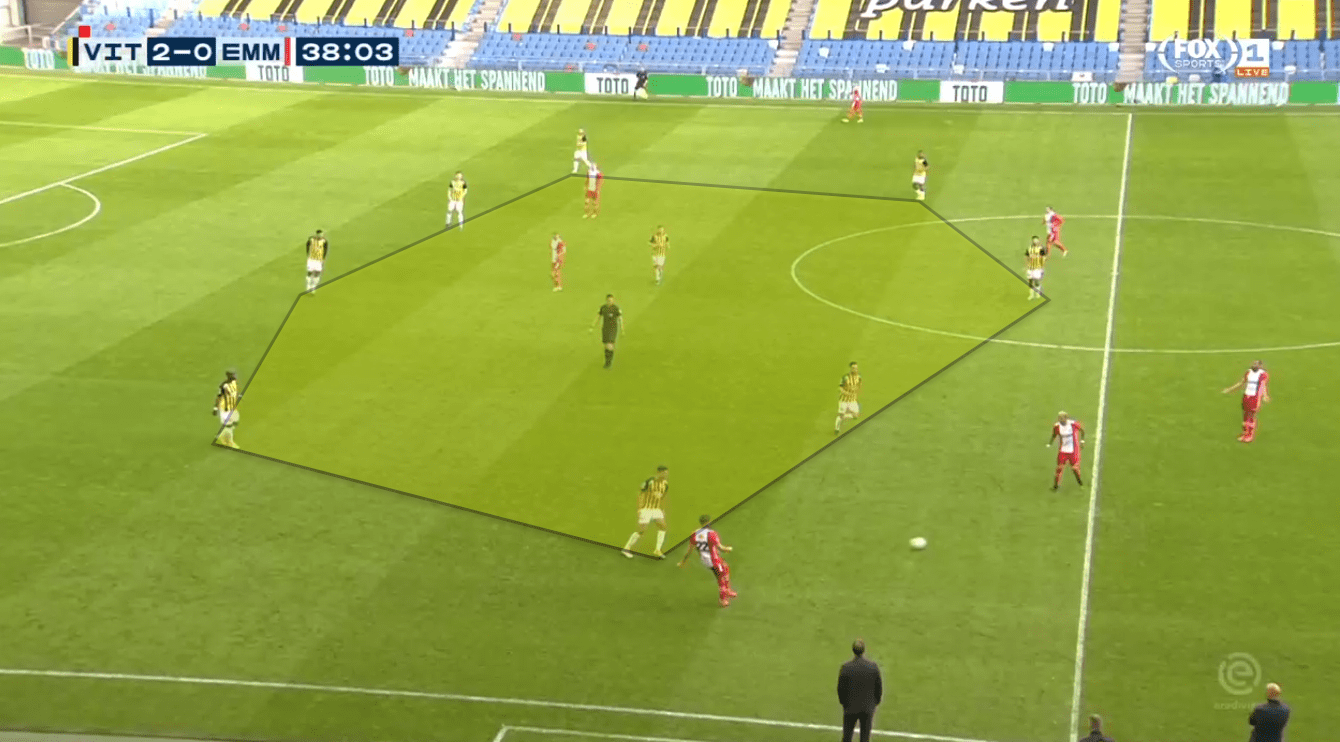

We see a similar situation here with the two ball near Vitesse players working to ensure that they keep their bodies positioned to prevent the Emmen players from finding passing angles or lanes that will allow them to access the central areas in the field.

This forces the opposition to continue recycling the ball backwards towards their own goal.

As they do so, the defensive block for Vitesse can simply press forward to control the space on the pitch and deny the opposition attack any space into which they can attack.

Thomas Letsch Attacking Phase

In the attacking phase, Thomas Letsch's coaching style uses many aspects of the game model that mirror those of teams within the Red Bull group. Still, the main focus surrounds two key concepts: vertical passing and rotation movements.

Under Letsch, Vitesse are not a team that progresses the ball slowly or through slow passing in the build-up.

Quite often, the ball is played quickly and directly, with former Ajax player Riecheldy Bazoer, in particular, being a key part of their ball progressions.

Bazoer was highly rated as a young prospect but was seen more as a box-to-box midfield presence.

Now, Letsch is having great success using him as a controlling player in the middle of the three-man defence.

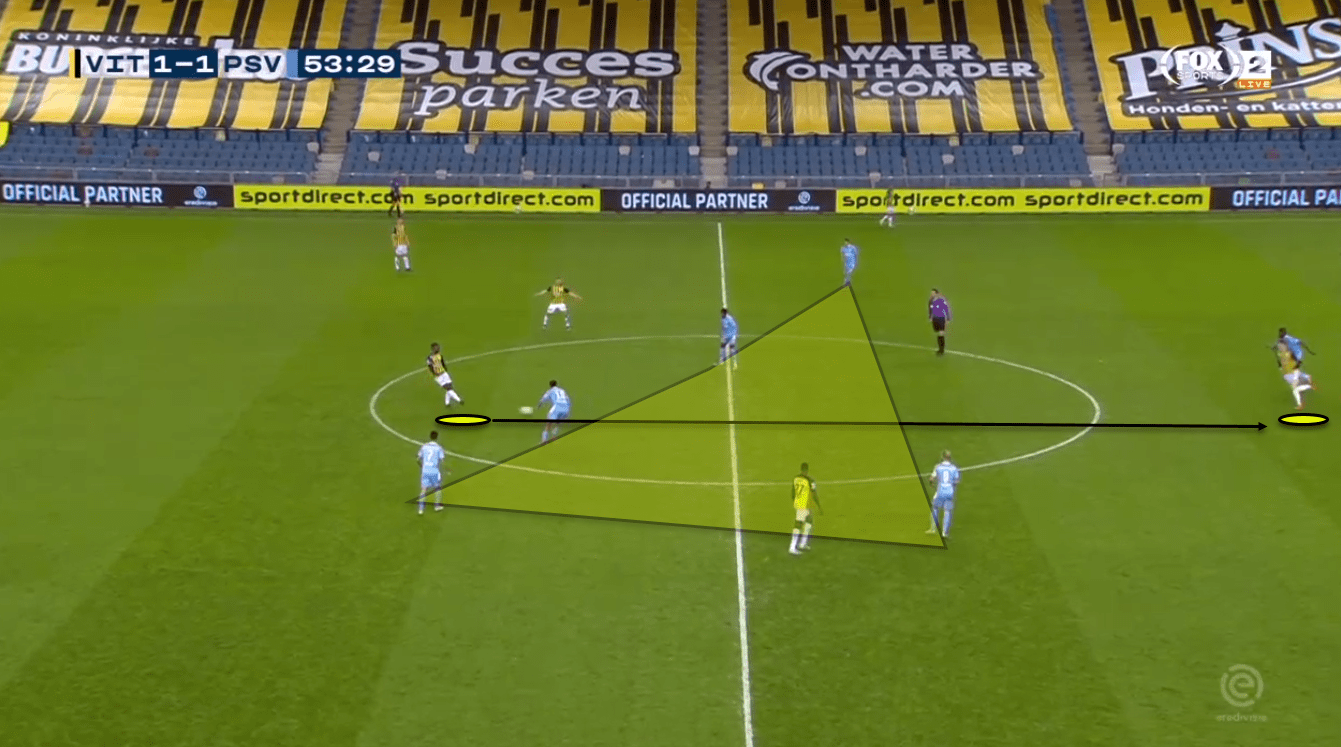

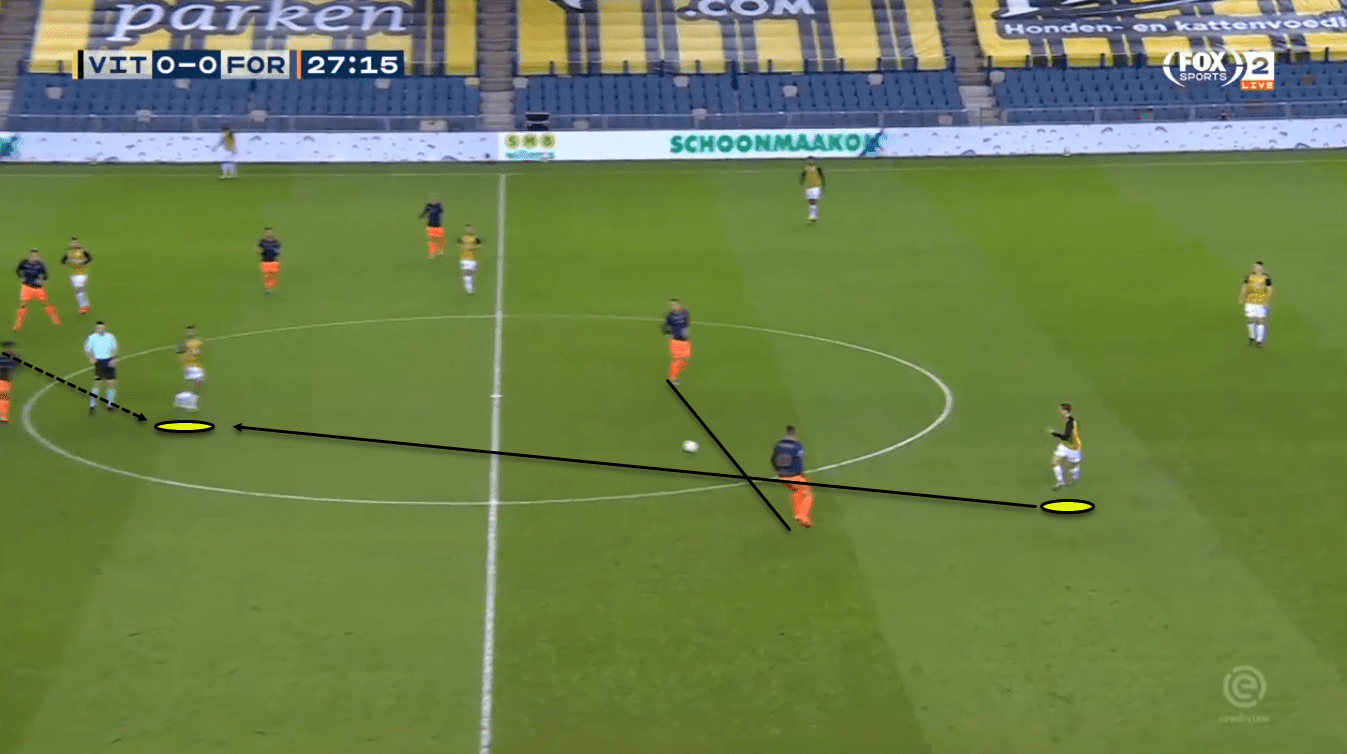

This is an example of this vertical passing style, with Bazoer in possession just inside his own half in the match between Vitesse and PSV.

We can see that there is a teammate in a lateral position that is demanding a pass.

Bazoer rightly ignores this option and plays a vertical pass that cuts through the central area of the PSV structure.

With this single pass, Bazoer removes five opposition players from the game and creates an opportunity for his team to play from an advanced platform.

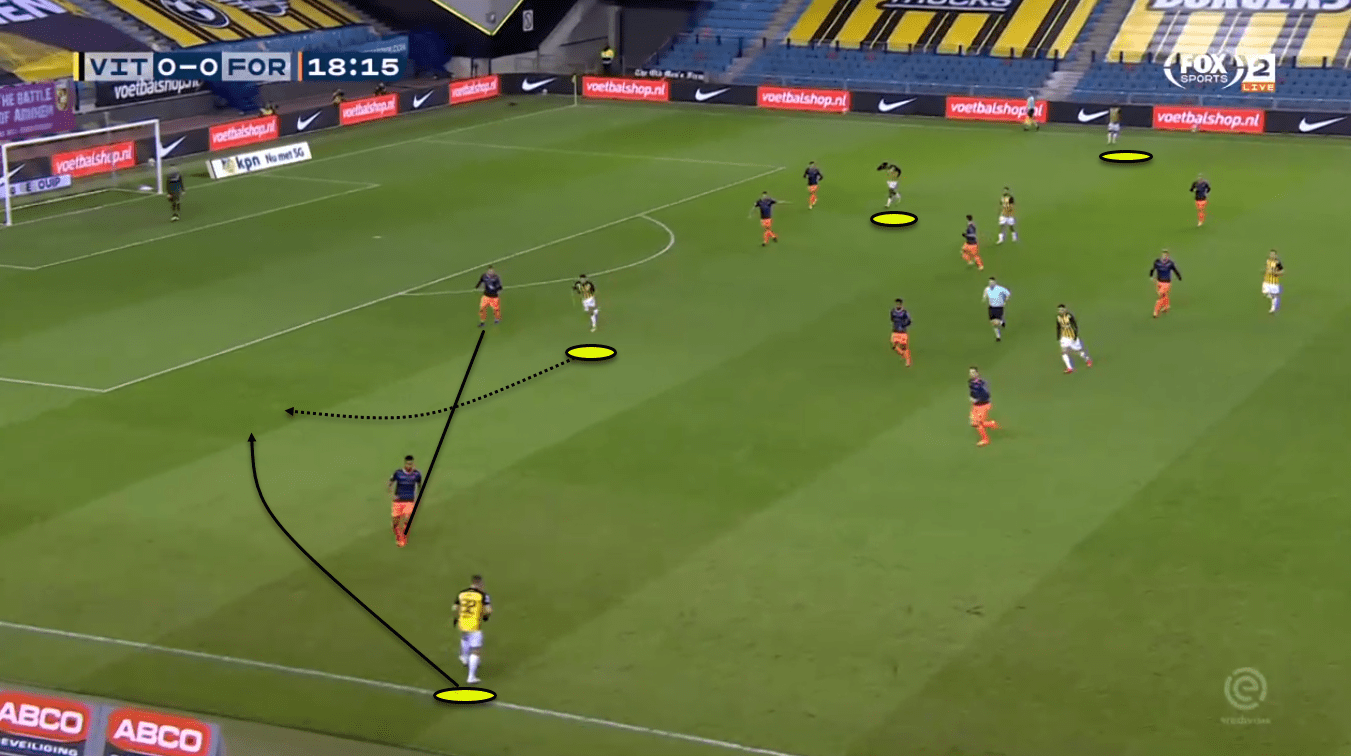

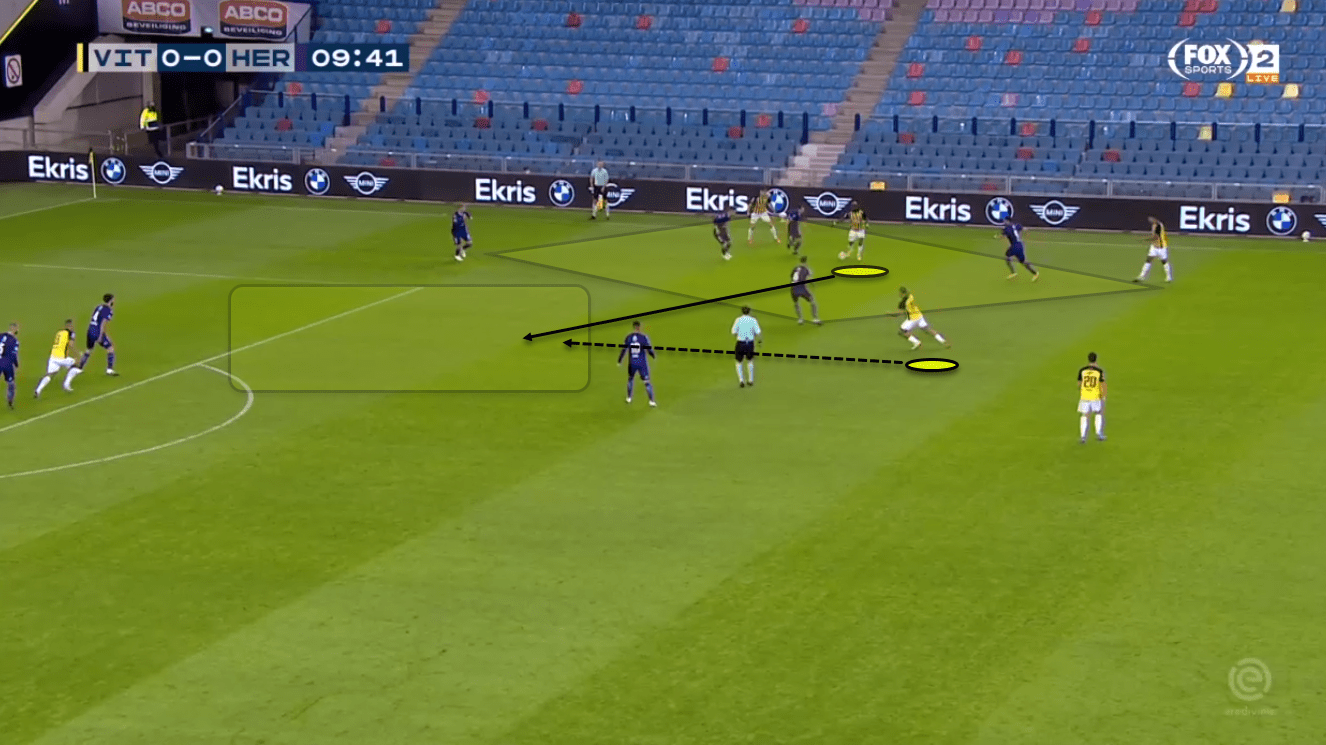

This time, we see a slightly different situation from the one in the match between Vitesse and Fortuna Sittard.

On this occasion, the opposition defended in a much deeper and more compact defensive structure.

This time, the vertical pass is a tool that affects the defensive positioning of the opposition.

Vitesse's defender is not under any significant pressure in the first instance, so he has time to wait for a teammate to move into a position to receive.

This is achieved through rotation, with players emptying the passing lane and then others moving to occupy the space.

As these rotations take place, the vertical pass can be played.

This pass then forces opposition players within their structure to move out to try to engage with the ball.

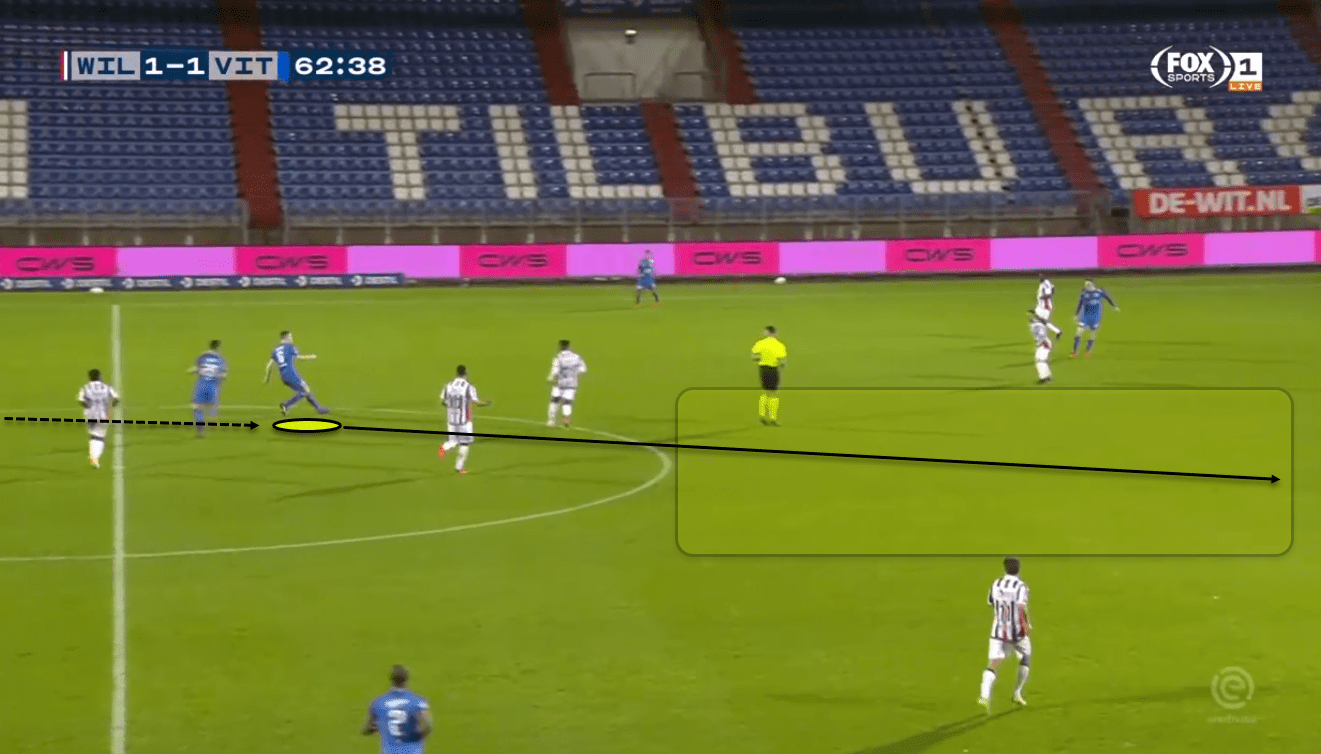

The third example that we will use to show the use of verticality in Thomas Letsch’s system shows a defender taking the initiative to move into advanced areas before playing the vertical pass through into the feet of advanced players.

The defender stepped forward in possession of the ball and attracted pressure from the opposition team.

Eventually, players step in to engage him and stop the run, and he can again find the pass that breaks the opposition's lines.

Vitesse is dangerous to play against in the more established attacking phase because they effectively space the pitch and stretch the opposition’s defensive structure.

We see an example of this in action here, as Vitesse is in possession on the left side of the pitch.

The positioning of the two wing-backs, who moved quickly to a higher line when Vitesse won possession and started their attack, creates space within the opposition's defensive line.

This spacing forces the opposition fullback, on the ball near the side, to move out to engage.

Immediately, this stretches the connection between that fullback and the central defender on that side of the pitch, and these are the spaces that Letsch tends to want his team to attack as they move through into the final third.

Rotations in the possession phase are a vital part of the game model that Letsch has implemented at Vitesse.

At times, their attacking players can seem to be in constant motion, with people dropping or stepping up onto different lines and the opposition's defensive players being pulled and dragged all over the pitch.

In this example, Vitesse have possession on the right.

The two nearest players move and rotate, with one dropping deep to provide an angle and one moving wide to give an option outside.

These rotations pull players out of their defensive positions and allow the man in possession to play a penetrating pass to the highest line to progress the ball through.

When the ball is in the final third, these rotations also occur, with players moving from deeper positions intended more to offer support lanes.

These movements tend to occur on the opposition players' blind side, with attackers moving into advanced areas to connect with the man in possession and create opportunities to play into the penalty area.

In this example, the player in possession is initially positioned to the right, and Vitesse has created a strong structure on that side of the pitch.

The supporting player moves vertically into the highlighted space to collect possession and attack the penalty area.

Conclusion

In a short time, Thomas Letsch has firmly imprinted his game model and tactical identity on this Vitesse team.

He is part of a growing group of coaches positioned around Europe who have their roots in the Red Bull system.

They are taking lessons learnt there and putting their own spin on things.

There is no doubt in our minds that the German coach is one to watch for 2021, with the potential to make a bigger move at some point.

Comments