Fabrizio Romano once again turned the football world upside down.

On Thursday 23rd of March, the Italian journalist announced that Bayern Munich was replacing Julian Nagelsman with former Chelsea manager Thomas Tuchel.

While Bayern

is undefeated and in the quarter-finals of the UEFA Champions League, Die Roten have failed to continue their 10-year-running league dominance domestically.

With a win-less three-game run in January and occasional losses, Nagelsmann struggled to run away with the Bundesliga trophy.

Many consider sacking the 35-year-old manager harsh and, if anything, a terrible decision.

The financial aspect, from his appointment to his sacking, is far too significant to dismiss.

Nagelsmann is one of the most promising managers in the world, and while he may still have his shortcomings, allowing him to see out his potential at a Champions League rival is another factor to consider.

Most importantly, the long term seemed extremely promising with Nagelsmann, but now with Tuchel, it is less certain.

While the 49-year-old undoubtedly brings success, he has struggled to build sustainable long-term projects in his career, staying no longer than two years at Borussia Dortmund, PSG, and Chelsea, respectively.

Regardless, the decision has been made, and this season is the biggest concern.

Thomas Tuchel comes in with the responsibility of immediately putting his hands on the UCL trophy, as he did with Chelsea, as well as retaining the Bundesliga title for the 11th consecutive time.

However, it’s nearly April.

Time is not Tuchel’s ally, and the German manager will have to hit the ground running.

So, how will this transition look?

Tactically, Nagelsmann and Tuchel have apparent differences – and some essential similarities.

This season has seen Julian transition from a more rigid structure with a possession-based mentality to a more fluid structure, reliant on the individual talent at his disposal.

Thomas Tuchel’s coaching style provides a different approach, with a heavier focus on flexible yet rigid structures.

Despite these structural differences, the initial organisations and formations are somewhat similar, and this will undoubtedly make for a smoother transition.

On the other hand, the defensive side of the game will potentially see a vital improvement.

Die Roten have conceded far too many goals on a few occasions, and while their superiority in the league can often mask this side of the game, it could be lethal in the latter stages of the UCL.

Tuchel led the Blues to European glory by humbly defending deep and secure for long periods of time, in addition to an unforgettable defensive start to the 2021/22 Premier League.

This tactical analysis will take a deep dive into the tactics behind the transition from Nagelsmann to Tuchel.

After briefly identifying how Bayern have looked under Nagelsmann, this analysis will explore what Tuchel brings to Munich and how Die Roten could look under the former UEFA Champions League winner.

From fluid…

This season has seen a significant change in the tactics at the Allianz Arena.

Nagelsmann famously favoured possession and rigid structures, and the statistics confirm this.

In last season’s UCL, Bayern averaged 63.67% possession, compared to just 55.85% this campaign.

The team has become more vertical, with less focus on dominating possession.

Similarly, the positional rules have been lifted, and players like Thomas Müller and Leroy Sané have enjoyed much more freedom to roam.

Let’s begin with the organisation.

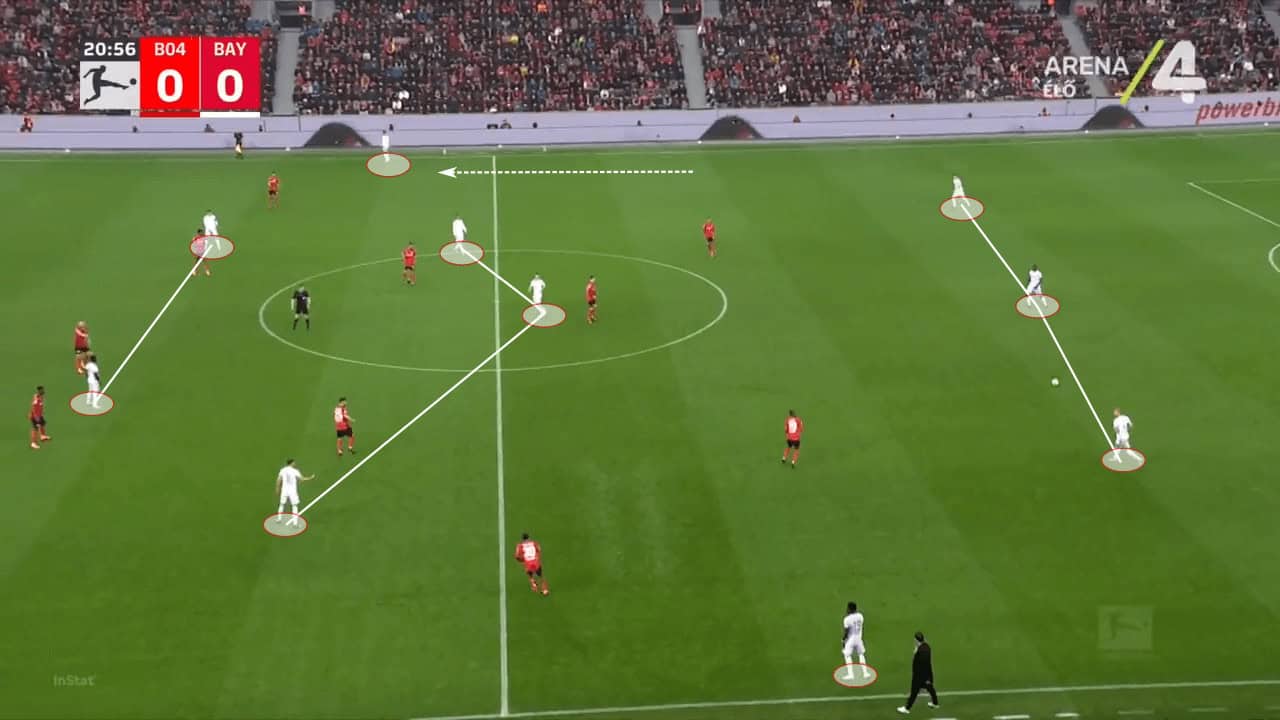

The back three formed by asymmetrical fullbacks is still there, although Alphonso Davies begins slightly deeper on the left.

Rather than a double pivot, Joshua Kimmich has been entrusted with the single pivot role ahead of two free 8s, usually Leon Goretzka and Sané or Jamal Musiala.

Kingsley Coman or João Cancelo will be on the right side and Thomas Müller is partnered with either Sadio Mané or Eric Maxim Choupo-Moting.

While Goretzka naturally performs as more of a fixed number eight without significant roaming, Musiala or Sané are the complete opposite.

Regardless, the midfield three is collectively very mobile and supportive.

Against PSG, Choupo-Moting was deployed instead of Mané, providing a more fixed number nine role.

The midfield three can be seen supporting the play while Matthijs de Ligt advances with the ball.

Davies pushes up while Müller roams elsewhere.

It is important to note the positioning of Coman, the opposite wide player.

With Tuchel, the opposite wide player will be expected to play a similar role of maximum width and depth, as it was with Reece James or Callum Hudson-Odoi, for example.

The importance of this role can be quickly identified in the example below.

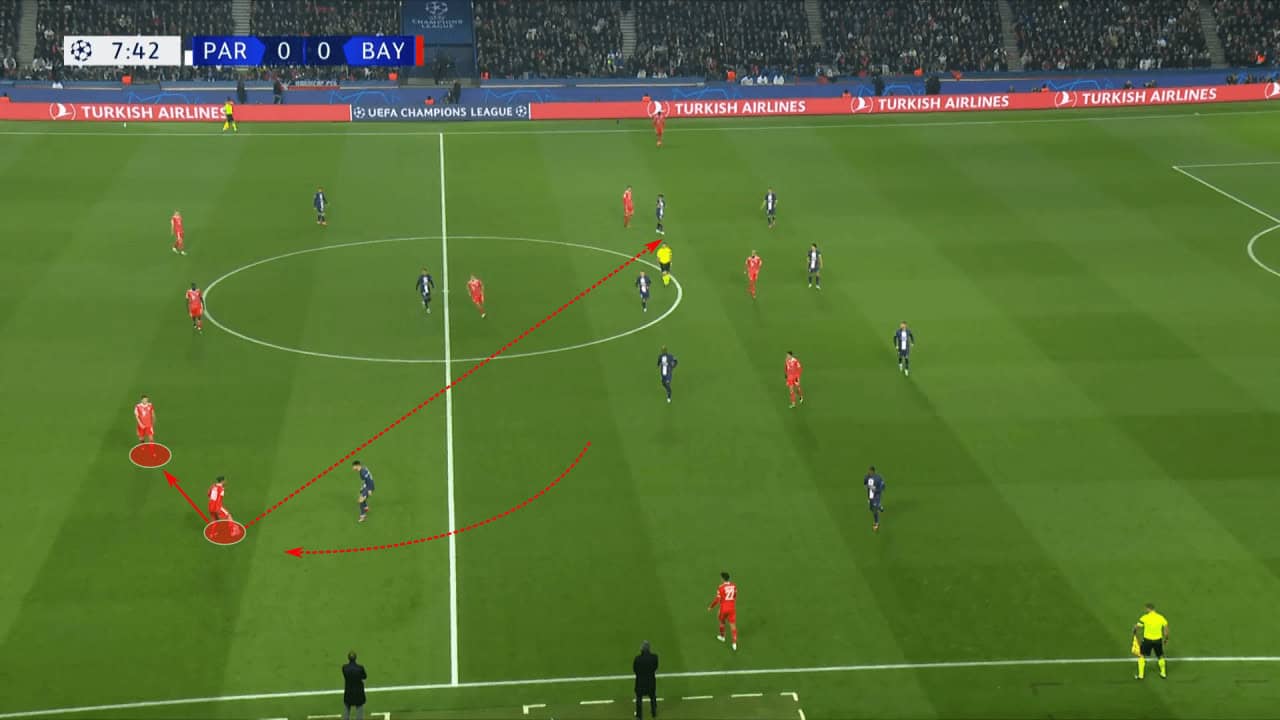

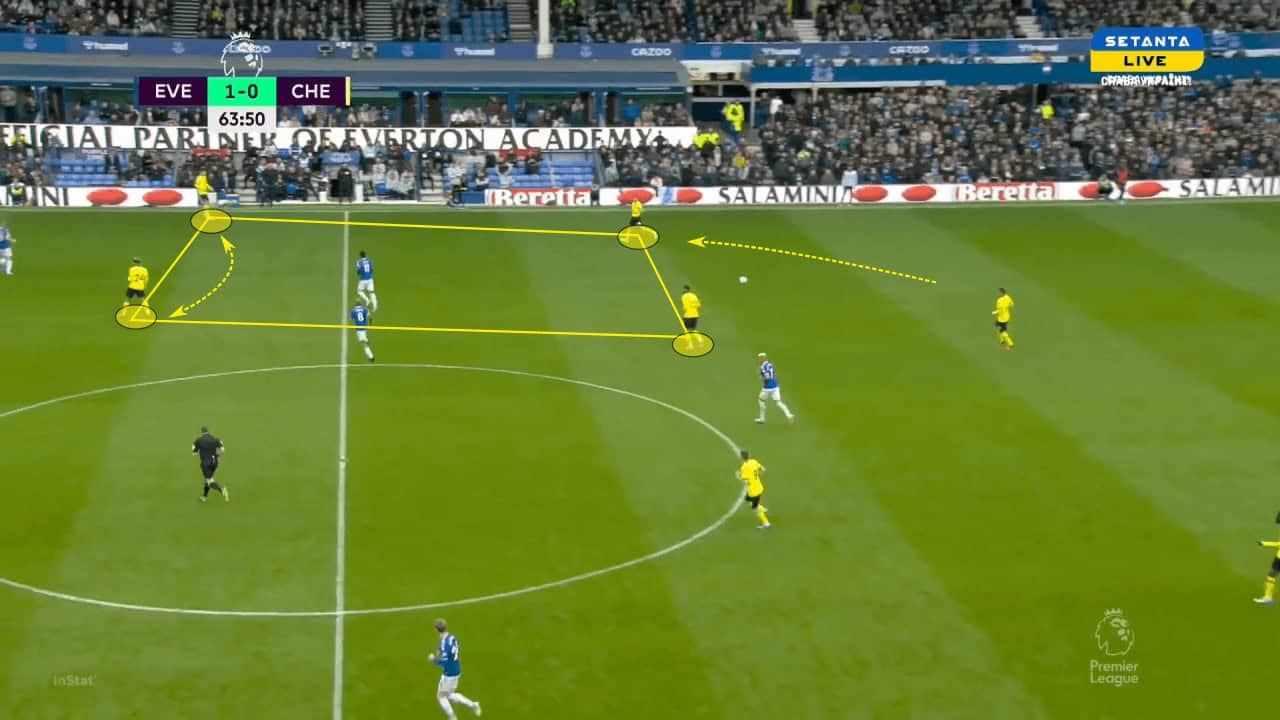

As Bayern focus on the right side, PSG collectively shift their defensive block over.

Kimmich, with a quick switch, finds Davies with space to attack the far side.

This pattern can be expected to continue under Tuchel as one of a few important attacking similarities.

However, as mentioned, there has been significant fluidity in Bayern’s structure this season.

Take the instance below, for example.

Sané comes deep to play with Benjamin Pavard, and as possession begins to develop on the opposite side, the former Man City player freely roams into the opposite half-space.

This positional freedom was not standard in Chelsea’s Tuchel, and the general lack of fluidity in the structure will be a significant change for the players.

It is important to note these are merely characteristics of a structure, not determinants of success.

Style of play is just that, a style.

Whether Bayern will improve or not, there are unlimited other factors in the equation.

Müller’s role under Tuchel coaching style will be interesting to follow, as the German legend is known for his intuitive ability to find space and roam.

In the example below, he roams to the wide channel to become free and receive the ball from Dayot Upamecano.

It is possible Tuchel will give him the more free number 10 role as he did with Mason Mount in some instances.

However, with that, other problems arise with this, especially one named Musiala and his generational talent.

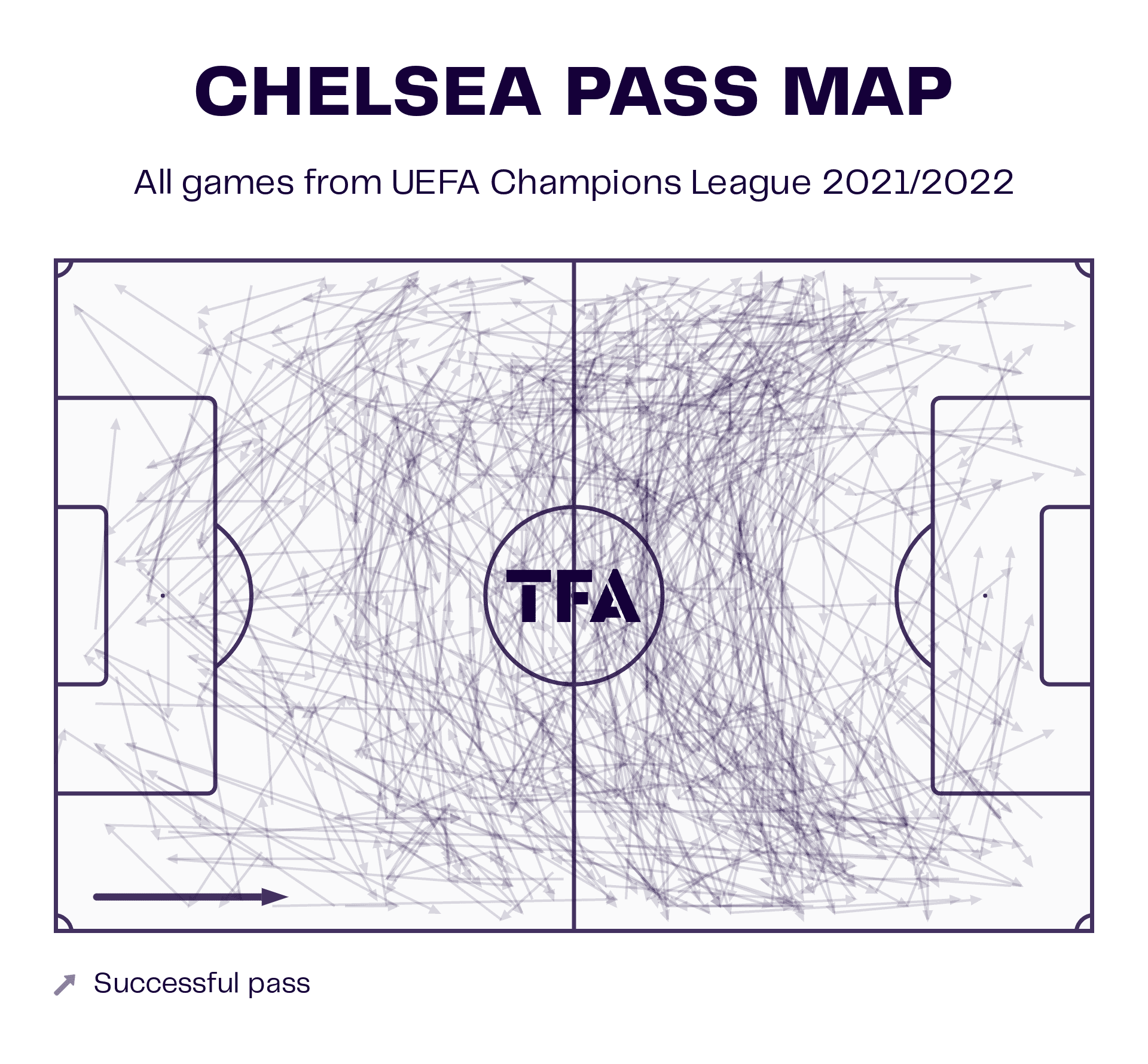

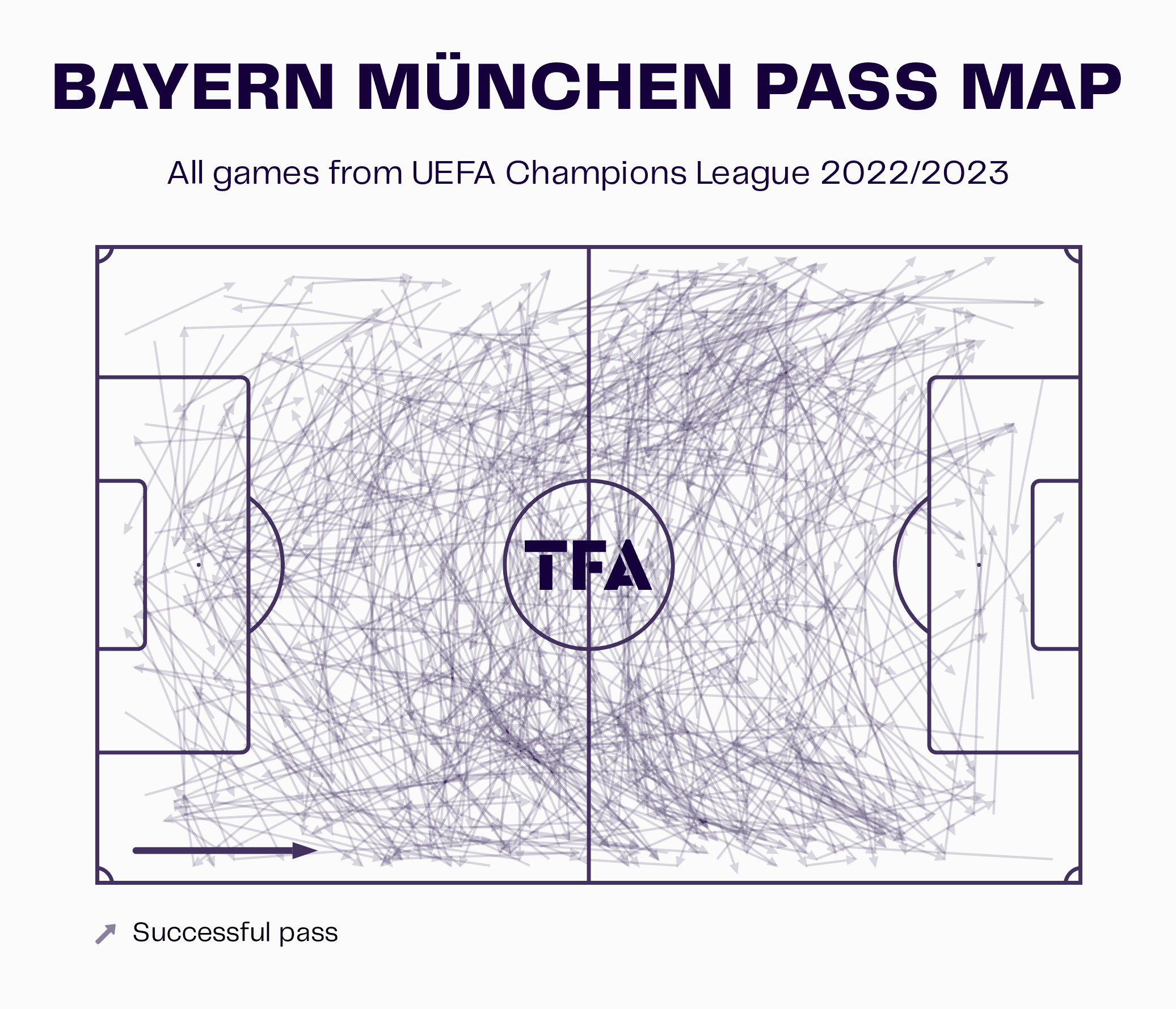

As we transition into how Die Roten will play under Tuchel’s tactics, let’s explore the pass maps from Bayern in this season’s UCL and Chelsea’s in the last campaign under Tuchel.

The Blues have a much more significant concentration entering the final third than in the earlier stages.

This difference can perhaps be attributed to Bayern’s increasing verticality.

Additionally, Bayern’s heavier concentration in the build-up phase highlights a willingness to construct attacks from the beginning, whereas Chelsea was happy to play it safe and get the ball away from the goal in some knockout matches.

There are undoubtedly differences in the possession approach, both structurally and in mentality.

A significant part of Tuchel’s success this season will be attributed to his ability to implement these changes quickly.

To flexible

While Nagelsmann’s Bayern was fluid, Tuchel’s Chelsea was flexible.

Tuchel’s structures were consistently linear and imposed rather than emergent, and positional rotations were methodically executed.

Aside from the free 8s, which could be continued with Müller and Musiala/Sané perhaps, there was not much room for fluidity.

On the other hand, flexibility was crucial.

The German manager was very effective in deploying players in different positions and seamlessly adapting organisations, heavily dependent on the opposition.

His methodical and relatively rigid approach to structure in possession was perhaps the reason for such successful flexibility.

Regardless of the adaptive nature of his structure, there was a platform, or maybe initial organisation, from which they adapted from.

With slight tweaks, collective or individual, the organisation remained relatively consistent throughout his time at Stamford Bridge.

This organisation began with a 3-2 shape at the back, with a compact double pivot ahead of a back three.

Ahead of this 3-2, two wide players maintained width while two central midfielders were more advanced behind one striker.

A consistent variation was deploying two strikers with just one advanced midfielder, and this lone midfielder consequently had more freedom.

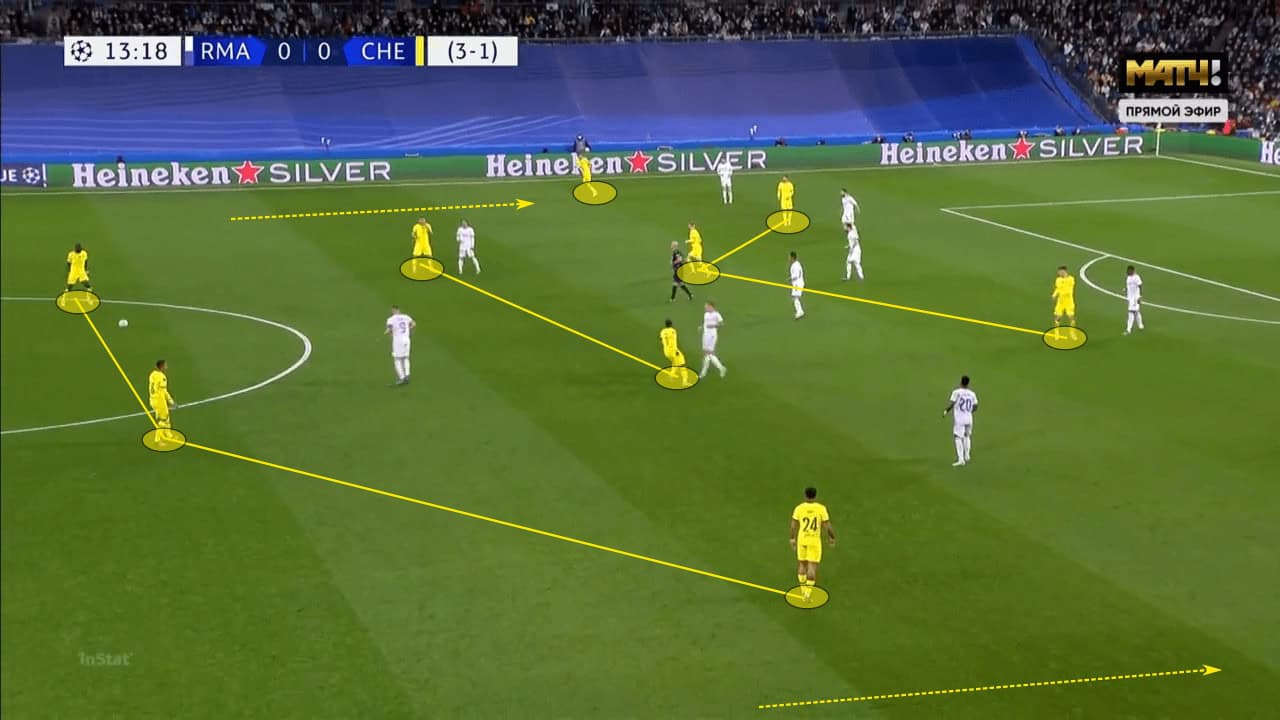

If they selected to build wide, the relevant wide player provided support along with the respective defensive and advanced midfielder, as identified below.

The support and ball progression were methodical and systematic, but the deployment of these organisations was very flexible.

Relating it to Bayern, we can begin to identify a potential organisation.

The back three will remain the same, with Pavard tucking in along the centre-backs.

The wide players, with Coman/Cancelo and Davies, could also be the same.

The double pivot is where it becomes interesting.

Kimmich is a given, probably alongside Goretzka.

Müller and Musiala/Sané would be the advanced midfielders ahead of the two, with either Mané or Choupo-Moting up top.

Like Chelsea, this would be a starting point from which adaptations and rotations could emerge.

One clear variation would be with a more fluid front three.

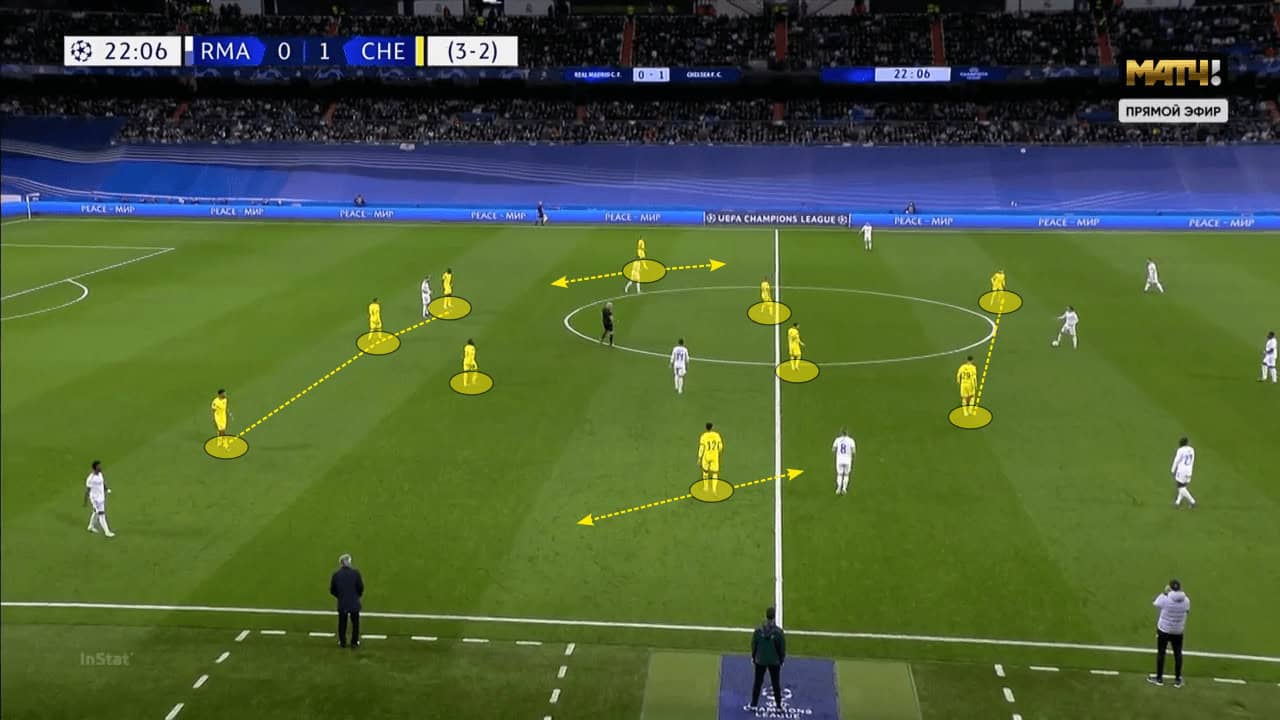

Whereas Choupo-Moting can be that fixed nine in front of two advanced midfielders when needed, Tuchel has Sané, Müller, Musiala, and Mané from which to build a fluid front three, as he did against Real Madrid.

On the other hand, with Choupo-Moting and Mané together up front, Tuchel can deploy a single 10 with the freedom to roam and support, as he did with Mason Mount on some occasions.

Müller is the clear man for the role.

However, he could instead go as one of the centre-forwards while Sané or Musiala perform this 10 role.

Bayern’s squad is extremely versatile, and under Tuchel, this versatility will undoubtedly be explored.

Before moving on to the defensive side of things, positional rotations must be discussed.

In Tuchel’s structure, they still exist, although not as natural and fluid as under Nagelsmann.

On the contrary, they were methodically executed.

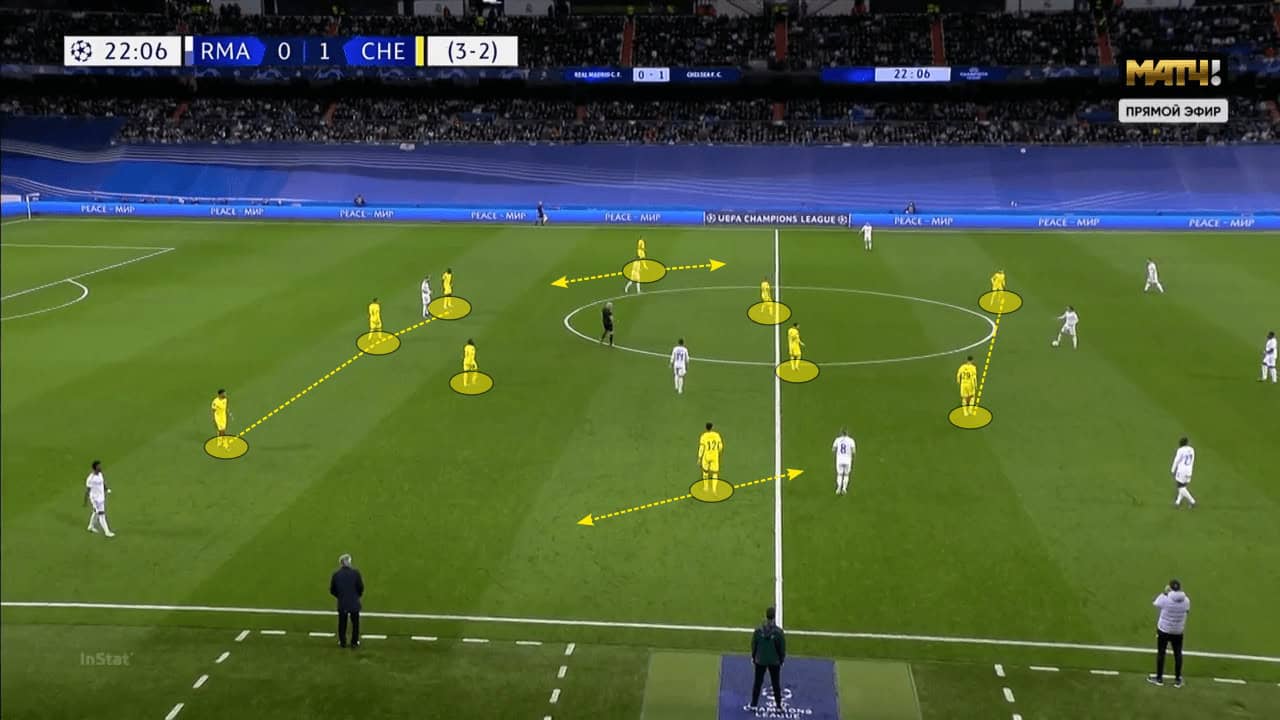

For instance, as identified below, the wide player coming inside while the advanced midfielder jumped wide was extremely common.

Although with a different nature, this feature of the structure will continue from Nagelsmann to Tuchel.

Defensive flexibility

Bayern’s defensive performance was perhaps Nagelsmann’s most significant shortcoming.

Die Roten conceded 1.25 xGA per 90 with 1.03 goals conceded per 90.

Given the dominance expected from Bayern, these metrics are not good enough.

Considering his work with Chelsea, Tuchel’s style of play is expected to restore some security at the back, and once again, this will be done through flexibility.

Bayern consistently defended in a 5-3-2 this season, with a PPDA of 8.35.

Tuchel, on the other hand, maintained a PPDA of 9.22 in 2021/22.

In the 2020/21 Champions League, Chelsea’s PPDA finished at 12.22.

Whereas Nagelsmann is more aggressive without the ball, Tuchel is happy to defend deeper if needed.

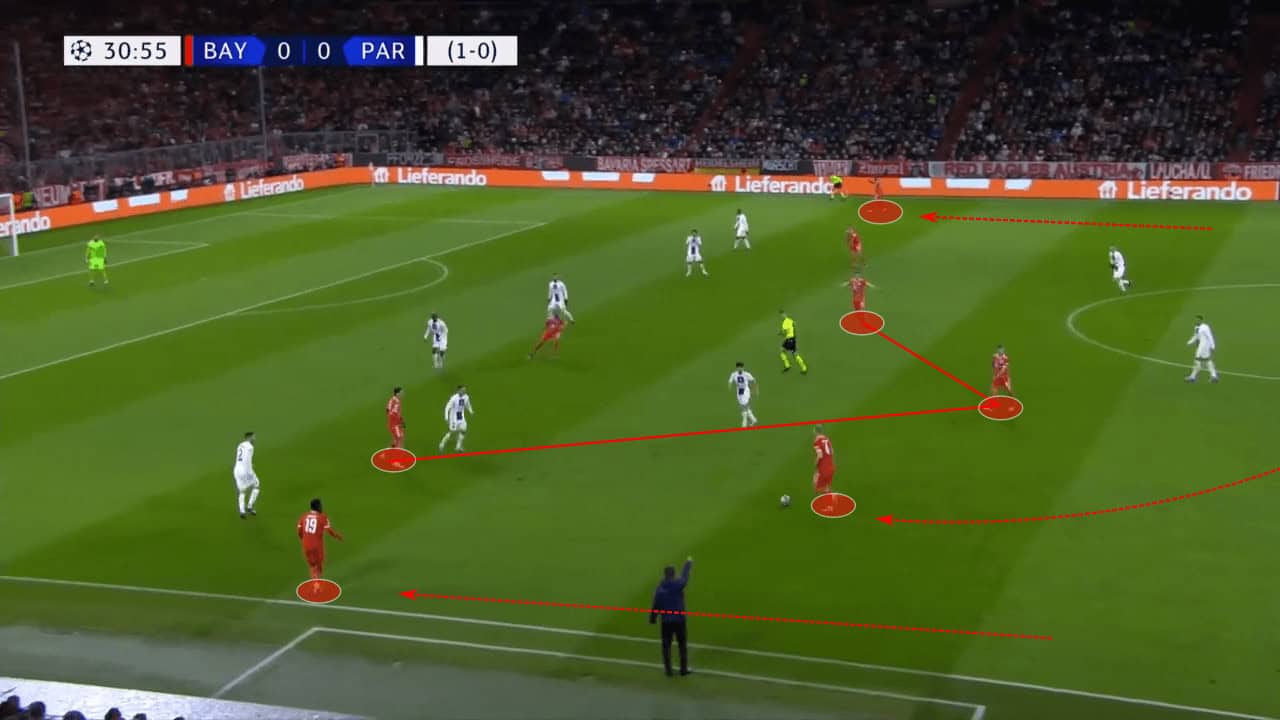

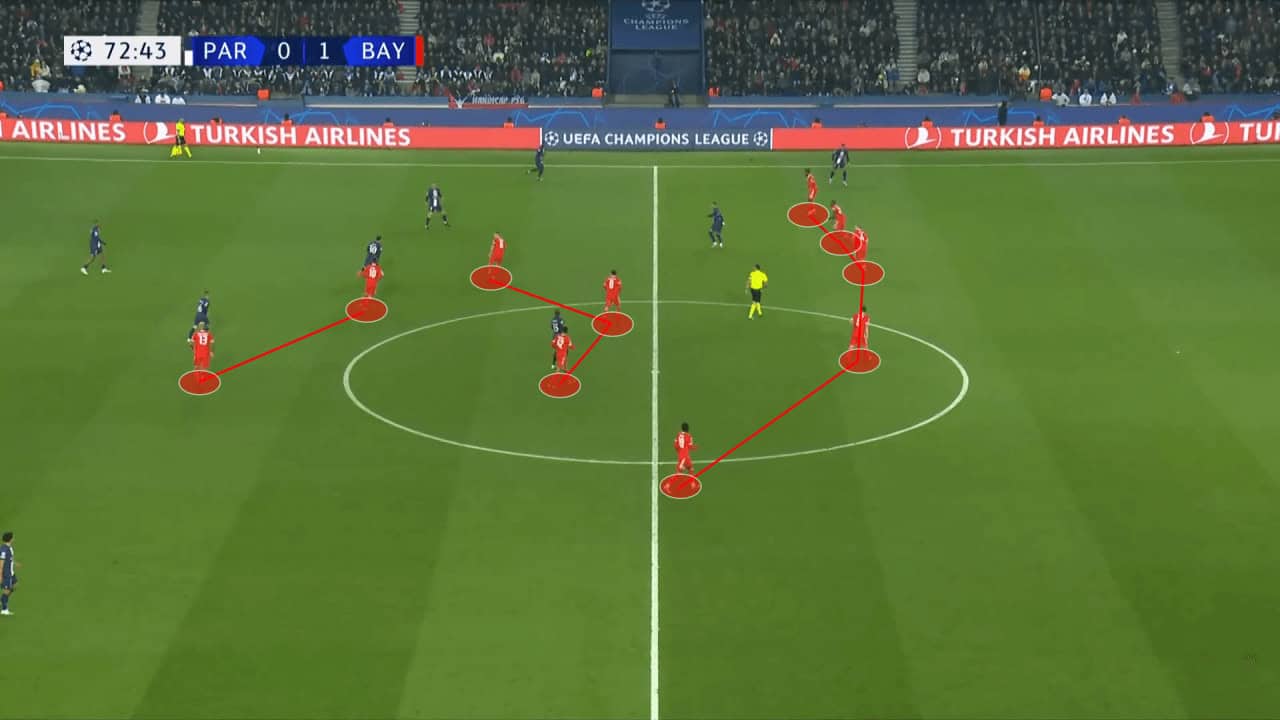

Against PSG, Bayern were required to defend more often, and their defensive organisation can be illustrated below.

While Bayern consistently defended in a 5-3-2, Chelsea were incredibly flexible with their defensive organisation.

Assigning formations to their defensive structure would be pointless, as it changed within seconds.

The Blues could switch between a back three and a back four seamlessly.

Again, their structure constantly depended on the opponents.

While this may look like chaos, the opposition analysis and preparation were extensive, as each player clearly knew where and whom to mark.

Of course, there was an initial organisation to build from.

The 5-2-3 was common, although it could easily become a 4-3-3, 5-4-1, or 4-5-1—the options are endless.

The front three was the same one from their organisation in possession, and the nearest two attackers would press their respective sides while the other tucked in to complement the midfield.

The mobility of the two advanced midfielders alongside the two defensive midfielders meant they could quickly go from pressing high up the pitch to compacting the midfield.

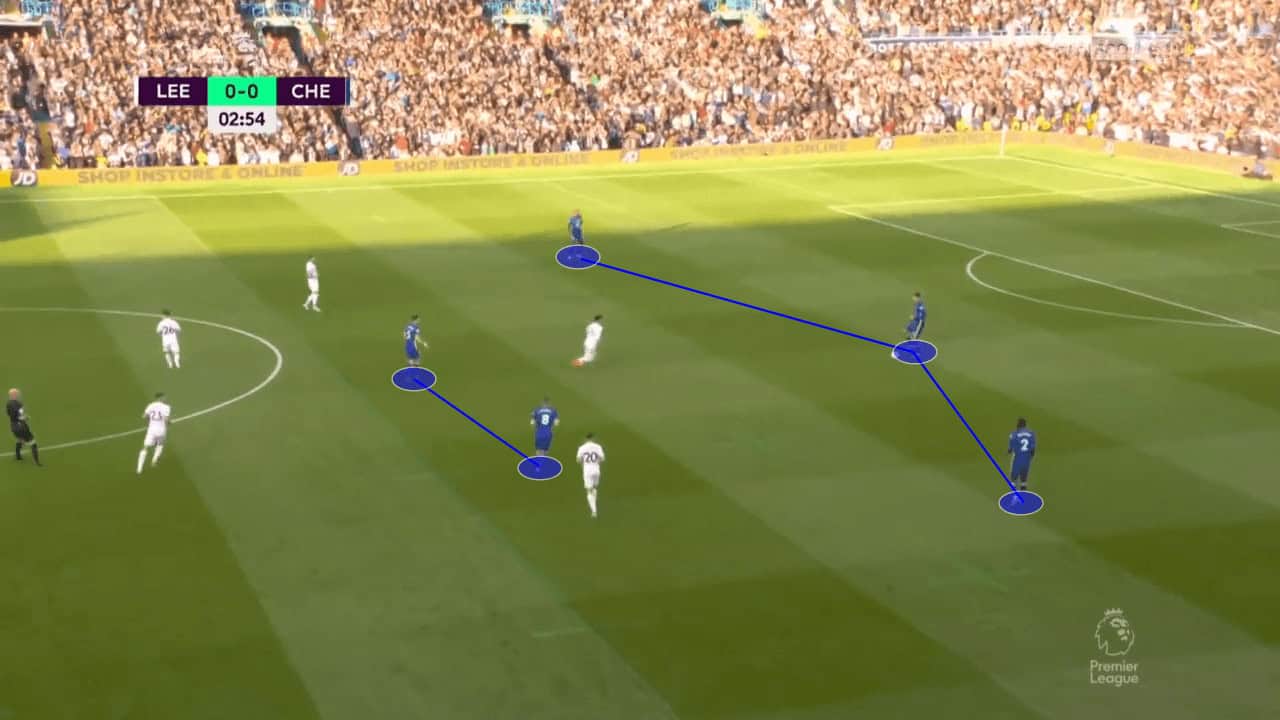

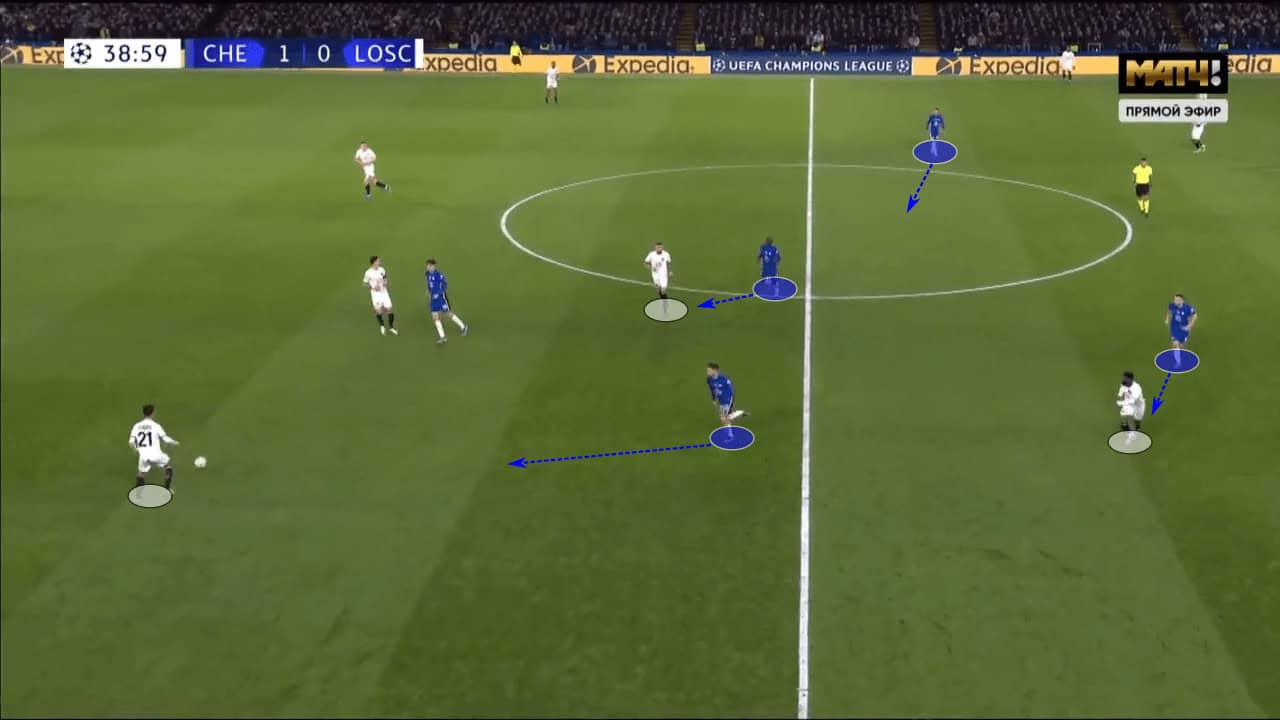

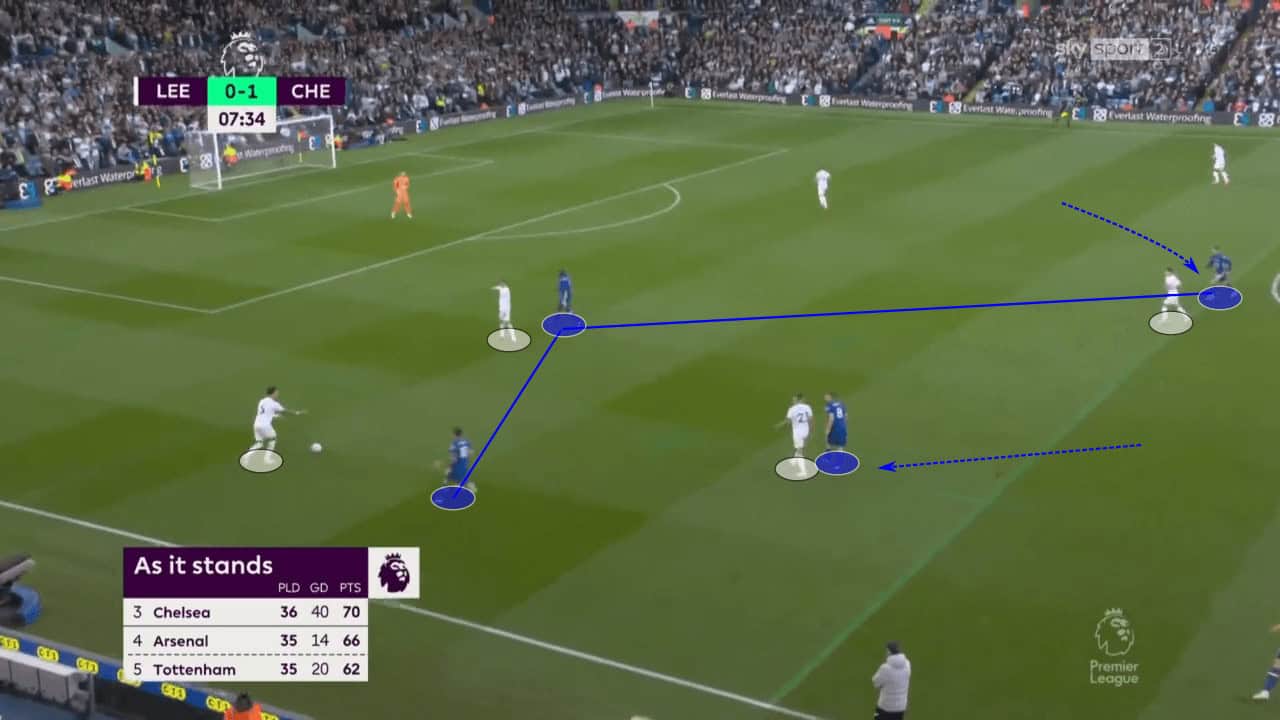

This pattern can be identified in their pressing structure, highlighted below.

The front two pressed Leeds’ left side while the opposite attacker dropped into the midfield.

The deeper midfielders could easily jump forward to pick up options, as illustrated below.

Note how every player has a clear man to mark.

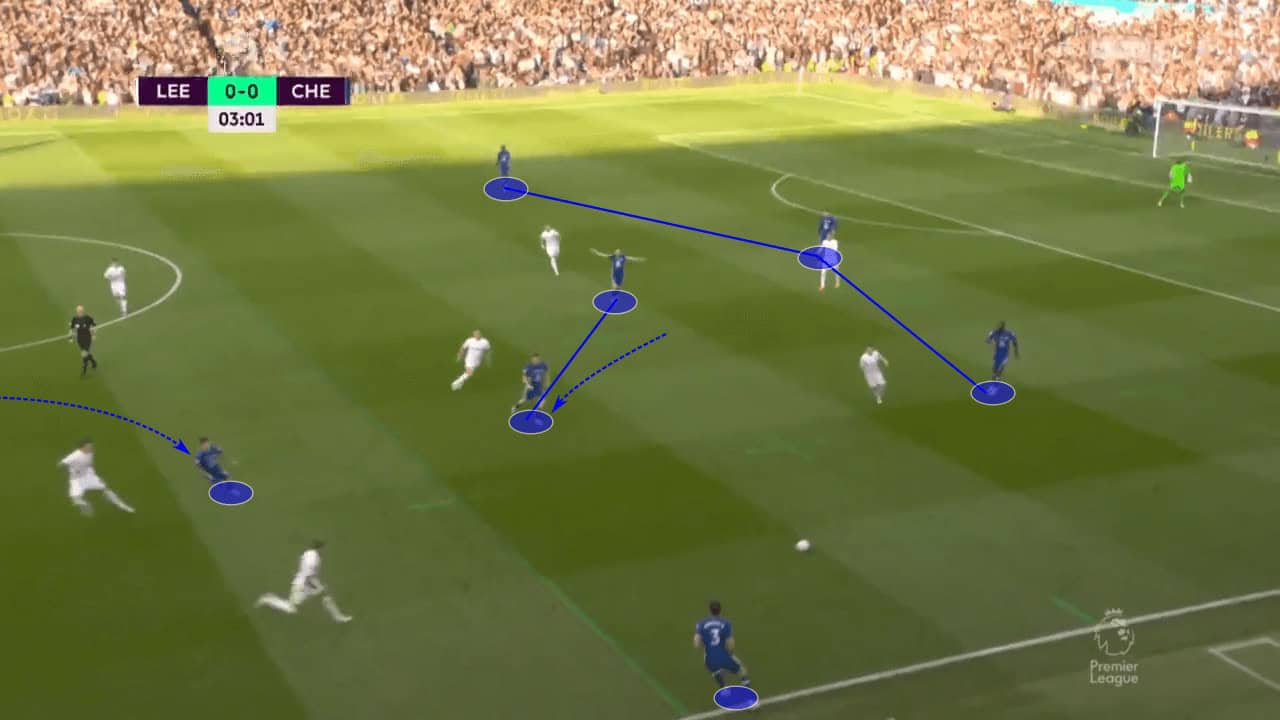

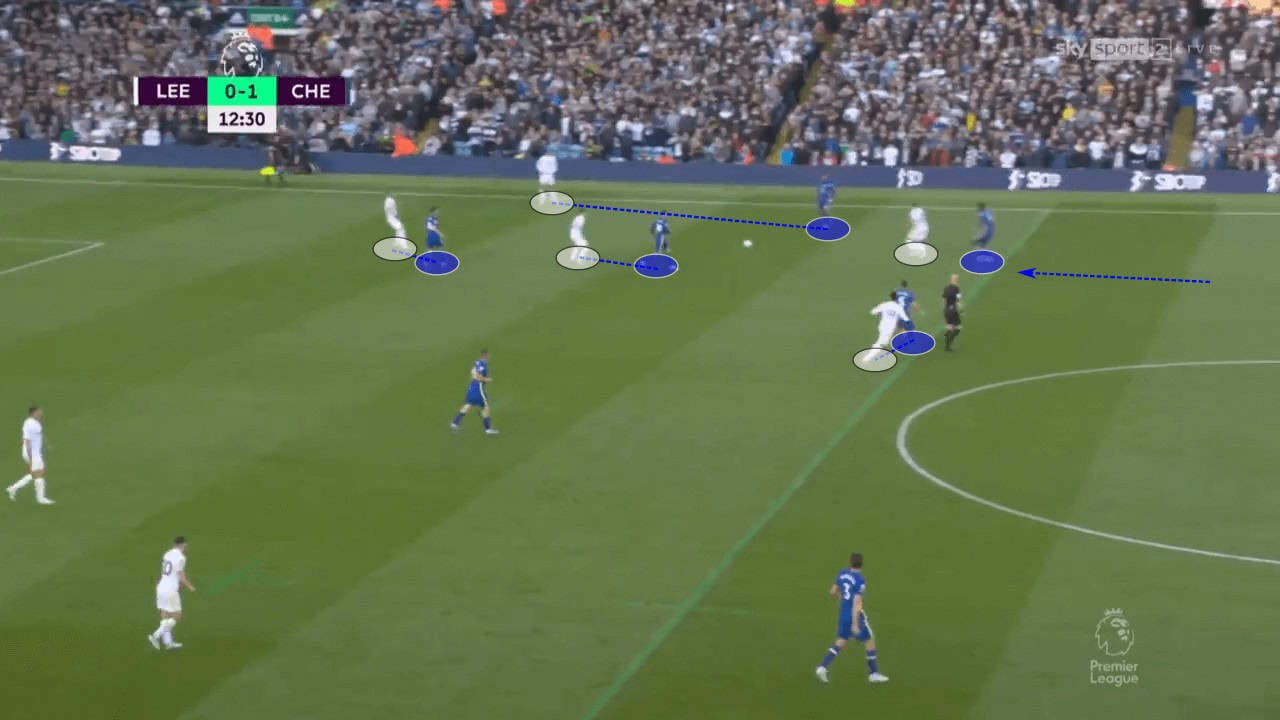

A few minutes later, we can see another example of this on the other side of the pitch.

This time, one of the centre-backs has pushed up the pitch to pick up a player.

The relevant two forwards were wide-pressing alongside the wide player.

The deeper midfielders both pushed up.

Once again, everyone has a clear man.

Tuchel’s ability to extensively prepare for the opposition and clearly instruct his players is exceptional.

Tuchel will bring a much more extensive approach to the defensive side of the game, something Bayern desperately needs.

His flexibility will not only be refreshing but vital in the latter stages of the Champions League.

Conclusion

With the controversial decision to sack one of the world’s most promising managers, Die Roten are not looking back.

The gamble on Thomas Tuchel’s manager style is significant – financially and competitively.

While Tuchel’s tactics could bring glory by winning the Champions League and the Bundesliga, Bayern could finish the season with nothing.

Regardless, the managerial transition has a fascinating tactical dimension, and it will be interesting to follow Tuchel’s style of play with Bayern Munich.

Comments