It was an eyebrow-raising decision for Bayern Munich to relieve the highly-rated Julian Nagelsmann from his duties following a 2-1 defeat to Xabi Alonso’s Bayern Leverkusen.

The loss dropped the Bundesliga champions down to second in the table as bitter rivals Borussia Dortmund moved to the top and were on an incredible run of form.

Bayern’s board didn’t want to risk allowing the eleventh-straight league title to slip from their grasp.

They pulled the plug on Nagelsmann’s time at the club despite still being in the quarter-finals of both the UEFA Champions League and the DFB-Pokal.

Thomas Tuchel was tasked with potentially overseeing a solid end to the campaign.

The team put all its eggs in one basket, hoping that the German coach would pull off a feat similar to that he achieved with Chelsea two years prior.

Unfortunately, the eggs have already fallen out of the basket.

While Bayern are back at the top of the Bundesliga—although only by two points—the European giants have been eliminated from the Champions League and the DFB-Pokal.

In fact, Tuchel’s first six games have not gone as well as many expected, winning just two while exiting two competitions.

This Thomas Tuchel tactical analysis

will examine the tactics that Tuchel has been using at the Allianz Arena since his appointment and analyze the different ways that Die Bayern can improve before the season ends.

Thomas Tuchel Tactics – Tweaks in build-up

Throughout his managerial career, Nagelsmann’s coaching style earned a reputation for being somewhat of a chameleon when it came to choosing formations.

During his time with Hoffenheim and RB Leipzig, it was difficult to predict what kind of set-up the promising, young coach would use on any given day.

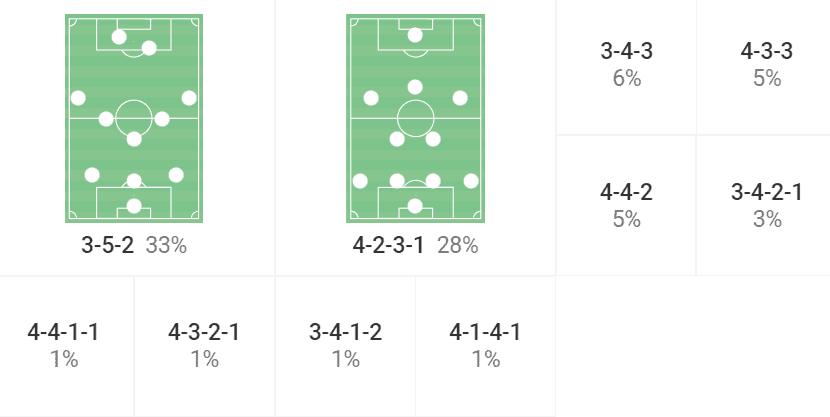

This data viz highlights Leipzig’s preferred formations from the 2020/21 season.

His preferred structure was the 3-5-2 formation, but Die Roten was also no strangers to the 4-2-3-1, the 4-4-2, the 4-3-3, and other variations of a back three.

In this respect, Nagelsmann and Graham Potter were compared, as both are proponents of principles rather than formations.

However, once he became the head coach of Bayern Munich, this characteristic was lost a little.

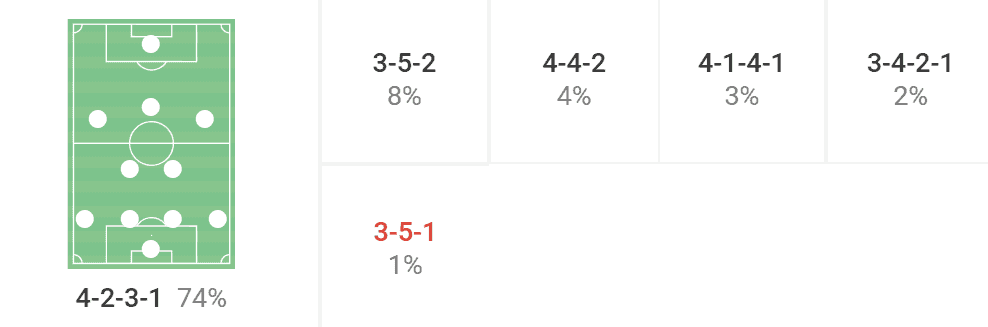

Nagelsmann became an advocate for the 4-2-3-1, and while the manager still believed that principles trump formations, it became much easier to predict his tactical set-up in games.

Perhaps this is a result of having better players, and so Bayern did not have to bend to the will of opponents as much as teams like RB Leipzig and Hoffenheim, but it’s still an interesting detail to note.

Once Tuchel arrived in Munich, he didn’t hesitate to use the 4-2-3-1 formation that the players were accustomed to under his predecessor.

This season, the conventional formation has been used more than any others under the two managers by quite a large margin.

Many believed that Tuchel’s formation might switch to the 3-4-2-1 as he did at Chelsea, which saw the Blues lift the Champions League just a few months into his reign.

This didn’t happen, especially out of possession, but there have been some similarities on the ball compared to his time at Stamford Bridge.

There was some deviation from the build-up structure used by Nagelsmann.

They preferred to build out with a 3-1 base under Tuchel’s predecessor.

Joshua Kimmich and Benjamin Pavard were pivotal to this.

Pavard has experience playing in the centre and isn’t a natural fullback compared to a player like Alphonso Davies.

Nagelsmann liked the Frenchman to tuck inside, creating a back three in possession and giving Davies license to get forward on the left.

Meanwhile, Kimmich operated as the single pivot while his partner pushed up behind the opposition’s midfield line.

Typically, Bayern’s shape in the attacking phase was a 3-1-5-1.

The fewer bodies deeper down the pitch, the more passing angles could be created to progress the ball forward.

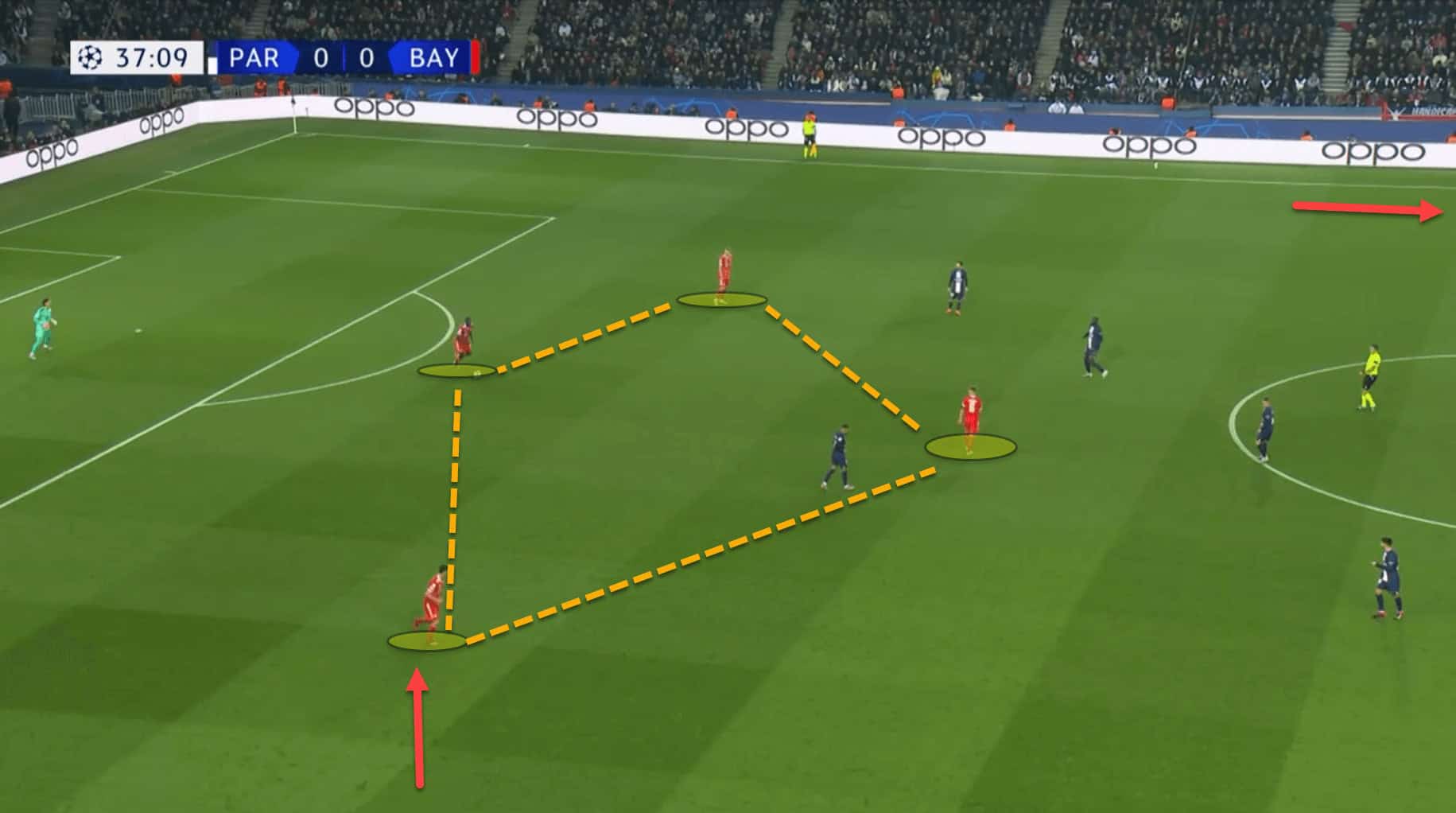

Thomas Tuchel’s coaching style built on this slightly.

Bayern have an extra man down the pitch now, as the former PSG boss values having enough security in the deeper areas to break the press.

In essence, if the ball can’t reach the attacking players, having more bodies up the field is worthless.

Instead of a 3+1, Thomas Tuchel’s style of play prefers a 3+2, which allows for extra passing options. This means that, in theory, it is safer to pass around from the back and into midfield.

Another reason the European champion prefers to do this is that there is another player back during transitions in case possession is turned over.

The 3+1 was problematic under Nagelsmann quite often because Die Bayern were caught out on the break far too often, with only one player in front of the backline protecting the space.

Bayern were incredibly open to being hit by rapid and direct counterattacks during Nagelsmann’s reign.

This was a constant criticism of the young head coach throughout his tenure at the Allianz Arena.

Opposition teams knew that they could sit in a compact mid-block and patiently wait for one of Bayern’s trio in the first line or Kimmich to make a misjudged pass or touch so that they could then capitalise on the error and spring forward in transition.

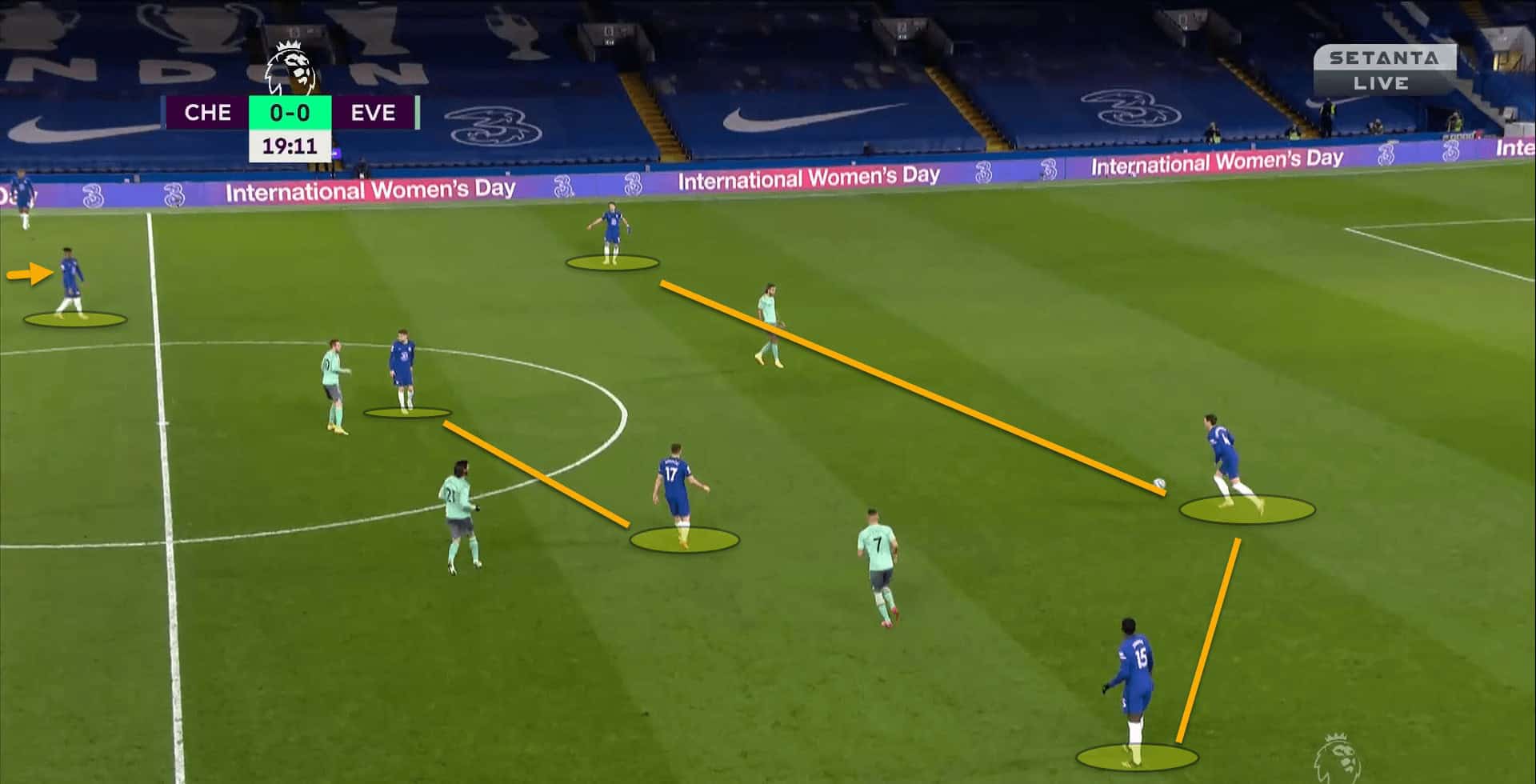

The change to a 3+2 in the build-up was the same structure he used at Chelsea with great success two years ago.

The only difference was that the Blues started with a 3-4-2-1 base formation anyway, which facilitated this more easily than a 4-2-3-1.

Another similarity from his time in charge of the Blues was how he used his last line to create passing angles behind the opposition’s midfield to ensure that they had a numerical overload in the middle of the park.

In Chelsea’s 3-4-2-1, the two wingers acted as double ‘10s’ or wide playmakers who would drop deep to offer progressive passing options to move forward up the pitch, generally through the halfspaces.

Sometimes, centre-forward Kai Havertz would do the same if one of the wingers was running in behind or pinning a defender back.

At Bayern, the new manager is implementing this structure to create overloads against the opposition’s midfield.

Bayern’s build-up play in this tweaked shape under Thomas Tuchel’s tactics has been slightly problematic, particularly with Pavard on the right.

The World Cup winner is not a player who is overly comfortable opening his body up when receiving laterally or from a back pass.

The 27-year-old has been a trigger for teams to step up when pressing, forcing Bayern to play all the way back to Yann Sommer in net as he is unable to turn out and play a pass, which breaks the press.

To conclude this section, the sample size is quite small, but Tuchel’s formation change to the 3+2 may not have had the desired effect on the team’s ability to become more secure when possession is turned over in the deeper areas.

In his six games so far, Bayern have conceded ten goals, three of which came directly from errors when passing out from the back—one against Borussia Dortmund and two versus Manchester City across both legs of the UCL quarter-final.

The new head coach still has a lot of work to do in this highly transitional league.

thomas tuchel style of play – Very positional with a lack of efficiency

Just like his time with Borussia Dortmund, PSG and Chelsea, Thomas Tuchel manager style has adopted a positional play style of football, the same method used by Nagelsmann and so the transition from one coach to the other has been relatively seamless in that respect.

While Tuchel may be a little more concerned about balance and defensive stability than his predecessor, the principles have essentially remained the same.

Continuing on the topic of Bayern’s 3+2 build-up shape with the three defenders and a double pivot, one benefit of this scheme is that it frees up the wide players.

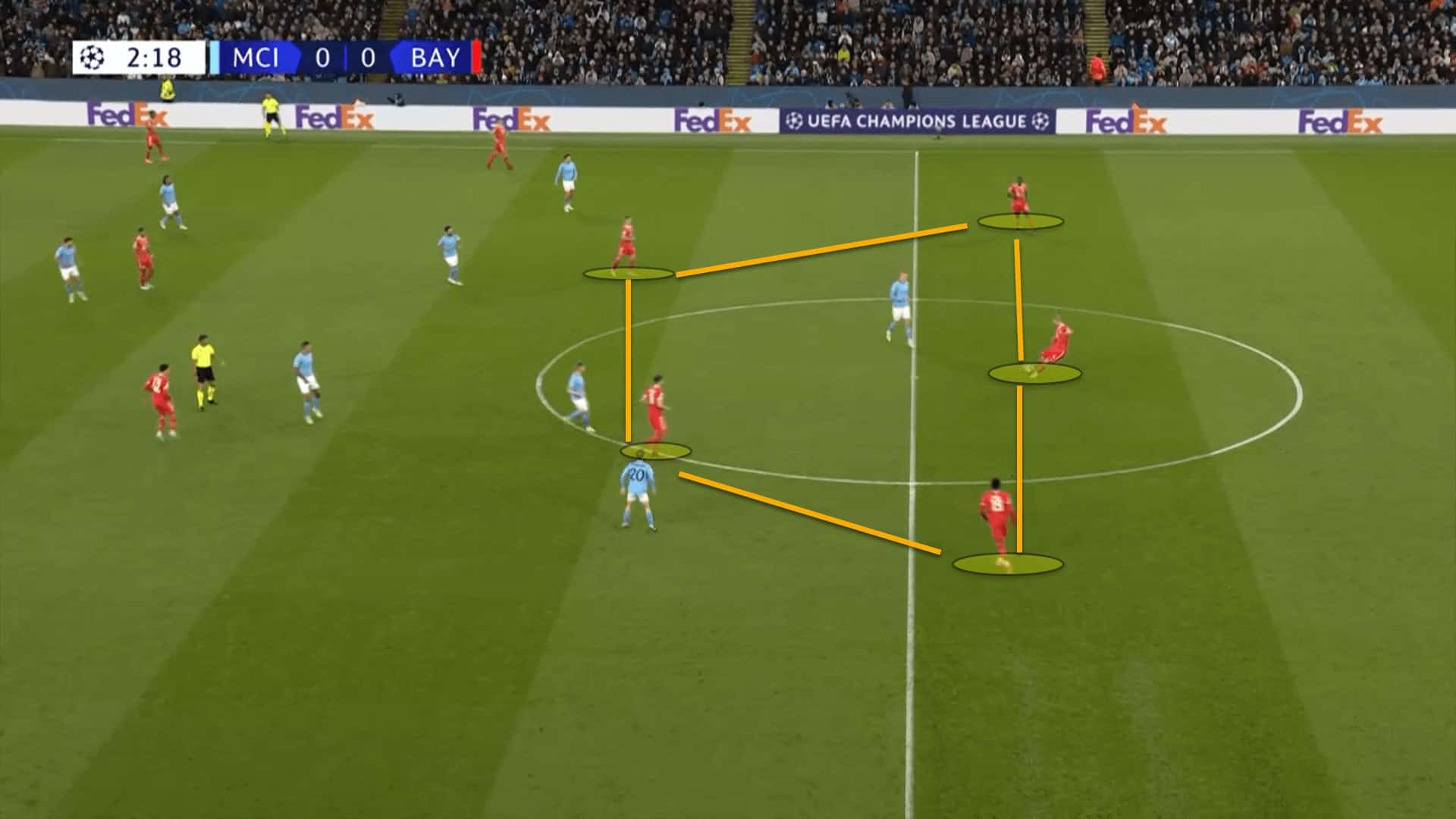

Manchester City have utilised this really well this season in their 3-2-2-3/3-2-5 in-possession structure.

Having the double pivot and three defenders so close together narrows the opposition’s midfield and forward line when pressing, leaving the flanks open for the wingers to receive and engage in 1v1 situations with the opponent’s fullback.

It makes sense for Tuchel to take this approach with Bayern.

The Bundesliga champions possess unbelievable quality on the flanks, with players such as Kingsley Coman, Serge Gnabry, and Leroy Sané.

Getting these players into 1v1 scenarios and squaring up the opposition’s fullback can be deadly.

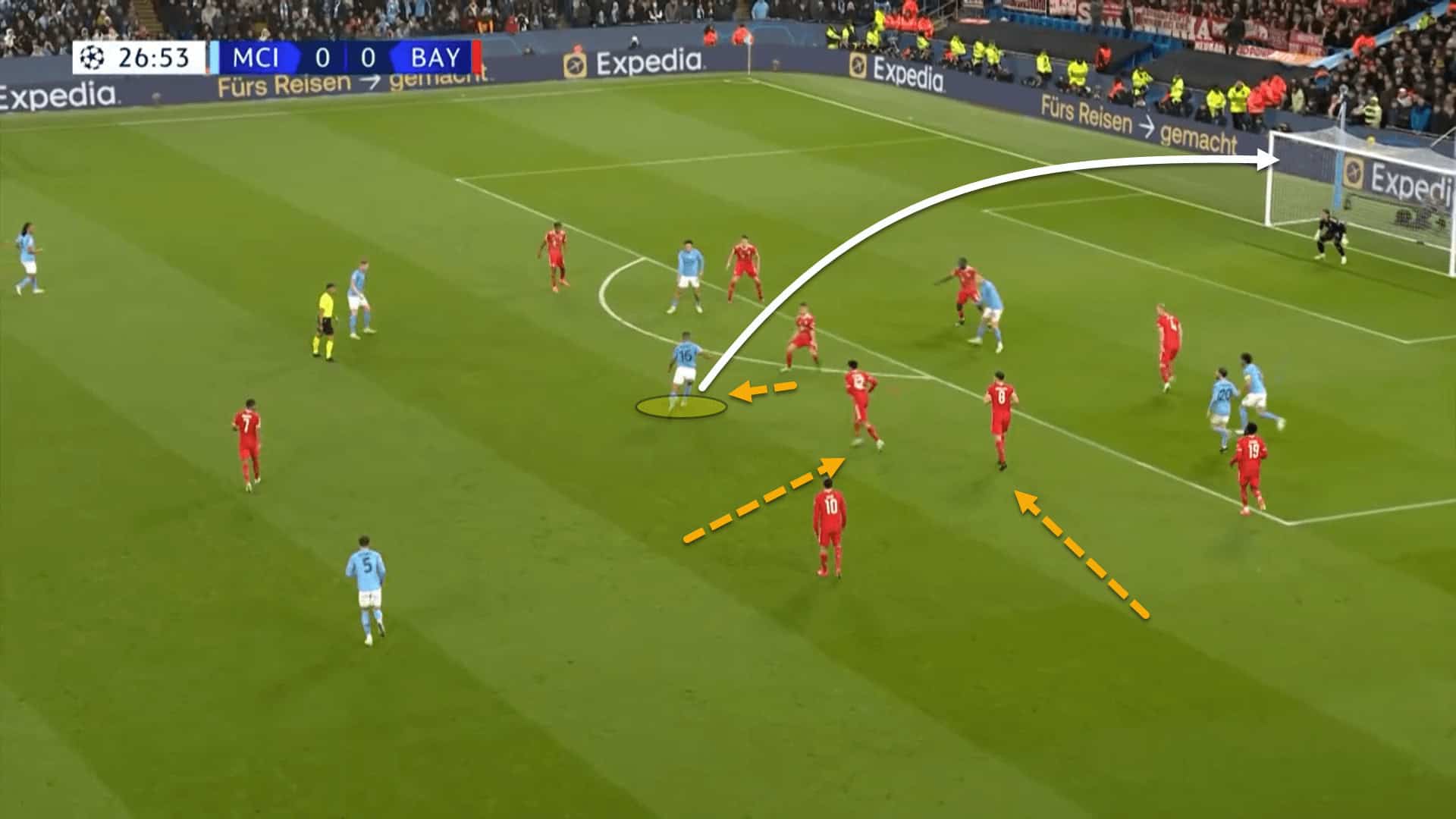

Here, City’s press was narrow due to the 3+2 structure being used by Bayern.

Pressing in a 4-4-2, left winger Jack Grealish was invertedly applying pressure to Pavard while right winger Bernardo Silva was tucking inside for balance.

This left both Coman and Sane in individual battles with City’s widest defenders.

Often, the right winger is high and wide a lot more than his partner over the other side.

This is because right-back Pavard tucks inside to create a three-man first line, while on the left, the left-back is advanced and so the left-winger can come in-field.

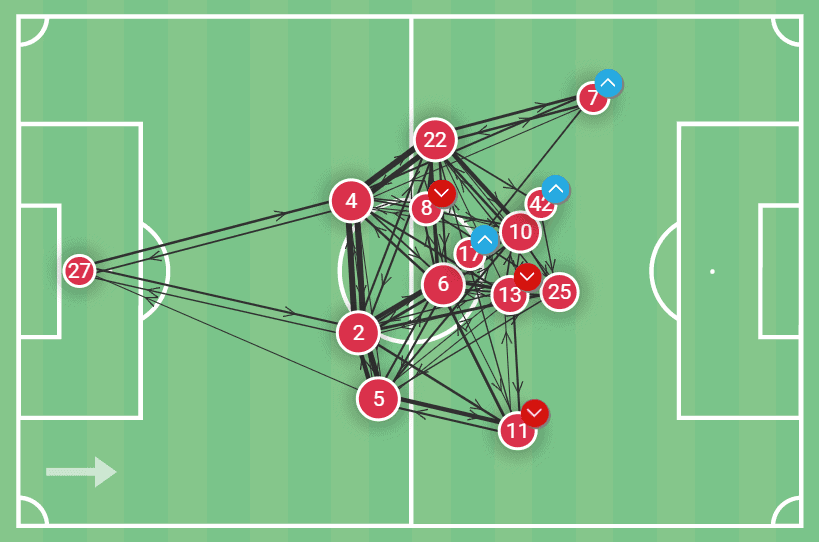

This pass map from Bayern’s DFB-Pokal quarter-final with Freiburg really well displays the team’s overall possession set-up.

Pavard (5) is positioned like a centre-back, while João Cancelo (22) is further forward on the other flank.

As a result, Sané (10) can push into the central channels while Coman (11) sticks to the sideline on the right to compensate for Pavard’s lack of width.

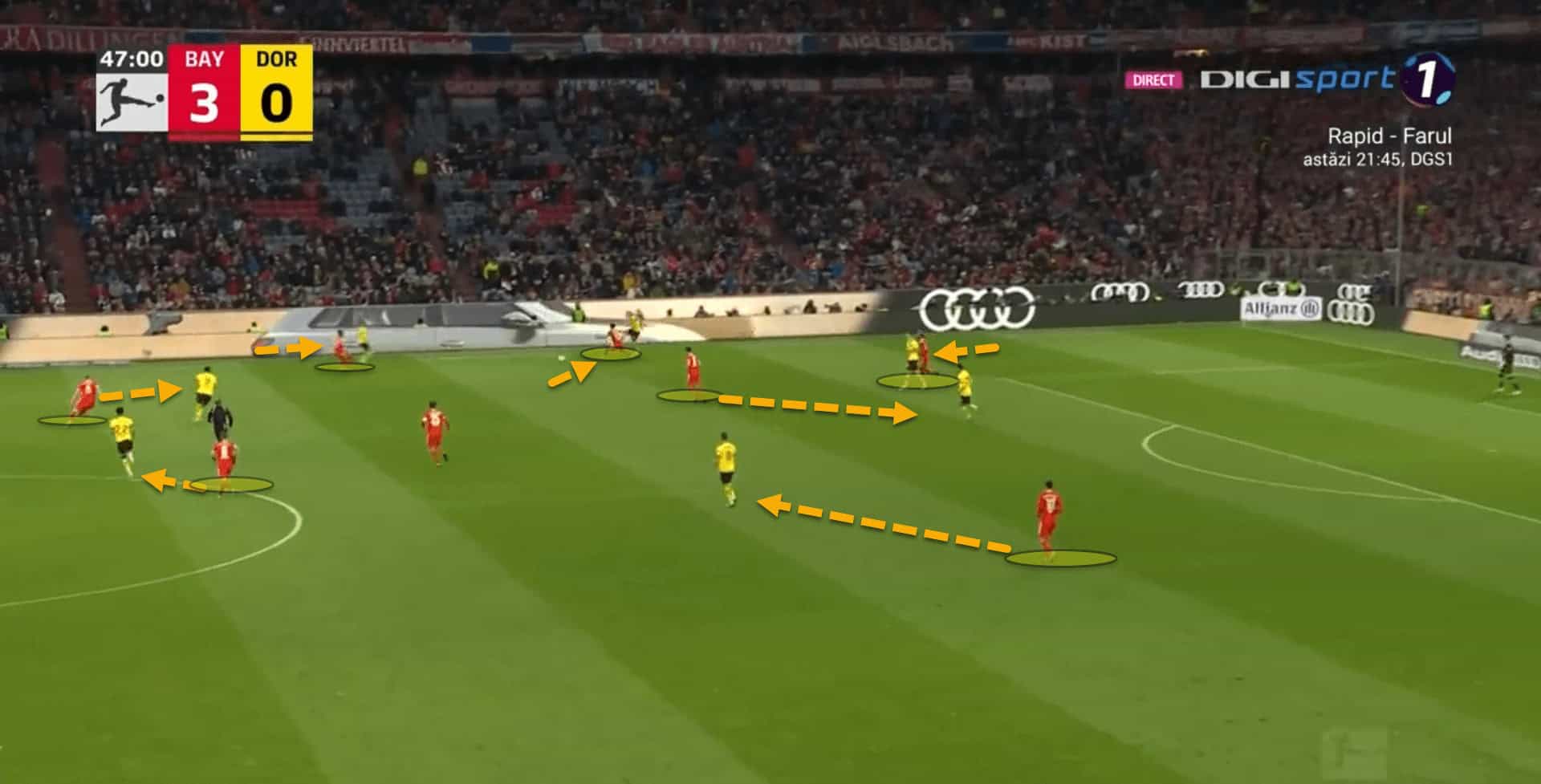

Tuchel’s team, like under Nagelsmann before him, also generated space by pinning the opposition’s backline, which creates space for runners to attack into.

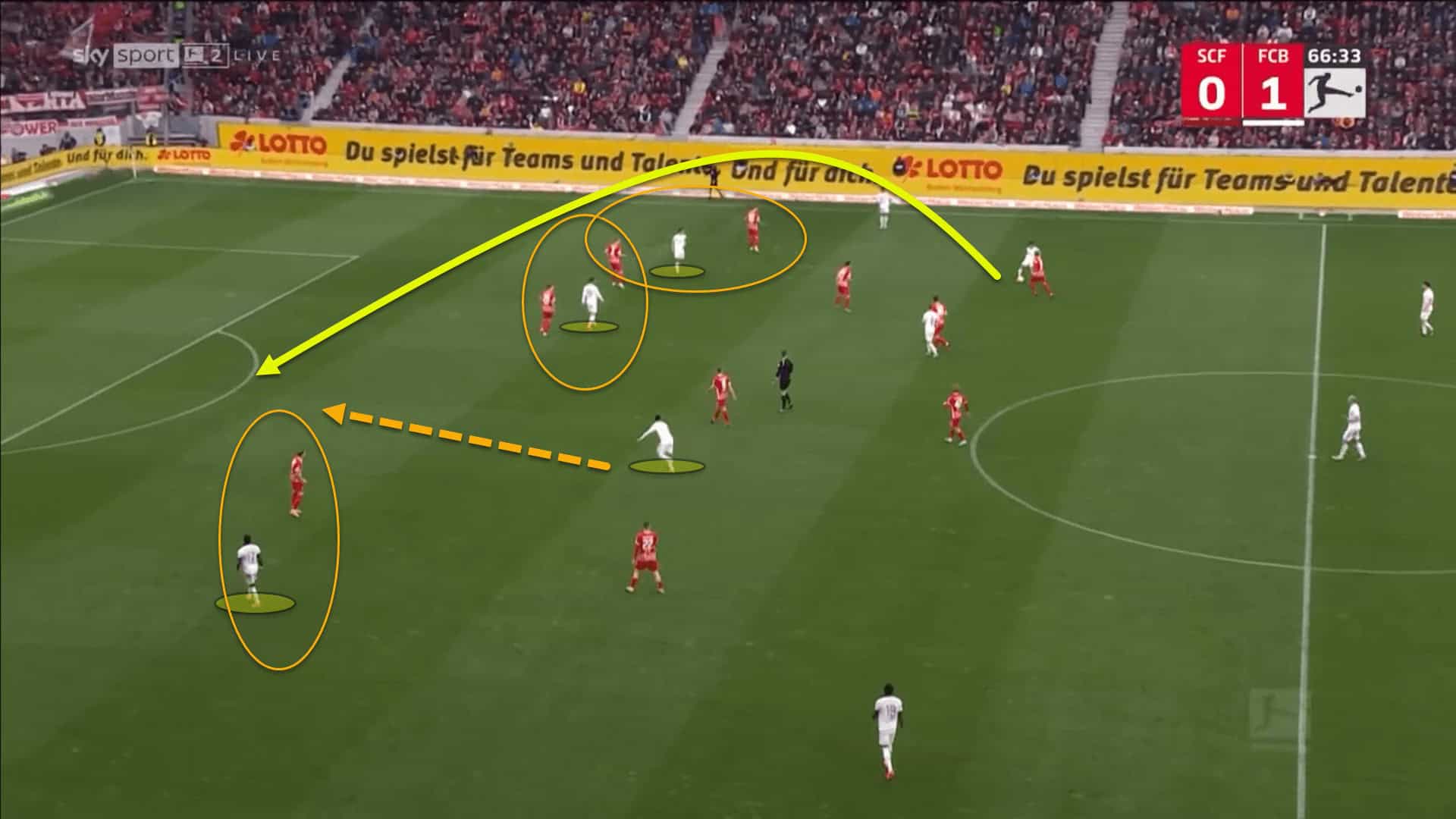

Here, Freiburg were defending in a 4-4-2 mid-to-low block.

Bayern had pinned back the entire back four using three players by positioning them in each channel.

This caused a gap to open between Freiburg’s right-back and right central defender.

Spotting the space, Jamal Musiala made a run from deep and was played in by Cancelo with a trademark banana ball from the outside of his boot.

Unfortunately, the German international couldn’t get it under control, and the chance went begging, but it was still a wonderful opportunity created by strict positional play.

Bayern have also used a lot of countermovements so far during Tuchel’s reign.

Because of the pinning system put in place, it can be pretty easy to generate countermovements by one player dropping deep, dragging a defender out of position, while the other runs in behind to get into a race to the box with a defender.

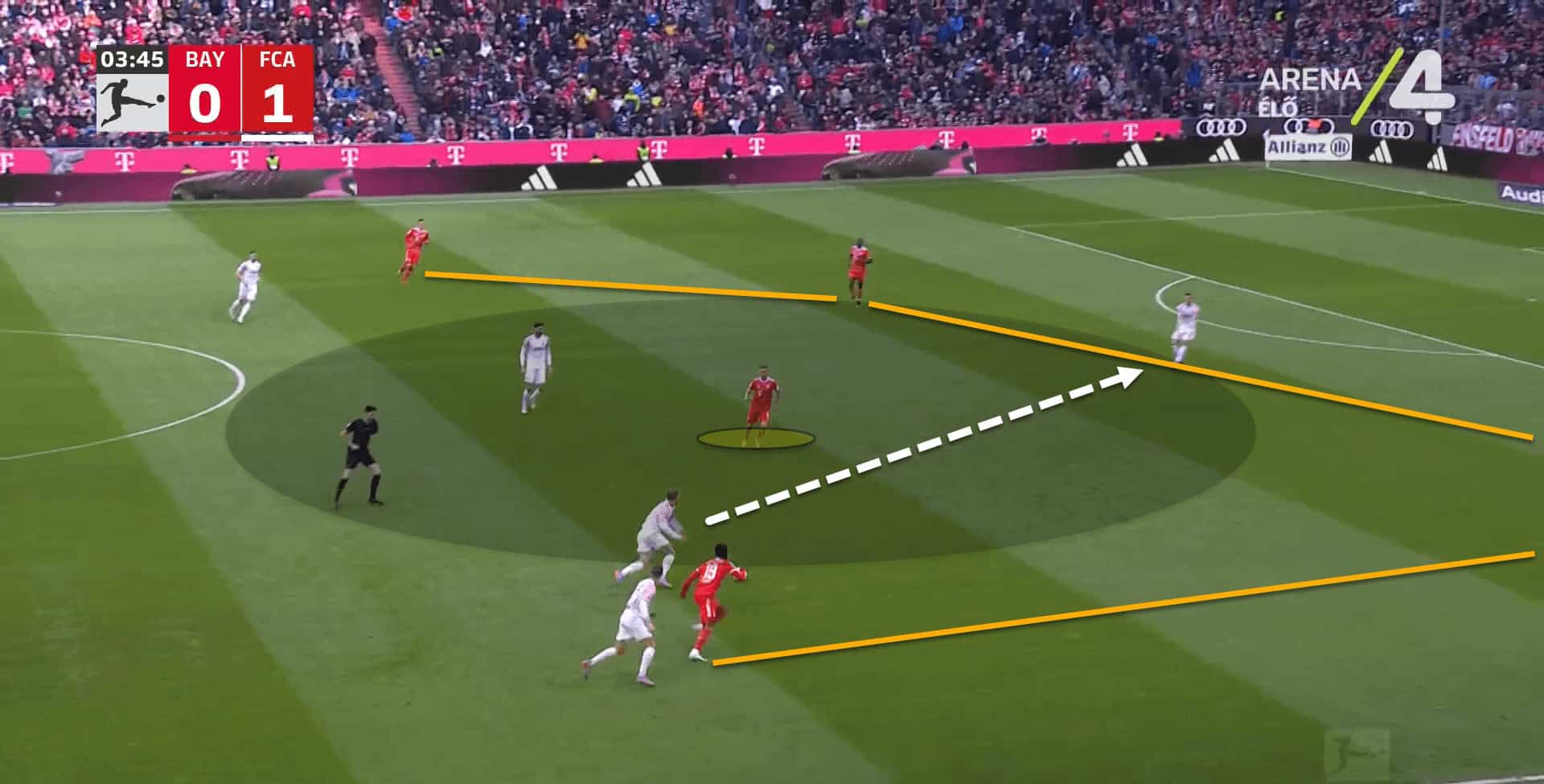

This is what happened here.

Gnabry came short, and Sané ran in behind.

The movement didn’t lead to a goal, but the threat was there, and very few players could catch Leroy Sané in a foot race.

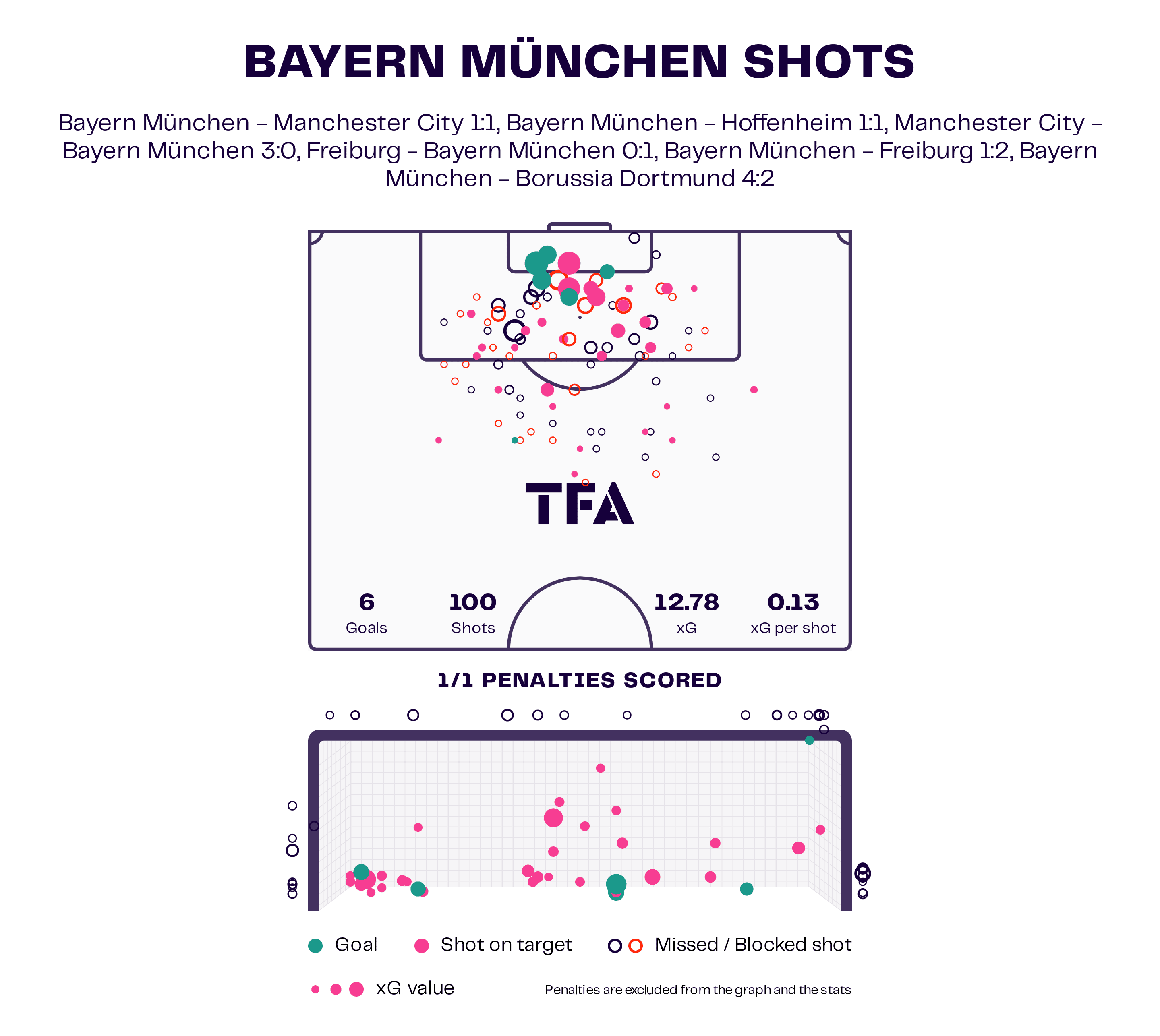

But actually, getting the ball into the net has proved difficult for the new manager.

Unfortunately, Tuchel seems to have brought the curse of his former club to the Allianz Arena with him.

It’s not a case of poor chance creation.

In fact, Bayern creates quite a few decent opportunities but is unable to hit the net consistently.

Of course, one of the main reasons behind this is the lack of a potent centre-forward since losing Robert Lewandowski to Barcelona in the summer.

And it is a shame for the new boss.

His record of two wins in six doesn’t look great, but with some cutting-edge in front of the net, they could have turned one or two of these disappointing results into wins.

Perhaps they’d still be on for a treble or at least a domestic double.

Bayern Munich Defensive tactics

One of the first things Tuchel improved when he took over at Chelsea back in 2021 was their defensive record.

During Lampard’s 19 Premier League games of the 2020/21 season, the Blues conceded 23 goals in total.

In the German’s first 10, just two goals flew into the Chelsea net while the side maintained eight clean sheets.

A similar situation needed to happen in Munich.

While Bayern hadn’t conceded as many as Chelsea, 10 goals against in 10 games under Nagelsmann was far from ideal for a team with aspirations of winning it all.

Unfortunately, Bayern’s record hasn’t completely been transformed in the same way since Tuchel took charge.

The Bavarian club have conceded ten goals in six matches.

History has not repeated itself.

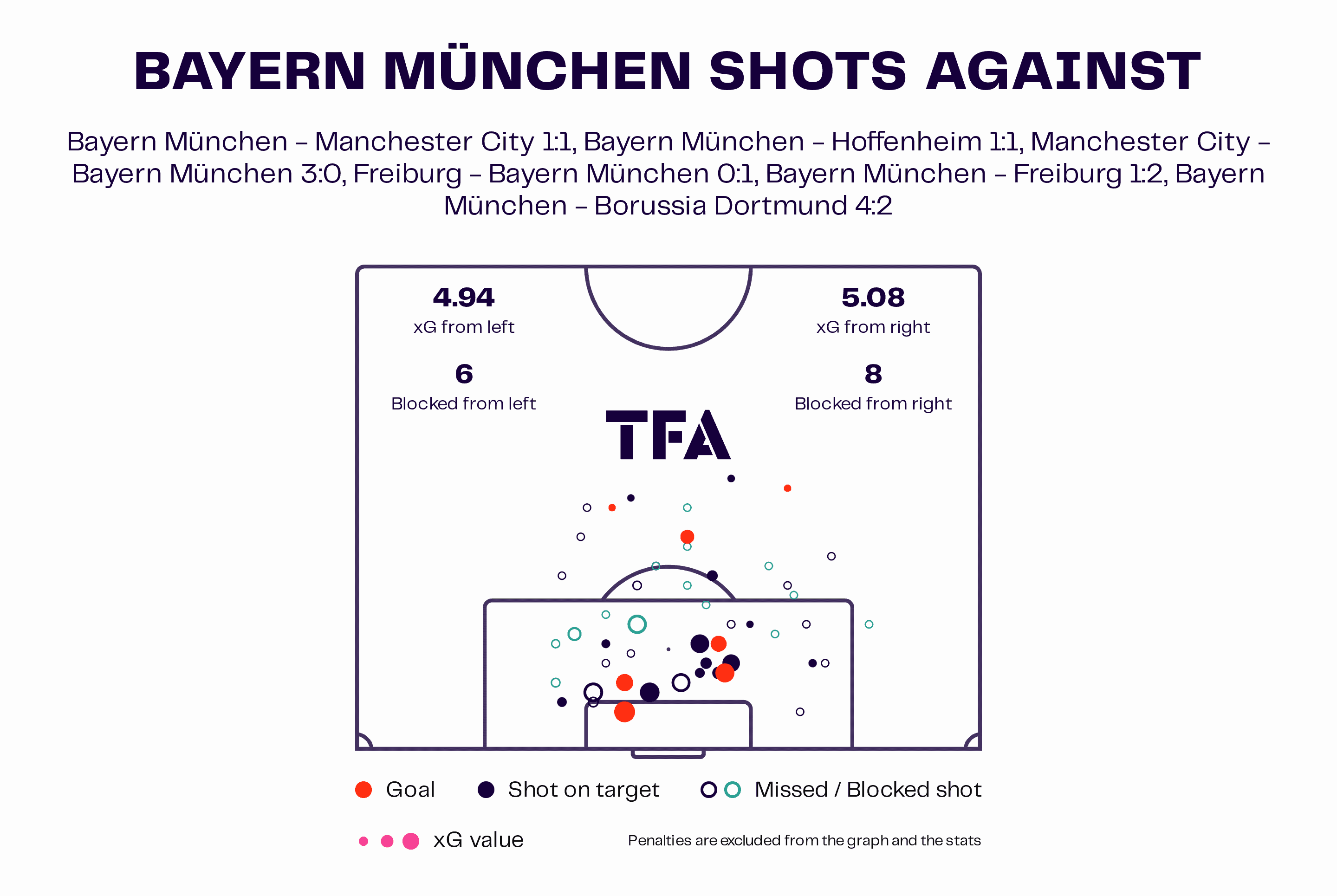

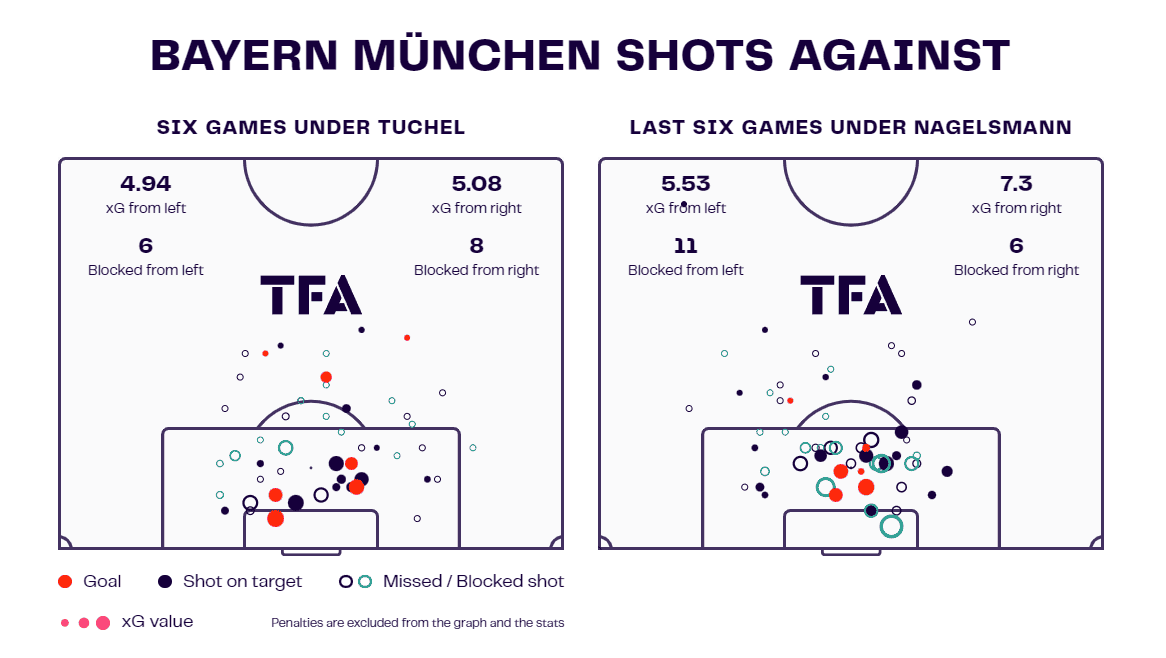

So far into his reign, Tuchel’s men have conceded an xG of 10.02, which is bang on the money regarding their defensive performance, having conceded ten goals in six matches.

However, an xGA of about one goal per game is far from ideal for an elite European side.

As aforementioned in the previous section, the Bundesliga champions are registering an average of 2.13 xG per game under Tuchel, and so are in a net positive for xG compared to xGA but have scored just 0.58 goals per game in contrast to one goal against – a net negative of –0.42.

What we can take from this is that Bayern are underperforming their expected goal difference so far during Tuchel’s brief tenure and potentially should be doing better than the results suggest.

Nevertheless, while the defensive improvement hasn’t really been as ideal as the board and Tuchel himself would have liked, there has still been a slight improvement compared to Nagelsmann’s final six games in charge.

Bayern were conceding an xG of 2.14 per game which is disastrous for a team fighting on all fronts.

A drop to 1.002 xGA per game still leaves room for improvement for the manager, but it is vastly better than before he took over.But now, let’s look at the out-of-possession tactical set-up that Tuchel has used so far in his reign.

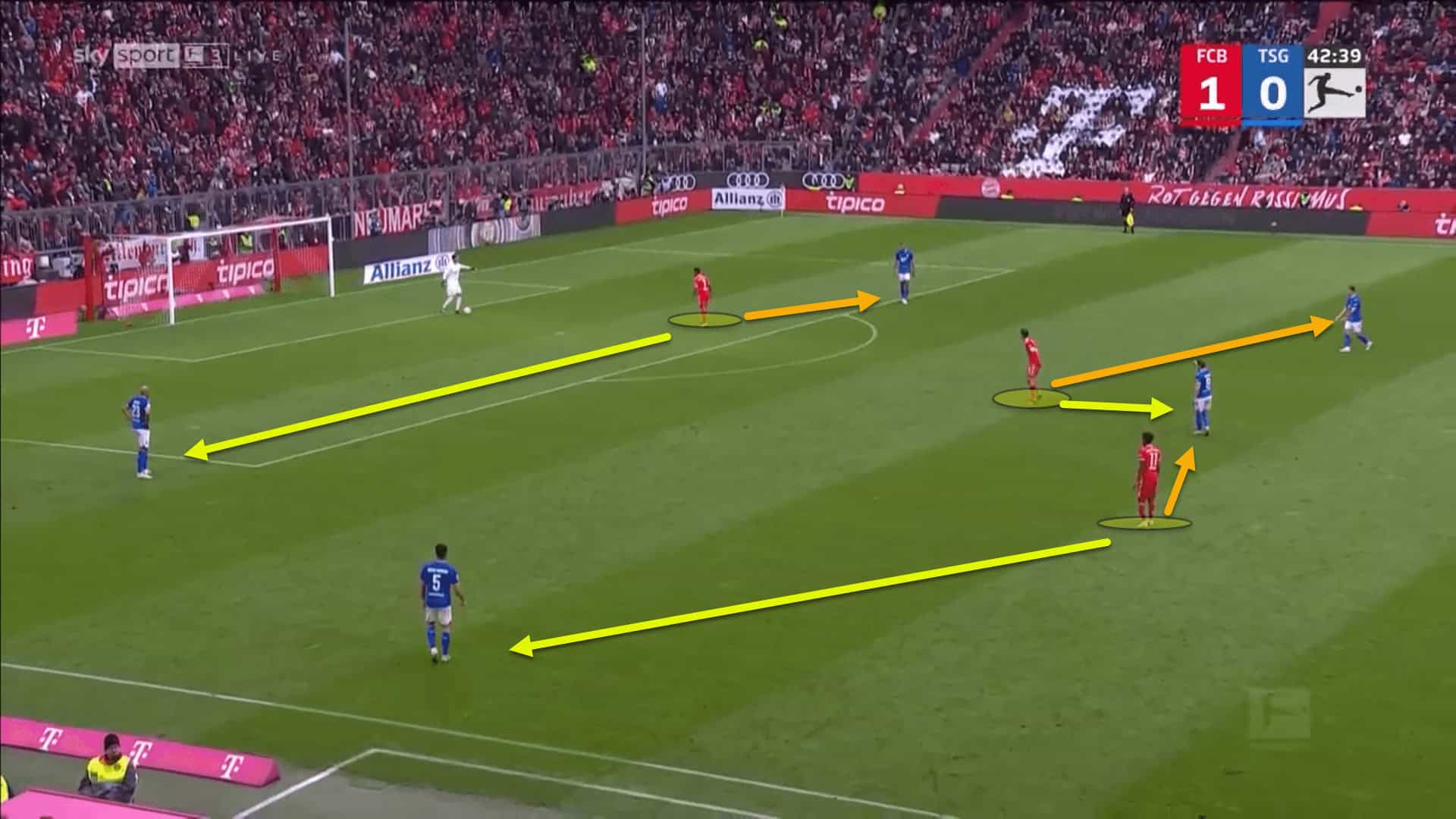

Bayern defends in a 4-2-3-1 formation.

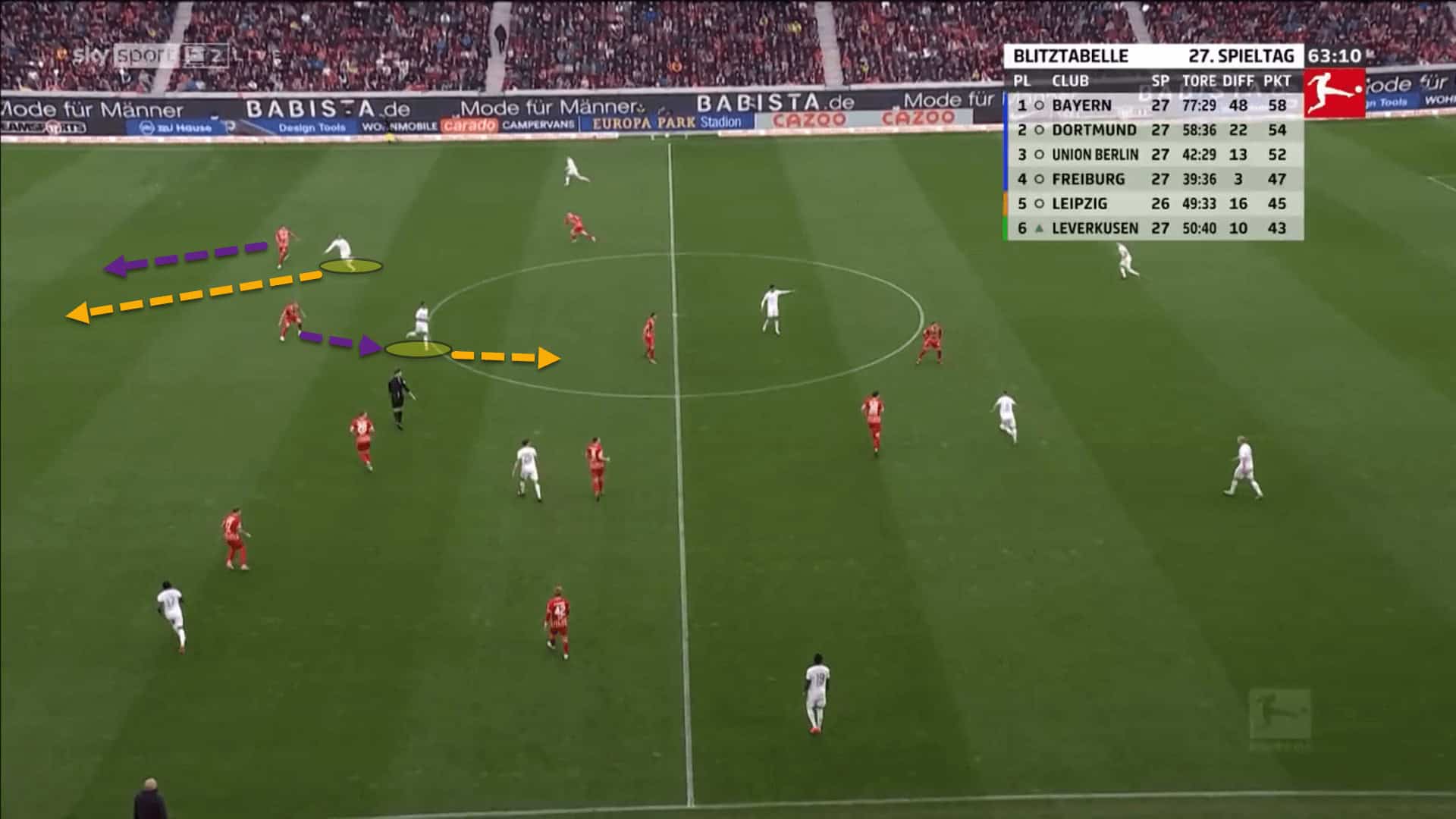

The manager wants his players to press zonally when the ball is in the central areas of the pitch.

This means that the players will stand between two opposition players, ready to drop onto one, depending on which side the ball goes.

This type of pressing scheme can also be labelled as situational pressing.

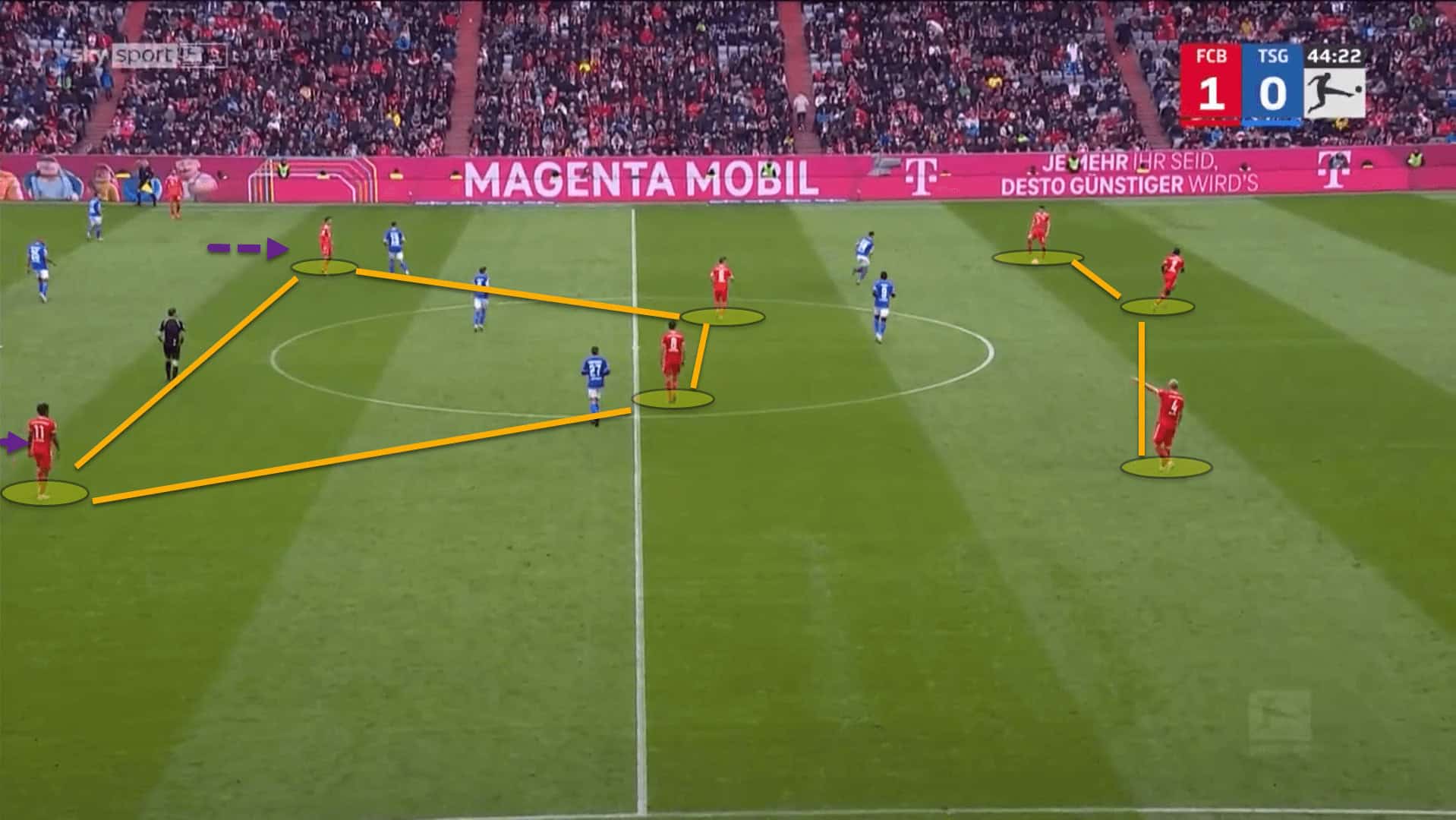

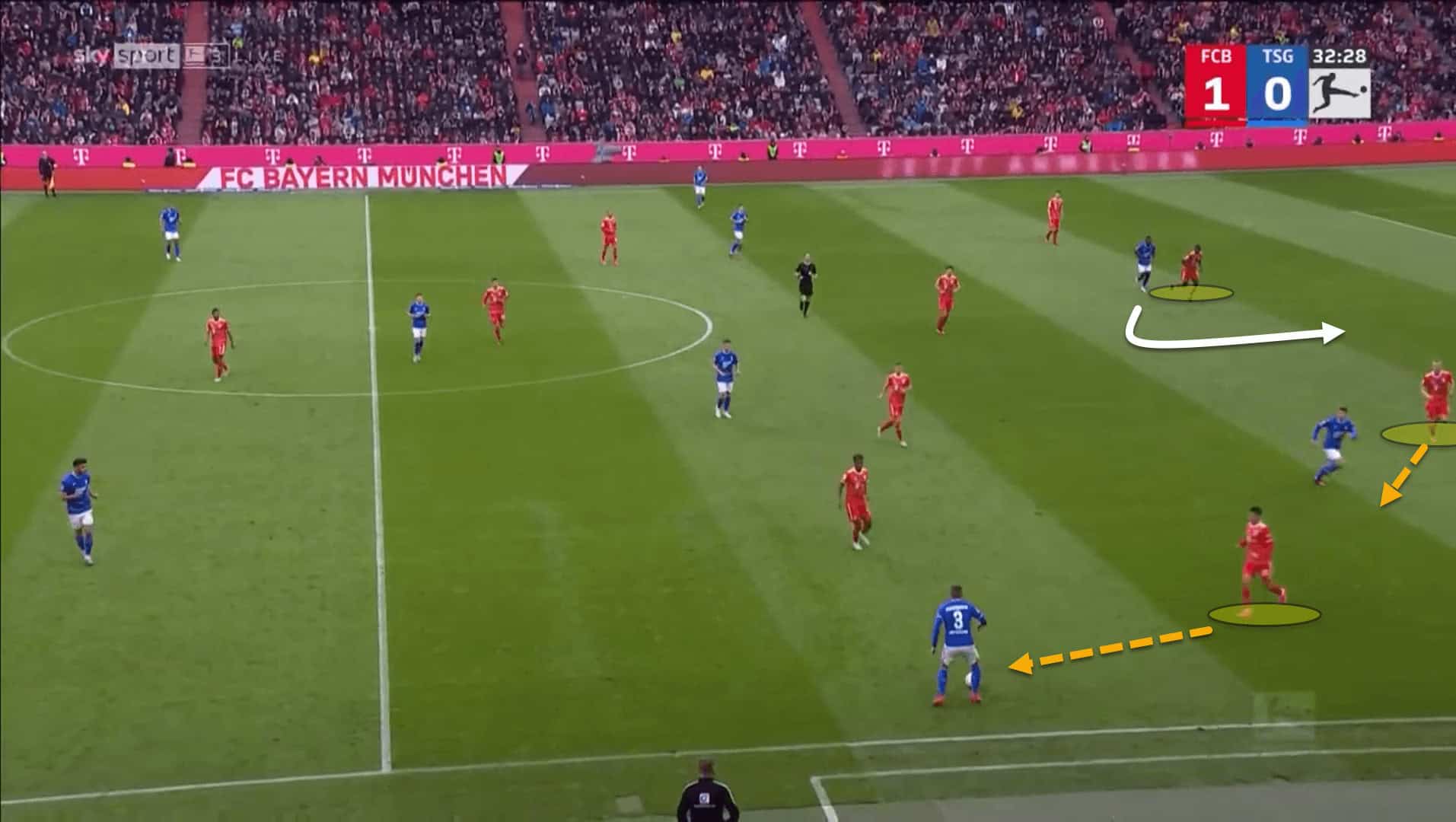

Here is an example of Bayern’s 4-2-3-1 pressing structure when the ball is positioned in the central spaces of the pitch.

The yellow arrows indicate which player they mark if the ball is played out to the left, while the orange arrows indicate which player is marked if the ball is played out to the right.

Each player is positioned between two Hoffenheim players and the player they mark in the press is decided by the side that the ball is played to.

But this is often directed by Bayern themselves.

The centre-forward leads the press and will angle his pressure to cut off one side of the pitch.

Typically, the striker forces the attacking team to play to the side where they are weakest, giving Bayern the upper hand.

Once the ball is moved out to the opposition’s fullbacks, Bayern go man-for-man, switching from a zonal to a man-oriented approach and using the sidelines as an extra defender to try and win the ball back as high up the pitch as possible.

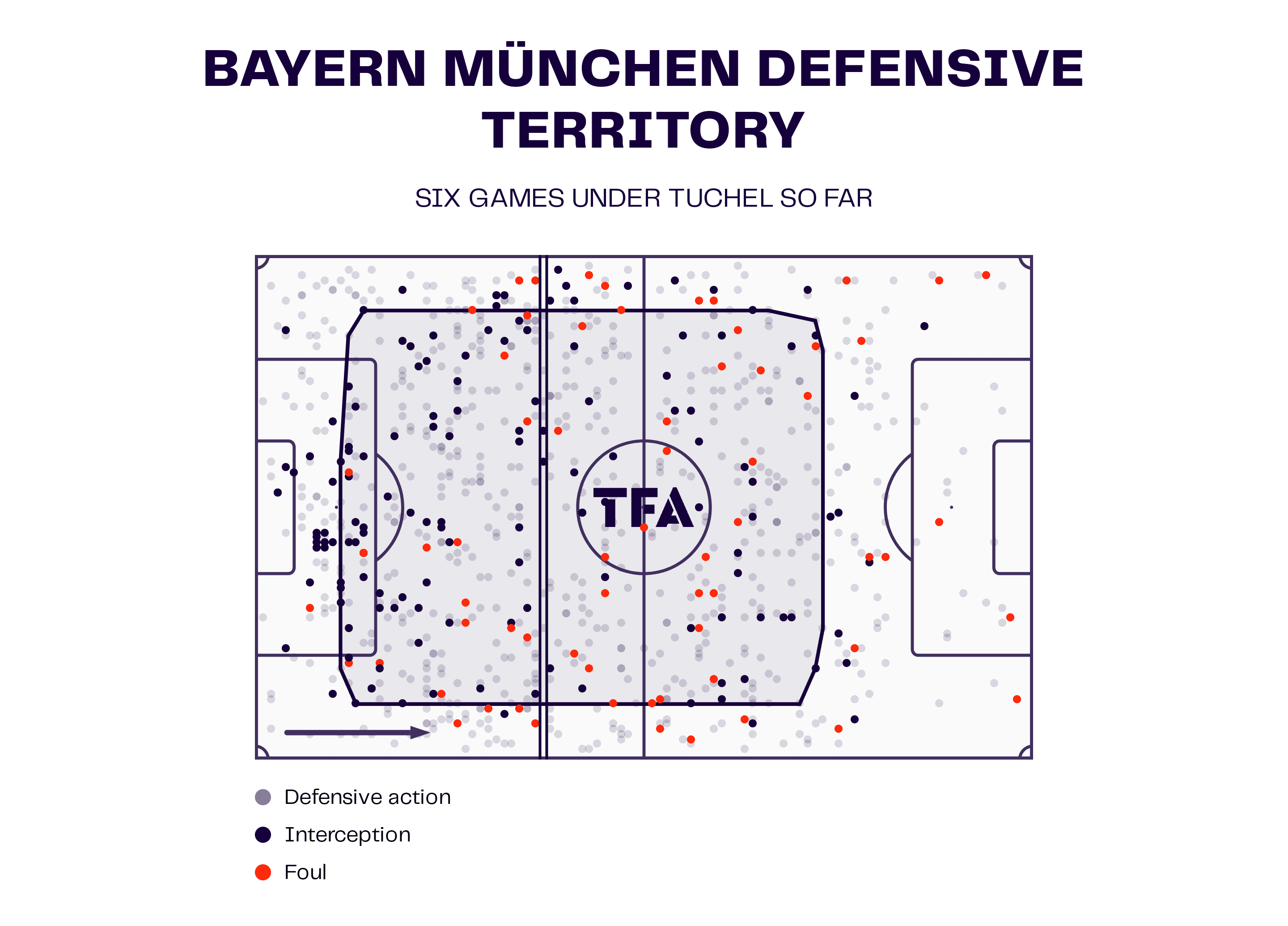

According to the side’s defensive territory map, Bayern has kept quite a high line on average.

This is even more impressive, considering they faced Manchester City twice in Europe.

Lower down the pitch, Bayern drop off into a 4-4-2 mid-to-low block.

The number ‘10’ joins the first line of pressure alongside the centre-forward, while Tuchel wants his team to stay compact between the lines to prevent opponents from easily playing through them.

But there have been problems in this phase.

While the German side has already conceded quite a few goals from transitional situations, its defensive structure in the deeper areas has been far from secure.

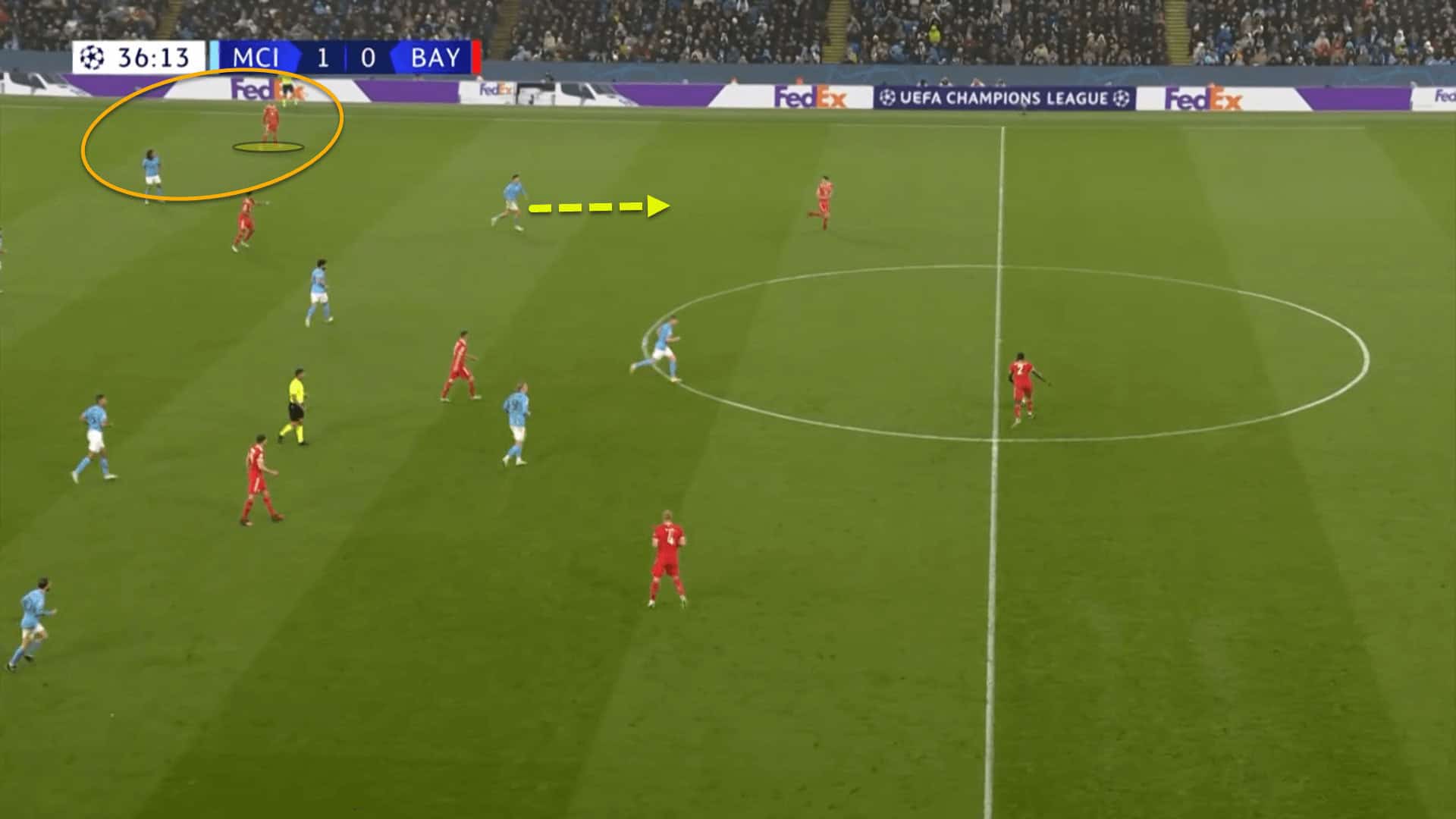

This was seen right before Rodri’s goal to open the scoring for Man City last week in the Champions League.

Due to the spacing of the City players, centre-backs Matthijs de Ligt and Dayot Upamecano were pulled apart, and a massive gap opened down the centre of the defensive line.

This can happen to a lot of teams.

But it’s vital that the space is plugged by one of the midfielders.

Bayern’s issue is that the double pivot is unsure whose job it is to step into the backline.

In the previous screenshot, Leon Goretzka pushed across to defend the wide spaces despite the fact that he was not threatened.

Meanwhile, Joshua Kimmich makes the decision to drop in between the centre-backs to plug the gap.

But this left a lack of protection in front of the defence.

If Goretzka had stayed in the middle or if Musiala had dropped back temporarily, danger could have been averted.

But they didn’t.

Musiala fell back too late.

Rodri received the ball outside the box, flicked it past the young German attacker and smashed it home from range with a beautiful strike.

Kimmich could have stopped the shot, but because he was so deep between the centre-backs, he couldn’t step up in time.

This goal signalled the start of what was to be a torrid night in Manchester for Bayern.

Here is another example where Bayern’s defensive block was far from secure.

Once again, the centre-backs were separated due to the positioning of the opposition, leaving a massive gap between Upamecano and de Ligt.

The nearest pivot player is Goretzka, who is not busy occupying an opposition player.

He doesn’t notice the space and fails to drop in to cover for de Ligt.

Luckily for Tuchel’s side, Hoffenheim doesn’t take advantage of this, as the centre-forward does not make a run in behind that could have been threatening.

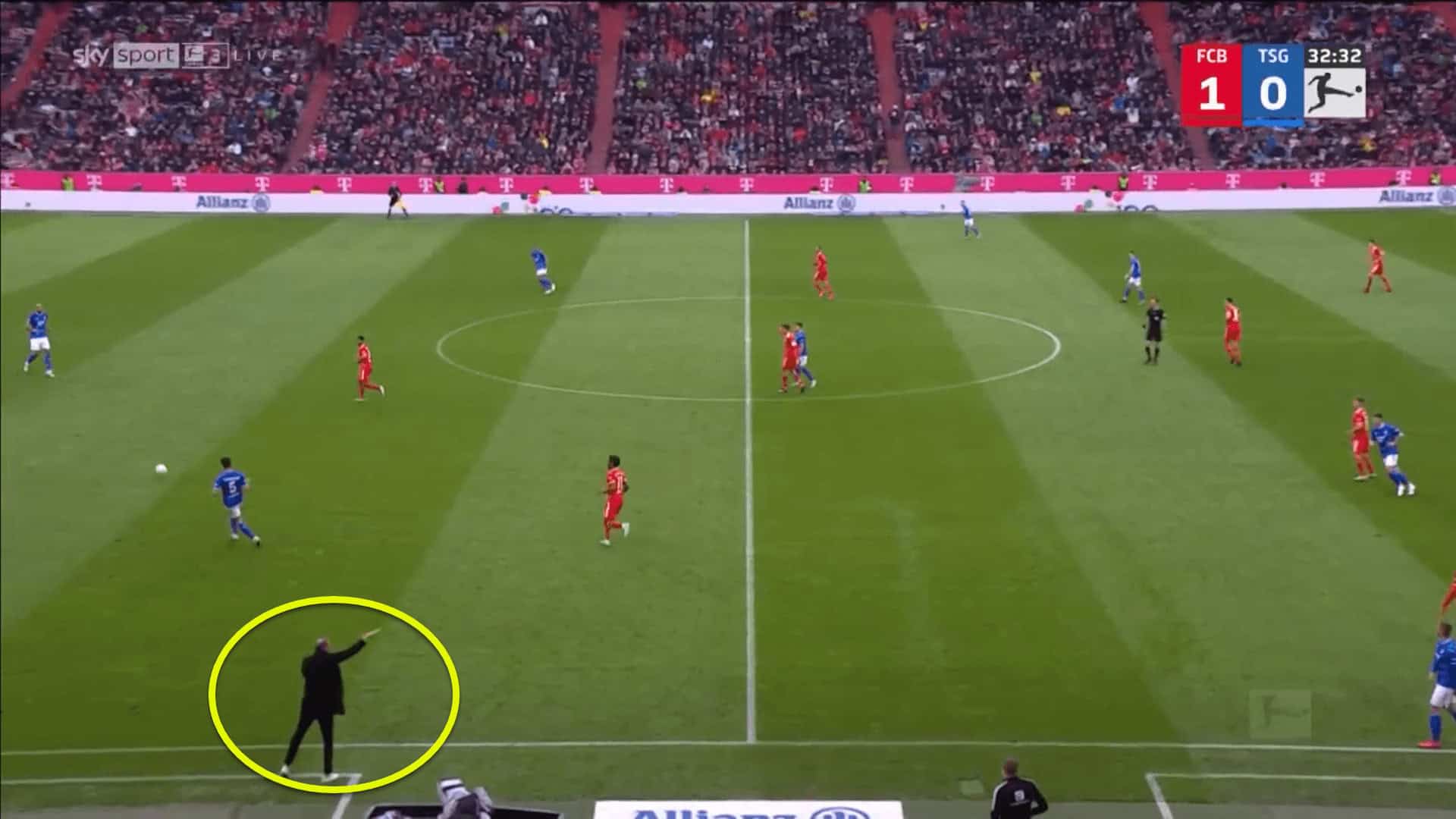

Merely a second or two later, Hoffenheim manager Pellegrino Matarazzo tells his number ‘9’ off for not noticing the apparent lapse in Bayern’s backline and has signalled for him to make the run next time.

Tuchel tactically still needs to do a lot of work on the training ground regarding the team’s set-up out of possession.

Die Bayern are far too susceptible to conceding goals when they are broken down in open play or when they are hit on the break.

Under these circumstances, a treble was nothing more than a pipe dream by a somewhat deluded hierarchy.

Nonetheless, if anyone is to fix these problems, it’s Thomas Tuchel.

Conclusion

It certainly hasn’t been an ideal start for the German manager back in his home country.

Two victories in six matches would not have been on his to-do list when he took over at the Allianz Arena just a few weeks ago.

But football doesn’t allow for pity, and Tuchel won’t let this group of players to wallow in their own misfortunes.

An eleventh-straight Bundesliga title is still up for grabs and Bayern are still in the driving seat – for now.

By the end of the campaign, the experienced coach will have a much greater understanding of the tactical strengths and limitations that his players have.

And with a summer transfer window on the horizon, we can expect a very different Bayern Munich next season.

Comments