In our previous throw-in analysis, we started a throw-in series by

discussing their unique nature compared with other set pieces.

We also discussed the different purposes and measurements of throw-in success, ending with the various strategies and kinds of defending throw-ins.

Since we do not wish to rush delving into superficial analyses, we are keen first to understand what lies (behind the scenes) in order to discern the nature of throw-ins and what fundamentally distinguishes them.

Consequently, we can direct our tactical analysis towards them in an informed manner.

Therefore, we turned to one of the pioneers in the field of throw-in tactics.

Someone who has achieved numerous accomplishments with various clubs and national teams, Coach Thomas Grønnemark.

With over 20 years of experience coaching throw-ins, Thomas Gronnemark has trained numerous well-known clubs, including FC Midtjylland, Borussia Dortmund, Brentford, AFC Ajax, and, of course, Liverpool, where he spent five years during Jürgen Klopp‘s successful era.

Now aiming to disseminate his knowledge on a broader scale, he currently works as a freelancer with various teams and offers many courses and consultations through his website (Throw In Academy).

He aspires to transform football and help many gain a deeper understanding of throw-ins in the world of football.

This comprehensive tactical analysis will be an interview with him divided into two parts, filled with valuable details and information.

In this part, we will discuss the importance of technique in throw-ins and its impact on tactics, examining his theory of long, fast, and clever throw-ins.

After that, we will explore the differences between set-piece routines and his strategy for throw-ins, discussing his throw-in time-complexity model.

In the upcoming part, we will discuss his defensive strategies, inquiring about his preferred defensive system and how he responds to various attacking scenarios from opponents, such as targeting the area behind the defensive line quickly exploiting the absence of offside when a throw-in occurs in his defensive third, whether he marks the thrower and similar aspects.

We will also discuss the coaching aspect, some situations and whether he sometimes conflicts with the head coach.

Additionally, we will explore how he addresses different coaches’ preferences, such as what he does if he is not allowed to use the sixer in rotations to create space for increased security during an attacking throw-in.

Finally, we will discuss his tenure at Liverpool, the extent of development seen in some players and the different roles of standout players like Mohamed Salah.

Technique Before Tactics

TFA: Starting with your ‘long, fast and clever’ theory, do teams need long throw-ins only in the final third to threaten the goal, as many think?

Grønnemark:

No, you can use long throw-ins for three purposes:

1- Of course, threatening the opponent’s goal when you are close.

2- Counterattacks behind the defence exploiting that there is no offside in throw-ins

3- The longer you throw, the bigger the throw-in area you have, so you can throw to more teammates to keep possession and make pressing you difficult.

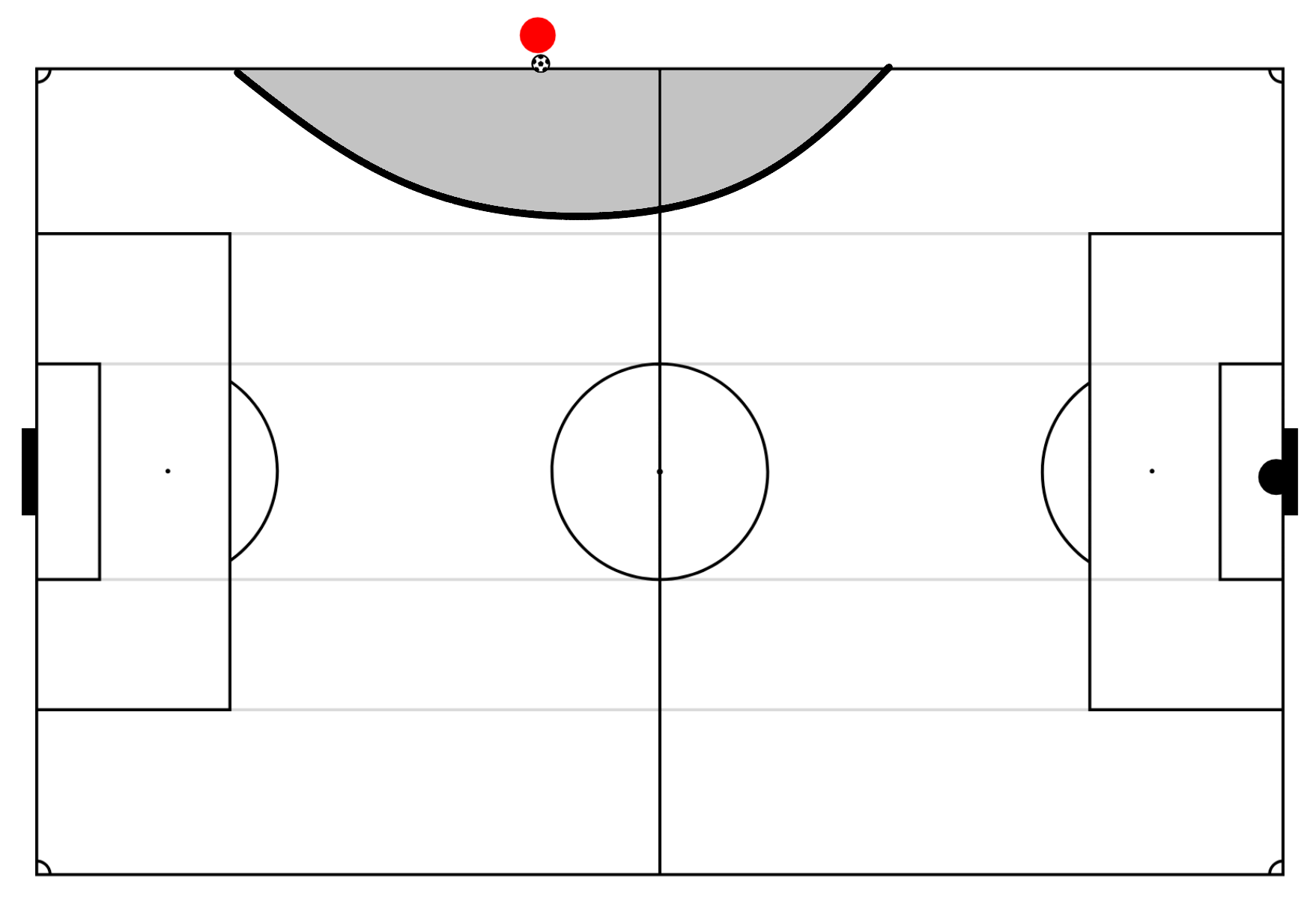

For example, Andy Robertson improved from 19,80 meters to 27,00 meters, improving his ‘throw-in area’ (the half circle you can throw in if you are standing near the midline, as shown below) by 530 square meters.

Most of my coached players improved by five to ten meters, while some reached 15 meters only with efficient technique.

So all my teams needed it with different playing styles: Brentford, Liverpool, or Ajax.

TFA: Moving on to the term ‘fast’, do you teach them how to play fast to a near and free player or behind the defensive line? Is playing fast always beneficial?

Grønnemark:

It is not always beneficial.

In my philosophy, once we get the throw-in, the nearest player goes fast and scans to see if a food option exists.

If not, don’t throw fast.

One of the worst things you can do is throw fast into a high-pressure zone.

Regarding teaching, yeah, it isn’t a simple idea.

I’m just saying play fast!

They should be trained to make good decisions.

TFA: Do you agree that throwing backwards has a better opportunity to keep the ball?

Grønnemark:

No, it’s not necessary.

This question touched me because I see this challenge in football in general, not only throw-ins.

People see the data and say, “Wow! Throwing backwards keeps the possession more.”

We should see football from a much bigger perspective.

Of course, throwing backwards gives an excellent opportunity to keep the ball, especially when there is no pressure.

I can also add benefits, like playing a mini switch to the further centre-back with some kinds of movements, which can be a good option for finding space and even scoring goals after that.

However, you shouldn’t first try to look backwards.

Instead, you should look at the entire 180-degree angle around you without limiting your options to just backwards, scan, see the opponent’s defending pattern, and then create space in many different ways.

It can also be a wrong choice when you just play backwards.

For example, opponents may try to make you just throw backwards to press you with three players, for example, to take the ball in a dangerous area, and that’s why I told you that you sometimes need to play inside, down or diagonal the pitch

TFA: Does a communication or a sign happen between the thrower and the receiver to make the thrower know the timing or to throw the ball into the area, not the body?

Grønnemark:

Of course, that is one of the many things you can do, but you don’t have to.

You can also depend on reading each other, but it is possible, especially while working as a freelancer, not full-time.

TFA: On the other hand, defensively — against fast throw-ins — given that there is no offside, what do you do defensively about that? For example, do you ask your players to quickly retreat to establish enough depth in the defensive line, especially in your defensive third?

Grønnemark:

Of course, because the offside trap is absent, you should be more aware of runs-in behind, but establishing depth in the defensive line isn’t enough.

For example, I saw a game in which a defender sprinted backwards to get deep without scanning while there was no danger behind him.

This allowed the attacking team to exploit the area in front of him, leading to a good situation.

TFA: In your opinion, does being thrown with the hand, not the leg, help in that edge because you can control the hand more, although the leg is stronger?

Grønnemark:

Yes, if you train well, you can put the ball as precisely as you want and much bigger than the feet.

The challenge is that not a lot of teams train throw-ins, so I often see a good space, but the throw is imprecise.

Hence, I agree, but if you don’t train, it will be worse.

It is not a random process; you need to know when and how to throw to the foot, in front of the running player and down the opponent — and sometimes in a floated way.

A Clever Throw-In Doesn’t Mean A Routine

TFA: If we don’t have the chance to play long or fast, the clever term comes, but you always emphasise that throw-ins have a unique nature compared to any other set piece, and treating them purely as a set piece is a mistake; why do you think this?

Grønnemark:

Throw-ins are always part of set-pieces, but I mean that throw-ins have a different nature, but dealing with them like corners and free-kicks is a big mistake because of the lack of knowledge.

Dealing like that limits your options.

I love the effect of set-piece coaches on football, having met many of them at work, but I have a concern that some of them take the same approach in throw-ins as corners and free-kicks.

This is the reason for being a freelancer: to change the football and how people see throw-ins.

I helped many teams in promotion while being a part of 15 titles in international football.

If I were full-time, I wouldn’t be able to share my knowledge as widely as I do with you now.

TFA: What will happen if we prepare a routine trying to implement this predesigned one?

Grønnemark:

If you have already decided what you would do (predesigned routine), you have a big chance not to succeed because:

1- You can be faced with an excellent sudden opponent’s defending pattern

2- The opponent may also just mark your option well

I saw many teams already planning what they would do in the middle zone, for example, and then it didn’t work. They couldn’t behave or insist on doing that with a bad quality and result.

Hence, having a routine (which I call a tool) is a phase for me, but I do not stop on it.

TFA: Could you explain the last phrase more?

Grønnemark:

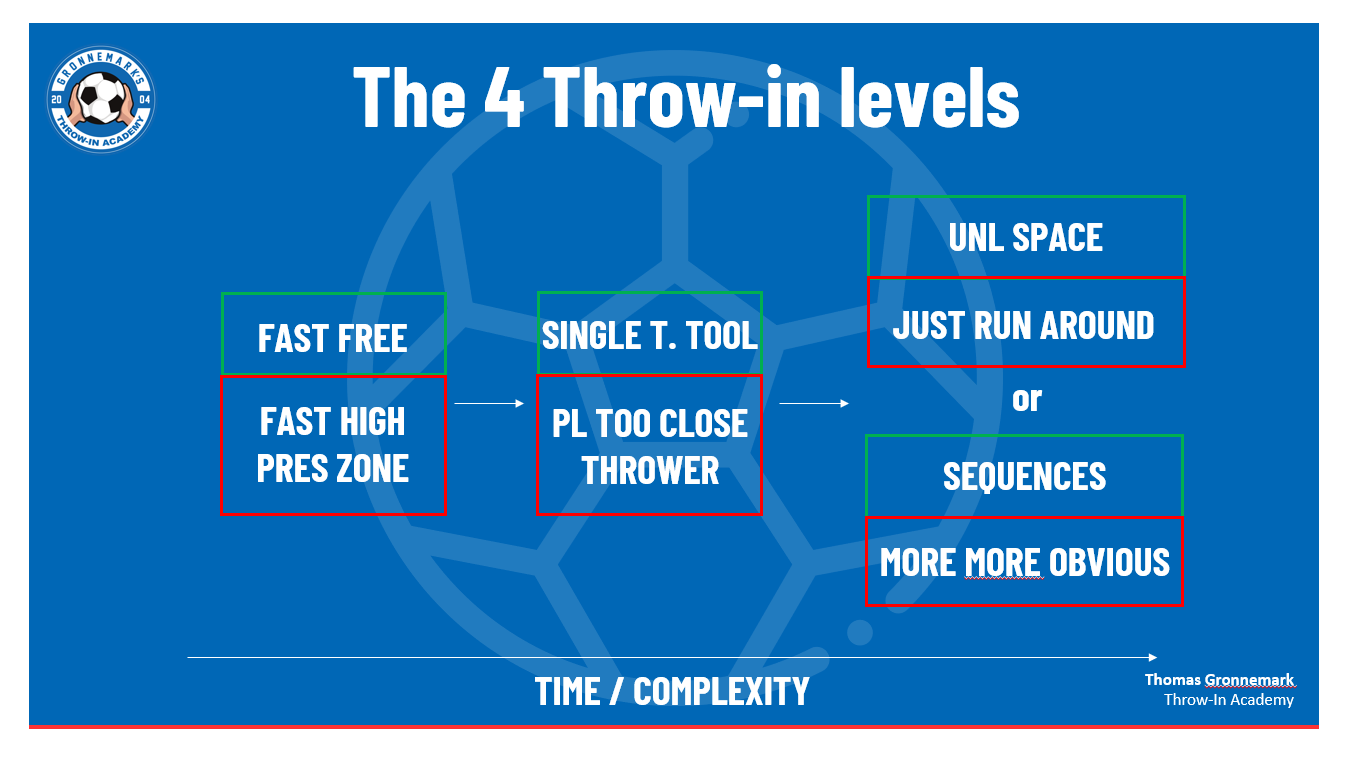

You can prepare a tool (routine), but don’t limit your options if this doesn’t work because if you get the ball early and decide that there is no good fast option, you will have 15/20 seconds to implement many different kinds of creating space.To make it more straightforward, my time-complexity model is shown in the photo below. Now, let’s dissect this process.

Grønnemark:

Of course, it depends on your team.

For example, Liverpool had so many spacially intelligent players which led to unlimited space creation.

If you don’t have so many players like them, it’s better to use sequences.

TFA: Thanks for your time and the valuable details!

Comments