Every season, in all leagues across the world, there are always teams who undermine viewers’ expectations in terms of their underperformances relating to results and league table positions. Torino are quite possibly one the best examples of this alongside Sheffield United in European football, considering the stature of and history of the Italian giants. Il Toro have massively underperformed to worrying levels in Serie A in this campaign and could find themselves in real trouble the further the season unravels.

In this tactical analysis, we will delve deep into the tactics of Marco Giampaolo’s side as well as their statistics for the season and find out exactly how, and why, Torino are currently in a relegation battle in Serie A, sitting in a nervy 17th place, level on points with Spezia and Genoa below them. At the end of the analysis, which will be written in the form of a scout report, we will have examined whether or not Torino should be where they are in terms of their league position.

It must be noted that this article was written before the outcome of Torino’s home game against Hellas Verona on Wednesday.

Torino’s style of play

First and foremost, one of the most important factors to consider, when analysing a team’s overall performance and whether they should be performing a lot better, is their style of play so as to understand exactly which metrics need to be evaluated.

Torino have predominantly been more of a counterattacking side over the past few years. However, in the summer of 2020, the board were looking for a complete overhaul of their stale style of play, and so appointed the ex-Sampdoria and Milan boss, Marco Giampaolo. Whilst Giampaolo never quite succeeded at the latter, it was the former where he earned massive respect for his possession-based, fluid, attacking system.

In the Italian’s final season at I Blucerchiati, he guided the team to a ninth-place finish. In comparison to last season, Claudio Ranieri only managed to help Sampdoria finish fifteenth, eleven points worse off than the previous campaign.

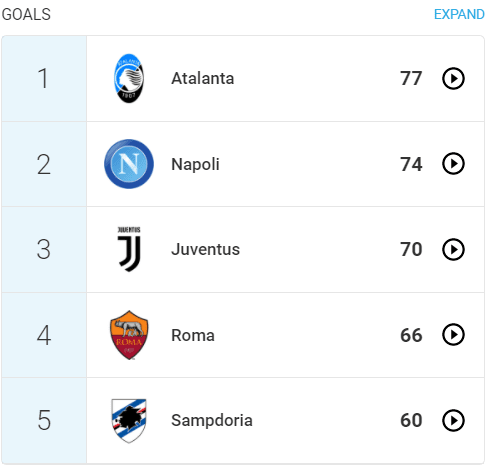

As we can see from the above metrics taken from Wyscout, Sampdoria finished the 2018/19 season ranked seventh in average possession per game under Giampaolo.

They also scored the fifth-highest amount of goals in the league that season, another incredible feat showing the excellent coaching that Giampaolo had done at the club to implement his energetic style of play.

A Juventus side, with a potent forward line including Paulo Dybala, Gonzalo Higuain, and of course Cristiano Ronaldo, only managed to outscore Sampdoria by 10 goals, a true testament to their electrifying football under the Italian.

However, at Torino, with arguably a better starting eleven than the one Giampaolo had at Sampdoria, Il Toro are massively underperforming in terms of their metrics for a side who want to focus on ball possession with a strong emphasis on ball retention as their style of play.

It must be taken into account that any transition from a defensive, counterattacking system – one that Torino have played for many years – will be difficult to overhaul in such a small space of time, but at the moment, off of this season’s evidence, the plan needs to change and change quickly.

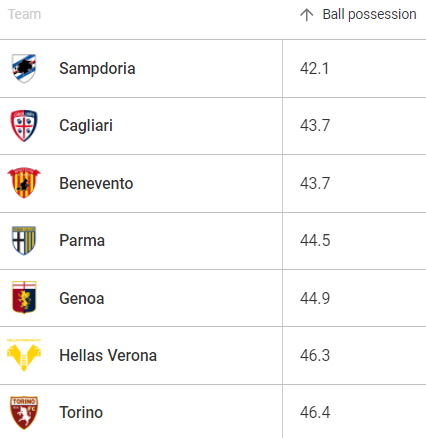

This season, Torino currently sit as the seventh lowest-ranking team in terms of average ball possession with 46.4 percent as of writing. As we can see from the table above, the teams who rank worse than them are all mid-to-lower half of the table teams. Only Genoa, who have less possession, are lower in the actual Serie A table, meaning that Torino are not maximising their usage of the ball when they have it.

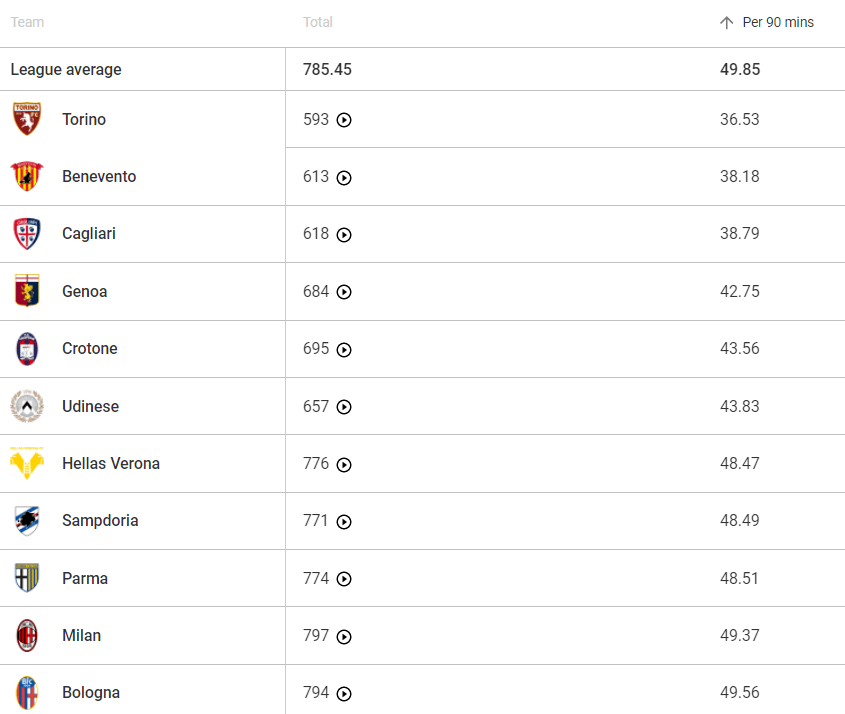

Giampaolo’s men have the lowest number of passes into the final third in the league with only 36.53 per 90, which means that it is not so much to do with the lack of possession, but rather what they do with the ball. The reasons for this are unclear yet, but later in the article, we will delve deeper into their tactical and structural problems by analysing Torino using in-game footage.

Structural problems in possession

As stated in the previous paragraph, Torino’s problems in possession stem from their structural problems, particularly in the build-up phase and positional attack/established possession phase.

Merely claiming that they lack quality and need to dip into the transfer market would be somewhat of a ‘cop-out’ considering they bought Karol Linetty, who previously played at Sampdoria under Giampaolo, as well as Amer Gojak, but they also have quality midfielders like Tomas Rincon, and Soualiho Meite at their disposal too.

Il Toro played a 4-3-1-2 – Giampaolo’s favoured formation – but more recently, due to some appalling results, they have switched to a more conventional 5-3-2. Whilst in the established possession phase, their shape looks like a 3-1-4-2 or 3-3-2-2 depending on the position of the wingbacks.

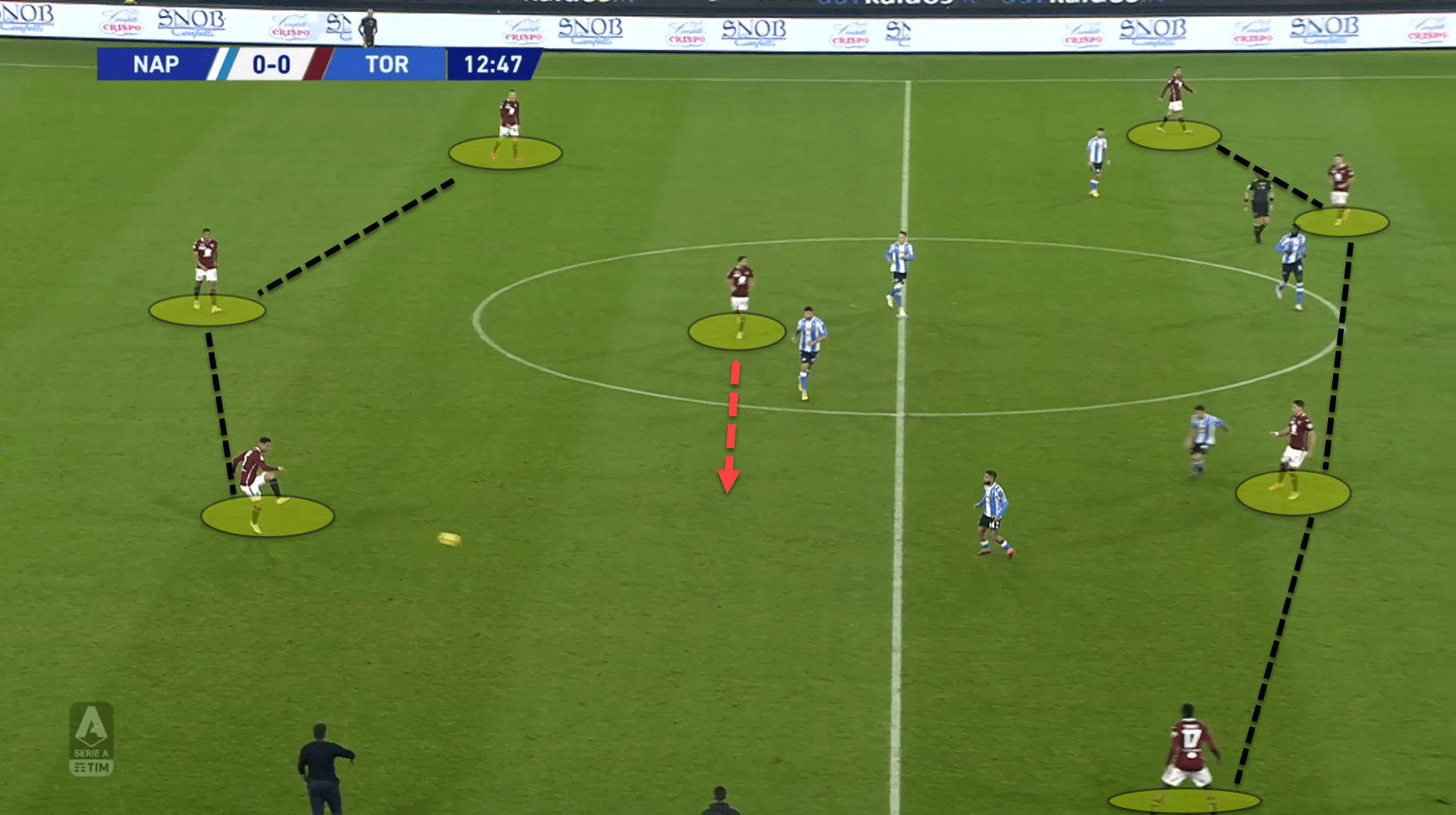

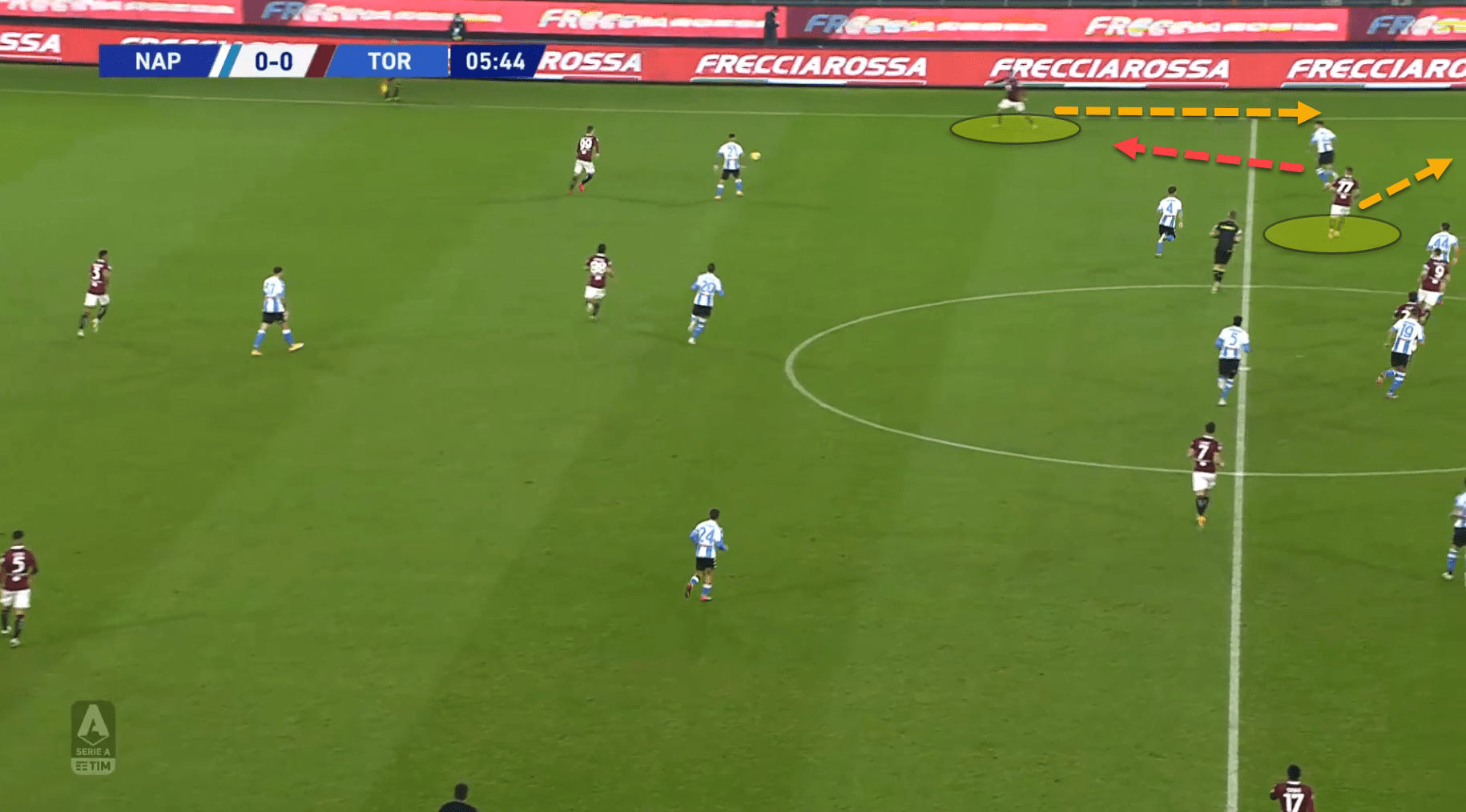

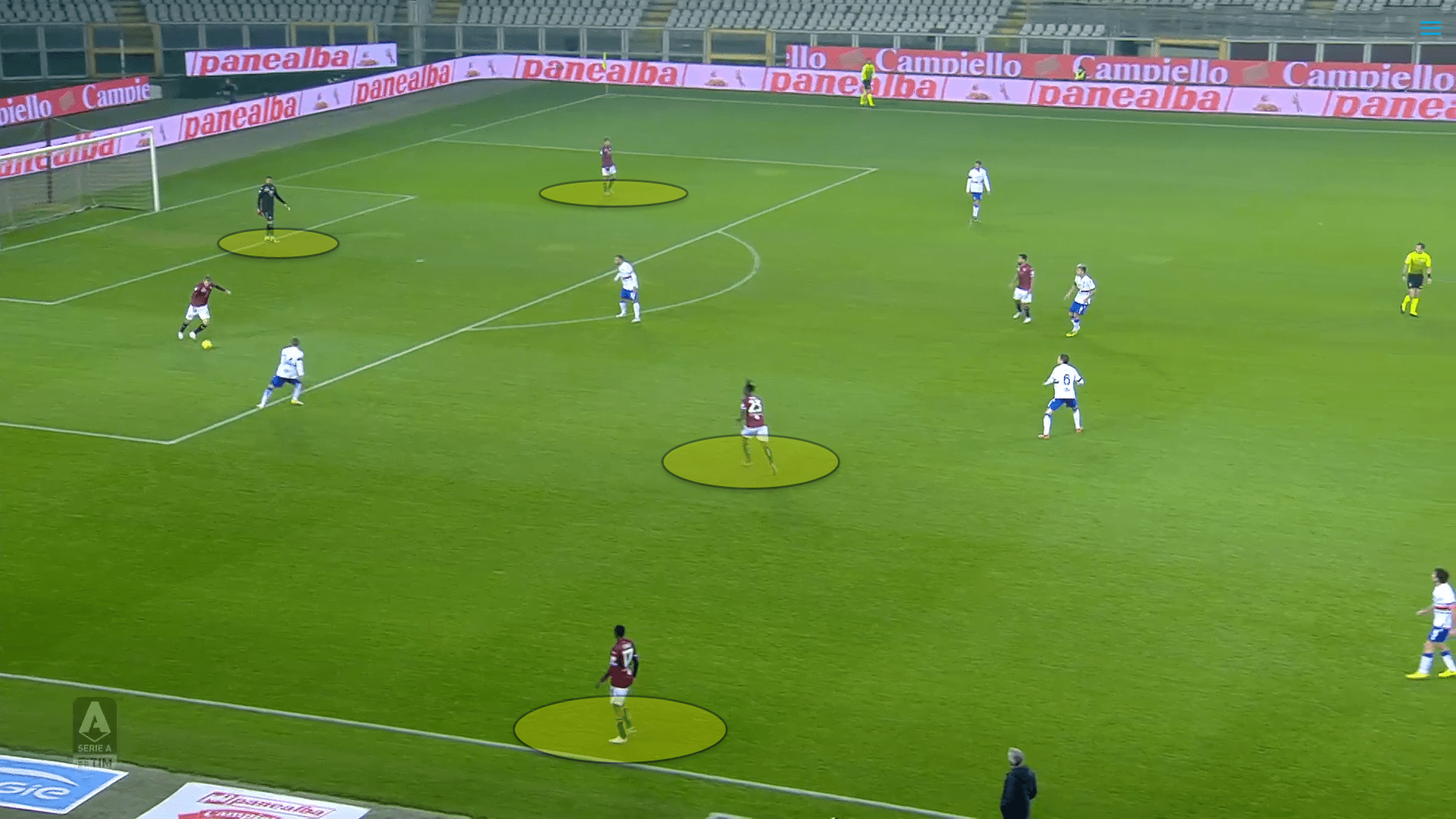

Here is an example of Torino’s offensive structure whilst in a positional attack. The three centre-backs typically maintain a substantial distance from one another so to cover the width of the pitch but also to keep within close proximity to plug the gaps between them when they lose the ball and the opponent transitions from defence to attack.

The wingbacks push high up the pitch as wide midfielders and sometimes venture even further forward as wingers, often making runs beyond the opponent’s backline as they are the only width on the pitch for Il Toro.

There is usually one single-pivot in a midfield trio who sits in front of the backline when they are circulating the ball in front of the opposition’s front press, which can be seen from the previous image. This player shifts from left to right, depending on who has the ball, to act as a short passing option.

The other two more advanced central midfielders are often instructed to position themselves between two players in the opposition’s midfield line. Torino generally build out of the back through the wide areas – perhaps not the ideal scenario for how Giampaolo wants his side to play – and so when the ball is played to the feet of the wingbacks, the ball-near central midfielder will make an advancing run down the channel.

This is a fine way of playing through the opposition’s defensive block and is quite possibly Torino’s most efficient way of doing so apart from playing long, which they tend to do quite often.

When the ball is played out to the wingback, as has occurred in the previous image, the opposition’s fullback, or wingback, will engage in a press to close down the wide man before he receives the ball. This leaves space on their blindside down the flanks for the attacking team in possession to exploit.

When the player received the ball above, he opened out his body and played down the line, allowing the ball-near central midfielder to get in behind. Another example can be seen in the next image from the same game:

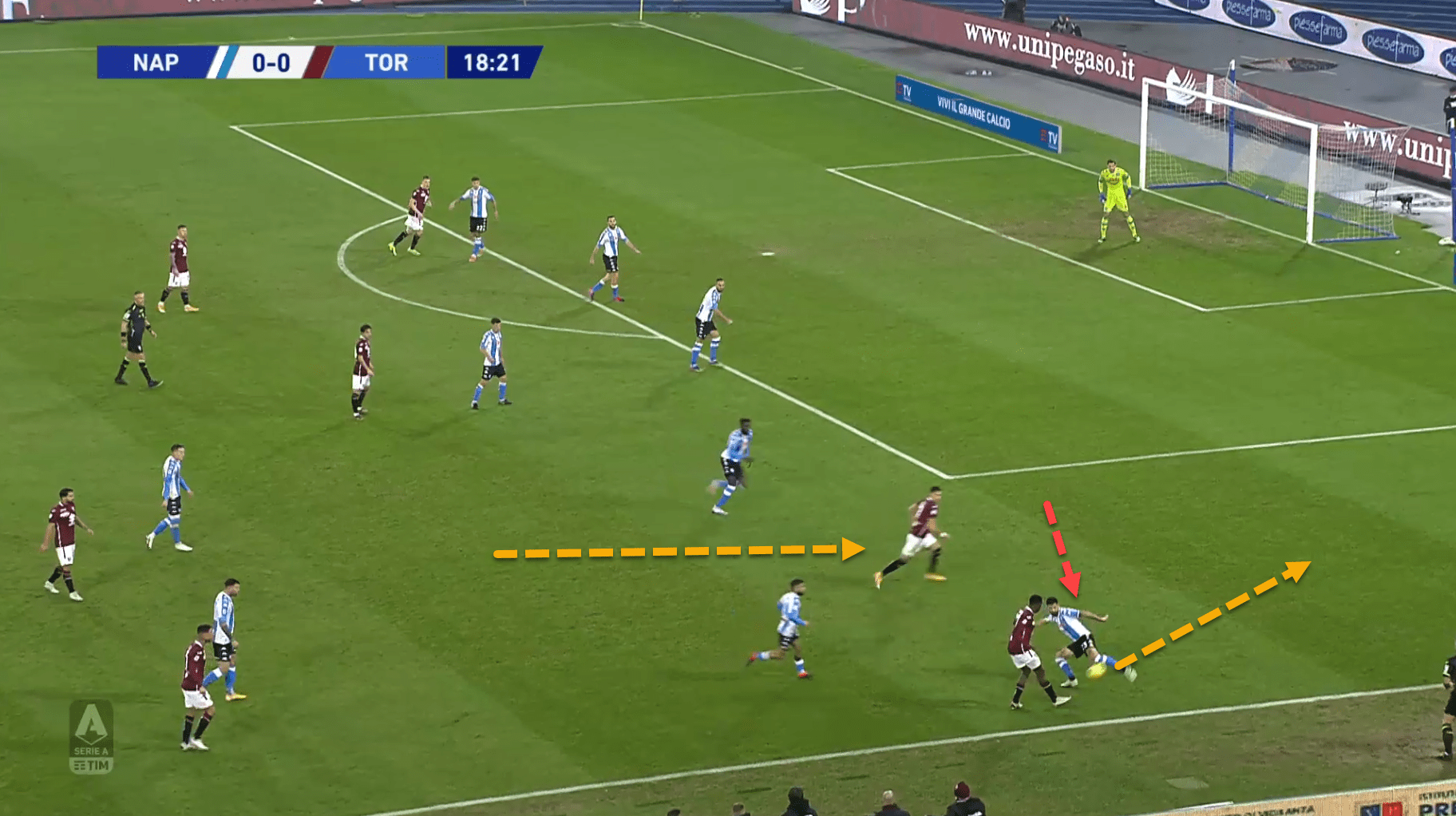

Here, the Napoli left-back has moved out to close down Wilfried Singo, the Torino right wing-back. By doing so there is space on his blindside for Sasa Lukic to attack and break through the opponent’s low-block.

However, these examples above are scenarios where this wide build-up play worked. The reason that Torino struggle so much in possession is because they are ultimately poor at breaking their opposition’s block down, resorting to long passes into the channels to Andrea Belotti instead – which are usually their most efficient way of getting into the final third. On average per game, Il Toro plays 41.8 long balls, with a 65.3 percent accuracy, the second-highest in the league.

Their build-up play can be easily defended against, which forces them to play long in the end.

Similarly, to the previous image, the ball has been played to Singo, but the Napoli left-back has angled his press and gotten extremely tight, preventing the player from opening out his body and playing down the line, which in turn forces him to play back to the centre-backs and recycle possession.

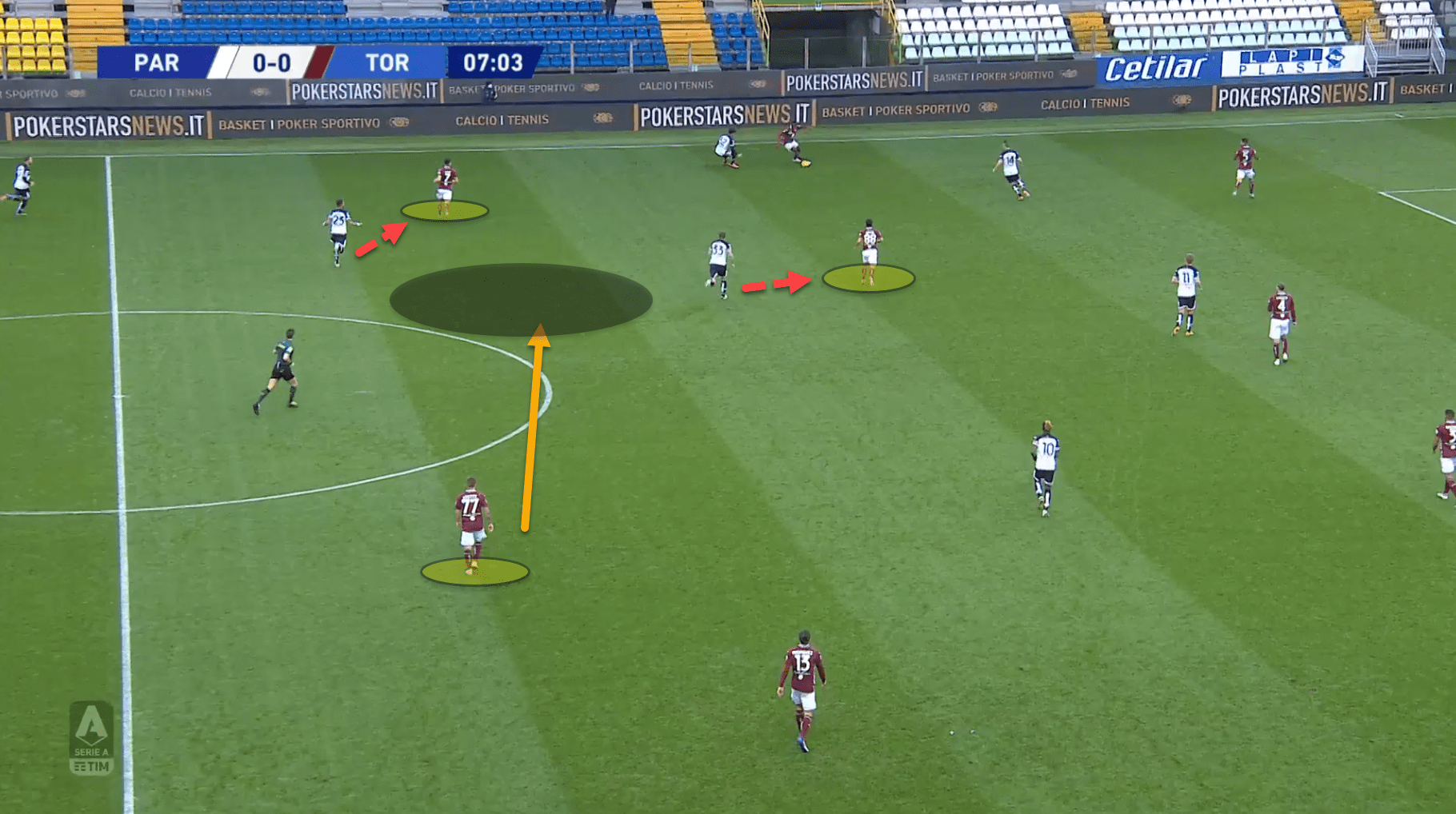

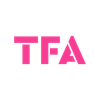

They also lack support in the centre of midfield when in a positional attack and so find it very difficult to play through the central areas. In order to be a possession-based team, you must have passing options in the central corridors to provide support when trying to build-up through the thirds, which Torino rarely have.

Here is an example of that, the three central midfielders (circled), are too far apart. Parma have gone man-to-man in their press, cutting off passing lanes to two of these central midfielders whilst the final midfielder is too far away to offer support. He needs to drop shorter and take up a position – as seen above – to become a viable passing option and help his team play out of the press.

Going long from a high press

We have already touched on Torino’s reliance on playing long passes forward to move into the final third. Giampaolo’s side have one of the highest numbers of successful long passes played per 90, as stated before, with 65.3 percent. This is almost exactly one-third of their long balls.

Whilst they have such a high success rate, they still lose possession 34.7 percent of the time with these long balls. Essentially one in three leads to a turnover in possession.

The major problem with this is that there is almost an overreliance on these aerial balls to progress the side forward in possession, typically when the opposition press Torino high. There could be two main reasons for this; Giampaolo may instruct his players to do so because he does not trust their ability, particularly his centre-backs, to play out of the back, or else there is a lack of confidence in the players’ own abilities to do so.

We will provide a few examples of situations where this seems to occur when an opponent presses high on the backline.

In this example, Sampdoria have pressed Il Toro high whilst in the build-up phase. The Torino centre-back has four clearly available passing options, with two being progressive options. However, he instead opts to play long and his team turnover possession.

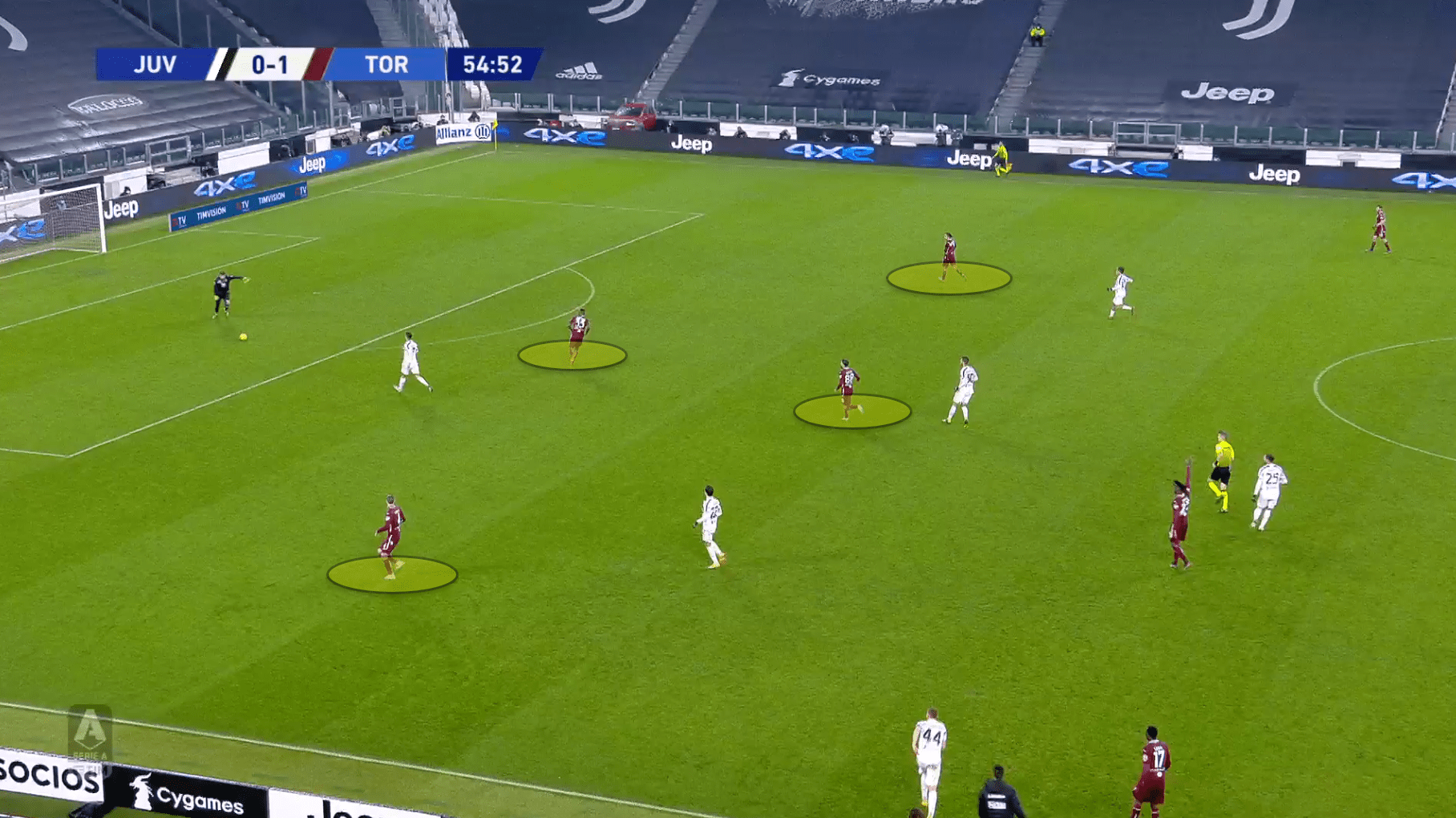

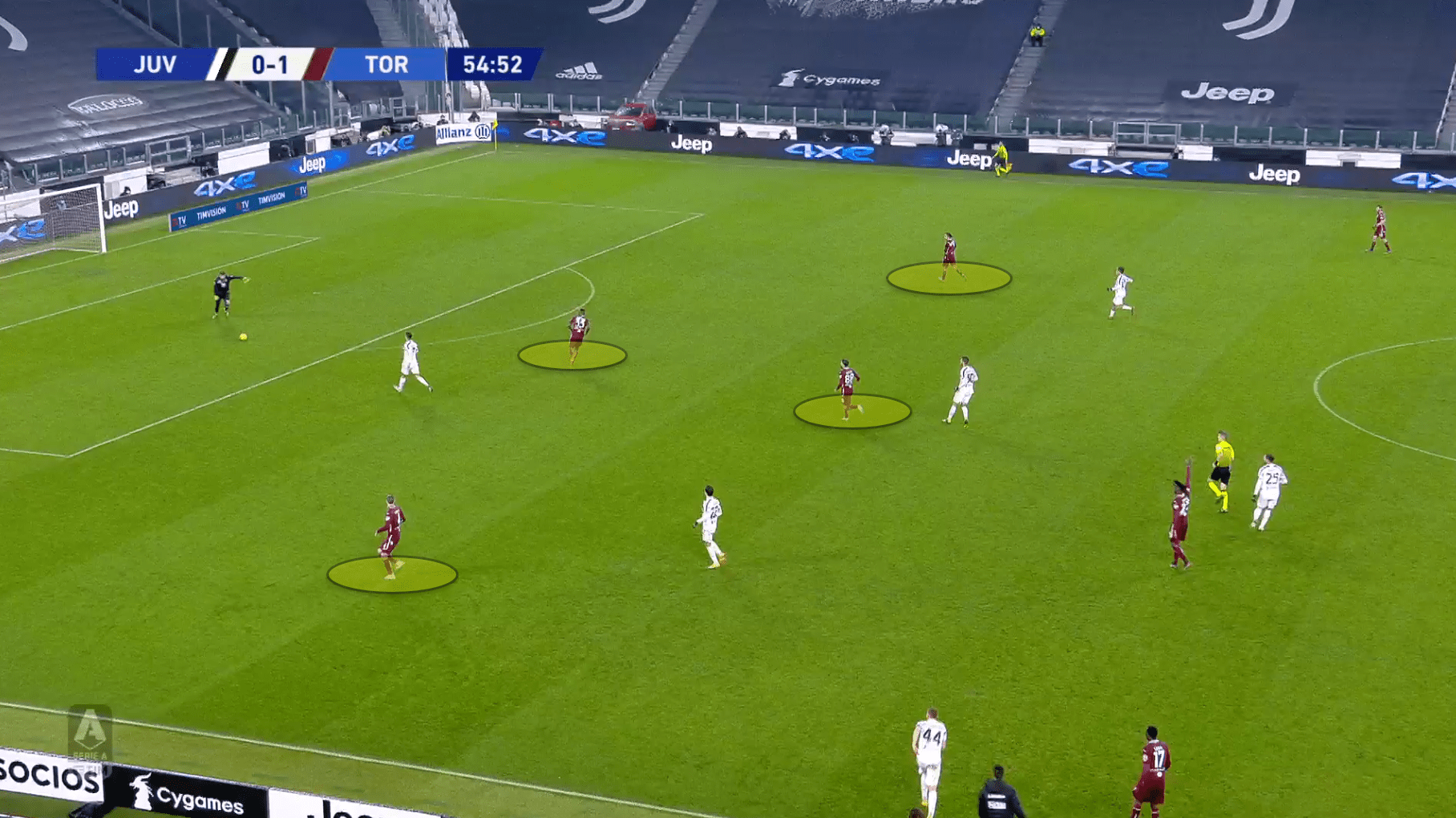

Once again, Juventus are deploying a high-press against Torino when they are trying to build out from the back. Salvatore Sirigu has four open passing lanes in front of him at close proximity, particularly the central centre-back, but instead opts to go long, leading to yet another loss in possession for his team.

The aim of this article is not to condemn a certain style of play. There is, of course, always room in modern football for long balls, but in situations like the two shown above, for a team who are supposedly transitioning into a possession-based side, playing needless and thoughtless long balls forward seems quite peculiar when there are short passing options available.

Whilst Torino have scored 25 goals this season – the most in the bottom half of the table – and are overperforming their expected goals which is currently 20.82, it may seem unfair to pick apart their offensive structure and system, but one must consider that 9 of these goals came from set-pieces.

Frailties in their defensive structure

Torino rarely press high, mainly because of the severe lack of pace in their backline, and instead, just sit in a low-block for most of their games when defending. Il Toro’s Passes Per Defensive Action (PPDA) currently sits at 14.94, the highest in the league, proving how passive they tend to be when the opposition has the ball.

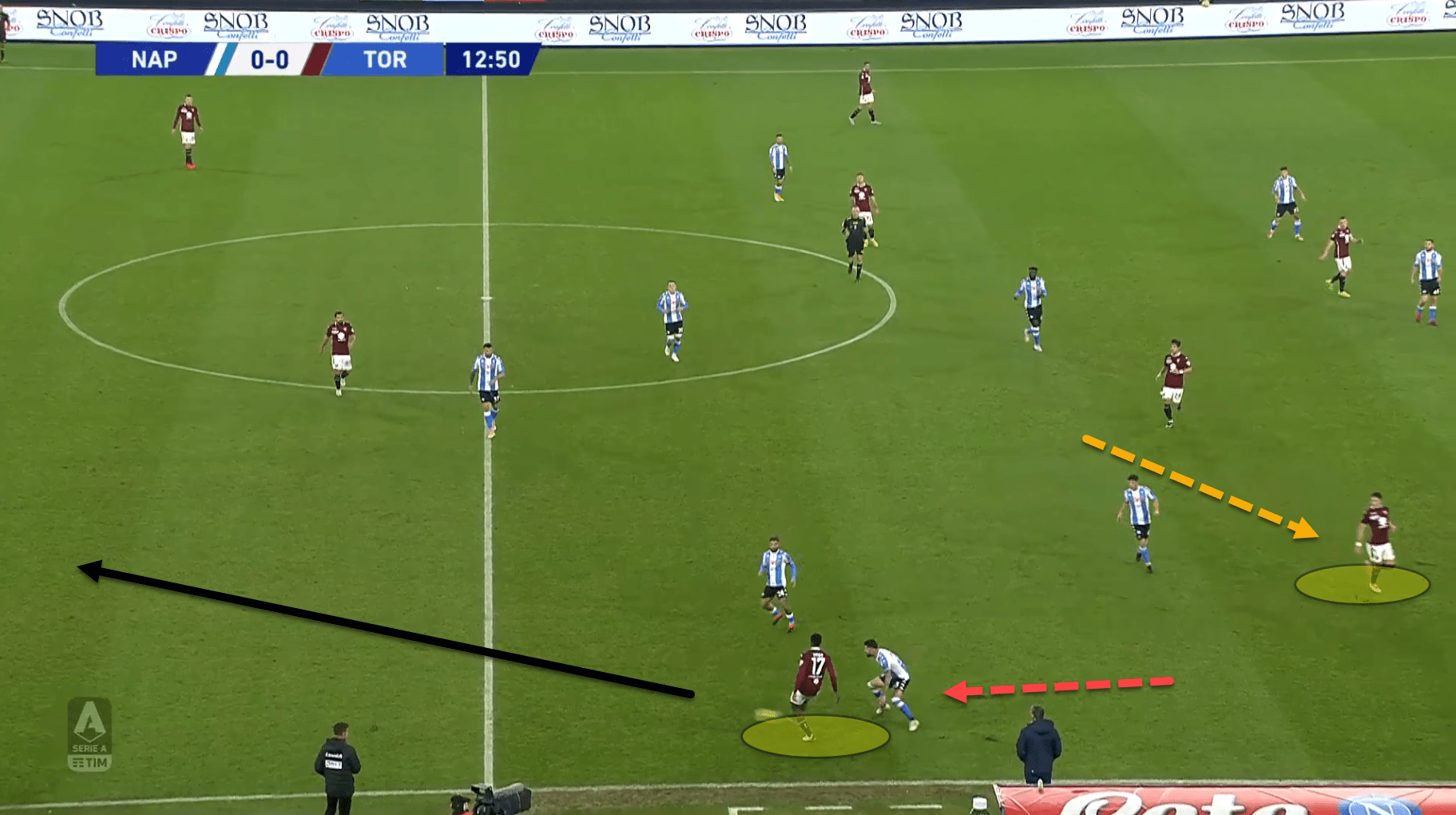

However, they are far too easy to break down in a low-block, particularly in the central areas and so have conceded 32 goals already after just 15 games. The problem is the gaps they leave between the lines for their opponents to exploit against their low block.

When sitting deep, the best way for the defending side to nullify the opposition’s forward line and creative players especially is by compacting the space between the lines.

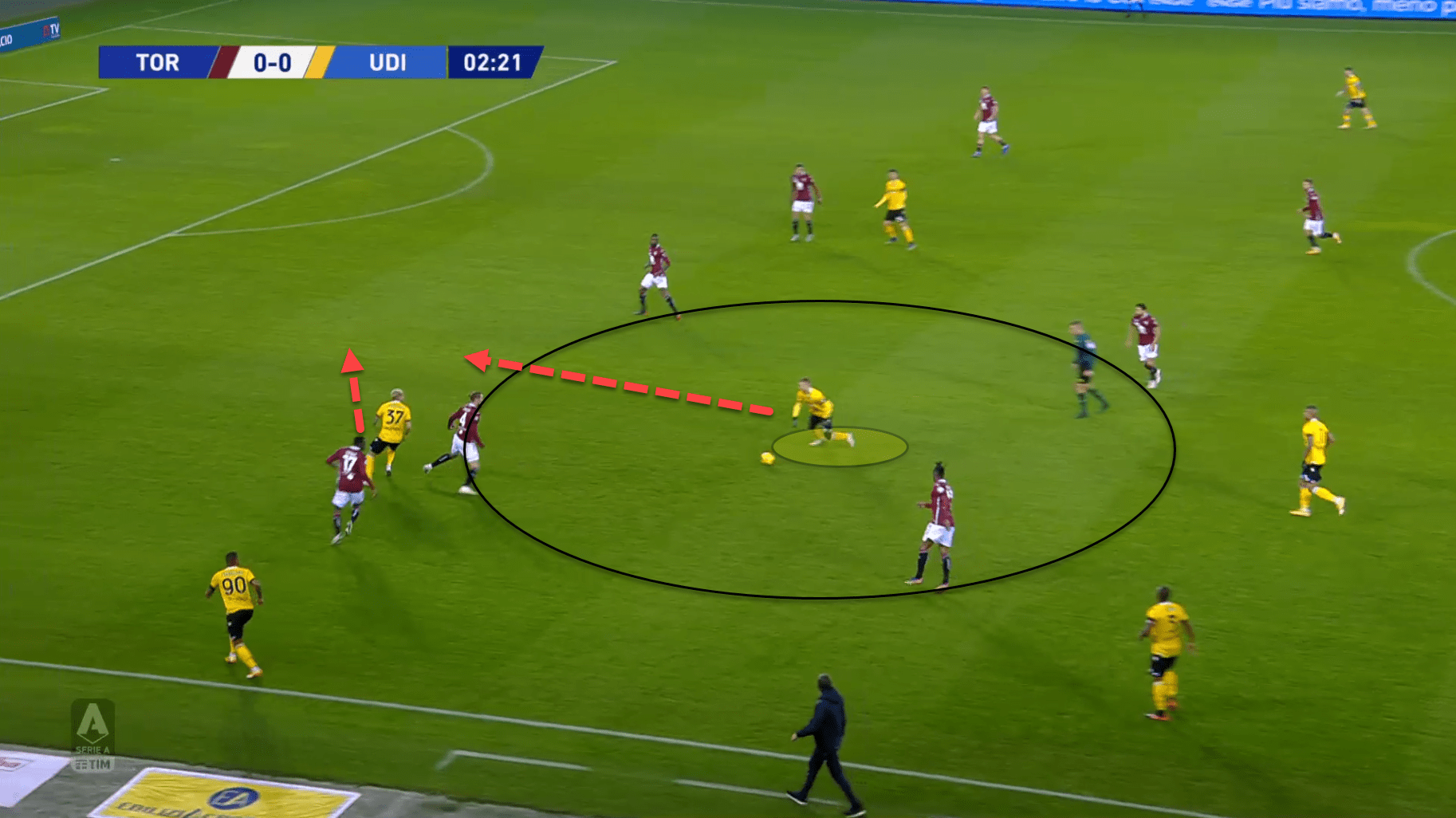

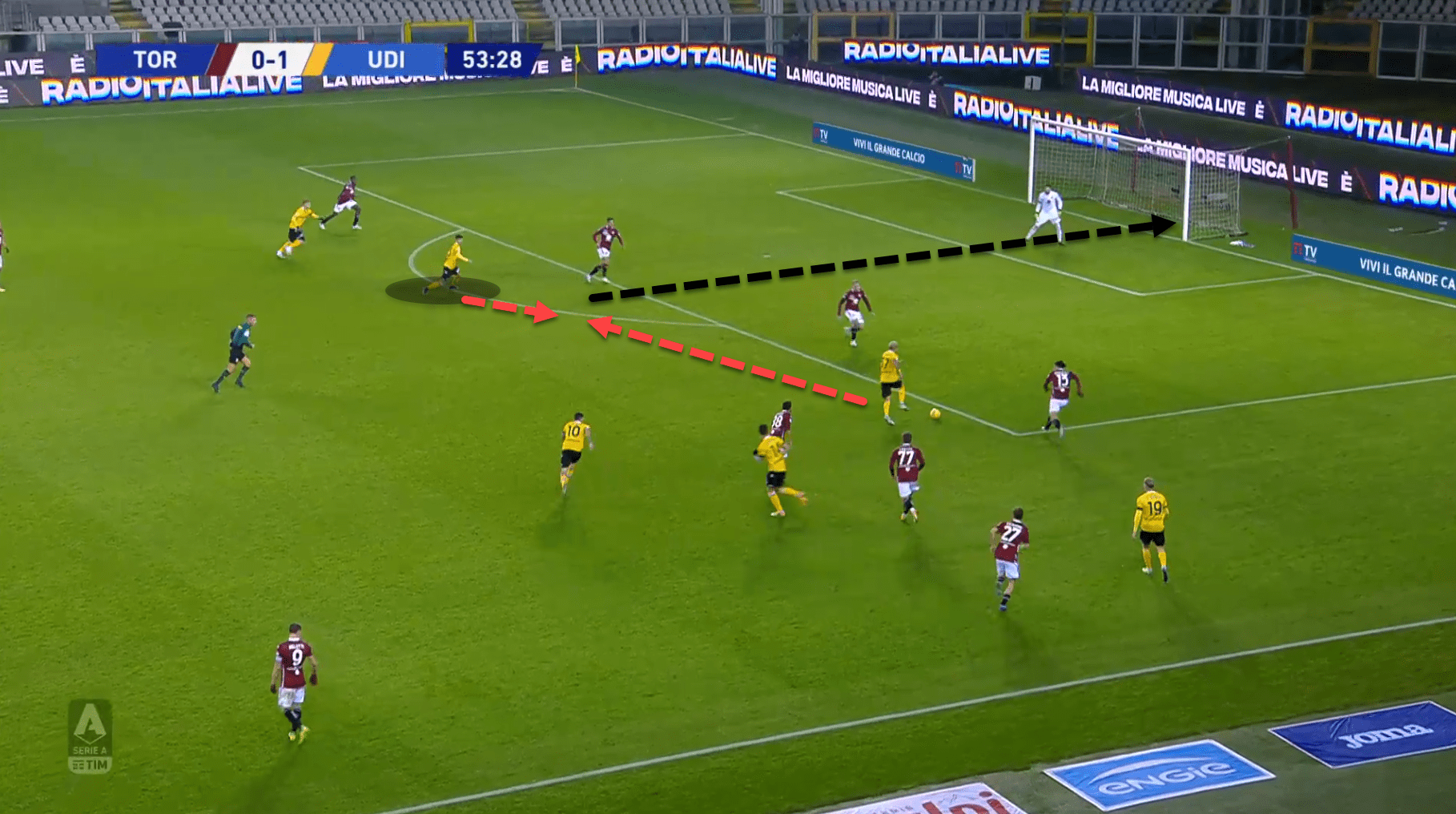

Here is an example of Torino failing to compact the space between the lines. The Udinese player has received the ball in this area and is given plenty of time and space to open out his body and pick a pass to one of his teammates running in behind.

Playing through Torino has been far too easy for teams this season because of structural problems like this despite using a low block, hence the reason they have conceded so many goals.

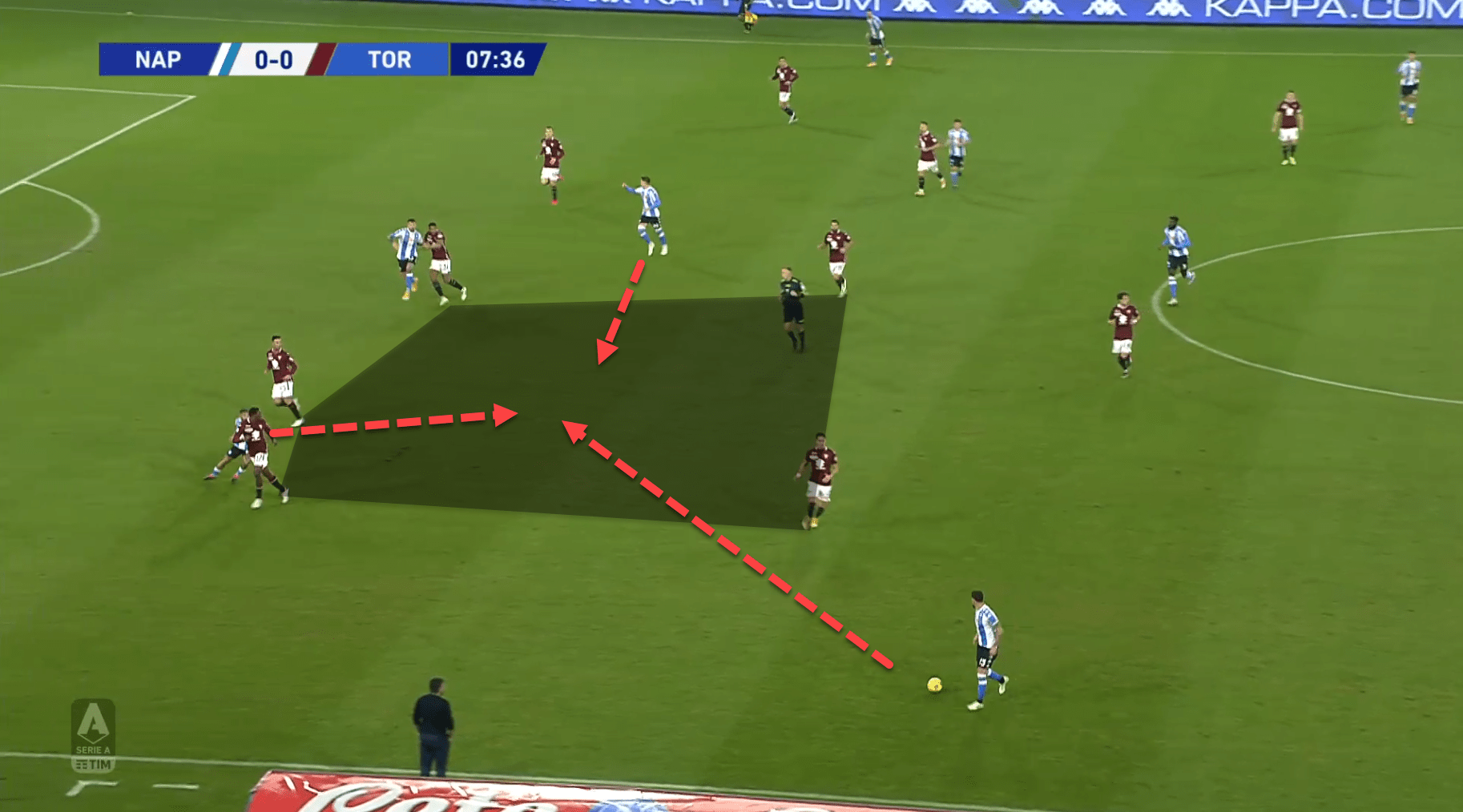

Another scenario where Torino allow the opposition to have far too much time and space in between the lines can be seen above. Two Napoli players dart to move into the space which has opened up for them in front of Il Toro’s backline, and in these pockets space, creative players are their most dangerous, which is why it is so important to compact the space in between the lines.

Saving the best until last, Udinese have once again managed to break through Torino’s midfield and find space between the lines. The ball-carrier in this area cut the ball back to the edge of the box before Rodrigo De Paul struck home to make it 2-0. Another example of their structural failure to compress space between the lines, costing them a goal, and ultimately three points.

Conclusion – Where should Torino actually be?

In conclusion, having analysed their structural problems within the team’s tactical set-up, we will now take a look at where in the Serie A table Torino should actually be, in order to find out whether or not Giampaolo’s side are performing as badly as their league position says.

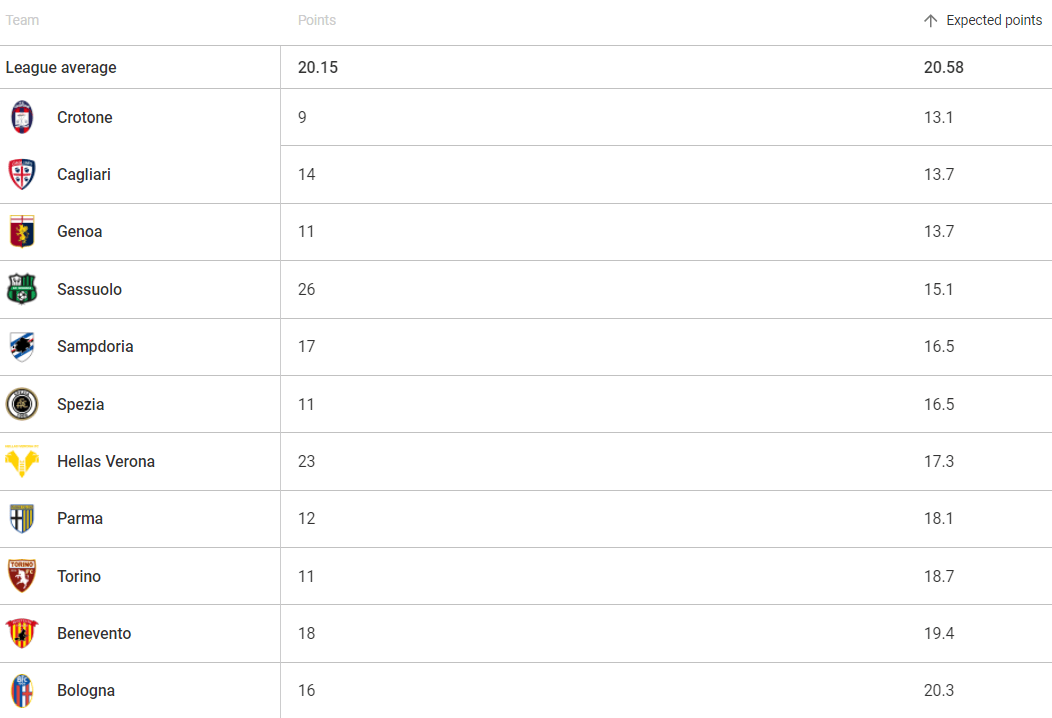

To do so, we will take a look at their expected points and compare with the rest of the teams within the Italian top-flight division. At first sight, by looking at Torino’s metrics, particularly in defence where they only have an expected goals against (xGA) of 24.48, compared to their actual 32 goals conceded, it would seem that perhaps Torino are lower down the table than they should be.

Torino boast an expected points total of 18.7, meaning they are severely underperforming their metrics this season and should be much higher in the table, as they are 17th as of writing with merely 11 points. Keeping the table as is, 18-to-19 points would see Giampaolo’s team bumped up to 12th in the league table, a much more respectable position.

Compared to the rest of the league on expected points, they would be 11th, which is even better, as can be seen from the table below.

Clearly, the structural problems analysed in this article are to blame for Torino’s underperformances, however, this can be fixed with an improved tactical set-up and potentially new faces in the now-open January transfer window. In the end, a better second half to the season may see them finish in mid-table as the statistics suggest.

Comments