As the 2019/20 European footballing season came to an end, clubs evaluate their season and look where to improve their team in order to perform even better than the season before.

Royal Antwerp is no exception.

After three years, The Great Old decided to part ways with László Bölöni.

This decision came because of a difference of opinion about the playing style, although the results did back the Romanian coach.

Under Bölöni’s guidance, Antwerp finished the past three consecutive seasons in eighth, sixth and the last season they finished in the fourth position, giving them a chance to compete in the Europa League.

By no means does this tactical analysis look to disrespect the work Bölöni has done in his three years at Antwerp.

In fact, one could only applaud the Romanian’s work.

This article gives an insight into Bölöni’s philosophy, tactics and how, with some tweaks, he still could convince the board of Royal Antwerp to have kept Bölöni as head coach at The Great Old.

Where to start

In order to create a purposeful training strategy, we have to analyse the team’s performances with a neutral observation.

The observation has to include all actions of the game that will happen through analysing the actions by speed, position, moment and direction.

As per Adin Osmanbasic describes, in his webinar about positional play, these actions as: protecting the ball or winning the ball back, passing the ball or intercepting passes, offering or blocking passing options and reducing opponent’s cover or covering a teammate.

This definition will give us a good indicator of Bölöni’s football philosophy.

The order we will do this is by firstly analyzing Royal Antwerp’s strengths and weaknesses in and out of possession.

After that, we will look at where they could improve to take them to a team that the Antwerp higher-ups agree can compete for the title.

And lastly, we will look at some training exercises to implement this philosophy.

Note I will not be able to discuss every game phase in detail because of the length of this piece.

Therefore I will point out the key aspects of The Great Old’s game.

Build-up structure

Thus the reason the club and coach parted ways was because of the direct playing style.

Bölöni prefers his centre-backs to use long passes to find Dieumerci Mbokani up top.

He will then lay it off to a player surrounding him in order to progress to the opposing goal.

To create these long pass opportunities, the centre-backs providing them, need free space to play them.

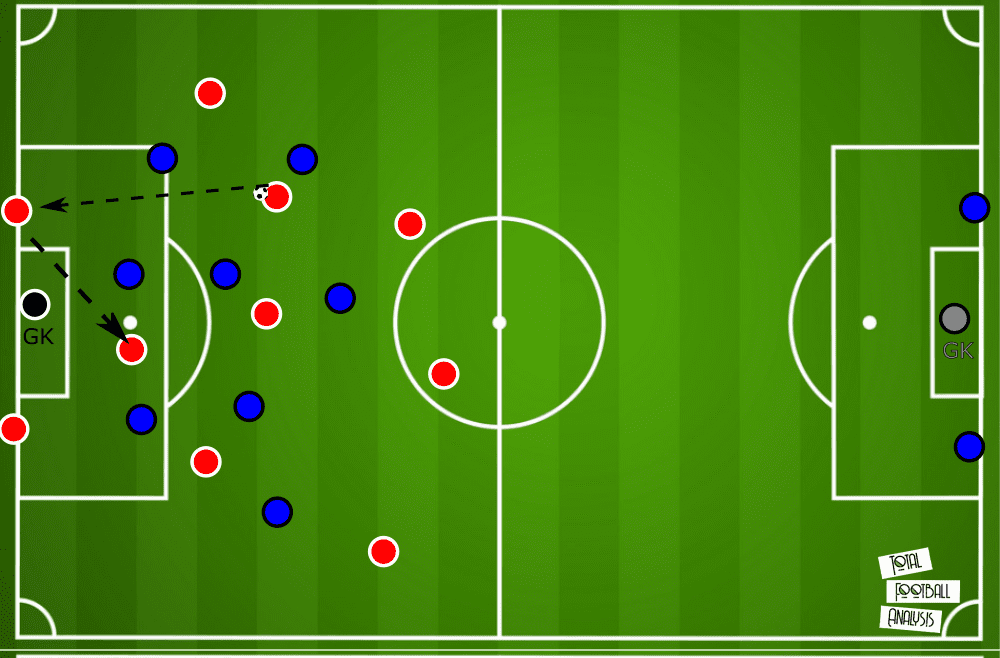

The structure Royal Antwerp use differs a lot when building from the back.

Because of the rotation between different structures, it’s a waste that they don’t opt to combine their way through.

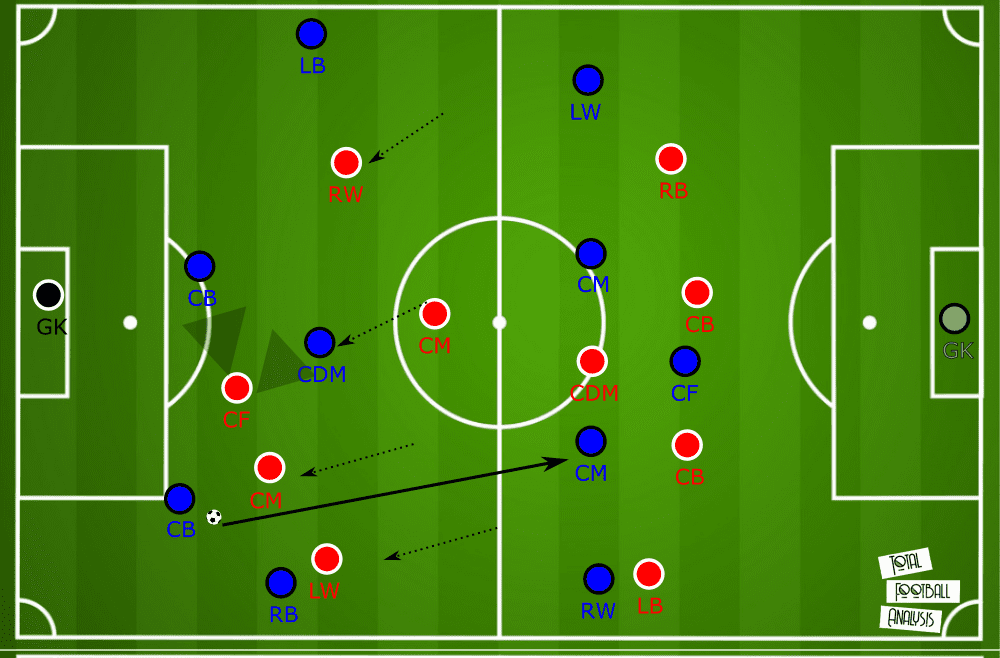

The basic shape Antwerp lineup in during the possession phase is the 3-1-6 formation.

The 3-1 building shape consists of two recognised centre-backs and one dropping midfielder or a full-back moving inside.

In the case below Steven Defour or normally Ritchie De Laet would form the three man line.

The idea is to create a numerical advantage against the opposing first line of press.

At the same time, the three chain aims to provoke the opponent’s second line to press them.

As a consequence space between the opponent’s lines opens up.

At the same time the full-backs push up higher up the field to stretch the opponent horizontally.

But still stay connected to the wide centre-backs to be able to receive a pass from them.

As for the four remaining attackers, the two inside wingers occupy the space between the lines and use dropping movements to manipulate the opponent’s second line press.

The two strikers pin the opponent’s last line by positioning themselves between the centre-backs and full-backs.

For a more detailed analysis of the 3-1-6 shape, check out my article on Ligue 1 side Lille and their 3-1-6 formation.

A structure used by teams like Bayern Munich and Ajax.

This article can also be found on Total Football Analysis.

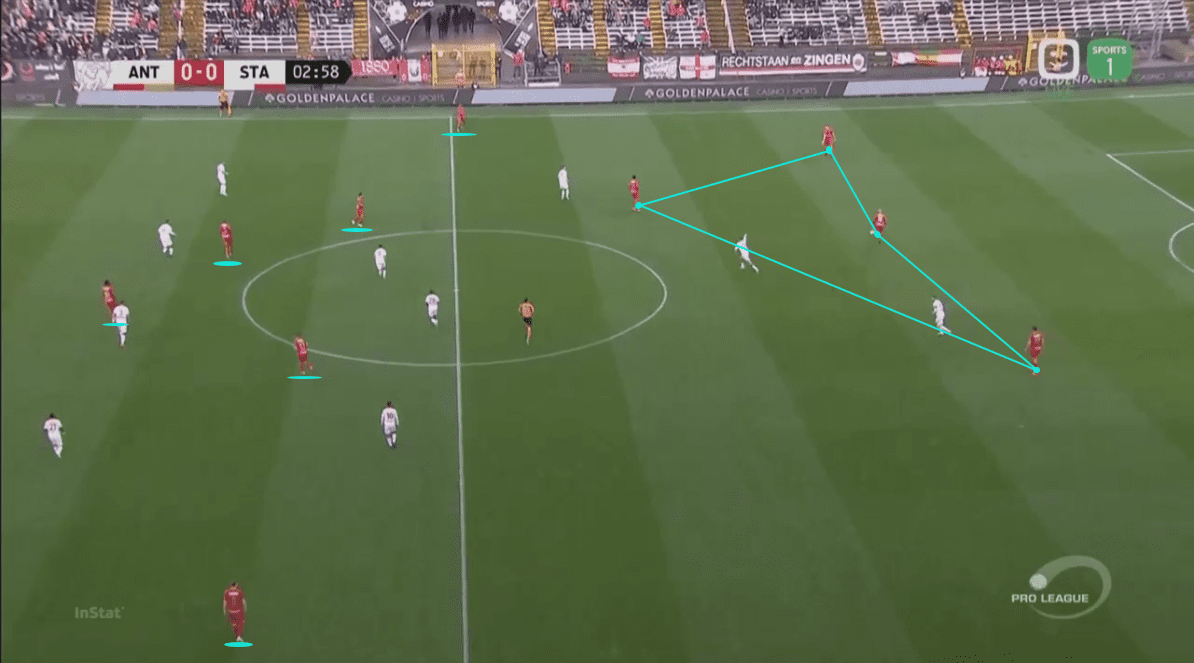

Another variant Antwerp use when building up is illustrated below.

The two recognised centre-backs, former Premier League defender Wesley Hoedt and Dino Arslanagic, are responsible for the central occupation.

Instead of a midfielder dropping into the last line, the two central midfielders stay in front of the two centre-backs.

Subsequently, the full-backs drop deep to receive from the centre-backs.

With deeper full-backs, the centre-backs have another passing option and the opponent has to react to that.

Because of their deeper positioning, Antwerp stretch the pressing of their opponents.

The opposing winger can’t close the half-space and the wing at the same time.

Therefore, Antwerp attract the winger to push higher and lose contact with the rest of the shape.

And a 1v1 situation occurs for the attacking Antwerp winger.

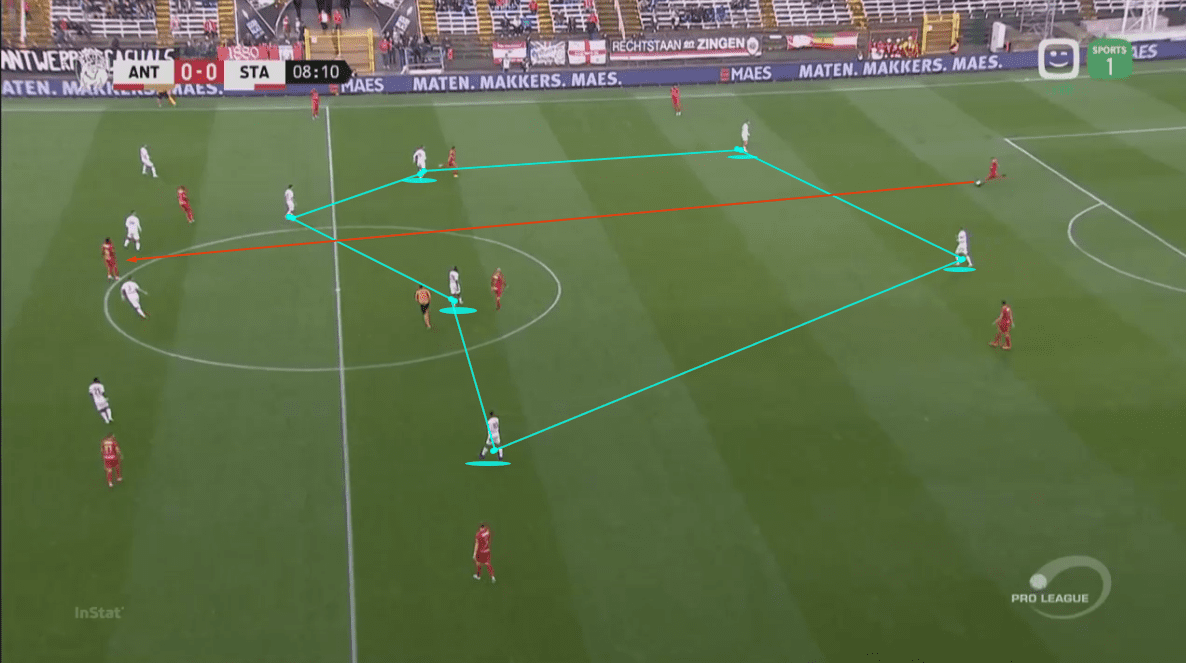

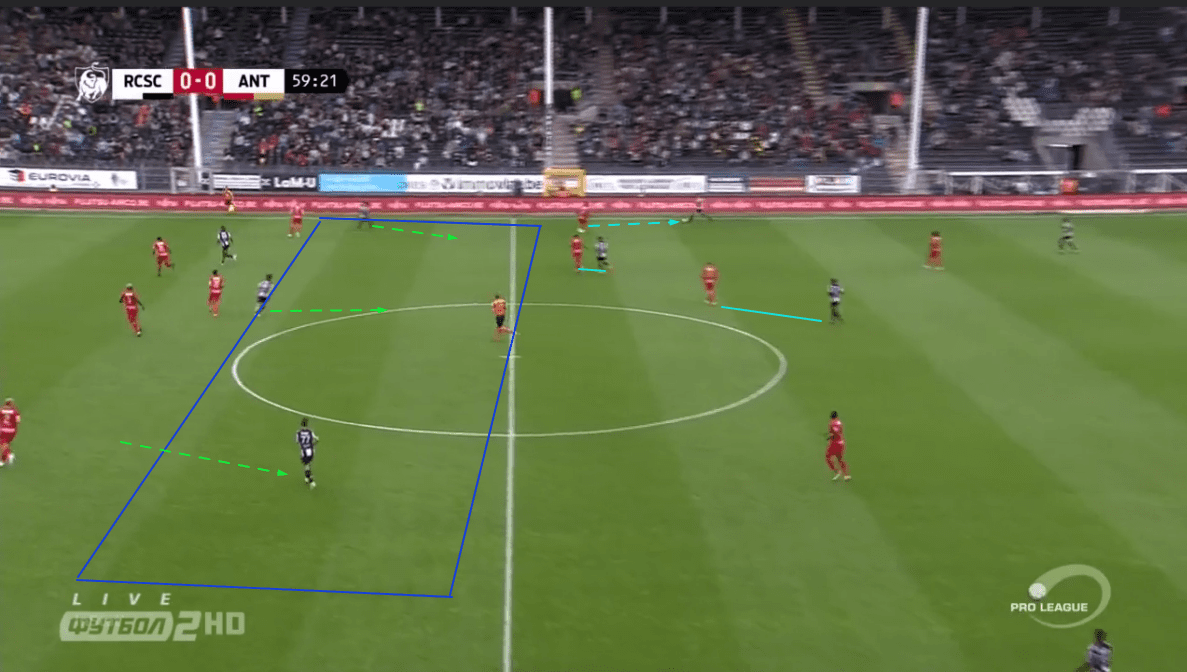

When we take into consideration these creative build-up variants, one could scratch the back of their head when seeing the image below.

Often Antwerp will play the long ball, but in this instance below against Standard de Liège they get a lot of space to build from the back.

This time again they use the long ball.

Standard’s first and second line are stretched during Antwerp’s build-up which gives them the opportunity to progress the ball easily but they opt not to use this option.

As a consequence, the long ball gets lost and turns into possession for Standard.

Runners in behind

As discussed above we will look at their strengths.

One of these strengths is exploiting the space behind the opponents’ last line with ease.

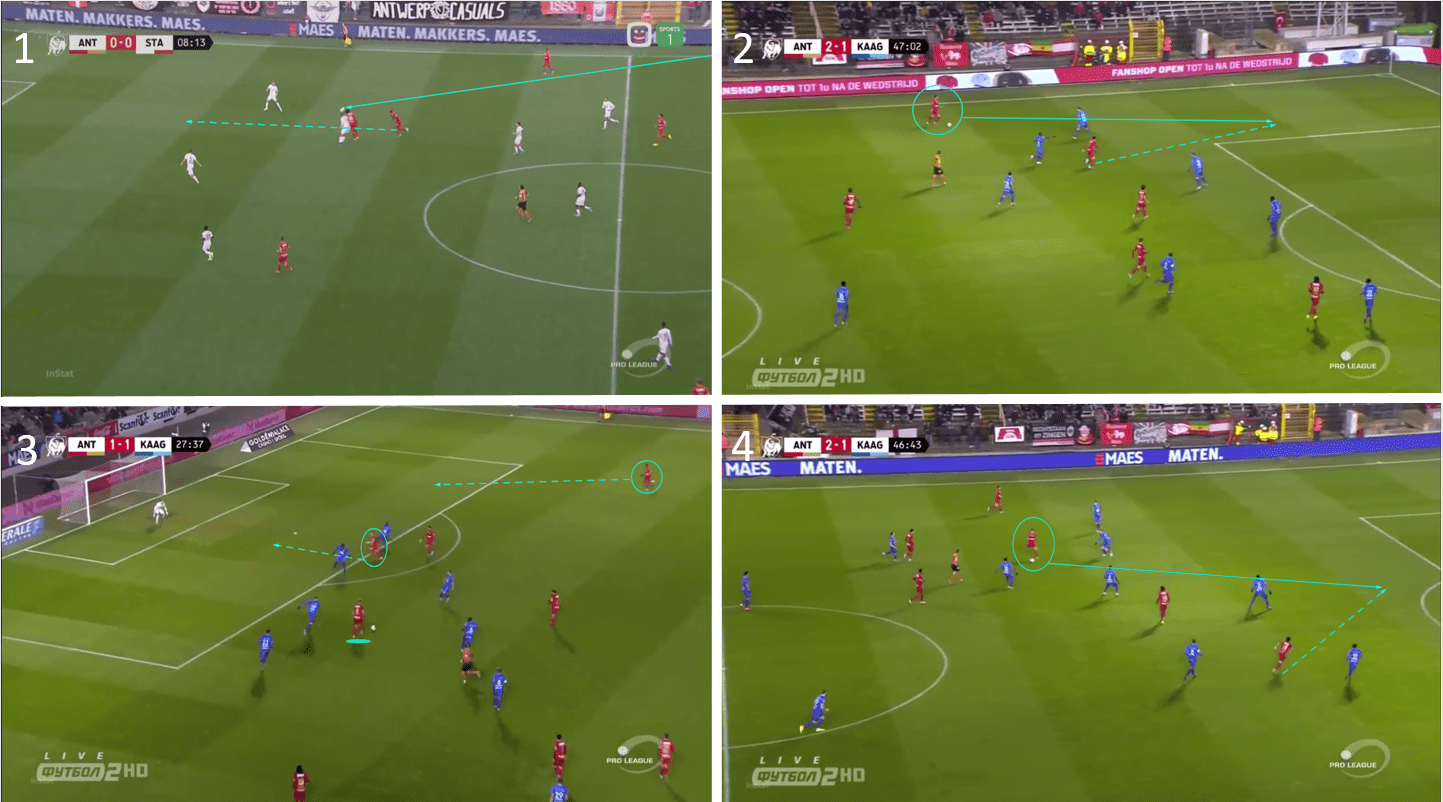

Bölöni uses four basic principles to find space in behind the opponent’s last line.

The first principle is the most used by Bölöni’s men and is shown in the top left image.

When the ball is played long to Dieumerci Mbokani, in this case, Lamkel Zé looks to run onto the second ball.

When the Congolese striker attempts an aerial duel, the opposing defender steps out to compete for the high ball and the other defenders cover him by falling back.

Consequently, space opens up behind him.

This space is exploited by the runners in behind.

The second principle occurs when the ball is in Antwerp’s attacking third and can be seen in the top right image.

Once the ball is played outside to the player who is providing width, he will be pressed by the opposing full-back who normally steps out to the ball-carrier on the outside.

As a result, the channel between the centre-back and full-back widens up.

This triggers the player in the ball side half-space to penetrate and receive the ball in behind from the player occupying the outside lane.

This concept is also known as an underlapping run.

The opposite can happen as well.

When the player in the half-space possesses the ball, an overlap from the full-back provides the depth.

Especially when switching the play this is effective.

Usually when switching, a 1v1 occurs on the underloaded side.

By making an overlapping run from deep, a 2v1 situation is created to find space in behind.

The third principle is more centrally and is shown in the bottom left image.

When the ball is played to a player between the lines in a more central position, Bölöni asks at least two players to penetrate and try to receive the ball in behind.

This gives the ball carrier enough options to pass too but also gives him the option to dribble himself and use the runs in-depth as a decoy.

And finally, when the ball is located in one half-space, an attacking player has to penetrate from the ball far half-space.

This is effective for chance creation because the run happens from the defenders’ blindside and completely disrupts the opposing defence as one has to follow the run from the half-space.

This principle is illustrated in the bottom left image.

Lamkel Zé in his best position

We can conclude that Antwerp’s strength is exploiting the space in behind with various runners in depth.

Because of this obvious strength, I would like to sharpen this onto our new approach.

The most common way to find space in behind for Antwerp was through a long ball to Mbokani and a supporting player competing for the second ball in order to exploit the space in behind.

The change that I would like to make is using Lamkel Zé as a more vocal point of the passes in behind.

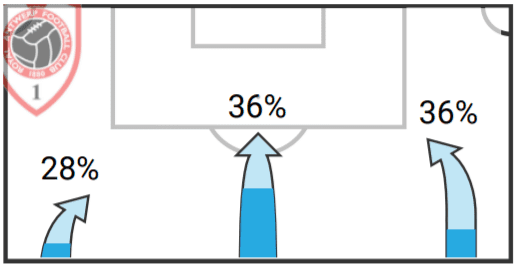

In the below image we can see Antwerp’s attacks by flacks.

Through the centre and down the right-hand side are the most used and evenly shared.

Which makes the left side underused.

This can seem like a surprise as star player Lamkel Zé mostly operates down the left.

Especially when we take his solo goal against Club Brugge into consideration.

But when we look closely at Royal Antwerp’s attacking play, it clarifies why most play is done down the other vertical thirds.

The image below clarifies it.

Mostly Ritchie De Laet, the left-back, has to provide the width down the left.

This means that the left outside lane is occupied by a player better defensively than offensively.

Below De Laet is responsible to exploit the space in behind the opposing full-back down the left.

This brings him into attacking situations.

The image is taken from the game against KAA Gent, during this game De Laet had three offensive chances to score because of his penetrating runs down the left.

All of these three chances went begging because of the lack of finishing qualities.

Another reason why the left side is underused is that Bölöni likes to build Antwerp’s attacks through wide overloads and dynamic rotations and not so progress down the flanks.

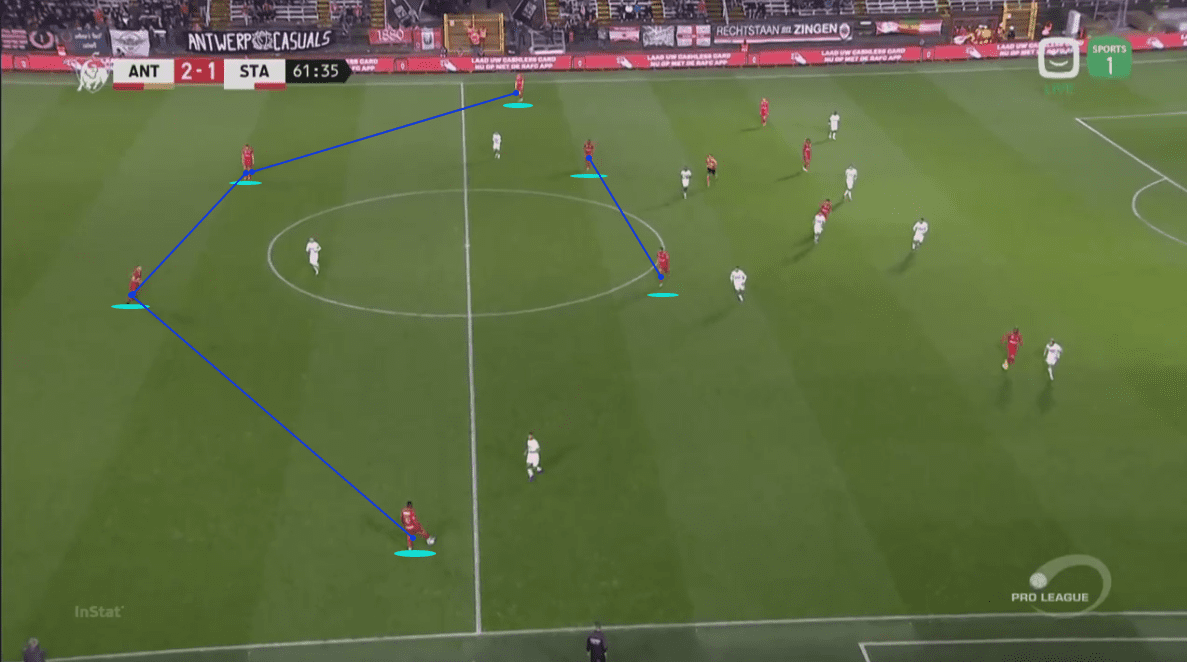

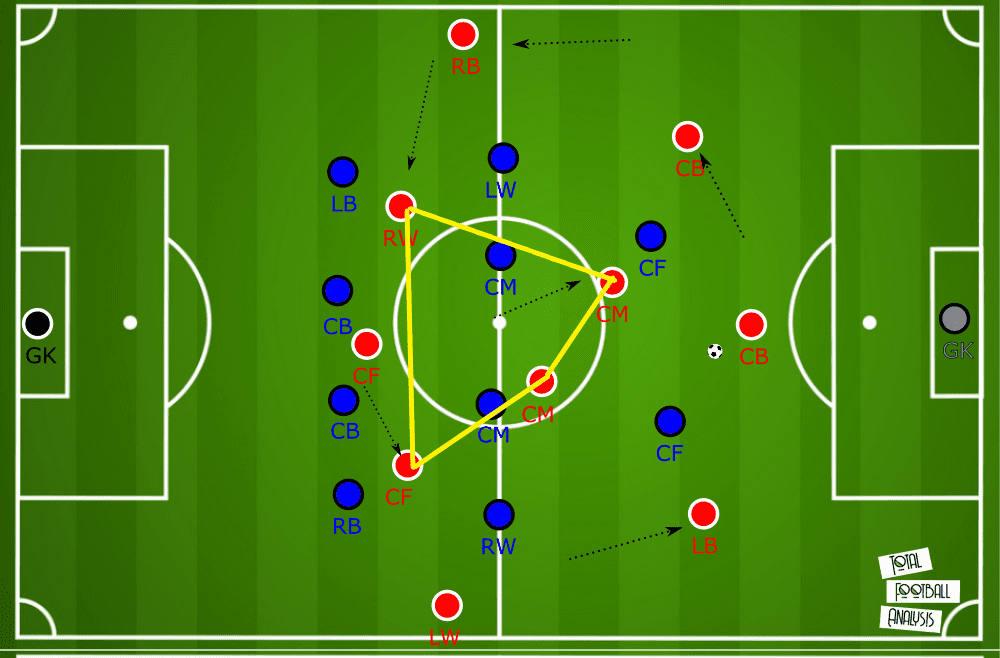

The image below shows how The Great Old try to create an overload down the left by forming a diamond shape.

When opposing teams shift their block quick enough, the overload down the left gets nullified.

The dynamic rotations down the side help to find space if teams nullify the numerical superiority.

Below Mbokani moves to the half-space to form a diamond with the wide Lamkel Zé, the inside Lior Refaelov and at the base De Laet.

De Laet is trying to start the dynamic rotations by penetrating into depth.

This eventually leads him into a position attacking the space in behind the opponent’s backline.

Again, the player whose qualities obviously stand out in defence has been put in an offensive situation.

Thus my idea is to isolate Lamkel Zé down the left in a 1vs1 against the opposing full-back.

A common strategy to find space in behind could be through his dribbling skills or making runs in behind without the ball.

An effective passing sequence could be the out-in-out sequence.

As the midfielder plays a pass into the inside winger, who attracts the opposing full-back., the winger lays off to a third man midfielder.

Which on his turn passes in behind to the left-winger, Lamkel Zé, in open space.

Midfield box

As seen above Antwerp use wide dynamics and long passes to create chances.

We also discussed how I would like to isolate the Lamkel Zé on the outside.

Consequently, the centre has to be overloaded in order to create combinations and shifts to the flanks to then eventually create scoring opportunities.

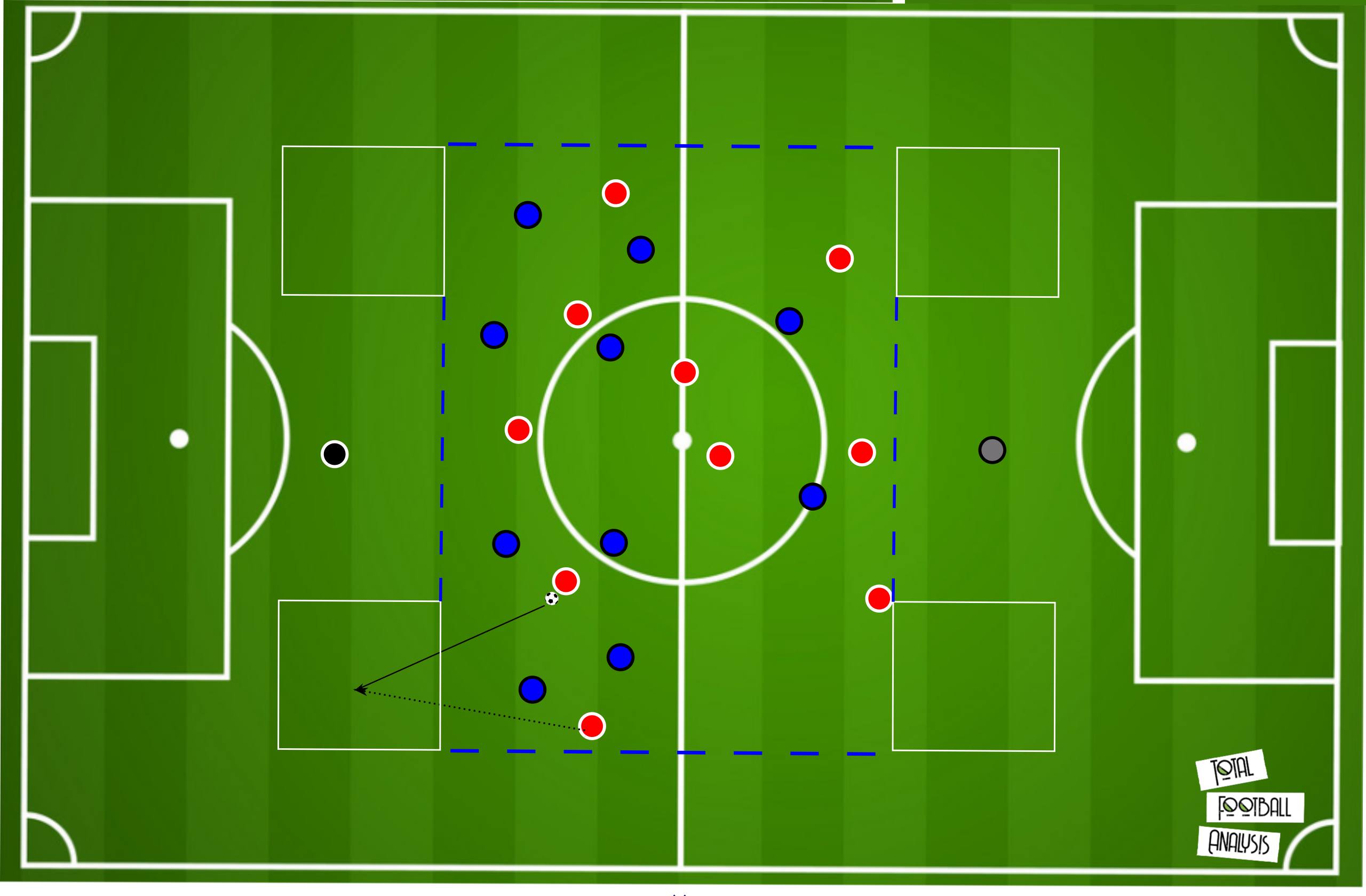

Therefore to overload the centre, a midfield box can facilitate this.

The midfield-box exists of a 2-2 staggering and has an effect on the oppositional 2de line.

Differing in staggering can have an intriguing effect on the opponents’ defensive block, for example, a 1-3 staggering has different consequences than a 3-1 staggering.

Thus the different staggerings have different effects to manipulate the oppositional structure with a higher emphasis.

When overloading the centre, it will have effects on the defence of the 2nd line, whilst overloading the last line will again create a different effect.

Of course dependent on which staggering is applied.

In order to have optimal dynamics, the midfield-box has to consist of some principles.

Firstly the two central midfielders have to position themselves in front of the opponents’ second line.

The attacking midfielders have to position themselves higher, behind the 2de line and in between the lines.

With the central midfielders operating more in the centre and the attacking one’s slightly to the half-spaces on the outside of the opposing midfielder’s shoulders.

This opens up more passing lanes and keeps the passing option to the striker open.

Also, the doubling up of the centre-midfielders causes a decisional-crisis for the opposition second line.

This results in more penetrative actions from the 3 central zones, exactly what suits Antwerp’s playing style.

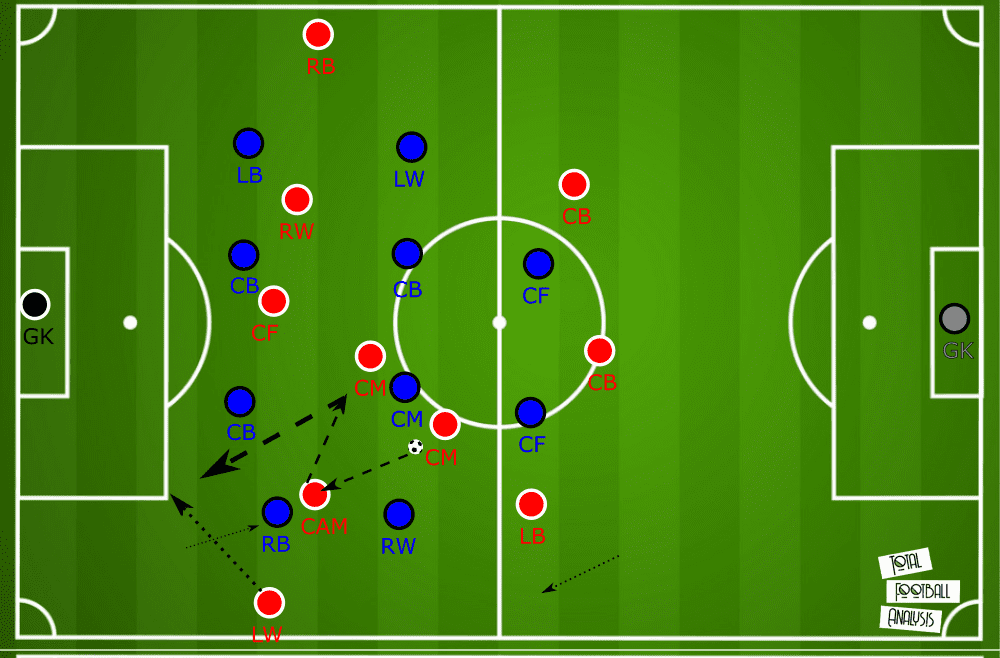

Thus far we narrowed down a more suitable playing system to the style we want to implement.

The image below shows the system with common movements to create this system.

Vertical play

As discussed above the board would like to see a team that looks better on the eye.

This argument refers to the rather reactive approach Bölöni has to the game.

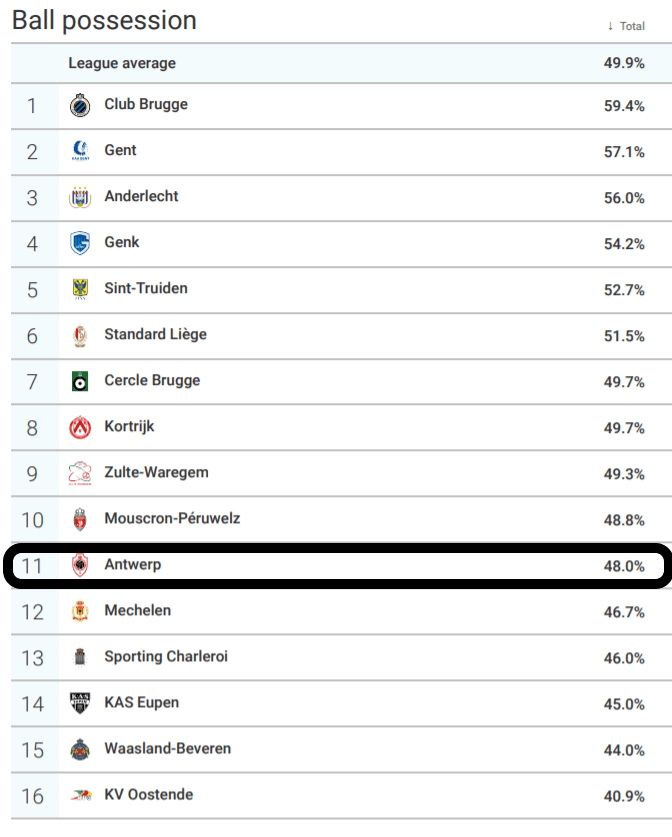

When we take a look at the season’s overall possession stat below, it clarifies that Antwerp isn’t a possession-based team with 48 per cent possession on average this season.

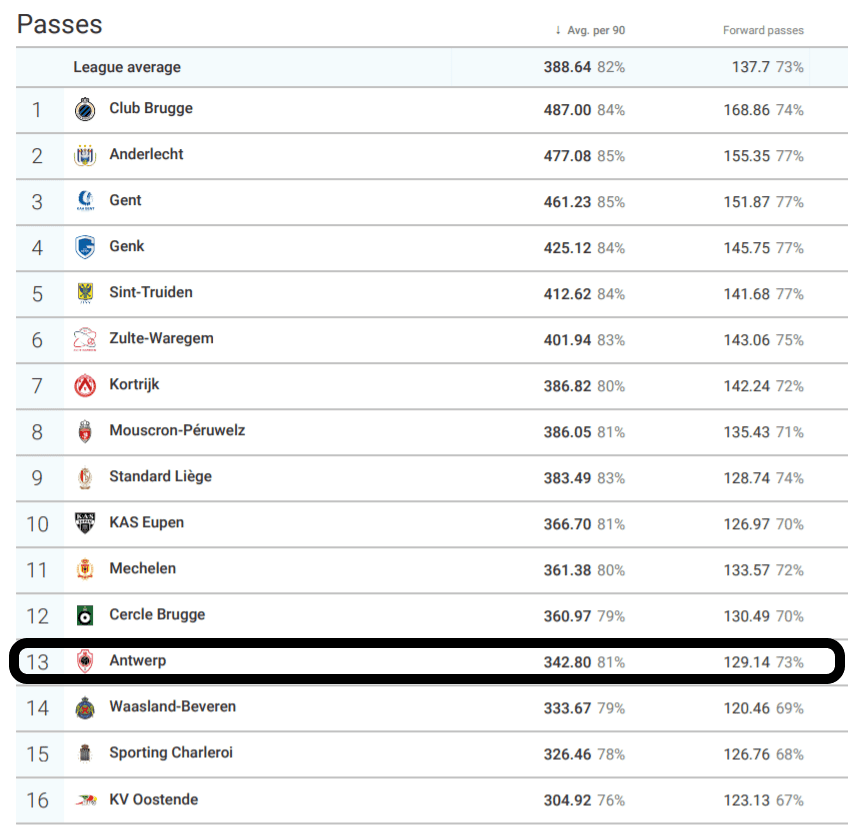

Now, if we move on to how they utilise the ball we can see that in relation to the possession, Antwerp end again closer to the bottom of the table when it comes to the number of passes they make on average per game.

When we look a little more in-depth to the composition of these passes, one specific kind of pass catches the eye.

From the 342,80 passes they complete on average per game, 129,14 are forward passes, indicating Antwerp use more lateral passes and look for the right moment to play a long pass.

As an assistant coach and in order to sharpen Bölöni’s tactics, one cannot expect a change in philosophy.

One cannot expect Antwerp will change into a possession-based team like the Barcelona team under Pep Guardiola.

In order to bring a ‘more exciting brand of football’, we will look to keep Bölöni’s successful direct approach.

But we will tweak it to a vertical play approach where the ball doesn’t leave the ground.

Roger Schmidt, current PSV manager, explained in the past to be a huge fan of vertical play.

One of the risks of vertical play is that the receiver has less of a viewing field.

And the risk to lose the ball increases when the receiver of the vertical pass is outnumbered by the opponent.

This is why Schmidt emphasizes playing vertical passes into crowded areas with players in support.

If they lose the ball in a crowded area, it is more likely they can win the ball back because the counter-press opportunity arises.

So if we want Antwerp to change their possession approach to a vertical one, we have to also have a team good in counter and high pressing situations.

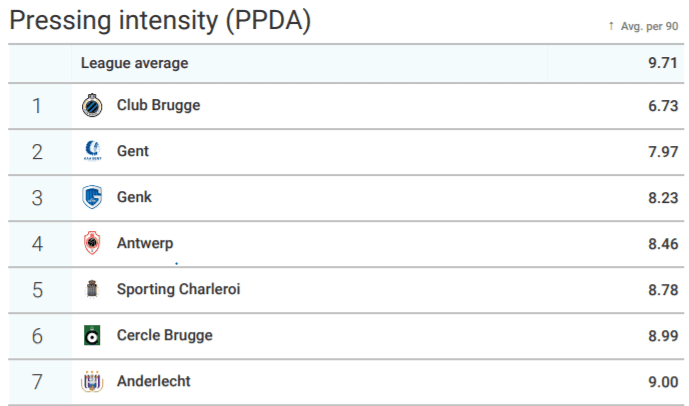

The data suggests Royal Antwerp operate using an intense press to win the ball back as quickly as possible once they lose it.

They have a PPDA, lower than the league average, at 8,46.

Which indicates they are a team with a counter-pressing identity.

Below them is Vincent Kompany’s Anderlecht, who has undoubtedly taken the counter-pressing principles of Guardiola, in his time at Manchester City.

This underlines how impressive their pressing game out of possession phase is.

Pressing system

Thus high pressing is in Antwerp’s DNA.

This pressing system made them concede the fourth-least goals in the Belgian Pro League during the 2019/20 season with only 32 goals.

The pressing system played an important part.

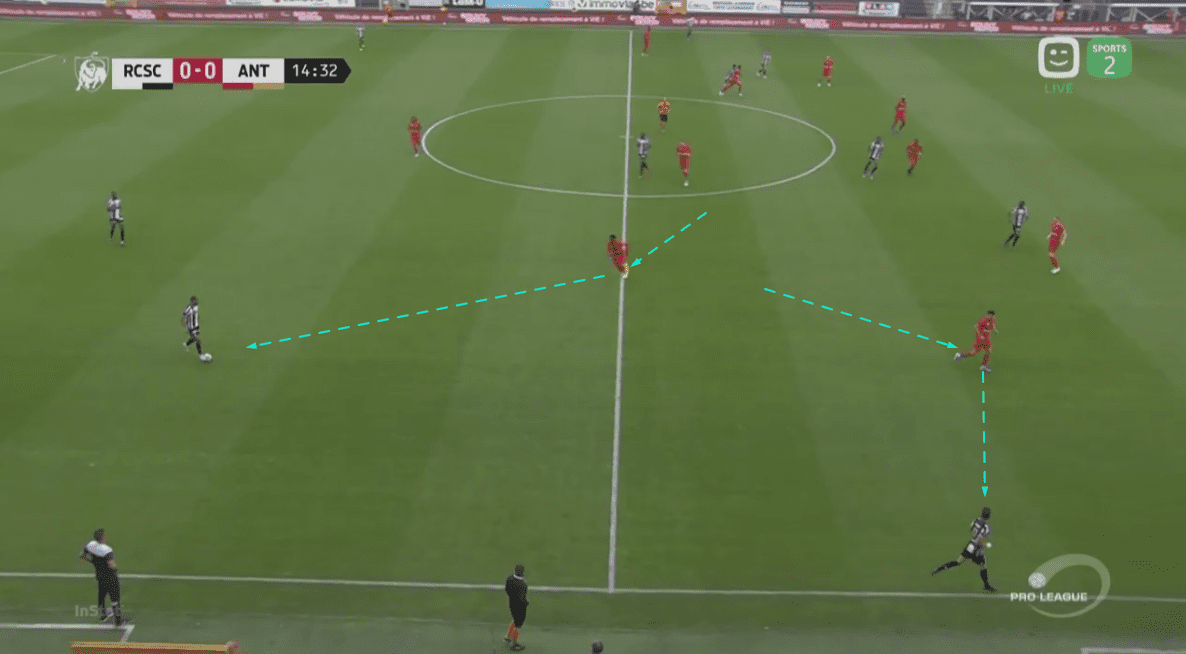

The below image shows how the centre midfielder is triggered to step out and press the ball carrying centre-back.

The left-winger closes down the ball side full-back as the centre-forward closes any passing options to the pivot.

But when the centre-midfielder has come close to the pivot, the striker closes the pass back option to the centre-back.

As a result space between the lines opens up.

Which gives the opponent an opportunity to create a superiority against the last line and receive in open space.

The obvious solution is to keep the lines closer to each other depending on good team level communication and courage to leave space in behind open for the opposition to exploit.

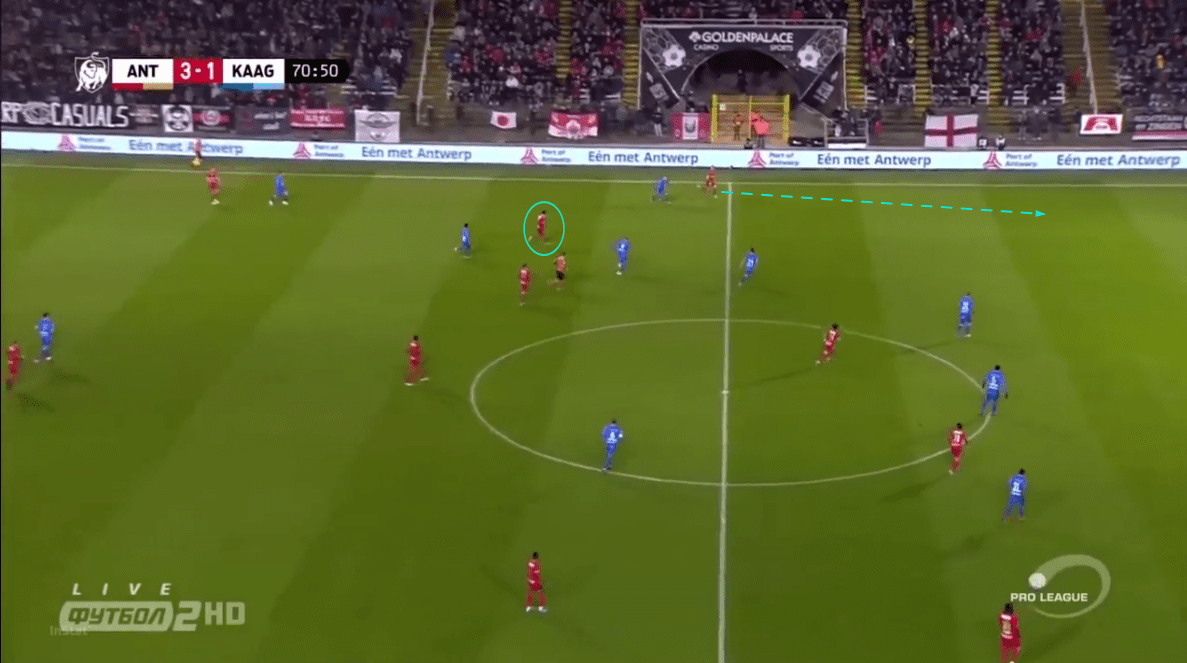

Below an example from the game where Antwerp is triggered into pressing and the space that opens up between their lines.

The opposition use dropping movements to exploit this.

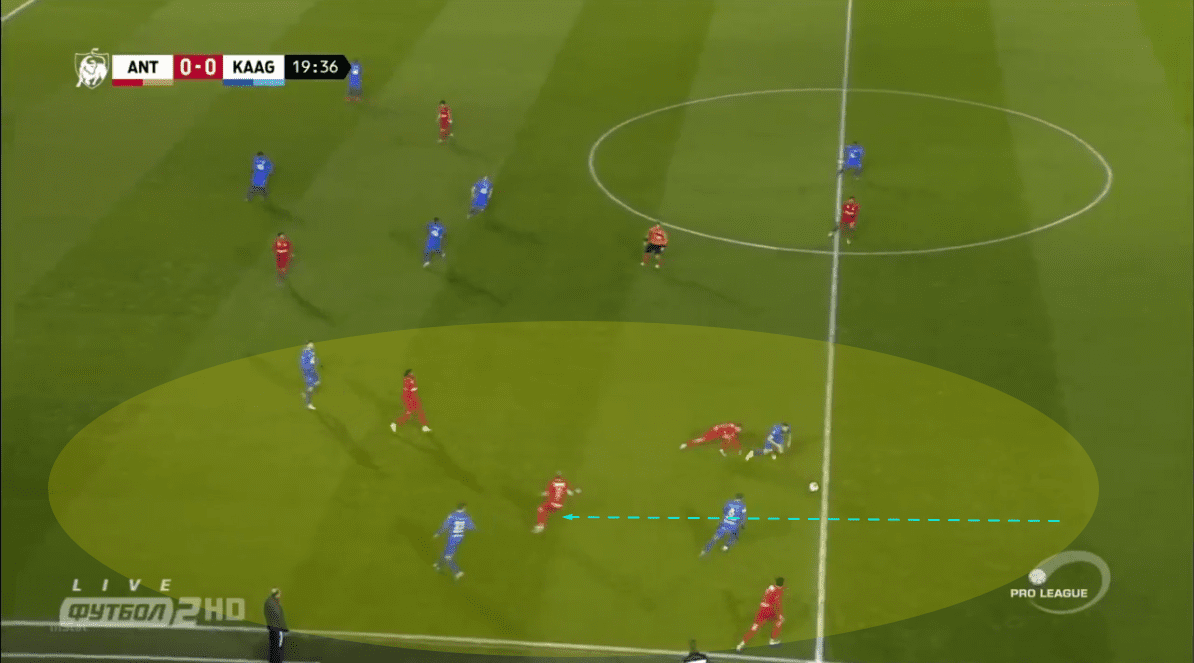

On the other hand Antwerp try to push the opposition down the sides if they can’t win the ball back during a high pressing situation.

Below a good example of wide defensive rotation.

Here the centre-midfielder steps out to press the ball carrying centre-back which allows the winger to track the opposing fullback’s run.

The fact that the centre-midfielder steps out nullifies any wide overload by the opposition, if they would attempt one of course.

Another point worth noticing is Lamkel Zé’s wide position on the far side.

Normally a coach would ask his team to stay compact and reduce spaces centrally.

Bölöni asks this but Lamkel Zé’s is an exception.

The winger stays wide to keep out any switches of play.

(Image 15)

Back to the drawing board

As mentioned earlier we will look at some corrective exercises that look to put the new beliefs into practice.

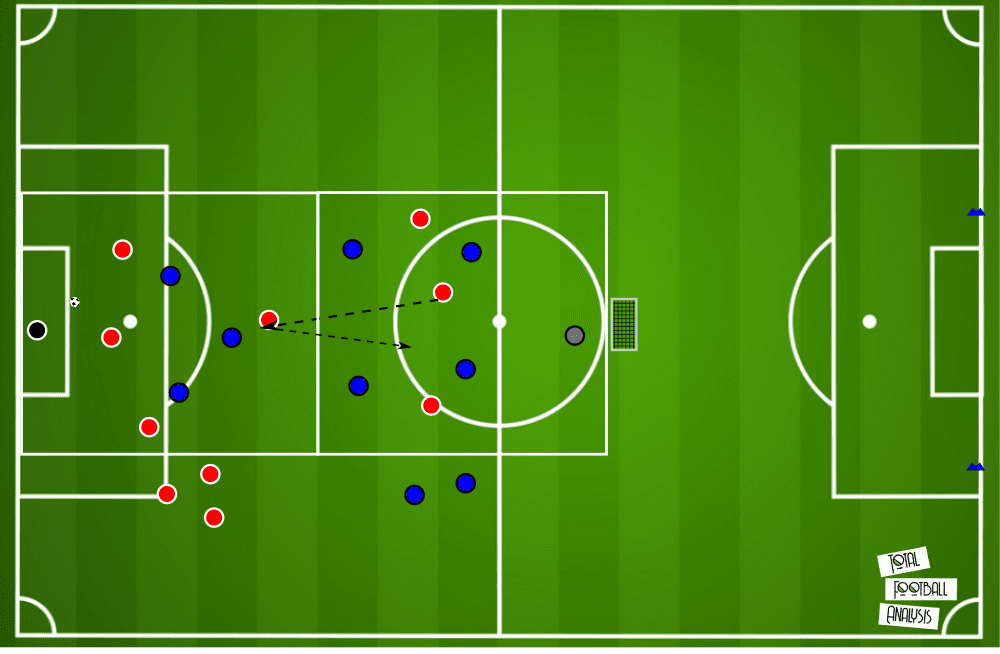

Exercise 1: Finding space in behind the full-backs/Isolating the wingers and overloading the centre.

The first exercise mainly focuses on exploiting the space behind the full-back and to isolate the wingers in the outside lane.

The practice is played between 10 outfield players in a 25x45m rectangle.

The goalkeepers play the ball to one of the centre-backs once a point is scored or the ball goes out of play.

A point is scored if someone can receive the ball in one of the two 15x15m boxes without running offside. 4 sets of 5 minutes are performed, with 60 seconds of recovery after each set.

Exercise 2: vertical play game

To encourage vertical passing during the game, a GK+(8+2)vs(8+2)+GK game is played on a 40x30m pitch, in which each team has 2 offensive supporting elements placed beside the opponent’s goal.

The players can only touch the ball 3 times at most and the goal is only valid when there is a first-time shot.

The goal is doubled if the last pass comes from one of the offensive supporting elements and is trebled if the ball, immediately after being recovered, is immediately played, using a vertical pass, to a supporting offensive element, who then assists a teammate to score.

5 sets of 3 minutes are performed, with 30 seconds of recovery after each set.

Exercise 3: building from the back and encouraging vertical passes

This game looks to improve attacking build-up from the start zone by playing over with vertical passes if possible. The red team builds with four players and the goalkeeper against 3 pressing blue players (5v3).

If they win the ball they can score in the goal.

The red team has to get X passes to be able to play in the second, higher zone.

Position exchanges are allowed in order to obtain this.

Once played vertically a red player can enter the second zone, creating a four versus four.

The zone switch encourages vertical passes due to the narrowness and to support the lay-offs after the vertical passes, the penetrating player enters the second zone.

If needed add an outside lane allowing wing-backs to create an even heavier overload in the position phase.

Conclusion

After three years of exceptional work by Bölöni, unfortunately, he had to leave The Great Old.

As most managers have a set of principles and a clear playing style, Bölöni is no difference.

His approach is what made the board rethink his position at Antwerp.

Although I looked to try and tweak some of his principles in this analysis.

Consequently also sub-principles and sub-sub principles have to change and the problem now lies on a macro level.

So, it is very difficult to guarantee success as we are trying to please the external by changing Bölöni’s approach which means the beliefs of the manager, the expert, come less important.

Unfortunately, this is the harsh reality of the football world.

Thus one could only applaud Bölöni’s firm belief in his ideas which did bring him good results at Royal Antwerp.

Comments