The Decline Of 2 Striker Partnerships In Football

The tactical evolution of football has seen a decrease in strike partnerships, particularly at the top level.

Over the years, we’ve been spoiled with iconic Premier League duos such as Dwight Yorke and Andy Cole, Alan Shearer and Chris Sutton, Sir Kenny Dalglish and Ian Rush, Jermain Defoe and Peter Crouch, Thierry Henry and Dennis Bergkamp plus many more.

Around the globe, we’ve seen pairs like Raúl and Fernando Morientes, Marco van Basten and Ruud Gullit, Pelé and Vava, Andriy Shevchenko and Pippo Inzaghi, to name but a few.

The art of a deadly strike partnership seems to be slowly dying at the top level due to the aforementioned tactical evolution of the game, but there are still a few teams deploying formations with two centre-forwards.

This tactical analysis will discuss different tactics and formations in the modern game that use two strikers.

The analysis will dive into three key areas: how they function off the ball and in transitions, their interaction and link-up with the midfield unit, and how they pair together in build-up and attacking phases as a duo.

It is worth noting that the analysis includes teams that have utilised such formations as either their primary or secondary formation in the last calendar year.

For example, Juventus have been deploying a 4-2-3-1 this season but frequently used a 3-5-2 last campaign; we have still included them in the analysis.

Off The Ball & Role In Attacking Transitions

On some level, many teams with two forwards like to defend from the front.

While having an extra forward can, in some formations, mean less of a midfield numerical presence, it allows your team to engage with the opposition early on in a number of ways.

Similarly, having two centre-forwards can be extremely beneficial in attacking transitions.

You already have something of a presence in dangerous areas to begin with, giving the opponent more to react to.

Atlético Madrid are one of the most defensively disciplined teams in elite football.

Their long-time manager, Diego Simeone, along with his team, has garnered a reputation for using the defensive side of the game as the foundation of his tactics, often deploying a 3-5-2 or a 5-3-2 to make life difficult for the opponent.

But even with a defensive focus, he still wants two up top, and that isn’t just to make his team’s possession and attack more dangerous.

That presence up top allows for pressure on the opposition’s backline, which can disturb the opposition’s build-up play, even by a split-second delay.

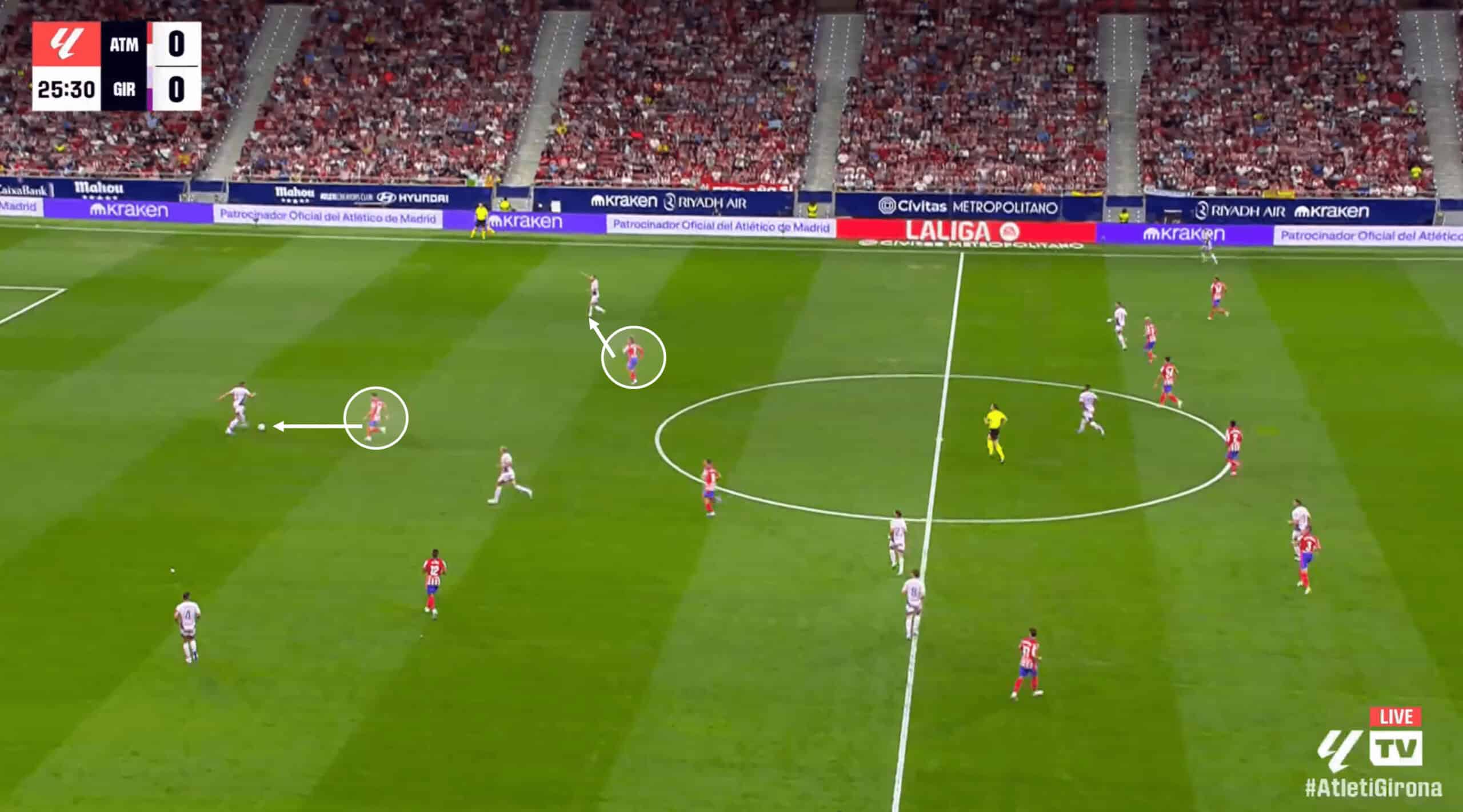

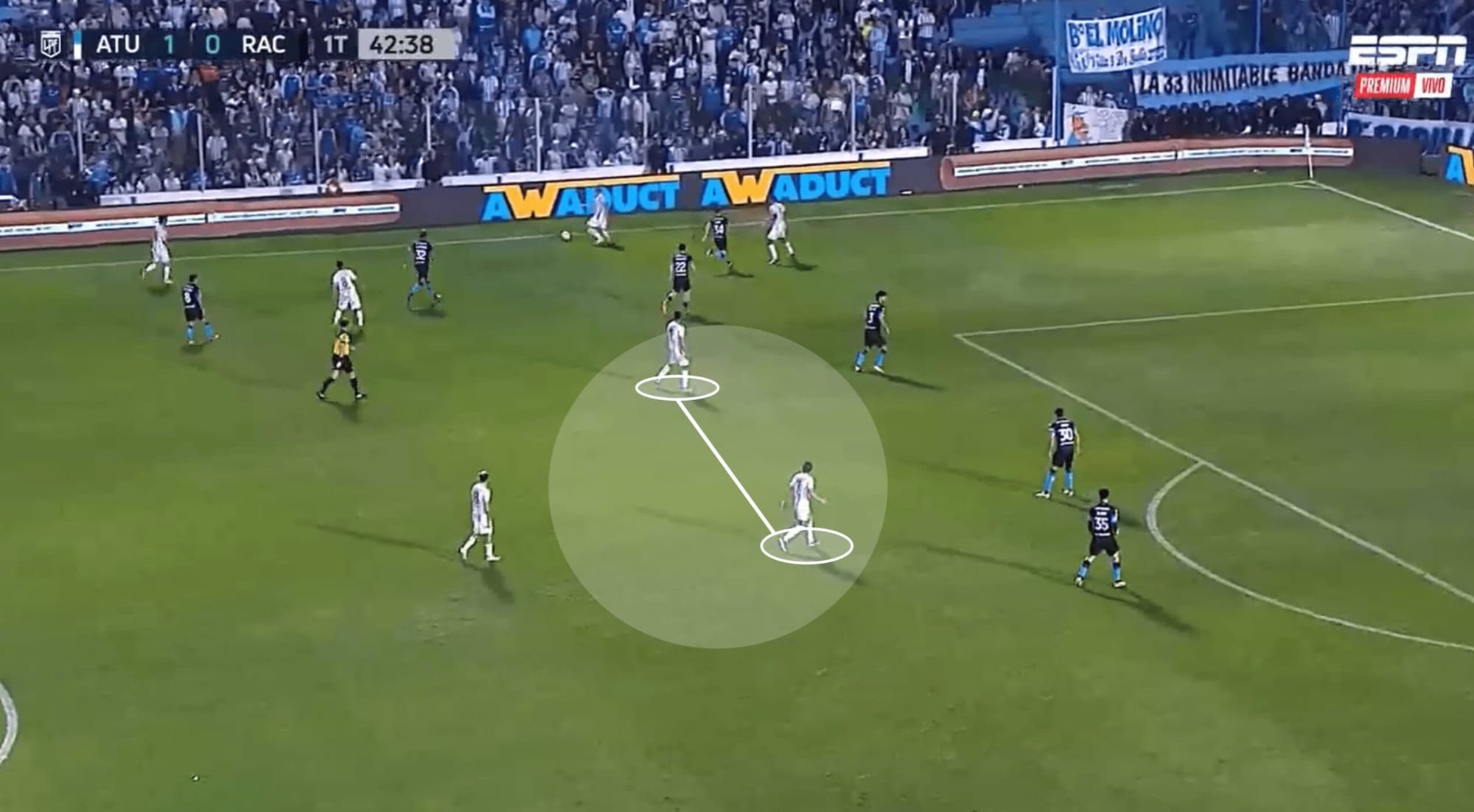

Atlético, often led by Julián Alvarez and Antonie Griezmann this season, work well in this sense, as seen in the image above.

In this case, Alvarez presses the ball at an angle that forces the opponent to focus his efforts in a certain direction.

At the same time, his strike partner Griezmann looks to close the next passing option down, effectively eliminating him as an option.

This is aimed at forcing the opposition into a mistake and, ideally, causing a turnover in possession.

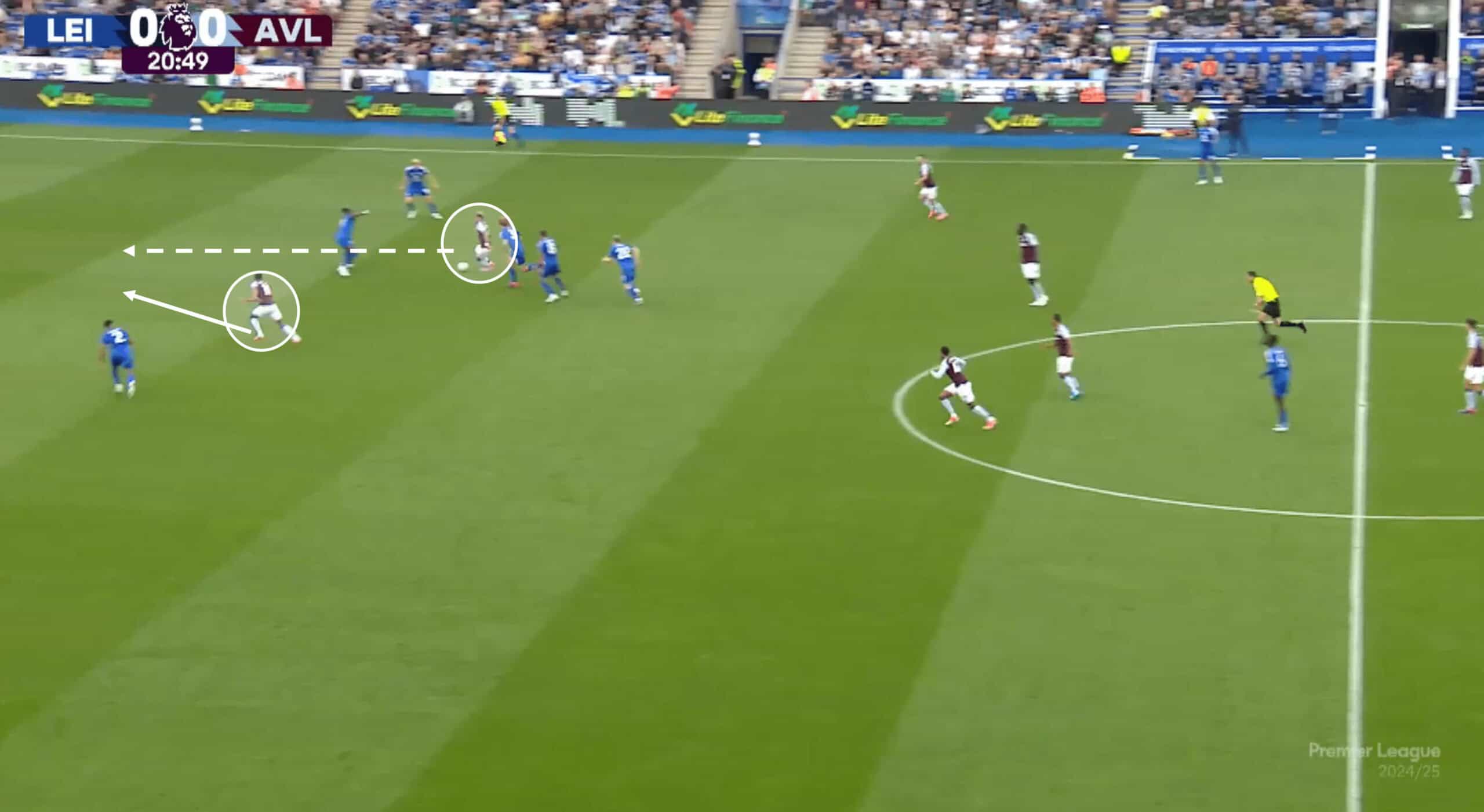

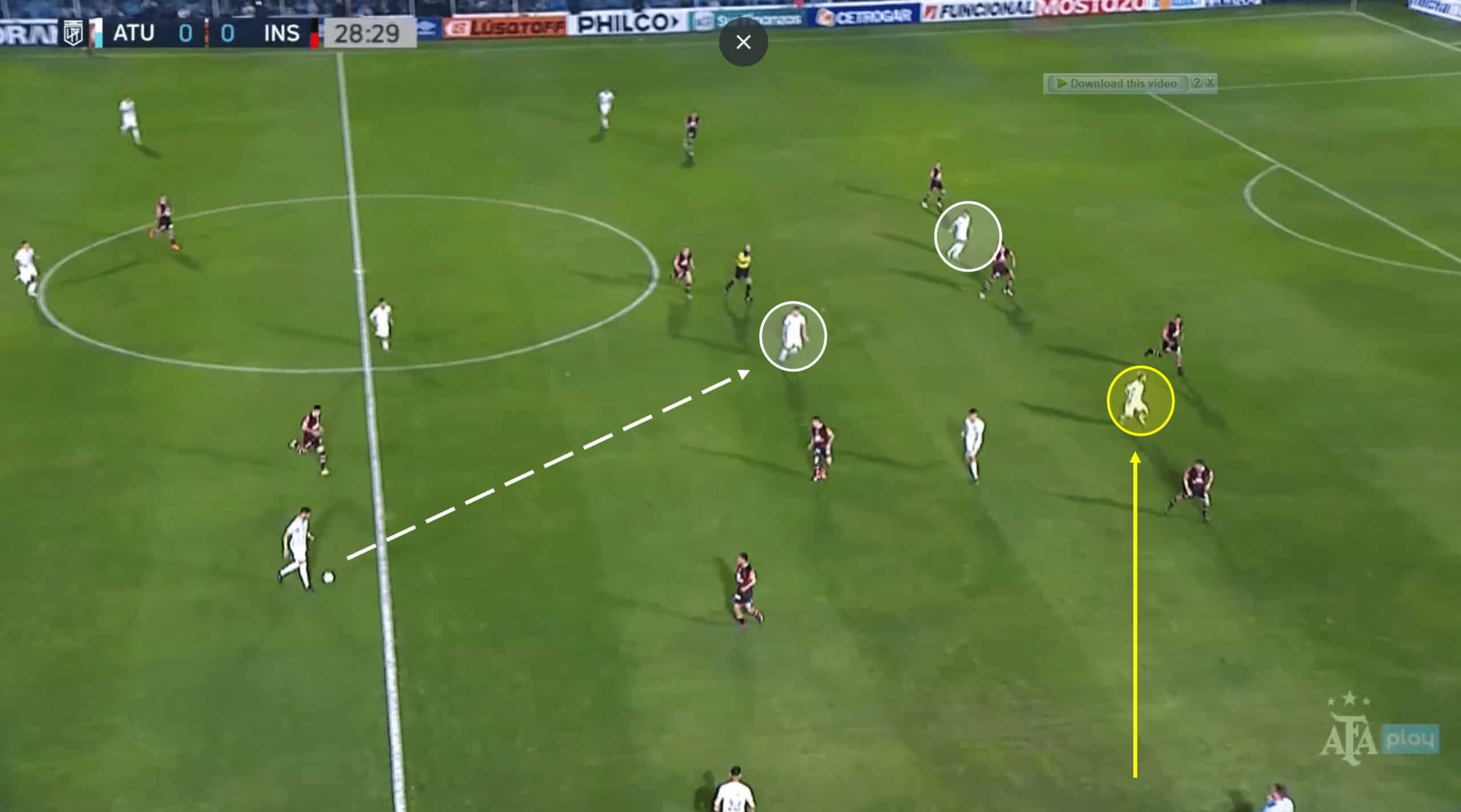

Figure 2 shows us how having two strikers can be effective and dangerous in attacking transitions, just as we mentioned earlier.

Aston Villa have used a 4-4-2 formation 60% of the time in the past year under Unai Emery, and have experienced their fair share of upsides thanks to that shape, including in transitions, as seen in figure 2.

Regaining the ball in high midfield areas when deploying two strikers often means the centre-forward is not isolated and doesn’t have to wait for nearby support, as that support is usually already there in the form of the strike partner.

Villa exemplifies this in Figure 2, with Ollie Watkins and Morgan Rogers being on the same wavelength in how they both immediately look for that combo of the run-in behind and the through pass to catch the opposition off guard.

But that dangerous through ball isn’t always on the cards.

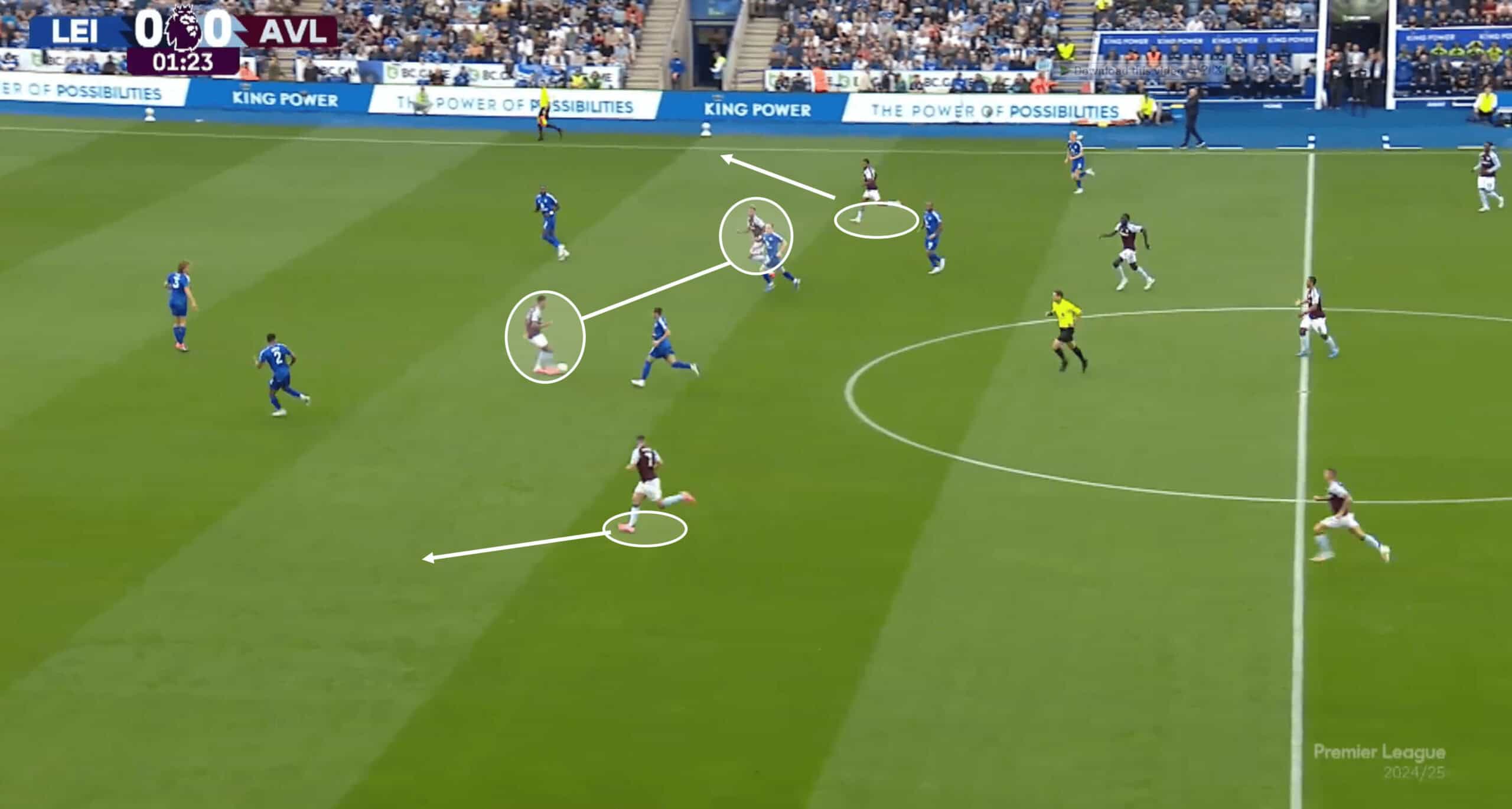

Villa, however, show us how attacking transitions can still be dangerous with two strikers, even if a bit of extended build-up play is required.

With the opposition defence positioned deep enough to eliminate the immediate through pass threat, Villa has to utilise the midfield unit to further stretch the momentarily disorganised opposition.

One effective method of achieving this is to have the wide players, or attacking central midfielder(s), drift out toward the flanks, just as Emery’s side do in the analysis image above.

From here, a quick pass out to one of the flanks is an option—the opposition will likely react to try to nullify that option, which will present Villa with other attacking avenues, such as keeping the ball between the two forwards or bringing the central midfielders into play.

Interaction With Midfield

When playing with just one centre-forward, there is a limitation in terms of how to deploy that player—do you have them running in behind, coming deep, or sitting on the shoulder of the last defender?

While these can obviously be effective, having two forwards allows your team to activate two of those tactics, which we’ve seen classically over the years—namely, the tactic of one dropping short while the other runs in behind.

In this segment of analysis, we’ll look at some examples of how teams with two strikers can assist the midfield in build-up play phases.

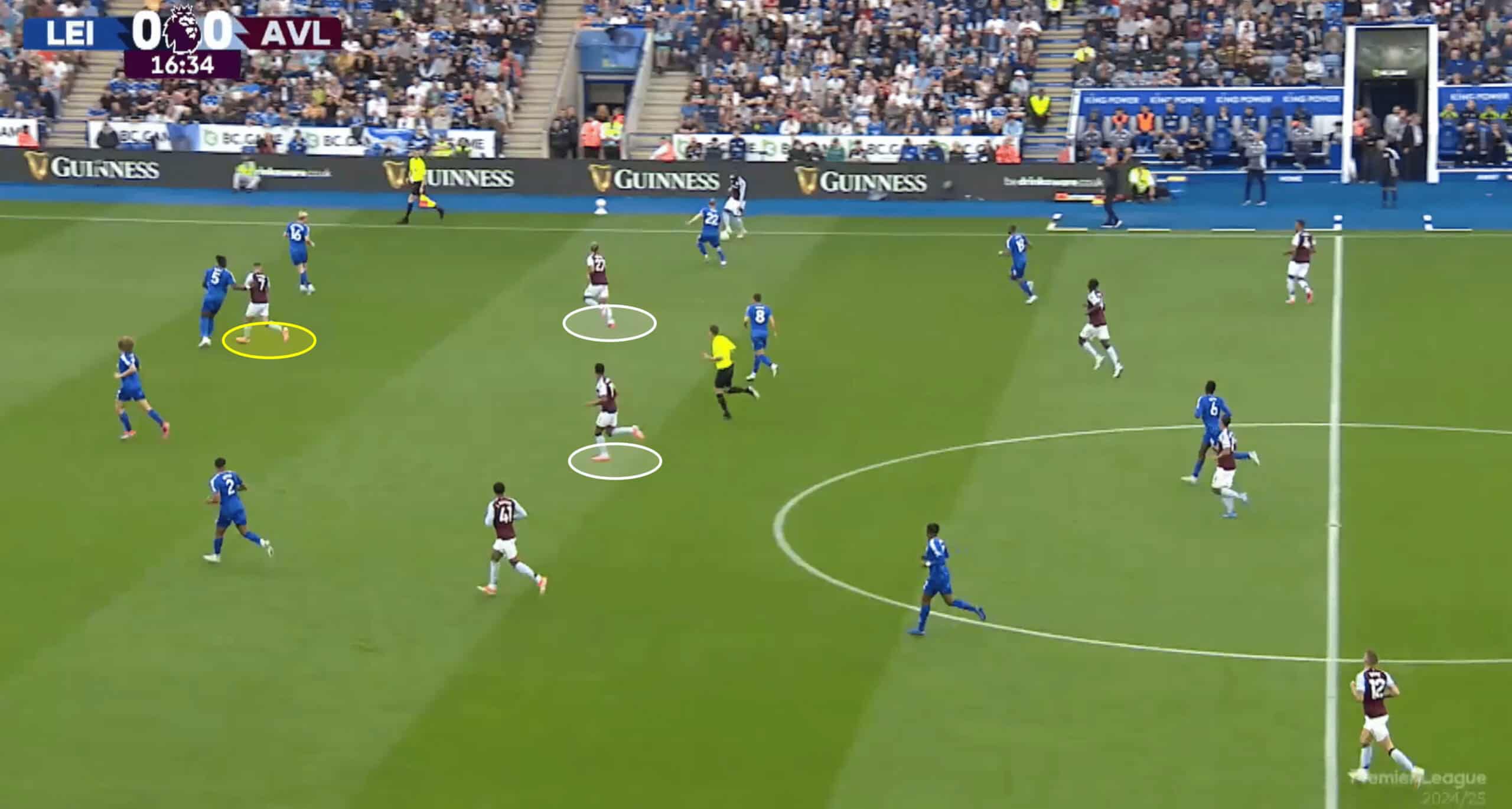

Sticking with Aston Villa as the example, we’ve seen something rather interesting from them this season, especially in the game against Leicester City, where the front two almost position themselves as number 10s with a midfielder playing beyond them.

Figure 4 shows exactly that, with John McGinn playing on the shoulder of the last Leicester defender, with Watkins and Rodgers behind him.

An interesting and somewhat rare approach, but Emery does like to sneak these little treats into his tactics.

The aim here is not to have the front two play important creative roles (although they can if called upon) but rather to try to bring McGinn into the play first.

If and when that ball does come into McGinn, he has the technical ability and positional knowhow to either make a first-time pass back to one of the front two, who will have made a suitable move to make that pass possible, or for one of them to make a sudden run through the opposition and in behind the defence, prompting either an audacious through ball from McGinn or a passing combination involving the other forward who remained deep.

Over in Argentina, Atlético Tucumán are (at the time of writing) in a fight for the top spot in the second phase of the Primera División, having opted for a 4-4-2 60% of the time in the past year.

Although Mateo Bajamich and Pulga Rodriguez’s regular partnership isn’t blessed with pace, they play an important role in their team’s build-up play tactics.

Tucumán like to execute a wider overload occasionally, which is what is taking shape in Figure 5.

Part of it at least aims to drag the opposition into that wide area, opening up space centrally or in other zones.

While one of the centre-forwards can sometimes directly get involved with that wide overload, they also serve an important role in being available after their teammates have executed said overload.

The ball eventually gets worked toward them in that central space, with fewer opposition numbers to worry about.

Alternatively, if possession progresses down the flank into a cross position, the front two will look to time their runs into the box well to meet a cross—again, with a lower opposition presence.

Tucumán are also keen on using a forward in deeper build-up play moments, as seen in Figure 6.

That centre-forward will drop in deeper, as is a common act of physical forward, looking to play the role of the bridge between midfield and the attacking unit in the final third.

An interesting addition to these tactics is that the right midfielder (highlighted yellow) will often drift inside to act as a makeshift centre-forward to keep that front two intact despite one of the original pair playing deeper.

This move, in turn, encourages the right-back to adopt more of a right-wing-back role and step into midfield, as seen above.

These tactics also encourage passing combinations in the final third once that ball is fed into advanced midfield areas, with four central players in close proximity to each other in the analysis image above.

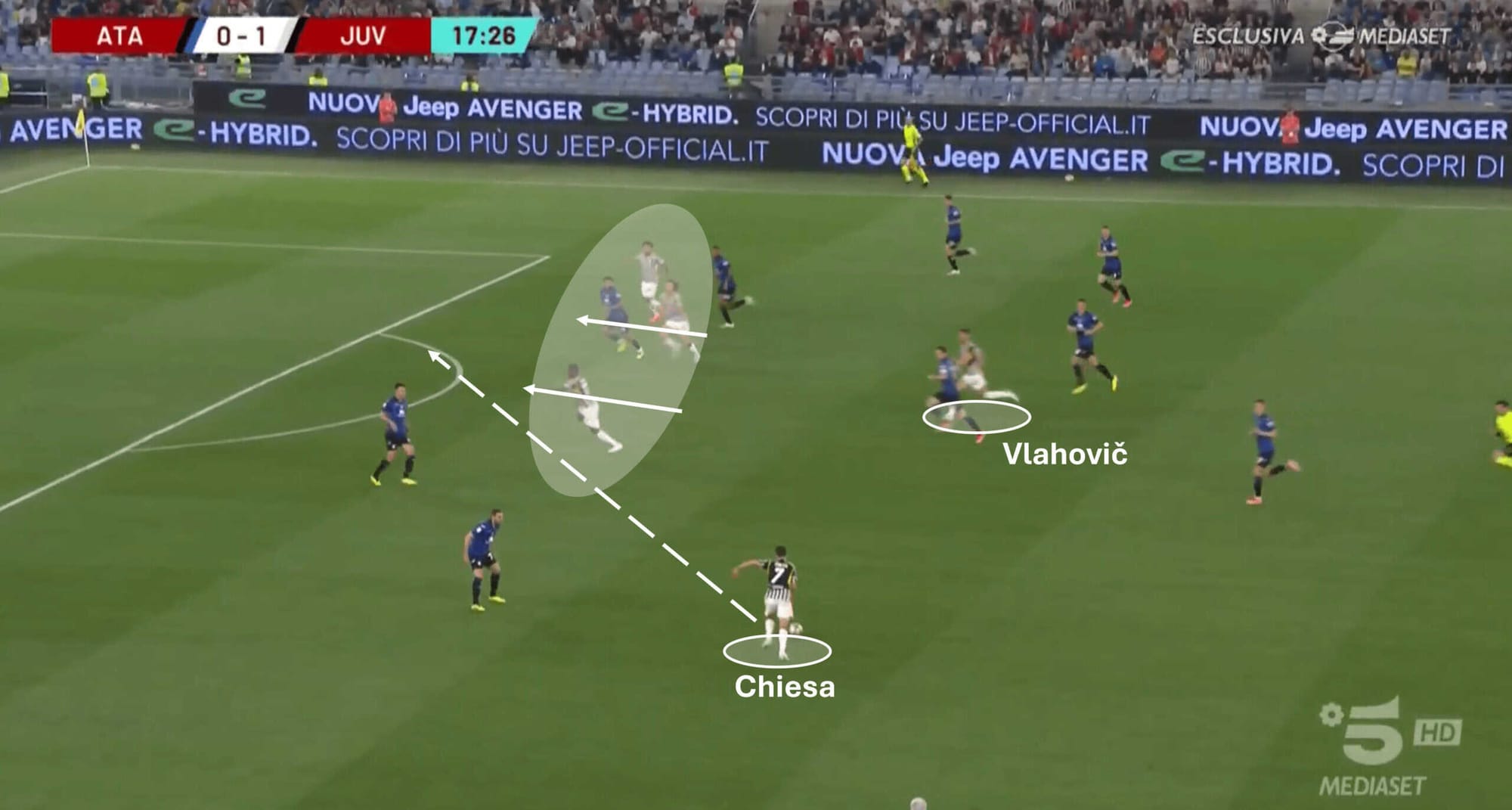

As we touched upon in the introduction of this tactical analysis, Serie A giants Juventus were fans of playing 3-5-2 in the 2023/24 season, using that formation 51% of the time.

For much of that time in a 3-5-2, Dušan Vlahovič was partnered with Federico Chiesa, with the latter, of course, now playing for Liverpool in the Premier League.

Even on paper, that is an interesting pairing — Vlahovič is more of a physical forward who likes to hold the ball up and bring teammates into play; Chiesa, who is a winger by trade, providing creative services for his side.

Yet, they provided 31 G/A between them last season, so they obviously know how to be dangerous in the final third as well.

Figure 7 actually demonstrates what we just described—Vlahovič dropping in deep to link up with the midfield unit before playing the pass out wide, and in that wide position was Chiesa — something he often liked to do in a Juve shirt while playing up front was drift into wide positions: when done at the right time, he can be an unmarked wide option.

The two centre-forwards’ creative roles in the build-up encouraged some of the midfield units to make forward runs for Chiesa to try and hit with his impressive passing range.

Working As A Duo

Understanding your strike partner’s style, traits, and tendencies is key to a successful pairing.

From linking up together in midfield areas to combining in the final third, playing with two strikers can provide a real boost in energy and intensity to several phases of play.

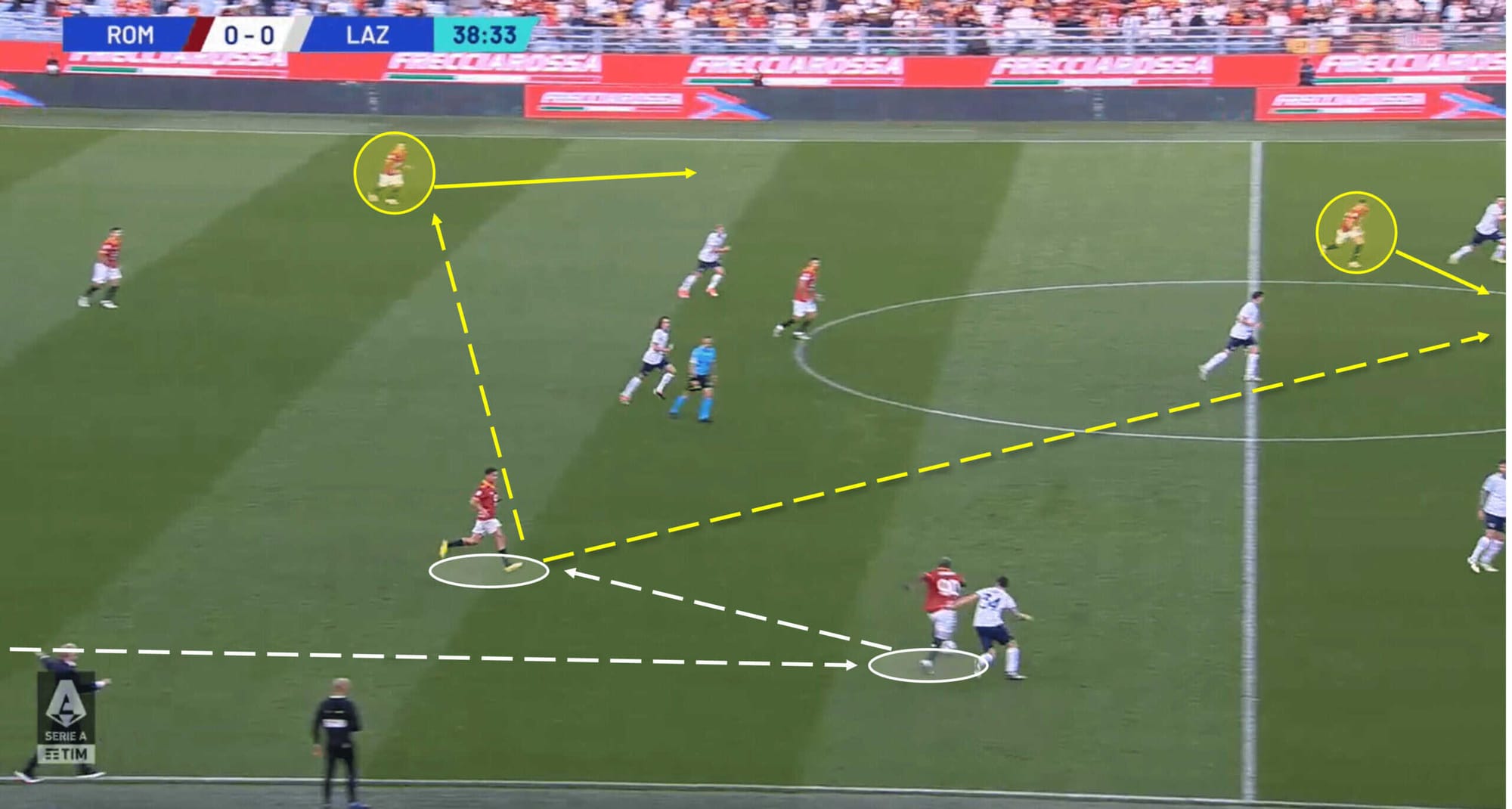

Figure 8 shows us how Roma utilised the duo of Paulo Dybala and Romelu Lukaku last season.

It’s more of a classic format — a physical striker leads the line alongside a creative player who can provide a spark of technical brilliance from the midfield zone.

As the analysis image above demonstrates, Dybala sometimes liked to drop in deeper, like a makeshift midfield playmaker.

Not only did this give his Roma teammates the option of playing a forward pass into midfield, but it could also create space between the opposition midfield and defence for Lukaku to operate in if a ball came his way.

Of course, that central route also allowed for the possibility of a direct link between Dybala and Lukaku.

Dybala’s positioning, in particular, also allows for more width in Roma’s attacking shape—his deeper presence means the midfielders around him can become wider, which in turn encourages the wing-backs to push on in high and wide positions.

As Figure 9 above shows, a direct link-up between two forwards can also happen in deeper areas during build-up phases and especially attacking transitions.

This example shows Lukaku, who took up a wider position in a transition moment, protecting the ball after receiving a pass from deep.

Knowing his attack partner Dybala is close by, the Belgian forward tries to get in position to lay the ball off to the creative maestro and does precisely that.

This particular tactic can be instrumental in possession progression.

Once receiving that initial pass, Dybala has the option of spreading the play out to the opposite wing-back or attempting a lofted through ball into the path of a run being made in behind the defence.

We see other teams deploy similar tactics with two forwards — using their strengths to combine in transition moments in the middle third to try and bring teammates into play in dangerous spaces elsewhere on the pitch.

We mentioned the importance of strike partners understanding each other and being on the same wavelength as much as possible to inflict the highest amount of damage on the opponent.

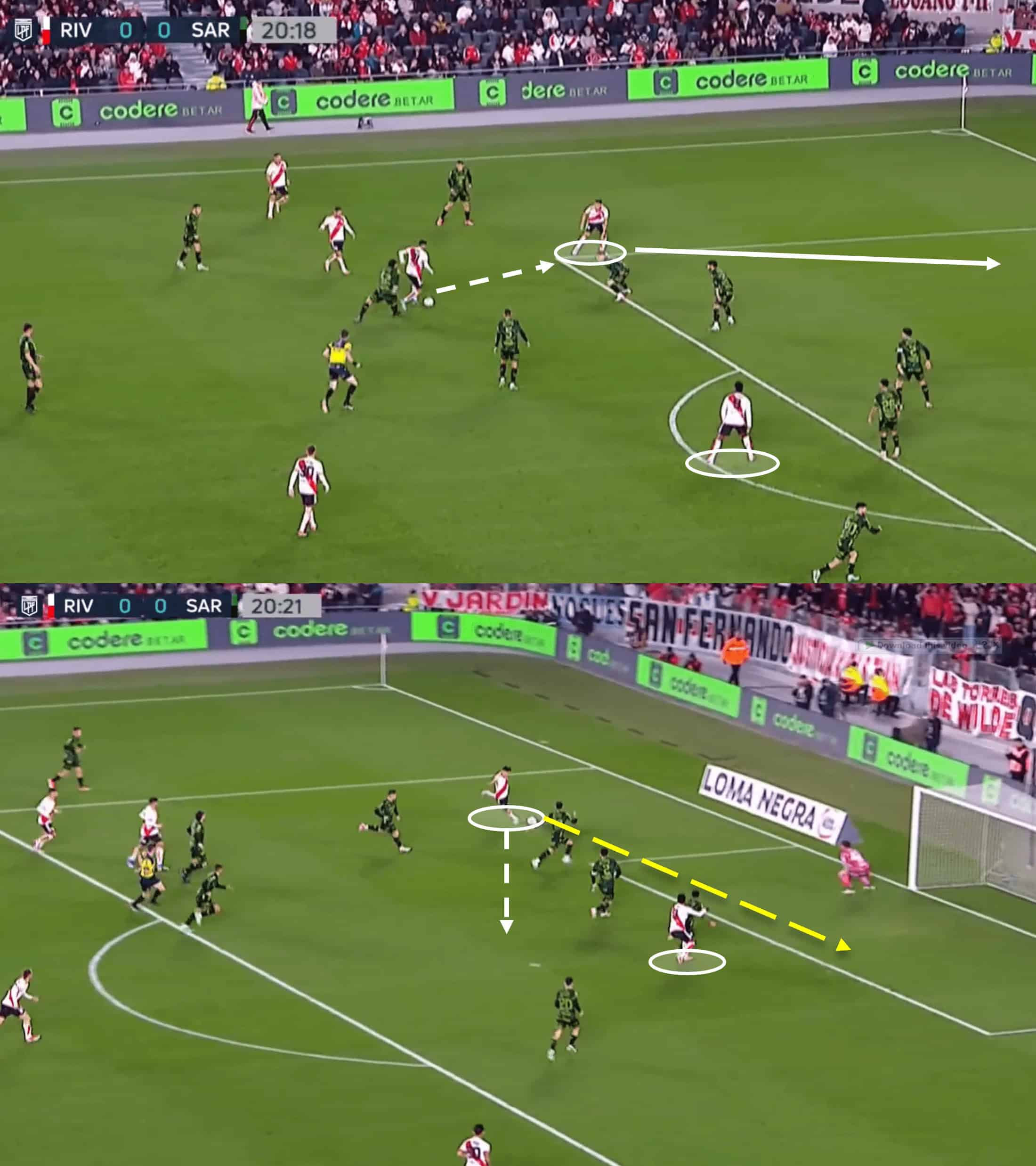

In Figure 10, we see an example of River Plate doing the opposite of that.

But let’s rewind a second because both forwards’ initial positioning and movement are important and effective.

With one centre-forward located centrally, about to move into the box, his partner makes a run in behind the opposition defence, but the pass does not come his way.

However, he maintains that wider position, with the eventually coming, giving the forward a chance to drive forward toward the byline before delivering a cross.

This is the point where a breakdown in understanding occurs between the two forwards — the centre-forward on the ball plays a cut-back pass into the path of nobody as if he thought his partner would look to wrong-foot his marker and drift toward the penalty spot.

Instead, he made a peeling run toward the far side of the six-yard box, anticipating a floated cross to get his head on the end of — a total lack of understanding in that moment from the River Plate duo; an example of just how important it is to have that cohesion.

Here, in Figure 11, we have an example of a strong tactical/positional understanding between two forwards.

In this example, Juve’s front two are both located centrally as their side looks to move possession down the right flank.

As they approach the box, with a cross imminent, a positional move is noticeable between Vlahovič and Chiesa—a crossover of sorts as the former looks to make a run into the box that would allow him to meet a cross while the latter makes a run closer to the man on the ball to offer a short option and drag a defender with him.

This is just one example of the importance of a strong foundation and understanding between the front two in terms of their roles, strengths, and traits — Juventus know that if a cross came in, Vlahovič could be dominant in the air.

At the same time, if a short inside pass was played, Chiesa has the technical ability to make something happen from that position.

Conclusion

While we may not have the same amount of elite strike partnerships in the modern game as we once did, hopefully, this tactical analysis has provided some knowledge and insight into how a two-striker system can operate in today’s game.

Whether it’s the way the unit operates in a press or their link-up play in midfield, the duo can directly impact each other’s game—in a positive way—if things are done correctly.

And, of course, they can create chances for each other in a multitude of ways.

Take the final two images, for example — the River Plate one showed how it’s possible for a centre-forward to be a direct chance creator inside the box, while Chiesa showed us that a decoy move can raise the impact Vlahovič has inside the box.

Comments