The first leg of one of the more intriguing UEFA Champions League semi-finals in recent memory was played in Madrid between Pep Guardiola’s Bayern Munich and Carlo Ancelotti’s Real Madrid in April of 2014. Bayern essentially dominated the first leg of the tie, but ultimately fell to Madrid 1-0. The return leg in Munich, which many felt Bayern would again dominate, ended catastrophically, with Real Madrid putting four goals past the Bavarians.

This first tactical analysis in this two-part series looks to provide an analysis of the tactics used by both Bayern Munich and Real Madrid that ultimately led to the 1-0 finish in Madrid. While Ancelotti’s men earned the victory, the analysis of both his and Pep’s tactics resulted in two very different strategies, both looking to achieve the same result: victory.

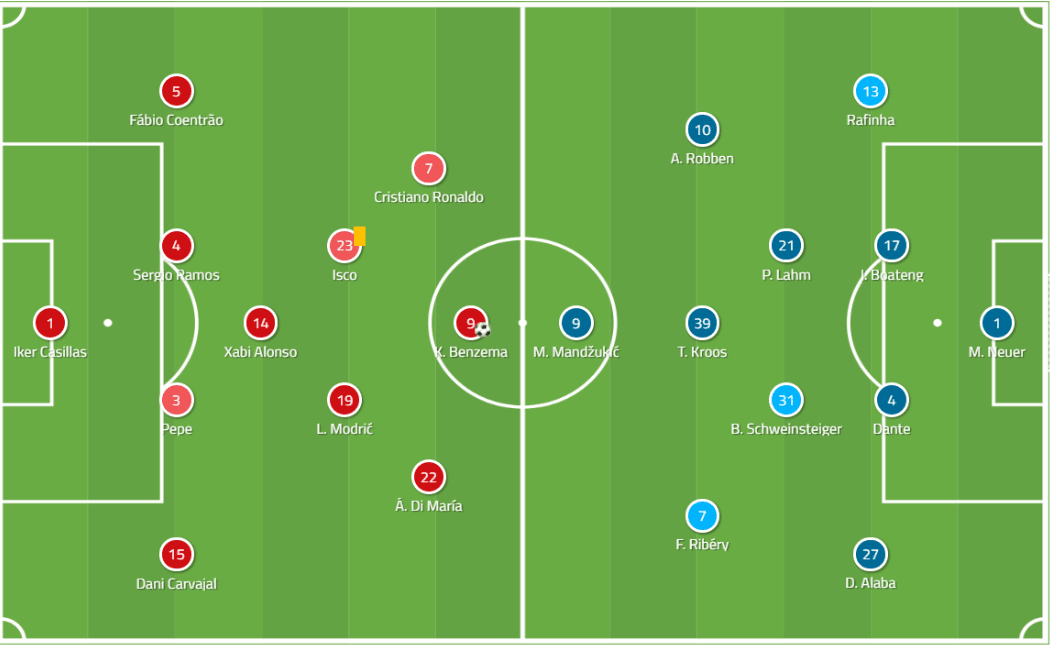

Lineups

Ancelotti sent out Real Madrid technically in a 4-3-3, although they spent most of their time defending in a 4-4-2 with Iker Casillas in goal. Fábio Coentrão, Pepe, Sergio Ramos, and Dani Carvajal started as the back four, with Pepe and Ramos as the centre-backs. In front of them, in their primary 4-4-2 shape, was Ángel Di María, Xabi Alonso, Luka Modric, and Isco. The two forwards on the night for Madrid were Karim Benzema and Cristiano Ronaldo.

Guardiola had Bayern come out in a very fluid 4-2-3-1 with Manuel Neuer in goal for the Bavarian club. David Alaba started at left-back, with Dante and Jérôme Boateng as centre-backs, and Rafinha as the right back. The midfield trio consisted of Toni Kroos, Bastian Schweinsteiger, and Phillip Lahm, although Lahm was later moved back to right-back. Franck Ribéry and Arjen Robben started on the left and right-wing, respectively, with Mario Mandžukić starting as the lone striker for Bayern.

Bayern’s build-up

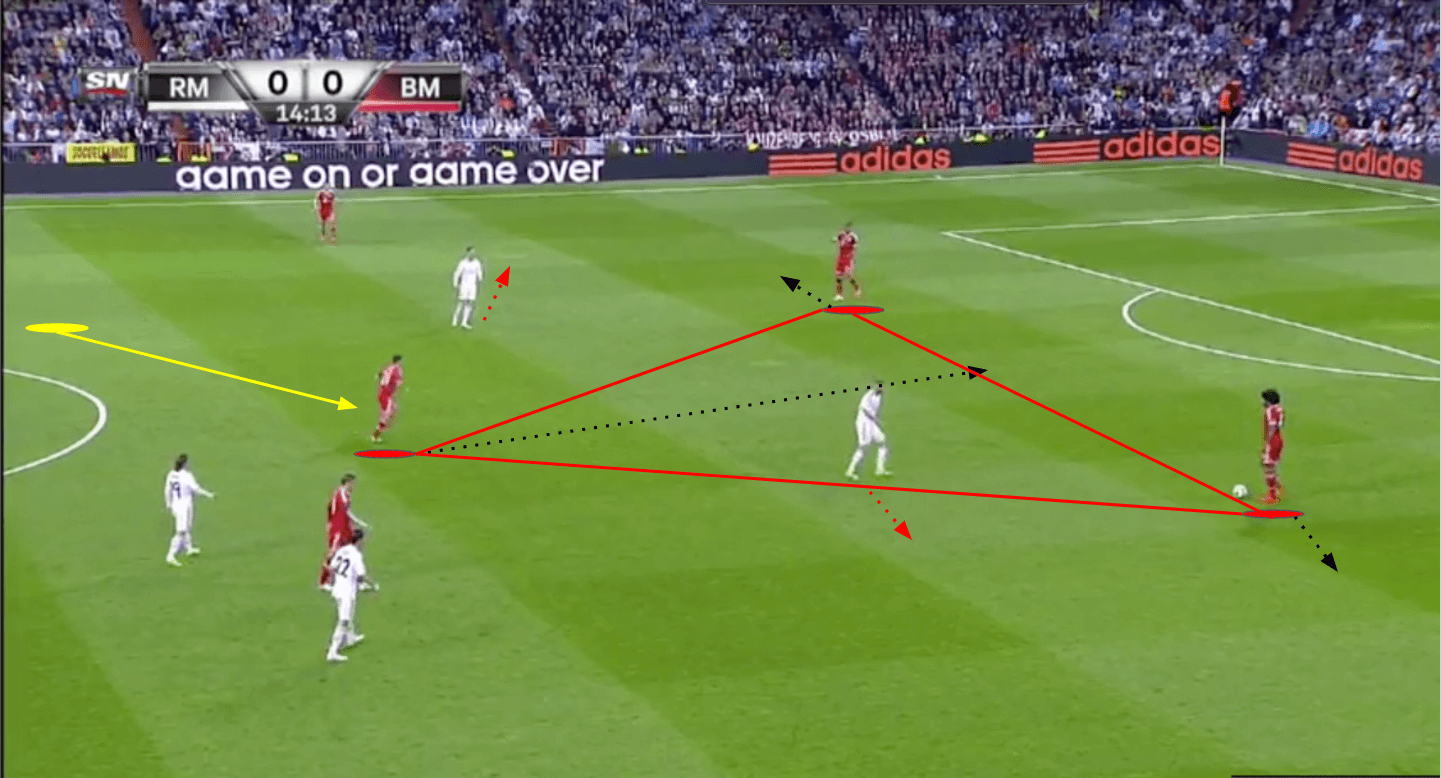

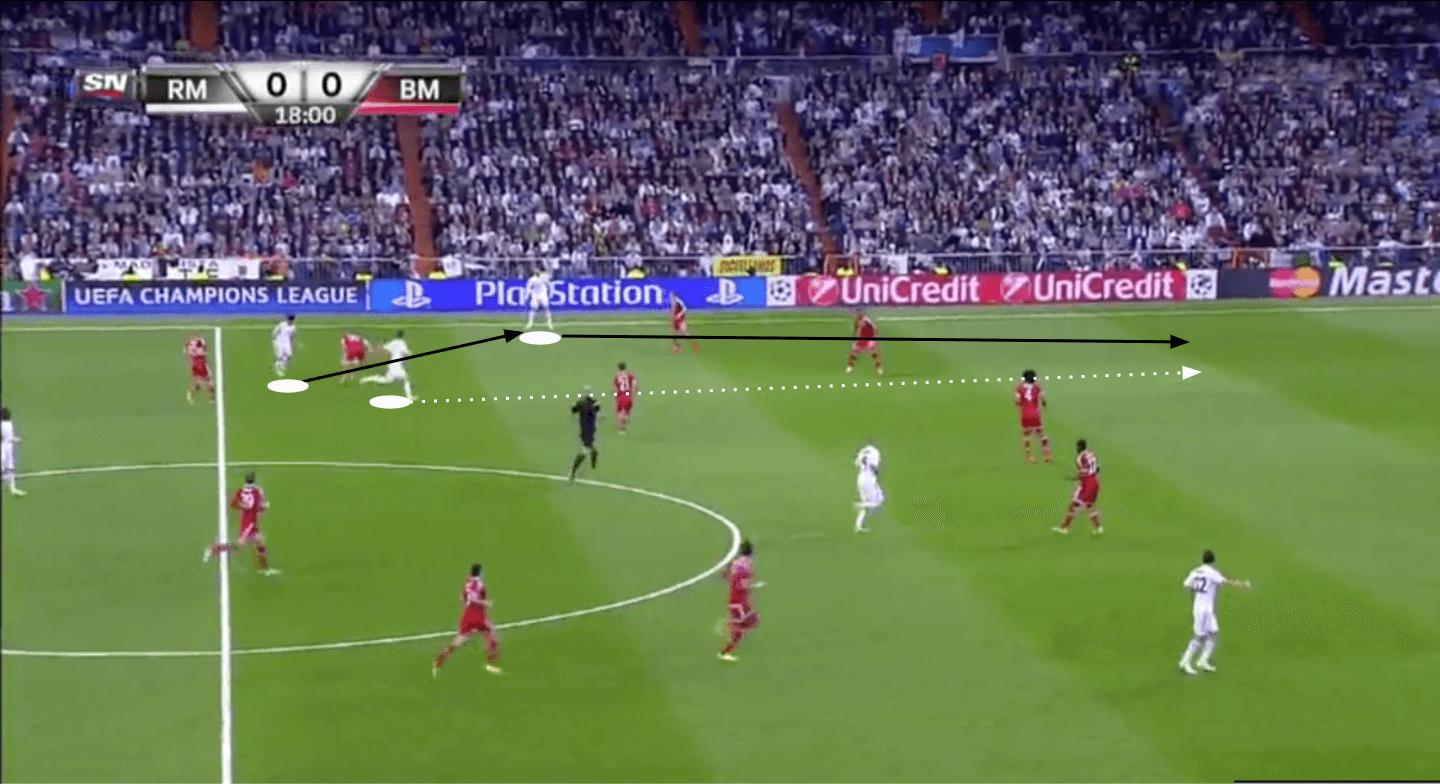

One of Guardiola’s core principles of play is that a clean progression of the ball during the build-up is key, as it has a chain reaction in regards to the opponents’ movements, both individually and collectively. The movement of the ball is secondary: the primary purpose is to get the opponent moving in order to disrupt their defensive structure. Initially, one of the ways Bayern looked to progress the ball was through their use of Phillip Lahm, who was pairing with Toni Kroos in as holding midfielders. When the ball was at the feet of either Dante or Boateng, they had Lahm between the first two lines of defence as a passing option. If the ball was at their feet and Madrid was pressing closely, Lahm would drop in between the two centre-backs and receive a pass.

Lahm’s movement had multiple effects on the defence. First, Dante and Boateng would be able to get even wider, dragging their corresponding defenders, Ronaldo and Benzema, with them. The second effect is that it created more space in the centre of the pitch for teammates to exploit. In this instance above, Toni Kroos, who was just off-screen, followed the movement of the yellow arrow, checking into that space from the left side of the centre of the pitch. If open, a simple pass could be played to him, and he could turn. If he was followed by a defender, Arjen Robben could check into the space that Kroos had just left, where he would be an option for Lahm or a vertical ball from Boateng.

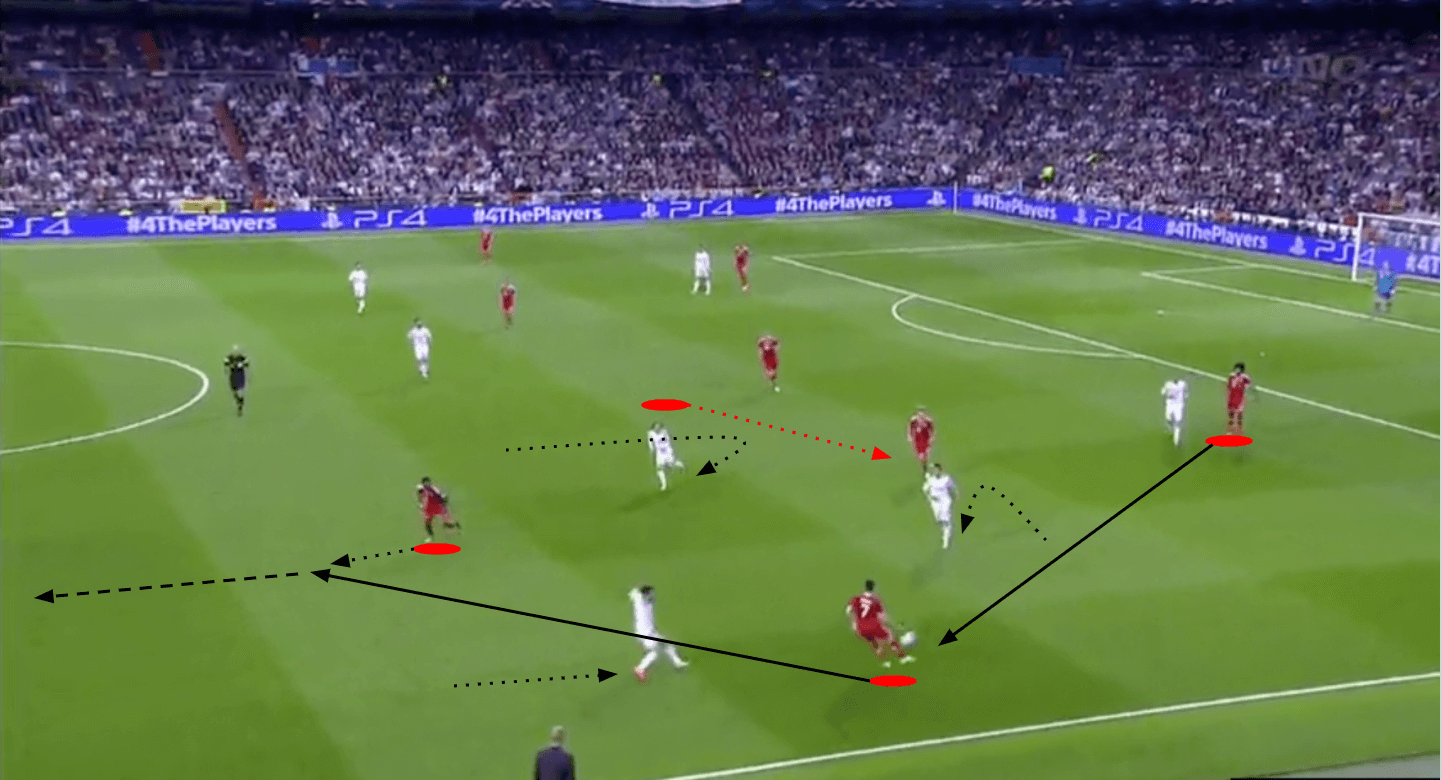

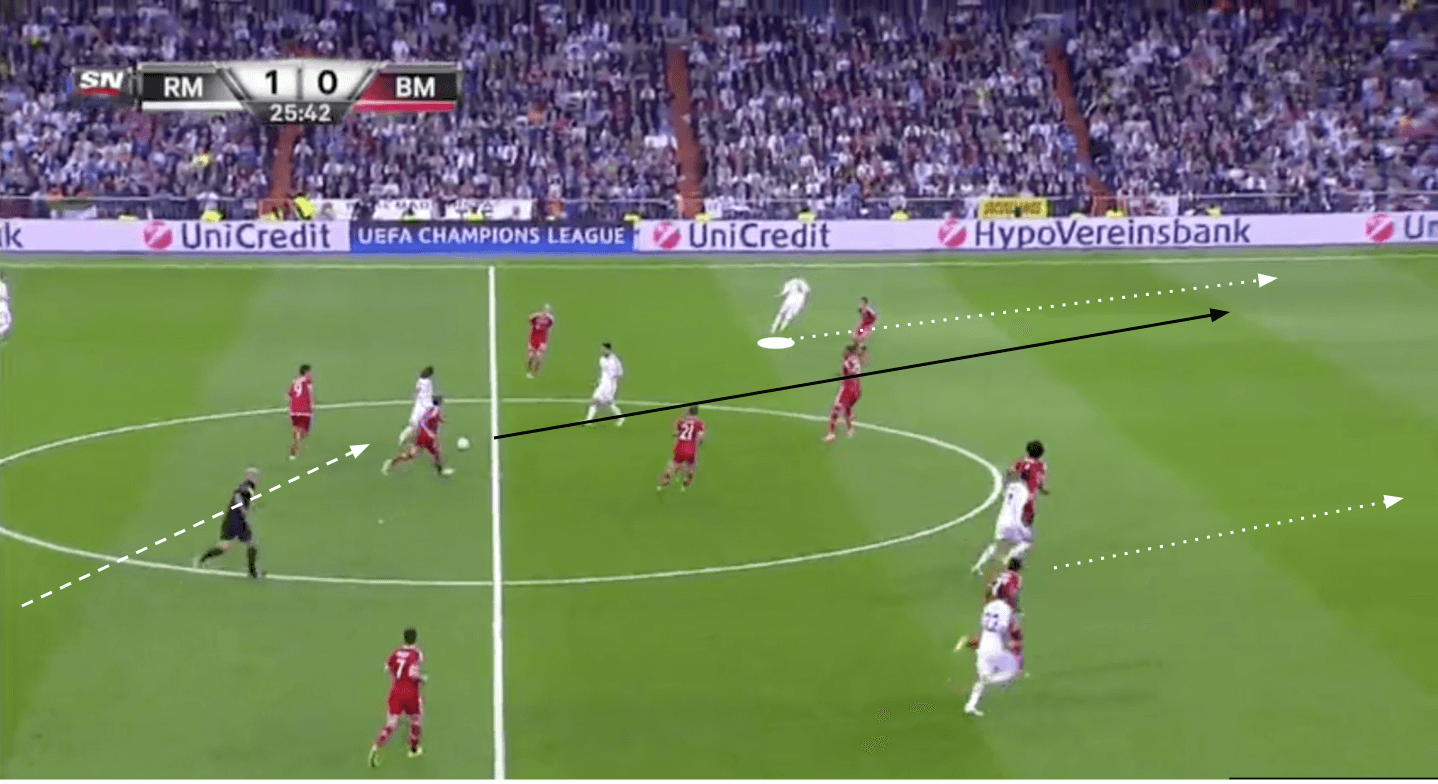

When Madrid would drop off from a higher press, Bayern used a diamond shape to progress through the first line of Madrid’s defence. The outside-backs would stay high and wide, and the two holding midfielders, in this case, Schweinsteiger and Lahm, would connect with the centre-backs.

As the ball was played towards Rafinha on the right, Schweinsteiger would drift into the half-space to support him. This drew the attention of Ronaldo, who closed him down in order to eliminate him as a passing option. Isco, now on the right, dropped in front of Rafina, who had the ball at his feet. This opened up a large passing lane for Lahm to step into. Rafinha could now play Lahm into the half-space, where he was the most likely to be able to deliver a more effective pass. In this instance, Lahm played a diagonal ball forward, forcing Madrid’s second defensive line forward, opening up a large gap between the lines that Bayern would look to exploit. Bayern’s build-up had done exactly what it set out to do: move opponents to cause chaos within their own defensive shape.

Alaba, Kroos, and Ribéry’s rotations create chances

The success of Bayern’s build-up, combined with their rotations on the wings, allowed them to attack Real Madrid’s goal for most of the night. These rotations were particularly effective on the left side of the pitch, involving David Alaba, Franck Ribéry, and Toni Kroos. These three naturally formed a triangle on a consistent basis, but it was their movement as that shape that caused problems. In the first image, Kroos had dropped to help develop the build-up play for Bayern.

As he picked his head up, Ribéry was checking into the perfect space — he’s between two opposing defenders, and he is dragging Dani Carvajal with him. Alaba, the left-back, started the entire movement with his run forward. This forced Carvajal to turn and retreat, opening up the space for Ribéry to receive the pass. Ribéry was able to turn as he received the ball, and he played another vertical pass into Alaba’s path, who was able to take a touch and then cross it before being closed down. While Alaba’s options in the box were limited, their ability to break down the right side of Madrid’s defensive structure was not.

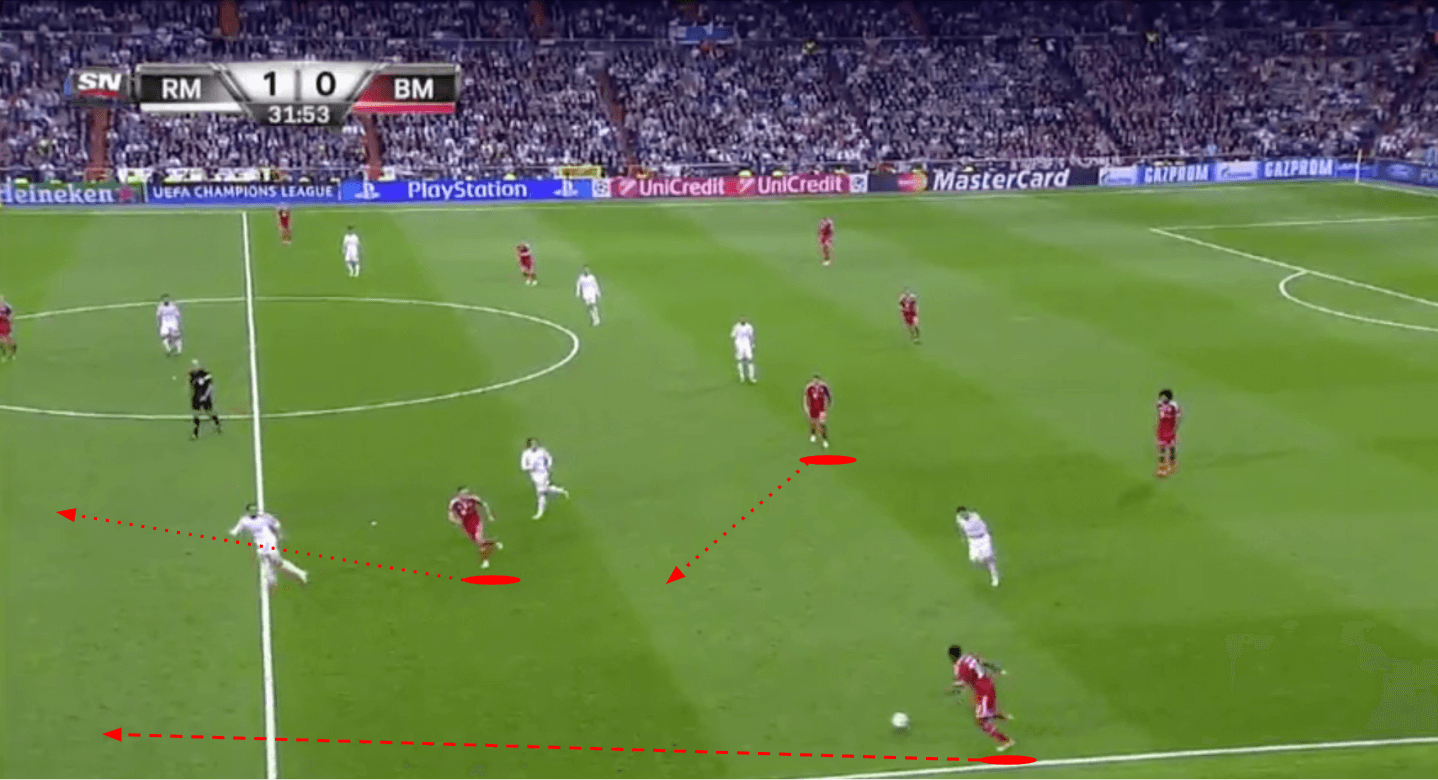

Six minutes later, Kroos’ rotation with Alaba attracted the attention of two Madrid defenders, who stepped up to prevent Kroos from receiving the ball from Dante.

Alaba moved inward to replace Kroos’ positioning, which allowed Ribéry to drop down into the open passing lane, where he received the ball from Dante. Alaba’s original move inside at first seemed ineffective, but Ribéry receiving the ball attracted the attention of Carvajal, who stepped to pressure. This allowed Alaba to receive a first-touch pass from Ribéry, and he was off and running up the pitch at Pepe, Madrid’s centre-back. Ultimately Alaba laid the ball off for Ribéry, who was forced to cross due to the over-hit pass.

Later in the match, Ribery dropped down into the half-space to help with the build-up, effectively replacing Kroos in the situation.

This opened up space because Carvajal followed, allowing Alaba to dribble forward with the ball at his feet. Alaba progressed forward up the wing, completing his rotation with Ribéry. As Ribéry supported Alaba’s run forward, resulting with them passing their way through Madrid’s defence with a series of 1-2 passes, Kroos completed his rotation with Alaba by supporting behind the play, still ensuring that someone was in place to defend and prevent a counter-attack.

Bayern’s concentration on building up through the left-wing forced Madrid to adjust accordingly. After halftime, Guardiola had Robben and Ribéry switch wings for about ten minutes, looking to overwhelm Madrid even more on their right side, but the connection between the players was not the same, resulting in Pep reversing his decision. This dominance down the left side allowed them to pull Madrid over, allowing Bayern to take advantage of a qualitative advantage on the right-wing: Arjen Robben.

Bayern also attack through Robben

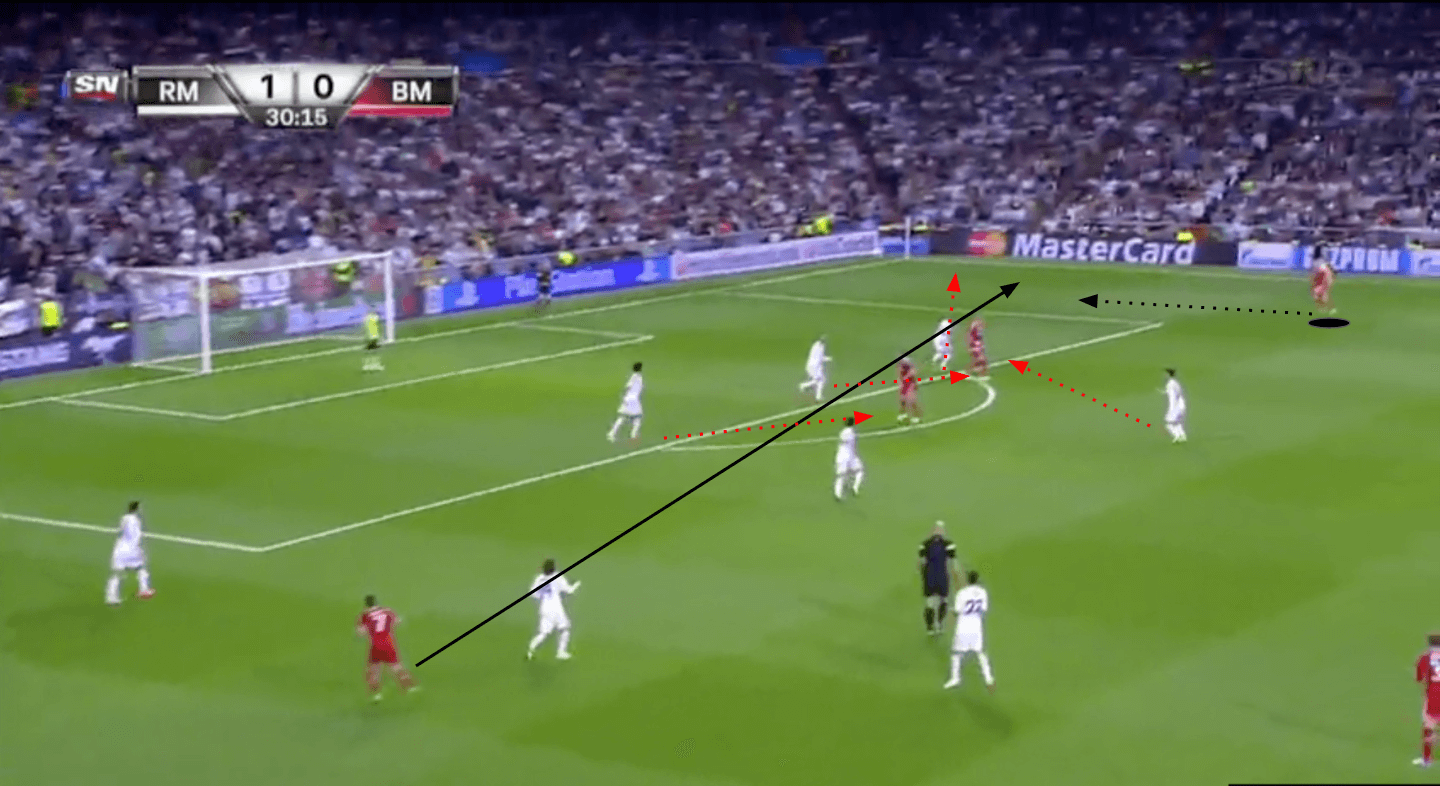

Bayern’s attack down the wings initially set up by Kroos, Alaba, and Ribéry, allowed them to target Robben and leave him isolated against Fábio Coentrão. Guardiola obviously saw Robben as someone who could overwhelm Coentrão, and so he looked to exploit this qualitative advantage. The first instance began from the left-wing, when Ribéry made a long switch from the left side of the pitch to the right.

Robben settled the long pass with his chest as Coentrão slid over to mark him. Pepe and Ramos both had Bayern players to mark, so they were unable to assist Coentrão in his defensive duties. Isco was able to drop a little bit, but all he did was prevent Robben from playing a pass out of the space. Robben quickly beat Coentrão and was able to cross the ball to the back post, where Mario Mandžukić was unable to finish the opportunity. This quick switch of the ball was certainly effective, prompting Bayern to attempt other ways to attack through Robben, which were not as effective.

One way in which they did this was by looking to pass through Madrid on the right side by inverting their right-back, Rafinha.

Rafinha would take up a position within the half-space. In the image above, he had the ball at his feet, looking to find Robben with either a pass that would split the Madrid defence or an aerial ball over the defence. This would allow Robben to receive the ball and dribble at his defender with speed, causing a big problem for Madrid. However, in this instance, Lahm is too close, allowing Madrid to send three defenders to prevent either of those options from happening. While the ball ended up at Robben’s feet, it got there too slowly and Madrid were able to shift over appropriately.

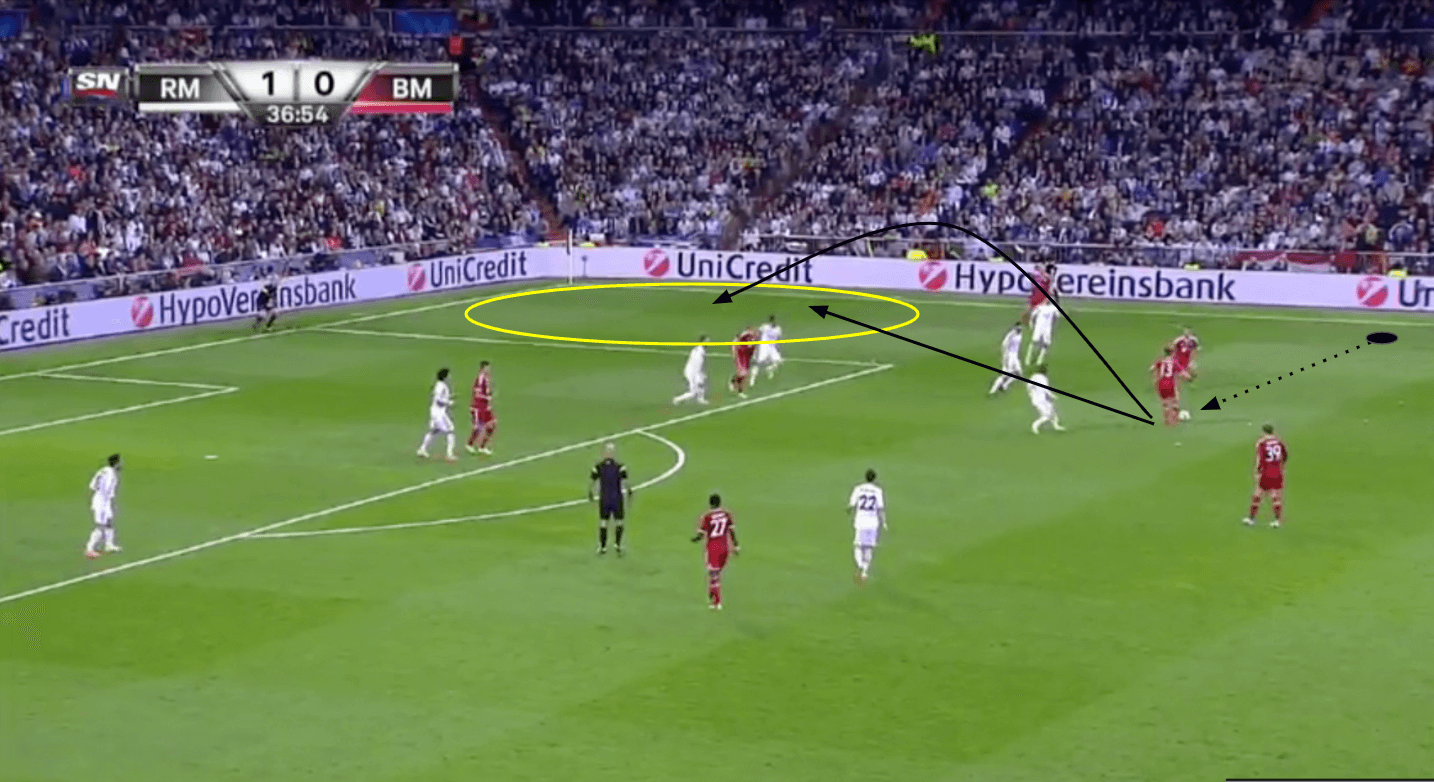

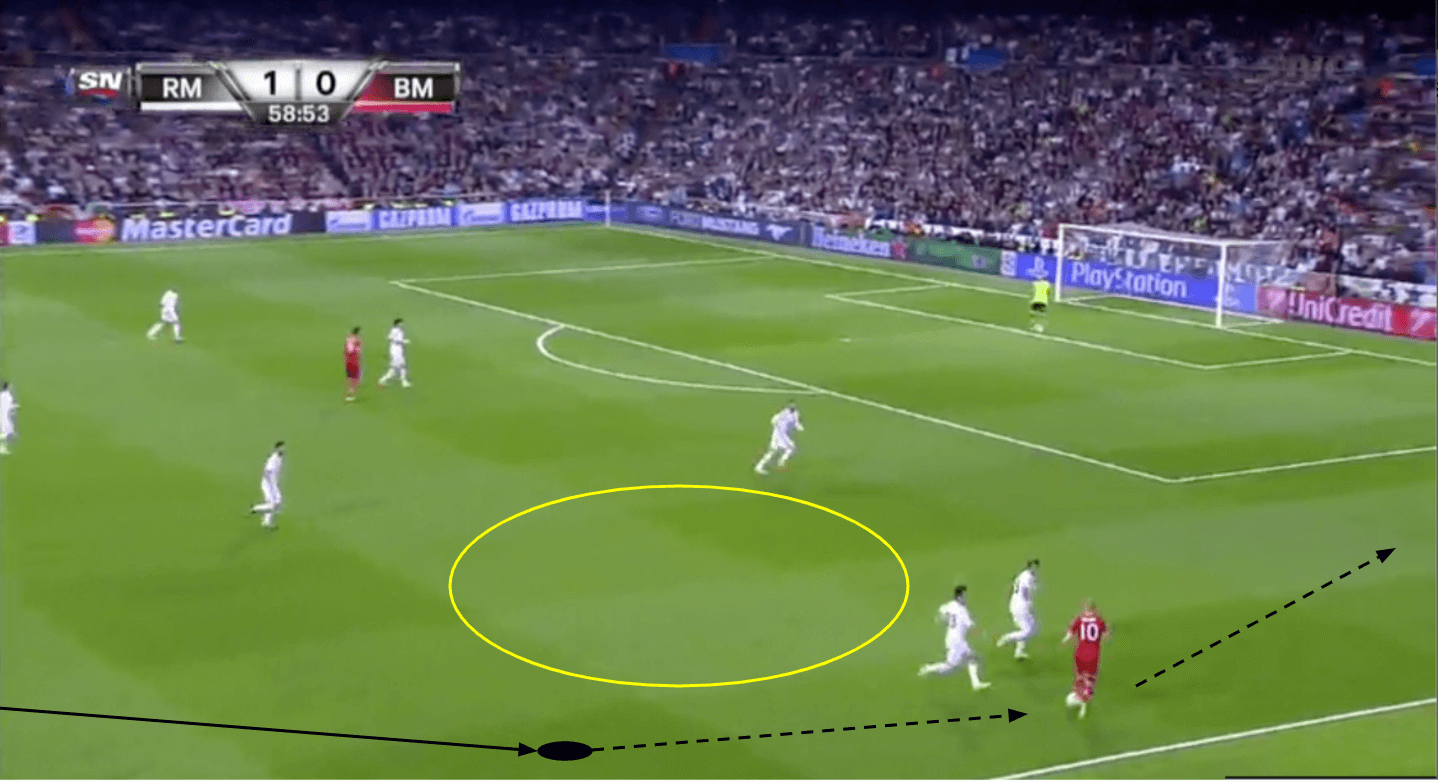

Later in the match, the attempts to get through on goal via Robben continued, although this time the over-reliance on him was apparent. Robben received a long pass from a teammate off of a restart and dribbled up the pitch.

However, he was not supported by any of his teammates anywhere nearby. Instead of playing a pass back to Rafinha or a supporting midfielder, Robben continued to dribble, attracting the attention of three Madrid defenders in the process. While effective in attracting attention, Robben’s attacks weren’t actual threats on goal unless Bayern had someone in that yellow area inside the half-space. This would cause Madrid to have to be more spread out defensively, giving Robben more room to operate. Instead, they could easily double or triple-team Robben when he was alone, neutralising him as a threat.

Madrid’s defensive lapses

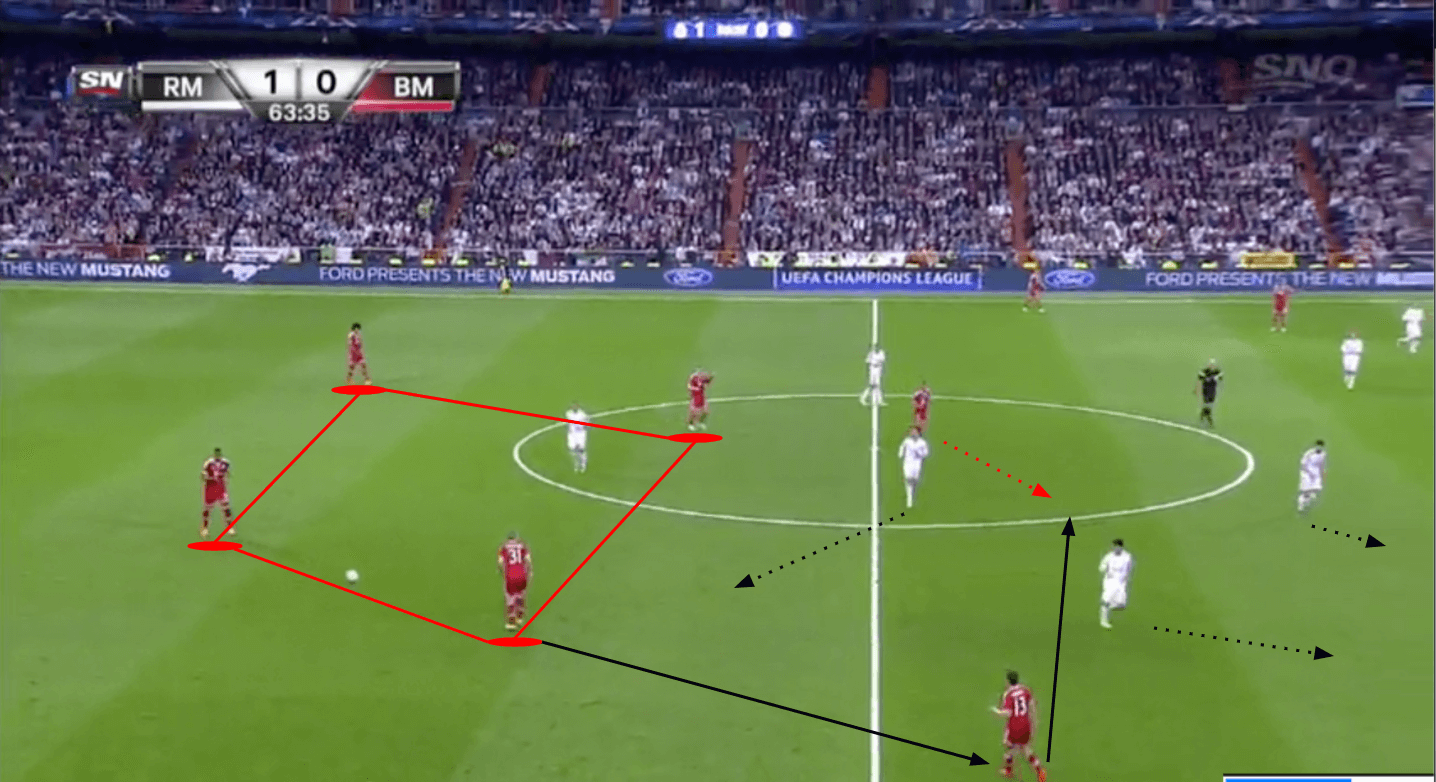

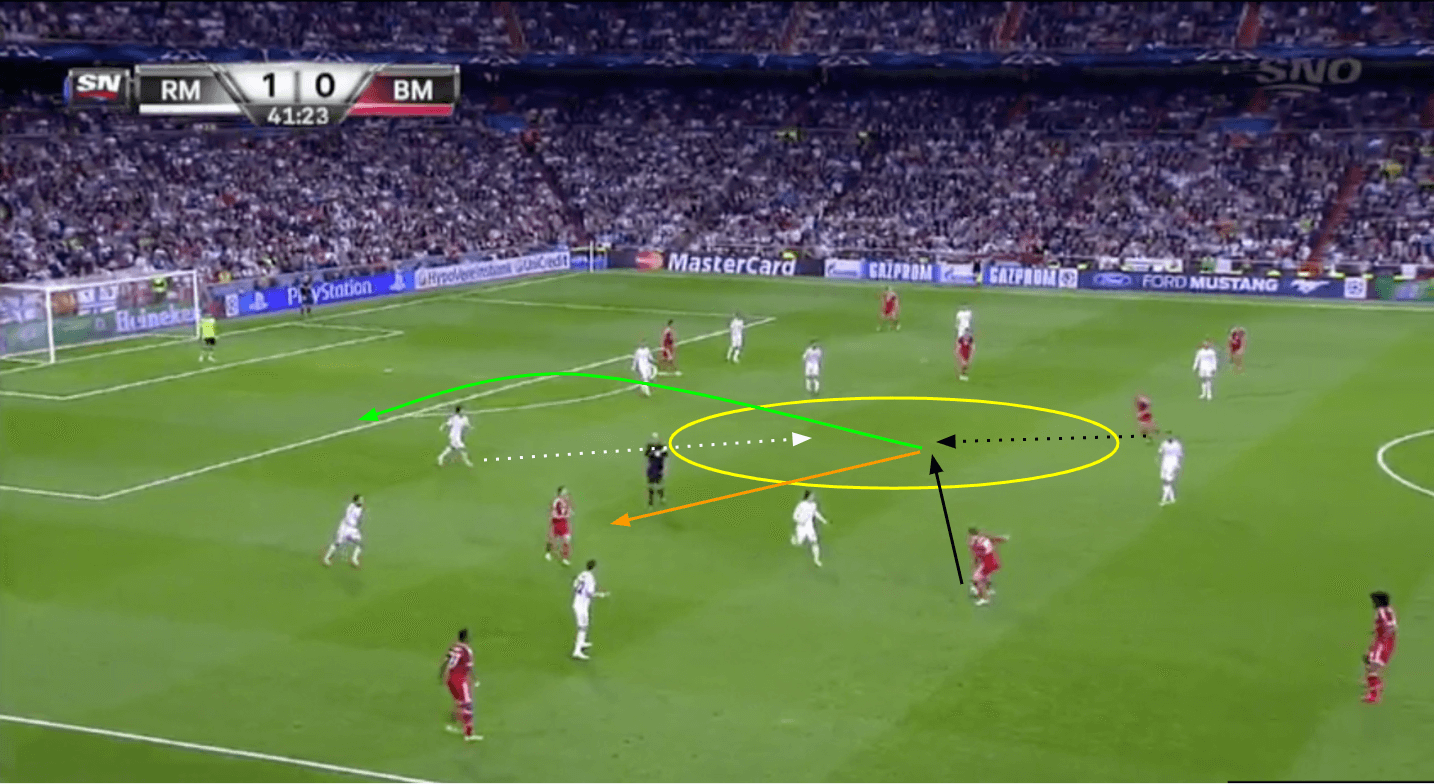

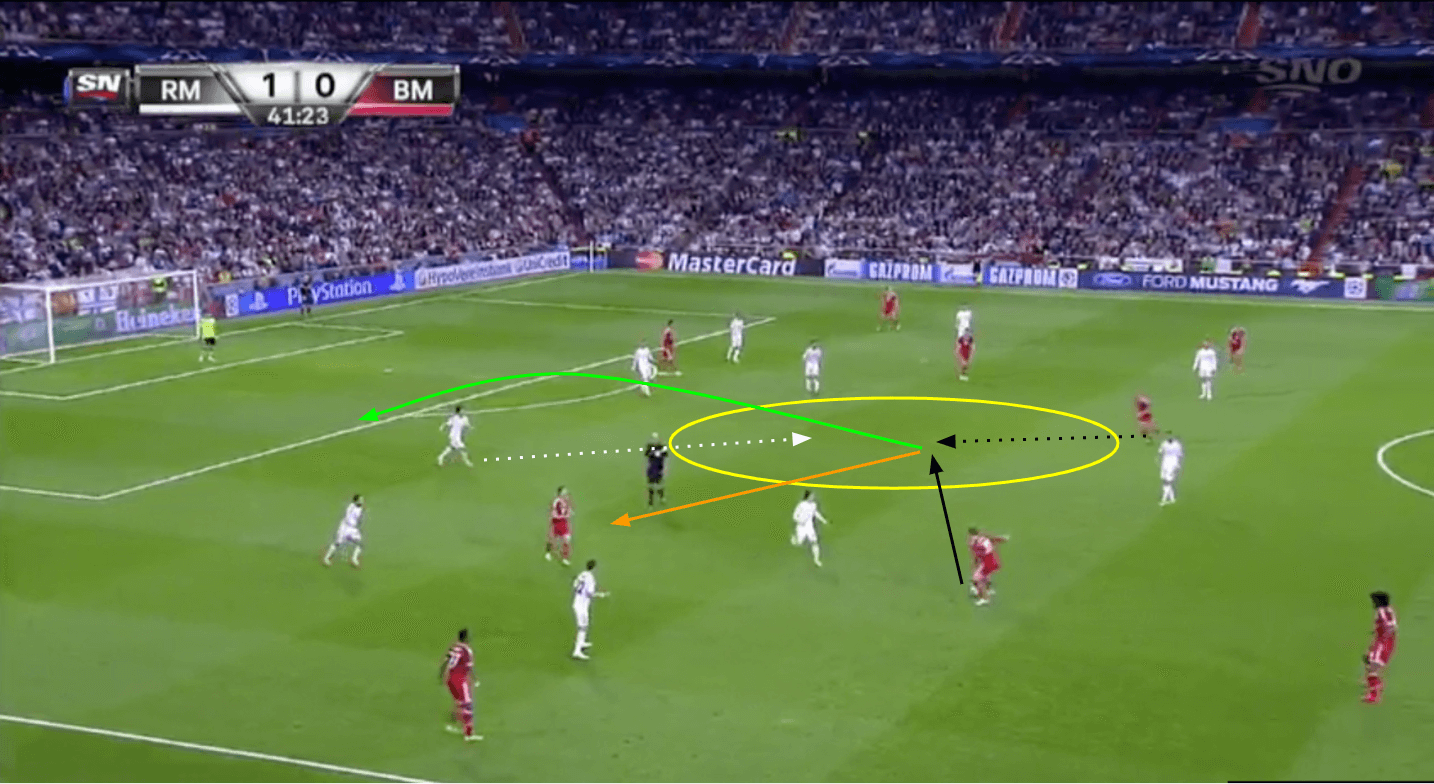

Madrid seemed to come into the match knowing that Bayern would dominate possession. Bayern saw 72% of the possession, generating 18 shots in the process. This defensive set up implies that they would be more organised defensively, but there were multiple times where they were incredibly lucky Bayern were unable to exploit them. The first instance came at the end of the first half when a large gap opened up in midfield as Xabi Alonso failed to slide over when Modric pressured Toni Kroos.

Kroos found Lahm in all that space as Alonso began to react. Recognising the danger, Pepe, the centre-back, stepped up to Lahm to pressure him, opening up acres of space behind him in which Ribéry could have run if Lahm had opted for the green pass. Instead, Lahm opted for the orange pass, effectively killing the play dead.

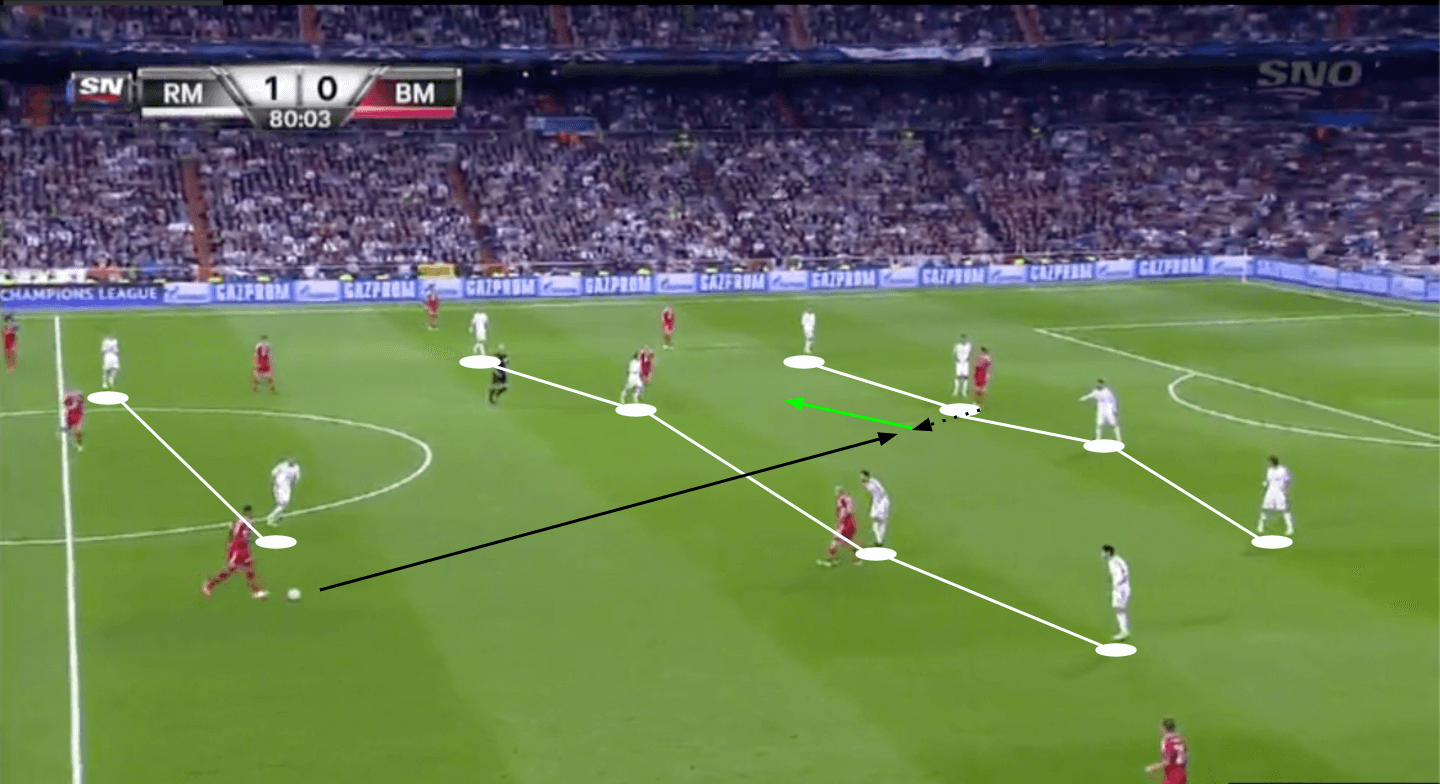

The trouble with protecting the centre of the pitch continued in the second half for Madrid, with their zonal defending having them stretch their defensive line. Again, the distance between the two central midfielders is far too large.

If Boateng had played a vertical pass to Mandžukić, a simple layoff (in green) would have resulted in a 2v1 with Bayern continuing to attack down the left side. Madrid, once again, were too slow in shifting over their defence, allowing for this large gap to open up in the middle of the pitch.

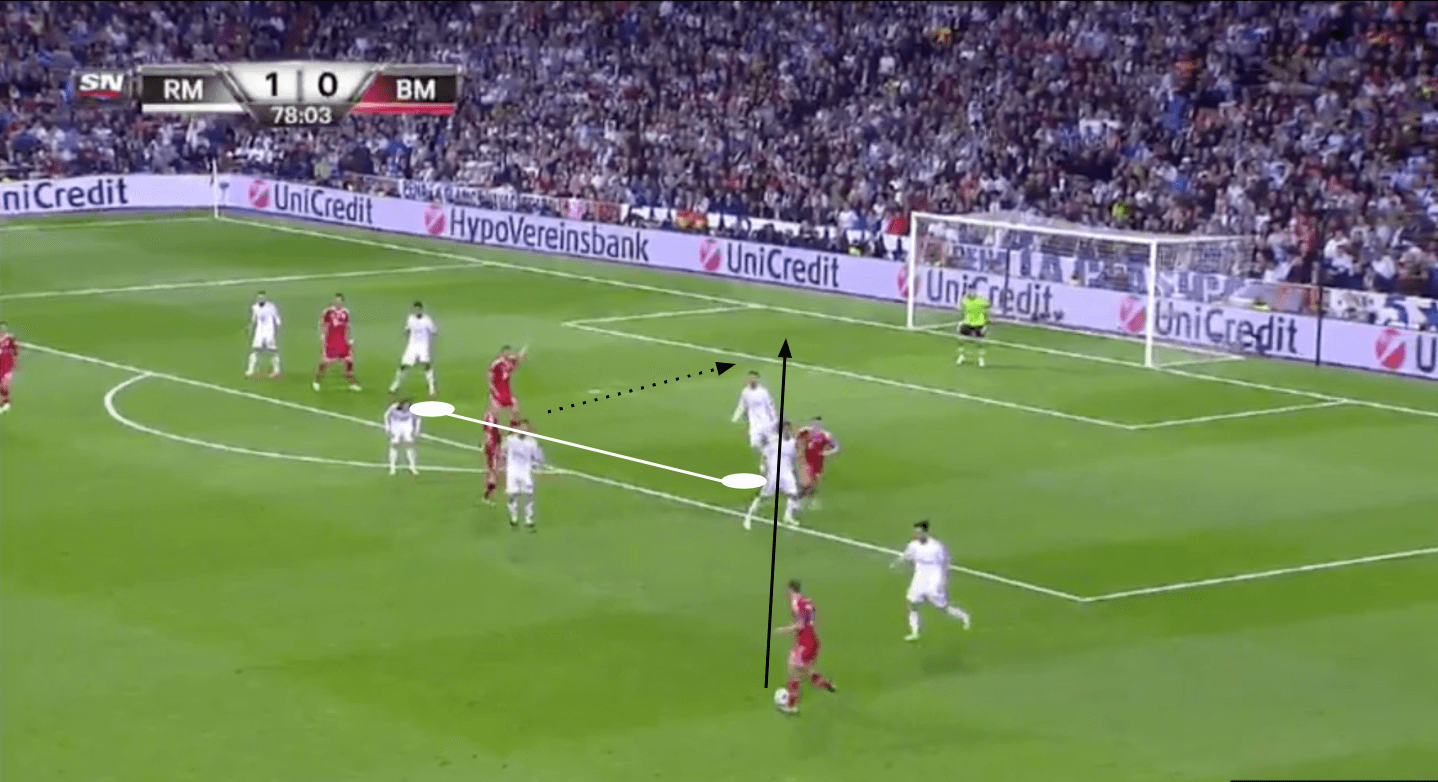

It wasn’t just the midfielders who struggled with communication. Pepe and Ramos, the centre-backs, also struggled on more than one instance. Again, the distance between teammates was too large.

Both men were distracted by opponents who were initially in their space. They made sure they marked them tightly, but they failed to pick up Thomas Müller, who had slid in between them. Müller had so much time and space that he literally bounced up and down, trying to draw the attention of his teammate on the ball. Again, Lahm was unable to pick out the right pass, and Bayern recycled possession instead of delivering a lofted ball into the box. While Madrid’s defensive set-up left much to be desired, their targeted counter-attack allowed them to pull out the victory.

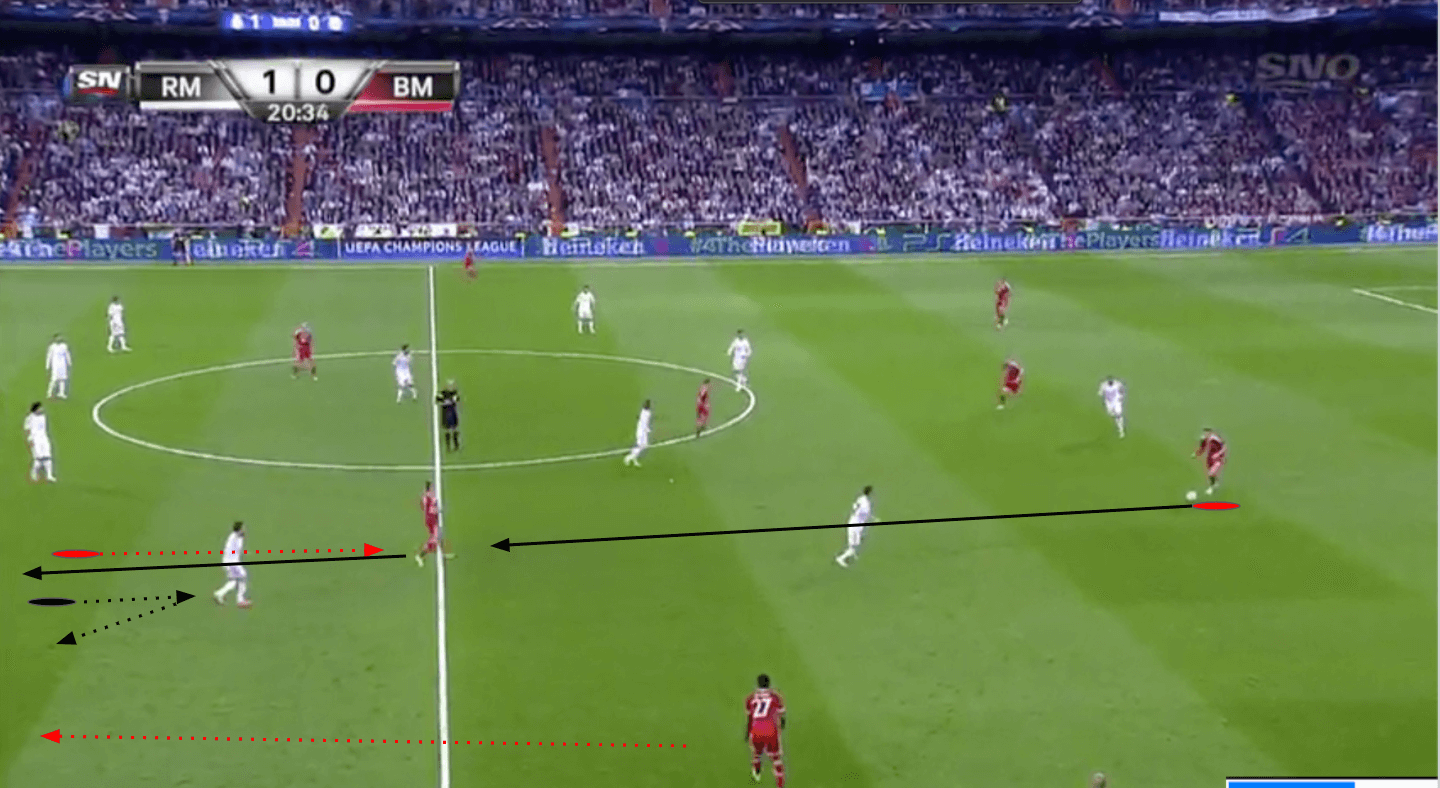

Madrid’s counter-attack targets Boateng & Rafinha

Madrid’s plan in attack, which they knew would be limited, was simple: attack the space Boateng and Rafinha were defending. All their chances came from this space, including their lone goal on the evening as well as a wide-open shot that Ronaldo mishit.

The goal came from a great run by Fábio Coentrão, who left his defensive position to provide a numerical superiority in this counter-attack. As Bayern were still finding their shape, Coentrão ran through lines of pressure.

Ronaldo received the ball at his feet on the left-wing and played a perfectly weighted pass between Boateng and Rafinha directly into Coentrão’s path. Coentrão was able to position himself in front of Boateng, whose only option was to either let Coentrão play the pass or foul him and give him a penalty. Dante slid over to try and help defend, but Coentrão’s pass nutmegged him, and Karim Benzema tapped the ball into the back of the net past Neuer. Less than a minute after they had scored, Ángel Di María picked up a pass in the right half-space and curled a cross into the space between Boateng and Rafinha, this time for a Ronaldo header that went directly into Neuer’s hands. The attack on the two defensemen continued with Bayern again lucky to not have been scored on.

Luka Modric began their next counterattack by dribbling on a diagonal up the pitch.

Benzema curled around Rafinha to the outside, opening up space for Modric to play a long vertical pass, again between Rafinha and Boateng. As the pass was played, Ronaldo stepped forward past Dante, giving himself plenty of room to finish. Benzema played an early ball that bounced to Ronaldo’s right foot. Incredibly, Ronaldo sent the ball into the stands, and Bayern were able to escape unscathed. While they didn’t punish Bayern enough, it became quite clear that Madrid could score consistently if Bayern weren’t more careful.

Conclusion

Bayern Munich were unable to secure an away goal in Madrid that evening, but the team left the Spanish capital confident in their ability to return to Munich and outplay Real Madrid at home. Despite losing, the Bavarians completely overwhelmed Madrid; their only flaw was in their finishing. Most people who watched the match agreed: Bayern would be ready to dominate Real again in Munich, seeing themselves through to the Champions League Final.

Instead, what resulted was one of Pep Guardiola’s worst defeats. In his own words, Guardiola, in the book “Pep Confidential” described it as “a monumental f***-up. A total mess. The biggest f***-up of my life as a coach.” Come back tomorrow and check out the second part of this two-part tactical analysis series.

Comments